Submitted:

02 June 2025

Posted:

02 June 2025

You are already at the latest version

Abstract

Keywords:

1. Introduction

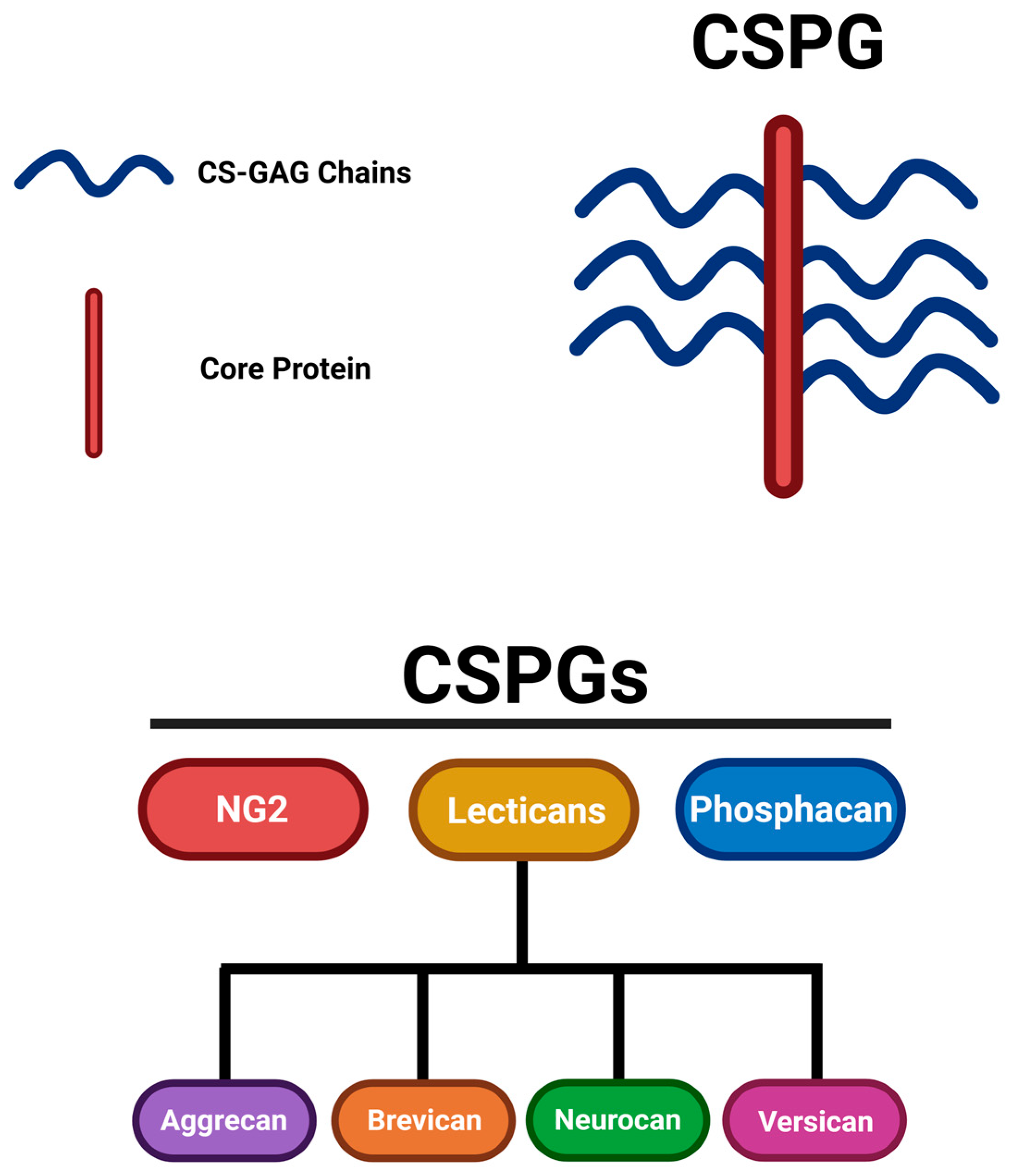

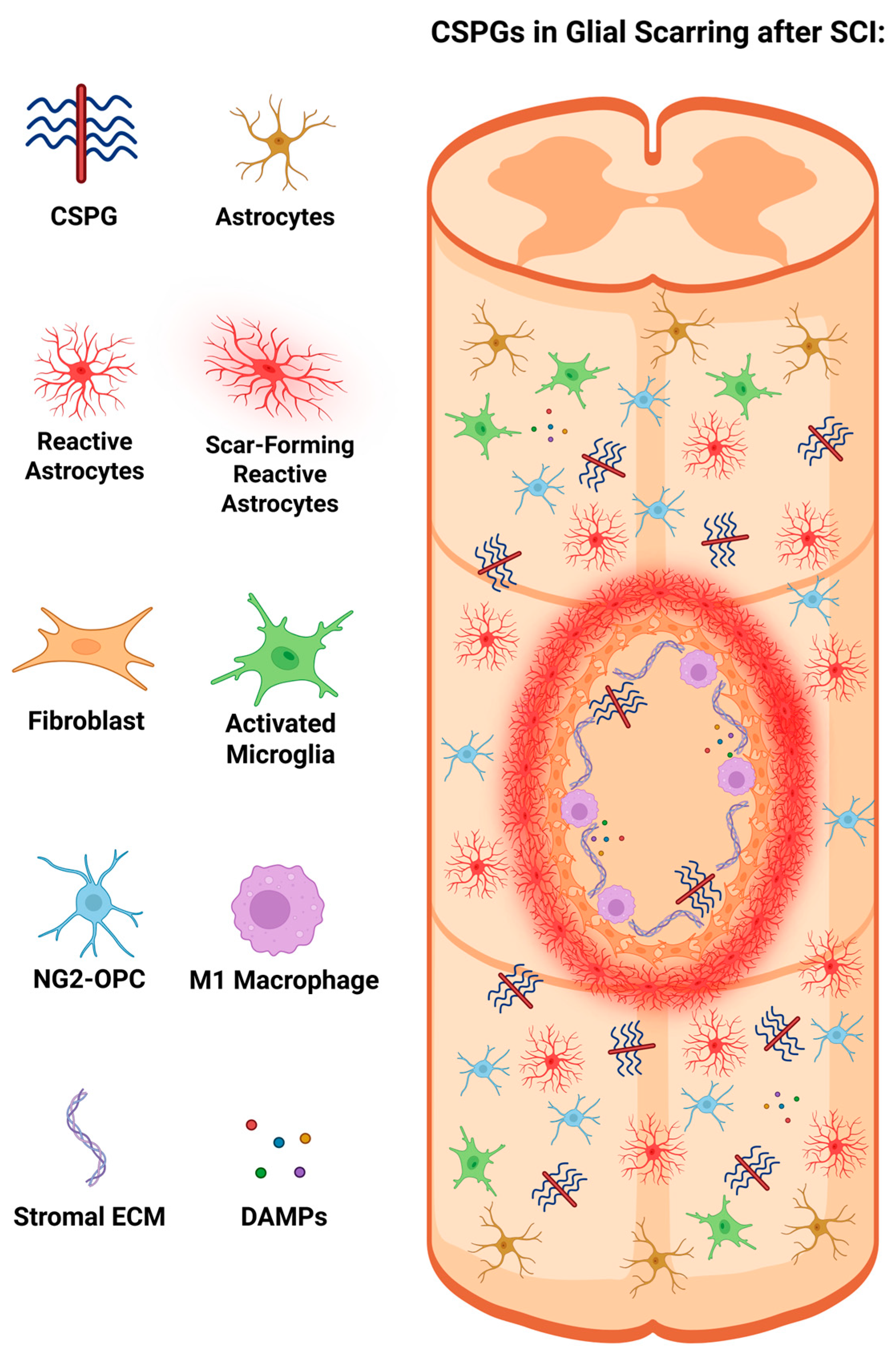

2. The Formation of Glial Scarring and CSPGs

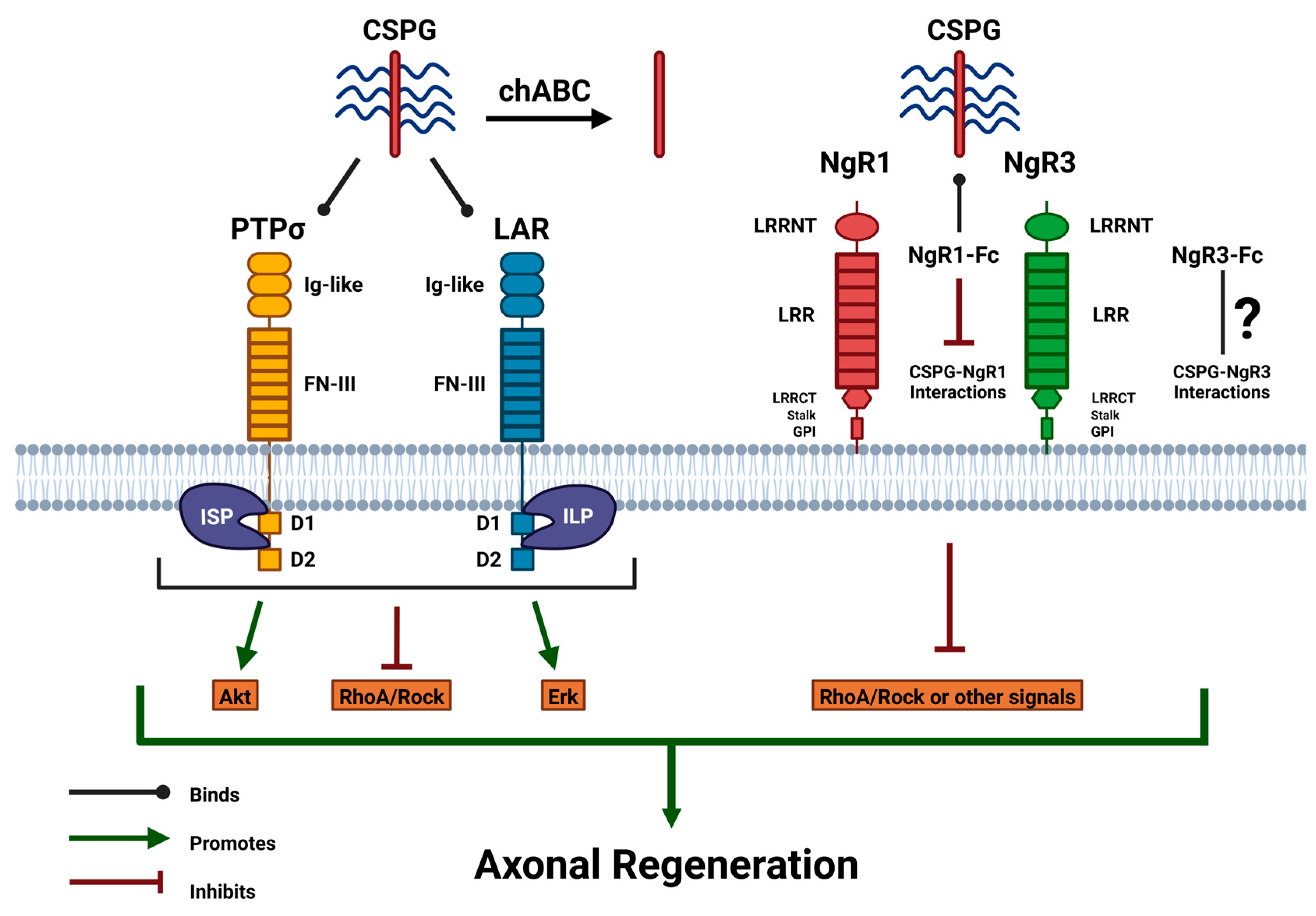

3. Delving into the Transmembrane Receptors of CSPG

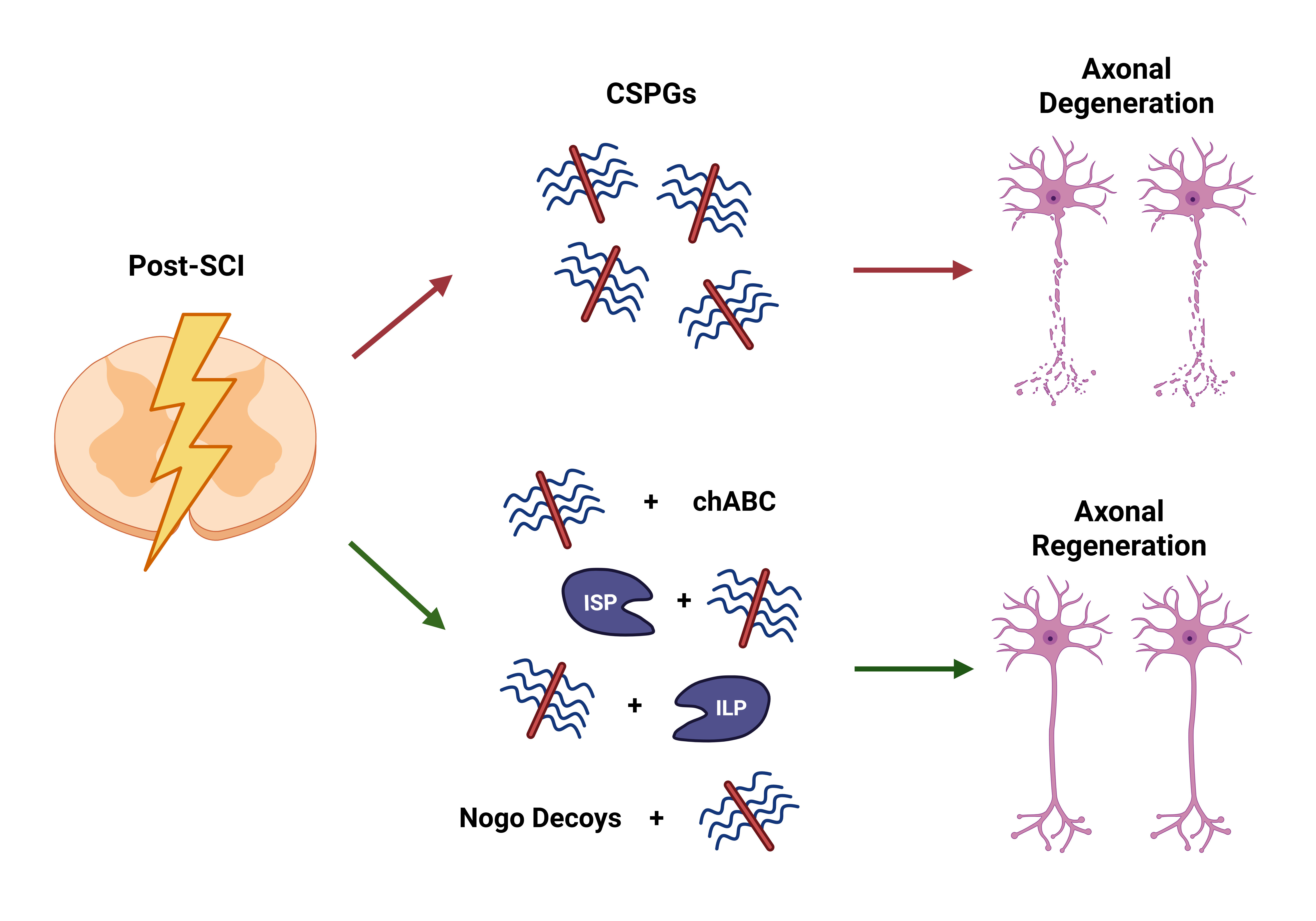

4. Overcoming CSPG-Mediated Inhibition with Therapeutic Strategies

4.1. Therapeutic with ChABC and Analyzing Its Development

4.2. Utilizing PTPσ and LAR Deletion to Target CSPG-Inhibition

4.3. Targeting the Effects of CSPG-PTPσ Interactions with ISP

4.4. Targeting the Effects of CSPG-LAR Interactions with ILP

4.5. Using ISP + ILP to Mediate CSPG-Inhibition

4.6. Targeting the Interactions of CSPG and Nogo

5. Discussion

5.1. Addressing Challenges and Opportunities in Current Therapeutic Research

5.2. Alternative Direction of Treatments for Regeneration

6. Conclusions

In the dynamic landscape of axonal regeneration research, the inhibitory effects of CSPG on glial scarring and axonal regeneration after SCI have been well-established as impediments to regeneration. This review discussed CSPG and its transmembrane receptors while highlighting studies of therapeutic options that inhibit CSPG extracellularly to promote axonal regrowth. It has been outlined that a widely known therapeutic established to inhibit CSPG in SCI has been chABC; however, it has been established that there have been limitations to this treatment. Therefore, other treatments that were discussed targeting transmembrane receptors were shown to be promising for regeneration. Certain possible therapeutics and combining certain therapeutic strategies were identified, however, more research is necessary to validate their efficacy. Modifying the intracellular pathway from a different therapeutic approach has also been mentioned as a possible regeneration approach with more investigation advised. Acknowledging the role of CSPG in SCI can address challenges, and elucidating these extracellular therapeutic strategies to overcome CSPG-mediated inhibition can harness the potential of these therapeutics to enhance axonal regeneration in the CNS and revolutionize SCI treatment.

Author Contributions

Funding

Data Availability Statement

Conflicts of Interest

Abbreviations

| CNS | Central Nervous System |

| PNS | Peripheral Nervous System |

| SCI | Spinal Cord Injury |

| CSPG | Chondroitin sulfate proteoglycan |

| ECM | Extracellular matrix |

| NG2 | Neuron-glial antigen 2 |

| OPC | Oligodendrocyte precursor cell |

| G1 | Globular domain at the N-terminus |

| G3 | Globular domain at the C-terminus |

| HA | Hyaluronan |

| GAG | Glycosaminoglycan |

| CS | Chondroitin sulfate |

| PTPσ | Protein tyrosine phosphatase sigma |

| LAR | Leukocyte common antigen-related |

| BBB | Blood-brain barrier |

| DAMP | Damage-associated molecular pattern |

| IGF-1 | Insulin-like growth factor 1 |

| GFAP | Glial fibrillary acidic protein |

| RPTPs | Receptor-type protein tyrosine phosphatases |

| Ig-like | Immunoglobulin-like |

| FN-III | Fibronectin type-III |

| HSPG | Heparan sulfate proteoglycan |

| HS | Heparan sulfate |

| NgR1 | Nogo receptor 1 |

| NgR2 | Nogo receptor 2 |

| NgR3 | Nogo receptor 3 |

| MAIs | Myelin-associated inhibitors |

| MAG | Myelin-associated glycoprotein |

| OMgp | Oligodendrocyte-myelin glycoprotein |

| LRR | Leucine-rich repeat |

| LRRNT | LRR proteins flanked N-terminally |

| LRRCT | LRR proteins flanked C-terminally |

| GPI | Glycosylphosphatidylinositol |

| ChABC | Chondroitinase ABC |

| CST | Corticospinal tract |

| WT | Wild-type |

| PTPσ (−/−) | PTPσ knockout |

| LAR (−/−) | LAR knockout |

| DRG | Dorsal root ganglion |

| ISP | Intracellular sigma peptide |

| ILP | Intracellular LAR peptide |

| CGN | Cerebellar granule neuron |

| NPC | Neural precursor cell |

| NgR1 (−/−) | NgR1 knockout |

| NgR3 (−/−) | NgR3 knockout |

| Fc | Fragment crystallizable |

| NgR1-Fc | NgR1 decoy merged with Fc region proteins |

| NgR3-Fc | NgR3 decoy merged with Fc region proteins |

| ONC | Optic nerve crush |

| RGC | Retinal ganglion cell |

| CSF | Cerebrospinal fluid |

| C3 | C3 transferase |

References

- Cajal, S.R. Degeneration and Regeneration of the Nervous System; Oxford University Press: New York, NY, USA, 1928. [Google Scholar]

- Huebner, E.A.; Strittmatter, S.M. Axon regeneration in the peripheral and central nervous systems. Results Probl. Cell Differ. 2009, 48, 339–351. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Sami, A.; Selzer, M.E.; Li, S. Advances in the signaling pathways downstream of glial-scar axon growth inhibitors. Front. Cell Neurosci. 2020, 14, 174. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Rhodes, K.E.; Fawcett, J.W. Chondroitin sulphate proteoglycans: preventing plasticity or protecting the CNS? J. Anat. 2004, 204, 33–48. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Avram, S.; Shaposhnikov, S.; Buiu, C.; Mernea, M. Chondroitin sulfate proteoglycans: structure-function relationship with implication in neural development and brain disorders. Biomed. Res. Int. 2014, 2014, 642798. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Kokenyesi, R.; Bernfield, M. Core protein structure and sequence determine the site and presence of heparan sulfate and chondroitin sulfate on syndecan-1. J. Biol. Chem. 1994, 269, 12304–12309. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Bourgeais, M.; Fouladkar, F.; Weber, M.; Boeri-Erba, E.; Wild, R. Chemo-enzymatic synthesis of tetrasaccharide linker peptides to study the divergent step in glycosaminoglycan biosynthesis. Glycobiology 2024, 34, cwae016. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Ohtake, Y.; Li, S. Molecular mechanisms of scar-sourced axon growth inhibitors. Brain Res. 2015, 1619, 22–35. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Yang, S.; Gigout, S.; Molinaro, A.; et al. Chondroitin 6-sulphate is required for neuroplasticity and memory in ageing. Mol. Psychiatry 2021, 26, 5658–5668. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Silver, J.; Miller, J.H. Regeneration beyond the glial scar. Nat. Rev. Neurosci. 2004, 5, 146–156. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Yang, T.; Dai, Y.; Chen, G.; Cui, S. Dissecting the dual role of the glial scar and scar-forming astrocytes in spinal cord injury. Front. Cell Neurosci. 2020, 14, 78. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Tran, A.P.; Warren, P.M.; Silver, J. New insights into glial scar formation after spinal cord injury. Cell Tissue Res. 2022, 387, 319–336. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Bradbury, E.J.; Burnside, E.R. Moving beyond the glial scar for spinal cord repair. Nat. Commun. 2019, 10, 3879. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Clifford, T.; Finkel, Z.; Rodriguez, B.; Joseph, A.; Cai, L. Current advancements in spinal cord injury research—glial scar formation and neural regeneration. Cells 2023, 12, 853. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Bellver-Landete, V.; Bretheau, F.; Mailhot, B.; et al. Microglia are an essential component of the neuroprotective scar that forms after spinal cord injury. Nat. Commun. 2019, 10, 518. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Gensel, J.C.; Zhang, B. Macrophage activation and its role in repair and pathology after spinal cord injury. Brain Res. 2015, 1619, 1–11. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Shibuya, S.; Yamamoto, T.; Itano, T. Glial and axonal regeneration following spinal cord injury. Cell Adhes. Migr. 2009, 3, 99–106. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Gaudet, A.D.; Fonken, L.K. Glial cells shape pathology and repair after spinal cord injury. Neurotherapeutics 2018, 15, 554–577. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Dias, D.O.; Göritz, C. Fibrotic scarring following lesions to the central nervous system. Matrix Biol. 2018, 68–69, 561–570. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Li, Z.; Yu, S.; Hu, X.; et al. Fibrotic scar after spinal cord injury: crosstalk with other cells, cellular origin, function, and mechanism. Front. Cell Neurosci. 2021, 15, 720938. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Liu, Y.; Jiang, H.; Qin, X.; Tian, M.; Zhang, H. PET imaging of reactive astrocytes in neurological disorders. Eur. J. Nucl. Med. Mol. Imaging 2022, 49, 1275–1287. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Wanner, I.B.; Anderson, M.A.; Song, B.; et al. Glial scar borders are formed by newly proliferated, elongated astrocytes that interact to corral inflammatory and fibrotic cells via STAT3-dependent mechanisms after spinal cord injury. J. Neurosci. 2013, 33, 12870–12886. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Anderson, M.A.; Burda, J.E.; Ren, Y.; et al. Astrocyte scar formation aids central nervous system axon regeneration. Nature 2016, 532, 195–200. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Zhang, G.; Jin, L.Q.; Rodemer, W.; Hu, J.; Root, Z.D.; Medeiros, D.M.; Selzer, M.E. The composition and cellular sources of CSPGs in the glial scar after spinal cord injury in the lamprey. Front. Mol. Neurosci. 2022, 15, 918871. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Karimi-Abdolrezaee, S.; Billakanti, R. Reactive astrogliosis after spinal cord injury—Beneficial and detrimental effects. Mol. Neurobiol. 2012, 46, 251–264. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Assinck, P.; Duncan, G.J.; Plemel, J.R.; et al. Myelinogenic plasticity of oligodendrocyte precursor cells following spinal cord contusion injury. J. Neurosci. 2017, 37, 8635–8654. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Filous, A.R.; Tran, A.; Howell, C.J.; et al. Entrapment via synaptic-like connections between NG2 proteoglycan+ cells and dystrophic axons in the lesion plays a role in regeneration failure after spinal cord injury. J. Neurosci. 2014, 34, 16369–16384. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Sharma, K.; Selzer, M.E.; Li, S. Scar-mediated inhibition and CSPG receptors in the CNS. Exp. Neurol. 2012, 237, 370–378. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Sclip, A.; Südhof, T.C. LAR receptor phospho-tyrosine phosphatases regulate NMDA-receptor responses. Elife 2020, 9, e53406. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Takahashi, H.; Craig, A.M. Protein tyrosine phosphatases PTPδ, PTPσ, and LAR: Presynaptic hubs for synapse organization. Trends Neurosci. 2013, 36, 522–534. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Xu, Y.; Fisher, G.J. Receptor type protein tyrosine phosphatases (RPTPs)—Roles in signal transduction and human disease. J. Cell Commun. Signal. 2012, 6, 125–138. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Ohtake, Y.; Wong, D.; Abdul-Muneer, P.M.; Selzer, M.E.; Li, S. Two PTP receptors mediate CSPG inhibition by convergent and divergent signaling pathways in neurons. Sci. Rep. 2016, 6, 37152. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Coles, C.H.; Shen, Y.; Tenney, A.P.; et al. Proteoglycan-specific molecular switch for RPTPσ clustering and neuronal extension. Science 2011, 332, 484–488. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Cornejo, F.; Cortés, B.I.; Findlay, G.M.; Cancino, G.I. LAR receptor tyrosine phosphatase family in healthy and diseased brain. Front. Cell Dev. Biol. 2021, 9, 659951. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Cheng, L.; Sami, A.; Ghosh, B.; et al. LAR inhibitory peptide promotes recovery of diaphragm function and multiple forms of respiratory neural circuit plasticity after cervical spinal cord injury. Neurobiol. Dis. 2021, 147, 105153. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Biersmith, B.H.; Hammel, M.; Geisbrecht, E.R.; Bouyain, S. The immunoglobulin-like domains 1 and 2 of the protein tyrosine phosphatase LAR adopt an unusual horseshoe-like conformation. J. Mol. Biol. 2011, 408, 616–627. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Xie, X.; Luo, L.; Liang, M.; Zhang, W.; Zhang, T.; Yu, C.; Wei, Z. Structural basis of liprin-α-promoted LAR-RPTP clustering for modulation of phosphatase activity. Nat. Commun. 2020, 11, 169. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Costa, G.; Ribeiro, F.F.; Sebastião, A.M.; Muir, E.M.; Vaz, S.H. Bridging the gap of axonal regeneration in the central nervous system: A state of the art review on central axonal regeneration. Front. Neurosci. 2022, 16, 1003145. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Dickendesher, T.L.; Baldwin, K.T.; Mironova, Y.A.; et al. NgR1 and NgR3 are receptors for chondroitin sulfate proteoglycans. Nat. Neurosci. 2012, 15, 703–712. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Giger, R.J.; Venkatesh, K.; Chivatakarn, O.; et al. Mechanisms of CNS myelin inhibition: Evidence for distinct and neuronal cell type specific receptor systems. Restor. Neurol. Neurosci. 2008, 26, 97–115. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Mukherjee, N.; Nandi, S.; Garg, S.; Ghosh, S.; Ghosh, S.; Samat, R.; Ghosh, S. Targeting chondroitin sulfate proteoglycans: An emerging therapeutic strategy to treat CNS injury. ACS Chem. Neurosci. 2020, 11, 231–232. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Bradbury, E.J.; Moon, L.D.; Popat, R.J.; et al. Chondroitinase ABC promotes functional recovery after spinal cord injury. Nature 2002, 416, 636–640. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Bradbury, E.J.; Carter, L.M. Manipulating the glial scar: chondroitinase ABC as a therapy for spinal cord injury. Brain Res. Bull. 2011, 84, 306–316. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- García-Alías, G.; Barkhuysen, S.; Buckle, M.; Fawcett, J.W. Chondroitinase ABC treatment opens a window of opportunity for task-specific rehabilitation. Nat. Neurosci. 2009, 12, 1145–1151. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Starkey, M.L.; Bartus, K.; Barritt, A.W.; Bradbury, E.J. Chondroitinase ABC promotes compensatory sprouting of the intact corticospinal tract and recovery of forelimb function following unilateral pyramidotomy in adult mice. Eur. J. Neurosci. 2012, 36, 3665–3678. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Hu, J.; Jin, L.Q.; Selzer, M.E. Inhibition of central axon regeneration: perspective from chondroitin sulfate proteoglycans in lamprey spinal cord injury. Neural Regen. Res. 2022, 17, 1955–1956. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Bartus, K.; James, N.D.; Didangelos, A.; et al. Large-scale chondroitin sulfate proteoglycan digestion with chondroitinase gene therapy leads to reduced pathology and modulates macrophage phenotype following spinal cord contusion injury. J. Neurosci. 2014, 34, 4822–4836. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Cafferty, W.B.; Yang, S.H.; Duffy, P.J.; Li, S.; Strittmatter, S.M. Functional axonal regeneration through astrocytic scar genetically modified to digest chondroitin sulfate proteoglycans. J. Neurosci. 2007, 27, 2176–2185. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Carter, L.M.; Starkey, M.L.; Akrimi, S.F.; Davies, M.; McMahon, S.B.; Bradbury, E.J. The yellow fluorescent protein (YFP-H) mouse reveals neuroprotection as a novel mechanism underlying chondroitinase ABC-mediated repair after spinal cord injury. J. Neurosci. 2008, 28, 14107–14120. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- McLean, J.; Batt, J.; Doering, L.C.; Rotin, D.; Bain, J.R. Enhanced rate of nerve regeneration and directional errors after sciatic nerve injury in receptor protein tyrosine phosphatase sigma knock-out mice. J. Neurosci. 2002, 22, 5481–5491. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Shen, Y.; Tenney, A.P.; Busch, S.A.; et al. PTPsigma is a receptor for chondroitin sulfate proteoglycan, an inhibitor of neural regeneration. Science 2009, 326, 592–596. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Fry, E.J.; Chagnon, M.J.; López-Vales, R.; Tremblay, M.L.; David, S. Corticospinal tract regeneration after spinal cord injury in receptor protein tyrosine phosphatase sigma deficient mice. Glia 2010, 58, 423–433. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Fisher, D.; Xing, B.; Dill, J.; et al. Leukocyte common antigen-related phosphatase is a functional receptor for chondroitin sulfate proteoglycan axon growth inhibitors. J. Neurosci. 2011, 31, 14051–14066. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Xu, B.; Park, D.; Ohtake, Y.; et al. Role of CSPG receptor LAR phosphatase in restricting axon regeneration after CNS injury. Neurobiol. Dis. 2015, 73, 36–48. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Lang, B.T.; Cregg, J.M.; DePaul, M.A.; et al. Modulation of the proteoglycan receptor PTPσ promotes recovery after spinal cord injury. Nature 2015, 518, 404–408. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Rink, S.; Arnold, D.; Wöhler, A.; et al. Recovery after spinal cord injury by modulation of the proteoglycan receptor PTPσ. Exp. Neurol. 2018, 309, 148–159. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Luo, F.; Wang, J.; Zhang, Z.; et al. Inhibition of CSPG receptor PTPσ promotes migration of newly born neuroblasts, axonal sprouting, and recovery from stroke. Cell Rep. 2022, 40, 111137. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Milton, A.J.; Kwok, J.C.; McClellan, J.; et al. Recovery of Forearm and Fine Digit Function After Chronic Spinal Cord Injury by Simultaneous Blockade of Inhibitory Matrix Chondroitin Sulfate Proteoglycan Production and the Receptor PTPσ. J. Neurotrauma 2023, 40, 2500–2521. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Wang, H.; Feng, N.; Liu, C.; et al. Inhibition of CSPG-PTPσ Activates Autophagy Flux and Lysosome Fusion, Aids Axon and Synaptic Reorganization in Spinal Cord Injury. Mol. Neurobiol. 2025, 62, 773–785. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Dyck, S.; Kataria, H.; Alizadeh, A.; Santhosh, K.T.; Lang, B.; Silver, J.; Karimi-Abdolrezaee, S. Perturbing chondroitin sulfate proteoglycan signaling through LAR and PTPσ receptors promotes a beneficial inflammatory response following spinal cord injury. J. Neuroinflammation 2018, 15, 90. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Hosseini, S.M.; Alizadeh, A.; Shahsavani, N.; Chopek, J.; Ahlfors, J.E.; Karimi-Abdolrezaee, S. Suppressing CSPG/LAR/PTPσ axis facilitates neuronal replacement and synaptogenesis by human neural precursor grafts and improves recovery after spinal cord injury. J. Neurosci. 2022, 42, 3096–3121. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Wang, X.; Hasan, O.; Arzeno, A.; Benowitz, L.I.; Cafferty, W.B.; Strittmatter, S.M. Axonal regeneration induced by blockade of glial inhibitors coupled with activation of intrinsic neuronal growth pathways. Exp. Neurol. 2012, 237, 55–69. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Walker, B.A.; Ji, S.J.; Jaffrey, S.R. Intra-axonal translation of RhoA promotes axon growth inhibition by CSPG. J. Neurosci. 2012, 32, 14442–14447. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Wang, X.; Zhou, T.; Maynard, G.D.; Terse, P.S.; Cafferty, W.B.; Kocsis, J.D.; Strittmatter, S.M. Nogo receptor decoy promotes recovery and corticospinal growth in non-human primate spinal cord injury. Brain 2020, 143, 1697–1713. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Maynard, G.; Kannan, R.; Liu, J.; et al. Soluble Nogo-receptor-Fc decoy (AXER-204) in patients with chronic cervical spinal cord injury in the USA: A first-in-human and randomised clinical trial. Lancet Neurol. 2023, 22, 672–684. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Zhang, Y.; Yang, S.; Liu, C.; Han, X.; Gu, X.; Zhou, S. Deciphering glial scar after spinal cord injury. Burns Trauma 2021, 9, tkab035. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Mencio, C.P.; Hussein, R.K.; Yu, P.; Geller, H.M. The role of chondroitin sulfate proteoglycans in nervous system development. J. Histochem. Cytochem. 2021, 69, 61–80. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Muir, E.; De Winter, F.; Verhaagen, J.; Fawcett, J. Recent advances in the therapeutic uses of chondroitinase ABC. Exp. Neurol. 2019, 321, 113032. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Burnside, E.R.; De Winter, F.; Didangelos, A.; et al. Immune-evasive gene switch enables regulated delivery of chondroitinase after spinal cord injury. Brain 2018, 141, 2362–2381. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Parrasia, S.; Szabò, I.; Zoratti, M.; Biasutto, L. Peptides as pharmacological carriers to the brain: Promises, shortcomings and challenges. Mol. Pharm. 2022, 19, 3700–3729. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Wang, L.; Wang, N.; Zhang, W.; et al. Therapeutic peptides: Current applications and future directions. Signal Transduct. Target. Ther. 2022, 7, 48. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Elsayed, Y.Y.; Kühl, T.; Imhof, D. Regulatory guidelines for the analysis of therapeutic peptides and proteins. J. Pept. Sci. 2025, 31, e70001. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Monnier, P.P.; Sierra, A.; Schwab, J.M.; et al. The Rho/ROCK pathway mediates neurite growth-inhibitory activity associated with the chondroitin sulfate proteoglycans of the CNS glial scar. Mol. Cell. Neurosci. 2003, 22, 319–330. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Fujita, Y.; Yamashita, T. Axon growth inhibition by RhoA/ROCK in the central nervous system. Front. Neurosci. 2014, 8, 338. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Zhang, Y.; Wang, X.; Jiang, C.; et al. Rho kinase inhibitor Y27632 improves recovery after spinal cord injury by shifting astrocyte phenotype and morphology via the ROCK/NF-κB/C3 pathway. Neurochem. Res. 2022, 47, 3733–3744. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Geoffroy, C.G.; Lorenzana, A.O.; Kwan, J.P.; et al. Effects of PTEN and Nogo codeletion on corticospinal axon sprouting and regeneration in mice. J. Neurosci. 2015, 35, 6413–6428. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Liu, S.; Jia, J.; Zhou, H.; et al. PTEN modulates neurites outgrowth and neuron apoptosis involving the PI3K/Akt/mTOR signaling pathway. Mol. Med. Rep. 2019, 20, 4059–4066. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Poulopoulos, A.; Murphy, A.J.; Ozkan, A.; Davis, P.; Hatch, J.; Kirchner, R.; Macklis, J.D. Subcellular transcriptomes and proteomes of developing axon projections in the cerebral cortex. Nature 2019, 565, 356–360. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Huang, H.; Miao, L.; Yang, L.; et al. AKT-dependent and -independent pathways mediate PTEN deletion-induced CNS axon regeneration. Cell Death Dis. 2019, 10, 203. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Wang, Q.; Fan, H.; Li, F.; Skeeters, S.S.; Krishnamurthy, V.V.; Song, Y.; Zhang, K. Optical control of ERK and AKT signaling promotes axon regeneration and functional recovery of PNS and CNS in Drosophila. Elife 2020, 9, e57395. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

| Therapeutic Name | Primary Target(s) | Mechanism of Action | Findings | References |

| ChABC | CSPG | Degrades the CS-GAG chains on CSPGs, removing the inhibitory properties of CSPG. | Promotes axonal regeneration, enhances neuroplasticity, and provides functional recovery in various SCI models. | [42,44,45,47,48,49] |

| PTPσ (−/−) | PTPσ Receptor | Knockout of PTPσ to inhibit CSPG-PTPσ interactions. | Enhances neural outgrowth to the lesion area and regeneration in CST axons. | [50,51,52] |

| LAR (−/−) | LAR Receptor | Knockout of LAR to inhibit CSPG-LAR interactions. | Augmented neurite regrowth with improving locomotor function and mitigating the activation of the RhoA/ROCK pathway. | [53,54] |

| ISP | PTPσ Receptor | Targets the intracellular domains of PTPσ to prevent inhibitory effects of CSPG-PTPσ interactions. | Regrowth of serotonergic fibers with functional recovery, along with axonal sprouting and neuroblast migration. | [55,56,57,58,59] |

| ILP | LAR Receptor | Targets the intracellular domains of LAR to prevent inhibitory effects of CSPG-LAR interactions. | Improved regeneration of neurite growth with enhanced axonal sprouting, Akt phosphorylation, and RhoA/ROCK reduction. | [53,54] |

| ISP + ILP | PTPσ and LAR Receptors | Combined treatment inhibits the effects of both CSPG-PTPσ and CSPG-LAR interactions. | Enhanced axonal density and neurite length, along with suppression of astrocyte differentiation. | [60,61] |

| NgR1 (−/−) & NgR3 (−/−) | NgR1 and NgR3 Receptors | Knockout of Nogo Receptors that mediate CSPG properties (NgR1 & NgR3) to inhibit CSPG-Nogo interactions. | Attenuated CSPG levels and promoted regeneration of RGC axons after induced ONC in models. | [39,62] |

| NgR1-Fc (AXER-204) | NgR1 Receptor Ligands | NgR1-Fc is a decoy that can bind to MAIs and CSPGs to inhibit their inhibitory properties. | Permitting growth beyond the lesion site with amplifying growth in CST axons and catalyzing neural repair. | [62,64,65] |

Disclaimer/Publisher’s Note: The statements, opinions and data contained in all publications are solely those of the individual author(s) and contributor(s) and not of MDPI and/or the editor(s). MDPI and/or the editor(s) disclaim responsibility for any injury to people or property resulting from any ideas, methods, instructions or products referred to in the content. |

© 2025 by the authors. Licensee MDPI, Basel, Switzerland. This article is an open access article distributed under the terms and conditions of the Creative Commons Attribution (CC BY) license (http://creativecommons.org/licenses/by/4.0/).