1. Introduction

The advancement of quantum technologies depends crucially on the ability to generate and control quantum resources in a reliable and scalable way [

1,

2]. Among these resources, quantum entanglement stands out as a fundamental ingredient, enabling powerful protocols to operate within the limits of local operations and classical communication (LOCC) [

2]. Entangled states are at the heart of key quantum information processing tasks, such as teleportation [

3], sensing [

4], and communication [

5,

6]. In particular, maximally entangled states, such as Bell pairs (EPR states), are essential building blocks for these applications [

7].

Although significant advances have been made in generating entanglement with photonic systems [

8,

9], scalable solid-state quantum processors require architectures that can produce and distribute entanglement on demand, integrated directly with quantum registers [

10]. Spin chains have thus emerged as promising candidates for short-range quantum communication and entanglement distribution [

11,

12,

13], due to their tunability and compatibility with solid-state platforms. Physical implementations span electron spins in quantum dots [

14], magnetic molecules [

15], and endohedral fullerenes [

16], making spin chains attractive as modular elements for scalable quantum devices.

There is an extensive body of work exploring spin chains for quantum state transfer [

11,

17,

18], entanglement routing [

19,

20,

21], and quantum bus architectures [

22,

23,

24,

25,

26,

27,

28]. However, much of this research focuses on idealized spin-

models and often overlooks practical challenges such as disorder and decoherence. Additionally, the performance of higher-spin chains and comparisons between different entanglement generation schemes remain largely unexplored. We address these gaps by comparing two entanglement generation protocols based on XY-type spin chains: Protocol 1 (P1), where alternating weak and strong couplings guide quantum correlations toward the chain edges [

23,

25,

29,

30,

31], and Protocol 2 (P2), which employs symmetric perturbative couplings at both ends to enhance transport speed and facilitate the buildup of quantum correlations [

32,

33,

34]. Using the XXZ spin model, we systematically investigated the entanglement dynamics for spins

, 1, and

under both ideal and noisy conditions. Our analysis is primarily based on extensive numerical simulations. We quantify entanglement using the negativity measure, explicitly including the effects of static disorder — both diagonal and off-diagonal — as well as local decoherence channels within the model. Although effective Hamiltonians are derived to elucidate the underlying physical mechanisms, our main conclusions are based entirely on the numerical data. Importantly, we observe that the dual-port databus protocol (P2) enables faster and more robust entanglement generation compared to the staggered (P1) scheme, especially in the presence of environmental noise and fabrication imperfections. To demonstrate practical applicability, we benchmark the entangling times and parameter regimes against those accessible in the current solid-state platforms. Our results are relevant to a variety of systems—including trapped ions [

35], superconducting qubit arrays [

36], nitrogen-vacancy centers in diamond [

37], and quantum dot devices [

38] — where engineered spin-spin interactions and coherent control has been experimentally realized. This work thus paves the way for deterministic and scalable entanglement sources in next-generation quantum processors and networks.

2. Model and Methods

We model the system as an

N-site XX spin chain with Hamiltonian:

where

are spin-

s operators and

are local magnetic fields. The coupling constants

alternate between two values,

and

, depending on the position in the chain (see

Figure 1).

The system evolves under the Lindblad master equation [

39,

40,

41], which describes the combined unitary and dissipative dynamics:

The dissipative term proportional to

introduces local pure dephasing, a common and critical source of decoherence in quantum systems. This type of noise models the loss of quantum coherence without energy exchange with the environment and is particularly relevant in platforms such as superconducting qubits [

36,

42,

43,

44], trapped ions [

45], and ultracold atom simulators of spin chains [

46,

47]. In such systems, fluctuations in the local environment or control parameters often lead to dephasing noise that dominates other dissipative processes. Although we set

unless otherwise stated to focus on the coherent dynamics, we also consider finite

to assess the robustness of quantum correlations under realistic conditions.

We assess entanglement between the chain ends via the negativity [

48,

49,

50], defined as:

where

is the partial transpose of the quantum state

with respect to subsystem A, and

denotes the trace norm or the sum of the singular values of the operator

. Alternatively, negativity can be calculated as

, where

are the eigenvalues of the partially transposed density matrix

. The maximum attainable value of

is constrained by the dimensionality of the Hilbert space, which depends on the spin magnitude

s. Because we work across different dimensionality systems, we normalize our negativity calculations relative to the theoretical maximum for the specific spin value

s, corresponding to the negativity of a maximally entangled state in the relevant Hilbert space.

To assess whether the protocols generate a Bell state when the maximal possible negativity

is achieved, we compute fidelity [

51]

where

is the density matrix of the generated state and

is the density matrix associated with the target state. A fidelity of

indicates perfect preparation of the target state, while values below unity quantify the deviation from that.

2.1. Entanglement Generation Protocols

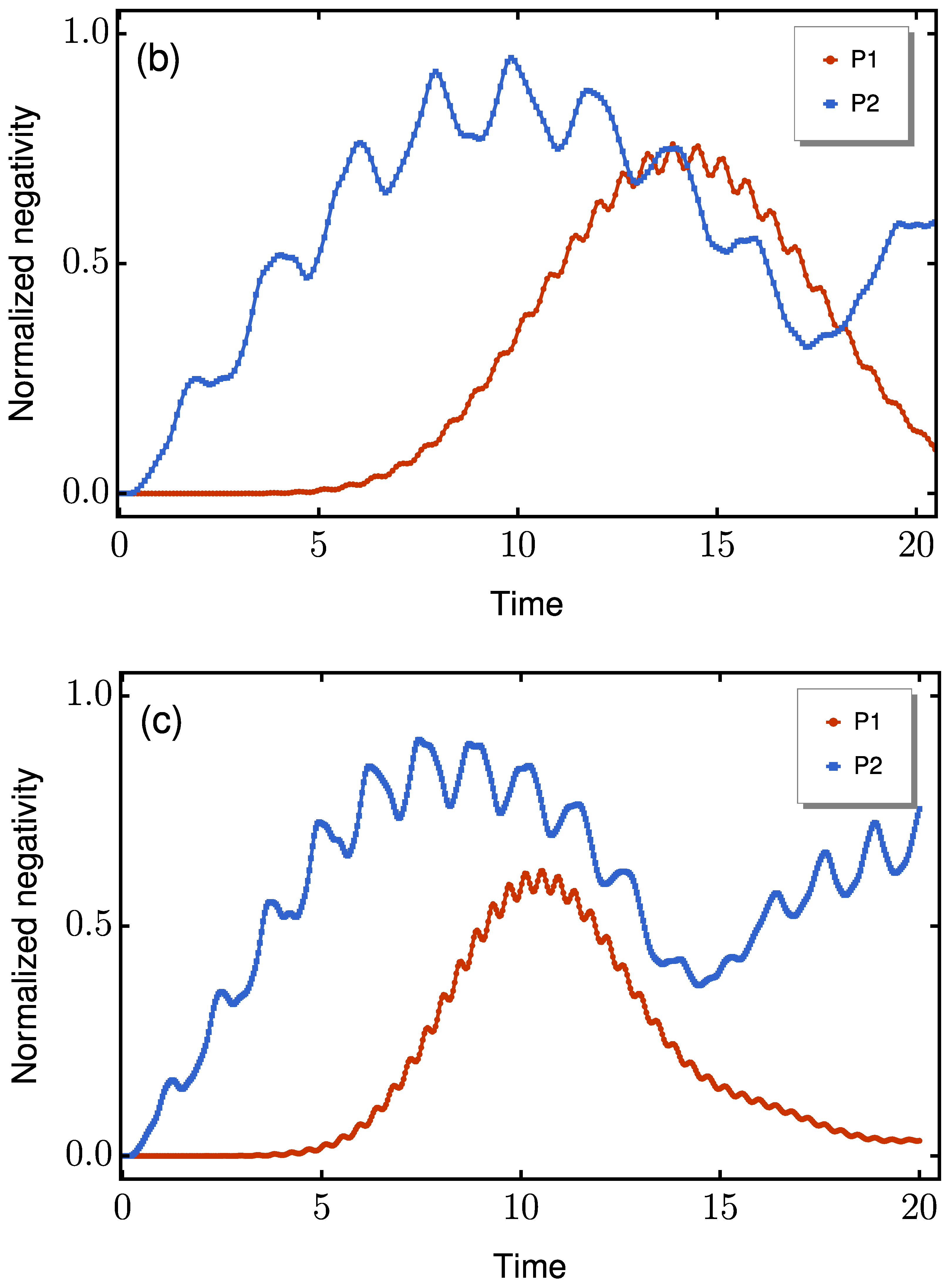

We investigated two different entanglement generation protocols, illustrated in

Figure 1, both designed to mediate long-range entanglement between boundary spins in a finite chain. Unlike traditional quantum communication setups focused on state transfer fidelity, our objective here is the efficient and robust creation of quantum correlations, specifically entanglement, between distant parties.

The P1 employs a staggered spin chain initialized in the state

Moreover, it evolves unitarily under the system Hamiltonian with . In this configuration, the boundary spins A and C are initially excited, while the intermediate sites are prepared in their ground states. Entanglement dynamics, in this case, arise from coherent exchange interactions distributed across the entire chain.

For P2, the chain is initialized in the state

but here, a single excitation is localized at the sender site, while all other spins — including the receiver at the opposite end — begin in their ground states. A zero magnetic field

is applied in the bulk while carefully engineered

optimized boundary magnetic fields are applied at the extremities to enhance the coherent buildup of long-range entanglement.

A central advantage of P2 is that the bulk (spins 2 through ) remains largely unpopulated during evolution. That is, the intermediate spins undergo only virtual excitation, which avoids a significant population of the bulk and enables the boundary spins to interact effectively as if they were directly coupled. This virtual coupling mechanism reduces the influence of imperfections within the chain, such as diagonal and off-diagonal disorder or local dephasing, thereby supporting the robust generation of entanglement between sender and receiver.

Although structurally reminiscent of state transfer protocols, the goal here is not to maximize transfer fidelity but to exploit coherent dynamics for the fast and resilient generation of entanglement. This distinction is central to our investigation, and we provide detailed numerical results in the following section to validate the effectiveness of both protocols under various conditions. In particular, we systematically compare their performance across different spin magnitudes, analyze their resilience to disorder, and decoherence, and explore how the introduction of site-dependent magnetic fields () affects entanglement generation.

The analysis reveals that P2 offers three key advantages over P1: (i) it achieves maximal entanglement between boundary spins on shorter timescales, with this effect being particularly pronounced in the spin- case; (ii) it demonstrates enhanced robustness against both diagonal and off-diagonal disorder, as well as dephasing noise; and (iii) it maintains high entanglement generation efficiency even in higher-spin systems (, and ), where the P1 shows reduced effectiveness.

These benefits stem from the engineered boundary control and the architecture’s ability to harness virtual excitations for indirect but coherent boundary coupling, effectively bypassing the detrimental effects of bulk-mediated decoherence. The validity of these claims and the quantitative characterization of these mechanisms will be fully explored in the next section.

3. Results

3.1. Benchmark without noise: dynamics in pristine chains

To establish a baseline, we first compare the coherent dynamics of the two architectures in the absence of disorder or decoherence for

. Figure shows the time evolution of the end-to-end negativity for spin magnitudes

, 1, and

. The results demonstrate that P2 reaches its first entanglement maximum significantly faster than P1 while maintaining robust performance across different spin dimensions. The quantitative data extracted from these curves are presented in

Table 1.

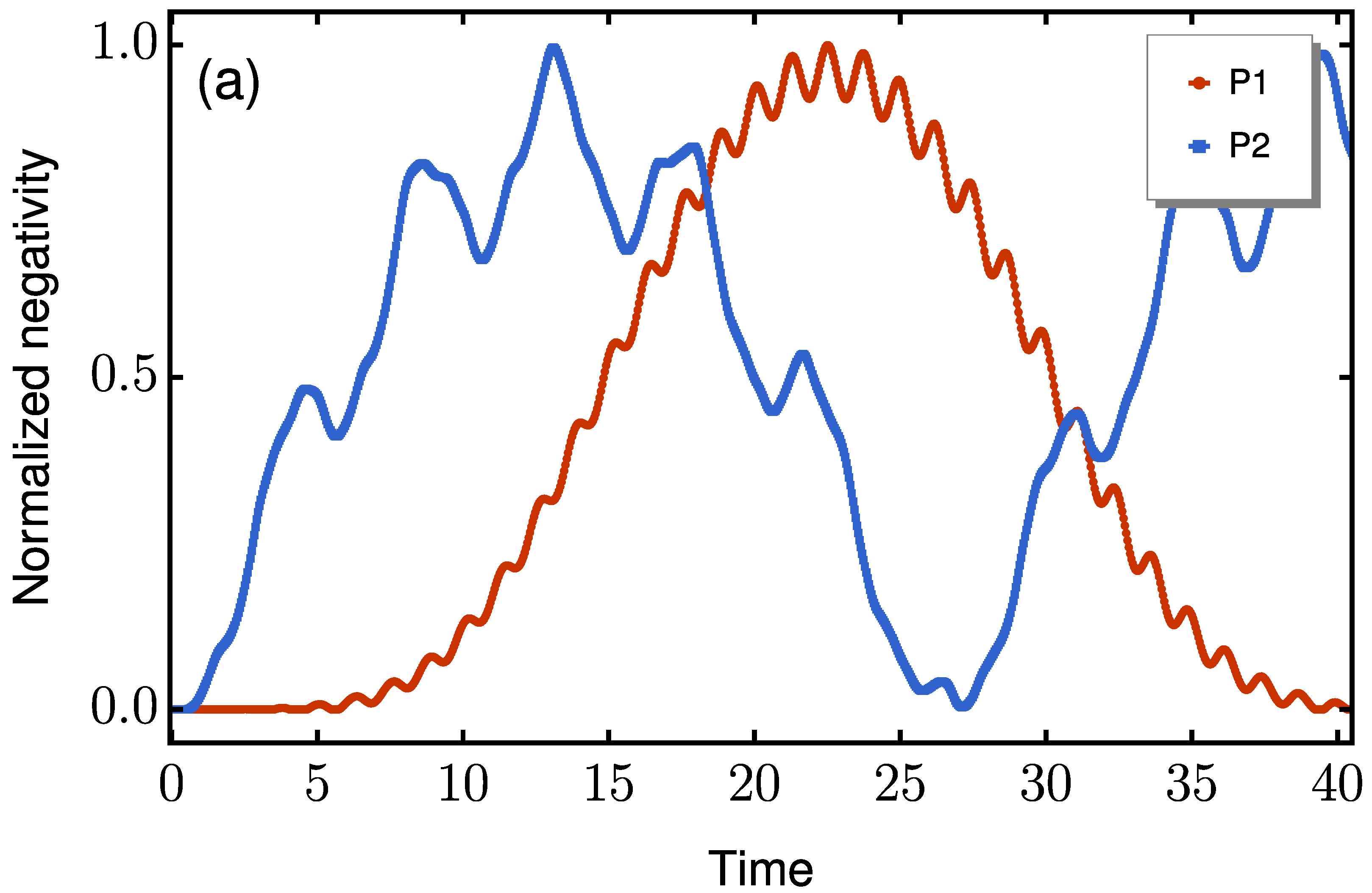

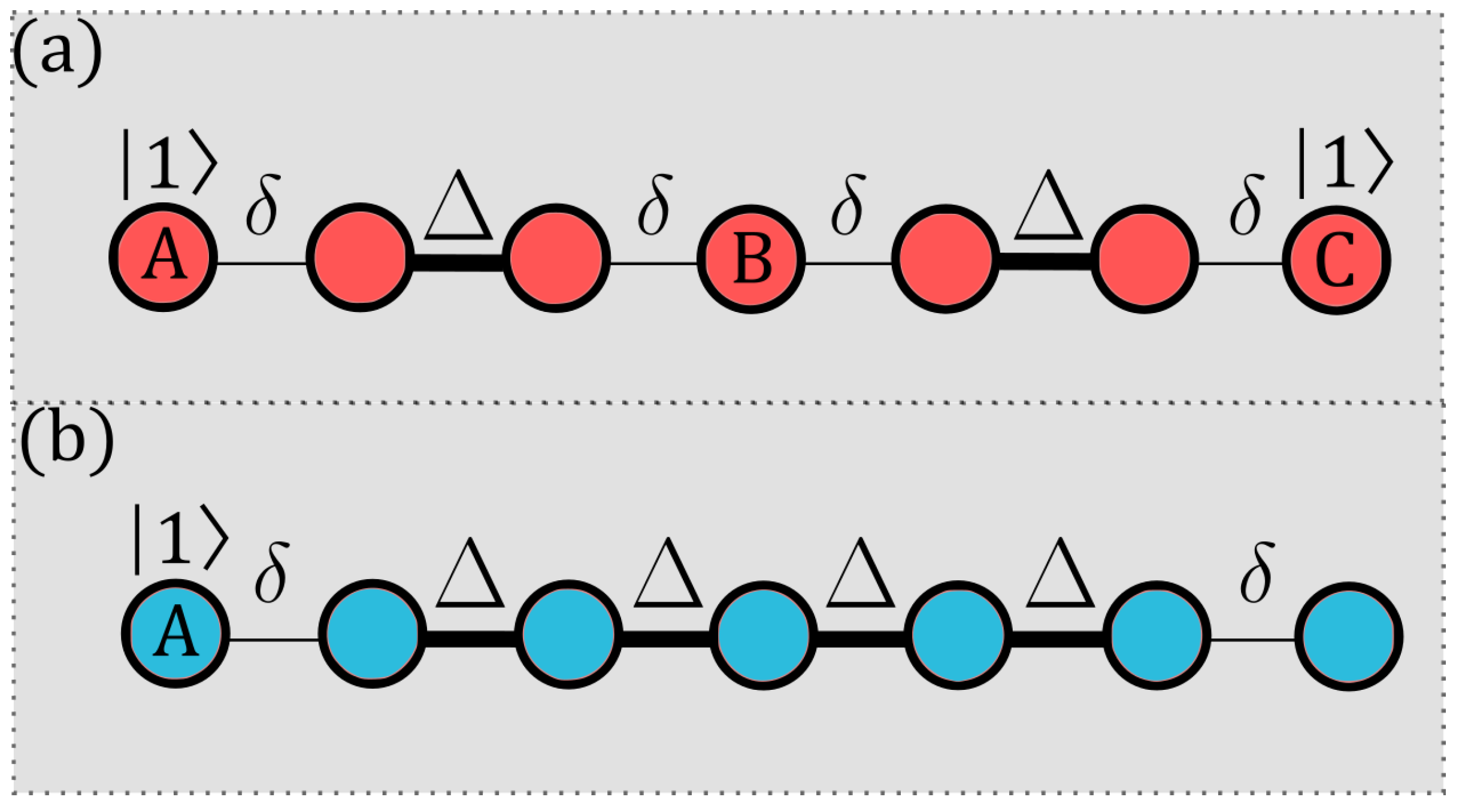

Figure 2.

Time evolution of the end-to-end negativity for (a) , (b) , and (c) . All traces correspond to the same dimerization ratio . Results are shown for P1 (red curves) and P2 (blue curves).

Figure 2.

Time evolution of the end-to-end negativity for (a) , (b) , and (c) . All traces correspond to the same dimerization ratio . Results are shown for P1 (red curves) and P2 (blue curves).

In all cases, P2 exhibits faster entanglement generation and consistently achieves higher negativity values. In particular, for

, both protocols output the Bell state

when maximally entangled, though P2 requires a local

rotation to be applied on the

z-axis of the qubit at site

N, via application of the

gate. The fidelity dynamics concerning the target state

is shown in

Figure 3, where the necessary rotation for P2 has already been applied before the fidelity calculation.

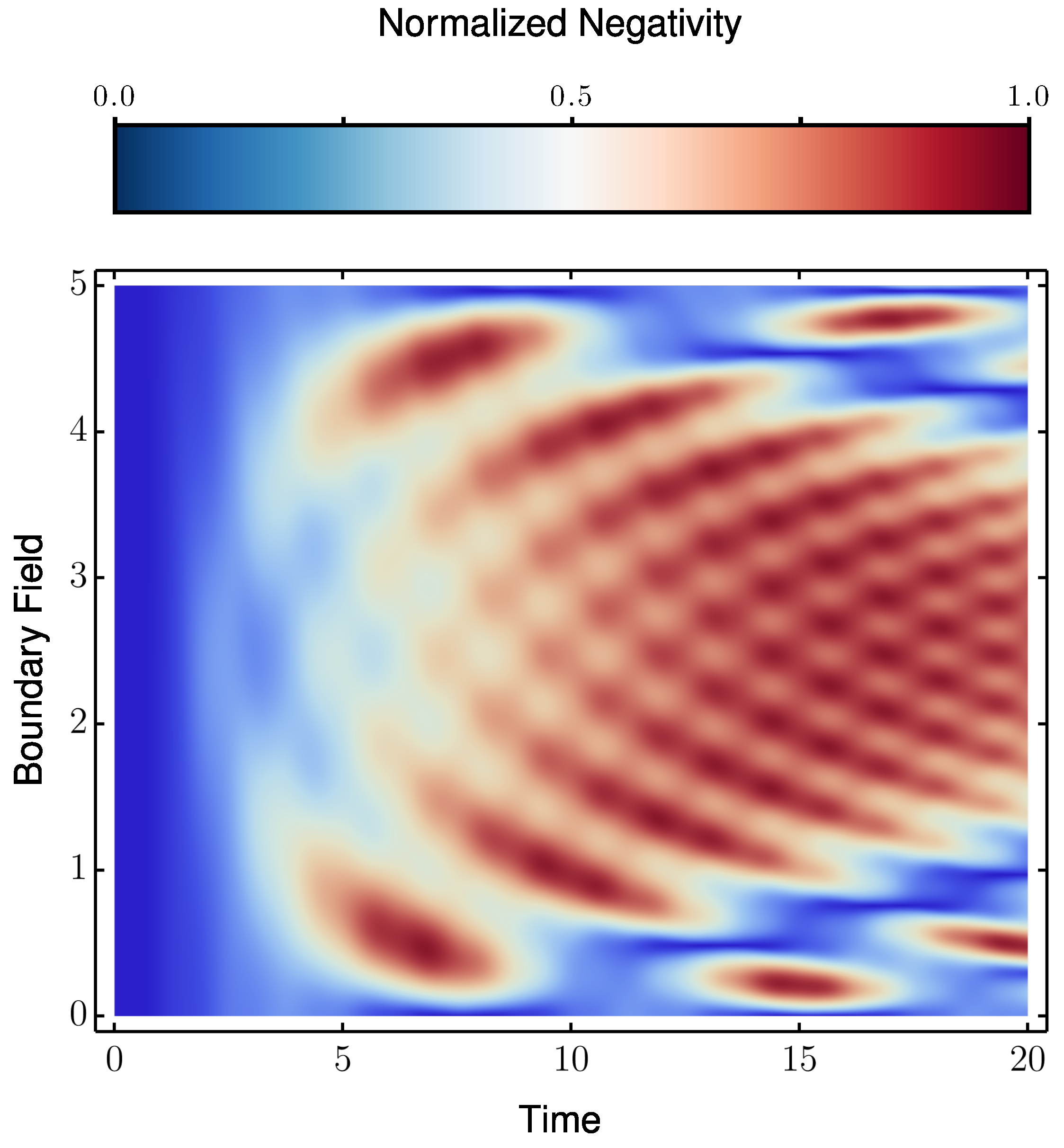

The P2 can also be extended to arbitrary chain lengths

N when

, making it possible to obtain maximally entangled states for higher values of

N. For each system size, we only need to optimize the boundary magnetic field

B to find the maximal possible negativity between terminal spins. This simple adjustment of

B for different

N consistently yields maximal or near-maximal entanglement, demonstrating the scalability of the protocol. To determine the optimal value of

B, we numerically analyze the relationship between

B and the resulting negativity, identifying the parameter regimes and time scales that maximize negativity, as shown in

Figure 4.

3.2. Robustness of the spin-1/2 protocol

The performance advantage of P2 is most relevant when it survives realistic imperfections. Therefore, we investigate its stability against static disorder, focusing on the spin- chain as a representative and experimentally accessible platform. To achieve this, we quantitatively assess its stability by introducing static disorder in spin- chains—a platform chosen for both its theoretical tractability and its experimental relevance. The analysis focuses on two fundamental channels of disorder that reflect distinct physical origins.

First,

on-site (diagonal) disorder tests P2’s sensitivity to variations in the fine-tuned boundary magnetic fields essential for its operation. To model fabrication-induced energy offsets, we introduce random local fields

with

uniformly distributed, where

E scales the disorder strength relative to weak coupling

. This modifies the Hamiltonian as:

For comparison, we apply identical perturbations to P1, establishing a performance baseline under equivalent conditions.

Second,

coupling (off-diagonal) disorder captures imperfections in exchange interactions arising from material defects or control errors. The modified couplings

yield the adjusted Hamiltonian:

We investigated three distinct regimes: (i) pure on-site disorder, (ii) pure coupling disorder, and (iii) simultaneous disorder. For each disorder strength E, we ensure statistical reliability by computing the end-to-end peak negativity across realizations. Specifically, for each realization, we simulate the time evolution under the corresponding disordered Hamiltonian, record the maximum entanglement value attained during the evolution, and then average this value over all realizations. The resulting data points, plotted for varying E, quantify the robustness of both protocols against realistic experimental imperfections.

Three cases were analyzed: (i) pure on-site disorder, (ii) pure coupling disorder, and (iii) both disorders acting simultaneously. We begin by analyzing pure on-site disorder.

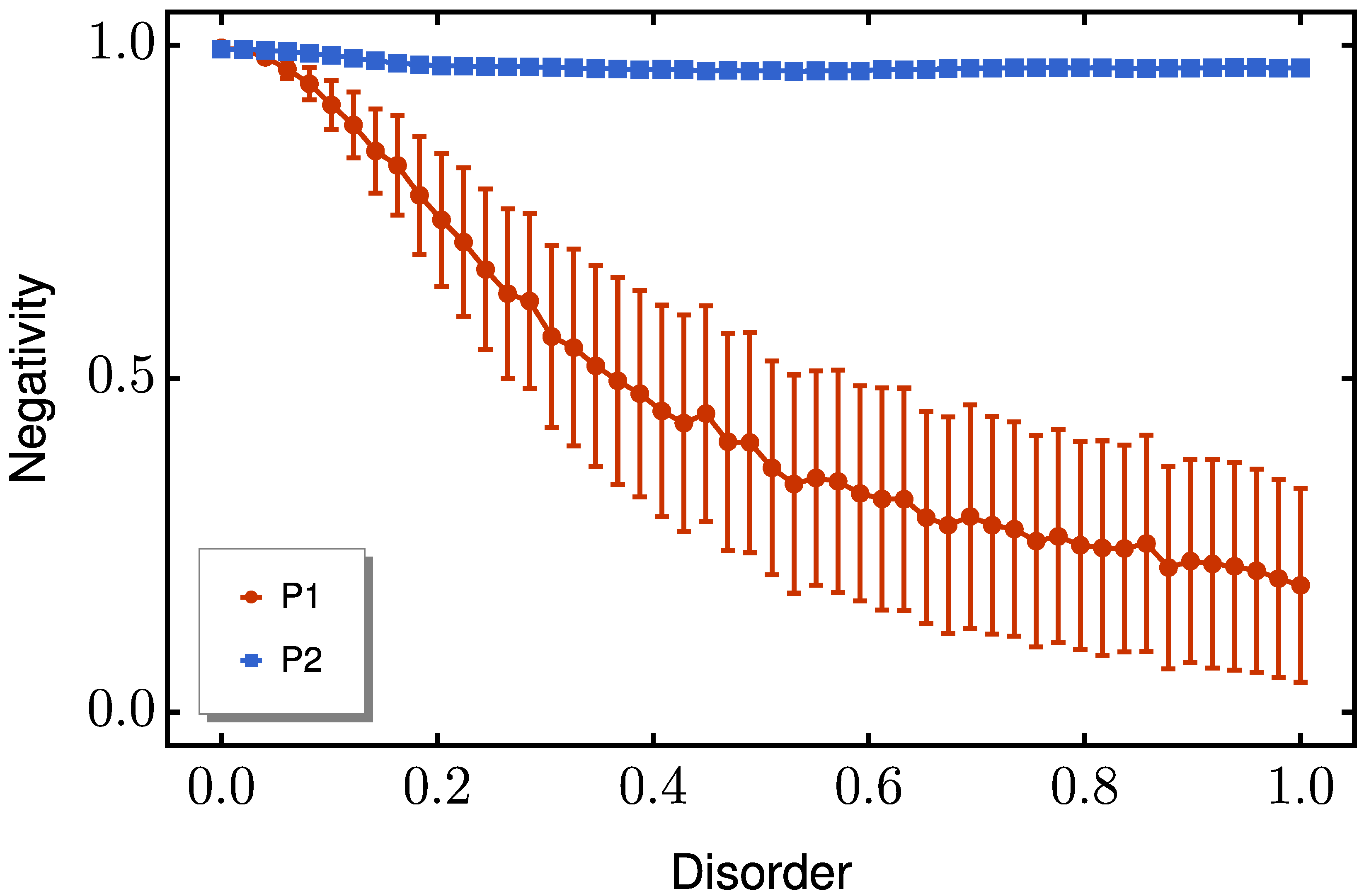

Figure 5 shows that P2 maintains excellent performance even at high disorder strengths, while P1 suffers significant entanglement degradation. This robustness is particularly valuable for practical implementations, as it allows for high entanglement generation (high negativity values) despite imperfections in the applied boundary magnetic fields.

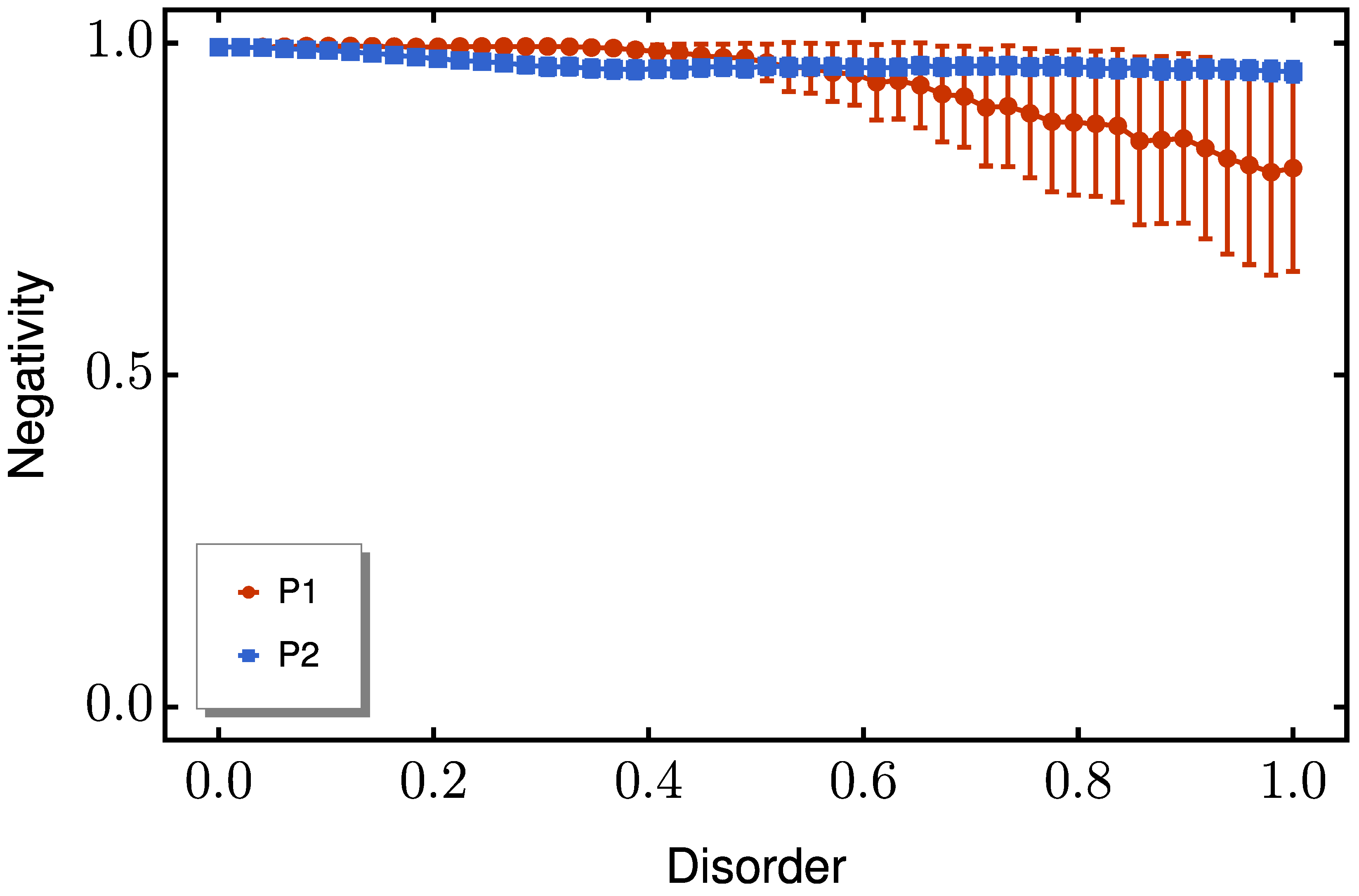

A similar advantage emerges for coupling disorder (

Figure 6), where P2 maintains substantial entanglement (

) even at values of

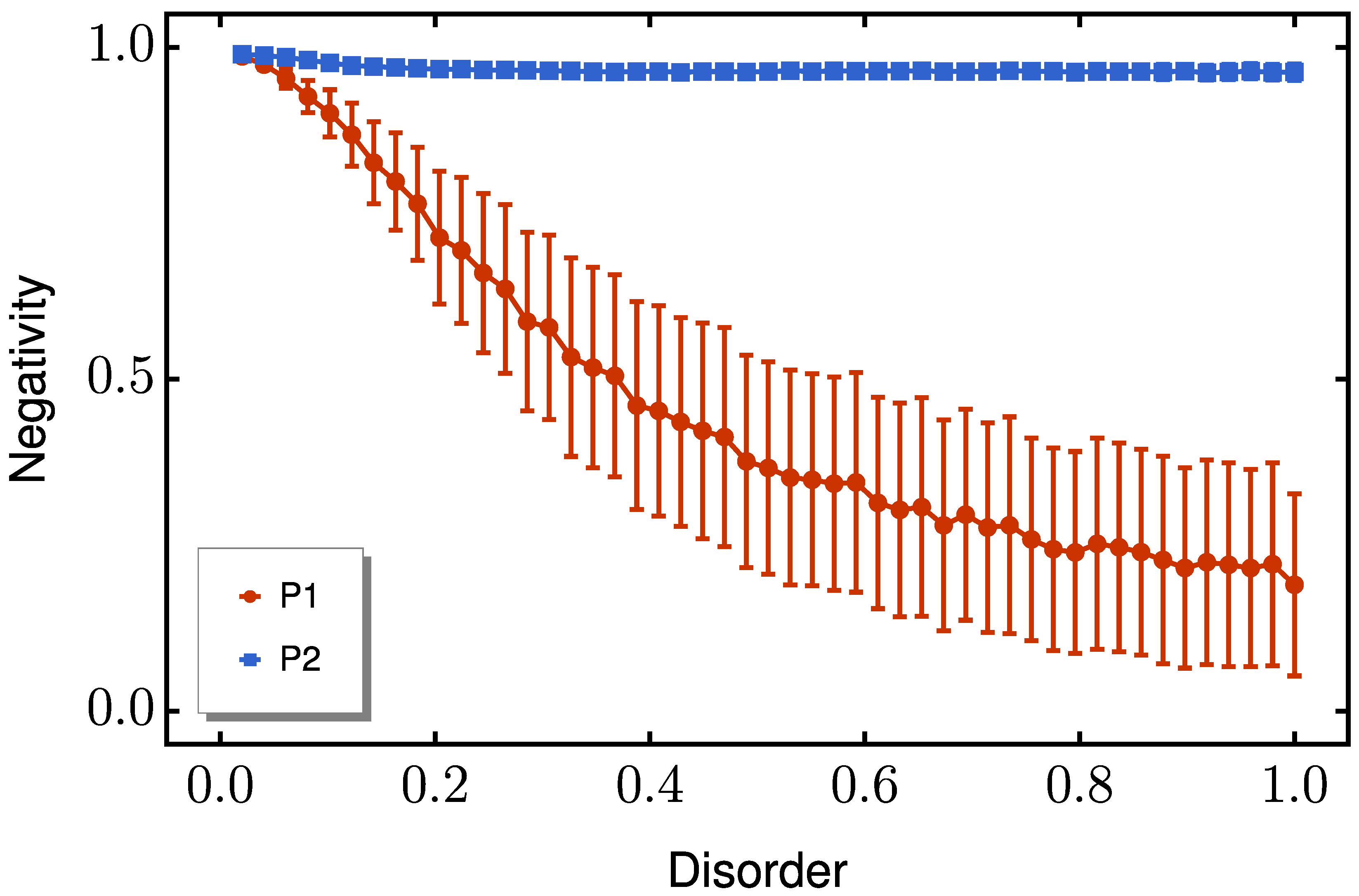

. Interestingly, when diagonal and off-diagonal disorders are present simultaneously, P2 continues to outperform P1, as shown in

Figure 7. This consistent superiority across all disorder regimes confirms P2’s exceptional resilience to typical solid-state fabrication imperfections.

3.3. Resistance to dephasing

A ubiquitous source of decoherence in solid-state devices is pure dephasing of the qubits that terminate the spin chain and interface it with external control circuitry. To assess its influence, we numerically evolve the

full Lindblad master equation [see Eq. (

2)], in which the term

already models local dephasing for every site. By sweeping the dephasing rate

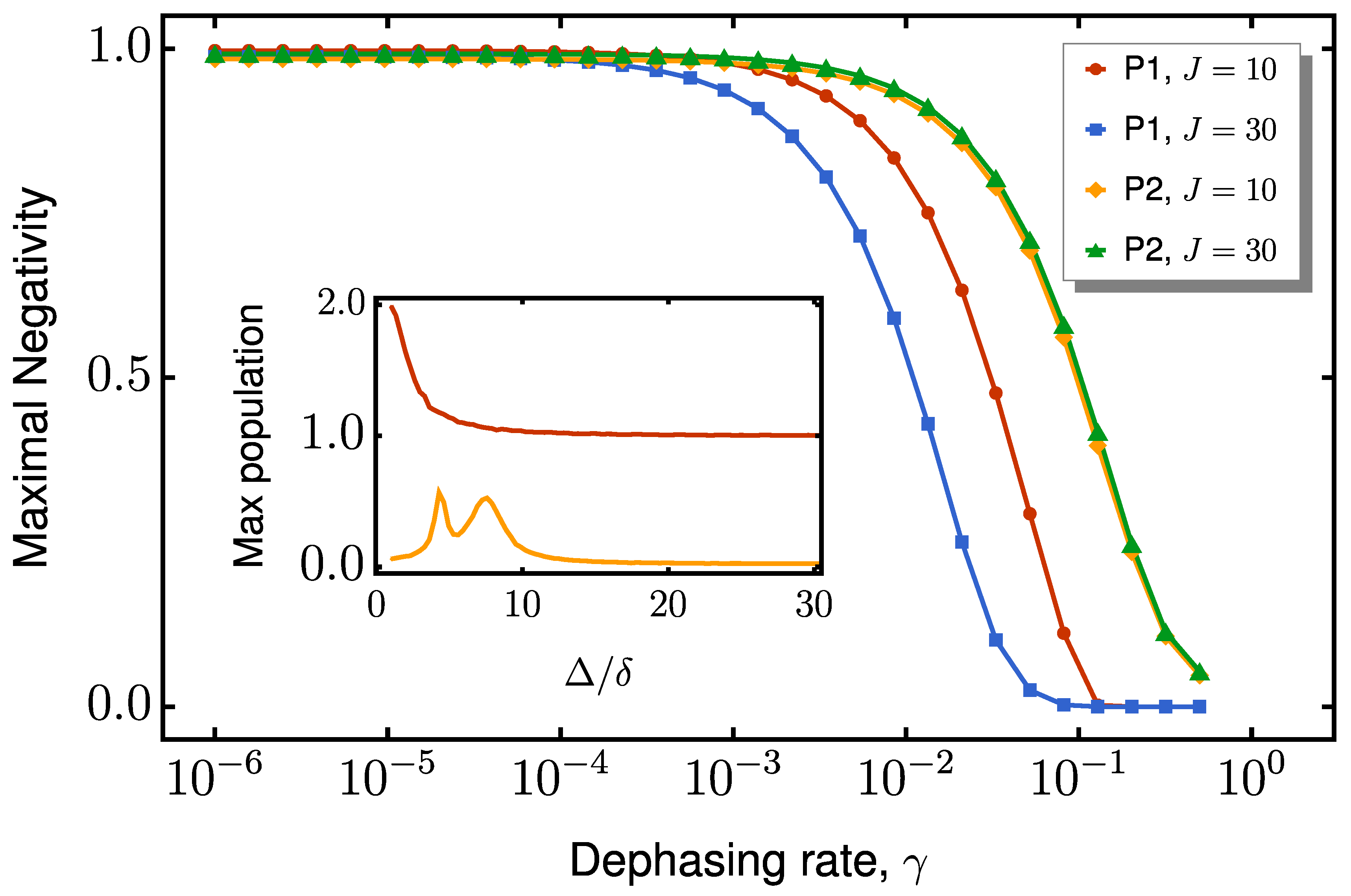

and recording the peak end-to-end negativity, we obtain the curves in

Figure 8. The qualitative difference in decay trends between protocols P1 and P2 can be understood through the lens of the effective Hamiltonian derived in

Appendix A.

In the dispersive regime (

), the spin chain associated with P2 reduces to an effective two-qubit model

with an accompanying Lindblad term

and

defined in Eq. (

A4). Here, the dephasing rate

is renormalized as

indicating that dephasing within the bulk enters only at higher order. Since the chain spins remain virtually unexcited, the entangled state decays predominantly through the suppressed rate

, explaining the gradual decline of negativity in P2 (

Figure 8). In contrast, P1 lacks this protection, leading to a more pronounced sensitivity to dephasing.

This distinction is clearly illustrated in the inset of

Figure 8, which plots the maximum bulk excitation as a function of the coupling ratio

for both protocols. P2’s enhanced resilience to dephasing arises from its effective decoupling from the bulk, whereas P1 relies on direct excitation transport through the chain, making it significantly more vulnerable to noise. The key difference lies in how entanglement is generated: P1 requires the physical propagation of excitations through intermediate spins before boundary entanglement can be established. As each of these intermediate spins becomes populated, the system accumulates dephasing noise at each site. This sequential exposure results in a larger bulk population (see the red curve in the inset of

Figure 8) and a sharper degradation of entanglement. In contrast, P2 consistently maintains a low bulk occupation (orange curve in the inset of

Figure 8) across all tested

ratios. This population suppression directly explains the significantly flatter negativity decay curve for P2 in the main panel of

Figure 8: by avoiding the buildup of noise along the chain, it preserves entanglement more effectively under dephasing.

The enhanced protection in P2 comes from two key factors related to the dimerization ratio

: First, higher values push the system deeper into the dispersive regime, suppressing the real chain occupation. Second, the effective dephasing rate

decreases quadratically with

, explaining why P2’s negativity curves in

Figure 8 decay increasingly slowly as

grows. The combination of these effects, the minimal bulk population, and suppressed

, gives P2 its characteristically flat negativity decay.

In contrast, P1’s excitation-mediated transport remains fundamentally exposed to dephasing regardless of , as its physical propagation mechanism inevitably populates intermediate sites. While stronger dimerization may slightly reduce bulk occupation, it cannot eliminate the accumulation of sequential noise along the chain. This stark difference highlights the central advantage of virtual tunneling: by avoiding real excitations in the bulk, P2 naturally decouples from noise sources while maintaining efficient end-to-end entanglement generation.

4. Conclusions

We have conducted a comprehensive numerical study of two entanglement generation protocols in XX spin chains, evaluating their performance across spin magnitudes , 1, and . Our analysis reveals that the dual-port architecture (P2) consistently achieves higher entanglement on shorter timescales than its staggered counterpart (P1) for all the spin values considered.

In addition to its speed advantage, P2 demonstrates strong robustness against both diagonal and off-diagonal disorder, as well as local dephasing noise. This resilience is attributed to its design, which minimizes excitation of the bulk spins through optimized boundary control and coupling symmetry, thereby enhancing coherence and reducing vulnerability to noise.

These features make P2 not only more efficient but also more scalable and robust, establishing it as a strong candidate for practical implementations in entanglement-based quantum information processing. Future work may explore the extension of this protocol to larger spin networks, the incorporation of non-Markovian environmental effects [

52], and embedding it within hybrid quantum architectures [

53]. These directions could be further enriched by integrating advanced techniques such as color-engineered communication channels [

54], star-like entanglement hubs for multi-qubit interfacing [

55], and dissipative stabilization mechanisms for steady-state entanglement [

56].