1. Introduction

Lubricating grease compatibility is a critical aspect in industrial maintenance and machinery operation. The compatibility between different greases determines the effectiveness of lubrication, impacts the longevity of machinery components, and influences maintenance schedules. It is well known that the mixing of two greases can produce a substance markedly inferior to either of its constituent materials. Lubricating grease is composed of base fluid, a thickener, and various additives. The base fluid, which can be mineral, synthetic, or bio-based (or mixtures thereof), provides the primary lubricating properties. The thickener, often a soap or non-soap substance, gives the grease its semi-solid consistency. Additives enhance specific properties such as anti-wear, corrosion resistance, and oxidation stability. Therefore, factors that may potentially affect compatibility will include predominantly the thickener systems, but also the dispersion medium and the type of incorporated additives’ chemistry. Incompatibility between greases can result in several adverse effects, such as grease hardening or softening and oil separation. Excessive syneresis can occur, forming pools of liquid lubricant separated from the grease. Dropping points (i.e., thermal stability) can be reduced to the extent that grease or separated oil runs out of bearings at elevated operating temperatures. Such events will gradually give rise to loss of performance, increased wear, more frequent relubrication and maintenance, and could even lead to catastrophic lubrication failures. Because of such occurrences, equipment manufacturers recommend completely cleaning the grease from equipment before installing a different grease. The best practices for ensuring compatibility include consulting manufacturer guidelines, to promote a gradual transition, while doing proper and regular testing, training, and record-keeping to avoid severe implications. It is often said that taking a very conservative approach when switching from one grease to another, by assuming that new and old greases are incompatible unless comprehensive testing has proven otherwise, can always prevent problems. However, grease and equipment manufacturers alike recognize such practices, like grease mixing, will occur—and, at times, cannot be avoided—despite all warnings to the contrary. Thus, both users and suppliers need to know the compatibility characteristics of the greases in question. End users frequently rely on the so-called grease compatibility charts that are publicly available in manuals, textbooks, etc. These charts rate the compatibility of pairs of greases based solely on thickener types and, in many cases, do not agree with one another. Since these charts will not report on the methodology used to create their ratings, end users are not aware of their limitations and the fact that they have been developed for generic guidance only and not for any specific application. By understanding the factors affecting compatibility, conducting regular testing, and following best practices, industries can ensure optimal lubrication performance and enhance the longevity of their machinery. The main practice for assessing grease compatibility is to take a specification-independent approach, which describes the evaluation of compatibility on a relative basis using specific test methods. This approach is described in the ASTM D6185—Standard Practice for Evaluating Compatibility of Binary Mixtures of Lubricating Greases. The protocol involves mixing two greases in various proportions and evaluating the mixture’s properties compared to the individual greases [

1,

2,

3,

4].

Lithium grease is widely recognized for its versatility, excellent performance, and affordability. According to the market data included in the latest NLGI Grease Production Survey Report, lithium soap-based greases still hold the lion’s share—despite the considerable decrease (use to dominate with a 77% share back in 2013), accounting for a volume of almost 60% of all the greases that are globally produced. In recent years, there has been a decline in the simple lithium soap products and a continuing trend in lithium complex grease, yet with a reported deceleration even for the latter. Globally, lithium complexes are around 20 wt% of the market, but in North America, the volume is just above 40 wt%. The reasons behind replacing lithium-based greases can be summarized in the following:

Sustainability and Environmental Concerns: Lithium mining and processing have significant environmental impacts, including water consumption and increased carbon footprint, especially the spodumene-sourced one. On the contrary, Ca(OH)2 has more than 10 times lower GHG emissions (Johan Leckner: Can Calcium Limit Lithium reliance, presented at 34th ELGI AGM 2024).

Health Concerns: The European Union’s Chemicals Agency (ECHA) had proposed that lithium hydroxide be classified as a Reprotoxic 1A. High levels of free lithium hydroxide above the thresholds (0.1 wt% USA and 0.3 wt% EU-27) in grease will trigger labelling on finished greases. In Japan, lithium hydroxide is defined as a poisonous and deleterious substance.

Supply Chain Issues: The global demand for lithium, driven by the electric vehicle industry and battery production, leads to supply chain constraints and increased costs for lithium-based products.

Overall, the production survey reports thickener changes in response to lithium issues. The following chemistries demonstrate a trend and may play a significant role as alternatives to lithium and lithium complex greases in various applications:

Calcium Sulfonate Grease: Improved water resistance, superior load-carrying capacity, and high-temperature performance. It also provides exceptional corrosion protection. Ideal for marine, industrial, and heavy-duty off highway automotive applications where moisture and high loads are common.

Polyurea Grease: High oxidation stability, long service life, and excellent performance in high-temperature environments. It is also compatible with electric motor bearings. Commonly used in electric motors, automotive applications, and high-speed bearings.

Aluminum Complex Grease: Good water resistance, mechanical stability, and high-temperature performance. Suitable for automotive, industrial, and construction machinery applications.

It is recognized that, commonly to what is taking place in every transition, there would be implications during the gradual changeover from lithium-based greases. Factors and aspects that should be taken into consideration are the performance improvement potential, the balance in the environmental benefits, the cost considerations, and last but not least, the compatibility and conversion issues. When replacing lithium grease, it is crucial to ensure compatibility with existing lubrication systems and components. A gradual transition, accompanied by thorough testing and monitoring, can mitigate risks associated with grease incompatibility [

5,

6,

7].

Based on the above and given the forthcoming gradual replacement of lithium greases, the study aimed to investigate the compatibility limits of binary grease blends consisting of lithium complex and other potential alternatives, such as aluminum complex, polyurea, and calcium sulfonate complex, by employing the ASTM D6185 protocol.

2. Materials and Methods

Four lubricating grease samples of different types of thickening agents were utilized in this study.

Table 1 summarizes their basic information. According to what has been reported above, they comprise Lithium Complex (LiX), Polyurea (PU), Aluminum complex (AlX), and Calcium Sulfonate Complex (CaSX) thickeners. All four greases are fully formulated, commercially available products finished to an NLGI #2 consistency. The fundamental quality parameters of the test greases are listed in

Table 2. All but one (AlX) comprises a mineral base oil as dispersion medium with a base oil viscosity grade of 220. AlX was based on a 460 ISO VG base oil composed of a mix of polyalphaolefin and mineral oil.

A test program was conducted on the above four grease formulations by forming binary mixtures of the LiX sample with each one of the other three grease samples (AlX, PU & CaSX). Nine two-component blends were prepared and tested based on the matrix shown in

Table 3. Additionally, the individual greases were tested. Predictions for two-component blends were made from calculations using test data for individual greases.

The binary mixtures were blended at three different ratios, namely at 50:50 (a uniform blend of 50% m/m of each of two component greases), at 25:75 (a uniform blend of 25% m/m of LiX with 75% m/m of a second grease) and 10:90 (a uniform blend of 10% m/m of LiX with 90% m/m of a second grease). All binary blends (and neat grease) were prepared by spatulating, with no more than about 4 hours between mixture preparation and the start of any test The 50:50 mixture simulates a ratio that might be experienced when one grease (Grease A) is installed in a bearing containing a previously installed, different grease (Grease B), and no attempt is made to flush out Grease B with Grease A. The 25:75 and 10:90 ratios are intended to simulate ratios that might occur when attempts are made to flush out Grease B with Grease A. Incompatibility is most often revealed by the evaluation of 50:50 mixtures. However, in some instances, 50:50 mixtures are compatible, and more diluted ratios are incompatible.

The Standard practice of ASTM D 6185 was applied in this work to assess the compatibility limits of the examined binary mixtures. The practice covers a protocol for evaluating the compatibility of binary mixtures of lubricating greases by comparing their properties or performance relative to those of the neat greases comprising the mixture. The protocol officially employs mixing ratios of 50:50 and 10:90, yet in this work, it was extended to incorporate the intermediate 25:75 blend.

The original ASTM method includes a primary testing protocol (i.e., those test methods employed first to evaluate compatibility) that consists of the following three standard methods:

• Dropping point by Test Method D2265

• Shear stability by Test Methods D217, 100 000–stroke worked penetration; and

• High-Temperature Storage Stability by change in 60-stroke penetration. This is based on the Federal Test Method (FTM) 3467.1 that determines the work penetration of a sample after it has been subjected to thermal stress at 120 °C for 70 hours. The consistency of the grease samples was measured on a full-scale penetrometer (Test Method D217).

A main modification that took place in the primary testing protocol is the use of the ASTM D1831 Grease Roll Stability standard method instead of the 100,000–stroke worked penetration for evaluating the shear stability of the binary blends. A similar approach has been reported in the literature regarding the compatibility of LiX with AlX greases [

2], for which it is stated that they generate comparable results, with the former being much faster to run. According to the ASTM standard, there are two Options for running the primary testing for compatibility of binary grease mixtures. Option 1 procedure includes the initial testing of constituent Greases A and B and a 50:50 mixture, which is followed by testing of other binary mixing ratios in a sequential order. Alternatively, Option 2 can be used. Instead of testing mixtures in sequential order, all selected binary samples are examined concurrently. If one wants to strictly abide by the ASTM protocol, then either the sequential or concurrent testing is continued until the first failure. If any mixture fails any of the primary tests, the greases are incompatible. If all mixtures pass the three primary tests, the greases are considered compatible. Since the aim of the study was to generate the required data to assess the overall compatibility limits of all examined binary grease mixtures, irrespective of the mixing ratios or any standalone failure, the methodology was carried out as per Option 2. Furthermore, the secondary testing scheme was also applied—again, irrespective of the primary testing compatibility results—and included the following determinations:

• Oxidation stability test. Determinations were conducted by ASTM D8206 standard test method by utilizing the Rapid Small Scale Oxidations Test apparatus. The test was carried out at a temperature of 140 °C.

• Wear Preventive Characteristics. The binary mixtures were assessed at the Four Ball Wear Test machine per ASTM D2266.

The purpose of incorporating these two protocols in the study was to extend the testing scheme by including determinations that may provide further data per the behavior of the binary blends during application and to compare the generated results with what has already been demonstrated in the primary testing scheme. The data produced were analyzed using both the ASTM D6185 definitions as well as literature (LCL—literature compatibility limits) definitions for compatibility, borderline compatibility, and incompatibility for each test method. The ASTM acceptability limits are based on test method repeatability, whereas the LCL acceptability limits are based on practical experience and are more generous than the ASTM limit [

2].

Table 4 summarizes the rating criteria by test method and by acceptability protocol. For the sake of presenting compatibility results more comprehensively, the measured values are also graphically depicted and compared against the corresponding theoretically predicted values that assume a linear variation of each property.

3. Results

3.1. Primary Testing Scheme: Dropping Point

Dropping point represents the corrected temperature at which the first drop of material falls from the test cup and reaches the bottom of the test tube. It defines the temperature at which the grease loses its structural integrity and liquefies. It indicates heat resistance and is mainly attributed to the characteristics of the thickener [

1]. The dropping point test is frequently used to test for quality control at the formulation stage, since for each thickening agent, there exists a temperature range at which it is expected to drop. Any significant variation from this typical temperature range implies that the grease structure has either not formed properly during production or has undergone deterioration due to external factors. One of them could be the blending with non- or partially compatible greases during application, which may challenge the ability of the grease to lubricate. A significant decrease in the dropping point will compromise the thermal stability of the grease and will mean that it will start to lose its structural integrity at lower temperatures than expected.

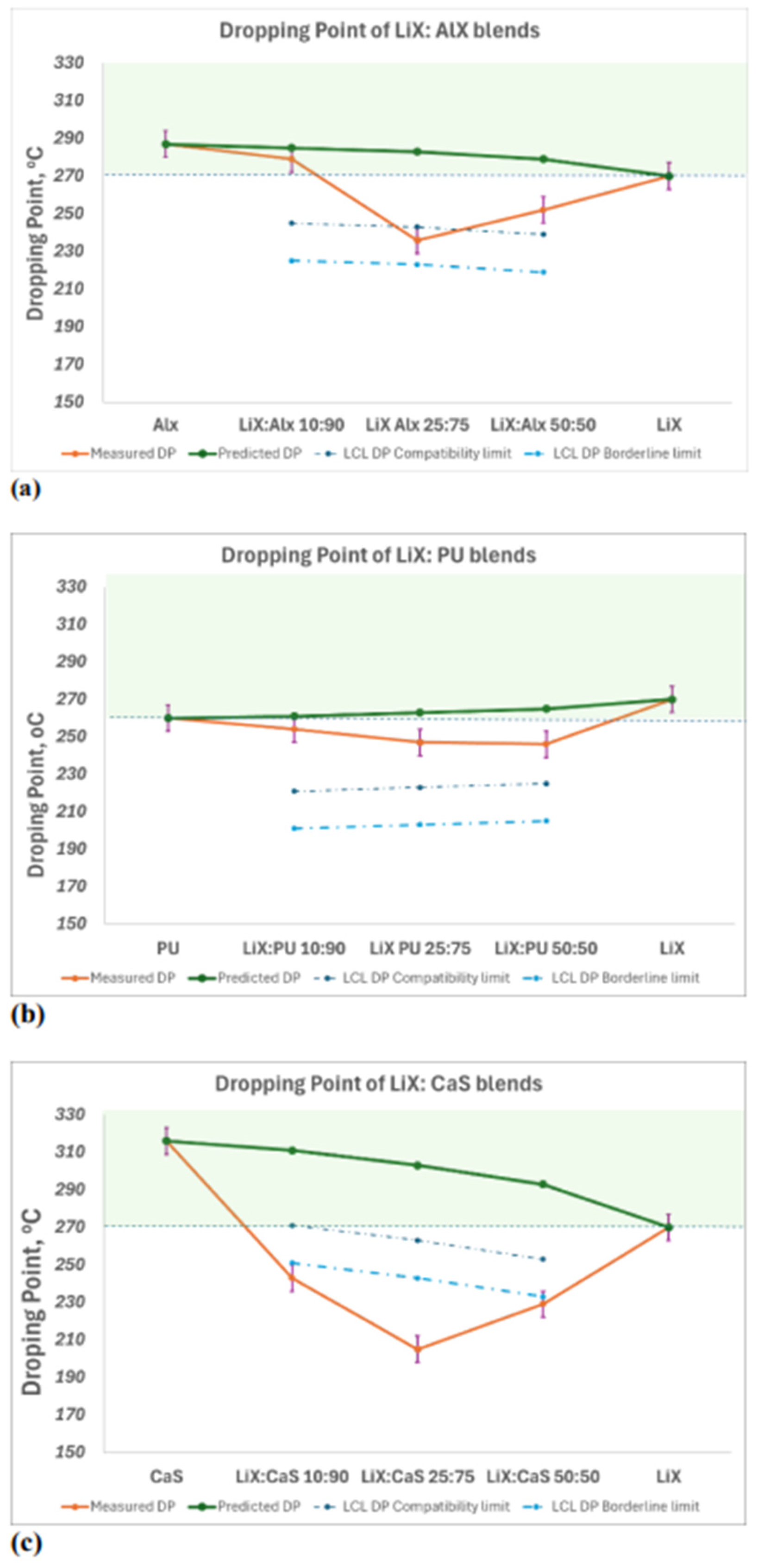

The results from the dropping point determinations of the examined binary mixtures are depicted graphically in

Figure 1. In each graph, the actual determinations as well as the predicted values of the binary mixtures are shown, along with the values of the individual constituents. A green colored area is representative of the compatibility range for each blend. Moreover, the corresponding lines for the LCL compatibility and borderline limits are also included.

Based on the data generated, the dropping point property appears to be the most challenging among the tested ones. Following the more severe ASTM criteria, out of the nine binary mixtures, only the LiX:AlX 10:90 would be judged as compatible, while the blend LiX:PU 10:90 is considered to be borderline compatible. The rest of the grease mixtures are judged as incompatible. Similar observation on the dropping point is reported in a previous study on lithium complex and aluminum complex greases in which none of the examined blends were either marginally or fully compatible [

2]. On the other hand, the more generous literature limits (LCL) give rise to a higher rate of compatible mixtures for the LiX:AlX and especially for LiX:PU. In terms of the dropping point, the LiX:CaSX proves to be the least efficient binary blend under all mixing ratios and both acceptance limits. Dropping point property is highly compromised, and this is obvious from

Figure 1(c), where the difference between the measured and the predicted values is considerably higher than what is observed in the other two combinations. Particularly, the 25:75 LiX:CaSX

—and not the 50:50, as it would be expected

—demonstrates a dramatic decrease in the thermal stability by more than 100 °C. Similarly, the 25:75 blend generated the worst-case scenario in LiX:AlX, as well. Judging from the actual numbers that appear in the graphs and irrespective of the compatibility ratings, it appears that the LiX:PU combination is the most efficient since it exhibits the lowest deviation of the measured values from the predicted ones. It is mentioned that this combination is the only one out of the three in which the dropping point of the hypothetically substituting grease (PU) is lower than that of the original (LiX).

3.2. Primary Testing Scheme: Shear Stability

It is highly important for a grease to demonstrate adequate consistency and stability for the service conditions and relubrication intervals. Mechanical degradation by shear is one of the mechanisms that limits the lifetime of lubricating grease in a rolling bearing. It results in a change of the micro-structure of the thickener–oil system, leading to a change in bleed and consistency [

8]. In this degradation process, the bonds between the individual molecules, consisting mainly of the weak van der Waals bonds and/or hydrogen bonds, are broken during this shearing process [

9]. Softening due to the shearing (more frequent) of the lubricant could lead to leakage and grease loss, while a stiffening effect could give rise to channeling effect and increased yield stress [

10]. Moreover, mixing incompatible greases increases the risk of a considerable change in the consistency of the binary blend due to the matrix interactions and bonding rearrangement.

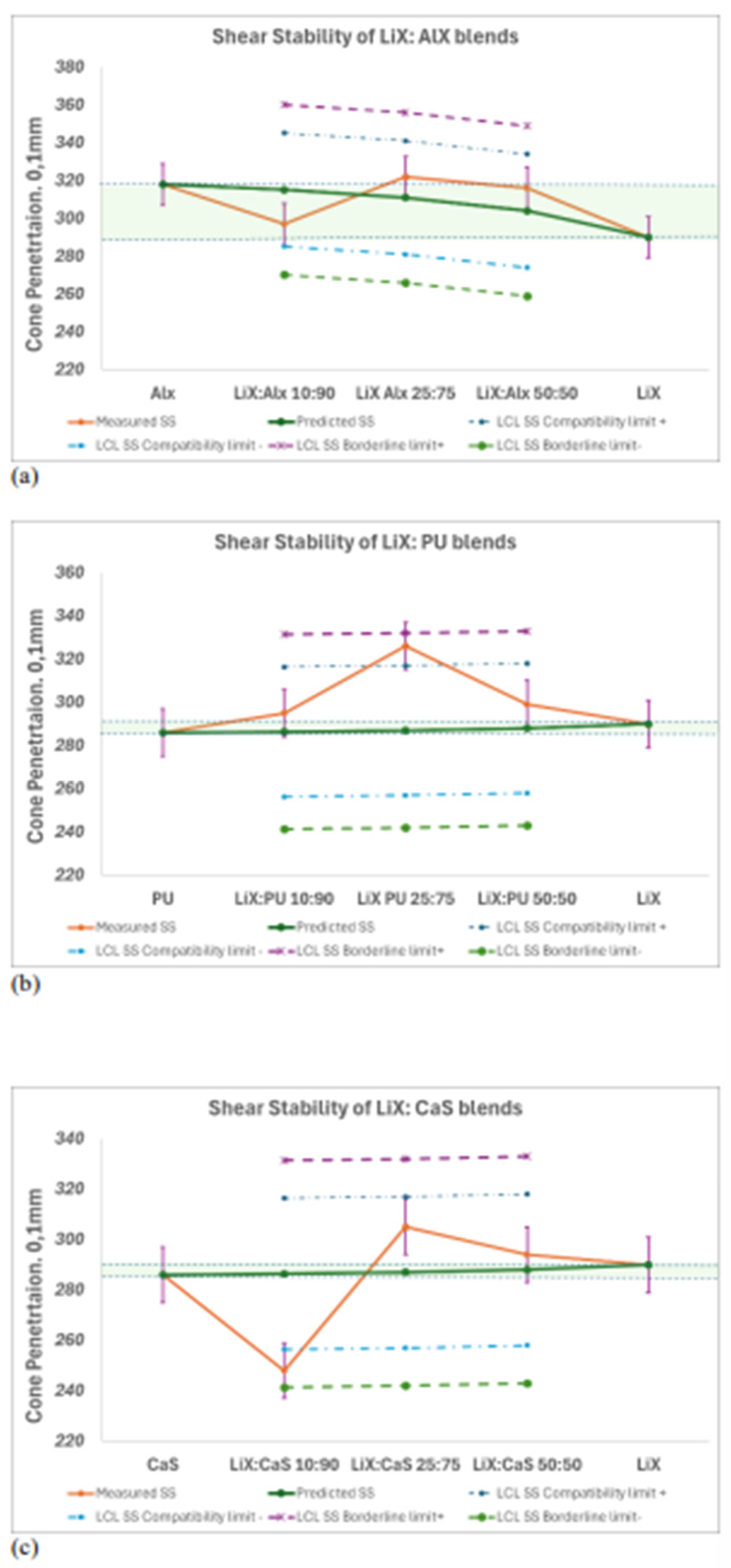

Roll stability is the change in consistency of a sample after a specified amount of working in a test apparatus utilizing a weighted roller inside a rotating cylinder. This test produces relatively low rates of shear and covers the determination of the changes in the consistency, as measured by cone penetration, of lubricating greases.

Figure 2 presents the roll stability determinations of the three grease combinations under all mixing ratios. Again, the measured and the predicted values of the binary mixtures are shown for each case, and the green colored area is indicative of the compatibility acceptability limits. The LCL compatibility and borderline upper and lower limits are also shown. The first observation is that LiX:AlX greases show a similar pattern to LiX:CaSX in the behavior per the mixing ratio. Specifically, at a 10:90 mixing ratio, penetration decreases, whereas at 25:75 and 50:50, the consistency is lower. This means that when LiX is almost flushed out of the system, either by AlX or CaSX, it is expected that shearing may induce a hardening effect on the binary grease. On the contrary, when the original grease (LiX) is not completely flushed from the application (25:75 and 50:50), shearing may lead to a softer binary mix. In any case, the observed effects are more prominent in the LiX:CaSX combination than in the LiX:AlX blends. The LiX:PU samples demonstrate more consistent behavior since in all tested mixing ratios, rolling has given rise to an increase in the worked penetration values, with the 25:75 blend being the least efficient. By analyzing the results with the ASTM and LCL limits, the incompatibilities are still there in some of the blends, yet less severe compared to what has been observed previously in the dropping point determinations. The better roll stability performance in compatibility studies has also been demonstrated in the literature [

2]. By either definition, all LiX:AlX combinations are judged as compatible or borderline compatible, while the LiX: CaSX combinations constitute, once more, samples with a more challenging behavior in terms of shearing. In the roll stability test LiX:PU samples show overall a marginally acceptable trend except for the 25:75 ratio.

3.3. Primary Testing Scheme: High Temperature Storage Stability

This method covers a technique used for measuring the stability of a lubricating grease after a definite storage period at an elevated temperature (120oC). A determination for consistency (worked penetration) is made after the storage interval (70h) and the results compared with data established prior to the storage interval [

11].

The life of lubricating grease is reduced by operation at elevated temperatures. A grease that is subjected to such conditions may experience gross physical and chemical changes reducing its ability to replenish the contact and maintain a satisfactory lubricating film. Extended operation at elevated temperatures may cause evaporation of low molecular weight base oil components and oxidative deterioration of one or both of the grease components. Mixing of potentially incompatible grease formulations may accelerate the physicochemical alterations at elevated temperatures, affecting the consistency and resulting eventually in premature failure of the equipment [

12,

13].

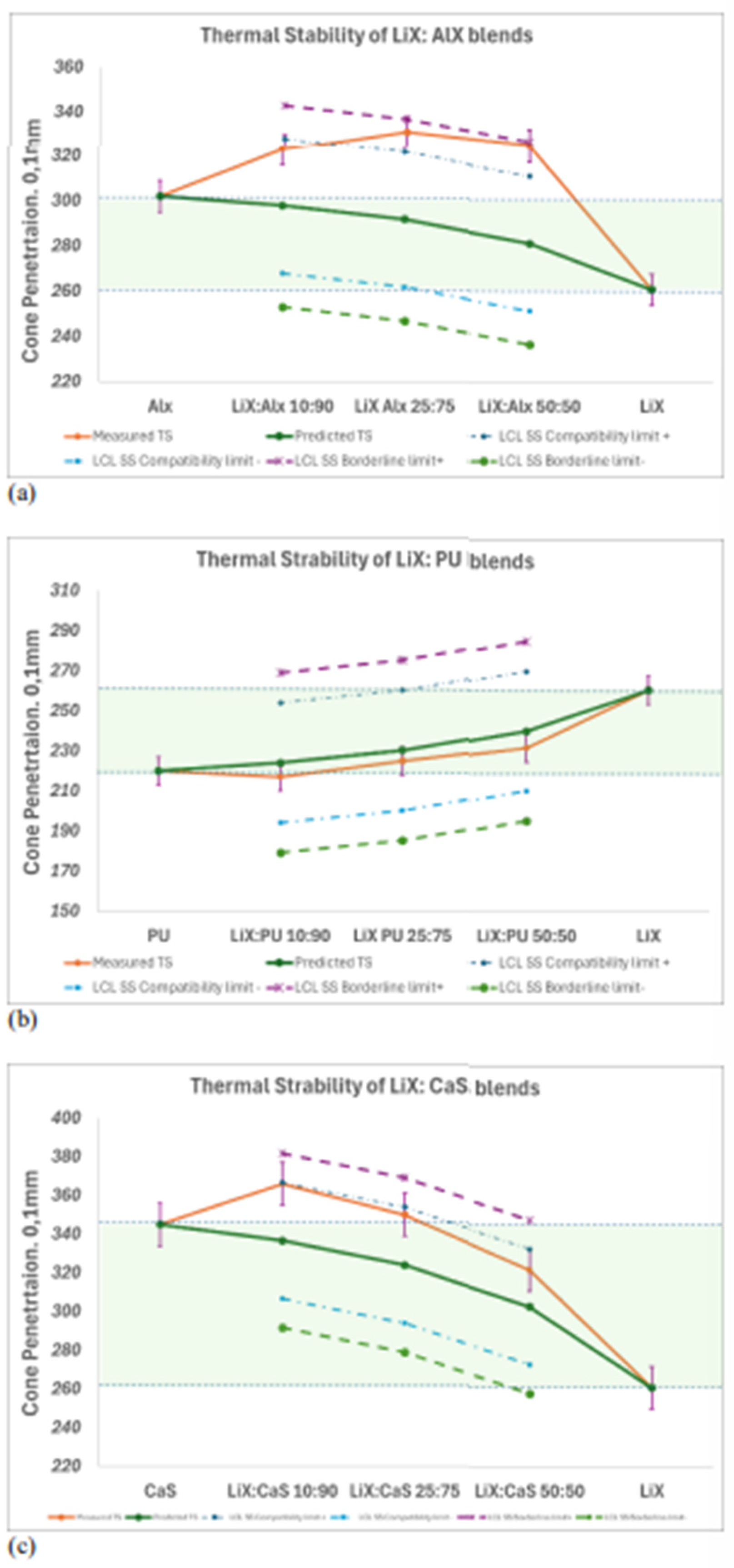

Figure 3 summarizes the results obtained from the high temperature storage stability determinations along with the corresponding predicted values and the compatibility range limits. A different effect of the extended storage stability can be seen between the various binary mixtures, and this appears to be relative to the behavior of the individual constituents in each grease. By comparing the storage stability of the components, as shown in

Table 2, LiX and PU demonstrate an increase in their consistency, whereas AlX and especially CaSX samples become considerably softer at the end of the storage time. As a result the consistency changes of the binary LiX:PU blends appear to be rather smooth and gradual with an increasing mixing ratio of the LiX component. At the same time the line of measured values in Fig3(b) is almost identical to the line of the predicted values

—with the variations being within the precision of the method

—and within the compatibility range as defined by ASTM D6185 standard.

A varied trend and compatibility behavior is observed in the other two grease combinations. LiX:AlX binary blends are the least compatible of the examined greases—irrespective of the mixing ratio—given the variation from the predicted storage stability values and the distance between the measured values and the acceptable compatibility limits. In all Cases the blending of these two individual components gives rise to a considerably softer matrix at the end of the elevated temperature storage stability test compared to what it is theoretically calculated for.

Regarding the LiX:CaSX blends, the effect of the elevated temperature on the consistency of the mixtures is less severe compared to LiX:AlX blends. Again, the procedure leads to higher penetration values compared to the predicted ones, however, only the 10:90 blend is judged as incompatible only in accordance with the stricter ASTM D6185 definition, whereas all binary blends are compatible when evaluated against the practical LCL limits.

It is worth noticing that before measuring the consistency changes of the binary blends the samples have been subjected to homogenization by spatulating. This is an important comment specifically for LiX:CaSX blends since severe oil bleeding has been reported at the end of the test in all these binary blends. This means that gross observation is also significant when judging the relative compatibility of greases and it can reveal properties of the examined samples that may not be directly depicted from the actual measurements. In that sense, a visual assessment procedure could be valuable and considered as an addition to the future version of the ASTM standard.

3.4. Secondary Testing Scheme: Oxidative Stability

The ability of a lubricant to resist thermal and oxidative deterioration is a key parameter for an extended useful life and an untroubled service life. Oxidation is a predominant ageing process that directly affects the life of a lubricating grease [

14]. In the case of greases, it is not only the thickener type that will affect the behavior since the stability of the base oil plays a vital role on the aging characteristics of the grease [

1]. The RSSOT is a fairly new protocol for measuring the ageing reserve of greases, yet the potential of the method is promising in comparing the relative oxidative deterioration tendency. The oxidation stability was selected as a secondary test in the compatibility study because any negative interaction between the two constituents may have an impact on ageing reserve of the grease in the application.

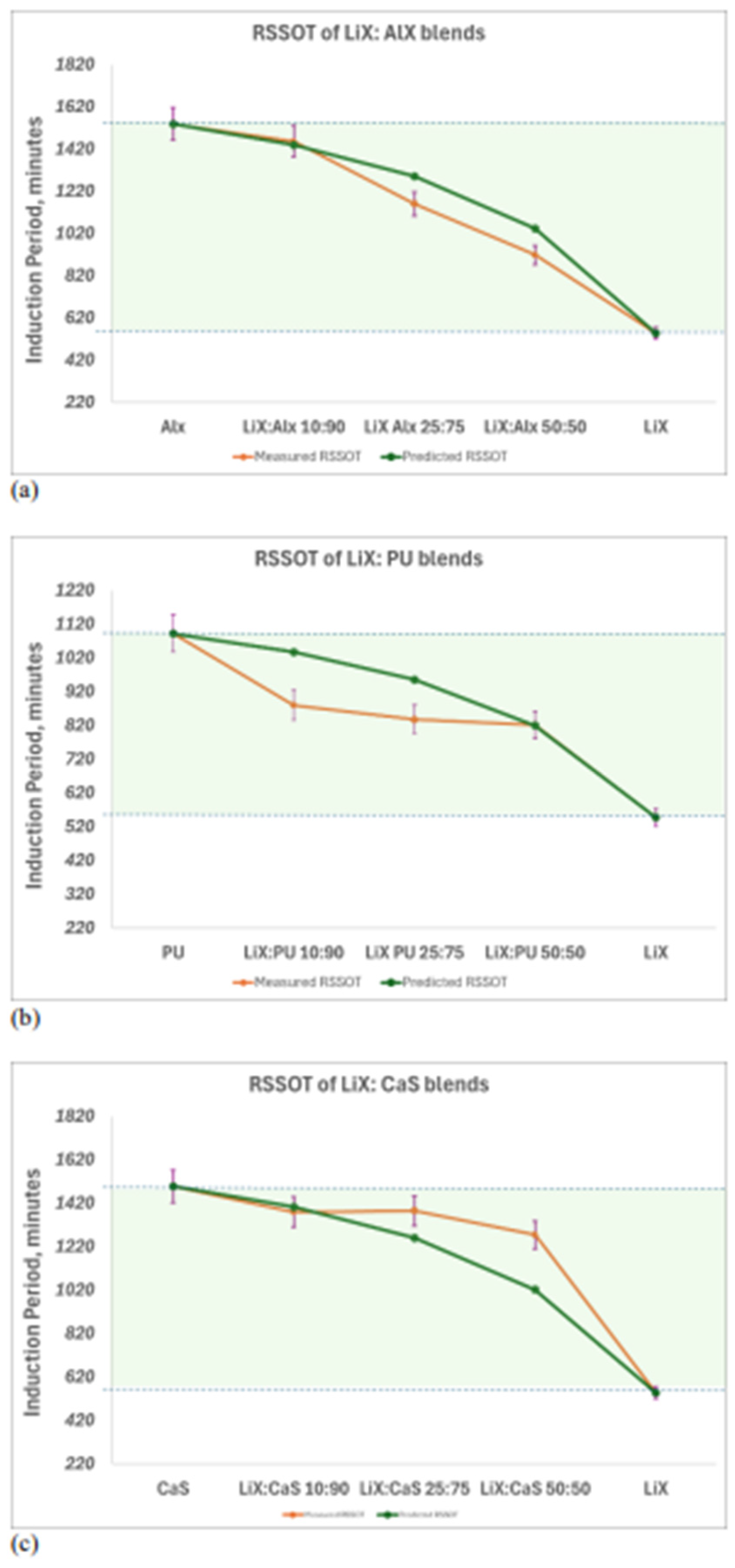

The Induction Period for the test binary grease samples are given in

Figure 4. It is rather clear from all the data generated that in no case oxidation stability appears to be compromised in the binary mixtures even in those cases that the blends have been found to be incompatible by both ASTM and LCL definitions. This means that under the thermal conditions of the test at 140oC there is no evidence that chemical deteriorating changes and interactions are taking place to such an extent that could substantially affect or re-arrange the free radical initiation or propagation stage in the oxidation pathways. This is also an indication of the non-antagonism of the various additives that are incorporated in these three individual candidate greases.

3.5. Secondary Testing Scheme: Wear Preventative Characteristics

During lubrication several parameters can be identified that may lead to metal-to-metal contact that should be controlled to avoid wear damage to the surfaces. The wear preventive characteristics of a lubricating grease refer to its ability to form a protective surface film during boundary lubrication and minimize wear. Four ball test machine is the most employed apparatus for determining the anti wear properties of lubricants. The geometry of the four-ball configuration simulates a system working under the boundary lubrication regime. Under these conditions, the structure of the lubricant plays a vital role in minimizing the contact between the metal surfaces asperities [

15,

16]. The evaluation of the anti wear performance was employed as another secondary test in the compatibility study in order to examine whether any incompatibility in terms of the consistency change could dramatically affect the ability of the binary blend to form an adequate lubricating film.

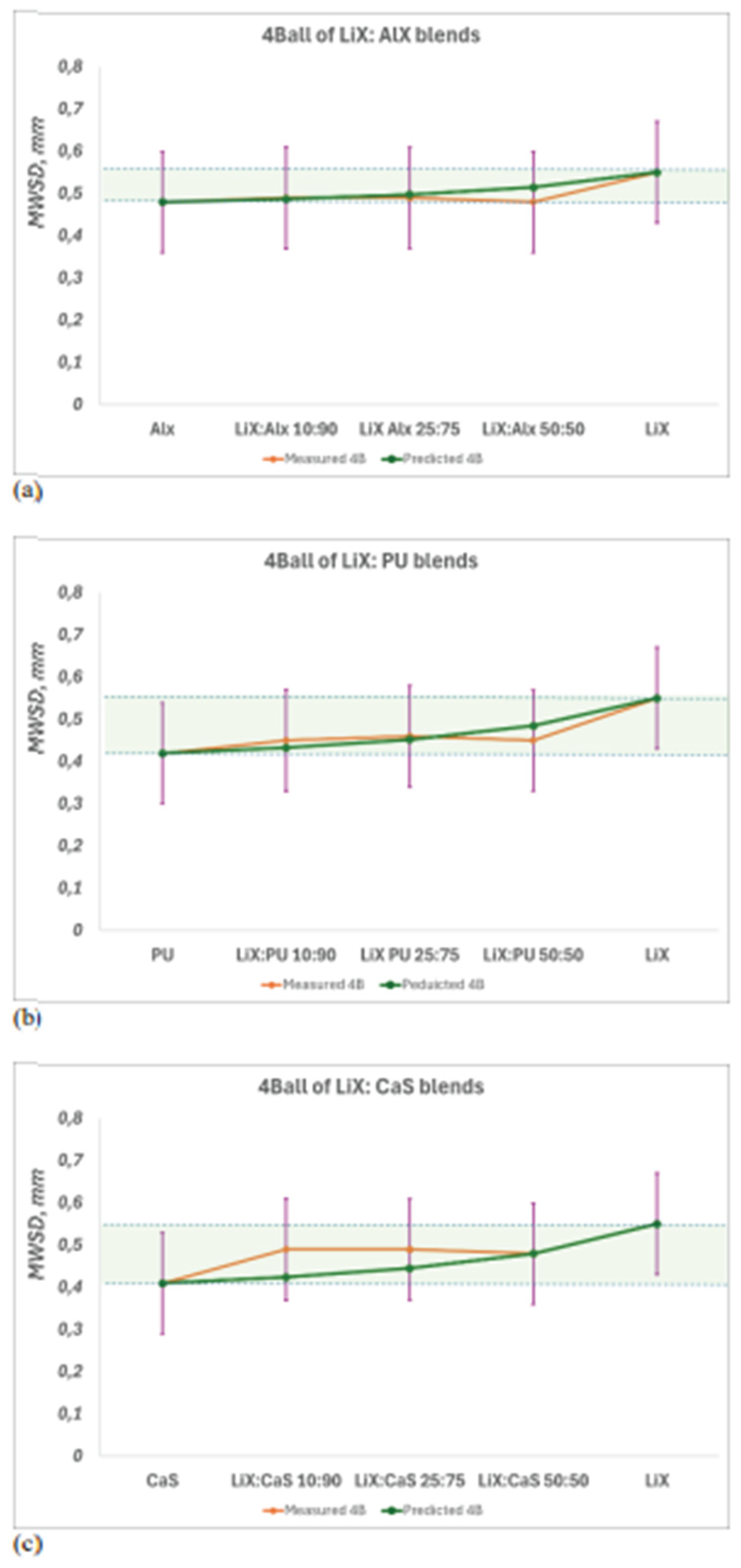

The three graphs in

Figure 5 give the actual measured and the predicted values of the mean wear scar diameter for each examined binary blend. Like what has been reported in the oxidation stability study, no adverse effect has been demonstrated on the metal sorption capability or on the ability of the blends to maintain a robust physicochemical structure in the anti wear performance test. That is to say that irrespective of any changes observed in the primary testing scheme, all the four ball results are acceptable and within the predicted compatibility limits for this specific protocol.

Grease Compatibility and Evaluation Methods Grease compatibility

—the ability of two lubricating greases to coexist without significant degradation in performance

—is a key concern when switching thickener chemistries. Historically, simple compatibility charts have classified grease pairs as “compatible,” “borderline,” or “incompatible” based solely on thickener type. In practice, such charts often conflict and can be misleading [

35,

36,

40]. This is because greases are complex formulations where not only thickener interactions but also base oil differences and additive chemistries can induce incompatibilities [

34,

35]. Two greases might share a thickener family yet behave very differently when mixed if, for example, one uses an ester base oil and the other a mineral oil, or if their additive packages interact adversely [

35]. Conversely, some grease combinations traditionally thought to be incompatible may prove acceptable with certain formulations. For instance, generic charts often warn against mixing lithium and calcium soap greases, yet commercial lithium-calcium mixed-soap greases perform reliably, underscoring that blanket statements by thickener type alone can be oversimplified [

36,

39]. True compatibility is best determined by direct testing rather than by generalization [

33,

35]. When due diligence is exercised

—e.g., gradual purging of old grease and monitoring

—even a changeover between very different greases can be managed without equipment damage in many cases [

38]. The literature thus emphasizes understanding the specific grease pair in question, rather than relying on one-size-fits-all rules [

34,

41].

4. Discussion

4.1. Grease Compatability and Evaluation Methods

Grease compatibility—the ability of two lubricating greases to coexist without significant degradation in performance—is a key concern when switching thickener chemistries. Historically, simple compatibility charts have classified grease pairs as “compatible,” “borderline,” or “incompatible” based solely on thickener type. In practice, such charts often conflict and can be misleading [

35,

36,

40]. This is because greases are complex formulations where not only thickener interactions but also base oil differences and additive chemistries can induce incompatibilities [

34,

35]. Two greases might share a thickener family yet behave very differently when mixed if, for example, one uses an ester base oil and the other a mineral oil, or if their additive packages interact adversely [

35]. Conversely, some grease combinations traditionally thought to be incompatible may prove acceptable with certain formulations. For instance, generic charts often warn against mixing lithium and calcium soap greases, yet commercial lithium-calcium mixed-soap greases perform reliably, underscoring that blanket statements by thickener type alone can be oversimplified [

36,

39]. True compatibility is best determined by direct testing rather than by generalization [

33,

35]. When due diligence is exercised—e.g., gradual purging of old grease and monitoring—even a changeover between very different greases can be managed without equipment damage in many cases [

38]. The literature thus emphasizes understanding the specific grease pair in question, rather than relying on one-size-fits-all rules [

34,

41].

4.2. Standard Testing (ASTM D6185) and Limitations

The ASTM D6185 standard practice provides a systematic protocol for evaluating binary grease compatibility [

17]. It involves blending the two candidate greases in various ratios (often 10:90, 50:50, and 90:10) and measuring key properties of the mixtures versus the neat greases. The primary tests specified include changes in consistency (worked penetration), thermal dropping point, and “storage stability” (often an oil separation or high-temperature leakage test) [

17,

18]. In ASTM D6185, a blend is deemed compatible if its 60-stroke worked penetration and extended worked penetration (e.g., 100,000 strokes or an equivalent roll stability test) remain within allowable variance of the component greases, and if the dropping point of the mixture is not significantly depressed [

17]. This baseline protocol effectively checks if the thickener matrix remains intact (no excessive softening or hardening) and if no gross thermal meltdown occurs in the mixture.

However, the standard has well-recognized limitations. Passing the basic penetration and dropping point criteria does not guarantee that all performance aspects are retained in the blend [

18,

19]. Grease performance involves other properties—load-carrying capacity, wear protection, oxidation stability, low-temperature flow, corrosion resistance, etc., which ASTM D6185’s primary tests do not cover [

17,

18]. For this reason, the standard itself allows for optional secondary tests as agreed upon by supplier and user [

17]. In practice, if two greases pass the basic D6185 criteria, it is often recommended to evaluate additional performance parameters of the mixture. For example, one might test the blend’s extreme-pressure (EP) and antiwear behavior, corrosion inhibition, or oxidation stability to ensure no critical property is compromised [

19].

In summary, ASTM D6185 provides a starting framework for grease compatibility evaluation, but it is not a full qualification of performance. Researchers and engineers have extended compatibility testing beyond D6185’s scope in recent years, especially for demanding applications [

20,

21].

4.3. Extended Compatability Testing: Oxidation and Wear Performance

Several studies highlight that greases which appear compatible with D6185 can still fail in service due to issues like accelerated oxidation or poor anti-wear performance [

19,

21]. One concern is high-temperature oxidative stability: mixing two greases can dilute or deactivate antioxidant additives, potentially lowering the blend’s resistance to oxidation compared to each grease [

21]. For example, Coe noted that even visually “compatible” greases showed unpredictable results in long-term thermal or mechanical testing due to additive interactions [

19,

20].

Similarly, wear and extreme-pressure performance of mixed greases may deviate from expectations. Grease formulations rely on synergistic additive packages (such as sulfur/phosphorus EP additives, or zinc-based anti-wear agents) to protect against scuffing and wear [

18,

19]. If two greases with different additive chemistries are blended, the additives can compete or form undesirable by-products, diminishing their effectiveness [

19,

23]. For this reason, several industry white papers and committee reports have advocated including ASTM D2266/D2596 (four-ball wear/EP tests) or similar tribological tests on grease blends that will be used in high-load applications [

2,

25].

In the present study, such extended testing was carried out, including oxidation stability and four-ball wear evaluations on lithium-based binary blends, to capture incompatibilities that basic consistency tests alone might miss. This approach aligns with industry recommendations that “functional performance properties of the grease remain acceptable” in any new grease mixture [

18,

21].

4.4. Influence of Thickener Chemistry, Base Oils, and Additives

Whether two greases are compatible often boils down to the interactions of their thickeners, oils, and additives. Thickener chemistry is usually the first consideration. Greases thickened with similar soap types (e.g., lithium 12-hydroxystearate vs. lithium complex) tend to have a higher likelihood of compatibility, whereas those with very different thickener structures (say, a urea polymer versus a metal soap) are more prone to interact adversely [

33,

34]. Incompatibility can manifest because the soap fibers or networks that solidify a grease may be dissolved or disrupted by a foreign thickener or its by-products [

28]. For example, polyurea thickeners (which are ashless, formed by reaction of amines and isocyanates) have a distinctly different polarity and structural format than metallic soap thickeners [

31]. Some polyurea greases might gel or soften when mixed with a lithium soap grease, or conversely, cause excessive hardening, depending on how the soap matrix and the urea complex interact [

26,

32]. However, it is important to note that “polyurea greases…vary significantly in both chemical structure and rheological properties,” so one cannot make a blanket statement that any polyurea will always be incompatible with any lithium grease [

31]. The specific urea chemistry (e.g., aliphatic vs aromatic urea, diurea vs tri-urea) and the particular lithium soap formulation will dictate the result [

32].

Aluminum complex greases, which use complexed aluminum soaps (often with benzoate or similar anions), generally have excellent water resistance and high dropping points, but when blended with lithium complex greases, results have been mixed [

33]. Field and lab studies have shown outcomes ranging from near compatibility to catastrophic softening, even within the same thickener pair category, highlighting that proprietary formulation differences (soap content, manufacturing process, etc.) can alter compatibility [

28]. Calcium sulfonate complex greases are another case: these greases are structurally different (containing calcite particles within a calcium sulfonate matrix) [

34]. They typically exhibit superb high-temperature and EP performance on their own. When mixed with lithium complex greases, some studies and field reports note slight consistency changes or oil bleed, but not all lithium–calcium sulfonate combinations are problematic [

24,

27]. Indeed, some grease manufacturers have reported lithium-calcium blends that remain stable, especially if a portion of the thickener systems are soap-compatible [

27]. As Willett observed, it would be “irresponsible to make a blanket statement” about polyurea or other grease compatibility without considering formulation specifics—a sentiment equally applicable to calcium and aluminum greases [

35].

Apart from thickener-thickener interaction, base oil compatibility plays a critical role. Greases carry 70–90% base oil, so if the oils are mismatched, the mixture can separate or thicken [

29,

30]. Certain synthetic base oils (e.g., polyalkylene glycols or silicones) are often not compatible with common mineral oils, and mixing greases with such base fluids may lead to phase separation or thickener swelling [

29,

32]. This can manifest as bleeding (oil syneresis) or consistency shifts in the blend [

28,

30]. In contrast, if two greases share similar base oil type and viscosity (say both use an ISO VG 220 mineral oil), the oil phase will readily mix and is less likely to upset the thickener structure [

24,

29].

Additive compatibility is the third factor. Grease additives (antioxidants, rust inhibitors, EP/AW agents, polymer thickeners, etc.) can interact in unexpected ways when two formulations are combined [

34]. Some additives can react with certain thickeners—for example, sulfur/phosphorus EP additive packages that work in lithium greases may chemically degrade a polyurea matrix, depending on the urea chemistry involved [

31,

32]. Indeed, literature examples show that polyurea and aluminum complex thickeners are not compatible with certain additive chemistries due to such degradation mechanisms [

30,

35]. Thus, a grease that relies on a particular additive might lose performance if that additive is neutralized by the other grease’s chemistry.

One practical diagnostic mentioned in industry literature is to use FTIR spectroscopy on a 50:50 grease mixture to see if any new chemical species or degradation products appear—a sign that an adverse reaction may be occurring between constituents [

28]. In sum, the degree of compatibility is a function of the total formulation. A successful combination of greases requires not just matching thickener types, but also ensuring the base oils are miscible and the additive packages do not counteract each other [

29,

34]. These considerations explain why the present study’s results may show certain lithium complex/alternative grease pairs faring better than others: the lithium–calcium sulfonate blend, for instance, might remain relatively stable if the oils and additives are similar, whereas the lithium–polyurea blend could falter if the urea thickener and lithium soap do not form a cohesive network [

26,

27,

31].

4.5. Literature Findings vs. Current Results: Thermal, Shear, and Oxidation Behavior

Prior research into binary grease mixtures provides a context for interpreting the trends observed in this study. A consistent theme is that mixing greases can significantly alter their high-temperature and mechanical stability metrics. Thermal stability, often gauged by the dropping point or evaporation loss, is usually compromised when greases are incompatible. In thermal analysis of grease mixtures with incompatible thickener systems, all tested blends commonly exhibit a reduced dropping point compared to the original greases, sometimes failing the criteria established by ASTM D6185 [

28,

37]. This indicates that even though both thickener types individually may have high drop points (e.g., >250 °C), their mixtures can melt or become fluid at appreciably lower temperatures. A likely explanation is disruption of the thickener lattice: the inter-fiber interactions that confer thermal tolerance in each grease are weakened in the presence of the other thickener [

28]. The present work, which examines lithium complex grease blended with three different thickener classes, allows similar comparisons. Blends with calcium sulfonate complex grease would be expected to show the highest thermal resilience (since calcium sulfonate greases often have drop points well above 300 °C), whereas blends with a polyurea grease might show a greater drop point depression if incompatibility occurs [

37]. Published data on lithium–polyurea mixtures is limited, but some suppliers anecdotally classify that pairing as high-risk for drop point and texture failure [

36]. On the other hand, successful lithium–calcium mixed greases (as used in some commercial products) suggest that a lithium/calcium combination can maintain thermal stability if properly formulated [

36,

37].

In terms of shear stability (mechanical stability), literature shows that grease mixtures can harden or soften unpredictably. Compatibility testing often measures the change in working penetration after prolonged working (e.g., 100k strokes or roll stability). For instance, testing across lithium/aluminum mixtures has shown penetration changes ranging from mild hardening to extreme softening, suggesting that consistency is highly sensitive to network compatibility and possible thickener breakdown [

36]. Such a wide range demonstrates how formulation nuances (e.g., dilution of a tackifier polymer or interaction with an incompatible soap) can dictate outcomes [

28]. These findings align with earlier observations that grease consistency is very sensitive to thickener network integrity [

28,

40]. If two soaps are structurally incompatible, the work penetration of their blend can be far outside the bounds of either grease alone. In the present study’s results, a similar pattern is likely: one or two of the lithium-based blends show relatively small penetration changes (indicating the thickeners reinforced each other or at least did not collapse), whereas other blends may exhibit large consistency loss or gain. Notably, even when a 50/50 mixture passes a 60-stroke penetration test with only mild change, it is prudent to also examine prolonged shearing effects [

36]. A mixture that initially looks firm could degrade after extended mechanical stress or high-temperature storage. This is why our discussion integrates both immediate (worked penetration) and longer-term (prolonged work or storage) stability in evaluating compatibility [

28,

40].

Oxidation resistance of grease mixtures is less documented in literature, but it is an important aspect, particularly for high-temperature or long-life applications. Grease oxidation stability is typically ensured by antioxidant additives (amines, phenols, etc.) and by the inherent thermal robustness of the thickener [

37]. If one grease is well-fortified with antioxidants and the other is not, a 50:50 blend may effectively halve the concentration of inhibitors, potentially shortening the oxidation induction time of the mixture [

38,

39]. Moreover, some grease thickeners (like calcium sulfonate) confer a degree of inherent oxidation resistance due to their alkaline nature, while others (e.g., lithium soap) do not [

37]. Although ASTM D6185 does not account for this, researchers have noted that a grease blend’s oxidative life can diverge substantially from that of its constituents [

38]. For example, FTIR-based analysis has been used to track oxidation degradation pathways and identify chemical species formed during stress testing of mixed greases [

38,

39]. Thus, any suspected incompatibility should be verified by oxidation testing (e.g., bomb oxidation or pressure DSC), particularly in applications sensitive to varnishing or deposit formation [

37,

38]. In this work, the authors extended compatibility evaluation to include oxidation stability measurements of the lithium grease blends. A point of convergence with literature is anticipated here: blends that were deemed incompatible by consistency tests likely also show poorer oxidation stability (e.g., faster pressure drop in an oxidation bomb test) compared to the fully compatible blend [

37,

39]. Any divergence—for example, a blend that marginally failed a penetration criterion but still exhibits strong oxidative stability due to a robust antioxidant package—would be an interesting finding to contrast with the normative expectation that incompatibility generally worsens all aspects of performance. In practical terms, confirming that a grease mixture retains adequate oxidation life and antiwear protection is crucial before it can be approved as a drop-in replacement in the field [

36,

40]. The literature thus reinforces the multi-faceted approach taken in the current study’s Results and Discussion: evaluating not just one property but the overall performance profile of grease blends relative to known benchmarks [

36,

37,

40].

4.6. Industry Trends Driving Lithium Replacement

The backdrop for this research is an industry-wide push to find viable alternatives to lithium-based greases. Lithium soap and lithium complex greases have long dominated the market—as of the early 2020s, they still account for roughly 60–70% of global grease production [

41]. This dominance is due to their historically excellent performance and versatility: lithium greases offer a stable fiber structure, good high-temperature properties, water resistance, and compatibility with many base oils and additives [

43,

44]. However, several converging factors are motivating a transition away from lithium-thickened products.

Supply and Economics: Lithium demand from the battery sector has raised concerns about cost and availability for grease manufacturers [

41,

42]. While lithium itself is abundant, refining it into lithium hydroxide for grease thickener is challenging and resource-intensive. In recent years, lithium prices spiked dramatically (reaching historic highs in 2022), and although they had settled by mid-2024, the volatility highlighted the risk of over-reliance [

41,

47]. Grease producers, especially in regions without local lithium sources, have faced supply disruptions and increased raw material costs, spurring interest in more readily available thickeners [

42,

47].

Environmental and Sustainability Factors: The mining and processing of lithium (especially from hard rock minerals like spodumene) carry a significant environmental footprint, including high energy use, substantial water consumption for brine extraction, and a large carbon footprint per ton of lithium [

42,

46]. By contrast, some alternative thickener materials—for example, simple calcium hydroxide used in making calcium-based greases—are far less energy-intensive to produce, with one analysis indicating an order of magnitude lower greenhouse gas emissions for calcium feedstock versus lithium [

42]. Although lithium-based greases themselves are not toxic in service, the upstream impacts and the disposal considerations are increasingly scrutinized under sustainability goals [

43].

Health and Regulatory Drivers: A recent development putting pressure on lithium greases is the regulatory reclassification of lithium compounds. Lithium hydroxide (a key ingredient in lithium soap manufacturing) has been classified by the European Chemicals Agency (ECHA) as a Category 1 reproductive toxin [

41,

46]. This classification (for effects on fertility and development) triggers stricter labeling, handling, and exposure limits for products containing free lithium hydroxide. While finished greases typically contain only low levels of free LiOH, manufacturers must ensure those levels stay below certain thresholds or face hazard labeling requirements [

22,

46]. In some jurisdictions, lithium hydroxide is even listed as a hazardous substance outright, complicating its use. These health and compliance concerns are driving grease companies to “consider lithium thickener alternatives as soon as possible” to avoid future regulatory burdens [

41,

46].

In response to these drivers, the grease industry has been actively exploring and adopting alternative thickener technologies. Calcium-based greases are seeing a resurgence: for instance, new anhydrous calcium soap greases and calcium complex greases have been developed that can rival lithium greases in performance (with dropping points and operating temperatures in a similar range, plus enhanced water resistance) [

43,

45]. Calcium sulfonate complex greases, already valued for their high-temperature and load-carrying prowess, are being promoted as lithium complex replacements in many industrial applications—they offer excellent thermal stability and inherent EP performance, though their mechanical stability and pumpability at low temperature must be managed in certain bearing applications [

41,

45].

Polyurea greases are likewise gaining attention as high-performance alternatives, especially for sealed-for-life automotive and electric motor bearings [

42,

44]. Urea-thickened greases can deliver equal or better bearing life compared to lithium complexes, owing to their oxidative stability and film strength, and recent formulations have addressed some historical limitations (like improving their rust protection and reducing shear thickening) [

44,

45]. Aluminum complex greases, too, are considered in niches where their particular strengths (very good water washout resistance and oxidative stability) are advantageous [

43,

45]. Each of these alternatives comes with its own manufacturing and compatibility considerations—for example, polyurea greases require handling toxic isocyanates during manufacture, and calcium sulfonate greases demand precise process control—but they are increasingly viable at commercial scale [

41,

45]. Notably, many large grease suppliers have already adjusted product lines to include lithium-free offerings in anticipation of future constraints [

41,

44].

The ongoing “lithium crisis” discussions have reinforced that finding a “widely available, reliable, and consistent alternative” is one of the most pressing challenges for the grease industry today [

41]. This context underlines the importance of studies on grease compatibility, such as the present work. As end-users begin switching from ubiquitous lithium greases to these alternative-thickener greases, there will inevitably be periods of mixing, whether during relubrication changeovers or in central lubrication systems that cannot be perfectly purged [

45]. Understanding the compatibility limits of lithium greases with the leading alternatives (polyurea, aluminum complex, calcium sulfonate complex) is thus both scientifically and practically significant. The literature provides guidance (and some cautionary tales) on what to expect when these greases meet [

42,

43]. The results of this study contribute to that body of knowledge by pinpointing where performance converges with prior expectations and where surprising divergences occur, all in light of the industry’s broader transition away from lithium-based formulations.

5. Conclusions

In this study, an effort was made to examine the potential compatibility limits of different greases by preparing binary blends in various mixing ratios that simulate a change over from a lithium complex (LiX) grease to either an aluminum complex (AlX), a polyurea (PU) or a calcium sulfonate complex grease (CaSX) in any hypothetical application. For each one of the three combinations, three different mixing ratios were applied (10:90, 25:75 & 50:50) that resemble the ratios of the two greases that remain after an attempt to either flush or not the original grease from the equipment. A total of nine samples along with the four individual neat greases were examined per a series of primary (dropping point, shear stability, high temperature storage stability) and secondary (oxidation stability and antiwear performance) test methods as per ASTM D6185. The assessment of the potential compatibility of the binary blends was judged based on both the ASTM definitions, as well as based on literature available acceptable limits from practice. Table 5 summarizes the outcome of this evaluation by utilizing a traffic-light approach for signifying compatible, borderline and non-compatible combinations.

According to the official definition of compatibility in the ASTM methodology, a binary blend is considered non-compatible in the case that it fails at least in one of the primary test methods. In that strict sense, the only sample that fulfills the compatibility requirements in this study is the 10:90 LiX:PU blends. In a broader and more general sense LiX:PU proved to be the most effective/compatible combination with only three out of nine blends judged as noncompatible. The LiX:AlX blends follow with five non-compatible binary mixtures , while the combination of LiX and CasX appears to be the more challenging in terms of compatibility since six of the respective blends are non-compatible per ASTM. By assessing the results according to LCL definitions, that are more generous, then it proves that all combinations can be compatible even marginally only with the exception of LiX:CaSX when dropping point comes into question. No adverse effect has been detected on oxidation stability and antiwear performance irrespective of the blending ratio and the type of grease involved which appears to be a positive finding in terms of additives compatibility and the overall structure related capability to lubricate under boundary lubrication regime. Further studies are carried out in order to extend the present work by evaluating the binary blends on secondary tests after high temp storage stability and by analyzing the compatibility interactions between the binary blends and the equipment materials. Moreover, the effect of the variation in the composition of a single thickener grease type is examined.

Per the findings of the study, alternatives to lithium complex greases can be applied but caution should be exerted when switching from one chemistry to another and extra attention should be given even to those types that are frequently advertised as being compatible. It should be noted that the results of this study, though significant in terms of the interchangeability potential between LiX and other thickener chemistries, they are—up to an extent—dependent on the characteristics of the certain grease products that were selected and examined in this study. Also, the relative acceptance limits play a significant role in the overall judgment. Grease compatibility testing is a challenging multi-dimensional task and all greases within a single thickener type may not perform identically in the testing scheme, due to complexing agent differences or potential additive incompatibility for example. On the other hand, the grease compatibility charts are generic and should be used with due diligence. As a rule, the application operating conditions and the equipment’ guidelines should be considered while a thorough compatibility investigation should be conducted when in doubt, to ensure improved operational efficiency and reduced maintenance costs.

Finally, due to the complex nature of grease compatibility, an update of the compatibility methodology appears to be reasonable and should encompass a more dynamic approach by designating specific secondary protocols and taking into consideration the visual observations—evaluation, as well.

Author Contributions

Conceptualization, R.S. and G.D.; methodology, R.S.; software, M.L.; validation, R.S., G.D., and M.L.; formal analysis, R.S., M.L.; investigation, R.S., G.D., and N.K.; resources, G.D., N.K. .; data curation, G.D., N.K.; writing—original draft preparation, R.S., M.L., and P.M.; writing—review and editing, R.S., M.L., and P.M.; visualization, R.S., M.L., and P.M.; supervision, R.S., G.D. and N.K.; project administration, R.S., G.D. and N.K.; All authors have read and agreed to the published version of the manuscript.

Funding

This research received no external funding.

Data Availability Statement

The original contributions presented in this study are included in the article/supplementary material. Further inquiries can be directed to the corresponding author(s).

Conflicts of Interest

Rajesh Shah is currently employed by Koehler Instrument Company, Inc. George Dodos and Nora Kaframani were employed by ELDON’S S.A. at the time of data collection. The remaining authors declare that the research was conducted in the absence of any commercial or financial relationships that could be construed as a potential conflict of interest.

Abbreviations

The following abbreviations are used in this manuscript:

| LiX |

Lithium Complex Grease |

| AlX |

Aluminum Complex Grease |

| PU |

Polyurea Grease |

| CaSX |

Calcium Sulfonate Complex Grease |

| ASTM |

American Society for Testing and Materials |

| NLGI |

National Lubricating Grease Institute |

| wt% |

Weight Percent |

| VG |

Viscosity Grade |

| PAO |

Polyalphaolefin |

| FTM |

Federal Test Method |

| RSSOT |

Rapid Small Scale Oxidation Test |

| DP |

Dropping Point |

| HTSS |

High Temperature Storage Stability |

| RS |

Roll Stability |

| EP |

Extreme Pressure |

| AW |

Anti-Wear |

| LCL |

Literature Compatibility Limits |

| FTIR |

Fourier Transform Infrared Spectroscopy |

References

- Shah, R.; Tuszynski, W. (2021). Lubricating Greases Guide. NLGI.

- Coe, C. , (2019) Grease Compatibility Charts are Dangerous! Presented at the 86th NLGI Annual Meeting, Las Vegas, Nevada.

- Aikin, A.R. Grease compatibility. Tribology & Lubrication Technology 2023, 79, 44–46. [Google Scholar]

- ASTM D6185-11(2017), Standard Practice for Evaluating Compatibility of Binary Mixtures of Lubricating Greases.

- Coe C (2024) NLGI Grease Production Survey Report, Presented at the 91st NLGI Annual Meeting, San Antonio, Texas.

- Fish, G., (2024), High Performance Alternatives to Lithium Greases, Presented at 34th ELGI AGM, Madrid, Spain.

- Leckner, J., (2024) Can Calcium Limit Lithium Reliance?, Presented at 34th ELGI AGM, Madrid, Spain.

- Meijer, R.J.; Lugt, P.M. The grease worker and its applicability to study mechanical aging of lubricating greases for rolling bearings. Tribology Transactions 2021, 65, 32–45. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Meijer, R.J.; Osara, J.A.; Lugt, P.M. On the required energy to break down the thickener structure of lubricating greases. Tribology Transactions 2024, 67, 123–128. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Channeling behavior of lubricating greases in rolling bearings: Identification and characterization.

- Fed. Test Method Std. No. 791c (1986), Federal Test Method Standard, Lubricants, Liquid Fuels, And Related Products; Methods Of Testing.

- Hurley, S.; Cann, P.M.; Spikes, H.A. (1998). Thermal degradation of greases and the effect on lubrication performance. In Tribology Series (Vol. 34, pp. 75–83). Elsevier.

- Booser, R.; Khonsari, M. Grease life in ball bearings: The effect of temperatures. Tribology & lubrication technology 2010, 66, 36–44. [Google Scholar]

- Dodos, G.S., “Study on a New Oxidation Stability Method for Lubricating Greases by Employing the Rapid Small Scale Oxidation Test,” NLGI Spokesman 81, no. 5 (Nov/Dec 2017).

- Dorinson, A. The nature of the wear process in the four-ball lubricant test. wear 1981, 68, 109–127. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Chandrasekaran, S.; Khemchandani, M.V.; Sharma, J.P. Studies on the boundary lubrication regime in a four-ball machine. Wear 1985, 105, 145–152. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- ASTM International. ASTM D6185-11 (Reapproved 2017): Standard Practice for Evaluating Compatibility of Binary Mixtures of Lubricating Greases. ASTM International, West Conshohocken, PA, 2017.

- National Lubricating Grease Institute (NLGI). Lubricating Grease Guide, 5th Edition; NLGI: Kansas City, MO, USA, 2020.

- Coe, C. Grease Compatibility Charts Are Dangerous! NLGI Spokesman 2020, 84, 6–22. [Google Scholar]

- Coe, C. Contradictory Compatibility. Lubes’N’Greases Magazine 2019, 25, 20–24. [Google Scholar]

- Honary, L.A. Grease Compatibility for Biobased-Biodegradable Greases. Lube Magazine (UK) 2021, 161, 36–39. [Google Scholar]

- Miller, D. Incompatible Greases Could Lead to Costly Repairs. DTN/The Progressive Farmer (MachineryLink Blog), April 17, 2018.

- Allum, K.G.; Jackson, A. The Compatibility of Lubricating Greases. Tribology Transactions 1988, 31, 214–221. [Google Scholar]

- Turner, D. Grease Compatibility Chart and Reference Guide. CITGO Petroleum Technical White Paper, 2018.

- NLGI Lubricating Grease Working Group. Grease Compatibility—Problem and Progress. NLGI Spokesman 1991, 55, 18–25. [Google Scholar]

- Ren, G.; Zhang, P.; Ye, X.; Li, W.; Fan, X.; Zhu, M. Comparative Study on Corrosion Resistance and Lubrication Function of Lithium Complex Grease and Polyurea Grease. Friction 2021, 9, 75–91. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Ren, G.; Zhang, P.; Li, W.; Fan, X.; Zhang, L.; Li, H.; Zhu, M. Probing the Synergy of Blended Lithium Complex Soap and Calcium Sulfonate towards Good Lubrication and Anti-Corrosion Performance. Tribology Letters 2020, 68, 99. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Conrad, A.; Hodapp, A.; Hochstein, B.; Willenbacher, N.; Jacob, K.-H. Low-Temperature Rheology and Thermoanalytical Investigation of Lubricating Greases: Influence of Thickener Type and Concentration on Melting, Crystallization and Glass Transition. Lubricants 2022, 10, 1. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Wang, J.; Guo, Z.; Hu, W.; Lu, H.; Li, J. Investigating the Effects of Base Oil Type on Microstructure and Tribological Properties of Polyurea Grease. Tribology International 2024, 194, 109573. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Shah, R.; Tung, S.C.; Chen, R.; Miller, R. Grease Performance Requirements and Future Perspectives for Electric and Hybrid Vehicle Applications. Lubricants 2021, 9, 40. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Ren, G.; Sun, X.; Li, W.; Li, H.; Zhang, L.; Fan, X.; Li, D.; Zhu, M. Improving the Lubrication and Anti-Corrosion Performance of Polyurea Grease via Ingredient Optimization. Friction 2021, 9, 1077–1097. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Lyadov, A.S.; Kochubeev, A.A.; Parenago, O.P. Synthesis and Properties of Polyurea Greases Based on Silicone Fluids and Poly-α-olefin Oils. Petroleum Chemistry 2023, 63, 618–623. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Mang, T.; Dresel, W. (Eds.) Lubricants and Lubrication, 3rd Edition; Springer: Berlin, Germany, 2017.

- Totten, G.E. (Ed.) Handbook of Lubrication and Tribology, Volume 1: Application and Maintenance, 2nd Edition; CRC Press: Boca Raton, FL, USA, 2017.

- Willett, E. Willett, E. The Mechanical Stability of Polymer-Modified Greases. Paper presented at the 87th NLGI Annual Meeting (Virtual Conference), 2020.

- Shekhawat, D.; Jain, A.; Vashishtha, N.; Singh, A.P.; Kumar, R. Tribological Performance Comparison of Lubricating Greases for Electric Vehicle Bearings. Lubricants 2025, 13, 108. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Krasodomski, W.; Skibińska, A.; Żółty, M. Thermal Oxidation Stability of Lubricating Greases. Advances in Science and Technology Research Journal 2020, 14, 76–83. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Azad, S.; Evans, G. A Comparative Study of Grease Oxidation Using Traditional and Advanced FTIR Techniques. NLGI Spokesman 2018, 82, 26–33. [Google Scholar]

- Fox, M.; Hunt, T. An Advanced Technique for Grease Oxidation Measurement. NLGI Spokesman 2018, 82, 15–21. [Google Scholar]

- Cann, P.M.E.; Lubrecht, A.A. Grease Lubrication: Formulation Effects on Tribological Performance. Tribology International 2013, 61, 14–23. [Google Scholar]

- Fish, G.; Hsu, C.; Dura, R.; McCune, D. Six Years On—An Update on Navigating the Lithium Crisis. NLGI Spokesman 2024, 88, 12–19. [Google Scholar]

- Deshmukh, V. The Hunt for Lithium Alternatives. Lubes’N’Greases Magazine 2018, 23, 28–30. [Google Scholar]

- Carroll, J.; Black, A. Lithium Loosens Its Grip on Grease. Lubes’N’Greases Magazine 2020, 26, 22–25. [Google Scholar]

- Shiller, P. The Future of Lithium Greases. Tribology & Lubrication Technology 2020, 76, 20–22. [Google Scholar]

- Morris, W. An Update on Lithium-Based Greases. Tribology & Lubrication Technology 2020, 76, 34–37. [Google Scholar]

- Kumar, A. Ask the Expert: Is it Time to Ditch Lithium Grease?” Machinery Lubrication (Noria Corporation), July 2018.

- McCabe, J. Improving Grease Performance Amid Thickener Supply Squeeze. OEM Off-Highway Magazine, March 2019.

|

Disclaimer/Publisher’s Note: The statements, opinions and data contained in all publications are solely those of the individual author(s) and contributor(s) and not of MDPI and/or the editor(s). MDPI and/or the editor(s) disclaim responsibility for any injury to people or property resulting from any ideas, methods, instructions or products referred to in the content. |

© 2025 by the authors. Licensee MDPI, Basel, Switzerland. This article is an open access article distributed under the terms and conditions of the Creative Commons Attribution (CC BY) license (http://creativecommons.org/licenses/by/4.0/).