1. Introduction

1.1. Research Background

Berries, especially blueberries, are very popular because they are considered a superfood due to their disease-preventing role. These substances stimulate blood supply to capillary vessels throughout the body and aid in the rapid regeneration of retinal cells in the eye. Consuming blueberries is particularly beneficial for individuals who spend extended periods in front of screens.

Blueberries are highly valued for their high antioxidant content. However, they are also particularly susceptible to fungal deterioration. Therefore, the appropriate and optimal design of blueberry packaging is crucial from both a health and consumer perspective and an environmental viewpoint.

Global blueberry production has doubled since 2012, reaching 1.86 million metric tons from 248,550 hectares. Of this, 529,210 metric tons are processed, while over 1.3 million metric tons are available for fresh consumption [

1]. In Estonia, the demand for blueberries is met primarily through imports. In the year 2022, Estonia imported 4.45 million kilograms, an increase from 2.63 million kilograms [

2]. This growth underscores the rising demand for fresh berries, necessitating 400 to 800 tons of packaging annually to deliver to consumers.

Blueberries are typically packaged in small packages (125 and 250 grams, placed in a multi-pack) to protect the small fruits. However, this type of packaging generates a significant amount of material, and both its production and post-consumer treatment can cause serious environmental problems. Most of the packaging materials are plastic, contributing to pollution in landfills and oceans and exacerbating the issue of global warming [

2].

Nowadays, efforts are also being made to achieve sustainability in the case of blueberries by selecting appropriate packaging materials. At the same time, consumer demands have evolved following the trend towards healthier lifestyles, which has also made sustainable consumption a more significant issue within the context of various food packaging. The ideal packaging should ensure the safe delivery of this popular fruit to consumers while maintaining the product's quality.

Optimal food packaging also maintains food safety and prevents food waste and loss [

3]. However, it should also consider environmental factors and promote circularity. Plastic is a widely used material for food packaging because it is fluid, mouldable, heat sealable, easy to print, and can be integrated into production processes [

4].

The European Union (EU) aims to reduce plastic waste by introducing various types of single-use plastic packaging, including those used for packaging fresh fruit and vegetables [

5]. The European Single-Use Plastics (SUP) Directive was approved as part of the European Strategy for Plastics in a Circular Economy. This directive aims to reduce the environmental impact of specific plastic products [

6].

The European Commission initiated this directive to promote a more circular plastics sector and to address the pollution caused by certain plastic products. Fresh berries are primarily packed in SUP punnets. Most food packages are designed for single use and discarded the same year they are produced [

7].

Naturally, questions arise about how different packaging materials and SUP punnets influence the quality of fruits and travel safety. Another question is what sustainable alternatives exist for packaging berries concerning the stated goals of reducing carbon emissions.

With the increasing demand for sustainability, environmentally friendly solutions are crucial in blueberry packaging. Biodegradable and recyclable materials, such as compostable plastics and paper-based packaging, are becoming more common in the market. Additionally, applying the principles of a circular economy—focused on reusing materials to minimize waste and reduce environmental impact—is essential [

8].

It can contribute to a more sustainable blueberry supply chain by considering the full life cycle of packaging, improving energy efficiency in transport and storage, and using recycled materials. Understanding the environmental impacts of various product packaging through life cycle assessment is now essential for achieving sustainable packaging and decarbonization goals. Sustainable packaging represents one of the most promising pathways to transition to a circular and climate-neutral economy.

1.2. Literature Review

Blueberries, as a superfood, have received significant attention in consumer markets over the past two decades [

9] due to their antioxidant content and other beneficial effects [

10,

11]. However, with increasing demand, it is important to consider the environmental impacts of production and transport chains (both short and long) [

12,

13,

14,

15]especially in terms of packaging solutions aimed at preserving the quality of blueberries [

16,

17,

18,

19].

Since blueberries are a berry with high moisture content, packaging must ensure freshness while protecting against damage and oxygen exposure. In addition, blueberries are sensitive to temperature changes. Therefore, to create optimal transport and storage conditions, each packaging must adequately protect the product while considering the appropriate packaging material.

Examining the blueberry supply chain from a sustainability perspective yielded interesting results. The European berry market represents a good example of a consumer-driven supply chain due to its ability to respond to all aspects of the system. The growing market trend for fresh products is driven by consumers oriented towards new lifestyles and environmental issues.

Peano and their colleagues [

20,

21]studied the Italian blueberry supply chain from a sustainability perspective, dividing their research into four stages. The first stage reviews the organization of the fresh fruit supply chain (FFSC) and the need for innovation due to rising demand. The second stage examines advancements in storing and maintaining fruit quality during transportation. The third stage features a case study, while the conclusion summarizes key findings and their implications for future research. A modified active packaging system (MAP) using "green" films has successfully preserved blueberry quality for up to two months, extended market presence, improved exports to new European countries, and increased turnover for the associated group, ultimately benefiting fruit growers.

Several studies have investigated blueberry packaging. Bof, M. J. et al. [

22,

22]utilized corn starch and chitosan, byproducts of the fishing industry, and active compounds from citrus waste to create biodegradable films. Blueberries were packed in corn starch-chitosan (CS: CH) films and active films containing lemon essential oil (LEO) or grapefruit seed extract (GSE). The research assessed how these packaging materials affected berry quality and fungal incidence during storage [

22]. The results indicated that blueberries in CS: CH films retained 84.8% of their initial antioxidant content, similar to those in commercial PET containers (clamshells). In contrast, LEO films resulted in higher weight loss and rot.

A previous study by

Koort et al. [

23]aimed to determine the impacts of modified atmosphere packaging on the external quality and nutritional value of organically grown bush blueberries (“Northblue”). The storage of the fruits was investigated in typical atmosphere (RA) boxes without packaging, boxes sealed in low-density polyethylene (LDPE, Estiko) bags, and boxes sealed in Xtend® blueberry bags (Stepac) at 3 ± 1 °C. The study found higher dry matter content and titratable fruit acidity in Xtend® packaging. However, Xtend® packaging extended the post-harvest shelf life by 15 days for low-bush blueberries and 9 days for medium-bush blueberries.

Giuggioli et al. [

24]found that using eco-friendly packaging can influence consumer choices for fresh fruits. This study evaluated green wrapping films for passive modified atmosphere packaging in storing strawberries (cv. Portola) for 7 days at 1 ± 1°C, followed by 2 days at 20 ± 1°C. One commercial polypropylene macro-perforated film (control) and three non-commercial biodegradable films (prototypes from Novamont) were tested. Film 1 achieved optimal gas composition, maintaining levels of 17.60–18.50% O₂ and 5.30–5.60% CO₂ for up to 5 days. It also received the highest sensory scores for condensation, taste, marketability, and the redness of the fruit at 20 ± 1°C.

Singh, Gu et al. [

25]investigated the edible packaging characteristics of blueberry packaging. Their research focused on creating edible packaging films from various starches: potato, corn, sweet potato, green bean, and tapioca. These films included blueberry pomace powder (BPP). Tests checked the films' properties, such as strength and how they react to heat. Adding BPP did not change the color of the films, but it improved how well corn and green bean starch films blocked UV light, which helps protect food. The thickness and transparency of the films mainly stayed the same with different starches or amounts of BPP, though corn starch films were the clearest. All films held their shape and were strong, with higher water vapor transmission rates than standard polyethene films. The solubility of the films ranged from 24% to 37%, showing that they are suitable for packaging foods with low to moderate moisture. There were no differences in thermic properties based on the type of starch or BPP levels. Tests showed that more active compounds from BPP were released into acetic acid (a food-like liquid) than ethanol (a fatty liquid). Adding BPP to starch-chitosan films improved their quality, indicating that BPP could be a valuable addition to active food packaging solutions [

25].

Research on alternative packaging to replace plastic has mainly focused on preserving product quality without considering the environmental impact or energy requirements throughout its life cycle.

Mari et al. [

26]studied using edible coatings and osmotic dehydration to preserve berries such as blueberries, raspberries, and strawberries. Their life cycle assessment (LCA) revealed that osmotic dehydration, particularly when using apple concentrate, has a significant environmental impact. In contrast, edible coatings have a minimal environmental footprint since they are made from low-energy and biodegradable materials.

1.3. Research Goal and Hypothesis

This work calculated the environmental impacts using a comparative cradle-to-grave life cycle assessment of four packaging materials. These materials include recycled paper and other packaging options, such as cardboard packages (CB), cardboard packages with a cellulose lid (CBC), polypropylene (PP), and a box made from rice straw topped with a lid made from polylactic acid (RPLA), a bio-based plastic.

In the present study, we conducted a literature review regarding the research topic and modelling for various blueberry packaging options. Based on the results using a life cycle approach, we aimed to identify reasonable and optimal solutions for reducing environmental impacts. Our initial hypothesis is that recycled paper packaging significantly decreases the environmental impact categories at the end-of-life stage, while plastic packaging increases global emissions.

The main goal of the research was to prepare complete life cycle assessment models by comparing different blueberry packaging options, primarily focusing on the carbon footprint and other impact values. The study was based on packaging types from Poland. In previous researches [

27,

28,

29] we had already created separate cradle-to-grave life cycle assessments and end-of-life scenarios; however, blueberry packaging options were investigated for the first time.

2. Materials and Methods

2.1. Research Methodology

During the life cycle assessment methodology, we adhered to the required steps: determining the system boundary, functional unit, and allocation; defining expectations regarding batch quality; collecting data and conducting inventory analysis based on measured packaging mass data; and performing impact assessment and interpretation.

In the first step of the research, we estimated the environmental impacts of blueberry packaging materials related to production and use lifecycle stages. Four packaging materials were chosen for blueberry storage:

packaging 1: cardboard package (CB),

packaging 2: cardboard package with a cellulose lid (CBC),

packaging 3: polypropylene (PP),

packaging 4: rice straw package covered with a lid made from polylactic acid (RPLA) as a bio-based plastic.

The applied Sphera GaBi software (version 10.6) [

30] encompasses the lifecycle stages, including also transport processes. The functional unit was one piece of packaging material. The environmental life cycle impact assessments (LCIAs) considered all environmental impact categories and were utilized along with the CML 2016 method [

31,

32].

In the second step, special attention was given to various end-of-life scenarios. The first is recycling, the second is composting, the third is landfill disposal of the packaging, and the final option is traditional incineration. A looping method was applied in the recycling scenario. It means that the waste stream from the recycling was recirculated to the production stage as a secondary raw material on site. The looping method helped to create the cradle-to-cradle LCAs by linking production, use, and recycling stages in the software's LCA plan.

In the third step, we separately compared the global warming potential values of the tested materials in connection with different end-of-life solutions. After that, abiotic fossil depletions and energy resources for cradle-to-cradle assessments of packaging materials were calculated.

Finally, we determined the packaging's carbon footprint and energy requirement for 1000 kg of blueberries.

2.2. Life Cycle Assessment Method

The life cycle inventory is based on 2023 data and follows the technique described in the ISO 14040:2006 and 14044:2006 standards [

33,

34]. It includes the material and energy supply of all the examined processes.

Table 1 and

Figure 1 present the tested packaging materials.

The blueberry packaging was analyzed within a cradle-to-grave and cradle-to-cradle system boundaries based on the weight of the packaging materials. All environmental impacts were allocated proportionally by mass to the products being tested and the waste generated. The material and energy flows correspond to the output of the examined products. The energy requirements were assessed based on the energy content. Equipment and machinery were excluded from the system boundary.

During the life cycle impact assessment, CML 2001/2016 August method was used to determine the impact categories in the software.

2.3. Examination Methods for Transport Processes

When determining the impact categories, we considered the environmental impact of transport. We calculated the environmental impacts and emissions for transportation depending on the different delivery modes, transport distances and utilization grades of payload.

The following deliveries were taken into account during the analysis:

transportation of raw materials (kraft paper, wood, polypropylene granulate, and PLA) to the production stage (by truck, Euro 6, with a gross weight of 26-28 tons),

transport between the production and use stages (truck trailer, Euro 6, with a gross weight of 34-40 tons),

transport between the use and end-of-life stages (truck trailer, Euro 6, with a gross weight of 34-40 tons).

Transportation between the EoL and production stages for recycled materials was not modelled, assuming the production process occurs where the waste is generated.

3. Results

This study assesses the environmental impacts of four packaging materials through a comparative cradle-to-grave life cycle analysis. The materials examined include recycled paper, cardboard package (CB), a cardboard package with a cellulose lid (CBC), polypropylene (PP), and a box made from rice straw topped with a lid made from polylactic acid (RPLA), which is a bio-based plastic.

The main goal of the study was to calculate environmental impacts, primarily focusing on the global warming potential, abiotic depletion for fossils and energy resources for the cradle-to-grave assessments.

The following end-of-life scenarios were taken into account during the analysis:

Scenario 1 (SC1): recycling (R),

Scenario 2 (SC2): composting ©

Scenario 3 (SC3): landfilling (D),

Scenario 4 (SC4): incineration (I).

In the case of the recycling scenario, the life cycle analysis of the tested packaging materials were prepared for each component by assuming that the waste stream processed by recycling at the EoL stage and goes as a secondary raw material into the production stage. Therefore, regarding recycling scenario, a cradle-to-cradle life cycle assessment was examined.

3.1. Environmental Impacts for Recycling (SC1)

In the case of the recycling scenario, a looping method was applied during the analysis between the EoL and the production stages.. Since CB, CBC and PP materials are produced in Poland, a Polish electricity grid mix has been introduced in the production stage of all packaging materials. Only RPLA is produced in Germany. All other input currents (kraft paper, tap water from surface, offset ink, corn starch, and cellulose) and all waste management processes were simulated under EU-27 conditions.

By creating of cradle-to-cradle LCA plan for CB and CBC packaging materials, the recycled paper as input flow of production stage comes from the EoL/recycling stage as recovered paper (materials from renewable materials). The non-recyclable waste paper stream was incinerated conventionally under EU conditions.

By creating of cradle-to-cradle LCA plan for PP and RPLA packaging materials, the secondary polymers as recovered plastic parts go to the production process from the EoL phase. The non-recyclable plastic parts were incinerated in a waste incineration plant.

Wastewater streams go to municipal wastewater treatment. Road transport, using Euro 6 trucks with diesel mix and a distance of 100 km, was considered for the transportation of kraft paper and lightweight wood raw materials. In connection of looped life cycle, the normalized and weighted environmental impacts for the production stage of each packaging materials are summarized in the

Table 2.

In the case of cradle-to-cradle analysis,

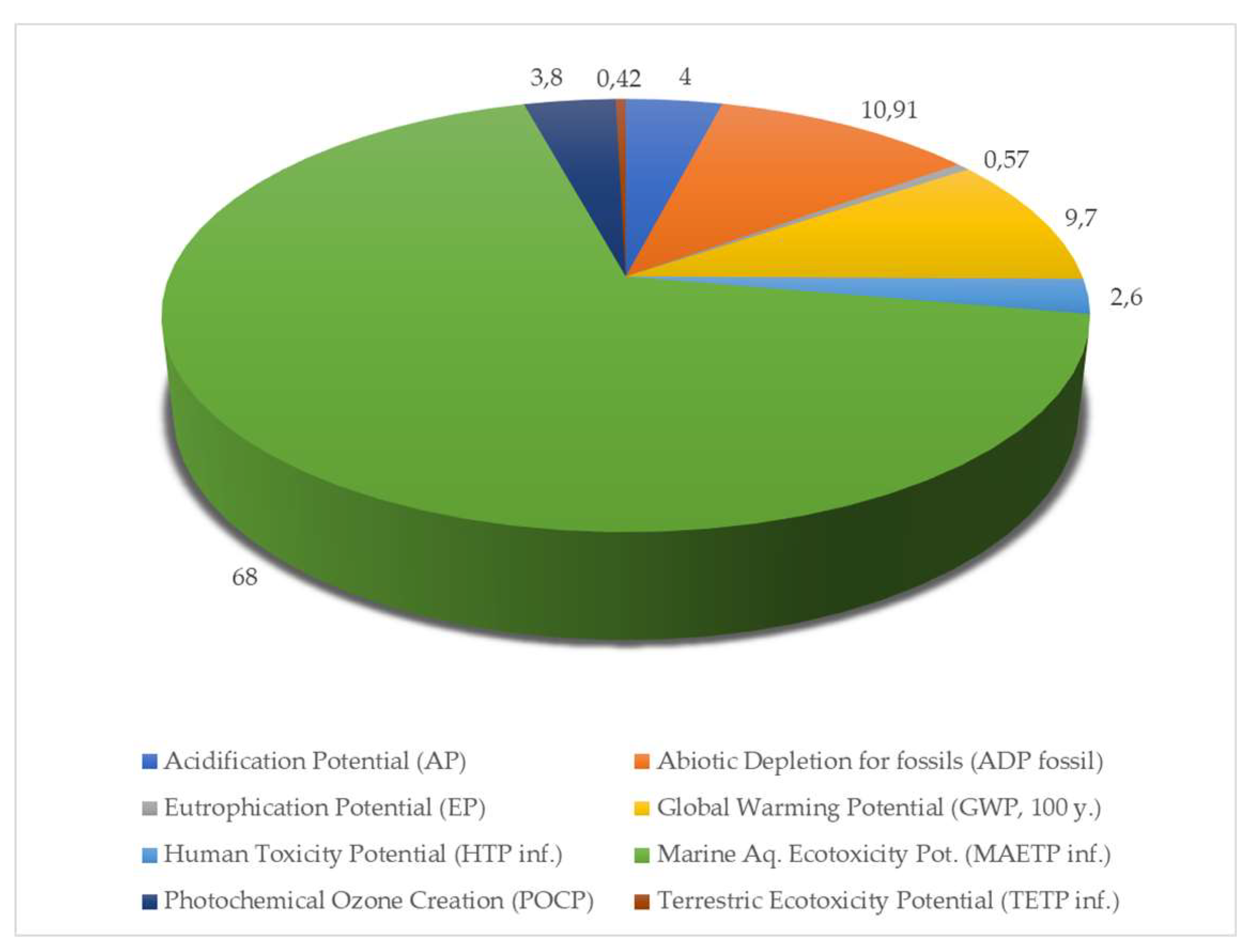

Figure 2 presents the percentage distribution of main impact categories regarding CB packaging (P1) applying normalization and weighting methods. Here, the values of abiotic depletion for elements (ADPE), ozone layer depletion ODP, steady state), and freshwater aquatic ecotoxicity (FAETP) are so low that they are negligible in the analysis. Therefore, eight impacts were depicted in the pie charts instead of 11 impact categories.

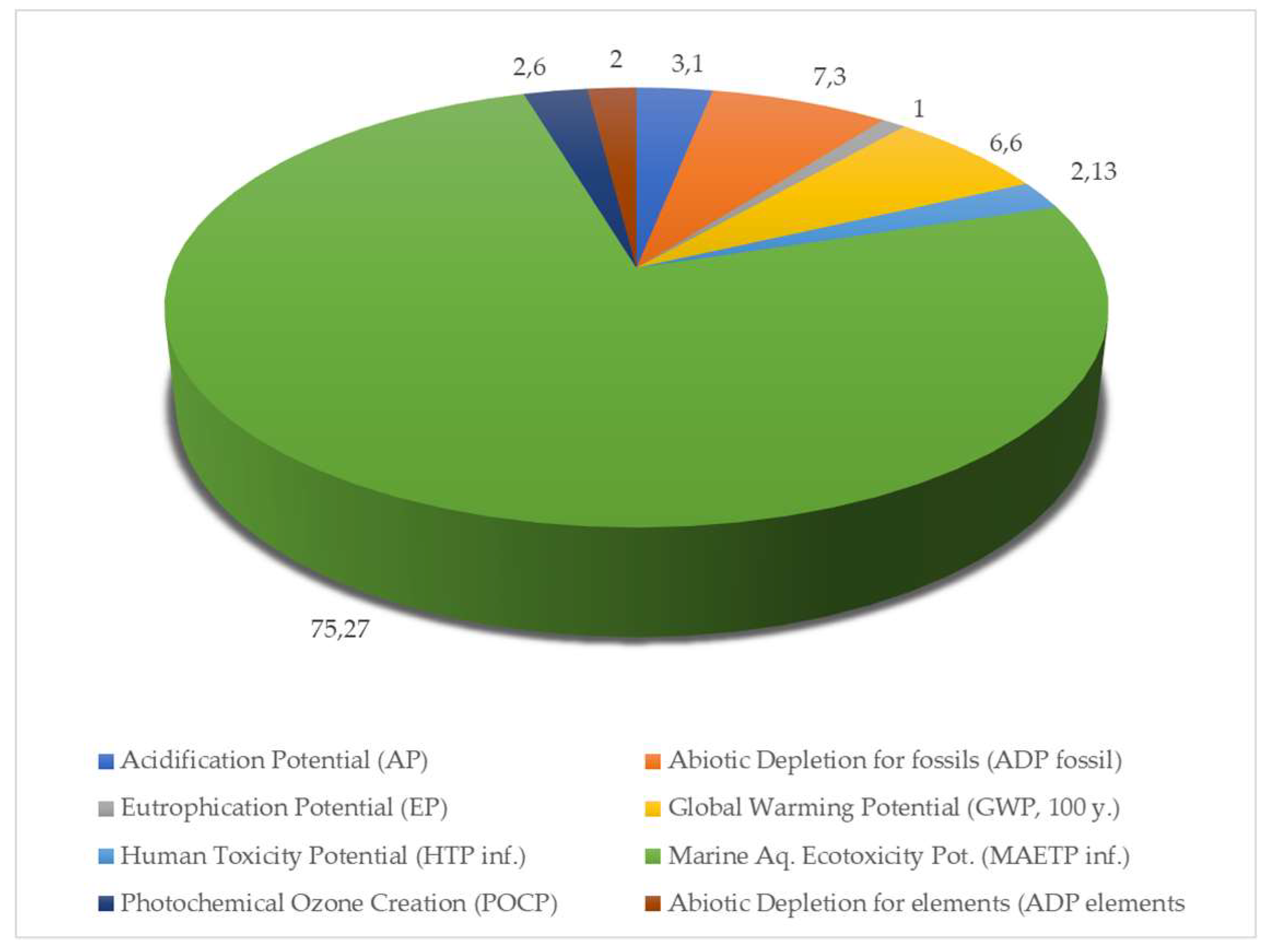

Figure 3 shows the percentage distribution of impact categories regarding CBC packaging (P2) after normalization and weighting. The ozone layer depletion potential, freshwater ecotoxicity, and terrestrial ecotoxicity potential (TETP) are quite low; therefore, we consider them negligible in

Figure 3, and only eight effects are displayed here.

Figure 2 clearly shows that marine ecotoxicity accounts for 68% of the environmental impact of CB packaging, followed by fossil resource demand at 10.91% and then global warming at 9.7%. The remaining 10% is divided between the other impact categories. Based on

Figure 3, marine ecotoxicity represents an even larger share of the total when CBC packaging is used than when CB packaging is used. The ADP fossil and GWP values also show a decreasing trend. The combined impact of the other impact categories examined is around 10%.

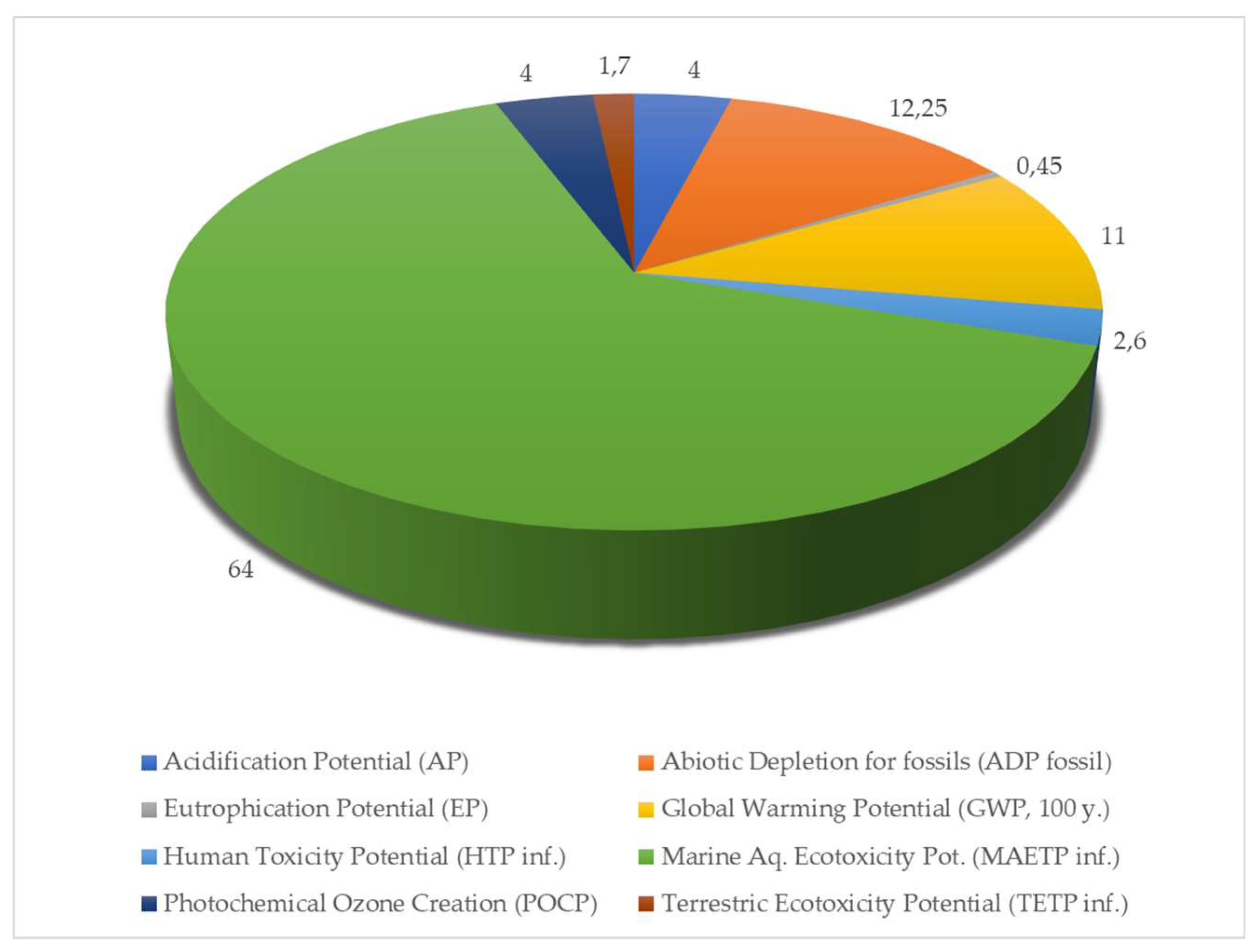

Figure 4 presents the percentage distribution of impact categories regarding PP packaging (P3). The ozone layer depletion, freshwater aquatic ecotoxicity, and abiotic depletion (elements) are negligible.

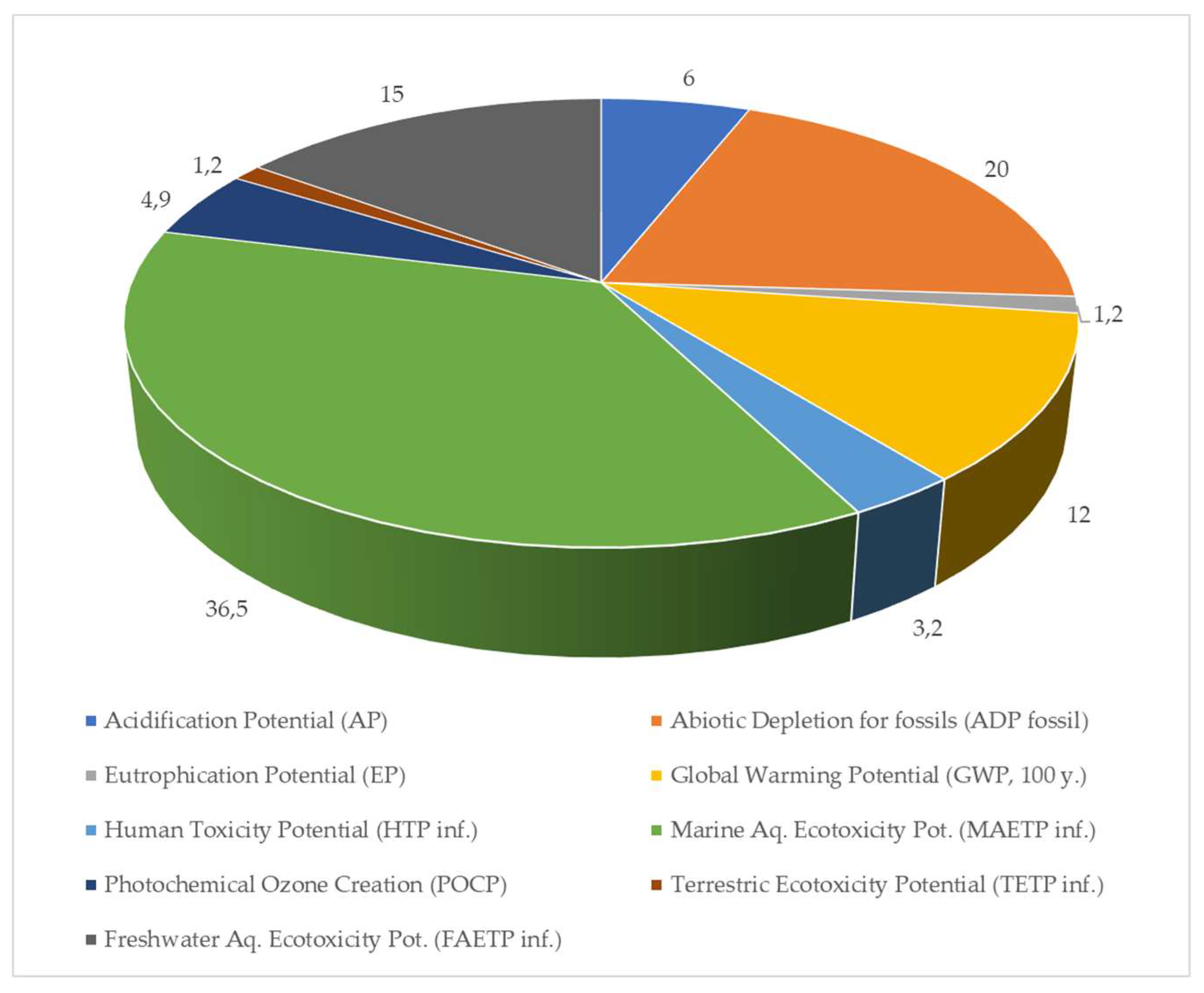

Figure 5 presents the percentage distribution of impact categories regarding RPLA packaging (P4). In this case, ozone layer depletion and abiotic depletion for elements are negligible. Therefore, nine impact categories have been exceptionally depicted here.

Figure 4 summarizes that although the marine ecotoxicity potential of PP packaging is only 64%, the abiotic depletion for fossils and global warming potential are also higher.

Regarding the impacts of RPLA packaging shown in

Figure 5, marine ecotoxicity has decreased. However, the environmental impact on the aquatic ecosystem has increased, with ecotoxicity accounting for 51.5%, ADPF representing 20%, and GWP representing 12%. The percentage composition of the other impact categories examined has also increased to 16.5%.

Figure 6 summarizes the percentage distribution of impact categories.

The combined results in

Table 2 and

Figure 6 clearly show that in the case of recycling, the global warming potential and marine ecotoxicity dominate for CBC. Comparison of environmental impacts: CBC > RPLA > PP > CB.

3.2. Environmental Impacts for Composting (SC2)

Regarding composting scenario in the framework of cradle-to-grave analysis,

Table 3 presents the calculated environmental impacts for the four packaging systems, using the CML 2016 life cycle impact assessment method.

Figure 7 summarizes the percentage distribution of impact categories.

Based on the environmental impact assessment of composting, ADP fossil represents the highest load in the case of CBC, while the lowest rate was observed in the case of RPLA. Regarding global warming, PP showed the second most substantial impact; its lowest rate was in the case of CBC. It can also be observed that the rate of fresh aquatic ecotoxicity (FAETP) increased in the case of RPLA.

Evaluating the environmental impact of composting reveals a clear hierarchy: CBC_C demonstrates the most significant impact, followed by CB_C, PP_C, and RPLA_C. This comparison underscores the superiority of CBC_C in minimizing environmental strain and highlights the importance of selecting the most effective composting methods for a sustainable future.

3.3. Environmental Impacts for Landfilling (SC3)

Regarding landfilling,

Table 4 presents the calculated environmental impacts for the four packaging systems, using the CML 2016 life cycle impact assessment method. The functional unit was 1000 kg of packaging.

Figure 8 summarizes the percentage distribution of impact categories.The distribution of the environmental impact ratio for packaging landfilling was as follows: ADP fossil was the largest in all four cases, followed by GWP in the cases of PP and RPLA.

3.4. Environmental Impacts for Incineration (SC4)

Regarding conventional incineration,

Table 5 presents the calculated environmental impacts for the four packaging systems, using the CML 2016 life cycle impact assessment method.

Figure 9 summarizes the percentage distribution of impact categories.

The distribution of environmental impacts caused by conventional incineration shows that marine ecotoxicity still represents the most significant burden, followed by the impact of fossil fuels and global warming. However, in the case of RPLA, freshwater ecotoxicity is 10%.

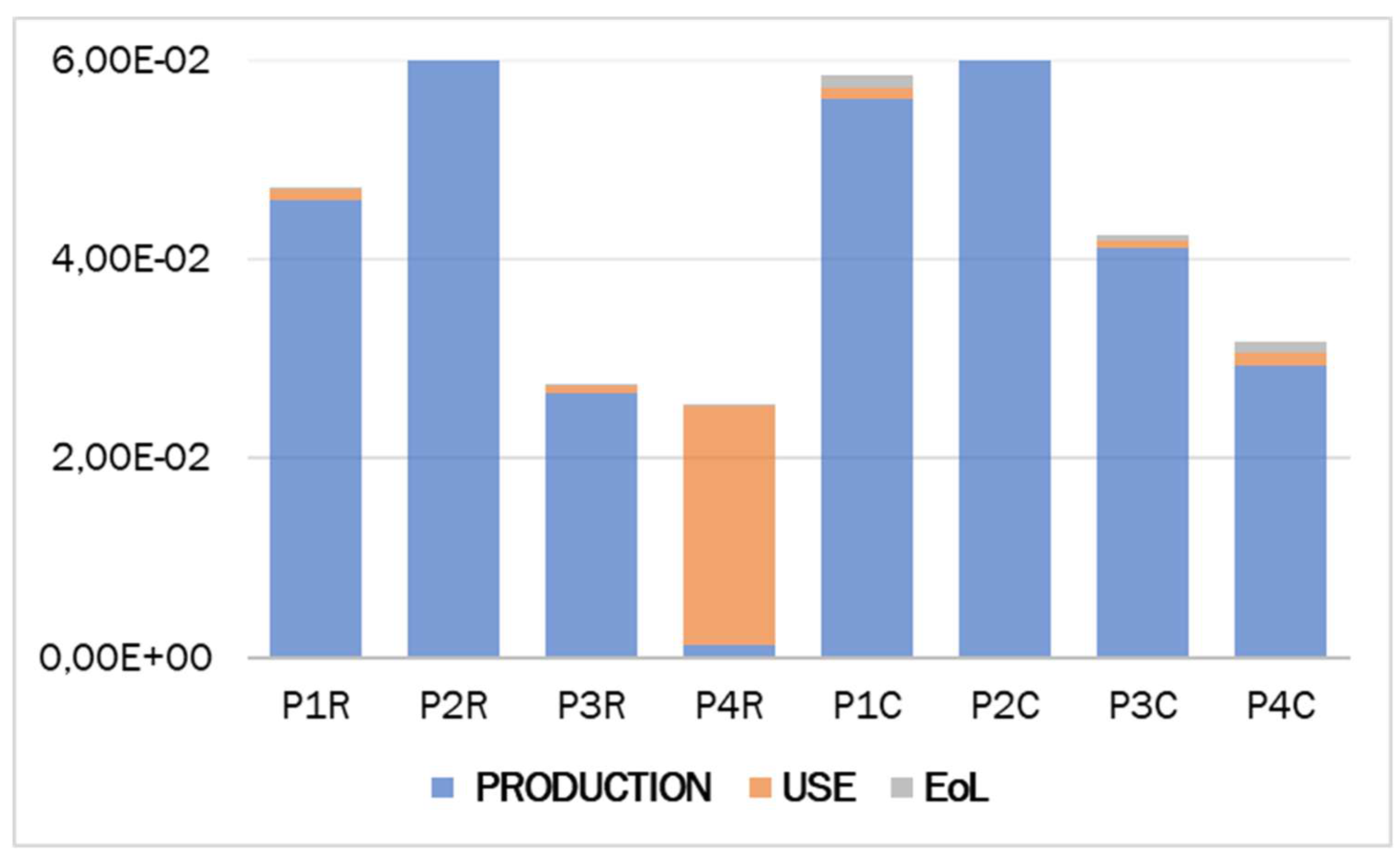

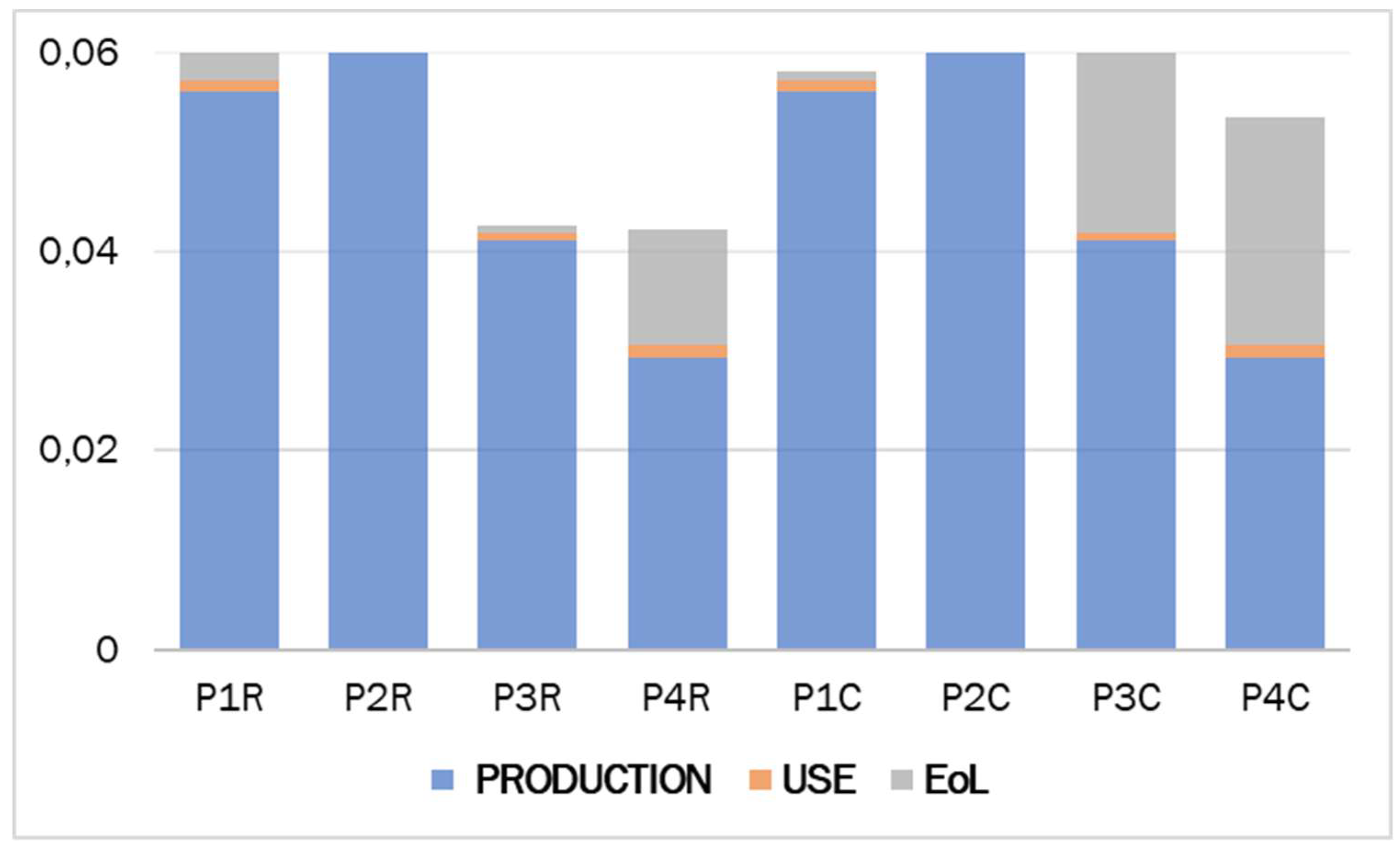

3.5. Global Warming Potential of the Lifecycle Stages

An important aspect is that we separately identify the value of the global warming potential (GWP) regarding the lifecycle stages of the four tested packaging materials.

Figure 10 compares the global warming potential of recycling and composting, and

Figure 11 shows the values of disposal and conventional incineration in kg CO

2 eq.

Additionally, we calculated the carbon footprint for the quantity of packing materials per 1000 kg of blueberries in

Table 6 for each waste treatment process scenario. During the calculations, the unit of each type of packaging was 0.250 kg.

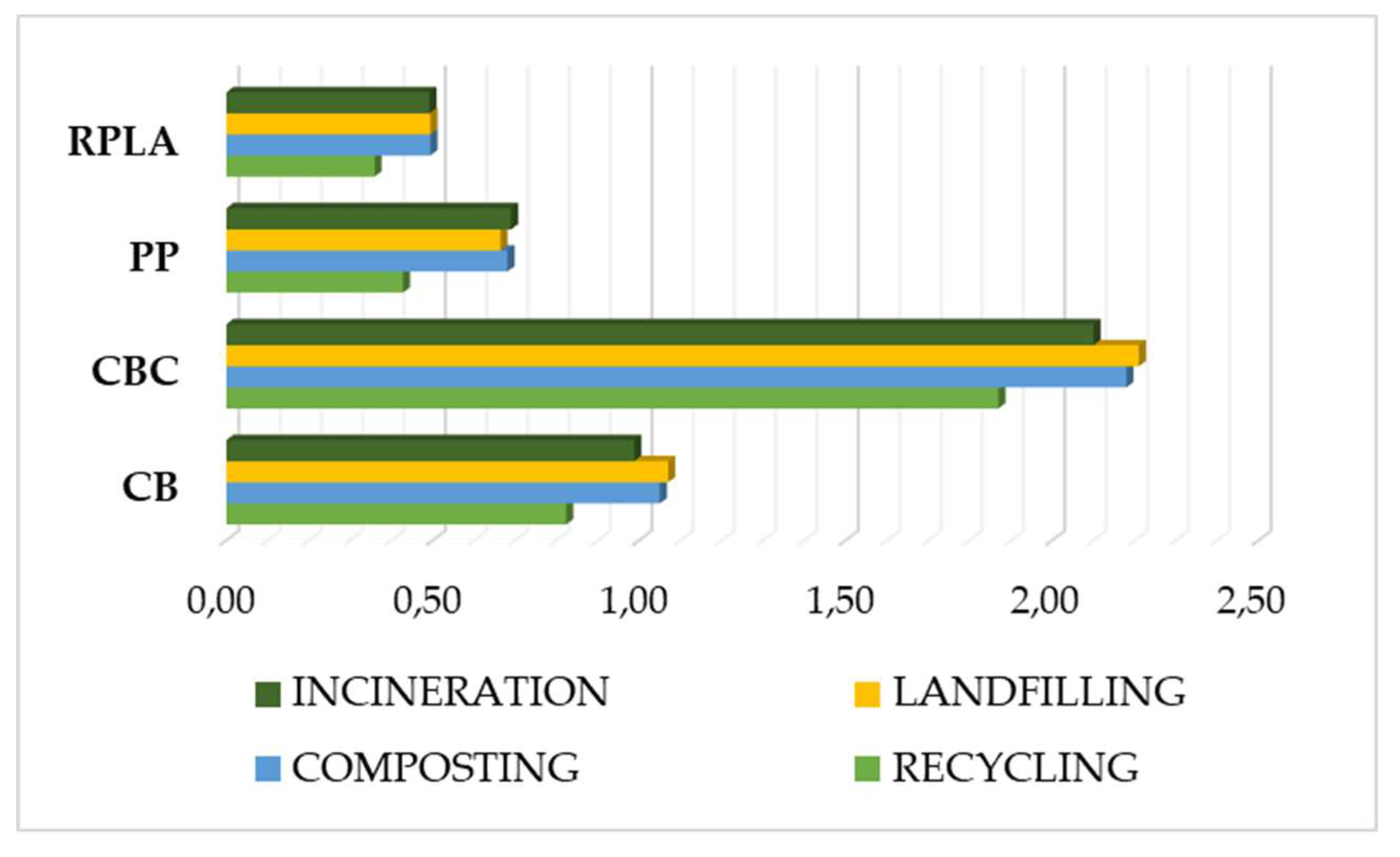

Based on the results of table 6, it can be said that when examining the individual waste treatment scenarios, the RPLA packaging material has the lowest carbon footprint for every end-of-life solution. In the case of recycling, the RPLA material is followed by PP, CB, and CBC packaging in terms of increasing the carbon footprint. The carbon footprint of CBC is outstanding, at 246 kg CO2 eq. for 1000 kg of packaged blueberries. In the case of composting, the carbon footprint of CB is the highest, followed in descending order by PP, CBC and RPLA. Regarding landfilling and incineration, the CF value for CBC packaging is also the highest (257 and 283 kg CO2 eq.). Thus, overall, it can be said that when examining the waste management processes together, only in the case of composting does CBC not have the highest carbon footprint.

3.6. Total Environmental Impacts of Packaging Materials

The next aspect of the study was to compare the total environmental impact of each packaging material over its whole life cycle, considering the waste treatment processes of the packaging material at the EoL phase. Regarding whole life cycle analysis in the framework of EoL scenarios,

Figure 12 presents the normalized and weighted total environmental impacts for the four packaging systems, using the CML 2016 impact assessment method.

3.7. Embodied Energy of Packaging Materials

A key factor in assessing the environmental performance of packaging materials is the amount of embodied energy, which represents the energy used throughout their life cycle. The embodied energy of packaging materials refers to the total energy used during the production process, including raw material extraction, manufacturing technologies, transportation, and recycling processes [

35,

36].

When analyzing the environmental footprint of packaging solutions used to preserve the freshness of blueberries, it is of particular importance to compare the energy requirements of different materials.

In the last step of the research work, energy resources and abiotic fossil depletion (ADPF) were calculated.

Table 7 and

Table 8 show the absolute values for energy resources and fossil abiotic depletion of packaging materials regarding the whole life cycle in the recycling end-of-life scenario.

Table 9 shows the percentage of abiotic fossil depletion for the production stage of the tested packaging materials, assuming that the sum of the 11 examined environmental impacts is 100%. These percentages were determined after normalizing and weighting the impact categories.

In the case of cardboard boxes (Packagings 1,2 from CB and CBC materials), the embodied energy depends significantly on the fiber source and the recycling rate. According to experiments conducted by the Brno University of Technology, the thermal conductivity of cardboard boxes with different structures varies between 0.05 and 0.12 W/m·K, which is competitive with traditional thermal insulation materials [

37]. The advantage of cellulose-based materials lies in their biodegradability, but their moisture sensitivity may limit their applicability in humid environmental conditions. The low density of polypropylene (in the case of Packaging 3) (0.9–1 g/cm³) allows for the construction of lightweight structures, which results in savings in transport energy. However, the thermal conductivity of polypropylene (in the case of Packaging 3) is 0.1–0.22 W/m·K , which limits its thermal insulation applications[

38].

4. Discussion and Conclusions

During our research, we analyzed the environmental impact of four packaging materials after a detailed literature review, with a special focus on end-of-life solutions. We aimed to identify more optimal solutions for reducing environmental impacts regarding packaging materials. Therefore, we created our cradle-to-cradle and cradle-to-grave life cycle assessments and examined the materials used to package 1,000 kg of blueberries and their environmental impact.

Rai et al. [

39]argue that life cycle assessment can play a key role in understanding the environmental impacts of fruit products throughout their lifecycle, including production, processing, distribution, consumption, and waste management. According to Galarreta [

40]., information obtained from LCA integrated with smart sensors can help develop regulations to optimize supply chain processes, reduce waste, strengthen food safety, and mitigate environmental impacts.

The initial research hypothesis was that recycled paper packaging significantly decreases the environmental impact categories at the end-of-life stage, while plastic packaging increases global emissions. Comparing the obtained results with previous research results is difficult because the functional units of the packaging are different, and various types of packaging are compared.

Our first examined packing materials were cardboard boxes: CB and CBC. The advantage of cardboard boxes is their good air permeability, which helps to preserve the freshness of blueberries and prevent mould. They can be easily printed and branded. Their carbon footprint ranges from 0.8-1.5 kg CO2/kg, depending on the technology. Due to their high mass, their GWP value per 1000 kg of blueberries is exceptionally high, which is caused by the energy required for their production. This energy is mainly generated during wood processing and pulp production (15-25 MJ/kg cardboard).

Oliver-Villanueva et al. [

41]investigated the environmental impact of berry packaging in cardboard packaging materials, focusing on transportation. Their research found that wooden boxes had a lower overall environmental impact than corrugated cardboard packaging, especially in the key impact criteria of global warming, fossil resource depletion, and water consumption. The authors found that corrugated cardboard boxes had a higher impact in all categories of human toxicity and elemental resource depletion.

Regarding human toxicity potential and elemental abiotic depletion, we obtained nearly similar, but one decimal place lower, values for the whole life cycle of the products (assessed in a recycling scenario) for RPLA and PP packaging materials than for corrugated cardboard packaging. Our results confirm Oliver-Villanueva et al.'s [

41]conclusions. However, we cannot verify their findings [

41]regarding global warming and fossil depletion, as we obtained higher values for CB and CBC packaging materials than for PP and RLPA materials (the latter has a surprisingly low value for packaging). We did not examine water use in the research, so we cannot draw any conclusions about this.

Rice starch-polylactic acid (RPLA) combination packaging is a biodegradable polymer that can be composted in industrial facilities and is derived from a renewable source. It represents a promising alternative. The production of PLA has a carbon footprint of 0.5–1.5 kg CO2 eq./kg, as the starch source plants sequester CO2. Its energy requirements are higher than those of cellulose-based packaging (40 MJ/kg) but generally lower than those of PP (based on the Sphera database). The energy requirements depend on the cultivation and manufacturing processes.

Research on the life cycle assessment of polylactic acid highlights that, according to Rezvani Ghomi et al. [

42], its environmental impact is lower than that of other packaging materials. This is because PLA, as a bioplastic and biodegradable material, has lower greenhouse gas emissions. The conclusion of the study of Rezvani Ghomi et al. [

42] is consistent with our results, as we also received the lowest environmental impact for packaging containing PLA.

Rezvani Ghomi et al. [

42]investigated the GHG emissions of PLA at all stages of its life cycle, including raw material procurement and conversion, PLA product manufacturing, PLA applications and end-of-life (EOL) options. Three different end-of-life technologies, composting, incineration, and PLA chemical conversion, were investigated. The most energy-intensive stage of the PLA life cycle is chemical conversion, according to Madival et al. [

43][PLA is 100% recyclable or compostable and has much lower carbon dioxide emissions. The functional unit was chosen as 1000 containers of capacity 0.4536 kg. One thousand PLA containers emit 735 kg CO

2, while a PET container emits 763 kg CO

2.

Although we did not examine chemical transformation, we supplemented our investigation by examining landfill and recycling scenarios. In our case, the global warming potential of 4000 PLA packages with a capacity of 0.250 kg in different end-of-life scenarios varied between 48 and 127 kg CO2 eq, while that of PP packages ranged from 110 to 269 kg CO2 eq. The difference can be attributed to system boundaries, transportation and applied technological data.

Peelman et al. [

44]emphasized the role of bioplastics in packaging. Their study reviewed the development trends and main properties of bioplastic packaging. Almenar et al. [

45,

46]stated that PLA containers are suitable for commercial post-harvest packaging of blueberries. In contrast to conventional PET containers, an equilibrium-modified atmosphere can be created in PLA containers, which increases the shelf life of blueberries. Sensory tests showed that consumers preferred blueberries packaged in PLA containers to those packaged in conventional containers for one to two weeks.

Although we did not perform sensory tests, we did draw the following conclusions regarding the storage and transportation of blueberries:

blueberries stored in CB and CBC packaging had higher soluble solids than the control,

instrumentally measured color intensity was higher in RPLA compared to other packages,

the CB packaging's openings are too wide for blueberries, making them unsafe for transportation and leading to higher weight loss during transportation,

the cellulose lid of the CBC packaging had some deformations after storage.Cellophane has an even higher energy requirement and is not recyclable. Energy requirements can be reduced by using renewable energy sources or recycled paper, which means a 50-70% reduction in CO

2 emissions. Reusable alternatives are more expensive and more energy-intensive due to increased transportation and cleaning costs based on the Confederation of European Paper Industries (CEPI) [

47]. The European Paper Recycling Council's (EPRC’s) recycling target is 76% for the 2021-2030 European Declaration [

48].

Currently, the most common packaging material for blueberries is polypropylene (PP) to its durability, moisture resistance and low cost. Although PP has the lowest weight per 1000 kg of blueberry packaging, its environmental performance is inferior to RPLA. PP is made from fossil fuels, and its production is energy-intensive. The energy requirement is between 1.64 and 2.41 kg CO

2 eq./kg virgin PP, but Jahanshahia et al. [

49]found an exceptionally high value in Iran. Despite its recyclability, it can only be around 30% in the EU, while plastic has a recycling rate of 26.9% based on the Plastics Europe Report [

50].

The legislation of European countries promotes two forms of waste management: reuse and recycling. Recycling processes recover materials and energy. However, recycling polymers require special technological installations and a series of preparatory operations [

51,

52]. Therefore, in the case of PP, it is imperative to consider end-of-life options.

In overall conclusion, our research has shown that RPLA packaging has the lowest environmental impact over the entire life cycle and a lower GWP impact in all end-of-life scenarios examined. This lower environmental impact is related to its carbon footprint and energy requirements. However, it is noteworthy that CB packaging has a larger carbon footprint, but overall (for the 11 impacts together), it has a lower environmental impact than traditional incineration. CBC packaging has the highest total environmental impact in the recycling scenario, the largest share of which is marine ecotoxicity.

When examining the energy resources indicators, our results show that, when considering the entire life cycle, the end-of-life stages have the lowest energy resource values, and the production stages have the highest energy resource values for all four packaging materials examined. More than 80% of the fossil abiotic depletion value is given by the Production stage, and in the case of PP, this value is relatively small compared to CB and CBC materials. For sustainable energy consumption, it is worth looking for solutions that can simultaneously meet the need for reliable energy sources and energy storage systems [

53,

54].

Overall, enhancing the environmental friendliness of blueberry packaging exemplifies our dedication to sustainability and assists in achieving global environmental objectives. Adopting environmentally friendly packaging solutions and transitioning to a circular economy represent critical measures to guarantee that blueberries, a nutritious and widely consumed food, remain sustainably accessible for future generations.

Our analyses have highlighted that cradle-to-grave life cycle assessments for the packaging materials are essential to find the best environmentally friendly solution. These assessments should consider all relevant factors, from raw material extraction, production, transportation, and use to waste management processes. At the same time, in addition to the environmental effects, it is also essential to consider the energy parameters.

Figure 1.

The tested packaging types.

Figure 1.

The tested packaging types.

Figure 2.

Impact percentage distribution of main impacts regarding packaging CB by CML 2016 excluding biogenic carbon impact assessment method. Normalization method: CML 2001 - Jan. 2016, EU25+3, year 2000, excl. biogenic carbon (region equivalents). Weighting method: Sphera LCIA Survey 2012, Europe, CML 2016, excl. biogenic carbon (region equivalents weighted). (Functional unit: 1 piece of packaging).

Figure 2.

Impact percentage distribution of main impacts regarding packaging CB by CML 2016 excluding biogenic carbon impact assessment method. Normalization method: CML 2001 - Jan. 2016, EU25+3, year 2000, excl. biogenic carbon (region equivalents). Weighting method: Sphera LCIA Survey 2012, Europe, CML 2016, excl. biogenic carbon (region equivalents weighted). (Functional unit: 1 piece of packaging).

Figure 3.

Impact percentage distribution of main impacts regarding packaging CBC by CML 2016 excluding biogenic carbon impact assessment method. Normalization method: CML 2001 - Jan. 2016, EU25+3, year 2000, excl. biogenic carbon (region equivalents). Weighting method: Sphera LCIA Survey 2012, Europe, CML 2016, excl. biogenic carbon (region equivalents weighted). (Functional unit: 1 piece of packaging).

Figure 3.

Impact percentage distribution of main impacts regarding packaging CBC by CML 2016 excluding biogenic carbon impact assessment method. Normalization method: CML 2001 - Jan. 2016, EU25+3, year 2000, excl. biogenic carbon (region equivalents). Weighting method: Sphera LCIA Survey 2012, Europe, CML 2016, excl. biogenic carbon (region equivalents weighted). (Functional unit: 1 piece of packaging).

Figure 4.

Impact percentage distribution regarding packaging PP by CML 2016 excluding biogenic carbon impact assessment method. Normalization method: CML 2001 - Jan. 2016, EU25+3, year 2000, excl. biogenic carbon (region equivalents). Weighting method: Sphera LCIA Survey 2012, Europe, CML 2016, excl. biogenic carbon (region equivalents weighted). (Functional unit: 1 piece of packaging).

Figure 4.

Impact percentage distribution regarding packaging PP by CML 2016 excluding biogenic carbon impact assessment method. Normalization method: CML 2001 - Jan. 2016, EU25+3, year 2000, excl. biogenic carbon (region equivalents). Weighting method: Sphera LCIA Survey 2012, Europe, CML 2016, excl. biogenic carbon (region equivalents weighted). (Functional unit: 1 piece of packaging).

Figure 5.

Impact percentage distribution regarding packaging RPLA by CML 2016 excluding biogenic carbon impact assessment method. Normalization method: CML 2001 - Jan. 2016, EU25+3, year 2000, excl. biogenic carbon (region equivalents). Weighting method: Sphera LCIA Survey 2012, Europe, CML 2016, excl. biogenic carbon (region equivalents weighted). (Functional unit: 1 piece of packaging).

Figure 5.

Impact percentage distribution regarding packaging RPLA by CML 2016 excluding biogenic carbon impact assessment method. Normalization method: CML 2001 - Jan. 2016, EU25+3, year 2000, excl. biogenic carbon (region equivalents). Weighting method: Sphera LCIA Survey 2012, Europe, CML 2016, excl. biogenic carbon (region equivalents weighted). (Functional unit: 1 piece of packaging).

Figure 6.

Results of recycling for the four types of packaging in percent. Normalization method: CML 2001 - Jan. 2016, EU25+3, year 2000, excl. biogenic carbon (region equivalents). Weighting method: Sphera LCIA Survey 2012, Europe, CML 2016, excl. biogenic carbon (region equivalents weighted). (Functional unit: 1 piece of packaging).

Figure 6.

Results of recycling for the four types of packaging in percent. Normalization method: CML 2001 - Jan. 2016, EU25+3, year 2000, excl. biogenic carbon (region equivalents). Weighting method: Sphera LCIA Survey 2012, Europe, CML 2016, excl. biogenic carbon (region equivalents weighted). (Functional unit: 1 piece of packaging).

Figure 7.

Impact percentage distribution regarding all of the packaging by CML 2016 excluding biogenic carbon impact assessment method. (Functional unit: 1 piece of packaging).

Figure 7.

Impact percentage distribution regarding all of the packaging by CML 2016 excluding biogenic carbon impact assessment method. (Functional unit: 1 piece of packaging).

Figure 8.

Impact percentage distribution regarding all of the packaging by CML 2016 excluding biogenic carbon impact assessment method. (Functional unit: 1 piece of packaging).

Figure 8.

Impact percentage distribution regarding all of the packaging by CML 2016 excluding biogenic carbon impact assessment method. (Functional unit: 1 piece of packaging).

Figure 9.

Impact percentage distribution regarding all of the packaging by CML 2016 excluding biogenic carbon impact assessment method. (Functional unit: 1 piece of packaging).

Figure 9.

Impact percentage distribution regarding all of the packaging by CML 2016 excluding biogenic carbon impact assessment method. (Functional unit: 1 piece of packaging).

Figure 10.

Comparison of GWP (100 years, excluding biogenic carbon) between recycling (R) and composting (C). Functional unit: 1 piece of packaging, [kg CO2 – eq.]. Explanations: P1 = packaging 1 (CB), P2 = packaging 2 (CBC), P3 = packaging 3 (PP), and P4 = packaging 4 (RPLA).

Figure 10.

Comparison of GWP (100 years, excluding biogenic carbon) between recycling (R) and composting (C). Functional unit: 1 piece of packaging, [kg CO2 – eq.]. Explanations: P1 = packaging 1 (CB), P2 = packaging 2 (CBC), P3 = packaging 3 (PP), and P4 = packaging 4 (RPLA).

Figure 11.

Comparison of GWP (100 years, excluding biogenic carbon) between disposal (D) and incineration (I). Functional unit: 1 piece of packaging, [kg C02 – eq.]. Explanations: P1 = packaging 1 (CB), P2 = packaging 2 (CBC), P3 = packaging 3 (PP), and P4 = packaging 4 (RPLA).

Figure 11.

Comparison of GWP (100 years, excluding biogenic carbon) between disposal (D) and incineration (I). Functional unit: 1 piece of packaging, [kg C02 – eq.]. Explanations: P1 = packaging 1 (CB), P2 = packaging 2 (CBC), P3 = packaging 3 (PP), and P4 = packaging 4 (RPLA).

Figure 12.

Comparison of environmental impact values regarding packaging materials after normalization and weighting in nanograms. Normalization method: EU 25 + 3, 2000, excl. biogenic carbon (region equivalents). Weighting method: Sphera LCIA Survey, 2012, Europe, excl. biogenic carbon (region equivalents). (Functional unit: 1 piece of packaging material).

Figure 12.

Comparison of environmental impact values regarding packaging materials after normalization and weighting in nanograms. Normalization method: EU 25 + 3, 2000, excl. biogenic carbon (region equivalents). Weighting method: Sphera LCIA Survey, 2012, Europe, excl. biogenic carbon (region equivalents). (Functional unit: 1 piece of packaging material).

Table 1.

The tested packaging types.

Table 1.

The tested packaging types.

| Packaging name |

Weight without lid [g] |

Weight with lid [g] |

The number of aeration holes |

CB – cardboard packaging

(SoFruPak)

Packaging 1

|

|

23.41 |

18.0 |

CBC – cardboard packaging with cellulose lid (SoFruPak)

Packaging 2

|

22.36 |

32.36 |

10.00 |

PP – polypropylene packaging, control

Packaging 3

|

6.26 |

11.41 |

22.00 |

RPLA – rice straw punnet with PLA lid

(Bio4Pack)

Packaging 4

|

11.46 |

18.37 |

10.00 |

Table 2.

Normalized and weighted impacts regarding cradle-to-cradle LCA (looping between end-of-life and production stages) based on the CML 2016 method in kilograms. Normalization method: EU 25 + 3, 2000, excl. biogenic carbon (region equivalents). Weighting method: Sphera LCIA Survey, 2012, Europe, excl. biogenic carbon (region equivalents). (Functional unit: 1 piece of packaging material).

Table 2.

Normalized and weighted impacts regarding cradle-to-cradle LCA (looping between end-of-life and production stages) based on the CML 2016 method in kilograms. Normalization method: EU 25 + 3, 2000, excl. biogenic carbon (region equivalents). Weighting method: Sphera LCIA Survey, 2012, Europe, excl. biogenic carbon (region equivalents). (Functional unit: 1 piece of packaging material).

Environmental impact quantities for cradle-to-cradle LCA

(LCIA method: CML 2016) |

Packaging 1

CB

0.023 kg |

Packaging 2

CBC

0.032 kg |

Packaging 3

PP

0.011 kg |

Packaging 4

RPLA

0.018 kg |

| Abiotic Depletion ADP elements,ADPE

|

1,38E-16 |

3,83E-14 |

6,07E-17 |

4,49E-16 |

| Abiotic Depletion ADP fossils, ADPF

|

8,66E-14 |

1,37E-13 |

5,50E-14 |

7,21E-14 |

| Acidification Potential AP

|

3,41E-14 |

5,82E-14 |

1,56E-14 |

2,17E-14 |

| Eutrophication Potential EP

|

4,68E-15 |

9,90E-15 |

1,92E-15 |

4,44E-15 |

| Fresh Water A. Ecotoxicity Pot. FAETP inf

|

2,24E-15 |

5,12E-15 |

1,42E-15 |

5,51E-14 |

| Global Warming Pot. GWP 100 years

|

7,96E-14 |

1,24E-13 |

4,61E-14 |

4,28E-14 |

| Human Toxicity Potential HTP inf.

|

2,17E-14 |

3,84E-14 |

1,10E-14 |

1,16E-14 |

| Marine A. Ecotox. Pot. MAETP inf.

|

5,59E-13 |

1,41E-12 |

2,73E-13 |

1,29E-13 |

| Ozone Layer Depletion Pot. ODP s.state

|

3,40E-20 |

3,61E-20 |

2,66E-23 |

1,64E-18 |

| Photochem. Ozone Creat. Pot. POCP

|

3,16E-14 |

4,85E-14 |

1,64E-14 |

1,77E-14 |

| Terrestric Ecotoxicity Pot. TETP inf.

|

3,49E-15 |

5,80E-15 |

7,17E-15 |

4,41E-15 |

| Total |

8,23E-13 |

1,87E-12 |

4,28E-13 |

3,59E-13 |

Table 3.

Normalized and weighted impacts regarding cradle-to-grave LCA (with composting EoL scenario) based on the CML 2016 method in kilograms. Normalization method: EU 25 + 3, 2000, excl. biogenic carbon (region equivalents). Weighting method: Sphera LCIA Survey, 2012, Europe, excl. biogenic carbon (region equivalents). (Functional unit: 1 piece of packaging material).

Table 3.

Normalized and weighted impacts regarding cradle-to-grave LCA (with composting EoL scenario) based on the CML 2016 method in kilograms. Normalization method: EU 25 + 3, 2000, excl. biogenic carbon (region equivalents). Weighting method: Sphera LCIA Survey, 2012, Europe, excl. biogenic carbon (region equivalents). (Functional unit: 1 piece of packaging material).

Environmental impact quantities

(CML 2016) |

Packaging 1

CB |

Packaging 2

CBC |

Packaging 3

PP |

Packaging 4

RPLA |

| Abiotic Depletion ADP elements,ADPE

|

3,14E-16 |

3,85E-14 |

3,72E-16 |

5,29E-16 |

| Abiotic Depletion ADP fossils, ADPF

|

1,09E-13 |

1,68E-13 |

1,49E-13 |

8,38E-14 |

| Acidification Potential AP

|

4,54E-14 |

7,39E-14 |

1,26E-14 |

2,69E-14 |

| Eutrophication Potential EP

|

8,49E-15 |

1,52E-14 |

2,46E-15 |

6,27E-15 |

| Fresh Water A. Ecotoxicity Pot. FAETP inf

|

2,14E-14 |

3,17E-14 |

1,45E-14 |

6,97E-14 |

| Global Warming Pot. GWP 100 years

|

9,88E-14 |

1,51E-13 |

7,17E-14 |

5,34E-14 |

| Human Toxicity Potential HTP inf.

|

6,94E-14 |

1,05E-13 |

3,85E-14 |

4,60E-14 |

| Marine A. Ecotox. Pot. MAETP inf.

|

5,88E-13 |

1,45E-12 |

2,89E-13 |

1,36E-13 |

| Ozone Layer Depletion Pot. ODP

|

2,04E-19 |

2,72E-19 |

3,65E-22 |

1,73E-18 |

| Photochem. Ozone Creat. Pot. POCP

|

4,79E-14 |

7,11E-14 |

3,12E-14 |

2,60E-14 |

| Terrestric Ecotoxicity Pot. TETP inf.

|

5,71E-14 |

8,04E-14 |

7,12E-14 |

4,61E-14 |

| Total |

1,05E-12 |

2,18E-12 |

6,81E-13 |

4,95E-13 |

Table 4.

Normalized and weighted impacts regarding cradle-to-grave LCA (with landfilling EoL scenario) based on the CML 2016 method in kilograms. Normalization method: EU 25 + 3, 2000, excl. biogenic carbon (region equivalents). Weighting method: Sphera LCIA Survey, 2012, Europe, excl. biogenic carbon (region equivalents). (Functional unit: 1 piece of packaging material).

Table 4.

Normalized and weighted impacts regarding cradle-to-grave LCA (with landfilling EoL scenario) based on the CML 2016 method in kilograms. Normalization method: EU 25 + 3, 2000, excl. biogenic carbon (region equivalents). Weighting method: Sphera LCIA Survey, 2012, Europe, excl. biogenic carbon (region equivalents). (Functional unit: 1 piece of packaging material).

Environmental impact quantities

(CML 2016) |

Packaging 1

CB |

Packaging 2

CBC |

Packaging 3

PP |

Packaging 4

RPLA |

| Abiotic Depletion ADP elements,ADPE

|

3,8E-16 |

3,86E-14 |

4,03E-16 |

5,78E-16 |

| Abiotic Depletion ADP fossils, ADPF

|

1,14E-13 |

1,75E-13 |

1,51E-13 |

8,67E-14 |

| Acidification Potential AP

|

5,07E-14 |

8,13E-14 |

1,47E-14 |

3,06E-14 |

| Eutrophication Potential EP

|

1,23E-14 |

2,05E-14 |

3,56E-15 |

1,14E-14 |

| Fresh Water A. Ecotoxicity Pot. FAETP inf

|

3,53E-15 |

6,92E-15 |

6,06E-15 |

5,6E-14 |

| Global Warming Pot. GWP 100 years

|

1,31E-13 |

1,96E-13 |

7,2E-14 |

7,14E-14 |

| Human Toxicity Potential HTP inf.

|

3,38E-14 |

5,52E-14 |

2,14E-14 |

1,8E-14 |

| Marine A. Ecotox. Pot. MAETP inf.

|

6,41E-13 |

1,52E-12 |

3,15E-13 |

1,74E-13 |

| Ozone Layer Depletion Pot. ODP

|

2,04E-19 |

2,72E-19 |

3,66E-22 |

1,73E-18 |

| Photochem. Ozone Creat. Pot. POCP

|

7,27E-14 |

1,06E-13 |

3,25E-14 |

3,91E-14 |

| Terrestric Ecotoxicity Pot. TETP inf.

|

5,82E-15 |

9,04E-15 |

4,7E-14 |

6,48E-15 |

| Total |

1,07E-12 |

2,21E-12 |

6,64E-13 |

4,94E-13 |

Table 5.

Normalized and weighted impacts regarding cradle-to-grave LCA (with incineration EoL scenario) based on the CML 2016 method in kilograms. Normalization method: EU 25 + 3, 2000, excl. biogenic carbon (region equivalents). Weighting method: Sphera LCIA Survey, 2012, Europe, excl. biogenic carbon (region equivalents). (Functional unit: 1 piece of packaging material).

Table 5.

Normalized and weighted impacts regarding cradle-to-grave LCA (with incineration EoL scenario) based on the CML 2016 method in kilograms. Normalization method: EU 25 + 3, 2000, excl. biogenic carbon (region equivalents). Weighting method: Sphera LCIA Survey, 2012, Europe, excl. biogenic carbon (region equivalents). (Functional unit: 1 piece of packaging material).

Environmental impact quantities

(CML 2016) |

Packaging 1

CB |

Packaging 2

CBC |

Packaging 3

PP |

Packaging 4

RPLA |

| Abiotic Depletion ADP elements,ADPE

|

3,91E-16 |

3,86E-14 |

4,06E-16 |

6,03E-16 |

| Abiotic Depletion ADP fossils, ADPF

|

1,12E-13 |

1,71E-13 |

1,50E-13 |

8,61E-14 |

| Acidification Potential AP

|

5,07E-14 |

8,13E-14 |

1,48E-14 |

3,24E-14 |

| Eutrophication Potential EP

|

9,70E-15 |

1,69E-14 |

2,99E-15 |

7,45E-15 |

| Fresh Water A. Ecotoxicity Pot. FAETP inf

|

3,45E-15 |

6,80E-15 |

5,98E-15 |

5,57E-14 |

| Global Warming Pot. GWP 100 years

|

9,82E-14 |

1,50E-13 |

1,13E-13 |

9,02E-14 |

| Human Toxicity Potential HTP inf.

|

3,36E-14 |

5,49E-14 |

2,14E-14 |

1,85E-14 |

| Marine A. Ecotox. Pot. MAETP inf.

|

6,25E-13 |

1,50E-12 |

3,07E-13 |

1,67E-13 |

| Ozone Layer Depletion Pot. ODP

|

2,04E-19 |

2,72E-19 |

3,68E-22 |

1,73E-18 |

| Photochem. Ozone Creat. Pot. POCP

|

5,09E-14 |

7,52E-14 |

3,24E-14 |

2,90E-14 |

| Terrestric Ecotoxicity Pot. TETP inf.

|

4,80E-15 |

7,62E-15 |

4,62E-14 |

5,44E-15 |

| Total |

9,89E-13 |

2,10E-12 |

6,94E-13 |

4,92E-13 |

Table 6.

Carbon footprint comparison for packaging 1000 kg of blueberries.

Table 6.

Carbon footprint comparison for packaging 1000 kg of blueberries.

Carbon footprint (CF)

[kg CO2 eq.] |

Packaging 1

CB |

Packaging 2

CBC |

Packaging 3

PP |

Packaging 4

RPLA |

| Weight kg/piece

|

0.02341 |

0.03236 |

0.01141 |

0.01837 |

| Recycling |

136.0 |

246.0 |

109.6 |

48.00 |

| Composting |

234.0 |

194.4 |

200.0 |

127.0 |

| Landfilling |

180.4 |

257.0 |

171.2 |

53.60 |

| Conventional incineration |

199.6 |

283.0 |

269.2 |

87.20 |

| Quantity of packing tools per 1000 kg of blueberries (unit: 250 g) |

4,000 |

Table 7.

Energy resources of packaging materials regarding the whole life cycle in the recycling EoL scenario. (Functional unit: 1 piece of packaging material).

Table 7.

Energy resources of packaging materials regarding the whole life cycle in the recycling EoL scenario. (Functional unit: 1 piece of packaging material).

Energy resources

[kg] |

Whole life cycle |

Production stage |

Use stage |

EoL stage

(Recycling) |

| CB 0.02341 kg/piece

|

0.02404 |

0.02362 |

0.00038 |

0.00004 |

| CBC 0.03236 kg/piece

|

0.03692 |

0.03634 |

0.00053 |

0.00005 |

| PP 0.01141 kg/piece

|

0.01324 |

0.01296 |

0.00026 |

0.00002 |

| RPLA 0.01837 kg/piece

|

0.01152 |

0.00042 |

0.01107 |

0.00003 |

Table 8.

Abiotic fossil depletion of packaging materials regarding the whole life cycle with recycling in megajoules. (Functional unit: 1 piece of packaging material).

Table 8.

Abiotic fossil depletion of packaging materials regarding the whole life cycle with recycling in megajoules. (Functional unit: 1 piece of packaging material).

Abiotic fossil depletion

[MJ] |

Whole life cycle |

Production stage |

Use stage |

EoL stage

(Recycling) |

| CB 0.02341 kg/piece

|

0.47474 |

0.4570 |

0.0162 |

0.00154 |

| CBC 0.03236 kg/piece

|

0.74964 |

0.7250 |

0.0225 |

0.00214 |

| PP 0.01141 kg/piece

|

0.30154 |

0.2900 |

0.0108 |

0.00074 |

| RPLA 0.01837 kg/piece

|

0.39591 |

0.0177 |

0.3770 |

0.00121 |

Table 9.

Percentage ratio of ADPE compared to all measured impact categories in the production phase after normalization and weighting. Normalization method: EU 25 + 3, 2000, excl. biogenic carbon (region equivalents). Weighting method: Sphera LCIA Survey, 2012, Europe, excl. biogenic carbon (region equivalents). (Functional unit: 1 piece of packaging material).

Table 9.

Percentage ratio of ADPE compared to all measured impact categories in the production phase after normalization and weighting. Normalization method: EU 25 + 3, 2000, excl. biogenic carbon (region equivalents). Weighting method: Sphera LCIA Survey, 2012, Europe, excl. biogenic carbon (region equivalents). (Functional unit: 1 piece of packaging material).

Abiotic fossil depletion

[%] |

Production stage |

| cardboard, CB |

10.2 |

| cardboard with cellulose, CBC |

7.1 |

| polypropylene, PP |

12.5 |

| rice straw with PLA lid, RPLA |

34.2 |