Introduction

There are approximately 240 million children with disabilities worldwide, with more than half residing in sub-Saharan Africa and South Asia [

1,

2]. These children face significant challenges in accessing education, social services, and healthcare, often leading to economic marginalisation and poor living conditions [

3,

4]. In the education sector, children with disabilities require additional support and resources [

5]. However, they are significantly less likely to attend school and are more prone to dropping out than their peers without disabilities [

6,

7,

8]. These educational exclusions have long-term negative effects, including limited economic opportunities and persistent poverty [

9].

Parental involvement is critical for improving the educational outcomes of children with disabilities. However, the level of involvement is significantly different for parents of children with disabilities, especially those from rural and poor communities, as they are more prone to constrained financial resources and truncated social networks [

10]. In this paper, we refer to ‘parents’ more broadly to individuals with parental responsibility and other carers or guardians of children or young people, including relatives or adults residing in the same home [

11]. Several studies have emphasised the importance of stronger relationships between professionals and parents, advocating for a family-centric approach to delivering educational services [

12,

13]. Parental involvement encompasses various forms, including parenting at home, communicating with schools, volunteering, learning at home, participating in school decision-making, and collaborating with the community [

14,

15,

16,

17]. Despite this, parents of children with disabilities face numerous challenges, including financial constraints, negative societal attitudes, and inadequate community and policy support, particularly in low-income settings [

18,

19].

Parental beliefs and caregiving methods vary significantly across cultural contexts [

20]. Therefore, expanding the research focus on parental involvement in diverse settings and contexts is crucial to deepen our understanding of this critical aspect of education. Unfortunately, most studies on parental involvement have concentrated on high-income settings [

21], resulting in a lack of understanding of the unique challenges and needs of parents in low-income settings [

22]. However, there is a noticeable gap in research that explicitly focuses on the education of children with disabilities in LMICs (low-and-middle-income countries) such as Malawi, which is the focus of this study [

23,

24,

25].

Estimates of the prevalence of disabilities among school-aged children in Malawi range from 0.43% to 5.60% [

26]. Parents of children with disabilities in Malawi, a low-income country in sub-Saharan Africa, face many challenges in providing adequate support for children with disabilities, particularly in rural areas, where 84% of the population lives [

27]. Although the Malawian government has emphasised inclusive education, significant barriers remain, including a lack of parental involvement in the education of children with disabilities [

28,

29]. Additionally, a growing body of literature examines the significance of parental involvement [

30,

31] and issues surrounding the education of children with disabilities in Malawi [

28,

32,

33,

34,

35,

36,

37], specifically focusing on parental involvement in the education of children with disabilities in Malawi.

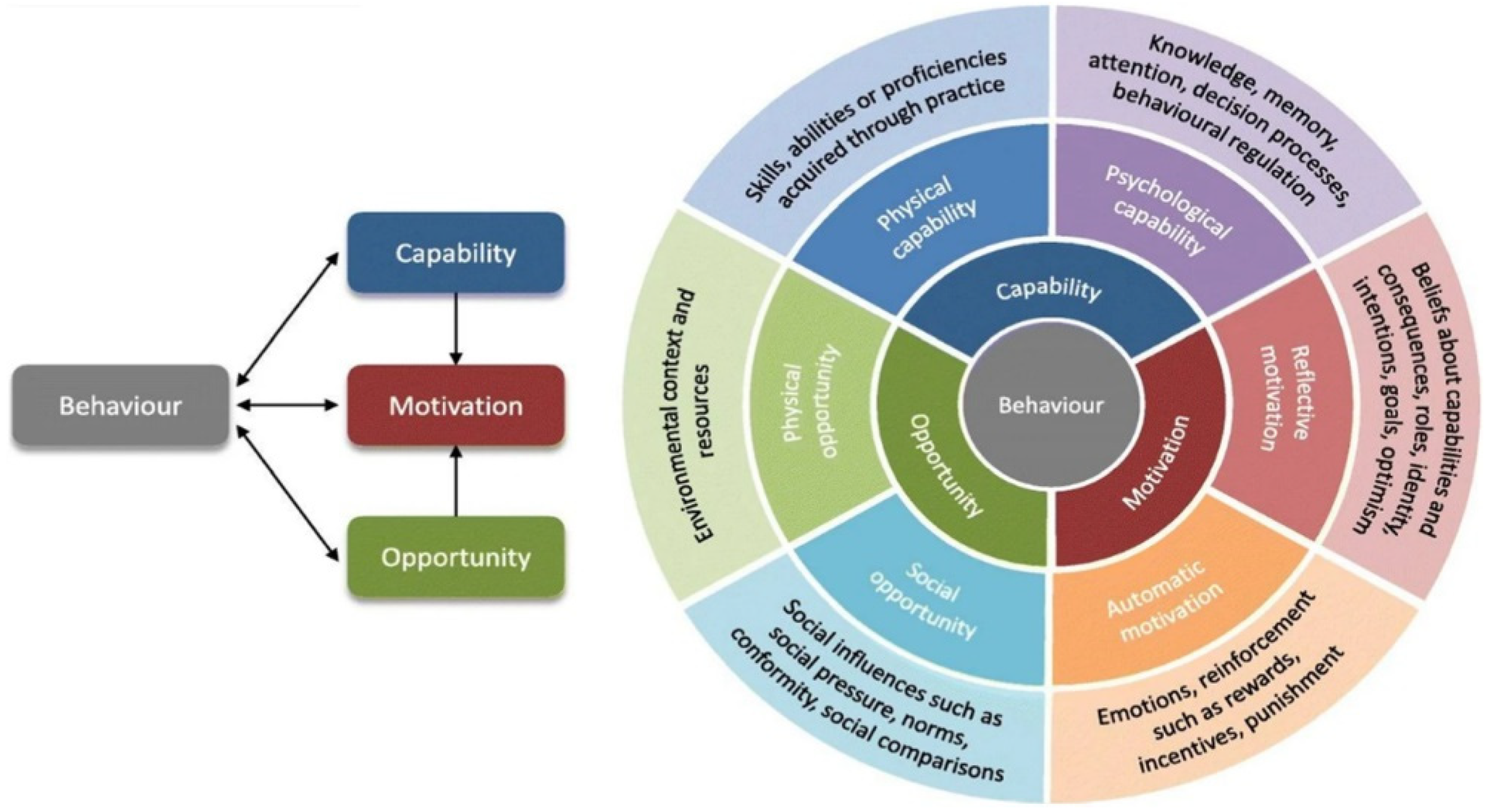

This study utilised the Capability-Opportunity-Motivation-Behaviour (COM-B) model [

38] to explore factors influencing parental involvement. This model is a comprehensive framework at the Behaviour Change Wheel (BCW) hub designed to understand behaviours and identify intervention targets. According to the COM-B model, individuals must have the physical and psychological capability, social and physical opportunities, and motivation to engage in a specific behaviour over other options or competing behaviours [

39]. These three components interact with each other, with Capability and Opportunity influencing Motivation (see

Figure 1).

The COM-B model is helpful because it integrates the psychological, social, and environmental dimensions, making it versatile for exploring behaviour in different contexts [

40,

41,

42]. Recent applications of the COM-B model in sub-Saharan Africa, such as in South Africa and Cameroon, to promote healthy lifestyles and in Uganda to prevent drowning demonstrate its effectiveness in diverse contexts. For instance, in South Africa and Cameroon, children and adolescents support healthy eating and active living among children and adolescents [

43]. In Uganda, Oporia et al. (2023) developed and validated an intervention package using the COM-B model to enhance lifejacket wear for drowning prevention among occupational boaters [

41].

This study presents a novel approach by applying the COM-B model to investigate parental involvement in educating children with disabilities, offering a distinctive perspective on factors influencing parental engagement in a low-income setting like Malawi. It also fills a critical gap by focusing on low-income settings, particularly Malawi. It emphasises the need for an in-depth exploration of the key facilitating factors and barriers faced by parents as critical steps in enabling the development of targeted interventions and support mechanisms to improve educational opportunities for children with disabilities.

This study aimed to explore the factors influencing parental involvement and support in educating children with disabilities in Malawi, bridging a critical gap in the literature on this subject in low-income settings. The study objectives included assessing parents’ ability to support children’s education, exploring parental involvement opportunities, and understanding the motivational factors influencing parental engagement in educating children with disabilities. The research questions that guided the study in Malawi were as follows: What are the capabilities of parents to support the education of their children with disabilities?; What opportunities exist for parental involvement in the education of children with disabilities?; and How do motivational factors influence parental involvement in the education of children with disabilities?

2. Materials and Methods

2.1. Study Design

We employed a qualitative research design to gain in-depth insight into the experiences and perceptions of parents, teachers, and children with disabilities in Malawi. This approach was chosen because of its ability to capture participants’ rich, contextualised experiences and perceptions, which are crucial for understanding the complex social and cultural dynamics [

42]. We considered qualitative methods, including focus groups and in-depth interviews, as they aligned well with the objectives of our study within this specific sociocultural setting [46]. Grounded in the COM-B model [

38], this design provided the necessary flexibility to explore how capability, opportunity, and motivation interact to shape parental behaviour in a rural and low-income setting, such as in Malawi.

2.2. Researcher Characteristics and Reflexivity

The lead author of this paper (DM), a PhD student at the LSHTM in the UK with a background in Zimbabwe, brings valuable sociocultural insights that resonate with Malawi, enhancing the study’s relevance and depth. However, as an ‘outsider’, he also worked alongside a Malawian collaborator (TM) and three research assistants (two female and one male). The collaboration aimed to reduce bias by incorporating diverse perspectives and ensure cultural relevance by leveraging the team’s varied academic and civil society backgrounds, enhancing the research’s credibility and validity. Local involvement addressed power imbalances and enriched data interpretation by providing nuanced insights and cultural sensitivity, thereby strengthening the study’s methodology and outcomes.

2.3. Setting

We conducted this study at two rural primary schools in Nkhata Bay, a district in Malawi. The district economy relies heavily on agriculture, fishing, forestry, local commerce, and tourism, with about 18% of the population classified as ‘ultra-poor’ [47]. According to the National Statistics Office of Malawi (2019), approximately 5,400 children aged five years or older with disabilities live in this district [

27]. Two schools were selected because of their eligibility to participate in a new inclusive education project serving families and children with disabilities delivered by the Church of the Central Africa Presbyterian (CCAP) Education Department.

2.4. Participants and Recruitment

The study included children with disabilities aged 10-18 years, their parents or caregivers, and schoolteachers. Staff from the local Inclusive Education Project, in collaboration with the Ministry of Education and a local program for persons with disabilities in the Nkhata Bay District, recommended gathering participants from two local primary schools. We contacted the principals of the two primary schools and agreed to participate in this study. Eligible participants were required to fulfil diverse roles (e.g., parents, teachers, or children), represent a range of disabilities (e.g., visual, hearing, and physical disabilities), or maintain a gender balance. To mitigate selection bias, we targeted various characteristics to include participants from multiple socio-economic backgrounds and with varying levels of prior engagement with schools. Only parents of school-aged children with disabilities enrolled in the participating schools at the time of the study were eligible to participate. We also considered teachers eligible if they had children with disabilities in their classes. The school principals worked with their senior teachers and school committee members to identify parents who met the criteria, and they provided the research team with a list of eligible names. The research team made personal invitations to the 25 people listed, and all agreed to participate. Six children with disabilities (3f, 3m), 11 parents (7f, 4m), and nine teachers (5f, 4m) all agreed to participate in the study. Children were considered eligible if they faced significant difficulty or limitations performing daily activities, as assessed by the Washington Group Short Set on Functioning (WG-SS) [48]. Among the parents, nine were biological parents of children with disabilities (6f, 3m), and the remaining two were non-biological caregivers, specifically, an aunt and an uncle.

Table 1 provides a detailed overview of the participants’ characteristics in the study.

2.5. Data Collection

The lead author collaborated with a team of three research assistants from Malawi to collect data for this study (2f, 1m). We developed semi-structured interview guides based on literature review and consultations with experts in disability, education, and qualitative research. We translated these guides into Chichewa and back-translated them to ensure cultural appropriateness and accuracy. Following consultations with local experts, we customised the interview guides to align with the local context. LSHTM and University of Livingstonia professionals reviewed and approved the final data collection tools and interview guides. We collected data through focus groups and interviews between May and September 2019. In addition to the three focus groups, we conducted 15 in-depth interviews in Chichewa with parents and children—and in English with teachers. The discussions and interviews, which lasted 45-60 minutes each, allowed participants to share their perspectives on parental involvement in the education of children with disabilities. We obtained written informed consent from participants aged 18 years and above and assent, along with consent from guardians or parents of participants under 18, following the ethical guidelines for research involving minors. We first informed the participants about the study objectives, potential benefits and risks, confidentiality, and voluntary participation to avoid potential power dynamics between the researchers and participants. We took special precautions to minimise potential distress or harm to children with disabilities, a vulnerable population. Local researchers were involved in data collection to moderate perceived power imbalances. We maintained participant confidentiality, anonymised all data during transcription, and securely stored it, making it accessible only to the research team and in compliance with data protection regulations

2.6. Data Analysis and Management

We transcribed the audio recordings and translated the Chichewa versions into English for analysis. The lead author first familiarised himself with the data, developed the initial codes, and then discussed them with a local collaborator in Malawi to refine them and create a comprehensive codebook. The codes were systematically grouped under Capability (e.g., knowledge, understanding, and time availability), Opportunity (e.g., external support, teacher-parent relationships, and peer-to-peer support), and Motivation (e.g., beliefs about benefits, priority setting, and optimism about the child’s future). DM, BM and CK systematically applied the codebook to all the transcripts using ATLAS.ti software version 9 0, resolving any variances by discussion. After coding the data, we identified sub-themes within each component of the COM-B model, such as ‘knowledge and understanding’ or ‘beliefs in the benefits of education.’ These themes highlight vital factors that influence parental involvement. Finally, the team interpreted and synthesised the themes, taking into account the study objectives and existing literature to provide a comprehensive understanding of parental involvement in Malawi. In March 2023, we shared emerging themes and interpretations with 23 participants, including initial study participants, education officials, civil society representatives, and individuals with disabilities, in a multi-stakeholder workshop. This step ensured that the findings represented the participants’ viewpoints and experiences, thus enhancing their validity [46,47].

3. Results

Table 2 presents the key factors influencing parental involvement in Malawi. The study identified the following sub-themes related to COM-B components: Capability, Opportunity and Motivation.

3.1. Capability

This section presents the facilitators of and barriers to parental involvement related to the capability component of the COM-B model. It highlights the main facilitators of involvement, such as parental knowledge, understanding, and commitment to supporting their children’s education, as well as the main challenges, such as the competing demands for primary responsibilities and financial constraints.

3.1.1. Knowledge and understanding

Parents who understood the importance of education were better equipped to support their children with disabilities. For example, parents who understood their responsibilities actively ensured their children attended school and received the support they needed. One teacher noted, “Parents understand their responsibility to ensure their children attend school and receive the supplies they need.” (Teacher #02, female). Similarly, some children felt that parents who had a deeper understanding of their roles supported their children’s learning more actively. For instance, one child stated, “My parents are aware of their responsibility to send me to school. They encourage me to read.” (Child #02, male). However, parents with limited literacy skills find it challenging to actively participate in their children’s education due to a lack of understanding of their disabilities and educational entitlements. As one teacher highlighted, “They [parents] may not know how to care for the child or what the child can have. This may be due to their educational background. Most parents need better education on these issues to understand their children’s needs.” (Teacher #02, female). Furthermore, some parents held negative views towards disability, perceiving it as a “punishment from God.” Such stereotypes stem from sociocultural pressures that discourage parents from actively helping with their children’s education.

3.1.2. Physical capability

Many parents face challenges in supporting their children’s education because of the demands of their primary responsibilities, such as farming. They struggle to make time for school-related activities, such as teacher consultations. Participants expressed that this was especially true in rural settings, where subsistence farming is the primary occupation for most of the families. One female parent mentioned, “Since many parents depend on farming, most of their time is spent on farms, and they pay little attention to the education of their children with disabilities’ (Parents’ FGD (Focus Group Discussion), female Kalambwe). Despite these challenges, some parents were deeply committed to supporting their children’s education, ensuring that their children could attend school, and that they would provide for their material needs, such as a wheelchair. One parent stated, “It is my role to escort my child to school and ensure that their wheelchair is always in good condition” (Parent #08, female, FGD). Although this statement reflects a keen sense of responsibility, it also suggests that parental involvement is often limited to physical caregiving.

3.1.3. Financial demands and priorities

Another barrier to parental involvement is the need for parents to prioritise their immediate needs over their children’s education. Most participants agreed that households from poorer backgrounds often found that, due to financial constraints, it was more important to focus on their immediate subsistence activities over educational involvement. For example, a male parent stated, “Parents play a leading role in assisting and supporting their children, but due to limited resources, they often struggle to provide adequate support for their children with disabilities” (Parent #04, male).

3.2. Opportunity

In this section, we highlight the results on the positive influence of school openness, parent-to-parent interactions, and external support from the community on parental involvement. However, we also identified challenges, such as a lack of structured interactions and widespread community-based interventions that hinder parental engagement.

3.2.1. School openness and teacher attitudes

The study found that proactive engagement by school administrators and teachers positively influences parental involvement. Schools that actively engaged with their parents and maintained open communication channels had higher levels of parental involvement. A female parent praised the school’s efforts. Additionally, committees, such as school management or parent associations, bridge the gap between schools and homes, fostering a collaborative environment. A female parent praised the school’s efforts, stating, “Our school has organised committees, such as school management, parent associations, and mother groups, to oversee the welfare of children with disabilities” (Parent #09, female, focus group). However, some parents felt disconnected from their children’s education because they did not engage in school activities. A male parent expressed his lack of involvement by saying, “I have not been to my child’s school for two years, and I am unaware of any effort to promote my involvement except when the school needed me to contribute funds” (Parent #06, male).

3.2.2. Parent-to-parent interactions

Having spaces for interaction between and among parents was reported to influence parental involvement positively. Such opportunities provided valuable support and allowed parents to share their experiences, which many found beneficial. One parent pointed out, “No man is an island, as the saying goes. Meeting as a group will help us because we can share ideas and find ways to assist parents who struggle to help their children” (Parent #04, male). This statement underscores the potential value of peer-support networks for parents. However, participants also discussed the lack of formal structures that could facilitate such interactions, indicating an area where policy and school initiatives could significantly impact. For instance, a child observed, “Parents do not work together here. Everyone is doing things. So, we cannot say that my parents influence other people.” (Child #06, male). During the focus group with teachers, it was reported that there was no coordinated responsibility to enable structured interactions with parents. Female teacher #4 expressed that promoting interaction, whether by parents, teachers, or an organisation, would encourage more parents to participate in their children’s school activities.

3.2.3. External Support from the Community

Community leaders, such as members of school committees and village heads, commended their positive role in encouraging parents to be more supportive of their children with disabilities. The leaders often conducted follow-ups and questioned parents about whether their children were missing from the school. A male parent shared, “The committee helps gain new knowledge and skills to support their children’s performance in class better” (Parent #01, male). Despite the positive role of community leaders, not all parents have access to such support, which highlights the need for more structured and widespread community-based interventions. Another male parent reported, “I have never met with any authorities, teachers, community, or other parents concerning my child’s education. Maybe because I have just been here for a few months, I have not observed any efforts to get people to work together to support children with disabilities” (Parent #04, male).

3.3. Motivation

Insights from the interviews highlighted the influence of positive motivational beliefs and perceptions about parental roles, the benefits of involvement, and attitudes towards the child’s education and future. These factors can either motivate or hinder parental involvement. Understanding these factors as motivators and barriers is crucial for creating effective strategies to increase parental engagement in their children’s education.

3.3.1. Perceptions about Roles and Responsibilities

Teachers highlighted the importance of parents actively communicating their children’s needs to the school. Specifically, Teacher #02, a female educator, stressed the importance of proactive parental involvement, stating, “If they notice that their children are facing challenges, parents should make an effort to approach the teacher and provide a comprehensive explanation of the situation.” This underscores the mutual responsibility shared between parents and educators to address students’ needs. In our discussions, both children and parents agreed that if parents also acknowledge their responsibilities as caregivers at home and school, they can provide more support to their children. Understanding and appreciating their roles and responsibilities as caregivers in both environments can significantly increase parental involvement in supporting their children.

3.3.2. Future Optimism and Beliefs about Education

Parents’ hopefulness regarding their children’s future has been reported to play a significant role in their level of involvement. Those who believed in the long-term benefits of education were more likely to invest time and resources. A female parent, identified as #02, stated, “I often stop doing some things and go to support my child’s education. This includes activities such as going to the farm and washing clothes. I do so because I want her to rely on herself in the future.” Optimism often translates to higher levels of involvement. One child mentioned, “Our performance will improve if our parents help us, and we will score good grades after writing primary school exams.” (Child #05, male). During the discussions, children and parents also agreed that if parents also appreciate their responsibilities as caregivers at home and school, they will be able to offer more support to their children. Understanding and appreciating their roles and responsibilities as caregivers, both at home and school, can have a significant positive impact on parental involvement in supporting their children.

4. Discussion

This section analyses and discusses the results concerning our research objectives and the existing literature. We also emphasise Malawian parents’ unique challenges and similarities compared with those in other low-income countries. In addition, we discuss the implications of our findings for policy, practice, and future research. Overall, the findings point to the interaction between capability, opportunity, and motivation as influencing factors in parental involvement. The research shows that the level of knowledge and understanding of disability-related matters that a parent has could directly influence their ability to access and utilise resources and support systems that are available to them. This insight emphasises the vital link between parental understanding of disability issues and their capacity to leverage resources (capability) and the support systems accessible to them (opportunity). Such interactions would, in turn, affect their motivation to participate more actively in their children’s education. Therefore, parents who were more aware of and had better access to supportive environments would be more motivated to participate. In contrast, those with limited resources would show lower levels of involvement.

4.1. Capability to Get Involved

Previous research has indicated a correlation between enhanced parental knowledge or understanding of issues affecting children and greater participation and involvement [51,52]. In contrast, other studies in Uganda, Kenya, and Ethiopia have suggested that negative attitudes towards disabilities hinder parental involvement [50,51,52]. Additionally, a case study of a low-income school community in South Africa, which examined teachers’ perceptions of parental involvement, aligns with our findings that time constraints, particularly work demands, such as farming, also influence parental ability to engage [56]. Thus, there is a need for more educational programs designed to help families of children with disabilities better understand their children and improve their understanding of disabilities and their roles in the educational process [57,58]. The perception of disability as a divine punishment is deeply rooted in cultural beliefs that significantly shape parental attitudes and behaviours [59]. This view not only affects the amount of support that parents can offer to their children but also reinforces societal stigma, which results in further marginalisation of children with disabilities. Interventions must incorporate culturally sensitive approaches to challenging deep-seated beliefs [57]. Research in similar low-income settings has demonstrated that community-based education programs involving religious and cultural leaders can be pivotal in shifting harmful narratives and promoting inclusive attitudes towards disabilities [55,61]. These programmes can help reframe disability as a condition that requires community support rather than being viewed through the lens of cultural stigma.

Caring for family members and children with disabilities is a complex responsibility parents must manage [

19]. Parents of children from low-income households find it particularly challenging to prioritise the education of children with disabilities in the face of competing priorities, a finding consistent with other recent studies in LMICs [

9,62]. Other scholars have concluded that economic hardships can force parents to prioritise immediate subsistence activities over educational involvement, as noted in studies from Nigeria and Ghana [63,64]. Addressing these economic barriers requires a multi-faceted approach, including community-based support systems that can alleviate the financial burden on families [65]. Recognising the considerable time constraints faced by parents due to their economic activities, it is worth noting that parents need flexible interventions to support their children’s education while balancing their work schedules.

4.2. Opportunities for Involvement

This study shows that opportunities for parental involvement are shaped by the interplay among school openness, community support, and financial constraints. Schools with proactive engagement strategies have higher levels of parental involvement. This is consistent with previous research indicating the importance of positive school-home relationships [63,64]. Schools with proactive engagement strategies and positive teacher attitudes tend to have higher levels of parental involvement, as observed in Malawi and other African countries such as Kenya and Tanzania [61,65]. Consistent and structured engagement opportunities are essential to enhance parental involvement.

Collaboration and interactions among parents, teachers, and the wider community were considered essential for parental involvement, although they were limited to this study. Enhancing communication and establishing structured collaborative processes are paramount for parental involvement in the education of children with disabilities [66,67]. Research has shown that positive teacher-parent relationships and strong community ties enhance parental involvement and support for children [71]. For instance, support from teachers with positive attitudes towards parental involvement can create a supportive environment that fosters trust, self-efficacy, and motivation [67,72]. Children’s educational support is likely higher if parents feel invited and welcome to the school [66]. The positive impact of community leaders and the potential for peer support highlights the need for more robust collaborative interventions and peer support systems for parents [73,74,75].

4.3. Motivation for Involvement

Positive perceptions of parental roles, beliefs about the benefits of involvement, and optimistic attitudes towards the education of children with disabilities were the primary drivers of parental involvement. Parents who viewed involvement as part of their responsibilities were more engaged, which is consistent with prior research in other contexts [76,77,78] that found that positive parental attitudes and high aspirations for their children’s future can significantly increase involvement [76,77]. In addition, in our study, optimism about the children’s future was a strong motivator, consistent with previous studies [

7,

36]. Mizunoya (2019) noted that parents decide whether to send their children to school based on how much they value education, the cost of schooling, the opportunities their children miss by going to school, how they value their time, and the benefits they expect from education [

26]. These findings also align with another recent study in Malawi and Bangladesh that reported caregivers’ recognition of the importance of school for their children’s future livelihoods or at least as a means of socialisation [81]. Therefore, it is crucial to recognise and enhance these motivating factors when developing interventions for parental involvement.

4.4. Comparison with Other Countries

The difficulties experienced by parents in Malawi in supporting the education of children with disabilities are unique and comparable to those encountered in low-income environments. For instance, economic hardships, as experienced in countries like Nigeria and Ghana, often force parents to prioritise immediate subsistence over educational involvement, limiting their capacity to support their children’s education [63,64]. Additionally, the cultural stigma surrounding disability is pronounced in Malawi, which is also true in other countries such as Bangladesh, Uganda, Kenya, and Zimbabwe [

32,51,52,58,62]. Furthermore, while Malawi’s inclusive education policies face implementation challenges, similar struggles have been observed in Kenya, India, and Tanzania, where resource limitations and inadequate teacher training have hindered parental engagement [

36,65]. Finally, community-led initiatives have seen success in countries such as Uganda, Ghana, and Brazil [50,70,72,79,80], highlighting the need for similar approaches to bolster parental involvement in Malawi. These findings also show the potential opportunities for civil society organisations, such as the CCAP’s Education Programs in Malawi, to develop family-focused interventions to enhance parental support through targeted intervention.

4.5. Strengths and Limitations

This study has several strengths that enhance the robustness and credibility of its findings. Including diverse participants, such as children with disabilities, their parents, and teachers, offers a comprehensive view of the factors that affect parental involvement. This approach enhanced the validity of the findings through triangulation [84]. Furthermore, utilising the COM-B model as a theoretical framework allows for a multi-faceted analysis of the factors that impact parental involvement. This model provided a comprehensive framework for understanding the dynamics of parental involvement. The application of this model adds depth to the study and helps examine the intricate web of factors that influence parental involvement.

Nonetheless, it is worth noting that while beneficial, there remain questions regarding the universal applicability of COM-B, especially in low-income countries and settings. The model originated from high-income contexts, and therefore, it may only, and to an extent, partially draw into Malawi’s deep-rooted cultural beliefs, economic constraints, and other systemic barriers. For instance, the model’s assumption that individual and environmental factors primarily drive behaviour change potentially overlooks the influence of communal practices and social norms, which are particularly significant in Malawian society. Additionally, the model may not adequately address the role of external systemic factors, such as the limited infrastructure and resources in rural Malawi, which can severely restrict parental involvement regardless of the individual capabilities or motivations of parents in these settings [

6,

9,55].

Another limitation of the study is the inherent selection bias that could have been introduced by engaging school principals, teachers, and community leaders to identify the study participants. Although specific criteria were set, relying on a purposefully selected group of parents, teachers, and children may have resulted in a nonrepresentative sample of the general population. Some interview participants may not have been incredibly involved in their children’s education, yet others may have provided exaggerated or overly optimistic responses due to perceived social expectations [47]. Future studies should explore alternative sampling techniques, such as randomly selecting participants or involving an impartial third party in the selection process. Broadening the criteria for participant selection to include a broader range of respondents from different schools, regions, and countries would help reach a more diverse and representative sample.

5. Conclusions

In conclusion, this study provides a foundational understanding of the complex factors influencing parental involvement in Malawi, offering actionable insights for policymakers, educators, and community leaders aiming to enhance educational outcomes for children with disabilities. This study contributes significantly to the understanding of parental involvement in the education of children with disabilities in low-income settings, particularly in Malawi. By exploring the unique challenges and facilitators within this context, such as cultural beliefs, financial constraints, and the role of community support, this study highlights the critical need for tailored interventions. The implications of this study are profound in terms of both policy and practice.

The findings from this research underscore the need for targeted interventions that enhance parental literacy and understanding of disabilities, improve access to resources and support systems, and shift societal attitudes through community engagement. Parent-focused interventions should address barriers, such as enhancing parental literacy, fostering positive school-home relationships, and establishing structured peer support systems. Future research should focus on developing and testing culturally sensitive intervention strategies that account for the reality of people from low-income families. Specifically, studies should explore the effectiveness of community-based programs that involve local leaders and religious figures in shifting societal attitudes towards disability.

Longitudinal studies are needed to assess the long-term impact of parental involvement interventions on the educational outcomes of children with disabilities. These findings offer a basis for future research and interventions to enhance educational opportunities for children with disabilities in low-income settings. By addressing parental involvement through tailored programs, community engagement, flexible participation models, and inclusive policies, future research can contribute to more effective strategies to improve the educational outcomes for these children.

Author Contributions

Conceptualisation, DM; methodology, DM, and TM; writing—original draft preparation, DM; writing—review and editing, DM, SP, DP, MZ, and TM. All the authors have read and agreed to the published version of the manuscript.

Funding

This study received no external funding.

Institutional Review Board Statement

The study was conducted in accordance with the Declaration of Helsinki and approved by the Ethics Committees of the University of Livingstonia, Malawi (Ref. no. UNILIA-REC/3//JDM/2019) on 19th March 2019 and the LSHTM (ref. no. 16239) on the 2nd May 2019.

Informed Consent Statement

Informed consent was obtained from all subjects involved in the study.

Data Availability Statement

The original contributions of this study are included in the article. Further inquiries can be directed to the corresponding authors.

Acknowledgements

(Anonymised)

Conflicts of Interest

The authors declare no conflict of interest.

References

- B. O. Olusanya, V. Kancherla, A. Shaheen, F. A. Ogbo, and A. C. Davis, ‘Global and regional prevalence of disabilities among children and adolescents: Analysis of findings from global health databases’, Front Public Health, vol. 10, Sep. 2022. [CrossRef]

- UNICEF, Seen, Counted, Included: Using data to shed light on the well-being of children with disabilities—UNICEF DATA. New York: UNICEF, 2021. Accessed: Mar. 27, 2023. [Online]. Available: https://data.unicef.org/resources/children-with-disabilities-report-2021/.

- F. B. Mbazzi et al., ‘The impact of COVID-19 measures on children with disabilities and their families in Uganda’. https://doi.org/10.1080/09687599.2020.1867075, vol. 37, no. 7, pp. 1173–1196, 2021. [CrossRef]

- C. Male and Q. Wodon, ‘Disability Gaps in Educational Attainment and Literacy ’, Disability Gaps in Educational Attainment and Literacy: The Price of Exclusion: Disability and Education, 2017.

- M. G. Wondim, D. Asrat Getahun, and D. N. Golga, ‘Parental involvement in the education of their children with disabilities in primary schools of Bahir Dar, Ethiopia: Do education, income and employment status matter?’, Journal of Research in Special Educational Needs, vol. 21, no. 2, pp. 86–97, Apr. 2021. [CrossRef]

- H. Kuper et al., ‘The Impact of Disability on the Lives of Children; Cross-Sectional Data Including 8,900 Children with Disabilities and 898,834 Children without Disabilities across 30 Countries’, PLoS One, vol. 9, no. 9, p. e107300, Sep. 2014. [CrossRef]

- L. Foreman-Murray, S. Krowka, and C. E. Majeika, ‘A systematic review of the literature related to dropout for students with disabilities’. https://doi.org/10.1080/1045988X.2022.2037494, vol. 66, no. 3, pp. 228–237, 2022. [CrossRef]

- S. Tanya Lereya, S. Cattan, Y. Yoon, R. Gilbert, and J. Deighton, ‘How does the association between special education need and absence vary overtime and across special education need types?’, Eur J Spec Needs Educ, 2022. [CrossRef]

- L. M. Banks, H. Kuper, and S. Polack, ‘Poverty and disability in low- and middle-income countries: A systematic review’, PLoS One, vol. 12, no. 12, p. e0189996, Dec. 2017. [CrossRef]

- N. Singal, ‘Schooling children with disabilities: Parental perceptions and experiences’, Int J Educ Dev, vol. 50, pp. 33–40, Sep. 2016. [CrossRef]

- K. Persson, ‘What Defines a Parent?’, 2019.

- S. E. Goldman and M. M. Burke, ‘The Effectiveness of Interventions to Increase Parent Involvement in Special Education: A Systematic Literature Review and Meta-Analysis’, Apr. 03, 2017, Routledge. [CrossRef]

- A. Lendrum, A. Barlow, and N. Humphrey, ‘Developing positive school-home relationships through structured conversations with parents of learners with special educational needs and disabilities (SEND)’, Journal of Research in Special Educational Needs, vol. 15, no. 2, pp. 87–96, 2015. [CrossRef]

- M. Alflasi, F. Al-Maadadi, and C. Coughlin, ‘Perspectives of family-school relationships in Qatar based on Epstein’s model of six types of parent involvement’, 2018. [CrossRef]

- N. E. El Nokali, H. J. Bachman, and E. Votruba-Drzal, ‘Parent Involvement and Children’s Academic and Social Development in Elementary School’, Child Dev, vol. 81, no. 3, p. 988, May 2010. [CrossRef]

- J. L. Epstein, ‘School, family and community partnerships: Preparing educators and improving schools’, School, Family, and Community Partnerships: Preparing Educators and Improving Schools, Second Edition, pp. 1–634, Jan. 2018. [CrossRef]

- M. Roy and R. Giraldo-García, ‘The Role of Parental Involvement and Social/ Emotional Skills in Academic Achievement: Global Perspectives’, Sch Comm J, vol. 28, no. 2, 2018, Accessed: Jul. 22, 2024. [Online]. Available: http://www.schoolcommunitynetwork.org/SCJ.aspx.

- K. Bani Odeh and L. M. Lach, ‘Barriers to, and facilitators of, education for children with disabilities worldwide: a descriptive review’, Front Public Health, vol. 11, p. 1294849, 2023. [CrossRef]

- W. Abu-Ras, M. Saleh, and A. Birani, ‘Challenges and Determination: The Case of Palestinian Parents of Children With Disabilities’. https://doi.org/10.1177/0192513X18757830, vol. 39, no. 10, pp. 2757–2780, Mar. 2018. [CrossRef]

- J. E. Lansford, ‘Cross-Cultural Similarities and Differences in Parenting’, J Child Psychol Psychiatry, vol. 63, no. 4, p. 466, Apr. 2022. [CrossRef]

- D. J. Musendo et al., ‘A Systematic Review of Interventions Promoting Parental Involvement in the Education of School-Aged Children With Disabilities’, Dec. 01, 2023, Cambridge University Press. [CrossRef]

- A. Garcia, M. Rosario De Guzman, A. S. Garcia, M. Rosario, T. De Guzman, and—A S Garcia, ‘The meanings and ways of parental involvement among low-The meanings and ways of parental involvement among low-income Filipinos income Filipinos The meanings and ways of parental involvement among low-income Filipinos’, Childhood Research Quarterly, vol. 53, pp. 343–354, 2020. [CrossRef]

- K. Edge, A. Marphatia, E. Legault, and D. Archer, ‘Researching education outcomes in Burundi, Malawi, Senegal and Uganda: using participatory tools and collaborative approaches : The Improving Learning Outcomes in Primary Schools (ILOPS) Project | Project methodology’, In Researching education outcomes in Burundi, Malawi, Senegal and Uganda: using participatory tools and collaborative approaches. ActionAid/Institute of Education: London. (2010), 2010.

- G. Erlendsdóttir, M. A. Macdonald, S. R. Jónsdóttir, and P. Mtika, ‘Parental involvement in children’s primary education: A case study from a rural district in Malawi’, S Afr J Educ, vol. 42, no. 3, Aug. 2022. [CrossRef]

- K. Foster and C. Child, ‘Does My Child’s Educational Success Depend on Me? A Qualitative Analysis of Parents and Teachers Addressing Barriers to Education Throughout Malawi’, 2020.

- S. Mizunoya, S. Mitra, and I. Yamasaki, ‘Disability and school attendance in 15 low- and middle-income countries’, World Dev, vol. 104, pp. 388–403, Apr. 2018. [CrossRef]

- National Statistics Office, ‘2018 Malawi Population ’, 2019. Accessed: Feb. 15, 2022. [Online]. Available: http://www.nsomalawi.mw/images/stories/data_on_line/demography/census_2018/2018%20Malawi%20Population%20and%20Housing%20Census%20Main%20Report.pdf.

- M. Chitiyo et al., ‘Exploring Teachers’ Special and Inclusive Education Professional Development Needs in Malawi, Namibia, and Zimbabwe’, International Journal of Whole Schooling, vol. 15, no. 1, pp. 28–49, 2019, [Online]. Available: http://ezproxy.library.yorku.ca/login?url=https://search.proquest.com/docview/2228646346?accountid=15182%0Ahttp://sfx.scholarsportal.info/york?url_ver=Z39.88-2004&rft_val_fmt=info:ofi/fmt:kev:mtx:journal&genre=article&sid=ProQ:ProQ%3Aeric&atitle=Exploring.

- S. and T. Ministry of Education, ‘National Inclusive Education Strategy of 2017 –2022 ’, 2017.

- J. Lee, ‘“I always tell my children to learn from me”: Parental engagement in social and emotional learning in Malawi.’, Int J Educ Res, vol. 116, p. 102090, Jan. 2022. [CrossRef]

- W. Pasidya and B. Murugan, ‘Assessing The Barriers To Parental Involvement In Early Childhood Development Education In Blantyre Rural Area: A Case Study Of T/A Kuntaja’, Certified Journal International Journal of Humanities Social Science and Management (IJHSSM), vol. 3, no. 4, pp. 856–865, 2023, Accessed: Jul. 23, 2024. [Online]. Available: www.ijhssm.org.

- L. M. Banks, X. Hunt, K. Kalua, P. Nindi, M. Zuurmond, and T. Shakespeare, ‘“I might be lucky and go back to school”: Factors affecting inclusion in education for children with disabilities in rural Malawi’, Afr J Disabil, vol. 11, 2022. [CrossRef]

- M. L. Banks and M. Zuurmond, ‘Barriers and enablers to inclusion in education for children with disabilities in Malawi’, pp. 1–42, 2015.

- S. H. Braathen and A. Munthali, ‘Disability and education: Qualitative case studies from Malawi Summary of results Authors Disability and education: Qualitative case studies from Malawi’, 2016, Accessed: Jul. 23, 2024. [Online]. Available: www.sintef.no.

- G. Mbewe, E. Kamchedzera, M. Esthery, and D. Kunkwenzu, ‘Exploring Implementation of National Special Needs Education Policy Guidelines in Private Secondary Schools’, IAFOR Journal of Education: Inclusive Education, vol. 9, 2021.

- N. Singal, J. Mbukwa-Ngwira, S. Taneja-Johansson, P. Lynch, G. Chatha, and E. Umar, ‘Impact of Covid-19 on the education of children with disabilities in Malawi: reshaping parental engagement for the future’. https://doi.org/10.1080/13603116.2021.1965804, 2021. [CrossRef]

- M. Tataryn et al., ‘Childhood disability in Malawi: A population-based assessment using the key informant method’, BMC Pediatr, vol. 17, no. 1, pp. 1–12, Nov. 2017. [CrossRef]

- S. Michie, M. M. van Stralen, and R. West, ‘The behaviour change wheel: A new method for characterising and designing behaviour change interventions’, Implementation Science, vol. 6, no. 1, pp. 1–12, Apr. 2011. [CrossRef]

- L. Atkins and S. Michie, ‘Designing interventions to change eating behaviours’, Proc Nutr Soc, vol. 74, no. 2, pp. 164–170, May 2015. [CrossRef]

- K. Murphy et al., ‘Using the COM-B model and Behaviour Change Wheel to develop a theory and evidence-based intervention for women with gestational diabetes (IINDIAGO)’, BMC Public Health, vol. 23, no. 1, Dec. 2023. [CrossRef]

- S. O. Ojo, D. P. Bailey, D. J. Hewson, and A. M. Chater, ‘Perceived barriers and facilitators to breaking up sitting time among desk-based office workers: A qualitative investigation using the TDF and COM-B’, Int J Environ Res Public Health, vol. 16, no. 16, Aug. 2019. [CrossRef]

- C. Flannery et al., ‘Enablers and barriers to physical activity in overweight and obese pregnant women: an analysis informed by the theoretical domains framework and COM-B model’, BMC Pregnancy Childbirth, vol. 18, no. 1, May 2018. [CrossRef]

- A. Erzse et al., ‘A Mixed-Methods Participatory Intervention Design Process to Develop Intervention Options in Immediate Food and Built Environments to Support Healthy Eating and Active Living among Children and Adolescents in Cameroon and South Africa’, Int J Environ Res Public Health, vol. 19, no. 16, p. 10263, Aug. 2022. [CrossRef]

- F. Oporia et al., ‘Development and validation of an intervention package to improve lifejacket wear for drowning prevention among occupational boaters on Lake Albert, Uganda’, Injury Prevention, vol. 29, no. 6, pp. 493–499, Dec. 2023. [CrossRef]

- J. W. Creswell and C. Poth, ‘Qualitative inquiry & research design : choosing among five approaches / John W. Creswell, University of Michigan, Cheryl N. Poth, University of Alberta.’, Qualitative inquiry and research design, pp. 75–82, 2018, Accessed: Aug. 12, 2024. [Online]. Available: https://books.google.com/books/about/Qualitative_Inquiry_and_Research_Design.html?id=Pz5RvgAACAAJ.

- Patton, ‘Qualitative Research & Evaluation Methods Integrating Theory and Practice FOURTH EDITION. SAGE PUBLICATIONS, pp. 107–134, 2000.

- Government of Malawi, ‘Nkhata Bay District Council Socio-Economic Profile 2017–2022’, 2020. Accessed: Nov. 08, 2022. [Online]. Available: https://global-uploads.webflow.com/6061a9d807f5368139d1c52c/610b22d532a91182c128eea6_Nkhata-Bay-District-Council-Socio-Economic-Profile-2017-2022.pdf.

- Washington Group, ‘The Washington Group Short Set on Functioning (WG-SS)’, 2020, Accessed: Dec. 31, 2021. [Online]. Available: http://www.washingtongroup-disability.com/.

- T. Slettebø, ‘Participant validation: Exploring a contested tool in qualitative research’. https://doi.org/10.1177/1473325020968189, vol. 20, no. 5, pp. 1223–1238, Oct. 2020. [CrossRef]

- S. K. Ahmed, ‘The pillars of trustworthiness in qualitative research’, Journal of Medicine, Surgery, and Public Health, vol. 2, p. 100051, Apr. 2024. [CrossRef]

- M. Durisic and M. Bunijevac, ‘Parental involvement as an important factor for successful education’, 2017. [CrossRef]

- A. Paget, M. Mallewa, D. Chinguo, C. Mahebere-Chirambo, and M. Gladstone, ‘“It means you are grounded”—caregivers’ perspectives on the rehabilitation of children with neurodisability in Malawi’, Disabil Rehabil, vol. 38, no. 3, p. 223, Jan. 2016. [CrossRef]

- M. Gedfie and D. Negassa, ‘Parental Involvement in the Education of their Children with Disabilities: the case of Primary Schools of Bahir Dar City Administration, Ethiopia’, East African Journal of Social Sciences and Humanities, vol. 3, no. 2, pp. 43–56, Dec. 2018, Accessed: Mar. 27, 2023. [Online]. Available: https://www.haramayajournals.org/index.php/ejsh/article/view/820.

- J. Oranga, E. Obuba, I. Sore, F. Boinett, and J. Oranga, ‘Parental Involvement in the Education of Learners with Intellectual Disabilities in Kenya’, Journal 2022, vol. 9, p. 8542, 2022. [CrossRef]

- F. B. Mbazzi et al., ‘“Obuntu Bulamu”—Development and Testing of an Indigenous Intervention for Disability Inclusion in Uganda’, Scandinavian Journal of Disability Research, vol. 22, no. 1, pp. 403–416, 2020. [CrossRef]

- O. Ikechukwu, ‘Exploring teachers’ perceptions of parental involvement via the capability approach: A case of a low-income school community.’, 2017, Accessed: Jul. 23, 2024. [Online]. Available: https://etd.uwc.ac.za:443/xmlui/handle/11394/6290.

- J. Jang, G. Kim, H. Jeong, N. Lee, and S. Oh, ‘Meta-analysis on the effectiveness of parent education for children with disabilities’, World J Clin Cases, vol. 11, no. 29, p. 7082, Oct. 2023. [CrossRef]

- H. M. Kim, ‘Keyword Network Analysis through Big Data on Well-being of Young Children with Disabilities’, Asia-Pacific Journal of Research in Early Childhood Education, vol. 18, no. 1, pp. 55–79, 2024. [CrossRef]

- I. Babik and E. S. Gardner, ‘Factors Affecting the Perception of Disability: A Developmental Perspective’, Front Psychol, vol. 12, Jun. 2021. [CrossRef]

- C. Masulani-Mwale, D. Mathanga, F. Kauye, and M. Gladstone, ‘Psychosocial interventions for parents of children with intellectual disabilities–A narrative review and implications for low-income settings’, Ment Health Prev, vol. 11, no. June, pp. 24–32, 2018. [CrossRef]

- J. A. K. Harrison et al., ‘Access to health care for people with disabilities in rural Malawi: What are the barriers?’, BMC Public Health, vol. 20, no. 1, pp. 1–17, Jun. 2020. [CrossRef]

- I. Mactaggart et al., ‘Livelihood opportunities amongst adults with and without disabilities in Cameroon and India: A case-control study’, PLoS One, vol. 13, no. 4, p. e0194105, Apr. 2018. [CrossRef]

- B. O. Abdu-Raheem, ‘Parents’ Socio-Economic Status as Predictor of Secondary School Students’ Academic Performance in Ekiti State, Nigeria.’, Journal of Education and Practice, vol. 6, no. 1, pp. 123–128, 2015, Accessed: Jul. 23, 2024. [Online]. Available: www.iiste.org.

- A. Merryness and C. Rupia, ‘Effectiveness of Parental Involvement in Management of Primary Schools in Kyerwa District’, Journal of Research Innovation and Implications in Education, vol. 6, no. 3, pp. 201–209, 2022, Accessed: Jul. 23, 2024. [Online]. Available: www.jriiejournal.com.

- T. L. Baker, J. Wise, G. Kelley, and R. J. Skiba, ‘Identifying Barriers: Creating Solutions to Improve Family Engagement’, Sch Comm J, vol. 26, no. 2, 2016, Accessed: Jul. 30, 2024. [Online]. Available: http://www.schoolcommunitynetwork.org/SCJ.aspx.

- C. E. Fishman and A. B. Nickerson, ‘Motivations for Involvement: A Preliminary Investigation of Parents of Students with Disabilities’, Journal of Child and Family Studies 2014 24:2, vol. 24, no. 2, pp. 523–535, Jan. 2014. [CrossRef]

- K. M. Minke, S. M. Sheridan, E. M. Kim, J. H. Ryoo, and N. A. Koziol, ‘Congruence in Parent-Teacher Relationships’. https://doi.org/10.1086/675637, vol. 114, no. 4, pp. 527–546, Jul. 2015. [CrossRef]

- C. N. Mwarari, P. Githui, and M. Mwenje, ‘PARENTAL INVOLVEMENT IN THE IMPLEMENTATION OF COMPETENCY BASED CURRICULUM KENYA: PERCEIVED CHALLENGES AND OPPORTUNITIES’, American Journal of Humanities and Social Sciences Research, no. 3, pp. 201–208, 2020, Accessed: Jul. 23, 2024. [Online]. Available: www.ajhssr.com.

- K. Mortier, P. Hunt, L. Desimpel, and G. Van Hove, ‘With parents at the table: Creating supports for children with disabilities in general education classrooms’, Eur J Spec Needs Educ, vol. 24, no. 4, pp. 337–354, 2009. [CrossRef]

- E. Spier et al., ‘Parental, Community, and Familial Support Interventions to Improve Children’s Literacy in Developing Countries: A Systematic Review’, Campbell Systematic Reviews, vol. 12, no. 1, pp. 1–98, 2016. [CrossRef]

- Chima Abimbola Eden, Onyebuchi Nneamaka Chisom, and Idowu Sulaimon Adeniyi, ‘PARENT AND COMMUNITY INVOLVEMENT IN EDUCATION: STRENGTHENING PARTNERSHIPS FOR SOCIAL IMPROVEMENT’, International Journal of Applied Research in Social Sciences, vol. 6, no. 3, pp. 372–382, Mar. 2024. [CrossRef]

- J. Katenga, ‘One Purpose, Multiple Realities: A Qualitative Study on Parental Involvement tn Two Malawian Private Secondary Schools’, ProQuest Dissertations and Theses, vol. 20, no. 1, p. 339, 2017, [Online]. Available: https://search.proquest.com/dissertations-theses/one-purpose-multiple-realities-qualitative-study/docview/1904513360/se-2?accountid=41849.

- R. Nalugya et al., ‘Obuntu bulamu: Parental peer-to-peer support for inclusion of children with disabilities in Central Uganda’, Afr J Disabil, vol. 12, 2023. [CrossRef]

- L. Bray, B. Carter, C. Sanders, L. Blake, and K. Keegan, ‘Parent-to-parent peer support for parents of children with a disability: A mixed method study’, Patient Educ Couns, vol. 100, no. 8, pp. 1537–1543, Aug. 2017. [CrossRef]

- M. Zuurmond et al., ‘A support programme for caregivers of children with disabilities in Ghana: Understanding the impact on the well-being of caregivers’, Child Care Health Dev, vol. 45, no. 1, pp. 45–53, Jan. 2019. [CrossRef]

- A. M. Ishimaru, ‘From Family Engagement to Equitable Collaboration’. https://doi.org/10.1177/0895904817691841, vol. 33, no. 2, pp. 350–385, Mar. 2017. [CrossRef]

- S. Park and S. Holloway, ‘Parental Involvement in Adolescents’ Education: An Examination of the Interplay among School Factors, Parental Role Construction, and Family Income.’, Sch Comm J, vol. 28, no. 1, pp. 9–36, 2018, Accessed: Jul. 23, 2024. [Online]. Available: http://www.schoolcommunitynetwork.org/SCJ.aspx.

- W. H. Jeynes, ‘The Relationship Between Parental Involvement and Urban Secondary School Student Academic Achievement: A Meta-Analysis’ http://dx.doi.org/10.1177/0042085906293818, vol. 42, no. 1, pp. 82–110, Aug. 2016. [CrossRef]

- C. Tabaro, J. D’, and A. Uwamahoro, ‘Parental involvement in children’s education in Rwanda: A case study of vulnerable families from Shyogwe Sector in Muhanga District’, International Journal of Contemporary Applied Researches, vol. 7, no. 2, 2020, Accessed: Jul. 23, 2024. [Online]. Available: www.ijcar.net.

- Z. Yılmaz Bodur and S. Aktan, ‘A Research on the Relationship between Parental Attitudes, Students’ Academic Motivation and Personal Responsibility’, International Journal on Social and Education Sciences (IJonSES), vol. 3, no. 4, pp. 636–655, 2021. [CrossRef]

- K. Aruldas et al., ‘“If he has education, there will not be any problem”: Factors affecting access to education for children with disabilities in Tamil Nadu, India’, PLoS One, vol. 18, no. 8, Aug. 2023. [CrossRef]

- T. Smythe et al., ‘The Role of Parenting Interventions in Optimising School Readiness for Children With Disabilities in Low and Middle-Income Settings’, Front Pediatr, vol. 10, p. 1072, Jun. 2022. [CrossRef]

- T. Smythe, A. Duttine, A. C. D. Vieira, B. da S. M. de Castro, and H. Kuper, ‘Engagement of Fathers in Parent Group Interventions for Children with Congenital Zika Syndrome: A Qualitative Study’, Int J Environ Res Public Health, vol. 16, no. 20, Oct. 2019. [CrossRef]

- O. Palikara, S. Castro, C. Gaona, and V. Eirinaki, ‘Capturing the Voices of Children in the Education Health and Care Plans: Are We There Yet?’, Front Educ (Lausanne), vol. 3, p. 24, Apr. 2018. [CrossRef]

|

Disclaimer/Publisher’s Note: The statements, opinions and data contained in all publications are solely those of the individual author(s) and contributor(s) and not of MDPI and/or the editor(s). MDPI and/or the editor(s) disclaim responsibility for any injury to people or property resulting from any ideas, methods, instructions or products referred to in the content. |

© 2024 by the authors. Licensee MDPI, Basel, Switzerland. This article is an open access article distributed under the terms and conditions of the Creative Commons Attribution (CC BY) license (http://creativecommons.org/licenses/by/4.0/).