1. Introduction

The rotator cuff (RC) is a critical musculotendinous structure that reinforces the glenohumeral joint capsule and plays an essential role in facilitating normal shoulder movement. Because of its proximity to the shoulder joint, the RC moves in coordination with the joint and can assist in preventing joint translation [

1]. Among the RC muscles, the subscapularis (SSC) functions as a powerful internal rotator and stabilizer of the shoulder joint, exerting a compressive force that positions the humeral head within the glenoid fossa during shoulder movements [

2]. Additionally, the SSC exerts a downward force on the humeral head, counteracting the upward pull generated by the deltoid muscle contraction during shoulder abduction [

3], and exerts forward pressure on the humeral head to prevent translation caused by extensors during shoulder extension [

4,

5].

SSC weakness or injury is commonly observed in athletes and non-athletes, particularly in individuals who frequently perform repetitive overhead arm movements [

6]. During such movements, the overall arc of the shoulder joint shifts posteriorly to increase the range of external rotation, causing the greater tuberosity to be pulled further beyond the glenoid fossa, thereby reducing the internal rotation range [

7,

8]. Sustained repetitive movements increase the range of external rotation and contribute to retroversion of the humeral head and glenoid fossa, resulting in anterior capsular laxity and reduced internal rotation. [

9,

10,

11]. Jobe et al. (1989) termed this condition “subtle instability” and identified it as contributing factor to labral tear and RC rupture [

12]. Paley et al. (2000) further reported that anterior instability is the most significant contributor to internal impingement during shoulder internal rotation [

13]. Limitations in the internal rotation range of motion may restrict overall shoulder mobility and are considered key contributors to soft tissue dysfunction, pain, and muscle atrophy. Therefore, it is necessary to find the most effective exercise method and provide evidence to restore and maintain normal shoulder internal rotation function [

14].

Researchers have evaluated the function and strength impairments of the shoulder internal rotation muscles using various tests. The Belly Press and Lift Off tests are commonly used assessments for SSC, and therapeutic exercises based on these two evaluation methods have been shown to significantly strengthen the SSC [

15,

16]. Some studies have also shown that internal rotation range of motion training during rehabilitation after the RC surgery strengthens the SSC [

17,

18]. Fritz et al. (2017) demonstrated daily shoulder rotation exercises following the RC surgery increased RC muscle strength, including the SSC, and improved rotation range, as assessed via 3D motion analysis and surface electromyography (EMG) [

19].

Unlike EMG, ultrasound can measure changes in muscle contraction by assessing soft tissue thickness, and its application to RC assessment is well known [

20,

21]. Smith et al. (2011) reported that the sensitivity of ultrasound in detecting full-thickness rotator cuff tears ranged from 92.4% to 96%, while the specificity ranged from 93.0% to 94.4% [

21]. For partial-thickness tears, the sensitivity ranged from 66.7% to 84%, and the specificity ranged from 89% to 93.5% [

21]. Researchers also have investigated ultrasound-based techniques for probing RC muscles and surrounding musculature from multiple angles [

22], and for monitoring post-operative muscle recovery [

23].

According to Sahrmann, the movement of any joint creates a path of instantaneous center of rotation (PICR) [

24]. When the PICR is minimized, stability and normal movement are provided to the joint. A previous study reported that the minimized PICR of the glenohumeral joint during shoulder external rotation was achieved through activation of the infraspinatus muscle (IS), which acts as both a stabilizer and a prime mover for shoulder external rotation. As a result, the posterior deltoid muscle (PD) was able to perform shoulder external rotation more stably and generate a large torque. [

25]. In a study aimed at strengthening the shoulder external rotation muscles in patients with shoulder impingement syndrome, Park (2018) reported that precise joint movement could occur when the center of rotation of the glenohumeral joint was maintained in the same position during arm movement [

26]. However, few studies have investigated the influence of the SSC on PICR as a stabilizer and prime mover during shoulder internal rotation.

Although various SSC exercises have been studied, there is insufficient evidence regarding which exercises can selectively strengthen the SSC compared to other shoulder rotator muscles. Therefore, this study aimed to compare the effects of the SSC strengthening exercises and to determine which exercise most effectively activates the SSC selectively. The SSC exercises were Lift Off, Belly Press, and Prone Wiper. We have developed Prone Wiper, which was performed with the shoulder and elbow flexed to 90° in prone position. This study measured changes in the activation of the SSC and IS using ultrasound, as these muscles are not easily measured with surface EMG. The activity of superficial shoulder rotator muscles was measured using surface EMG and compared to SSC and IS activation. We also analyzed PICR during shoulder internal rotation using diagnostic imaging equipment to identify the relationship between PICR and muscle activation patterns.

2. Materials and Methods

2.1. Participants

We used G*Power version 3.1.9.2 software to calculate the required sample size. A minimum of 28 participants was required to attain an α level of .05 and a statistical power of .8. A total of 40 participants (20 males, 20 females; age = 38.95 ± 3.32 years, height = 166.447 ± 6.72 cm, weight = 65.55 ± 11.38 kg) without any shoulder complex conditions were recruited for this study. Individuals with a history of shoulder pain, or musculoskeletal or neurological conditions affecting shoulder internal rotation were excluded. All participants read and signed the university-approved human subjects consent form. The study was approved by the Daegu University Institutional Review Board (1040621-201901-HR-009-02).

2.2. Ultrasonography

A diagnostic ultrasound system (ACCUVIX V10, Samsung Medison, South Korea) equipped with a 6–12 MHz broadband linear probe (L5-13IS) was used to measure the muscle thickness of the SSC and IS. To measure SSC thickness, the probe was positioned on the lesser tubercle of the humerus at the beginning of each exercise. For IS thickness, the probe was positioned on the infraspinous fossa, approximately 4 cm below the scapular spine and aligned parallel to it [

22,

23]. The participants performed each exercise with the probe in a fixed position. The criteria for measuring muscle thickness were defined as follows: for the SSC, the distance between the highest point of the lesser tubercle and the lowest point of the fascia overlying the SSC; for the IS, the distance between the highest point of the superior fascia of the IS and the highest point of the infraspinous fossa [

22,

27].

2.3. Surface Electromyography

Surface EMG (TeleMyo DTS, Noraxon Inc., Scottsdale, AZ, U.S.A) was used to measure the activity of the anterior deltoid (AD), pectoralis major (PM), and PD muscles. The TeleMyo DTS directly transmits myoelectric data from the electrodes to a belt-worn receiver. EMG electrode placement for each muscle followed established protocols from previous studies [

4,

28]. For the AD, electrodes were placed 4 cm below the clavicle on the anterior aspect of the humerus. For the PM, electrodes were placed 2 cm medial to the axillary fold, toward the sternum. For the PD, electrodes were placed 2 cm below the lateral border of the scapular spine and angled obliquely toward the humerus. Before attaching electrodes, the skin was shaved and then cleaned with alcohol-soaked paper cotton. The EMG data were acquired at a sampling rate of 1,000 Hz. Signal preprocessing included band-pass filtering using a finite impulse response filter (40–250 Hz), a 60 Hz notch filter to eliminate power line interference, and an infinite impulse response filter for additional noise suppression. Finally, the signals were full-wave rectified to prepare for subsequent analysis.

For signal normalization, the root mean square (RMS) values were calculated from 5-second maximal voluntary isometric contractions (MVICs) performed three times for each muscle. For the AD test, participants were seated in a short sitting position with the arms at their sides, elbows slightly flexed, and forearms pronated. They then flexed the shoulder to 90° without rotation or horizontal movement. Scapular abduction and upward rotation were permitted during the movement. Manual resistance was applied by the examiner, with one hand positioned over the participant’s distal humerus just proximal to the elbow, while the other hand stabilized the shoulder. [

29]. For the PM test, participants were positioned in a supine position with the shoulder abducted to 90° and the elbow flexed to 90°. They then performed shoulder horizontal adduction through the available range of motion. Manual resistance was applied by the examiner, with one hand positioned around the participant’s forearm just proximal to the wrist [

29]. For the PD test, participants were seated in a short sitting position with the shoulder abducted to 90° and the elbow flexed to 90°. Manual resistance was applied by the examiner, with one hand positioned around the participant’s wrist, while the other hand supported the elbow to provide counterpressure at the end of the range of motion [

29]. Each contraction was sustained maximally for 5 seconds. For data analysis, the middle 3 seconds of each MVIC were used, excluding the first and last second to eliminate transitional artifacts. Each test was repeated three times, with a 2-minute rest between repetitions to minimize muscular fatigue. The examiner carefully monitored the participants during the isometric contractions to prevent any compensatory movements. EMG data from each trial were normalized to the RMS value obtained from the MVIC and expressed as a percentage of MVIC (%MVIC). The mean %MVIC across the three trials was used for statistical analysis [

28].

2.4. Radiography

Radiographic imaging (Accuray D5, DK Medical Systems Co. Ltd., Korea) was performed to measure the displacement of the glenohumeral joint axis during the shoulder internal rotation exercises. All radiographs were acquired by the same radiologist to ensure consistency in image acquisition. A radiographic grid was positioned over the participant’s glenohumeral joint by the radiologist, and images were acquired both before and after the shoulder internal rotation. The center of joint rotation was defined as the midpoint of the line connecting the greater and lesser tubercles of the humeral head. Displacement of the center of rotation was determined by measuring the positional shift of the defined midpoint in a direction perpendicular to the line connecting the superior and inferior margins of the glenoid fossa. The magnitude of displacement was calculated by subtracting the vertical position of the joint center before internal rotation from its position after internal rotation [

26].

2.5. Procedure

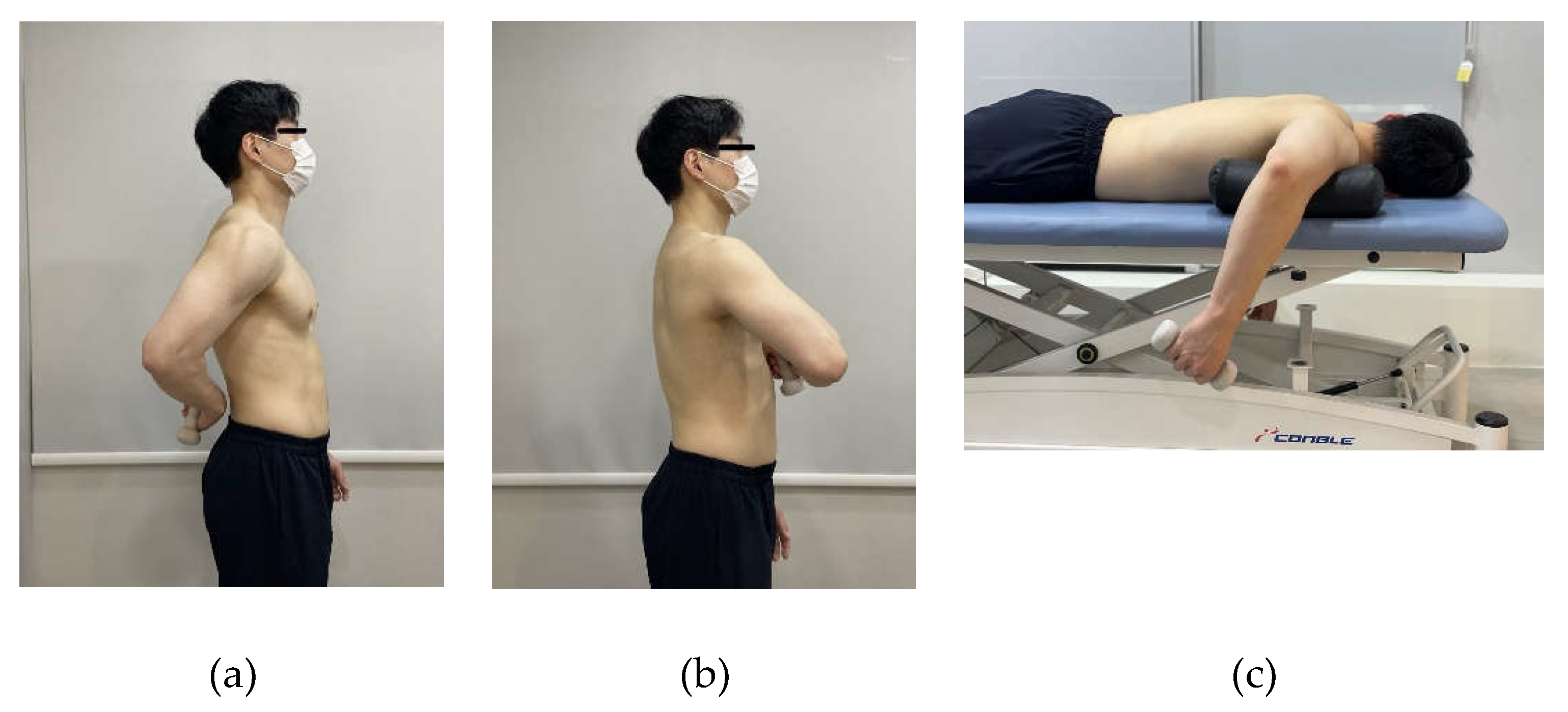

This study was aimed to identify the most effective exercise for selectively strengthening the SSC, which functions as a stabilizer during shoulder internal rotation. All exercises were performed using the participants’ dominant arm, identified as the arm typically used for eating and writing. The three exercises - Lift Off, Belly Press, and Prone Wiper (

Figure 1) - were performed in randomly assigned order. Before exercise familiarization, the examiner measured the resting muscle thickness of the SSC and IS for each participant. The participants then practiced for 30 minutes to become familiar with maintaining a 5-second isometric contraction for each of the three rotation exercises. After completing the familiarization session, the participants rested for 15 minutes prior to the measurement phase, which was performed using a 1-kg dumbbell. Each participant completed three trials of each exercise with a 1-minute rest between trials and a 3-minute rest between exercises to minimize muscle fatigue [

28]. For the Lift Off, participants stood upright and placed the dorsum of the tested hand on the midpoint of the lumbar spine, assuming a position of shoulder internal rotation. Upon a verbal cue from the examiner, participants lifted the hand away from the spine as far as possible, performing additional internal rotation while maintaining the shoulder in a fixed position. The lifted position was held for 5 seconds and then returned to the starting position following a second verbal cue. [

4,

16]. For the Belly Press, participants stood upright with the palm of the tested hand placed just below the xiphoid process and the elbows aligned horizontally, maintaining the trunk in the sagittal plane. Upon a verbal cue from the examiner, participants pressed the abdomen with the palm while keeping the shoulder stabilized, and extended the elbow forward away from the trunk as far as possible. The position, which reflects shoulder internal rotation, was held for 5 seconds and then released to the starting posture following a second verbal cue. [

4,

16]. For the Prone Wiper, participants were positioned prone with the shoulders abducted to 90° in the horizontal plane and the elbows flexed to 90°. Upon a verbal cue from the examiner, participants performed maximal shoulder internal rotation while maintaining the shoulder in a stabilized position. The internally rotated position was held for 5 seconds, after which participants returned to the starting position following a second verbal cue. [

30].

2.6. Statistical Analysis

A one-way repeated-measures analysis of variance (ANOVA) was conducted to compare the changes in muscle activity, muscle thickness, and PICR among the three exercises. Post hoc comparisons were performed using Bonferroni adjustment. A value of p<.05 was considered to indicate statistical significance. Effect sizes (Cohen’s d) were calculated to compare standardized mean differences among exercise conditions. Effect sizes were interpreted as small (0.20), medium (0.50), or large (0.80), based on Cohen’s conventional thresholds. Statistical analyses were conducted using SPSS version 18.0 for Windows (SPSS Inc., Chicago, IL, USA).

3. Results

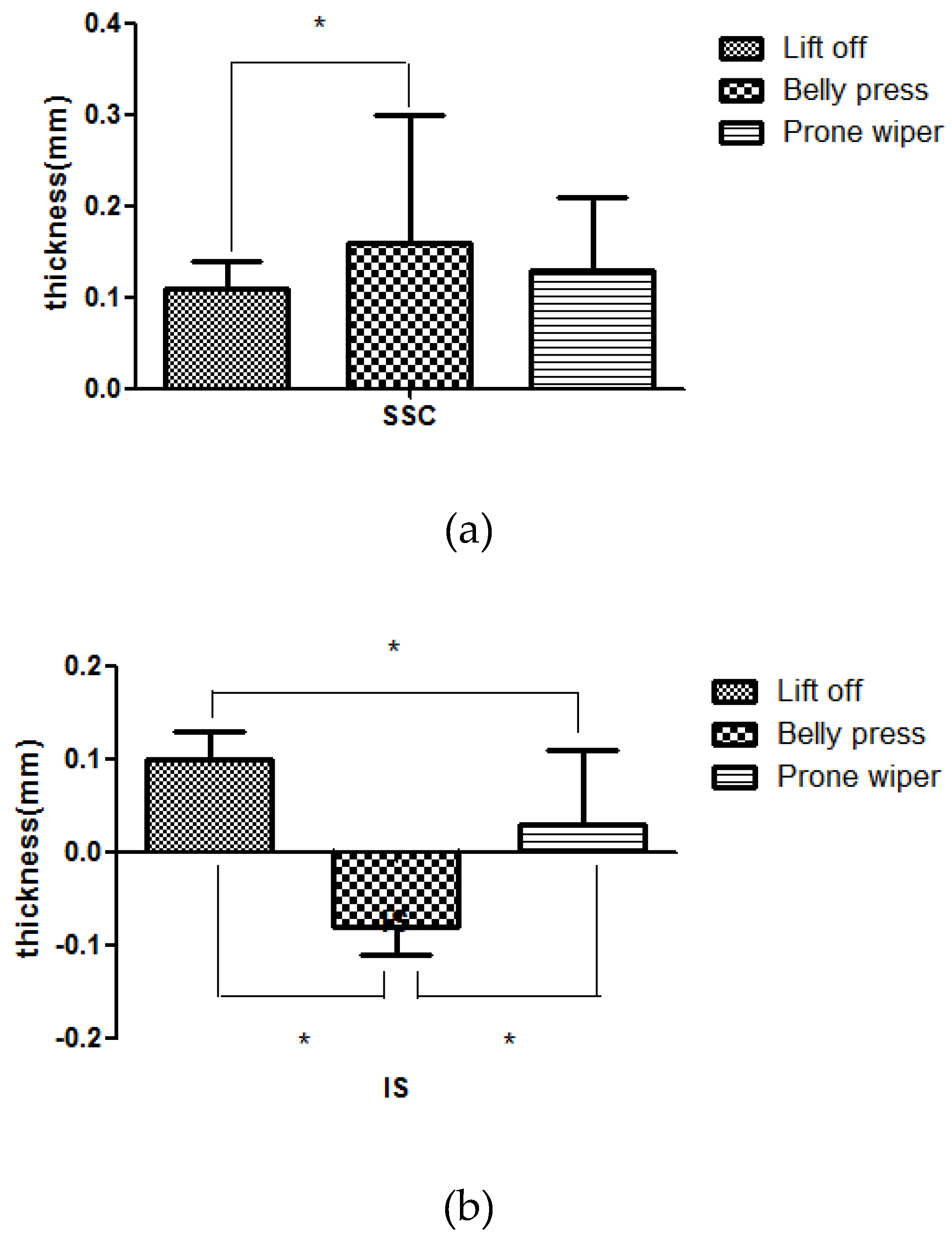

3.1. Muscle Thickness

A significant decrease in IS thickness during shoulder internal rotation was observed only in the Belly Press condition (

p<.05). Except for this case, the thickness of all measured muscles significantly increased following shoulder internal rotation across all exercise conditions (

p<.05) (

Table 1). When comparing the three exercises, most changes in the muscle thickness of the SSC and IS showed significant differences (

p<.05). A significant difference in SSC thickness was found between the Belly Press and Lift Off (

p<.05), whereas no significant differences were observed between Belly Press and Prone Wiper or between the Lift Off and Prone Wiper. Changes in IS thickness showed significant differences among all three exercises (

p<.05)(

Figure 2).

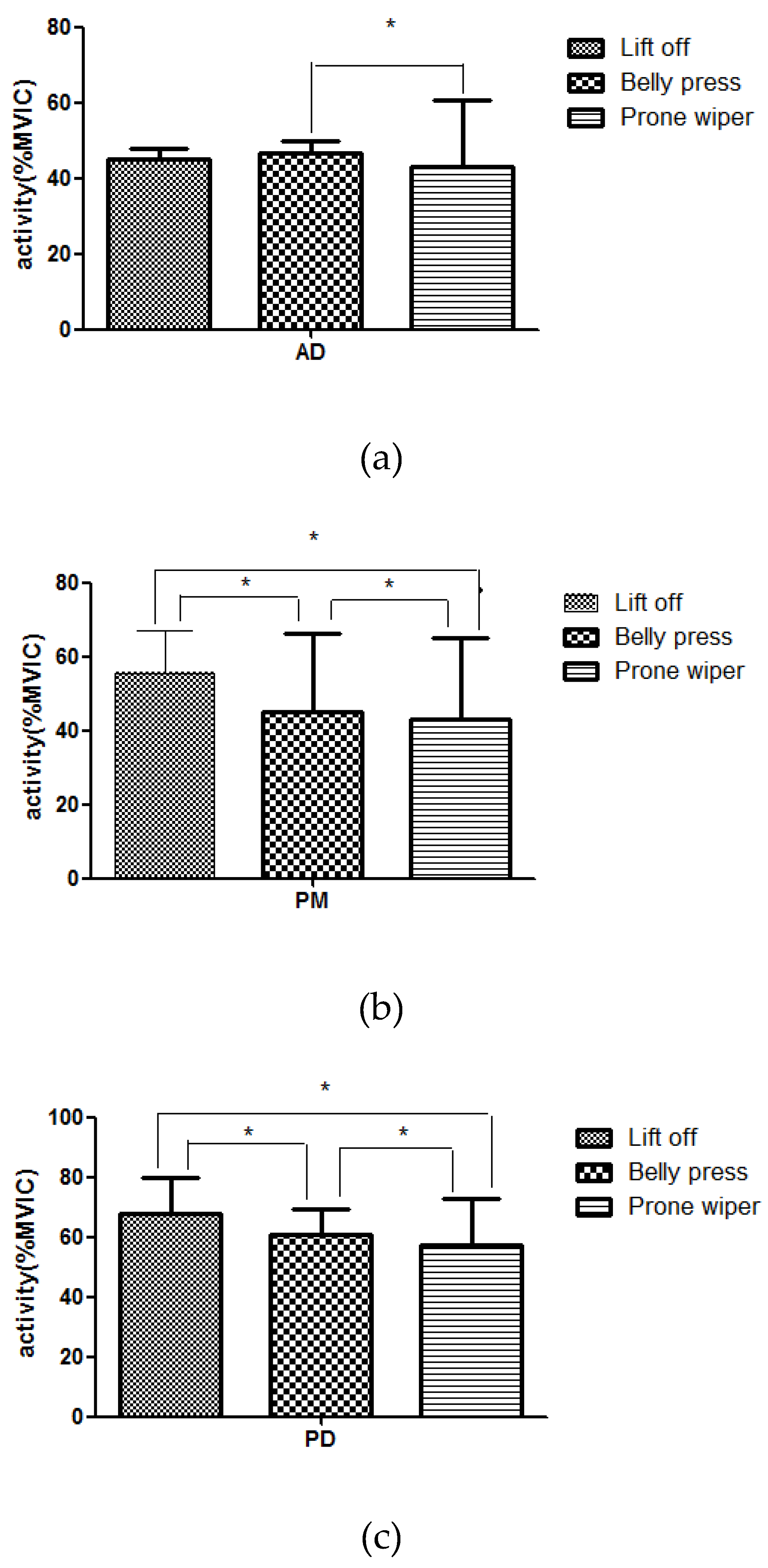

3.2. Muscle Activity

Muscle activity of the AD, PM, and PD significantly increased following shoulder internal rotation across all exercises (

p<.05)(

Table 2). A significant difference in AD activity was observed between the Belly Press and Prone Wiper (

p<.05), whereas no significant differences were found in the other pairwise comparisons. In contrast, changes in PM and PD activity showed significant differences among all three exercises (

p<.05)(

Figure 3).

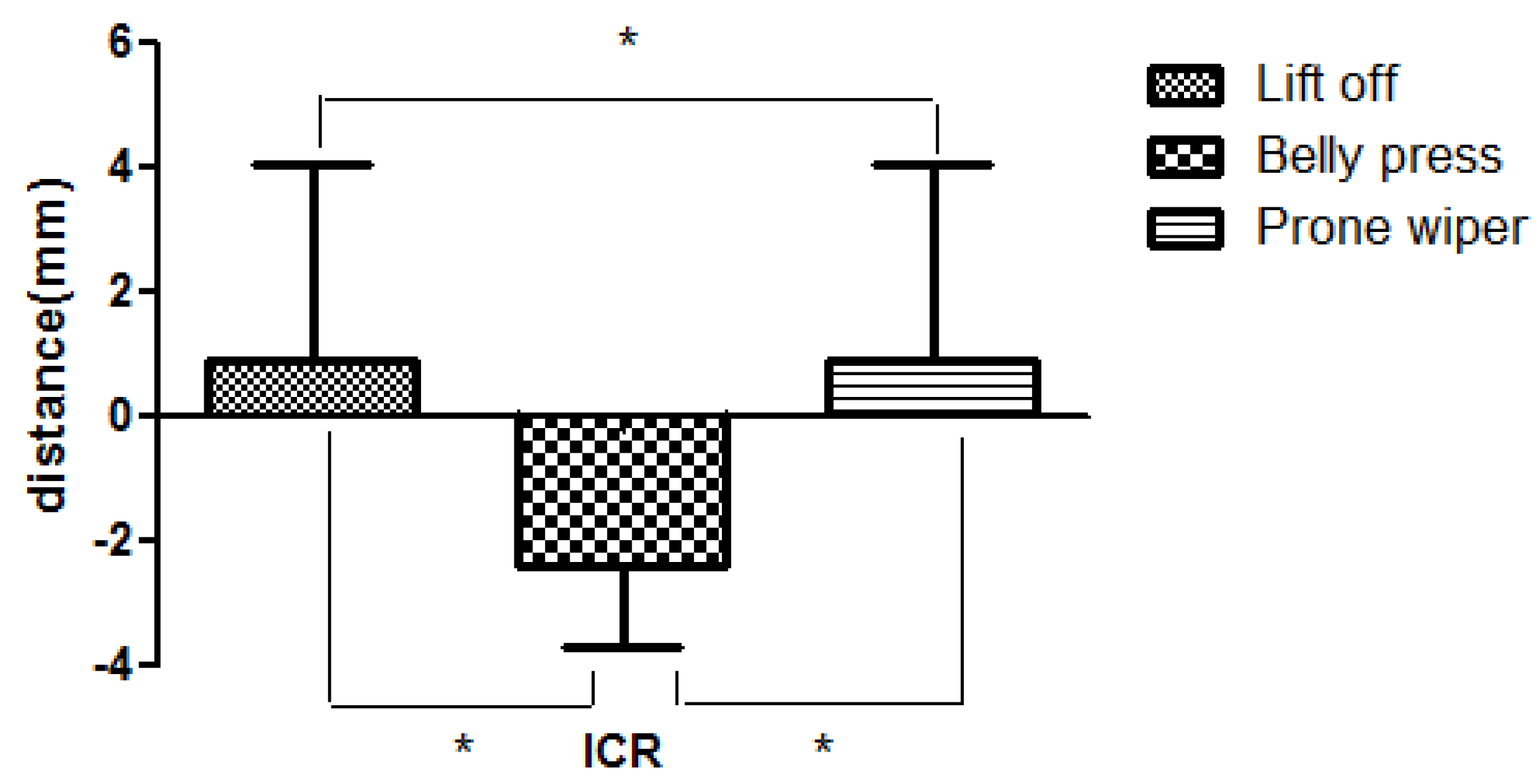

3.3. PICR

The PICR significantly decreased during the Belly Press (

p<.05), whereas it significantly increased following movement in both the Lift Off and Prone Wiper (

p<.05)(

Table 3). Comparative analysis revealed significant differences in PICR changes of the glenohumeral joint across all three exercises (

p<.05)(

Figure 4).

4. Discussion

The importance of the SSC in the treatment and management of RC injuries is well established. This study aimed to determine which exercise most effectively targets the SSC and to provide evidence for its use. To this end, we compared three exercises that are commonly used to improve shoulder internal rotation function: the Lift Off, the Belly Press, and the Prone Wiper. We then compared their effects on muscle thickness, muscle activity, and PICR changes.

Previous studies have shown that the IS functions as a stabilizer by generating a compressive force to maintain the humeral head within the glenoid fossa during shoulder abduction and external rotation [

28]. The SSC also acts as a stabilizer by pulling the humeral head inferiorly to prevent superior translation during abduction, and by resisting anterior translation during shoulder extension, thereby helping to center the humeral head in the glenoid fossa [

4]. In a study on post-operative rehabilitation exercises for patients with RC injuries, Sgroi et al. (2018) found that prone external rotation with the shoulder abducted to 90° produced the greatest activation of the IS. Additionally, internal rotation performed in a standing position with the shoulder abducted to 90° was found to elicit greater activation of the supraspinatus, IS, and SSC [

18]. The observed increase in thickness in both the SSC and IS during the Lift Off and Prone Wiper exercises may reflect the coordinated action of these muscles functioning as stabilizers to maintain humeral head positioning within the glenoid fossa [

31]. Another study compared the effects of various internal shoulder rotation exercises - including the Lift off and Belly Press - on strengthening the SSC, and found that the SSC was strengthened to a similar extent regardless of the exercise posture [

4]. However, the study also reported a significant reduction in the activation of other rotator muscles, with the exception of the SSC, during the Belly Press. This aligns closely with our findings, where the Belly Press significantly increased SSC thickness while decreasing IS thickness. Given the antagonistic relationship between the SSC, an internal rotator, and the IS, an external rotator, activation of one muscle may inhibit the activity of the other. [

32]. Therefore, the significant decrease in IS thickness observed during the Belly Press may have facilitated more efficient SSC activation, as reflected by the greater increase in SSC thickness compared to the others.

The muscle activity of the AD, PM and PD increased significantly across all exercises. The AD and PD function as a force couple with the RC, contributing to shoulder elevation and rotation. Additionally, the PM contributes to shoulder elevation and abduction through the coordination with the latissimus dorsi and teres major muscles [

33]. The SSC acts synergistically with these muscles to stabilize the humeral head inferiorly during shoulder elevation and abduction. Proper functioning of the scapular stabilizer muscles is critical for maintaining the center of rotation of the glenohumeral joint. Achieving an optimal balance between mobility and functional stability during shoulder rotation is essential for the effective distribution of the substantial forces acting on the shoulder joint [

33]. Reinold et al. (2007) found that PD activation was significantly higher in the internally rotated empty-can position compared to the externally rotated full-can position [

34]. Malanga et al. (1996) also reported that the AD and PM activation significantly increased in the Jobe position, which involves internal rotation of the shoulder [

1]. In addition, Kelly et al. (1996), in a manual muscle testing study of the RC, observed that internal rotation led to increased activation of the IS and PD [

35]. These findings support the present results, which showed increased activation of the AD, PM, and PD across all three internal rotation exercises, along with increased IS thickness during the Lift Off and Prone Wiper.

Significant differences were also found in PICR across the three exercises. PICR increased during the Lift Off and Prone Wiper, whereas it decreased during the Belly Press. Variations in PICR during joint movement reflect shifts in the joint’s rotational center, and minimizing these shifts is essential for maintaining stable and normal joint mechanics [

3]. During shoulder movement, the RC plays a key role in centering the humeral head within the glenoid fossa and generating compressive forces that help stabilize the joint’s center of rotation [

11]. A previous study reported that the force couple generated by the RC muscles constrains the humeral head’s position of PICR to within ±1 mm relative to the glenoid fossa [

26]. Furthermore, another study demonstrated that minimizing PICR deviations through activation of the IS enabled the deltoid muscle to produce high torque in a stable manner, thereby facilitating normal external rotation of the shoulder [

25]. In this study, the SSC thickness increased across all exercises, with the greatest increase observed during the Belly Press. In contrast, the IS thickness decreased only during role in preventing functional disorders such as impingement syndrome by centering the humeral head and limiting its forward and upward translation during shoulder movement [

37,38]. Depending on shoulder posture, the IS contributes to posterior the Belly Press, while it increased with the other exercises. The SSC plays a critical shoulder stability by reinforcing posterior structures and preventing humeral head subluxation during internal rotation [

37]. It is hypothesized that the increased activity of the SSC – functioning both as a stabilizer and a primary mover in internal rotation – combined with reduced IS activity, its antagonist, enabled the AD and PM to generate torque more efficiently and with greater stability during the Belly Press. Consequently, a reduction in PICR distance was observed during this exercise, as confirmed by radiographic imaging – contrasting with the increases observed during the other exercises.

This study has some limitations. First, all participants were healthy adults, which limits the generalizability of the findings to clinical populations with shoulder pathologies. Future research should include individuals presenting with shoulder dysfunction to determine whether the observed neuromuscular responses are consistent in symptomatic populations. Second, the relatively small sample size may reduce the statistical power and restrict the external validity of the findings. Studies with larger and more diverse samples are needed to validate and extend these results. Finally, the cross-sectional design of the study only allowed for the assessment of immediate, short-term effects. As such, it remains unclear whether the observed changes in muscle activity and PICR are sustained over time. Longitudinal studies are warranted to investigate the long-term efficacy and clinical relevance of these exercises in both healthy individuals and patient populations.

5. Conclusions

This study investigated which of three shoulder internal rotation exercises most selectively activates the SSC. Among the exercises examined, the Belly Press uniquely resulted in a significant increase in SSC thickness, a concurrent decrease in IS thickness, and a reduction in the PICR. Our results suggest that the Belly Press is the most effective of the three exercises in selectively activates the SSC while enhancing joint stability through minimized PICR distance. These findings may assist clinicians in designing more effective exercise programs.

Author Contributions

Conceptualization, D.K.; methodology, D.K.; software, D.K.; validation, D.K. and S.P.; formal analysis, D.K.; investigation, D.K.; resources, D.K.; data curation, D.K.; writing—original draft preparation, D.K.; writing—review and editing, D.K. and S.P.; visualization, D.K. and S.P.; supervision, S.P.; project administration, S.P.; funding acquisition, S.P. All authors have read and agreed to the published version of the manuscript.

Funding

This research was supported by Basic Science Research Program through the National Research Foundation of Korea (RS-2021-NR060125) funded by the Ministry of Education (2025).

Institutional Review Board Statement

The study was conducted in accordance with the Declaration of Helsinki, and approved by the Institutional Review Board of Daegu University (IRB Number: 1040621-201901-HR-009-02) for studies involving humans.

Informed Consent Statement

Informed consent was obtained from all subjects involved in the study.

Data Availability Statement

All data related to this study are included in the article.

Acknowledgments

We thank our colleagues and the reviewers who provided constructive criticism on drafts of this essay.

Conflicts of Interest

The authors declare no conflict of interest.

References

- Malanga, G.A.; Jenp, Y.N.; Growney, E.S.; An, K.N. EMG analysis of shoulder positioning in testing and strengthening the supraspinatus. Med Sci sports Exerc 1996, 28, 661–664. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Reinold, M.M.; Escamilla, R.F.; Wilk, K.E. Current concepts in the scientific and clinical rationale behind exercises for glenohumeral and scapulothoracic musculature. J Orthop Sports Phys Ther 2009, 39, 105–117. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Sahrmann, S.A. Diagnosis and treatment of movement impairment syndromes; Mosby:, St. Louis, USA, 2002; pp. 215–216, 12-13.

- Ginn, K.A.; Reed, D.; Jones, C.; Downes, A.; Cathers, I.; Halaki, M. Is subscapularis recruited in a similar manner during shoulder internal rotation exercises and belly press and lift off tests? J Sci Med Sport 2017, 20, 566–571. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Wattanaprakornkul, D.; Cathers, I.; Halaki, M.; Ginn, K.A. The rotator cuff muscles have a direction specific recruitment pattern during shoulder flexion and extension exercises. J Sci Med Sport 2011, 14, 376–382. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Keller, R.A.; De Giacomo, A.F.; Neumann, J.A.; Limpisvasti, O.; Tibone, J.E. Glenohumeral Internal Rotation Deficit and Risk of Upper Extremity Injury in Overhead Athletes: A Meta-Analysis and Systematic Review. Sports health 2018, 10, 125–132. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Edelson, G.; Teitz, C. Internal impingement in the shoulder. J Shoulder Elbow Surg 2000, 9, 308–315. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Burkhart, S.S.; Morgan, C.D.; Kibler, W.B. The disabled throwing shoulder: spectrum of pathology Part I: pathoanatomy and biomechanics. Arthroscopy 2003, 19, 404–420. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Crockett, H.C.; Gross, L.B.; Wilk, K.E.; Schwartz, M.L.; Reed, J.; O'Mara, J.; Reilly, M.T.; Dugas, J.R.; Meister, K.; Lyman, S.; et al. Osseous adaptation and range of motion at the glenohumeral joint in professional baseball pitchers. Am J Sports Med 2002, 30, 20–26. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Drakos, M.C.; Rudzki, J.R.; Allen, A.A.; Potter, H.G.; Altchek, D.W. Internal impingement of the shoulder in the overhead athlete. J Bone Joint Surg Am 2009, 91, 2719–2728. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Myers, J.B.; Laudner, K.G.; Pasquale, M.R.; Bradley, J.P.; Lephart, S.M. Glenohumeral range of motion deficits and posterior shoulder tightness in throwers with pathologic internal impingement. The American journal of sports medicine 2006, 34, 385–391. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Jobe, F.W.; Kvitne, R.S.; Giangarra, C.E. Shoulder pain in the overhand or throwing athlete. The relationship of anterior instability and rotator cuff impingement. Orthop Rev 1989, 18, 963–975. [Google Scholar]

- Paley, K.J.; Jobe, F.W.; Pink, M.M.; Kvitne, R.S.; ElAttrache, N.S. Arthroscopic findings in the overhand throwing athlete: evidence for posterior internal impingement of the rotator cuff. Arthroscopy 2000, 16, 35–40. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Christensen, B.H.; Andersen, K.S.; Rasmussen, S.; Andreasen, E.L.; Nielsen, L.M.; Jensen, S.L. Enhanced function and quality of life following 5 months of exercise therapy for patients with irreparable rotator cuff tears - an intervention study. BMC Musculoskelet Disord 2016, 17, 252. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Gerber, C.; Hersche, O.; Farron, A. Isolated rupture of the subscapularis tendon. J Bone Joint Surg Am 1996, 78, 1015–1023. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Gerber, C.; Krushell, R.J. Isolated rupture of the tendon of the subscapularis muscle. Clinical features in 16 cases. J Bone Joint Surg Br 1991, 73, 389–394. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Lee, B.G.; Cho, N.S.; Rhee, Y.G. Effect of two rehabilitation protocols on range of motion and healing rates after arthroscopic rotator cuff repair: aggressive versus limited early passive exercises. Arthroscopy 2012, 28, 34–42. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Sgroi, T.A.; Cilenti, M. Rotator cuff repair: post-operative rehabilitation concepts. Curr Rev Musculoskelet Med 2018, 11, 86–91. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Fritz, J.M.; Inawat, R.R.; Slavens, B.A.; McGuire, J.R.; Ziegler, D.W.; Tarima, S.S.; Grindel, S.I.; Harris, G.F. Assessment of Kinematics and Electromyography Following Arthroscopic Single-Tendon Rotator Cuff Repair. PM R 2017, 9, 464–476. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Micheroli, R.; Kyburz, D.; Ciurea, A.; Dubs, B.; Toniolo, M.; Bisig, S.P.; Tamborrini, G. Correlation of findings in clinical and high resolution ultrasonography examinations of the painful shoulder. J Ultrason 2015, 15, 29–44. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Smith, T.O.; Back, T.; Toms, A.P.; Hing, C.B. Diagnostic accuracy of ultrasound for rotator cuff tears in adults: a systematic review and meta-analysis. Clin Radiol 2011, 66, 1036–1048. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Kim, K.; Kim, H.G. Ultrasound Dimensions of the Rotator Cuff and Other Associated Structures in Korean Healthy Adults. J Korean Med Sci 2016, 31, 1472–1478. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Plomb-Holmes, C.; Clavert, P.; Kolo, F.; Tay, E.; Lädermann, A. An orthopaedic surgeon's guide to ultrasound imaging of the healthy, pathological and postoperative shoulder. Orthop Traumatol Surg Res 2018, 104, S219–s232. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Sahrmann, S.; Azevedo, D.C.; Dillen, L.V. Diagnosis and treatment of movement system impairment syndromes. Braz J Phys Ther 2017, 21, 391–399. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Kim, D.H.; Kim, T.H. Effect of axial shoulder external rotation exercise in side-lying using visual feedback on shoulder external rotators. J Phys Ther Sci 2017, 29, 1723–1725. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Park, J.S. Effects of strengthening exercise for lower trapezius and shoulder external rotators on glenohumeral kinematics and shoulder functions in patients with shoulder impingement syndrome. Dissertation, Yonsei University, Wonju, 2018.

- Cho, J.; Lee, K.; Kim, M.; Hahn, J.; Lee, W. The Effects of Double Oscillation Exercise Combined with Elastic Band Exercise on Scapular Stabilizing Muscle Strength and Thickness in Healthy Young Individuals: A Randomized Controlled Pilot Trial. J Sports Sci Med 2018, 17, 7–16. [Google Scholar] [PubMed]

- Ha, S.M.; Kwon, O.Y.; Cynn, H.S.; Lee, W.H.; Kim, S.J.; Park, K.N. Selective activation of the infraspinatus muscle. J Athl Train 2013, 48, 346–352. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Hislop, H.J.; Montgomery, J. Daniels and Worthingham's muscle testing: techniques of manual examination, 8th ed.; Saunders/Elsevier: St. Louis, USA, 2007; pp. 87–89. [Google Scholar]

- Lim, J.Y.; Lee, J.S.; Mun, B.M.; Kim, T.H. A comparison of trapezius muscle activities of different shoulder abduction angles and rotation conditions during prone horizontal abduction. J Phys Ther Sci 2015, 27, 97–100. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Escamilla, R.F.; Yamashiro, K.; Paulos, L.; Andrews, J.R. Shoulder muscle activity and function in common shoulder rehabilitation exercises. Sports Med 2009, 39, 663–685. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Giles, J.W.; Langohr, G.D.; Johnson, J.A.; Athwal, G.S. The rotator cuff muscles are antagonists after reverse total shoulder arthroplasty. J Shoulder Elbow Surg 2016, 25, 1592–1600. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Alizadehkhaiyat, O.; Hawkes, D.H.; Kemp, G.J.; Frostick, S.P. Electromyographic Analysis of Shoulder Girdle Muscles during Common Internal Rotation Exercises. Int J Sports Phys Ther 2015, 10, 645–654. [Google Scholar]

- Reinold, M.M.; Macrina, L.C.; Wilk, K.E.; Fleisig, G.S.; Dun, S.; Barrentine, S.W.; Ellerbusch, M.T.; Andrews, J.R. Electromyographic analysis of the supraspinatus and deltoid muscles during 3 common rehabilitation exercises. J Athl Train 2007, 42, 464–469. [Google Scholar] [PubMed]

- Kelly, B.T.; Kadrmas, W.R.; Speer, K.P. The manual muscle examination for rotator cuff strength. An electromyographic investigation. Am J Sports Med 1996, 24, 581–588. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Hess, S.A. Functional stability of the glenohumeral joint. Man Ther 2000, 5, 63–71. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Lippitt, S.; Matsen, F. Mechanisms of glenohumeral joint stability. Clin Orthop Relat Res 1993, 20–28. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

|

Disclaimer/Publisher’s Note: The statements, opinions and data contained in all publications are solely those of the individual author(s) and contributor(s) and not of MDPI and/or the editor(s). MDPI and/or the editor(s) disclaim responsibility for any injury to people or property resulting from any ideas, methods, instructions or products referred to in the content. |

© 2025 by the authors. Licensee MDPI, Basel, Switzerland. This article is an open access article distributed under the terms and conditions of the Creative Commons Attribution (CC BY) license (http://creativecommons.org/licenses/by/4.0/).