Submitted:

11 February 2025

Posted:

12 February 2025

You are already at the latest version

Abstract

Keywords:

1. Introduction

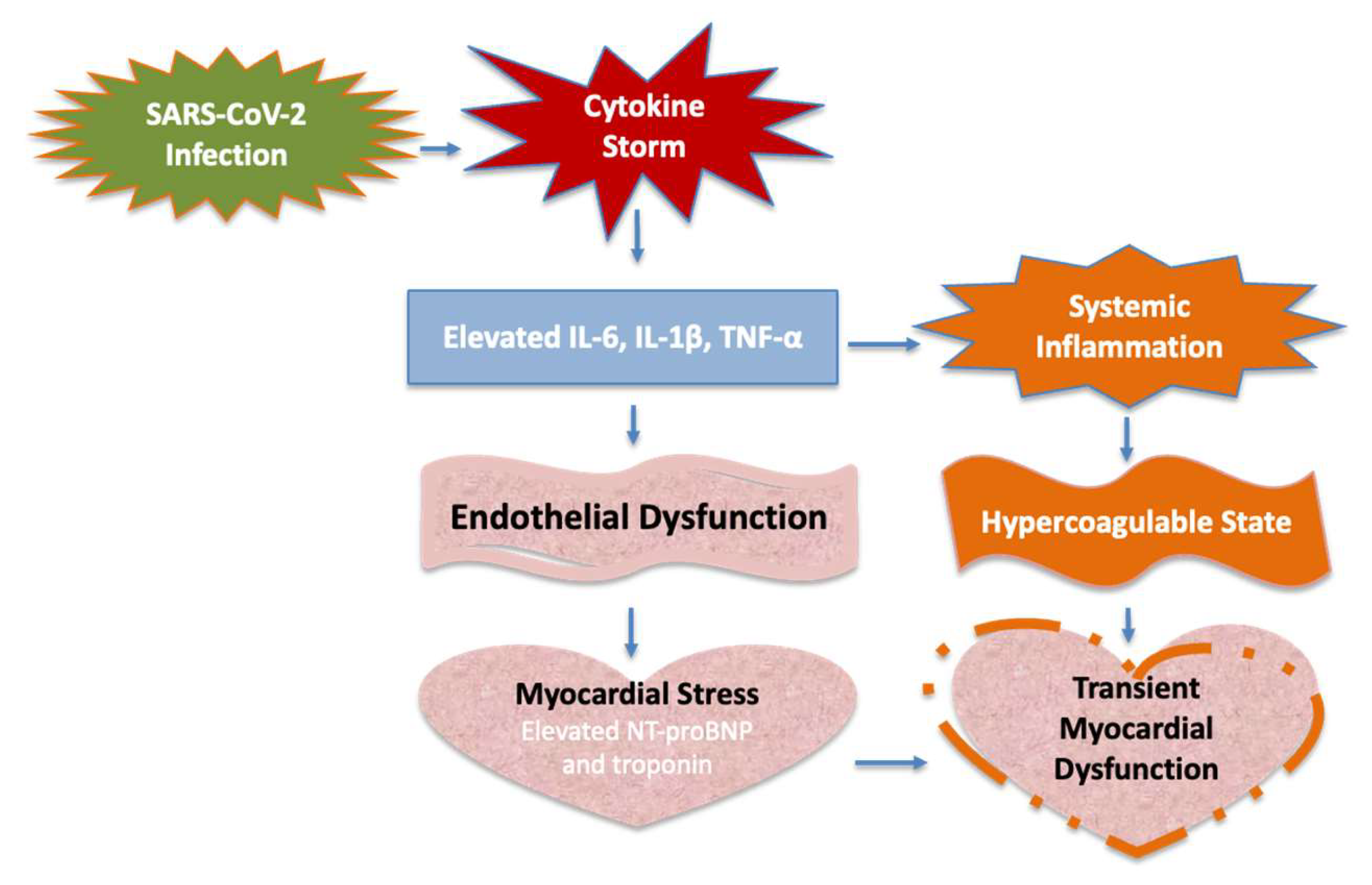

Molecular Pathophysiology

2. Results

2.1. Demographics

2.2. Clinical Presentation

2.3. Therapies and Interventions

2.4. Outcomes

3. Discussion

Vaccination and MIS-C

4. Methods

4.1. Study Design and Setting

4.2. Data Collection

4.3. Interventions

4.4. Outcome Measures

4.5. Statistical Analysis

5. Conclusions

Author Contributions

Funding

Institutional Review Board Statement

Informed Consent Statement

Data Availability Statement

Conflicts of Interest

Abbreviations

| MDPI | Multidisciplinary Digital Publishing Institute |

| DOAJ | Directory of open access journals |

| TLA | Three letter acronym |

| LD | Linear dichroism |

Appendix A

| Case | Date | Age & Gender | Symptoms | Key Laboratory Findings | Cardiac Involvement | Treatment & Outcome |

| 1 | Apr 2020 | 8y Male | High fever, abdominal pain, vomiting, diarrhea, shock | Elevated CRP, PCT, ESR, IL-6, ferritin, NT-ProBNP (14500 pg/ml), troponin (840 ng/ml), DD 6017 ng/ml | Moderate-severe biventricular dysfunction, valve insufficiency | IVIG, methylprednisolone, heparin, hydroxychloroquine, complete recovery |

| 2 | Dec 2020 | 13y Male | High fever, headache, neck pain, conjunctival injection, shock | Elevated CRP, PCT, ESR, IL-6, NT-ProBNP (5400 pg/ml), troponin (1400 ng/ml), DD 1400 ng/ml | Moderate left ventricular dysfunction, valve insufficiency | IVIG, methylprednisolone, heparin, aspirin, complete recovery |

| 3 | Jan 2021 | 4y Male | High fever, abdominal pain, vomiting, diarrhea, malaise | Elevated CRP, PCT, ESR, NT-ProBNP (1579 pg/ml), DD 2578 ng/ml | Normal echocardiogram | IVIG, methylprednisolone, aspirin, complete recovery |

| 4 | Aug 2021 | 11y Female | High fever, abdominal pain, diarrhea, shock | Elevated CRP, PCT, ESR, IL-6, ferritin, NT-ProBNP (8700 pg/ml), troponin (672 ng/ml), DD 2500 ng/ml | Mild-moderate biventricular dysfunction | IVIG, methylprednisolone, heparin, aspirin, complete recovery |

| 5 | Sep 2021 | 5y Male | High fever, cervical pain, abdominal pain, vomiting, diarrhea, shock, rash | Elevated NT-ProBNP (3600 pg/ml), troponin (100 ng/ml), DD 2400 ng/ml | Mild biventricular dysfunction | IVIG, methylprednisolone, aspirin, complete recovery |

| 6 | Oct 2021 | 14y Male | High fever, abdominal pain, vomiting, KD, shock | Elevated CRP, PCT, ESR, ferritin, troponin (1165 ng/ml), NT-ProBNP (680 pg/ml), DD 4040 ng/ml | Mild systolic biventricular dysfunction | IVIG, methylprednisolone, heparin, aspirin, complete recovery |

| 7 | Oct 2021 | 9y Female | High fever, abdominal pain, vomiting, diarrhea | Elevated CRP, PCT, ESR, NT-ProBNP (4213 pg/ml), DD 2334 ng/ml | Normal echocardiogram | IVIG, methylprednisolone, aspirin, complete recovery |

| 8 | Dec 2021 | 17m Female | High fever, abdominal pain, vomiting, anorexia, conjunctival hyperemia, KD | Elevated CRP, PCT, ESR, NT-ProBNP (668 pg/ml), DD 1703 ng/ml | Normal echocardiogram | IVIG, methylprednisolone, aspirin, complete recovery |

| 9 | Feb 2022 | 11y Male | High fever, rash, edema, conjunctival hyperemia, rash, toracic pain, shock, KD | Elevated CRP, PCT, ESR, ferritin, NT-ProBNP (11224 pg/ml), troponin (6222 ng/ml), DD 1265 ng/ml | Severe myocardial injury | IVIG, methylprednisolone, aspirin, complete recovery |

| 10 | Apr 2022 | 6y Male | High fever, headache, malaise, abdominal pain, diarrhea, rash, cracked lips, KD | Elevated CRP, ESR, PCT, IL-6, ferritin, NT-ProBNP (6361 pg/ml),troponin 127 ng/ml, DD 4769 ng/ml | Mild left ventricular dysfunction | IVIG, methylprednisolone, aspirin, heparin, complete recovery |

| 11 | Jun 2022 | 12m Female | High fever, irritability, urticarial rash, KD | Elevated CRP, PCT, ESR, NT-ProBNP (618 pg/ml) | Normal echocardiogram | IVIG, methylprednisolone, aspirin, complete recovery |

| 12 | Aug 2023 | 15y Female | High fever, abdominal pain, vomiting, rash, edema, headache, conjunctival hyperemia,KD | Elevated CRP, PCT, ESR, NT-ProBNP (1200 pg/ml), DD 1756 pg/ml | Pericarditis | IVIG, aspirin, antibiotics, complete recovery |

| 13 | Aug 2023 | 9y Male | High fever, malaise, headache, edema, rash, meningism, conjunctival hyperemia, shock, KD | Elevated CRP, PCT, ESR, NT-ProBNP (3700 pg/ml), troponin (64 ng/ml), DD 1653 pg/ml | Mild pericardial effusion, myocarditis | IVIG, methylprednisolone, aspirin, heparin, complete recovery |

| 14 | May 2024 | 2y Female | High fever, pharyngotonsillitis, strawberry tongue, abdominal pain, conjunctival hyperemia, edema, KD | Elevated CRP, PCT, ESR, NT-ProBNP (1800 pg/ml), DD 12827 ng/ml | Normal echocardiogram | IVIG, methylprednisolone, aspirin, antibiotics, complete recovery |

| 15 | Aug 2024 | 10y Female | High fever, rash, abdominal pain, hepatomegaly, jaundice, meningism, KD | Elevated CRP, PCT, ESR, NT-ProBNP (1380 pg/ml), DD 4100 ng/ml | Mild pericardial effusion | IVIG, methylprednisolone, aspirin, heparin, antibiotics, complete recovery |

References

- Henderson LA, Canna SW, Friedman KG, Gorelik M, Lapidus SK, Bassiri H, Behrens EM, Ferris A, Kernan KF, Schulert GS, Seo P, F Son MB, Tremoulet AH, Yeung RSM, Mudano AS, Turner AS, Karp DR, Mehta JJ. American College of Rheumatology Clinical Guidance for Multisystem Inflammatory Syndrome in Children Associated With SARS-CoV-2 and Hyperinflammation in Pediatric COVID-19: Version 1. Arthritis Rheumatol. 2020 Nov;72(11):1791-1805.

- Henderson LA, Canna SW, Friedman KG, Gorelik M, Lapidus SK, Bassiri H, Behrens EM, Ferris A, Kernan KF, Schulert GS, Seo P, Son MBF, Tremoulet AH, Yeung RSM, Mudano AS, Turner AS, Karp DR, Mehta JJ. American College of Rheumatology Clinical Guidance for Multisystem Inflammatory Syndrome in Children Associated With SARS-CoV-2 and Hyperinflammation in Pediatric COVID-19: Version 2. Arthritis Rheumatol. 2021 Apr;73(4):e13-e29.

- Henderson LA, Canna SW, Friedman KG, Gorelik M, Lapidus SK, Bassiri H, Behrens EM, Kernan KF, Schulert GS, Seo P, Son MBF, Tremoulet AH, VanderPluym C, Yeung RSM, Mudano AS, Turner AS, Karp DR, Mehta JJ. American College of Rheumatology Clinical Guidance for Multisystem Inflammatory Syndrome in Children Associated With SARS-CoV-2 and Hyperinflammation in Pediatric COVID-19: Version 3. Arthritis Rheumatol. 2022 Apr;74(4):e1-e20. [CrossRef]

- McCrindle BW, Rowley AH, Newburger JW, Burns JC, Bolger AF, Gewitz M, Baker AL, Jackson MA, Takahashi M, Shah PB, Kobayashi T, Wu MH, Saji TT, Pahl E; American Heart Association Rheumatic Fever, Endocarditis, and Kawasaki Disease Committee of the Council on Cardiovascular Disease in the Young; Council on Cardiovascular and Stroke Nursing; Council on Cardiovascular Surgery and Anesthesia; and Council on Epidemiology and Prevention. Diagnosis, Treatment, and Long-Term Management of Kawasaki Disease: A Scientific Statement for Health Professionals From the American Heart Association. Circulation. 2017 Apr 25;135(17):e927-e999. [CrossRef]

- Consiglio CR, Cotugno N, Sardh F, Pou C, Amodio D, Rodriguez L, Tan Z, Zicari S, Ruggiero A, Pascucci GR, Santilli V, Campbell T, Bryceson Y, Eriksson D, Wang J, Marchesi A, Lakshmikanth T, Campana A, Villani A, Rossi P; CACTUS Study Team; Landegren N, Palma P, Brodin P. The Immunology of Multisystem Inflammatory Syndrome in Children with COVID-19. Cell. 2020 Nov 12;183(4):968-981.e7. [CrossRef]

- Valverde I, Singh Y, Sanchez-de-Toledo J, Theocharis P, Chikermane A, Di Filippo S, Kuciñska B, Mannarino S, Tamariz-Martel A, Gutierrez-Larraya F, Soda G, Vandekerckhove K, Gonzalez-Barlatay F, McMahon CJ, Marcora S, Napoleone CP, Duong P, Tuo G, Deri A, Nepali G, Ilina M, Ciliberti P, Miller O; AEPC COVID-19 Rapid Response Team*. Acute Cardiovascular Manifestations in 286 Children With Multisystem Inflammatory Syndrome Associated With COVID-19 Infection in Europe. Circulation. 2021 Jan 5;143(1):21-32. [CrossRef]

- Rowley AH. Kawasaki disease: novel insights into etiology and genetic susceptibility. Annu Rev Med. 2011;62:69-77. [CrossRef]

- Matsubara D, Kauffman HL, Wang Y, Calderon-Anyosa R, Nadaraj S, Elias MD, White TJ, Torowicz DL, Yubbu P, Giglia TM, Hogarty AN, Rossano JW, Quartermain MD, Banerjee A. Echocardiographic Findings in Pediatric Multisystem Inflammatory Syndrome Associated With COVID-19 in the United States. J Am Coll Cardiol. 2020 Oct 27;76(17):1947-1961.

- World Health Organization. Multisystem inflammatory syndrome in children and adolescents with COVID-19: Scientific Brief. Available at: https://www.who.int/publications-detail/multisystem-inflammatory-syndrome-in-children-and-adolescents-with-covid-19. Accessed on: May 17, 2020.

- CDC/CSTE Standardized Case Definition for Surveillance of Multisystem Inflammatory Syndrome in Children Associated with SARS-CoV-2 Infection. Available at: https://cdn.ymaws.com/www.cste.org/resource/resmgr/ps/ps2022/22-ID-02_MISC.pdf. Accessed on: January 27, 2023.

- García-Salido A, Antón J, Martínez-Pajares JD, Giralt Garcia G, Gómez Cortés B, Tagarro A; Grupo de trabajo de la Asociación Española de Pediatría para el Síndrome Inflamatorio Multisistémico Pediátrico vinculado a SARS-CoV-2; Miembros del Grupo de trabajo de la Asociación Española de Pediatría para el Síndrome Inflamatorio Multisistémico Pediátrico vinculado a SARS-CoV-2; Belda Hofheinz S, Calvo Penadés I, de Carlos Vicente JC, Grasa Lozano CD, Hernández Bou S, Pino Ramírez RM, Núñez Cuadros E, Pérez-Lescure Picarzo J, Saavedra Lozano J, Salas-Mera D, Villalobos Pinto E. Documento español de consenso sobre diagnóstico, estabilización y tratamiento del síndrome inflamatorio multisistémico pediátrico vinculado a SARS-CoV-2 (SIM-PedS) [Spanish consensus document on diagnosis, stabilisation and treatment of pediatric multisystem inflammatory syndrome related to SARS-CoV-2 (SIM-PedS)]. An Pediatr (Engl Ed). 2021 Feb;94(2):116.e1-116.e11..

- Newburger JW, Takahashi M, Gerber MA, Gewitz MH, Tani LY, Burns JC, Shulman ST, Bolger AF, Ferrieri P, Baltimore RS, Wilson WR, Baddour LM, Levison ME, Pallasch TJ, Falace DA, Taubert KA; Committee on Rheumatic Fever, Endocarditis and Kawasaki Disease; Council on Cardiovascular Disease in the Young; American Heart Association; American Academy of Pediatrics. Diagnosis, treatment, and long-term management of Kawasaki disease: a statement for health professionals from the Committee on Rheumatic Fever, Endocarditis and Kawasaki Disease, Council on Cardiovascular Disease in the Young, American Heart Association. Circulation. 2004 Oct 26;110(17):2747-71.

- Truong DT, Trachtenberg FL, Hu C, Pearson GD, Friedman K, Sabati AA, Dionne A, Oster ME, Anderson BR, Block J, Bradford TT, Campbell MJ, D'Addese L, Dummer KB, Elias MD, Forsha D, Garuba OD, Hasbani K, Hayes K, Hebson C, Jone PN, Krishnan A, Lang S, McCrindle BW, McHugh KE, Mitchell EC, Morrison T, Muniz JC, Payne RM, Portman MA, Russell MW, Sanil Y, Shakti D, Sharma K, Shea JR, Sykes M, Shekerdemian LS, Szmuszkovicz J, Thacker D, Newburger JW; MUSIC Study Investigators. Six-Month Outcomes in the Long-Term Outcomes After the Multisystem Inflammatory Syndrome in Children Study. JAMA Pediatr. 2025 Jan 13. [CrossRef]

- Acevedo, L., Piñeres-Olave, B.E., Niño-Serna, L.F. et al. Mortality and clinical characteristics of multisystem inflammatory syndrome in children (MIS-C) associated with covid-19 in critically ill patients: an observational multicenter study (MISCO study). BMC Pediatr 2021; 21, 516. [CrossRef]

- Kanegaye JT, Wilder MS, Molkara D, Frazer JR, Pancheri J, Tremoulet AH, Watson VE, Best BM, Burns JC. Recognition of Kawasaki disease shock syndrome. Pediatrics. 2009 May;123(5):e783-9. [CrossRef]

- Yousaf AR, Lindsey KN, Wu MJ, et al. Notes from the Field: Surveillance for Multisystem Inflammatory Syndrome in Children — United States, 2023. MMWR Morb Mortal Wkly Rep 2024;73:225–228. http://dx.doi.org/10.15585/mmwr.mm7310a2.

| Feature | Observation |

|---|---|

| Total Patients | 15 |

| Gender Distribution | 8 males, 7 females |

| Median Age | 10 years (Range: 12 months–15 years) |

| Common Symptoms | Fever, abdominal pain, vomiting, diarrea |

| Myocardial Involvement | 46,6% (7/15 patients) |

| Biomarkers | Elevated CRP, IL-6, NT-proBNP, Troponin |

| Treatments | IVIG, corticosteroids, aspirin, anticoagulation |

| Outcomes | Full recovery; no coronary aneurysms |

| Biomarker | Patients with myocardial dysfunction | Patients without myocardial dysfunction | Significance |

|---|---|---|---|

| PCR (mg/dl) | 15.9 (6.2 – 21.4) | 14.7 (5.1 – 29.2) | p > 0.05 |

| ESR (mm/h) | 66.1 (15 – 120) | 68.6 (17 – 101) | p > 0.05 |

| Ferritin (mg/dl) | 355 (59 – 733) | 160 (79 – 362) | *p = 0.038 |

| NT-ProBNP (pg/ml) | 7223 (671 – 14800) | 1906 (618 – 4213) | *p = 0.001 |

| Troponin (ng/ml) | 1504 (101 – 6222) | 12 (2 – 64) | *p < 0.001 |

| D-dimer (ng/ml) | 3240 (1400 - 6017) | 3855 (1708 – 12827) | p > 0.05 |

| Feature | Current Study | MUSIC Study (JAMA 2025) |

|---|---|---|

| Total Patients | 15 | 1204 |

| Coronary Artery Involvement | None | 15 cases (1 giant aneurysm) |

| Myocardial Dysfunction | 46.6% transient dysfunction | 42% transient dysfunction |

| Recovery of LV Function | 100% | 99% |

| Treatments | IVIG, corticosteroids, aspirin, heparin | IVIG, corticosteroids |

| Mortality | None | 0.3% |

| Biomarkers | Elevated CRP, IL-6, NT-proBNP, Troponin | Elevated CRP, IL-6, NT-proBNP, Troponin |

Disclaimer/Publisher’s Note: The statements, opinions and data contained in all publications are solely those of the individual author(s) and contributor(s) and not of MDPI and/or the editor(s). MDPI and/or the editor(s) disclaim responsibility for any injury to people or property resulting from any ideas, methods, instructions or products referred to in the content. |

© 2025 by the authors. Licensee MDPI, Basel, Switzerland. This article is an open access article distributed under the terms and conditions of the Creative Commons Attribution (CC BY) license (http://creativecommons.org/licenses/by/4.0/).