1. Introduction

CrossFit (CF) workouts are comprised of high intensity and variety functional movements, integrating elements from weightlifting, gymnastics, and cardiovascular exercises aiming to enhance strength, stamina, flexibility, and coordination [

1]. Both aerobic and anaerobic energy systems are engaged, exemplified by benchmark workouts like Isabel, which demand maximal effort and considerable energy expenditure [

2]. CF athletes exhibit a force-velocity profile that is more oriented towards velocity than force, with significant differences in neuromuscular characteristics between males and females, and improvements noted with increased training frequency [

3]. However, overtraining, along with the high variability of exercises and occasionally improper form, have been associated with contributing to overuse injuries [

4,

5].

The prevalence of injuries among CF practitioners varies significantly, with reported rates ranging from 0.2 to 18.9 injuries per 1,000 hours of exposure [

6]. The most affected areas are the shoulders, lower back, and knees, with shoulder injuries being remarkably prevalent, accounting for up to 40.6% of all injuries [

7]. These injuries are often linked to specific exercises, such as Olympic weightlifting and gymnastic movements like kipping pull-ups and ring dips [

7,

8]. These exercises, which are integral to CF routines, place significant stress on the shoulder joint, often leading to overloading and subsequent injuries such as partial lesions of the supraspinatus tendon and labral tears [

9,

10]. The repetitive and extreme positions required in CF, such as overhead movements, are predisposing the shoulder complex to overload and damage [

11]. Additionally, improper training techniques like training with pain and inadequate warm-up routines have been shown to adversely affect injury incidence [

4,

5]. Recent study findings indicated an isokinetic force-power imbalance in favor of internal rotators in the shoulder of advanced CrossFitters [

12]. Scapular dyskinesis, glenohumeral internal rotation deficit and posterior shoulder stiffness which are observed in overhead athletes’ populations can also lead to kinematics alterations and decreased shoulder functionality [

13].

In conclusion, the high prevalence of shoulder injuries in (CF) athletes could be mitigated by systematically recording predisposing factors and elucidating their contribution to injury incidence. Despite an expanding body of research, much of the current literature comprises lower-level evidence, highlighting the need for high-quality study designs [

14]. The present prospective cohort study aimed to develop a representative profile of CF athletes in Greece regarding shoulder injuries. Specifically, we sought to integrate demographic, epidemiological, and functional data to investigate their association with shoulder injury occurrence over a complete training and competition cycle. Following an initial baseline assessment, athletes were monitored prospectively throughout the entire cycle to record shoulder injuries and support the modeling of potential predisposing factors.

3. Results

3.1. Demographics and Injury Incidence

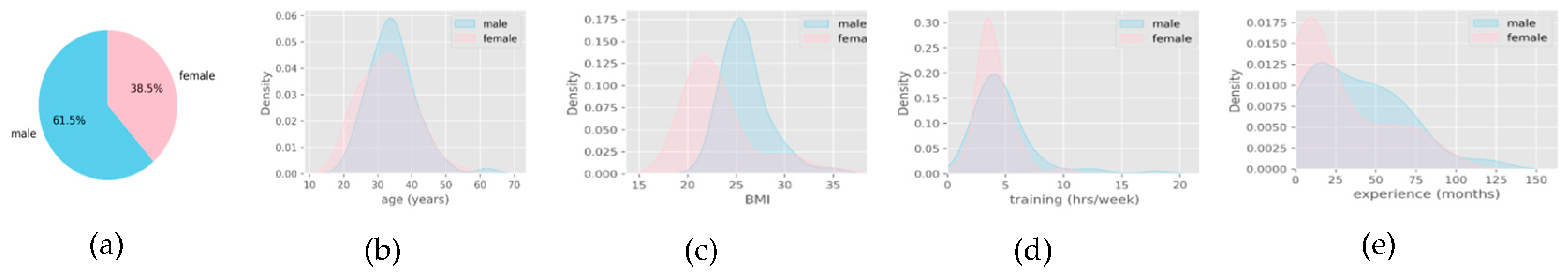

The study included one hundred and nine CrossFitters from four cities in Greece, ten of them (9.2%) being left-hand dominant. A complete demographic profile is illustrated in

Table 1. Twenty-one individuals (19.3%) participated in CF competitions, while the rest were training for health and recreation purposes. Regarding their warm-up and cool-down routines, proportions of 72.5% and 45% of the participants, respectively, declared that they were consistently adhering to both procedures in an adequate manner. Other sports activities, apart from CF, were practiced by 48.6% of the sample. Forty percent (40.4%) of the sample population had a particularly good fitness level before starting CF, and 35.8% started with a low prior fitness level. A fraction of four out of ten participants (N=43, 39.4%) were experiencing shoulder pain during CF workouts.

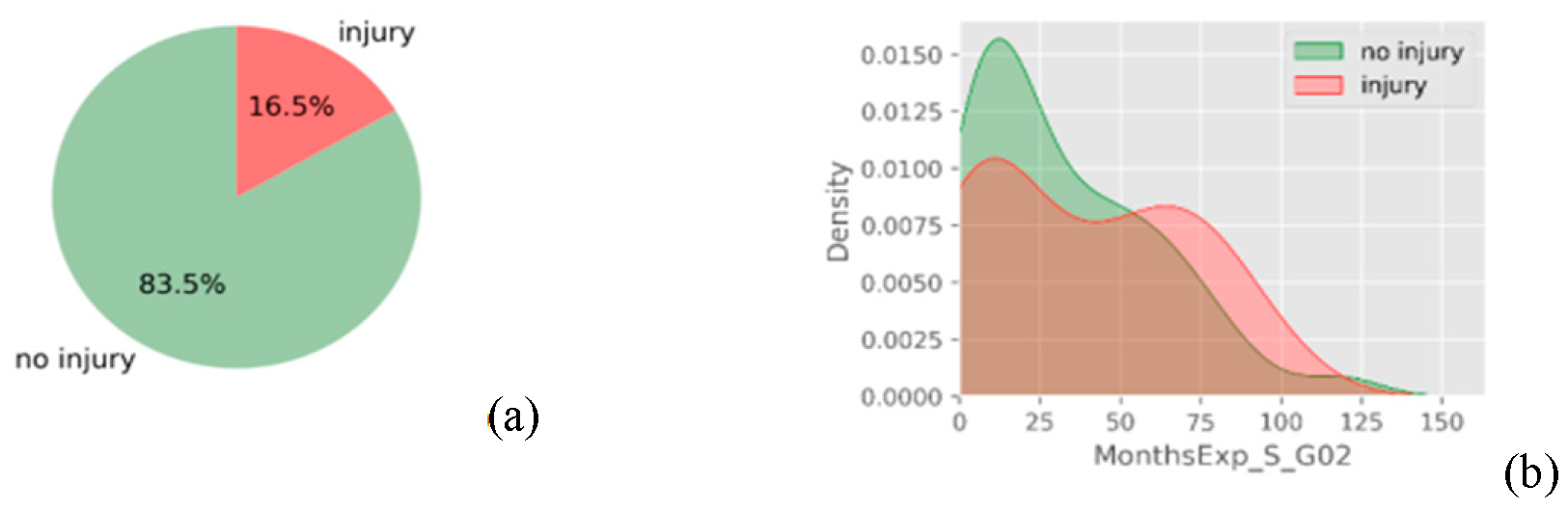

During the observation period, 18 athletes (16.5%) presented with new unilateral shoulder injuries with two individuals experiencing bilateral shoulder involvement, resulting in a cumulative total of 20 shoulder joint injuries. Among these incidents, ten (50%) occurred on the non-dominant shoulder, six on the dominant shoulder and four injuries were bilateral. Injury incidence rate (IIR) of shoulder injuries in this sample of CF athletes was 0.79 per 1,000 training hours.

Six out of the twenty referred shoulder injuries were new, while the rest fourteen were an exacerbation of an old injury. Four injuries were acute, whereas the rest sixteen demonstrated gradual onset as overuse injuries. The occurrence of 45% of the new shoulder injuries was associated with Olympic weightlifting exercises, 35% with gymnastics, and equal percentages of 10% with combination of Olympic weightlifting and gymnastics, and with free weights exercises solely.

In terms of the tissue involved, the most frequent injury (45%) concerned rotator cuff (RC) tendons, including lesions and tendinopathies. The second most prevalent injury, accounting for 40%, was identified as a concomitant injury to the rotator cuff and the biceps tendon. Labral tears and injuries involving both the rotator cuff and the acromioclavicular joint were noted, representing 10% and 5% of cases respectively. The injury severance ranged from the modification of a single day’s workout to the alternation or total cessation of practice for up to 108 days. Only five injured participants (25%) managed to return to sport without pain, while twelve (60%) returned to full practice with pain symptoms, and the remaining three (15%) failed to return to their previous level of practice routines during the observation period. The pain, shoulder disability and days out of practice are shown in

Table 2.

3.2. Exploratory Data Analysis and Descriptive Statistics

During the first stage of statistical analysis potential factors that could influence injury rates were investigated to determine whether further grouping based on variables such as gender, age, experience, or competition level, was necessary. Apart from statistical analysis, PDFs of the binary variables were used to illustrate the degree their distributions overly.

3.2.1. Demographic Data

Regarding gender profile, PDFs of male and female athletes, showed considerable overlapping in age and training volume, visually verifying their non statistically significant difference. The only noticeable observation, however non-significant, was that male athletes exhibited higher BMI values and were slightly more experienced (

Figure 1).

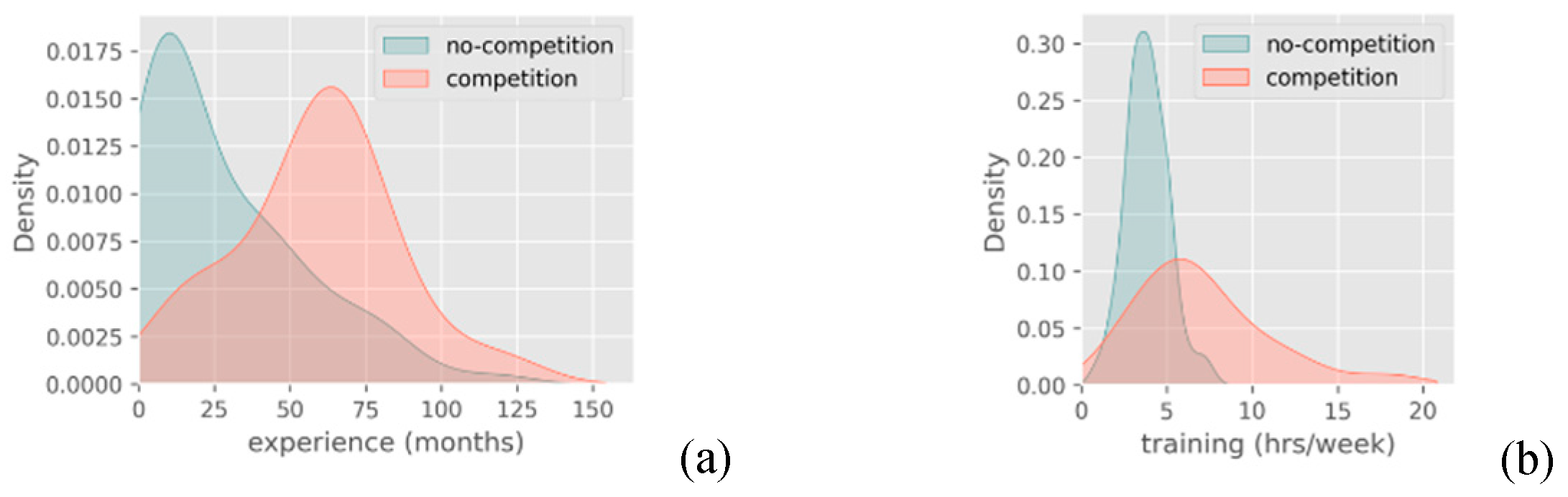

Athletes who participate in competitions exhibited very similar age and BMI distributions with non-competitive athletes. The pattern of PDFs of experience and training hours shifted toward higher values for competitive athletes (

Figure 2). Using a cut-off age of 40 years to separate younger from older athletes, in line with CF scaling [

25,

26], it was noticed that 83.5% of the sample comprised the younger athletes’ category. Experience and training volume variances demonstrated similar distributions across the two age groups, while BMI was slightly higher for older athletes.

During exploratory analysis, athletes who sustained a new shoulder injury and those who did not, were categorized into two groups. Similar overlapping pattern diagrams were reproduced for age, BMI, experience, and training volume between these two groups (

Figure 3).

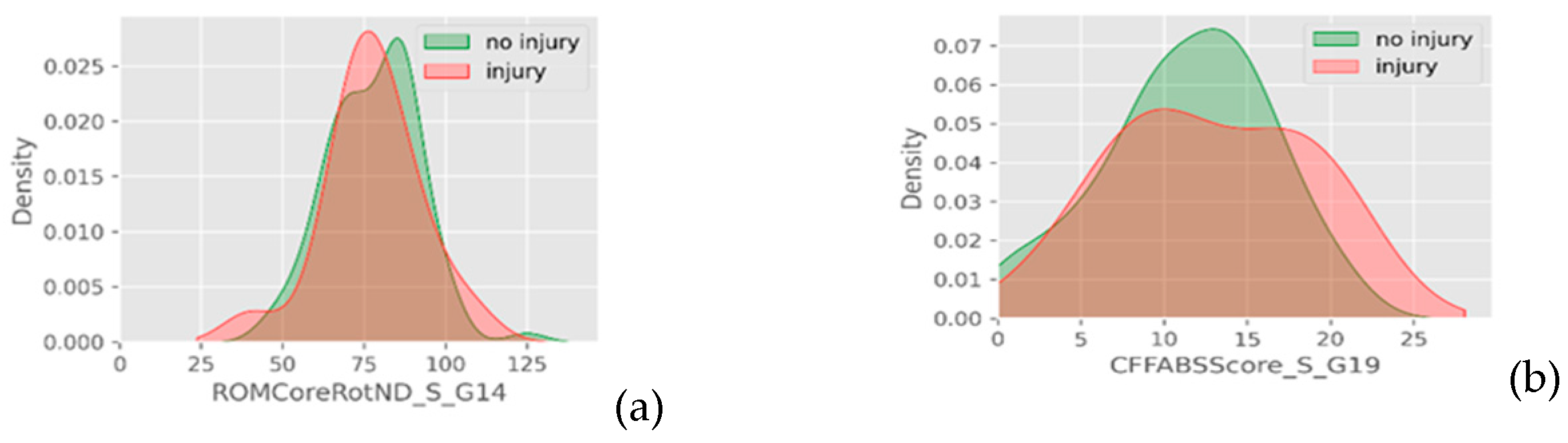

3.2.2. Range of Motion, Strength and Sports-Specific Tests

Overlaying the distributions of the continuous variables of injured (red area) and non-injured (green area) athletes showed them to overlap considerably. In core-rotation ROM toward the side of the non-dominant upper extremity (NDUE), hip abduction strength in both sides and CKCUEST, the two groups appeared nearly identical, while in cases of CF FABS, hip abduction strength deficit, non-dominant shoulder external rotation endurance and shoulder external rotation endurance deficit there was a lower extent of overlap (

Figure 4). However, even in the latter case, differences appeared to be associated with the regions of higher density, i.e., near the peak values of the curves, while the spread along the horizontal axis remained similar. Therefore, we concluded that the PDFs were nearly identical, which strongly indicated that no distinction between injured and non-injured athletes exists, thus they could be examined as a single group.

Despite the differences on PDF overlapping in the aforementioned variables, none of them was statistically significantly associated with shoulder injuries.

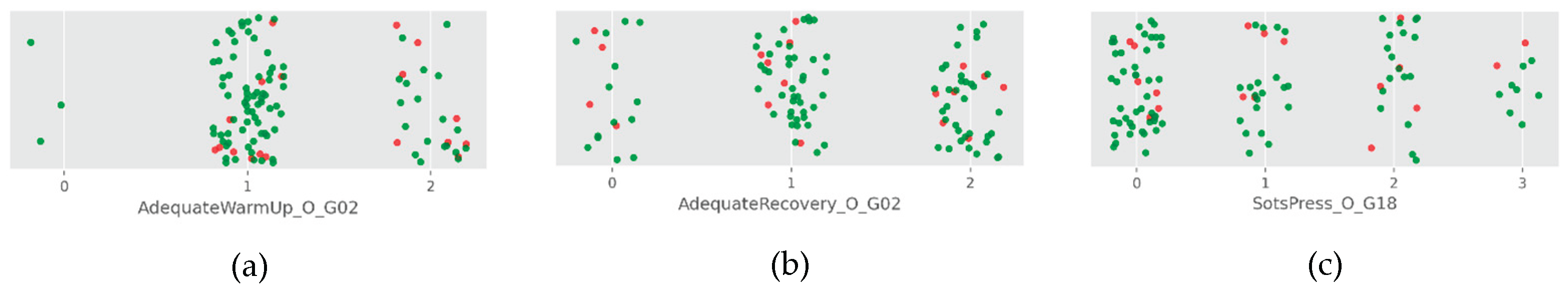

3.2.3. Ordinal Measurements and Data

The resulting visualization of the data allowed the observation of a significant intermixing of injured (red dots) and non-injured (green dots) athletes without a clear pattern distinguishing the two groups. This technique prevented data collapse while preserving the categorical structure, allowing for a clearer distinction between injured and non-injured athletes. As a result, no single measurement, and the corresponding ordinal variable, was sufficient to differentiate between them. Warm up and recovery routines, prior fitness level, injury history on any area of the body, or each one of the individual tests of CF FABS were not correlated to new shoulder injury incidence. An example of this optical demonstration is given in

Figure 5.

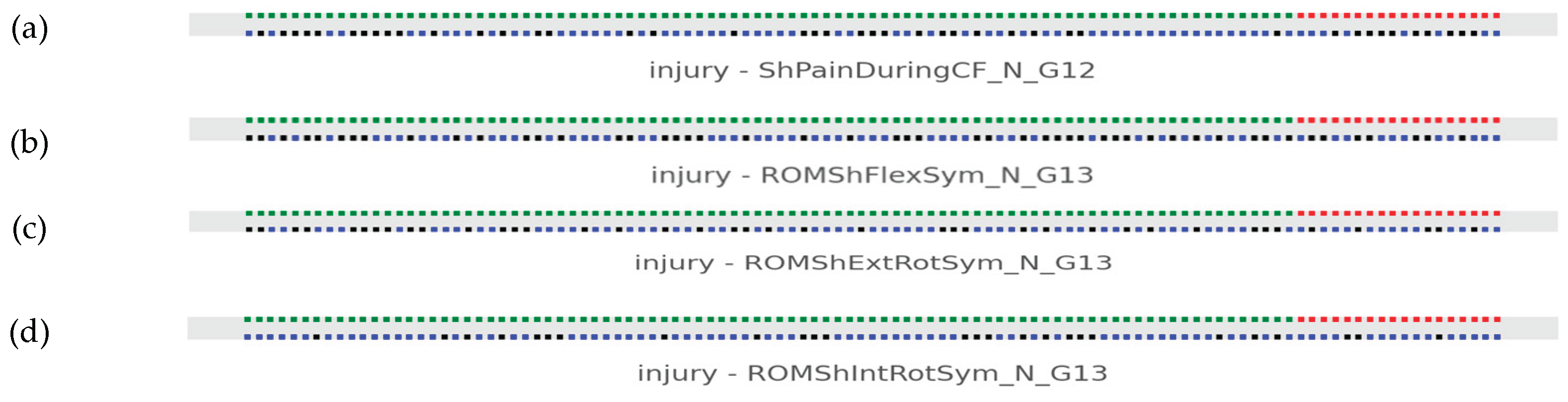

3.2.4. Nominal Data

A typical example of binary categorical data interaction is visually represented in Figure 6. Injured and non-injured athletes were plotted against the binary response of each categorical variable. It was attempted to locate any systematic pattern that could potentially connect the two colored lines; for example, a pattern that blue or black dots favored any of the red or green athletes. It was observed that this pattern was absent in all subplots concerning gender, UE dominance, competitiveness, other parallel activity, and history of general injury. In particular, there was a significant intermixture of binary data across all groups.

3.3. Inferential Statistics

Chi-squared (χ2) tests were conducted to compare the percentages of injured versus non-injured individuals within the following categories: male/female, competitive/non-competitive, and equal and under/over 40 years of age. The findings indicated that a proportion of 19.4% of the male population exhibited a shoulder injury in contrast to the corresponding 11.9% of the female population (χ2=1.053, p=0.305). Moreover, 23.8% of the competitive athletes sustained injuries, as opposed to 14.8% of the non-competitive athletes (χ2=0.219, p=0.640). Nearly identical proportions of younger and older participants (16.5% and 16.7% respectively) displayed shoulder injuries throughout the observational period (χ2<0.001, p=0.985). The p-values for these statistical analyses were notably elevated, suggesting a lack of statistical significance and therefore multiple testing was not further investigated.

Independent t-tests were conducted for the comparisons between continuous variables, with a conservative significance threshold of α=0.05 (

Table 3). Bonferroni’s method adjusted at the level of α=0.0031, instead of 0.05 for 16 multiple tests [

23]. Additionally, the study aimed to assess how rare the observed values of individual ordinal variables were, relative to the expected variability of the test statistic due to random sampling. For this purpose, the Mann-Whitney U test was applied and evaluated the p-values against a conservative significance level of the adjusted α=0.0029, instead of 0.05 for 17 multiple tests (

Table 4). Both testing procedures resulted in very high p-values for most of the variables, considerably higher than the chosen α level (with Bonferroni adjustments), suggesting no significant difference between injured and non-injured athletes.

The low p-values of the hip abductors’ strength deficit, shoulder external rotators’ endurance deficit, warm-up practice, and history of body injuries noted a difference between the tested variables. These may point to a better attitude towards warm-up in CF athletes and a possible relationship between specific deficits or general injury history and shoulder injury incidence. However, after Bonferroni correction due to the high number of comparisons, this difference was not considered statistically significant, but there were some obvious trends which should be considered.

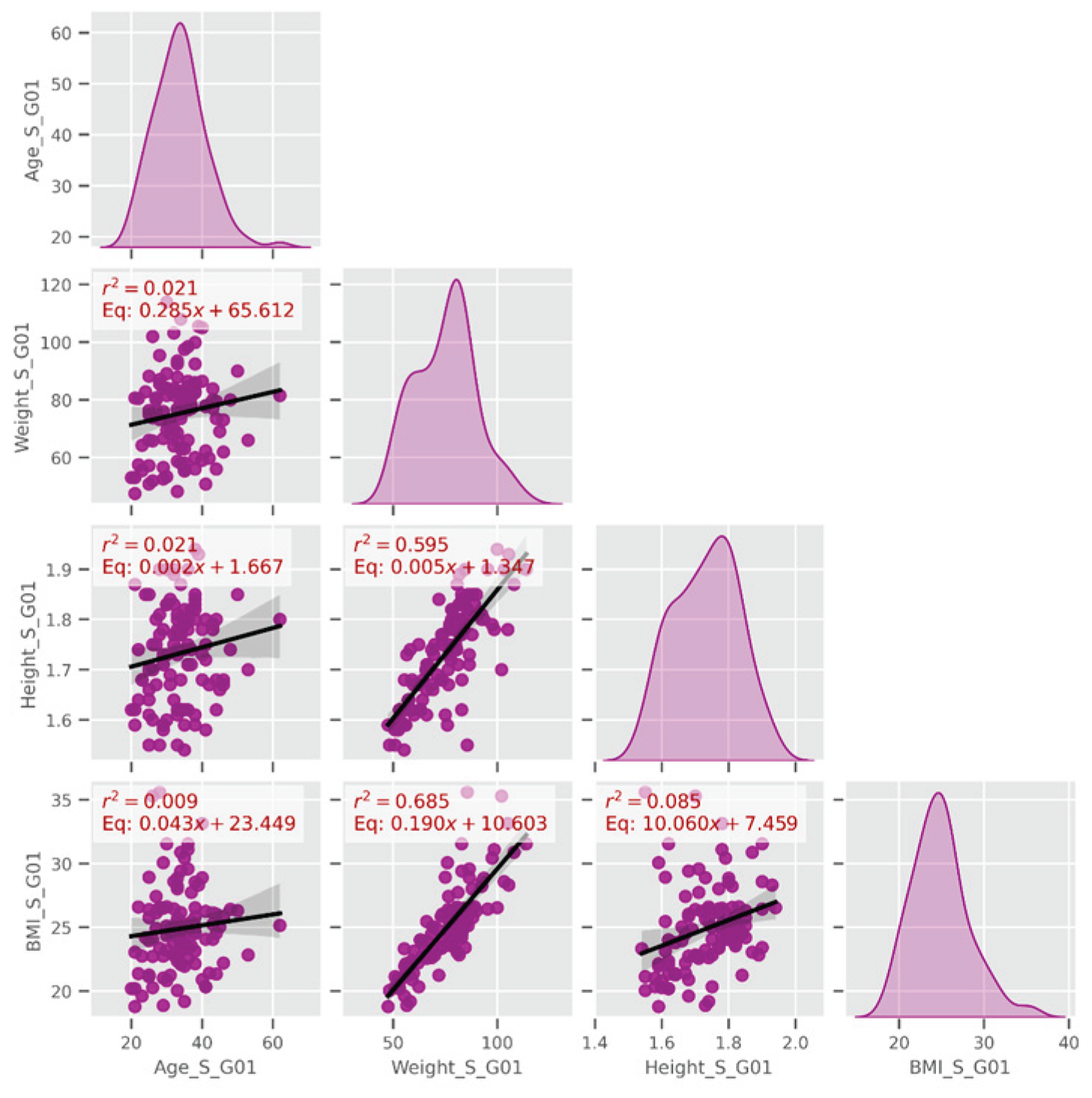

3.4. Understanding the Interactions of the Epidemiological Characteristics and the Functional Tests

Ordinary least square (OLS) linear models were constructed to examine all possible combinations of continuous variables within each coding group. In

Figure 8, a strong correlation was demonstrated between height and weight, which may indicate that a lean body type favors CF participation. Additionally, the low R

2 values for the weight-age pair suggest that CF athletes maintain stable body weight over time, which is expected according to the high energy demands and the whole-body muscular development. Another demographic characteristic given by the positive linear correlation between months of experience and weekly training hours, proposes that more experienced athletes continue to enjoy and engage in training over extended periods.

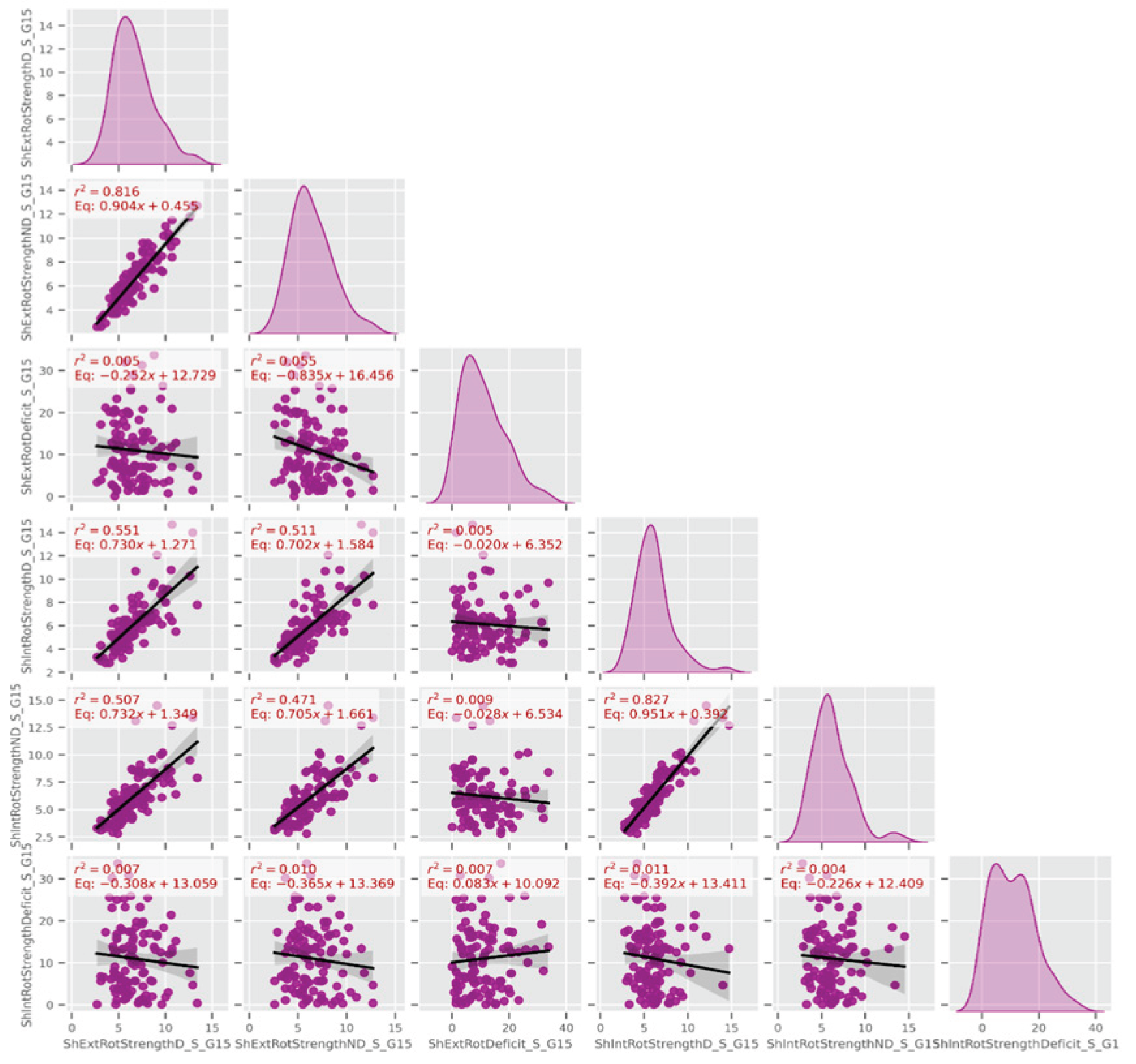

In

Figure 9, the two parameter pairs of dominant and non-dominant shoulder external rotators strength as well as their deficit, exhibited very high R

2 values. This finding strongly indicates that CF athletes engage in symmetrical training for these particular muscle groups, suggesting that symmetrical strength is an essential requirement for this sport. Moreover, this idea of bilateral mechanics is reinforced by an R

2 value of 0.4 between core rotation ROM toward the side of the dominant and non-dominant upper limb.

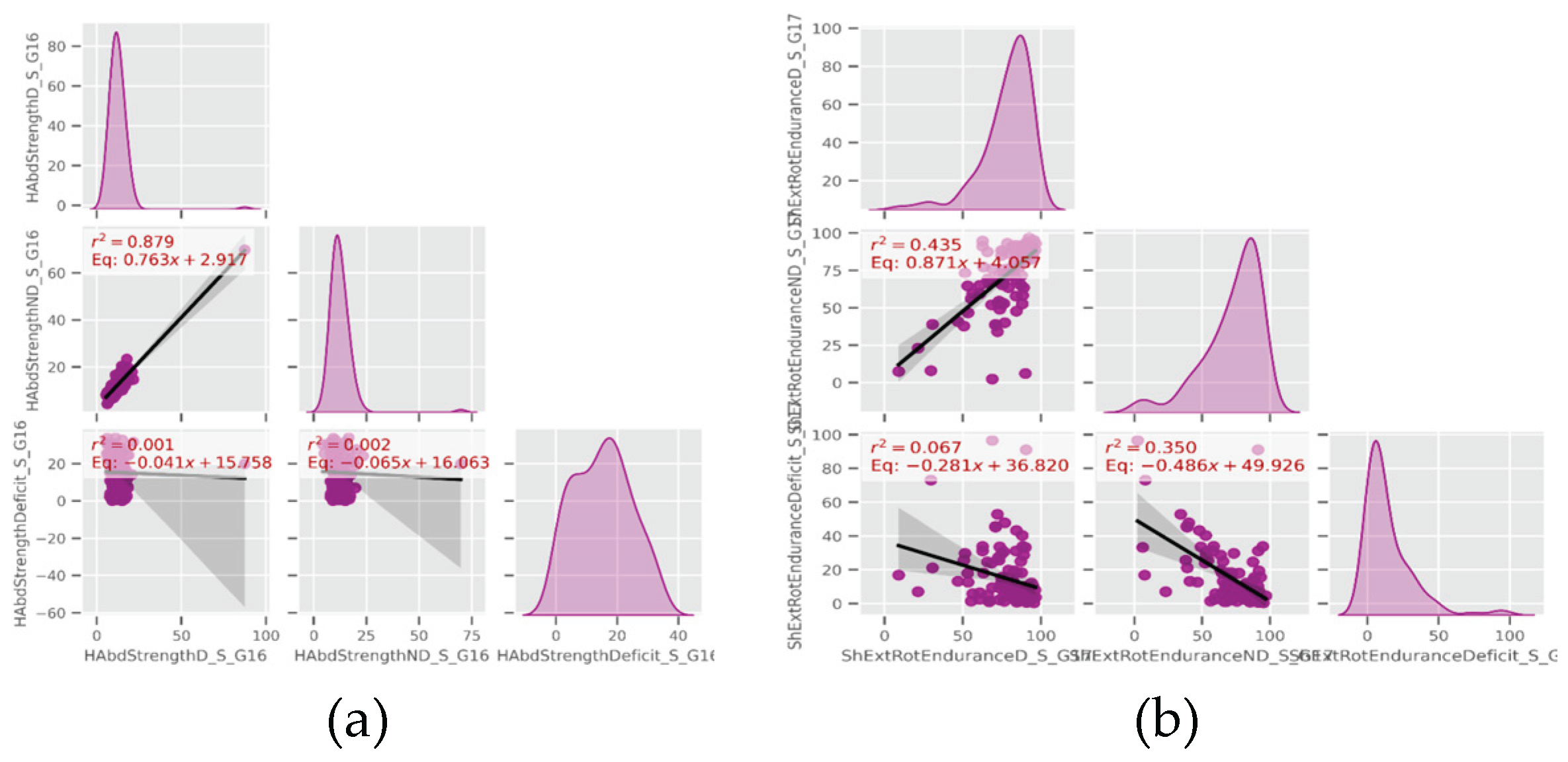

Analogous linear correlations regarding symmetry in isometric external rotators’ strength endurance and hip abductors strength are supported by the relatively high R

2 values observed in

Figure 10. This finding is a logical consequence of the nature of CF, as the sport incorporates exercises from various high-intensity interval training sports, promoting balanced muscular development.

3.5. Modeling and Predicting Shoulder Injuries

Models of the CF athletes’ injuries that utilize the continuous (i.e. scalar) variables of this study were created. Logistic regression models [

24] that combine the continuous variables (i.e. predictors) with the binary outcome of injury/no-injury (i.e. response variable) are presented. The model’s performance metric utilized the Area Under the Curve (AUC) of the Receiver Operating Characteristic (ROC) curve, which quantifies the overall ability of a binary classifier to discriminate between the two classes across all possible classification thresholds [

24]. An AUC value of 1.0 indicates perfect classification, while a value of 0.5 suggests no discriminative ability, equivalent to random guessing. Higher AUC values reflect better model performance. The ROC curve plots the true positive rate (TPR or sensitivity: measures how well a model identifies actual positive cases, and quantifies, how many the model correctly caught out of all the real positives/injuries) against the false positive rate (FPR or specificity: measures how often a model incorrectly labels negative cases as positive, and quantifies, how many the model mistakenly flagged as positive out of all the real negatives/no-injuries), showing the trade-off between sensitivity and specificity. AUC is widely used because it is independent of class distribution and provides a single, interpretable measure.

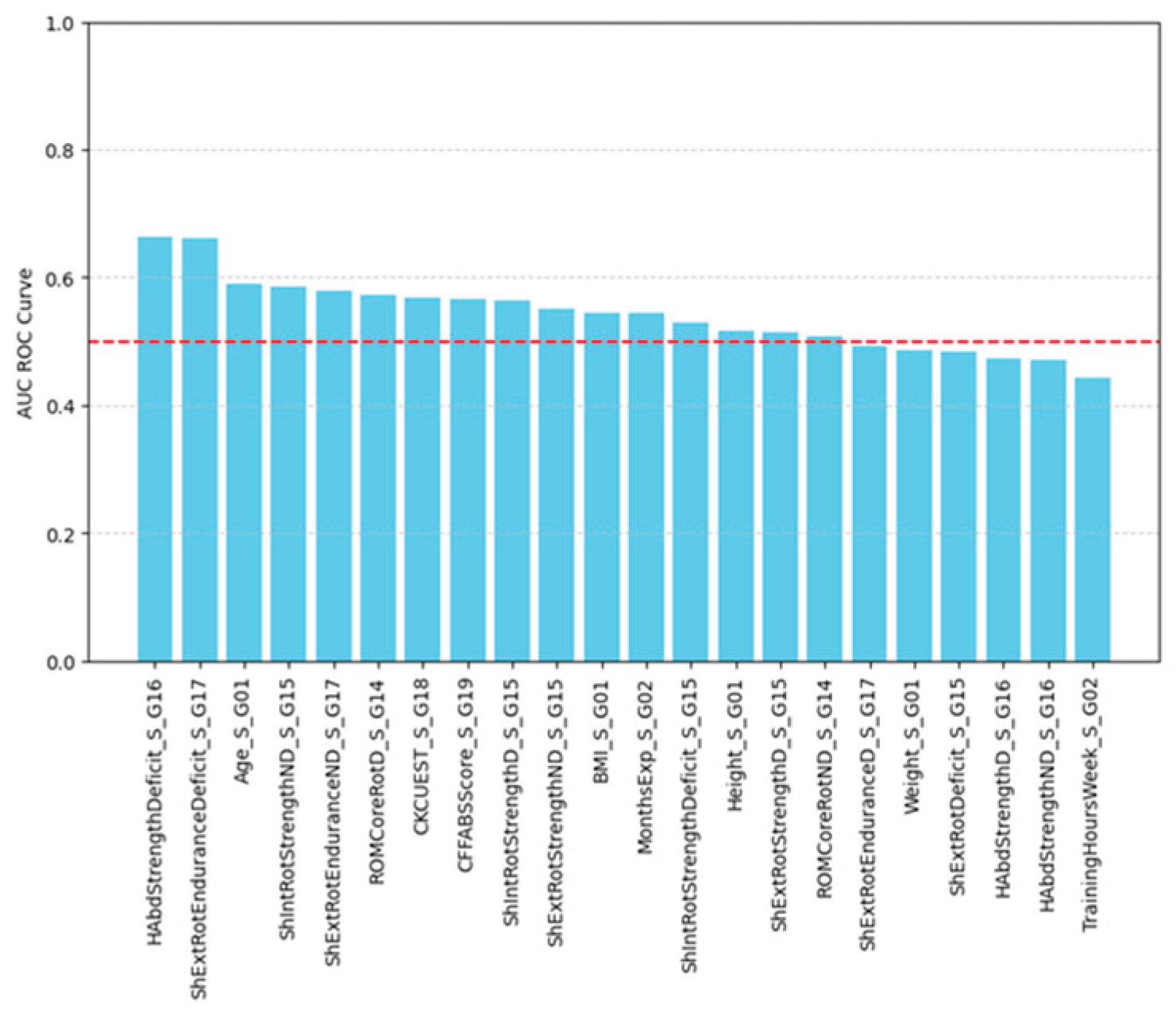

In

Figure 11, the AUC performance of the logistic regression models is presented, computed for all continuous variables analyzed in this study. As expected, given the large p-values from the corresponding t-tests and the substantial overlap of the probability density functions, the model performance is generally low. This provides strong evidence that individual variables possess limited or negligible predictive capability for shoulder injuries.

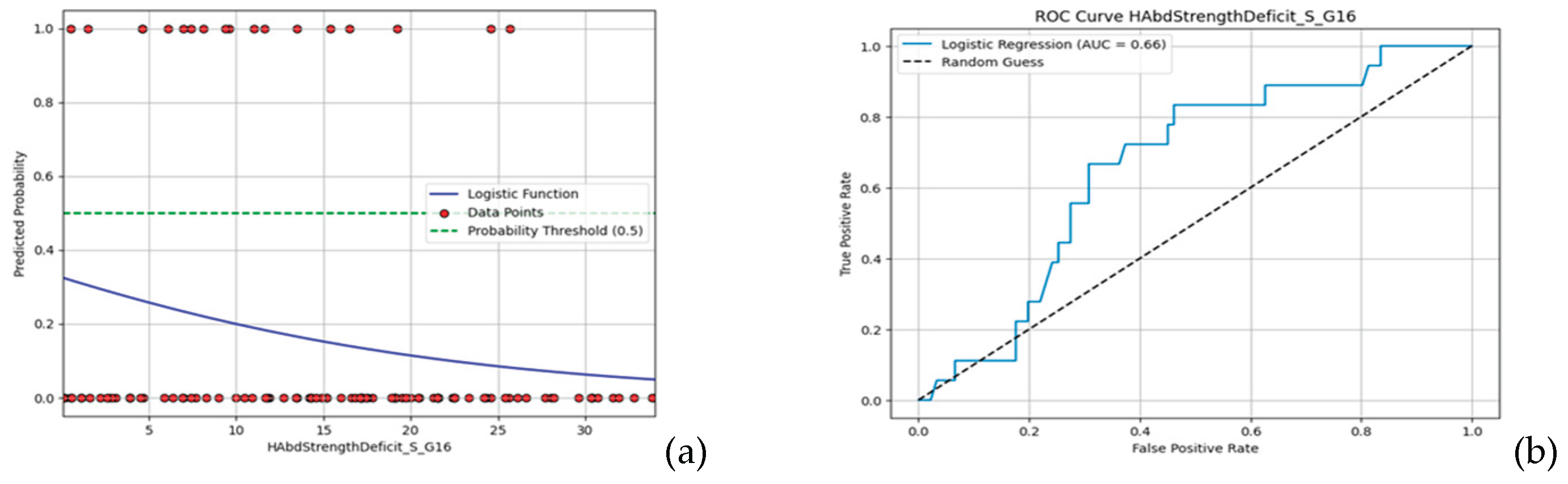

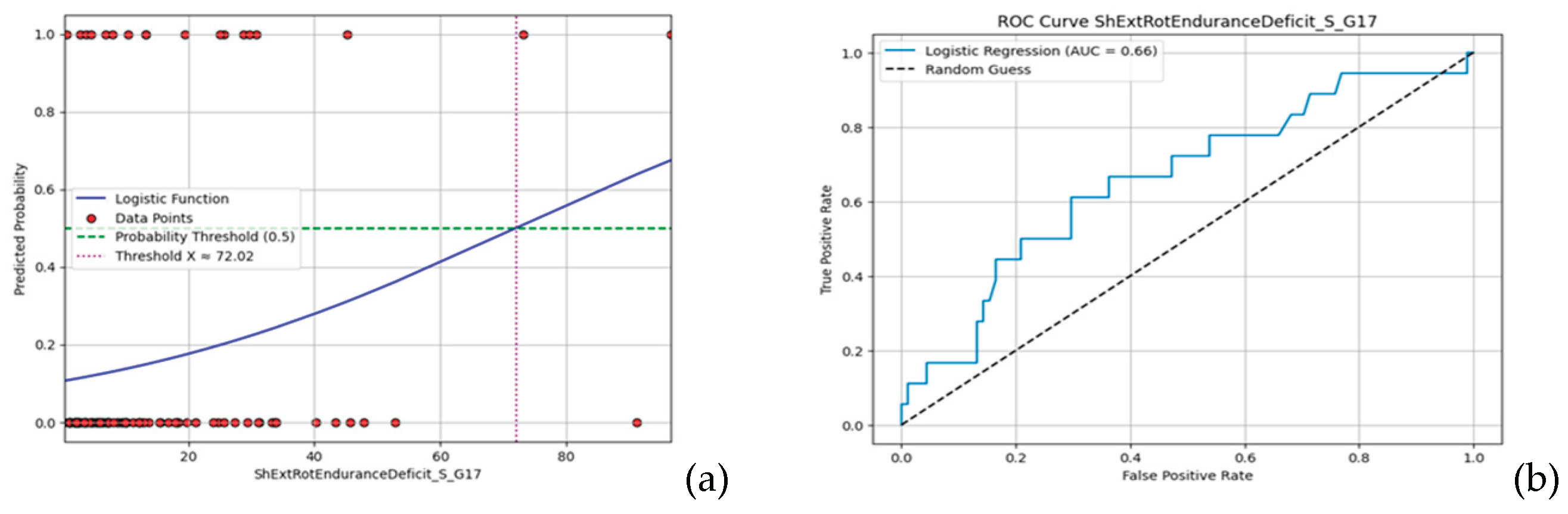

Focusing on the moderate performance models, with AUC values around 0.66, hip abduction strength deficit and shoulder external rotation endurance deficit are presented in

Figure 12 and

Figure 13. Higher values of shoulder external rotation endurance deficit appear to favor injury occurrence (i.e. >70) with a steady gaining ROC curve for the whole range of the values (with respect to random choice). On the other hand, the ROC curve of hip abduction strength deficit appears to be problematic at lower values (i.e. < 0.2), indicating that the model fails to accurately capture this range. Therefore, despite its moderate AUC value (i.e., 0.66), it does not provide significant insights into the shoulder injury mechanism.

4. Discussion

Numerous epidemiological investigations have examined CF injuries in recent years, revealing a significant prevalence of shoulder injuries. To the fullest extent of the researchers’ knowledge in the current study, this represents the inaugural prospective investigation into the demographic, epidemiological, and functional characteristics of shoulder injuries among CF athletes. The observed IIR for shoulder injuries was calculated to be 0.79 per 1,000 training hours, which is considerably lower than the results of prior, isolated retrospective epidemiological research on shoulder injuries that documented an IIR of 1.18 [

27]. The results of the present study resembled another retrospective investigation that solicited participants to recount their injuries that transpired within the previous six months, ultimately counting an IIR of 0.51 for shoulder injuries [

28]. It was observed high variability in injury report among previous retrospective studies, nonetheless. This disparity may be attributed to the self-reported nature of data collection in previous studies, which relied on participants’ evocation of their past injury experiences, contrary to current study which used prospective methodology. In order to enhance the precision of the results, participants were tracked by researchers during a year of training and competitions, with the objective of documenting any shoulder injuries that occurred during this period, including the nature, severity, and impact on the athlete’s participation in CF.

An additional innovative aspect of the present research was the implementation of the CF FABS, a sport-specific assessment tool utilized to evaluate the functional capabilities of CF athletes. The only prior assessment tool employed for the CF athlete population was the Functional Movement Screen (FMS) [

29]. However, this is a widely used tool for assessment of functionality, while CF FABS is specific for the sport. The aggregate scores obtained from both assessment tools did not reveal statistically significant correlations with the incidence of shoulder injuries. CrossFitters exhibited remarkably higher symmetry on the FMS in comparison to other athletic populations, particularly in the shoulder mobility test [

30]. The present study’s results corroborated those suggestions by demonstrating notable symmetry in ROM, strength, and endurance measured parameters.

CF has been characterized as a strenuous sport, pushing participants to engage at the upper limit of their physical capacities [

31]. The toughness of the sport additional to the sample’s average time of attendance, which was approximately three years, may indicate that athletes were used to participating under hard circumstances. It appears that a substantial pain tolerance has been evidenced, indicated by the finding that nearly 40% of our sample were practicing regularly despite experiencing pain in their shoulder. This element may serve as a contributory factor to the observed low incidence rate of shoulder injuries.

As a new injury was delineated, any sensation of pain or discomfort resulting in the cessation or alteration of the training regime for one day or more was noted. The criteria for defining a newly reported injury were consistent with established definitions in the literature [

27,

29]. Prior prospective investigations on the incidence of CF injuries and their corresponding risk factors tracked their cohorts for durations of either 8 weeks [

32] or 12 weeks [

19,

29], which were considerably shorter time frames than the 12-months period of the current study.

Previous research has indicated that age and sex represent significant non-modifiable factors correlated with the incidence of injuries, with older individuals and male participants demonstrating a heightened susceptibility to such injuries [

5,

6]. Moreover, an elevated BMI has been associated with higher risk for injury, alongside a prior history of injuries, which predisposes individuals to a greater likelihood of sustaining subsequent injuries, particularly in the same anatomical region [

6]. A discrepancy was observed among studies regarding competitiveness. One particular study found a higher injury incidence among competitive individuals [

28], a different one reported a 2.64-fold greater probability for injury in non-competitors [

33], while another study showed no statistically significant differences between the groups [

34]. One possible explanation for these contradictory results, apart from the diverse methodological approaches of the studies, is the fact that competitive athletes are usually exposed to a higher load by pushing their limits further, which may be counteracted by them being more physically aware and technically efficient. Concerning male gender, older age, and prior injury history, a contemporary systematic review on the vulnerability to musculoskeletal injuries among CF participants resulted in incongruent evidence [

35]. This is in line with the current study, which demonstrated no statistically significant association of any of those variables with the incidence of shoulder injuries.

RC injuries constituted the predominant tissue involvement among the shoulder injuries that occurred, manifesting either in isolation or in conjunction with other shoulder injuries. This result was in accordance with the outcomes of a magnetic resonance imaging study which indicated elevated percentages of partial lesions in the supraspinatus and subscapularis tendons within a sample of CF participants evaluated [

9]. In terms of exercises associated with an increased risk of shoulder injury, a recent systematic review identified several gymnastics exercises, namely ring dips, ring muscle-ups, and kipping movements, as significantly prevalent [

7]. On the contrary, the present study recognized Olympic weightlifting exercises as the most strongly related to shoulder injuries, followed by gymnastics activities. Similarly, Summitt et al. reported that overhead press and snatch variations were the ones most frequently leading to shoulder injuries, ahead of the gymnastics exercises [

27]. In summary, both types of exercises that load the shoulder in an overhead position predispose athletes to overuse tendinopathies as well as partial or complete thickness tears [

14].

Nevertheless, the comparisons drawn between the present study and prior retrospective or prospective studies with a short observation period must be critically scrutinized. Athletes with extensive experience in CF may exhibit a higher incidence of injuries compared to those who are relatively new to the sport, reflecting chronically accumulated microtrauma. The fact that the majority of the findings come from retrospective studies based on electronic questionnaires, inherently subject to bias, weakens the existing evidence on the topic of CF injuries. Furthermore, the preponderance of the studies focuses on all forms of CF injuries, whereas the present study exclusively examined shoulder injuries. Consequently, the validity of comparisons may be debatable.

The principal objective of this investigation was to discern potential variables that may correlate with shoulder injuries among CF athletes. To accomplish this, the study’s methods were meticulously crafted to gather a comprehensive array of measurements and data. This extensive data framework affords the opportunity for an in-depth analysis intended to elucidate highly correlated variables, which may facilitate the exclusion of certain factors in subsequent research and reveal novel interactions that could enhance athletic training practices. Nevertheless, one plausible interpretation of the aforementioned statistical findings is that no single parameter in isolation, regardless being a demographic characteristic, an epidemiological variable, or a functional assessment, proved adequate to establish a link with shoulder injuries. Further inquiry may elucidate the interrelationships among variables that could contribute to the prevalence of shoulder injuries.

The principal strength of the current investigation lies in the 12-month prospective nature of the observational period, involving a cohort of 109 CF athletes. The methodological approach encompassed direct baseline assessment of the athletes and a second assessment upon the occurrence of new injuries. The classification of the documented shoulder injuries was undertaken by a single examiner, the principal investigator who is a senior physiotherapist. A comprehensive array of measurements was collected to guarantee that all pertinent dimensions of the subject matter were thoroughly examined. Nevertheless, potential limitations were recognized. The extended duration of the study, in addition to the spread of the sample over four different cities, rendered it challenging to ensure compliance within the cohort. It is possible that some injuries went unreported to the investigators, notwithstanding the frequent updates provided to the sample. The number of the 20 new shoulder injuries might appear low, however, prospective monitoring of a greater sample of CF athletes is very challenging. Additionally, the possibility that baseline values might change throughout the 12-month monitoring period, introduces a degree of uncertainty to the investigation of their connection to new injuries, but this is a standard flaw of all relevant studies that use baseline tests. Repeated testing throughout the season could ameliorate this limitation.

Author Contributions

Conceptualization, A.B.; Methodology, A.B., G.T., K.F., S.A.X., and E.T.; Validation, A.B., E.T., and G.T.; Investigation, A.B.; Writing—original draft preparation, A.B.; Writing—review and editing, E.T., G.T., C.M., K.F., and S.A.X.; Supervision, E.T., G.T., and C.M. All authors have read and agreed to the published version of the manuscript.

Figure 1.

Descriptive statistics and PDFs of male and female athletes (a) regarding (b) age, (c) BMI, (d) training volume, and (e) CF experience.

Figure 1.

Descriptive statistics and PDFs of male and female athletes (a) regarding (b) age, (c) BMI, (d) training volume, and (e) CF experience.

Figure 2.

PDFs of competitive and non-competitive athletes regarding (a) experience and (b) training volume.

Figure 2.

PDFs of competitive and non-competitive athletes regarding (a) experience and (b) training volume.

Figure 3.

(a) Sample’s percentage of injured and non-injured athletes and (b) an indicative example of overlapping in PDF of injured and non-injured athletes regarding CF experience.

Figure 3.

(a) Sample’s percentage of injured and non-injured athletes and (b) an indicative example of overlapping in PDF of injured and non-injured athletes regarding CF experience.

Figure 4.

PDFs of injured and non-injured athletes regarding (a) core rotation towards NDUE’s side, and (b) CF FABS total score.

Figure 4.

PDFs of injured and non-injured athletes regarding (a) core rotation towards NDUE’s side, and (b) CF FABS total score.

Figure 5.

Injured versus non-injured athletes regarding ordinal data of (a) warm up, (b) recovery, and (c) Sots press test.

Figure 5.

Injured versus non-injured athletes regarding ordinal data of (a) warm up, (b) recovery, and (c) Sots press test.

Figure 7.

Examples of visual verification of binary data intermixture. Injured versus non-injured athletes regarding (a) shoulder pain during CF, (b) symmetry of flexion ROM, (c) external rotation, and (d) internal rotation ROM between shoulders.

Figure 7.

Examples of visual verification of binary data intermixture. Injured versus non-injured athletes regarding (a) shoulder pain during CF, (b) symmetry of flexion ROM, (c) external rotation, and (d) internal rotation ROM between shoulders.

Figure 8.

Linear models among age and weight, height, and BMI (Data group 1).

Figure 8.

Linear models among age and weight, height, and BMI (Data group 1).

Figure 9.

Linear models among dominant and non-dominant shoulder’s external and internal rotation strength. Continuous data of external and internal rotators strength and deficits (Data group 15).

Figure 9.

Linear models among dominant and non-dominant shoulder’s external and internal rotation strength. Continuous data of external and internal rotators strength and deficits (Data group 15).

Figure 10.

Linear models among (a) hip abductors strength measurements and (b) shoulder external rotators endurance measurements (Data group 16 and 17 respectively).

Figure 10.

Linear models among (a) hip abductors strength measurements and (b) shoulder external rotators endurance measurements (Data group 16 and 17 respectively).

Figure 11.

AUC performance of the logistic regression for all the continuous variables.

Figure 11.

AUC performance of the logistic regression for all the continuous variables.

Figure 12.

(a) Logistic regression model and (b) ROC curve for hip abduction strength deficit.

Figure 12.

(a) Logistic regression model and (b) ROC curve for hip abduction strength deficit.

Figure 13.

(a) Logistic regression model and (b) ROC curve for shoulder external rotation endurance deficit.

Figure 13.

(a) Logistic regression model and (b) ROC curve for shoulder external rotation endurance deficit.

Table 1.

Descriptive statistics for baseline measurements.

Table 1.

Descriptive statistics for baseline measurements.

| Variable |

Mean |

Std. Deviation |

Std. Error Mean |

Range |

| Age (years) |

33.73 |

7.31 |

.70 |

20 – 62 |

| Weight (kg) |

75.24 |

14.57 |

1.40 |

47.50 - 113.90 |

| Height (meters) |

1.73 |

0.10 |

.01 |

1.54 - 1.94 |

| BMI (kg/m2) |

24.89 |

3.34 |

.32 |

18.79 - 35.59 |

| Experience (months) |

34.10 |

29.16 |

2.79 |

1 - 120 |

| Training Volume (hours/week) |

4.48 |

2.36 |

.23 |

1 - 18 |

| ROM Core Rotation D* (degrees) |

73.32 |

14.07 |

1.35 |

40 - 105 |

| ROM Core Rotation ND** (degrees) |

77.92 |

13.87 |

1.33 |

40 - 125 |

| Shoulder External Rotation Strength D (kg) |

6.66 |

2.16 |

.21 |

2.70 - 13.40 |

| Shoulder External Rotation Strength ND (kg) |

6.48 |

2.16 |

.21 |

2.60 - 12.70 |

| Shoulder External Rotation Strength Deficit (side-to-side difference %) |

11.05 |

7.67 |

.74 |

0.10 - 33.70 |

| Shoulder Internal Rotation Strength D (kg) |

6.13 |

2.12 |

.20 |

2.80 - 14.70 |

| Shoulder Internal Rotation Strength ND (kg) |

6.22 |

2.22 |

.21 |

2.80 - 14.50 |

| Shoulder Internal Rotation Strength Deficit (side-to-side difference %) |

11.01 |

7.80 |

.75 |

0.10 - 33.70 |

| Hip Abduction Strength D (kg) |

12.77 |

7.99 |

.77 |

5.60 - 87.30 |

| Hip Abduction Strength ND (kg) |

12.66 |

6.50 |

.62 |

4.30 - 69.80 |

| Hip Abduction Strength Deficit (side-to-side difference %) |

15.24 |

9.25 |

.89 |

0.10 - 34 |

| Shoulder External Rotation Endurance D (%) |

78.37 |

15.98 |

1.53 |

9.10 - 96.50 |

| Shoulder External Rotation Endurance ND (%) |

72.31 |

21.11 |

2.02 |

2.40 - 96.90 |

| Shoulder External Rotation Endurance Deficit (side-to-side difference %) |

14.77 |

17.35 |

1.66 |

0.40 - 96.60 |

| CKCUEST Score (non-dimensional) |

24.39 |

5.27 |

.51 |

13 - 37 |

| CF FABS Score (non-dimensional) |

11.61 |

5.16 |

.49 |

0 - 22 |

Table 2.

Descriptive statistics of the new referred shoulder injuries’ scale data.

Table 2.

Descriptive statistics of the new referred shoulder injuries’ scale data.

| Variable |

Mean |

Std. Deviation |

Std. Error Mean |

Range |

| VAS Pain Score |

5.15 |

1.69 |

.38 |

3.0 - 9.0 |

| SDQ Score (%) |

38.13 |

16.83 |

3.76 |

12.50 - 87.50 |

| Days Out |

13.75 |

28.04 |

6.27 |

0 - 108 |

Table 3.

Comparisons between the continuous data of the functional measurements.

Table 3.

Comparisons between the continuous data of the functional measurements.

| Variable |

t-statistic |

p-value |

| ROM Core Rotation D (degrees) |

-0.8749 |

0.384 |

| ROM Core Rotation ND (degrees) |

-0.1206 |

0.904 |

| Shoulder External Rotation Strength D (kilograms) |

0.4344 |

0.665 |

| Shoulder External Rotation Strength ND (kilograms) |

0.8175 |

0.416 |

| Shoulder External Rotation Strength Deficit (side-to-side difference %) |

-0.2284 |

0.820 |

| Shoulder Internal Rotation Strength D (kilograms) |

1.8113 |

0.073 |

| Shoulder Internal Rotation Strength ND (kilograms) |

1.4597 |

0.147 |

| Shoulder Internal Rotation Strength Deficit (side-to-side difference %) |

-0.3061 |

0.760 |

| Hip Abduction Strength D (kilograms) |

-0.2777 |

0.782 |

| Hip Abduction Strength ND (kilograms) |

-0.2952 |

0.768 |

| Hip Abduction Strength Deficit (side-to-side difference %) |

-2.2162 |

0.029* |

| Shoulder External Rotation Endurance D (%) |

-0.2963 |

0.768 |

| Shoulder External Rotation Endurance ND (%) |

-1.6982 |

0.092 |

| Shoulder External Rotation Endurance Deficit (side-to-side difference %) |

2.6192 |

0.010* |

| CKCUEST (nd) |

-0.7786 |

0.438 |

| CF FABS Score (nd) |

1.0984 |

0.275 |

Table 4.

Comparisons between the ordinal epidemiological data and sport-specific testing measurements.

Table 4.

Comparisons between the ordinal epidemiological data and sport-specific testing measurements.

| |

Variable |

t-statistic |

p-value |

| Epidemiological characteristics |

Adequate Warm Up |

611.0 |

0.029** |

| Adequate Recovery |

850.5 |

0.784 |

| Prior Fitness Level |

903.5 |

0.464 |

| DUE* Injured Areas |

663.5 |

0.153 |

| NDUE* Extremity Injured Areas |

636.0 |

0.082 |

| DLE* Injured Areas |

776.5 |

0.691 |

| NDLE* Injured Areas |

742.0 |

0.442 |

| Core Injured Areas |

663.5 |

0.153 |

| All Injured Areas |

509.5 |

0.0097** |

| CF FABS individual tests |

Squat |

695.5 |

0.289 |

| Shoulder Rotation D |

825.0 |

0.962 |

| Shoulder Rotation ND |

680.5 |

0.243 |

| Wall Angel |

932.0 |

0.326 |

| OHS |

688.0 |

0.262 |

| Windmill D |

812.0 |

0.956 |

| Windmill ND |

651.0 |

0.152 |

| Sots Press |

684.0 |

0.241 |