Submitted:

24 May 2025

Posted:

26 May 2025

You are already at the latest version

Abstract

Keywords:

1. Introduction

2. Materials and Methods

2.1. Microorganisms

2.2. Wort Preparation

2.3. Fermentation

2.4. Analytical Procedures

2.4.1. Basic Wort and Beer Parameters

2.4.2. Secondary Metabolites Determination

2.5. Mathematical and Statistical Analysis

2.5.1. Fermentation Dynamic Calculations

2.5.2. Determination of Kinetic Parameters of the Fermentation Processes

- Specific Growth Rate (μ)

- Biomass Yield on Substrate (Yx/s)

- Product Yield on Substrate (Yp/s) and Biomass (Yp/x)

- Specific Substrate Consumption Rate (qs) and Specific Product Formation Rate (qp)

- Volumetric Productivity (Qp)

2.5.3. Principal Component Analysis (PCA)

2.5.4. Correlation Analysis

3. Results and Discussion

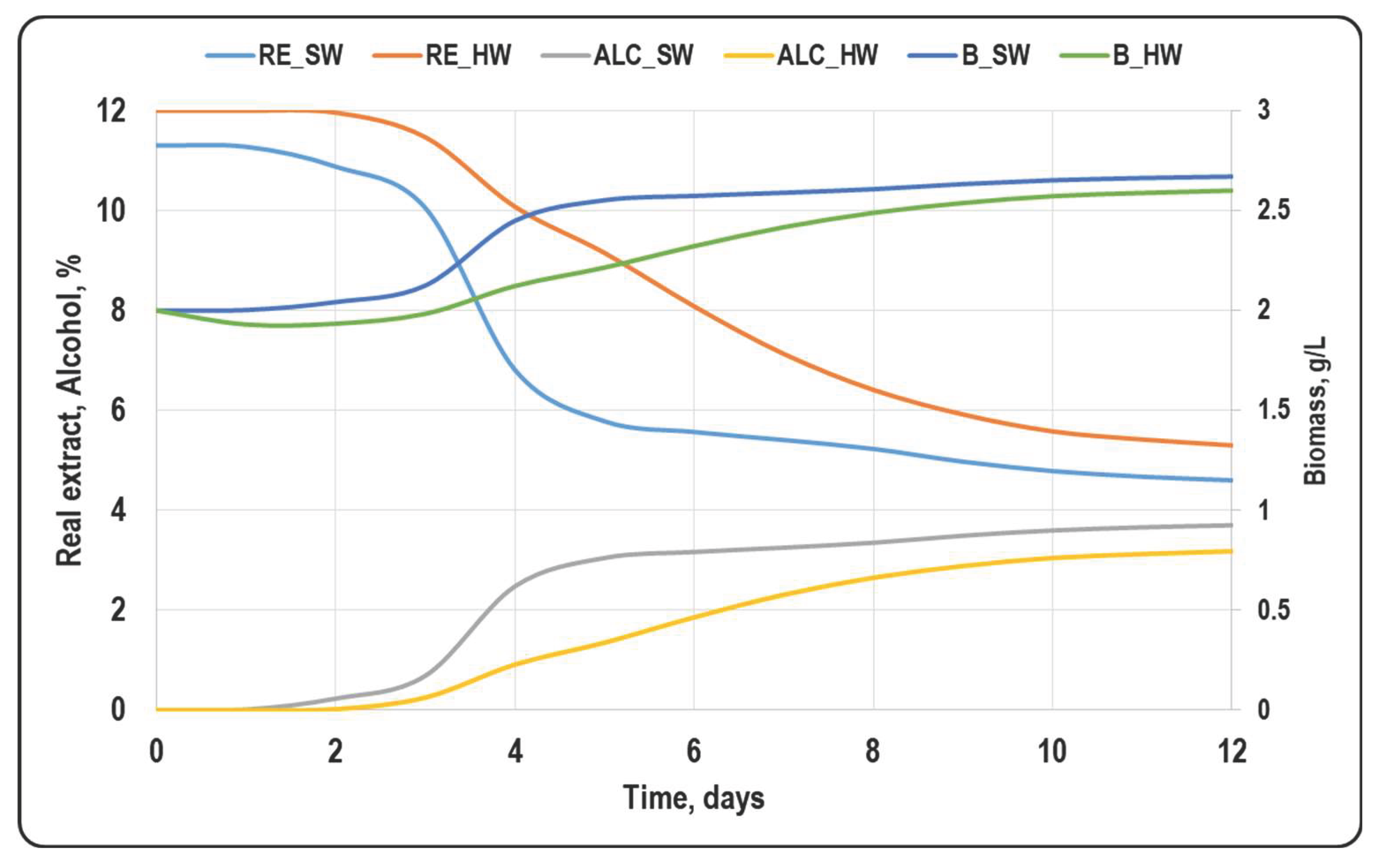

3.1. Basic Beer Parameters

3.2. Secondary Metabolites

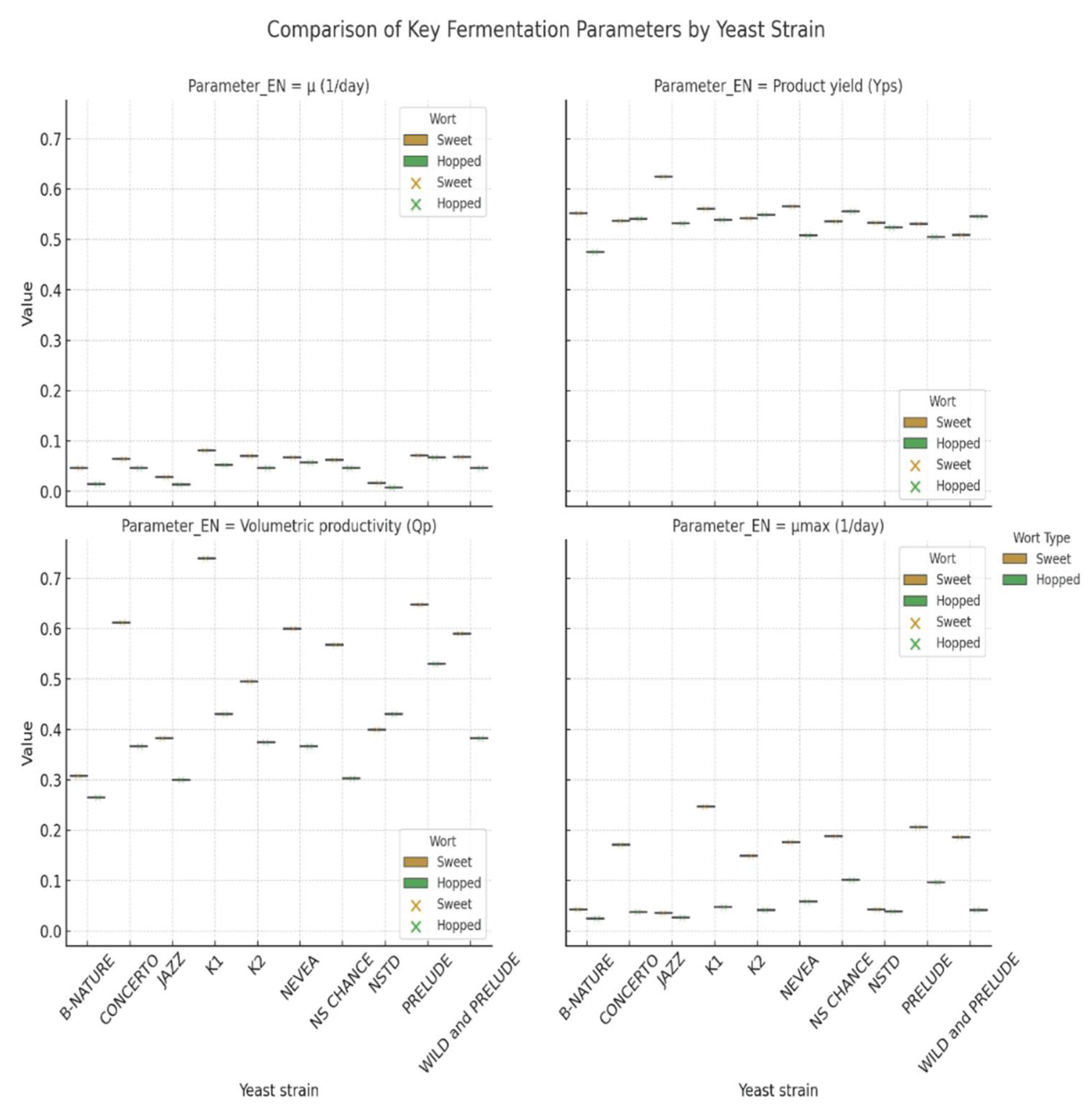

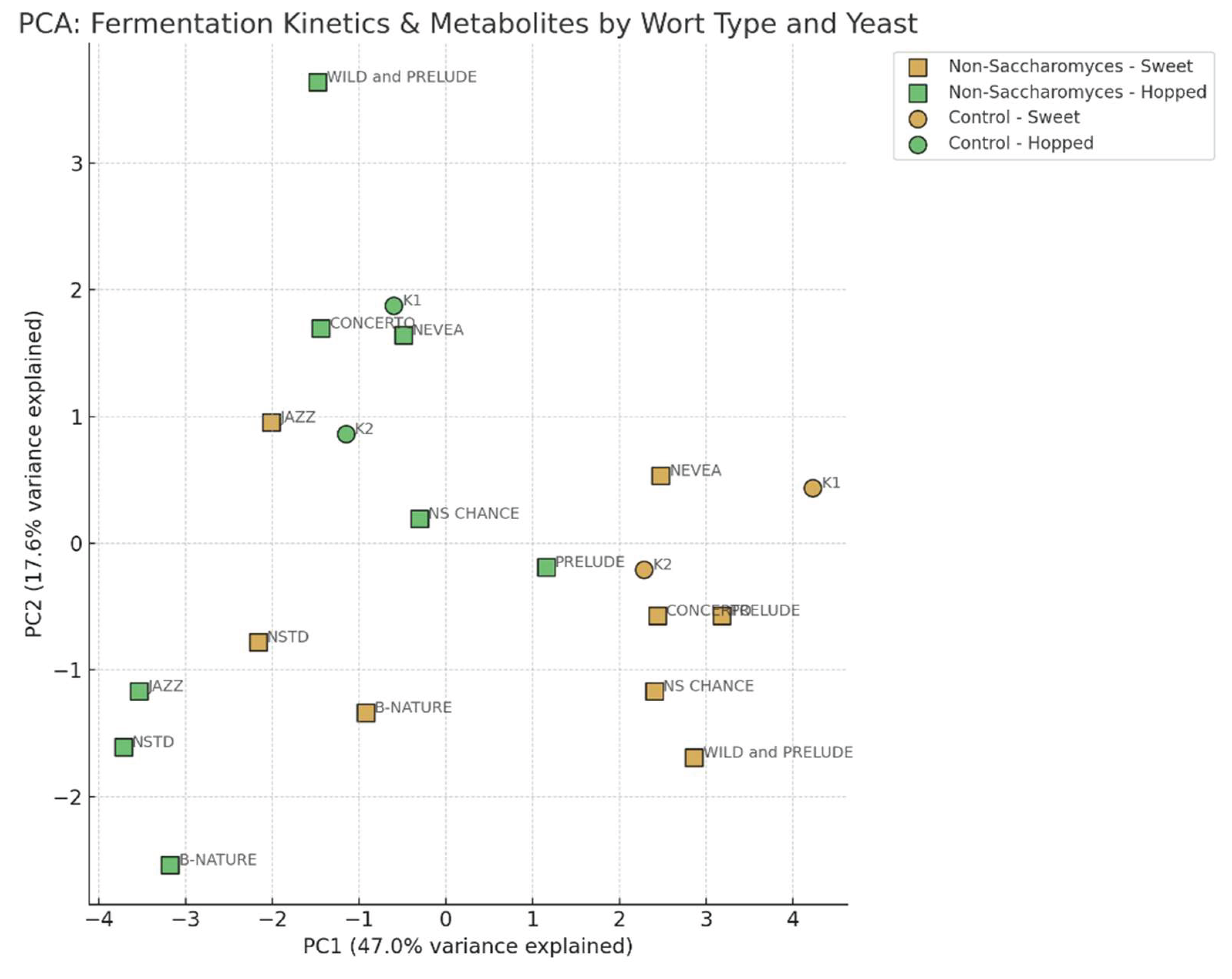

3.3. Comparative Assessment of the Fermentation Kinetics. Statistical Processing and PCA

- Some of the non-Sacharomyces yeasts have profiles similar to classic brewing strains.

- Others could be used as alternatives with distinctive aromatic capacity

- The type of wort (sweet or hopped) had a significant impact on the positioning in the component space, which should be taken into account in technological selection

5. Conclusions

Supplementary Materials

Author Contributions

Funding

Data Availability Statement

Acknowledgments

Conflicts of Interest

References

- Roselli, G.; Kerruish, D.; Crow, M.; Smart, K.; Powell, C. ; The two faces of microorganisms in traditional brewing and the implications for no-and low-alcohol beers. Front. Microbiol. 2024, 15, 1346724. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Lodolo, E. ; Kock, J,; Axcell, B,; Brooks M, The yeast Saccharomyces cerevisiae– the main character in beer brewing. FEMS Yeast Res. 2008, 8, 1018–1036. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Satora, P.; Pater, A. The Influence of Different Non-Conventional Yeasts on the Odour-Active Compounds of Produced Beers. Appl. Sci. 2023, 13, 2872. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Canonico, L,; Agarbati, A,; Comitini, F,; Ciani, M,; Unravelling the potential of non-conventional yeasts and recycled brewers spent grains (BSG) for non-alcoholic and low alcohol beer (NABLAB). Lwt. 2023, 190, 115528. [CrossRef]

- Gschaedler, A,; Contribution of non-conventional yeasts in alcoholic beverages. Current Opinion in Food Science. 2017, 13, 73–77. [CrossRef]

- Capece A, De Fusco D, Pietrafesa R, Siesto G, Romano P. Performance of Wild Non-Conventional Yeasts in Fermentation of Wort Based on Different Malt Extracts to Select Novel Starters for Low-Alcohol Beers. Applied Sciences. 2021; 11(2):801. [CrossRef]

- Capece, A,; Romaniello, R,; Siesto, G,; Romano, P,; Conventional and non-conventional yeasts in beer production. Ferment. 2018, 4(2), 38. [CrossRef]

- Budroni, M. ; Zara,; Ciani, M,; Comitini, F,; Saccharomyces and non-Saccharomyces starter yeasts. BREW Technology. 2017, 1, 81–100. [Google Scholar]

- Einfalt, D,; Barley-sorghum craft beer production with Saccharomyces cerevisiae, Torulaspora delbrueckii and Metschnikowia pulcherrima yeast strains. EurFood Res Technol. 2021, 247(2), 385–393. [CrossRef]

- Toh, D,; Chua, J,; Lu, Y,; Liu, S.; Evaluation of the potential of commercial non-Saccharomyces yeast strains of Torulaspora delbrueckii and Lachancea thermotolerans in beer fermentation. IJFST. 2020, 55(5), 2049-2059.

- Karaulli, J.; Xhaferaj, N,; Testa, B,; Letizia, F,; Kycyk, O,; Ruci, M,; Kongoli, R,; Lamce, F,; Lioha, I,; Sulaj, K,; Iorizzo, M,; Application of Saccharomyces cerevisiae 31 and Metschnikowia pulcherrima 62, isolated from Albanian vineyards, as new starters in the production of ale style beers. II-International Biological and Life Sciences Congress Biolic. Antalya, Turkey, on 30 October – 1 November, 2024, 410.

- Ellis, D,; Kerr, E,; Schenk, G,; Schulz, B,; Metabolomics of Non-Saccharomyces Yeasts in Fermented Beverages. Bev. 2022, 8(3), 41.

- Postigo, V,; Esteban, S,; Arroyo, T,; Lachancea thermotolerans, an innovative alternative for sour beer production. Bev. 2023, 9(1), 20.

- Fu, X,; Guo, L,; Li, Y,; Chen, X,; Song, Y,; Li, S,; Transcriptional Analysis of Mixed-Culture Fermentation of Lachancea Thermotolerans and Saccharomyces Cerevisiae for Natural Fruity Sour Beer. Ferment. 2024, 10(4), 180. [CrossRef]

- Karaulli, J,; Xhaferaj, N,; Coppola, F,; Testa, B,; Letizia, F,; Kyçyk, O.; Kongoli, R,; Ruci, M,; Lamce, F,; Sulaj, K,; Iorizzo, M,; Bioprospecting of Metschnikowia pulcherrima Strains, Isolated from a Vineyard Ecosystem, as Novel Starter Cultures for Craft Beer Production. Ferment. 2024, 10(10), 513.

- Canonico, L,; Agarbati, A,; Comitini, F,; Ciani, M,; Torulaspora delbrueckii in the brewing process: A new approach to enhance bioflavour and to reduce ethanol content. Food Microbiol. 2016, 56, 45–51. [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- EBC Analytica. Available online: https://brewup.eu/ebc-analytica/beer (accessed on 21 April 2025).

- Official Methods of Analysis of AOAC International (18 ed. AOAC International, 2007).

- Marinov, M. Practice for analysis and control of alcohol beverages and ethanol, Academic Publisher of UFT:Plovdiv, Bulgaria, 2010; pp 72-79.

- Parcunev, I.; Naydenova, V.; Kostov, G.; Yanakiev, Y.; Popova, Z.; Kaneva, M.; Ignatov, I. Modeling Of Alcohol Fermentation In Brewing—Some Practical Approaches. In Proceedings of the 26th European Conference on Modelling and Simulation, Shaping Reality through Simulation, Koblenz, Germany, 29 May–1 June 2012; Troitzsch, K.G., Moehring, M., Lotzmann, U., Eds.; European Council for Modeling and Simulation: Koblenz, Germany, 2012; pp. 434–440. [Google Scholar]

- Pyrovolou, K.; Tataridis, P.; Revelou, P.-K.; Strati, I.F.; Konteles, S.J.; Tarantilis, P.A.; Houhoula, D.; Batrinou, A. Fermentation of a Strong Dark Ale Hybrid Beer Enriched with Carob (Ceratonia siliqua L.) Syrup with Enhanced Polyphenol Profile. Appl. Sci. 2024, 14, 1199. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Shopska, V.; Dzhivoderova-Zarcheva, M.; Kostov, G. Continuous Primary Beer Fermentation with Yeast Immobilized in Alginate–Chitosan Microcapsules with a Liquid Core. Bev. 2024, 10, 87. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Nasuti, C.; Solieri, L. Yeast Bioflavoring in Beer: Complexity Decoded and Built up Again. Ferment. 2024, 10, 183. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Gasiński, A.; Kawa-Rygielska, J.; Mikulski, D.; Kłosowski, G.; Głowacki, A. Application of white grape pomace in the brewing technology and its impact on the concentration of esters and alcohols, physicochemical parameteres and antioxidative properties of the beer. Food Chem. 2022, 367, 130646. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Ferreira, I.M.; Guido, L.F. Impact of Wort Amino Acids on Beer Flavour: A Review. Ferment. 2018, 4, 23. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

| Yeast strains | Manufacturer |

|---|---|

| Saccharomyces pastorianus Saflager W34/70 | Fermentis by Lesaffre, Lambersart, France |

| Saccharomyces cerevisiae Safale US-05 | Fermentis by Lesaffre, Lambersart, France |

| Torulaspora delbrueckii Viniferm NS-TD | Agrovin, Alcázar de San Juan, Spain |

| Torulaspora delbrueckii Viniflora PRELUDE | Novonesis, Bagsværd, Denmark |

| Metschnikowia pulcherrima EXELLENCE B-Nature BIOPROTECTION | Lamothe-Abiet, Bordeaux, France |

| Lachancea thermotolerans Viniferm Ns-CHANCE | Agrovin, Alcázar de San Juan, Spain |

| Lachancea thermotolerans JAZZ | Lamothe-Abiet, Bordeaux, France |

| Lachancea thermotolerans NEVEA | SAS Sofralab, Magenta, France |

|

Lachancea thermotolerans / formerly Klyuveromyces thermotolerans/ Viniflora CONCERTO |

Novonesis, Bagsværd, Denmark |

| Saccharomyces cerevisiae/Torulaspora delbrueckii Oenoferm Wild and Pure | ERBSLÖH Gaisenheim GmbH, Gaisenheim, Germany |

| Wort type | Initial extract, °P | pH |

|---|---|---|

| Sweet wort | 11.3±0.1 | 6.22±0.02 |

| Hopped wort | 12.0±0.1 | 6.06±0.01 |

| Yeast strain | Wort type | Fermentation time, days |

Real extract, °P |

Alcohol, % w/w |

RDF, % |

pH |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| S. pastorianus Saflager W34/70 | Sweet wort | 5 | 4.7 | 3.70 | 59.80 | 4.75 |

| Hopped wort | 9 | 4.8 | 3.88 | 61.72 | 4.93 | |

| S. cerevisiae Safale US-05 | Sweet wort | 7 | 4.9 | 3.47 | 57.37 | 3.34 |

| Hopped wort | 12 | 3.8 | 4.42 | 68.83 | 4.46 | |

| T. delbrueckii NS-TD | Sweet wort | 8 | 5.3 | 3.12 | 54.06 | 3.50 |

| Hopped wort | 9 | 4.6 | 3.88 | 63.18 | 4.61 | |

| T. delbrueckii PRELUDE | Sweet wort | 5 | 5.2 | 3.06 | 54.93 | 4.70 |

| Hopped wort | 6 | 5.7 | 3.18 | 53.21 | 4.86 | |

| M. pulcherrima B-NATURE | Sweet wort | 12 | 4.6 | 3.70 | 60.69 | 3.70 |

| Hopped wort | 12 | 5.3 | 3.18 | 56.73 | 4.50 | |

|

L. thermotolerans Ns-CHANCE |

Sweet wort | 5 | 6.0 | 2.84 | 48.12 | 3.53 |

| Hopped wort | 16 | 3.3 | 3.30 | 73.45 | 3.63 | |

| L. thermotolerans JAZZ | Sweet wort | 8 | 6.4 | 3.06 | 43.95 | 4.04 |

| Hopped wort | 11 | 5.8 | 3.30 | 51.77 | 4.25 | |

| L. thermotolerans NEVEA | Sweet wort | 5 | 6.0 | 3.00 | 48.12 | 3.64 |

| Hopped wort | 9 | 5.5 | 3.30 | 47.02 | 3.93 | |

|

L. thermotolerans CONCERTO |

Sweet wort | 5 | 5.6 | 3.06 | 51.41 | 4.02 |

| Hopped wort | 9 | 5.9 | 3.30 | 52.59 | 4.50 | |

|

S. cerevisiae/T. delbrueckii WILD and PRELUDE |

Sweet wort | 5 | 5.5 | 2.95 | 53.17 | 3.88 |

| Hopped wort | 8 | 6.4 | 3.06 | 47.84 | 4.67 |

| Esters | Aldehydes | Higher alcohols | |||||

| SW | HW | SW | HW | SW | HW | ||

| S.pastorianus | Saflager W34/70 | 88.15 | 136.5 | 8.07 | 6.05 | 10.26 | 14.62 |

| S.cerevisiae | Safale US-05 | 88.15 | 72.03 | 12.11 | 8.07 | 9.7 | 9.95 |

| M.pulcherrima | B-NATURE | 72.03 | 72.03 | 32.29 | 8.07 | 3.53 | 2.39 |

| T.delbrueckii | NSTD | 184.85 | 168.73 | 10.09 | 76.69 | 11.09 | 8.19 |

| T.delbrueckii | PRELUDE | 168.73 | 72.03 | 10.09 | 10.09 | 4.91 | 4.03 |

| L. thermotolerans | CONCERTO | 104.27 | 120.38 | 26.24 | 12.11 | 11.59 | 12.98 |

| L.thermotolerans | NEVEA | 152.61 | 200.96 | 26.24 | 12.11 | 11.34 | 14.49 |

| L.thermotolerans | JAZZ | 152.62 | 72.03 | 10.09 | 16.15 | 4.92 | 1.76 |

| L.thermotolerans | NS CHANCE | 120.38 | 72.03 | 10.09 | 22.2 | 3.28 | 8.06 |

| S. cerevisiae/T. delbrueckii | WILD and PRELUDE | 72.03 | 184.84 | 26.23 | 8.07 | 8.82 | 24.32 |

| μmax (day⁻¹) | Yx/s | Yp/s | Yp/x | qs | qp | Qp | |||||||||

| SW | HW | SW | HW | SW | HW | SW | HW | SW | HW | SW | HW | SW | HW | ||

| S.pastorianus | Saflager W34/70 | 0.081 | 0.053 | 0.100 | 0.090 | 0.561 | 0.539 | 5.606 | 5.969 | 0.809 | 0.583 | 0.453 | 0.314 | 0.740 | 0.431 |

| S.cerevisiae | Safale US-05 | 0.070 | 0.047 | 0.100 | 0.092 | 0.542 | 0.549 | 5.420 | 6.000 | 0.702 | 0.508 | 0.381 | 0.279 | 0.496 | 0.375 |

| M.pulcherrima | B-NATURE | 0.046 | 0.014 | 0.100 | 0.090 | 0.552 | 0.475 | 5.520 | 5.300 | 0.464 | 0.159 | 0.256 | 0.075 | 0.308 | 0.265 |

| T.delbrueckii | NSTD | 0.017 | 0.007 | 0.100 | 0.091 | 0.533 | 0.524 | 5.330 | 5.791 | 0.168 | 0.082 | 0.090 | 0.043 | 0.400 | 0.431 |

| T.delbrueckii | PRELUDE | 0.071 | 0.067 | 0.100 | 0.089 | 0.531 | 0.505 | 5.310 | 5.680 | 0.713 | 0.755 | 0.379 | 0.381 | 0.648 | 0.530 |

| L.thermotolerans | CONCERTO | 0.064 | 0.047 | 0.100 | 0.089 | 0.537 | 0.541 | 5.370 | 6.110 | 0.639 | 0.528 | 0.343 | 0.285 | 0.612 | 0.367 |

| L.thermotolerans | NEVEA | 0.067 | 0.057 | 0.100 | 0.089 | 0.566 | 0.508 | 5.660 | 5.690 | 0.668 | 0.641 | 0.378 | 0.325 | 0.600 | 0.367 |

| L.thermotolerans | JAZZ | 0.028 | 0.014 | 0.100 | 0.089 | 0.625 | 0.532 | 6.245 | 6.000 | 0.281 | 0.153 | 0.175 | 0.082 | 0.383 | 0.300 |

| L.thermotolerans | NS- CHANCE | 0.062 | 0.046 | 0.100 | 0.092 | 0.536 | 0.556 | 5.359 | 6.050 | 0.620 | 0.500 | 0.332 | 0.278 | 0.568 | 0.303 |

| S. cerevisiae/T. delbrueckii | WILD and PRELUDE | 0.069 | 0.046 | 0.100 | 0.088 | 0.509 | 0.546 | 5.086 | 6.245 | 0.685 | 0.526 | 0.349 | 0.287 | 0.590 | 0.383 |

| μmax (day⁻¹) | Yp/s | qp | Qp | ||||||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| SW | HW | SW | HW | SW | HW | SW | HW | ||

| M. pulcherrima | B-NATURE | 0.574 | 0.271 | 0.985 | 0.881 | 0.565 | 0.240 | 0.416 | 0.615 |

| T. delbrueckii | NSTD | 0.208 | 0.141 | 0.950 | 0.973 | 0.198 | 0.137 | 0.541 | 1.000 |

| T. delbrueckii | PRELUDE | 0.882 | 1.274 | 0.947 | 0.937 | 0.836 | 1.212 | 0.876 | 1.229 |

| L. thermotolerans | CONCERTO | 0.790 | 0.887 | 0.958 | 1.004 | 0.757 | 0.907 | 0.827 | 0.851 |

| L.thermotolerans | NEVEA | 0.826 | 1.086 | 1.010 | 0.942 | 0.834 | 1.035 | 0.811 | 0.851 |

| L.thermotolerans | JAZZ | 0.347 | 0.258 | 1.114 | 0.988 | 0.387 | 0.259 | 0.517 | 0.696 |

| L. thermotolerans | NS CHANCE | 0.767 | 0.873 | 0.956 | 1.032 | 0.733 | 0.885 | 0.768 | 0.702 |

| S. cerevisiae/T. delbrueckii | WILD and PRELUDE | 0.848 | 0.873 | 0.907 | 1.014 | 0.769 | 0.914 | 0.797 | 0.887 |

| μmax (day⁻¹) | Yp/s | qp | Qp | ||||||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| SW | HW | SW | HW | SW | HW | SW | HW | ||

| M. pulcherrima | B-NATURE | 0.661 | 0.306 | 1.018 | 0.866 | 0.672 | 0.270 | 0.621 | 0.707 |

| T. delbrueckii | NSTD | 0.239 | 0.160 | 0.983 | 0.955 | 0.235 | 0.154 | 0.806 | 1.150 |

| T. delbrueckii | PRELUDE | 1.016 | 1.444 | 0.980 | 0.920 | 0.995 | 1.367 | 1.306 | 1.413 |

| L. thermotolerans | CONCERTO | 0.910 | 1.005 | 0.991 | 0.986 | 0.900 | 1.022 | 1.234 | 0.979 |

| L.thermotolerans | NEVEA | 0.951 | 1.231 | 1.044 | 0.925 | 0.992 | 1.167 | 1.210 | 0.978 |

| L.thermotolerans | JAZZ | 0.400 | 0.292 | 1.152 | 0.970 | 0.460 | 0.292 | 0.771 | 0.800 |

| L. thermotolerans | NS CHANCE | 0.884 | 0.989 | 0.989 | 1.014 | 0.872 | 0.997 | 1.145 | 0.807 |

| S. cerevisiae/T. delbrueckii | WILD and PRELUDE | 0.976 | 0.990 | 0.938 | 0.996 | 0.915 | 1.030 | 1.190 | 1.020 |

| Metabolites | μ | Qp | Yps |

| Esters | 0.55 | 0.62 | 0.48 |

| Aldehydes | -0.15 | -0.33 | -0.21 |

| Higher Alcohols | 0.44 | 0.38 | 0.35 |

Disclaimer/Publisher’s Note: The statements, opinions and data contained in all publications are solely those of the individual author(s) and contributor(s) and not of MDPI and/or the editor(s). MDPI and/or the editor(s) disclaim responsibility for any injury to people or property resulting from any ideas, methods, instructions or products referred to in the content. |

© 2025 by the authors. Licensee MDPI, Basel, Switzerland. This article is an open access article distributed under the terms and conditions of the Creative Commons Attribution (CC BY) license (http://creativecommons.org/licenses/by/4.0/).