Submitted:

06 July 2025

Posted:

07 July 2025

You are already at the latest version

Abstract

Keywords:

1. Introduction

2. Materials and Methods

3. Results

3.1. Factorial Analysis

4. Discussion

5. Conclusions

Supplementary Materials

Author Contributions

Funding

Institutional Review Board Statement

Informed Consent Statement

Data Availability Statement

Acknowledgments

Conflicts of Interest

Abbreviations

| AGFI | Adjusted Goodness-of-Fit Index |

| ASD | Autism Spectrum Disorder |

| CFI | Comparative Fit Index |

| EFA | Exploratory Factor Analysis |

| GFI | Goodness-of-Fit Index |

| ICIPES | International COVID-19 Impact on Parental Engagement Study |

| KMO | Kaiser-Meyer-Olkin |

| MIF | Minimum Items Per Factor |

| MSA | Measure Of Sampling Adequacy |

| NNFI | Non-Normalized Fit Index |

| PCIT | Parent-Child Interaction Therapy |

| RMSEA | Root Mean Square Error of Approximation |

| RMSR | Root Mean Square Root of Residuals |

| ULS | Unweighted Least Squares |

| χ2/df | Chi-Square/Degree of Freedom |

Appendix A

| Item (Variable) |

N | Minimum | Maximum | Mean | Std. Deviation | Skewness | Kurtosis | ||

| Statistic | Statistic | Statistic | Statistic | Statistic | Statistic | Std. Error | Statistic | Std. Error | |

| PUTR_1 | 1432 | .00 | 4.00 | 1.2346 | 1.34460 | .837 | .065 | -.527 | .129 |

| PE_1 | 1432 | .00 | 4.00 | 1.7430 | 1.25321 | .268 | .065 | -.927 | .129 |

| PE_2 * | 1432 | .00 | 4.00 | 1.7374 | 1.32156 | .320 | .065 | -1.029 | .129 |

| PUTS_1 | 1432 | .00 | 4.00 | 2.7982 | 1.29199 | -.760 | .065 | -.611 | .129 |

| PUTS_2 | 1432 | .00 | 4.00 | 2.6662 | 1.30324 | -.607 | .065 | -.781 | .129 |

| PUTS_3 * | 1432 | .00 | 4.00 | 2.3624 | 1.29475 | -.239 | .065 | -1.048 | .129 |

| PUTBC_1 | 1432 | .00 | 4.00 | 1.7605 | 1.29905 | .324 | .065 | -.938 | .129 |

| PEIS | 1406 | .00 | 4.00 | 2.0149 | 1.21048 | .032 | .065 | -.889 | .130 |

| PE_3 * | 1432 | .00 | 4.00 | 2.0321 | 1.37323 | .018 | .065 | -1.221 | .129 |

| PE_4 | 1432 | .00 | 4.00 | 1.5126 | 1.33380 | .545 | .065 | -.858 | .129 |

| WHSB_1 * | 1432 | .00 | 4.00 | 1.7123 | 1.41111 | .323 | .065 | -1.189 | .129 |

| WHSB_2 * | 1432 | .00 | 4.00 | 2.5279 | 1.38750 | -.408 | .065 | -1.151 | .129 |

| PE_5 | 1432 | .00 | 4.00 | 1.3645 | 1.17917 | .635 | .065 | -.394 | .129 |

| SHS | 1432 | .00 | 4.00 | 2.9183 | 1.37651 | -.949 | .065 | -.482 | .129 |

| PUTR_2 * | 1432 | .00 | 4.00 | 2.0077 | 1.37282 | -.149 | .065 | -1.240 | .129 |

| PUTBC_2 | 1432 | .00 | 4.00 | 1.3568 | 1.26299 | .529 | .065 | -.823 | .129 |

| PUTBC_3 * | 1432 | .00 | 4.00 | 1.5992 | 1.33436 | .298 | .065 | -1.108 | .129 |

| PUTBC_4 * | 1432 | .00 | 4.00 | 2.0985 | 1.39959 | -.199 | .065 | -1.242 | .129 |

| PUTR_3 * | 1432 | .00 | 4.00 | 1.8443 | 1.33968 | .068 | .065 | -1.164 | .129 |

| PUTBC_5 * | 1432 | .00 | 4.00 | 1.8596 | 1.36462 | .080 | .065 | -1.200 | .129 |

| PUTBC_6 * | 1432 | .00 | 4.00 | 1.9406 | 1.33017 | -.043 | .065 | -1.163 | .129 |

| PUTBC_7 * | 1432 | .00 | 4.00 | 1.8059 | 1.32967 | .075 | .065 | -1.161 | .129 |

| PUTBC_8 * | 1432 | .00 | 4.00 | 1.9309 | 1.34537 | -.022 | .065 | -1.170 | .129 |

| PUTBC_9 * | 1432 | .00 | 4.00 | 1.8855 | 1.32155 | .044 | .065 | -1.099 | .129 |

| PUTBC_10 * | 1432 | .00 | 4.00 | 1.8366 | 1.31427 | .070 | .065 | -1.108 | .129 |

| PUTS_4 | 1432 | .00 | 4.00 | 1.1697 | 1.08279 | .731 | .065 | .044 | .129 |

| Valid N (listwise) |

1406 | ||||||||

References

- Shanti, C. Engaging Parents in Early Head Start Home-Based Programs: How Do Home Visitors Do This? J. Evid.-Based Soc. Work 2017, 14, 311–328. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Korfmacher, J. , Green, B., Staerkel, F. et al. Parent Involvement in Early Childhood Home Visiting. Child Youth Care Forum 2008, 37, 171–196. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Lehtme, R; Toros, K. Parental engagement in child protection assessment practice: Voices from parents. Child. Youth Serv. Rev. 2020, 113, 104968. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Urkmez, B; Gedik, S; Guzen, M. Experiences of Parents of Children with ASD: Implications for Inclusive Parental Engagement J. Child Fam. Stud. 2023, 32, 951–964. [CrossRef]

- Arneson, K.; Peterson, J.; Heideman, J.; Delaney, K.R. When parenting is a longer road than anticipated: a journey examining parents’ experience and engagement at a therapeutic day school. Soc. Work Ment. Health 2020, 18, 587–603. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Yamada, M.; Sekine, M.; Tatsuse, T. Parental Internet Use and Lifestyle Factors as Correlates of Prolonged Screen Time of Children in Japan: Results From the Super Shokuiku School Project. J. Epidemiol. 2018, 28, 407–413. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Salas-Wright, C.P.; AbiNader, M.A.; Vaughn, M.G.; Sanchez, M.; Oh, S.; Goings, T.C. National Trends in Parental Communication With Their Teenage Children About the Dangers of Substance Use, 2002-2016. J. Prim. Prev. 2019, 40, 483–490. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Wahl, M.; Vongsachang, H.; Kretz, A.M.; Callan, J.; Neitzel, A.; Mukherjee, M.R.; Friedman, D.S.; Collins, M.E. Strategies for Success: Parent Perspectives on School-based Vision Programs. Health Behav. Policy Rev. 2022, 9, 683–696. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Paul, P.; Closson, K.; Raj, A. Is parental engagement associated with subsequent delayed marriage and marital choices of adolescent girls? Evidence from the Understanding the Lives of Adolescents and Young Adults (UDAYA) survey in Uttar Pradesh and Bihar, India. SSM-Popul. Health 2023, 24, 101523. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Le Luyer, M.; Boll, M.E.; Lemmers, S.A.M.; Stoll, S.J.; Hoffnagle, A.G.; Smith, A.D.A.C.; Dunn, E.C. How well do parents identify their child’s baby teeth? Engagement and accuracy of parent-reported information on a tooth checklist survey. Community Dentist. Oral Epidemiol. 2024, 52, 731–738. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Barnett, M.L.; Niec, L.N.; Peer, S.O.; Jent, J.F.; Weinstein, A.; Gisbert, P.; Simpson, G. Successful Therapist-Parent Coaching: How In Vivo Feedback Relates to Parent Engagement in Parent-Child Interaction Therapy. J. Clin. Child Adolesc. Psychol. 2017, 46, 895–902. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Yu, X.; Chen, Y.H.; Yang., C.L.; Yang, X.J.; Chen, X.; Dang, X.X. How does parental involvement matter for children’s academic achievement during school closure in primary school? Br. J. Educ. Psychol. 2022, 92, 1621–1637, e12526. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Praphatthanakunwong, N.; Kiatrungrit, K.; Hongsanguansri, S.; Nopmaneejumruslers, K. Factors associated with parent engagement in DIR/Floortime for treatment of children with autism spectrum disorder. Gen. Psychiat. [CrossRef]

- Johnson, S.B.; Arevalo, J.; Cates, C.B.; Weisleder, A.; Dreyer, B.P.; Mendelsohn, A.L. Perceptions About Parental Engagement Among Hispanic Immigrant Mothers of First Graders from Low-Income Backgrounds. Early Child. Educ. J. [CrossRef]

- Markowitz, A.J.; Bassok, D.; Grissom, J.A. Teacher-Child Racial/Ethnic Match and Parental Engagement With Head Start, Am. Educ. Res. J. 2020, 57, 2132–2174, 2831219899356. [CrossRef]

- Antony-Newman, M. Teachers and School Leaders’ Readiness for Parental Engagement: Critical Policy Analysis of Canadian Standards, J. Teach. Educ. 2024, 75, 321–333. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Spear, S.; Spotswood, F.; Goodall, J.; Warren, S. Reimagining parental engagement in special schools - a practice theoretical approach. Educ. Rev. 2022, 74, 1243–1263. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Sakaue, K; Wokadala, J; Ogawa, K. Effect of parental engagement on children’s home-based continued learning during COVID-19-induced school closures: Evidence from Uganda, Int. J. Educ. Dev. 2023, 100, 102812. [CrossRef]

- Carter, R.A.; Rice, M.; Yang, S.H.; Jackson, H.A. Self-regulated learning in online learning environments: Strategies for remote learning. Information and Learning Sciences 2020, 121(5–6), 321–329. [CrossRef]

- Yang, Y.; Liu, K.Q.; Li, M.; Li, S.Q. Students’ affective engagement, parental involvement, and teacher support in emergency remote teaching during the COVID-19 pandemic: Evidence from a cross-sectional survey in China. Journal of Research on Technology in Education 2022, 54(sup1), S148–S164. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Treviño, E.; Miranda, C.; Hernández, M.; Villalobos, C. Socioeconomic status, parental involvement and implications for subjective well-being during the global pandemic of COVID-19. Frontiers in Education 2021, 6, 762780. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Soltero-González, L.; Gillanders, C. Rethinking home-school partnerships: Lessons learned from Latinx parents of young children during the COVID-19 era. Early Childhood Education Journal 2021, 49(5), 965–976. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Moore, S.A.; Faulkner, G.; Rhodes, R.E.; Brussoni, M.; Chulak-Bozzer, T.; Ferguson, L.J.; Mitra, R.; O’Reilly, N.; Spence, J.C.; Vanderloo, L.M.; Tremblay, M.S. Impact of the COVID-19 virus outbreak on movement and play behaviours of Canadian children and youth: A national survey. International Journal of Behavioral Nutrition and Physical Activity 2020, 17, 85. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Marchant, E.; Todd, C.; James, M.; Crick, T.; Dwyer, R.; Brophy, S. Primary school staff perspectives of school closures due to COVID-19, experiences of schools reopening and recommendations for the future: A qualitative survey in Wales. PLOS ONE 2021, 16(12), e0260396. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Tabatadze, S.; Chachkhiani, K. COVID-19 and emergency remote teaching in the country of Georgia: Catalyst for educational change and reforms in Georgia? Educational Studies 2021, 57(1), 78–95. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Harper, F.K.; Rosenberg, J.M.; Comperry, S.; Howell, K.; Womble, S. Mathathome during the COVID-19 pandemic: Exploring and reimagining resources and social supports for parents. Education Sciences 2021, 11(2), 60. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Livingstone, S., & Blum-Ross, A. (2020). Parenting for a digital future: How hopes and fears about technology shape children’s lives. Oxford University Press. [CrossRef]

- Zaman, B., Nouwen, M., Vanattenhoven, J., De Ferrerre, E., & Van Looy, J. A qualitative inquiry into the contextualized parental mediation practices of young children’s digital media use at home. Journal of Broadcasting & Electronic Media 2016, 60(1), 1–22. [CrossRef]

- Osorio-Saez, EM.; Eryilmaz, N.; Sandoval-Hernandez, A., Lau, Y-Y., Barahona, E., Bhatti, AA., Ofoe, GC., Castro Ordóñez, LA., Cortez-Ochoa, AA., Espinoza-Pizarro, RA., Fonseca-Aguilar, E., Isac, MM., Dhanapala, KV., Kameshwara, KK., Martínez-Contreras, YA., Mekonnen, GT., Mejía, JF., Miranda, C., Moh’d, SA., Morales-Ulloa, R., Morgan, K K., Morgan, TL., Mori, S., Nde, FE., Panzavolta, S., Parcerisa, Ll., Paz, CL., Picardo, O., Piñeros, C., Rivera-Vargas, P., Rosa, A., Saldarriaga, LM., Silveira-Aberastury, A., Tang, YM., Taniguchi, K., Treviño, E., Valladares-Celis, C., Villalobos, C., Zhao, D., Zionts, A. Survey data on the impact of COVID-19 on parental engagement across 23 countries, Data in Brief 2021, 106813. [CrossRef]

- Hughes, D.J. Psychometric Validity. In The Wiley Handbook of Psychometric Testing; Irwing, P., Booth, T., Hughes, D.J., Eds.; John Wiley & Sons Ltd.: Hoboken, NJ, USA, 2018; pp. 751–779. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Lloret-Segura, S.; Ferreres-Traver, A.; Hernandez, A.; Tomás, I. Exploratory Item Factor Analysis: A practical guide revised and up-dated. An. Psicol. 2014, 30, 1151–1169. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Ferrando, P.J.; Lorenzo-Seva, U. Program FACTOR at 10: Origins, development and future directions. Psicothema 2017, 29, 236–240. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Lorenzo-Seva, U.; Timmerman, M.E.; Kiers, H.A.L. The Hull Method for Selecting the Number of Common Factors. Multivar. Behav. Res. 2011, 46, 340–364. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Kyriazos, T.A. Applied Psychometrics: Sample Size and Sample Power Considerations in Factor Analysis (EFA, CFA) and SEM in General. Psychology 2018, 09, 2207–2230. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Velicer, W.F.; Fava, J.L. Affects of variable and subject sampling on factor pattern recovery. Psychol. Methods 1998, 3, 231–251. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Lorenzo-Seva, U. & Ferrando, P.J. (2021) The Forgotten Index for Identifying Inappropriate Items Before Computing Exploratory Item Factor Analysis, Methodology 2021, 17, 296–306. 2021, 17, 296–306. [CrossRef]

- Sun, J. (2005). Assessing goodness of fit in confirmatory factor analysis. Measurement and evaluation in counseling and development, 37(4), 240-256.

- Schermelleh-Engel, K. , Moosbrugger, H., and Müller, H. Evaluating the Fit of Structural Equation Models: Tests of Significance and Descriptive Goodness-of-Fit Measures. Methods Psychol. Res., 2003, 8, 23–74. [Google Scholar]

- Kalkan, Ö. K., & Kelecioğlu, H. The effect of sample size on parametric and nonparametric factor analytical methods. Educational Sciences: Theory & Practice, 2016 16(1), 153-171. [CrossRef]

- McHugh, M.L. The chi-square test of independence. Biochem Med (Zagreb) 2013, 23, 143–149. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Muñoz-Pichardo, J.M.; Lozano-Aguilera, E.D.; Pascual-Acosta, A.; Muñoz-Reyes, A.M. Multiple Ordinal Correlation Based on Kendall’s Tau Measure: A Proposal. Mathematics 2021, 9, 1616. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Sensoy, S.; Arıcı, Y. K. Comparison via Simulation of Association Coefficients Calculated between Categorical Variables. Ann. Med. Res. 2023, 30, 1119–1124. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Biblarz, T. J. , & Stacey, J. How does the gender of parents matter? J. Marriage and Family. 2010, 72(1), 3–22. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Raley, R. K., & Sweeney, M. M. Divorce, repartnering, and stepfamilies: A decade in review. J. of Marriage and Family, 2020 82(1), 81–99. [CrossRef]

- Livingstone, S., & Blum-Ross, A. Parenting for a digital future: How hopes and fears about technology shape children’s lives. Oxford University Press 2020. [CrossRef]

- Zaman, B., Nouwen, M., Vanattenhoven, J., De Ferrerre, E., & Van Looy, J. A qualitative inquiry into the contextualized parental mediation practices of young children’s digital media use at home. Journal of Broadcasting & Electronic Media. 2016, 60(1), 1–22. [CrossRef]

- Walsh, F. (2016). Strengthening family resilience (3rd ed.). The Guilford Press.

- Bronfenbrenner, U. (1979). The Ecology of Human Development: Experiments by Nature and Design. Cambridge, MA: Harvard University Press.

- Epstein, J. L. (2011). School, family, and community partnerships: Preparing educators and improving schools (2nd ed.). Routledge. Philadelphia, PA: Westview Press. [CrossRef]

- Muñoz Rodríguez, É. P. Interacción de categorías sociales en la relación familias-escuela ¿cómo favorecen u obstaculizan la participación? Revista Latinoamericana de Estudios Educativos. 2022, 52(3), 337–370. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Desimone, L. Linking Parent Involvement with Student Achievement: Do Race and Income Matter? The Journal of Educational Research. 1999, 93(1), 11–30. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Green, L., Holloway, D., Stevenson, K., Leaver, T., & Haddon, L. (Eds.). (2020). The Routledge companion to digital media and children (1st ed.). Routledge. [CrossRef]

- Pomerantz, E.M., Moorman, E. A., & Litwack, S. D. The How, Whom, and Why of Parents’ Involvement in Children’s Academic Lives: More Is Not Always Better. Review of Educational Research. 2007, 77(3), 373-410. [CrossRef]

- Eccles, J. S., Midgley, C., Wigfield, A., Buchanan, C. M., Reuman, D., Flanagan, C., & Mac Iver, D. Development during adolescence: The impact of stage-environment fit on young adolescents’ experiences in schools and in families. American Psychologist, 1993, 48(2), 90–101. [CrossRef]

- Hoover-Dempsey, K.V. , & Sandler, H. M. Why Do Parents Become Involved in Their Children’s Education? Review of Educational Research. 1997, 67(1), 3–42. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Hill, N. E., & Tyson, D. F. Parental involvement in middle school: A meta-analytic assessment of the strategies that promote achievement. Developmental Psychology. 2009, 45(3), 740–763. [CrossRef]

- Sánchez-Díaz, C.; Muñoz, A.; Osorio, J. Diversidad familiar y trayectorias educativas: Un análisis desde la perspectiva de la equidad en Chile. Rev. Latinoam. Educ. Inclusiva 2018, 12, 155–172. [Google Scholar]

- Veloza-Morales, M.C.; Forero Beltrán, E.; Rodríguez-González, J.C. Significados de familia para familias contemporáneas. Rev. Latinoam. Cienc. Soc. Niñez Juventud 2023, 21, 180–198. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Hoover-Dempsey, K.V.; Sandler, H.M. Final Performance Report for OERI Grant #R305T010673: The Social Context of Parental Involvement: A Path to Enhanced Achievement; U.S. Department of Education: Washington, DC, USA, 2005.

- Knoche, L.L.; Edwards, C.P.; Sheridan, S.M.; Kupzyk, K.A.; Marvin, C.A.; Cline, K.D.; Clarke, B.L. Getting Ready: Results of a randomized trial of a relationship-focused intervention on parent engagement in rural Early Head Start. Infant Ment. Health J. 2012, 33, 439–458. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Stapley, E.; Vainieri, I.; Li, E.; Merrick, H.; Jeffery, M.; Foreman, S.; Casey, P.; Ullman, R.; Cortina, M. A scoping review of the factors that influence families’ ability or capacity to provide young people with emotional support over the transition to adulthood. Front. Psychol. 2021, 12, 732899. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

| Article | Sample | Method | MIF | χ2/df | RMSEA | AGFI | GFI | CFI | NNFI | RMSR |

| Schermelleh-Engel et al. [4] | ≥ 200 | Good fit | NR | ≥ 0 ≤ 2 | ≤ .05 | ≥ .90 ≤ 1.00 | ≥ .95 ≤ 1.00 | ≥ .97 ≤ 1.00 | ≥ .97 ≤ 1.00 | < .05+ |

| Acceptable fit | ≥ 3 | > 2 ≤ 3 | > .05 ≤ .08 | ≥ .85 < .90 | ≥ .90 < .95 | ≥ .95 < .97 | ≥ .95 < .97 | ≥ .05 ≤ .08++ |

| Name (ID) | Categories | Value | N |

| Parent/carer gender (PGEN) N = 1432 |

Mother, Stepmother, Grandmother, adoptive/foster mother or female guardian | 0 | 1171 |

| Father, Stepfather, Grandfather, adoptive/foster father or male guardian | 1 | 261 | |

| Parent/carer years of schooling (PYS) N = 1432 |

8 | 12 | |

| 9 | 0 | ||

| 10 | 55 | ||

| 11 | 0 | ||

| 12 | 29 | ||

| 13 | 104 | ||

| 14 | 33 | ||

| 15 | 689 | ||

| 16 | 0 | ||

| 17 | 428 | ||

| 18 | 0 | ||

| 19 | 81 | ||

| 20 | 0 | ||

| 21 | 1 | ||

| Parent/carer Age (PAG) N = 1432 |

25-34 years old | 2 | 191 |

| 35-44 years old | 3 | 674 | |

| 45-54 years old | 4 | 469 | |

| 55-64 years old | 5 | 98 | |

| Family structure/composition (FAMC) N = 1283 |

Living with the father/mother of the child | 0 | 913 |

| Living with a partner who is not the father/mother of the child | 1 | 113 | |

| Raising a child without a partner | 2 | 257 | |

| Child’s age (CHAG) N = 1432 |

6-year-old | 0 | 204 |

| 7-year-old | 1 | 129 | |

| 8-year-old | 2 | 149 | |

| 9-year-old | 3 | 114 | |

| 10-year-old | 4 | 128 | |

| 11-year-old | 5 | 116 | |

| 12-year-old | 6 | 137 | |

| 13-year-old | 7 | 96 | |

| 14-year-old | 8 | 96 | |

| 15-year-old | 9 | 84 | |

| 16-year-old | 10 | 179 | |

| Children in the household (CHH) (Number of siblings) N = 1432 |

0 | 453 | |

| 1 | 609 | ||

| 2 | 275 | ||

| 3 | 67 | ||

| 4 | 20 | ||

| 5 | 5 | ||

| 6 | 2 | ||

| 7 | 1 | ||

| School Home communication: Learning Plan (SHC_LP) N = 1432 |

Yes | 0 | 1335 |

| No | 1 | 97 | |

| School Home communication (SHC_FLP) N = 1335 |

Everyday | 0 | 640 |

| Between two to three times per week | 1 | 207 | |

| Once per week | 2 | 350 | |

| Fortnight / every two weeks | 3 | 103 | |

| Once per month | 4 | 35 | |

| Parental engagement: homeschooling (PEHS) N = 1432 |

Yes | 0 | 1115 |

| No | 1 | 317 | |

| Parental engagement: time (PETT) N = 1115 |

Less than 10 hours per week | 0 | 793 |

| Between 11 and 20 hours per week | 1 | 279 | |

| Between 21 and 30 hours per week | 2 | 35 | |

| More than 31 hours per week | 3 | 8 |

| Item ID | Questions | Factor |

Factor Name |

|

| 1 | 2 | |||

| PUTS_1 | Follow on social media what other parents do and try to do exactly the same. | .885 | F1: Social Learning for Parenting |

|

| PUTS_2 | Follow on social media what other parents do and use it as an inspiration. | .845 | ||

| PUTBC_1 | Look for ideas on the internet using different websites. | .487 | ||

| PE_1 | Follow my ideas about what my children need to learn. | .474 | ||

| SHS | I ask my older child(ren) to be in charge of homeschooling the little one(s). | .450 | ||

| PEIS | I try to replicate the way I was taught when I was at school. | .441 | ||

| PE_4 | My children and I have a set homeschooling timetable. | .578 | F2: Parenting in Homeschooling |

|

| PUTR_1 | Check the school’s emails, blog, and website to follow the activities they suggest for the children. | .549 | ||

| PE_5 | I develop with my children spontaneous learning activities not necessarily school-related such as cooking, woodwork, online games, physical activities, etc. | .445 | ||

| Rotation Sums of Squared Loadings a |

2.539 | 1.295 | ||

| Factor Correlation |

Factor 1 | 1.000 | .129 | |

| Factor 2 | .129 | 1.000 | ||

| Item ID | Factor | Factor | Factor | ||

| 1 | 2 | ||||

| PUTS_1 | .989 (0.956; 1.015) a | F1: Social Learning for Parenting |

|||

| PUTS_2 | .909 (0.876; 0.939) | ||||

| SHS | .473 (0.409; 0.529) | ||||

| PUTBC_1 | .444 (0.398; 0.485) | ||||

| PE_1 | .439 (0.396; 0.490) | ||||

| PE_4 | .720 (0.660; 0.777) | F2: Parenting in Homeschooling |

|||

| PUTR_1 | .649 (0.582; 0.725) | ||||

| PE_5 | .538 (0.481; 0.595) | ||||

| Eigenvalues of the Reduced Correlation Matrix |

2.972 | 1.137 | Sum: 4.109 | ||

| Weighted Eigenvalues | 0.723 | 0.277 | |||

| Factor Correlation | 1.000 | .344 (0.290; 0.397) | Factor 1 | ||

| .344 (0.290; 0.397) | 1.000 | Factor 2 | |||

| Article | Sample | Fit | MIF | χ2/df | RMSEA | AGFI | GFI | CFI | NNFI | RMSR |

| Schermelleh-Engel et al. [38] | ≥ 200 | Good | NR | ≥ 0 ≤ 2 | ≤ .05 | ≥ .90 ≤ 1.00 | ≥ .95 ≤ 1.00 | ≥ .97 ≤ 1.00 | ≥ .97 ≤ 1.00 | < .05+ |

| Acceptable | ≥ 3 | > 2 ≤ 3 | > .05 ≤ .08 | ≥ .85 < .90 | ≥ .90 < .95 | ≥ .95 < .97 | ≥ .95 < .97 | ≥ .05 ≤ .08++ | ||

| Osorio-Saez et al [29] by Chile | 1597 | NR | NR | .153 | NR | NR | .869 | NR | NR | |

| Proposed Model | 1406 | 3 | 3.611 | .054* (.030; .061) |

.989** (.986; .995) | .994** (.993; .998) | .986** (.982; .996) | .973** (.966; .992) | .037** (.024; .041) |

| Name (ID) | F1 | F2 | FT | ||||||||||

| Val. |

Asym. Std. Error |

Approx. T |

Approx. Sig. | Val. |

Asym. Std. Error |

Approx. T |

Approx. Sig. |

Val. |

Asym. Std. Error |

Approx. T |

Approx. Sig. | ||

| Parent/carer gender (PGEN) N = 1432 |

Kendall’s tau-c | .031 | .023 | 1.382 | .167 | .022 | .023 | .962 | .336 | .033 | .022 | 1.492 | .136 |

| Gamma | .075 | .054 | 1.382 | .167 | .052 | .054 | .962 | .336 | .085 | .057 | 1.492 | .136 | |

| Parent/carer years of schooling (PYS) N = 1432 |

Kendall’s tau-c | -.006 | .019 | -.338 | .736 | .011 | .019 | .591 | .554 | -.010 | .019 | -.544 | .587 |

| Gamma | -.011 | .033 | -.338 | .736 | .019 | .032 | .591 | .554 | -.019 | .034 | -.544 | .587 | |

| Parent/carer Age (PAG) N = 1432 |

Kendall’s tau-c | .038 | .021 | 1.863 | .062 | .014 | .020 | .676 | .499 | .025 | .020 | 1.246 | .213 |

| Gamma | .063 | .034 | 1.863 | .062 | .022 | .033 | .676 | .499 | .045 | .036 | 1.246 | .213 | |

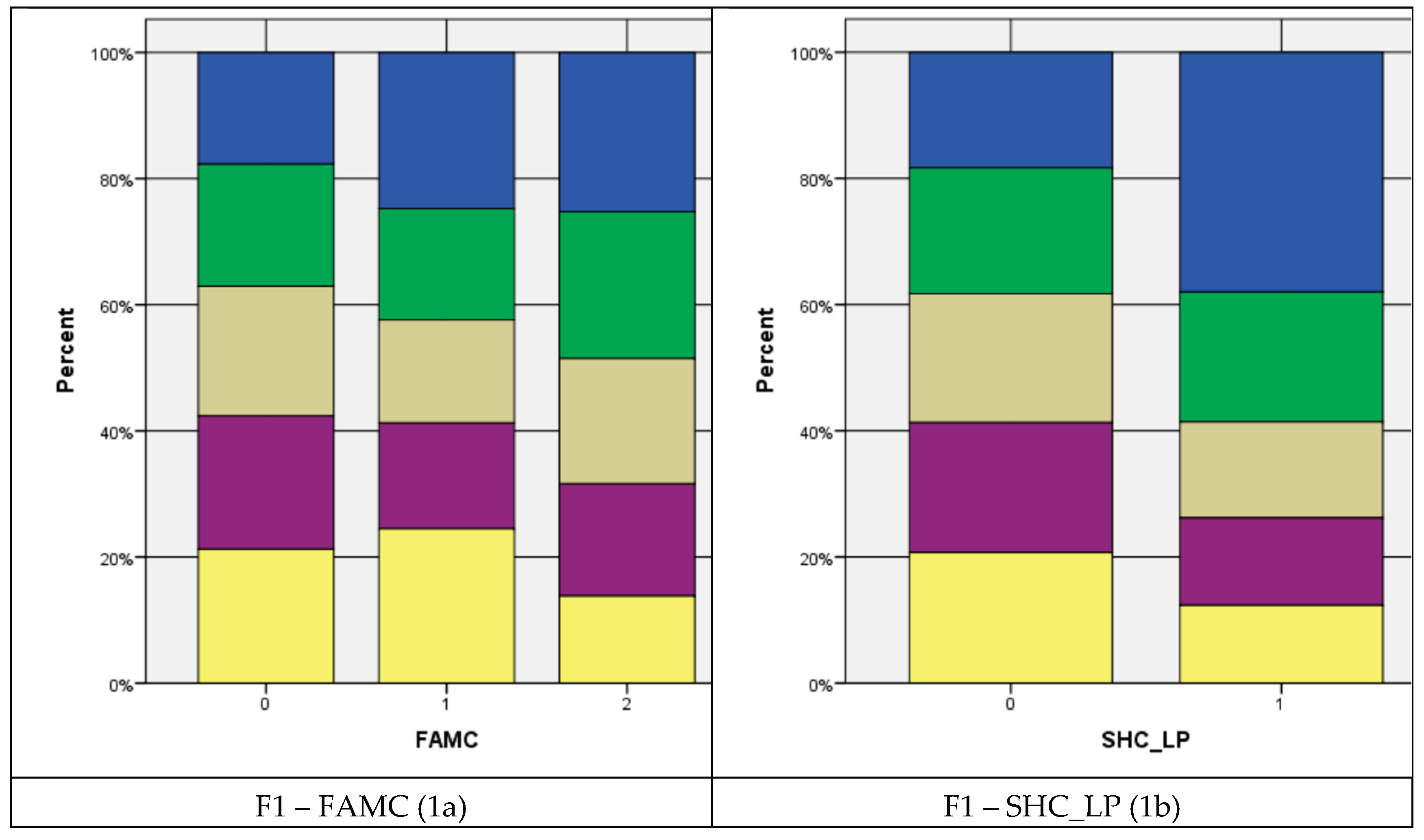

| Family structure/composition (FAMC) N = 1283 |

Kendall’s tau-c | -.045 | .021 | -2.117 | .034* | -.016 | .021 | -.755 | .450 | -.029 | .020 | -1.450 | .147 |

| Gamma | -.094 | .044 | -2.117 | .034* | -.033 | .044 | -.755 | .450 | -.068 | .046 | -1.450 | .147 | |

| Child’s age (CHAG) N = 1432 |

Kendall’s tau-c | .034 | .021 | 1.622 | .105 | .008 | .022 | .367 | .714 | .025 | .020 | 1.233 | .218 |

| Gamma | .042 | .026 | 1.622 | .105 | .010 | .027 | .367 | .714 | .034 | .028 | 1.233 | .218 | |

| Children in the household (CHH) (Number of siblings) N = 1432 |

Kendall’s tau-c | .015 | .020 | .764 | .445 | -.006 | .020 | -,314 | .753 | -.005 | .019 | -.255 | .799 |

| Gamma | .025 | .033 | .764 | .445 | -.010 | .032 | -.314 | .753 | -.009 | .034 | -.255 | .799 | |

| School Home communication: Learning Plan (SHC_LP) N = 1432 |

Kendall’s tau-c | -.032 | .015 | -2.084 | .037* | .005 | .016 | .327 | .744 | -.016 | .016 | -1.036 | .300 |

| Gamma | -.177 | .082 | -2.084 | .037* | .028 | .084 | .327 | .744 | -.095 | .090 | 1.036 | .300 | |

| School Home communication (SHC_FLP) N = 1335 |

Kendall’s tau-c | .012 | .020 | .614 | .539 | -.018 | .020 | -.882 | .378 | .009 | .020 | .447 | .655 |

| Gamma | .021 | .034 | .614 | .539 | -.030 | .034 | -.882 | .378 | .017 | .037 | .447 | .655 | |

| Parental engagement: homeschooling (PEHS) N = 1432 |

Kendall’s tau-c | -.005 | .025 | -.191 | .849 | -.014 | .025 | -.544 | .586 | .001 | .024 | .039 | .969 |

| Gamma | -.010 | .050 | -.191 | .849 | -.027 | .050 | -.544 | .586 | .002 | .053 | .039 | .969 | |

| Parental engagement: time (PETT) N = 1115 |

Kendall’s tau-c | -.018 | .020 | -.887 | .375 | -.033 | .020 | -1.624 | .104 | -.031 | .019 | -1.581 | .114 |

| Gamma | -.044 | .050 | -.887 | .375 | -.081 | .050 | -1.624 | .104 | -.083 | .052 | -1.581 | .114 | |

| Name (ID) | F1 | F2 | FT | |||

| Value |

Asymptotic Significance (2 - sided) |

Value |

Asymptotic Significance (2 - sided) |

Value |

Asymptotic Significance (2 - sided) |

|

| Parent/carer gender (PGEN) N = 1432 | 2.672 | .614 | 8.304 | .081 | 5.545 | .236 |

| Parent/carer years of schooling (PYS) N = 1432 | 23.346 | .867 | 21.851 | .911 | 27.375 | .700 |

| Parent/carer Age (PAG) N = 1432 | 14.795 | .253 | 6.050 | .914 | 7.907 | .792 |

| Family structure/composition (FAMC) N = 1283 | 9.230 | .323 | 6.818 | .556 | 12.660 | .124 |

| Child’s age (CHAG) N = 1432 | 70.192 | .002** | 85.920 | .000** | 95.144 | .000** |

| Children in the household (CHH) (Number of siblings) N = 1432 | 27.141 | .511 | 21.278 | .814 | 30.729 | .329 |

| School Home communication: Learning Plan (SHC_LP) N = 1432 | 10.208 | .037* | 7.045 | .134 | 12.447 | .014* |

| School Home communication (SHC_FLP) N = 1335 | 20.963 | .180 | 13.756 | .617 | 21.616 | .156 |

| Parental engagement: homeschooling (PEHS) N = 1432 | 5.032 | .284 | 4.560 | .336 | 2.631 | .621 |

| Parental engagement: time (PETT) N = 1115 | 19.649 | .074 | 21.912 | .039* | 21.972 | .038* |

Disclaimer/Publisher’s Note: The statements, opinions and data contained in all publications are solely those of the individual author(s) and contributor(s) and not of MDPI and/or the editor(s). MDPI and/or the editor(s) disclaim responsibility for any injury to people or property resulting from any ideas, methods, instructions or products referred to in the content. |

© 2025 by the authors. Licensee MDPI, Basel, Switzerland. This article is an open access article distributed under the terms and conditions of the Creative Commons Attribution (CC BY) license (http://creativecommons.org/licenses/by/4.0/).