Introduction

The mRNA-containing lipid nanoparticle (mRNA–LNP)-based COVID-19 vaccines, Pfizer’s Comirnaty and Moderna’s Spikevax, played a crucial role in mitigating the severity of SARS-CoV-2 infections and saving lives during the pandemic. Since their introduction, >5 billion doses were administered worldwide, and despite the subsiding of the pandemic, these vaccines remained the primary tool for maintaining immunity against circulating SARS-CoV-2 variants. However, as of May 2025, the CDC has revised its recommendations, limiting the use of COVID-19 mRNA vaccines and number of boosters mainly to high-risk populations. Several countries and regions had already restricted their use, partly due to the declining threat of the virus, and partly in response to increasing concern over the uniquely broad spectrum and relatively high incidence of adverse events (AEs) compared to traditional vaccines [

1]. However, as of May 2025, the CDC has revised its recommendations, limiting the use of COVID-19 mRNA vaccines and boosters mainly to high-risk populations. Several countries and regions had restricted their use earlier, partly due to the declining threat of the virus, and partly in response to increasing concern over the uniquely broad spectrum and relatively high incidence of adverse events (AEs) compared to traditional vaccines.

Although such AEs are statistically rare on an individual basis (officially reported at 0.03–0.5%) [

1], the vast scale of global vaccination campaigns has resulted in a significant absolute number of vaccine-related injuries. These adverse outcomes have been collectively described as post-vaccination syndrome (PVS) [2-7], a newly recognized condition affecting millions worldwide, including individuals with persistent health issues or disabilities that may qualify as an iatrogenic orphan disease [

1]. In some cases, simultaneous inflammation of multiple organs can occur, leading to a highly lethal condition known as multisystem inflammatory response syndrome.

The objective of this review is to investigate the role of endothelial cells (ECs) within the microcirculation as a likely primary site of vaccine-induced injury. A better understanding of these processes is essential for improving the safety, and thereby the future success, of mRNA–LNP platform technology, not only for vaccination but for other therapeutic purposes.

2. The mRNA–LNP-induced Inflammatory Complications and their Root Cause

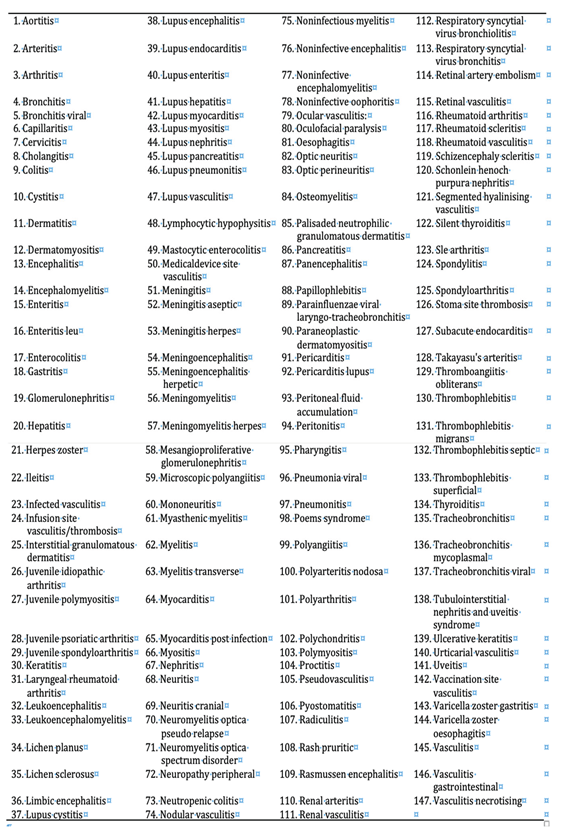

Table 1 shows a list of organs whose inflammation was reported in the publicly available 3-month safety surveillance report of Pfizer [

8]. The advantage of using these data is that the list of AEs likely excludes symptoms caused by SARS-CoV-2 infection, as the vaccine had not been administered to infected individuals. Also, the list was compiled from data in 52 countries, arguing against bias. The list was compiled by AI searching in the report for words containing the ”itis” tag, and then screening out the redundant entries with a qualifying term, such as “acute, chronic, (auto)immune, immune-bacterial”, etc). Thus, the list does not distinguish among inflammatory conditions due to bacterial, viral infections or autoimmune attack, acute or chronic inflammations, it just shows that essentially all organs can be inflicted with a form of inflammation starting sometimes within 3 months after vaccination.

The similar kinetics of vaccine-induced inflammatory AEs listed in

Table 1 (developing within days or much later, in months after vaccination) and numerous commonalties in these illnesses, such as the association with reactivation of certain viral strains (

Table 2), point to a common, very fundamental immune abnormality or combination of abnormalities. A recent comprehensive hypothesis on this conundrum attributes the phenomenon, at least in part, to plausible consequences of inherent structural and functional properties of the mRNA–LNP platform [1, 9]. The design challenges include ribosomal synthesis of the SP, which fundamentally alters antigen processing and presentation; extensive chemical modification of the mRNA, rendering SP translation poorly controllable; the use of a proinflammatory, fusogenic aminolipid in the LNP, which promotes widespread systemic distribution and transfection of non-target cells to produce a toxin; the chemical stabilization of the SP, despite its known pluritoxicity; the choice of LNP lipid composition with reduced nanoparticle stability in aqueous environments; the PEGylation of the LNP surface, despite PEG’s known immune reactivity and immunogenicity; and recombinant production of the mRNA, which carries a risk for DNA contamination. These features collectively predispose to collateral tissue damage caused cytotoxic T cell and complement-mediated autoimmune responses. Although nucleoside modifications (e.g., pseudouridine substitution) of the mRNA reduce recognition by innate immune sensors, such as TLR3, TLR7, TLR8, and retinoic acid-inducible gene I (RIG-I) [10-14], residual activation of innate immunity by the modified mRNA via RIG-I-like receptors, under certain conditions, remains an open question [

15].

Given the multicausal and multiorgan nature of vaccine-induced inflammation, numerous pathological processes are likely involved. This review focuses on microcirculatory inflammation as a central driver of inflammatory AEs. The task is complicated by tissue-specific differences in microcirculatory structure and function, as described below.

Components and Unique Organization of Microcirculation Across Tissues

The microcirculation refers to the smallest blood vessels in the body (below ~200 micrometer), including arterioles, capillaries, and venules which collectively responsible for gas and nutrient exchange, waste removal, and immune surveillance at the tissue level. Some morphological features of cells in the microcirculation are illustrated in

Figure 1.

Endothelial cells (Fig 1B), which line the inner surface of all blood vessels, play a pivotal role in maintaining vascular homeostasis by regulating blood flow by modifying the tone of underlying smooth muscle, barrier function, coagulation, and immune cell trafficking, and so on. A crucial component of the ECs is the glycocalyx, a gel-like, carbohydrate-rich layer that lines the luminal surface of endothelial cells and other cell types. It is composed mainly of glycoproteins, proteoglycans (e.g., syndecans, glypicans), and glycosaminoglycan chains such as heparan sulfate and hyaluronic acid. It acts as a selective permeability barrier, sensing and modulating shear stress signaling, and preventing adhesion of leukocytes and platelets under physiological conditions (10). The connections among ECs can be continuous (tight junctions), fenestrated (pores in ECs), and discontinuous (large gaps between cells), each specialized for different organ systems (

Figure 1C and D).

4. Endothelial Cells in the Frontline of Vaccine-Induced Inflammation

The ECs are particularly responsive to inflammatory stimuli and are often the first point of contact for systemically circulating immune mediators and nanoparticles, including mRNA-LNPs. Damage to the glycocalyx, and, hence, endothelial integrity, can precipitate secondary cascades such as coagulation, C activation, immune cell infiltration, all of which contribute to various pathophysiological states, including inflammation, sepsis, ischemia-reperfusion injury, and vascular complications related to infections and vaccinations [

25]. The manifestations of symptoms and illnesses vary widely across organs, reflecting not only differences in immune responses but also organ-specific anatomical factors, discussed below.

5. Distinctive Microcirculatory Architectures Across Organs and Their Impacts on Vaccine-Induced Inflammations

Although all organs share a fundamental microvascular blueprint, the microcirculatory networks vary significantly in the density of the capillary network (Fig 1A), endothelial subtypes (

Figure 1B), tightness of intercellular junctions (

Figure 1C), and capillary fenestration type (

Figure 1D). Likewise, the local regulatory mechanisms that involve adjacent tissue cells, such as pericytes in nerve fibers, smooth muscle cells, precapillary sphincters, or other resistance mechanisms that govern blood flow in accordance with the functional demands on blood supply [

26]. These structural and functional variations render the microcirculation a highly specialized, tissue-specific interface between the bloodstream and parenchymal cells. Consequently, they critically influence the nature and extent of inflammatory responses. In particular, the localization or systemic spread of the SP is strongly governed by the microanatomy of the vasculature in the affected organs.

For example, the heart’s microcirculation is uniquely organized, characterized by an exceptionally dense capillary network providing nearly a one-to-one capillary fiber ratio allowing fast diffusion of and exchange of gases and nutritional molecules (

Figure 2A). The surface cardiomyocytes are covered with the epicardium, the inner layer of pericardium. The pericardium contains pericardial fluid, which can also be affected by inflammation [27-29]. The anatomical proximity, involving a high-density capillary network within the microcirculation, provides a structural basis for the frequent co-occurrence of pericarditis and myocarditis, a condition referred to as myopericarditis [30-32].

In the brain, ECs in non-fenestrated capillaries are connected by tight junctions, forming the blood–brain barrier, which strictly regulates molecular and cellular trafficking (

Figure 2B). This anatomical configuration is consistent with the emergence of localized inflammatory processes, underlying epileptic, cognitive and other focal AEs, for example optic neuritis, Guillain–Barré syndrome, facial paresis, etc. [

33]. The localized, restrained inflammation also helps explain the functional neurological disorders which are characterized by neurological symptoms without detectable abnormalities upon imaging with MRI or CT [33-35]. The situation is similar in the spinal cord, for example in transverse myelitis, which entails localized motor, sensory, and autonomic dysfunction.

In peripheral nerves, the endoneurium, which encases the individual nerve fibers (axons) along with their myelin sheath, contains an extensive network of capillaries also with tightly bound ECs (Fig 2C). Here, too, the inflammatory signals spread locally, along the axons and the perineurial and epineurial tissue, leading to demyelinating neuritis of different afferent or efferent nerves.

In the lung, the microcirculation comprises an extensive and highly permeable capillary network that lies in close association with the alveolar epithelium (

Figure 2D). This anatomical arrangement facilitates the transmission of inflammatory signals to both type I squamous epithelial cells and type II secretory cells, leading to widespread inflammatory involvement of the respiratory tissue. Consequently, typical manifestations of vaccine-induced inflammatory adverse events in the lung include alveolar infiltrates accompanied by respiratory distress, such as dyspnea, chest tightness, and hypoxia. [36, 37].

In the kidney, the microcirculation consists of two distinct capillary networks: glomerular capillaries, which form high-pressure filtration units, and peritubular capillaries, which surround the renal tubules and facilitate selective reabsorption and urine concentration within the nephron (Fig 2E). Inflammation of the ECs in both types of capillaries explain the nephrotic syndrome characteristic of vaccine injury, manifested in acute onset edema, hypoalbuminemia, and heavy proteinuria [38, 39].

In the liver, the microcirculation is organized into sinusoidal capillaries with a discontinuous endothelium, allowing free distribution of inflammatory mediators among the blood and hepatocytes. Accordingly, the symptoms of vaccine-induced hepatitis reflect common hepatocyte dysfunction, manifested in acute cholestatic liver injury (biliary obstruction), abdominal pain, pruritus, fever, fatigue, anorexia, nausea and vomiting, laboratory deviations, occasionally fatal outcome in patients with preexisting liver disease [40-44].

Given this diversity of AEs in different organ systems, the impact of endothelitis must be tissue-specific, likely responsive to targeted anti-inflammatory therapies.

6. The Journey of mRNA-LNPs from the Deltoid Muscle to the Sites of Inflammations

Intramuscular injection of mRNA–LNP-based vaccines is generally associated with immediate interaction with antigen-presenting cells (APCs) and other immune cells at the injection site and within the draining lymph nodes. These locations are considered the primary sites for T and B cell priming and have remained the central focus of most narratives concerning the immune mechanisms of mRNA-based vaccines [45-48]. However, it is well established that LNPs injected intramuscularly rapidly distribute throughout the body, reaching various non-immune organs and cell types, many of which can take up the nanoparticles.

Three main mechanisms have been proposed to explain how mRNA-LNPs gain access to the blood. One is an accidental, direct injection into a small vessel. Because the standard immunization protocol does not require aspiration or needle retraction prior to injection [

49], inadvertent intravenous administration and fast entry of vaccine into the brachial vein may occur, particularly in regions with dense capillary networks, such as the deltoid muscle. Second, entry via the lymphatic system [

50], which may start through the blind-ended portions of lymphatic vessels, which are leaflet-like endothelial structures that open in response to increased interstitial pressure (Fig 1A). The 300 µL bolus of vaccine can transiently and locally raise tissue pressure above the typically low pressure within lymphatic vessels, promoting nanoparticle entry. Once inside the lymphatic network, rhythmic contractions and relaxations of the lymphatic walls propel the nanoparticles centrally through valve-separated chambers and lymph nodes [51-54]. High-speed video lymphoscintigraphic measurements showed the velocity of lymph flow in the ~2-9 mm/s range, which implies that the vaccine nanoparticles reach the ductus lymphatics from the deltoid muscle, enter the lymph into the vena cava (

Figure 3), and distribute in the microcirculation of different organs within about an hour [55, 56]. Importantly, lymphatic vasomotion, and, hence, the pumping activity of lymph microvessels, are delicately controlled by endothelial nitric oxide and prostaglandins [

57].

The third option for LNP entry into the circulation is reversal of the enhanced permeation and retention (EPR) phenomenon [

58], whereby nanoparticles re-enter the blood from the extracellular space through regions of increased permeability in inflamed tissues.

As for the extent and kinetics of systemic biodistribution of mRNA-LNPs, Pfizer Australia's preclinical study reported that 2.8% of a radioactive lipid marker remained in the plasma of rats 15 minutes after intramuscular injection of Comirnaty-equivalent LNPs, with plasma levels peaking between 1 and 4 hours [

59]. Over a 48-hour period, the LNPs were primarily distributed to the liver, adrenal glands, spleen, and ovaries [

59]. Low-level (<2%) radioactive signals were also detected in 12 additional organs [59, 60].

The endothelial lining of blood vessels constitutes the first biological barrier to the systemic distribution of mRNA–LNPs, raising the question, what portion of the endothelial surface can be accessed by the LNPs. One approximation addressing this question is the LNP/EC ratio, i.e., the number of LNPs interacting with one EC. The 30 µg mRNA in each Comirnaty injection, taken together with the number of mRNA molecules in each fully loaded LNP to be in the low single digits [61-65], furthermore approximately 3% of the LNPs entering in blood over a few hours after the deltoid injection, the 2.05 × 10⁻⁸ moles of injected mRNA, or 1.23 × 10¹⁶ mRNA molecules translates to ~2xE

14 fully loaded LNPs reaching the blood within hours. This is about 300-fold higher than the estimated 6x10

11 EC in a 70 kg human, based on the measurements of blood vessel surface areas and endothelial cell dimensions [

66]. Although obviously, the individually variable muscular leakage kinetics and rapid uptake of LNPs by the liver and spleen rapidly modify this number, in theory, the vaccine-induced endothelial activation and inflammation can potentially affect the entire vascular system.

7. The Pathophysiology and Diagnosis of Vaccine-Induced Vasculitis

The diagnosis of vasculitis-related illnesses on organ level remains challenging. The nonspecific symptoms, such as fever, fatigue, rash, may not pin down the organ affected just as the inflammatory markers (e.g., CRP) and autoimmune indicators (e.g., ANCA, ANA) in blood

or cerebrospinal fluid. Imaging studies, including

conventional or digital subtraction angiography, MRI with contrast and tissue biopsies support the diagnosis, but a thorough differential diagnosis is essential to exclude infections, malignancies, and thrombotic disorders or ischemic or hemorrhagic lesions [

67]. Advanced techniques like vessel wall imaging (VWI) and magnetic resonance angiography (MRA) may reveal vessel abnormalities [

68].

Focusing on the role of SP in post-vaccination cerebral arteritis, a recent study demonstrated its prolonged presence in cerebral arteries, accompanied by inflammatory cell infiltration [

69]. This chronic cerebral inflammation may disrupt local circulation and oxygen delivery, potentially underlying symptoms such as fatigue, memory loss, dementia, Alzheimer acceleration and other cognitive or psychological complaints following vaccination. Supporting this, we observed impaired cerebrovascular regulation in individuals with post-COVID condition (whether from infection or vaccination), assessed using transcranial Doppler ultrasound, a non-invasive method that measures blood flow velocity in major cerebral arteries.

As shown in

Figure 4, the attenuated reactive hyperemic response reflects diminished vasodilatory capacity of cerebral resistance vessels in the brain and was associated with persistent cognitive and mental dysfunction even after ~2 years. Notably, this impairment was alleviated by regular physical activity [

26]

8. Systemic Biodistribution and Non-Target Organ Uptake of mRNA–LNPs

Beside the classic endocytic uptake of mRNA-LNPs by phagocytic cells in the body, a main mechanism is transfection via fusion. This function of LNPs has been known since the invention in the late 80-s that the ionizable, positively charged lipids can tightly bind the negatively charged nucleic acids and carry them into the cytoplasm of cells without loss of gene function [63, 70-78]. Since then, many different tissues and cells have been shown to be “viable targets” for gene therapies using LNPs [

79], providing rationale for using the LNPs for the delivery of SP mRNA to immune cells in the vicinity of the injection; the widely claimed mode of action of mRNA vaccines.

In the background of the selection of the ionizable positively charged aminolipids (ALC-0315 in Comirnaty) as main LNP component in mRNA vaccines, the concept was based, among others, on its nucleic acid-binding capability with fusogenic activity resulting in unique competency for genetic modification of cells. This selection was in keeping with the clinical success of liver-targeted patisiran (Onpattro), the first FDA-approved gene therapy against amyloidosis [

76], who’s ionizable fusogenic aminolipid component was similar to that used in Comirnaty.

The assumption that Comirnaty delivers mRNA exclusively to antigen-presenting cells (APCs) near to the injection site may have overlooked the 2015 study by Pardi et al, which showed delivery by LNPs and translation of firefly luciferase-mRNA in mice not only cells at the injection site, but also those in the liver, lung and other organs within 5 hours [

80]. Later, after the start of vaccine campaign, Pfizer/BioNTech quantitated the organ distribution of Comirnaty-equivalent mRNA-LNP and found them in 27 organs of rats also within hours [

59].

In large animals, Ferraresso et al. [

79] found transfection by LNP of almost all organs of pigs, and most recently, Dezsi et al reported the presence of SP mRNA and SP in different organs of pigs already 6 h after i.v. injection of Comirnaty (unpublished data). Remarkably, the SP mRNA uptake was paralleled upregulation of proinflammatory cytokine gene transcriptions, including IL-6, TNFa, and IL-1, which suggests that SP mRNA entry into cells plays a causal role in triggering inflammation [

81].

The internalization of LNPs by different cells may occur through multiple pathways, including clathrin- or caveolae-mediated endocytosis, micropinocytosis -particularly in inflamed or activated endothelium- and/or membrane fusion, a hallmark of LNPs containing ionizable lipids. As for ECs, experimental evidence for effective LNP delivery of functional mRNA into these cells across various organs is well documented [82-89]. However, regardless of the entry mechanism of mRNA-LNPs into the ECs, the internalized mRNA and de novo synthesized SP trigger the activation of ECs via a variety of ways, direct and indirect, independent and cooperative, involving innate and adaptive immune responses. These are itemized below.

9. Adverse Impacts of mRNA-LNPs and the Spike Protein on Endothelial Cells

The SP functions as a pluripotent toxin [90-94], causing oxidative damage of the mitochondria [95-97], induction of proinflammatory cytokines [98, 99] and other self-destructive effects in the cells that produce them.

Further immune-mediated damage to the mRNA-LNP transfected EC is related to the diversification of the intracellular antigen processing of free ribosome-derived SP [9, 100], as recapitulated below.

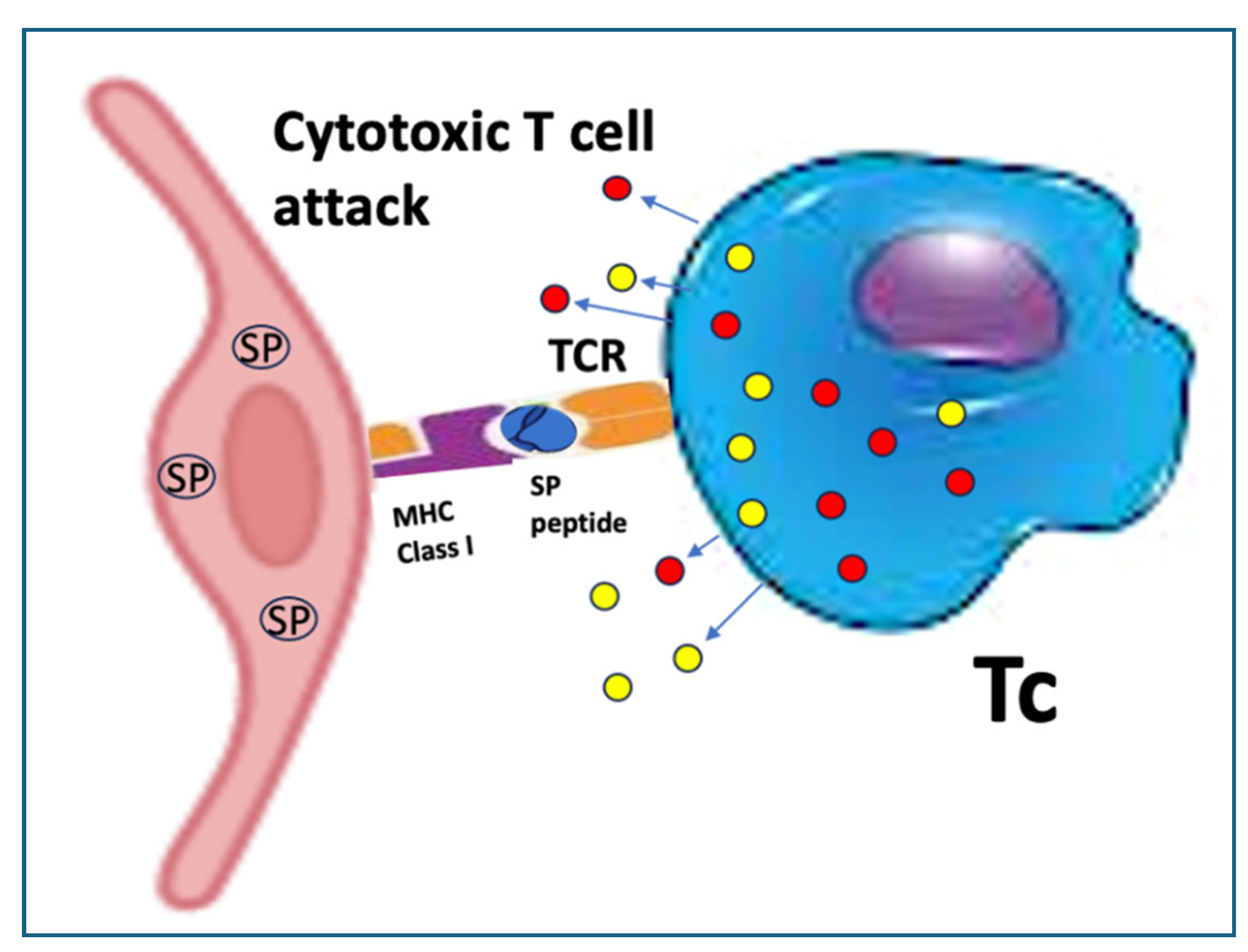

After formation on free ribosomes, which exceeds the number of endoplasmic reticulum (ER)-bound ribosomes in most cells [

101], part of the intact SP molecules in transfected cells undergoes proteasome digestion, which yields antigenic peptides to be transported to MHC Class I molecules on the endothelial cell surface [

100]. This process is known as cross-presentation [

102], since SP degradation peptides are supposed to be presented on MHC-II molecules. In previously infected or immunized people, MHC Class I-presented peptides are recognized by specific cytotoxic T cells (Tc, CTLs) which attack the EC cells (

Figure 5). This mechanism plays a major role in the widespread autoimmune phenomena observed after vaccination and may help explain why booster injections can elicit more pronounced AEs than primary immunization.

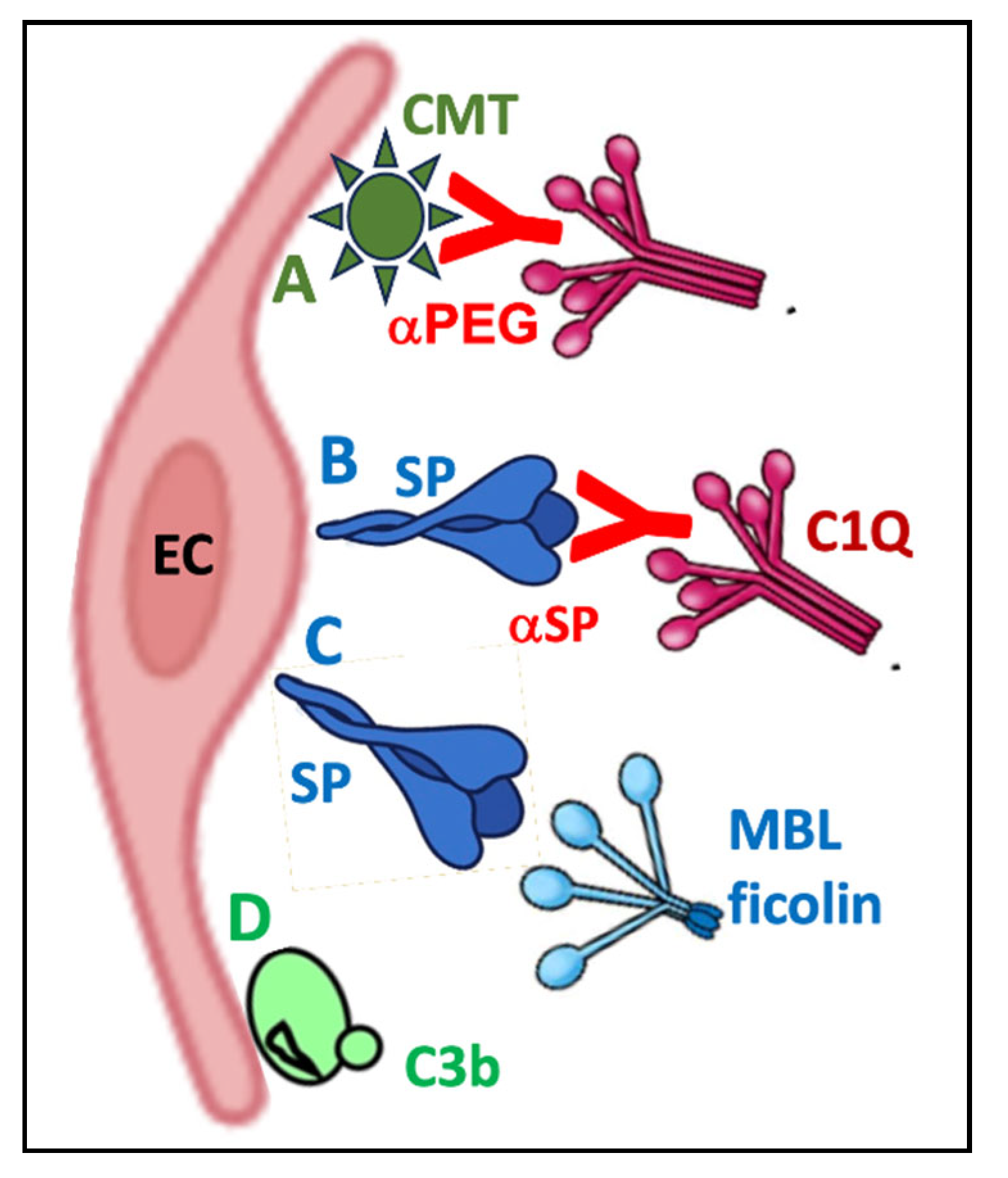

In addition to proteasomal degradation, an alternative trafficking route for the translated SP directs it to the cell membrane, i.e., the same destination it naturally follows in SARS-CoV-2-infected cells. As a result, the luminal surface of ECs, along with the outer membrane of other transfected cells, becomes “crowned” with SP, mimicking a true viral infection. The immune system recognizes these “pseudo-infected” cells and targets them through at least two antibody-dependent elimination mechanisms: complement (C) activation (

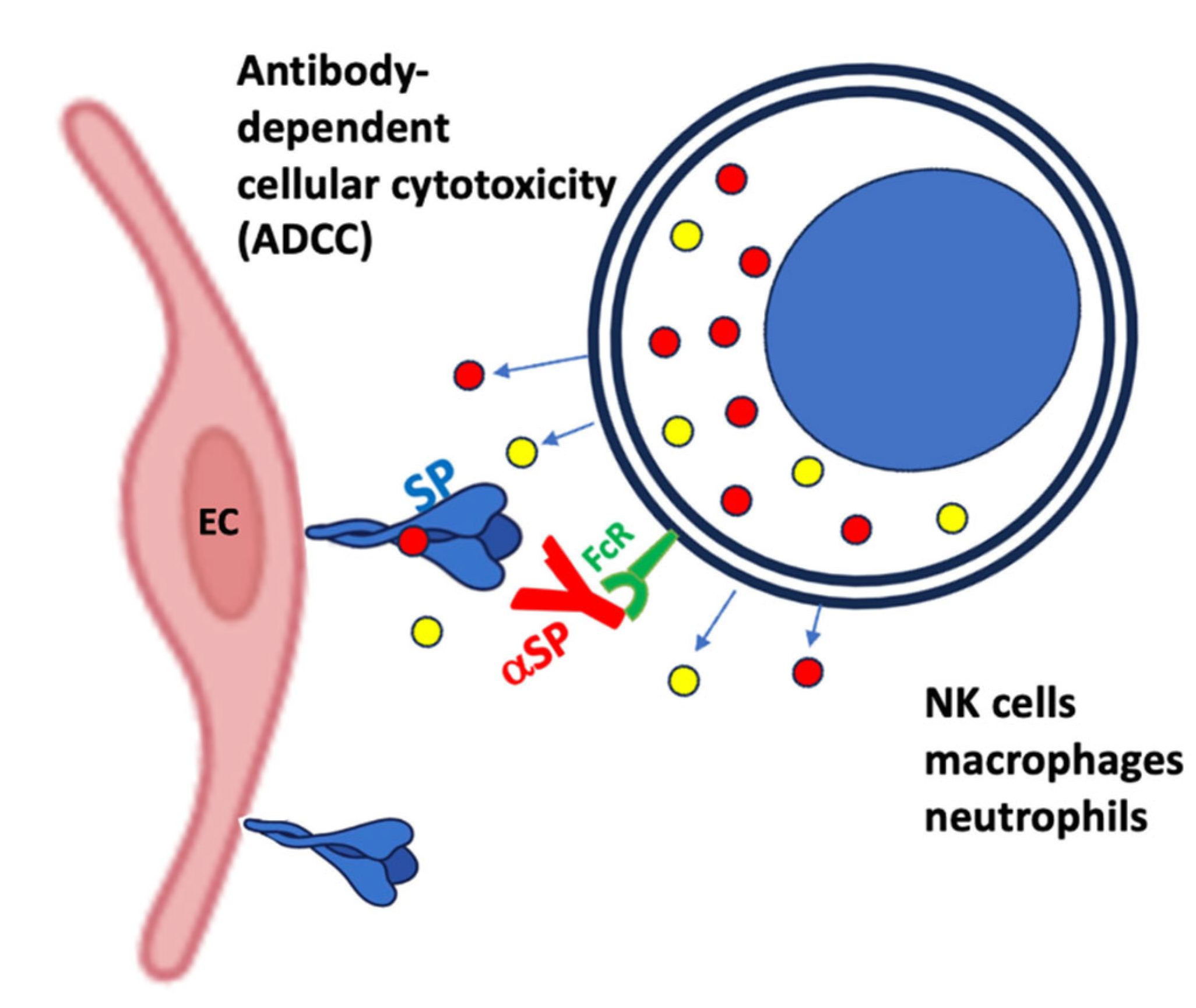

Figure 6) and antibody-dependent cellular cytotoxicity (ADCC) (

Figure 7).

Regarding C activation, Comirnaty is a strong initiator of this process [103-105], a relatively ignored contributor to the AEs of mRNA vaccines [

65]. It came to the focus of attention in this subject because of its role in the acute anaphylactic reactions whose incidence had significantly increased after immunisation with mRNA vaccines [

106]. These investigations [65, 103-106] led to the concept that C activation-related pseudoallergy (CARPA) represents a significant contributor to vaccine-induced anaphylaxis [

65]. However, while CARPA is due to fluid phase activation of the proteolytic cascade, the C-mediated cytotoxicity proceeds on cell surfaces, including the ECs. C activation on cell surfaces that express the SP and or bind PEGylated LNP can also occur via both the classical and the alternative the pathways [

104]. The former process may be due to anti-PEG antibody binding to EC-adhered mRNA-LNPs, which express PEG on their surface (

Figure 6A). The SP is moving from free ribosomes to the cell surface, triggering also classical pathway C activation through the binding of anti-SP antibodies Fig 6B). In addition, fluid phase and cell surface SP can induce lectin pathway activation [93, 107] (Fig 6C) and the damaged cell membrane can bind C3b directly, the core mechanism of alternative pathway activation (Fig 6D). Each of these activations can be perpetuated via the alternative pathway amplification loop [108, 109], fed by activated EC-produced C3,

properdin and factor B. The other antibody-mediated EC cell damage is called antibody-dependent cellular cytotoxicity (ADCC) whereupon effector cells of the immune system recognize and eliminate target cells that have been opsonized by specific antibodies. The cells involved in this action include natural killer (NK) cells, macrophages and neutrophils. The specific antibodies, usually IgG1 or IgG3, bind to antigens expressed on the surface of a target cell and these antibodies are recognized by

the Fcγ receptors (especially FcγRIIIa/CD16) on the above cells (

Figure 7). Binding of FcγR triggers degranulation of these effector cells, just as the binding of CTL to MHC Class I molecules triggering the release of

cytolytic mediators, namely p

erforins and granzymes.

The latter proteins, especially granzyme B, are serine proteases that activate caspases (e.g., caspase-3) that cause DNA fragmentation and apoptosis. Granzyme A induces caspase-independent cell death (via reactive oxygen species, mitochondrial damage). Both NK cells and CTLs use

receptor-ligand interactions leading to cell death, such as the binding of Fas Ligand (FasL, CD95L) to

Fas receptors (CD95) on target cells, activating caspase-8 and causing apoptosis [110, 111]. The

TNF-related apoptosis-inducing ligand (TRAIL) is also involved in the apoptotic attack of Tc and/or NK on the ECs [

112]. Among the cytokines produced,

IFN-γ enhances macrophage activity and antigen presentation [

113].

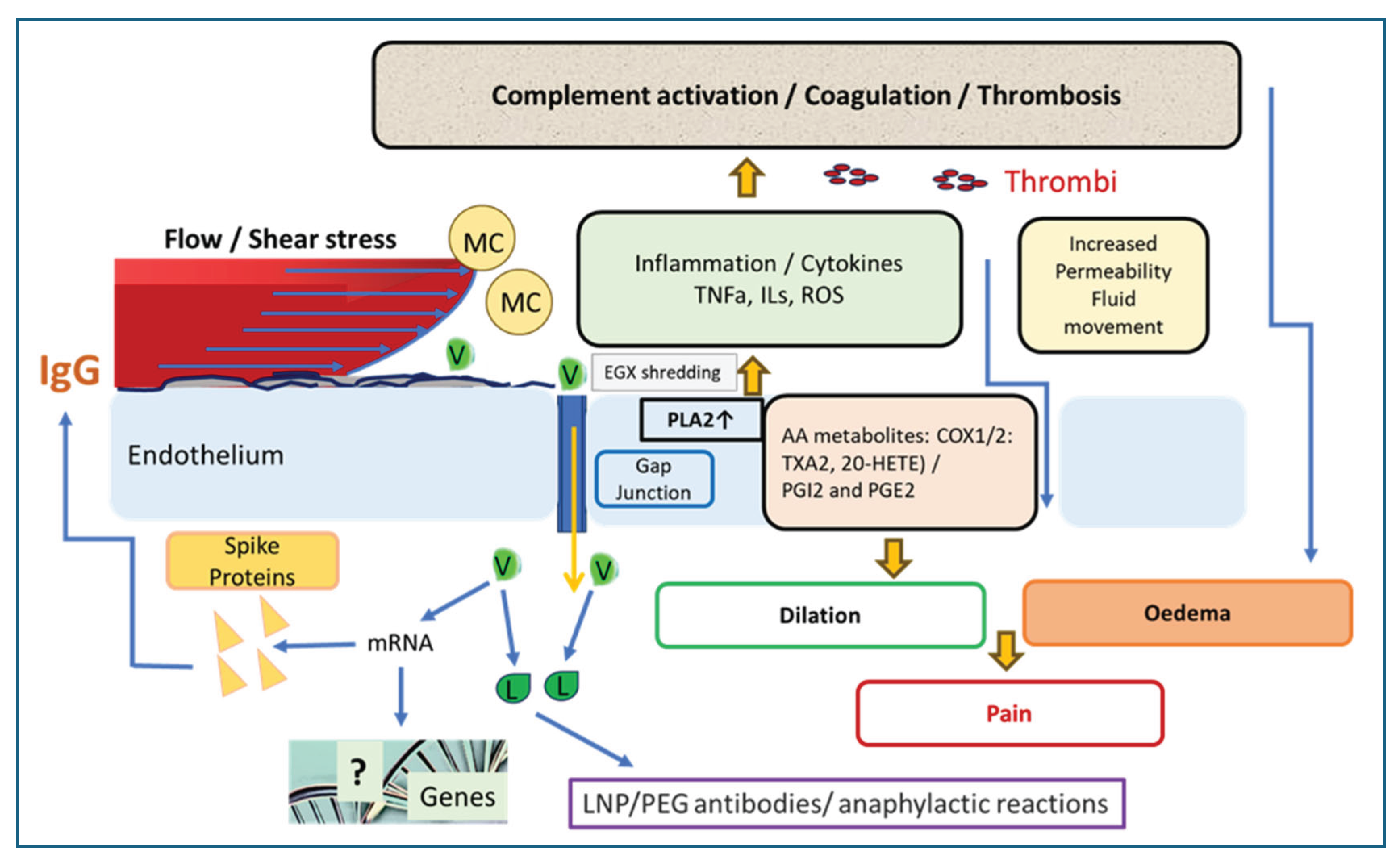

10. Causes and features of endothelitis

Figure 8 illustrates the process whereupon the encounter with vaccine nanoparticles entails the activation of ECs. In this process, the glycocalyx derangement enables the deposition of neutrophils, monocytes and macrophages, with the release of oxygen radicals, PLA2, cytokines, leukotrienes, C proteins and other inflammatory mediators. The pathophysiological manifestations of EC activation and damages include increased vascular permeability, opening the gap junctions, release of PLA2, leukotrienes, cytokines and reactive oxygen species, deposition of neutrophils, monocytes and macrophages. The opening of the gap junctions upon vasodilatation (which increases intravascular pressure) is associated with oedema and pain. The increased production of thromboxane A2 and reduced production of prostaglandins and nitric oxide create a pro-coagulant environment promoting thrombogenesis. Moreover, damaged ECs release DAMPs, which further activate the immune system and contribute to a cycle of self-perpetuating chronic condition. Endothelial microparticles (exosomes) and anti-endothelial cell antibodies have been identified as diagnostic or prognostic biomarkers of endothelitis.

11. Outlook

Since the introduction and widespread deployment of mRNA-based COVID-19 vaccines, their safety profile has become a focal point of both public discourse and scientific investigation. This cutting-edge technology has raised several unresolved questions, particularly regarding the unusually broad spectrum and relatively high incidence of AEs associated with its use [

1].

One emerging vision, as mentioned in the discussion of the root cause of the vaccine’s inflammatory effects (

Section 2), is an infection-like process initiated by the pluritoxic SP, resulting from multiorgan transfection with its genetic code delivered via a proinflammatory, fusogenic viral surrogate, the mRNA–LNP complex [

9]. Although this concept remains outside mainstream scientific consensus, the AE problem is drawing growing attention and has begun to influence vaccination policies. Notably, however, most attention has centered more on the accumulating evidence of AEs and their public health implications than on the underlying conceptual issue, namely, the fundamental modification of natural immunogenicity may lead to autoimmunity, and that the vaccine may functionally mimic a systemically distributed, simplified, non-replicating, nevertheless pathogenic form of SARS-CoV-2. Encouragingly, such systemic manifestations appear to affect only a small fraction of individuals, raising a critical question for future research: what protects the vast majority from this iatrogenic challenge?

Among those who professionally address the problem there is growing recognition that a common pathogenic mechanism is vascular inflammation, more precisely, endothelitis. By highlighting the tissue-specific characteristics of vaccine-transfected microcirculation, the mechanisms of mRNA-LNP uptake at the cellular level, and the self-damaging effects of SP expression, this review aims to contribute to the resolution of key uncertainties surrounding genetic vaccines. While acknowledging the advance and health benefits, the lessons learned from studying the AEs of mRNA-LNP-based vaccines will enhance the safety of future therapeutic interventions and products developed using this technology.

Funding

The financial supports by the European Union Horizon 2020 project 825828 (Expert) and 2022-1.2.5-TÉT-IPARI-KR-2022-00009 (JS) and Project no. TKP2020-NKA-17 and TKP2021-EGA-37 by the Ministry of Innovation and Technology of Hungary from the National Research, Development and Innovation Fund, and MTA/HAS-Post-Covid 2021-34 and National Research, Development, and Innovation Office of Hungary (OTKA132596, K-19 (AK) are acknowledged.

References

- Szebeni, J. "Expanded Spectrum and Increased Incidence of Adverse Events Linked to Covid-19 Genetic Vaccines: New Concepts on Prophylactic Immuno-Gene Therapy, Iatrogenic Orphan Disease, and Platform-Inherent Challenges." Pharmaceutics 17, no. 4 (2025): 450.

- Krumholz, H. M., Y. Wu, M. Sawano, R. Shah, T. Zhou, A. S. Arun, P. Khosla, S. Kaleem, A. Vashist, B. Bhattacharjee, Q. Ding, Y. Lu, C. Caraballo, F. Warner, C. Huang, J. Herrin, D. Putrino, D. Hertz, B. Dressen, and A. Iwasaki. "Post-Vaccination Syndrome: A Descriptive Analysis of Reported Symptoms and Patient Experiences after Covid-19 Immunization." medRxiv posted , 2023. 10 November. [CrossRef]

- Palmer, M., S. Bhakdi, B. Hooker, M. Holland, M. DesBois, D. Rasnick, and C.A. Fitts. Mrna Vvaccine Toxicity, /: https, 2023. [Google Scholar]

- Costa, C. , and F. Moniati. "The Epidemiology of Covid-19 Vaccine-Induced Myocarditis." Adv Med 2024 (2024): 4470326.

- Novak, N., L. Tordesillas, and B. Cabanillas. "Adverse Rare Events to Vaccines for Covid-19: From Hypersensitivity Reactions to Thrombosis and Thrombocytopenia." Int Rev Immunol 41, no. 4 (2022): 438-47.

- Oueijan, R. I., O. R. Hill, P. D. Ahiawodzi, P. S. Fasinu, and D. K. Thompson. "Rare Heterogeneous Adverse Events Associated with Mrna-Based Covid-19 Vaccines: A Systematic Review." Medicines (Basel) 9, no. 8 (2022).

- Padilla-Flores, T., A. Sampieri, and L. Vaca. "Incidence and Management of the Main Serious Adverse Events Reported after Covid-19 Vaccination." Pharmacol Res Perspect 12, no. 3 (2024): e1224.

- Worldwide Safety. "Cumulative Analysis of Post-Authorization Adverse Event Reports of Pf-07302048 (Bnt162b2) Received through 28-Feb-2021." https://phmpt.org/wp-content/uploads/2021/11/5.3.6-postmarketing-experience.pdf?fbclid=IwAR2tWI7DKw0cc2lj8 (2021).

- Szebeni, J. "The Unique Features and Collateral Immune Effects of Mrna-Based Covid-19 Vaccines: Potential Plausible Causes of Adverse Events and Complications." In Preprints: Preprints, 2025.

- Kariko, K., M. Buckstein, H. Ni, and D. Weissman. "Suppression of Rna Recognition by Toll-Like Receptors: The Impact of Nucleoside Modification and the Evolutionary Origin of Rna." Immunity 23, no. 2 (2005): 165-75.

- Kariko, K., H. Muramatsu, F. A. Welsh, J. Ludwig, H. Kato, S. Akira, and D. Weissman. "Incorporation of Pseudouridine into Mrna Yields Superior Nonimmunogenic Vector with Increased Translational Capacity and Biological Stability." Mol Ther 16, no. 11 (2008): 1833-40.

- Anderson, B. R., H. Muramatsu, S. R. Nallagatla, P. C. Bevilacqua, L. H. Sansing, D. Weissman, and K. Kariko. "Incorporation of Pseudouridine into Mrna Enhances Translation by Diminishing Pkr Activation." Nucleic Acids Res 38, no. 17 (2010): 5884-92.

- Anderson, B. R., H. Muramatsu, B. K. Jha, R. H. Silverman, D. Weissman, and K. Kariko. "Nucleoside Modifications in Rna Limit Activation of 2'-5'-Oligoadenylate Synthetase and Increase Resistance to Cleavage by Rnase L." Nucleic Acids Res 39, no. 21 (2011): 9329-38.

- Kariko, K., H. Muramatsu, J. Ludwig, and D. Weissman. "Generating the Optimal Mrna for Therapy: Hplc Purification Eliminates Immune Activation and Improves Translation of Nucleoside-Modified, Protein-Encoding Mrna." Nucleic Acids Res 39, no. 21 (2011): e142.

- Rehwinkel, J. , and M. U. Gack. "Rig-I-Like Receptors: Their Regulation and Roles in Rna Sensing." Nat Rev Immunol 20, no. 9 (2020): 537-51.

- Lv, Y. , and Y. Chang. "Cytomegalovirus Proctitis Developed after Covid-19 Vaccine: A Case Report and Literature Review." Vaccines (Basel) 10, no. 9 (2022).

- Chakravorty, S., A. B. Cochrane, M. A. Psotka, A. Regmi, L. Marinak, A. Thatcher, O. A. Shlobin, A. W. Brown, C. S. King, K. Ahmad, V. Khangoora, A. Singhal, S. D. Nathan, and S. Aryal. "Cmv Infection Following Mrna Sars-Cov-2 Vaccination in Solid Organ Transplant Recipients." Transplant Direct 8, no. 7 (2022): e1344.

- Herzum, A., I. Trave, F. D'Agostino, M. Burlando, E. Cozzani, and A. Parodi. "Epstein-Barr Virus Reactivation after Covid-19 Vaccination in a Young Immunocompetent Man: A Case Report." Clin Exp Vaccine Res 11, no. 2 (2022): 222-25.

- Navarro-Bielsa, A., T. Gracia-Cazana, B. Aldea-Manrique, I. Abadias-Granado, A. Ballano, I. Bernad, and Y. Gilaberte. "Covid-19 Infection and Vaccines: Potential Triggers of Herpesviridae Reactivation." An Bras Dermatol 98, no. 3 (2023): 347-54.

- Shafiee, A., M. J. Amini, R. Arabzadeh Bahri, K. Jafarabady, S. A. Salehi, H. Hajishah, and S. H. Mozhgani. "Herpesviruses Reactivation Following Covid-19 Vaccination: A Systematic Review and Meta-Analysis." Eur J Med Res 28, no. 1 (2023): 278.

- Maple, P. A. C. "Covid-19, Sars-Cov-2 Vaccination, and Human Herpesviruses Infections." Vaccines (Basel) 11, no. 2 (2023).

- Martinez-Reviejo, R., S. Tejada, G. A. R. Adebanjo, C. Chello, M. C. Machado, F. R. Parisella, M. Campins, A. Tammaro, and J. Rello. "Varicella-Zoster Virus Reactivation Following Severe Acute Respiratory Syndrome Coronavirus 2 Vaccination or Infection: New Insights." Eur J Intern Med 104 (2022): 73-79.

- Elbaz, M., T. Hoffman, D. Yahav, S. Dovrat, N. Ghanem-Zoubi, A. Atamna, D. Grupel, S. Reisfeld, M. Hershman-Sarafov, P. Ciobotaro, R. Najjar-Debbiny, T. Brosh-Nissimov, B. Chazan, O. Yossepowitch, Y. Wiener-Well, O. Halutz, S. Reich, R. Ben-Ami, and Y. Paran. "Varicella-Zoster Virus-Induced Neurologic Disease after Covid-19 Vaccination: A Multicenter Observational Cohort Study." Open Forum Infect Dis 11, no. 6 (2024): ofae287.

- Attwell, D., A. Mishra, C. N. Hall, F. M. O'Farrell, and T. Dalkara. "What Is a Pericyte?" J Cereb Blood Flow Metab 36, no. 2 (2016): 451-5.

- Ishiko, S., A. Koller, W. Deng, A. Huang, and D. Sun. "Liposomal Nanocarriers of Preassembled Glycocalyx Restore Normal Venular Permeability and Shear Stress Sensitivity in Sepsis: Assessed Quantitatively with a Novel Microchamber System." Am J Physiol Heart Circ Physiol 327, no. 2 (2024): H390-H98.

- Takacs, J., D. Deak, and A. Koller. "Higher Level of Physical Activity Reduces Mental and Neurological Symptoms During and Two Years after Covid-19 Infection in Young Women." Sci Rep 14, no. 1 (2024): 6927.

- Nemeth, Z., A. Cziraki, S. Szabados, I. Horvath, and A. Koller. "Pericardial Fluid of Cardiac Patients Elicits Arterial Constriction: Role of Endothelin-1." Can J Physiol Pharmacol 93, no. 9 (2015): 779-85.

- Nemeth, Z., A. Cziraki, S. Szabados, B. Biri, S. Keki, and A. Koller. "Elevated Levels of Asymmetric Dimethylarginine (Adma) in the Pericardial Fluid of Cardiac Patients Correlate with Cardiac Hypertrophy." PLoS One 10, no. 8 (2015): e0135498.

- Cziraki, A., Z. Lenkey, E. Sulyok, I. Szokodi, and A. Koller. "L-Arginine-Nitric Oxide-Asymmetric Dimethylarginine Pathway and the Coronary Circulation: Translation of Basic Science Results to Clinical Practice." Front Pharmacol 11 (2020): 569914.

- Gill, J. R., R. Tashjian, and E. Duncanson. "Autopsy Histopathologic Cardiac Findings in 2 Adolescents Following the Second Covid-19 Vaccine Dose." Arch Pathol Lab Med 146, no. 8 (2022): 925-29.

- Verma, A. K., K. J. Lavine, and C. Y. Lin. "Myocarditis after Covid-19 Mrna Vaccination." N Engl J Med 385, no. 14 (2021): 1332-34.

- Rodriguez, E. R. , and C. D. Tan. "Structure and Anatomy of the Human Pericardium." Prog Cardiovasc Dis 59, no. 4 (2017): 327-40.

- Rinaldi, V., G. Bellucci, M. C. Buscarinu, R. Renie, A. Marrone, M. Nasello, V. Zancan, R. Nistri, R. Palumbo, A. Salerno, M. Salvetti, and G. Ristori. "Cns Inflammatory Demyelinating Events after Covid-19 Vaccines: A Case Series and Systematic Review." Front Neurol 13 (2022): 1018785.

- Patone, M., L. Handunnetthi, D. Saatci, J. Pan, S. V. Katikireddi, S. Razvi, D. Hunt, X. W. Mei, S. Dixon, F. Zaccardi, K. Khunti, P. Watkinson, C. A. C. Coupland, J. Doidge, D. A. Harrison, R. Ravanan, A. Sheikh, C. Robertson, and J. Hippisley-Cox. "Neurological Complications after First Dose of Covid-19 Vaccines and Sars-Cov-2 Infection." Nat Med 27, no. 12 (2021): 2144-53.

- Khayat-Khoei, M., S. Bhattacharyya, J. Katz, D. Harrison, S. Tauhid, P. Bruso, M. K. Houtchens, K. R. Edwards, and R. Bakshi. "Covid-19 Mrna Vaccination Leading to Cns Inflammation: A Case Series." J Neurol 269, no. 3 (2022): 1093-106.

- Yoshikawa, T., K. Tomomatsu, E. Okazaki, T. Takeuchi, Y. Horio, Y. Kondo, T. Oguma, and K. Asano. "Covid-19 Vaccine-Associated Organizing Pneumonia." Respirol Case Rep 10, no. 5 (2022): e0944.

- Park, J. Y., J. H. Kim, S. Park, Y. I. Hwang, H. I. Kim, S. H. Jang, K. S. Jung, Y. K. Kim, H. A. Kim, and I. J. Lee. "Clinical Characteristics of Patients with Covid-19 Vaccine-Related Pneumonitis: A Case Series and Literature Review." Korean J Intern Med 37, no. 5 (2022): 989-1001.

- Kervella, D., L. Jacquemont, A. Chapelet-Debout, C. Deltombe, and S. Ville. "Minimal Change Disease Relapse Following Sars-Cov-2 Mrna Vaccine." Kidney Int 100, no. 2 (2021): 457-58.

- Zhang, J., J. Cao, and Q. Ye. "Renal Side Effects of Covid-19 Vaccination." Vaccines (Basel) 10, no. 11 (2022).

- Rocco, A., C. Sgamato, D. Compare, and G. Nardone. "Autoimmune Hepatitis Following Sars-Cov-2 Vaccine: May Not Be a Casuality." J Hepatol 75, no. 3 (2021): 728-29.

- Schinas, G., E. Polyzou, V. Dimakopoulou, S. Tsoupra, C. Gogos, and K. Akinosoglou. "Immune-Mediated Liver Injury Following Covid-19 Vaccination." World J Virol 12, no. 2 (2023): 100-08.

- Sergi, C. M. "Covid-19 Vaccination-Related Autoimmune Hepatitis-a Perspective." Front Pharmacol 14 (2023): 1190367.

- Chen, C., D. Xie, and J. Xiao. "Real-World Evidence of Autoimmune Hepatitis Following Covid-19 Vaccination: A Population-Based Pharmacovigilance Analysis." Front Pharmacol 14 (2023): 1100617.

- Kim, J. H., H. B. Chae, S. Woo, M. S. Song, H. J. Kim, and C. G. Woo. "Clinicopathological Characteristics of Autoimmune-Like Hepatitis Induced by Covid-19 Mrna Vaccine (Pfizer-Biontech, Bnt162b2): A Case Report and Literature Review." Int J Surg Pathol 31, no. 6 (2023): 1156-62.

- Liang, F., G. Lindgren, A. Lin, E. A. Thompson, S. Ols, J. Rohss, S. John, K. Hassett, O. Yuzhakov, K. Bahl, L. A. Brito, H. Salter, G. Ciaramella, and K. Lore. "Efficient Targeting and Activation of Antigen-Presenting Cells in Vivo after Modified Mrna Vaccine Administration in Rhesus Macaques." Mol Ther 25, no. 12 (2017): 2635-47.

- Bettini, E. , and M. Locci. "Sars-Cov-2 Mrna Vaccines: Immunological Mechanism and Beyond." Vaccines (Basel) 9, no. 2 (2021).

- Szabo, G. T., A. J. Mahiny, and I. Vlatkovic. "Covid-19 Mrna Vaccines: Platforms and Current Developments." Mol Ther 30, no. 5 (2022): 1850-68.

- Buckley, M., M. Arainga, L. Maiorino, I. S. Pires, B. J. Kim, K. K. Michaels, J. Dye, K. Qureshi, Y. J. Zhang, H. Mak, J. M. Steichen, W. R. Schief, F. Villinger, and D. J. Irvine. "Visualizing Lipid Nanoparticle Trafficking for Mrna Vaccine Delivery in Non-Human Primates." Mol Ther 33, no. 3 (2025): 1105-17.

- Ndeupen, S., Z. Qin, S. Jacobsen, A. Bouteau, H. Estanbouli, and B. Z. Igyarto. "The Mrna-Lnp Platform's Lipid Nanoparticle Component Used in Preclinical Vaccine Studies Is Highly Inflammatory." iScience 24, no. 12 (2021): 103479.

- Krauson, A. J., F. V. C. Casimero, Z. Siddiquee, and J. R. Stone. "Duration of Sars-Cov-2 Mrna Vaccine Persistence and Factors Associated with Cardiac Involvement in Recently Vaccinated Patients." NPJ Vaccines 8, no. 1 (2023): 141.

- Mizuno, R., G. Dornyei, A. Koller, and G. Kaley. "Myogenic Responses of Isolated Lymphatics: Modulation by Endothelium." Microcirculation 4, no. 4 (1997): 413-20.

- Koller, A., R. Mizuno, and G. Kaley. "Flow Reduces the Amplitude and Increases the Frequency of Lymphatic Vasomotion: Role of Endothelial Prostanoids." Am J Physiol 277, no. 6 (1999): R1683-9.

- Breslin, J. W. "Mechanical Forces and Lymphatic Transport." Microvasc Res 96 (2014): 46-54.

- von der Weid, P. Y. "Lymphatic Vessel Pumping." Adv Exp Med Biol 1124 (2019): 357-77.

- Alazraki, N., E. C. Glass, F. Castronovo, R. A. Olmos, D. Podoloff, and Medicine Society of Nuclear. "Procedure Guideline for Lymphoscintigraphy and the Use of Intraoperative Gamma Probe for Sentinel Lymph Node Localization in Melanoma of Intermediate Thickness 1.0." J Nucl Med 43, no. 10 (2002): 1414-8.

- Dixon, J. B., S. T. Greiner, A. A. Gashev, G. L. Cote, J. E. Moore, and D. C. Zawieja. "Lymph Flow, Shear Stress, and Lymphocyte Velocity in Rat Mesenteric Prenodal Lymphatics." Microcirculation 13, no. 7 (2006): 597-610.

- Mizuno, R., A. Koller, and G. Kaley. "Regulation of the Vasomotor Activity of Lymph Microvessels by Nitric Oxide and Prostaglandins." Am J Physiol 274, no. 3 (1998): R790-6.

- Borresen, B., A. E. Hansen, F. P. Fliedner, J. R. Henriksen, D. R. Elema, M. Brandt-Larsen, L. K. Kristensen, A. T. Kristensen, T. L. Andresen, and A. Kjaer. "Noninvasive Molecular Imaging of the Enhanced Permeability and Retention Effect by (64)Cu-Liposomes: In Vivo Correlations with (68)Ga-Rgd, Fluid Pressure, Diffusivity and (18)F-Fdg." Int J Nanomedicine 15 (2020): 8571-81.

- Ltd, Pfizer Australia Pty. "Nonclinical Evaluation Report: Bnt162b2 [Mrna] Covid-19 Vaccine (Comirnatytm)." https://www.tga.gov.au/sites/default/files/foi-2389-06.pdf https://t.co/Zrhakh7Xgv (2021).

- Vegh, A., A. Csorba, A. Koller, B. Mohammadpour, P. Killik, L. Istvan, M. Magyar, T. Fenesi, and Z. Z. Nagy. "Presence of Sars-Cov-2 on the Conjunctival Mucosa in Patients Hospitalized Due to Covid-19: Pathophysiological Considerations and Therapeutic Implications." Physiol Int 109, no. 4 (2022): 475-85.

- Pardi, N., M. J. Hogan, F. W. Porter, and D. Weissman. "Mrna Vaccines - a New Era in Vaccinology." Nat Rev Drug Discov 17, no. 4 (2018): 261-79.

- Sabnis, S., E. S. Kumarasinghe, T. Salerno, C. Mihai, T. Ketova, J. J. Senn, A. Lynn, A. Bulychev, I. McFadyen, J. Chan, O. Almarsson, M. G. Stanton, and K. E. Benenato. "A Novel Amino Lipid Series for Mrna Delivery: Improved Endosomal Escape and Sustained Pharmacology and Safety in Non-Human Primates." Mol Ther 26, no. 6 (2018): 1509-19.

- Hou, X., T. Zaks, R. Langer, and Y. Dong. "Lipid Nanoparticles for Mrna Delivery." Nat Rev Mater 6, no. 12 (2021): 1078-94.

- Li, S., Y. Hu, A. Li, J. Lin, K. Hsieh, Z. Schneiderman, P. Zhang, Y. Zhu, C. Qiu, E. Kokkoli, T. H. Wang, and H. Q. Mao. "Payload Distribution and Capacity of Mrna Lipid Nanoparticles." Nat Commun 13, no. 1 (2022): 5561.

- Szebeni, J., G. Storm, J. Y. Ljubimova, M. Castells, E. J. Phillips, K. Turjeman, Y. Barenholz, D. J. A. Crommelin, and M. A. Dobrovolskaia. "Applying Lessons Learned from Nanomedicines to Understand Rare Hypersensitivity Reactions to Mrna-Based Sars-Cov-2 Vaccines." Nat Nanotechnol 17, no. 4 (2022): 337-46.

- Jaffe, E. A. "Cell Biology of Endothelial Cells." Hum Pathol 18, no. 3 (1987): 234-9.

- Rice, C. M. , and N. J. Scolding. "The Diagnosis of Primary Central Nervous System Vasculitis." Pract Neurol 20, no. 2 (2020): 109-14.

- Gupta, N., S. B. Hiremath, R. I. Aviv, and N. Wilson. "Childhood Cerebral Vasculitis : A Multidisciplinary Approach." Clin Neuroradiol 33, no. 1 (2023): 5-20.

- Ota, N., M. Itani, T. Aoki, A. Sakurai, T. Fujisawa, Y. Okada, K. Noda, Y. Arakawa, S. Tokuda, and R. Tanikawa. "Expression of Sars-Cov-2 Spike Protein in Cerebral Arteries: Implications for Hemorrhagic Stroke Post-Mrna Vaccination." J Clin Neurosci 136 (2025): 111223.

- Felgner, P. L., T. R. Gadek, M. Holm, R. Roman, H. W. Chan, M. Wenz, J. P. Northrop, G. M. Ringold, and M. Danielsen. "Lipofection: A Highly Efficient, Lipid-Mediated DNA-Transfection Procedure." Proc Natl Acad Sci U S A 84, no. 21 (1987): 7413-7.

- Horejs, C. "From Lipids to Lipid Nanoparticles to Mrna Vaccines." Nat Rev Mater 6, no. 12 (2021): 1075-76.

- HOLLAND, JOHN W. (Australia), PIETER R. (Canada) CULLIS, and THOMAS D. (Canada) MADDEN. "Bilayer Stabilizing Components and Their Use in Forming Programmable Fusogenic Liposomes." edited by THE UNIVERSITY OF BRITISH COLUMBIA, 2007-12-04.

- Chen, S., Y. Y. C. Tam, P. J. C. Lin, M. M. H. Sung, Y. K. Tam, and P. R. Cullis. "Influence of Particle Size on the in Vivo Potency of Lipid Nanoparticle Formulations of Sirna." J Control Release 235 (2016): 236-44.

- Cullis, P. R. , and M. J. Hope. "Lipid Nanoparticle Systems for Enabling Gene Therapies." Mol Ther 25, no. 7 (2017): 1467-75.

- Kulkarni, J. A., M. M. Darjuan, J. E. Mercer, S. Chen, R. van der Meel, J. L. Thewalt, Y. Y. C. Tam, and P. R. Cullis. "On the Formation and Morphology of Lipid Nanoparticles Containing Ionizable Cationic Lipids and Sirna." ACS Nano 12, no. 5 (2018): 4787-95.

- Akinc, A., M. A. Maier, M. Manoharan, K. Fitzgerald, M. Jayaraman, S. Barros, S. Ansell, X. Du, M. J. Hope, T. D. Madden, B. L. Mui, S. C. Semple, Y. K. Tam, M. Ciufolini, D. Witzigmann, J. A. Kulkarni, R. van der Meel, and P. R. Cullis. "The Onpattro Story and the Clinical Translation of Nanomedicines Containing Nucleic Acid-Based Drugs." Nat Nanotechnol 14, no. 12 (2019): 1084-87.

- Pateev, I., K. Seregina, R. Ivanov, and V. Reshetnikov. "Biodistribution of Rna Vaccines and of Their Products: Evidence from Human and Animal Studies." Biomedicines 12, no. 1 (2023).

- Dalby, B., S. Cates, A. Harris, E. C. Ohki, M. L. Tilkins, P. J. Price, and V. C. Ciccarone. "Advanced Transfection with Lipofectamine 2000 Reagent: Primary Neurons, Sirna, and High-Throughput Applications." Methods 33, no. 2 (2004): 95-103.

- Ferraresso, F., K. Badior, M. Seadler, Y. Zhang, A. Wietrzny, M. F. Cau, A. Haugen, G. G. Rodriguez, M. R. Dyer, P. R. Cullis, E. Jan, and C. J. Kastrup. "Protein Is Expressed in All Major Organs after Intravenous Infusion of Mrna-Lipid Nanoparticles in Swine." Mol Ther Methods Clin Dev 32, no. 3 (2024): 101314.

- Pardi, N., S. Tuyishime, H. Muramatsu, K. Kariko, B. L. Mui, Y. K. Tam, T. D. Madden, M. J. Hope, and D. Weissman. "Expression Kinetics of Nucleoside-Modified Mrna Delivered in Lipid Nanoparticles to Mice by Various Routes." J Control Release 217 (2015): 345-51.

- László Dézsi1, 2, **, Gábor Kökény2**, Gábor Szénási2, Csaba Révész1,2, Tamás Mészáros1,2,3,4, Balint A. Barta4, ????, Reka Facsko1,2,4, Anna Szilasi5, Tamás Bakos1, Gergely T. Kozma1,3, Attila B. Dobos4, Béla Merkely4, Tamás Radovits4, János Szebeni1,2,3,*. "Acute Anaphylactic and Multiorgan Inflammatory Effects of Mrna Vaccines in Pigs: Pcr Evidence of Spike Protein Mrna Transfection and Paralleling Inflammatory Cytokine Upregulation." Preprint (2025).

- Sago, C. D., M. P. Lokugamage, K. Paunovska, D. A. Vanover, C. M. Monaco, N. N. Shah, M. Gamboa Castro, S. E. Anderson, T. G. Rudoltz, G. N. Lando, P. Munnilal Tiwari, J. L. Kirschman, N. Willett, Y. C. Jang, P. J. Santangelo, A. V. Bryksin, and J. E. Dahlman. "High-Throughput in Vivo Screen of Functional Mrna Delivery Identifies Nanoparticles for Endothelial Cell Gene Editing." Proc Natl Acad Sci U S A 115, no. 42 (2018): E9944-E52.

- Francia, V., R. M. Schiffelers, P. R. Cullis, and D. Witzigmann. "The Biomolecular Corona of Lipid Nanoparticles for Gene Therapy." Bioconjug Chem 31, no. 9 (2020): 2046-59.

- Cheng, M. H. Y., J. Leung, Y. Zhang, C. Strong, G. Basha, A. Momeni, Y. Chen, E. Jan, A. Abdolahzadeh, X. Wang, J. A. Kulkarni, D. Witzigmann, and P. R. Cullis. "Induction of Bleb Structures in Lipid Nanoparticle Formulations of Mrna Leads to Improved Transfection Potency." Adv Mater 35, no. 31 (2023): e2303370.

- Liu, G. W., E. B. Guzman, N. Menon, and R. S. Langer. "Lipid Nanoparticles for Nucleic Acid Delivery to Endothelial Cells." Pharm Res 40, no. 1 (2023): 3-25.

- Cullis, P. R. , and P. L. Felgner. "The 60-Year Evolution of Lipid Nanoparticles for Nucleic Acid Delivery." Nat Rev Drug Discov (2024).

- Yazdi, M., J. Pohmerer, M. Hasanzadeh Kafshgari, J. Seidl, M. Grau, M. Hohn, V. Vetter, C. C. Hoch, B. Wollenberg, G. Multhoff, A. Bashiri Dezfouli, and E. Wagner. "In Vivo Endothelial Cell Gene Silencing by Sirna-Lnps Tuned with Lipoamino Bundle Chemical and Ligand Targeting." Small 20, no. 42 (2024): e2400643.

- Petersen, D. M. S., R. M. Weiss, K. A. Hajj, S. S. Yerneni, N. Chaudhary, A. N. Newby, M. L. Arral, and K. A. Whitehead. "Branched-Tail Lipid Nanoparticles for Intravenous Mrna Delivery to Lung Immune, Endothelial, and Alveolar Cells in Mice." Adv Healthc Mater 13, no. 22 (2024): e2400225.

- Papp, T. E., J. Zeng, H. Shahnawaz, A. Akyianu, L. Breda, A. Yadegari, J. Steward, R. Shi, Q. Li, B. L. Mui, Y. K. Tam, D. Weissman, S. Rivella, V. Shuvaev, V. R. Muzykantov, and H. Parhiz. "Cd47 Peptide-Cloaked Lipid Nanoparticles Promote Cell-Specific Mrna Delivery." Mol Ther (2025).

- Robles, J. P., M. Zamora, E. Adan-Castro, L. Siqueiros-Marquez, G. Martinez de la Escalera, and C. Clapp. "The Spike Protein of Sars-Cov-2 Induces Endothelial Inflammation through Integrin Alpha5beta1 and Nf-Kappab Signaling." J Biol Chem 298, no. 3 (2022): 101695.

- Yonker, L. M., Z. Swank, Y. C. Bartsch, M. D. Burns, A. Kane, B. P. Boribong, J. P. Davis, M. Loiselle, T. Novak, Y. Senussi, C. A. Cheng, E. Burgess, A. G. Edlow, J. Chou, A. Dionne, D. Balaguru, M. Lahoud-Rahme, M. Arditi, B. Julg, A. G. Randolph, G. Alter, A. Fasano, and D. R. Walt. "Circulating Spike Protein Detected in Post-Covid-19 Mrna Vaccine Myocarditis." Circulation 147, no. 11 (2023): 867-76.

- Avolio, E., M. Carrabba, R. Milligan, M. Kavanagh Williamson, A. P. Beltrami, K. Gupta, K. T. Elvers, M. Gamez, R. R. Foster, K. Gillespie, F. Hamilton, D. Arnold, I. Berger, A. D. Davidson, D. Hill, M. Caputo, and P. Madeddu. "The Sars-Cov-2 Spike Protein Disrupts Human Cardiac Pericytes Function through Cd147 Receptor-Mediated Signalling: A Potential Non-Infective Mechanism of Covid-19 Microvascular Disease." Clin Sci (Lond) 135, no. 24 (2021): 2667-89.

- Perico, L., M. Morigi, M. Galbusera, A. Pezzotta, S. Gastoldi, B. Imberti, A. Perna, P. Ruggenenti, R. Donadelli, A. Benigni, and G. Remuzzi. "Sars-Cov-2 Spike Protein 1 Activates Microvascular Endothelial Cells and Complement System Leading to Platelet Aggregation." Front Immunol 13 (2022): 827146.

- Perico, L., M. Morigi, A. Pezzotta, M. Locatelli, B. Imberti, D. Corna, D. Cerullo, A. Benigni, and G. Remuzzi. "Sars-Cov-2 Spike Protein Induces Lung Endothelial Cell Dysfunction and Thrombo-Inflammation Depending on the C3a/C3a Receptor Signalling." Sci Rep 13, no. 1 (2023): 11392.

- Huynh, T. V., L. Rethi, T. W. Lee, S. Higa, Y. H. Kao, and Y. J. Chen. "Spike Protein Impairs Mitochondrial Function in Human Cardiomyocytes: Mechanisms Underlying Cardiac Injury in Covid-19." Cells 12, no. 6 (2023).

- Schwartz, L., M. Aparicio-Alonso, M. Henry, M. Radman, R. Attal, and A. Bakkar. "Toxicity of the Spike Protein of Covid-19 Is a Redox Shift Phenomenon: A Novel Therapeutic Approach." Free Radic Biol Med 206 (2023): 106-10.

- Sahin, U., K. Kariko, and O. Tureci. "Mrna-Based Therapeutics--Developing a New Class of Drugs." Nat Rev Drug Discov 13, no. 10 (2014): 759-80.

- Forsyth, C. B., L. Zhang, A. Bhushan, B. Swanson, L. Zhang, J. I. Mamede, R. M. Voigt, M. Shaikh, P. A. Engen, and A. Keshavarzian. "The Sars-Cov-2 S1 Spike Protein Promotes Mapk and Nf-Kb Activation in Human Lung Cells and Inflammatory Cytokine Production in Human Lung and Intestinal Epithelial Cells." Microorganisms 10, no. 10 (2022).

- Niu, C., T. Liang, Y. Chen, S. Zhu, L. Zhou, N. Chen, L. Qian, Y. Wang, M. Li, X. Zhou, and J. Cui. "Sars-Cov-2 Spike Protein Induces the Cytokine Release Syndrome by Stimulating T Cells to Produce More Il-2." Front Immunol 15 (2024): 1444643.

- Pishesha, N., T. J. Harmand, and H. L. Ploegh. "A Guide to Antigen Processing and Presentation." Nat Rev Immunol 22, no. 12 (2022): 751-64.

- Palade, G. E. "A Small Particulate Component of the Cytoplasm." J Biophys Biochem Cytol 1, no. 1 (1955): 59-68.

- Embgenbroich, M. , and S. Burgdorf. "Current Concepts of Antigen Cross-Presentation." Front Immunol 9 (2018): 1643.

- Dezsi, L., T. Meszaros, G. Kozma, H. Velkei M, C. Z. Olah, M. Szabo, Z. Patko, T. Fulop, M. Hennies, M. Szebeni, B. A. Barta, B. Merkely, T. Radovits, and J. Szebeni. "A Naturally Hypersensitive Porcine Model May Help Understand the Mechanism of Covid-19 Mrna Vaccine-Induced Rare (Pseudo) Allergic Reactions: Complement Activation as a Possible Contributing Factor." Geroscience 44, no. 2 (2022): 597-618.

- Bakos, T., T. Meszaros, G. T. Kozma, P. Berenyi, R. Facsko, H. Farkas, L. Dezsi, C. Heirman, S. de Koker, R. Schiffelers, K. A. Glatter, T. Radovits, G. Szenasi, and J. Szebeni. "Mrna-Lnp Covid-19 Vaccine Lipids Induce Complement Activation and Production of Proinflammatory Cytokines: Mechanisms, Effects of Complement Inhibitors, and Relevance to Adverse Reactions." Int J Mol Sci 25, no. 7 (2024).

- Barta, B. A., T. Radovits, A. B. Dobos, G. Tibor Kozma, T. Meszaros, P. Berenyi, R. Facsko, T. Fulop, B. Merkely, and J. Szebeni. "Comirnaty-Induced Cardiopulmonary Distress and Other Symptoms of Complement-Mediated Pseudo-Anaphylaxis in a Hyperimmune Pig Model: Causal Role of Anti-Peg Antibodies." Vaccine X 19 (2024): 100497.

- Kozma, G. T., T. Meszaros, P. Berenyi, R. Facsko, Z. Patko, C. Z. Olah, A. Nagy, T. G. Fulop, K. A. Glatter, T. Radovits, B. Merkely, and J. Szebeni. "Role of Anti-Polyethylene Glycol (Peg) Antibodies in the Allergic Reactions to Peg-Containing Covid-19 Vaccines: Evidence for Immunogenicity of Peg." Vaccine 41, no. 31 (2023): 4561-70.

- Ali, Y. M., M. Ferrari, N. J. Lynch, S. Yaseen, T. Dudler, S. Gragerov, G. Demopulos, J. L. Heeney, and W. J. Schwaeble. "Lectin Pathway Mediates Complement Activation by Sars-Cov-2 Proteins." Front Immunol 12 (2021): 714511.

- Gibson, B. G., T. E. Cox, and K. J. Marchbank. "Contribution of Animal Models to the Mechanistic Understanding of Alternative Pathway and Amplification Loop (Ap/Al)-Driven Complement-Mediated Diseases." Immunol Rev 313, no. 1 (2023): 194-216.

- Brouwer, N., K. M. Dolman, R. van Zwieten, E. Nieuwenhuys, M. Hart, L. A. Aarden, D. Roos, and T. W. Kuijpers. "Mannan-Binding Lectin (Mbl)-Mediated Opsonization Is Enhanced by the Alternative Pathway Amplification Loop." Mol Immunol 43, no. 13 (2006): 2051-60.

- Risso, V., E. Lafont, and M. Le Gallo. "Therapeutic Approaches Targeting Cd95l/Cd95 Signaling in Cancer and Autoimmune Diseases." Cell Death Dis 13, no. 3 (2022): 248.

- Ramirez-Labrada, A., C. Pesini, L. Santiago, S. Hidalgo, A. Calvo-Perez, C. Onate, A. Andres-Tovar, M. Garzon-Tituana, I. Uranga-Murillo, M. A. Arias, E. M. Galvez, and J. Pardo. "All About (Nk Cell-Mediated) Death in Two Acts and an Unexpected Encore: Initiation, Execution and Activation of Adaptive Immunity." Front Immunol 13 (2022): 896228.

- Wiley, S. R., K. Schooley, P. J. Smolak, W. S. Din, C. P. Huang, J. K. Nicholl, G. R. Sutherland, T. D. Smith, C. Rauch, C. A. Smith, and et al. "Identification and Characterization of a New Member of the Tnf Family That Induces Apoptosis." Immunity 3, no. 6 (1995): 673-82.

- Schroder, K., P. J. Hertzog, T. Ravasi, and D. A. Hume. "Interferon-Gamma: An Overview of Signals, Mechanisms and Functions." J Leukoc Biol 75, no. 2 (2004): 163-89.

|

Disclaimer/Publisher’s Note: The statements, opinions and data contained in all publications are solely those of the individual author(s) and contributor(s) and not of MDPI and/or the editor(s). MDPI and/or the editor(s) disclaim responsibility for any injury to people or property resulting from any ideas, methods, instructions or products referred to in the content. |

© 2025 by the authors. Licensee MDPI, Basel, Switzerland. This article is an open access article distributed under the terms and conditions of the Creative Commons Attribution (CC BY) license (http://creativecommons.org/licenses/by/4.0/).