1. Introduction

Cellulose is the most abundant biopolymer on earth and one of the main components of the cell wall of plants [

1,

2,

3]. It is a linear β–1,4–linked glucose unit (C

6H

10O

5)n [

4]. It is produced by various microorganisms, such as fungi, bacteria, algae, and animals, such as tunicates [

5]. Cellulose presents some characteristics, such as low cost, renewable material, sustainability, biodegradability, biocompatibility, and non-toxicity [

6].

Otherwise, cellulose with dimensions between 1 and 100 nm is considered nanostructured. Nanocellulose (NC) possesses several advantageous characteristics, such as excellent mechanical properties, including an axial stiffness of about 130 GPa, a low thermal expansion coefficient of about 1 ppm/K, as well as electrical properties, a low density of about 1.5 g/cm³, good transparency, and is rich in hydroxyl groups that allow chemical modifications useful for many applications [

7,

8]. Furthermore, NC possesses magnetic properties, is lightweight, and has promising optical properties [

9,

10,

11]. These properties have enabled the use of nanocellulose in different applications, such as water purification, food packaging, food additives, functional food, stabilizing agents, encapsulating agents, and coating material [

9,

12]. However, one of the key elements necessary for nanocellulose to be widely adopted is developing sustainable, efficient, and economically viable production methods to meet the growing demand [

13].

NC has been obtained through chemical methods, such as acid hydrolysis, mechanical, biological, and bacteriological methods, including enzymatic hydrolysis and bacterial nanocellulose [

7,

14,

15]. NC's performance, properties, and size depend on the extraction method, where factors such as instrumentation, equipment, inputs, and process conditions are involved [

16]. NC can be classified into three groups: cellulose nanocrystals (CNC), cellulose nanofibers (NFC), and bacterial nanocellulose (BNC) [

12]. Lignocellulosic biomass (LCB) refers to plant biomass, which can be derived from wood and non-wood sources, such as agricultural residues and industrial wastes [

13]. Using non-wood biomass presents an alternative for valorizing waste and contributes to the circular economy and sustainability. On the other hand, bacterial nanocellulose is secreted extracellularly by certain bacteria and has been increasingly studied [

1]. Compared to BNC, lignocellulosic biomass contains, in addition to cellulose, the main components of hemicellulose and lignin [

13].

One of the most widely used methods for NC production is acid hydrolysis, applied to agro-industrial wastes such as sugarcane bagasse, pineapple, wood, pinewood sawdust, and coffee sprouts, among other plant residues [

8,

17]. Due to the composition of these materials, a combination of crystalline and amorphous regions within the polymeric chains of the cellulose is observed, where the amorphous regions are easily hydrolyzed. In contrast, the crystalline regions remain intact [

18]. This process allows the production of cellulose nanocrystals or cellulose microfibrils. This method commonly uses sulfuric acid under controlled temperature, agitation, reaction time, reagent concentration, and pretreatment to remove lignocellulosic material [

17,

19].

On the other hand, BNC is secreted extracellularly as a network of polysaccharides in the form of nano- and micrometer-sized fibers [

14]. It is primarily produced by Gram-negative bacterial species such as

Acetobacter,

Azotobacter,

Rhizobium,

Agrobacterium,

Pseudomonas,

Salmonella, and

Alcaligenes [

7,

14,

20,

21], as well as Gram-positive species such as

Sarcina ventriculi,

Rhodococcus, and

Lactobacillus hilgardii [

22]. The molecular structure of BNC is very similar to lignocellulosic biomass (LCB); however, despite its high crystallinity (about 90%), flexibility, and excellent mechanical properties, BNC exhibits a high degree of purity, being free of lignin, hemicellulose, and pectin [

21,

23,

24]. Its extraction and purification processes are also simpler than chemical methods [

1].

The genus Rhizobia consists of a large group of Gram-negative soil bacteria that enter into symbiosis with host plants, forming nodules and fixing atmospheric nitrogen (N₂) into ammonia (NH₃) [

25,

26].

Rhizobium leguminosarum has three biovars:

R. leguminosarum biovar viciae, biovar phaseoli, and biovar trifolii [

26]. Members of this group are essential from both agricultural and environmental perspectives.

Rhizobium is one of the main genera within the rhizobia, currently comprising 90 recognized species, 48 of which are rhizobia that enter into symbiosis with various legume plants [

25].

Rhizobium leguminosarum biovar

trifolii is an agriculturally essential species in Uruguay, living saprophytically and in symbiosis with plant hosts [

27]. Several studies have explored the potential of

Rhizobium species in synthesizing nanocellulose [

28,

29,

30,

31]. To compare nanocellulose obtained through acid hydrolysis of pineapple peel with that produced via bacterial biosynthesis using

R. leguminosarum biovar

trifolii, we developed a decision matrix considering key process parameters such as reagent consumption, production time, yield, water footprint, purification complexity, and waste generation.

We hypothesize that nanocellulose produced via bacterial biosynthesis using R. leguminosarum biovar trifolii constitutes a more sustainable, water-efficient, and low-toxicity alternative to conventional chemical methods based on acid hydrolysis of lignocellulosic pineapple peel residues.

2. Materials and Methods

The Materials and Methods should be described sufficiently to allow others to replicate and build on the published results. Please note that the publication of your manuscript implies that you must make all materials, data, computer code, and protocols associated with the publication available to readers. Please disclose any restrictions on the availability of materials or information at the submission stage. New methods and protocols should be described in detail, while well-established methods can be briefly described and appropriately cited.

Research manuscripts reporting large datasets deposited in a publicly available database should specify where the data have been deposited and provide the relevant accession numbers. If the accession numbers have not yet been obtained at the time of submission, please state that they will be provided during review. They must be provided before publication.

Interventional studies involving animals or humans and other studies that require ethical approval must list the authority that provided approval and the corresponding ethical approval code.

In this section, where applicable, authors must disclose details of how generative artificial intelligence (GenAI) has been used in this paper (e.g., to generate text, data, or graphics, or to assist in study design, data collection, analysis, or interpretation). The use of GenAI for superficial text editing (e.g., grammar, spelling, punctuation, and formatting) does not need to be declared.

2.1. Materials

Pineapple (Ananas comosus) peel residues were supplied by Congelados y Jugos del Valle Verde, located in Pital de San Carlos, Alajuela, Costa Rica. Sodium hydroxide (NaOH), sulfuric acid (H2SO4), hydrochloric acid (HCl), sodium hypochlorite (NaClO), and ethanol reagents were purchased from Sigma-Aldrich (Steinheim, Germany). Rhizobium leguminosarum biovar trifolii was gently provided by Calister S.A. to the Laboratorio de Técnicas Nucleares Aplicadas a Bioquímica y Biotecnología, Centro de Investigaciones Nucleares-Facultad de Ciencias, Universidad de la República Uruguay, Montevideo, Uruguay.

2.2. Extraction and Purification of Microfibrillated Cellulose by Chemical Method

The procedure described by Camacho et al. [

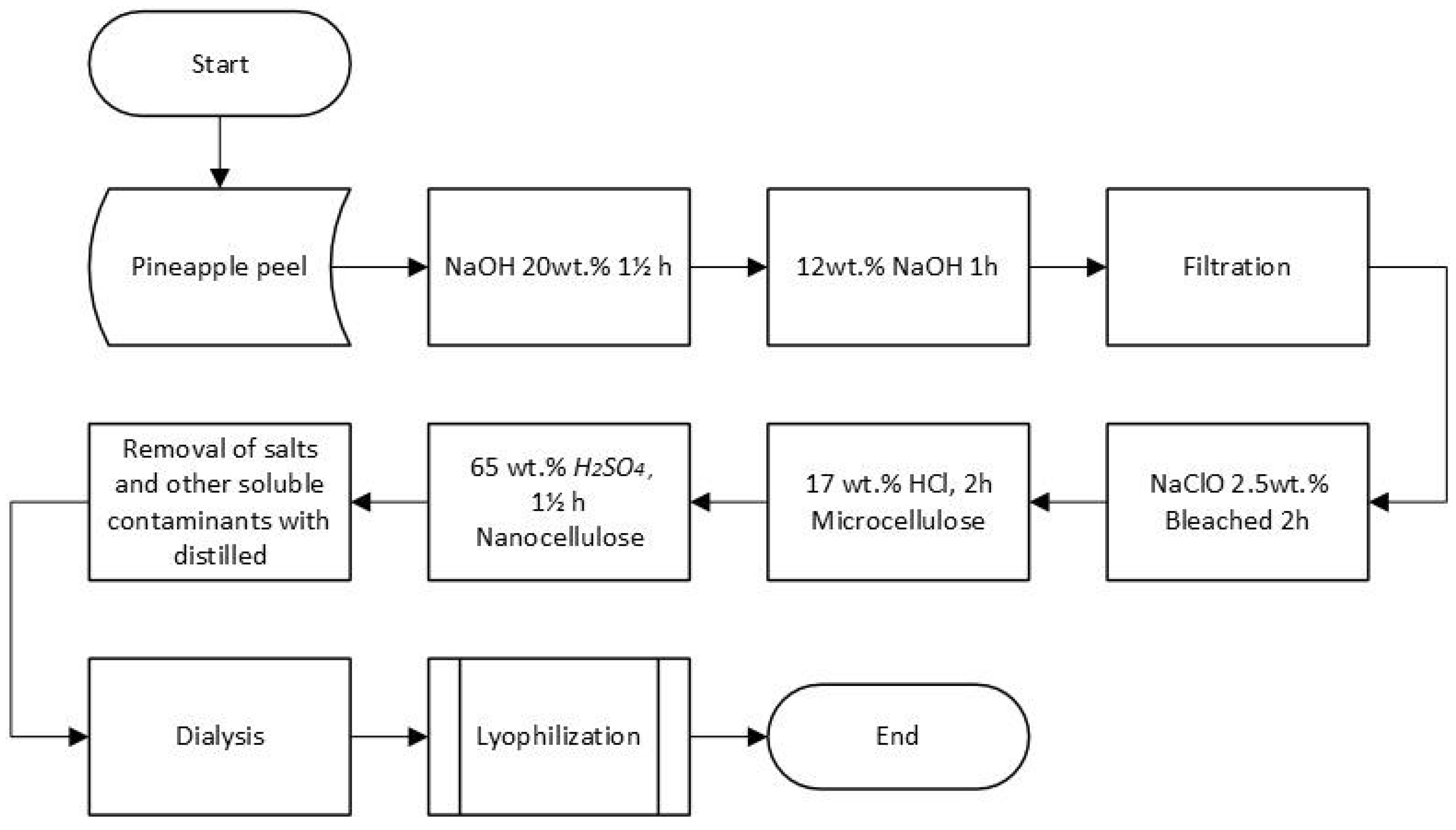

19] was used to obtain the nanocellulose with some modifications. The pineapple peel residues were previously washed with water, and the remains of fruit adhered to them were removed. Subsequently, they were dried in an oven at 50 °C for 24h. The dried pineapple peel was placed in a 20 wt.% NaOH solution for one and a half hours at 80 °C, washed with water until a neutral pH, and filtered to recover the material. Again, it was placed in a NaOH 12 wt.% solution for one hour, at a controlled temperature of 70 °C, and the washing and filtering process was repeated.

Next, the obtained material was bleached in a solution of 2.5 wt.% NaClO at 60 °C for two hours, followed by treatment with 17 wt.% HCl for two hours. The product was washed and filtered under vacuum using a BOECO filter (Germany - grade 389, pore size 5 - 8 µm). Afterwards, the acid hydrolysis was carried out using H2SO4 65 wt% to obtain the nanostructured material. %at 55 °C for 45 min, the sample was centrifuged at 4500 rpm and washed with distilled water until a neutral pH. The hydrolysis process was carried out with constant agitation and in triplicate. The samples were freeze-dried for their characterization.

Figure 1 shows a diagram of the methodology for obtaining nanocellulose from pineapple agroindustrial waste using the chemical method.

2.3. Production of Nanocellulose from Bacterial Cultures of Rhizobium leguminosarum biovar trifolii

2.3.1. Preparation of Bacterial inocula

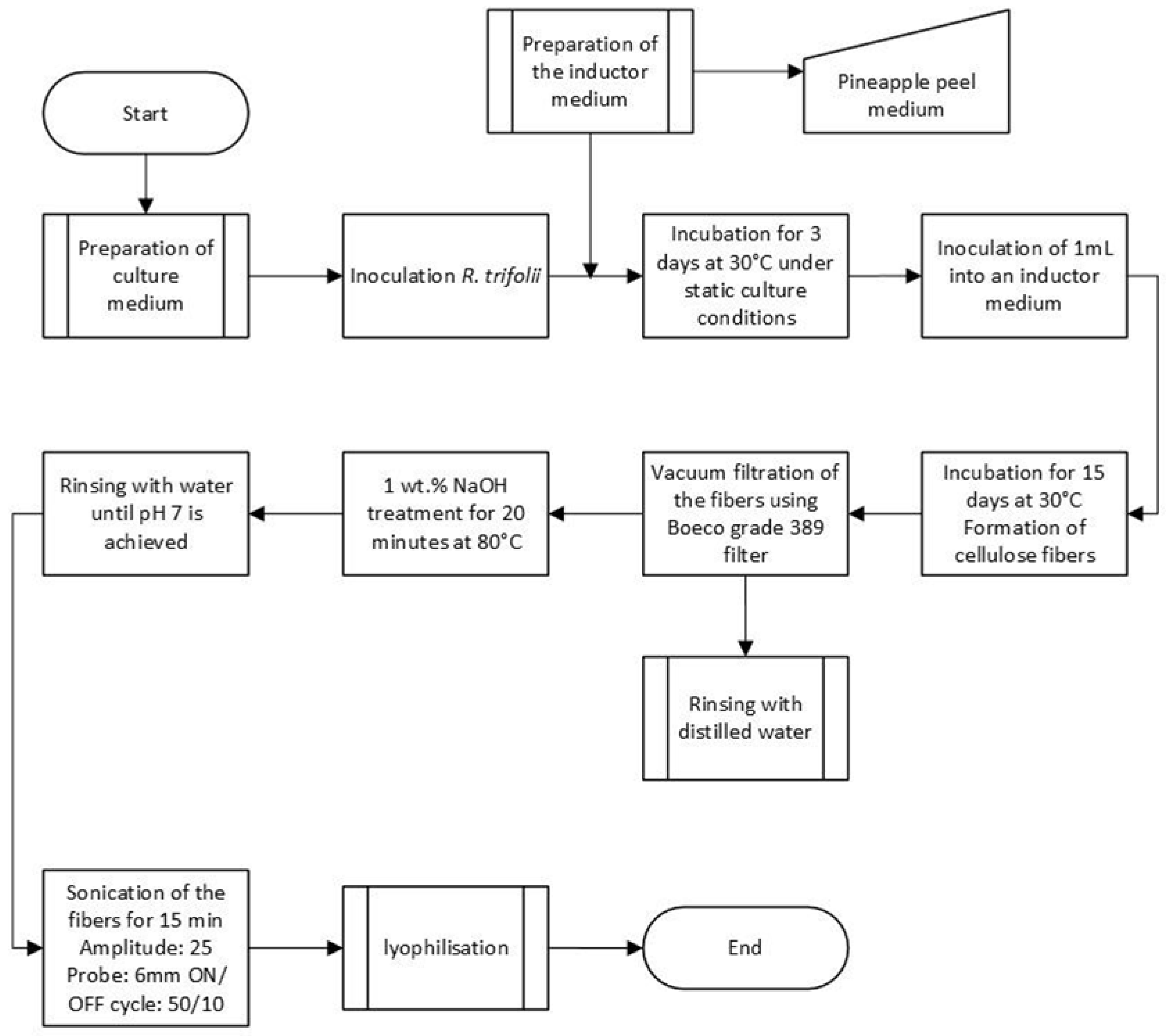

Inocula of Rhizobium leguminosarum biovar trifolii were prepared on yeast extract mannitol medium (YM), which contains 1 g/L yeast extract, 10 g/L mannitol, 0.5 g/L dipotassium phosphate, 0.2 g/L magnesium sulfate, and 0.1 g/L sodium chloride. The pH was adjusted to 6.8. Aliquots of 25 mL of YMA were prepared and inoculated by a loopful of 10-day-old yeast extract mannitol agar medium YMA culture. The inoculated media were incubated at 30 °C for 3 days in the dark. The cultures were done in triplicate.

2.3.2. BNC Production

An aliquot of 1 mL (optical density of 0.1) of the previously prepared R. leguminosarum culture was inoculated into 100 mL of YM medium. In addition, we formulated another culture medium by substituting mannitol with lactose (YLL). This media contained 1 (g/L) yeast Extract, 10 (g/L) lactose, 0.5 (g/L) hydrogenated dipotassium phosphate, 0.2 (g/L) magnesium sulfate, and 0.1 (g/L) sodium chloride. The pH of both culture media was adjusted to 6. The inoculated media were statically incubated at 30 °C for 15 days in the dark. The analyses were done in triplicate.

2.3.3. Harvesting and Purification of the BNC

The BNC films produced by

R. leguminosarum were extracted according to the method described by Ahmed et al. [

32]. A vacuum filtration system was used with a membrane filter (pore size of 5 - 8 µm); the cellulose membranes were poured into the filter and rinsed with distilled water to remove the remaining culture medium and clean the membranes. Subsequently, the membranes were placed in a NaOH solution with a concentration of 0.5% at 80 °C for 20 min, eliminating most bacterial cell debris. The membranes were filtered again and washed with distilled water until a neutral pH was achieved. The membranes were left in aqueous suspension. These tests were performed in triplicate.

Subsequently, aqueous solution of the extracted nanocellulose was exposed to a mechanical deaggregation process with an ultrasonic cleaner, using a 6 mm diameter titanium probe. Ultrasonication was carried out using an amplitude of 25 for 15 minutes, with cycles of 50 seconds ON and 10 seconds OFF, disrupting the arrangement of micro and nanometric fibers constituting the bacterial cellulose membrane. The final product was kept at -70 °C for 24 h and lyophilized for further characterization.

Figure 2 shows the diagram of the methodology for obtaining nanocellulose by

R. leguminosarum from pineapple agroindustrial waste using the bacteriological method.

2.4. Decision Matrix for the Comparison of NC Production Methods

The comparison of NC production methods was conducted by considering engineering and production aspects, with the evaluation criteria systematically organized into a decision matrix [

32] (

Table 1). Each criterion was assigned an importance value based on results from laboratory experiments. This is detailed in

Table 1, where specific parameters for each criterion are listed. Importance levels range from 1 to 5, with 1 representing the lowest importance and 5 representing the highest. The importance value was multiplied by the corresponding criterion's weight, and the resulting products were summed to yield a total score, quantitatively indicating which method is more optimal. Finally, these numerical values were compared to determine the most optimal method for automation in a production line.

The importance levels assigned to each criterion in the decision matrix are based on their impact on the overall efficiency, sustainability, and safety of the NC production process. Each criterion has been evaluated according to key factors that influence production outcomes, and these have been quantified to reflect their relative significance. The selected importance levels are shown below:

Amount of Reagents Used: Lower amounts (x≤1g) are highly valued (level 5) for cost and sustainability, while higher amounts (15≤x) receive the lowest importance (level 1).

Production/Acquisition Time: Shorter times (~3 days) are most valued (level 5), with longer times (4 weeks) being least valued (level 1).

Amount of Product Obtained: Higher yields (5 g or more) are most important (level 5), while lower yields (5 mg) are least important (level 1).

Water Footprint: Minimal water usage (x≤3L) is highly desirable (level 5), with higher usage (15L or more) less desirable (level 1).

Purification Stages: For efficiency and cost, fewer stages (1) are preferred (level 5), while more stages (5) are less preferred (level 1).

Waste Management: Non-hazardous waste is optimal (level 5), while hazardous waste is least favorable (level 1).

Additionally, a set of quantitative indicators was collected throughout the experimental workflow to enable a direct comparison of the two nanocellulose production methods. These parameters included estimated process duration (days), number of purification steps, volume of water used, type and number of chemical reagents involved, and qualitative assessment of post-treatment requirements. Data were recorded during the preparation, execution, and cleanup stages of both chemical and bacteriological protocols, as described in

Section 2.2 and

Section 2.3. These values were compiled in a comparative table (

Table 3) to complement the decision matrix, allowing a more detailed operational and environmental metrics assessment.

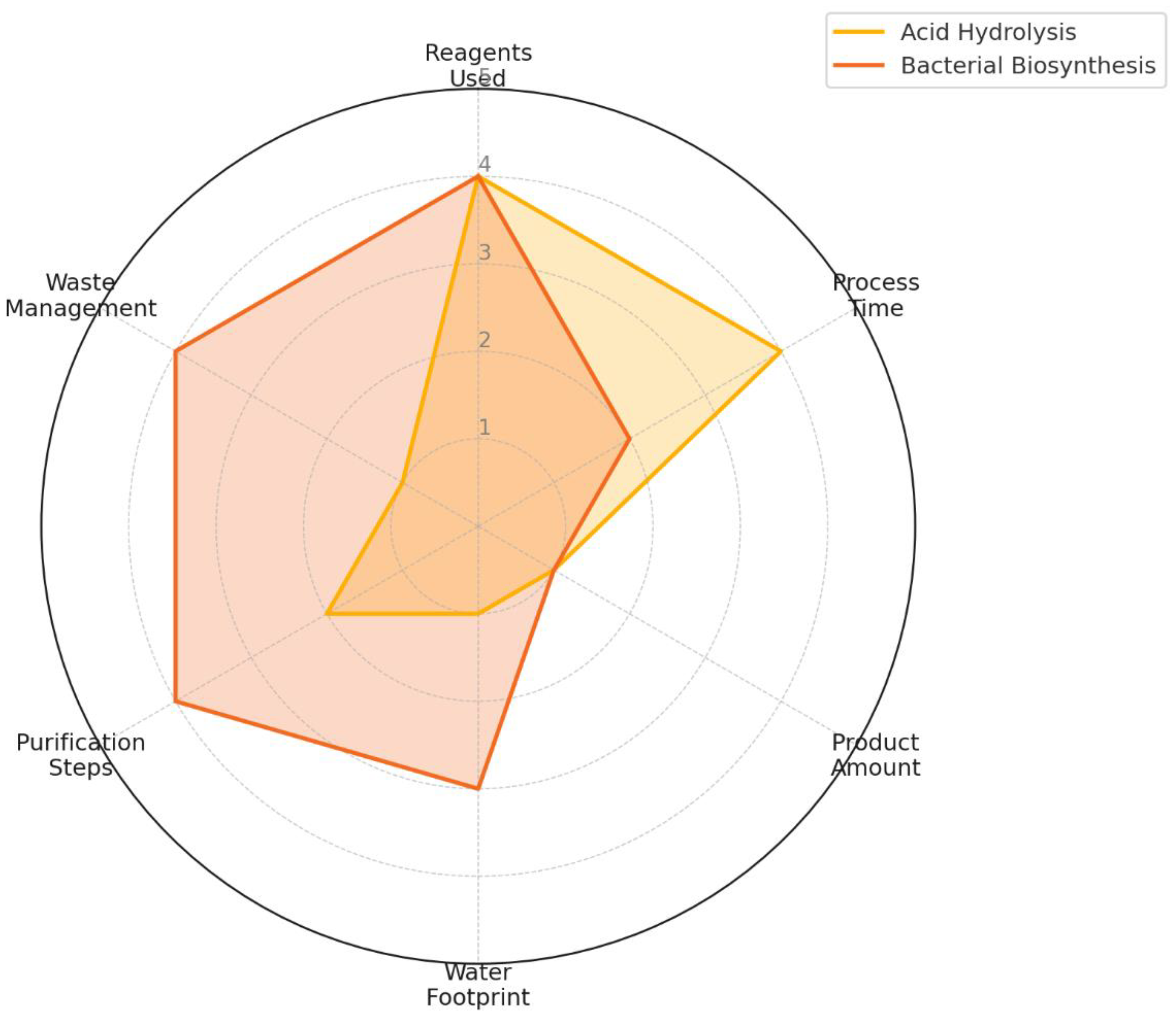

In addition to the numerical matrix, a radar chart was developed to visualize the comparative performance of each nanocellulose production method across six key criteria: reagent usage, process duration, product amount, water footprint, purification complexity, and waste management. Based on experimental data and process observations, each criterion was assigned a score from 1 (least favorable) to 5 (most favorable). The exact weighting and importance values were applied for a normalized visual comparison. These scores were plotted in a radar chart format using Python's Matplotlib library to create a radar chart, enabling a holistic and intuitive assessment of the strengths and weaknesses of each method.

2.5. Nanocellulose Characterization

2.5.1. Fourier Transform Infrared Spectroscopy

The FTIR spectrophotometer (Nicolet 6700, Thermo Scientific) analysis was performed to determine the main functional groups on the BNC and nanocellulose obtained by the chemical method. The measurements were done in a spectrum from 4000 cm-1 to 500 cm-1. The analysis was done in duplicate. The results were analyzed on the OMNIC 8.1 (OMNIC Series 8.1.10, Thermo Fisher Scientific) software.

2.5.2. Scanning Electron Microscopy

The BNC and nanocellulose obtained by the chemical method were analyzed using a scanning electron microscope (JSM-6390LV, Jeol, LANOTEC, San Jose, Costa Rica), with a voltage acceleration of 10 kV, secondary electrons (SEI), and a spot size of 40.

2.5.3. Atomic Force Microscopy

The BNC and nanocellulose obtained by the chemical method were visualized with an Asylum Research, MFP-3DTM AFM. A drop of the NC was deposited onto a mica substrate and was allowed to air dry for 24 h. Samples were analyzed using tapping mode AFM using a 10 mm silicon nitride probe. The height data was collected at a scanning frequency of 1 Hz. WsxM software (4.0 Develop 8.1, Nanotec Electronica, S.L., Spain) was used for the AFM analysis.

Key characterization data from FTIR, SEM, and AFM analyses were compiled into a comparative summary table to directly compare the structural and chemical properties of nanocellulose obtained via both production methods.

FTIR spectra were analyzed to identify functional groups and assess similarities in chemical bonding patterns across both samples. SEM was used to observe the morphology and fiber network structure at multiple magnifications, while AFM provided nanometric measurements of fiber height and surface features. These characterizations were performed independently for chemically extracted nanocellulose and bacterial nanocellulose obtained from Rhizobium leguminosarum biovar trifolii.

Data were recorded during each characterization technique and subsequently integrated into a single comparative matrix to highlight distinguishing features in molecular structure, fibrillar organization, and nanoscale dimensions.

2.5.4. Data analysis

The data were plotted on OriginPro, version 2019b, Northampton, MA, USA.

3. Results and Discussion

3.1. Structural and Physicochemical Characterization

3.1.1. Fourier Transform Infrared Spectroscopy

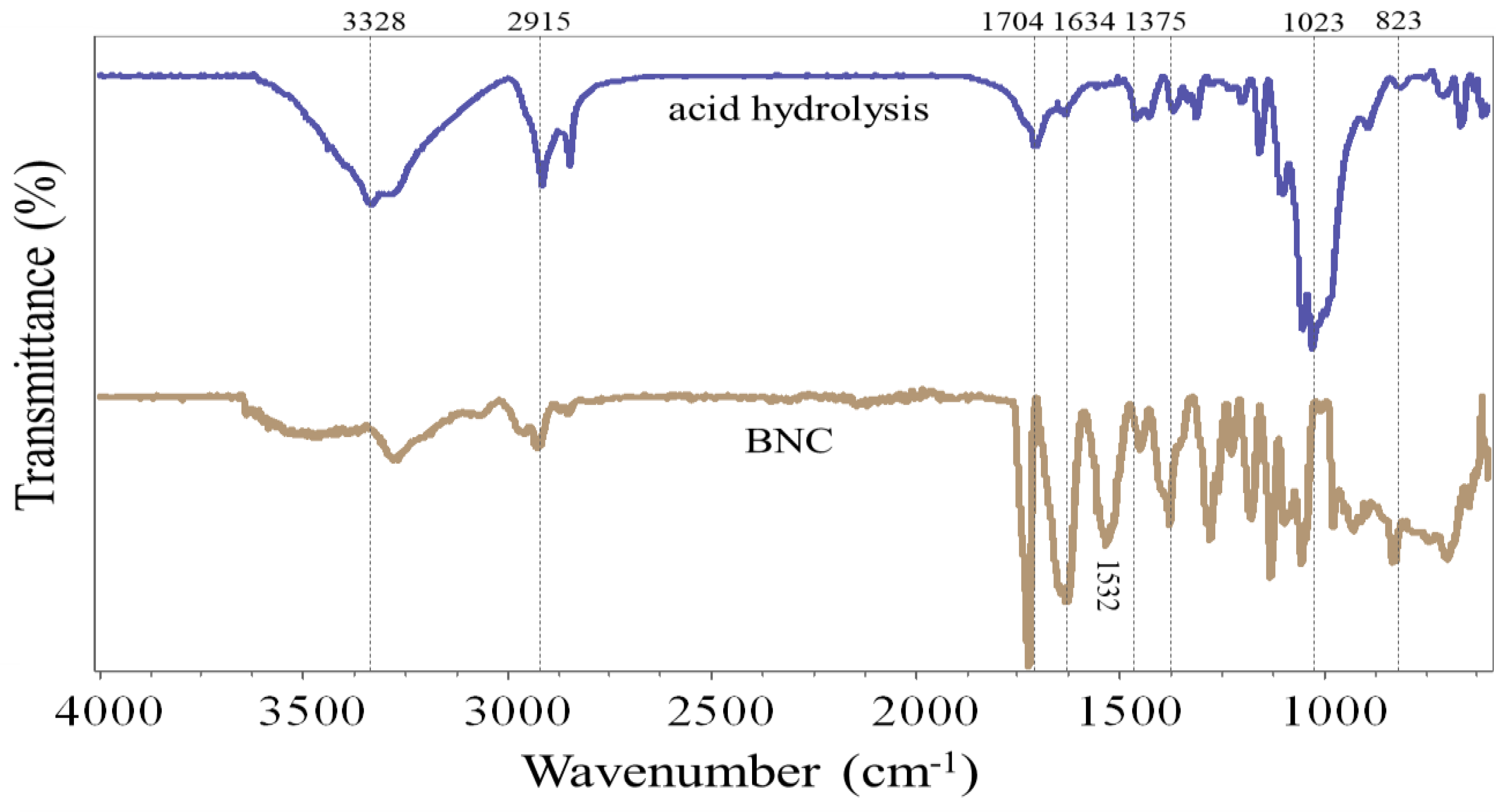

From the FTIR analysis, it was possible to determine the main functional groups in the NC freeze-dried samples obtained by acid hydrolysis and bacterial synthesis (

Figure 3).

The FTIR spectrum of the NC samples obtained by both methods shows a similar structural profile to that of the NC control. The band observed between 3000 cm

-1 and 3800 cm

-1 is characteristic of interactions generated by hydroxyl (OH) groups, which can be linked to water in the samples [

33,

34,

35]. The peak observed at 2900 cm

-1 is assigned to the elongation of C-H groups [

36,

37]. In addition, the peaks observed within the range of 1700 cm

-1 and 1633 cm

-1 are attributed to the vibration absorbed by the sugar bonds present in the cellulose [

34]. On the other hand, the peak shown around 1460 cm

-1 is linked to the C-H vibration in the carbon chains [

38,

39,

40]. The bands in the 1030 cm

-1 to 1050 cm

-1 range are due to the vibrational behavior of the C-O-C group, which can be related to cellulose chains [

35,

41]. Also, it should be noted that the peaks observed near 890 cm

-1 correspond to C-O-C stretching at β (1,4) glycosidic linkage [

19,

37,

42].

3.1.2. Scanning Electron Microscopy

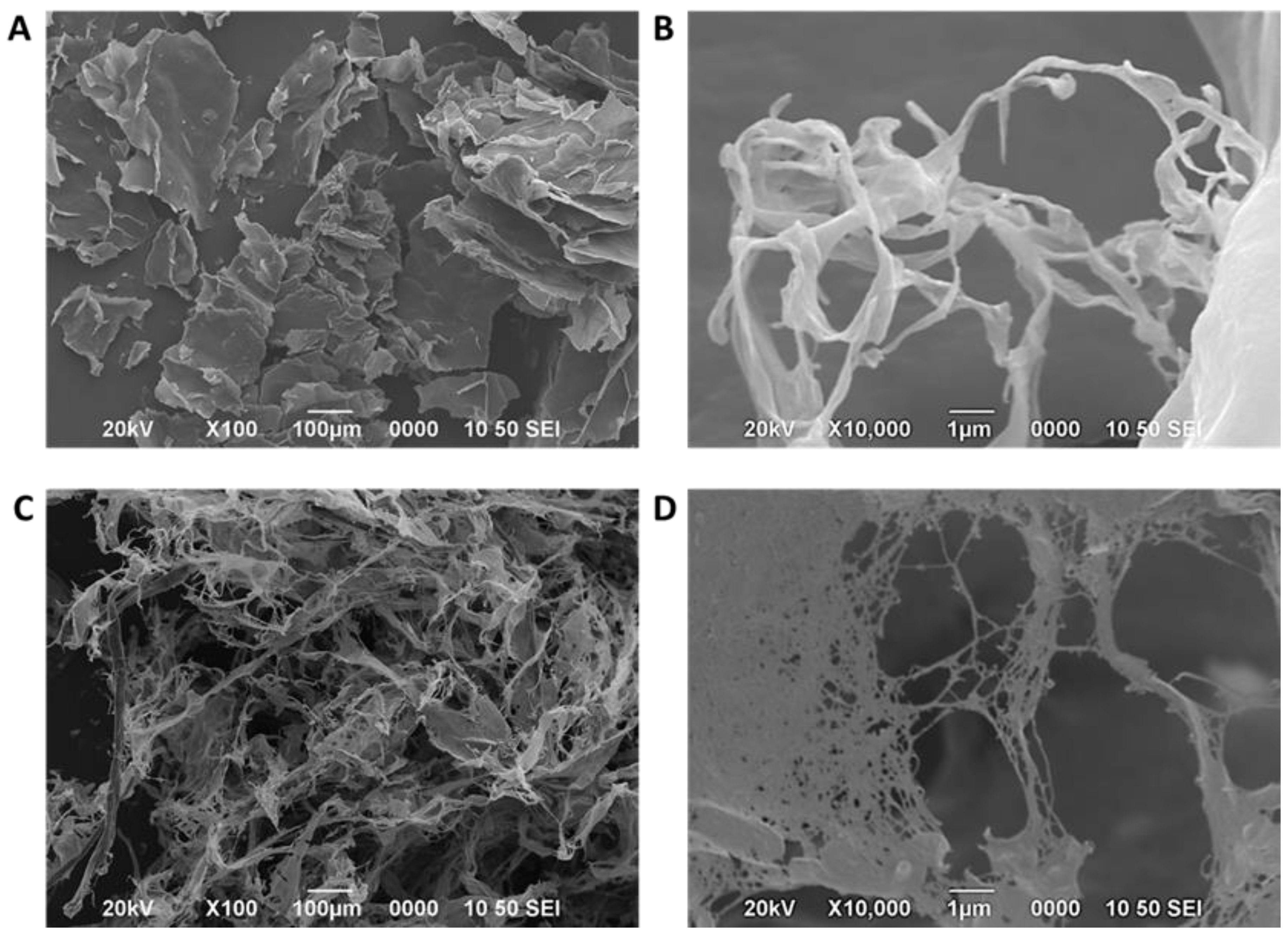

The surfaces of both NC were investigated by SEM (

Figure 4). Some studies have determined and compared the morphological characteristics of NC obtained by chemical methods and BNC using SEM [

43,

44].

Figure 4 shows the structure of NC obtained by the chemical method (

Figure 4A and

Figure 4B) and by R. leguminosarum (

Figure 4C and

Figure 4D).

The SEM images of NC obtained by acid hydrolysis revealed a lamellar structure (

Figure 4A) and a fibrous structure (

Figure 4 B). The photos also depicted a microscale arrangement of fibers within these lamellae, with a width on the nanometer scale. This structural organization indicates the effective breakdown of cellulose fibrils into smaller components under acidic conditions. This observation aligns with previous research that has documented a similar organization of cellulose fibrous or lamellar following acid treatment [

45,

46].

Otherwise,

Figure 4 (C and D) shows micrographs of the material produced by R. leguminosarum. In

Figure 4C, a pattern of a network of cellulose nanofibers is visible, with fibers determined to be less than 100 nm in length. Similarly, Khan et al. [

47], determined the morphology by SEM produced by K. xylinus IITRDKH20 and revealed a randomly arranged typical heterogeneous 3-D interconnected network of cellulose nanofibers in the range of 40-50 nm in width, while Sadalage and Pawar [

43], demonstrated the presence of NC with lengths in the range of 30-62.47 nm. It has been determined that the morphology of the BNC membranes changes depending on the composition of the culture medium [

48]. In addition, the fact that nanometric fibers are not uniformly present can be attributed to the exposure time to ultrasonic treatment, which is responsible for disaggregating the fibrillar arrangement [

45,

49].

According to these results, the NC obtained by both methods comprises micro- and nanofibers. Some differences between the two NC are observed regarding fiber size and morphology, with the NC obtained by the chemical method being more fibrous or lamellar. In contrast, the BNC obtained by the bacteriological method forms a nanocellulose network.

3.1.3. Atomic Force Microscopy

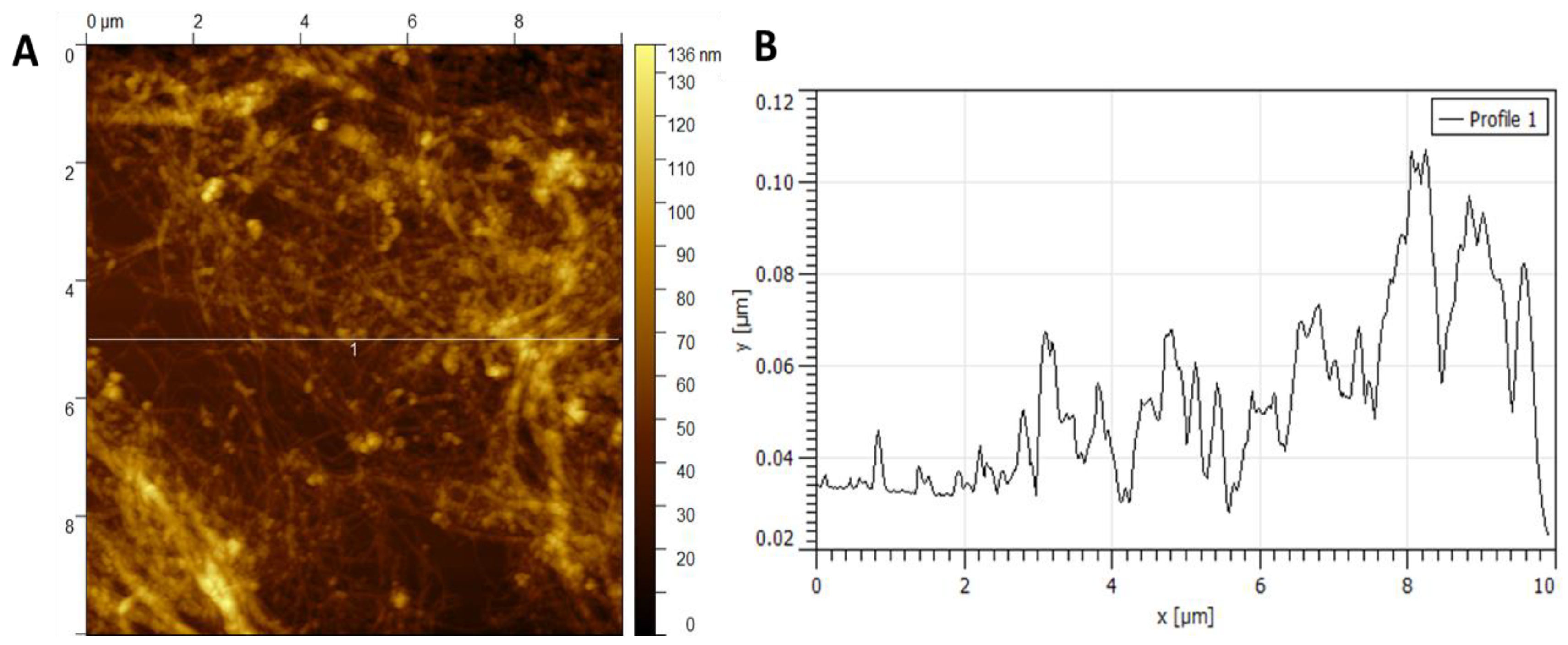

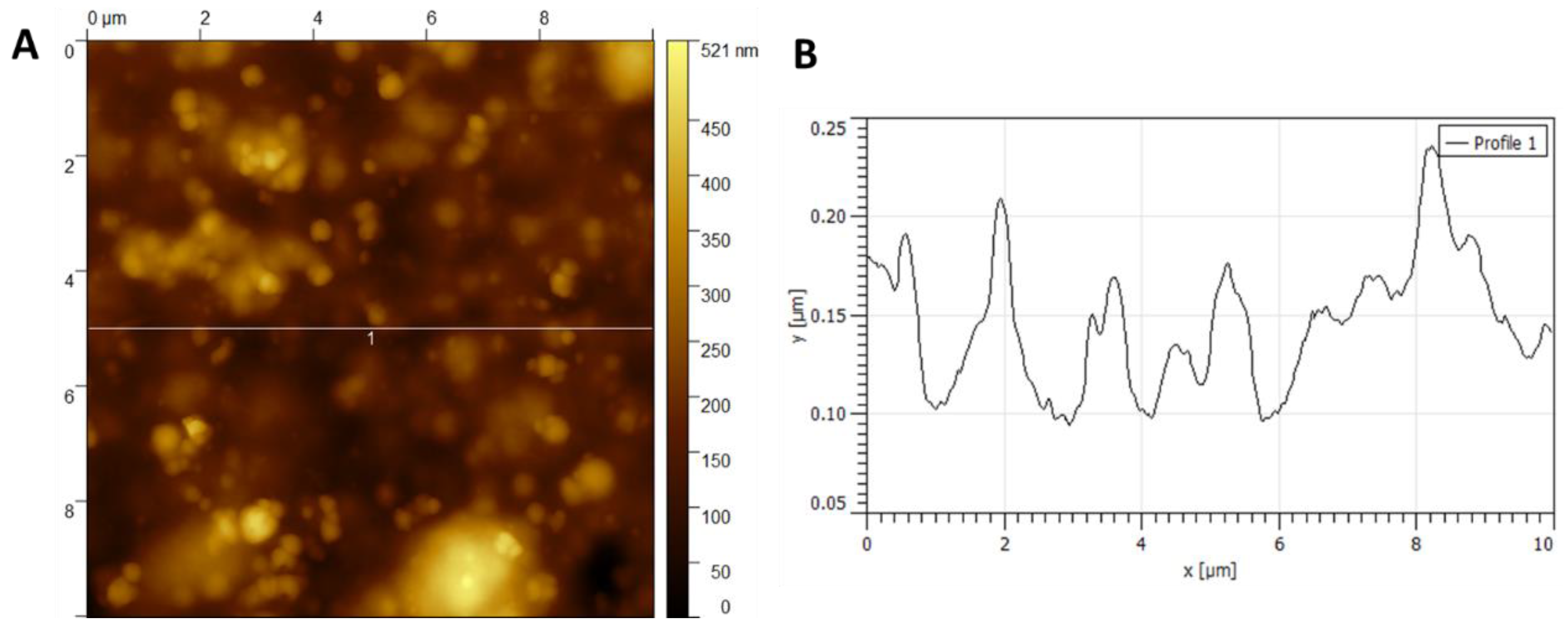

Figure 5 and

Figure 6 show the AFM images of NC obtained by chemical hydrolysis and R. leguminosarum, respectively.

Figure 5A shows dispersed fibers in the range of 20 and 60 nm. By averaging the region of peaks marked in

Figure 5A, an average height of approximately 11 ± 3 nm is obtained (

Figure 5B).

In

Figure 6A, a non-uniform morphology of the NC obtained by the chemical method can be observed. This result coincides with what is observed in

Figure 4, where a lamellar structure is determined.

Figure 6B refers to a cross-section of

Figure 6A. By averaging the region of peaks marked in

Figure 6B, an average height of approximately 70 ± 12 nm is obtained.

The height of nanocellulose fibers obtained by both methods was statistically analyzed using Student’s t-test (α = 0.05). The chemically derived NC exhibited an average height of 70 ± 12 nm, while the bacterial NC averaged 37 ± X (visual) nm. The difference in fiber height was statistically significant (p < 0.01), supporting the distinct structural differences observed in AFM images.

3.1.4. Comparative Summary of Physicochemical Properties

Table 2 presents a comparative summary to consolidate the structural and spectroscopic differences between the nanocellulose materials obtained by chemical hydrolysis and bacterial biosynthesis. This table integrates key findings from FTIR, SEM, and AFM analyses, offering a condensed but multidimensional view of the physicochemical properties of both materials.

In terms of chemical structure, both nanocellulose types share characteristic FTIR absorption bands associated with hydroxyl (OH), alkyl (C–H), ether (C–O–C), and β(1→4) glycosidic bonds. This confirms that the fundamental cellulose backbone is preserved in both cases, regardless of the production method. However, slight variations in band intensities and shifts—particularly in the 1030–1050 cm⁻¹ and 890 cm⁻¹ regions—may reflect differences in crystallinity and molecular arrangement, which were not quantified in this study but have been noted in prior work [

33,

34].

SEM observations further illustrate these differences. The chemically derived nanocellulose presents a lamellar-fibrous morphology with less uniformity and more apparent aggregation, whereas the bacterial nanocellulose exhibits a highly interconnected, three-dimensional nanofiber network. This network is more homogeneous and consistent with typical bacterial nanocellulose structures, as reported in other Rhizobium and Komagataeibacter strains [

47,

48].

These morphological traits are corroborated by AFM measurements, which revealed notable differences in fibril dimensions. Acid-hydrolyzed nanocellulose displayed thicker fibrils, averaging 70 ± 12 nm in height, while bacterial nanocellulose produced thinner, more dispersed fibrils with an average of ~37 nm. This reduction in fibril size may enhance the surface-to-volume ratio, an essential factor in applications requiring high surface reactivity, such as drug delivery, membrane systems, or nanocomposites.

Overall, the comparative summary in

Table 2 highlights the morphological and chemical distinctions between the two materials and supports the notion that bacterial biosynthesis yields a structurally refined product with potentially superior performance characteristics for advanced applications.

3.2. Visual Integration of Multicriteria Evaluation

Table 3 shows the value obtained for each criterion to compare the two processes for obtaining NC. Based on the results, it was determined that the chosen methodology is biological, with a value of 66 received by the chemical method. Nowadays, substituting chemical methods with biological methods in NC production has become increasingly common to provide more environmentally friendly procedures. In contrast to chemical processes that use toxic reagents and high energy consumption, biological methods offer a more sustainable alternative [

43].

Table 3.

Decision matrix with the values obtained for each criterion to compare the acid hydrolysis and bacterial biosynthesis methods.

Table 3.

Decision matrix with the values obtained for each criterion to compare the acid hydrolysis and bacterial biosynthesis methods.

| |

Method |

| Criteria |

Importance level |

Acid hydrolysis |

Total acid hydrolysis |

Bacterial biosynthesis |

Total bacterial biosynthesis |

| Amount of used reagents |

3 |

4 |

12 |

4 |

12 |

| Production/Acquisition time |

5 |

4 |

20 |

2 |

10 |

| Amount of product obtained |

4 |

1 |

4 |

1 |

4 |

| Water footprint |

4 |

1 |

4 |

3 |

12 |

| Purification |

4 |

2 |

8 |

4 |

16 |

| Waste management |

3 |

1 |

3 |

4 |

12 |

| Total |

|

51 |

66 |

3.2.1. Amount of Reagents Used

This evaluation criterion was determined based on the consumption of reagents during each process. According to the description of the chemical method, it uses a maximum of four reagents. In contrast, the bacteriological method involves using multiple reagents in the culture media for both the maintenance and inducer phases. These sum up to a total of six reagents in each phase. However, the quantity of reagents used for the bacteriological process is significantly lower in grams. A possible alternative to reduce the amount of reagents used and to reduce the production cost is to explore alternative culture media derived from residual biomass. In recent years, several studies have been conducted to produce BNC using various waste products, such as apple peels [

47], Cantaloupe juice, and Ulva lactuca [

35], reducing sugar from grass straw, grass husk, wheat husk, and corn cob [

43].

3.2.2. Production Time

Regarding the time required to obtain nanocellulose (NC), there is a notable difference between the chemical and bacteriological methods. For instance, the chemical process typically takes about one week, with 8-hour workdays [

19]. In contrast, the bacteriological process may extend to approximately two weeks, based on the microorganism's strain, culture media, and conditions, such as pH, temperature, agitation, and other factors. It should be noted that the chemical method requires constant monitoring throughout its execution, as each stage demands control of temperature, agitation, and washes [

13,

19].

On the other hand, the bacteriological method requires approximately 18 days to prepare culture media, inoculate, and ferment. However, cultures are left incubating during this period without all-day monitoring. Additionally, the extraction and purification of membranes and fibers produced during fermentation are completed in approximately 2.5 hours, resulting in a more efficient process, lower production costs, and shorter production times than the chemical methods [

50].

3.2.3. Water Footprint

The water impact of both methods was considered due to their significant water consumption. In the case of the chemical method, an estimated 14 liters of water are used for the neutralization stage of the NaOH. In contrast, the bacteriological process uses only 300 mL to remove the same reagent. Therefore, the amount of water consumed in the washing stages of the chemical method could allow for the setup of multiple fermentation cultures. For example, the 14 liters would equate to 28 cultures prepared with 500 mL each on a pilot scale.

Most chemical methods still need pre-treatment, acid hydrolysis, bleaching, and neutralization, which consume large quantities of water and toxic chemical reagents [

13,

51]. Due to this issue, many researchers have been investigating the use of microorganisms to produce BNC [

52,

53] as an alternative that may respond to the demand for this material and the sustainability of the process while maintaining the physicochemical characteristics of the NC. It has been reported that BNC production decreases water consumption [

24].

3.2.4. Purification Stages

There is a significant difference in purification stages between the methods. In chemical extraction, all remnants of reagents used on the raw material must be removed. An alkali treatment was applied to remove components such as lignin, hemicelluloses, pectins, waxes, and a bleaching process was used to remove lignin residues. In addition, the final product must undergo dialysis under constant stirring to eliminate sulfuric acid and soluble material such as salts and sugars until neutralization is achieved. Although it is still necessary to develop efficient pretreatments to remove impurities, contaminants, and non-cellulosic components on the raw materials without affecting cellulose or its purity, as cellulose is the primary material used for nanocellulose preparation [

8,

54].

In contrast, in bacteriological production, the purification stage is implicit in the process, as it involves removing bacterial cells to utilize the final product. Compared to the purification process from a chemical method with bacteriological production, for BNC, the purity is nearly 100%, generating a cost-effective procedure, despite the similar chemical composition with plant cellulose, BNC doesn’t have other components such as lignin, hemicelluloses, and pectin [

8,

55].

3.2.5. Waste Management

Reagents used in acid hydrolysis are considered corrosive and toxic, mainly when used in high concentrations, increasing their risk [

56]. In contrast, reagents used in bacterial biosynthesis pose lower risks due to significantly lower concentrations [

50]. Their disposal involves sterilization and disposal as regular waste or by effluent treatment plants. On the other hand, acid hydrolysis requires, in its different steps, the use of chemical reagents, such as NaOH, NaClO, HCl, and H

2SO

4 [

19]. This methodology requires neutralizing acidic and basic waste before disposal, which increases water and reagent consumption for neutralization. Therefore, the chemical method is challenged by toxic chemical utilization, energy, time consumption, and wastewater generation [

57]. In addition, this process also leads to equipment corrosion. It poses challenges in disposing of and recovering the large amounts of chemical waste generated [

43], in compliance with local, regional, national, or international regulations (C(2001)107/FINAL of the OECD). Therefore, developing green technologies for the production of NC is being prioritized.

3.2.6. Quantitative Process Comparison

To complement the scoring-based decision matrix in

Table 3,

Table 4 provides a direct, quantitative comparison of key process parameters associated with the two nanocellulose (NC) production methods: chemical hydrolysis and bacterial biosynthesis. This comparison highlights differences in operational complexity, environmental impact, and resource intensity, enriching the assessment with numerical and structural data.

Chemical hydrolysis, although relatively faster to execute (~7 days), involves multiple highly controlled steps, such as alkaline pretreatment, bleaching, acid hydrolysis, and neutralization. These steps require intensive manual oversight and consume large volumes of water—approximately 14 liters per batch—primarily for washing and pH adjustment. The method relies on several concentrated chemical reagents (e.g., NaOH, HCl, H₂SO₄), increasing handling risks and generating hazardous waste that must be neutralized and disposed of according to environmental regulations. Equipment corrosion and operational safety concerns are additional limitations of this approach.

In contrast, bacterial biosynthesis using Rhizobium leguminosarum biovar trifolii operates over a more extended period (~15–18 days), but it requires minimal intervention once cultures are inoculated. Water usage is significantly lower, with only ~300 mL needed per batch to rinse and purify the resulting bacterial nanocellulose membranes. The reagents are non-toxic and employed in low concentrations within culture media, reducing cost and environmental burden. Additionally, the purification process is more straightforward and inherently less hazardous, since bacterial NC is secreted extracellularly in high purity without requiring intensive chemical treatment.

Morphologically, the nanocellulose products also differ. Acid-hydrolyzed NC presents a more fragmented, lamellar structure with thicker fibrils (average height: 70 ± 12 nm), while bacterial NC displays a finer, interconnected nanofiber network with thinner fibrils (average height: ~37 nm), as observed in AFM and SEM analyses. These structural differences may influence surface area, mechanical behavior, and application potential in biomedical engineering or biocomposites.

To complement the numerical evaluation in

Table 3,

Figure 7 presents a radar chart that visually compares the weighted scores assigned to each decision criterion between the acid hydrolysis and bacterial biosynthesis methods for nanocellulose production.

The six criteria included are: (1) amount of reagents used, (2) production/acquisition time, (3) amount of product obtained, (4) water footprint, (5) purification steps, and (6) waste management. These scores were derived from experimental observations and normalized using a consistent scale from 1 (least favorable) to 5 (most favorable), based on environmental and operational performance.

The chart clearly illustrates the superior environmental and safety performance of the bacterial biosynthesis method, which scores higher in water footprint (score: 3 vs. 1), purification simplicity (4 vs. 2), and waste management (4 vs. 1). The two methods received equal scores (4) for reagent quantity, as the chemical method uses fewer types of reagents but in high concentrations, while the bacterial method uses more compounds but in smaller amounts.

In contrast, the acid hydrolysis method demonstrated better performance in production time (4 vs. 2), reflecting its faster process cycle, though it requires more monitoring and produces hazardous waste. Both methods scored equally low (1) in the "amount of product obtained" criterion, as neither process was optimized for yield during this study.

Figure 7 thus serves as a comprehensive visual synthesis of the comparative decision-making process, reinforcing the conclusion that bacterial biosynthesis, while slower, offers a more sustainable, safer, and potentially scalable pathway for nanocellulose production.

Overall, the data in

Table 4 reinforce the conclusion that bacterial biosynthesis offers a safer, more environmentally sustainable route for NC production. While not faster in real time, it demands fewer resources, generates cleaner outputs, and yields a structurally refined nanomaterial—all of which support its suitability for scalable, green manufacturing approaches.

4. Limitations and Future Work

While this study compares chemical and bacterial routes for nanocellulose extraction from pineapple waste, several limitations must be acknowledged. First, all experiments were conducted at laboratory scale, which may not fully reflect industrial-scale production's dynamics, challenges, or costs. Parameters such as energy consumption, bioreactor performance, and downstream logistics were not assessed but are critical for real-world deployment.

In addition, yield quantification—especially in terms of dry mass per liter or per gram of biomass—was not the central focus of this work. Although both routes produced sufficient material for characterization, future studies should include precise yield analysis under varying substrate concentrations, fermentation conditions, and scaling factors. The use of fed-batch or continuous culture systems may offer further improvements in productivity for the bacterial route.

Moreover, while the decision matrix integrated environmental and process-related criteria, no life cycle assessment (LCA) or techno-economic analysis (TEA) was conducted. These tools are necessary to validate each pathway's long-term sustainability and market feasibility. Incorporating full LCA/TEA in future work would enable policymakers and industry stakeholders to make informed decisions regarding green material integration.

Genetic engineering of R. leguminosarum and optimization of metabolic pathways may also unlock higher cellulose production rates, allowing this species to compete with conventional strains like Komagataeibacter xylinus. Similarly, exploring low-cost nutrient sources, such as sugar-rich agro-industrial effluents or enzymatically treated biomass, could further reduce the input cost and environmental burden.

Finally, a broader assessment that includes nanocellulose functionality—such as rheology, crystallinity, thermal stability, or surface charge—would complement this comparative framework, enabling application-driven selection of the most suitable production method.

Overall, future research should target the convergence of environmental impact, economic feasibility, and advanced material performance, facilitating the adoption of nanocellulose technologies in next-generation circular bioeconomies.

5. Conclusions

This comparative study demonstrates that nanocellulose can be efficiently produced from pineapple waste using acid hydrolysis and bacterial biosynthesis. While chemical hydrolysis offers shorter processing times, it requires high water consumption and generates hazardous waste. In contrast, bacterial synthesis using R. leguminosarum produces nanocellulose with comparable or superior structural properties, consumes significantly less water, and involves fewer purification steps. The resulting bacterial nanocellulose exhibits smaller average fiber sizes (37 nm), which may enhance its surface area and mechanical behavior.

Based on a decision matrix integrating environmental, technical, and resource-based factors, the bacterial approach emerged as more sustainable and scalable. This method aligns with circular economy principles and the global push toward green materials. Future studies should explore agro-waste-derived culture media, genetic optimization of bacterial strains, and pilot-scale production to assess industrial feasibility.

Author Contributions

Conceptualization, LCM, GMV, MCE, NL, and ML; methodology, LCM, JRVB, GMV, MCE, NL; software, JRVB, DBM; validation, GMV, MCE, JRVB, Y.Y., and DBM; formal analysis, LCM, GMV, MCE, DBM, NL; investigation, GMV, MCE, ML, NL; writing—original draft preparation, LCM, GMV, JRVB, MCE, ML; writing—review and editing, GMV, MCE; NL, JRVB; visualization, JRVB; supervision, GMV, MCE, JRVB, DBM, ML. All authors have read and agreed to the published version of the manuscript.

Funding

This research received no external funding.

Conflicts of Interest

The authors declare no conflicts of interest.

References

- [1] Amorim JDP, de Souza KC, Duarte CR et al (2020) Plant and bacterial nanocellulose: production, properties and applications in medicine, food, cosmetics, electronics and engineering. A review. Environ Chem Lett 18:851–869. [CrossRef]

- [2] Tarchoun AF, Trache D, Klapötke TM et al (2021) Synthesis and characterization of new insensitive and high-energy dense cellulosic biopolymers. Fuel 292:120347. [CrossRef]

- [3] Seddiqi H, Oliaei E, Honarkar H et al (2021) Cellulose and its derivatives: towards biomedical applications. Cellulose 28:1893–1931. [CrossRef]

- [4] Purushotham P, Ho R, Zimmer J (2020) Architecture of a catalytically active homotrimeric plant cellulose synthase complex. Science 369:1089–1094. [CrossRef]

- [5] Tu H, Zhu M, Duan B et al (2021) Recent progress in high-strength and robust regenerated cellulose materials. Adv Mater 33:2000682. [CrossRef]

- [6] Du H, Liu W, Zhang M et al (2019) Cellulose nanocrystals and cellulose nanofibrils based hydrogels for biomedical applications. Carbohydr Polym 209:130–144. [CrossRef]

- [7] Ribeiro RSA, Pohlmann BC, Calado V et al (2019) Production of nanocellulose by enzymatic hydrolysis: trends and challenges. Eng Life Sci 19:279–291. [CrossRef]

- [8] Sarangi PK, Srivastava RK, Sahoo UK et al (2024) Biotechnological innovations in nanocellulose production from waste biomass with a focus on pineapple waste. Chemosphere 349:140833. [CrossRef]

- [9] Das R, Lindstrom T, Sharma PR et al (2022) Nanocellulose for sustainable water purification. Chem Rev 122:8936–9031. [CrossRef]

- [10] Norizan MN, Shazleen SS, Alias AH et al (2022) Nanocellulose-based nanocomposites for sustainable applications: a review. Nanomaterials (Basel, Switzerland) 12:3483. [CrossRef]

- [11] Rashid AB, Hoque ME, Kabir N et al (2023) Synthesis, properties, applications, and future prospective of cellulose nanocrystals. Polymers 15(20):4070. [CrossRef]

- [12] Perumal AB, Nambiar RB, Moses JA et al (2022) Nanocellulose: Recent trends and applications in the food industry. Food Hydrocolloids 127:107484. [CrossRef]

- [13] Pradhan D, Jaiswal AK, Jaiswal S (2022) Emerging technologies for the production of nanocellulose from lignocellulosic biomass. Carbohydr Polym 285:119258. [CrossRef]

- [14] Wang J, Liu X, Jin T et al (2019) Preparation of nanocellulose and its potential in reinforced composites: A review. J Biomater Sci Polym Ed 30(11):919–946. [CrossRef]

- [15] Charpentier Alfaro C, Méndez Arias J (2021) Enzymatic conversion of treated oil palm empty fruit bunches fiber into fermentable sugars: Optimization of solid and protein loadings and surfactant effects. Biomass Conv Bioref 11(6):2359–2368. [CrossRef]

- [16] Nasir M, Hashim R, Sulaiman O et al (2017) Nanocellulose: Preparation methods and applications. In: Cellulose-Reinforced Nanofibre Composites. [CrossRef]

- [17] Macías-Almazán A, Lois-Correa JA, Domínguez-Crespo MA et al (2020) Influence of operating conditions on proton conductivity of nanocellulose films using two agroindustrial wastes: Sugarcane bagasse and pinewood sawdust. Carbohydr Polym 238:116171. [CrossRef]

- [18] Raza M, Abu-Jdaylin B, Bnat F et al (2022) Isolation and characterization of cellulose nanocrystals from date palm waste. ACS Omega 7(29):25366–25379. [CrossRef]

- [19] Camacho M, Ureña YRC, Lopretti M et al (2017) Synthesis and characterization of nanocrystalline cellulose derived from pineapple peel residues. J Renew Mater 5(3):271–279. [CrossRef]

- [20] Wang J, Tavakoli J, Tang Y (2019) Bacterial cellulose production, properties, and applications with different culture methods – A review. Carbohydr Polym 219:63–76. [CrossRef]

- [21] Lee AC, Salleh MM, Ibrahim MF et al (2022) Pineapple peel as alternative substrate for bacterial nanocellulose production. Biomass Conv Bioref 14(4):5541–5549. [CrossRef]

- [22] Chang SC, Kao MR, Saldivar RK et al (2023) The Gram-positive bacterium Romboutsia ilealis harbors a polysaccharide synthase that can produce (1,3;1,4)-β-D-glucans. Nat Commun 14(1):4526. [CrossRef]

- [23] Khan H, Saroha V, Raghuvanshi S et al (2021) Valorization of fruit processing waste to produce high value-added bacterial nanocellulose by a novel strain Komagataeibacter xylinus IITR DKH20. Carbohydr Polym 260:117807. [CrossRef]

- [24] Martínez E, Posada L, Botero JC et al (2023) Nata de fique: A cost-effective alternative for the large-scale production of bacterial nanocellulose. Ind Crops Prod 192:116015. [CrossRef]

- [25] Rahi P, Giram P, Chaudhari D et al (2020) Rhizobium indicum sp. nov., isolated from root nodules of pea (Pisum sativum) cultivated in the Indian trans-Himalayas. Syst Appl Microbiol 43(5):126127. [CrossRef]

- [26] Li X, Li Z (2023) What determines symbiotic nitrogen fixation efficiency in rhizobium: recent insights into Rhizobium leguminosarum. Arch Microbiol 205(9):300. [CrossRef]

- [27] Janczarek M, Kozieł M, Adamczyk P et al (2024) Symbiotic efficiency of Rhizobium leguminosarum sv. trifolii strains originating from the subpolar and temperate climate regions. Sci Rep 14:6264. [CrossRef]

- [28] Barja F (2021) Bacterial nanocellulose production and biomedical applications. J Biomed Res 35(4):310–317. [CrossRef]

- [29] Randhawa A, Dutta SD, Ganguly K et al (2022) A review of properties of nanocellulose, its synthesis, and potential in biomedical applications. Appl Sci 12:7090. [CrossRef]

- [30] Mbakop S, Nthunya LN, Onyango MS (2021) Recent advances in the synthesis of nanocellulose functionalized–hybrid membranes and application in water quality improvement. Processes 9:611. [CrossRef]

- [31] Almihyawi RAH, Musazade E, Alhussany N et al (2024) Production and characterization of bacterial cellulose by Rhizobium sp. isolated from bean root. Sci Rep 14:10848. [CrossRef]

- [32] Ahmed SA, Kazim AR, Hassan HM (2017) Increasing cellulose production from Rhizobium leguminosarum bv. viciae. J Al-Nahrain Univ-Sci 20(3):120–125. [CrossRef]

- [33] Ghafari R, Jonoobi M, Amirabad LM et al (2019) Fabrication and characterization of novel bilayer scaffold from nanocellulose-based aerogel for skin tissue engineering applications. Int J Biol Macromol 136:796–803. [CrossRef]

- [34] Liu C, Li B, Du H et al (2016) Properties of nanocellulose isolated from corncob residue using sulfuric acid, formic acid, oxidative, and mechanical methods. Carbohydr Polym 151:716–724. [CrossRef]

- [35] El-Naggar NEA, El-Malkey SE, Abu-Saied MA et al (2022) Exploration of a novel and efficient source for production of bacterial nanocellulose, bioprocess optimization, and characterization. Sci Rep 12:18533. [CrossRef]

- [36] Oliveira SA, da Silva BC, Riegel-Vidotti IC et al (2017) Production and characterization of bacterial cellulose membranes with hyaluronic acid from chicken comb. Int J Biol Macromol 97:642–653. [CrossRef]

- [37] Abol-Fotouh D, Hassan MA, Shokry H et al (2020) Bacterial nanocellulose from agro-industrial wastes: low-cost and enhanced production by Komagataeibacter saccharivorans MD1. Sci Rep 10:3491. [CrossRef]

- [38] Biswas A, Bayer IS, Biris AS et al (2012) Advances in top-down and bottom-up surface nanofabrication: Techniques, applications, and future prospects. Adv Colloid Interface Sci 170(1–2):2–27. [CrossRef]

- [39] Wang L, Shankar S, Rhim J (2017) Properties of alginate-based films reinforced with cellulose fibers and cellulose nanowhiskers isolated from mulberry pulp. Food Hydrocolloids 63:201–208. [CrossRef]

- [40] Wulandari WT, Rochliadi A, Arcana IM (2016) Nanocellulose prepared by acid hydrolysis of isolated cellulose from sugarcane bagasse. IOP Conf Ser Mater Sci Eng 107(1):012045. [CrossRef]

- [41] Kargarzadeh H, Ioelovich M, Ahmad I et al (2017) Methods for extraction of nanocellulose from various sources. In: Handbook of Nanocellulose and Cellulose Nanocomposites. John Wiley & Sons, Inc.; p. 1–49. [CrossRef]

- [42] Mugesh S, Kumar TP, Murugan M (2016) An unprecedented bacterial cellulosic material for defluoridation of water. RSC Adv 6(106):104839–104846. [CrossRef]

- [43] Sadalage PS, Pawar KD (2021) Production of microcrystalline cellulose and bacterial nanocellulose through biological valorization of lignocellulosic biomass wastes. J Clean Prod 327:129462. [CrossRef]

- [44] Singh SS, Salem DR, Sani RK et al (2021) Spectroscopy, microscopy, and other techniques for characterization of bacterial nanocellulose and comparison with plant-derived nanocellulose. In: Microbial and Natural Macromolecules. Academic Press; p. 419–454.

- [45] Onkarappa HS, Prakash GK, Pujar GH et al (2020) Facile synthesis and characterization of nanocellulose from Zea mays husk. Polym Compos. [CrossRef]

- [46] Velázquez ME, Ferreiro OB, Menezes DB et al (2022) Nanocellulose extracted from Paraguayan residual agro-industrial biomass: extraction process, physicochemical and morphological characterization. Sustainability 14(18):11386. [CrossRef]

- [47] Khan H, Saroha V, Raghuvanshi S et al (2021) Valorization of fruit processing waste to produce high value-added bacterial nanocellulose by a novel strain Komagataeibacter xylinus IITR DKH20. Carbohydr Polym 260:117807. [CrossRef]

- [48] Jacek P, Soares da Silva FAG, Dourado F et al (2021) Optimization and characterization of bacterial nanocellulose produced by Komagataeibacter rhaeticus K3. Carbohydr Polym Technol Appl 2:100022. [CrossRef]

- [49] Abral H, Lawrensius V, Handayani D et al (2018) Preparation of nano-sized particles from bacterial cellulose using ultrasonication and their characterization. Carbohydr Polym 191:161–167. [CrossRef]

- [50] Taokaew S (2024) Bacterial nanocellulose produced by cost-effective and sustainable methods and its applications: A review. Fermentation 10(6):316. [CrossRef]

- [51] Thakur VA, Guleria A, Kumar S et al (2021) Recent advances in nanocellulose processing, functionalization and applications: A review. Mater Adv 2:1872–1895. [CrossRef]

- [52] Al-Hagar OEA, Abol-Fotouh D (2022) A turning point in the bacterial nanocellulose production employing low doses of gamma radiation. Sci Rep 12:7012. [CrossRef]

- [53] Sharma C, Bhardwaj NK, Pathak P (2022) Rotary disc bioreactor-based approach for bacterial nanocellulose production using Gluconacetobacter xylinus NCIM 2526 strain. Cellulose 29:1. [CrossRef]

- [54] Faria L, Pacheco B, Oliveira G et al (2020) Production of cellulose nanocrystals from pineapple crown fibers through alkaline pretreatment and acid hydrolysis under different conditions. J Mater Res Technol 9(6):12346–12353. [CrossRef]

- [55] Zaini HM, Saallah S, Roslan J et al (2023) Banana biomass waste: A prospective nanocellulose source and its potential application in food industry - A review. Heliyon 9(8). [CrossRef]

- [56] Phanthong P, Reubroycharoen P, Hao X et al (2018) Nanocellulose: Extraction and application. Carbon Resour Convert 1(1):32–43. [CrossRef]

- [57] Li W, Shen Y, Liu H et al (2023) Bioconversion of lignocellulosic biomass into bacterial nanocellulose: challenges and perspectives. Green Chem Eng 4(2):160–172. [CrossRef]

|

Disclaimer/Publisher’s Note: The statements, opinions and data contained in all publications are solely those of the individual author(s) and contributor(s) and not of MDPI and/or the editor(s). MDPI and/or the editor(s) disclaim responsibility for any injury to people or property resulting from any ideas, methods, instructions or products referred to in the content. |

© 2025 by the authors. Licensee MDPI, Basel, Switzerland. This article is an open access article distributed under the terms and conditions of the Creative Commons Attribution (CC BY) license (http://creativecommons.org/licenses/by/4.0/).