Impact Statement

Cartilage injuries and osteoarthritis are very prevalent and considered a public health problem, as they are highly disabling and represent an economic burden. Nowadays, there is a gap of current therapies or active pharmaceutical ingredients for osteoarthritis treatment. Tissue engineering can promote the repair of chondral injuries and is dependent on selecting appropriate cells. In this article, histological and image evaluation were applied to compare the cartilage restoration by tissue engineering and cell therapy from mesenchymal stromal cells derived from the synovial membrane and dental pulp.

1. Introduction

Cartilage injuries and osteoarthritis are very prevalent amongst the global population and considered a public health problem, as they are highly disabling, represent an economic burden for health systems and due to the expected growth of the elderly population, a group that is mainly affected by these pathologies. (Curl et al., 1997; Flanigan et al., 2010; Perera et al., 2012)

Cartilage defects can generate several complications for the individual, such as changes in the biomechanics and homeostasis of the joint, injuries to the adjacent subchondral bone, loss of mobility, degeneration and knee osteoarthritis directly affecting the quality of life. For this reason, the study of new therapies for cartilage lesions is of high clinical relevance. (Gomoll et al., 2010; Showery et al., 2016)

Tissue engineering has risen in the past decades as a multidisciplinary field that can restore, maintain or improve organs and tissues’ functions by developing biological substitutes and taking into consideration appropriate cell selection, inductor factors and biocompatible scaffolds.(Langer & Vacanti, 1993; Dominici et al., 2006; Kuo et al., 2006)

Mesenchymal stromal cells (MSC) have received increased attention in recent research for several reasons, including ease of collection, capacity for cell proliferation and differentiation, and immunomodulatory capacity to regulate local articular joint environment. They can be isolated from different tissues such as bone marrow, adipose tissue, synovial membrane, dental pulp, among others. (Ando et al., 2008)

Dental pulp stromal cells (DPSCs) have the ability to differentiate into chondroblasts and osteoblasts, suggesting that this type of cells is useful for the treatment of bone and chondral injuries. In addition, they are easy to collect, have multipotentiality, capacity for self-renewal, and demonstrate greater proliferative and immunomodulatory capacity in comparison to bone marrow MSCs. (Bueno et al., 2018; Gronthos et al., 2002; Kerkis et al., 2012; Hilkens et al., 2013; de Mendonca et al., 2008)

Synovial membrane stromal cells (SMSCs) have high chondrogenic potential compared to MSCs isolated from bone marrow, can be easily accessed through routine arthroscopy, and can be harvested with minimal complications in the donation area. (Fernandes et al., 2018; Kubosch et al., 2019)

Furthermore, when it comes to local cell delivery, a scaffold-free technology known as tissue engineering construct (TEC) has been considered a potential delivery system. TEC is composed of extracellular matrix synthesized by themselves, does not use external scaffolds that could interfere with cell adhesion and incompatibility, and forms a three-dimensional structure. (Ando et al., 2018)

The purpose of this translational study with medium-sized pigs is to compare the cartilage restoration from MSCs from the synovial membrane (SM) and dental pulp (DP), by tissue engineered treatment using the Good Manufacturing Practices techniques.(Pinheiro et al., 2019)

2. Methods

2.1. Experimental Design

This is a controlled experimental study carried out on 14 brazilian miniature pigs, totaling 28 surgeries, two knees per animal. Outcomes were measured 6 months after surgery.

This project was submitted and approved by the Ethics and Scientific Committee of the Hospital das Clínicas, University of São Paulo (protocol: CAPPesq nº 15428, IOT nº 1216) and by the Ethics Committee on the Use of Animals of the Hospital Sírio Libanês (approval number: CEUA P 2017-05). All patients signed informed consent forms for synovial and fat-pad discarded tissue usage in research. All these methods were better described in a previous article. (Santanna et al., 2022)

2.2. Harvesting, Isolation, and Expansion of MSCs

MSCs were harvested from the synovial tissue of human knees and dental pulp of deciduous teeth.

The synovial tissue was harvested from the human knee and included seven patients who underwent arthroscopic surgery for anterior cruciate ligament or meniscus injuries. Exclusion criteria included patients with previous history of surgery, infection, inflammatory arthritis and pregnant women. (Fernandes et al., 2018)

A sample up to 1g of synovia was stored in a 50ml falcon flask containing saline solution 0.9% and was sent immediately to the Cell Processing Laboratory at Hospital Sírio Libanês (São Paulo, Brazil) and processed up to 6 hours after harvesting. (Fernandes et al., 2018)

The dental pulp was collected from the deciduous tooth of seven healthy children that lost them spontaneously and would be discarded. The samples were sent immediately to the Cell Processing Laboratory at Hospital Sírio Libanês (São Paulo, Brazil) and processed on average 15 hours after collection. (Pinheiro et al., 2019)

The MSC were cultured until they reached 70% to 80% confluence of the entire area of the culture plate. After reaching this confluence, the MSCs were expanded until they reached the number required for the experiment. (Pinheiro et al., 2019)

The MSC samples were processed, cultured and plated separately in a Good Manufacturing Practice (GMP) Laboratory for human usage, following the directives elaborated by the national regulatory authority, ANVISA. (Pinheiro et al., 2019)

The SMSCs and DPSCs were characterized by flow cytometry between passages four and five and were induced in vitro into osteogenic, chondrogenic and adipogenic differentiation to confirm their multipotential capacity. (Pinheiro et al., 2019; Fernandes et al., 2018).

2.3. TEC Development

After cell culture, the SMSCs and DPSCs were plated on a 12-well culture dish at a density of 4.0x10^5 cells/cm^2 in the culture medium with 0.2 mM ascorbic acid 2-phosphate (Asc-2P; Sigma-Aldrich, St. Louis, MO). After approximately 15 days, the cell constructs and extracellular matrix synthesized by themselves were detached from the substrate by applying shear stress using a pipette. The separate constructs were left in suspension to form a three-dimensional structure by active tissue contraction. This tissue was called tissue engineering construct, TEC, composed of cells and extracellular matrix. (Ando et al., 2018)

2.4. Animal Model and Surgical Technique

Fourteen female miniature pigs named BR-1, with a skeletal age compatible with sexual maturity (8 to 12 months) and weighing 19 to 22 kilograms (Minipig Pesquisa e Desenvolvimento, Ltda., Campina do Monte Alegre, SP, Brazil) were used in the present study. (Santanna et al., 2022)

Information on the characteristics, care, and procedures related to animals was collected following the ARRIVE Guidelines Checklist (Kilkenny) and kept in a digital repository, REDCAP (Harris et al., 2009).

The animals were induced for general anesthesia and placed on the operating table. At the time of surgery and in a randomized manner, the surgeon was informed which side would receive the TEC, and which would only have a defect. (Santanna et al., 2022)

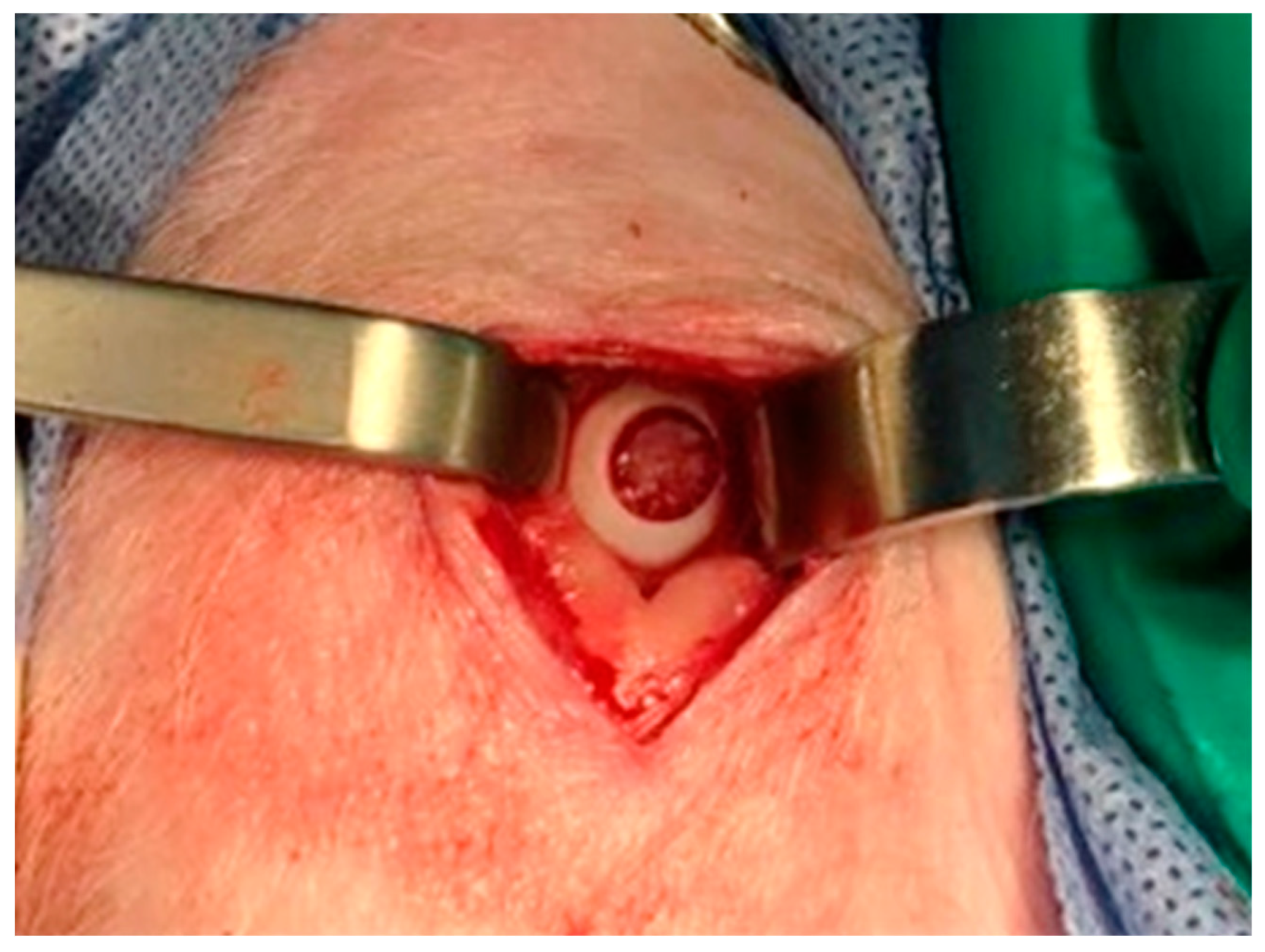

A full-thickness cartilage defect measuring 6 mm (

Figure 1) in diameter was performed in the loading area of the medial femoral condyle, on the two hind limbs of each animal. Following, the TEC was placed into the defect. (Murray et al., 2010)

The animals were treated post-operatively. At 6 months after surgery, the animals were euthanized and the hind limbs were disarticulated. (Santanna et al., 2022)

2.5. Evaluation Methods

2.5.1. Magnetic Resonance Imaging

A 7-tesla high-field magnetic resonance imaging (MRI) scanner (Magnetom 7 Tesla, Siemens Healthcare, Germany) with a head coil with 1 transmission channel and 32 receiving channels (Nova Medical, Inc.) was used for imaging at PISA Project (Faculdade de Medicina USP). Images were collected from both knees of the 14 animals using two sequences. (Goebel et al., 2014; Trattnig et al., 2009)

The first sequence performed was the 3D double echo steady state (3D-DESS) for morphological evaluation. The parameters applied were the following: repetition time (TR) = 12.2 ms, echo time (TE) = 4.1 ms, fractional anisotropy (FA) = 25º, voxel = 0.4 x 0.4 x 0.4 mm^3, field-of-view (FoV) = 192 x 256 mm, slice thickness 0.4 mm, acquisition time 10:52 minutes). (Goebel et al., 2014; Trattnig et al., 2009)

For these acquired images, sagittal and coronal views were used and articular cartilage repair tissue was evaluated using Magnetic Resonance Observation of Cartilage Repair Tissue (MOCART) 3D score. The score uses 11 categories to classify cartilage repair, ranging from 0 (no repair) to 100 points (complete repair of the cartilage defect).

The second sequence was the spin-echo with multiecho to evaluate the water and collagen fiber composition of the cartilage based on T2 mapping creation using ImageJ software (National Institutes of Health). The parameters were the following: TR = 10000 ms, 18 echos, TE = 9 / 18 / 27 / 336 / 45 / 54 / 63 / 72 / 81 / 90 / 99 / 108 / 117 / 126 / 135 / 144 / 153 / 162; voxel = 0,6 x 0,6 x 2,0 mm^3, FoV 93 x 229 mm, slice thickness 2,0 mm, acquisition time 18:44 minutes). (Domayer et al., 2008; White et al., 2006)

For these acquired images, three consecutive sagittal sections were selected from each knee. In each section, one area of interest was selected representing the cartilage defect untreated and treated with the implantation of the TEC, and another was selected representing the intact chondral tissue (adjacent cartilage). After selecting the areas, the average T2 value was measured in each section of each knee. (Domayer et al., 2008; White et al., 2006)

Another assessment carried out was the mean T2 value measurement of the deep and superficial areas of the previously selected areas of interest. (White et al., 2006)

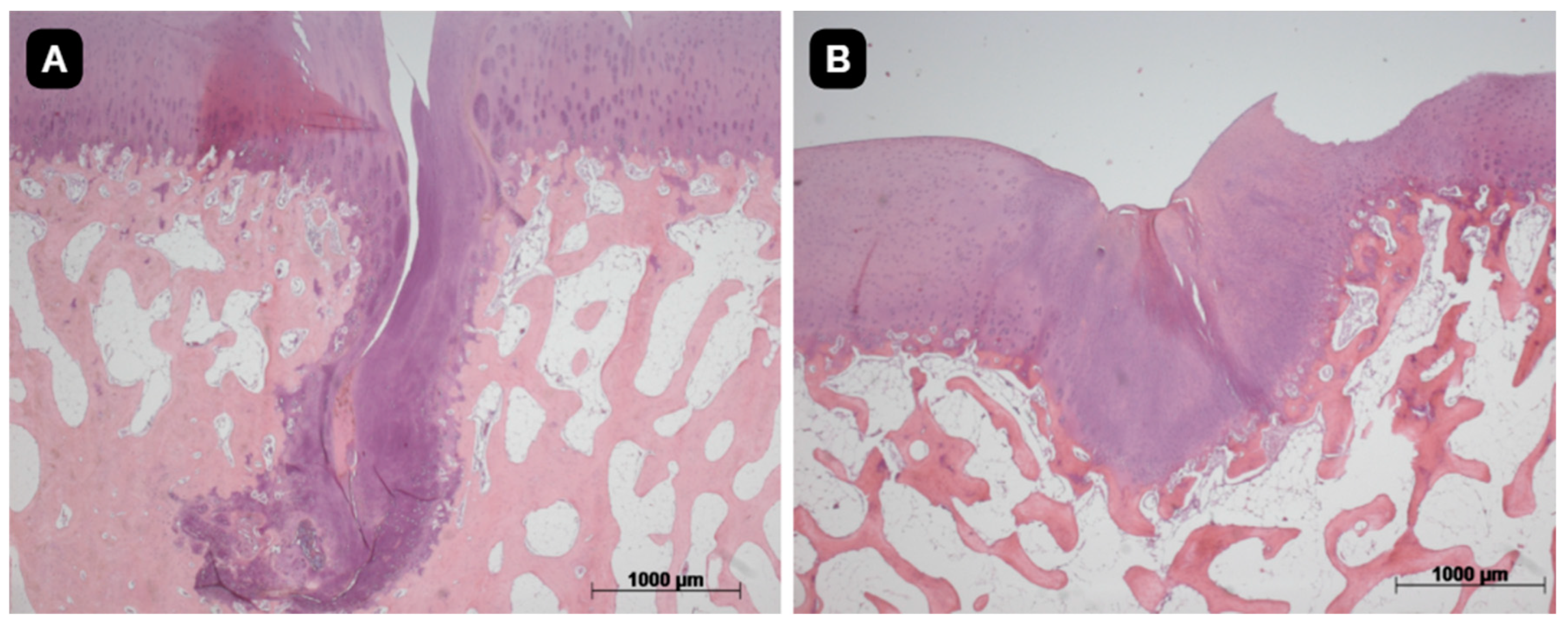

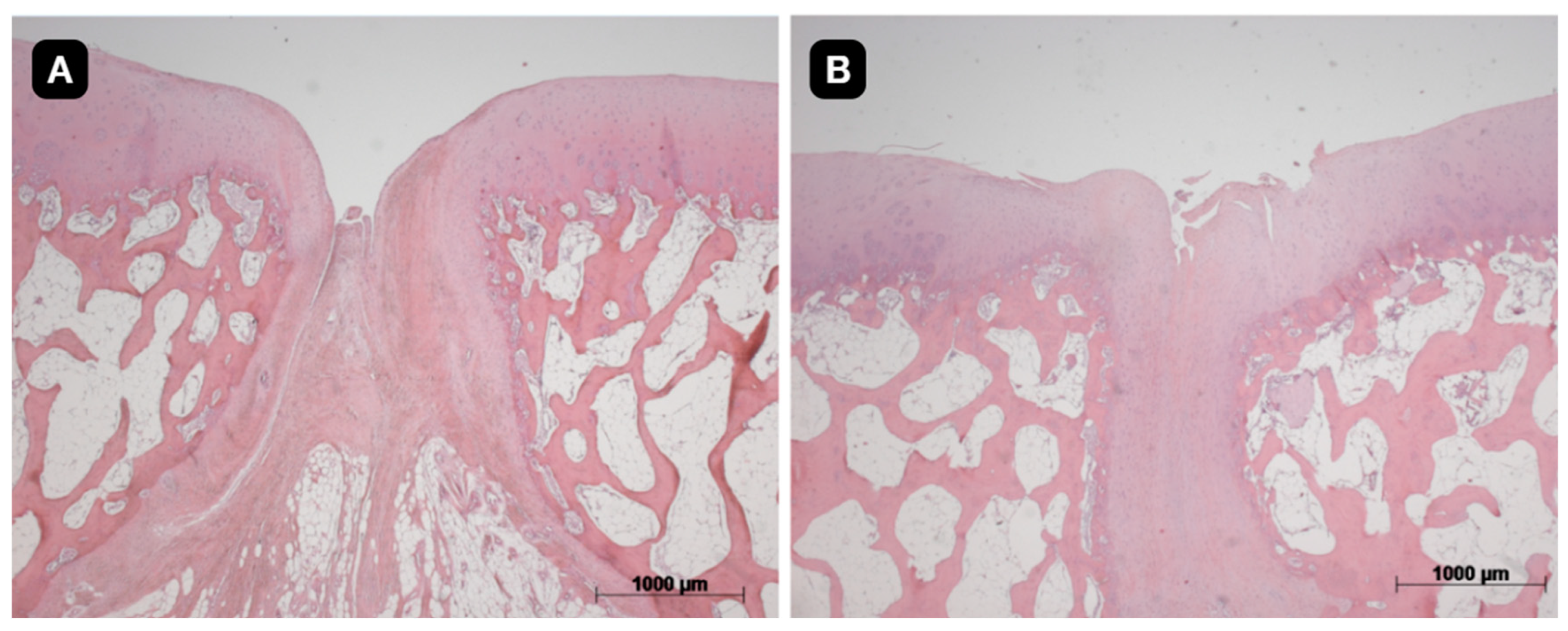

2.5.2. Histological Evaluation

After MRI evaluation, both knees were dissected and subjected to histological evaluation in order to analyze the quality of the cartilage repair. A block around the defect measuring approximately 1.5 x 1.5 x 1.5 cm was cut and the tissue was fixed in 4% paraformaldehyde (PFA) and decalcified with ethylenediamine tetra-acetic acid (EDTA). The sections were prepared with a thickness of 4μm and stained with hematoxylin and eosin (HE). Two sections from each animal were stained with toluidine blue to evaluate the color concentration of the extracellular matrix. (Manil-Varlet et al., 2010)

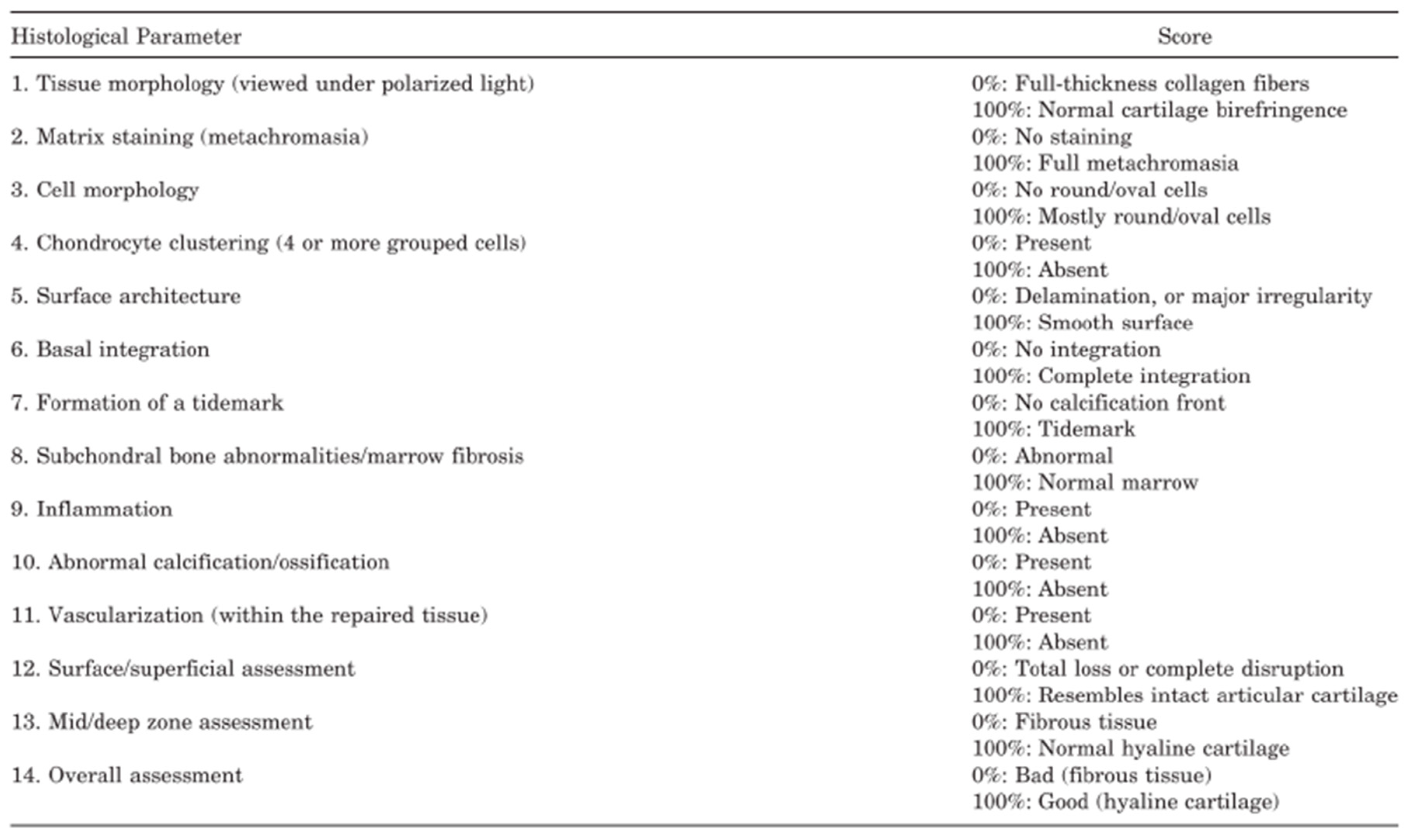

The ICRS-2 scoring system (

Figure 2) was used to assess the articular cartilage repair tissue and assigned a score for each of the 14 categories evaluated in the system, from 0 (worst result) to 100 points (best result).

2.6. Statistical Analysis

Quantitative variables with normal distribution were described by measures of central tendency and dispersion (mean and standard deviation).

ANOVA analyses followed by post-hoc Bonferroni were used to compare the values obtained from the MOCART 3D system score and the ICRS-2 score. This test was used as the knees compared were from the same pigs, and were subjected to the same external stimuli.

ANOVA analyses were also used to compare the mean T2 values of the areas of interest, chondral defect and adjacent cartilage, and the T2 values from the deep and superficial regions in each area.

The correlation between the different scoring systems (MOCART and ICRS-2) was measured with the Pearson correlation coefficient. The Software Sigmaplot (Systat Software, Inc., San Jose, CA, USA) was used in the calculations. The level of statistical significance adopted was equal to 5%, that is, the test results were considered statistically significant when p<0,05.

3. Results

3.1. Characterization of MSC Strains

The cell characterization by flow cytometry and in vitro induction confirmed the multipotentiality of cells derived from the SM and DP, since they differentiated into osteogenic, chondrogenic, and adipogenic strains. In addition, MSC showed positive reactions for mesenchymal markers (CD29, CD44, CD73, CD105, CD90, and CD166) and negative reactions to hematopoietic (CD34 and CD45) and endothelial markers (CD31).

3.2. Magnetic Resonance Imaging

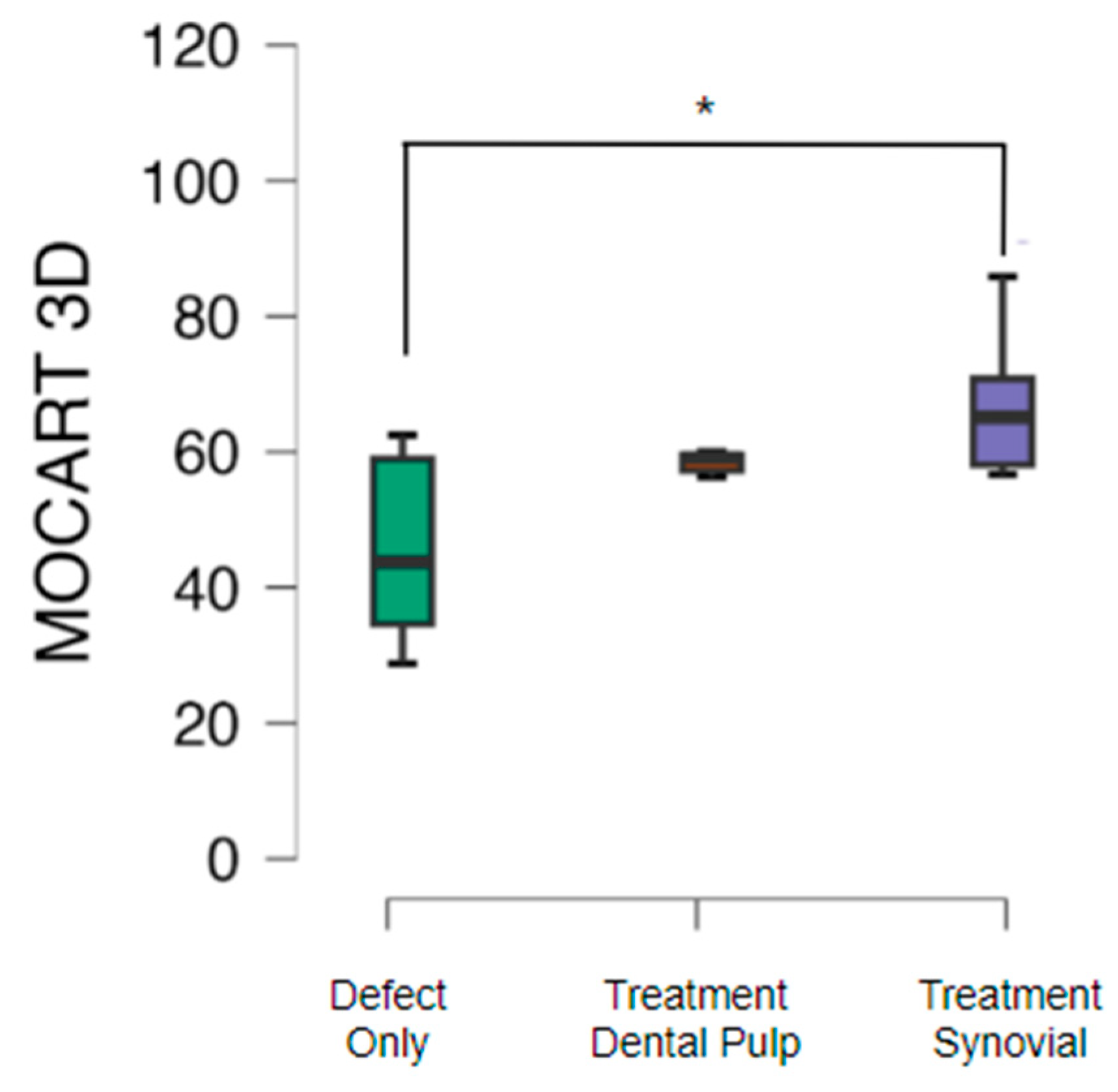

Morphological assessment of cartilage repair with the MOCART 3D score showed that cartilage repair in knees subjected only to the cartilage defect presented a mean MOCART value of 46.2 with standard deviation of 13.4. The group treated with TEC from SM had a mean MOCART value of 65.7 with standard deviation of 15.5 (p<0.05) and from the DP the mean value obtained was 59.0 with standard deviation of 7.9 (

Figure 3).

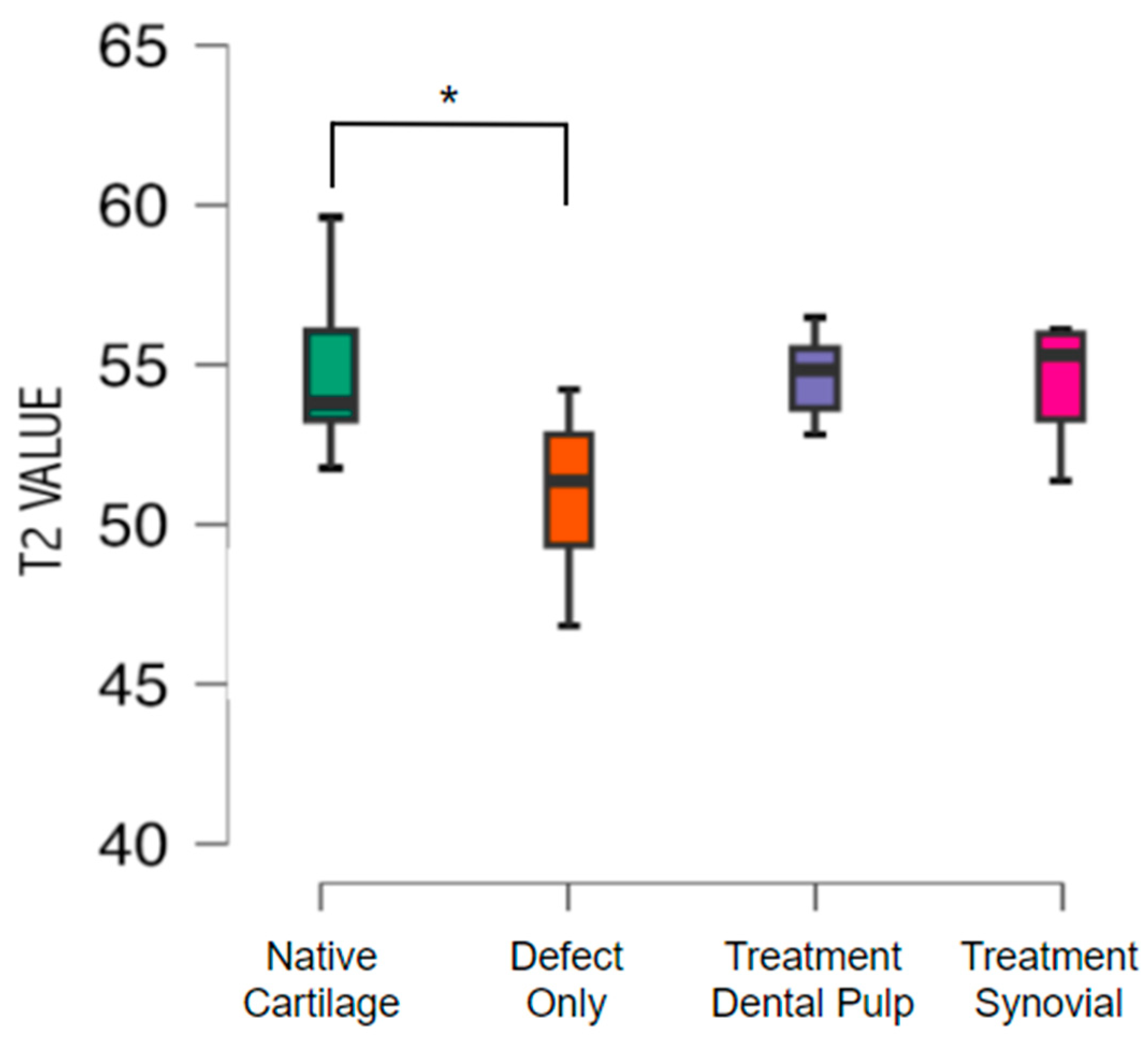

Cartilage composition was assessed with T2 mapping, showing a mean value of T2 of 54.9 with standard deviation of 1.9 in the native cartilage. The untreated group exhibited a mean T2 value of 50.9 with standard deviation 2.4 (p<0.05). No difference was found between the native cartilage and the treated groups. The mean T2 value from the group treated with TEC from the SM was 54.31 with a standard deviation of 2.07, and from the DP was 54.54 with standard deviation of 1.47 (

Figure 4)

.

When measuring the T2 value by zones of the native cartilage and in the groups that received treatment with TEC of the PD and SM, there was a decrease comparing the value of the superficial zone and the value of the deep zone. On the other hand, when analyzing the defect group, there was a small increase from the superficial zone to the deep zone, with no significant difference.

The T2 value (Mean ± Standard Deviation) obtained in the superficial zone of the native cartilage (n=12) was 59.3 ± 2.4 and in the deep zone was 50.7 ± 2.9 (p<0.001). Considering the DP group (n=6), the mean T2 value was 57.5 ± 2.7 for the superficial zone and 51.6 ± 2.0 for the deep zone (p < 0.05). For the SM group (n=6), the mean T2 value was 57.1 ± 3.9 for the superficial zone and 51.5 ± 2.0 for the deep zone (p < 0.05). The defect group (n=12) presented a mean T2 value of 50.5 ± 4.9 for the superficial zone and 51.4 ± 2.6 for the deep zone.

3.3. Histological Evaluation

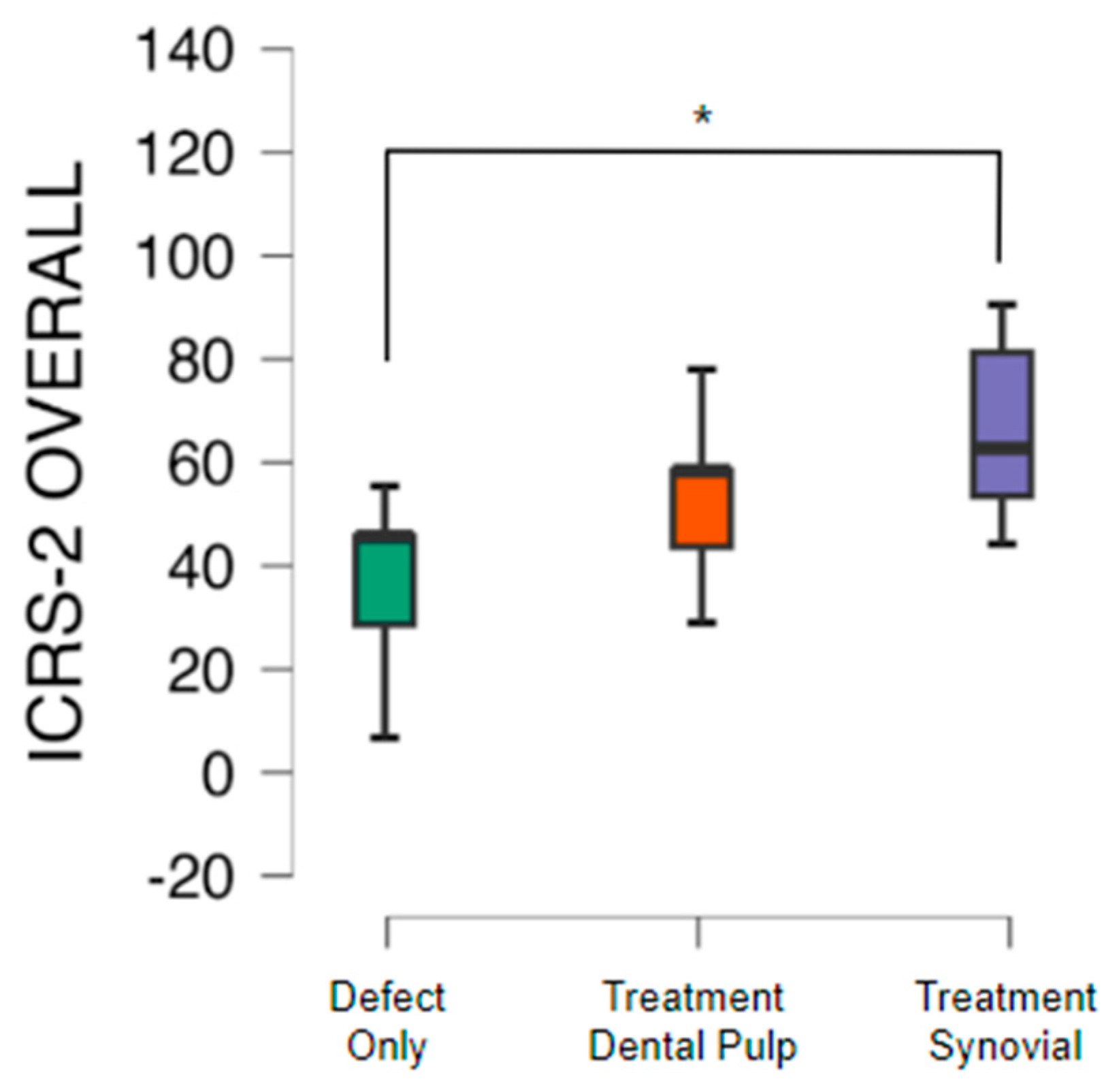

The quality of the tissue and its intrinsic characteristics were assessed by the ICRS-2 score system (

Table 1). The untreated group presented a mean value 42.1 with standard deviation of 14.8. The group with TEC from SM had a significant difference in comparison to the untreated group and presented a mean value of 64.3 with standard deviation of 19.0 (p<0.05). The group with TEC from DP presented a mean value of 54.3 with standard deviation of 12.2 (

Figure 5,

Figure 6 and

Figure 7).

4. Discussion

This pre-clinical study showed better results in the SM group when compared to control in MRI and histological analysis. In addition, SM was better compared to the DP group considering only MRI assessment. This study compares the cartilage restoration using a scaffold-free tissue engineering construct (TEC) between SM- and DP-derived MSCs.

Ando et al. (2008) and Shimomura et al. (2010) first reported the feasibility of creating scaffold-free approaches for chondral repair, testing in a swine model with MSCs from the SM. In contrast, the present study is known to be the first to use MSCs from DP and SM to create the TEC and to report the data from histological and imaging evaluation.

Magnetic resonance imaging is a non-invasive imaging method that can assess the quality of hyaline cartilage. The results from animal model study can easily be translated into future clinical studies.

Recently, after conducting a pilot study in humans, Shimomura et al. (2023) reported the clinical outcomes and magnetic resonance imaging (MRI) findings 5 years after implantation of the TEC, highlighting its improvement over the years and confirming its efficacy and feasibility.

Using the MOCART 3D score system, Shimomura et al. (2023) presented a mean value (Mean ± Standard Deviation) of MOCART of 82.0 ± 13 in the group treated with TEC, with a slight decrease compared to the study from 2 years follow-up, but with an increase comparing with the 6 months follow-up and still maintaining a high score. No control group was used. (Shimomura et al., 2018)

The present study, similarly, showed better results in the group treated with TEC in comparison to the defect group, in addition to having a significant difference considering the MSCs from the SM. However, the average value of the MOCART 3D score was lower, 65.7 from the SM and 59.0 from the DP. This may be related to the evaluation time, which is 5 years in the study conducted by Shimomura et al. compared to 6 months of evolution in the present animal study.

Yamasaki et al. (2019) also reported a higher MOCART 2D score in the intervention group compared to the defect only, after 6 months of implantation of a tridimensional bioprinted scaffold-free technology. The mean value of the MOCART 2D score obtained was 45.8 in the implanted group and 20.0 in the control group, with statistical difference. This study used adipose tissue-derived cells.

MRI is sensitive to specific changes in chemical composition and structure of cartilage even before severe morphological changes and T2 mapping is a technique to assess this aspect and complement morphological evaluation. (Trattnig et al., 2009; Crema et al., 2011; Hayashi et al., 2018)

As occurred in the present study, Theruvath et al. (2021) and Shimomura et al. (2018) found a significant difference in the T2 value between the defect-only group and healthy or native cartilage. Shimomura et al. (2018) also evaluated the T2 mapping throughout time, 6 and 24 weeks after surgery, demonstrating that variations in T2 values occur and might be associated with maturation of the repair tissue over time.

In addition, in the present study, the mean T2 values between native cartilage and the tissue formed by TEC from both groups were close after 6 months, indicating similar compositions.

Differences between T2 values in the cartilage zones indicate composition variations of the cartilage tissue, in which a high T2 value found in the superficial zone is associated with a higher water concentration. White et al. in an equine model study demonstrated that the superficial region presented a higher T2 value than the deep region, the same pattern found in the present study with the groups from native cartilage and TEC treatment derived from DP and synovium.

Shimomura et al. obtained no significant difference when calculating the T2 values in different areas, even after 2 years of treatment. The difference was found only in the histological assessment. Other authors, such as Welsch et al. (2008); Schreiner et al. (2020) and Shiomi et al. (2013) used the measurement of the mean T2 value by zones to evaluate chondral repair, as it provides additional information.

Histological analysis can complement the findings from cartilage imaging evaluation and also correlates with them, since it provides data on intrinsic characteristics of the tissue and its quality. (Goebel et al., 2014)

Ando et al. (2007) evaluated the histology based on the ICSR 1 in a swine model after 6 months of surgery, comparing the group that received TEC from SM MSCs and the defect group. Similarly to the present study, the histological repair score in the intervention group was significantly better than that of the untreated group.

Shimomura et al. (2018) assessed the histology of the repair tissue using ICRS 2 on patients that received TEC treatment, 48 weeks after surgery. Despite not having a control group, the TEC implanted group presented a mean value of 80.0 ± 11.0

The ICRS-2 mean value was 42.1 ± 14.7 in the untreated group, 64.2 ± 19.0 in the group with TEC from SM (p<0,05) and 54.2 ± 16.1 from DP.

The average value of the ICRS 2 score was lower in the present study, in which a mean score of 54.2 was obtained from the group treated with MSC from the DP, 64.2 from the SM with significant difference in comparison to the defect group that presented a mean value of 42.1. This difference may also be related to the evaluation time, since the present study analyzed the tissue 6 months, almost 26 weeks, after surgery, whereas Shimomura et al. (2018) assessed after 48 weeks.

Gardner et al. (2019) conducted a study using tissue engineering as an intervention and evaluated the histology using ICRS 2 score system, comparing with the group that haven’t received any treatment. After 6 weeks of surgery, no significant difference was found. However, after 12 weeks, there was a significant improvement in the values.

Mesenchymal stromal cells derived from the dental pulp have been studied for several applications, mainly for bone conditions such as alveolar clefts (Pinheiro et al., 2019; Bueno et al., 2019; Bai et al., 2023). These cells are easy to collect and can be obtained with minimal donor site morbidity and iatrogenic damage. There are few studies on its use for cartilage injuries and osteoarthritis and most of them demonstrated the capacity of this local site for the purpose of cartilage repair. However, no studies were found regarding the comparison of DPSC and SMSC. (Fariborz et al., 2023; Fu et al., 2023; Lo Monaco et al., 2020)

One of the limitations of this study is the absence of male animal models. It was decided to use female animals in the research project as part of the strategy to characterize the presence of donor cells.

This study presented an active pharmaceutical ingredient derived from tissue engineering therapeutic option known as TEC, for a highly prevalent condition with a high impact on public health. As it does not require an external scaffold, it is safer and can reduce the costs of treating cartilage injuries. As future steps, phase I/II and "first in human" clinical trials may be carried out.

5. Conclusion

TEC derived from SM led to superior cartilage coverage and quality compared to the defect group in MRI and histological analysis. In the MRI assessment, both DP and SM groups showed better results in comparison to the defect group. In the histological assessment, TEC from SM demonstrated better results than the defect group and had no difference to the treatment with TEC from the DP.

References

- Curl, W.W., Krome, J., Gordon, E.S., Rushing, J., Smith, B.P., and Poehling, G.G. Cartilage injuries: a review of 31,516 knee arthroscopies. Arthroscopy 13, 456, 1997. [CrossRef]

- Flanigan, D.C., Harris, J.D., Trinh, T.Q., Siston, R.A., and Brophy, R.H. Prevalence of chondral defects in Athletes’ Knees: a systematic review. Med Sci Sports Exerc 42, 1795, 2010. [CrossRef]

- Perera, J.R., Gikas, P.D., and Bentley, G. The present state of treatments for articular cartilage defects in the knee. Ann R Coll Surg Engl 94, 381, 2012. [CrossRef]

- Gomoll, A.H., Madry, H., Knutsen, G., et al. The subchondral bone in articular cartilage repair: current problems in the surgical management. Knee Surg Sports Traumatol Arthrosc 18, 434, 2010. [CrossRef]

- Showery, J.E., Kusnezov, N.A., Dunn, J.C., Bader, J.O., Belmont, P.J., and Waterman, B.R. The rising incidence of degenerative and posttraumatic osteoarthritis of the knee in the United States military. J Arthroplasty 31, 2108, 2016. [CrossRef]

- Langer, R., and Vacanti, J.P. Tissue engineering. Science 260, 920, 1993.

- Dominici, M., Le Blanc, K., Mueller, I., et al. Minimal criteria for defining multipotent mesenchymal stromal cells. The International Society for Cellular Therapy position statement. Cytotherapy 8, 315, 2006. [CrossRef]

- Kuo, C.K., Li, W.J., Mauck, R.L., and Tuan, R.S. Cartilage tissue engineering: its potential and uses. Curr Opin Rheumatol 18, 64, 2006. [CrossRef]

- Ando, W., Tateishi, K., Katakai, D., et al. In vitro generation of a scaffold-free tissue-engineered construct (TEC) derived from human synovial mesenchymal stem cells: biological and mechanical properties and further chondrogenic potential. Tissue Eng Part A 14, 2041, 2008. [CrossRef]

- Bueno, D.F. Bone Tissue Engineering With Dental Pulp b AU12 Stem Cells for Alveolar Cleft Repair—Full Text View—ClinicalTrials.gov. Hospital Sirio-Libanes 2018.

- Gronthos, S., Brahim, J., Li, W., et al. Stem cell properties of human dental pulp stem cells. J Dent Res 81, 531, 2002. [CrossRef]

- de Mendonca Costa, A., Bueno, D.F., Martins, M.T., et al. Reconstruction of large cranial defects in nonimmuno-suppressed experimental design with human dental pulp stem cells. J Craniofac Surg 19, 204, 2008. [CrossRef]

- Kerkis, I., and Caplan, A.I. Stem cells in dental pulp of deciduous teeth. Tissue Eng Part B Rev 18, 129, 2012.

- Hilkens, P., Gervois, P., Fanton, Y., et al. Effect of isolation methodology on stem cell properties and multilineage differentiation potential of human dental pulp stem cells. Cell Tissue Res 353, 65, 2013. [CrossRef]

- Fernandes, T.L., Kimura, H.A., Pinheiro, C.C.G., et al. Human synovial mesenchymal stem cells good manufacturing practices for articular cartilage regeneration. Tissue Eng Part C Methods 24, 709, 2018. [CrossRef]

- Kubosch, E.J., Lang, G., Furst, D., et al. The potential for synovium-derived stem cells in cartilage repair. Curr Stem Cell Res Ther 13, 174, 2018.

- Pinheiro, C.C.G., Leyendecker Junior, A., Tanikawa, D.Y.S., Ferreira, J.R.M., Jarrahy, R., and Bueno, D.F. Is there a noninvasive source of MSCs isolated with GMP methods with better osteogenic potential? Stem Cells Int 2019, 1, 2019.

- Pinheiro, C.C.G., Leyendecker Junior, A., Tanikawa, D.Y.S., Ferreira, J.R.M., Jarrahy, R., and Bueno, D.F. Is there a noninvasive source of MSCs isolated with GMP methods with better osteogenic potential? Stem Cells Int 2019, 1, 2019. [CrossRef]

- SantAnna JPC, Faria RR, Assad IP, Pinheiro CCG, Aiello VD, Albuquerque-Neto C, Bortolussi R, Cestari IA, Maizato MJS, Hernandez AJ, Bueno DF, Fernandes TL. Tissue Engineering and Cell Therapy for Cartilage Repair: Preclinical Evaluation Methods. Tissue Eng Part C Methods. 2022 Feb;28(2):73-82. PMID: 35107353. [CrossRef]

- Kilkenny, C., Browne, W., Cuthill, I.C., Emerson, M., Altman, D.G., and NC3Rs Reporting Guidelines Working Group. Animal research: reporting in vivo experiments: the ARRIVE guidelines. Br J Pharmacol 160, 1577, 2010. [CrossRef]

- Harris, P.A., Taylor, R., Thielke, R., Payne, J., Gonzalez, N., and Conde, J.G. Research electronic data capture (REDCap)—a metadata-driven methodology and workflow process for providing translational research informatics support. J Biomed Inform 42, 377, 2009. [CrossRef]

- Murray MM. The effect of skeletal maturity on functional healing of the anterior cruciate ligament. J Bone Jt Surg. 2010 Sep 1;92(11):2039. [CrossRef]

- Goebel L, Zurakowski D, Müller A, Pape D, Cucchiarini M, Madry H. 2D and 3D MOCART scoring systems assessed by 9.4T high-field MRI correlate with elementary and complex histological scoring systems in a translational model of osteochondral repair. Osteoarthr Cartil. 2014;22(10):1386–95.

- Trattnig S, Domayer S, Welsch GW, Mosher T, Eckstein F. MR imaging of cartilage and its repair in the knee - A review. Vol. 19, European Radiology. Springer-Verlag; 2009. p. 1582–94. [CrossRef]

- Domayer SE, Kutscha-Lissberg F, Welsch G, Dorotka R, Nehrer S, Gäbler C, et al. T2 mapping in the knee after microfracture at 3.0 T: correlation of global T2 values and clinical outcome - preliminary results. Osteoarthr Cartil. 2008 Aug 1;16(8):903–8.

- White LM, Sussman MS, Hurtig M, Probyn L, Tomlinson G, Kandel R. Cartilage T2 assessment: Differentiation of normal hyaline cartilage and reparative tissue after arthroscopic cartilage repair in equine subjects. Radiology. 2006;241(2):407–14. [CrossRef]

- Mainil-Varlet P, Van Damme B, Nesic D, Knutsen G, Kandel R, Roberts S. A new histology scoring system for the assessment of the quality of human cartilage repair: ICRS II. Am J Sports Med. 2010;38(5):880–90. [CrossRef]

- Bai X, Cao R, Wu D, Zhang H, Yang F, Wang L. Dental Pulp Stem Cells for Bone Tissue Engineering: A Literature Review. Stem Cells Int. 2023 Oct 11;2023:7357179. [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Nowzari F, Zare M, Tanideh N, Meimandi-Parizi A, Kavousi S, Saneian SM, Zare S, Koohi-Hosseinabadi O, Ghaemmaghami P, Dehghanian A, Daneshi S, Azarpira N, Aliabadi A, Samimi K, Irajie C, Iraji A. Comparing the healing properties of intra-articular injection of human dental pulp stem cells and cell-free-secretome on induced knee osteoarthritis in male rats. Tissue Cell. 2023 Jun;82:102055. . Epub 2023 Mar 5. [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Fu Y, Cui S, Zhou Y, Qiu L. Dental Pulp Stem Cell-Derived Exosomes Alleviate Mice Knee Osteoarthritis by Inhibiting TRPV4-Mediated Osteoclast Activation. Int J Mol Sci. 2023 Mar 3;24(5):4926. PMID: 36902356; PMCID: PMC10003468. [CrossRef]

- Lo Monaco M, Gervois P, Beaumont J, Clegg P, Bronckaers A, Vandeweerd JM, Lambrichts I. Therapeutic Potential of Dental Pulp Stem Cells and Leukocyte- and Platelet-Rich Fibrin for Osteoarthritis. Cells. 2020 Apr 15;9(4):980. PMID: 32326610; PMCID: PMC7227024. [CrossRef]

- Shimomura K, Ando W, Tateishi K, Nansai R, Fujie H, Hart DA, Kohda H, Kita K, Kanamoto T, Mae T, Nakata K, Shino K, Yoshikawa H, Nakamura N. The influence of skeletal maturity on allogenic synovial mesenchymal stem cell-based repair of cartilage in a large animal model. Biomaterials. 2010 Nov;31(31):8004-11. Epub 2010 Jul 31. PMID: 20674010. [CrossRef]

- Shimomura K, Yasui Y, Koizumi K, Chijimatsu R, Hart DA, Yonetani Y, et al. First-in-Human Pilot Study of Implantation of a Scaffold-Free Tissue-Engineered Construct Generated From Autologous Synovial Mesenchymal Stem Cells for Repair of Knee Chondral Lesions. Am J Sports Med. 2018;46(10):2384–93. [CrossRef]

- Yamasaki A, Kunitomi Y, Murata D, Sunaga T, Kuramoto T, Sogawa T, et al. Osteochondral regeneration using constructs of mesenchymal stem cells made by bio three-dimensional printing in mini-pigs. J Orthop Res. 2019 Jun 24;37(6):1398–408. [CrossRef]

- Crema MD, Roemer FW, Marra MD, Burstein D, Gold GE, Eckstein F, et al. Articular Cartilage in the Knee: Current MR imaging techniques and applications in clinical practice and research. Radiographics. 2011 Jan 19;31(1):37–61. [CrossRef]

- Hayashi D, Li X, Murakami AM, Roemer FW, Trattnig S, Guermazi A. Understanding Magnetic Resonance Imaging of Knee Cartilage Repair: A Focus on Clinical Relevance. Vol. 9, Cartilage. SAGE Publications; 2018. p. 223–36. [CrossRef]

- Theruvath AJ, Mahmoud EE, Wu W, Nejadnik H, Kiru L, Liang T, et al. Ascorbic Acid and Iron Supplement Treatment Improves Stem Cell– Mediated Cartilage Regeneration in a Minipig Model. Am J Sports Med. 2021;49(7):1861–70. [CrossRef]

- Welsch GH, Mamisch TC, Hughes T, Zilkens C, Quirbach S, Scheffler K, et al. In vivo biochemical 7.0 tesla magnetic resonance: Preliminary results of dGEMRIC, zonal T2, and T2* mapping of articular cartilage. Invest Radiol. 2008 Sep;43(9):619–26.

- Welsch GH, Mamisch TC, Marlovits S, Glaser C, Friedrich K, Hennig FF, et al. Quantitative T2 mapping during follow-up after matrix-associated autologous chondrocyte transplantation (MACT): Full-thickness and zonal evaluation to visualize the maturation of cartilage repair tissue. J Orthop Res. 2009 Jul 1;27(7):957–63. [CrossRef]

- Schreiner MM, Raudner M, Szomolanyi P, Ohel K, Ben-Zur L, Juras V, et al. Chondral and Osteochondral Femoral Cartilage Lesions Treated with GelrinC: Significant Improvement of Radiological Outcome Over Time and Zonal Variation of the Repair Tissue Based on T2 Mapping at 24 Months. Cartilage. 2020 Jun 4;1947603520926702. [CrossRef]

- Shiomi T, Nishii T, Nakata K, Tamura S, Tanaka H, Yamazaki Y, et al. Three-dimensional topographical variation of femoral cartilage T2 in healthy volunteer knees. Skeletal Radiol. 2013 Mar 22;42(3):363–70. [CrossRef]

|

Disclaimer/Publisher’s Note: The statements, opinions and data contained in all publications are solely those of the individual author(s) and contributor(s) and not of MDPI and/or the editor(s). MDPI and/or the editor(s) disclaim responsibility for any injury to people or property resulting from any ideas, methods, instructions or products referred to in the content. |

© 2024 by the authors. Licensee MDPI, Basel, Switzerland. This article is an open access article distributed under the terms and conditions of the Creative Commons Attribution (CC BY) license (http://creativecommons.org/licenses/by/4.0/).