1. Introduction

Soil zinc (Zn) availability affects not only the grain yield but also grain Zn concentration, a nutritional quality index of crop. About 17% of the global population has insufficient intake of Zn, an essential micronutrient for maintaining human health [

1]. Achieving Zn biofortification target in wheat is of great significance in reducing Zn deficiency related diseases as wheat grain is an important source of Zn nutrition for human. The Zn concentrations in wheat grain under most fields however are below the proposed biofortification target 40 mg/kg[

2,

3]. The journey of Zn translocation from soil to grain is affected by intrinsic genetic factors of crop genotype, soil property, and agronomic practices. Correspondingly, breeding and agronomic management are two approaches that could offer potential approaches towards increasing Zn concentration of wheat grain. Genetic variation among genotypes provides opportunities for genetic improvement by traditional breeding and/or manipulation of genes responsible for Zn transport is of promise to increase grain Zn content[4-8]. On the other hand, agronomic approach such as Zn fertilizer management (foliar and/or soil application) and inoculation of Zn-solubilizing bacteria can play positive effects on improving grain Zn concentration[9-11]

The total Zn content in soil varies largely, from 2 to 3548 mg/kg, with a mean of 64 mg/kg globally [

12]. Different forms of Zn are present in soil, with Zn

2+, ZnOH

+, and soluble organic Zn are assumed to be easily taken up by plants [

12]. Zn fraction extracted by Diethylene Triamine Penta Acetic acid (DTPA) [

13] or Mehlich No.3[

14] are often used to indicate available Zn in agricultural system. The Zn availability in soil could be affected by soil property such as soil pH, organic matter content, and soil texture. Soil pH is a key factor affecting solubility, ionic form, adsorption, and mobility of plant nutrients including Zn [

15,

16]. Zn availability tends to be high in soils with a neutral pH. Low Zn availability can occur in acid soils (pH 5-6.5), and at environments with a higher pH [

3,

12]. Soil organic matter also affects Zn translocation in the soil—crop system. Increased soil organic matter may lead to increased adsorption of Zn, hence reducing Zn availability[

17]. On the other hand, the Zn availability may be increased with increased soil organic matter content due to formation of soluble organic Zn complexes or soil organic matter mineralization[

18,

19]. So, whether the increased soil organic content can result in higher soil Zn availability depends on the interaction between soil and added soil organic matter. In general, a moderate addition of organic matter into soil can increase grain Zn content [

20], but high content (>3%) of organic matter can also cause Zn deficiency in crops [

12]. A recent study showed Zn availability was mostly driven by soil property rather than by fertilization [

21]. Thus, a balance between organic content with soil Zn status [

22], together with considering of soil property, is required towards reaching a higher grain yield and/or grain Zn concentration. Soil texture can affect Zn availability by influencing the water-holding capacity and aeration of soil, as well as the adsorption and desorption of Zn. Sandy soils with low water-holding capacity and poor cation exchange capacity tend to have higher available Zn content than clay soils. A survey conducted in Europe indicated that clay content explained the most variation of the overall distribution of soil Zn, and coarser soil was associated with lower Zn concentrations [

23].

Other ions in soil, such as calcium, iron, and phosphorus, can compete with Zn for uptake by plants, leading to reduced Zn availability. In particular, high levels of phosphorus in soil can inhibit Zn uptake by plants. The possible soil and biological mechanisms for this includes: 1) soluble phosphorus fractions in soil reacts with Zn

2+ to form insoluble Zn

3 (PO

4)

2, reducing the availability of both phosphorus and Zn [

24]; 2) Zn

3 (PO

4)

2 may also be generated in the root system, which limits the transport of zinc from root to shoot and grain; 3) a higher phosphorus application dose leads to changes in soil pH, arbuscular mycorrhizal colonization, root exudates, and the spatiotemporal expression of Zn transporters, reducing the availability of Zn and phosphorus [25-28]. Application of nitrogen fertiliser in a proper dose, on the other hand, had been shown to improve Zn utilization in wheat in terms of higher grain yield and/or grain Zn concentration [

29].

The Zn in wheat grain originates from two parts: the transfer process from post-anthesis canopy leaves to grains, the uptake process from soil by roots [

30]. Obviously, proper Zn application in soil can increase soil available Zn concentration thereby enhance the Zn translocation from soil to wheat plants [

31]; Foliar Zn application mainly increases the transfer of Zn from canopy leaves to grains. The Zn translocation process in soil-wheat system is regulated by the level of soil available Zn content. For instance, Liu et al. (2019) found that grain Zn denpended mainly on the uptake process from the soil when soil DTPA–Zn was greater than 7.15 mg/kg, while the remobilization from the post-anthesis canopy leaves to the grains played as the main source when the soil Zn content was low.

Coastal soils often exhibit a higher content of salt and/or higher pH due to shallow groundwater tables, particularly for those in semi-arid and arid climates due to limited rainfall, and high evaporation rates. Consequently, high salt content present in saline soil could interfere with the Zn uptake process, resulting in a reduced Zn accumulation in wheat plant [

32]. Coastal saline land is important resource for agriculutral exploitation, take Yellow River Delta region in China for example, screening better genotypes of crops and pastures tailored to the saline land had been formulated as a national strategy. To date, how coastal soil property affect the soil Zn availability thereby the Zn translocation process in the soil—wheat system have not been fully understood. The current study was thus conducted with the following objectives 1): examine the correlation of soil natural Zn supply level with Zn translocation from coastal soil to wheat mediated by soil property, 2): examine the effects of soil and foliar Zn application on different wheat genotypes under coastal saline soils.

2. Results

2.1. Zn Translocation from Soil to Wheat Plant as Mediated by Soil Property

Large variations were observed as anticipated for the measured soil property parameters among 30 soil samples collected from different locations of Yellow River Delta region Error! Reference source not found.). PCA anaylsis using 16 measured soil chemical parameters showed that variations could be explained 52.69% by first two principle components, with PC1 and PC2 accounted for 33.57% and 19.12% respectively (Supplementary Fig S1). PC1 mainly represented the ground nutritional status as manifested by concentrations of total N, total P, total Mg, total Ca, total K. PC2 mainly represented the bio-availablility of nutrients as manifested by Ammonia-N, Nitrate-N, Olsen-P, and DTPA-Zn/total Zn (Supplementary Fig S1).

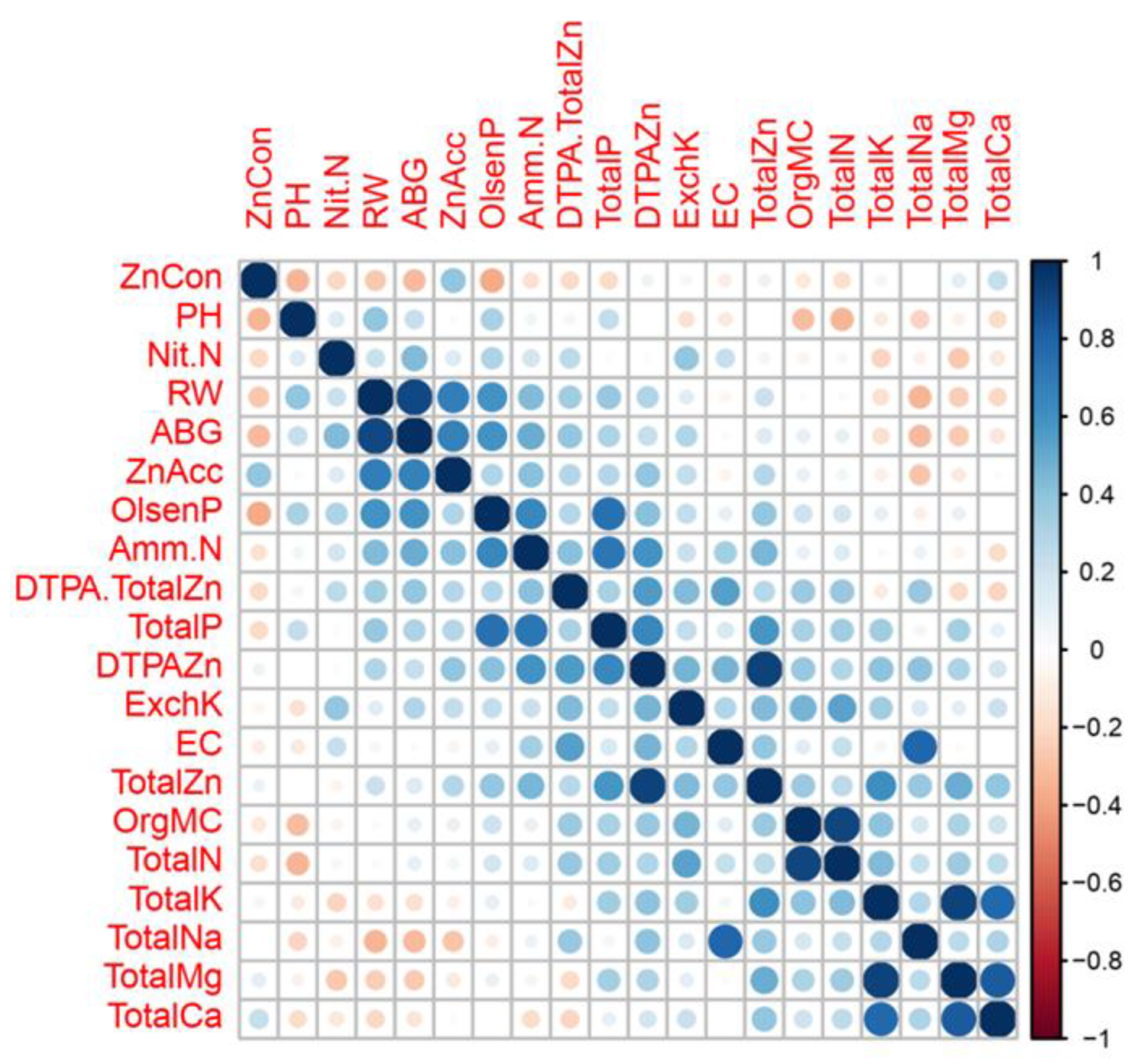

Correlation analysis (

Figure 1) showed soil DTPA-Zn concentration positively correlated with soil total Zn concentration (r=0.59, p<0.01), EC (r=0.47, p<0.01), organic matter content (r=0.38, p<0.05), soil total P concentration (r=0.64, p<0.01), soil total K (r=0.40, p<0.05), ammonia-N (r=0.60, p<0.01), Olsen-P (r=0.42, p<0.05), and exchangeable K (r=0.47, p<0.01). The ratio of DTPA-Zn/total Zn positively correlated with soil EC (r=0.49, p<0.01) and negatively correlated with soil total Mg concentration (r=-0.42, p<0.05).

Growth of wheat plant in terms of aboveground biomass and root dry weight measured at 8-weeks post transplanting was significantly different among treatments using above 30 soils (p<0.01). The aboveground biomass varied from 328.0 to 1729.0 mg/pot, while root dry weight varied from 49.0 to 365.0 mg/pot. Similarly, Zn concentration of aboveground plant (p<0.01) and total Zn accumulation amount of aboveground plant (p<0.01) were also significantly different. Zn concentration of aboveground plant, and total Zn accumulation amount of aboveground plant were 24.8 to 116.6 mg/kg, and 11.0 to 111.4 μg/pot, respectively.

Table 1.

Measured Soil Property Parameters of 30 Soil Samples.

Table 1.

Measured Soil Property Parameters of 30 Soil Samples.

| Measured Soil Chemical Parameters |

Average±SD |

Minmum Value |

Median Value |

| pH |

7.32 ± 0.64 |

6.25 |

7.49 |

| EC (dS/m) |

5.76 ± 5.17 |

1.02 |

3.42 |

| Organic matter content (g/kg) |

12.73 ± 6.86 |

3.70 |

12.40 |

| Total Na (g/kg) |

0.52 ± 0.32 |

0.23 |

0.41 |

| Total N (g/kg) |

0.75 ± 0.40 |

0.10 |

0.72 |

| Total P (g/kg) |

0.84 ± 0.35 |

0.48 |

0.75 |

| Total K (g/kg) |

2.37 ± 0.91 |

0.96 |

2.24 |

| Total Ca (g/kg) |

32.80 ± 5.42 |

24.36 |

30.82 |

| Total Mg (g/kg) |

8.60 ± 1.72 |

5.70 |

8.56 |

| Ammonia N (g/kg) |

0.12 ± 0.12 |

0.02 |

0.10 |

| Nitrate N (mg/kg) |

53.49 ± 80.49 |

12.34 |

35.00 |

| Olsen-P (mg/kg) |

40.46 ± 11.35 |

24.90 |

36.20 |

| Exchangeable K(mg/kg) |

192.06 ± 71.88 |

68.64 |

186.75 |

| Total Zn (mg/kg) |

58.14 ± 57.52 |

14.60 |

44.25 |

| DTPA-Zn (mg/kg) |

3.29 ± 5.65 |

0.60 |

1.60 |

| DTPA-Zn/ Total Zn (%) |

4.88 ± 2.97 |

1.34 |

3.55 |

The relationships among plant growth, Zn accumulation and soil property were also revealed in correlation analysis (

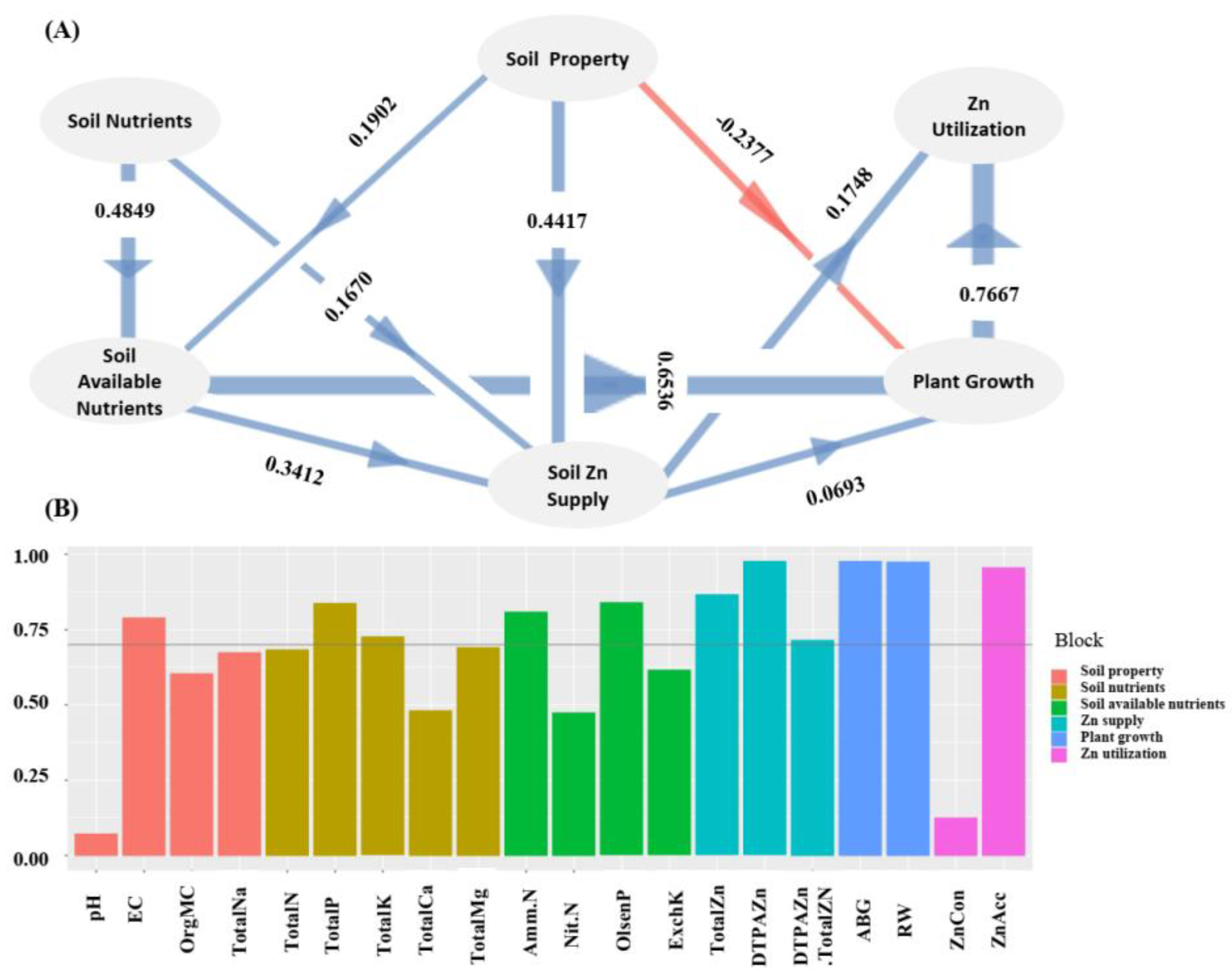

Figure 1). Zn concentration in wheat seedling plant was negatively correlated with soil pH (r=-0.3365, p=0.07) and Olsen-P (r=-0.3749, p<0.05). ABG correlated positively with RW (r=0.91, p<0.01), both ABG (r=-0.41, p<0.05) and RW were negatively (r=-0.46, p<0.01) correlated with soil Na concentration. Total Zn accumulation in aboveground plant was positively correlated with soil DTPA-Zn concentration (r=0.39, p<0.05), Zn concentration in aboveground plant (r=0.37, p<0.05), ABG (r=0.70, p<0.01), and RW (r=0.71, p<0.01). Based on these correlations, it was assumed that Zn utilization in wheat could be affected by plant growth, soil Zn supply, soil property, soil nutrients, and soil available nutrients. To test this hypothesis, a PLS-PM model with six latent variables ‘plant growth’, ‘soil Zn supply’, ‘soil property,’, ‘soil nutrients’, ‘soil available nutrients’, and ‘Zn utilization’ were constructed. In deed, soil Zn supply and plant growth had direct effects on Zn utilization in wheat as revealed in the established PLS-PM model (

Figure 2). Soil property, soil nutrients, and soil available nutrients had indirect effectes on Zn utilization in wheat by affecting soil Zn supply and/or plant growth.

2.2. The effects of Zn Application on Wheat Zn Accumulation Mediated by Soil Salinity

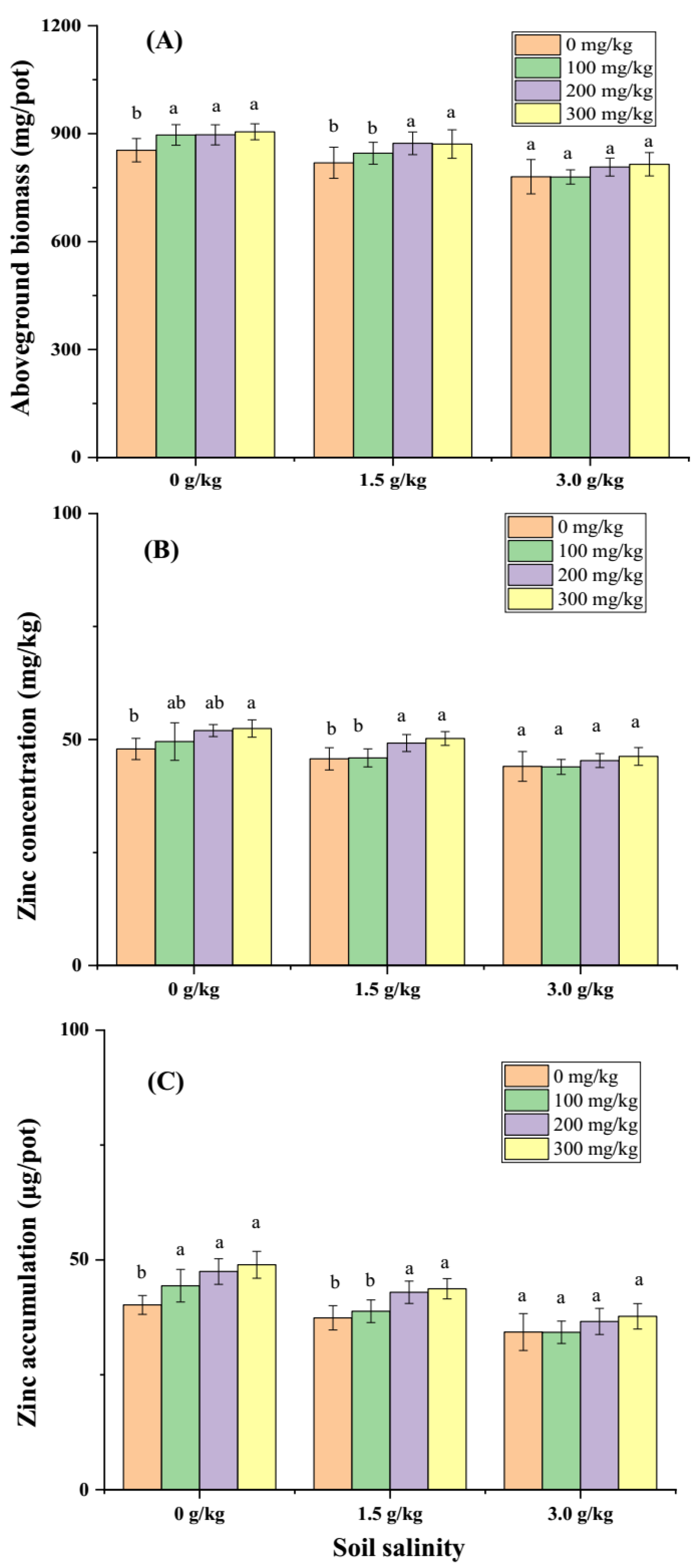

Salinity significantly affected aboveground biomass, Zn concentration of aboveground plant, and Zn total accumulation amount of aboveground plant measured at 8 weeks post-transplanting. Soil Zn application (100, 200, 300 mg/kg) increased aboveground biomass and Zn concentration under no artificial imposed salinity (0 g/kg NaCl) and slight salinity treatments (1.5 g/kg NaCl) relative to no Zn application, but no further boosting effect was observed at salinity of 3.0 g/kg NaCl (

Figure 3A, B). Total Zn accumulation was increased by 100, 200, 300 mg/kg Zn application at condition without artifical imposed salinity, while it was increased by a higher Zn application level (200, 300 mg/kg) at salinity of 1.5 g/kg NaCl. Zn application did not further increase total Zn accumulation in plant relative to no Zn application at salinity of 3.0 g/kg NaCl.

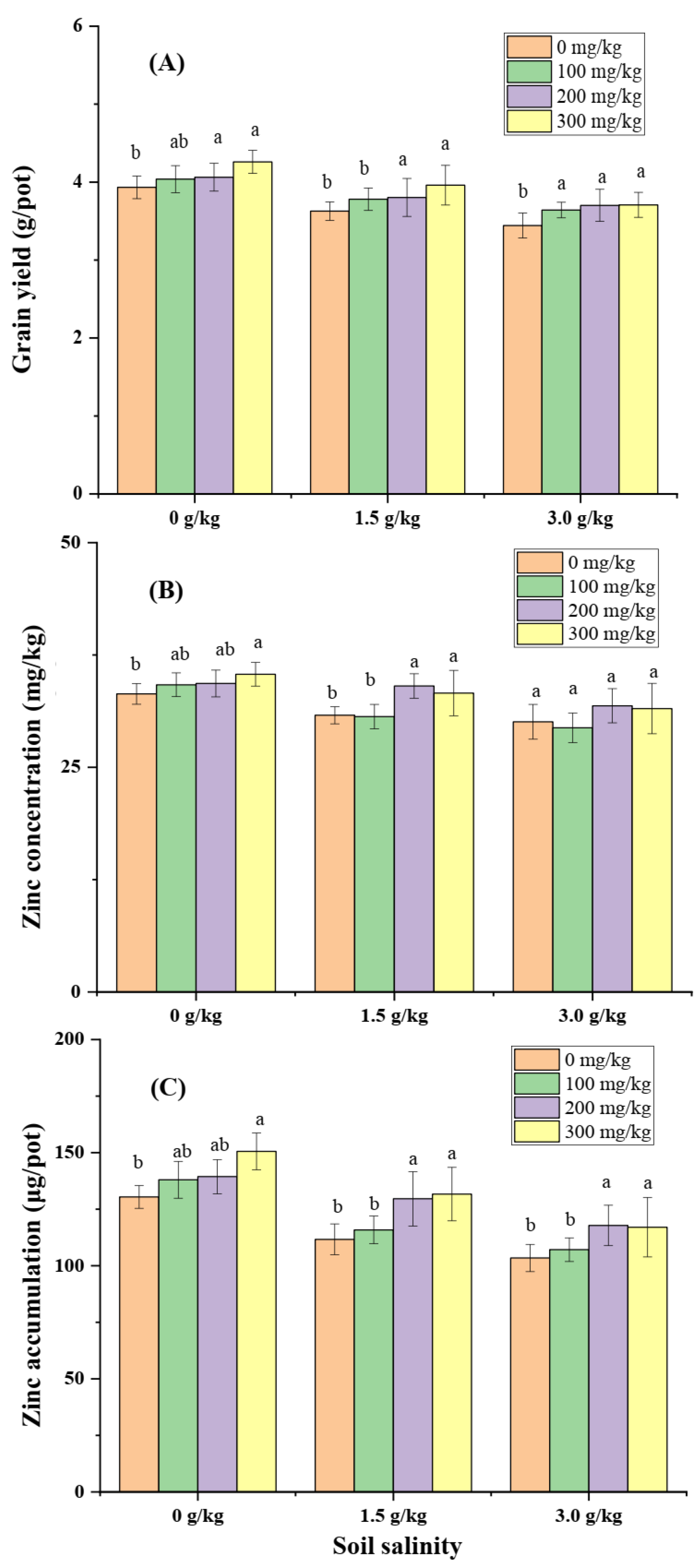

Grain yield, grain Zn concentration, and total Zn accumulation in grain measured at maturity were significantly reduced by artificial imposed salinity (Error! Reference source not found.). Soil Zn application (100, 200, 300 mg/kg) increased grain yield relative to no Zn application at all three salinity levels (Error! Reference source not found.A). Grain Zn concentration was increased by soil Zn application at salinity of 0, 1.5 g/kg NaCl (Error! Reference source not found.B), but no significant change at salinity of 3.0 g/kg NaCl. Total Zn accumulation in grain was significantly increased by Zn application particularly at dose of 200, and 300 mg/kg ZnSO4 (Error! Reference source not found.C).

Figure 4.

Grain yield, grain Zn concentration, and Zn accumulation in grain measured at maturity grown under three salinity (NaCl added into soil as 0 g, 1.5 g, and 3.0 g per 1 kg soil) and four Zn application levels (ZnSO4 added into soil as 0 mg, 100 mg, 200 mg, and 300 mg per 1 kg soil).

Figure 4.

Grain yield, grain Zn concentration, and Zn accumulation in grain measured at maturity grown under three salinity (NaCl added into soil as 0 g, 1.5 g, and 3.0 g per 1 kg soil) and four Zn application levels (ZnSO4 added into soil as 0 mg, 100 mg, 200 mg, and 300 mg per 1 kg soil).

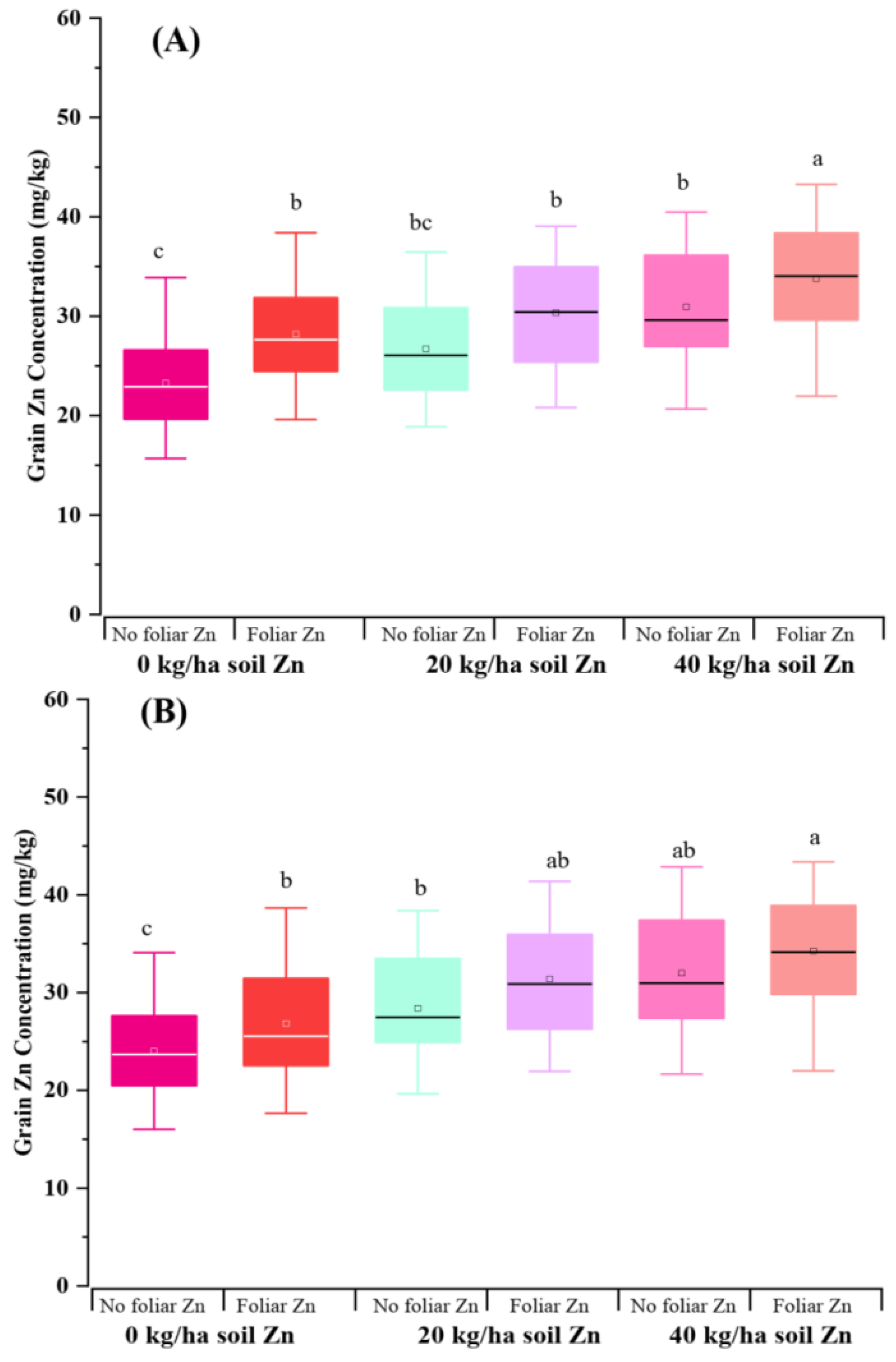

2.3. Effect of Soil and Foliar Zn Application on Wheat Grain Yield and Grain Zn Concentration in Coastal Saline Field

Effectiveness of soil and foliar Zn application on 20 wheat genotypes was further investigated on a field with low Zn availablity. Soil Zn application significantly increased grain yield relative to control treatment (0 kg/ha ZnSO

4) at both two growth seasons, with 40 kg/ha ZnSO

4 application achieved highest average grain yield, 5.36 t/ha in 2020-2021 season, and 5.53 t/ha in 2021-2022 season (Supplementary Fig S2). However, within a given soil Zn level, foliar Zn application did not further increase grain yield (Supplementary Fig S3). Soil Zn application increased the average grain Zn concentration of 20 wheat genotypes (Fig S4). By contrast, the effectiveness of foliar application showed to be dependent on the dose of soil Zn application. Foliar Zn application increased grain Zn concentration significantly under the condition 0 kg/ha soil Zn application, but not for condition under 20 kg/ha or 40 kg/ha soil Zn application (Figure 4). On the other hand, significantly genotypic difference was also observed in terms of grain yield and grain Zn concentration (

Supplementary Table S1).

Figure 4.

Grain Zn concentration of 20 wheat genotypes grown at three soil Zn levels (ZnSO4 added into soil as 0 kg/ha, 20 kg/ha, and 40 kg/ha) and two foliar Zn levels (No foliar application, and foliar application) under saline field conditions in 2020-2021 (A), and 2021-2022 (B) seasons.

Figure 4.

Grain Zn concentration of 20 wheat genotypes grown at three soil Zn levels (ZnSO4 added into soil as 0 kg/ha, 20 kg/ha, and 40 kg/ha) and two foliar Zn levels (No foliar application, and foliar application) under saline field conditions in 2020-2021 (A), and 2021-2022 (B) seasons.

3. Discussion

3.1. Zn Translocation from Soil to Wheat Mediated by Soil Property

Soil Zn availability are closely associated with the soil property (pH, organic matter content, soil nitrogen and phosphorus content, etc.) [

33]. Releasing capability of nutrients from soil to solution, can be estimated by measuring soil available concentration of nutrient such as N, P, K, and Zn. DTPA-Zn concentration positively correlated with ammonia-N, Olsen-P, and exchangeable K in our study, suggetsing a soil with higher availability of N, P, K has a tendency to be more Zn available. The soil Zn concentration positively correlated with available P when available P concnetration did not exceed 150 mg/kg [

34]. Consistently, DTPA-Zn concentration positively correlated with Olsen-P concentration, which varied from 24.90 mg/kg to 60.40 mg/kg in our current study.

Soil organic matter and pH were two indexes among investigated soil properties that correlated best with the distribution of Zn forms in soils [

35]. The correlation between soil available Zn and organic matter also varies with the change of soil organic matter conentration. An increase of organic matter concentration within a certain extent could increase soil Zn concentration [

20]. However, an increase in organic matter concentraiton exceeding 90 g/kg resulted in reuction of Zn concontration [

34]. Organic matter content which varied from 3.70 to 36.10 g/kg in current study, as anticipated, it was positively correlated with DTPA-Zn concentration. The correlation between pH and soil available Zn concentration in current study was non-significant and weak, this might be due to the narrow pH range (6.25-8.35) of the soils used in this study.

The interactions between soil factors and wheat plant are complex and may vary depending on the soil property and wheat gentoype. The difference in soil property thereby could partially contribute to the variation of grain Zn concentration in crop grown under different locations[36-38]. As anticipated, the Zn concentration in wheat plants grown under different soils varied largely in current study. Higher pH often leads to a decrease in Zn availability [

3,

12]. Consistently, Zn concentration in wheat seedling plant in current study was negatively correlated with soil pH, suggesting a reduced availability to plants caused by a higher pH. Besides, Zn concentration in wheat seedling plant showed a negative correlation with soil Olsen-P concentration increasing, which was in agreement with [

39] in which reduced soil available P was associated with higher grain Zn concentrations.

Zn accumulation in plant depends on the capability to assimilate the uptaken Zn into dry matter. Total Zn accumulation amount in plant correlated positively with aboveground biomass in this current study, suggesting a better growth performance promoted Zn uptake. Besides, total Zn accumulation in aboveground plant was positively correlated with soil DTPA-Zn concentration, suggesting soil Zn supply levels had significantly effect on Zn accumulation, consistent with Recena et al. (2021) which showed the available Zn is relevant in explaining Zn uptake by plants. On contray, no relationship was found between Zn uptake by plants and the DTPA-Zn in the research of Moreno-Lora and Delgado (2020). The disagreement might be due to the soil DTPA-Zn concentration in our study had a larger span, and was higher on average relative to that in Moreno-Lora and Delgado (2020).

Clarifying the relationship among soil property, Zn availability, and Zn utilization would be helpful for making suitable measure to improve Zn translocation from soil to plant. The established PLS-PM model supported that soil Zn supply and plant growth had direct effects on Zn utilization in wheat, while soil property, soil nutrients, and soil available nutrients had indirect effectes on Zn utilization in wheat by affecting soil Zn supply and/or plant growth. This model suggested soil Zn supply level and plant growth were two factors directly related to Zn utilization, while soil property, soil nutrients, and soil available nutrients were indirectly related.

3.2. Effectiveness of Zn Application on Zn Translocation from Soil to Wheat Mediated by Salt Stress

Insufficient Zn supply resulted in reduced water usage, delayed head emergence, and depressed grain yield of Zn-inefficient wheat genotype [

41]. Application of Zn fertilizer to soils with low Zn supply level is therefore a key approach to support plant normal growth and satisfactory grain yield. Proper soil Zn application could enhance Zn translocation from soil to plant, however, the effectiveness of soil Zn application was denpendent on soil natural Zn level. Zn fertilizer explained most of the Zn uptake by crops in Zn-deficient soils, Zn application may not significantly affect grain yield under soils with sufficient Zn [

42]. Soil Zn application at higher dose (200, 300 mg/kg) increased grain yield at all three salinity levels in current pot study, suggesting Zn availability of original soils combined with salinity was insufficient. Grain Zn concentration was increased significantly by imposing a dose of 300 mg/kg Zn at salinity level of 0 g/kg, and 1.5 g/kg.

Similarly, effectiveness of foliar Zn application on grain yield and grain Zn concentration was also dependent on soil natural Zn level. Foliar did not increase grain yield while significantly improved the grain Zn concentration of wheat by 28% and 89% in Zn non-deficient soils [

43]. Foliar Zn application did not further increase grain yield, but increased the average grain Zn concentration of 20 wheat genotypes in our current study.

On average, the grain Zn concentrations of 20 wheat genotypes involved in this study were below the Zn biofortification target. Large genotypic difference was observed for grain Zn concentration, with five genotypes, “Line 1280”, “Zhengmai 9405”, “Big grain No.1”, “Taishan 4033”, and “Line 1051” exceeded the Zn biofortification target 40 mg/kg under soil and/or foliar treatments. Selecting genotypes with higher Zn accumulation and optimizing with a proper Zn management are therefore required to reach Zn biofortification of wheat grown under coastal soils.

4. Materials and Methods

4.1. Pot Study Using Soils from Different Locations

In order to examine the effects of soil property on Zn translocation from soil to wheat, top soils (0-20cm) were sampled from 31 different locations of coastal saline region of Yellow river Delta. The sampled soils were then used as the culture substrate in a greenhouse pot study at Shandong University of Aeronautics.

A completely random block design experiment with one factor ‘soil location’ was conducted from Oct. 2020 to Jun. 2021. Wheat (Triticum aestivum L.) cv. LX99, a control variety in North China, was used as the experimental cultivar. 31 different soils were regarded as different levels of factor ‘soil location’. Seed germination was initiated in the dark under room temperature for 3 days, three uniform seedlings were subsequently transplanted into a plastic pot (height, 18.0 cm; diameter, 16.0 cm) filled with 2.0 kg soil. Three pots (replications) were assigned for each soil sample. The light and temperature conditions were set to 16 h light at 25 ± 3 °C and 8 h dark at 18 ± 3 °C, photosynthetic photon flux density set at 120 μmol/m2.s, and relative humidity maintained at 50–60%; the relative water content in the soil was maintained around 70%. The plant growth difference among these 31 different soils was assumed to be caused by difference of soil property. Plants in this pot study were harvested at 8-weeks post transplanting.

4.2. Pot Study Examining the Effects of Zn Application and Salinity

A completely random block pot study with two factors “salinity” and “Zn supply” was applied. A soil sample collected from a farmland (118.02 oE, 37.22 oN) in Bin Cheng district, Bin Zhou, Shan Dong province, China, was used as the culture substrate. The orginal soil had a pH of 7.8, total N of 1.0 g/kg, NaHCO3-extractable phosphorus (Olsen-P) of 31.8 mg/kg, total Zn of 60.8 mg/kg, DTPA-Zn of 3.5 mg/kg. After mixing well, 2.0 kg soil sample was filled into a plastic pot (height, 18.0 cm; diameter, 16.0 cm). Three salinity (NaCl added into soil as 0 g, 1.5 g, and 3.0 g per 1 kg soil) was imposed on corresponding pots by watering the required amount of NaCl solution or distilled water for control pots. Allow the salt-stress imposed pots stay at greenhouse condition for two months. Then, four Zn application levels (ZnSO4 added into soil as 0 mg, 100 mg, 200 mg, and 300 mg per 1 kg soil) were applied by mixing required amount of ZnSO4 with the salt-stress imposed soil. Wheat (Triticum aestivum L.) cv. LX99, was used as the experimental material. Growth condition was controlled the same as described above in section 2.1. Plants in this pot study were harvested at two stages, one at 8-weeks post transplanting and another at maturity.

4.3. Field Trial

Field trials were conducted during the 2020–2021 and 2021–2022 wheat growing seasons in a coastal saline field at the west line of Bohai Gulf within Wudi, Shandong Province, China (37.94 ◦N, 117.83 ◦E). This experimental site experiences semi-drought conditions with pronounced seasonal fluctuations due to its temperate continental monsoon climate. Initial soil characteristics of the three saline field were as following: pH (8.1), EC (6.3 dS m−1), total N (0.9 g kg−1), Olsen-P (8.4 mg kg−1), total Zn (17.8 mg/kg), DTPA-Zn (0.9 mg/kg).

A split-split-plot design was applied. Three soil Zn application levels, 0 kg/ha, 20 kg/ha, and 40 kg/ha were arranged as three main plots by applying ZnSO4 into soil in required amount. Two foliar Zn application levels, no foliar application, and foliar application were set as two sub-plots. Twenty wheat genotypes were regarded as sub-sub-plots, and planted with three replications.

Each main plot received a specific Zn supply level and equal amounts of N (200 kg/ha), P (150 kg/ha) and K (120 kg/ha) fertilizer. For both two growth seasons, foliar Zn application was applied at heading stage by spraying ZnSO4 at a dose of 15 kg/ ha. 250 seeds m−2 were manually sown into each sub-sub-plot (1 m×2 m) in mid-October in both two growth seasons. Mature plants from each plot were harvested at mid Jun each season.

4.4. Measurement of Soil Chemical Indexes

pH and Electric conductivity were measured using soil extraction solution by a pH meter and a conductivity meter (Shanghai Leici Instrument Co. Ltd, China) respectively. Extraction solution was collected by allowing a mixture of air-dried soil and water (g/v, 1:5) homogenised for 5 min, subsequently passing through a vacuum pump at −0.08 MPa (ShaoXing Supo Instrument Co. Ltd, China). Organic matter content was determined using K2Cr2O7 method, the absorbance value was measured at a wavelength of 600 nm using a UV visible spectrophotometer. Concentration of total nitrogen, ammonia-N, and nitrate-N were determined using Kjeldahl method. Soil P concentraiton (total P, Olsen-P) was measured by molybdenum antimony colorimetric method using 0.5 mol/L NaHCO3 extraction solution.

4.5. Measurement of Elemental Concentration of Soil and Plant

Oven-dried plant samples were ground to a fine powder, then a portion of sample (50 mg) digested in a mixture of 15 mL HNO3 and 2 mL H2O2 at 150 °C for 1 h, by using an automatic microwave digester. To determine concentration of soil total Na, K, Ca, Mg, and Zn, soil sample was firstly air-dried at room temperature, then homogenized by grounding to fine powder, subsequently a portion of soil sample (100) mg from each sampling site or treatment was digested in a mixture of 9 mL HNO3, 3 mL HCl, 3 mL HF, and 2 mL H2O2 at 150 °C for 1 h. Concentrations of Na, K, Ca, Mg, Zn in plant and soil were determined by inductively coupled plasma Optical Emission Spectrometer (ICP–OES, Thermo Fisher, USA). Fraction of soil exchangeable K were obtained by extracting air-dried soil with ammonium acetate solution. Fraction of soil DTPA-Zn was extracted using extraction buffer (0.005 mol/L DTPA, 0.01 mol/L CaCl2, 0.1 mol/L TEA, pH 7.3), and subsequently measured by ICP–OES.

4.6. Statistical Analysis

ANOVA was conducted to examine the effect of tested factor using the SPSS 16.0 package (IBM, New York, NY, USA), significance levels (α) were set as 0.05, and 0.01, representing significantly, and very significantly different respectively. Pearson’s correlation analysis and PCA analysis were conducted using the Origin 2018 package to examine relationships among measured variables.

Based on correlation and PCA analysis, the measured soil chemical parameters plant growth parameters, and Zn accumulation parameters, were classfied into six latent variables ‘soil property’, ‘soil nutrients’, ‘soil available nutrients’, ‘plant growth’, ‘soil Zn supply’, PLS-PM model was applied to establish the relationships among these latent variables using R package plspm().

5. Conclusions

Firstly, this study explored the correlations among soil property, Zn availability, and Zn utilization in wheat. Higher soil pH and/or Olsen-P reduced Zn concentration in wheat plant, while higher soil EC value reduced both aboveground biomass and root weight. Zn utilization in wheat grown under coastal soils can be affected directly by soil Zn supply and plant growth, while indirectly affected by soil property, soil nutrients, and soil available nutrients. Secondly, effectiveness of Zn application on grain yield and/or grain Zn concentration in wheat was shown to be dependent on soil natural Zn level, and soil salinity as revealed by pot study and field trial. Grain yield and grain Zn concentration was increased by Zn application under soils with a low salinity, while grain Zn concentration was not increased by Zn application under soils with high salinity. Besides, large genotypic difference was observed among 20 wheat gentoypes under coastal saline soils. Adjusting Zn application tailored to suitable wheat genotypes according to soil property is of promise to reach the Zn biofortification target with a satisfactory yield for wheat grown under coastal saline soils.

Supplementary Materials

Fig S1. Principal component analysis of 16 measured soil chemical parameters. Fig S2. Grain yield of 20 wheat genotypes grown at three soil zinc levels (ZnSO4 added into soil as 0 kg/ha, 20 kg/ha, and 40 kg/ha) under saline field conditions in 2020-2021 (A), and 2021-2022 (B) seasons. Fig S3. Average grain yield of 20 wheat genotypes grown at three soil zinc levels (ZnSO4 added into soil as 0 kg/ha, 20 kg/ha, and 40 kg/ha) and two foliar zinc levels (No foliar application, and foliar application) under saline field conditions in 2020-2021 (A), and 2021-2022 (B) seasons. Fig S4. Grain zinc concentration of 20 wheat genotypes grown at three soil zinc levels (ZnSO4 added into soil as 0 kg/ha, 20 kg/ha, and 40 kg/ha) under saline field conditions in 2020-2021 (A), and 2021-2022 (B) seasons. Table S1. Grain yield and grain zinc concentration of 20 wheat genotypes.

Author Contributions

Conceptualization, D.Z.; methodology, Y.L. and D.Z.; data analysis, J.D., Y.L. and D.Z.; investigation, J.D., Y.L., D.Z.; resources, D.Z.; data curation, Y.L., D.Z.; writing—original draft preparation, D.Z.; writing—review and editing, D.Z.; supervision, D.Z.; project administration, D.Z.; funding acquisition, D.Z. All authors have read and agreed to the published version of the manuscript.

Funding

This research was funded by the National Natural Science Foundation of China (32071954), and PhD initiative Project of Binzhou University (2017Y24).

Data Availability Statement

The original contributions presented in the study are included in the article/supplementary material, further inquiries can be directed to the corresponding author.

Conflicts of Interest

The authors declare no competing interests.

References

- Stangoulis, J.C.R.; Knez, M. Biofortification of major crop plants with iron and zinc - achievements and future directions. Plant Soil 2022, 474, 57–76. [CrossRef]

- Liu, H.; Wang, Z.H.; Li, F.; Li, K.; Yang, N.; Yang, Y.; Huang, D.; Liang, D.; Zhao, H.; Mao, H.; et al. Grain iron and zinc concentrations of wheat and their relationships to yield in major wheat production areas in China. Field Crop. Res. 2014, 156, 151–160. [CrossRef]

- Cakmak, I.; Kutman, U.B. Agronomic biofortification of cereals with zinc: A review. Eur. J. Soil Sci. 2018, 69, 172–180. https://doi: 10.1111/ejss.12437.

- Roy, C.; Kumar, S.; Ranjan, R.D.; Kumhar, S.R.; Govindan, V. Genomic approaches for improving grain zinc and iron content in wheat. Front. Genet. 2022, 13, 1045955. [CrossRef]

- Guo, Z.; Zhang, X.; Wang, L.; Wang, X.; Wang, R.; Hui, X.; Wang, S.; Wang, Z.; Shi, M. Selecting High Zinc Wheat Cultivars Increases Grain Zinc Bioavailability. J. Agric. Food Chem. 2021, 69, 11196–11203. [CrossRef]

- Senguttuvel, P.; G, P.; C, J.; D, S.R.; Cn, N.; V, J.; P, B.; R, G.; J, A.K.; Sv, S.P.; et al. Rice biofortification: breeding and genomic approaches for genetic enhancement of grain zinc and iron contents. Front. Plant Sci. 2023, 14, 1138408. [CrossRef]

- Yang, M.; Li, Y.; Liu, Z.; Tian, J.; Liang, L.; Qiu, Y.; Wang, G.; Du, Q.; Cheng, D.; Cai, H.; et al. A high activity zinc transporter OsZIP9 mediates zinc uptake in rice. Plant J. 2020, 103, 1695–1709. [CrossRef]

- Ning, M.; Liu, S.J.; Deng, F.; Huang, L.; Li, H.; Che, J.; Yamaji, N.; Hu, F.; Lei, G.J. A vacuolar transporter plays important roles in zinc and cadmium accumulation in rice grain. New Phytol. 2023, 239, 1919–1934. [CrossRef]

- Kamran, A.; Ghazanfar, M.; Khan, J.S.; Pervaiz, S.; Siddiqui, M.H.; Alamri, S. Zinc Absorption through Leaves and Subsequent Translocation to the Grains of Bread Wheat after Foliar Spray. Agriculture 2023, 13, 1775. [CrossRef]

- Khalid, S.; Amanullah; Ahmed, I. Enhancing Zinc Biofortification of Wheat through Integration of Zinc, Compost, and Zinc-Solubilizing Bacteria. Agriculture 2022, 12, 968. [CrossRef]

- Alharbi, K.; Hafez, E.M.; Omara, A.E.-D.; Rashwan, E.; Alshaal, T. Zinc oxide nanoparticles and PGPR strengthen salinity tolerance and productivity of wheat irrigated with saline water in sodic-saline soil. Plant Soil 2023, 493, 475–495. [CrossRef]

- Alloway, B.J. Soil factors associated with zinc deficiency in crops and humans. Environ. Geochem. Health 2009, 31, 537–548. [CrossRef]

- Palmer, B.; Guppy, C.; Nachimuthu, G.; Hulugalle, N. Changes in micronutrient concentrations under minimum tillage and cotton-based crop rotations in irrigated Vertisols. Soil Tillage Res. 2023, 228. [CrossRef]

- Mehlich, A. Mehlich No. 3 soil test extractant; A modification of Mehlich No. 2. Commun. Soil Sci. Plant Anal. 1984, 15, 1409-1416.

- Hartemink, A.E.; Barrow, N.J. Soil pH - nutrient relationships: the diagram. Plant Soil 2023, 486, 209–215. [CrossRef]

- Barrow, N.J.; Hartemink, A.E. The effects of pH on nutrient availability depend on both soils and plants. Plant Soil 2023, 487, 21–37. [CrossRef]

- Van, Eynde, E.; Groenenberg, J.E.; Hofand, E.; Comans, R.N.J. Solid-solution partitioning of micronutrients Zn, Cu and B in tropical soils: Mechanistic and empirical models. Geoderma. 2022, 414, 115773.

- Hernandez-Soriano, M.C.; Peña, A.; Mingorance, M.D. SOLUBLE METAL POOL AS AFFECTED BY SOIL ADDITION WITH ORGANIC INPUTS. Environ. Toxicol. Chem. 2013, 32, 1027–1032. [CrossRef]

- Tella, M.; Bravin, M.N.; Thuriès, L.; Cazevieille, P.; Chevassus, Rosset, C.; Collin, B.; Chaurand, P.; Legros, S.; Doelsch, E. Increased zinc and copper availability in organic waste amended soil potentially involving distinct release mechanisms. Environ Pollut. 2016, 212, 299–306.

- Soltani, S.; Khoshgoftarmanesh, A.H.; Afyuni, M.; Shrivani, M.; Schulin, R. The effect of preceding crop on wheat grain zinc concentration and its relationship to total amino acids and dissolved organic carbon in rhizosphere soil solution. Biol. Fertil. Soils 2013, 50, 239–247. [CrossRef]

- Laurent, C.; Bravin, M.N.; Crouzet, O.; Lamy, I. Does a decade of soil organic fertilization promote copper and zinc phytoavailability? Evidence from a laboratory biotest with field-collected soil samples. Sci. Total. Environ. 2023, 906, 167771. [CrossRef]

- Dawar, K.; Ali, W.; Bibi, H.; Mian, I.A.; Ahmad, M.A.; Hussain, M.B.; Ali, M.; Ali, S.; Fahad, S.; Rehman, S.U.; et al. Effect of Different Levels of Zinc and Compost on Yield and Yield Components of Wheat. Agronomy 2022, 12, 1562. [CrossRef]

- Van, Eynde, E.; Fendrich, A.N.; Ballabio, C.; Panagos, P. Spatial assessment of topsoil zinc concentrations in Europe. Science of The Total Environment. 2023, 892, 164512.

- He, H.; Wu, M.; Su, R.; Zhang, K.; Chang, C.; Peng, Q.; Dong, Z.; Pang, J.; Lambers, H. Strong phosphorus (P)-zinc (Zn) interactions in a calcareous soil-alfalfa system suggest that rational P fertilization should be considered for Zn biofortification on Zn-deficient soils and phytoremediation of Zn-contaminated soils. Plant and Soil. 2021, 461, 1-15.

- Watts-Williams, S.J.; Smith, F.A.; McLaughlin, M.J.; Patti, A.F.; Cavagnaro, T.R. How important is the mycorrhizal pathway for plant Zn uptake?. Plant Soil 2015, 390, 157–166. [CrossRef]

- Zhang, W.; Chen, X.-X.; Liu, Y.-M.; Liu, D.-Y.; Chen, X.-P.; Zou, C.-Q. Zinc uptake by roots and accumulation in maize plants as affected by phosphorus application and arbuscular mycorrhizal colonization. Plant Soil 2017, 413, 59–71. [CrossRef]

- Coccina, A.; Cavagnaro, T.R.; Pellegrino, E.; Ercoli, L.; McLaughlin, M.J.; Watts-Williams, S.J. The mycorrhizal pathway of zinc uptake contributes to zinc accumulation in barley and wheat grain. BMC Plant Biol. 2019, 19, 1–14. [CrossRef]

- Ding, J.; Liu, L.; Wang, C.; Shi, L.; Xu, F.; Cai, H. High level of zinc triggers phosphorus starvation by inhibiting root-to-shoot translocation and preferential distribution of phosphorus in rice plants. Environ. Pollut. 2021, 277, 116778. [CrossRef]

- Li, M.; Yang, X.; Tian, X.; Wang, S.; Chen, Y. Effect of Nitrogen Fertilizer and Foliar Zinc Application at Different Growth Stages on Zinc Translocation and Utilization Efficiency in Winter Wheat. Cereal Res. Commun. 2014, 42, 81–90. [CrossRef]

- Liu, D.-Y.; Liu, Y.-M.; Zhang, W.; Chen, X.-P.; Zou, C.-Q. Zinc Uptake, Translocation, and Remobilization in Winter Wheat as Affected by Soil Application of Zn Fertilizer. Front. Plant Sci. 2019, 10, 426. [CrossRef]

- Liu, Y.-M.; Liu, D.-Y.; Zhao, Q.-Y.; Zhang, W.; Chen, X.-X.; Xu, S.-J.; Zou, C.-Q. Zinc fractions in soils and uptake in winter wheat as affected by repeated applications of zinc fertilizer. Soil Tillage Res. 2020, 200. [CrossRef]

- Zhao, D.-Y.; Zhang, Z.-W.; Yuan, Y.-R.; Zhang, X.-L.; Zhao, W.-F.; Li, X.-P.; Wang, J.; Siddique, K.H.M. Accumulation of zinc, iron and selenium in wheat as affected by phosphorus supply in salinised condition. Crop. Pasture Sci. 2022, 73, 537–545. [CrossRef]

- Guo, Z.; Wang, X.; Zhang, X.; Wang, R.; Wang, S.; Chen, Y.; Liu, J.; Tian, H.; Wang, Z.; Shi, M. Rhizosphere microbiome-related changes in soil zinc and phosphorus availability improve grain zinc concentration of wheat. Plant Soil 2023, 490, 651–668. [CrossRef]

- Jiang, Y.; Gao, W.-W.; Zhao, J.-L.; Chen, Q.; Liang, D.; Xu, C.; Huang, L.-S.; Ruan, L.-M. Analysis of influencing factors on soil Zn content using generalized additive model. Sci. Rep. 2018, 8, 15567. [CrossRef]

- Obrador, A.; Alvarez, J.; Lopez-Valdivia, L.; Gonzalez, D.; Novillo, J.; Rico, M. Relationships of soil properties with Mn and Zn distribution in acidic soils and their uptake by a barley crop. Geoderma 2007, 137, 432–443. [CrossRef]

- Li, C.; Guo, Z.; Wang, X.; Ma, Y.; Liu, J.; Shi, M.; Zhang, D.; Malhi, S.S.; Siddique, K.H.; Wang, Z. Field-scale studies quantify limitations for wheat grain zinc biofortification in dryland areas. Eur. J. Agron. 2022, 142. [CrossRef]

- Shen, Y.; Wiita, E.; Nghiem, A.A.; Liu, J.; Haque, E.; Austin, R.N.; Seng, C.Y.; Phan, K.; Zheng, Y.; Bostick, B.C. Zinc localization and speciation in rice grain under variable soil zinc deficiency. Plant Soil 2023, 491, 605–626. [CrossRef]

- Van, Eynde, E.; Breure, M.S.; Chikowo, R.; et al. Soil zinc fertilisation does not increase maize yields in 17 out of 19 sites in Sub-Saharan Africa but improves nutritional maize quality in most sites. Plant Soil. 2023, 490, 67–91.

- Hui, X.; Wang, X.; Luo, L.; Wang, S.; Guo, Z.; Shi, M.; Wang, R.; Lyons, G.; Chen, Y.; Cakmak, I.; et al. Wheat grain zinc concentration as affected by soil nitrogen and phosphorus availability and root mycorrhizal colonization. Eur. J. Agron. 2022, 134. [CrossRef]

- Moreno-Lora, A.; Delgado, A. Factors determining Zn availability and uptake by plants in soils developed under Mediterranean climate. Geoderma 2020, 376. [CrossRef]

- Nable, R.O.; Webb, M.J. Further evidence that zinc is required throughout the root zone for optimal plant growth and development. Plant Soil 1993, 150, 247–253. [CrossRef]

- Recena, R.; García-López, A.M.; Delgado, A. Zinc Uptake by Plants as Affected by Fertilization with Zn Sulfate, Phosphorus Availability, and Soil Properties. Agronomy 2021, 11, 390. [CrossRef]

- Wang, J.; Mao, H.; Zhao, H.; Huang, D.; Wang, Z. Different increases in maize and wheat grain zinc concentrations caused by soil and foliar applications of zinc in Loess Plateau, China. Field Crop. Res. 2012, 135, 89–96. [CrossRef]

|

Disclaimer/Publisher’s Note: The statements, opinions and data contained in all publications are solely those of the individual author(s) and contributor(s) and not of MDPI and/or the editor(s). MDPI and/or the editor(s) disclaim responsibility for any injury to people or property resulting from any ideas, methods, instructions or products referred to in the content. |

© 2025 by the authors. Licensee MDPI, Basel, Switzerland. This article is an open access article distributed under the terms and conditions of the Creative Commons Attribution (CC BY) license (http://creativecommons.org/licenses/by/4.0/).