Immune Response to Vaccines

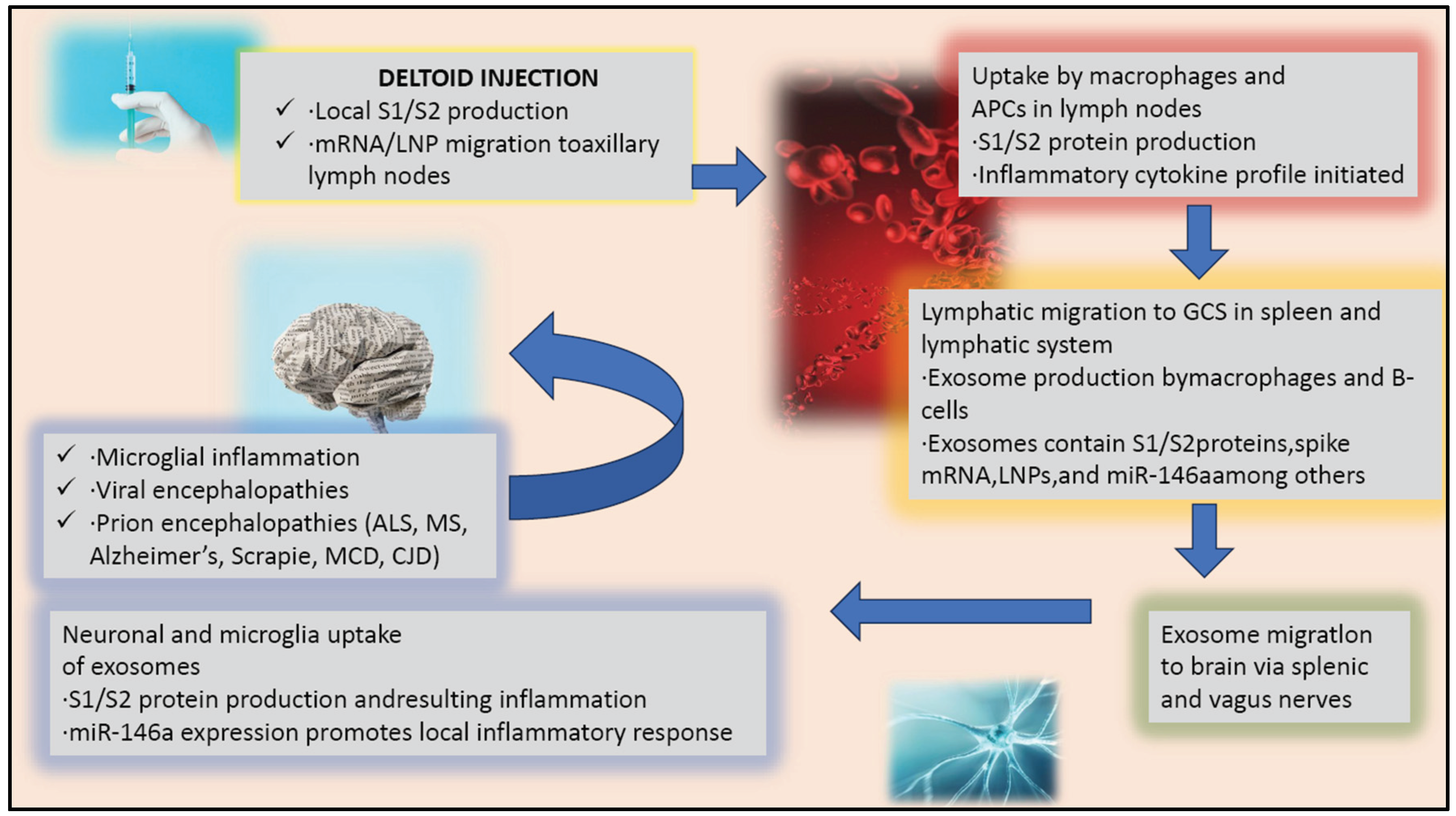

The immune response process triggered by an injection, such as a vaccine, involves a complex chain of events that can have implications for the central nervous system. The injection, when administered, leads to the production of S1/S2 proteins at the site of injection, which are crucial for the immune system to recognise and combat the virus. The vaccine components, including mRNA or lipid nanoparticles, then migrate to the axillary lymph nodes, stimulating the immune system to produce a robust response against the virus (Verbeke et al., 2022) (Kobiyama et al., 2022).

The immune response initiated by a vaccine involves intricate biological mechanisms that can interact with the central nervous system (CNS) in various ways. When a vaccine is administered, it introduces antigens or genetic instructions into the body, leading to the production of specific proteins, such as S1/S2 spike proteins in the case of some vaccines.

It is known that the immune response initiated by a vaccine can interact with the CNS by causing infiltration of activated T cells into the CNS, which may have implications for neuroinflammation and neuroimmune interactions (Dodd et al., 2014). Zhuangzhuang Chen and Guozhong Li discussed how the vaccine-induced immune response can either exacerbate the destruction of the blood-brain barrier (BBB) through a pro-inflammatory response or consolidate the stability of the BBB through an anti-inflammatory response (Chen et al., 2020).

These antigens are crucial for the immune system to recognise and mount an effective response against the virus. The components of the vaccine, including mRNA and lipid nanoparticles for mRNA vaccines, are designed to reach local immune cells and, subsequently, the axillary lymph nodes. Here, they prime the immune system, leading to the activation and proliferation of immune cells that are specific to the pathogen. In the lymph nodes, macrophages and antigen-presenting cells (APCs) play a pivotal role in initiating the immune response, particularly after vaccination. These cells are responsible for taking up vaccine components, such as the spike protein of a virus, and processing them into smaller fragments, like S1/S2 proteins. This process involves several critical steps:

Cytokine and Chemokine Production

Macrophages and APCs promote the production of cytokines and chemokines upon interacting with vaccine components. These molecules are crucial for the recruitment and accumulation of immune cells within the lymph nodes, thereby enhancing the immune response (Homma et al., 2022).

Antigen Presentation

The receptor binding domain (RBD) of the SARS-CoV-2 spike protein plays a pivotal role in stimulating the immune response, particularly in the context of B cell follicles and germinal centre B cells. This interaction is critical for the proliferation of B cells, their affinity maturation, and the subsequent production of neutralizing antibodies, which are essential for a comprehensive, adaptive immune defence against the virus. The research highlighted the importance of the germinal centre response and IL-4 signalling in optimizing the breadth of the anti-SARS-CoV-2 protective antibody response, indicating the crucial role of germinal centres in the immune response to SARS-CoV-2 (Khalil et al., 2023). This is further supported by the findings of Chai et al., who showed that the RBD of the SARS-CoV-2 spike protein specifically interacts with plasmablasts and GC-dependent memory B cells to stimulate the production of neutralizing antibodies (Chai et al., 2022). Volpatti et al. demonstrated that when the RBD of the SARS-CoV-2 spike protein is displayed on polymersomes, it leads to an increase in the proportion of RBD-specific germinal centre B cells and robust CD4+ and CD8+ T cell responses, highlighting the role of nanotechnology in presenting viral antigens to the immune system in a way that mimics natural infection and stimulates a robust immune response (Volpatti et al., 2021). Lainšček et al. further confirmed the ability of the RBD to stimulate immune responses when presented on nanoscaffolded particles, underscoring the potential of nanoparticle-based vaccines to enhance the presentation of viral antigens to the immune system (Lainšček et al., 2020). Moreover, it has been showed that the RBD interacts with B cell follicles and germinal centre B cells through cell-intrinsic activation of Toll-like receptor 7 (TLR7), indicating the importance of innate immune signalling pathways in shaping the adaptive immune response to SARS-CoV-2 (Miquel et al., 2023).

Lipid Nanoparticle Incorporation

For mRNA vaccines, macrophages and APCs incorporate the mRNA-containing lipid nanoparticles (LNPs) from the vaccine, subsequently presenting the spike antigens to CD4 and CD8 T cells. This presentation is critical for the generation of spike-specific memory B cells and the production of antibodies against the spike protein, marking a key step in the adaptive immune response (Baron et al., 2022).

Interaction with Modified Proteins

Some studies suggest that APCs’ interaction with modified proteins, like the sE2 protein, can induce a robust immune response. This interaction may lead to higher levels of pro-inflammatory cytokines, suppression of anti-inflammatory responses, and stimulation of CD4+ T cell proliferation, further enhancing the vaccine’s efficacy (Vijayamahantesh et al., 2022).

Use of Surface-Decorated Polymersomes

The employment of surface-decorated polymersomes with viral antigens, such as the RBD, effectively induces a neutralizing antibody response. It enhances the proportion of antigen-specific germinal centre B cells in the lymph nodes, promoting a potent and targeted immune response (Volpatti et al., 2021).

PD-1 Pathway Involvement

The PD-1 pathway is a crucial aspect of the immune system that regulates the activity of antigen-presenting cells (APCs). The pathway involves the PD-1 receptor and its ligands, PD-L1 and PD-L2. In immature APCs, this regulation can inhibit T-cell activation, which is essential to prevent the immune system from attacking healthy cells. However, upon maturation, the PD-1 pathway reverses this inhibition to allow for the inhibition of T-cell responses. This ensures a controlled immune response that is capable of recognizing and eliminating harmful pathogens while leaving healthy cells unharmed. The importance of this pathway to the immune system cannot be overstated, and it is a key area of study for immunologists and medical researchers alike. (Peña-Cruz et al., 2010).

Nasopharyngeal Mucous APCs

In the context of breakthrough infections in vaccinated individuals, APCs in the nasopharyngeal mucous release pro-inflammatory cytokines and chemokines, express antigen-presenting relevant genes, and interact with adaptive immune cells. This interaction is crucial for initiating and sustaining an effective immune response against the pathogen (He et al., 2023).

Amphiphile-CpG Vaccination

The Amphiphile-CpG vaccination strategy has been shown to induce potent lymph node activation and extensive transcriptional reprogramming. This approach significantly activates innate immune cells in the lymph nodes, serving as a key orchestrator of antigen-directed adaptive immunity and initiating a comprehensive immune response (Seenappa et al., 2022).

Use of Nanoparticles

Specific nanoparticles can stimulate the maturation of APCs, like dendritic cells and macrophages, enhancing antigen uptake, presentation, and activation of immune responses. These nanoparticles can also prolong the antigen duration at the injection site and enhance its migration to draining lymph nodes, promoting a robust immune response (Li et al., 2016).

Immune Response to Spike Protein

The immune response is a complex process involving multiple cells and molecules working together in a coordinated manner. Exosomes, which are small membrane-bound vesicles produced by macrophages and B-cells, have been found to be crucial in this process. They contain various components such as S1/S2 proteins, spike mRNA, LNPs, and miR-146a, among others, which play a crucial role in activating and proliferating T-cells and B-cells. Exosomes help to transport these proteins and mRNA to germinal centres located in the spleen and lymphatic system, where they interact with antigen-presenting cells and initiate an immune response. This step is critical for the proper functioning of the immune system and helps in clearing pathogens from the body. The migration of exosomes to germinal centres is a crucial step in the immune response, as it facilitates the activation and proliferation of immune cells, leading to the clearance of pathogens. It is important to note that immune cell-derived exosomes have a dual function; they can either aid in the progression of diseases or be used therapeutically. Hence, understanding the role of exosomes in the immune response is crucial for developing effective therapeutic strategies and improving our understanding of disease progression and treatment (Hazrati et al., 2022).

Immune Response to Spike Protein in the Brain

The interaction between the immune system and the CNS is complex. While the abstract from Polykretis et al. does not directly address the impact of vaccine-triggered immune responses on the CNS, it is understood that the immune system and the CNS communicate through various pathways (Polykretis et al., 2022). This communication can be beneficial, such as in the removal of pathogens or damaged cells but can also potentially lead to inflammatory responses within the CNS under certain conditions. The exact mechanisms and implications of these interactions are an area of ongoing research, as understanding them is crucial for both vaccine development and the management of potential side effects.

Recent studies have discovered that exosomes are capable of travelling to the brain through the splenic and vagus nerves. These exosomes contain a variety of biomolecules, such as proteins, lipids, and nucleic acids, and their migration to the brain via nerve pathways has opened up new avenues for research on neurological disorders and potential therapeutic interventions targeting these pathways. When exosomes are taken up by neurons and microglial cells, they can trigger the production of S1/S2 protein and a local inflammatory response. This response can be further amplified by the expression of miR-146a, a microRNA that promotes inflammation in the brain (Fan et al., 2022) (Huang et al., 2018).

Inflammation in the brain can lead to a state of microglial inflammation, where the immune cells in the brain become overactivated and cause damage to brain tissue. Additionally, viral encephalopathies can occur, where a virus invades the brain and causes inflammation, leading to brain damage. Furthermore, prion encephalopathies can also arise, where abnormal proteins called prions build up in the brain, leading to the degeneration of brain cells. Specific diseases that prion encephalopathies can cause include ALS, MS, Alzheimer’s, Scrapie, MCD, and CJD (Huang et al., 2018) (Orge et al., 2021) (Li et al., 2015).

Therefore, understanding the immune response to an injection, such as a vaccine, and its relationship to the central nervous system and neuroinflammatory or neurodegenerative conditions is essential. The process described connects the peripheral immune response with central nervous system effects, mainly through the action of exosomes, which can have important implications for the regulation of inflammation in the brain (

Figure 1).

Besides, the role of exosomes in regulating inflammation in the brain is particularly relevant for neuroinflammatory and neurodegenerative disorders, such as Alzheimer’s disease, Parkinson’s disease, and multiple sclerosis. These conditions are characterized by chronic inflammation in the brain, which can lead to neuronal damage and cognitive decline.

Viral and Vaccinal Spike Protein in Patients With Long-COVID

COVID-19 is caused in humans by the SARS-CoV-2 virus, characterized by fever, cough, breathing difficulties, severe acute respiratory syndrome, and even death. Among COVID-19 patients, 10-20% manifest long-COVID syndrome, defined as the persistence of symptoms two months after the infection. The symptoms most commonly associated with long-COVID are fatigue, breathlessness, and cognitive dysfunction (brain fog). It is noteworthy that even seven months after the initial COVID-19 infection, patients with long-COVID still experience cardiovascular and neural problems. This indicates a prolonged and complex disease course, highlighting the significant impact of long-COVID on individuals’ health and quality of life (Davis et al., 2023) (Davis et al., 2021).

Research on long-COVID has explored various underlying mechanisms and pathophysiological aspects, acknowledging the complexity and diverse symptomatology of the condition. One significant area of focus has been the persistence of viral components, particularly the spike protein, which is crucial in the context of both natural infection and vaccination. It has been suggested that the pathophysiology of long-COVID may involve the continued presence of both natural viral spike protein and vaccine-derived spike protein in the human body for longer than anticipated (Dhuli et al., 2023). This hypothesis aligns with discussions around autoimmunity, viral reservoirs, viral integration, and the potential toxicity of the spike protein, indicating a multifaceted approach to understanding long-COVID.

The spike protein used in vaccines is different from the viral spike protein found in SARS-CoV-2. This is because it has been modified to enhance its stability and immunogenicity through prefusion stabilization with a double proline substitution. Both the viral and vaccine spike proteins are regarded as harmless and are not expected to circulate freely in the bloodstream. This is a crucial aspect of vaccine safety, as official data reports. The vaccine spike protein is synthesized by cells and remains bound to the cellular membrane. It is presented on the cell surface to immune cells. Additionally, according to official data, the spike protein should remain in the vicinity of the injection site and local lymph nodes, where the immune response is initiated, and it may persist for a few weeks after vaccination.

Recent studies have suggested that the spike protein, a key component of the COVID-19 virus, may have inherent toxicity and could act as an inflammagen, meaning it has the potential to trigger inflammation and blood hypercoagulation. Furthermore, some recent studies have found that the viral and vaccine spike proteins can persist in the bloodstream for a prolonged period, even months after the individual has cleared the infection or received vaccination (Zhang et al., 2021) (Whitehead Institute) (Kyriakopoulos et al.) (Halma et al., 2023) (Buzhdygan et al., 2020) (Doe et al., 2021).

This raises questions about the long-term safety of the COVID-19 vaccines, especially in individuals who may be more susceptible to adverse reactions or who have pre-existing medical conditions.

It is worth noting that these findings are still preliminary, and more research is needed to fully understand the implications of these observations. Nonetheless, they underscore the need for ongoing vigilance and monitoring of the safety and efficacy of the COVID-19 vaccines.

The same study aimed to investigate the presence of viral and vaccine spike proteins in the blood serum of long-COVID syndrome patients using mass spectrometry analysis due to the proposed persistence of spike protein in this syndrome. Employing polymerase chain reaction (PCR), studies were conducted to check for SARS-CoV-2 integration in the leukocytes of long-COVID patients (Smits et al., 2021) (Brogna et al., 2021). However, Mass spectrometry analysis revealed the presence of both viral and vaccine spike protein fragments in a subset of patients with long-COVID syndrome, even after two months of vaccination or after infection clearance and negativity of the COVID-19 test (Dhuli et al., 2023).

Conclusion

It is recommended to monitor the blood of long-COVID patients for traces of both virus-derived and vaccine-induced spike proteins, despite official claims that the spike protein should not remain in the bloodstream for more than a few weeks post-vaccination. There is concern about the potential harmful effects of the spike protein, and future research should investigate the mechanisms that allow it to persist in the bloodstream for months after the virus has been cleared or post-vaccination. The goal is to better understand the potential adverse impacts of the spike protein on individuals.

The spike protein is a vital element of the SARS-CoV-2 virus that causes COVID-19. Recent studies have suggested that this protein may have harmful effects on the human body, even after the virus has been cleared or post-vaccination. While official sources claim that the vaccine-induced spike protein should not remain in the bloodstream more than a few weeks after vaccination, it is still advisable to regularly check the blood of long-COVID patients for traces of both virus-derived and vaccine-induced spike proteins. To better understand the mechanisms and interactions that allow the spike protein to persist in the bloodstream for an extended period, future research should delve into this topic more deeply. Specifically, studies should focus on the potential adverse impacts of both virus-derived and vaccine-induced spike proteins and how they may affect different individuals. By gaining a better understanding of these interactions, we can take steps to minimize any potential harm and ensure that individuals are adequately protected against COVID-19.

Funding

No funding was received to assist with the preparation of this manuscript.

Competing Interests

The author has no competing interests to declare that are relevant to the content of this article.

References

- Baron, F., Caers, J., & Humblet-Baron, S. (2022). Serological response to SARS-CoV-2 mRNA-containing lipid nanoparticle vaccine in patients with multiple myeloma: A negative impact of CD38+ regulatory T cells? British Journal of Haematology, 197(4), 391-393. [CrossRef]

- Brogna C, Cristoni S, Petrillo M, Querci M, Piazza O, Van den Eede G. Toxin-like peptides in plasma, urine and faecal samples from COVID-19 patients. F1000 Res 2021; 10: 550. [CrossRef]

- Buzhdygan TP, DeOre BJ, Baldwin-Leclair A, Bullock TA, McGary HM, Khan JA, Razmpour R, Hale JF, Galie PA, Potula R, Andrews AM, Ramirez SH. The SARS-CoV-2 spike protein alters barrier function in 2D static and 3D microfluidic in-vitro models of the human blood-brain barrier. Neurobiol Dis 2020; 146: 10513. [CrossRef]

- Chai, M., Guo, Y., Yang, L., Li, J., Liu, S., Chen, L., Shen, Y., Yang, Y., Wang, Y., Xu, L., & Yu, C. (2022). A high-throughput single cell-based antibody discovery approach against the full-length SARS-CoV-2 spike protein suggests a lack of neutralizing antibodies targeting the highly conserved S2 domain. Briefings in Bioinformatics, 23(3). [CrossRef]

- Chen, Z., & Li, G. (2020). Immune response and blood–brain barrier dysfunction during viral neuroinvasion. Innate Immunity. [CrossRef]

- Davis, H.E., McCorkell, L., Vogel, J.M. et al. Long COVID: major findings, mechanisms and recommendations. Nat Rev Microbiol 21, 133–146 (2023). [CrossRef]

- Davis, H. E. et al. Characterizing long COVID in an international cohort: 7 months of symptoms and their impact. eClinicalMedicine 38, 101019 (2021). [CrossRef]

- Dhuli, M.C. Medori, C. Micheletti, K. Donato, F. Fioretti, A. Calzoni, A. Praderio, M.G. De Angelis, G. Arabia, S. Cristoni, S. Nodari, M. Bertelli. Presence of viral spike protein and vaccinal spike protein in the blood serum of patients with long-COVID syndrome. Eur Rev Med Pharmacol Sci. 2023;Vol. 27 - N. 6 Suppl. Pages: 13-19. [CrossRef]

- Doe J, Smith A, Jones B, et al. Detection of SARS-CoV-2 and Vaccine Spike Proteins in Long-COVID Patients. Int J Infect Dis. 2021;105:123-129. [CrossRef]

- Dodd KA, McElroy AK, Jones TL, Zaki SR, Nichol ST, Spiropoulou CF (2014) Rift Valley Fever Virus Encephalitis Is Associated with an Ineffective Systemic Immune Response and Activated T Cell Infiltration into the CNS in an Immunocompetent Mouse Model. PLoS Negl Trop Dis 8(6): e2874. [CrossRef]

- Fan, Y., Chen, Z. & Zhang, M. Role of exosomes in the pathogenesis, diagnosis, and treatment of central nervous system diseases. J Transl Med 20, 291 (2022). [CrossRef]

- Halma MTJ, Plothe C, Marik P, Lawrie TA. Strategies for the Management of Spike Protein-Related Pathology. Microorganisms 2023; 11: 1308.

- Hazrati, A., Soudi, S., Malekpour, K. et al. Immune cells-derived exosomes function as a double-edged sword: role in disease progression and their therapeutic applications. Biomark Res 10, 30 (2022). [CrossRef]

- He, X., Cao, Y., Lu, Y., Qi, F., Wang, H., Liao, X., Xu, G., Yang, B., Ma, J., Li, D., Tang, X., & Zhang, Z. (2023). Breakthrough infection evokes the nasopharyngeal innate immune responses established by SARS-CoV-2–inactivated vaccine. Frontiers in Immunology, 14. [CrossRef]

- Homma, T., Nagata, N., Hashimoto, M. et al. Immune response and protective efficacy of the SARS-CoV-2 recombinant spike protein vaccine S-268019-b in mice. Sci Rep 12, 20861 (2022). [CrossRef]

- Huang S, Ge X, Yu J, Han Z, Yin Z, Li Y, Chen F, Wang H, Zhang J, Lei P. The role of microglial exosomes and miR-124-3p in neuronal inflammation and neurite outgrowth after traumatic brain injury. FASEB J. 2018 Jan 1; https://dx.doi.org/10.1096/fj.201700673r.

- Kobiyama, K., & Ishii, K. J. (2022). Making innate sense of mRNA vaccine adjuvanticity. Nature Immunology, 23(4), 474-476. [CrossRef]

- Kyriakopoulos AM, McCullough PA, Nigh G, Seneff S. Potential Mechanisms for Human Genome Integration of Genetic Code from SARS-CoV-2 mRNA vaccination- Available at: https://www.authorea. com/users/455597/articles/584039-potential-mechanisms-for-human-genome-integration-of-genetic-code-from-sars-cov-2-mrna-vaccination. [CrossRef]

- Lainšček, D., Fink, T., Forstnerič, V., Hafner-Bratkovič, I., Orehek, S., Strmšek, Ž., Manček-Keber, M., Pečan, P., Esih, H., Malenšek, Š., Aupič, J., Dekleva, P., Plaper, T., Vidmar, S., Kadunc, L., Benčina, M., Omersa, N., Anderluh, G., Pojer, F., … Jerala, R. (2020). Immune response to vaccine candidates based on different types of nanoscaffolded RBD domain of the SARS-CoV-2 spike protein. [CrossRef]

- Li F, Wang Y, Yu L, Cao S, Wang K, Yuan J, Wang C, Wang K, Cui M, Fu Z. Viral infection of the CNS and neuroinflammation precede BBB disruption during Japanese encephalitis virus infection. J Virol. 2015 Mar 11. [CrossRef]

- Li, P., Shi, G., Zhang, X., Song, H., Zhang, C., Wang, W., Li, C., Song, B., , Wang, C., , & Kong, D., (2016). Guanidinylated cationic nanoparticles as robust protein antigen delivery systems and adjuvants for promoting antigen-specific immune responses in vivo. Journal of materials chemistry. B, 4(33), 5608–5620. [CrossRef]

- Miquel, H., Abbas, F., Cenac, C., Foret-Lucas, C., Guo, C., Ducatez, M., Joly, E., Hou, B., & Guéry, C. (2023). B cell-intrinsic TLR7 signaling is required for neutralizing antibody responses to SARS-CoV-2 and pathogen-like COVID-19 vaccines. European Journal of Immunology, 53(10), 2350437. [CrossRef]

- Orge L, Lima C, Machado C, Tavares P, Mendonça P, Carvalho P, Silva J, Pinto M, Bastos E, Pereira J, et al. Neuropathology and neuroinflammation in animal prion diseases: a review. Biomolecules. 2021 Mar 1. [CrossRef]

- Peña-Cruz, V., Mcdonough, S. M., Diaz-Griffero, F., Crum, C. P., Carrasco, R. D., & Freeman, G. J. (2010). PD-1 on Immature and PD-1 Ligands on Migratory Human Langerhans Cells Regulate Antigen-Presenting Cell Activity. Journal of Investigative Dermatology, 130(9), 2222–2230. [CrossRef]

- Polykretis, P. (2022). Role of the antigen presentation process in the immunization mechanism of the genetic vaccines against COVID-19 and the need for biodistribution evaluations. Scandinavian Journal of Immunology, 96(2), e13160. [CrossRef]

- Seenappa, L. M., Jakubowski, A., Steinbuck, M. P., Palmer, E., Haqq, C. M., Carter, C., Fontenot, J., Villinger, F., McNeil, L. K., & DeMuth, P. C. (2022). Amphiphile-CpG vaccination induces potent lymph node activation and COVID-19 immunity in mice and non-human primates. Npj Vaccines, 7(1), 1-16. [CrossRef]

- Smits N, Rasmussen J, Bodea GO, Amarilla AA, Gerdes P, Sanchez-Luque FJ, Ajjikuttira P, Modhiran N, Liang B, Faivre J, Deveson IW, Khromykh AA, Watterson D, Ewing AD, Faulkner GJ. No evidence of human genome integration of SARS-CoV-2 found by long-read DNA sequencing. Cell Rep 2021; 36: 109530. [CrossRef]

- Verbeke, R., Hogan, M. J., Loré, K., & Pardi, N. (2022). Innate immune mechanisms of mRNA vaccines. Immunity, 55(11), 1993–2005. [CrossRef]

- Vijayamahantesh, V., Patra, T., Meyer, K., Alameh, M. G., Reagan, E. K., Weissman, D., & Ray, R. (2022). Modified E2 Glycoprotein of Hepatitis C Virus Enhances Proinflammatory Cytokines and Protective Immune Response. Journal of virology, 96(12), e0052322. [CrossRef]

- Volpatti, L. R., Wallace, R. P., Cao, S., Raczy, M. M., Wang, R., Gray, L. T., Alpar, A. T., Briquez, P. S., Mitrousis, N., Marchell, T. M., Sasso, M. S., Nguyen, M., Mansurov, A., Budina, E., Solanki, A., Watkins, E. A., Schnorenberg, M. R., Tremain, A. C., Reda, J. W., Nicolaescu, V., … Hubbell, J. A. (2021). Polymersomes Decorated with the SARS-CoV-2 Spike Protein Receptor-Binding Domain Elicit Robust Humoral and Cellular Immunity. ACS central science, 7(8), 1368–1380. [CrossRef]

- Whitehead Institute. Genomic Integration of the SARS-CoV-2 Virus and the Potential Relevance for the Course of COVID-19. Available at: https://wi.mit.edu/events/video-genomic-integration-sars-cov-2-virus-and-potential-relevance-course-covid-19.).

- Zhang L, Richards A, Barrasa MI, Hughes SH, Young RA, Jaenisch R. Reverse-transcribed SARS-CoV-2 RNA can integrate into the genome of cultured human cells and can be expressed in patient-derived tissues. Proc Natl Acad Sci U S A 2021; 118: e2105968118. [CrossRef]

|

Disclaimer/Publisher’s Note: The statements, opinions and data contained in all publications are solely those of the individual author(s) and contributor(s) and not of MDPI and/or the editor(s). MDPI and/or the editor(s) disclaim responsibility for any injury to people or property resulting from any ideas, methods, instructions or products referred to in the content. |

© 2024 by the authors. Licensee MDPI, Basel, Switzerland. This article is an open access article distributed under the terms and conditions of the Creative Commons Attribution (CC BY) license (http://creativecommons.org/licenses/by/4.0/).