Submitted:

14 August 2025

Posted:

19 August 2025

You are already at the latest version

Abstract

Keywords:

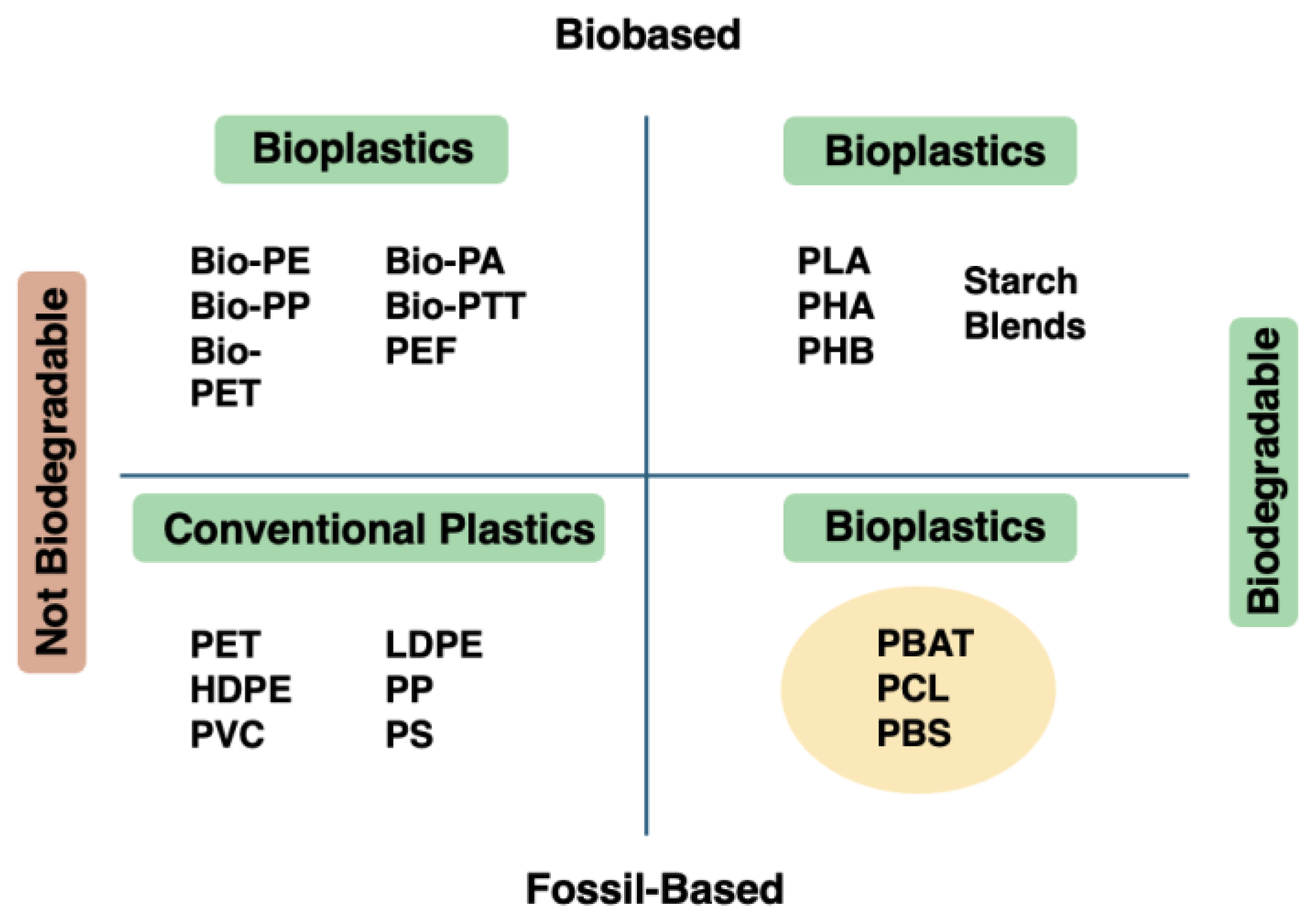

1. Introduction

- 1)

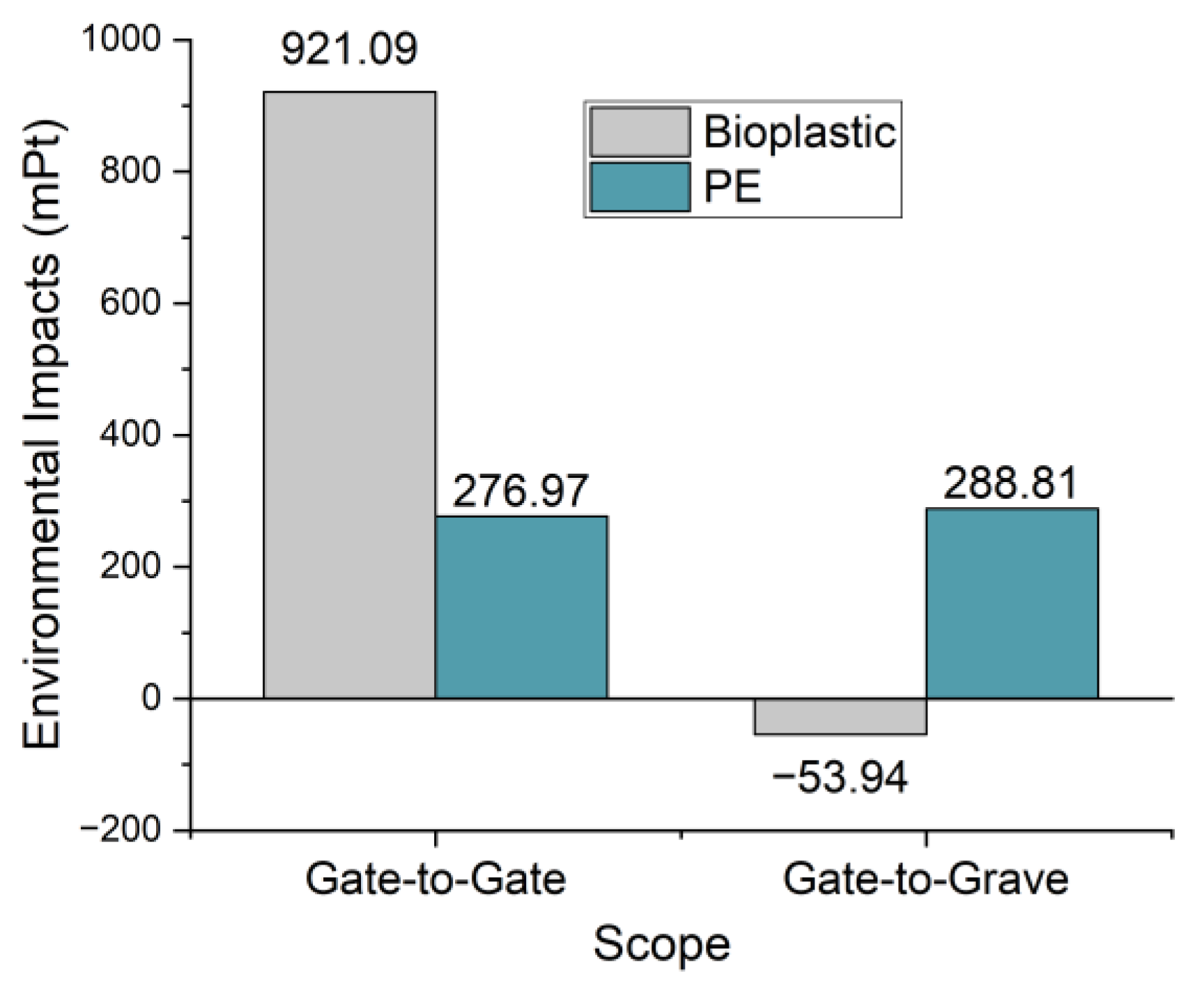

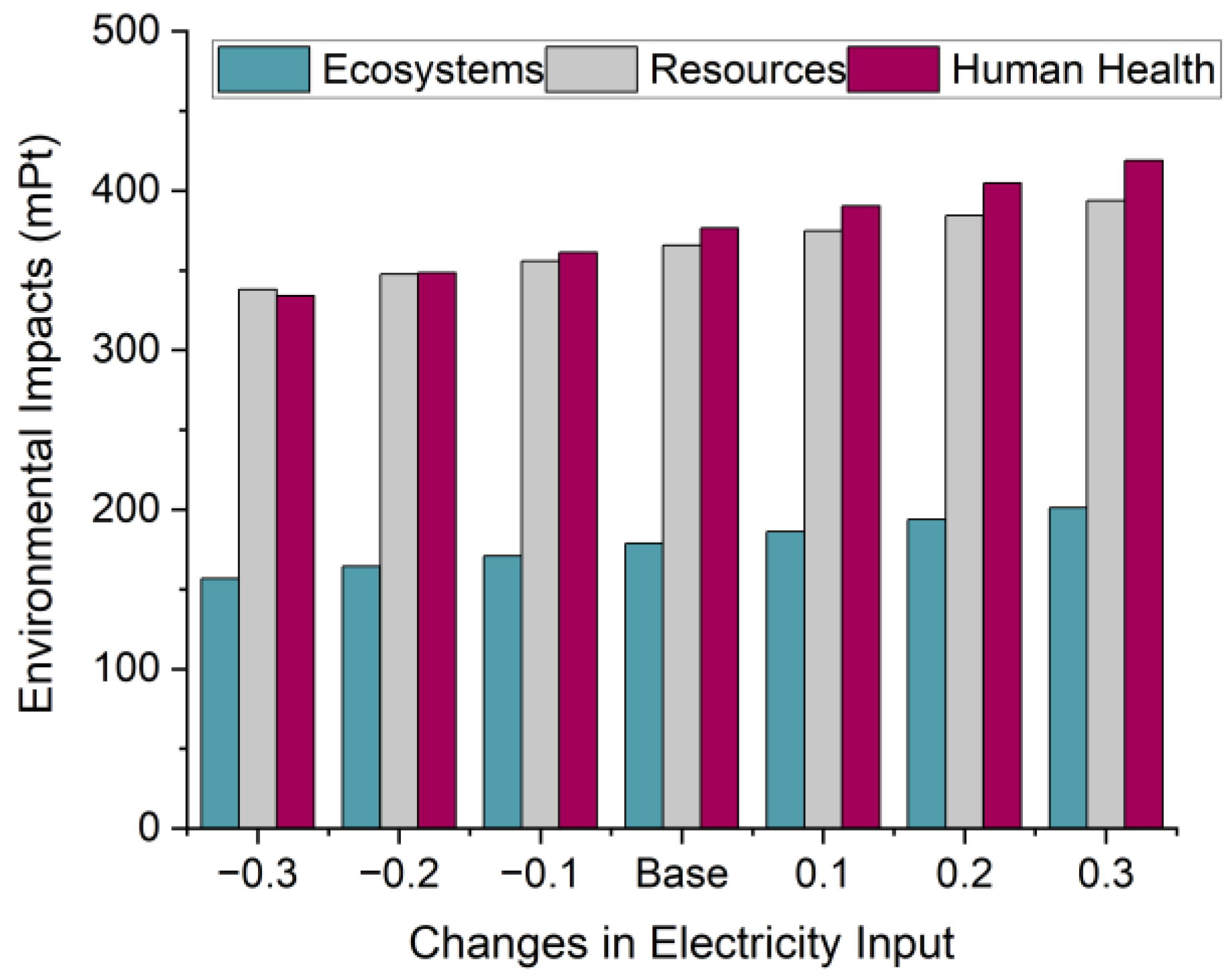

- Quantitative environmental impact analysis (gate-to-gate) and identification of process hotspots: This objective focuses on performing a detailed environmental impact assessment limited to the production phase (gate-to-gate) of the polymer blends. Utilizing ReCiPe method and the IPCC’s Global Warming Potential (GWP) 100-year timeframe, this analysis quantifies impacts across multiple categories including human health, ecosystem quality, and resource depletion. The analysis aims to identify critical process stages or components (“hotspots”) within the production chain that contribute highly to environmental burdens, thereby highlighting opportunities for targeted improvements or innovation.

- 2)

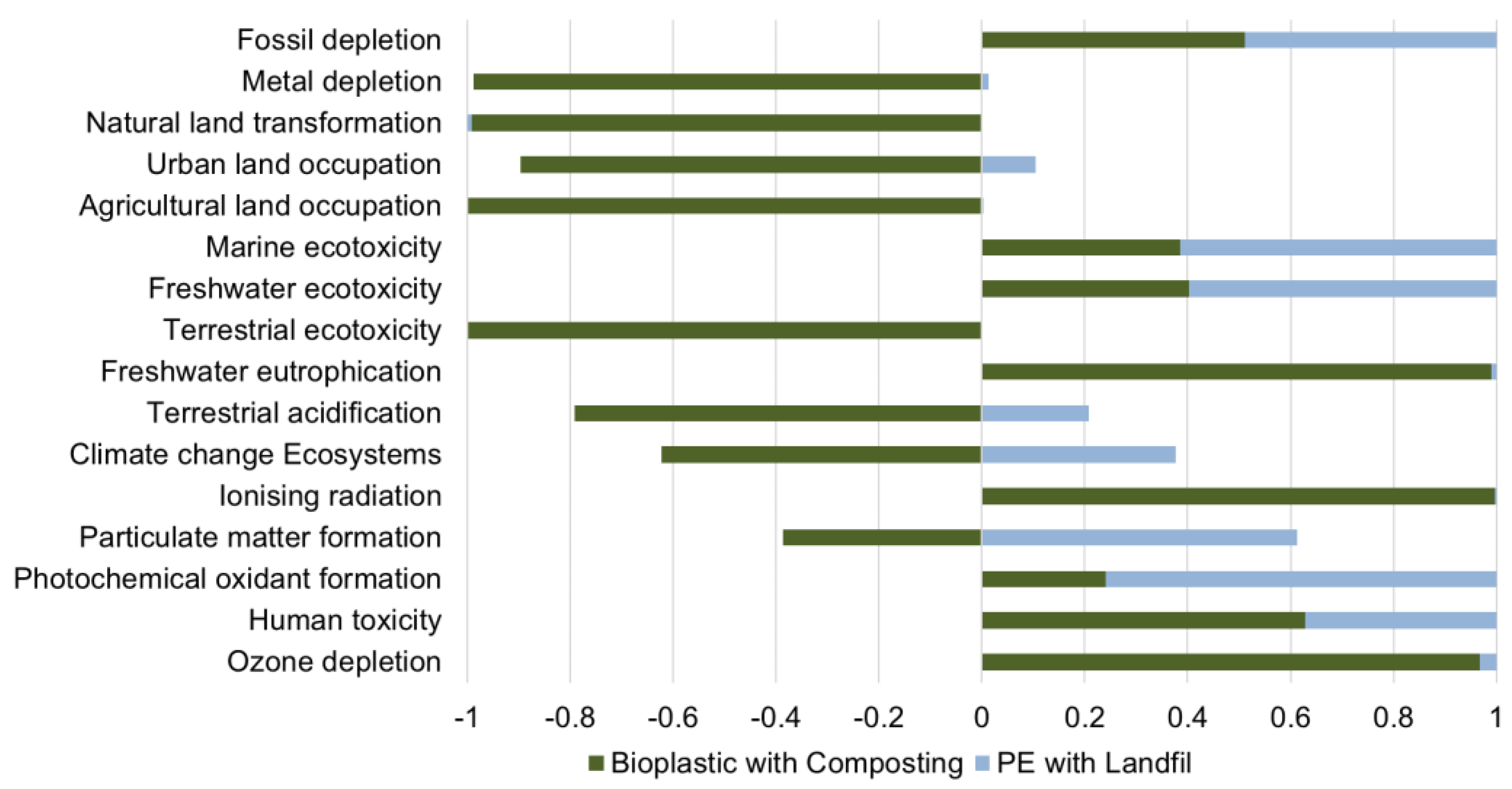

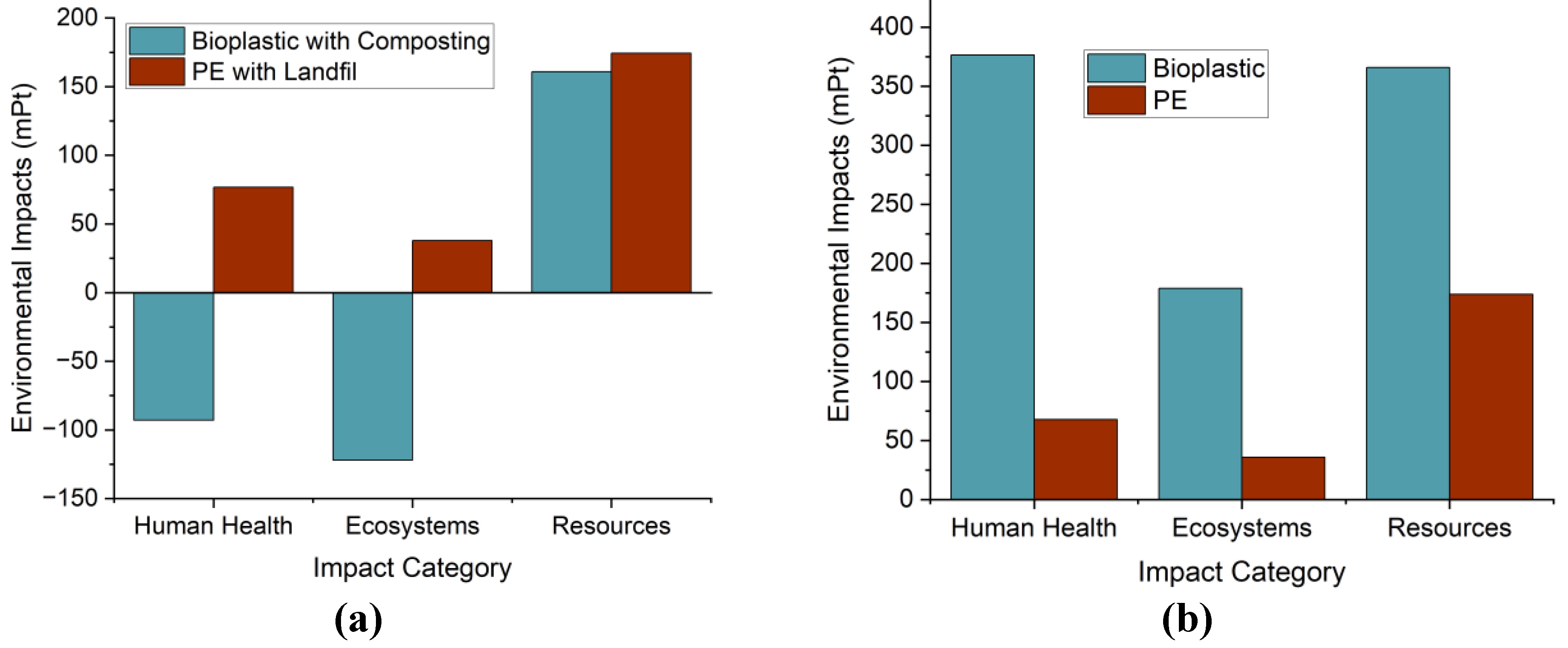

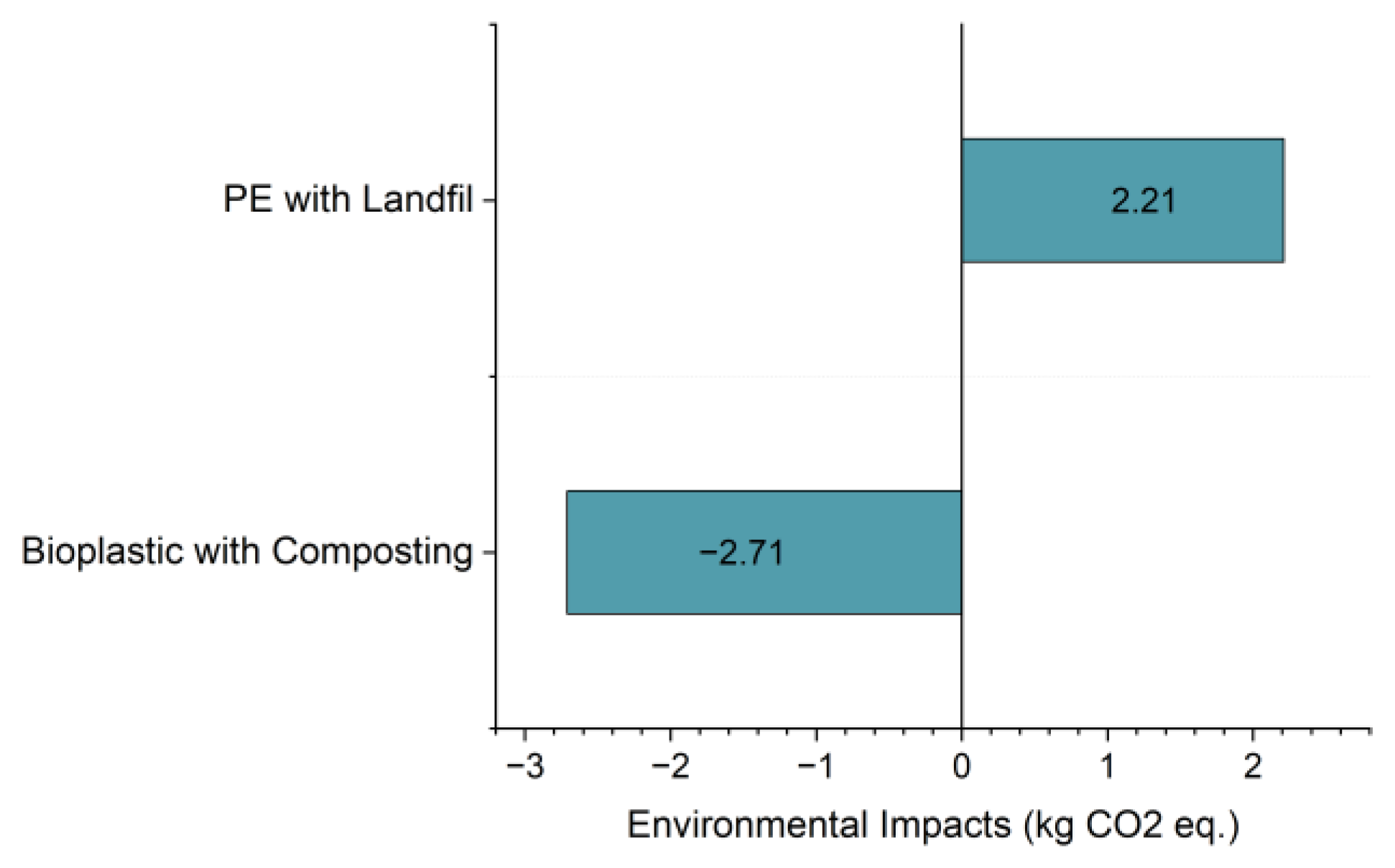

- Comparative screening-level end-of-life assessment: Beyond the production phase, this sub-objective expands the scope to conduct a preliminary evaluation of the end-of-life environmental impacts associated with fossil-based PBAT blends in comparison to conventional PE. This screening-level assessment focuses on examining how the biodegradability and composting potential of PBAT influence key environmental indicators. Both ReCiPe impact indicators and CO₂ emissions will be evaluated to capture environmental performance differences between the two materials. This approach serves as a proof of concept to demonstrate the potential benefits and trade-offs of adopting biodegradable plastics in end-of-life management.

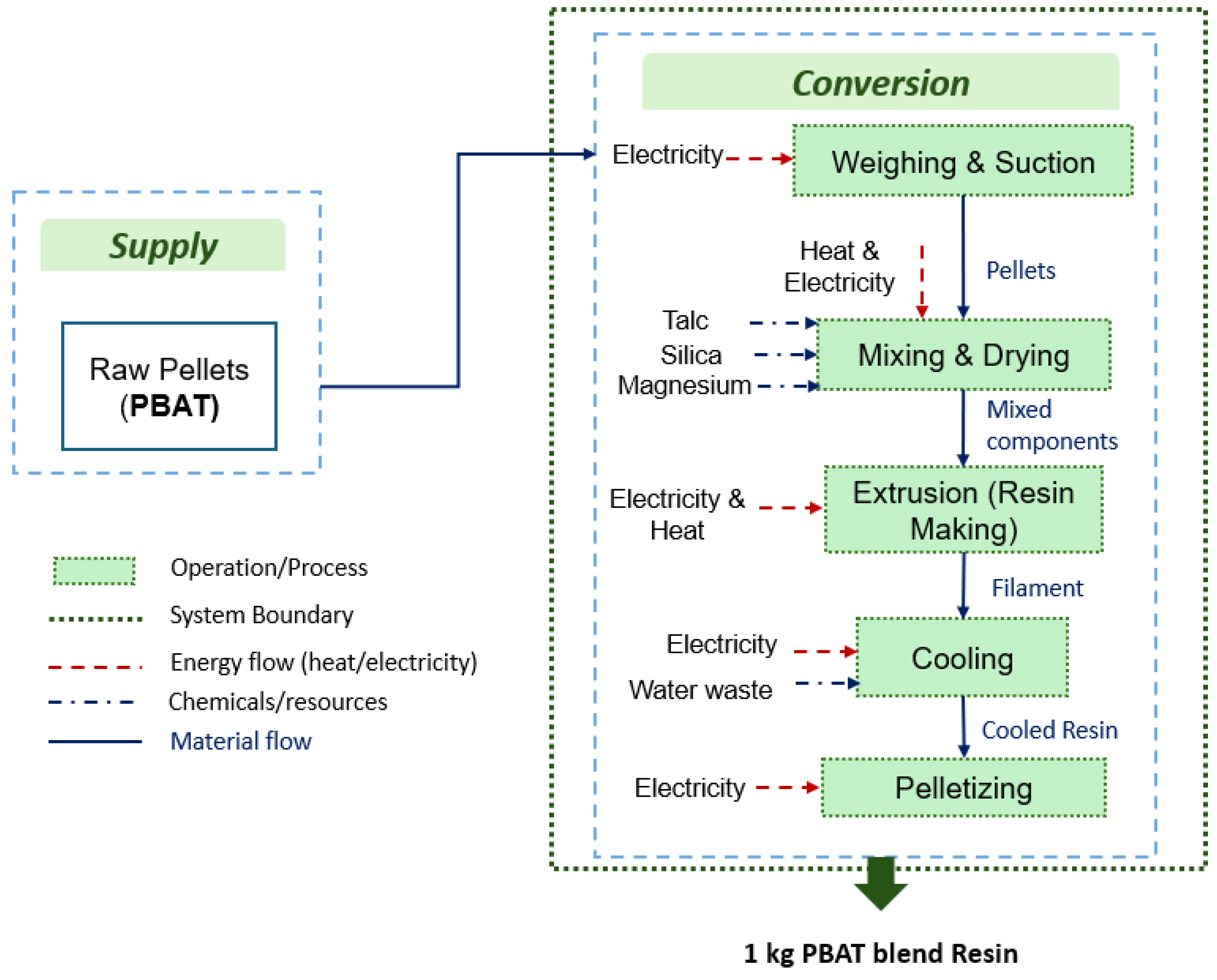

2. Materials and Methods

2.1. Goal of This Study

2.2. Scope of This Study

2.2.1. Functional Unit

2.2.1. System Boundaries

2.2. Life Cycle Inventory (LCI) Analysis

- Transportation Exclusion: All transportation activities, including raw material delivery and product distribution, are excluded from this assessment to maintain a gate-to-gate system boundary focused solely on on-site operations.

- PBAT Approximation Using PE: In this study, PBAT is approximated using PE synthesis for the cup production stage. This approximation is justified by the focus on a gate-to-gate analysis, where the aim is to assess the impacts associated with downstream processing rather than upstream synthesis. Existing research on PBAT has primarily examined its environmental impacts using various raw material scenarios, largely due to the lack of primary manufacturing data [28]. As a result, many studies have relied on assumptions based on PET or PE synthesis. Given that PE and PBAT share similar mechanical properties and behave comparably in extrusion and lamination processes, PE serves as a practical proxy for modeling material flow and energy demand during PBAT-blend product conversion. Furthermore, using PE as the conventional plastic counterpart in comparative assessments ensures consistency in evaluating processing impacts, minimizing bias from differences in upstream production pathways.

- LDPE Resin for PE Cup Production: For polyethylene-based cups, low-density polyethylene (LDPE) granules, used for lamination process, are assumed as the reference material.

- End-of-Life Composting Credit: Composting of PBAT is modeled to yield a substitute for organic fertilizer, with the resulting benefits treated as an avoided burden in the LCA. This approach supports global sustainable development trends, lowers reliance on primary raw materials, and cuts down the volume of waste destined for landfills (Walichnowska et al. 2024). During composting, the biodegradable components convert into CO₂ and water, while the remaining inorganic materials are considered non-toxic to soil. The environmental credits from this substitution are included in the long-term impact assessment, in line with standard system expansion practices in LCA.

2.2. Impact Assessment

- Human Health (measured in DALY);

- Ecosystem Quality (measured in species·yr);

- Resource Scarcity (measured in USD 2013).

- Selection and classification: linking emissions and resource uses to relevant environmental impact categories;

- Characterization: applying scientifically derived characterization factors to quantify the contribution of each elementary flow to an impact category.

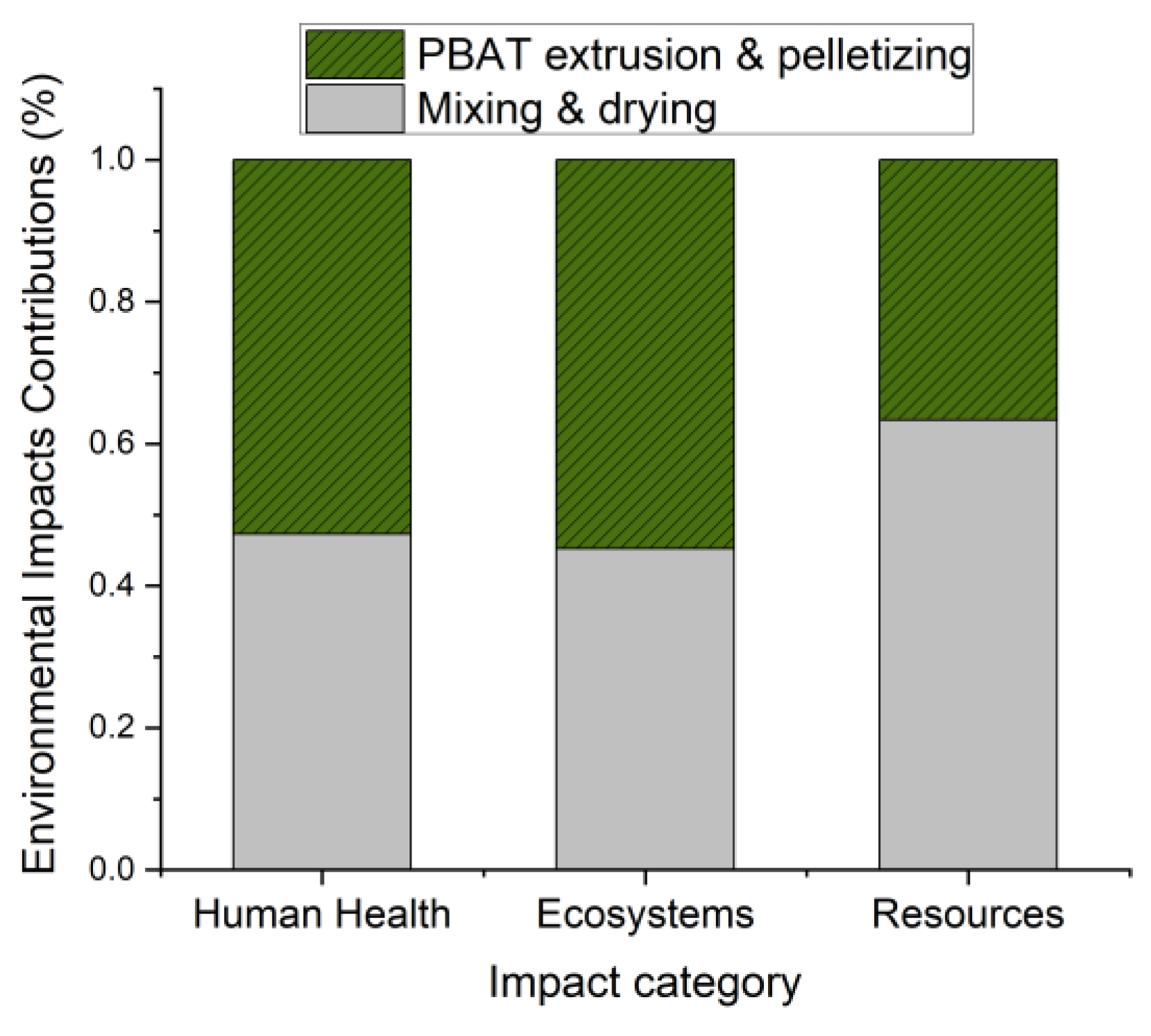

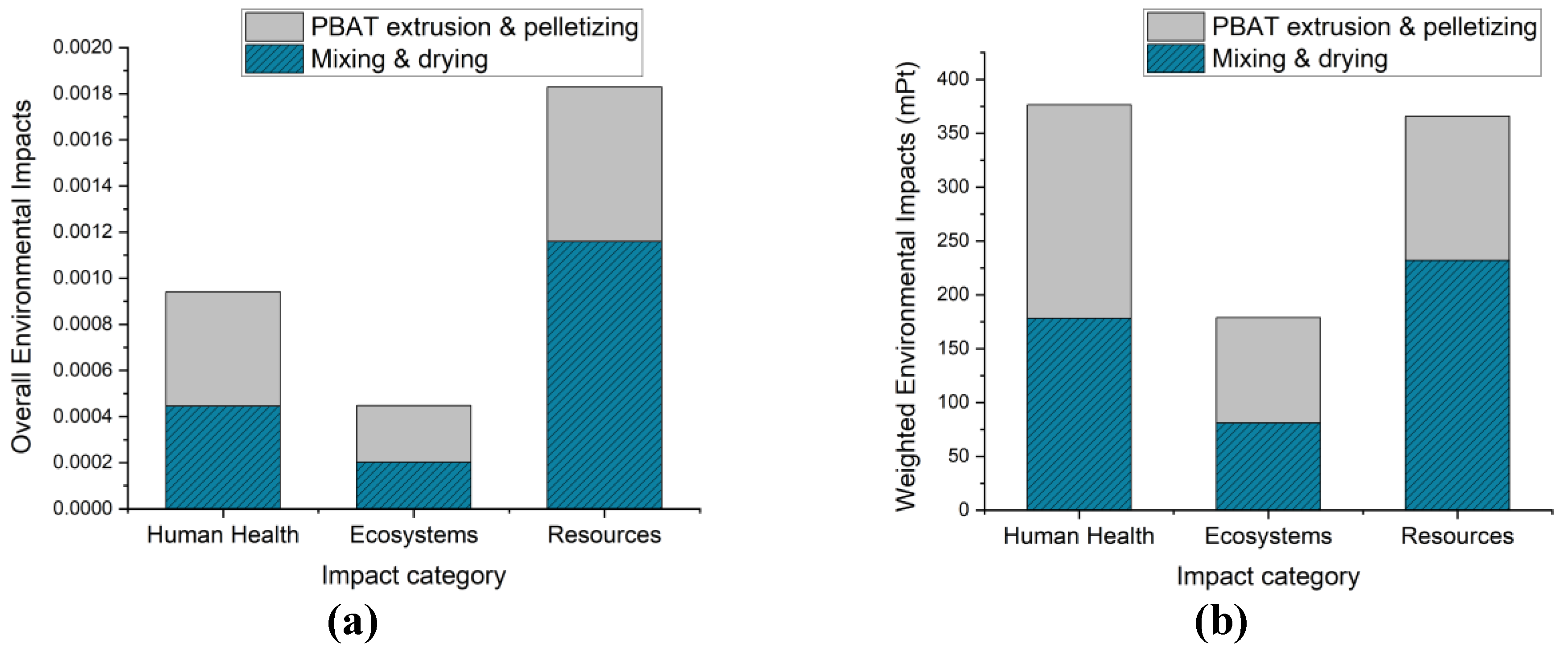

3. Results

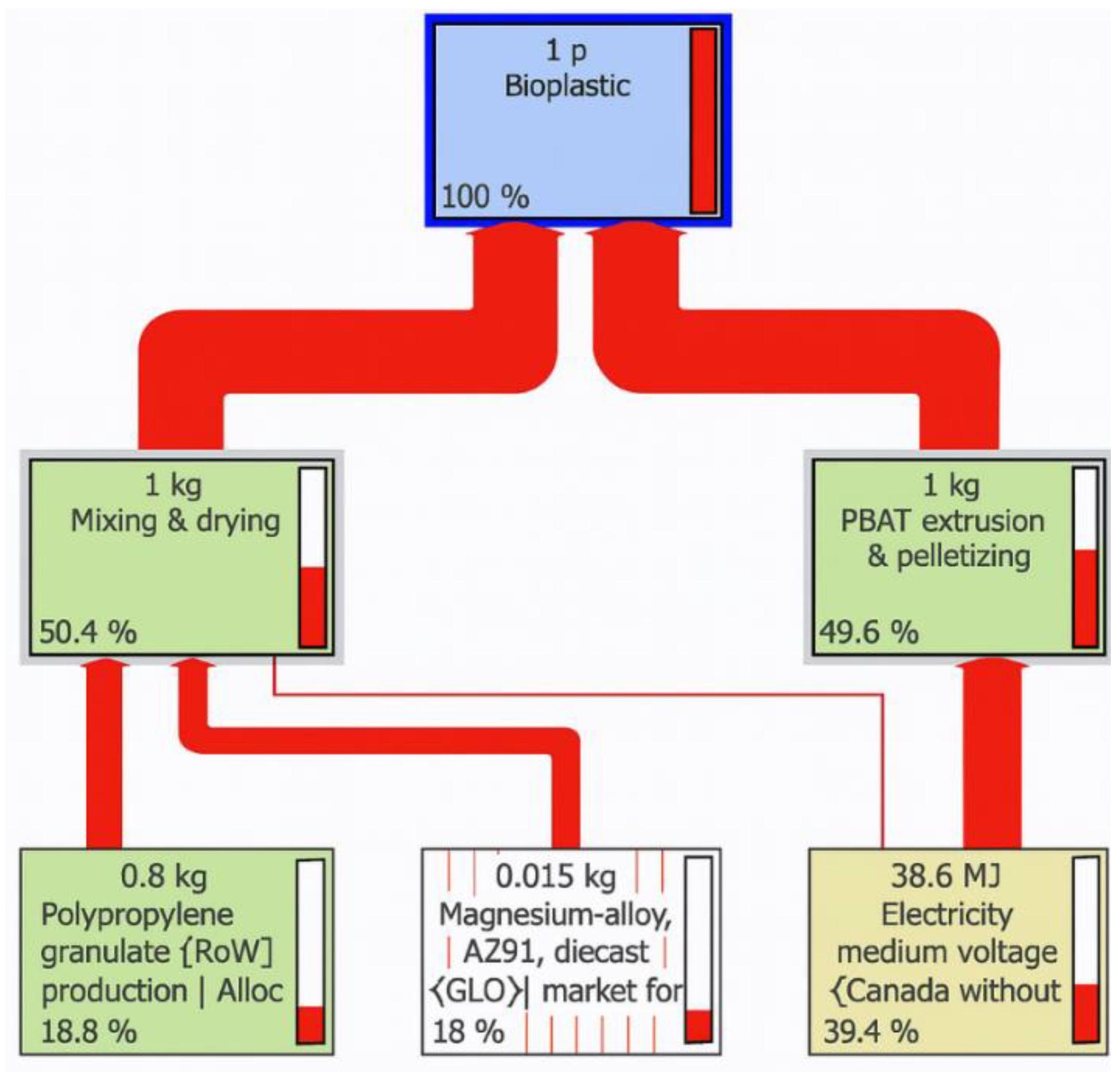

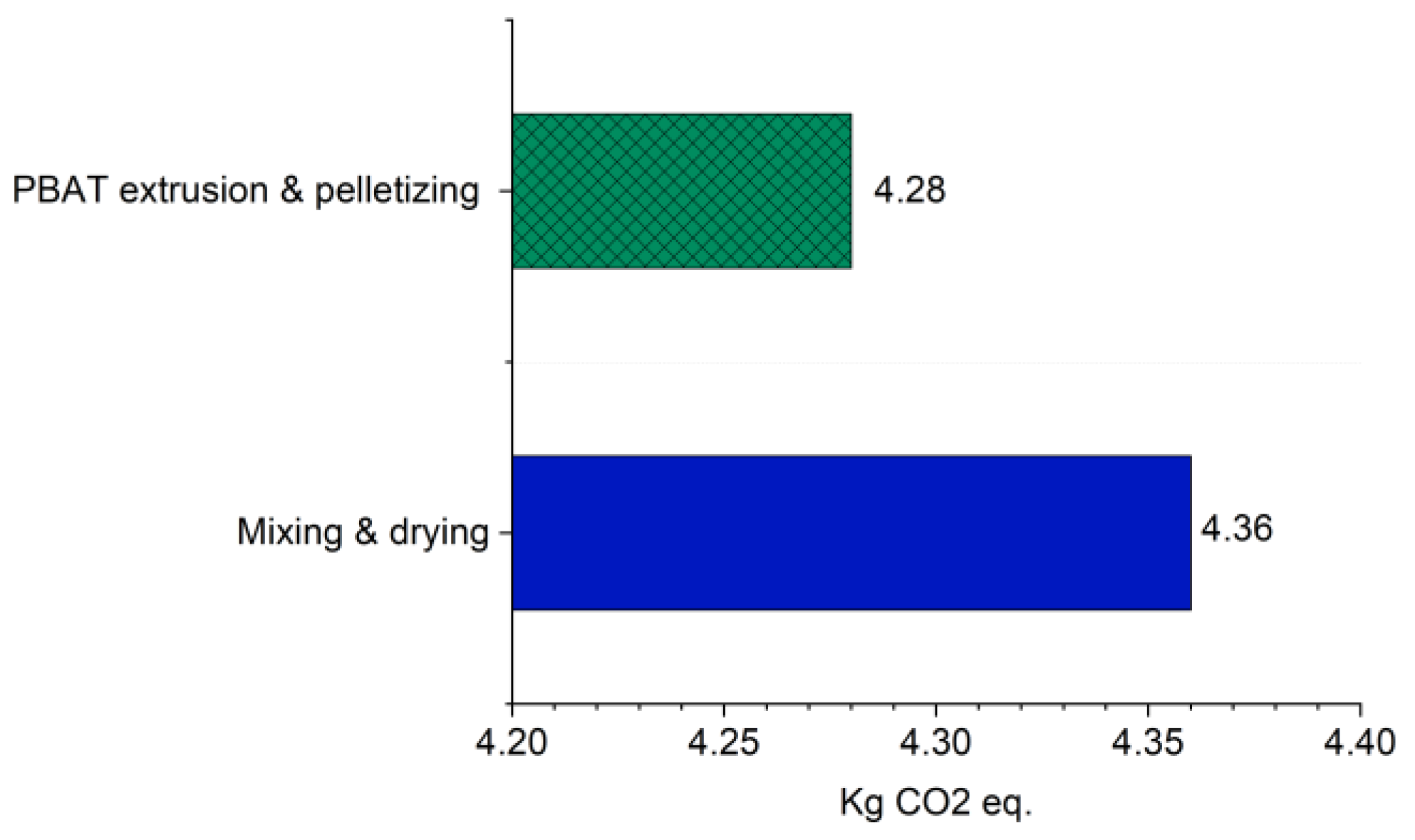

3.1. Gate-to-Gate Analysis (Without End-Of-Life)

- Pt values are relative and used to compare contributions across processes and categories;

- A higher Pt means a greater environmental burden.

3.2. Bioplastics Waste Management and End-Of-Life Options

3.2. Uncertainty Analysis

3. Conclusions

Funding

Acknowledgments

Conflicts of Interest

References

- E. Shlush and M. Davidovich-Pinhas, “Bioplastics for food packaging,” Jul. 01, 2022, Elsevier Ltd. [CrossRef]

- S. S. Ali et al., “Degradation of conventional plastic wastes in the environment: A review on current status of knowledge and future perspectives of disposal,” Science of the Total Environment, vol. 771, p. 144719, 2021. [CrossRef]

- S. Nanda, B. R. Patra, R. Patel, J. Bakos, and A. K. Dalai, “Innovations in applications and prospects of bioplastics and biopolymers: A review,” Environ Chem Lett, vol. 20, no. 1, pp. 379–395, 2022. [CrossRef]

- S. Nizamuddin, A. J. Baloch, C. Chen, M. Arif, and N. M. Mubarak, “Bio-based plastics, biodegradable plastics, and compostable plastics: Biodegradation mechanism, biodegradability standards and environmental stratagem,” Int Biodeterior Biodegradation, vol. 195, p. 105887, 2024. [CrossRef]

- N. Peelman et al., “Application of bioplastics for food packaging,” Aug. 2013. [CrossRef]

- G. Bishop, D. Styles, and P. N. L. Lens, “Environmental performance comparison of bioplastics and petrochemical plastics: A review of life cycle assessment (LCA) methodological decisions,” May 01, 2021, Elsevier B.V. [CrossRef]

- K. Changwichan, T. Silalertruksa, and S. H. Gheewala, “Eco-efficiency assessment of bioplastics production systems and end-of-life options,” Sustainability, vol. 10, no. 4, p. 952, 2018. [CrossRef]

- E. C. Van Roijen and S. A. Miller, “A review of bioplastics at end-of-life: Linking experimental biodegradation studies and life cycle impact assessments,” Jun. 01, 2022, Elsevier B.V. [CrossRef]

- S. Roy, T. Ghosh, W. Zhang, and J. W. Rhim, “Recent progress in PBAT-based films and food packaging applications: A mini-review,” Mar. 30, 2024, Elsevier Ltd. [CrossRef]

- S.-J. Zhou et al., “A high-performance and cost-effective PBAT/montmorillonite/lignin ternary composite film for sustainable production,” ACS Sustain Chem Eng, vol. 12, no. 40, pp. 14704–14715, 2024. [CrossRef]

- G. Vinci, R. Ruggieri, A. Billi, C. Pagnozzi, M. V. Di Loreto, and M. Ruggeri, “Sustainable management of organic waste and recycling for bioplastics: A lca approach for the italian case study,” Sustainability (Switzerland), vol. 13, no. 11, Jun. 2021. [CrossRef]

- A. Olagunju and S. L. Kiambi, “Life Cycle Analysis (LCA) of Bioplastics Compared to Conventional Plastics: A Critical Sustainability Perspective,” Biomass-based Bioplastic and Films: Preparation, Characterization, and Application, pp. 175–205, 2024. [CrossRef]

- M. Islam, T. Xayachak, N. Haque, D. Lau, M. Bhuiyan, and B. K. Pramanik, “Impact of bioplastics on environment from its production to end-of-life,” Aug. 01, 2024, Institution of Chemical Engineers. [CrossRef]

- N. Akbarian-Saravi, T. Sowlati, H. Ahmad, K. Hewage, R. Sadiq, and A. S. Milani, “Life cycle assessment of hemp-based biocomposites production for agricultural emission mitigation strategies: a case study,” in Biocomposites and the Circular Economy, Elsevier, 2025, pp. 261–285. [CrossRef]

- S. R. Hobbs, T. M. Harris, W. J. Barr, and A. E. Landis, “Life cycle assessment of bioplastics and food waste disposal methods,” Sustainability (Switzerland), vol. 13, no. 12, Jun. 2021. [CrossRef]

- C. Luo et al., “Comparative life cycle assessment of PBAT from fossil-based and second-generation generation bio-based feedstocks,” Science of the Total Environment, vol. 954, Dec. 2024. [CrossRef]

- B.-X. Wang, Y. Cortes-Peña, B. P. Grady, G. W. Huber, and V. M. Zavala, “Techno-economic analysis and life cycle assessment of the production of biodegradable polyaliphatic–polyaromatic polyesters,” ACS Sustain Chem Eng, vol. 12, no. 24, pp. 9156–9167, 2024. [CrossRef]

- V. C. Beber et al., “Effect of Babassu natural filler on PBAT/PHB biodegradable blends: An investigation of thermal, mechanical, and morphological behavior,” Materials, vol. 11, no. 5, May 2018. [CrossRef]

- B. Choi, S. Yoo, and S. Il Park, “Carbon footprint of packaging films made from LDPE, PLA, and PLA/PBAT blends in South Korea,” Sustainability (Switzerland), vol. 10, no. 7, Jul. 2018. [CrossRef]

- U. Suwanmanee, N. Charoennet, T. Leejarkpai, and T. Mungcharoen, “Comparative life cycle assessment of bio-based garbage bags: A case study on bio-PE and PBAT/starch,” Materials and Technologies for Energy Efficiency; Universal-Publishers: Boca Raton, FL, USA, pp. 193–197, 2015.

- W. Saibuatrong, N. Cheroennet, and U. Suwanmanee, “Life cycle assessment focusing on the waste management of conventional and bio-based garbage bags,” J Clean Prod, vol. 158, pp. 319–334, Aug. 2017. [CrossRef]

- B. E. Itabana et al., “Poly (Butylene Adipate-Co-Terephthalate) (PBAT) – Based Biocomposites: A Comprehensive Review,” Dec. 01, 2024, John Wiley and Sons Inc. [CrossRef]

- G. Bishop, D. Styles, and P. N. L. Lens, “Environmental performance comparison of bioplastics and petrochemical plastics: A review of life cycle assessment (LCA) methodological decisions,” Resour Conserv Recycl, vol. 168, p. 105451, May 2021. [CrossRef]

- S. Dadhwal, L. Ashton, E. D. G. Fraser, and M. G. Corradini, Life cycle assessment to evaluate bioplastics as alternatives to petroleum-based plastics in the food industry, vol. 2032. INC, 2024. [CrossRef]

- V. Siracusa, C. Ingrao, A. Lo Giudice, C. Mbohwa, and M. Dalla Rosa, “Environmental assessment of a multilayer polymer bag for food packaging and preservation: An LCA approach,” Food Research International, vol. 62, pp. 151–161, Aug. 2014. [CrossRef]

- F. Perugini, M. L. Mastellone, and U. Arena, “A life cycle assessment of mechanical and feedstock recycling options for management of plastic packaging wastes,” Environmental Progress, vol. 24, no. 2, pp. 137–154, Jul. 2005. [CrossRef]

- C. Caceres-Mendoza, P. Santander-Tapia, F. A. Cruz Sanchez, N. Troussier, M. Camargo, and H. Boudaoud, “Life cycle assessment of filament production in distributed plastic recycling via additive manufacturing,” Cleaner Waste Systems, vol. 5, p. 100100, Aug. 2023. [CrossRef]

- G. Chen et al., “Replacing Traditional Plastics with Biodegradable Plastics: Impact on Carbon Emissions,” Engineering, vol. 32, pp. 152–162, Jan. 2024. [CrossRef]

- “Implementation of modern films in the process of mass packaging of bottles based on the circular economy,” Scientific Papers of Silesian University of Technology Organization and Management Series, vol. 2024, no. 207, 2024. [CrossRef]

- A. J. H. Mark et al., “ReCiPe 2016 : A harmonized life cycle impact assessment method at midpoint and endpoint level Report I: Characterization,” 2017. [CrossRef]

- A. Luo et al., “Comparative life cycle assessment of PBAT from fossil-based and second-generation generation bio-based feedstocks,” Science of the Total Environment, vol. 954, Dec. 2024. [CrossRef]

- T. A. Hamed and A. Alshare, “Environmental Impact of Solar and Wind energy-A Review,” Journal of Sustainable Development of Energy, Water and Environment Systems, vol. 10, no. 2, Jan. 2022. [CrossRef]

- A. Salvi, V. Arosio, L. Monzio Compagnoni, I. Cubiña, G. Scaccabarozzi, and G. Dotelli, “Considering the environmental impact of circular strategies: A dynamic combination of material efficiency and LCA,” J Clean Prod, vol. 387, Feb. 2023. [CrossRef]

- Akbariansaravi, “A SUSTAINABILITY ASSESSMENT MODEL FOR SELECTING PRE- PROCESSING EQUIPMENT IN HEMP-BASED BIOCOMPOSITE SUPPLY CHAINS UNDER TECHNO-ECONOMIC , ENVIRONMENTAL , AND,” no. January, 2025.

- N. Akbarian-Saravi, T. Sowlati, and A. S. Milani, “Cradle-to-gate life cycle assessment of hemp utilization for biocomposite pellet production: A case study with data quality assurance process,” Clean Eng Technol, p. 101027, Jun. 2025. [CrossRef]

- N. Akbarian-Saravi, T. Sowlati, D. Fry, and A. S. Milani, “Techno-economic analysis and multi-criteria assessment of a hemp-based biocomposite production supply chain: a case study,” in Biocomposites and the Circular Economy, Elsevier, 2025, pp. 287–321. [CrossRef]

- N. Akbarian-Saravi, T. Sowlati, and A. S. Milani, “A Robust Analytical Network Process for Biocomposites Supply Chain Design: Integrating Sustainability Dimensions into Feedstock Pre-Processing Decisions,” Sustainability, vol. 17, no. 15, p. 7004, Aug. 2025. [CrossRef]

| Description (unit/day) | Values | References |

|---|---|---|

| Reference Flows | ||

| Kg of PBAT resin | 1 | |

| Input Flows/parameters | ||

| Mixing & Drying | ||

| Feedstock requirement for PBAT (kg/kg of final output) | 0.8 | Industry expert |

| Feedstock requirement for talc (kg/kg of final output) | 0.155 | Industry expert |

| Feedstock requirement for silica (kg/kg of final output) | 0.03 | Industry expert |

| Feedstock requirement for magnesium (kg/kg of final output) | 0.015 | Industry expert |

| Electricity for drying process (KWh/kg of PBAT resin) | 0.128 | [25] |

| Electricity for motor shaft/blending (KWh/kg of PBAT resin) | 0.55 | Eco Invent |

| Electricity for suction and material transfer (KWh/kg of PBAT resin) | 0.75 | [26] |

| Extrusion & pelletizing | ||

| Electricity energy consumption for extrusion (KWh/kg of PBAT resin) | 0.6 | [27] |

| Electricity consumption for cooling (KWh/kg of PBAT resin) | 9.72 | [27] |

| Water consumption for cooling (cooling water) (liter per kg of PBAT resin) | 1.78 | [26] |

| Electricity consumption for pelletizing (kwh/kg of PBAT resin) | 0.15 | [27] |

| Material waste (kg/kg of PBAT) | 0.061 | Industry expert |

| Area of Protection | Impact Category | Unit |

|---|---|---|

| Human Health | Climate Change – Human Health | DALY |

| Human Health | Ozone Depletion | DALY |

| Human Health | Human Toxicity | DALY |

| Human Health | Particulate Matter Formation | DALY |

| Human Health | Ionizing Radiation | DALY |

| Human Health | Photochemical Oxidant Formation | DALY |

| Ecosystems | Climate Change – Ecosystems | species·yr |

| Ecosystems | Terrestrial Acidification | species·yr |

| Ecosystems | Freshwater Eutrophication | species·yr |

| Ecosystems | Marine Eutrophication | species·yr |

| Ecosystems | Terrestrial Ecotoxicity | species·yr |

| Ecosystems | Freshwater Ecotoxicity | species·yr |

| Ecosystems | Marine Ecotoxicity | species·yr |

| Ecosystems | Agricultural Land Occupation | species·yr |

| Ecosystems | Urban Land Occupation | species·yr |

| Ecosystems | Natural Land Transformation | species·yr |

| Resource Scarcity | Fossil Resource Depletion | USD 2013 |

| Resource Scarcity | Mineral Resource Depletion | USD 2013 |

| Damage category | Unit | Mixing & drying | PBAT extrusion & pelletizing | Total |

|---|---|---|---|---|

| Human Health | DALY | 8.99515E-06 | 1.0015E-05 | 1.9E-05 |

| Ecosystems | species.yr | 3.66077E-08 | 4.42523E-08 | 8.09E-08 |

| Resources | $ | 0.357807255 | 0.206742791 | 5.65E-01 |

| Impact category | Value | Unit |

|---|---|---|

| Human health | 49.5 | DALY per person in 2010 |

| Ecosystem | 5,530 | Species year per person in 2010 |

| Resources | 0.00324 | USD2013 per person in 2010 |

Disclaimer/Publisher’s Note: The statements, opinions and data contained in all publications are solely those of the individual author(s) and contributor(s) and not of MDPI and/or the editor(s). MDPI and/or the editor(s) disclaim responsibility for any injury to people or property resulting from any ideas, methods, instructions or products referred to in the content. |

© 2025 by the authors. Licensee MDPI, Basel, Switzerland. This article is an open access article distributed under the terms and conditions of the Creative Commons Attribution (CC BY) license (http://creativecommons.org/licenses/by/4.0/).