Submitted:

08 October 2024

Posted:

10 October 2024

You are already at the latest version

Abstract

Keywords:

1. Introduction

1.1. Sustainable Development

1.2. Circular Economy and Its Relation to Sustainable Development

1.3. Plastic and Sustainable Development

1.4. Flexible Packaging and Functions

1.5. Circular Economy and Flexible Packaging

1.6. Sustainable Materials for Flexible Packaging

- Photodegradation: Sunlight alters material structures, reducing molecular weight [40].

- Thermal degradation: Polymers degrade at their melting point, transitioning from solid to liquid [41].

- Chemical degradation: Involves structural changes to polymers [42].

- Compostable polymers: These degrade into biomass, carbon dioxide, water, and inorganic compounds quickly under specific conditions [43].

1.7. Recyclability for Flexible Packaging

- Primary (re-extrusion): Reprocessing plastic to create materials similar to the original.

- Secondary (mechanical): Recovering plastics through grinding and reprocessing to produce new products.

- Tertiary (chemical): Breaking down plastics chemically into basic components to create new materials.

- Quaternary (energy recovery): Converting plastic waste into energy through incineration.

2. Materials and Methods

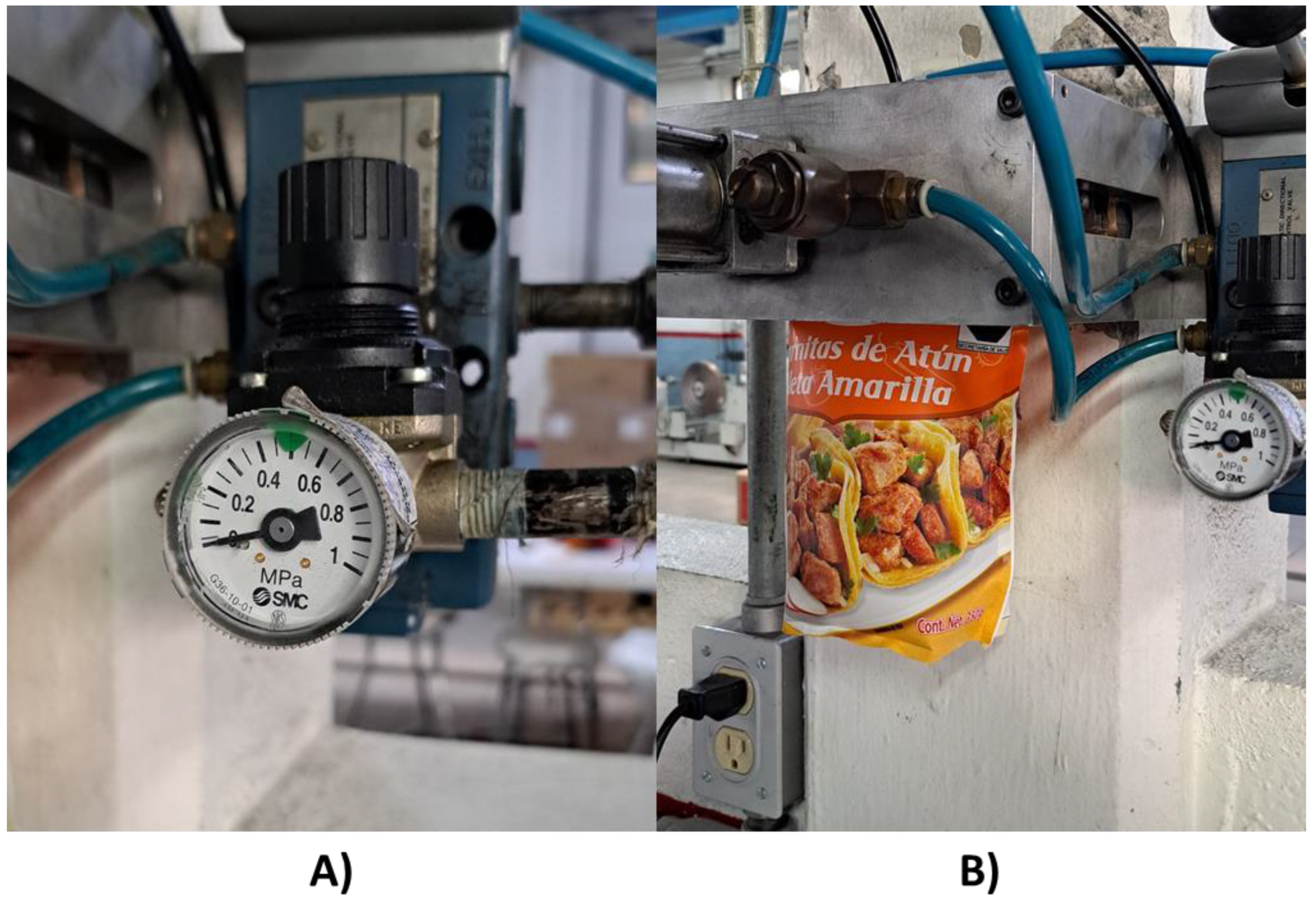

2.1. Processes for Obtaining Flexible Doypack Containers and Laminated Coil

2.2. Proposals for the Redesign of Flexible Packaging

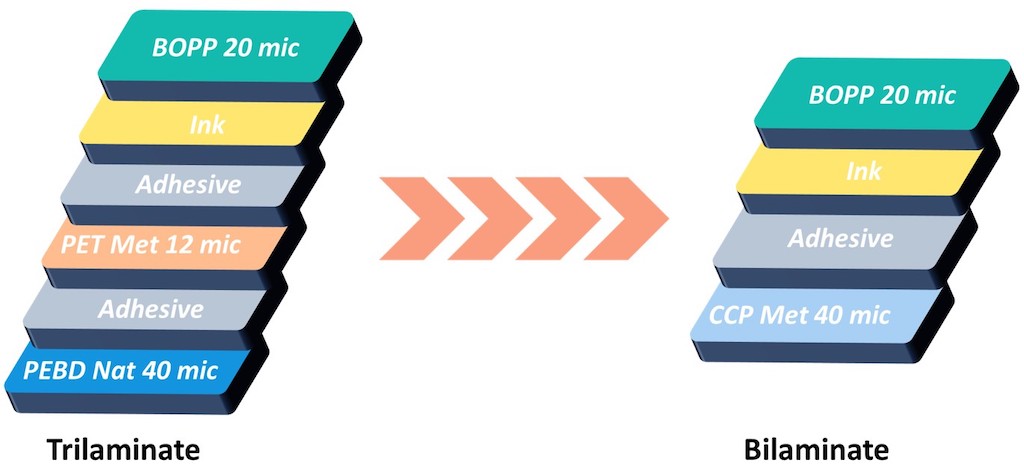

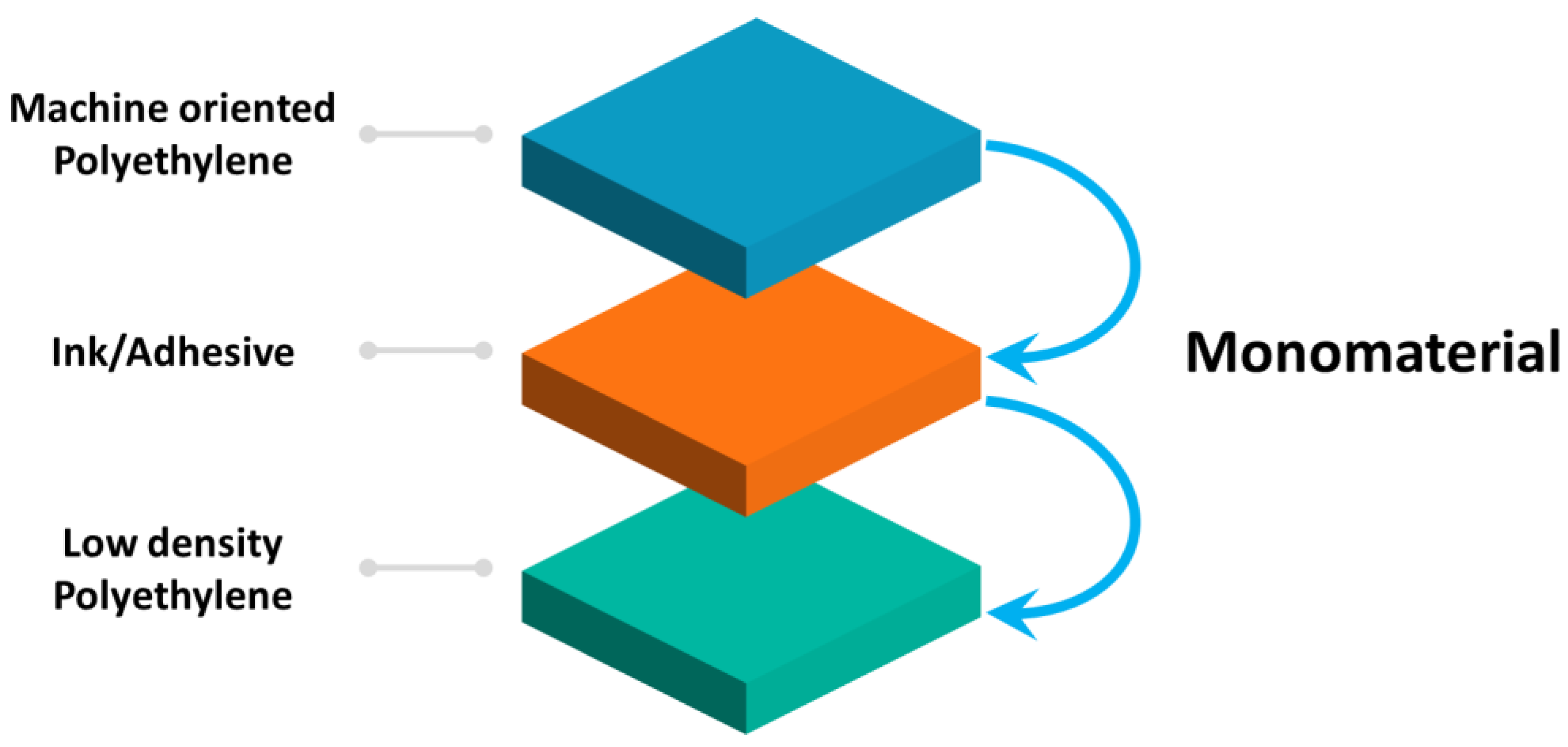

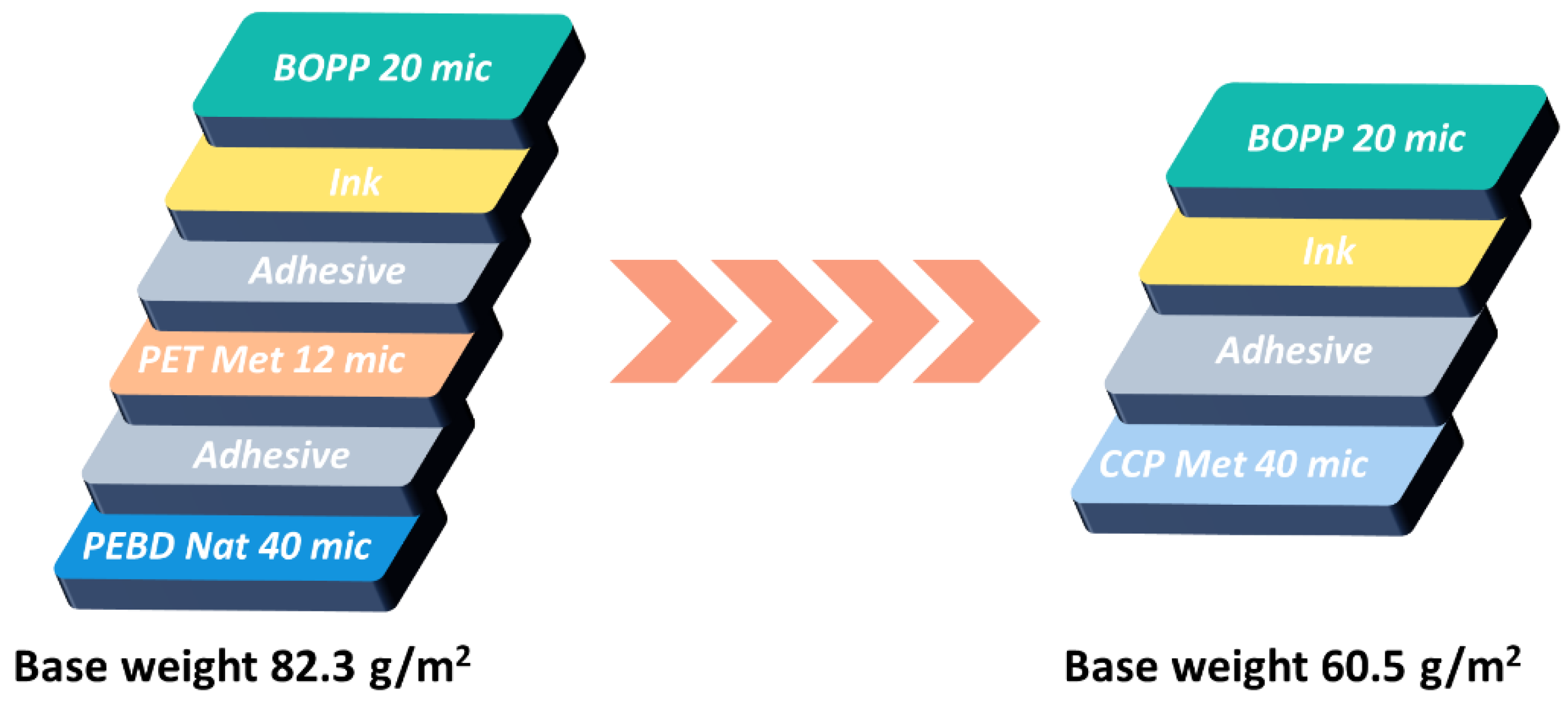

2.3. Redesign and Reduction of Lamination Layers in Trilaminate Structure for Flexible Packaging for the Food Sector, Laminated Coil Type, and Implementation of Monomaterial Structure

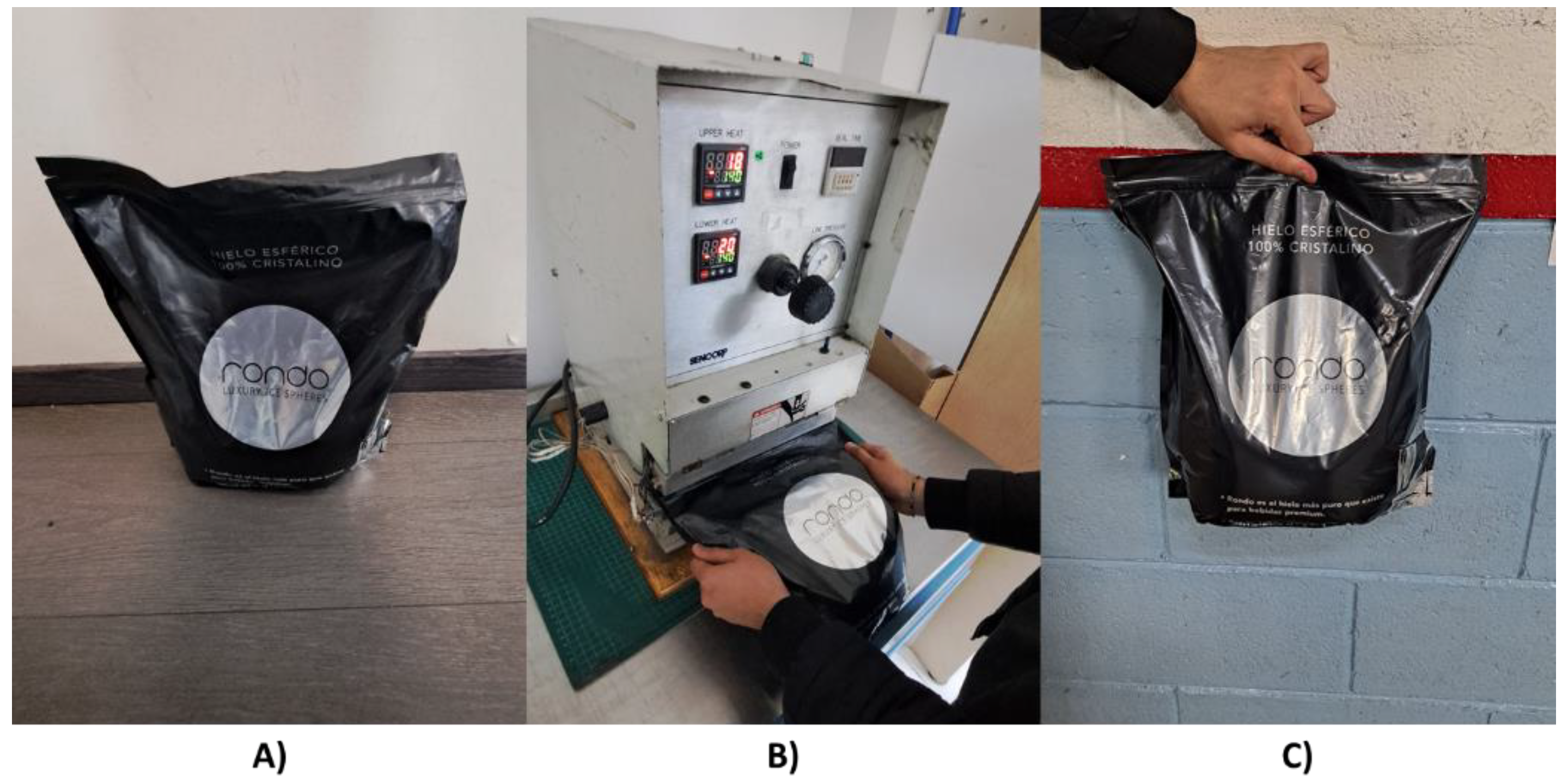

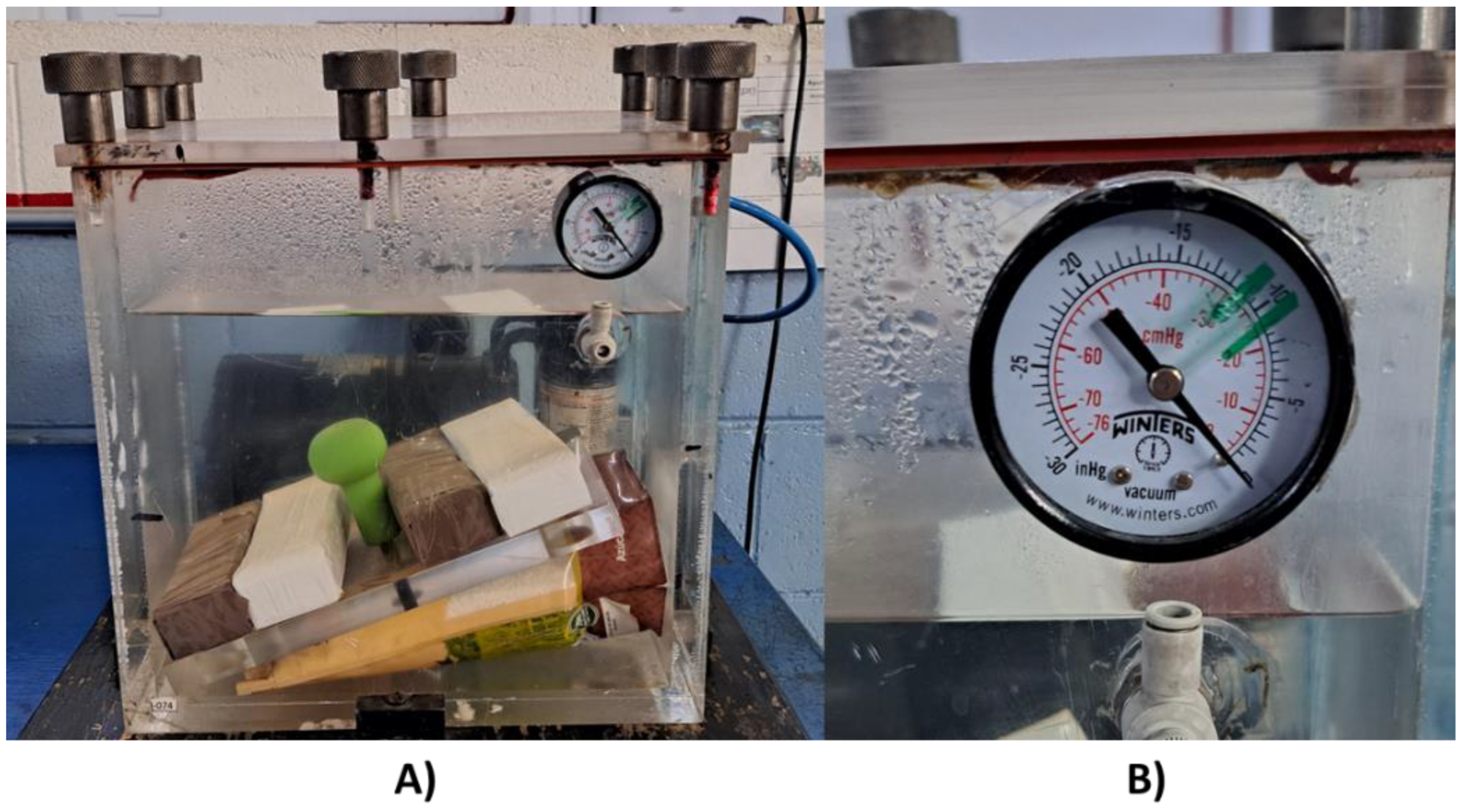

2.4. Redesign of Flexible Food Packaging in Doypack Format with a Three-Layer and Multi-Polymeric Structure to a Monomaterial Using Polyethylene as the Base Polymer

2.5. Redesign of Trilaminate Flexible Packaging to a Hybrid Paper Packaging with a High Barrier Plastic and an Additive That Allows Anaerobic Degradation in Contact with the Landfill

3. Results and Discussion

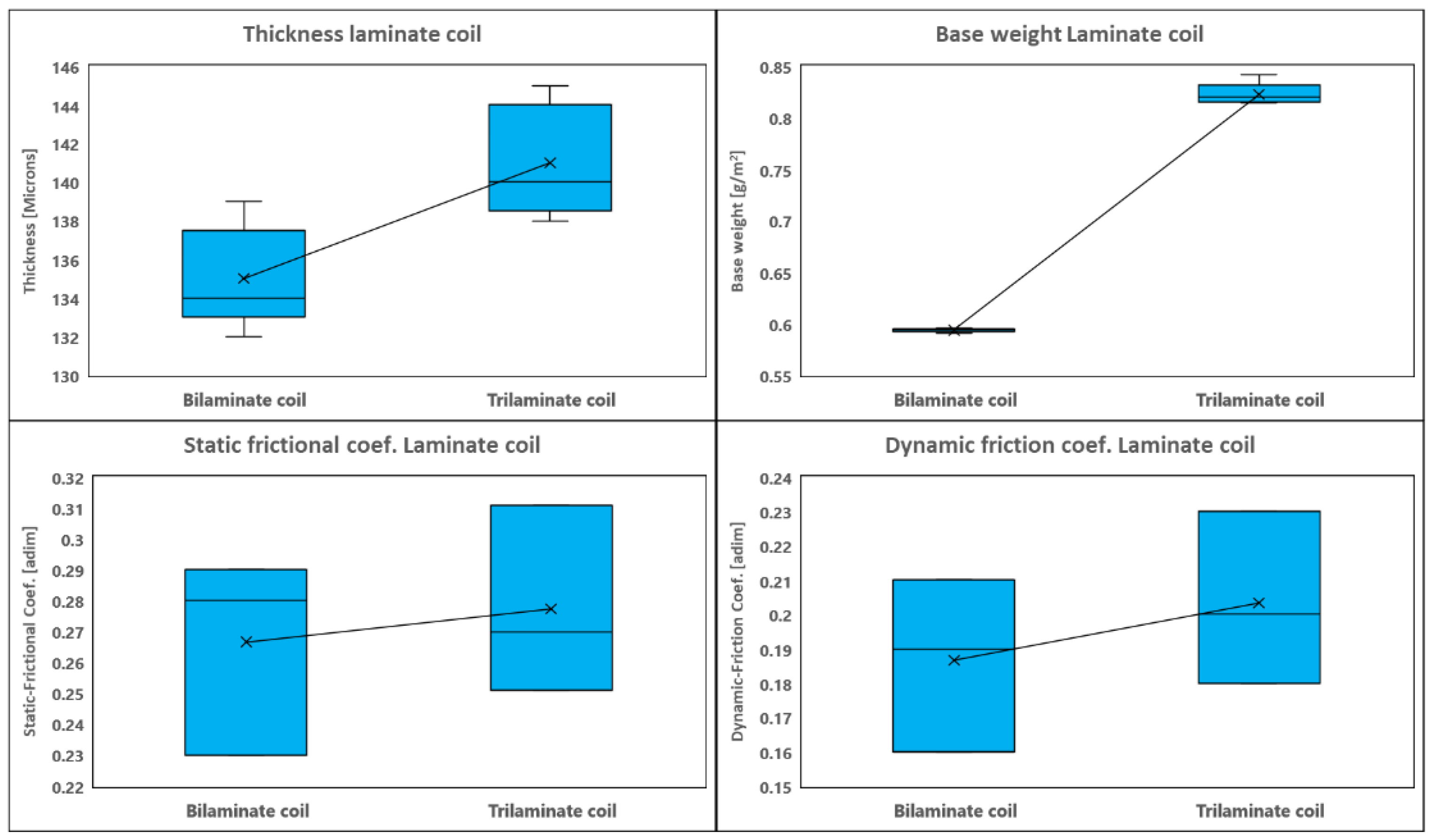

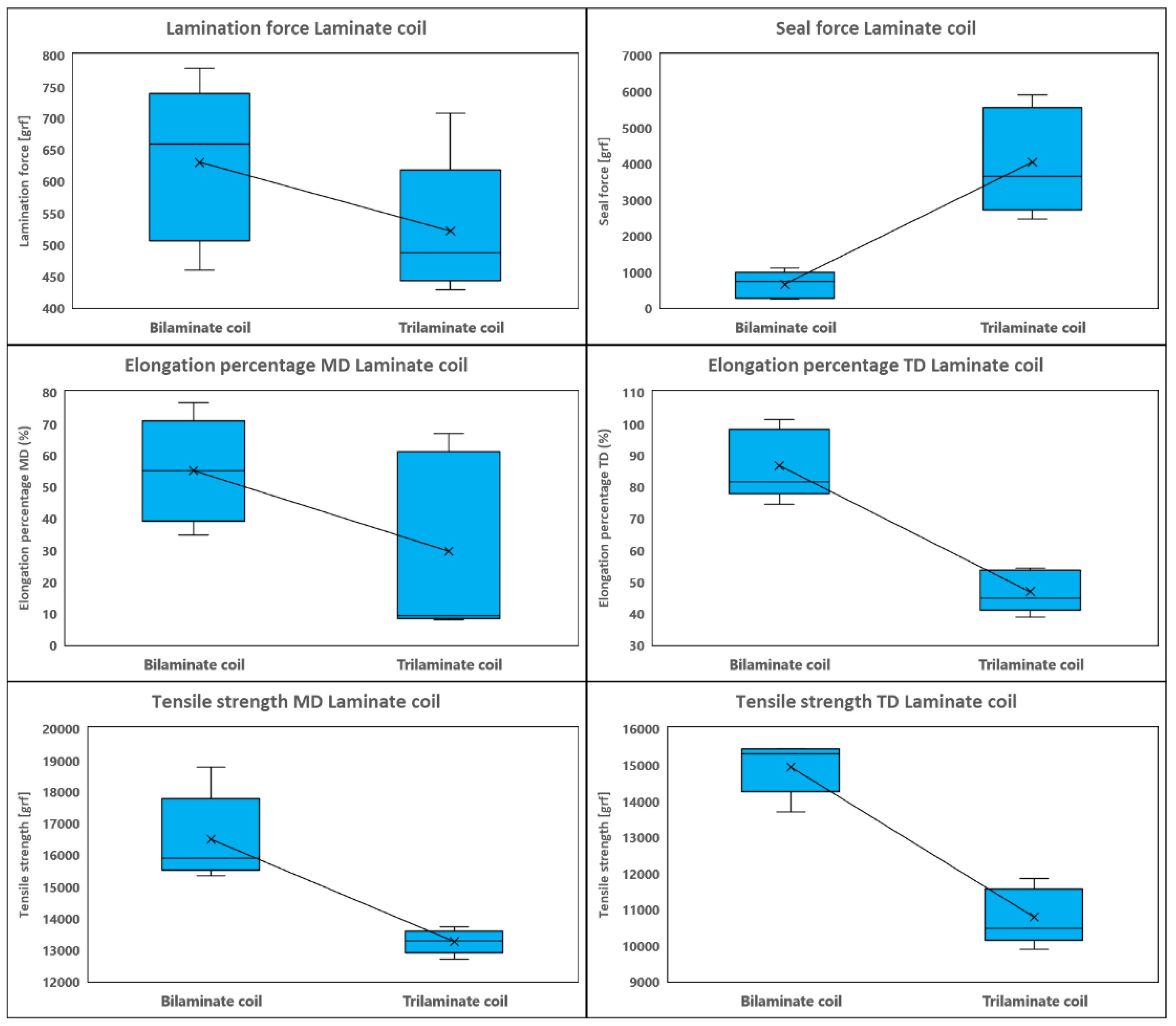

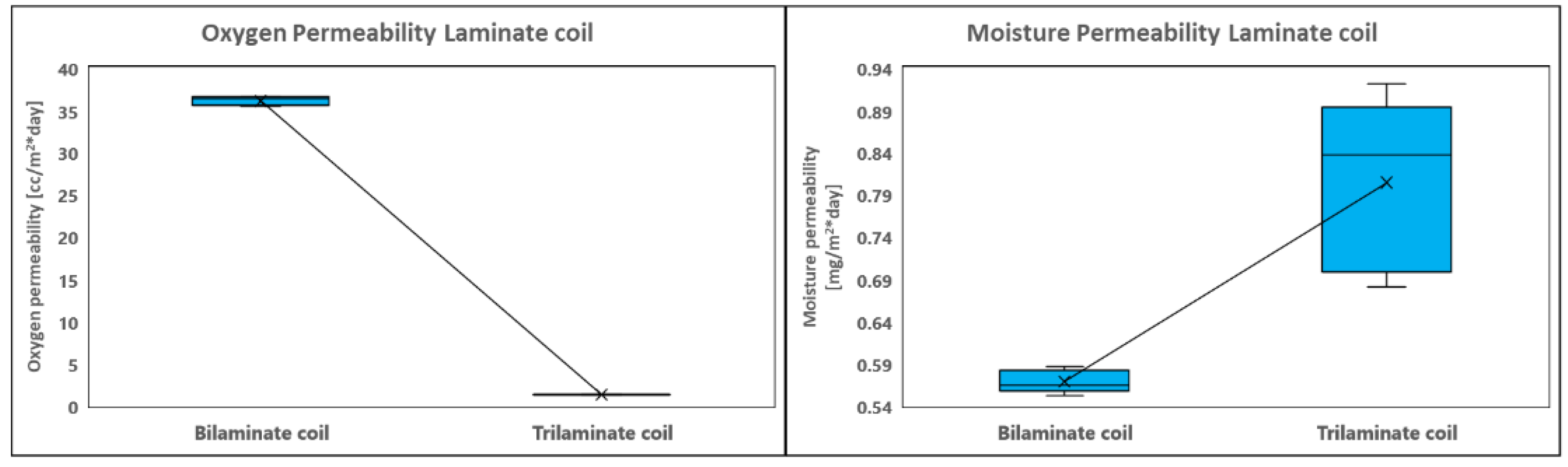

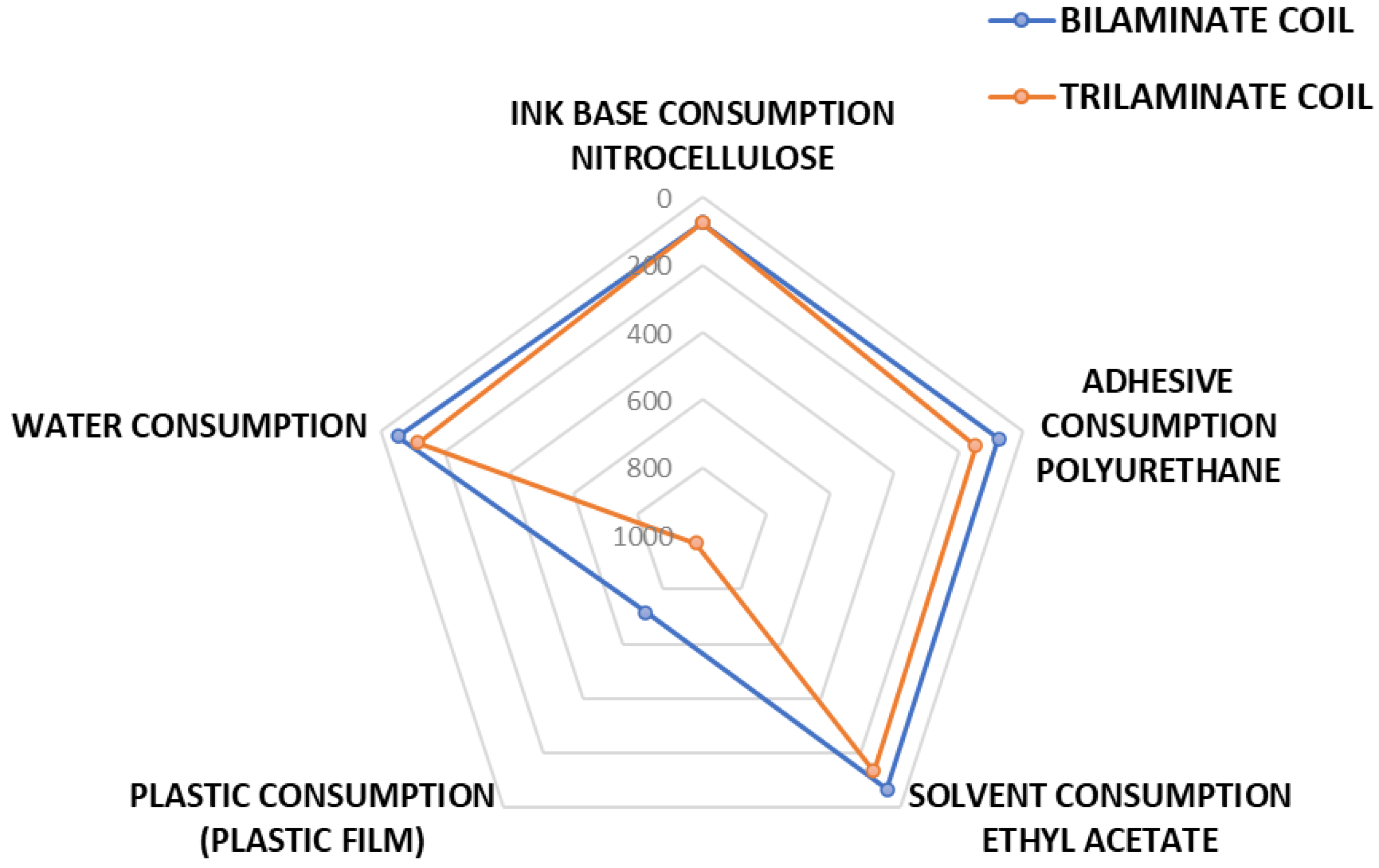

3.1. Redesign and Reduction of Lamination Layers in Trilaminate Structure for Flexible Packaging in the Food Sector, Laminated Coil Type, and Implementation of Monomaterial Structure

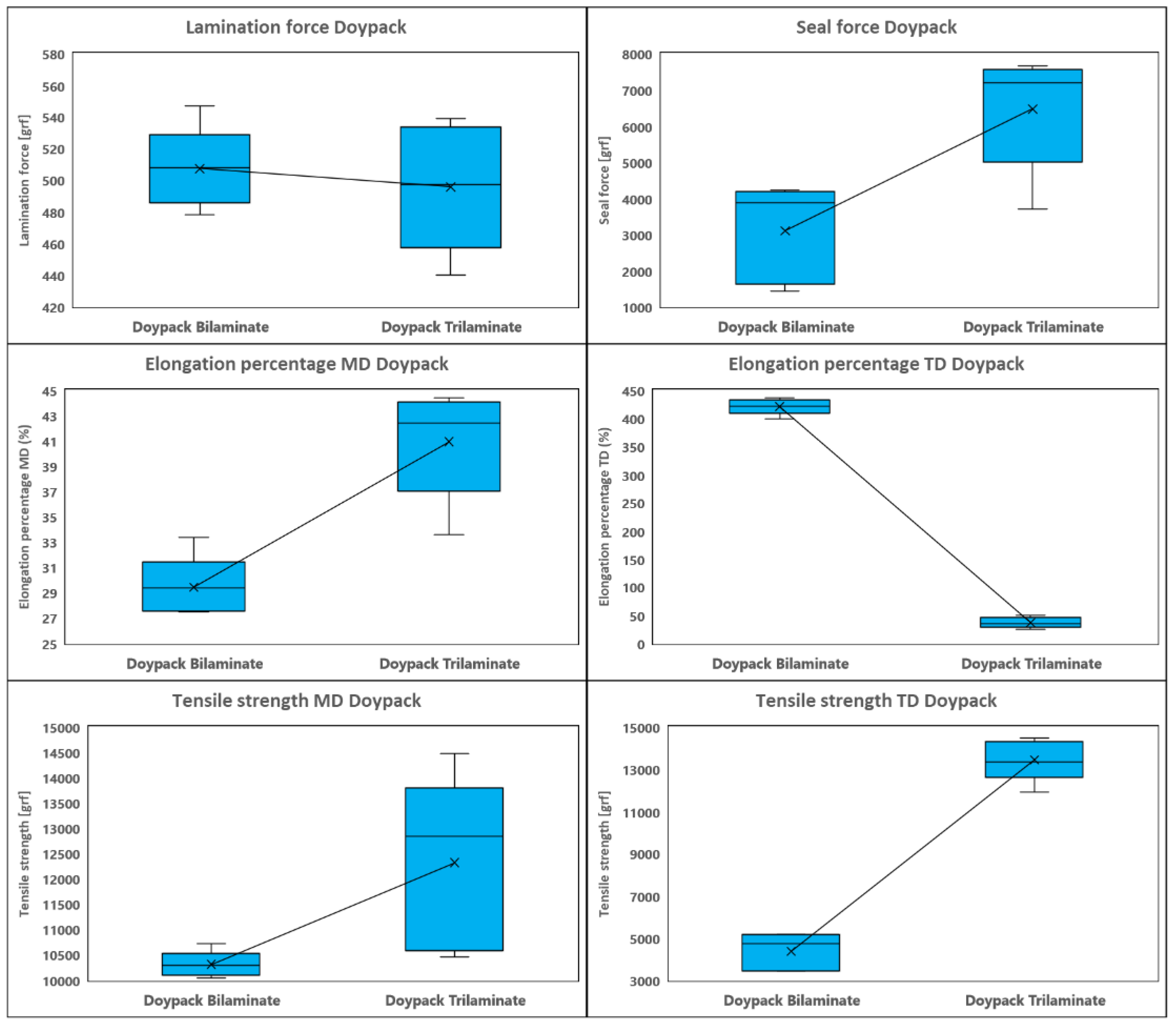

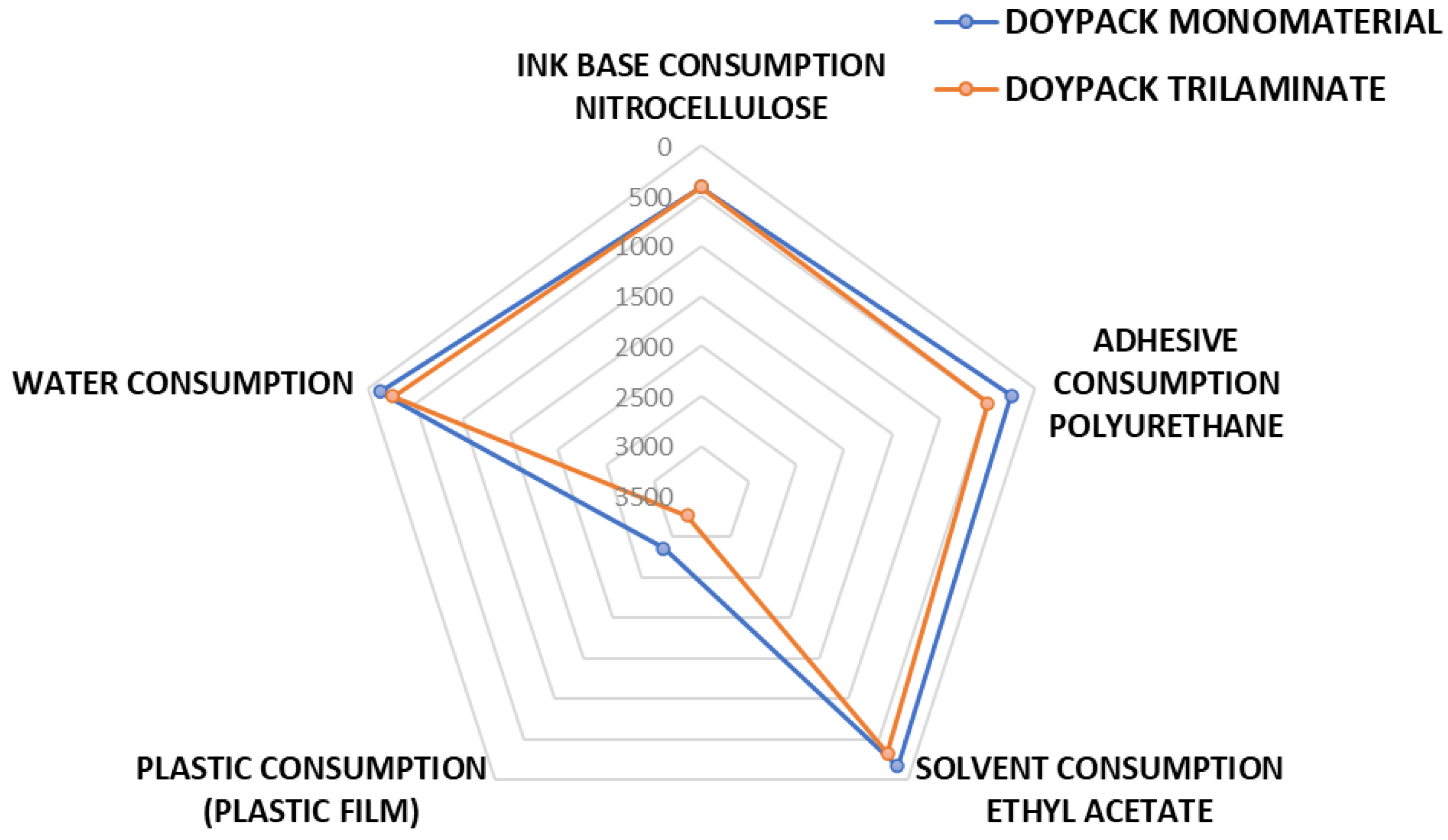

3.2. Redesign of Flexible Food Packaging in Doypack Format with a Three-Layer and Multi-Polymeric Structure to a Monomaterial Using Polyethylene as the Base Polymer

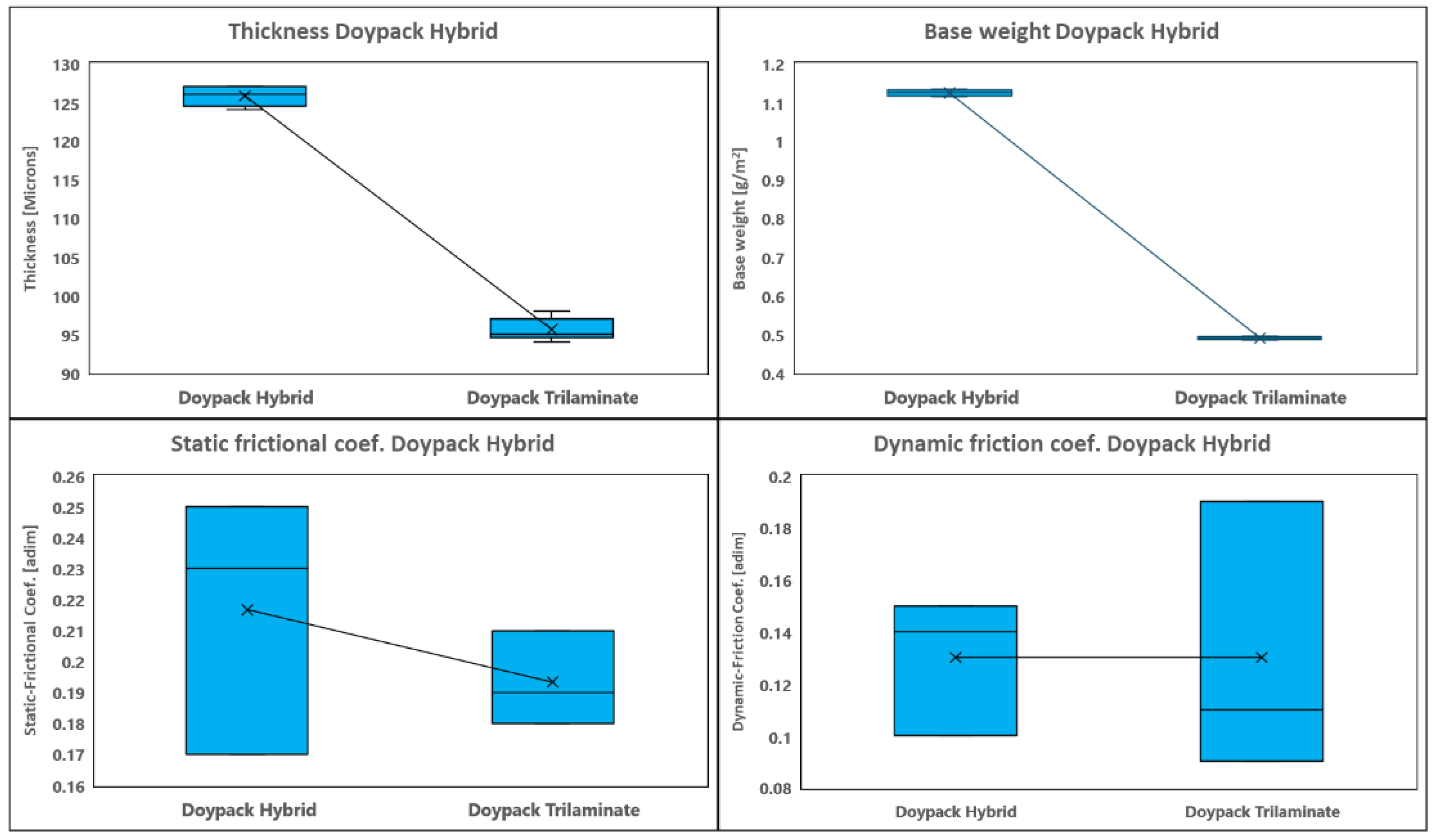

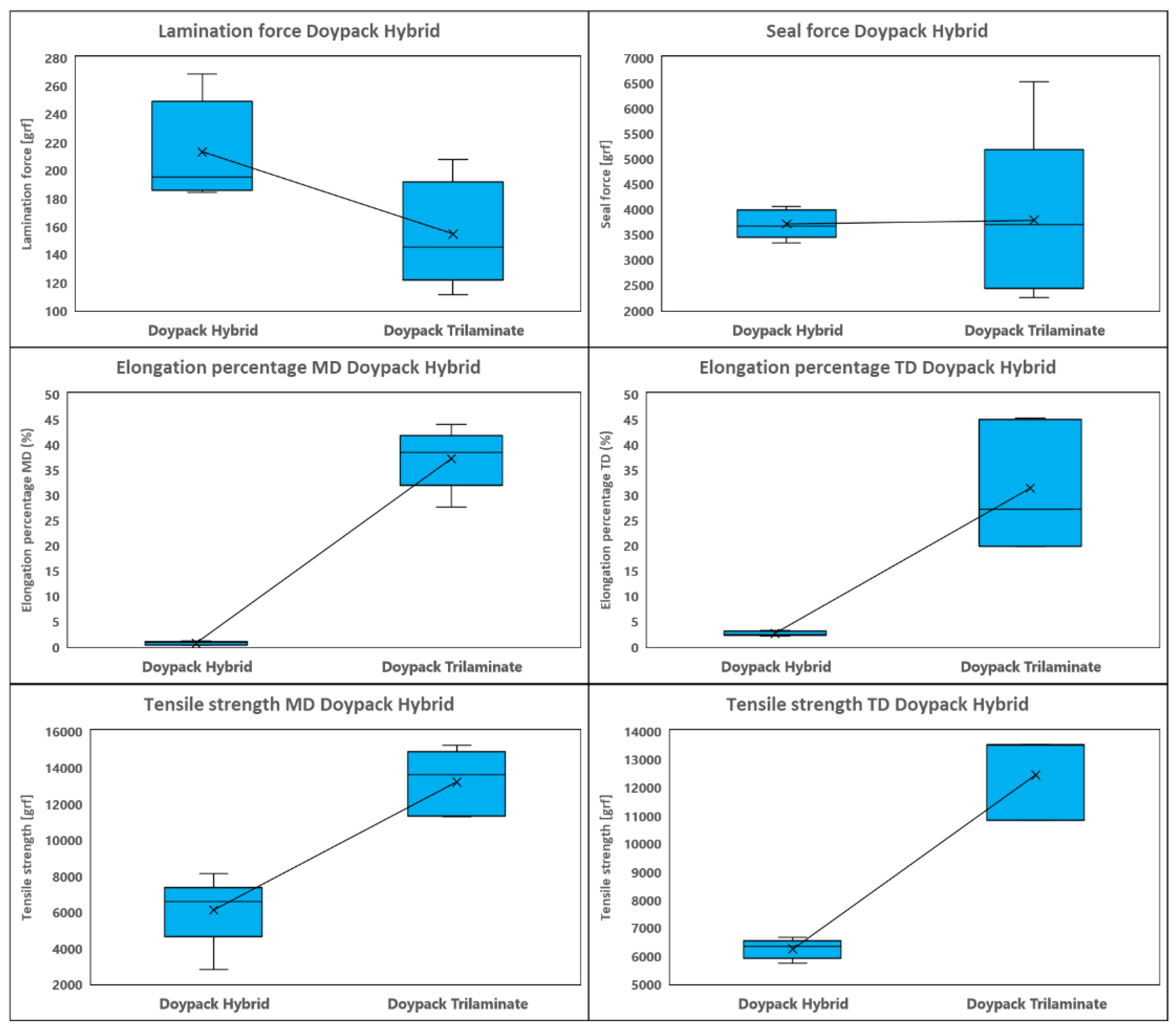

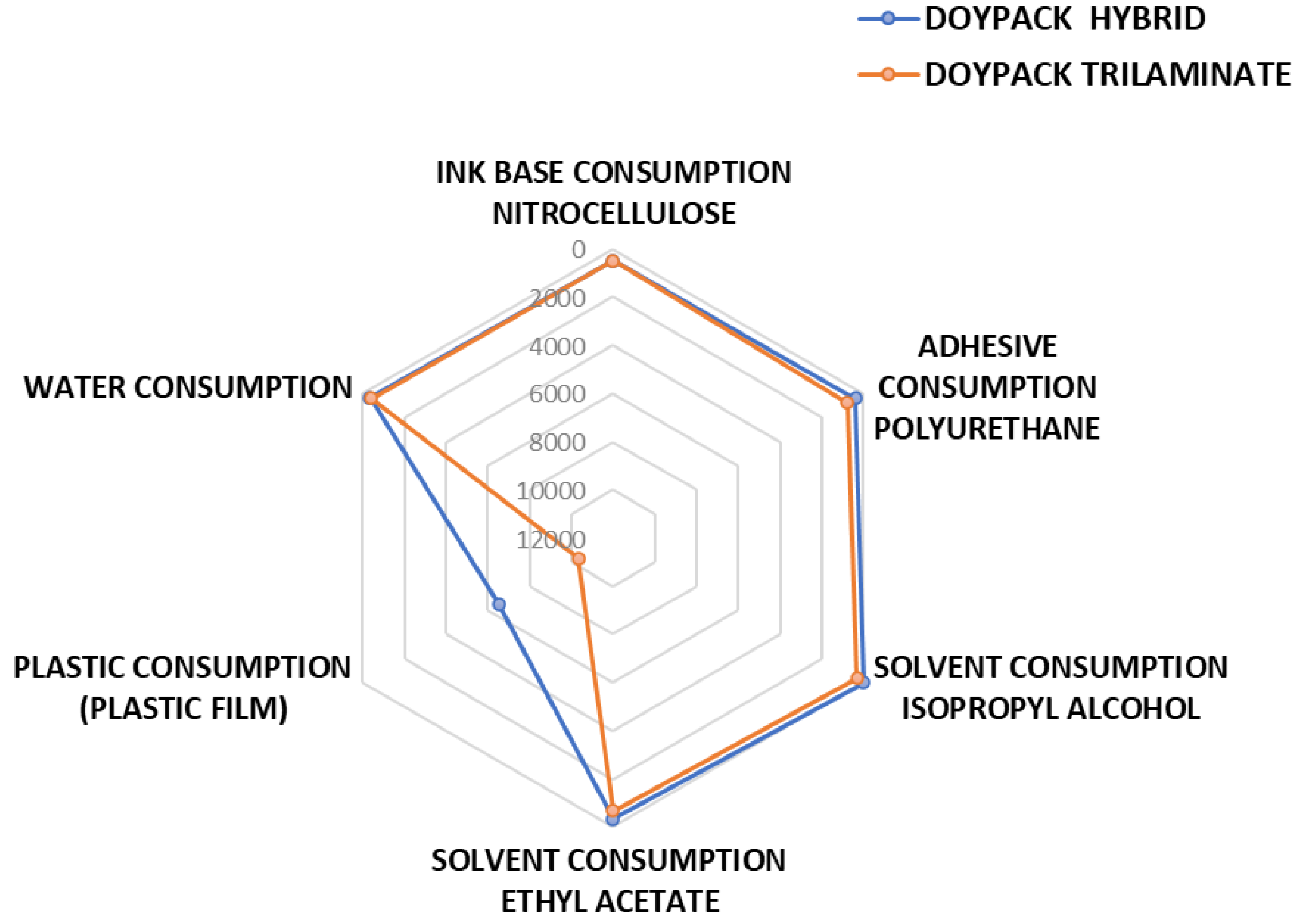

3.3. Redesign of Trilaminate Flexible Packaging to a Hybrid Paper Packaging with a High Barrier Plastic and an Additive That Allows Anaerobic Degradation in the Presence of a Landfill

4. Conclusions

Author Contributions

Data Availability Statement

Acknowledgments

Conflicts of Interest

References

- Azevedo, A.G.; Barros, C.; Miranda, S.; Machado, A.V.; Castro, O.; Silva, B.; Saraiva, M.; Silva, A.S.; Pastrana, L.; Carneiro, O.S.; et al. Active Flexible Films for Food Packaging: A Review. Polymers 2022, 14, 2442. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Sani, I.K.; Masoudpour-Behabadi, M.; Sani, M.A.; Motalebinejad, H.; Juma, A.S.M.; Asdagh, A.; Eghbaljoo, H.; Khodaei, S.M.; Rhim, J.-W.; Mohammadi, F. Value-Added Utilization of Fruit and Vegetable Processing by-Products for the Manufacture of Biodegradable Food Packaging Films. Food Chemistry 2023, 405, 134964. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Vlad-Bubulac, T.; Hamciuc, C.; Rîmbu, C.M.; Aflori, M.; Butnaru, M.; Enache, A.A.; Serbezeanu, D. Fabrication of Poly(Vinyl Alcohol)/Chitosan Composite Films Strengthened with Titanium Dioxide and Polyphosphonate Additives for Packaging Applications. Gels 2022, 8, 474. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Chandrappa, R.; Das, D.B. Solid Waste Management; Springer International Publishing, 2024; ISBN 978-3-031-50441-9.

- Nkwachukwu, O.; Chima, C.; Ikenna, A.; Albert, L. Focus on Potential Environmental Issues on Plastic World towards a Sustainable Plastic Recycling in Developing Countries. International Journal of Industrial Chemistry 2013, 4, 34. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Kalpana, S.; Priyadarshini, S.R.; Leena, M.M.; Moses, J.A.; Anandharamakrishnan, C. Intelligent Packaging: Trends and Applications in Food Systems. Trends in Food Science & Technology 2019, 93, 145–157. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Letcher, T.M. Plastic Waste and Recycling; Elsevier, 2020; ISBN 978-0-12-817880-5.

- Bharadwaj, B.; Subedi, M.N.; Rai, R.K. Retailer’s Characteristics and Compliance with the Single-Use Plastic Bag Ban. Sustainability Analytics and Modeling 2023, 3, 100019. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Kumar, R.; Verma, A.; Shome, A.; Sinha, R.; Sinha, S.; Jha, P.K.; Kumar, R.; Kumar, P.; Shubham; Das, S.; et al. Impacts of Plastic Pollution on Ecosystem Services, Sustainable Development Goals, and Need to Focus on Circular Economy and Policy Interventions. Sustainability 2021, 13, 9963. [CrossRef]

- Lopez, O.; Garcia, M.A.; Villar, M.A.; Gentili, A.; Rodriguez, M.S.; Albertengo, L. Thermo-Compression of Biodegradable Thermoplastic Corn Starch Films Containing Chitin and Chitosan. LWT - Food Science and Technology 2014, 57, 106–115. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Trinh, B.M.; Chang, B.P.; Mekonnen, T.H. The Barrier Properties of Sustainable Multiphase and Multicomponent Packaging Materials: A Review. Progress in Materials Science 2023, 133, 101071. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Lebreton, L.; Andrady, A. Future Scenarios of Global Plastic Waste Generation and Disposal. Palgrave Commun 2019, 5, 6. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Oktavilia, S.; Hapsari, M.; Firmansyah; Setyadharma, A.; Wahyuningsum, I.F.S. Plastic Industry and World Environmental Problems. E3S Web of Conferences 2020, 202, 05020. [CrossRef]

- Foschi, E.; Zanni, S.; Bonoli, A. Combining Eco-Design and LCA as Decision-Making Process to Prevent Plastics in Packaging Application. Sustainability 2020, 12, 9738. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Dunn, T. Manufacturing Flexible Packaging: Materials, Machinery, and Techniques; Elsevier, 2015; ISBN 978-0-323-26436-5.

- Sadiq, M.; Ngo, T.Q.; Pantamee, A.A.; Khudoykulov, K.; Thi Ngan, T.; Tan, L.P. The Role of Environmental Social and Governance in Achieving Sustainable Development Goals: Evidence from ASEAN Countries. Economic Research-Ekonomska Istraživanja 2023, 36, 170–190. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Roorda, N. Roorda, N. Fundamentals of Sustainable Development; Routledge, 2020; ISBN 978-1-00-305251-7.

- Wen, H.; Liang, W.; Lee, C.-C. China’s Progress toward Sustainable Development in Pursuit of Carbon Neutrality: Regional Differences and Dynamic Evolution. Environmental Impact Assessment Review 2023, 98, 106959. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Vink, E.T.H.; Rábago, K.R.; Glassner, D.A.; Gruber, P.R. Applications of Life Cycle Assessment to NatureWorksTM Polylactide (PLA) Production. Polymer Degradation and Stability 2003, 80, 403–419. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Rogers, P.P.; Jalal, K.F.; Boyd, J.A. An Introduction to Sustainable Development; 0 ed.; Routledge, 2012; ISBN 978-1-136-57177-0.

- Geissdoerfer, M.; Morioka, S.N.; De Carvalho, M.M.; Evans, S. Business Models and Supply Chains for the Circular Economy. Journal of Cleaner Production 2018, 190, 712–721. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Lewandowski, M. Designing the Business Models for Circular Economy—Towards the Conceptual Framework. Sustainability 2016, 8, 43. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Jambeck, J.R.; Geyer, R.; Wilcox, C.; Siegler, T.R.; Perryman, M.; Andrady, A.; Narayan, R.; Law, K.L. Plastic Waste Inputs from Land into the Ocean. Science 2015, 347, 768–771. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Lamba, H.K.; Kumar, N.S.; Dhir, S. Circular Economy and Sustainable Development: A Review and Research Agenda. IJPPM 2024, 73, 497–522. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Khuc, Q.; Dang, T.; Tran, M.; Nguyen, D.; Nguyen, T.; Pham, P.; Tran, T. Household-Level Strategies to Tackle Plastic Waste Pollution in a Transitional Country. Urban Science 2023, 7, 20. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Rochman, C.M.; Tahir, A.; Williams, S.L.; Baxa, D.V.; Lam, R.; Miller, J.T.; Teh, F.-C.; Werorilangi, S.; Teh, S.J. Anthropogenic Debris in Seafood: Plastic Debris and Fibers from Textiles in Fish and Bivalves Sold for Human Consumption. Sci Rep 2015, 5, 14340. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Biopolymers for Food Design; Grumezescu, A.M., Holban, A.M., Eds.; Handbook of food bioengineering / edited by Alexandru Mihai Grumezescu, Alina Maria Holban; Academic Press, an imprint of Elsevier: London San Diego Cambridge, MA Oxford, 2018; ISBN 978-0-12-811449-0.

- Uehara, G.A.; França, M.P.; Canevarolo Junior, S.V. Recycling Assessment of Multilayer Flexible Packaging Films Using Design of Experiments. Polímeros 2015, 25, 371–381. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Sid, S.; Mor, R.S.; Kishore, A.; Sharanagat, V.S. Bio-Sourced Polymers as Alternatives to Conventional Food Packaging Materials: A Review. Trends in Food Science & Technology 2021, 115, 87–104. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Bauer, A.-S.; Tacker, M.; Uysal-Unalan, I.; Cruz, R.M.S.; Varzakas, T.; Krauter, V. Recyclability and Redesign Challenges in Multilayer Flexible Food Packaging—A Review. Foods 2021, 10, 2702. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Sharma, A.; Vijayakumar, P.S.; Prabhakar, E.P.K.; Kumar, R. Nanotechnology Applications for Food Safety and Quality Monitoring; Elsevier, 2023; ISBN 978-0-323-85791-8.

- Zhao, X.; Cornish, K.; Vodovotz, Y. Narrowing the Gap for Bioplastic Use in Food Packaging: An Update. Environ. Sci. Technol. 2020, 54, 4712–4732. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Lackner, M.; Mukherjee, A.; Koller, M. What Are “Bioplastics”? Defining Renewability, Biosynthesis, Biodegradability, and Biocompatibility. Polymers 2023, 15, 4695. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Karan, H.; Funk, C.; Grabert, M.; Oey, M.; Hankamer, B. Green Bioplastics as Part of a Circular Bioeconomy. Trends in Plant Science 2019, 24, 237–249. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Zhu, Z.; Liu, W.; Ye, S.; Batista, L. Packaging Design for the Circular Economy: A Systematic Review. Sustainable Production and Consumption 2022, 32, 817–832. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Mangaraj, S.; Yadav, A.; Bal, L.M.; Dash, S.K.; Mahanti, N.K. Application of Biodegradable Polymers in Food Packaging Industry: A Comprehensive Review. J Package Technol Res 2019, 3, 77–96. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Berkane, I.; Cabanes, A.; Horodytska, O.; Aracil, I.; Fullana, A. The Delamination of Metalized Multilayer Flexible Packaging Using a Microperforation Technique. Resources, Conservation and Recycling 2023, 189, 106744. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Siracusa, V.; Rocculi, P.; Romani, S.; Rosa, M.D. Biodegradable Polymers for Food Packaging: A Review. Trends in Food Science & Technology 2008, 19, 634–643. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Singh, B.; Sharma, N. Mechanistic Implications of Plastic Degradation. Polymer Degradation and Stability 2008, 93, 561–584. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Abdelmoez, W.; Dahab, I.; Ragab, E.M.; Abdelsalam, O.A.; Mustafa, A. Bio- and Oxo-degradable Plastics: Insights on Facts and Challenges. Polymers for Advanced Techs 2021, 32, 1981–1996. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Alhanish, A.; Abu Ghalia, M. Developments of Biobased Plasticizers for Compostable Polymers in the Green Packaging Applications: A Review. Biotechnology Progress 2021, 37, e3210. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Spaccini, R.; Todisco, D.; Drosos, M.; Nebbioso, A.; Piccolo, A. Decomposition of Bio-Degradable Plastic Polymer in a Real on-Farm Composting Process. Chem. Biol. Technol. Agric. 2016, 3, 4. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Avella, M.; Bonadies, E.; Martuscelli, E.; Rimedio, R. European Current Standardization for Plastic Packaging Recoverable through Composting and Biodegradation. Polymer Testing 2001, 20, 517–521. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Al-Salem, S.M.; Lettieri, P.; Baeyens, J. Recycling and Recovery Routes of Plastic Solid Waste (PSW): A Review. Waste Management 2009, 29, 2625–2643. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Briassoulis, D.; Hiskakis, M.; Babou, E. Technical Specifications for Mechanical Recycling of Agricultural Plastic Waste. Waste Management 2013, 33, 1516–1530. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Barlow, C.Y.; Morgan, D.C. Polymer Film Packaging for Food: An Environmental Assessment. Resources, Conservation and Recycling 2013, 78, 74–80. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Hopewell, J.; Dvorak, R.; Kosior, E. Plastics Recycling: Challenges and Opportunities. Phil. Trans. R. Soc. B 2009, 364, 2115–2126. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Kubiczek, J.; Derej, W.; Hadasik, B.; Matuszewska, A. Chemical Recycling of Plastic Waste as a Mean to Implement the Circular Economy Model in the European Union. Journal of Cleaner Production 2023, 406, 136951. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Vasudeo, R.A.; Abitha, V.K.; Vinayak, K.; Jayaja, P.; Gaikwad, S. Sustainable Development Through Feedstock Recycling of Plastic Wastes. Macromolecular Symposia 2016, 362, 39–51. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Soares, C.T.D.M.; Ek, M.; Östmark, E.; Gällstedt, M.; Karlsson, S. Recycling of Multi-Material Multilayer Plastic Packaging: Current Trends and Future Scenarios. Resources, Conservation and Recycling 2022, 176, 105905. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Morris, B.A. The Science and Technology of Flexible Packaging: Multilayer Films from Resin and Process to End Use; Plastics design library (PDL) handbook series; Second edition.; William Andrew: Kidlington, Oxford Cambridge, MA, 2022; ISBN 978-0-323-85574-7.

- Selke, S.E.; Hernandez, R.J. Packaging: Polymers in Flexible Packaging. In Encyclopedia of Materials: Science and Technology; Elsevier, 2001; pp. 6652–6656.

- Mekonnen, T.; Mussone, P.; Khalil, H.; Bressler, D. Progress in Bio-Based Plastics and Plasticizing Modifications. J. Mater. Chem. A 2013, 1, 13379. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- James, B.D.; Ward, C.P.; Hahn, M.E.; Thorpe, S.J.; Reddy, C.M. Minimizing the Environmental Impacts of Plastic Pollution through Ecodesign of Products with Low Environmental Persistence. ACS Sustainable Chemistry & Engineering 2024, 12, 1185–1194. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Doorsselaer, K.V. The Role of Ecodesign in the Circular Economy. In Circular Economy and Sustainability; Elsevier, 2022; pp. 189–205.

- FBR Sustainable Chemistry & Technology; Thoden Van Velzen, U.; De Weert, L.; Molenveld, K. Flexible Laminates within the Circular Economy; Wageningen Food & Biobased Research: Wageningen, 2020.

- ASTM International Committee, D6988-21. Guide for Determination of Thickness of Plastic Film Test Specimens 2021.

- ASTM International Committee, F88/F88M-23. Test Method for Seal Strength of Flexible Barrier Materials 2023.

- ASTM International Committee, D882-18. Test Method for Tensile Properties of Thin Plastic Sheeting 2018.

- ASTM International Committee, D1894-14. Test Method for Static and Kinetic Coefficients of Friction of Plastic Film and Sheeting 2023.

- ASTM International Committee, D3985-24. Test Method for Oxygen Gas Transmission Rate Through Plastic Film and Sheeting Using a Coulometric Sensor 2024.

- ASTM International Committee, F1249-20. Test Method for Water Vapor Transmission Rate Through Plastic Film and Sheeting Using a Modulated Infrared Sensor 2020.

- ASTM International Committee, D3078-02. Test Method for Determination of Leaks in Flexible Packaging by Bubble Emission 2021.

| Current structure | Thickness (microns) | Base weight (g/m2) | Variation% |

|---|---|---|---|

| Natural BOPP (bi-oriented polypropylene) | 20 | 18.1 | 10% |

| Ink | 3 | 3 | 5% |

| Adhesive | 3 | 3 | 5% |

| Metalized polyester | 12 | 16.8 | 10% |

| Adhesive | 3 | 3 | 5% |

| Low-density polyethylene | 40 | 38.4 | 10% |

| Total | 81 | 82.3 | 10% |

| Quality requirement | Units | International Standards | Packaging type |

|---|---|---|---|

| Thickness | microns | ASTM D6988-21 [57] | Laminated coil/Doypack |

| Base weight | g/m2 | N/A | Laminated coil/Doypack |

| Lamination strength | gf | ASTM F88/F88M-23 [58] | Laminated coil/Doypack |

| Seal strength | gf | ASTM F88/F88M-23 [58] | Laminated coil/Doypack |

| Tensile strength | gf | ASTM D882-18 [59] | Laminated coil/Doypack |

| Elongation percentage | mm | ASTM D882-18 [59] | Laminated coil/Doypack |

| Coefficient of friction | Non dimensional | ASTM D1894-14 [60] | Laminated coil/Doypack |

| Oxygen permeability | cc/m2·día | ASTM D3985-24 [61] | Laminated coil |

| Water vapor permeability |

mg/m2·día | ASTM F1249-20 [62] | Laminated coil |

| Drop packing resistance | Non dimensional | N/A | Doypack |

| Vacuum tightness test | Non dimensional | ASTM D3078-02 [63] | Doypack |

| Air pressure packing resistance | Non dimensional | N/A | Doypack |

| Shelf life | Months | N/A | Laminated coil/Doypack |

| Proposed structure | Thickness [microns] | Base weight [g/m2] | Variation % |

|---|---|---|---|

| Natural BOPP (bi-oriented polypropylene) | 20 | 18.1 | 10% |

| Ink | 3 | 3 | 5% |

| Adhesive | 3 | 3 | 5% |

| Metalized CPP (cast polypropylene) | 40 | 36.4 | 10% |

| Total | 66 | 60.5 | 10% |

| Proposed Structure | Thickness [microns] | Base weight [g/m2] | Variation % |

|---|---|---|---|

| Natural polyester | 12 | 16.8 | 10% |

| Ink | 3 | 3 | 5% |

| Adhesive | 3 | 3 | 5% |

| Natural polyester | 12 | 16.8 | 10% |

| Adhesive | 3 | 3 | 5% |

| Low-density polyethylene | 75 | 72 | 10% |

| Total | 108 | 114.6 | 10% |

| Proposed Structure | Thickness [microns] | Base weight [g/m2] | Variation % |

|---|---|---|---|

| Mono-oriented polyethylene (MDO) | 25 | 19.1 | 10% |

| Ink | 3 | 3 | 5% |

| Adhesive | 3 | 3 | 5% |

| Low-density polyethylene | 75 | 72 | 10% |

| Total | 101 | 97.1 | 10% |

| Proposed Structure | Thickness [microns] | Base weight [g/m2] | Variation % |

|---|---|---|---|

| Natural polyester | 12 | 16.8 | 10% |

| Ink | 3 | 3 | 5% |

| Adhesive | 3 | 3 | 5% |

| Natural polyester | 12 | 16.8 | 10% |

| Adhesive | 3 | 3 | 5% |

| Low-density polyethylene | 62.5 | 60 | 10% |

| Total | 95.5 | 102.6 | 10% |

| Proposed Structure | Thickness [microns] | Base weight [g/m2] | Variation % |

|---|---|---|---|

| Cellulose Paper | 50 | 40 | 10% |

| Water-based ink | 3 | 3 | 5% |

| Adhesive | 3 | 3 | 5% |

| Polyethylene coextrusion EVOH + ECO-ONE Additive | 62.5 | 72 | 10% |

| Total | 118.5 | 118 | 10% |

| Quality requirement | Trilaminate Average of measurements |

Bilaminate Average of measurements |

Quality requirement Trilaminate | Average |

|---|---|---|---|---|

| Thickness | 141 microns | 135 microns | 2.9154 | 2.6457 |

| Weight base | 0.8228 g/m2 | 0.5936 g/m² | 0.01118 | 0.001816 |

| Rolling force | 520.6 gf | 629 gf | 110.52 | 125.13 |

| Seal strength | 4011.2 gf | 633.2 gf | 1464.10 | 372.06 |

| Tensile strength | MD: 13236 gf DT:1059 gf | MD: 16482.4 gf TD:14921.6 gf | MD:390.64 TD:777.63 | MD: 430.28 TD: 737.43 |

| Percentage of elongation | MD: 29.482% TD:46.674% | MD: 54.954% TD:86.542% | MD:5.10 TD:6.657 | MD:16.65 TD:11.06 |

| Coefficient of friction | ST: 0.2773 DI: 0.2033 | ST: 0.266 DI: 0.1866 | ST:0.0306 DI:0.0251 | ST:0.0321 DI:0.0251 |

| Oxygen permeability | 1.29531cc/ m²·día | 35.38771 cc/ m²·día | 0.36 | 0.82 |

| Moisture permeability | 0.82589 mg/ m²·día | 0.569552 mg/ m²·día | 0.02 | 0.01 |

| Shelf life (six months) | Pass | Pass | N/A | N/A |

| Quality requirement | Current trilaminate structure for Doypack | Proposed monomaterial structure for Doypack | Trilaminate structure standard deviation | Monomaterial structure standard deviation |

|---|---|---|---|---|

| Thickness | 106 microns | 109.4 microns | 2.236 | 1.1401 |

| Base weight | 1.2048 g/m² | 1.0520 g/m² | 0.131 | 0.0073 |

| Rolling force | 495.6 gf | 507.2 gf | 40.290 | 25.72 |

| Seal strength | 6461.2 gf | 3095.2 gf | 1632.23 | 1358.28 |

| Tensile strength | MD: 12319.4 gf TD: 13449.4 gf | MD:10306.8 gf TD:4368.2 gf | MD: 1707.37 TD: 991.21 | MD:258.26 ST: 881.70 |

| Elongation percentage | MD: 40.924% TD: 36.73% | MD: 29.442% TD:420.832% | MD: 4.353 TD: 9.527 | MD:2.387 ST:14.270 |

| Friction coefficient | ST: 0.3266 DI: 0.0966 | ST: 0.2233 DI: 0.0533 | ST: 0.0750 DI: 0.0351 | ST: 0.0611 DI: 0.020 |

| Packaging drop test | 5/5 | 5/5 | N/A | N/A |

| Vacuum packaging tightness test | 3/3 | 3/3 | N/A | N/A |

| Packaging air pressure test | 5/5 | 5/5 | N/A | N/A |

| Shelf life | Pass | Pass | N/A | N/A |

| Quality requirement | Current trilaminate structure of Doypack-type packaging | Proposed biodegradable hybrid structure of Doypack-type packaging | Trilaminate structure standard deviation | Biodegradable Hybrid structure standard deviation |

|---|---|---|---|---|

| Thickness | 95.6 microns | 125.8 microns | 1.51 | 1.30 |

| Base weight | 1.08 g/m2 | 1.1238 g/m2 | 0.0037 | 0.0079 |

| Rolling force | 154.2 gf | 212.6 gf | 37.77 | 35.78 |

| Seal strength | 3779.4 gf | 3700.4 gf | 1678.26 | 284.59 |

| Tensile strength | SM:13162.4 gf DT:12420.8 gf | SM:6074 gf TD:6229.4 gf | MD: 1803.5 TD: 1461.34 | MD:1903.2 ST: 344.33 |

| Elongation percentage | SM:37.124% TD:31.346% | SM:0.628% TD:2.564% | MD: 6.052 TD: 12.74 | MD:0.366 ST:0.488 |

| Friction coefficient | ES: 0.19 DI: 0.13 | ES: 0.2166 DI: 0.13 | ST: 0.015 DI: 0.052 | ST: 0.041 DI: 0.026 |

| Packaging drop test | 5/5 | 5/5 | N/A | N/A |

| Vacuum packaging tightness test | 3/3 | 3/3 | N/A | N/A |

| Packaging air pressure test | 5/5 | 5/5 | N/A | N/A |

| Shelf life | Pass | Pass | N/A | N/A |

Disclaimer/Publisher’s Note: The statements, opinions and data contained in all publications are solely those of the individual author(s) and contributor(s) and not of MDPI and/or the editor(s). MDPI and/or the editor(s) disclaim responsibility for any injury to people or property resulting from any ideas, methods, instructions or products referred to in the content. |

© 2024 by the authors. Licensee MDPI, Basel, Switzerland. This article is an open access article distributed under the terms and conditions of the Creative Commons Attribution (CC BY) license (http://creativecommons.org/licenses/by/4.0/).