1. Introduction

Sport disciplines are often classified into symmetrical and asymmetrical: the symmetrical disciplines include activities such as gymnastics and running, and the asymmetrical disciplines include sports such as tennis, fencing and javelin throwing. However, this classification is not universally defined, as the distinction between these two categories remains somewhat ambiguous and lacks a standardized framework [

1].

In asymmetric sport, athletes tend to develop disproportionate hypertrophy and strength in the dominant side [

2,

3,

4]. While these adaptations are functional for the sport, they may also increase the risk of injury and affect overall biomechanics if not properly managed. In contrast, symmetric sports tend to promote a more balanced development of body musculature [

5]. However, factors such as individual technique and specific movement patterns can influence the onset of musculature imbalances, even in these disciplines. In symmetric sports, such as swimming, cycling, or athletics, particularly in disciplines like marathon running or track events, the mechanical load during the movement execution promotes a more harmonious and bilateral muscle development, as a both sides of the body undergo similar physical demands throughout the activity. From a biomechanical perspective, this results in bilateral muscle recruitment and activation during the execution of the sport-specific movement, minimizing the occurrence of significant muscular imbalances between the limbs [

6].

Asymmetrical sports, like tennis, are characterized by repetitive movements, such as serves and groundstrokes, which impose greater biomechanical demands on the dominant upper limb [

7]. These actions can lead to imbalances in muscle development and joint function, resulting in intensive and asymmetric use of the muscles and joints involved in ball striking. This asymmetry may contribute to structural and functional adaptations that affect the overall biomechanics of the sport. Can demonstrate altered glenohumeral joint mobility and flexibility in the dominant arm resulting in significantly less internal rotation (IR) and greater external rotation (ER) of the shoulder, classifies as glenohumeral internal rotation deficit (GIRD) [

8]. Spinal injuries in athletes who perform overhead actions are often due to overuse by repetitive mechanisms and muscle fatigue. They may be related to scapular dyskinesia, rotator cuff weakness or glenohumeral internal rotation deficit [

9]. These asymmetries can significantly influence the athlete

’s performance and increase the risk of injury [

10].

Asymmetries in the musculature of the upper limbs are common in sports that predominantly rely on unilateral upper limb activity, where the muscles of the dominant limb are usually more developed than those of the non-dominant limb. This phenomenon translates into differences in strength, flexibility and internal and external rotational capacity at the shoulder. Studies have shown that tennis players with a greater imbalance in the strength and mobility of the internal and external rotators of the shoulder are more likely to develop injuries such as tendonitis, rotator cuff tears and impingement syndrome [

11]. In addition, asymmetries can affect trunk stability and force transfer between the upper and lower extremities, which is critical for explosive and powerful movements. Inefficient force transfer can lead to suboptimal performance and increased wear and tear on joints [

12]. Tennis performance is closely related to the athlete

’s ability to generate and control force during movements. Asymmetries can limit this ability, affecting technique and efficiency of stroke execution. For example, tennis players with a greater degree of muscular asymmetry often experience a decrease in the consistency and accuracy of their strokes, which can negatively influence competitive results [

11].

The repetitive asymmetric action uses to cause an important asymmetry in the upper limbs that use to provoke most of the common pathologies in the shoulder complex of the tennis players. Professional tennis players have a very risk of musculoskeletal injuries, due to a high volume of play and the great physical demands of sport. Injury rates range from 0,05 to 2,9 injuries for player in a year, with a higher frequency of injuries as the time on the court increases [

13] Shoulder injuries represent a significant concern among athletes, particularly in sports that place repetitive or high-load demands on the shoulder complex. For instance, in baseball, it is estimated that between 12% and 19% of all reported injuries occur at the shoulder, highlighting the vulnerability of this joint in overhead throwing activities. Similarly, in swimming, where athletes engage in continuous, high-repetition shoulder motions, the prevalence of shoulder injuries is notably higher, ranging from 23% to 38% within a single competitive year [

14].

In the case of many unilateral sports that involve the upper limbs, the glenohumeral joint is often in an protraction position, a phenomenon also observed in many athletes who perform overhead movements. This position alters the center of gravity of the shoulder girdle and causes changes in joint dynamics, affecting the efficiency of the muscles involved. A predominance of the internal rotator muscles, such as the subscapularis, pectoralis major, latissimus dorsi and anterior deltoid, compared to the external rotators has been documented, which may contribute to a functional imbalance [

15]. The subscapularis muscle, crucial for stabilization of the glenohumeral joint, can become a destabilizer when in elevated positions, accentuating the protraction of the shoulder girdle [

16]. In addition, the biceps brachii, with fibers in different orientations, may be adversely affected, especially in overhead positions, which could increase the risk of injuries such as labral tears. The only external rotators we have are the infraspinatus, supraspinatus, teres minor and the posterior deltoid [

17], the posterior deltoid of the external rotator muscles is the largest and has the most muscle fibers.

The major upward rotators of the scapula are the upper and lower fibers of them trapezius and the lower digitations of the serratus anterior [

18]. The rotator cuff allows us to have greater functionality of the shoulder during the execution of specific tennis movements [

19]. In addition, during these movements the rotator cuff and scapulothoracic muscles will be a dynamic stabilizer and the Middle and Lower trapezius contribute to proper scapular mobility and stability, facilitating coordinated movement with the humerus [

20], because these muscles are very close to the joint and generate compressive forces. For instance, during flexion and extension movements, anteroposterior translations of the humeral head are restricted by rotator cuff muscles that are activated in a direction-specific manner to ensure joint stability [

21]. For this reason, it will be essential to maintain good stability and mobility of the glenohumeral joint. Understanding the tennis-specific adaptations of the shoulder complex could help tennis players, coaches, athletic trainers, and clinicians to design and utilize optimal exercise protocols [

10].

Surface electromyography (sEMG) is a non-invasive technique that quantifies the electrical activity of skeletal muscles through electrodes placed on the skin

’s surface. This method captures neurophysiological variations, specifically motor unit action potentials generated during muscle fibres contractions. The resultant sEMG signal represents the summation of individual motor unit action potentials within the detection area, providing a comprehensive view of neuromuscular activation. Such signals allow for detailed analysis of muscle behaviour under various conditions, including resting states, dynamic or isometric contractions, and specific experimental tasks. Consequently, sEMG has become an essential tool in fields such as biomechanics, rehabilitation, ergonomics, and sports science.[

22]

Previous research reported the activation patterns of superficial scapular muscles using surface EMG [

23]. Surface electromyography EMG allows you to measure the electrical activity of muscles in real time during all the movements you scan with your patient. EMG has been used in clinic to check the nerve muscle and nerve conduction functions. Surface electromyography can be performed by placing non-invasive electrodes on the skin’s surface to record underneath muscle activities [

24]. To know if the exercises used activate the intrascapular muscles, so we will know how effective they are. The neurally mediated control of muscle activation has the capacity to adapt joint mechanics in response to different limb configurations and loading conditions. Also, indicate that a failure of this adaptive mechanism is associated with the incidence of glenohumeral instability [

25]. Consequently, the investigation of atypical shoulder muscle function during the exercise’s performance, it will be important to be able to see the correct activation of the muscles that we want to work. Electromyographic investigations of glenohumeral instability have quantified the level of muscle recruitment by comparing the amplitude of activation at different stages of the movement cycle. While recruitment level is an important characteristic of muscle function, an equally important factor is the timing of the activation during the prevention exercise’s performance [

25]. To our knowledge, a detailed analysis of the temporal characteristics of shoulder muscle activation during the prevention exercise’s performance. In previous electromyographic study that they wanted to determine the effect of fatigue including exercise on the muscle recruitment pattern of the same muscles, their conclusion was the muscle onset times in all muscles, but the lower trapezius was delayed after fatigue, suggesting that muscle recruitment of the middle deltoid and upper and middle trapezius may be influenced by fatigue [

18] . The preventive exercise is novel in the field of corrective exercises designed to correct musculoskeletal disorders and to prevent secondary complications such as pain and injury.

The RMS (Root Mean Square) line graph is a commonly used representation of muscle activity captured during an evaluation. The vertical axis quantifies the magnitude of muscle activation, while the horizontal axis illustrates the temporal progression of the test. This visualization enables both qualitative and quantitative analysis of muscle activity changes across repetitions of an exercise, providing essential information on neuromuscular performance and fatigue [

26]

Muscular asymmetry is defined as a disparity in activation levels exceeding 20% between homologous muscles on the left and right sides of the body. Such asymmetries are critical indicators of neuromuscular imbalances that may increase the risk of injury or impair functional performance.[

27] A muscle asymmetry occurs when the function between corresponding muscles on opposite sides of the body is greater than 20%. These inequalities can result from a variety of factors, including injury, unbalanced movement patterns, incorrect posture, or unequal load distribution during physical activities. The Muscle Symmetry Index is used to quantify how similar two muscles are in terms of muscle activity: asymmetry 0-79% similarity; limit 80%-89% similarity and normal or symmetrical: 90-100% [

28]

This parameter represents the proportional distribution of muscle activation across the evaluated muscles during a specific task or exercise. Analyzing this distribution provides insights into the functional role of each muscle, revealing deficits or excessive activation that could signify neuromuscular imbalances. Altered muscle activity distributions have been linked to compensatory movement patterns.

Muscle synergy refers to the coordination and collaboration of multiple muscles to perform a movement. In muscle synergy, muscles work together to generate movement, stabilise the body, or both. Indicates what level of involvement or muscle activity in % a muscle has had with respect to another. It will help us to compare contractile activity between muscles in a simple way and it is easy to quantify muscle over-activation or inhibition. This concept is fundamental in biomechanics and exercise physiology, as human movements are rarely the result of the action of a single muscle.[

29]

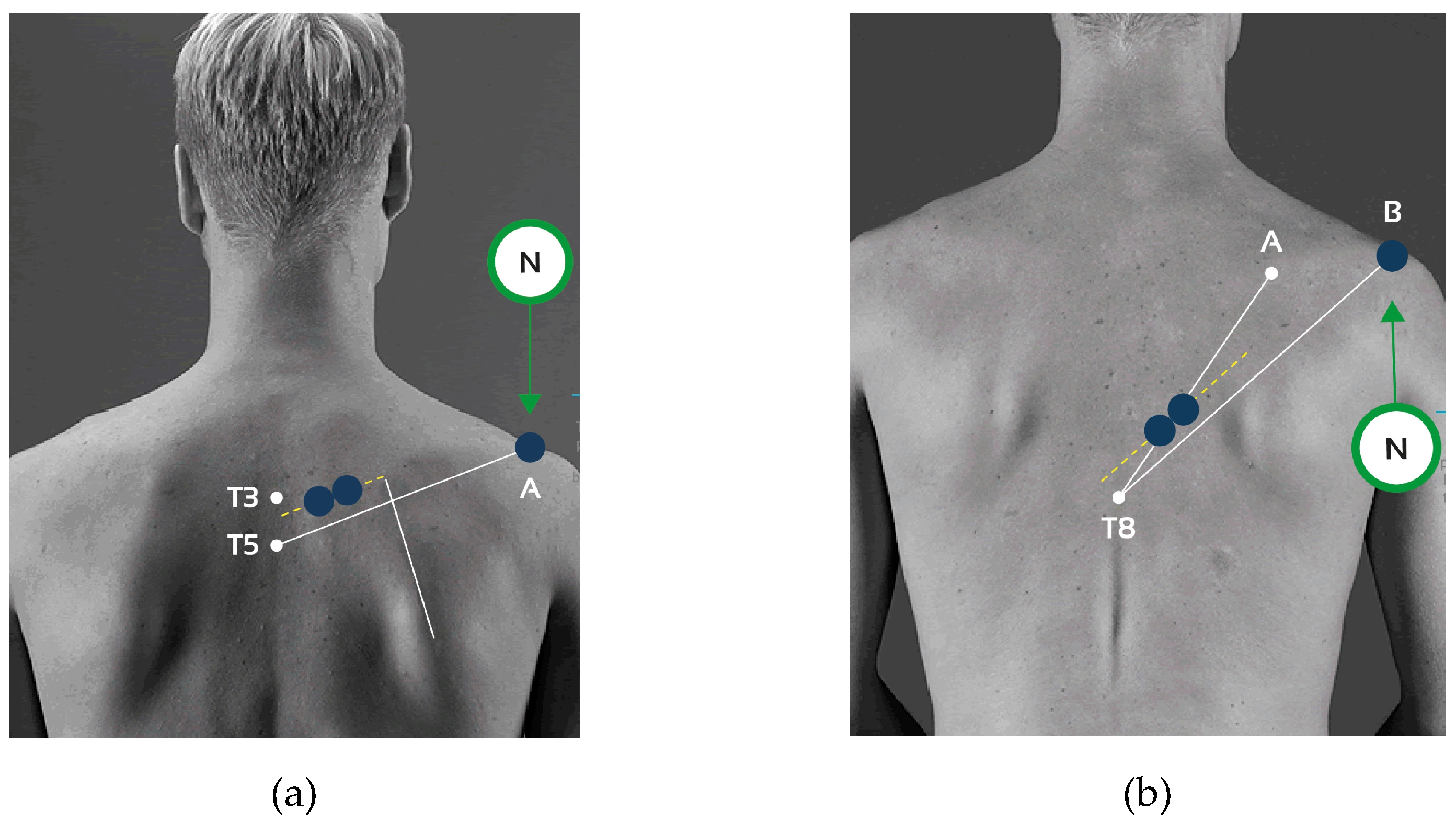

In recent studies, researchers have increasingly utilized microelectromechanical systems (MEMS) sensors affixed to the body to monitor motion patterns. These sensors demonstrate promising reliability when compared to the gold-standard three-dimensional optical motion capture systems traditionally employed in laboratory settings. Inertial measurement units (IMUs), a specific type of MEMS technology, are now being implemented to assess trunk and arm positions throughout the day. For example, they have been used to quantify the duration of awkward postures in healthcare workers such as nurses and agricultural workers like dairy farmers. These devices enable continuous data collection without requiring constant visual or video monitoring, providing a practical and efficient method for posture assessment in real-world environments [

30]

Several studies that have conducted preventive exercises with the Bands have shown that improved shoulder muscle activation, IR ROM, rotator cuff muscle strength ratio and GH joint position sense in participants with GIRD. The throwing exercise with the Band seems to affect the length of the muscles and tendons which could produce more force according to the length tension curve theory in a muscle and improve neuromuscular coordination in agonist and antagonist muscles. As a result, these changes may increase the strength of the shoulder muscles [

8]. A previous study has suggested that stretching techniques to glenohumeral articulation, internal rotation and to the posteroinferior glenohumeral tissues help the symptoms of patients with GIRD. While additional research has showed the effects of strengthening exercises on internal and external rotators on the dominant side and the effects of functional exercises on eccentric rotation strength during prevention and rehabilitation programs [

8,

31]. Contemporary clinical practice emphasizes the development and implementation of preventive strategies to reduce injury incidence and associated downtime. These proactive measures aim to optimize athletic performance by mitigating risk factors, thereby preserving physical function and minimizing the potential for long-term career impairment [

32].

To date, intermuscular coordination in asymmetric sports remains underexplored, despite its crucial role in shoulder function. Effective shoulder performance depends on the synchronized activation of multiple muscle groups, which is especially vital in sports characterized by repetitive unilateral movements, such as tennis [

6]. Existing training and prevention protocols—particularly those addressing conditions like glenohumeral internal rotation deficit (GIRD)—have primarily been developed for overhead athletes in sports like baseball, with limited adaptation for tennis. While lower limb asymmetries have been widely studied, especially in football and track and field, there is a paucity of research on upper limb asymmetries in the context of symmetric versus asymmetric sports. This gap is significant given the high unilateral demands placed on the shoulders in tennis, which can contribute to muscular imbalances and injury risk. This study aims to investigate upper limb muscle asymmetries between athletes involved in symmetric and asymmetric sports through bilateral shoulder injury prevention exercises. By analyzing muscle activation patterns in both dominant and non-dominant limbs, the study seeks to determine the efficacy of bilateral training in reducing asymmetries and informing injury prevention strategies for athletes in asymmetric sports. We hypothesized that Athletes engaged in asymmetric sports, such as tennis, will exhibit greater upper limb muscle activation asymmetries compared to athletes in symmetric sports.

4. Discussion

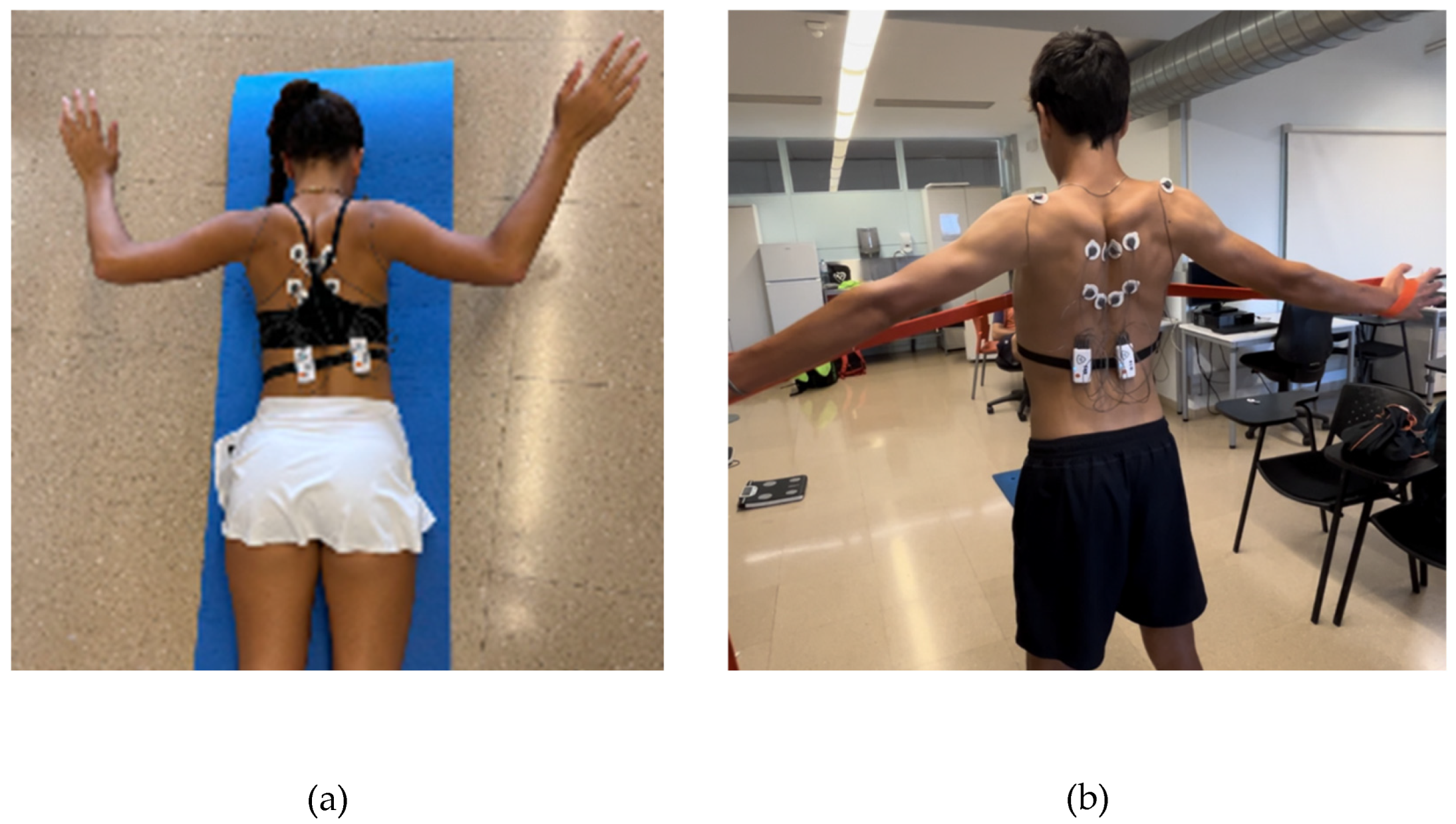

This study investigated shoulder muscle recruitment differences between tennis players (TP) and non-tennis players (N-TP) through electromyographic (EMG) analysis during tasks performed at 90° and 45° of shoulder abduction during two symmetrical exercises of scapular retraction, in prone position and Standing with a resistance band. The results revealed several statistically significant differences, suggesting that regular engagement in overhead sport such as tennis may lead to distinct neuromuscular adaptations in shoulder musculature across different shoulder positions and exercises.

To the very best of our knowledge, there is a lack of studies that specifically investigated activation patterns and asymmetries in unilateral sports such as tennis doing a preventive exercise. Given that tennis imposes high unilateral force demands [

32,

39,

40], which can lead to muscular imbalances [

1,

7,

11,

41]and an increased risk of injury [

42,

43,

44,

45].

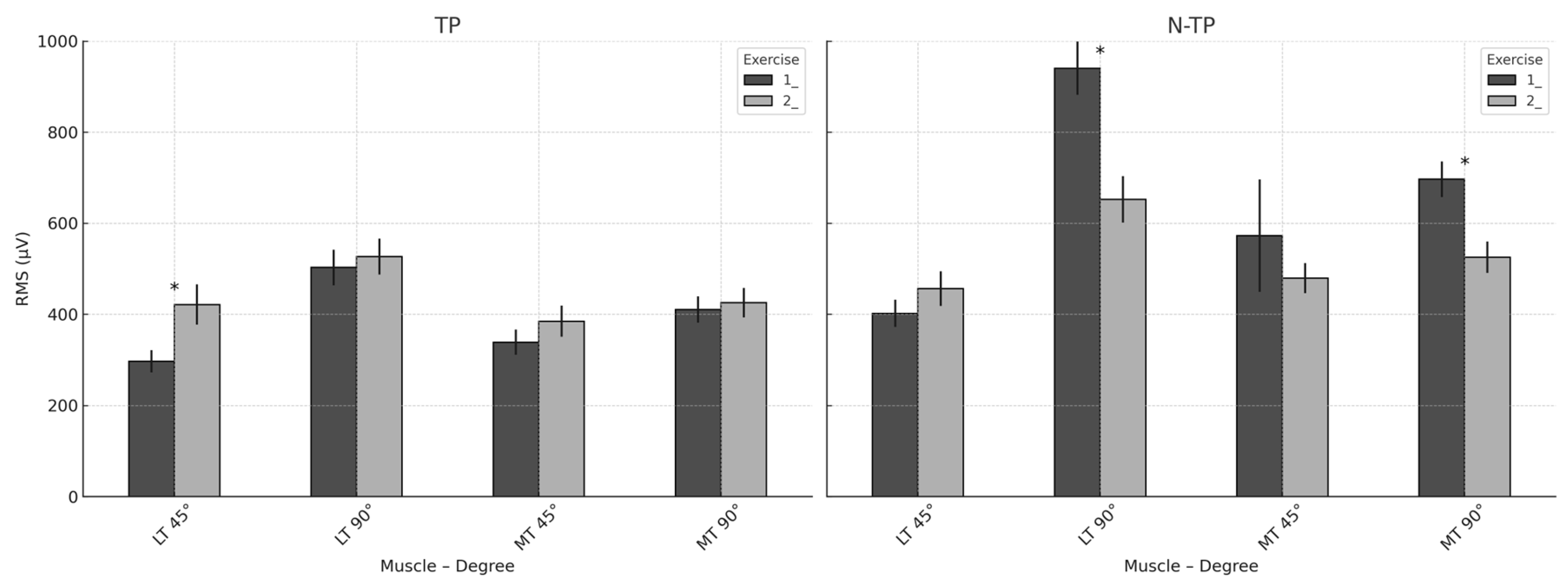

The primary aim of this study was to analyze the mean muscle recruitment at 90° and 45° of glenohumeral abduction between TP and N–TP during the first exercise. The results revelated several differences in muscle activation patterns between TP and N_TP.

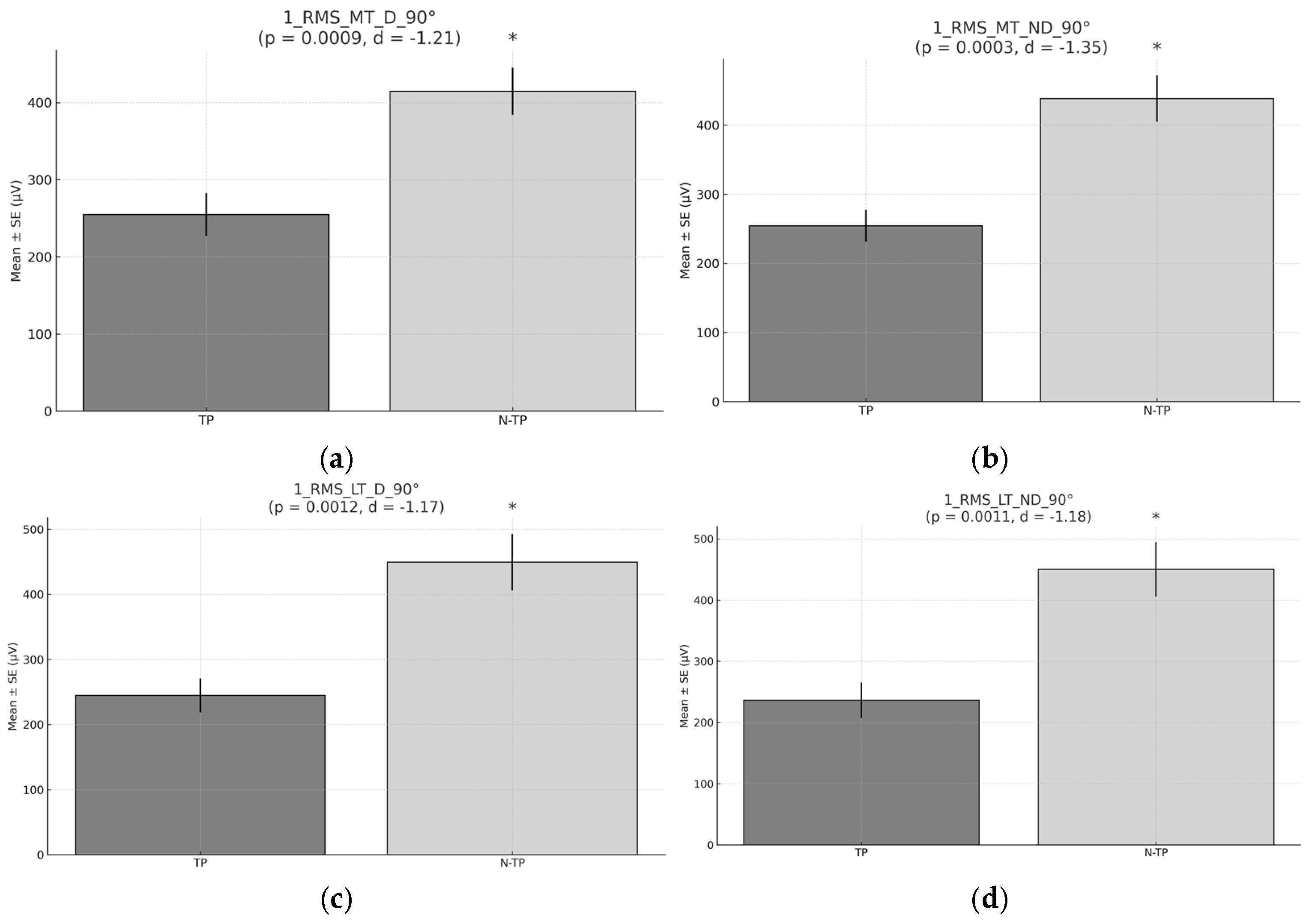

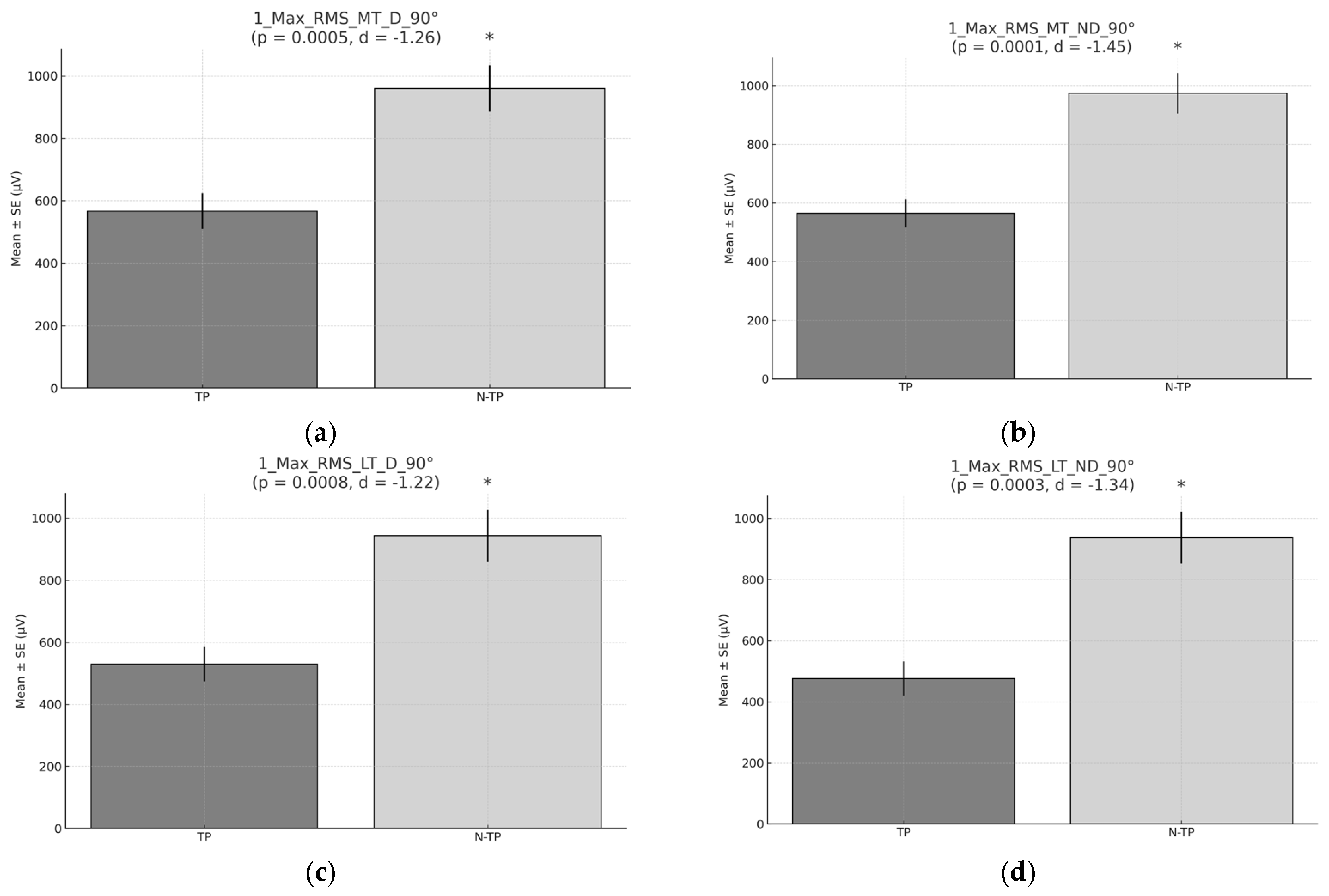

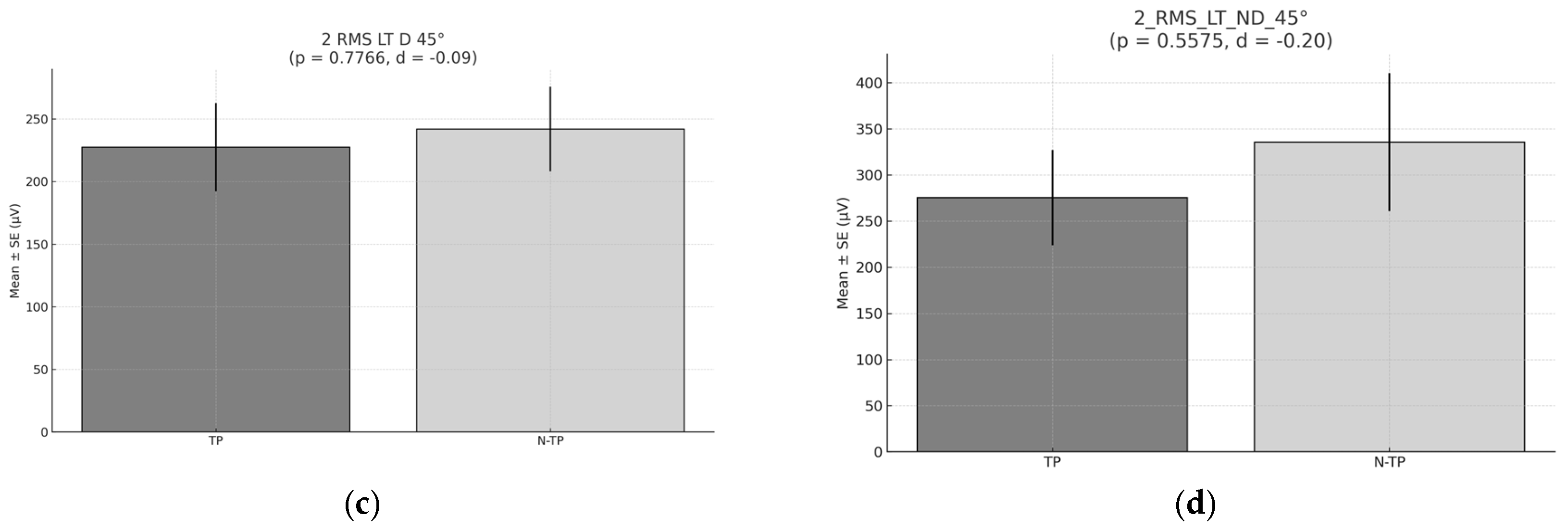

At 90° of glenohumeral abduction in exercise 1 (prone scapular retraction) N–TP exhibited significant higher mean RMS and RMS peaks for both D and ND sides and MT and LT muscles (

Figure 4). This difference was statistically significant, suggesting that muscle activation levels in N–TP were notably higher when performing the tested movement. A possible explanation for this finding is that tennis players, due to the high volume of repetitive unilateral movements—particularly through the dominant arm—experience repetitive stress on the shoulder, which may lead to neuromuscular adaptations that alter typical muscle activation patterns. [

2,

4,

46]. In contrast, non–tennis players, who do not participate in asymmetrical sports activities, tend to maintain a more balanced activation pattern across different muscle groups, as they are not exposed to the repetitive stress of high-intensity unilateral movements. In tennis players, this muscular imbalance may lead to compensatory mechanisms and overloading of specific muscles, such as the trapezius or scapular stabilizers, thereby impairing their function and increasing the risk of shoulder injuries[

47,

48]. Along the same lines, it could be suggested that TP exhibit signs of chronic fatigue or employ compensatory mechanisms that may reduce the activation of the lower and middle trapezius muscles. Unfortunately, to the best of our knowledge, there are no previous studies available for direct comparison regarding the activation patterns of the lower or middle trapezius. Existing research has primarily focused on the activity of the supraspinatus, infraspinatus, posterior deltoid, and pectoralis major during specific sport-related movements, rather than during preventive exercises such as those used in our study [

10]. When comparing the first exercise with the second (

Figure 4 and

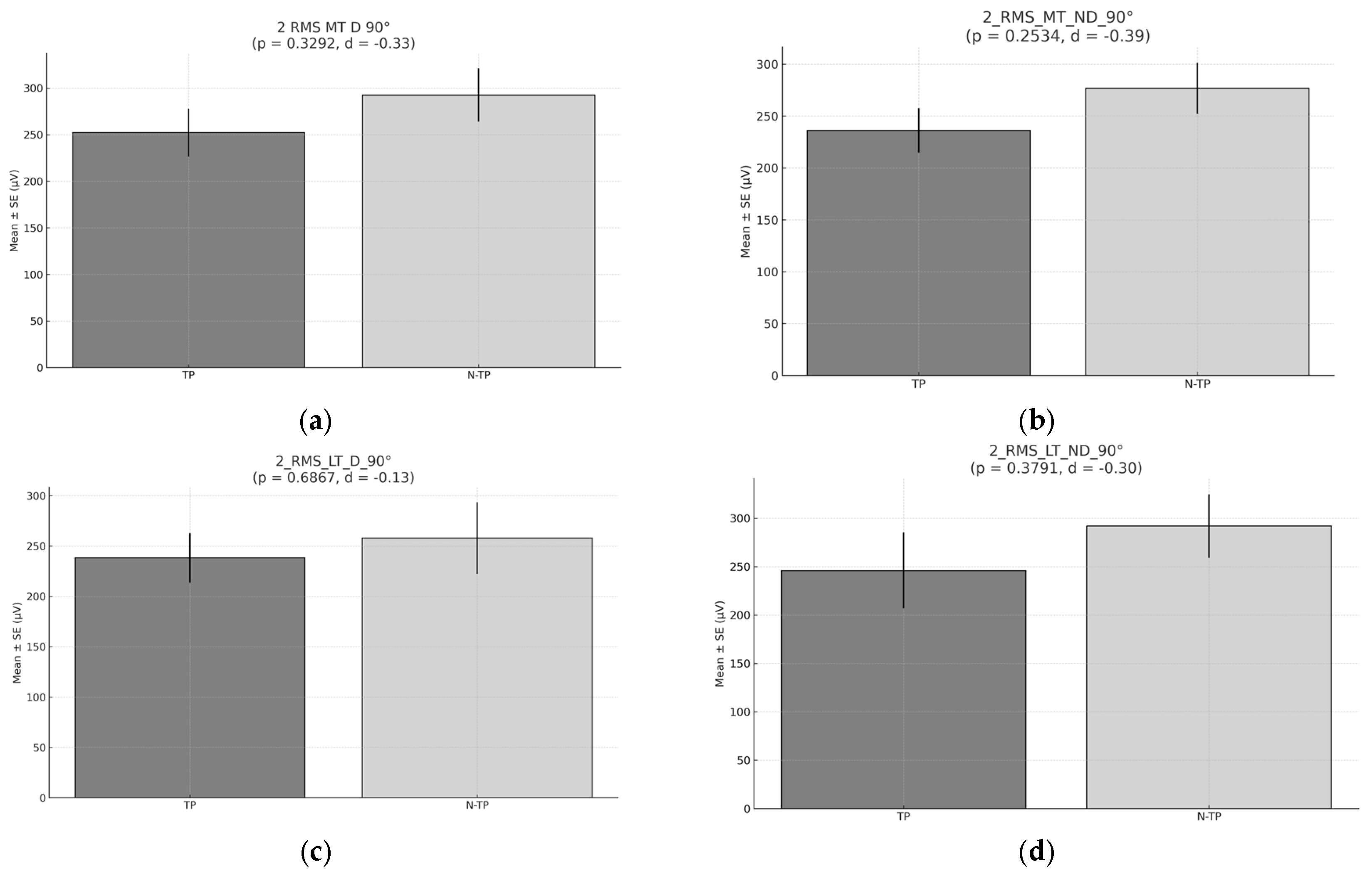

Figure 8), significant differences were observed during the first exercise at 90°, whereas no such differences were noted in the second exercise. Nevertheless, the mean muscle activation of the middle and lower trapezius muscles was generally higher in TP compared to non–tennis players. The primary distinction between the two exercises lies in body position, despite both aiming to achieve scapular retraction. In the first exercise, participants performed the movement in a prone position (lying face down), while in the second, the task was executed in a standing posture. This difference in positioning may explain the variation in muscle activation.

The prone position offers a more stable and balanced base of support, allowing for greater isolation and targeted recruitment of specific scapular stabilizers. In contrast, during the standing exercise, the body must actively maintain balance and posture, which demands greater involvement of trunk and pelvic stabilizing muscles. This additional requirement may redirect neuromuscular engagement toward supporting muscles—such as the deltoids or trunk stabilizers—thereby diminishing the relative activation of the middle and lower trapezius muscles compared to the prone condition [

48]. Gravity also influences the mechanics of the exercise, as standing requires the muscles to counteract a different distribution of forces, necessitating greater body stabilization during movement. This shift in mechanical demand may affect the specific activation of the scapular musculature [

47,

48,

49,

50].

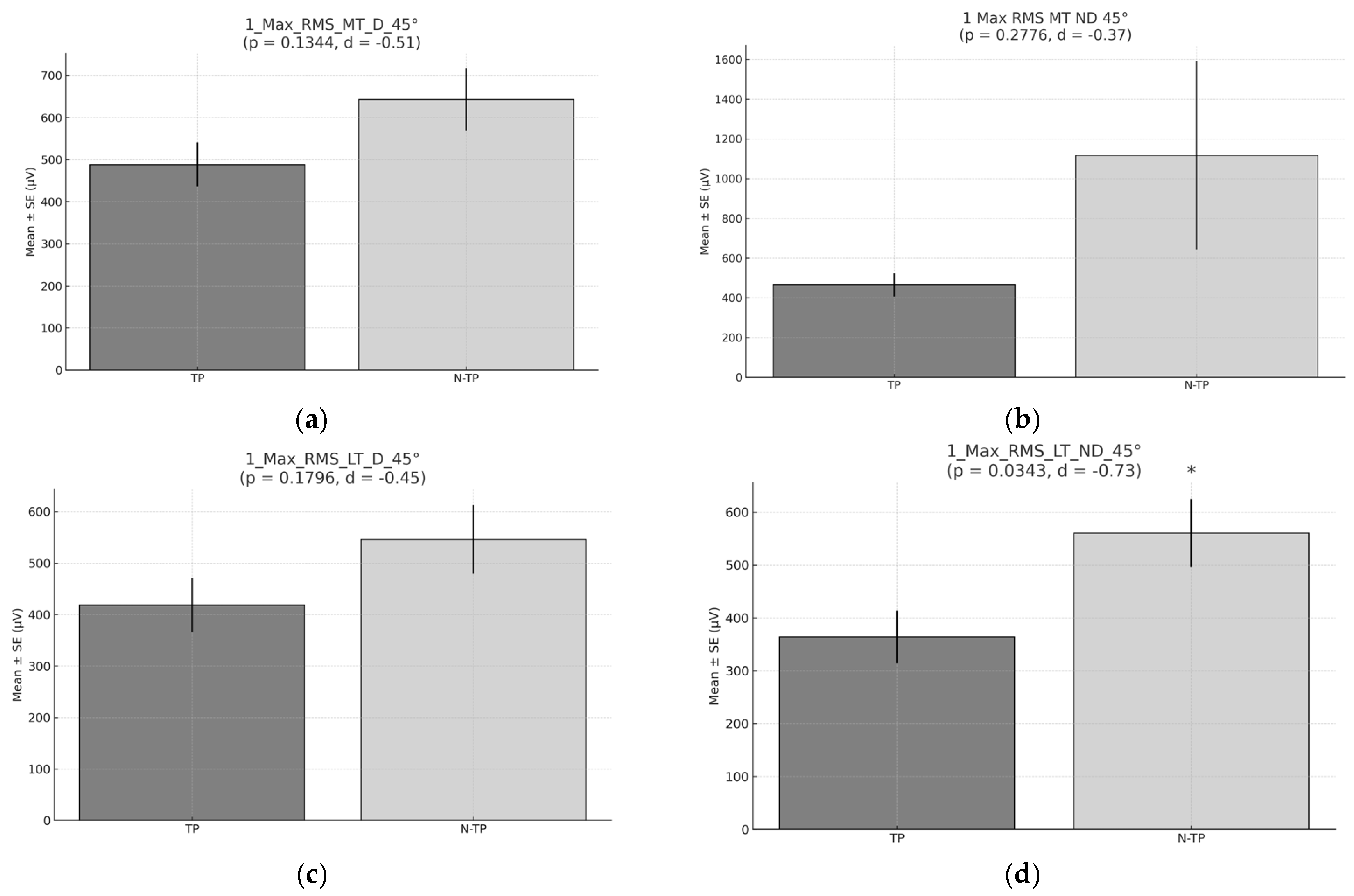

No significant differences were observed in the activation of the trapezius muscles between TP and N–TP during the execution of the first and second exercises (bilateral adduction in the prone position) at 45° of glenohumeral abduction. However, the median levels of muscle activation tended to be higher among non–tennis players. This observation may be explained by the fact that alterations in scapular kinematics related to trapezius activation have primarily been studied in the context of active shoulder flexion and abduction tasks. Evidence suggests that individuals with shoulder pain during arm elevation frequently exhibit dysfunctional scapular mechanics, characterized by excessive activation of the upper trapezius and reduced or delayed activation of the lower and middle trapezius, as well as the serratus anterior. The presence of scapular dyskinesis may indicate impaired neuromuscular control—either in terms of activation magnitude or timing—or insufficient strength of the scapulothoracic musculature [

50].Furthermore, in this position, TP may compensate for the movement with the deltoid, which could result in a reduced activation of the trapezius. The deltoid plays a role in controlling scapular retraction and arm abduction. However, instead of maintaining primary activation in the scapular stabilizers, such as the middle and lower trapezius, TP may rely on the deltoid [

21,

51]. This is particularly relevant for TP, who perform repetitive, high-load, unilateral movements, which can lead to suboptimal activation of the scapular stabilizers, such as the middle and lower trapezius. This imbalance in muscle activation and neuromuscular control may increase the risk of muscle imbalances and long-term shoulder injuries [

2,

3].

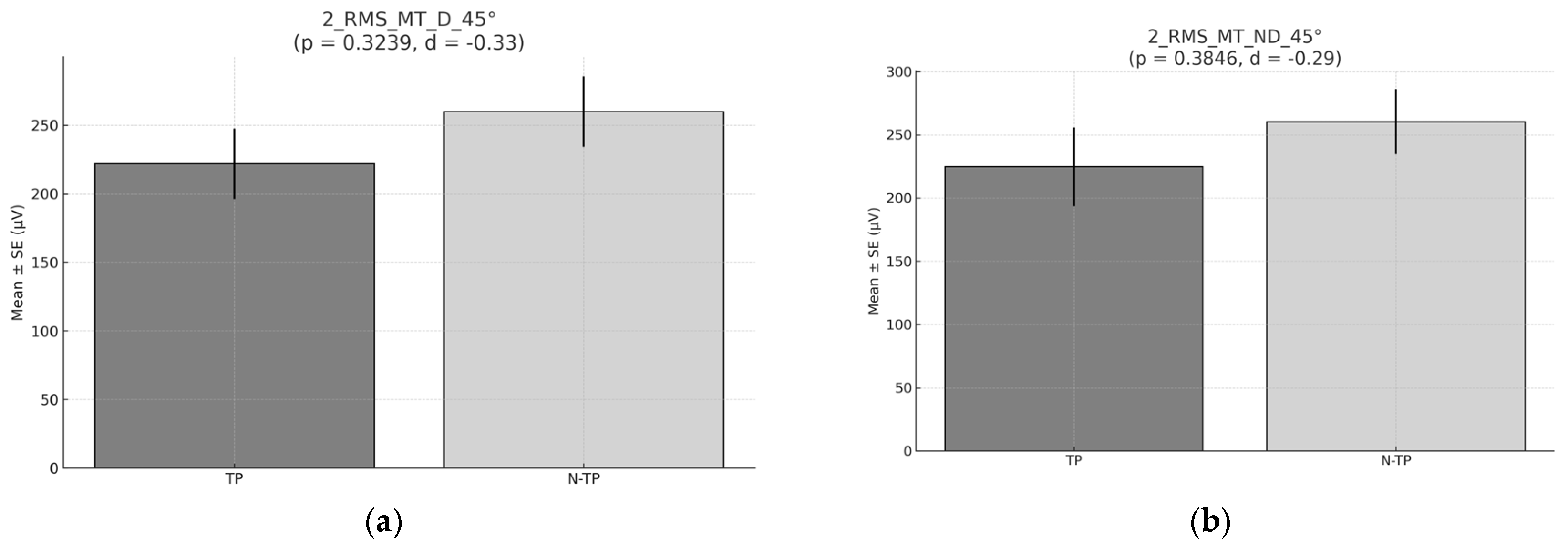

In relation to the results comparing asymmetries between TP and non-tennis players, we can observe that in the first exercise (

Table 4), TP show more symmetry, both at 90° and 45°. In contrast, in the second exercise, the results indicate greater symmetry in non-tennis players. However, it is important to highlight that at 45° in the second exercise (

Table 5), TP exhibit more asymmetry. This could be attributed to the fact that the specific sports gesture in tennis often occurs around 45°. Consequently, at this angle, the musculature may become unbalanced or misaligned, leading to the activation of other muscles to compensate for these imbalances. This may result in side differences (i.e., inter-limb asymmetry) between the stroke arm and non-stroke arm in terms of upper limbs’ performance, which can further increase with years of training [

52]. It is therefore essential to investigate these asymmetries and associated muscle activation patterns during the execution of preventive exercises. Furthermore, to account for sport-specific demands, we evaluated muscle activation and asymmetry at movement angles highly relevant to tennis, including 45°, rather than limiting the analysis to the traditionally examined 90°. While previous studies have primarily focused on joint range of motion at 90°, the inclusion of the 45° position in our study provides a more comprehensive and tennis-specific perspective on shoulder mechanics. This enhanced understanding could inform the development of more effective training interventions tailored for tennis players, ultimately aiding in injury prevention and performance improvement. Moreover, the sport-specific movements in tennis tend to involve high unilateral demand, which can create imbalances in muscle recruitment over time. In contrast, N–TP, who engage in less repetitive unilateral activity, might demonstrate more symmetrical muscle activation [

11,

53,

54]. Asymmetries between 10% and 15% are often associated with a higher risk of injury and reduced performance [

11].

Tennis players, especially at the 45°, might show more pronounced asymmetries because the muscles involved in tennis (such as the deltoids, rotator cuff, and scapular stabilizers) may develop differently on each side of the body. This asymmetry is due to the sport’s high reliance on one side of the body for specific actions, such as serving or forehand/backhand strokes [

52]. Over time, the body adapts, and these adaptations may cause an imbalance in muscle symmetry. At 90°, the differences may be less pronounced because the movement is less specific to the sport, thus minimizing the effect of this imbalance.

A crucial factor in altered scapular movement and/or shoulder injuries is the imbalance in scapular muscle activation, which includes reduced activation of the lower trapezius or middle trapezius. Functionally, the middle trapezius and lower trapezius contribute to scapular stability by limiting unnecessary vertical and horizontal displacements of the scapula and maintaining its proper positioning [

55,

56].

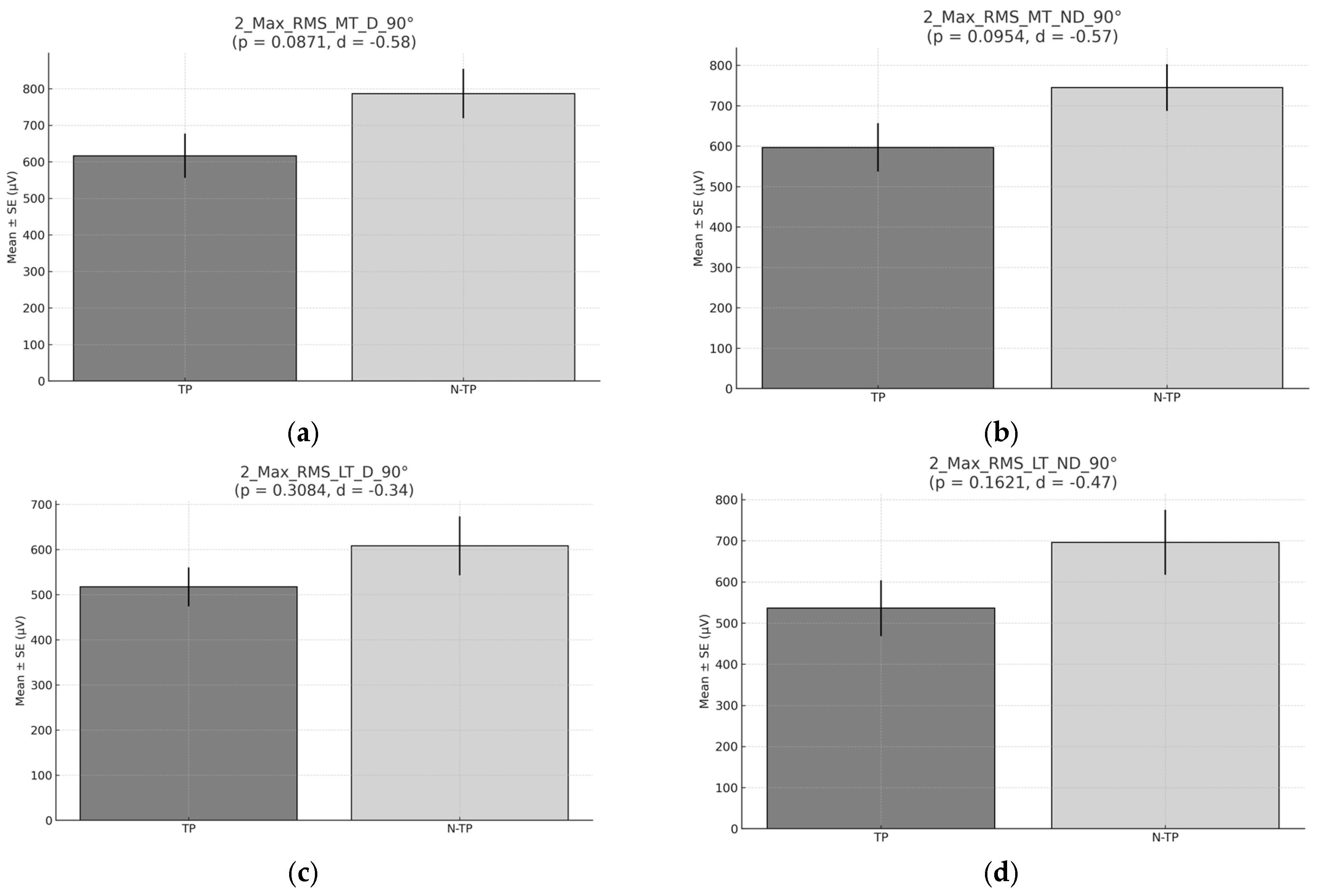

Another important contribution of the present study is the consideration of the peak RMS recorded during the three repetitions of the test. The results obtained during the execution of the first exercise on 90° (

Figure 6) show that, N–TP exhibit higher values compared to TP and are statistically difference of the peak RMS. The results suggest that N–TP exhibit greater activation of the middle and lower trapezius muscles, possibly due to a more balanced muscular performance pattern, as they do not engage in an asymmetric sport like tennis [

47,

53,

54]. Tennis, characterized by a high number of high-power groundstrokes performed unilaterally, which means that one side of the body bears the brunt of the force and muscular activation during the sport, and leads to muscle imbalances. The muscles responsible for generating movement are continuously engaged and overtraining [

46,

52,

57], while the muscles involved in stabilizing the shoulder and decelerating the movement, such as the middle and lower trapezius, are less frequently activated and may be relatively underdeveloped compared to those in non-tennis players, who engage in more balanced, bilateral activities. As a result, N–TP may demonstrate a higher activation of these stabilizing muscles during exercises designed to activate them, as they have a more uniform recruitment pattern.

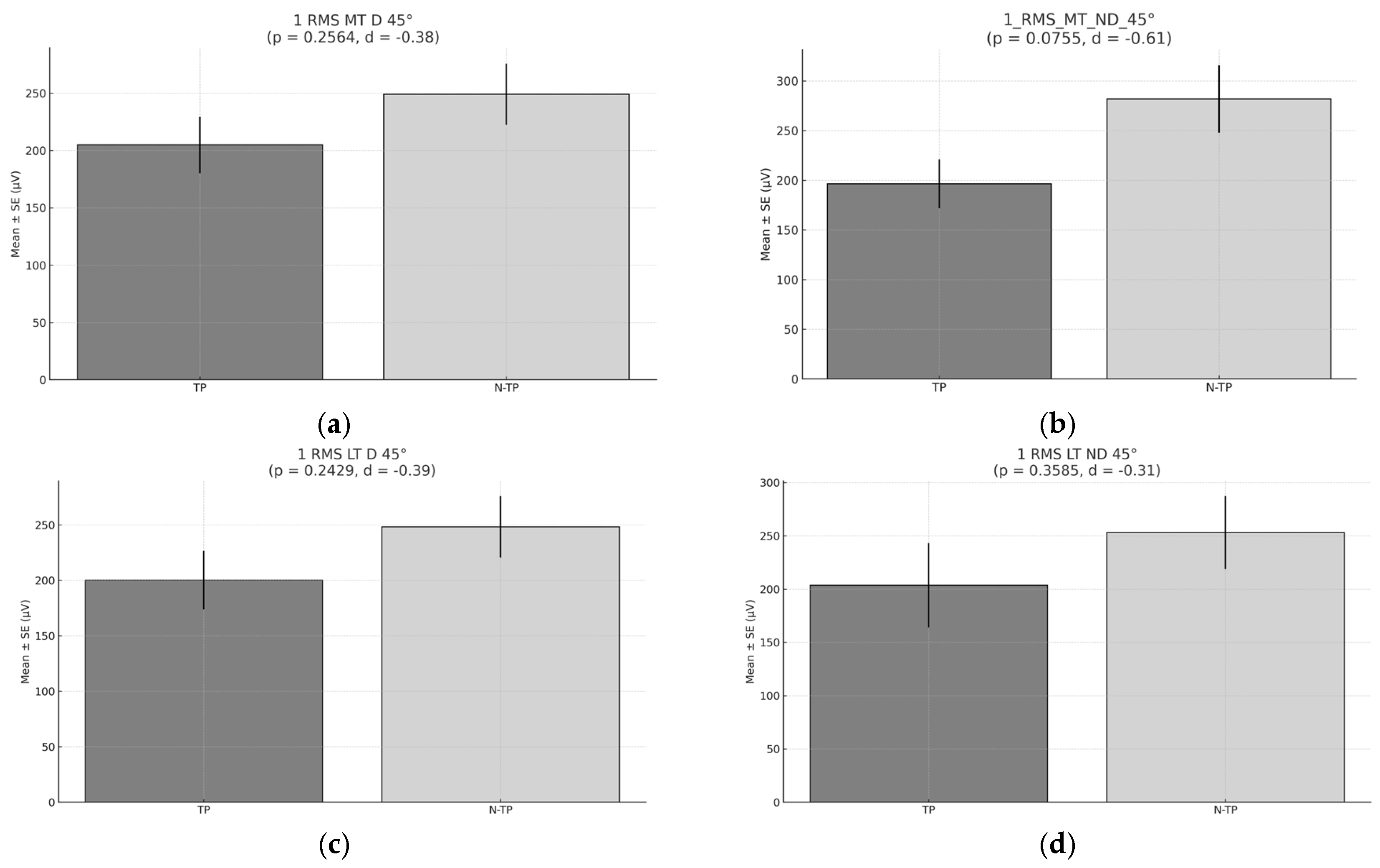

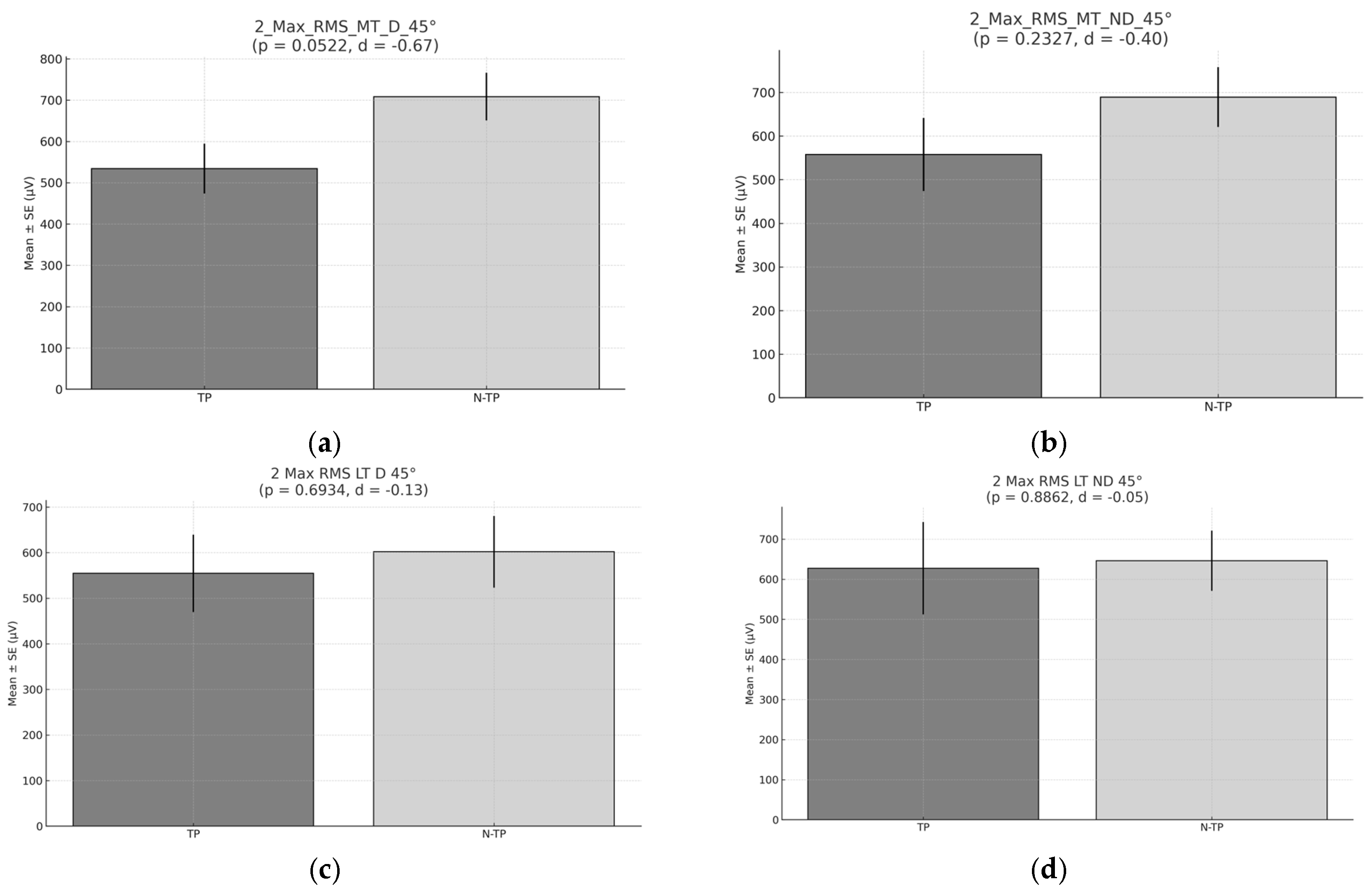

However, at 45° in the first exercise (

Figure 7), no significant differences were observed in the peak RMS between TP and non-tennis players. Even so, N–TP exhibited slightly higher RMS values. The absence of significant differences may indicate that, at 45°, the muscle activation patterns are more similar between both groups. Although most tennis strokes are performed at angles around 45°, the lack of significant differences in muscle activation during the preventive exercises at this angle may indicate that both TP and N–TP engage their trapezius muscles in a similar way during these specific exercises. Additionally, the position used in the first exercise involves a more stretched posture, which provides greater overall body stability and isolates the targeted muscles (e.g., trapezius) more effectively [

47,

48,

49,

50]. This isolation and stability allow for more consistent muscle activation patterns, potentially minimizing external factors that might otherwise influence the results. As a result, both TP and N–TP show similar muscle activation, since the exercise emphasizes controlled, isolated movements. Despite the specific angle of 45° being relevant for tennis strokes, the controlled environment of this exercise may reduce the impact of sport-specific imbalances, leading to similar activation levels between both groups [

54]. Non-tennis players, with less sport-specific asymmetry, may show more generalized activation patterns, contributing to the slightly higher RMS values observed in their group.

In the second exercise at 90° and 45° (

Figure 8 and

Figure 9), no significant differences were found between TP and N–TP. However, the mean peak RMS values were slightly higher in N–TP compared to tennis players. The explanation could be related to the postural differences and muscle recruitment patterns in standing exercises compared to exercises performed in a more stable, isolated position. In the second exercise (standing and scapular retraction), tennis players, who often perform dynamic, high-velocity movements, may have a higher degree of muscle recruitment efficiency in sport-specific actions, but they might not activate certain stabilizing muscles in exercises like scapular retraction [

48]. These muscles, including the middle and lower trapezius, might not be as actively engaged in TP due to the specificity of their training, leading to a lower RMS in comparison to non-tennis players.

Non-tennis players, however, may rely more on general muscle activation patterns when performing the scapular retraction in a standing position. Since they do not have the same specialized activation patterns developed through sport-specific training, they may activate a broader range of muscles, resulting in higher RMS values. Additionally, the standing position in this exercise could require greater overall recruitment of stabilizer muscles to maintain posture and perform the movement, which might be less specific to tennis and therefore cause N–TP to engage their muscles more uniformly.

Regarding the differences on the muscles activation across the purposed exercises, each exercise was performed at two shoulder abduction angles (45° and 90°). The analysis revealed differences in neuromuscular activation both between exercises and between athletic populations. When comparing EMG responses between two scapular retraction exercises—Exercise 1, performed in a prone position, and Exercise 2, executed standing with elastic resistance—among groups, in the TP, the maximal activation of LT in ND side recorded at 45° of glenohumeral abduction showed lower muscle activation in Exercise 1 (prone) compared to Exercise 2 (standing) (p = 0.0449, d = -0.77, moderate effect size). In contrast, in the N-TP group, the maximal activation of LT at 90° showed higher muscle activation in Exercise 1 (prone) compared to Exercise 2 (standing) in both dominant (p = 0.0027, d = 0.94, large effect size) and non–dominant side (p = 0.0422, d = 0.62, moderate effect size). This suggests a differential muscle recruitment strategy likely influenced by posture, stability demands, and elastic load.

Overall, prone scapular retraction (Exercise 1) tended to elicit greater muscle activation in variables with significant or moderate effects, especially in the TP group. This may reflect their greater familiarity with scapular control in closed kinetic chain positions, potentially due to sport-specific adaptations. In contrast, the N-TP group showed less consistent differences between exercises, suggesting a more generalized neuromuscular response. These findings support the inclusion of both prone and elastic band retraction exercises in shoulder rehabilitation programs, while tailoring angle and modality based on athletic background and neuromuscular demands. More specifically, the present findings suggest that the prone scapular retraction exercise (exercise 1) is more effective at activating the middle and lower trapezius muscles in tennis players, particularly at 90° of glenohumeral abduction. This pattern may be attributed to sport-specific adaptations associated with repeated overhead movements in tennis, which are known to alter scapular muscle recruitment patterns [

56,

58]. Prone shoulder horizontal abduction is commonly used to strengthen the lower trapezius. Previous studies comparing lower trapezius activation across various exercises have suggested that performing this exercise in alignment with the lower trapezius muscle fibers may enhance its activation [

47,

49,

59]. Additionally, research has shown that lower trapezius activation is greater at 125° of shoulder abduction compared to 160°, as the 125° position more closely aligns with the natural orientation of lower trapezius muscle fibers [

49].

The large effect sizes observed in the TP group (Cohen’s d > 1.0) reinforce the efficacy of prone-based retraction exercises in eliciting targeted activation of key scapular stabilizers. The lower trapezius plays a crucial role in maintaining scapular posterior tilt and external rotation during shoulder elevation—a function critical to reducing subacromial impingement risk [

58,

60,

61]. In contrast, the N-TP group demonstrated only a moderate effect in favor of the standing exercise at 45° for MT activation. This suggests that non-specialist athletes may benefit from more general approaches, while overhead athletes may require more specific positioning (e.g., prone, high abduction) to fully engage the scapular musculature.

The imbalance between upper trapezius overactivity and under-recruitment of the lower trapezius has been linked to shoulder dysfunction and injury in overhead athletes [

62]. Given the superior activation of LT and MT observed in prone exercises at 90°, incorporating such exercises into preventive programs may enhance scapular control, reduce the risk of impingement, and improve kinetic chain integration during service and overhead strokes [

63,

64]. Therefore, we recommend the integration of prone scapular retraction exercises at 90° abduction into shoulder injury prevention protocols for tennis players, particularly during the pre-season and preparatory phases. Additionally, progression to functional standing variations may be appropriate in later stages of training or for maintenance in less experienced athletes.

As a practical application, having knowledge about muscle recruitment and asymmetries could be important for the design of programs to increase the length of the shortest muscles in the limb, which present the greatest restrictions on external rotation, in order to prevent these restrictions from leading to future discomfort, biomechanical problems, or injuries of the scapulohumeral complex of this side. Another application of non-invasive electromyography (EMG) is to identify exercises that generate the highest activation of target musculature [

23,

59]. This enables the development of more precise and effective training regimens, specifically tailored to enhance the relevant muscle groups for tennis players. By using EMG to assess muscle activation during various exercises, we can optimize training programs that focus on the biomechanics of the sport, ensuring that exercises are aligned with the specific demands of tennis. This approach not only ensures more efficient muscle activation but also helps in reducing the risk of injury by promoting balanced muscle development, which is critical for improving athletic performance. Furthermore, tailoring training to the biomechanical demands of tennis allows for more sport-specific conditioning, which is essential for enhancing both strength and movement efficiency on the court. Moreover, coaches could choose between assessing at 45° or 90° depending on the technical deficits observed in their athletes, thus helping professional athletes avoid overuse problems and enabling non-professional TP to guarantee their correct technical development. For example, a proper tennis drive requires a glenohumeral position that optimizes power, precision, and control. This position involves several key biomechanical elements: The shoulder should be slightly abducted, typically between 45° and 90°, to allow a wide range of motion and take advantage of the torso and shoulder muscles for power generation [

65].

The present study have several limitations. Firstly, in this study, we focused exclusively on the muscle activation of the middle and lower trapezius. However, to enhance the validity of our findings, it would be beneficial to assess the activation of other scapular stabilizers, such as the infraspinatus, supraspinatus, and rhomboid muscles. These muscles play a crucial role in scapular stability and shoulder function. However, evaluating their muscle activation using surface electromyography (EMG) presents significant challenges due to their anatomical location. The infraspinatus and supraspinatus are deep muscles, partially covered by the deltoid, which can lead to signal crosstalk and reduced accuracy in EMG readings. Similarly, the rhomboid muscles are located beneath the trapezius, making it difficult to obtain reliable and isolated electromyographic data [

50]. Future research should consider alternative methods, such as fine-wire electromyography or imaging techniques, to better assess the contribution of these muscles to scapular stabilization.

Furthermore, the previous training load of the TP prior to the evaluation, as well as in the days leading up to the assessment, was not considered. Training load can significantly influence neuromuscular performance, muscle activation patterns, and fatigue levels, all of which may impact the results of electromyographic assessments. Neuromuscular fatigue is the exercise induced reduction in the ability to generate muscle force or power, regardless of whether the task can be sustained or not [

66]. Acute and chronic training loads have been shown to affect muscle recruitment strategies, potentially altering the activation of scapular stabilizers such as the trapezius, infraspinatus, and rhomboids. Insufficient recovery or accumulated fatigue from prior training sessions or during the session could lead to compensatory activation patterns or a decrease in muscle performance during testing [

66]

.

Finally, this study did not consider the age of the participants or their level of tennis proficiency, which could have influenced the results. The broad sample, without specific stratification by age and skill level, may limit the generalizability of the findings to specific populations, such as elite TP or developing athletes. Experience has been interpreted as

functional specialization, which leads to structural and functional adaptations in the neuromuscular system due to long-term tennis practice. Although the emergence of functional specialization initially suggests a potential advantage (e.g., more powerful and faster stroke actions), evidence indicates a decline in physical performance if asymmetry exceeds a certain threshold. Despite the documented negative effects of neuromuscular asymmetry on lower limb athletic performance, there is a lack of studies investigating its impact on upper limb performance. This is particularly surprising, as neuromuscular asymmetry in upper-quarter mobility and stability has previously been associated with an increased risk (i.e., risk ratio: 1.2) of sustaining a time-loss musculoskeletal injury in the future [

52]

. To enhance the validity and relevance of future research, it would be beneficial to define a more specific age range and classify participants according to their playing level. This approach would allow for a more precise analysis of individual differences and their impact on shoulder mechanics.