1. Introduction

Parental involvement is crucial in supporting the education of children with disabilities, particularly in low-income countries, where educational resources and support systems are often limited [

1,

2]. This paper uses the term ‘parental involvement’ to describe various behaviours and activities by parents or other primary caregivers, including supporting children’s learning at home, volunteering in schools, participating in school events, attending parent-teacher conferences, and advocating for children’s needs within the educational system [

3,

4]. Several studies have shown that active parental involvement is a key factor in enhancing children’s academic performance, social skills, and emotional development [

5,

6,

7].

The prevalence of childhood disabilities in Malawi is high. According to the 2018 Malawi Population and Housing Census, the prevalence of disability among children in Malawi is approximately 6% [

8,

9]. The nation has a clear and urgent need for targeted interventions to support both children with disabilities and their families. However, practical challenges, such as socioeconomic constraints and cultural stigma hinder parental involvement in the education of children with disabilities (Nelson et al., 2017; Njelesani et al., 2024). Masulani-Mwale et al. (2018) found only 30% of parents of children with intellectual disabilities in Malawi actively engaged in their children’s education, mainly because of a lack of knowledge and community support [12]. Cultural beliefs and practices, such as keeping children with disabilities at home, away from public life or the reluctance to send them to school at an appropriate age, further exacerbate the situation, leading to their exclusion from educational opportunities (Idrissa, 2022). For example, recent research in some parts of rural Malawi found that some parents prefer to keep these children at home due to the culture of discrimination (Njelesani et al., 2024). Additionally, the education system itself is often ill-equipped to accommodate children with disabilities [14]. These challenges limit parental abilities to support their children’s education, making it even more difficult for children with disabilities to access the educational opportunities which they need to thrive [15,16].

There is growing evidence suggesting that intervention programmes for parents of children with disabilities can lead to improvement in various areas of life. Studies in Ghana, Kenya, and South Africa have demonstrated that children with disabilities whose parents are actively involved in their education exhibit higher academic and social performance [17,18,19]. Parental involvement can support individual academic success and contribute to better societal integration for children with disabilities In addition, parents can also benefit from enhanced confidence and competence in supporting their children’s education, contributing to more empowered and resilient family units [

7]. Therefore, in many low-resource settings such as Malawi, improving parental involvement can be beneficial for both children with disabilities and their parents [20].

A systematic review by He et al. (2014) reported that group-based caregiver support interventions for children with disabilities in Low and Middle Income Countries (LMICs) could help to reduce social isolation and stigma [21]. Specific examples of parental or caregiver interventions include the participatory group ‘Juntos’ programme in Brazil [22], caregiver education through peer groups in Ghana [23], and the Obuntu Bulamu peer-to-peer support intervention in Uganda [24,25]. However, most existing research and interventions have been developed in high-income contexts [

1,25,26], and there is a substantial gap in understanding how they can be adapted or developed in low-income settings [17,19]. In addition, the few existing parental involvement interventions typically consist of a single strategy and focus only on family/parental characteristics, beliefs, and behaviours, without sufficient attention to the wider context and role of systematic and structural factors [

6,27]. To address these challenges, interventions must be grounded in robust theoretical frameworks and explicitly tailored to low-income settings.

1.1. Theoretical Frameworks and Guidance

The Medical Research Council (MRC) recommends that the development of complex interventions be guided by appropriate evidence and a cohesive theoretical framework [28]. Theoretical frameworks and co-design methods may enhance the acceptability and effectiveness of interventions [29]. This study employed a co-design approach and applied the Behaviour Change Wheel (BCW) framework [30] as a systematic approach to developing behavioural change interventions. A modified Delphi technique was adapted to further refine the intervention [31].

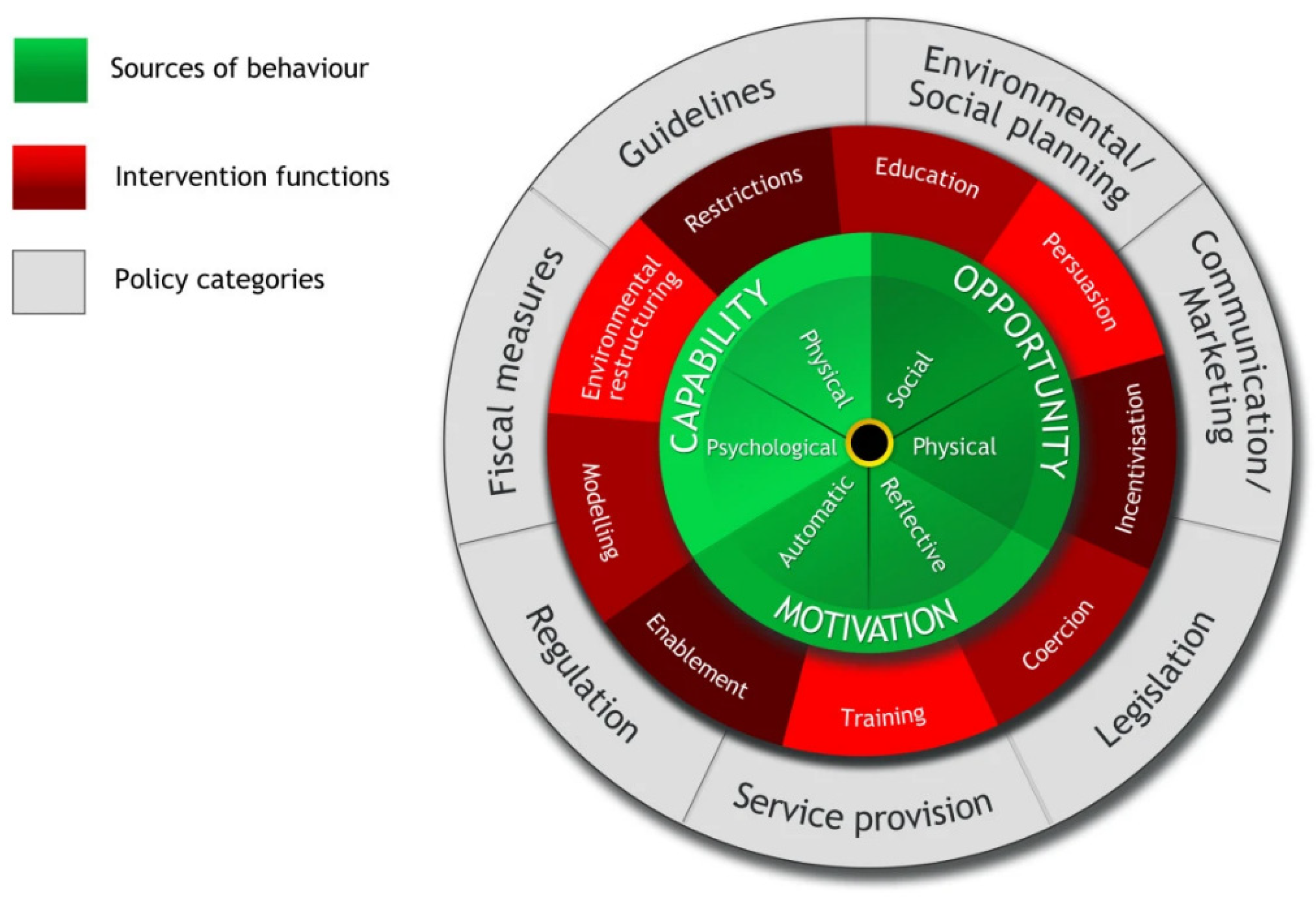

Behaviour Change Wheel: The BCW guide for designing interventions provides an evidence-based stepped approach to modifying behaviours, supporting intervention developers in considering various options and selecting only the most promising behaviours [32]. The BCW framework was developed from 19 frameworks of behaviour change identified in a systematic literature review [30]. As shown in

Figure 1, central to BCW are Capability, Opportunity and Motivation (COM-B) concepts, which are considered vital components that influence behavioural change [33]. The BCW allows for a systematic analysis and selection of an intervention, which may involve using one or more specific behaviour change techniques, to be effective in changing a particular target behaviour [34]. Surrounding the COM-B system are nine possible intervention functions that address capability, opportunity, or motivation deficits, such as education, persuasion, incentivisation, and coercion. The outer layer of the BCW includes seven policy categories aimed at supporting intervention functions [35,36].

Although the BCW framework has not been previously used to develop educational interventions for parents of children with disabilities in low-income settings, it has shown adaptability and versatility in other contexts. For example, BCW has been utilised to develop behavioural interventions related to dietary behaviour in Ireland [37], gestational diabetes in South Africa [38], healthy eating and active living among children and adolescents in Cameroon [39], and improving life jackets for drowning prevention among occupational boaters in Uganda [40].

Delphi Technique: The Delphi method is a structured communication technique for collecting and synthesising expert and stakeholder opinions and achieving consensus on a specific topic [41,42]. This method helps establish consensus among participants, select practical intervention priorities, and develop contextually relevant strategies [43].

1.2. Co-Design and Reporting Intervention Development Processes

Collaboration with a target population is fundamental for developing effective behavioural change interventions. There is a critical need for contextually informed, co-designed interventions to address the unique barriers faced by parents of children with disabilities in Malawi to ensure interventions that are relevant and meet the needs of the community it is intended to benefit. The term ‘co-design’ is frequently used interchangeably with co-production, co-creation, or co-development [44] and denotes the merging of design thinking, stakeholder experiences, scientific evidence, and participatory principles in the cooperative creation of community-specific solutions to community-specific issues [45].

Co-design can contribute to better recruitment, retention, and understanding of how change can be achieved (Murtagh et al., 2018). Co-design can also bridge the research-practice gap (Mallonee et al., 2006) created when evidence- -and theory-based interventions fail to translate into practice [29].

Although there have been advances in understanding and reporting on the feasibility, piloting, implementation, and evaluation of interventions [47], the stage of developing the intervention itself has received less attention [48]. Documenting the processes involved in developing theory-based interventions, especially those that actively engage target users as equal partners, is crucial for understanding how to design and implement solutions [29]. Comprehensive reporting can also guide future research and practice by providing valuable insights into developing and adapting interventions in similar contexts.

1.3. Aim and Objectives

This study describes the processes and methods used to co-design Tiyanjane, a theory-based and context-informed group intervention designed to promote parental involvement in supporting the education of children with disabilities in Malawi. The subsequent phase that will follow the co-design process of Tiyanjane will involve pilot implementation of the Tiyanjane intervention to assess its acceptability, feasibility and practical application in real-world settings. The pilot testing phase will assess participant recruitment and retention, as well acceptability and feasibility of the intervention in Malawi.

2. Materials and Methods

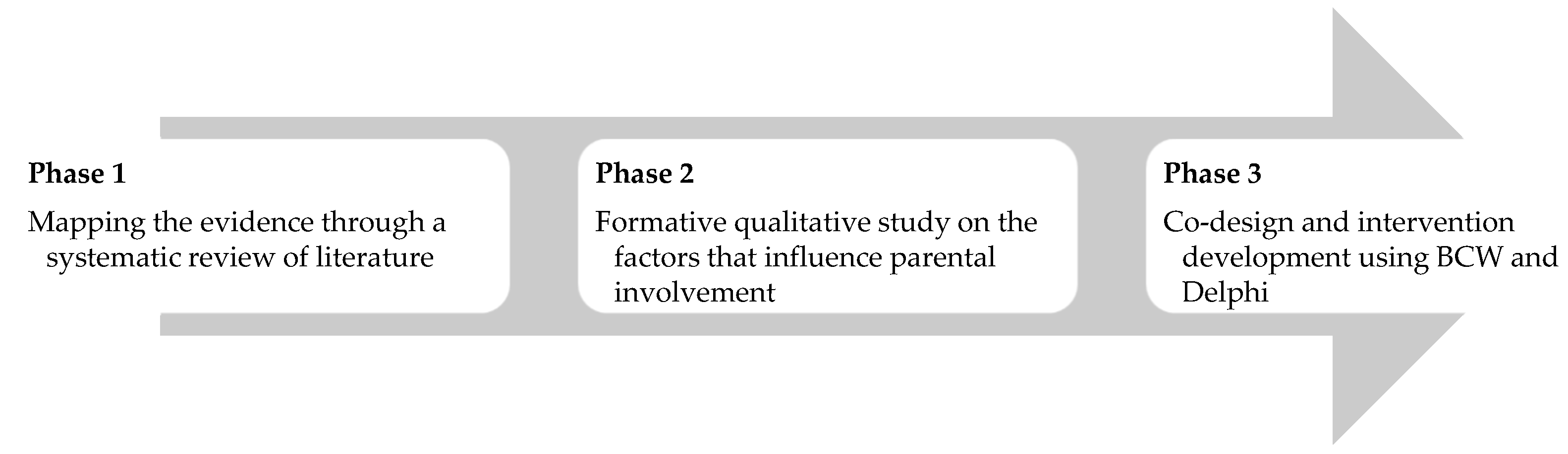

The study followed the MRC complex intervention guidelines to develop and test interventions [28]. We adhered to the GUIDED checklist to enhance the transparency and consistency of the intervention-development process [47] The intervention development followed several iterative phases, as illustrated in

Figure 2.

The initial study (Phase 1) involved a systematic literature review of interventions promoting parental involvement in the education of school-aged children with disabilities, as detailed in Musendo et al., 2023. The systematic review included peer-reviewed primary intervention studies published in English between 2000 and 2021, identified through searches of nine databases. The review identified 21 articles, with the majority (n=17) originating in high-income countries. The review highlighted a need for context-specific interventions in LMICs to address the challenges and barriers faced by families of children with disabilities in these settings.

The second study (Phase 2) was a formative qualitative study exploring the factors that impact parental engagement in educating children with disabilities in Malawi (Musendo et al., 2024). We utilised focus groups and in-depth interviews with 25 participants: teachers, parents, and children with disabilities in Nkhata Bay District, Malawi. Using the Capability-Opportunity-Motivation-Behaviour (COM-B) model for analysis, we found that while parents were willing and optimistic and primarily motivated about involvement, they faced constraints such as limited knowledge of their children’s learning needs, time, low confidence, and financial challenges. Limited support from schools and communities has hindered opportunities for involvement.

This paper focuses on the third phase (intervention development), which was informed by the systematic review outcomes and the formative qualitative study.

2.1. Study Design

This study employed a participatory co-design methodology incorporating the BCW framework and Delphi technique to guide the development of the intervention. The BCW framework provided a systematic approach to understanding and addressing behaviour change, while the Delphi technique assisted in facilitating stakeholder consensus and refining the intervention.

2.2. Setting

This study was conducted in a rural area in the Nkhata Bay district of Northern Malawi, characterised by a diverse economy encompassing agriculture, fishing, forestry, local commerce, industry, and tourism. Approximately 18% of this region’s population is considered ultra-poor [

8]. The District was selected in collaboration with local educational authorities and an Inclusive Education Project supported by the Church of Central Africa Presbyterian (CCAP), Malawi and Sense Scotland, UK. Additionally, the area was situated where the intervention would transition to CCAP’s education projects after completing a future pilot test phase.

A co-design workshop was held over three days at a local teacher development centre in the district. Afterwards, smaller follow-up consensus meetings were held: two were held online via Zoom, and two were held in-person in Malawi.

2.3. Participants and Recruitment

A total of 23 individuals participated in the co-design workshop in March 2023, with the majority being female (13 out of 23). Participants were purposively sampled to ensure diverse representations from people involved in the education of children with disabilities, i.e., parents, teachers, community leaders, government officials, NGOs, and disability organisations. Stakeholders were recruited through existing structures based on their experience of working with children or persons with disabilities in the education sector in the district. Of the 23 participants who participated in the co-design workshop, ten were chosen by the other participants to form a Core Development Group (CDG) tasked with finalising the development and refinement of the intervention. All the participants were aged ≥ 18 years, and they provided written informed consent to participate in the study. The sampled parents had children aged 12-14 with disabilities. The demographic characteristics of the participants are detailed in

Table 1.

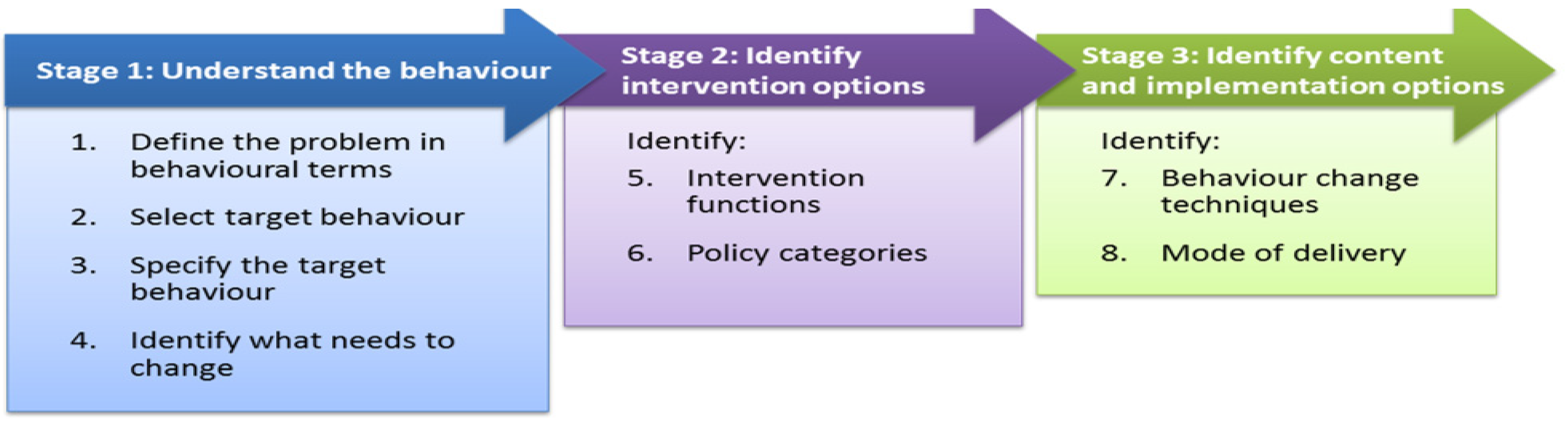

2.4. Intervention Development Overview

The intervention development process was structured into three stages: understanding behaviour, identifying intervention options, and determining content and implementation strategies (

Figure 3). DM led the workshops, while BC and BK moderated the small-group activities.

The workshop covered stages 1 and 2, following steps 1-6 of the BCW as described in

Figure 3. The third stage of identifying content and implementation options involved four subsequent meetings of the Core Development Group. During the workshops and consensus meetings, participants were engaged in structured activities, such as small-group discussions to identify key barriers, brainstorming sessions to generate ideas for intervention functions, and plenary sessions to prioritise intervention options. The process was iterative, allowing for the continuous refinement of ideas and ensuring that it was grounded in participants’ lived experiences and reflected the realities of their context. We actively employed a facilitative approach to manage and limit power dynamics and maximise participation and groups were organised to include participants of different backgrounds and experiences (parents, teachers, community leaders). Additionally, trained facilitators moderated discussions to ensure that all voices were heard, especially from those who might have been more hesitant to speak due to embedded social hierarchies.

2.4.1. Intervention Development Stage 1: Understanding Parental Behaviours

To address Step One of defining the problem in behavioural terms, small-group discussions explored three key questions: identifying the behaviours, the individuals involved in performing the behaviours, and the specific settings in which these behaviours occur. The moderators led small group discussions for individual idea generation, followed by plenary sessions to collectively present, analyse, and refine their ideas, agreeing on the behavioural aspects of the identified problem.

Step Two focused on identifying the target behaviours for the intervention. A ranking exercise, based on individual votes and group discussions, was used to select the target behaviours based on the following criteria [30]: (1) the potential impact of changing the behaviour; (2) the ease of changing the behaviour; (3) the importance and positive spillover effect that could result from changing the behaviour, and (4) the ease of measuring the behaviour.

In Step Three, the target behaviours were specified through collaborative discussions in category-specific groups, focusing on practical actions that could be implemented by different groups, such as parents, teachers and community leaders. The discussions allowed participants to collectively identify and reach a consensus on five questions recommended in the BCW: (1) Who needs to perform the behaviour? (2) What must they do to achieve the desired changes? (3) When do you need to do so? (4) Where will they do so? (5) How often do you do this?

In Step Four, workshop participants were encouraged to focus on identifying what needed to be changed to increase parental involvement in supporting their children’s education at both school and home. DM presented results from the formative study of the factors that influence parental involvement in educating children with disabilities in Malawi [49]. After the presentation, participants used their knowledge and experience to identify context-specific changes highlighted through the COM-B model (capability, opportunity, motivation, and behaviour). In the plenary, participants ranked issues from ‘very promising’ to ‘unacceptable,’ establishing priorities for intervention.

2.4.2. Intervention Development Stage 2: Identifying Intervention Options

In the second stage of the co-design process, the group worked on identifying the intervention functions that could best encourage parental participation in the identified target behaviours (Step Five). The facilitator introduced the seven intervention functions outlined in the BCW, and the participants discussed and translated them into the local language. The participants then formed small groups and used the APEASE criteria (i.e. acceptability, practicability, effectiveness/cost-effectiveness, affordability, safety/side effects, and equity criteria) [33] to prioritise the intervention functions. The group then discussed and agreed on preferred intervention functions according to their potential impact, ease of execution, and alignment with the community’s beliefs and resources.

Participatory activities and appropriately pitched communication/language facilitated the understanding and engagement of individuals of varied backgrounds and experiences in Step Six of BCW. We formed small groups, each led by trained moderators, to introduce policy categories using local examples that participants could relate to. For instance, “guidelines” were likened to rules or instructions given at home or school, and “communication/marketing” to sharing essential messages in the community. The moderators guided participants through a consensus-building process to determine the most appropriate policy categories for the intervention. The pros and cons of each policy category were discussed, considering factors such as ease of implementation and cultural relevance. After sharing their perspectives, the participants voted on their preferred policy category using coloured stickers (e.g. green for most preferred, yellow for neutral, and red for least preferred). The facilitator then tallied the votes and led a discussion to agree on the final results.

2.4.3. Intervention Development Stage 3: Identifying Content and Implementation Options

In the third stage, the Core Development Group met virtually and in person to discuss the intervention content (Step Seven) and identified potential delivery modes (Step 8), supported by the lead author and the facilitators. The objective was to identify specific behaviour-change techniques (BCTs) that should be incorporated into the intervention and optimise its effectiveness. However, we faced challenges regarding the technical language and translations used to describe behaviour change techniques. The Core Development Group found the process in Step Seven complex and not well-suited to the variable literacy levels of the participants. The group, therefore, agreed to utilise a modified version of the Delphi technique to address these challenges.

The Delphi approach involved multiple rounds of structured feedback from members of the Core Development Group. In the first round (virtual), participants verbally provided their opinions on potential intervention components and delivery methods. Responses were collected by the lead author, who summarised them, tallied the most commonly mentioned, and later shared them with each group. In the subsequent round, participants reviewed the summarised feedback, refined their opinions, and re-ranked the options by scoring 0 - 5. This iterative process was continued twice until a consensus was reached on ranking the intervention’s most feasible and practical components. The themes that emerged from the Delphi process were integrated with findings from the broader participatory design process to finalise the intervention components in the final meeting, which was held face-to-face.

During Step Eight, the Core Development Group engaged in a comprehensive discussion of the mode of delivery for the intervention components. The group explored options, such as face-to-face interactions or distance delivery. They also debated whether the intervention would target individuals, specific groups, or the entire group. Ultimately, the Core Development Group reached a consensus on the final intervention components, which was shared with an international advisory group of academic experts for their input.

3. Results

3.1. Understanding the Behaviour

Step One: The co-design workshop defined the problem as parents’ limited involvement and participation in the education of children with disabilities at home and in school.

Step Two: From a list of 27 potential behaviours, the participants identified and ranked four potential target behaviours based on the criteria listed in

Table 2. The potential target behaviours were: developing family action plans, conducting regular meetings, providing follow-up support, and facilitating training and information sharing.

Step Three: the core group focused on specifying the target behaviours for the intervention by addressing key practical questions on who needs to perform the behaviours, what needs to be done, when, where, and with whom? The target behaviours were further refined through collaborative discussions, as detailed in

Table 3. For example, parents were identified as responsible for developing and executing family action plans to support their children’s education, with specific actions to be taken at home and school. Similarly, the group highlighted the need for regular meetings between parents, teachers and community leaders to foster better communication and support.

Step Four: The final target behaviours deemed necessary to promote parental involvement in the education of children with disabilities, including who, what, when, where, and with whom they should be performed, are detailed in

Table 3. The activities needed collaborative efforts from different actors to ensure the approach is comprehensive and participatory. The participants collaborated to link the four key target behaviours with specific COM-B constructs, ensuring that the intervention would address the identified barriers. The outcomes of the discussions were as follows:

Developing and executing family action plans: Parents often deprioritise their children’s education because of challenges in daily life, workload and resource constraints. This barrier was related to the COM-B Construct of Reflective Motivation.

Conducting regular meetings and influencing activities: Limited opportunities for parents to engage with schools and a lack of confidence/skills to influence educational practices. These barriers were associated with the COM-B Constructs of Physical Opportunity and Psychological Capability.

Providing follow-up support activities at school and home: Parents needed to have accommodative social environments and support systems, hindering their ability to sustain their children’s education. This barrier was aligned with the COM-B Construct of Social Opportunity.

Facilitating training and information exchange: The lack of knowledge and motivation to support children with disabilities due to insufficient understanding of roles, children’s rights and disabilities. These barriers were associated with the COM-B Constructs of Psychological Capability and Automatic Motivation.

Table 4 summarises the behaviour analysis and the specific COM-B components that must be influenced for the intervention to be effective.

3.2. Stage 2: Identifying the Intervention Function Options (Steps 5-6)

In Step Five, the prioritisation process led to selecting five key intervention functions: education, environmental restructuring, enablement, persuasion, and training. These functions were considered the most suitable for helping parents, teachers, and community members support the education of children with disabilities. The selected functions were carefully aligned with criteria such as affordability, practicability, and equity, which were critical for ensuring the feasibility of the intervention. Incentivisation, modelling, and coercion were excluded because of concerns regarding affordability and sustainability.

In Step Six, three policy options were selected to support the intervention functions: Guidelines (developing and disseminating documents that provided evidence-based recommendations for action in response to specific situations), Communication or Marketing (encompassing correspondence, mass media and digital marketing campaigns); and Service provision (including materials and social resources). Following a participatory voting process, the participants unanimously agreed on “Tiyanjane,” a Chichewa word translated to “Let Us Unite”, highlighting the programme’s emphasis on collaboration among families, schools and the community.

3.3. Stage 3: Identifying Content and Implementation Options

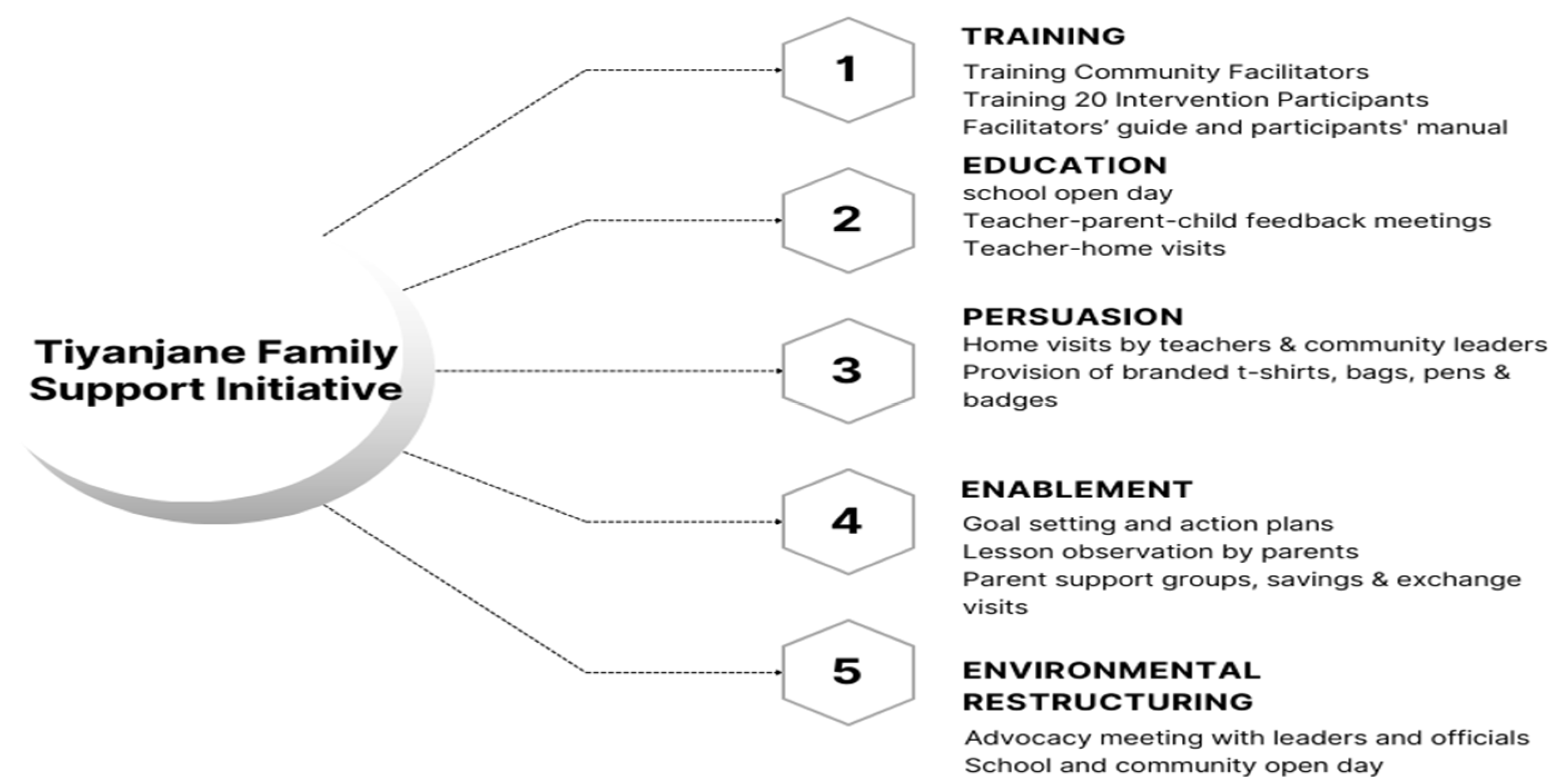

For Steps Seven and Eight, it was decided that Tiyanjane would be a multi-facet-comprehensive intervention to be implemented across various local contexts: homes, schools and community settings. The programme will involve parents, teachers and community members in collaborative, face-to-face group activities that seek to (a) educate parents, teachers and community leaders about disability issues and educational rights; (b) assist parents in setting goals and monitoring their children’s progress; and (c) creating a more inclusive environment for families of children with disabilities through community support and advocacy. The five intervention functions and activities to help achieve the expected results are illustrated in

Figure 4.

The main components of the intervention include training for facilitators and participants, ten practical sessions conducted over ten weeks, and the sharing of promotional resources such as homework books, activity-reporting diaries, t-shirts and branded bags (

Supplementary Material S1). The intervention is expected to (a) address capability by providing parents with the tools and knowledge necessary to support their children’s education; (b) enhance opportunities by creating structured interactions between parents, teachers, and community leaders; (c) ensure sustained motivation and opportunity through ongoing engagement with families; and (d) build capability by addressing the knowledge gaps between parents and community members.

4. Discussion

The method used to create Tiyanjane aimed to offer a comprehensive approach to promote parental involvement in supporting the education of children with disabilities. [50]. The programme includes facilitator and participant training, ten weekly practical sessions, and promotional resources to improve parents’ capability, create opportunities for structured interactions, sustain motivation, and address knowledge gaps. Tiyanjane emphasises working together through a participatory process to enhance the knowledge, skills, opportunities, and motivations of parents, teachers, and community members.

The BCW framework was instrumental in guiding the intervention development. However, the complexity of BCT taxonomy, coupled with issues such as language barriers, varying levels of literacy among participants, and technical terminology inherent in BCW, posed difficulties for some participants in stage 7 (selecting appropriate BCTs). To address these challenges, the Delphi technique was used to facilitate consensus among teams. Previous studies have similarly reported challenges in selecting the most appropriate intervention BCTs (Mallonee et al.2006; Truelove et al. 2020) and have combined BCW and Delphi in participatory intervention design(Erzse et al., 2022). In our case, integrating aspects of the Delphi technique was particularly useful for managing the complexity and adapting part of the BCW framework to the context. The Delphi method complements BCW by providing a flexible, iterative process that captures diverse perspectives(Barrett and Heale, 2020). By using multiple rounds of verbal feedback, the researchers refined the intervention components while ensuring that they were both culturally appropriate and aligned with the participants’ preferences and needs. Future research could investigate how this feedback method, in combination with other participatory techniques, might enhance the co-design of similar interventions.

Engaging stakeholders in co-designing Tiyanjane addresses the limitations of ‘traditional interventions’ by incorporating broader structural factors(Tucker & Schwartz, 2013). The co-design method successfully involved multiple stakeholders, acknowledged power dynamics, and promoted widespread participation. There is growing interest in progressing participatory co-design methods and incorporating them into community-based participatory research [39,53,54]. The co-design approach was inclusive, aiming to ensure that different voices, especially those of often marginalised individuals, such as parents of children with disabilities, were heard. Several other studies have also supported the importance of participatory methods in addressing power dynamics during intervention development and being sensitive to cultural and contextual elements within the study population [55,56].

This intervention development process has several strengths. We demonstrate a new application of the BCW framework and Delphi technique and expand the application of the BCW framework to new domains of disability and parental involvement to support children’s education in low-income settings. The development of Tiyanjane was grounded in formative research that has been identified as important in customising evidence-based programmes [57,58].: a systematic review of intervention literature and primary research that identified barriers and facilitators of parental involvement in Malawi.

Despite its valuable findings and insights, this study had limitations. The participants involved in the workshop and core group were purposefully sampled based on their roles as parents, teachers, or community leaders. Although this approach ensured that different stakeholders were included, we recognise that they were a highly motivated group of participants. Although the adapted Delphi technique helped establish a structured approach to consensus building, we acknowledge that its use virtually also posed challenges in the full engagement of all the participants. The method required more time and has been considered complex, with the potential to reach a consensus in an inherently subjective manner (Barrett & Heale, 2020). This study was conducted in a rural district in Malawi, which may limit the generalisability of the findings to other settings. It is important to note that although the Tiyanjane intervention was designed to be comprehensive and focus on several aspects, such as training, education, environmental restructuring, etc., it may not address all the barriers to parental involvement in the education of children with disabilities. For instance, systemic issues such as inadequate funding for special education, limited access to assistive devices, and broader societal attitudes towards disabilities are beyond the scope of this intervention. These factors could continue to impede progress, suggesting that while the intervention may lead to improvements, it is only one component of a broader strategy to address the complex challenges facing families of children with disabilities.

Our findings provide opportunities for future research. Pilot testing Tiyanjane in Malawi is required to assess its feasibility and acceptability, including evaluating the intervention’s acceptability among target users and identifying potential facilitators, barriers, and uncertainties in its implementation. Future research should also explore the adaptability of Tiyanjane to different cultural contexts; understanding the feasibility and effectiveness of the programme in diverse settings with varying cultural practices, resource levels, and educational systems is essential. Additionally, research should focus on evaluating the long-term impact and sustainability of the intervention, including how increased parental involvement can be maintained over time and what factors contribute to sustained engagement.

5. Conclusions

This study describes a co-design approach, to develop a culturally relevant parental involvement intervention that is supported by the community. The study also advances our understanding of how the BCW framework can be applied to low-income settings to systematically identify and address barriers to parental involvement in education.

Supplementary Materials

The following supporting information can be downloaded at the website of this paper posted on

Preprints.org. Description of the Tiyanjane Programme. Tiyanjane is an innovative programme to enhance parental involvement in the education of children with disabilities. The programme name, derived from the Chichewa language meaning “Let’s Unite”, symbolises the commitment to unifying families, teachers and community leaders in support of children with disabilities. The programme’s overarching goal was achieved through three main objectives: (1) educating parents, caregivers, teachers, and community leaders about disability issues, education rights, roles, and responsibilities; (2) assisting parents and caregivers in setting goals, planning, monitoring, and following their children’s progress; and (3) creating a more inclusive and supportive environment for families of children with disabilities by advocating increased community and stakeholder support. The programme includes 20-25 participants, including male and female caregivers of children with disabilities from 12 families, four teachers, and four community leaders within the programme’s catchment area. The 12-week program involved diverse families with children of different disabilities, ages, and gender representations. Participants engaged in-home visits, action planning, volunteering, fun family days, class observations, teacher-parent conferences, and community awareness events. While weekly activities can be consecutive, the programme is expected to start and be completed within three months, including school holidays. Promotional materials such as a homework booklet, Tiyanjane-branded t-shirts, carrier bags, and record books were developed to support the programme. Tiyanjane strives to create a more inclusive and supportive environment for families of children with disabilities by unifying the support of families, schools, and community members.

Funding

The authors acknowledge financial support from the LSHTM’s Travel Scholarship grant and Sense Scotland to cover travel expenses to Malawi during the intervention development phase.

Researcher Characteristics and Reflexivity

The lead author (DM)’s unique position and perspective enriched the methodological approach. A Zimbabwean doctoral student at the LSHTM with extensive working experience in Malawi, DM combined academic rigour with personal cultural familiarity to provide a nuanced understanding of the local context and to ensure the integrity of the studies. This dual role enabled a better understanding of the local context and the application of rigorous academic research methods. However, his external affiliation could have influenced the participants’ responses or led to bias in interpreting local realities. To mitigate such risks, the lead author worked closely with male and female Malawian researchers, supported by local NGO staff and education officials. This helped accommodate diverse viewpoints and provided grounded insights. Balancing these strengths and limitations is essential for authentic and respectful representation of the community’s experiences.

Institutional Review Board Statement

This study was conducted in accordance with the Declaration of Helsinki and approved by the Ethics Committees of the University of Livingstonia, Malawi (Ref. no. UNILIA- REC/3//JDM/2019) on March 19, 2019, and LSHTM (ref. no. 16239), on 2 May 2019.

Informed Consent Statement

Informed consent was obtained from all the participants involved in the study.

Data Availability Statement

The original contributions of this study are included in this article. Further studies should be directed towards the corresponding authors.

Acknowledgments

The authors are grateful to the teachers, parents, and children with disabilities who generously contributed to this study. Special thanks are extended to the following individuals for their support as part of the research team: Blessing Chirwa, Chisomo Kamata, and Sarah Chipeta, as well as to CCAP Project members Atupele Nampota, Martha Chirwa, and Atusaye Kyumba. Additionally, we would like to recognise Karen Goodman-Jones, a representative of Sense Scotland, as well as, Jane Wilber, Maria Zuurmond, and Femke Bannink Mbazzi for all the advisory support. Furthermore, we acknowledge using Grammarly for spelling, grammar and manuscript proofreading.

Conflicts of Interest

The authors declare no conflicts of interest.

References

- D. J. Musendo et al., “A Systematic Review of Interventions Promoting Parental Involvement in the Education of School-Aged Children With Disabilities,” Dec. 01, 2023, Cambridge University Press. [CrossRef]

- S. E. Goldman and M. M. Burke, “The Effectiveness of Interventions to Increase Parent Involvement in Special Education: A Systematic Literature Review and Meta-Analysis,” Apr. 03, 2017, Routledge. [CrossRef]

- J. L. Epstein, “School, family and community partnerships: Preparing educators and improving schools,” School, Family, and Community Partnerships: Preparing Educators and Improving Schools, Second Edition, pp. 1–634, Jan. 2018.

- W. H. Jeynes, “The Relationship Between Parental Involvement and Urban Secondary School Student Academic Achievement: A Meta-Analysis,” http://dx.doi.org/10.1177/0042085906293818, vol. 42, no. 1, pp. 82–110, Aug. 2016. [CrossRef]

- S. Bariroh, “The Influence of Parents’ Involvement on Children with Special Needs’ Motivation and Learning Achievement,” International Education Studies, vol. 11, no. 4, 2018. [CrossRef]

- J. Jafarov, “Factors Affecting Parental Involvement in Education: The Analysis of Literature,” Khazar Journal of Humanities and Social Sciences, vol. 18, no. 4, pp. 35–44, Dec. 2015. [CrossRef]

- J. Oranga, E. Obuba, I. Sore, F. Boinett, and J. Oranga, “Parental Involvement in the Education of Learners with Intellectual Disabilities in Kenya,” Journal 2022, vol. 9, p. 8542, 2022. [CrossRef]

- National Statistics Office, “2018 Malawi Population,” 2019. Accessed: Feb. 15, 2022. [Online]. Available online: http://www.nsomalawi.mw/images/stories/data_on_line/demography/census_2018/2018%20Malawi%20Population%20and%20Housing%20Census%20Main%20Report.pdf.

- UNICEF, “A Situation Analysis of Children with Disabilities in Malawi,” 2020.

- F. Nelson, C. Masulani-Mwale, E. Richards, S. Theobald, and M. Gladstone, “The meaning of participation for children in Malawi: insights from children and caregivers,” Child Care Health Dev, vol. 43, no. 1, pp. 133–143, 2017. [CrossRef]

- J. Njelesani, C. Cameron, D. Njelesani, M. Jamali, J. J. D. Andrion, and A. Munthali, “Recognizing the rights of children with disabilities in Malawi,” Disabil Soc, 2024. [CrossRef]

- C. Masulani-Mwale, D. Mathanga, F. Kauye, and M. Gladstone, “Psychosocial interventions for parents of children with intellectual disabilities–A narrative review and implications for low income settings,” Ment Health Prev, vol. 11, no. June, pp. 24–32, 2018. [CrossRef]

- L. Idrissa, “Educating Children With Disabilities In Malawi,” SSRN Electronic Journal, Nov. 2022. [CrossRef]

- L. M. Banks, X. Hunt, K. Kalua, P. Nindi, M. Zuurmond, and T. Shakespeare, “‘I might be lucky and go back to school’: Factors affecting inclusion in education for children with disabilities in rural Malawi,” Afr J Disabil, vol. 11, 2022. [CrossRef]

- L. M. Banks, H. Kuper, and S. Polack, “Poverty and disability in low- and middle-income countries: A systematic review,” PLoS One, vol. 12, no. 12, p. e0189996, Dec. 2017. [CrossRef]

- H. Kuper et al., “Rapid Evidence Assessment (REA) of What Works to Improve Educational Outcomes for People with Disabilities in Low-and Middle-Income Countries,” 2018.

- M. Gedfie and D. Negassa, “Parental Involvement in the Education of their Children with Disabilities: the case of Primary Schools of Bahir Dar City Administration, Ethiopia,” East African Journal of Social Sciences and Humanities, vol. 3, no. 2, pp. 43–56, Dec. 2018, Accessed: Mar. 27, 2023. [Online]. Available: https://www.haramayajournals.org/index.

- A. Harris and J. Goodall, “Do parents know they matter? Engaging all parents in learning,” Educational Research, vol. 50, no. 3, pp. 277–289, 2008. [CrossRef]

- E. E. Mantey, “Parental Involvement: A Response to Children with Disability’s Education,” African Research Review, vol. 14, no. 1, pp. 27–39, Apr. 2020. [CrossRef]

- K. Aruldas et al., “‘If he has education, there will not be any problem’: Factors affecting access to education for children with disabilities in Tamil Nadu, India,” PLoS One, vol. 18, no. 8, Aug. 2023. [CrossRef]

- C. He, N. Evans, H. Graham, and K. Milner, “Group-based caregiver support interventions for children living with disabilities in low-and-middle-income countries: Narrative review and analysis of content, outcomes, and implementation factors,” J Glob Health, vol. 14, 2024. [CrossRef]

- T. Smythe, V. Reichenberger, E. M. Pinzón, I. C. Hurtado, L. Rubiano, and H. Kuper, “The feasibility of establishing parent support groups for children with congenital Zika syndrome and their families: a mixed-methods study,” Wellcome Open Res, vol. 6, 2023. [CrossRef]

- M. Zuurmond et al., “Evaluating the impact of a community-based parent training programme for children with cerebral palsy in Ghana,” PLoS One, vol. 13, no. 9, Sep. 2018. [CrossRef]

- R. Nalugya et al., “Obuntu bulamu: Parental peer-to-peer support for inclusion of children with disabilities in Central Uganda,” Afr J Disabil, vol. 12, 2023. [CrossRef]

- F. B. Mbazzi et al., “‘Obuntu Bulamu’ – Development and Testing of an Indigenous Intervention for Disability Inclusion in Uganda,” Scandinavian Journal of Disability Research, vol. 22, no. 1, pp. 403–416, 2020. [CrossRef]

- F. Barker, L. Atkins, and S. de Lusignan, “Applying the COM-B behaviour model and behaviour change wheel to develop an intervention to improve hearing-aid use in adult auditory rehabilitation,” Int J Audiol, vol. 55, no. March, pp. S90–S98, 2016. [CrossRef]

- R. Crosnoe and A. C. Huston, “Socioeconomic Status, Schooling, and the Developmental Trajectories of Adolescents,” Dev Psychol, vol. 43, no. 5, pp. 1097–1110, Sep. 2007. [CrossRef]

- P. Craig, P. Dieppe, S. Macintyre, S. Michie, I. Nazareth, and M. Petticrew, “Developing and evaluating complex interventions: the new Medical Research Council guidance,” BMJ, vol. 337, no. 7676, pp. 979–983, Sep. 2008. [CrossRef]

- A. V. Creaser, D. D. A. V. Creaser, D. D. Bingham, H. A. J. Bennett, S. Costa, and S. A. Clemes, “The development of a family-based wearable intervention using behaviour change and co-design approaches: move and connect,” Public Health, vol. 217, pp. 54–64, Apr. 2023. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- S. Michie, M. M. van Stralen, and R. West, “The behaviour change wheel: A new method for characterising and designing behaviour change interventions,” Implementation Science, vol. 6, no. 1, pp. 1–12, Apr. 2011. [CrossRef]

- D. Barrett and R. Heale, “What are Delphi studies?,” Evid Based Nurs, vol. 23, no. 3, pp. 68–69, Jul. 2020. [CrossRef]

- J. Webb, J. Foster, and E. Poulter, “Increasing the frequency of physical activity very brief advice for cancer patients. Development of an intervention using the behaviour change wheel,” Public Health, vol. 133, pp. 45–56, Apr. 2016. [CrossRef]

- L. Atkins and S. Michie, “Designing interventions to change eating behaviours,” Proc Nutr Soc, vol. 74, no. 2, pp. 164–170, May 2015. [CrossRef]

- H. Reid et al., “Use of the behaviour change wheel to improve everyday person-centred conversations on physical activity across healthcare,” BMC Public Health, vol. 22, no. 1, Dec. 2022. [CrossRef]

- R. Davis, R. Campbell, Z. Hildon, L. Hobbs, and S. Michie, “Theories of behaviour and behaviour change across the social and behavioural sciences: a scoping review,” Health Psychol Rev, vol. 9, no. 3, p. 323, Aug. 2015. [CrossRef]

- K. W. Davidson and U. Scholz, “Understanding and Predicting Health Behaviour Change: A Contemporary View Through the Lenses of Meta-Reviews,” Health Psychol Rev, vol. 14, no. 1, p. 1, Jan. 2020. [CrossRef]

- C. T. McEvoy et al., “Development of a peer support intervention to encourage dietary behaviour change towards a Mediterranean diet in adults at high cardiovascular risk,” BMC Public Health, vol. 18, no. 1, pp. 1–13, 2018. [CrossRef]

- K. Murphy et al., “Using the COM-B model and Behaviour Change Wheel to develop a theory and evidence-based intervention for women with gestational diabetes (IINDIAGO),” BMC Public Health, vol. 23, no. 1, Dec. 2023. [CrossRef]

- A. Erzse et al., “A Mixed-Methods Participatory Intervention Design Process to Develop Intervention Options in Immediate Food and Built Environments to Support Healthy Eating and Active Living among Children and Adolescents in Cameroon and South Africa,” Int J Environ Res Public Health, vol. 19, no. 16, p. 10263, Aug. 2022. [CrossRef]

- F. Oporia et al., “Development and validation of an intervention package to improve lifejacket wear for drowning prevention among occupational boaters on Lake Albert, Uganda,” Injury Prevention, vol. 29, no. 6, pp. 493–499, Dec. 2023. [CrossRef]

- E. G. Flaherty et al., “Adverse childhood experiences and child health in early adolescence,” JAMA Pediatr, vol. 167, no. 7, pp. 622–629, Jul. 2013. [CrossRef]

- B. W. Sahle, N. J. Reavley, A. J. Morgan, M. B. H. Yap, A. Reupert, and A. F. Jorm, “A Delphi study to identify intervention priorities to prevent the occurrence and reduce the impact of adverse childhood experiences,” Australian and New Zealand Journal of Psychiatry, vol. 56, no. 6, pp. 686–694, Jun. 2022. [CrossRef]

- A. F. Jorm, “Using the Delphi expert consensus method in mental health research,” Aust N Z J Psychiatry, vol. 49, no. 10, pp. 887–897, Oct. 2015. [CrossRef]

- W. H. Voorberg, V. J. J. M. Bekkers, and L. G. Tummers, “A Systematic Review of Co-Creation and Co-Production: Embarking on the social innovation journey,” Public Management Review, vol. 17, no. 9, pp. 1333–1357, Oct. 2015. [CrossRef]

- L. Andren, D. Papp, E. Penno, and A. Vallas, “Co-design As Collaborative Research,” Eesti Teadusliku Seltsi Rootsis: Aastaraamat. Annales Societatis Litterarum Estonicae in Svecia, vol. 11, p. 216;ill., Sep. 2018, Accessed: Sep. 13, 2024. [Online]. Available online: https://connected-communities.org/wp-content/uploads/2018/07/Co-Design_SP.pdf.

- E. M. Murtagh, A. T. Barnes, J. McMullen, and P. J. Morgan, “Mothers and teenage daughters walking to health: using the behaviour change wheel to develop an intervention to improve adolescent girls’ physical activity,” Public Health, vol. 158, pp. 37–46, May 2018. [CrossRef]

- E. Duncan et al., “Guidance for reporting intervention development studies in health research (GUIDED): an evidence-based consensus study,” BMJ Open, vol. 10, no. 4, p. e033516, Apr. 2020. [CrossRef]

- P. Hoddinott, “A new era for intervention development studies,” 2015. [CrossRef]

- D. J. Musendo, M. Zuurmond, T. Nkhonjera, S. Polack, and D. Patel, “‘It Is My Responsibility to Escort My Child to School …’ Factors Influencing Parental Involvement in Educating Children with Disabilities in Malawi,” Aug. 2024. [CrossRef]

- V. Tucker and I. Schwartz, “Parents’ Perspectives of Collaboration with School Professionals: Barriers and Facilitators to Successful Partnerships in Planning for Students with ASD,” School Ment Health, vol. 5, no. 1, pp. 3–14, 2013. [CrossRef]

- S. Mallonee, C. Fowler, and G. R. Istre, “Bridging the gap between research and practice: a continuing challenge,” Injury Prevention, vol. 12, no. 6, pp. 357–359, Dec. 2006. [CrossRef]

- S. Truelove, L. M. Vanderloo, P. Tucker, K. M. Di Sebastiano, and G. Faulkner, “The use of the behaviour change wheel in the development of ParticipACTION’s physical activity app,” Prev Med Rep, vol. 20, Dec. 2020. [CrossRef]

- F. Cornish et al., “Participatory action research,” Nature Reviews Methods Primers 2023 3:1, vol. 3, no. 1, pp. 1–14, Apr. 2023. [CrossRef]

- V. Haldane et al., “Community participation in health services development, implementation, and evaluation: A systematic review of empowerment, health, community, and process outcomes,” 2019. [CrossRef]

- L. M. Pfadenhauer et al., “Making sense of complexity in context and implementation: The Context and Implementation of Complex Interventions (CICI) framework,” Implementation Science, vol. 12, no. 1, pp. 1–17, Feb. 2017. [CrossRef]

- L. Yardley, L. Morrison, K. Bradbury, and I. Muller, “The Person-Based Approach to Intervention Development: Application to Digital Health-Related Behavior Change Interventions,” J Med Internet Res, vol. 17, no. 1, p. e30, Jan. 2015. [CrossRef]

- A. Pleasant, C. O’Leary, and R. H. Carmona, “Using formative research to tailor a community intervention focused on the prevention of chronic disease,” Eval Program Plann, vol. 78, p. 101716, Feb. 2020. [CrossRef]

- H. Moosapour, F. Saeidifard, M. Aalaa, A. Soltani, and B. Larijani, “The rationale behind systematic reviews in clinical medicine: a conceptual framework,” J Diabetes Metab Disord, vol. 20, no. 1, p. 919, Jun. 2021. [CrossRef]

|

Disclaimer/Publisher’s Note: The statements, opinions and data contained in all publications are solely those of the individual author(s) and contributor(s) and not of MDPI and/or the editor(s). MDPI and/or the editor(s) disclaim responsibility for any injury to people or property resulting from any ideas, methods, instructions or products referred to in the content. |

© 2024 by the authors. Licensee MDPI, Basel, Switzerland. This article is an open access article distributed under the terms and conditions of the Creative Commons Attribution (CC BY) license (https://creativecommons.org/licenses/by/4.0/).