Submitted:

21 February 2023

Posted:

27 February 2023

You are already at the latest version

Abstract

Keywords:

1. Introduction

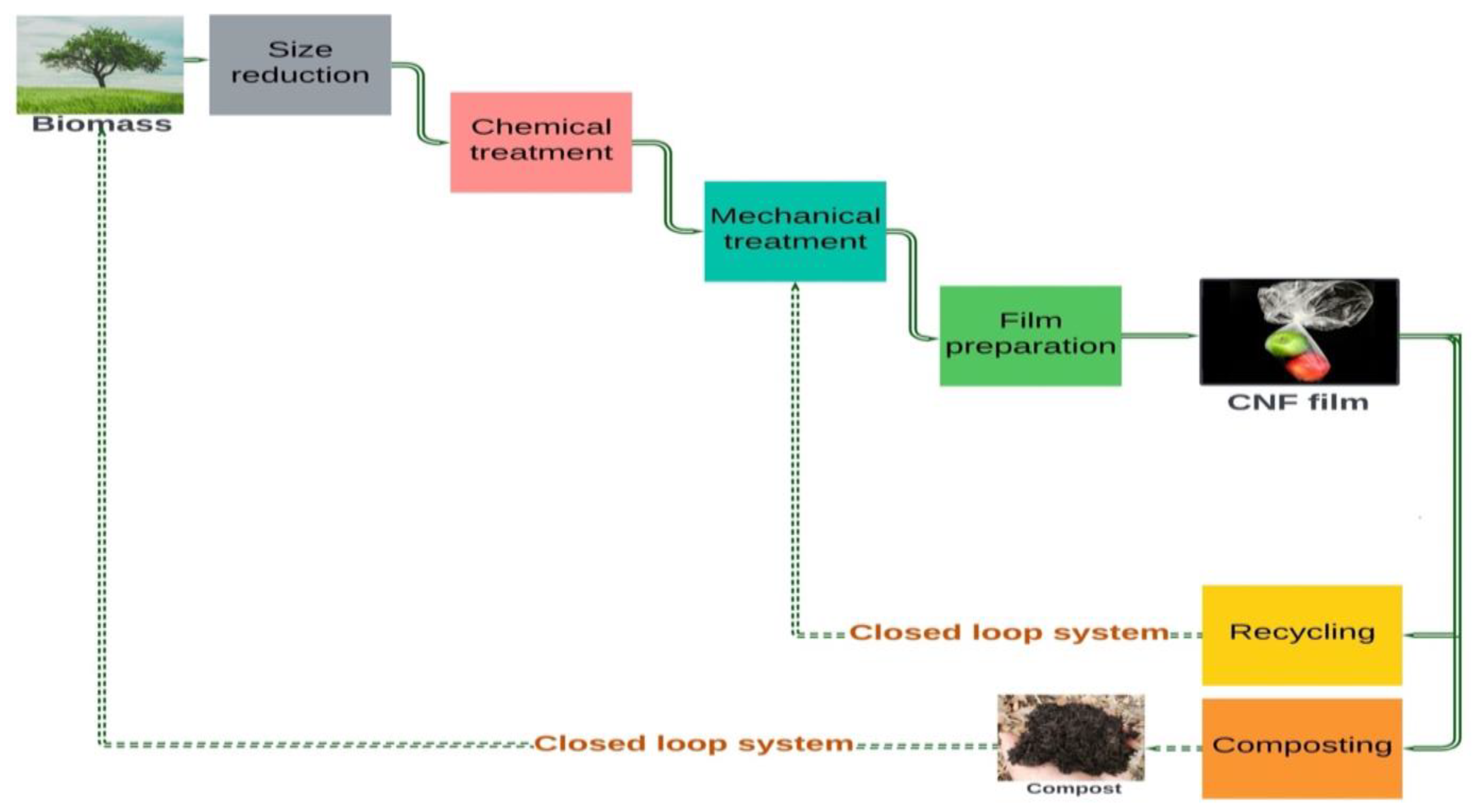

2. Materials and Methods

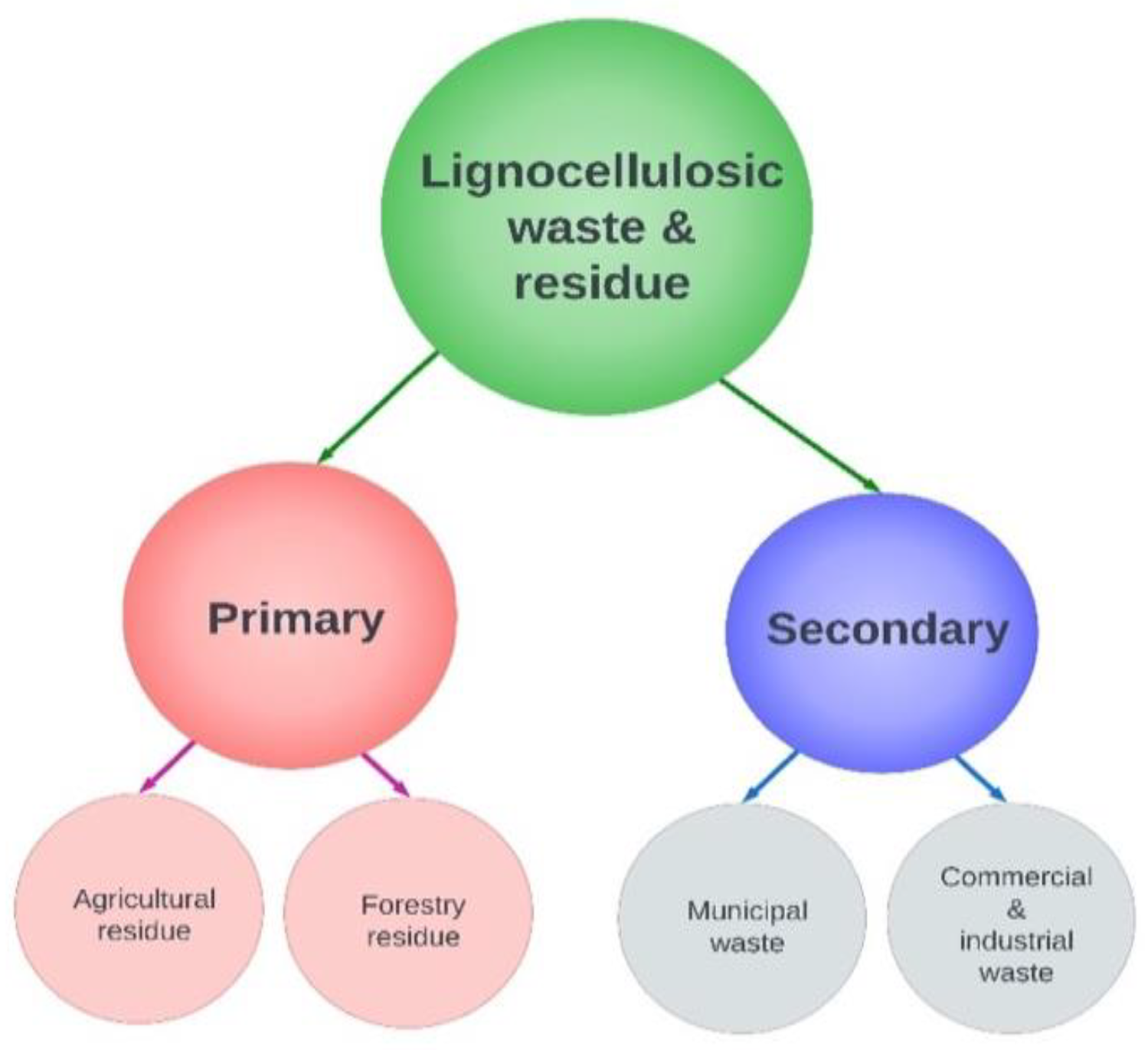

2.1. LCW&R Streams in the UK

2.1.1. Primary Agriculture Residues

| Wheat straw | Barley straw | Oat straw | Oilseed rape straw | |

| Animal bedding | Wheat straw→ Animal bedding (F1) | Barley straw→ Animal bedding (F6) | Oat straw→ Animal bedding (F9) | — |

| Animal feed | Wheat straw→ Animal feed (F2) | Barley straw→ Animal feed (F7) | Oat straw→ Animal feed (F10) | — |

| Heat & power | Wheat straw→ Heat & power (F3) | — | — | Oilseed rape straw→Heat & power (F12) |

| Mushroom and carrot production | Wheat straw→ Mushroom and carrot production (F4) | — | — | — |

| Soil incorporation | Wheat straw→ Soil incorporation (F5) | Barley straw→ Soil incorporation (F8) | Oat straw→ Soil incorporation (F11) | Oilseed rape straw→Soil incorporation (F13) |

2.1.2. Primary Forest Residues

| Conifers leftover | Broadleaves leftover | |

| Uncollected | Conifer leftover→ Uncollected (F14) | Broadleave leftover→ Uncollected (F16) |

| Heat & power | Conifer leftover→Heat & power (F15) | Broadleave leftover→Heat & power (F17) |

| Paper and cardboard waste | Wood waste | Organic waste | |

| Incineration with/out recovery | Paper and cardboard waste→ Incineration with/out recovery (F18) | Wood waste→ Incineration with/out recovery (F21) | Organic waste→Incineration with/out recovery (F25) |

| Recycling & reuse | Paper and cardboard waste→Recycling & reuse (F19) | Wood waste→Recycling & reuse (F22) | — |

| Backfilling | — | Wood waste→Backfilling (F23) | Organic waste→Backfilling (F26) |

| Landfilling | Paper and cardboard waste→Landfilling (F20) | Wood waste→Landfilling (F24) | Organic waste→Landfilling (F27) |

| Composting and anaerobic digestion | — | — | Organic waste→Composting and anaerobic digestion (F28) |

2.1.3. Secondary Municipal and Industrial Waste

2.2. LCW&R Streams Criteria Data Compilation

2.2.1. Objective Criteria Data

2.2.2. Subjective Criteria Data

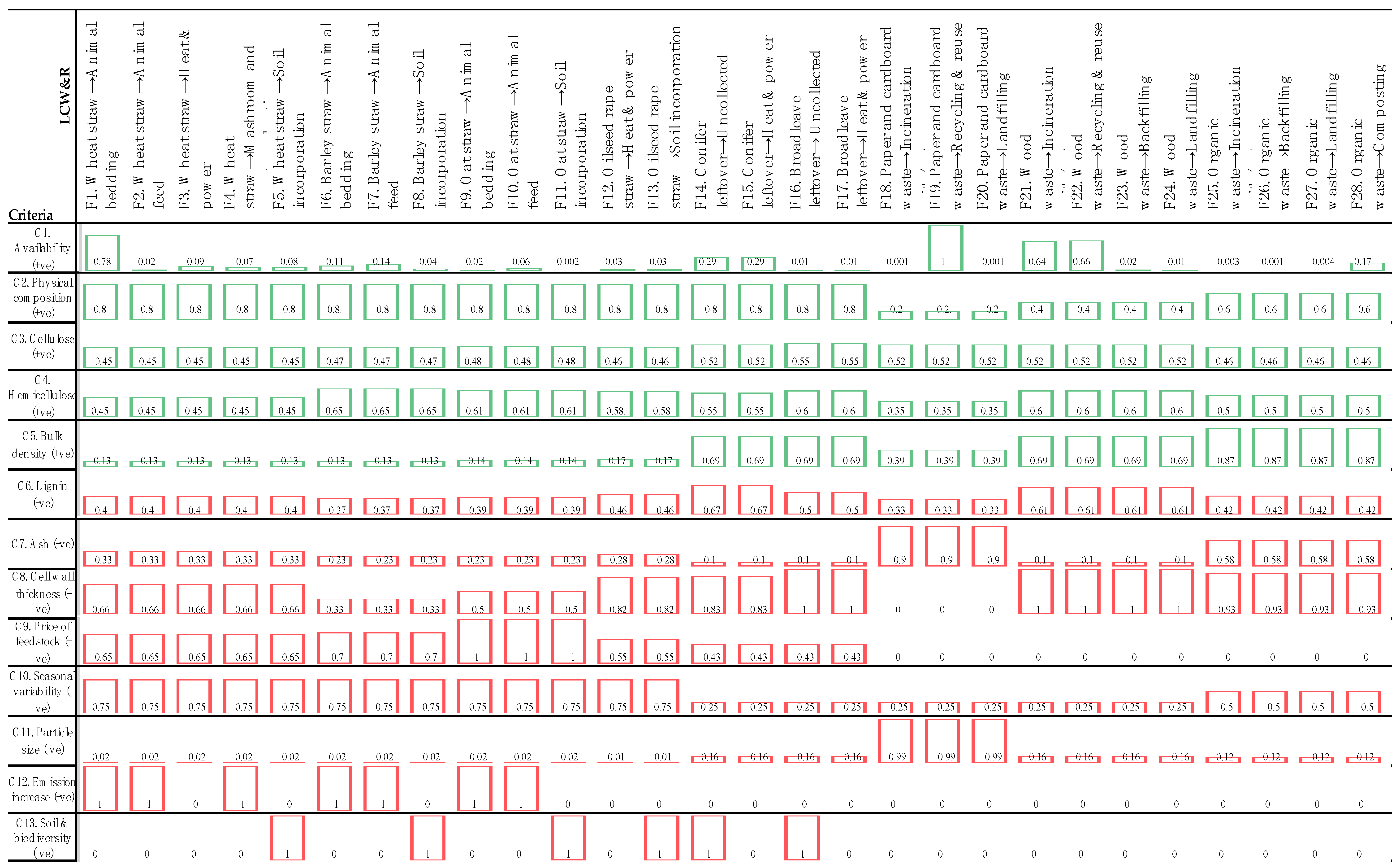

2.3. LCW&R Performance Matrix

| Subjective rating | Quantitative rating |

| Physical composition | |

| Raw & homogenous | 4 |

| Raw & mixed | 3 |

| Raw & mixed to processed & mixed | 2 |

| Processed & mixed | 1 |

| Seasonal variability | |

| High | 3 |

| Medium | 2 |

| Low | 1 |

| Environmental emission | |

| Increase | 1 |

| Decrease or unchanged | 0 |

| Soil and biodiversity impact | |

| Yes | 1 |

| No | 0 |

3. Results

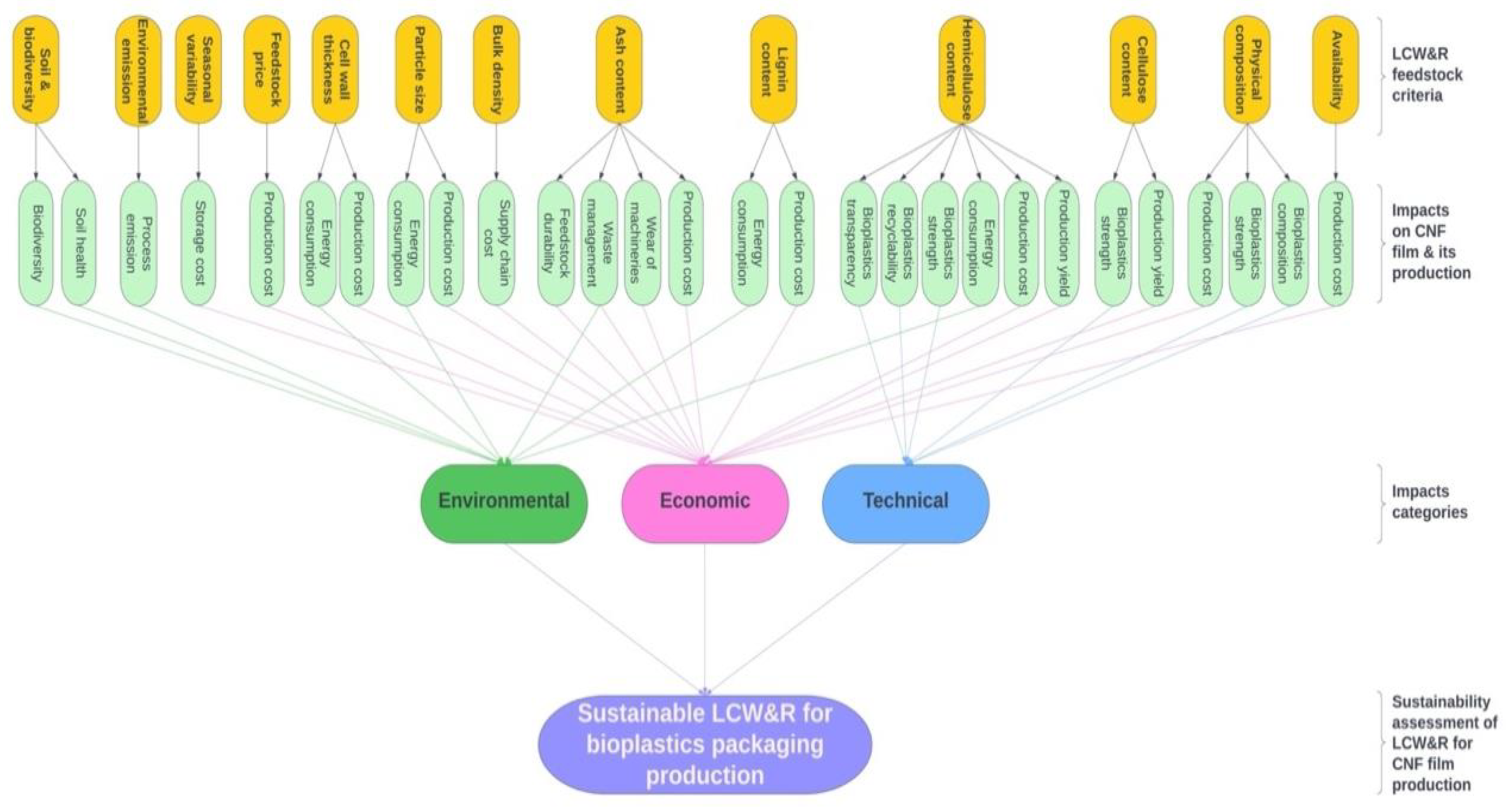

3.1. Sustainability Criteria

3.1.1. Availability (C1)

3.1.2. Physical Composition (C2)

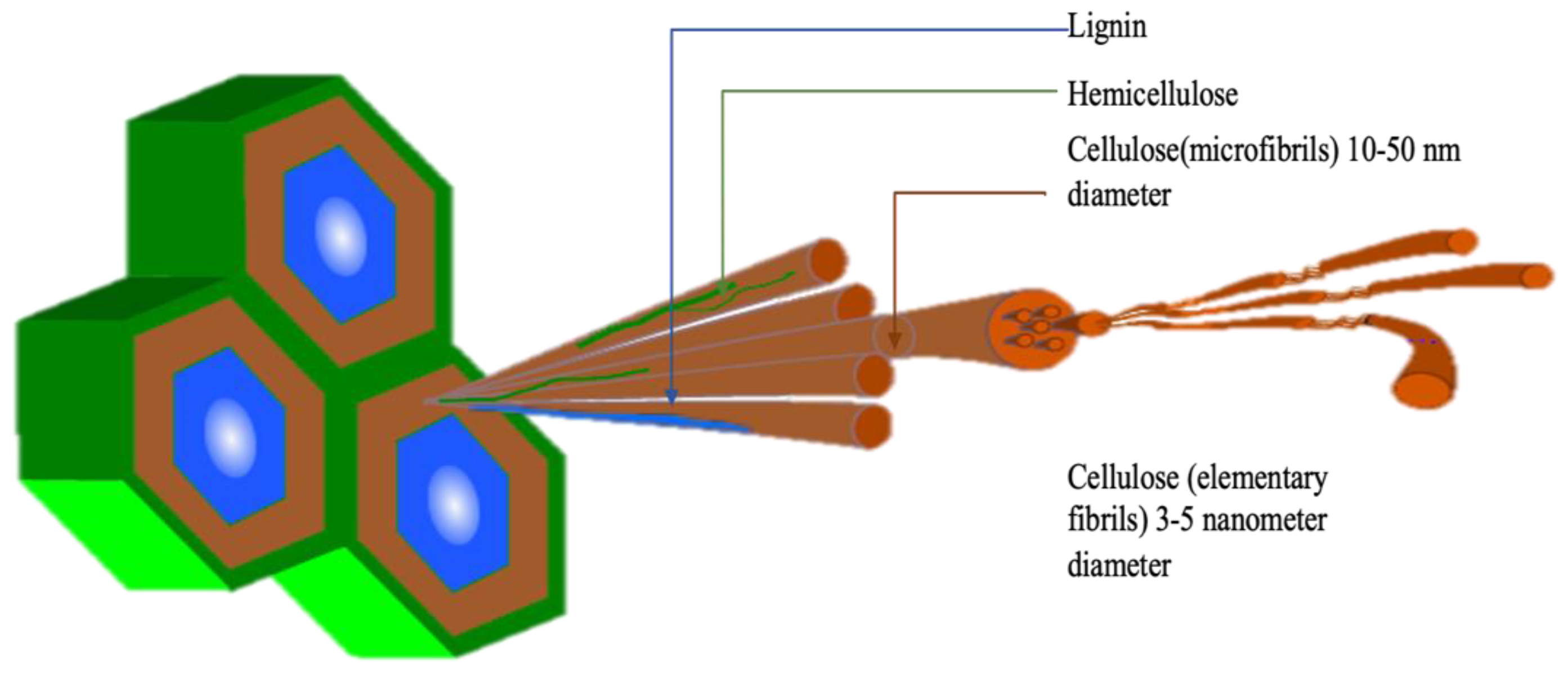

3.1.3. Cellulose (C3)

3.1.4. Hemicellulose (C4)

3.1.5. Bulk Density (C5)

3.1.6. Lignin (C6)

3.1.7. Ash (C7)

3.1.8. Particle Size (C8)

3.1.9. Cell Wall Thickness (C9)

3.1.10. Price (C10)

3.1.11. Seasonal Variability (C11)

3.1.12. Environmental Emission (C12)

3.1.13. Soil and Biodiversity Impact (C13)

3.2. LCW&R Performance Matrix

| Criteria | C1. Availability (dry tonnes) | C2. Physical composition (Subjective) |

C3. Cellulose (wt%) |

C4. Hemicellulose (wt%) |

C5. Bulk density (kg/m3) | |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| LCW&R | ||||||

| F1. Wheat straw→Animal bedding | 3073851.20 | Raw & homogenous | 33-40 [40] | 20-25 [40] | 36.22-39.74 [81] |

|

| F2. Wheat straw→Animal feed | 81534.52 | Raw & homogenous | 33-40 [40] | 20-25 [40] | 36.22-39.74 [81] |

|

| F3. Wheat straw→Heat & power | 364008.70 | Raw & homogenous | 33-40 [40] | 20-25 [40] | 36.22-39.74 [81] |

|

| F4. Wheat straw→Mashroom and carrot production | 278933.87 | Raw & homogenous | 33-40 [40] | 20-25 [40] | 36.22-39.74 [81] |

|

| F5. Wheat straw→Soil incorporation | 314048.90 | Raw & homogenous | 33-40 [40] | 20-25 [40] | 36.22-39.74 [81] |

|

| F6. Barley straw→Animal bedding | 433491.83 | Raw & homogenous | 31-45 [40] | 27-38 [40] |

33.89-38.61 [81] |

|

| F7. Barley straw→Animal feed | 542612.20 | Raw & homogenous | 31-45 [40] | 27-38 [40] |

33.89-38.61 [81] | |

| F8. Barley straw→Soil incorporation | 149533.75 | Raw & homogenous | 31-45 [40] | 27-38 [40] | 33.89-38.61 [81] |

|

| F9. Oat straw→Animal bedding | 61739.75 | Raw & homogenous | 31-48 [40] | 23-38 [40] |

38.61-41.69 [81] | |

| F10. Oat straw→Animal feed | 227798.37 | Raw & homogenous | 31-48 [40] | 23-38 [40] |

38.61-41.69 [81] | |

| F11. Oat straw→Soil incorporation | 6052.35 | Raw & homogenous | 31-48 [40] | 23-38 [40] | 38.61-41.69 [81] | |

| F12. Oilseed rape straw→Heat & power | 133469.86 | Raw & homogenous | 35-40 [40] | 27-31 [40] | 47.46-49.7 [81] | |

| F13. Oilseed rape straw→Soil incorporation | 106883.32 | Raw & homogenous | 35-40 [40] | 27-31 [40] | 47.46-49.7 [81] | |

| F14. Conifer leftover→Uncollected | 1156979 | Raw & homogenous | 35-45 [40] | 25-30 [40] | 128-267 [105] | |

| F15. Conifer leftover→Heat & power | 1156979 | Raw & homogenous | 35-45 [40] | 25-30 [40] | 128-267 [105] | |

| F16. Broadleave leftover→ Uncollected | 22231 | Raw & homogenous | 40-50 [40] | 25-35 [40] | 128-267 [105] | |

| F17. Broadleave leftover→Heat & power | 22231 | Raw & homogenous | 40-50 [40] | 25-35 [40] | 128-267 [105] | |

| F18. Paper and cardboard waste→Incineration with/out recovery | 3811.08 | Processed & mixed | 40-50 [107,108] | 0-35 [107,108] | 112 [109,110] | |

| F19. Paper and cardboard waste→Recycling & reuse | 3936954.05 | Processed & mixed | 40-50 [107,108] | 0-35 [107,108] | 112 [109,110] |

|

| F20. Paper and cardboard waste→Landfilling | 5062.33 | Processed & mixed | 40-50 [107,108] | 0-35 [107,108] | 112 [109,110] |

|

| F21. Wood waste→Incineration with/out recovery | 2536972.89 | Raw & homogeneous to processed & mixed | 40-50 [40] | 25-35 [40] | 128-267 [105] | |

| F22. Wood waste→Recycling & reuse | 2600381.03 | Raw & homogeneous to processed & mixed | 40-50 [40] | 25-35 [40] | 128-267 [105] | |

| F23. Wood waste→Backfilling | 88781.00 | Raw & homogeneous to processed & mixed | 40-50 [40] | 25-35 [40] | 128-267 [105] | |

| F24. Wood waste→Landfilling | 22185.97 | Raw & mixed to processed & mixed | 40-50 [40] | 25-35 [40] | 128-267 [105] | |

| F25. Organic waste→Incineration with/out recovery | 13246.16 | Raw & mixed | 25.7-55.4 [40,106] |

7.2-43 [40,106] | 200-300 [111] | |

| F26. Organic waste→Backfilling | 2058 | Raw & mixed | 25.7-55.4 [40,106] |

7.2-43 [40,106] | 200-300 [111] | |

| F27. Organic waste→Landfilling | 14452.29 | Raw & mixed | 25.7-55.4 [40,106] |

7.2-43 [40,106] | 200-300 [111] | |

| F28. Organic waste→Composting and anaerobic digestion | 682814.19 | Raw & mixed | 25.7-55.4 [40,106] |

7.2-43 [40,106] | 200-300 [111] | |

| Criteria | C6. Lignin (wt%) | C7. Ash (wt%) |

C8. Cell wall thickness (µm) |

C9. Price of feedstock (£/tonne) | C10. Seasonal variability (Subjective) |

C11. Particle size (mm) | C12. Environmental emission (Subjective) |

C13. Soil and biodiversity impact(Subjective) | |

| LCW&R | |||||||||

| F1. Wheat straw→Animal bedding | 15-21 [40] | 3-10 [40] | 3.96 [112] | 39-105 [113] | High | 4.22 (chopped) [81] | Increase | No | |

| F2. Wheat straw→Animal feed | 15-21 [40] | 3-10 [40] | 3.96 [112] | 39-105 [113] |

High | 4.22 (chopped) [81] | Increase | No | |

| F3. Wheat straw→Heat & power | 15-21 [40] | 3-10 [40] | 3.96 [112] | 39-105 [113] |

High | 4.22 (chopped) [81] | Decrease | No | |

| F4. Wheat straw→Mashroom and carrot production | 15-21 [40] | 3-10 [40] |

3.96 [112] |

39-105 [113] |

High | 4.22 (chopped) [81] | Increase | No | |

| F5. Wheat straw→Soil incorporation | 15-21 [40] | 3-10 [40] | 3.96 [112] |

39-105 [113] |

High | 4.22 (chopped) [81] | Unchanged | Yes | |

| F6. Barley straw→Animal bedding | 14-19 [40] | 2-7 [40] |

up to 2 [114] |

45-108 [113] |

High | 3.37 (chopped) [81] | Increase | No | |

| F7. Barley straw→Animal feed | 14-19 [40] | 2-7 [40] |

up to 2 [114] |

45-108 [113] |

High | 3.37 (chopped) [81] | Increase | No | |

| F8. Barley straw→Soil incorporation | 14-19 [40] | 2-7 [40] |

Up to 2 [114] |

45-108 [113] |

High | 3.37 (chopped) [81] | Unchanged | Yes | |

| F9. Oat straw→Animal bedding | 16-19 [40] | 2-7 [40] |

2-3.96 [115] |

50-170 [113] |

High | 4.15 (chopped) [81] | Increase | No | |

| F10. Oat straw→Animal feed | 16-19 [40] | 2-7 [40] |

2-3.96 [115] |

50-170 [113] |

High | 4.15 (chopped) [81] | Increase | No | |

| F11. Oat straw→Soil incorporation | 16-19 [40] | 2-7 [40] |

2-3.96 [115] |

50-170 [113] |

High | 4.15 (chopped) [81] | Unchanged | Yes | |

| F12. Oilseed rape straw→Heat & power | 18-23 [40] | 3-8 [40] |

4.91 [116] |

41-80 [113] |

High | 2.42 (chopped) [81] | Decrease | No | |

| F13. Oilseed rape straw→Soil incorporation | 18-23 [40] | 3-8 [40] | 4.91[116] | 41-80 [113] |

High | 2.42 (chopped) [81] | Unchanged | Yes | |

| F14. Conifer leftover→Uncollected | 25-35 [40] | 1-3 [40] | 2-8 [117] |

35-60 [55] | Low | 0-63 (chipped) [105] | Unchanged | Yes | |

| F15. Conifer leftover→Heat & power | 20-25 [40] |

1-3 [40] |

2-8 [117] |

35-60 [55] |

Low | 0-63 (chipped) [105] |

Decrease | No | |

| F16. Broadleave leftover→ Uncollected | 20-25 [40] |

1-3 [40] |

1-11 [118] |

35-60 [55] |

Low | 0-63 (chipped) [105] |

Unchanged | Yes | |

| F17. Broadleave leftover→Heat & power | 0-30 [107,108] |

1-3 [40] |

1-11 [118] |

35-60 [55] |

Low | 0-63 (chipped) [105] |

Decrease | No | |

| F18. Paper and cardboard waste→Incineration with/out recovery | 0-30 [107,108] |

0-35 [119,120] |

Not applicable | Negligible [40] | Low | 100-300 (baled) [109] | Decrease | No | |

| F19. Paper and cardboard waste→Recycling & reuse | 0-30 [107,108] |

0-35 [119,120] |

Not applicable | Negligible [40] | Low | 100-300 (baled) [109] | Unchanged | No | |

| F20. Paper and cardboard waste→Landfilling | 0-30 [107,108] |

0-35 [119,120] |

Not applicable | Negligible [40] | Low | 100-300 (baled) [109] | Decrease | No | |

| F21. Wood waste→Incineration with/out recovery | 20-35 [40] | 1.0-3.0 [40] | 1-11 [117,118] |

Negligible [40] | Low | 0-63 (chipped) [105] |

Decrease | No | |

| F22. Wood waste→Recycling & reuse | 20-35 [40] | 1.0-3.0 [40] | 1-11 [117,118] |

Negligible [40] | Low | 0-63 (chipped) [105] |

Unchanged | No | |

| F23. Wood waste→Backfilling | 20-35 [40] | 1.0-3.0 (Used same as forest residues) [40] | 1-11 [117,118] |

Negligible [40] | Low | 0-63 (chipped) [105] |

Unchanged | No | |

| F24. Wood waste→Landfilling | 3-35 [40] | 1.0-3.0 (Used same as forest residues) [40] | 1-11 [117,118] |

Negligible [40] | Low | 0-63 (chipped) (Gruduls et al., 2013) [105] |

Decrease | No | |

| F25. Organic waste→Incineration with/out recovery | 3-35 [40] | 2.5-20 [121,122] |

0.1-11 [123] |

Negligible [40] | Medium to High | 10-40 (shredded) [111] | Decrease | No | |

| F26. Organic waste→Backfilling | 25-35 [40] |

2.5-20 [121,122] |

0.1-11 [123] |

Negligible [40] | Medium to High | 10-40 (shredded) [111] | Unchanged | No | |

| F27. Organic waste→Landfilling | 3-35 [40] | 2.5-20 [121,122] |

0.1-11 [123] |

Negligible [40] | Medium to High | 10-40 (shredded) [111] | Decrease | No | |

| F28. Organic waste→Composting and anaerobic digestion | 3-35 [40] | 2.5-20 [121,122] |

0.1-11 [123] |

Negligible [40] | Medium to High | 10-40 (shredded) [111] | Unchanged | No | |

4. Discussion

5. Conclusions

Author Contributions

Funding

Conflicts of Interest

References

- Assessment of Agricultural Plastics and their Sustainability-A Call for Action. (Accessed 7 January 2022). Available online: https://www.fao.org/3/cb7856en/cb7856en.pdf.

- Plastic Market Size, Share & Trends Report, 2022 - 2030. (Accessed 12 December 2022). Available online: https://www.grandviewresearch.com/industry-analysis/global-plastics-market.

- Plastics in the Bioeconomy (Issue 2). (Accessed 26 January 2022). Available online: https://cdn.ricardo.com/ee/media/downloads/ed12430-bb-net-report-final-issue-2.pdf.

- Plastic leakage and greenhouse gas emissions are increasing. (Accessed 26 January 2022). Available online: https://www.oecd.org/environment/plastics/increased-plastic-leakage-and-greenhouse-gas-emissions.htm.

- Barboza, L.G.A.; Cózar, A.; Gimenez, B.C.G.; Barros, T.L.; Kershaw, P.J.; Guilhermino, L. Macroplastics Pollution in the Marine Environment. In World Seas: An Environmental Evaluation Volume III: Ecological Issues and Environmental Impacts, 2nd ed.; Sheppard, C., Ed.; Academic press: Massachusetts, United States, 2019; Volume 3, pp. 305–328. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Peng, L.; Fu, D.; Qi, H.; Lan, C.Q.; Yu, H.; Ge, C. Micro- and nano-plastics in marine environment: Source, distribution and threats — A review. Science of The Total Environment 2020, 698, 134254. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Zhao, X.; Wang, Y.; Chen, X.; Yu, X.; Li, W.; Zhang, S.; Meng, X.; Zhao, Z., M.; Dong, T.; Anderson, A.; Aiyedun, A.; Li, Y.; Webb, E.; Wu, Z.; Kunc, V.; Ragauskas, A.; Ozcan, S.; Zhu, H. Sustainable bioplastics derived from renewable natural resources for food packaging. Matter 2023, 6, 97–127. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Lavrič, G.; Oberlintner, A.; Filipova, I.; Novak, U.; Likozar, B.; Vrabič-Brodnjak, U. Functional nanocellulose, alginate and chitosan nanocomposites designed as active film packaging materials. Polymers 2021, 13, 2523. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Bioplastics market data. (Accessed 26 January 2022). Available online: https://www.european-bioplastics.org/market/.

- Brizga, J.; Hubacek, K.; Feng, K. The unintended side effects of bioplastics: Carbon, land, and water footprints. One Earth 2020, 3, 45–53. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Raj, T.; Chandrasekhar, K.; Naresh Kumar, A.; Kim, S.H. Lignocellulosic biomass as renewable feedstock for biodegradable and recyclable plastics production: A sustainable approach. Renewable and Sustainable Energy Reviews 2022, 158, 112130. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- The nexus of biofuels, climate change, and human health. (Accessed 20 February 2022). [CrossRef]

- Bishop, G.; Styles, D.; Lens, P.N.L. Environmental performance of bioplastic packaging on fresh food produce: A consequential life cycle assessment. Journal of Cleaner Production 2021, 317. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Garrido, F.J.O.; Piston, F.; Gomez, L.D.; Mcqueen-Mason, S.J. Biomass recalcitrance in barley, wheat and triticale straw: Correlation of biomass quality with classic agronomical traits. PLoS ONE 2018, 13, e0205880–e0205880. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Abe, M.M.; Martins, J.R.; Sanvezzo, P.B.; Macedo, J.V.; Branciforti, M.C.; Halley, P.; Botaro, V.R.; Brienzo, M. Advantages and disadvantages of bioplastics production from starch and lignocellulosic components. Polymers 2021, 13. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Davis, G.; Song, J.H. Biodegradable packaging based on raw materials from crops and their impact on waste management. Industrial Crops and Products 2006, 23, 147–161. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Rojas, J.; Bedoya, M.; Ciro, Y. Current trends in the production of cellulose nanoparticles and nanocomposites for biomedical applications. In Cellulose - Fundamental Aspects and Current Trends; Poletto, M., Ed.; IntechOpen: London, United Kingdom, 2015. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Petroudy, S.D. Physical and mechanical properties of natural fibers. In Advanced High Strength Natural Fibre Composites in Construction; Fan, M., Fu, F., Eds.; Woodhead Publishing: Cambridge, United Kingdom, 2017; pp. 59–83. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Arola, S.; Malho, J.M.; Laaksonen, P.; Lille, M.; Linder, M.B. The role of hemicellulose in nano fibrillated cellulose networks. Soft Matter 2013, 9, 1319–1326. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Lavoine, N.; Desloges, I.; Dufresne, A.; Bras, J. Microfibrillated cellulose - Its barrier properties and applications in cellulosic materials: A review. Carbohydrate Polymers 2012, 90, 735–764. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Khalil, H.P.S.; Davoudpour, Y.; Saurabh, C.K.; Hossain, M.S.; Adnan, A.S.; Dungani, R.; Paridah, M.T.; Sarker, M., Z.; Fazita, M., R.; Syakir, M.I.; Haafiz, M.K.M. A review on nanocellulosic fibres as new material for sustainable packaging: Process and applications. Renewable and Sustainable Energy Reviews 2016, 64, 823–836. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Rajinipriya, M.; Nagalakshmaiah, M.; Robert, M.; Elkoun, S. Importance of agricultural and industrial waste in the field of nanocellulose and recent industrial developments of wood based nanocellulose: a review. ACS Publications 2018, 6, 2807–2828. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Shanmugam, K.; Doosthosseini, H.; Varanasi, S.; Garnier, G.; Batchelor, W. Nanocellulose films as air and water vapour barriers: A recyclable and biodegradable alternative to polyolefin packaging. Sustainable Materials and Technologies 2019, 22, e00115. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Kontturi, K.S.; Lee, K.Y.; Jones, M.P.; Sampson, W.W.; Bismarck, A.; Kontturi, E. Influence of biological origin on the tensile properties of cellulose nanopapers. Cellulose 2021, 28, 6619–6628. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Azeredo, H.M.C.; Rosa, M.F.; Mattoso, L.H.C. Nanocellulose in bio-based food packaging applications. Industrial Crops and Products 2017, 97, 664–671. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Kalia, S.; Boufi, S.; Celli, A.; Kango, S. Nanofibrillated cellulose: Surface modification and potential applications. Colloid and Polymer Science 2014, 292, 5–31. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Gómez, H., C.; Serpa, A.; Velásquez-Cock, J.; Gañán, P.; Castro, C.; Vélez, L.; Zuluaga, R. Vegetable nanocellulose in food science: A review. Food Hydrocolloids 2016, 57, 178–186. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Nechyporchuk, O.; Belgacem, M.N.; Bras, J. Production of cellulose nanofibrils: A review of recent advances. Industrial Crops and Products 2016, 93, 2–25. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Ang, S.; Ghosh, D.; Haritos, V.; Batchelor, W. Recycling cellulose nanofibers from wood pulps provides drainage improvements for high strength sheets in papermaking. Journal of Cleaner Production 2021, 312. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Vikman, M.; Vartiainen, J.; Tsitko, I.; Korhonen, P. Biodegradability and Compostability of Nanofibrillar Cellulose-Based Products. Journal of Polymers and the Environment 2015, 23, 206–215. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Statista. Flexible packaging global production volume 2017-2022. Available online: https://www.statista.com/statistics/719097/production-volume-of-the-global-flexible-packaging-industry/.

- Stark, N.M. . Opportunities for Cellulose Nanomaterials in Packaging Films: A Review and Future Trends. Journal of Renewable Materials 2016, 4, 313. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Bishop, G.; Styles, D.; Lens, P.N.L. Land-use change and valorisation of feedstock side-streams determine the climate mitigation potential of bioplastics. Resources, Conservation and Recycling 2022, 180. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Bussemaker, M.J.; Day, K.; Drage, G.; Cecelja, F. Supply chain optimisation for an ultrasound-organosolv lignocellulosic biorefinery: impact of technology choices. Waste and Biomass Valorization 2017, 8, 2247–2261. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Tonini, D.; Hamelin, L.; Astrup, T.F. Environmental implications of the use of agro-industrial residues for biorefineries: application of a deterministic model for indirect land-use changes. GCB Bioenergy 2016, 8, 690–706. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Badgujar, K.C.; Bhanage, B.M. Dedicated and waste feedstocks for biorefinery: An approach to develop a sustainable society. In Waste Biorefinery: Potential and Perspectives; Bhaskar, T., Pandey, A., Mohan, S.V., Lee, D.J., Khanal, S.K., Eds.; Elsevier: Amsterdam, Netherlands, 2018; pp. 3–38. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Piemonte, V.; Gironi, F. Land-use change emissions: How green are the bioplastics? Environmental Progress & Sustainable Energy 2011, 30, 685–691. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Jonoobi, M.; Mathew, A.P.; Oksman, K. Natural resources and residues for production of bionanomaterials. In Handbook of Green Materials: 1 Bionanomaterials: separation processes, characterization and properties; Oksman, K., Mathew, A.P., Bismarck, A., Rojas, O., Sain, M., Eds.; World Scientific: Singapore, 2014. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- United Kingdom Roadmap for lignocellulosic biomass and relevant policies for a bio-based economy in 2030. (Accessed 4 January 2022). Available online: https://www.s2biom.eu/images/Publications/WP8_Country_Outlook/Final_Roadmaps_March/S2Biom-UNITED-KINGDOM-biomass-potential-and-policies.pdf.

- Lignocellulosic feedstock in the, UK. Available online:. (Accessed 4 January 2022). Available online: https://www.nnfcc.co.uk/files/mydocs/LBNet%20Lignocellulosic%20feedstockin%20the%20UK_Nov%202014.pdf.

- Availability of cellulosic residues and wastes in the eu - international council on clean transportation. (Accessed 16 July 2022). Available online: https://www.theicct.org/publications/availability-cellulosic-residues-and-wastes-eu.

- Balea, A.; Fuente, E.; Tarrés, Q.; Pèlach, M.À.; Mutjé, P.; Delgado-Aguilar, M.; Blanco, A.; Negro, C. Influence of pretreatment and mechanical nanofibrillation energy on properties of nanofibers from Aspen cellulose. Cellulose 2021, 28, 9187–9206. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Bosworth, S.C. Perennial grass biomass production and utilization. In Bioenergy: Biomass to Biofuels and Waste to Energy; Dahiya, A., Ed.; Academic press: Massachusetts, United States, 2020; pp. 89–105. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Malucelli, L.C.; Lacerda, L.G.; Dziedzic, M.; da Silva Carvalho Filho, M.A. Preparation, properties and future perspectives of nanocrystals from agro-industrial residues: a review of recent research. Reviews in Environmental Science and Biotechnology 2017, 16, 131–145. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Bian, H. ; Yang, Y.; Tu, P.; Bian, H.; Yang, Y.; Tu, P.; Chen, J.Y. Value-added utilization of wheat straw: from cellulose and cellulose nanofiber to all-cellulose nanocomposite film. Membranes 2022, 12, 475. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Stelte, W.; Sanadi, A.R. Preparation and characterization of cellulose nanofibers from two commercial hardwood and softwood pulps. Industrial and Engineering Chemistry Research 2009, 48, 11211–11219. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Woiciechowski, A.L.; José, C.; Neto, D.; Porto De Souza Vandenberghe, L.; De Carvalho Neto, P.; Novak Sydney, A.C.; Letti, A.J.; Karp, S.G.; Alberto, L.; Torres, Z.; Soccol, C.R. Lignocellulosic biomass: Acid and alkaline pretreatments and their effects on biomass recalcitrance-Conventional processing and recent advances. Bioresource technology 2020, 304, 122848. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Blanco, A.; Monte, M.C.; Campano, C.; Balea, A.; Merayo, N.; Negro, C. Nanocellulose for Industrial Use: Cellulose Nanofibers (CNF), Cellulose Nanocrystals (CNC), and Bacterial Cellulose (BC). In Handbook of Nanomaterials for Industrial Applications; Hussain, C.M., Ed.; Elsevier: Amsterdam, Netherlands, 2018; pp. 74–126. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Chaker, A.; Alila, S.; Mutjé, P.; Vilar, M.R.; Boufi, S. Key role of the hemicellulose content and the cell morphology on the nanofibrillation effectiveness of cellulose pulps. Cellulose 2013, 20, 2863–2875. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Iwamoto, S.; Abe, K.; Yano, H. The effect of hemicelluloses on wood pulp nano fibrillation and nanofiber network characteristics. Biomacromolecules 2008, 9, 1022–1026. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Khalil, H.P.S.; Adnan, A.S.; Yahya, E.B.; Olaiya, N.G.; Safrida, S.; Hossain, M.S.; Balakrishnan, V.; Gopakumar, D.A.; Abdullah, C.K.; Oyekanmi, A.A.; Pasquini, D. A review on plant cellulose nanofibre-based aerogels for biomedical applications. Polymers 2020, 12, 1759. Available online: https://www.mdpi.com/790598. [CrossRef]

- Pre-treatments to enhance the enzymatic saccharification of lignocellulose: technological and economic aspects. (Accessed 14 May 2022). Available online: https://www.bbnet-nibb.co.uk/resource/pre-treatments-to-enhance-the-enzymatic-saccharification-of-lignocellulose-technological-and-economic-aspects/.

- van Dyken, S.; Bakken, B.H.; Skjelbred, H.I. Linear mixed-integer models for biomass supply chains with transport, storage and processing. Energy 2010, 35, 1338–1350. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Agrocycle factsheet: Straw production and value chains. (Accessed 4 June 2022). Available online: https://www.nnfcc.co.uk/files/mydocs/Straw%20factsheet.pdf.

- Use of sustainably sourced residue and waste streams for advanced biofuel production in the European Union: rural economic impacts and potential for job creation. Available online: https://www.nnfcc.co.uk/files/mydocs/14_2_18%20%20ECF%20Advanced%20Biofuels_NNFCC%20published%20v2.pdf(Accessed 23 March 2022). Understanding waste streams: Treatment of specific waste. Available online: https://www.europarl.europa.eu/EPRS/EPRSBriefing- 564398-Understanding-waste-streams-FINAL.pdf(Accessed 2 February 2022). Straw prices soar, piling pressure on northern European livestock farmers. Available online: https://www.euractiv.com/section/ agriculture-food/news/straw-prices-soar-piling-pressure-on-northern-europe-livestock-farmers/(Accessed 15 April 2022).

- Titus, B.D.; Brown, K.; Helmisaari, H.S.; Vanguelova, E.; Stupak, I.; Evans, A.; Clarke, N.; Guidi, C.; Bruckman, V.J.; Varnagiryte-Kabasinskiene, I.; Armolaitis, K.; de Vries, W.; Hirai, K.; Kaarakka, L.; Hogg, K.; Reece, P. Sustainable forest biomass: a review of current residue harvesting guidelines. Energy, Sustainability and Society 2021, 11, 1–32. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Guidance on classification of waste according to EWC-Stat categories- Supplement to the Manual for the Implementation of the Regulation (EC) No 2150/2002 on Waste Statistics. (Accessed 25 March 2022). Available online: https://ec.europa.eu/eurostat/documents/342366/351806/Guidance-on-EWCStat-categories-2010.pdf/0e7cd3fc-c05c-47a7-818f-1c2421e55604.

- UK statistics on waste - GOV.UK. Office for National Statistics. (Accessed September 1, 2022). Available online: https://www.gov.uk/government/statistics/uk-waste-data.

- Agriculture in the United Kingdom data sets. (Accessed September 3, 2022). Available online: https://www.gov.uk/government/statistical-data-sets/agriculture-in-the-united-kingdom.

- The main components of yield in wheat. (Accessed December 17, 2022). Available online: https://ahdb.org.uk/knowledge-library/the-main-components-of-yield-in-wheat.

- The main components of yield in barley. (Accessed December 17, 2022). Available online: https://ahdb.org.uk/knowledge-library/the-main-components-of-yield-in-barley.

- Oat growth guide: An output from optimising growth to maximise yield and quality. (December 17, 2022). Available online: https://www.hutton.ac.uk/sites/default/files/files/publications/Oat-Growth-Guide.pdf.

- Plant biomass: miscanthus, short rotation coppice and straw. (Accessed August 7, 2022). Available online: https://www.gov.uk/government/statistics/area-of-crops-grown-for-bioenergy-in-england-and-the-uk-2008-2020/section-2-plant-biomass-miscanthus-short-rotation-coppice-and-straw.

- Straw and Forage Study. (Accessed August 5, 2022). Available online: https://www.gov.scot/binaries/content/documents/govscot/publications/factsheet/2018/04/straw-and-forage-study-sruc-research-report/documents/straw-forage-study-sruc-report-2017-2018-pdf/straw-forage-study-sruc-report-2017-2018-pdf/govscot%3Adocument/Straw%2Band%2Bforage%2Bstudy%2B-%2BSRUC%2Breport%2B2017-2018.pdf.

- 25-year forecast of softwood timber availability. (Accessed January 30, 2022). Available online: https://www.forestresearch.gov.uk/publications/25-year-forecast-of-softwood-timber-availability/.

- Forestry Statistics 2018 - Forest Research. (Accessed January 30, 2022). Available online: https://www.forestresearch.gov.uk/tools-and-resources/statistics/forestry-statistics/forestry-statistics-2021/.

- Compost Moisture content. (November 20, 2022). Available online: http://www.carryoncomposting.com/416920216.

- Arena, U.; di Gregorio, F. A waste management planning based on substance flow analysis. Resources, Conservation and Recycling 2014, 85, 54–66. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Owen, E.; Jayasuriyat, C.N. Use of crop residues as animal feeds in developing countries. Research and development in agriculture 1989, 6, 129–138. [Google Scholar]

- Islam, S.; Ponnambalam, S.G.; Lam, H.L. A novel framework for analysing the green value of food supply chain based on life cycle assessment. Clean Technologies and Environmental Policy 2017, 19, 93–103. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Olinto, A.C. , & Islam, S. Optimal aggregate sustainability assessment of total and selected factors of industrial processes. Clean Technologies and Environmental Policy 2017, 19, 1791–1797. [Google Scholar]

- Hughes, S.R.; Qureshi, N. Biomass for biorefining: resources, allocation, utilization, and policies. In Biorefineries: Integrated Biochemical Processes for Liquid Biofuels; Qureshi, N., Hodge, D.B., Vertès, A.A., Eds.; Elsevier: Amsterdam, Netherlands, 2014; pp. 37–58. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Bhatia, S.K.; Otari, S.V.; Jeon, J.M.; Gurav, R.; Choi, Y.K.; Bhatia, R.K.; Pugazhendhi, A.; Kumar, V.; Rajesh Banu, J.; Yoon, J.J.; Choi, K.Y.; Yang, Y.H. Biowaste-to-bioplastic (polyhydroxyalkanoates): Conversion technologies, strategies, challenges, and perspective. Bioresource Technology 2021, 326, 124733. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Is Resource Availability Slowing you Down ? Available online:. (Accessed February 5, 2022). Available online: https://www.google.com/search?q=Is+Resource+Availability+Slowing+you+Down%3F&rlz=1C1GCEU_enGB842GB842&oq=Is+Resource+Availability+Slowing+you+Down%3F&aqs=chrome..69i57j69i60.1250j0j4&sourceid=chrome&ie=UTF-8.

- Abdel-Shafy, H.I.; Mansour, M.S.M. Solid waste issue: Sources, composition, disposal, recycling, and valorization. Egyptian Journal of Petroleum 2018, 27, 1275–1290. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- The Effect of Age and Recycling on Paper Quality. (Accessed February 5, 2022). Available online: https://scholarworks.wmich.edu/cgi/viewcontent.cgi?article=5957&context=masters_theses.

- Awoyale, A.A.; Lokhat, D.; Okete, P. Investigation of the effects of pretreatment on the elemental composition of ash derived from selected Nigerian lignocellulosic biomass. Scientific Reports 2021, 11, 21313. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Di Pretoro, A.; Montastruc, L.; Manenti, F.; Joulia, X. Flexibility assessment of a biorefinery distillation train: Optimal design under uncertain conditions. Computers and Chemical Engineering 2020, 138. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Tumuluru, J.S.; Tabil, L.G.; Song, Y.; Iroba, K.L.; Meda, V. Grinding energy and physical properties of chopped and hammer-milled barley, wheat, oat, and canola straws. Biomass and Bioenergy 2014, 60, 58–67. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Food contact materials authorisation guidance. (Accessed December 15, 2022). Available online: https://www.food.gov.uk/business-guidance/regulated-products/food-contact-materials-guidance.

- Abdel-Hamid, A.M.; Solbiati, J.O.; Cann, I.K.O. Insights into lignin degradation and its potential industrial applications. Advances in Applied Microbiology 2013, 82, 1–28. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Klemm, D.; Heublein, B.; Fink, H.P.; Bohn, A.; Klemm, D.; Fink, H.-P. Cellulose: fascinating biopolymer and sustainable raw material. Wiley Online Library 2005, 44, 3358–3393. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Abara Mangasha, L. Review on Effect of Some Selected Wood Properties on Pulp and Paper Properties. Journal of Forestry and Environment 2019, 1, 16–22. [Google Scholar]

- Anupam, K.; Lal, P.S.; Bist, V.; Sharma, A.K.; Swaroop, V. Raw material selection for pulping and papermaking using TOPSIS multiple criteria decision-making design. Environmental Progress & Sustainable Energy 2014, 33, 1034–1041. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Zhang, Q.; Zhang, P.; Pei, Z.J.; Wang, D. Relationships between cellulosic biomass particle size and enzymatic hydrolysis sugar yield: Analysis of inconsistent reports in the literature. Renewable Energy 2013, 60, 127–136. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Scheller, H.V.; Ulvskov, P. Hemicelluloses. Annual Review of Plant Biology 2010, 61, 263–289. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Tenhunen, T.M.; Peresin, M.S.; Penttilä, P.A.; Pere, J.; Serimaa, R.; Tammelin, T. Significance of xylan on the stability and water interactions of cellulosic nanofibrils. Reactive and Functional Polymers 2014, 85, 157–166. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Kumar, A.; Sokhansanj, S.; Flynn, P.C. Development of a multicriteria assessment model for ranking biomass feedstock collection and transportation systems. Applied Biochemistry and Biotechnology 2006, 129, 71–87. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Bulk Density Impacts on the Supply Chain. (Accessed December 15, 2022). Available online: https://generainc.com/bulk-density-impacts-on-the-supply-chain/.

- Sannigrahi, P.; Pu, Y.; Ragauskas, A. Cellulosic biorefineries-unleashing lignin opportunities. Current opinion in environmental sustainability 2010, 2, 383–393. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Ogden, C.A.; Ileleji, K.E.; Johnson, K.D. Fuel property changes of switchgrass during one-year of outdoor storage. Biomass and Bioenergy 2019, 120, 359–366. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Pennells, J.; Godwin, I.D.; Amiralian, N.; Martin, D.J. Trends in the production of cellulose nanofibers from non-wood sources. Cellulose 2020, 27, 575–593. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- James, A.K.; Thring, R.W.; Helle, S.; Ghuman, H.S. Ash Management Review—Applications of Biomass Bottom Ash. Energies 2012, 5, 3856–3873. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Gharpuray, M.M.; Lee, Y.H.; Fan, L.T. Structural modification of lignocellulosics by pretreatments to enhance enzymatic hydrolysis. Biotechnology and Bioengineering 1983, 25, 157–172. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Cheng, Z.; Leal, J.H.; Hartford, C.E.; Carson, J.W.; Donohoe, B.S.; Craig, D.A.; Xia, Y.; Daniel, R.C.; Ajayi, O.O.; Semelsberger, T.A. Flow behavior characterization of biomass Feedstocks. Powder Technology 2021, 387, 156–180. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Richard Hess, J.; Wright, C.T.; Kenney, K.L. Cellulosic biomass feedstocks and logistics for ethanol production. Biofuels, Bioproducts and Biorefining 2007, 1, 181–190. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Uniform-Format Solid Feedstock Supply System: A Commodity-Scale Design to Produce an Infrastructure-Compatible Bulk Solid from Lignocellulosic Biomass-Executive Summary. (Accessed April 3, 2022). Available online: https://inldigitallibrary.inl.gov/sites/sti/sti/4408280.pdf.

- Rentizelas, A.A.; Tolis, A.J.; Tatsiopoulos, I.P. Logistics issues of biomass: The storage problem and the multi-biomass supply chain. Renewable and Sustainable Energy Reviews 2009, 13, 887–894. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Denafas, G.; Ruzgas, T.; Martuzevičius, D.; Shmarin, S.; Hoffmann, M.; Mykhaylenko, V.; Ogorodnik, S.; Romanov, M.; Neguliaeva, E.; Chusov, A.; Turkadze, T.; Bochoidze, I.; Ludwig, C. Seasonal variation of municipal solid waste generation and composition in four East European cities. Resources, Conservation and Recycling 2014, 89, 22–30. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- United Kingdom: Roadmap for lignocellulosic biomass and relevant policies for a bio-based economy in 2030. (Accessed October 20, 2022). Available online: https://www.s2biom.eu/images/Publications/WP8_Country_Outlook/Final_Roadmaps_March/S2Biom-UNITED-KINGDOM-biomass-potential-and-policies.pdf.

- Residue management consideration for this fall. (Accessed October 20, 2022). Available online: https://crops.extension.iastate.edu/blog/mahdi-al-kaisi/residue-management-consideration-fall.

- Stump Harvesting: Interim Guidance on Site Selection and Good Practice (Issue April). (Accessed October 22, 2022). Available online: https://cdn.forestresearch.gov.uk/2022/02/fc_stump_harvesting_guidance_april09.pdf.

- Gruduls, K.; Bardule, A.; Zalitis, T.; Lazdiņš, A. Characteristics of wood chips from loging residues and quality influencing factors. Research for rural development 2013, 2, 49–54. [Google Scholar]

- White, J.K. The application of LDAT to the HPM2 challenge. Proceedings of Institution of Civil Engineers: Waste and Resource Management 2008, 161, 137–146. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Byadgi, S.A.; Kalburgi, P.B. Production of bioethanol from waste newspaper. Procedia Environmental Sciences 2016, 35, 555–562. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Xu, H.; Huang, L.; Xu, M.; Qi, M.; Yi, T.; Mo, Q.; Zhao, H.; Huang, C.; Wang, S.; Liu, Y. Preparation and Properties of Cellulose-Based Films Regenerated from Waste Corrugated Cardboards Using [Amim]Cl/CaCl2. ACS Omega 2020, 5, 23743–23754. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Tanguay-Rioux, F. , Héroux, M., & Legros, R. Physical properties of recyclable materials and implications for resource recovery. Waste Management 2021, 136, 956–053. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Material bulk densities. (Accessed July 27, 2022). Available online: https://wrap.org.uk/resources/report/material-bulk-densities.

- Kristanto, G.A.; Zikrina, M.N. Analysis of the effect of waste’s particle size variations on biodrying method. AIP Conference Proceedings 2017, 1903, 040009. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Singh, S.; Dutt, D.; Tyagi, C.H. Complete characterization of wheat straw. BioResources 2011, 6, 154–177. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Hay and straw prices. (Accessed July 27, 2022). Available online: https://ahdb.org.uk/dairy/hay-and-straw-prices.

- Laborel-Préneron, A.; Magniont, C.; Aubert, J.E. Characterization of barley straw, hemp shiv and corn cob as resources for bioaggregate based building materials. Waste and Biomass Valorization 2018, 9, 1095–1112. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Kärkönen, A.; Korpinen, R.; Järvenpää, E.; Aalto, A.; Saranpää, P. Properties of oat and barley hulls and suitability for food packaging materials. Journal of natural fibers 2022, 19, 13326–13336. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Mazhari Mousavi, S.M.; Hosseini, S.Z.; Resalati, H.; Mahdavi, S.; Rasooly Garmaroody, E. Papermaking potential of rapeseed straw, a new agricultural-based fiber source. Journal of Cleaner Production 2013, 52, 420–424. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- The cell wall ultrastructure of wood fibres-effects of the chemical pulp fibre line. (Accessed October 22, 2022). Available online: https://www.diva-portal.org/smash/get/diva2:7109/FULLTEXT01.pdf.

- Effects of cell wall structure on tensile properties of hardwood. (Accessed October 22, 2022). Available online: https://www.diva-portal.org/smash/get/diva2:409533/FULLTEXT02.pdf.

- Ma, Y.; Hummel, M.; Määttänen, M.; Särkilahti, A.; Harlin, A.; Sixta, H. Upcycling of wastepaper and cardboard to textiles. Green Chemistry 2016, 18, 858–866. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Properties of paper. (Accessed October 7, 2022,). Available online: https://www.paperonweb.com/paperpro.htm.

- Ash Content of Grasses for Biofuel. (Accessed October 7, 2022). Available online: http://www.carborobot.com/Download/Papers/Bioenergy_Info_Sheet_5.pdf.

- Sadef, Y.; Javed, T.; Javed, R.; Mahmood, A.; Alwahibi, M.S.; Elshikh, M.S.; AbdelGawwa, M.R.; Alhaji, J.H.; Rasheed, R.A. Nutritional status, antioxidant activity and total phenolic content of different fruits and vegetables’ peels. PLoS ONE 2022, 17. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Plant Cell Wall. (Accessed October 7, 2022). Available online: https://www.botanicaldoctor.co.uk/learn-about-plants/cell-wall.

Disclaimer/Publisher’s Note: The statements, opinions and data contained in all publications are solely those of the individual author(s) and contributor(s) and not of MDPI and/or the editor(s). MDPI and/or the editor(s) disclaim responsibility for any injury to people or property resulting from any ideas, methods, instructions or products referred to in the content. |

© 2023 by the authors. Licensee MDPI, Basel, Switzerland. This article is an open access article distributed under the terms and conditions of the Creative Commons Attribution (CC BY) license (http://creativecommons.org/licenses/by/4.0/).