Submitted:

18 September 2024

Posted:

18 September 2024

You are already at the latest version

Abstract

Keywords:

1. Introduction

2. Materials and Methods

2.1. Yeast Strains and Growth Condition

2.2. Pre selection Trials

2.2.1. Carbon Assimilation Profiles

2.2.2. Cryotolerance

2.2.3. Biogenic Amines Production

2.2.4. Hydrogen Sulphide Production

2.2.5. Pulcherrimin Production

2.3. Enzymatic Activities

2.3.1. API zym Assay

2.3.2. Proteolytic Activity

2.4. Craft Beer Brewing Process

2.5. Fermentation Kinetics

2.6. Main Chemical Parameters of Beers

2.7. Analysis of Volatile Compounds by GC-FID

2.8. Statistical Analysis

3. Results and Discussion

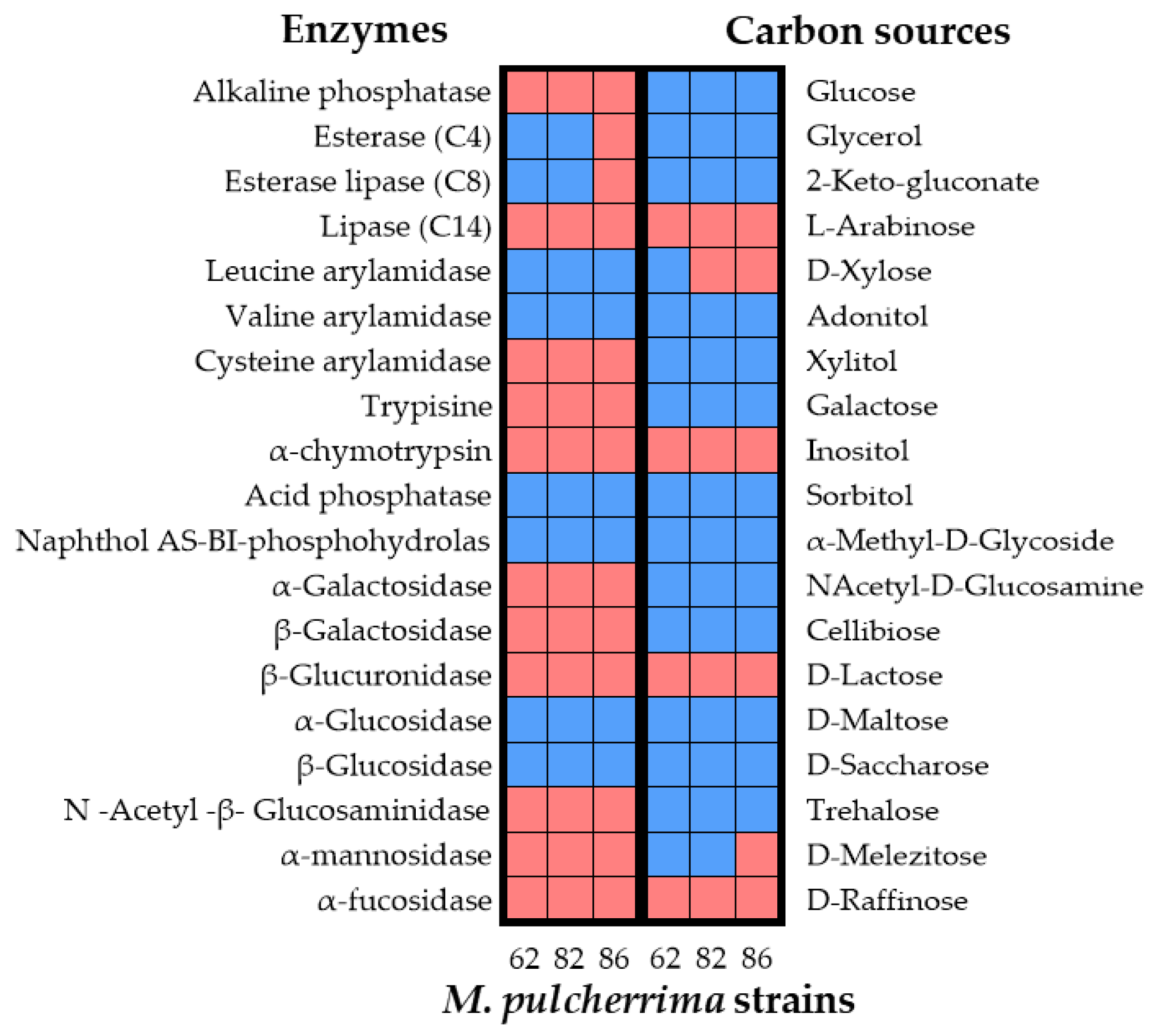

3.1. Technological and Biochemical Properties

3.2. Main Chemical Parameters of Beers

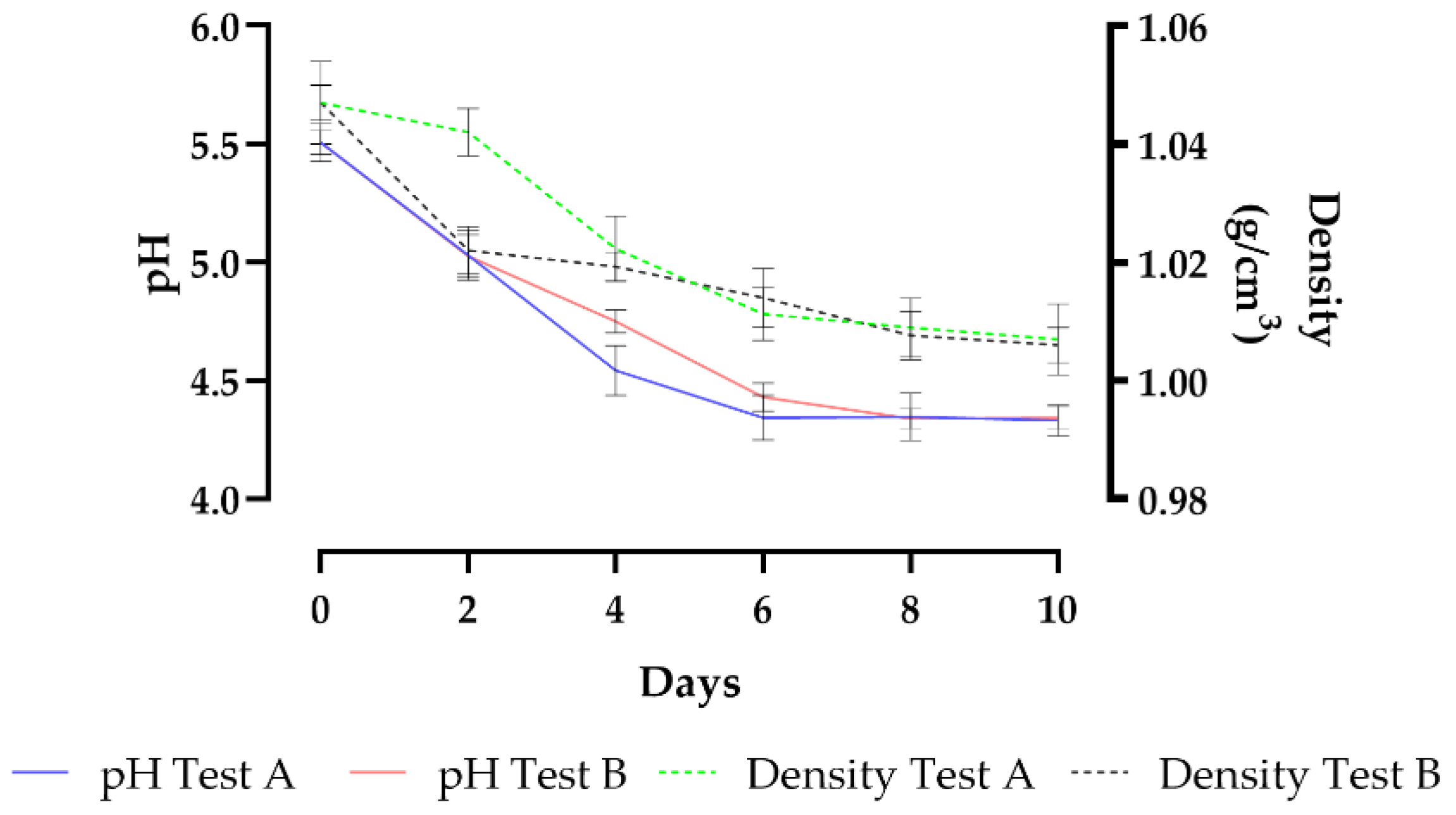

3.3. Fermentation Kinetics

3.4. Volatile Compounds

5. Conclusions

Supplementary Materials

Author Contributions

Funding

Institutional Review Board Statement

Informed Consent Statement

Data Availability Statement

Conflicts of Interest

References

- Garavaglia, C.; Swinnen, J. 216Industry Concentration and the Entry of Craft Producers into the Global Beer Market. In New Developments in the Brewing Industry: The Role of Institutions and Ownership; Madsen, E.S., Gammelgaard, J., Hobdari, B., Eds.; Oxford University Press, 2020; p. 0. ISBN 978-0-19-885460-9. [Google Scholar]

- Aquilani, B.; Laureti, T.; Poponi, S.; Secondi, L. Beer Choice and Consumption Determinants When Craft Beers Are Tasted: An Exploratory Study of Consumer Preferences. Food Qual. Prefer. 2015, 41, 214–224. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Baiano, A. Craft Beer: An Overview. Compr. Rev. Food Sci. Food Saf. 2021, 20, 1829–1856. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Villacreces, S.; Blanco, C.A.; Caballero, I. Developments and Characteristics of Craft Beer Production Processes. Food Biosci. 2022, 45, 101495. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- De Simone, N.; Russo, P.; Tufariello, M.; Fragasso, M.; Solimando, M.; Capozzi, V.; Grieco, F.; Spano, G. Autochthonous Biological Resources for the Production of Regional Craft Beers: Exploring Possible Contributions of Cereals, Hops, Microbes, and Other Ingredients. Foods 2021, 10, 1831. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Puligundla, P.; Smogrovicova, D.; Mok, C. Recent Innovations in the Production of Selected Specialty (Non-Traditional) Beers. Folia Microbiol. (Praha) 2021, 66, 525–541. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Díaz, A.B.; Durán-Guerrero, E.; Lasanta, C.; Castro, R. From the Raw Materials to the Bottled Product: Influence of the Entire Production Process on the Organoleptic Profile of Industrial Beers. Foods 2022, 11, 3215. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Iorizzo, M.; Coppola, F.; Letizia, F.; Testa, B.; Sorrentino, E. Role of Yeasts in the Brewing Process: Tradition and Innovation. Processes 2021, 9, 839. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Larroque, M.; Carrau, F.; Fariña, L.; Boido, E.; Dellacassa, E.; Medina, K. Effect of Saccharomyces and Non-Saccharomyces Native Yeasts on Beer Aroma Compounds. Int. J. Food Microbiol. 2021, 337, 108953. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Methner, Y.; Hutzler, M.; Zarnkow, M.; Prowald, A.; Endres, F.; Jacob, F. Investigation of Non-Saccharomyces Yeast Strains for Their Suitability for the Production of Non-Alcoholic Beers with Novel Flavor Profiles. J. Am. Soc. Brew. Chem. 2022, 80, 341–355. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Iorizzo, M.; Letizia, F.; Albanese, G.; Coppola, F.; Gambuti, A.; Testa, B.; Aversano, R.; Forino, M.; Coppola, R. Potential for Lager Beer Production from Saccharomyces cerevisiae Strains Isolated from the Vineyard Environment. Processes 2021, 9, 1628. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Vanderhaegen, B.; Neven, H.; Verachtert, H.; Derdelinckx, G. The Chemistry of Beer Aging–a Critical Review. Food Chem. 2006, 95, 357–381. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Bellut, K.; Arendt, E.K. Chance and Challenge: Non-Saccharomyces Yeasts in Nonalcoholic and Low Alcohol Beer Brewing–A Review. J. Am. Soc. Brew. Chem. 2019, 77, 77–91. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Blanco, C.A.; Andrés-Iglesias, C.; Montero, O. Low-Alcohol Beers: Flavor Compounds, Defects, and Improvement Strategies. Crit. Rev. Food Sci. Nutr. 2016, 56, 1379–1388. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Basso, R.F.; Alcarde, A.R.; Portugal, C.B. Could Non-Saccharomyces Yeasts Contribute on Innovative Brewing Fermentations? Food Res. Int. 2016, 86, 112–120. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Holt, S.; Mukherjee, V.; Lievens, B.; Verstrepen, K.J.; Thevelein, J.M. Bioflavoring by Non-Conventional Yeasts in Sequential Beer Fermentations. Food Microbiol. 2018, 72, 55–66. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Johansson, L.; Nikulin, J.; Juvonen, R.; Krogerus, K.; Magalhães, F.; Mikkelson, A.; Nuppunen-Puputti, M.; Sohlberg, E.; de Francesco, G.; Perretti, G. Sourdough Cultures as Reservoirs of Maltose-Negative Yeasts for Low-Alcohol Beer Brewing. Food Microbiol. 2021, 94, 103629. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Testa, B.; Coppola, F.; Letizia, F.; Albanese, G.; Karaulli, J.; Ruci, M.; Pistillo, M.; Germinara, G.S.; Messia, M.C.; Succi, M. Versatility of Saccharomyces cerevisiae 41CM in the Brewery Sector: Use as a Starter for “Ale” and “Lager” Craft Beer Production. Processes 2022, 10, 2495. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Sánchez-Adriá, I.E.; Sanmartín, G.; Prieto, J.A.; Estruch, F.; Randez-Gil, F. Sourdough Yeast Strains Exhibit Thermal Tolerance, High Fermentative Performance, and a Distinctive Aromatic Profile in Beer Wort. Foods 2024, 13, 1059. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Postigo, V.; García, M.; Cabellos, J.M.; Arroyo, T. Wine Saccharomyces Yeasts for Beer Fermentation. Fermentation 2021, 7, 290. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Matraxia, M.; Alfonzo, A.; Prestianni, R.; Francesca, N.; Gaglio, R.; Todaro, A.; Alfeo, V.; Perretti, G.; Columba, P.; Settanni, L. Non-Conventional Yeasts from Fermented Honey by-Products: Focus on Hanseniaspora uvarum Strains for Craft Beer Production. Food Microbiol. 2021, 99, 103806. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Rossi, S.; Turchetti, B.; Sileoni, V.; Marconi, O.; Perretti, G. Evaluation of Saccharomyces cerevisiae Strains Isolated from Non-brewing Environments in Beer Production. J. Inst. Brew. 2018, 124, 381–388. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Cubillos, F.A.; Gibson, B.; Grijalva-Vallejos, N.; Krogerus, K.; Nikulin, J. Bioprospecting for Brewers: Exploiting Natural Diversity for Naturally Diverse Beers. Yeast 2019, 36, 383–398. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Canonico, L.; Zannini, E.; Ciani, M.; Comitini, F. Assessment of Non-Conventional Yeasts with Potential Probiotic for Protein-Fortified Craft Beer Production. Lwt 2021, 145, 111361. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Drosou, F.; Mamma, D.; Oreopoulou, V.; Tataridis, P.; Dourtoglou, V. Metschnikowia pulcherrima: A New Yeast for Brewing. 2023. [Google Scholar]

- Canonico, L.; Agarbati, A.; Galli, E.; Comitini, F.; Ciani, M. Metschnikowia pulcherrima as Biocontrol Agent and Wine Aroma Enhancer in Combination with a Native Saccharomyces cerevisiae. LWT 2023, 181, 114758. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Puyo, M.; Simonin, S.; Bach, B.; Klein, G.; Alexandre, H.; Tourdot-Maréchal, R. Bio-Protection in Oenology by Metschnikowia pulcherrima: From Field Results to Scientific Inquiry. Front. Microbiol. 2023, 14, 1252973. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Hranilovic, A.; Gambetta, J.M.; Jeffery, D.W.; Grbin, P.R.; Jiranek, V. Lower-Alcohol Wines Produced by Metschnikowia pulcherrima and Saccharomyces cerevisiae Co-Fermentations: The Effect of Sequential Inoculation Timing. Int. J. Food Microbiol. 2020, 329, 108651. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Testa, B.; Coppola, F.; Iorizzo, M.; Di Renzo, M.; Coppola, R.; Succi, M. Preliminary Characterisation of Metschnikowia pulcherrima to Be Used as a Starter Culture in Red Winemaking. Beverages 2024, 10, 88. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Drosou, F.; Mamma, D.; Tataridis, P.; Dourtoglou, V.; Oreopoulou, V. Metschnikowia pulcherrima in Mono or Co-Fermentations in Brewing. 2022; 75, 69–76. [Google Scholar]

- Postigo, V.; Sánchez, A.; Cabellos, J.M.; Arroyo, T. New Approaches for the Fermentation of Beer: Non-Saccharomyces Yeasts from Wine. Fermentation 2022, 8, 280. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Einfalt, D. Barley-Sorghum Craft Beer Production with Saccharomyces cerevisiae, Torulaspora delbrueckii and Metschnikowia pulcherrima Yeast Strains. Eur. Food Res. Technol. 2021, 247, 385–393. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Hlangwani, E.; du Plessis, H.W.; Dlamini, B.C. The Effect of Selected Non-Saccharomyces Yeasts and Cold-Contact Fermentation on the Production of Low-Alcohol Marula Fruit Beer. Heliyon 2024, 10, e24505. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Karaulli, J.; Xhaferaj, N.; Ruci, M.; Testa, B.; Letizia, F.; Albanese, G.; Kongoli, R.; Lamçe, F.; Kyçyk, O.; Sulaj, K.; et al. Evaluation Of Saccharomyces and Non-Saccharomyces Yeasts Isolated from Albanian Autochthonous Grape Varieties for Craft Beer Production. In Proceedings of the Proceedings of V International Agricultural, Biological, Life Science Conference (AGBIOL); pp. 2023654–665.

- Barbosa, C.; Lage, P.; Esteves, M.; Chambel, L.; Mendes-Faia, A.; Mendes-Ferreira, A. Molecular and Phenotypic Characterization of Metschnikowia pulcherrima Strains from Douro Wine Region. Fermentation 2018, 4, 8. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Comitini, F.; Gobbi, M.; Domizio, P.; Romani, C.; Lencioni, L.; Mannazzu, I.; Ciani, M. Selected Non-Saccharomyces Wine Yeasts in Controlled Multistarter Fermentations with Saccharomyces cerevisiae. Food Microbiol. 2011, 28, 873–882. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Mažeika, K.; Šiliauskas, L.; Skridlaitė, G.; Matelis, A.; Garjonytė, R.; Paškevičius, A.; Melvydas, V. Features of Iron Accumulation at High Concentration in Pulcherrimin-Producing Metschnikowia Yeast Biomass. JBIC J. Biol. Inorg. Chem. 2021, 26, 299–311. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Gut, A.M.; Vasiljevic, T.; Yeager, T.; Donkor, O.N. Characterization of Yeasts Isolated from Traditional Kefir Grains for Potential Probiotic Properties. J. Funct. Foods 2019, 58, 56–66. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Testa, B.; Lombardi, S.J.; Iorizzo, M.; Letizia, F.; Di Martino, C.; Di Renzo, M.; Strollo, D.; Tremonte, P.; Pannella, G.; Ianiro, M. Use of Strain Hanseniaspora Guilliermondii BF1 for Winemaking Process of White Grapes Vitis Vinifera Cv Fiano. Eur. Food Res. Technol. 2020, 246, 549–561. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Belda, I.; Ruiz, J.; Navascués, E.; Marquina, D.; Santos, A. Improvement of Aromatic Thiol Release through the Selection of Yeasts with Increased β-Lyase Activity. Int. J. Food Microbiol. 2016, 225, 1–8. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- López-Enríquez, L.; Vila-Crespo, J.; Rodríguez-Nogales, J.M.; Fernández-Fernández, E.; Ruipérez, V. Screening and Enzymatic Evaluation of Saccharomyces cerevisiae Populations from Spontaneous Fermentation of Organic Verdejo Wines. Foods 2022, 11, 3448. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Strong, G.; England, K. Beer Judge Certification Program: 2015 Style Guidelines. Brew Assoc 2015, 47. [Google Scholar]

- European Brewery, Convention. Analytica - EBC; Hans Carl, Fachverlag: Nürnberg, 2007; ISBN 3-418-00759-7. [Google Scholar]

- Paszkot, J.; Gasiński, A.; Kawa-Rygielska, J. Evaluation of Volatile Compound Profiles and Sensory Properties of Dark and Pale Beers Fermented by Different Strains of Brewing Yeast. Sci. Rep. 2023, 13, 6725. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Kucharczyk, K.; Tuszyński, T. The Effect of Temperature on Fermentation and Beer Volatiles at an Industrial Scale. J. Inst. Brew. 2018, 124, 230–235. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Du, Q.; Ye, D.; Zang, X.; Nan, H.; Liu, Y. Effect of Low Temperature on the Shaping of Yeast-Derived Metabolite Compositions during Wine Fermentation. Food Res. Int. 2022, 162, 112016. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Wang, B.; Tan, F.; Chu, R.; Li, G.; Li, L.; Yang, T.; Zhang, M. The Effect of Non-Saccharomyces Yeasts on Biogenic Amines in Wine. Trends Food Sci. Technol. 2021, 116, 1029–1040. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Nalazek-Rudnicka, K.; Wojnowski, W.; Wasik, A. Occurrence and Levels of Biogenic Amines in Beers Produced by Different Methods. Foods 2021, 10, 2902. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Matukas, M.; Starkute, V.; Zokaityte, E.; Zokaityte, G.; Klupsaite, D.; Mockus, E.; Rocha, J.M.; Ruibys, R.; Bartkiene, E. Effect of Different Yeast Strains on Biogenic Amines, Volatile Compounds and Sensory Profile of Beer. Foods 2022, 11, 2317. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Tsafack, P.B.; Tsopmo, A. Effects of Bioactive Molecules on the Concentration of Biogenic Amines in Foods and Biological Systems. Heliyon 2022, 8. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Vasconcelos, H.; de Almeida, J.M.; Matias, A.; Saraiva, C.; Jorge, P.A.; Coelho, L.C. Detection of Biogenic Amines in Several Foods with Different Sample Treatments: An Overview. Trends Food Sci. Technol. 2021, 113, 86–96. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- EFSA Panel on Biological Hazards, (BIOHAZ). Scientific Opinion on Risk Based Control of Biogenic Amine Formation in Fermented Foods. Efsa J. 2011, 9, 2393. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Wang, C.; Liu, M.; Li, Y.; Zhang, Y.; Yao, M.; Qin, Y.; Liu, Y. Hydrogen Sulfide Synthesis in Native Saccharomyces cerevisiae Strains during Alcoholic Fermentations. Food Microbiol. 2018, 70, 206–213. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Pawlikowska, E.; Kolesińska, B.; Nowacka, M.; Kregiel, D. A New Approach to Producing High Yields of Pulcherrimin from Metschnikowia Yeasts. Fermentation 2020, 6, 114. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Oro, L.; Ciani, M.; Comitini, F. Antimicrobial Activity of Metschnikowia pulcherrima on Wine Yeasts. J. Appl. Microbiol. 2014, 116, 1209–1217. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Morata, A.; Loira, I.; Escott, C.; del Fresno, J.M.; Bañuelos, M.A.; Suárez-Lepe, J.A. Applications of Metschnikowia pulcherrima in Wine Biotechnology. Fermentation 2019, 5, 63. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Nardi, T. Microbial Resources as a Tool for Enhancing Sustainability in Winemaking. Microorganisms 2020, 8, 507. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Yuan, S.; Yong, X.; Zhao, T.; Li, Y.; Liu, J. Research Progress of the Biosynthesis of Natural Bio-Antibacterial Agent Pulcherriminic Acid in Bacillus. Molecules 2020, 25, 5611. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Benoit, I.; Danchin, E.G.; Bleichrodt, R.-J.; de Vries, R.P. Biotechnological Applications and Potential of Fungal Feruloyl Esterases Based on Prevalence, Classification and Biochemical Diversity. Biotechnol. Lett. 2008, 30, 387–396. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Dank, A.; Smid, E.J.; Notebaart, R.A. CRISPR-Cas Genome Engineering of Esterase Activity in Saccharomyces cerevisiae Steers Aroma Formation. BMC Res. Notes 2018, 11, 1–6. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Han, X.; Qin, Q.; Li, C.; Zhao, X.; Song, F.; An, M.; Chen, Y.; Wang, X.; Huang, W.; Zhan, J. Application of Non-Saccharomyces Yeasts with High β-Glucosidase Activity to Enhance Terpene-Related Floral Flavor in Craft Beer. Food Chem. 2023, 404, 134726. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- He, Y.; Dong, J.; Yin, H.; Zhao, Y.; Chen, R.; Wan, X.; Chen, P.; Hou, X.; Liu, J.; Chen, L. Wort Composition and Its Impact on the Flavour-active Higher Alcohol and Ester Formation of Beer–a Review. J. Inst. Brew. 2014, 120, 157–163. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Michel, M.; Haslbeck, K.; Ampenberger, F.; Meier-Dörnberg, T.; Stretz, D.; Hutzler, M.; Coelhan, M.; Jacob, F.; Liu, Y. Screening of Brewing Yeast β-Lyase Activity and Release of Hop Volatile Thiols from Precursors during Fermentation. 2019. [Google Scholar]

- Krogerus, K.; Rettberg, N.; Gibson, B. Increased Volatile Thiol Release during Beer Fermentation Using Constructed Interspecies Yeast Hybrids. Eur. Food Res. Technol. 2023, 249, 55–69. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Bonnaffoux, H.; Roland, A.; Schneider, R.; Cavelier, F. Spotlight on Release Mechanisms of Volatile Thiols in Beverages. Food Chem. 2021, 339, 127628. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Buiatti, S.; Tat, L.; Natolino, A.; Passaghe, P. Biotransformations Performed by Yeasts on Aromatic Compounds Provided by Hop—A Review. Fermentation 2023, 9, 327. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Muñoz-Redondo, J.M.; Puertas, B.; Cantos-Villar, E.; Jiménez-Hierro, M.J.; Carbú, M.; Garrido, C.; Ruiz-Moreno, M.J.; Moreno-Rojas, J.M. Impact of Sequential Inoculation with the Non-Saccharomyces T. delbrueckii and M. pulcherrima Combined with Saccharomyces cerevisiae Strains on Chemicals and Sensory Profile of Rosé Wines. J. Agric. Food Chem. 2021, 69, 1598–1609. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Ciani, M.; Capece, A.; Comitini, F.; Canonico, L.; Siesto, G.; Romano, P. Yeast Interactions in Inoculated Wine Fermentation. Front. Microbiol. 2016, 7, 555. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Mencher, A.; Morales, P.; Curiel, J.A.; Gonzalez, R.; Tronchoni, J. Metschnikowia Pulcherrima Represses Aerobic Respiration in Saccharomyces cerevisiae Suggesting a Direct Response to Co-Cultivation. Food Microbiol. 2021, 94, 103670. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Ivit, N.N.; Longo, R.; Kemp, B. The Effect of Non-Saccharomyces and Saccharomyces Non-cerevisiae Yeasts on Ethanol and Glycerol Levels in Wine. Fermentation 2020, 6, 77. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Sadoudi, M.; Rousseaux, S.; David, V.; Alexandre, H.; Tourdot-Maréchal, R. Metschnikowia pulcherrima Influences the Expression of Genes Involved in PDH Bypass and Glyceropyruvic Fermentation in Saccharomyces cerevisiae. Front. Microbiol. 2017, 8, 1137. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Schreurs, M.; Piampongsant, S.; Roncoroni, M.; Cool, L.; Herrera-Malaver, B.; Vanderaa, C.; Theßeling, F.A.; Kreft, Ł.; Botzki, A.; Malcorps, P. Predicting and Improving Complex Beer Flavor through Machine Learning. Nat. Commun. 2024, 15, 2368. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Zhao, X.; Procopio, S.; Becker, T. Flavor Impacts of Glycerol in the Processing of Yeast Fermented Beverages: A Review. J. Food Sci. Technol. 2015, 52, 7588–7598. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Du Plessis, H.; Du Toit, M.; Hoff, J.; Hart, R.; Ndimba, B.; Jolly, N. Characterisation of Non-Saccharomyces Yeasts Using Different Methodologies and Evaluation of Their Compatibility with Malolactic Fermentation. South Afr. J. Enol. Vitic. 2017, 38, 46–63. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Benito, S.; Hofmann, T.; Laier, M.; Lochbühler, B.; Schüttler, A.; Ebert, K.; Fritsch, S.; Röcker, J.; Rauhut, D. Effect on Quality and Composition of Riesling Wines Fermented by Sequential Inoculation with Non-Saccharomyces and Saccharomyces cerevisiae. Eur. Food Res. Technol. 2015, 241, 707–717. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Michel, M.; Meier-Dörnberg, T.; Jacob, F.; Methner, F.; Wagner, R.S.; Hutzler, M. Pure non-Saccharomyces Starter Cultures for Beer Fermentation with a Focus on Secondary Metabolites and Practical Applications. J. Inst. Brew. 2016, 122, 569–587. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Engan, S. Organoleptic Threshold Values of Some Organic Acids in Beer. J. Inst. Brew. 1974, 80, 162–163. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Olaniran, A.O.; Hiralal, L.; Mokoena, M.P.; Pillay, B. Flavour-active Volatile Compounds in Beer: Production, Regulation and Control. J. Inst. Brew. 2017, 123, 13–23. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Stewart, G.G. The Production of Secondary Metabolites with Flavour Potential during Brewing and Distilling Wort Fermentations. Fermentation 2017, 3, 63. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Gernat, D.; Brouwer, E.; Ottens, M. Aldehydes as Wort Off-Flavours in Alcohol-Free Beers—Origin and Control. Food Bioprocess Technol. 2020, 13, 195–216. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Edgar, M.; Wycliffe, A. Investigating the Impact of Acetaldehyde Accumulation on Beer Quality: Metabolic Pathways, Yeast Health, and Mitigation Strategies. 2024; 11, 40–51. [Google Scholar]

- Comitini, F.; Agarbati, A.; Canonico, L.; Ciani, M. Yeast Interactions and Molecular Mechanisms in Wine Fermentation: A Comprehensive Review. Int. J. Mol. Sci. 2021, 22, 7754. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Pires, E.J.; Teixeira, J.A.; Brányik, T.; Vicente, A.A. Yeast: The Soul of Beer’s Aroma—A Review of Flavour-Active Esters and Higher Alcohols Produced by the Brewing Yeast. Appl. Microbiol. Biotechnol. 2014, 98, 1937–1949. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Holt, S.; Miks, M.H.; de Carvalho, B.T.; Foulquie-Moreno, M.R.; Thevelein, J.M. The Molecular Biology of Fruity and Floral Aromas in Beer and Other Alcoholic Beverages. FEMS Microbiol. Rev. 2019, 43, 193–222. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Roberts, R.; Khomenko, I.; Eyres, G.T.; Bremer, P.; Silcock, P.; Betta, E.; Biasioli, F. Online Monitoring of Higher Alcohols and Esters throughout Beer Fermentation by Commercial Saccharomyces cerevisiae and Saccharomyces pastorianus Yeast. J. Mass Spectrom. 2023, 58, e4959. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Postigo, V.; Sanz, P.; García, M.; Arroyo, T. Impact of Non-Saccharomyces Wine Yeast Strains on Improving Healthy Characteristics and the Sensory Profile of Beer in Sequential Fermentation. Foods 2022, 11, 2029. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Verstrepen, K.J.; Derdelinckx, G.; Dufour, J.-P.; Winderickx, J.; Thevelein, J.M.; Pretorius, I.S.; Delvaux, F.R. Flavor-Active Esters: Adding Fruitiness to Beer. J. Biosci. Bioeng. 2003, 96, 110–118. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Viejo, C.G.; Fuentes, S.; Torrico, D.D.; Godbole, A.; Dunshea, F.R. Chemical Characterization of Aromas in Beer and Their Effect on Consumers Liking. Food Chem. 2019, 293, 479–485. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Brányik, T.; Vicente, A.A.; Dostálek, P.; Teixeira, J.A. A Review of Flavour Formation in Continuous Beer Fermentations. J. Inst. Brew. 2008, 114, 3–13. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Ocvirk, M.; Mlinarič, N.K.; Košir, I.J. Comparison of Sensory and Chemical Evaluation of Lager Beer Aroma by Gas Chromatography and Gas Chromatography/Mass Spectrometry. J. Sci. Food Agric. 2018, 98, 3627–3635. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Meilgaard, M.C. Prediction of Flavor Differences between Beers from Their Chemical Composition. J. Agric. Food Chem. 1982, 30, 1009–1017. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Siebert, K.J. Modeling the Flavor Thresholds of Organic Acids in Beer as a Function of Their Molecular Properties. Food Qual. Prefer. 1999, 10, 129–137. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Bravi, E.; Benedetti, P.; Marconi, O.; Perretti, G. Determination of Free Fatty Acids in Beer Wort. Food Chem. 2014, 151, 374–378. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Wilde, P.; Husband, F.; Cooper, D.; Ridout, M.; Muller, R.; Mills, E. Destabilization of Beer Foam by Lipids: Structural and Interfacial Effects. J. Am. Soc. Brew. Chem. 2003, 61, 196–202. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Gordon, R.; Power, A.; Chapman, J.; Chandra, S.; Cozzolino, D. A Review on the Source of Lipids and Their Interactions during Beer Fermentation That Affect Beer Quality. Fermentation 2018, 4, 89. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Olšovská, J.; Vrzal, T.; Štěrba, K.; Slabý, M.; Kubizniaková, P.; Čejka, P. The Chemical Profiling of Fatty Acids during the Brewing Process. J. Sci. Food Agric. 2019, 99, 1772–1779. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

|

M. pulcherrima strains |

H2S* | β -Glucosidase** | β -Lyase** | Protease** | Pulcherrimin** | Cryotolerance** |

| 62 | 2 | + | + | + | + | + |

| 82 | 2 | weak | + | - | + | weak |

| 86 | 2 | weak | + | + | + | weak |

| physical-chemical parameters | Test A | Test B |

| pH | 4.35 ± 0.05 a | 4.31 ± 0.06 a |

| Alcohol (% v/v) | 5.20 ± 0.10 a | 5.00 ± 0.10 a |

| Acetic acid (mg/L) | 60.66 ± 3.51 a | 58.83 ± 1.25 a |

| L-malic acid (mg/L) | 160.33 ± 2.51 b | 202.33 ± 7.50 a |

| L-lactic acid (mg/L) | 115.66 ± 5.13 a | 115.50 ± 2.29 a |

| Glycerol (mg/L) | 1026.02 ± 28.21 a | 892.66 ± 9.60 b |

| Acetaldehyde (mg/L) | 7.66 ± 0.80 a | 7.70 ± 0.19 a |

| Fermentation time (days) | |||||||

| 0 | 2 | 4 | 6 | 8 | 10 | ||

| Test A | M. pulcherrima | 6.12 ± 0.13 b | 6.93 ± 0.25 a | 6.33 ± 0.15 b | 4.02 ± 0.14 c | 0.00 ±0.00 d | 0.00 ± 0.00 d |

| S. cerevisiae | 0.00 ±.0.00 d | 6.75 ± 0.25 c | 7.54 ± 0.23 b | 8.27 ± 0.30 a | 8.85 ± 0.15 a | 7.62 ± 0.20 b | |

| Test B | S. cerevisiae | 6.83 ± 0.15 c | 6.88 ± 0.20 c | 7.86 ± 0.35 b | 8.52 ± 0.33 a | 7.88 ± 0.10 a | 7.73 ± 0.15 b |

| Class of organic compounds | Volatile compounds | Test A | Test B |

| Higher alcohols | Isobutanol | 42.26 ± 0.75 a | 11.44 ± 0.55 b |

| Isoamyl alcohol | 101.83 ± 1.55 a | 53.02 ± 2.01 b | |

| 1-Hexanol | nd | 1.23 ± 0.10 a | |

| Esters | β-phenylethanol | 21.10 ± 1.86 b | 34.77 ±1.71a |

| Ethyl acetate | 1.31 ± 0.18 a | 0.68 ± 0.04 b | |

| Ethyl isovalerate | 0.24 ± 0.06 a | 0.17 ± 0.03 a | |

| Ethyl butirate | 0.24 ± 0.05 a | 0.34 ± 0.03 a | |

| Ethyl lactate | nd | 0.56 ± 0.06 a | |

| Isoamyl acetate | 2.50 ± 0.14 a | 1.88 ± 0.04 b | |

| Ethyl hexanoate | 0.03 ± 0.01 a | 0.05 ± 0.01 a | |

| Ethyl octanoate | 0.13 ± 0.02 b | 0.24 ± 0.01 a | |

| Diethyl succinate | 0.34 ± 0.04 a | 0.22 ± 0.02 b | |

| Fatty acids | Butyric acid | 1.80 ± 0.08 a | 0.11 ± 0.02 b |

| Hexanoic acid | 2.30 ± 0.12 a | 0.65 ± 0.05 b | |

| Octanoic acid | 1.13 ± 0.10 b | 1.94 ± 0.05 a | |

| Decanoic acid | 0.47 ± 0.08 a | 0.30 ± 0.04 a | |

| Aldehydes/Ketones | Diacetyl | 0.11 ± 0.04 a | 0.12 ± 0.03 a |

| Acetoin | 0.84 ± 0.05 a | 0.64 ± 0.08 b |

Disclaimer/Publisher’s Note: The statements, opinions and data contained in all publications are solely those of the individual author(s) and contributor(s) and not of MDPI and/or the editor(s). MDPI and/or the editor(s) disclaim responsibility for any injury to people or property resulting from any ideas, methods, instructions or products referred to in the content. |

© 2024 by the authors. Licensee MDPI, Basel, Switzerland. This article is an open access article distributed under the terms and conditions of the Creative Commons Attribution (CC BY) license (http://creativecommons.org/licenses/by/4.0/).