1. Introduction

Eco-labels play a crucial role in environmental policy and transformation by promoting sustainable production and consumption practices. Eco-labels aim to identify products that are proven to be environmentally preferable. They can increase consumer awareness about the environmental impacts of products and services, encouraging more informed and eco-friendly decision-making e.g., [

1,

2,

3].

There are various approaches to eco-labelling, and ISO standards distinguish three types of environmental labelling programs [

4,

5,

6] which aim at helping consumers to make informed choices and to encourage manufacturers to improve their environmental performance:

Type I: These are voluntary, multiple-criteria-based, third-party programs that grant licenses allowing the use of environmental labels on products. These labels indicate the overall environmental preferability of a product within a specific product category.

Type II: This type includes informative environmental claims based on self-declaration by the manufacturer.

Type III: These programs provide quantified environmental data about a product based on predetermined parameters set by a qualified third party. This data is typically based on a life cycle assessment and is verified by the original or another qualified third party.

The German eco-label “Blue Angel” is a key element of product-related environmental policy in Germany [

7]. As a Type I eco-label, the criteria for awarding the Blue Angel and the processes for developing these criteria adhere to the principles and procedures outlined in ISO 14024 for Type I labels. ISO 14024 sets forth the objective that Type I ecolabels must consider the entire life cycle of products when establishing award criteria. Any deviations from this requirement must be justified.

Consequently, it can be assumed that the assessment of product packaging or sales packaging is an implicit requirement of ISO 14024. “Sales packaging” means packaging conceived so as to constitute a sales unit consisting of products and packaging to the end user at the point of sale (definition according to [

8]). The terms product packaging and sales packaging are used synonymously in the following.

While the relevance of packaging and packaging waste in terms of environmental challenges such as waste generation, resource consumption and the emissions of plastics into the environment has been the subject of political and social debate for years, packaging-specific requirements have so far only been included in the award criteria for type 1 eco-labels in isolated cases; this applies to the Blue Angel as well as to other type 1 ecolabels such as the EU-Ecolabel or the Nordic Swan. This can be argued based on the often-subordinate relevance of packaging in relation to the product life cycle (see for example [

9]). However, as eco-labels are intended to represent a best-in-class award, it is reasonable to expect that the awarded products will also stand out from the market average in terms of the design of their sales packaging. Also, as stated by Otto et al. [

3], packaging information based on labelling schemes (“eco-labelling”) can potentially support consumers in their sustainable buying behaviour.

Against this background, this study

systematically examined which packaging-specific requirements can currently be found in the award criteria for the Blue Angel and

on this basis, proposals were made for requirements that could be integrated horizontally, i.e., across the variety of different products groups covered by the Blue Angel.

2. Approach

Potential award criteria for sales packaging have been examined, focusing on the extent to which horizontally integrable requirements can be established. The approach is organized according to the requirement areas of award criteria related to sales packaging which include

These criteria are commonly found in the award criteria for eco-labels related to non-energy-consuming products (see [

7,

10] as well as selected Blue Angel award criteria documents), as well as in guidelines and assessment approaches for the eco-design of packaging (e.g., [

11,

12,

13,

14,

15]). Also, these two dimensions are covered in the upcoming regulations of the EU Packaging and Packaging Waste Regulation (PPWR). In addition, the focus is on the two material groups most relevant for sales packaging [

16,

17]: plastics and paper / cardboard.

Following this, along the different areas of requirements of recycled content and material origin as well as recyclability, for the two material groups, the following steps are conducted:

A structured evaluation of the current award criteria for the Blue Angel as of October 2023, focusing on existing requirements for sales packaging.

A review of current and upcoming legal requirements for the key areas of concern.

An exploration of additional requirement areas, including relevant studies, guidelines, or standards/specifications as applicable.

An assessment of possible horizontal requirements within these areas.

Regarding point 1, the following section will provide an overview of the status of packaging-specific criteria in the Blue Angel award criteria. For point 2, the most relevant legal document currently is the German Packaging Act [

18]. The new EU Packaging and Packaging Waste Regulation [

8] is in the legislative process at the EU level and is set to replace the previous EU Packaging and Packaging Waste Directive (PPWD). Once the new EU packaging regulation comes into effect, it will provide the relevant legal framework. The status of the PPWR at the time of writing is that of March 15, 2024, following a trilogue between the EU Council, Parliament and Commission. Thus, the consideration of legal requirements focuses on the German Packaging Law (VerpackG) and the EU PPWR.

For point 3, in addition to examining the award criteria and legal requirements, other relevant studies, standards, and documents pertinent to the specific areas of requirement are included. This also involves an exploratory analysis of sales packaging available on the market in relation to these requirements.

Finally, for point 4, possible horizontal requirements are assessed. The first question which needs to be addressed is the extent to which packaging requirements should be used to differentiate products within the same product group or whether a (less ambitious) minimum environmental standard should be established. From a perspective, which considers insights from processes of developing various eco-labels, there is a stronger case for the latter approach. While the Blue Angel’s focus should remain on environmental differentiation between products, using packaging requirements to exclude otherwise environmentally advantageous products could be controversial, particularly from a consumer standpoint. Moreover, minimum requirements seem more suitable for horizontal integration of packaging requirements, while more ambitious requirements should ideally reflect the specific characteristics of each product group, if there are discernible environmental differences regarding packaging in the market.

With this context, the key questions, which are also reflected in the outlined process, are as follows:

What are the current and future legal (minimum) requirements?

Is there a “common” standard in existing eco-label award criteria?

What seems feasible from the perspective of manufacturers/applicants (based on an exploratory analysis of the market)?

These questions highlight the necessity for environmental minimum requirements. On one hand, such minimum standards should ensure defined baseline environmental performance of packaging in relation to various requirement areas. On the other hand, they should not overly burden manufacturers/applicants with packaging requirements. Depending on the specific area of requirements, it may be beneficial to establish varying levels of ambition.

It is important to note that there may be instances where even the established minimum criteria may not be achievable, requiring a tailored approach for specific product groups that diverges from the outlined requirements. Foreseeable cases where the application of horizontal requirements may not be feasible will be identified.

3. Current Situation of Packaging-Specific Requirements in Blue Angel Award Criteria

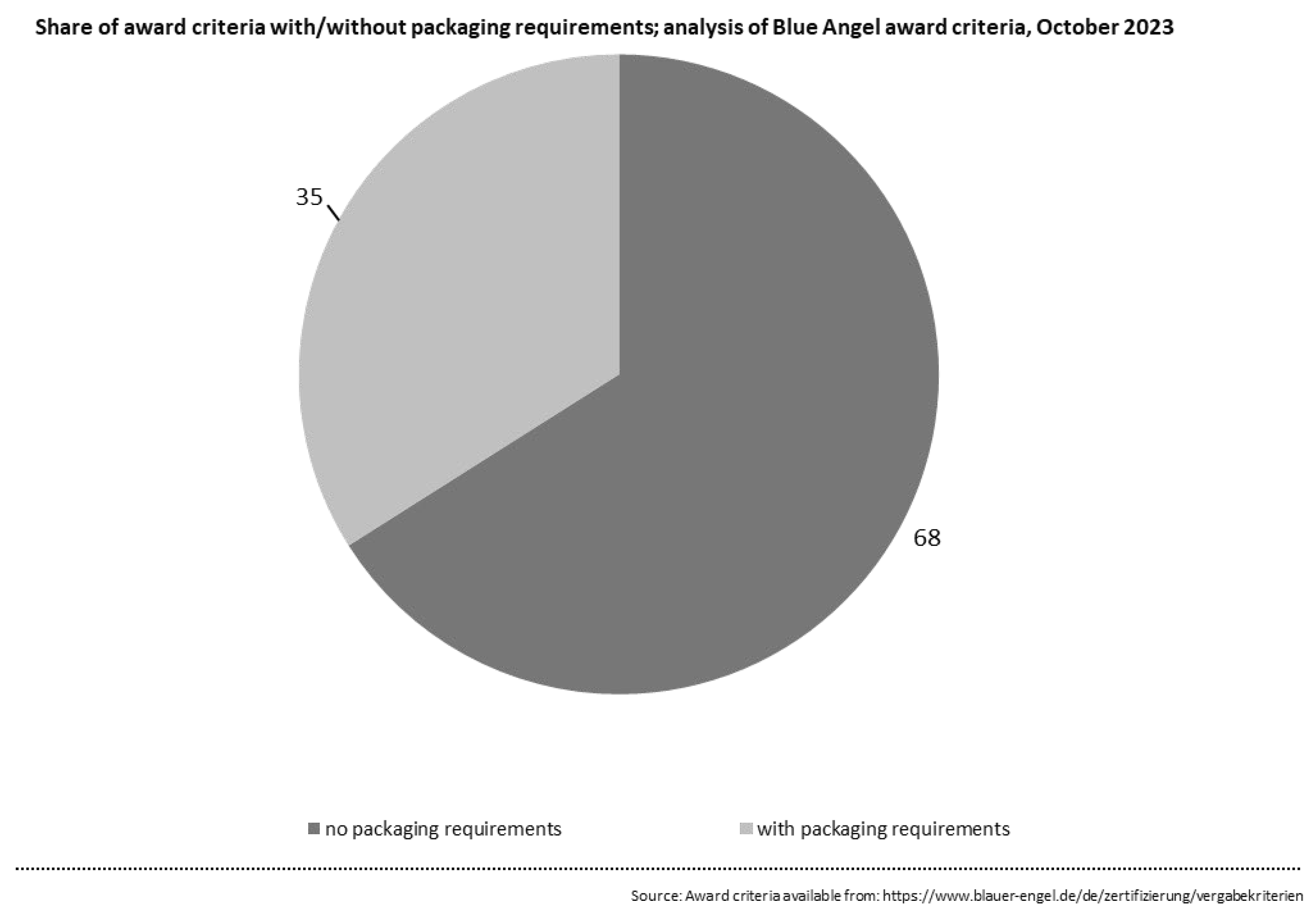

As of December 2023, there are Blue Angel award criteria for 103 product groups [

19]. These criteria were examined regarding the presence of requirements for the product or sales packaging; the results are shown in

Figure 1. Packaging requirements were identified in award criteria for 35 product groups.

In a first step, a quantitative evaluation of the packaging-related criteria of these 35 product-specific award criteria was carried out regarding the addressed requirement areas. The most frequently addressed area of requirements is the recycled content of the packaging materials. Corresponding requirements can be found in 26 of the 35 award criteria documents. The recyclability of the packaging is addressed in 14 award criteria documents. The absence of PVC or a ban on halogenated polymers can be found in 21 award criteria documents.

Other areas of requirements include requirements on the origin of materials, the ban on metallic coatings (in 9 award criteria), the outgassing of harmful substances (from the product, which the packaging must allow; found in 6 award criteria documents), the packaging weight/weight-benefit ratio (in 6 award criteria documents), or requirements concerning reusability (in 5 award criteria documents).

4. Recycled Content and Possible Horizontal Requirements

The recycled content is “the proportion, by mass, of recycled material in a product or packaging” [

5]. Requirements for the recycled content of product packaging can be found in 26 of the 35 award criteria documents. The level of detail and ambition of the requirements vary considerably and range from qualitative formulations of a non-binding nature to quantified specifications on the recycled content. The level of ambition of the proof required also differs, e.g.,:

The Award Criteria for the Blue Angel for furniture DE-UZ 38 [

20] state, for example: “

The packaging must, as far as possible, consist of recycled material”. A description of the packaging and, if applicable, a justification as to why no recycled material is used must be provided as proof.

In contrast, the award criteria document for the Blue Angel for “Mechanical frame fixings for room doors without the use of construction foam” DE-UZ 218 [

21] requires packaging “

made entirely from recycled material”, whereby only a self-declaration must be submitted as proof. In between, there are several award criteria that set specific quantitative requirements for the minimum recycled content.

In a series of award criteria documents [

22,

23,

24,

25,

26,

27,

28,

29,

30] a recycled content of at least 80% is required for paper/cardboard packaging material. In some cases, 95% recycled content is required [

31,

32]. A self-declaration is required as proof in each case.

In four award criteria documents [

33,

34,

35,

36] further differentiation is made with regard to the paper and cardboard recycled content (cardboard 80%; corrugated board 25%; fiberboard 40%; spiral-wound tubes 90%); again, a self-declaration must be submitted as proof.

The requirements for the recycled content of plastic packaging range from 50 % to 80 %: DE-UZ 194 (Blue Angel for hand dishwashing detergent) requires a recycled content of at least 70% for sales packaging (in this case bottle or canister bodies) made of PET, whereby PCR material is explicitly required [

25]. For other plastics such as HDPE, at least 50% PCR is required. A recycled content of at least 50% in plastic packaging is also required for the product groups writing instruments [

29] and toys [

28]. A minimum recycled content of 80% is required for PE bags as sales packaging in the textiles product group [

23].

4.1. Regulatory Requirements

The German Packaging Law (VerpackG) does not stipulate recycled content while the final proposal of the new EU packaging and packaging waste regulation (PPWR) requires specific minimum recycled contents for different types of packaging and materials, as outlined in

Table 1:

4.2. Differentiation by Origin of Recycled Material

Regarding recycled materials, a basic distinction must first be made between PIR (Post Industrial Recycling) and PCR (Post Consumer Recycling) material. The former refers to industrial waste that arises from production or manufacturing/processing processes, for example. The material in question has not yet been used in end products. PCR, on the other hand, refers to waste from households, commercial and industrial facilities, or institutes (who are end users of the product) (ISO 14021 [

5]).

Closed loops for PIR materials are already established in many cases due to the homogeneity of (waste) material flows. However, the advancement of the circular economy demands a greater emphasis on PCR materials [

11,

37]. Therefore, preference should be given to PCR materials in the award criteria to help boost demand and further the development of the circular economy.

4.3. Origin of Recycled Material: Plastics

For plastics, a distinction must also be made between the processes used for recycling plastic waste. Mechanical recycling has been established for many years for numerous waste flows. The quality of the recycled material produced depends significantly on the homogeneity of the input flow. While chemical recycling has been a topic of discussion for several years, it has only been implemented in a few cases. The theoretical advantages of chemical recycling include the high quality of the recycled material produced. However, it also has disadvantages, such as high energy consumption, lower yield, and increased economic costs.

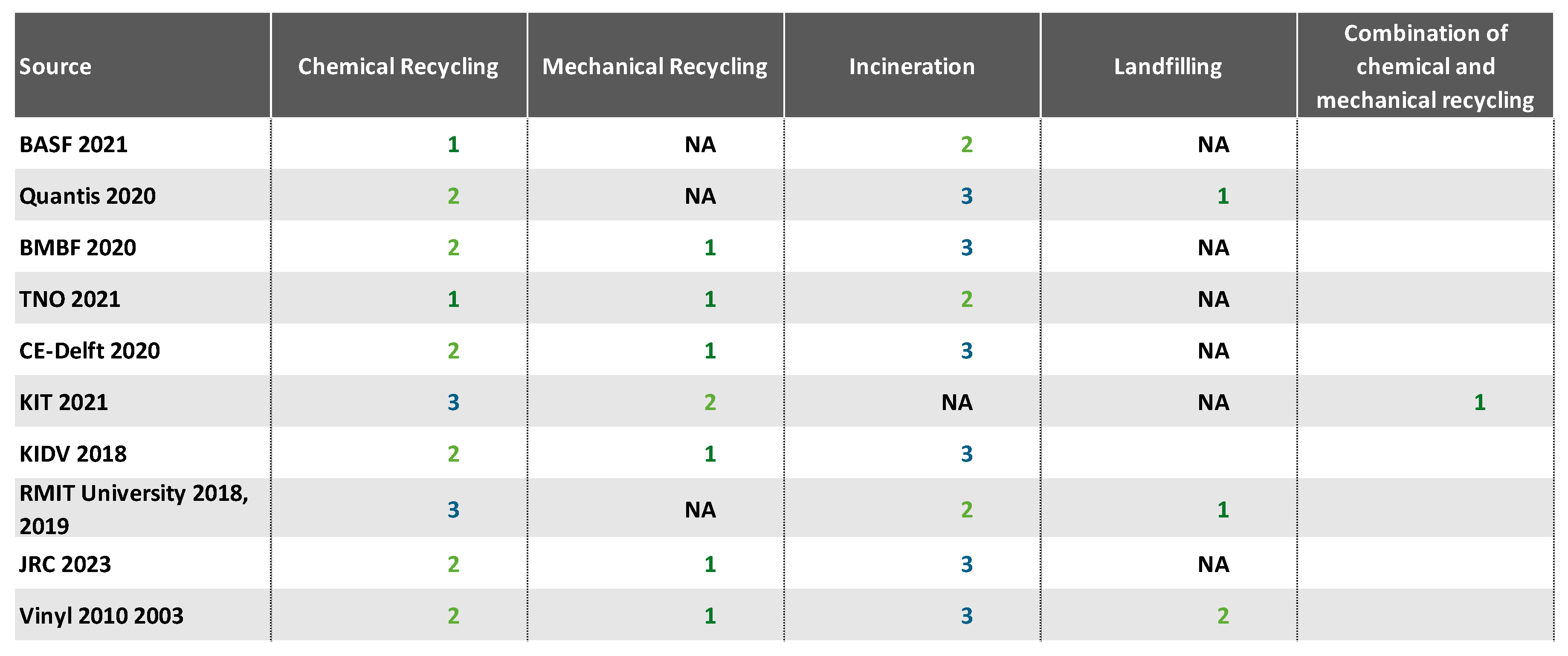

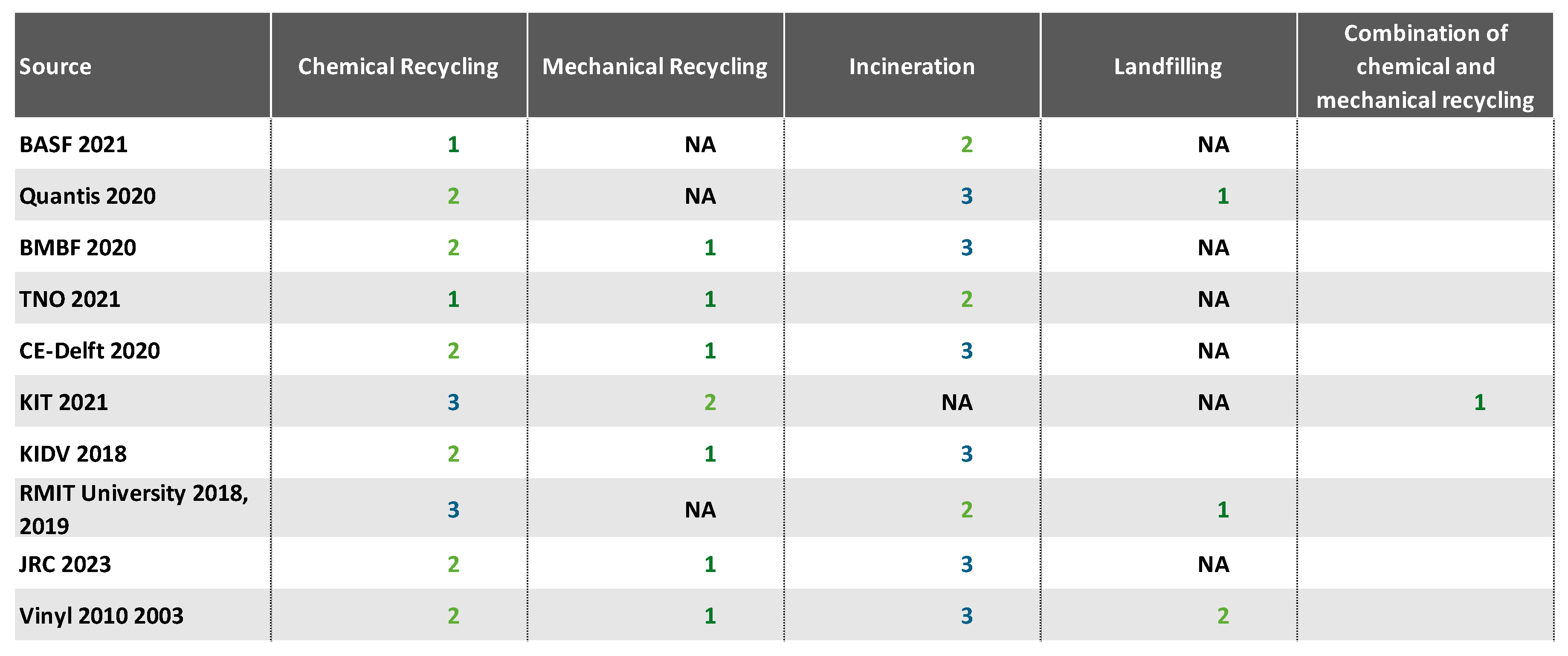

According to a meta-study [

38], mechanical recycling demonstrates environmental advantages over chemical recycling and energy recovery in the majority of studies conducted (see

Table 2). Chemical recycling is particularly considered useful for future application when it can replace energy recovery. Therefore, using post-consumer recycled (PCR) material from mechanical recycling is particularly suitable for product or sales packaging.

Table 2.

Comparison of various waste treatment measures for plastics with regard to their global warming potential (release of CO2 ) in various studies.

Table 2.

Comparison of various waste treatment measures for plastics with regard to their global warming potential (release of CO2 ) in various studies.

There are various certification systems for the origin of recycled material, including RecyClass, GRS and ISCC, some of which differ in terms of

Monitoring the material input for the recycling process

Monitoring recycling processes

Characterization of the recycled plastic

Traceability of the material for balancing in the end-product

The relevant standard that sets requirements for the origin of recycled materials in this respect is EN 15343 [

39] “Plastics recycling traceability and assessment of conformity and recycled content;”. RecyClass claims to meet this standard. The GRS does not make this claim itself; however, many of its criteria are also fulfilled (see the background report on the revision of the award criteria DE-UZ 30a, “Blue Angel eco-label for products made of recycled plastics,” 2024; [

40]). According to Müller et al. [

41], the ISCC certification is not based on EN 15343, but has its own criteria. It remains unclear whether these criteria are comparable to those of EN 15343 [

41].

Currently, the award criteria for the Blue Angel for “Products made from recycled plastics” (DE-UZ 30a) [

40] accept the EuCertPlast certification scheme (replaced by RecyClass from July 2024 on), the RecyClass certification scheme for the “Recycling Process,” and the GRS certification scheme as valid proof of origin for recycled plastics.

ISCC is not considered fundamentally suitable, which must be considered when deriving horizontal criteria. However, it should be noted that in specific cases there may be reasons for approving ISCC as a suitable certification scheme, for example in the case of the Blue Angel for synthetic turf sports pitches [

42]. ISCC was included here as valid proof, provided that calculated and plausible proof of the post-consumer share is available [

42] which is only optional for ISCC.

4.4. Origin of Recycled Material: Paper and Cardboard

For paper/cardboard used as packaging material, the Blue Angel DE-UZ 14a [

43] is a specific ecolabel awarded to “graphic paper and cardboard made from 100 % recycled paper” including material used for packaging. This ecolabel specifies the types of wastepaper from which the recycled paper and cardboard to be awarded the Blue Angel may be produced. An important requirement for the label is confirmation from an accredited certifier of the Forest Stewardship Council (FSC) or the Programme for the Endorsement of Forest Certification (PEFC). The relevant categories include “FSC Recycled” and “FSC Mix.” “FSC Recycled” indicates products that consist entirely of 100% recycled material, while “FSC Mix” labels products that are made from a combination of FSC-certified sustainable forestry materials and recycled materials.

In the paper and cardboard sector, it is essential not only that the material is derived from post-consumer recycled (PCR) wastepaper but also from which grade of wastepaper it originates. In Europe, waste paper is categorized according to the standard grade list outlined in EN 643 [

44]. This standard divides waste paper into five groups, each with various individual grades and sub-grades. Below is a list of the groups along with a selection of their respective varieties [

44]:

Group 1 (lower grade): mixed wastepaper, paper and cardboard packaging, corrugated cardboard, newspapers and magazines, sorted paper for deinking

Group 2 (medium grade): unsold newspapers, white shavings, office paper, colored letters, white bookquire, colored magazines, plastic-coated cardboard (max. 2%), printing paper

Group 3 (higher grade): light colored printing shavings (mixed), bookbinding shavings, white shavings, white letters (wood-free), white business forms, multi-print, white cardboard (multi-ply), white newsprint, white paper (wood-containing)

Group 4 (grades containing kraft): Kraft corrugated board, kraft paper sacks, kraft paper

Group 5 (special grade): mixed waste paper, mixed packaging, beverage cartons, kraft sack paper, labels

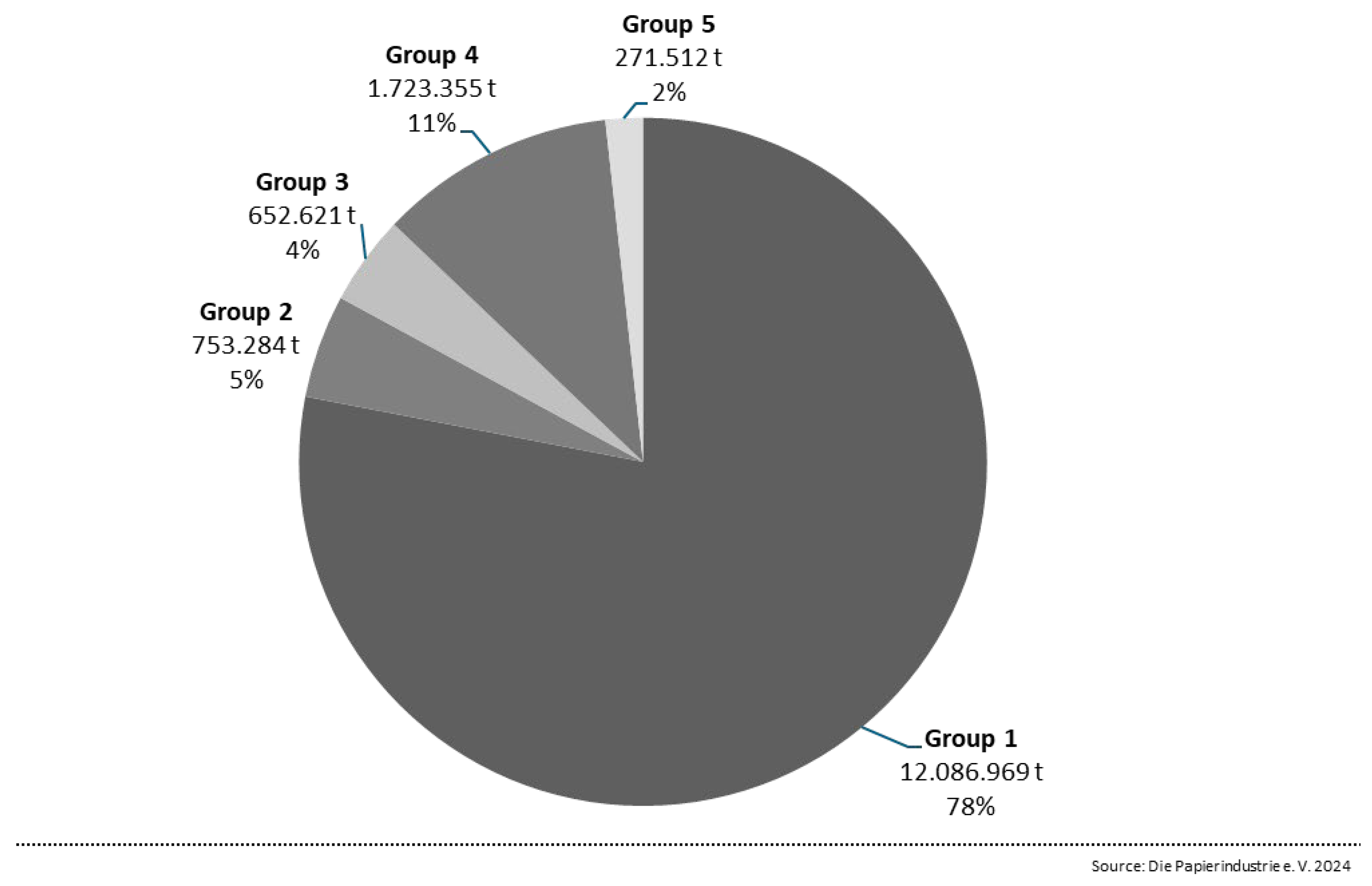

In 2023, Germany achieved a recovered paper usage rate (recovered paper consumption/paper production) of 83%, translating to a consumption of approximately 15.5 million tons. This rate has increased compared to previous years, where it ranged between 73% and 79%. As shown in

Figure 2, in 2023, lower grades of recovered paper accounted for the largest share of consumption in Germany, making up 78% of the total. In contrast, kraft grades represented 11%, medium grades 5%, better grades 4%, and special grades 2% [

45].

In the context of packaging, the statistics indicate that the usage rates of recovered paper are rather high, ranging from 90% to 110%. This signifies that the packaging sector utilizes considerably more recycled paper compared to other sectors, such as graphic papers, hygiene papers, and technical or special papers [

45].

Since lower-grade paper constitutes more than three-quarters of the wastepaper utilized, and medium and higher grades are limited in availability, it is essential to prioritize the use of lower grades for packaging materials. Conversely, higher-grade papers should be reserved for applications that require better quality, such as graphic papers.

4.5. Exploratory Market Analysis

An exploratory market analysis identified numerous products and packaging for which a recycled content of the packaging is communicated through type II declarations, some examples are listed in [

37]. This includes well-known Blue Angel products, such as sanitary paper and diapers, for which these declarations are frequently available. An analysis based on Type I ecolabels (Blue Angel, Nordic Swan, EU Ecolabel) identified more than 1,500 products with paper-based packaging containing a recycled content of at least 80% [

19,

46,

47].

4.6. Conclusion

To establish possible horizontal requirements for PCR (Post Consumer Recycled) content in packaging, it makes sense to differentiate by material type (plastic, paper and paperboard) and by packaging type (contact-sensitive or non-contact-sensitive).

For

plastic packaging, assuming the PPWR comes into effect, the minimum recycled content regulatory requirements will increase starting in 2030. The requirements set for 2030 can be immediately utilized as a baseline for packaging requirements in award criteria. It is important to ensure that PCR material is sourced from mechanical recycling. This guideline should be reviewed periodically to reflect changes in the recycling landscape. Furthermore, from 2030, the values projected for 2040 could be used. These suggested requirements for horizontal integration are shown in

Table 3.

Regarding the origin of recycled material, it seems appropriate to accept certificates from the following schemes: the RecyClass certification scheme for “Recycling Process,” the Global Recycled Standard (GRS), or an equivalent certification scheme that complies with EN 15343:2007 or DIN EN 15343:2008. These should provide calculated and credible proof of post-consumer content, in alignment with the requirements of EN 15343 [

40].

For paper and cardboard packaging, considering the current situation with waste paper volumes and recycling, requiring a minimum recycled content of 80% seems reasonable for horizontal integration in award criteria. However, the use of higher-grade waste paper (Group 3) should be excluded.

In the case of contact-sensitive packaging made from paper or cardboard, using recycled material can be challenging due to existing legal requirements regarding content of substances of concern. As a result, it may not be feasible to meet the minimum recycled content requirements.

Verification of the origin of the recycled paper or cardboard materials should align with [

43]. Specifically, it is recommended to obtain confirmation from an accredited FSC/PEFC certifier or an “FSC Recycled” or “FSC Mix” certificate.

5. Recylability

Recyclability means the gradual suitability of packaging to substitute virgin material in typical material applications after passing through industrially available recycling processes [

48].

In Blue Angel award criteria, in most cases, the recyclability requirements typically align with the “minimum standard” established by the German Central Agency Packaging Register, which evaluates the recyclability of packaging within the system’s participation [

48]. Generally, the award criteria necessitate either “compliance” or “observance” of these minimum recyclability standards without further specification. However, in some instances, specific quantifiable recyclability requirements are outlined [

32,

49].

Table 4 offers an overview of the common formulations with reference to the “minimum standard”.

In addition, there are award criteria that set specific design requirements, such as:

Banning full-surface and partial coatings (plastic and metal coatings) [

23,

29,

32]

Banning composite materials which use plastics or metals [

30]

If adhesive labels are used, they should be removable during the recycling process. [

52]

5.1. Regulatory Requirements

Besides the current requirements in eco-label award criteria, there are regulatory requirements in place: Both, the German packaging law (VerpackG) and the EU PPWR set out requirements regarding the recyclability of packaging. Article 4 of the VerpackG requires “Packaging must be developed, manufactured and distributed in such a way that [...] their reuse or recovery, including recycling, is possible in accordance with the waste hierarchy and the environmental impact of the reuse, preparation for reuse, recycling, other recovery or disposal of the packaging waste is minimized; [and] the reusability of packaging and the proportion of secondary raw materials in the packaging mass is increased to the highest possible level that is technically possible and economically reasonable […].” In addition, in article 16 reuse and recycling quotas are defined for different groups of material.

The EU PPWR also demands the recyclability of packaging. Regarding the recyclability of packaging, the PPWR defines four performance levels (A to C and non-recyclable):

Level A corresponds to a recyclability per unit, by weight of greater than or equal to 95,

Level B corresponds to a recyclability per unit, by weight of greater than or equal to 80,

Level C corresponds to a recyclability per unit, by weight of greater than or equal to 70,

Not recyclable C corresponds to a recyclability per unit, by weight of less than 70 %.

Accordingly, packaging is no longer considered recyclable from 2030 if it is less than 70% recyclable.

5.2. Guidelines for Recyclable Packaging

Many design guidelines and related documents exist regarding recyclable packaging, such as those by Jepsen et al. [

11], Gürlich et al. [

53], cyclos [

54], or ALDI [

55]. These guidelines largely align with the requirements outlined in the minimum standard established by ZSVR [

48]. The differences among these documents often lie in the level of detail and the specific focus of their considerations. Generally, the requirements can be traced back to the core criteria of the minimum standard, which address the following key issues:

Is there a sorting and recycling infrastructure in place?

Can the packaging be sorted? Can components be separated?

Does the packaging contain any substances or components that could pose a problem in existing recycling practice?

5.3. Exploratory Market Analysis

Achieving a high level of recyclability is feasible for many types of product packaging [

37]. The key factors for this include using recyclable mono-materials (e.g., PE, PP, paper/ cardboard) for production, minimizing the use of coloring, and employing small-format labeling or printing [

56]. A 2019 study found that over 90% of plastic bottles, cups, trays, and other “dimensionally stable” plastic packaging made from standard polymers like PP and PE can be processed for high-quality recycling [

57]. Similar conditions apply to packaging made from ferrous metals, glass, paper, liquid cartons, and aluminum. However, for flexible packaging made of PE, the recyclability rate is slightly lower, at around 70% [

57]. In another study, Schüler and Wilhelm [

58] determined that (on the German market),

10.7 % of all packaging is less than 90 % recyclable, and

14.9% of all packaging is less than 95% recyclable.

Regarding packaging made of plastics, metals and composites, the findings by [

58] indicate

32 % of the packaging is less than 90 % recyclable, and

44 % of the packaging is less than 95 % recyclable.

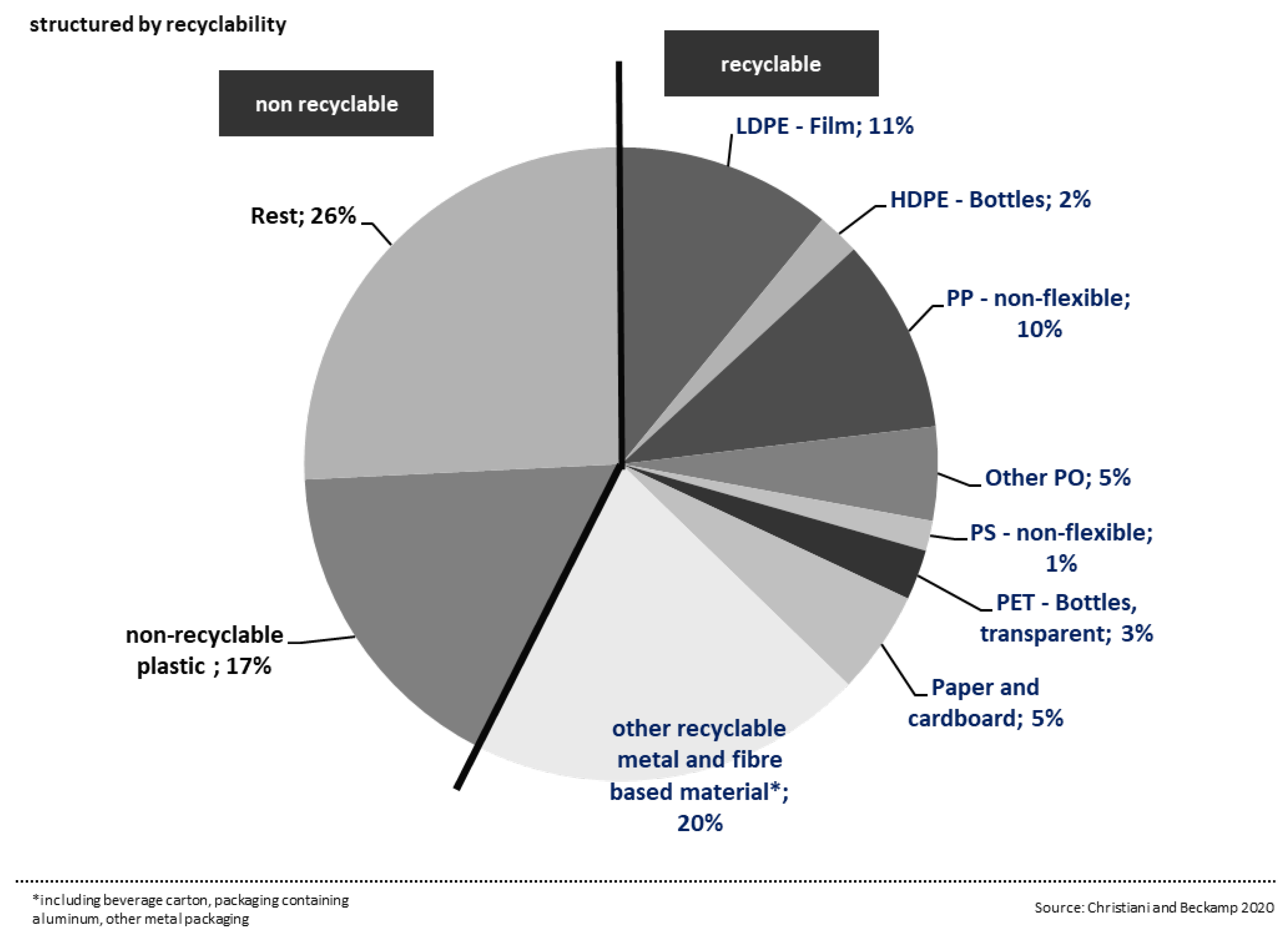

The recyclability of the entire packaging waste fraction in Germany was assessed by Christiani and Beckamp [

59]. Their study found that 57% of the packaging waste fraction is generally suitable for material recycling, as illustrated in

Figure 3.

The collection system for recyclable packaging also encompasses non-packaging items made from the same materials, along with discards and other sorting residues. As a result, the overall recyclability of the packaging increases. In fact, it can be stated that a significant portion of the packaging available in the market is already over 90% recyclable.

5.4. Conclusion

The requirement for packaging to be recyclable according to the minimum standard is a sensible and targeted approach. This requirement, depending on its specific formulation, may implement or exceed existing legal standards and can be found in various award criteria already.

Establishing a high degree of recyclability in line with the minimum standard appears reasonable and achievable as a horizontal requirement for packaging in ecolabel award criteria. A minimum recyclability rate of 90% is considered an ambitious yet attainable target for the majority of plastic and paper and cardboard packaging available on the market, potentially with minor adjustments.

According to research by Schüler and Wilhelm [

58] nearly 99% of paper and cardboard packaging was already over 95% recyclable in 2021, while around 74% of plastic packaging met this threshold. However, it is important to note that only a small proportion of composite packaging—approximately 29% in 2021—was recyclable at rates exceeding 90% [

58].

6. Conclusions and Outlook

By integrating horizontal packaging-related criteria in eco-labels the use of more sustainable packaging materials and designs can be promoted, contributing to reducing greenhouse gas emissions and waste. A horizontal integration of packaging-related criteria as a minimum standard can enhance consistency between eco-labels for different product groups.

For the requirement areas recycled content (including material origin) and recyclability, it is possible to establish requirements that appear to be largely feasible to be horizontally integrated. The focus for these requirements is primarily on the material groups that are most relevant in the packaging sector, specifically plastics and paper / cardboard. Requirements addressing recycled content and recyclability can be formulated for these material groups, and many already function effectively in practice, making them suitable as minimum standards.

However, for packaging made from biogenic sources (excluding paper and board), such as cotton fibers or wood, establishing a minimum recycled content requirement does not currently seem feasible. It is also important to note that packaging made from these materials is not currently recycled within the existing infrastructure for packaging, which would exclude it from the formulated recyclability requirements. A fundamental decision is necessary regarding how these packaging materials should be addressed, potentially with different criteria.

Regarding other requirement areas, such as packaging weight-to-benefit ratio, or reusability, no horizontal recommendations can be made. Each of these cases requires specific consideration for the respective product group to evaluate the reasonableness of corresponding requirements.

It is worth noting that there may be specific product groups where implementing the recommended requirements is not practical. For instance:

If no corresponding packaging standard has been established in that product group (e.g., products that traditionally use composite packaging), it may result in a broad exclusion or the exclusion of otherwise particularly ecologically advantageous products due to the packaging requirements.

Specific legal requirements may exist (e.g., food contact quality standards) that could hinder increasing the recycled content.

Therefore, it is essential to conduct an examination and engage in discussions with stakeholders (such as expert discussions or hearings) during the process of developing the award criteria.

Funding

This research is based on findings from a project commissioned by the German Environmental Protection Agency (Umweltbundesamt), grant number FKZ 3719 37 310 0.

Conflicts of Interest

The authors declare no conflicts of interest

Abbreviations

The following abbreviations are used in this manuscript:

| PPWR |

Packaging and Packaging Waste Regulation |

| PPWD |

Packaging and Packaging Waste Directive |

| VerpackG |

Verpackungsgesetz (German Packaging Law) |

References

- Wojnarowska, M.; Sołtysik, M.; Prusak, A. Impact of eco-labelling on the implementation of sustainable production and consumption. Environmental Impact Assessment Review 2021, 86, 106505. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- UNEP. Eco-labelling. Available online: https://www.unep.org/explore-topics/resource-efficiency/what-we-do/responsible-industry/eco-labelling (accessed on 8 January 2025).

- Otto, S.; Strenger, M.; Maier-Nöth, A.; Schmid, M. Food packaging and sustainability – Consumer perception vs. correlated scientific facts: A review. Journal of Cleaner Production 2021, 298, 126733. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- ISO. Environmental labels and declarations – Type I environmental labelling – Principles and procedures, 2018 (14024:2018).

- ISO. Environmental labels and declarations – Self-declared environmental claims (Type II environmental labelling), Amd 1:2021, 2021 (14021:2016).

- ISO. Environmental labels and declarations – Type III environmental declarations – Principles and procedures, 2011 (14025:2006).

- Spengler, L.; Jepsen, D.; Zimmermann, T.; Wichmann, P. Product sustainability criteria in ecolabels: a complete analysis of the Blue Angel with focus on longevity and social criteria. Int J Life Cycle Assess 2019, 19, 1631. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- EU Rat. Proposal for a REGULATION OF THE EUROPEAN PARLIAMENT AND OF THE COUNCIL on packaging and packaging waste, amending Regulation (EU) 2019/1020 and Directive (EU) 2019/904, and repealing Directive 94/62/EC; Publications office of the European Union: Brüssel, 2024. Available online: https://www.europarl.europa.eu/doceo/document/TA-9-2024-0318_EN.html#title2 (accessed on 15 October 2024).

- Zimmermann, T.; Memelink, R.; Rödig, L.; Reitz, A.; Pelke, N.; John, R.; Eberle, U. Die Ökologisierung des Onlinehandels: Neue Herausforderungen für die umweltpolitische Förderung eines nachhaltigen Konsums. Teilbericht I; UBA-Texte 227/2020, Dessau-Roßlau, Hamburg, 2020. Available online: https://www.umweltbundesamt.de/sites/default/files/medien/5750/publikationen/2020_12_03_texte_227-2020_online-handel.pdf (accessed on 22 March 2021).

- Jepsen, D.; Wirth, O.; Spengler, L.; Rödig, L.; Zimmermann, T.; Jäger, I.; Gartiser, S. Weiterentwicklung des Umweltzeichens Blauer Engel, Rahmenvorhaben 2014-2018; UBA-Texte 122/2020, Dessau, 2020. Available online: https://www.umweltbundesamt.de/sites/default/files/medien/1410/publikationen/2020-07-02_texte_122-2020_weiterentwicklung-be_2014-2018_0.pdf (accessed on 15 February 2024).

- Jepsen, D.; Zimmermann, T.; Rödig, L. Eco Design von Kunststoff-Verpackungen: Der Management-Leitfaden des Runden Tisches, Bad Homburg, 2019. Available online: https://ecodesign-packaging.org/wp-content/uploads/2019/06/ecoDesign_Kernleitfaden_WEBpdf.pdf.

- Migros. Verpackungen im M-Check • Migros. Available online: https://www.migros.ch/de/content/m-check-verpackungen (accessed on 18 April 2024).

- REWE. Leitlinie für umweltfreundliche Verpackungen, Köln, 2023. Available online: https://www.rewe-group.com/content/uploads/2020/12/leitlinie-umweltfreundlichere-verpackungen-20.04.2023.pdf?t=2024041811 (accessed on 18 April 2024).

- ALDI SÜD. Umweltfreundliche Verpackungen – Was wir tun | ALDI SÜD. Available online: https://www.aldi-sued.de/de/nachhaltigkeit/verpackungen-kreislaufwirtschaft/umweltfreundliche-verpackungen.html (accessed on 18 April 2024).

- INCPEN. The Responsible Packaging Code. Available online: https://incpen.org/the-responsible-packaging-code/ (accessed on 18 April 2024).

- Burger, A.; Cayé, N. Aufkommen und Verwertung von Verpackungsabfällen in Deutschland im Jahr 2020; UBA-Texte 109/2022, Dessau, 2022. Available online: https://www.umweltbundesamt.de/sites/default/files/medien/11850/publikationen/109_2022_texte_aufkommen_und_verwertung_von_verpackungsabfaellen.pdf (accessed on 11 June 2024).

- Cayé, N.; Marasus, S.; Schüler, K. Aufkommen und Verwertung von Verpackungsabfällen in Deutschland im Jahr 2021; UBA-Texte 162/2023, Dessau, 2023. Available online: https://www.umweltbundesamt.de/sites/default/files/medien/11850/publikationen/162_2023_texte_aufkommen_verpackungsabfaelle.pdf (accessed on 11 June 2024).

-

Verpackungsgesetz vom 5. Juli 2017 (BGBl. I S. 2234), das zuletzt durch Artikel 6 des Gesetzes vom 25. Oktober 2023 (BGBl. 2023 I Nr. 294) geändert worden ist. Available online: https://www.gesetze-im-internet.de/verpackg/BJNR223410017.html (accessed on 15 October 2024).

- Blauer Engel. Vergabekriterien. Available online: https://www.blauer-engel.de/de/zertifizierung/vergabekriterien (accessed on 19 December 2024).

- RAL. Blauer Engel Emissionsarme Möbel und Lattenroste aus Holz und Holzwerkstoffen, 5th ed.; RAL Umwelt: Bonn, 2022 (38). Available online: https://produktinfo.blauer-engel.de/uploads/criteriafile/de/DE-UZ%20038-202201-de-Kriterien-V5.pdf (accessed on 28 February 2024).

- RAL. Blauer Engel Mechanische Zargenbefestigung für Zimmertüren ohne Einsatz von Bauschaum; RAL Umwelt: Bonn, 2021 (218). Available online: https://produktinfo.blauer-engel.de/uploads/criteriafile/de/DE-UZ%20218-202101-de%20Kriterien-V2.pdf (accessed on 28 February 2024).

- RAL. Blauer Engel Schuhe und Einlegesohlen, 4th ed.; RAL Umwelt: Bonn, 2018 (155). Available online: https://produktinfo.blauer-engel.de/uploads/criteriafile/de/DE-UZ%20155-201807-de%20Kriterien-V4.pdf (accessed on 28 February 2024).

- RAL. Blauer Engel Textilien, 3rd ed.; RAL Umwelt: Bonn, 2023 (154). Available online: https://produktinfo.blauer-engel.de/uploads/criteriafile/de/DE-UZ%20154-202301-de-Kriterien-V3.pdf (accessed on 28 February 2024).

- RAL. Blauer Engel Leder, 5th ed.; RAL Umwelt: Bonn, 2015 (148). Available online: https://produktinfo.blauer-engel.de/uploads/criteriafile/de/DE-UZ%20148-201503-de%20Kriterien-V5.pdf (accessed on 28 February 2024).

- RAL. Blauer Engel Handgeschirrspülmittel und Reiniger für harte Oberflächen, 1.1th ed.; RAL Umwelt: Bonn, 2022 (194). Available online: https://produktinfo.blauer-engel.de/uploads/criteriafile/de/DE-UZ%20194-202201-de-Kriterien-V1.1.pdf (accessed on 28 February 2024).

- RAL. Blauer Engel Maschinengeschirrspülmittel, 3rd ed.; RAL Umwelt: Bonn, 2022 (201). Available online: https://produktinfo.blauer-engel.de/uploads/criteriafile/de/DE-UZ%20201-202201-de-Kriterien-V3.pdf (accessed on 28 February 2024).

- RAL. Blauer Engel Waschmittel, 1st ed.; RAL Umwelt: Bonn, 2022 (202). Available online: https://produktinfo.blauer-engel.de/uploads/criteriafile/de/DE-UZ%20202-202201-de-Kriterien-V1.pdf (accessed on 28 February 2024).

- RAL. Blauer Engel Spielzeug, 4th ed.; RAL Umwelt: Bonn, 2017 (207). Available online: https://produktinfo.blauer-engel.de/uploads/criteriafile/de/DE-UZ%20207-201701-de%20Kriterien-V4.pdf (accessed on 17 April 2024).

- RAL. Blauer Engel Schreibgeräte und Stempel, 7th ed.; RAL Umwelt: Bonn, 2016 (200). Available online: https://produktinfo.blauer-engel.de/uploads/criteriafile/de/DE-UZ%20200-201601-de%20Kriterien-V7.pdf (accessed on 17 April 2024).

- RAL. Blauer Engel Malfarben, 6th ed.; RAL Umwelt: Bonn, 2016 (199). Available online: https://produktinfo.blauer-engel.de/uploads/criteriafile/de/DE-UZ%20199-201601-de%20Kriterien-V6.pdf (accessed on 17 April 2024).

- RAL. Blauer Engel Ungebleichte Koch- und Heißfilterpapiere, 5th ed.; RAL Umwelt: Bonn, 2014 (65). Available online: https://produktinfo.blauer-engel.de/uploads/criteriafile/de/DE-UZ%20065-201402-de%20Kriterien-V5.pdf (accessed on 18 April 2024).

- RAL. Blauer Engel Hygienepapier, 2nd ed.; RAL Umwelt: Bonn, 2022 (5). Available online: https://produktinfo.blauer-engel.de/uploads/criteriafile/de/DE-UZ%20005-202201-de-Kriterien-V2.pdf (accessed on 16 April 2024).

- RAL. Blauer Engel Aufbereitete Tonerkatuschen und Tintenpatronen für Drucker, Kopierer und Multifunktionsgeräte, 2nd ed.; RAL Umwelt: Bonn, 2021 (177). Available online: https://produktinfo.blauer-engel.de/uploads/criteriafile/de/DE-UZ%20177-202107-de-Kriterien-V2.pdf (accessed on 28 February 2024).

- RAL. Blauer Engel Bürogeräte mit Druckfunktion (Drucker und Multifunktionsgeräte), 3rd ed.; RAL Umwelt: Bonn, 2021 (219). Available online: https://produktinfo.blauer-engel.de/uploads/criteriafile/de/DE-UZ%20219-202101-de-Kriterien-V3-2021-11-10.pdf (accessed on 28 February 2024).

- RAL. Blauer Engel Energie- und wassersparende Hand- und Kopfbrausen, 1st ed.; RAL Umwelt: Bonn, 2022 (157). Available online: https://produktinfo.blauer-engel.de/uploads/criteriafile/de/DE-UZ%20157-202201-de-Kriterien-V1.pdf (accessed on 28 February 2024).

- RAL. Blauer Engel Mobiltelefone, Smartphones und Tablets, 2nd ed.; RAL Umwelt: Bonn, 2022 (106). Available online: https://produktinfo.blauer-engel.de/uploads/criteriafile/de/DE-UZ%20106-202201-de%20Kriterien-V2.pdf (accessed on 16 April 2024).

- Zimmermann, T.; Jepsen, D.; Heckel, F. Möglichkeiten und Überlegungen zur horizontalen Berücksichtigung von Anforderungen an die Produktverpackung im Blauen Engel: Teilleistung im Vorhaben „Weiterentwicklung des Produkt-Portfolios des Umweltzeichens Blauer Engel mit dem Schwerpunkt auf Dienstleistungen“; UBA-Texte 18/2025, Dessau, Hamburg, 2025. Available online: https://www.umweltbundesamt.de/sites/default/files/medien/11850/publikationen/18_2025_texte.pdf (accessed on 14 April 2025).

- BASF. Life-Cycle Assessments of chemical recycling: an overview, 2023. Available online: https://www.basf.com/global/documents/en/sustainability/we-drive-sustainable-solutions/circular-economy/chemcycling/LCA%20metastudy%20slide%20deck_final.pdf.assetdownload.pdf (accessed on 26 July 2023).

- DIN. Kunststoffe - Kunststoff-Rezyklate - Rückverfolgbarkeit bei der Kunststoffverwertung und Bewertung der Konformität und des Rezyklatgehalts; Beuth Verlag: Berlin, 2008, 13.030.50; 83.080.20 (15343:2007).

- RAL. Blauer Engel Produkte aus Recycling-Kunststoffen, 1st ed.; RAL Umwelt: Bonn, 2024 (30a). Available online: https://produktinfo.blauer-engel.de/uploads/criteriafile/de/DE-UZ%2030a-202401-de-Kriterien-V1.pdf (accessed on 18 April 2024). Bonn.

- Müller, R.; Wiesemann, E.; Herrmann, A.; Dieroff, J.; Betz, J.; Bulach, W. Beschaffung von Kunststoffprodukten aus Post-Consumer Rezyklaten: Handreichung für den öffentlichen Einkauf; UBA-Texte 130/2021, Dessau, 2021. Available online: https://www.umweltbundesamt.de/sites/default/files/medien/479/publikationen/texte_130-2021_handreichung_kunststoffrezyklat-beschaffung.pdf (accessed on 22 January 2024).

- RAL. Blauer Engel Kunststoffrasensysteme und -sportplätze; RAL Umwelt: Bonn, 2024 (235).

- RAL. Grafische Papiere und Kartons aus 100 % Altpapier (Recyclingpapier und -karton), 6th ed.; RAL Umwelt: Bonn, 2020 (14a). Available online: https://produktinfo.blauer-engel.de/uploads/criteriafile/de/DE-UZ%20014a-202001-de%20Kriterien-V6.pdf (accessed on 18 April 2024).

- DIN. Papier, Karton und Pappe - Europäische Liste der Altpapier-Standardsorten; Beuth Verlag: Berlin, 2014 (643:2014-11).

- Die Papierindustrie e. V. Leistungsbericht PAPIER 2024, Berlin, 2024. Available online: https://www.papierindustrie.de/fileadmin/0002-PAPIERINDUSTRIE/07_Dateien/XX-LB/PAPIER_2024_Leistungsbericht_digital.pdf (accessed on 25 July 2024).

- Nordic Swan. Nordic Swan Ecolabel / Criteria. Available online: https://www.nordic-swan-ecolabel.org/criteria/ (accessed on 14 April 2025).

- EU Ecolabel. EU Ecolabel Product Catalogue. Available online: https://app.powerbi.com/view?r=eyJrIjoiMzAyMzVkNWMtNmJhOS00ZDg4LWIzMTItNzczMDkwODBiNjRmIiwidCI6ImIyNGM4YjA2LTUyMmMtNDZmZS05MDgwLTcwOTI2ZjhkZGRiMSIsImMiOjh9 (accessed on 14 April 2025).

- ZSVR. Mindeststandard für die Bemessung der Recyclingfähigkeit von systembeteiligungspflichtigen Verpackungen gemäß § 21 Abs. 3 VerpackG: im Einvernehmen mit dem Umweltbundesamt, Osnabrück, 2023. Available online: https://www.verpackungsregister.org/fileadmin/files/Mindeststandard/Mindeststandard_VerpackG_Ausgabe_2023.pdf (accessed on 16 April 2024).

- RAL. Blauer Engel Windeln, Damenhygiene- und Inkontinenzprodukte (Absorbierende Hygieneprodukte) DE-UZ 208-202101-de Kriterien-V3, 3rd ed., 2021 (208). Available online: https://produktinfo.blauer-engel.de/uploads/criteriafile/de/DE-UZ%20208-202101-de%20Kriterien-V3.pdf (accessed on 16 April 2024).

- RAL. Blauer Engel Dach- und Dichtungsbahnen, 3rd ed.; RAL Umwelt: Bonn, 2022 (224). Available online: https://produktinfo.blauer-engel.de/uploads/criteriafile/de/DE-UZ-224-202207-de-Kriterien-V3.pdf (accessed on 16 April 2024).

- RAL. Blauer Engel Dach- und Formsteine aus Beton, 1st ed.; RAL Umwelt: Bonn, 2023 (227). Available online: https://produktinfo.blauer-engel.de/uploads/criteriafile/de/DE-UZ%20227-202301-de-Kriterien-V1.pdf (accessed on 16 April 2024).

- RAL. Blauer Engel Shampoos, Duschgele und Seifen und weitere sogenannte “Rinse-off”- (“Abspülbare”) - Kosmetikprodukte, 3rd ed.; RAL Umwelt: Bonn, 2020 (203). Available online: https://produktinfo.blauer-engel.de/uploads/criteriafile/de/DE-UZ%20203-202001-de%20Kriterien-2020-06-25.pdf (accessed on 16 April 2024).

- Gürlich, U.; Kladnik, V.; Pavlovic, K. Circular Packaging Design Guideline. Empfehlungen für die Gestaltung recyclinggerechter Verpackungen, Wien, 2022. Available online: https://digital.obvsg.at/obvfcwacc/download/pdf/8086818?originalFilename=true (accessed on 18 April 2024).

- cyclos. Prüfung und Testierung der Recyclingfähigkeit: Anforderungs- und Bewertungskatalog des Institutes cyclos-HTP zur EU-weiten Zertifizierung, Aachen, 2022. Available online: https://www.cyclos-htp.de/publikationen/a-b-katalog/ (accessed on 15 October 2024).

- ALDI. ALDI International Recyclability Guidelines, Essen, 2024. Available online: https://cr.aldisouthgroup.com/en/download/aldis-international-recyclability-guidelines-version-3-2024 (accessed on 18 April 2024).

- ZSVR. Recyclingfähigkeit von Verpackungen. Available online: https://www.verpackungsregister.org/information-orientierung/themen-verpackg/recyclingfaehigkeit-von-verpackungen (accessed on 30 April 2024).

- Dehoust, G.; Hermann, A.; Christiani, J.; Beckamp, S.; Bünemann, A.; Bartnik, S. Ermittlung der Praxis der Sortierung und Verwertung von Verpackungen im Sinne des § 21 VerpackG: kologische Gestaltung der Beteiligungsentgelte gemäß § 21 VerpackG, insbesondere Entwicklung einer Methodik zur Erfassung der Praxis der Sortierung und Verwertung (ÖkoGeB); UBA-Texte 11/2021, Dessau-Roßlau, Berlin, Darmstadt, Aachen, Osnabrück, 2021. Available online: https://www.umweltbundesamt.de/sites/default/files/medien/5750/publikationen/2021-01-22_texte_11-2020_oekologische_beteiligungsentgelte.pdf (accessed on 3 November 2021).

- Schüler, K.; Wilhelm, J. Ermittlung des Anteils hochgradig recyclingfähiger systembeteiligungspflichtiger Verpackungen auf dem deutschen Markt; UBA-Texte 78/2023, Dessau, 2023. Available online: https://www.umweltbundesamt.de/sites/default/files/medien/11850/publikationen/78_2023_texte_ermittlung_des_anteils.pdf (accessed on 30 April 2024).

- Christiani, J.; Beckamp, S. Was können die mechanische Aufbereitung von Kunststoffen und das werkstoffliche Recycling leisten? In Energie aus Abfall; Thiel, S., Thomé-Kozmiensky, E., Quicker, P., Gosten, A., Eds.; Thomé-Kozmiensky Verlag GmbH: Neuruppin, 2020; pp 139–153, ISBN 978-3-944310-50-3.

|

Disclaimer/Publisher’s Note: The statements, opinions and data contained in all publications are solely those of the individual author(s) and contributor(s) and not of MDPI and/or the editor(s). MDPI and/or the editor(s) disclaim responsibility for any injury to people or property resulting from any ideas, methods, instructions or products referred to in the content. |

© 2025 by the authors. Licensee MDPI, Basel, Switzerland. This article is an open access article distributed under the terms and conditions of the Creative Commons Attribution (CC BY) license (http://creativecommons.org/licenses/by/4.0/).