1. Introduction

The shoulder has a wide range of motion and is frequently used in daily activities. Because of this, it is especially prone to injury, with rotator cuff tears being one of the most commonly diagnosed conditions in orthopedic practice. The rotator cuff consists of four muscles: supraspinatus, infraspinatus, teres minor, and subscapularis. These muscles help keep the shoulder joint stable and allow it to move in many directions [

1]. These deep muscles organize active and passive shoulder movements. Superficial muscles such as the deltoid and trapezius provide secondary support which can contribute to functional movement patterns [

2,

3]. Rotator cuff injuries are mainly the result of repetitive use or trauma in the muscles which leads to pain and functional issues, mainly among athletes and older adults [

4,

5].

Physical therapy (PT) still remains a key component of conservative treatment of rotator cuff injuries. It helps to restore mobility and strength along with muscular coordination [

6]. However, there is a persistent challenge in PT, e.i. determining the optimal "dosage" of therapeutic exercise. It is essential to balance intensity, duration, and type of movement to encourage healing without overloading any tissues [

7,

8]. Rehabilitation procedures are normally generalized or guided by clinician experience, which may not be patient-specific variables like muscular imbalances or functional goals [

9]. Recent studies focus on rehabilitation programs to individual patients but data-driven personalization strategies still remain limited [

10,

11,

12]

Recent studies show that machine learning models, especially XGBoost (eXtreme Gradient Boosting), can help model muscle behavior and support clinical decisions [

13,

14,

15]. For example, advanced deep learning models have accurately identified rotator cuff tears from X-rays, showing how artificial intelligence (AI) can improve screening and diagnosis [

16]. Overall, inertial measurement unit (IMU) data combined with XGBoost, has also been used to assess patient recovery status after rotator cuff surgery by providing objective measures of rehabilitation progress [

11]. Additionally, recent studies have adapted machine learning to identify important clinical features predictive of outpatient rotator cuff tears, supporting early diagnosis and personalized care planning [

15].

XGBoost is a powerful ensemble learning algorithm based on gradient-boosted decision trees. It has shown promise in different kinds of medical domains. According to Chang et al. [

17] and Wang et al. [

18], their model was able to outperform logistic regression in predicting outcomes such as hemodialysis-related blood pressure and mortality in traumatic brain injury patients. Similarly, Inoue et al. [

19] used XGBoost to analyze spinal cord injury data with strong results. Lim et al. [

20] applied it to knee pain by combining physical and mental health factors. These studies show that XGBoost can also be reliably useful for modeling recovery in rotator cuff rehabilitation where patient data and progress can vary. XGBoost has also been applied to improve outpatient therapy. For instance, Zhang et al. [

21] used it to predict patient preferences with over 80% accuracy, while Yang [

22] employed it to forecast COVID-19 trends. These examples show how XGBoost can support personalized care by understanding muscle data and helping to create better rehabilitation plans for individuals with rotator cuff injuries.

Researchers have used XGBoost to predict joint movement from electromyography (EMG) signals. Lu et al. [

23] was able to achieve accurate joint angle predictions using simple EMG data, while Wang et al. [

24] showed that biases might affect walking patterns and highlighted the need for adaptive models. Garcia et al. [

25] stressed the importance of standard EMG recording methods for reliable and clinically useful machine learning. However, most studies are not run in real-time and mainly use data from healthy subjects, which may be a limitation in real clinical settings.

There are many other studies on gesture recognition and human-machine interaction which also focus on using EMG with AI. For example, Chen et al. [

26] used Random Forest and support vector machines (SVM) to accurately recognize gestures. Ahmed et al. [

27] reviewed over 150 studies and discovered trends such as combining different sensors and using personalized deep learning. Wang et al. [

28] prioritized the need for energy efficient and real-time EMG systems for rehabilitation. These studies support the goal of building smart and responsive tools for shoulder recovery training.

XGBoost has also been successful in helping doctors assess clinical risk and make decisions. Liu et al. [

29] used it to predict which trauma patients would need treatment for bleeding, using shapley additive exPlanations (SHAP) to explain the results. Sun et al. [

30] used it to estimate recovery times, showing how it can support patient care. These examples show the model’s value in creating data-driven rotator cuff rehabilitation plans. Anatomical and imaging studies might also help improve model accuracy by connecting body structure with function. According to the research, Kim et al. [

31] used MRI to study rotator cuff tears and mapped them to tendon anatomy which was useful for choosing model features. Lim et al. [

20] showed that imaging alone does not fully explain pain, which explains that it is important to include physical, mental, and social factors.

Building on these insights, Alaiti et al. [

32] used machine learning to find patients less likely to recover well after rotator cuff surgery. This highlights how predictive models can help tailor rehabilitation technique to each patient. Combined models such as Random Forest, AdaBoost, and XGBoost have been compared in the past and in this research. Outside of healthcare, they have been used to predict complex, changing data such as in space weather forecasting [

33]. Bentéjac et al. [

34] showed that XGBoost performs well in terms of accuracy and speed when tested across many datasets. Other studies have looked at how these models handle difficult tasks like working with unbalanced data and medical images. Rahman et al. [

35] and Deshmukh and Bhosle [

36] tested AdaBoost alongside other models like K-nearest neighbors (KNN), SVM and logistic regression, even with noisy or limited data. Azmi and Baliga [

37] summed up this research and explained how boosting models like XGBoost and AdaBoost manage the balance between bias and variance, making them strong tools for both clinical and complex data tasks.

Our study builds on these methods by combining mainly two fronts: predicting muscle activity using EMG data; and optimizing how rehabilitation time is spent during each session. Unlike past studies that focused on safe exercise levels [

12], X-ray diagnosis [

16], progress tracking [

11], or predicting tear risks [

15]; this study creates a personalized time plan for key shoulder movements within the typical allotted time for a PT session. The goal is to target surface-level muscles while reducing strain on deeper ones as sEMG signals are more reliable for superficial muscles.

The present research focuses on optimizing the allocation of time across four commonly prescribed arm movements within a 60-minute therapy session: scaption, external rotation, internal rotation, and external rotation at 90° abduction. These exercises are frequently used in clinical settings to engage both superficial and deep muscules [

38,

39]. sEMG sensors capture muscle activation data from the deltoid, trapezius, supraspinatus, infraspinatus, teres minor, and subscapularis, offering insights into muscle-specific engagement. As a continuation of a previous study [

40], we aim to build on existing knowledge and enhance shoulder rehabilitation efficiency by maximizing superficial muscle activity. Meanwhile, minimizing undue strain on deep stabilizers during early recovery stages should be maintained [

41,

42]. Accurate modeling of muscle activation patterns can improve treatment design and reduce reinjury risk [

43,

44]. Our study proposes a unique approach based on combination of powerful prediction models with a practical tool that helps plan exercise time. Instead of offering general advice or single diagnoses, this approach gives physical therapists a clear, data-backed logic to personalize rotator cuff rehabilitation for each patient.

2. Methodology

2.1. Data Collection

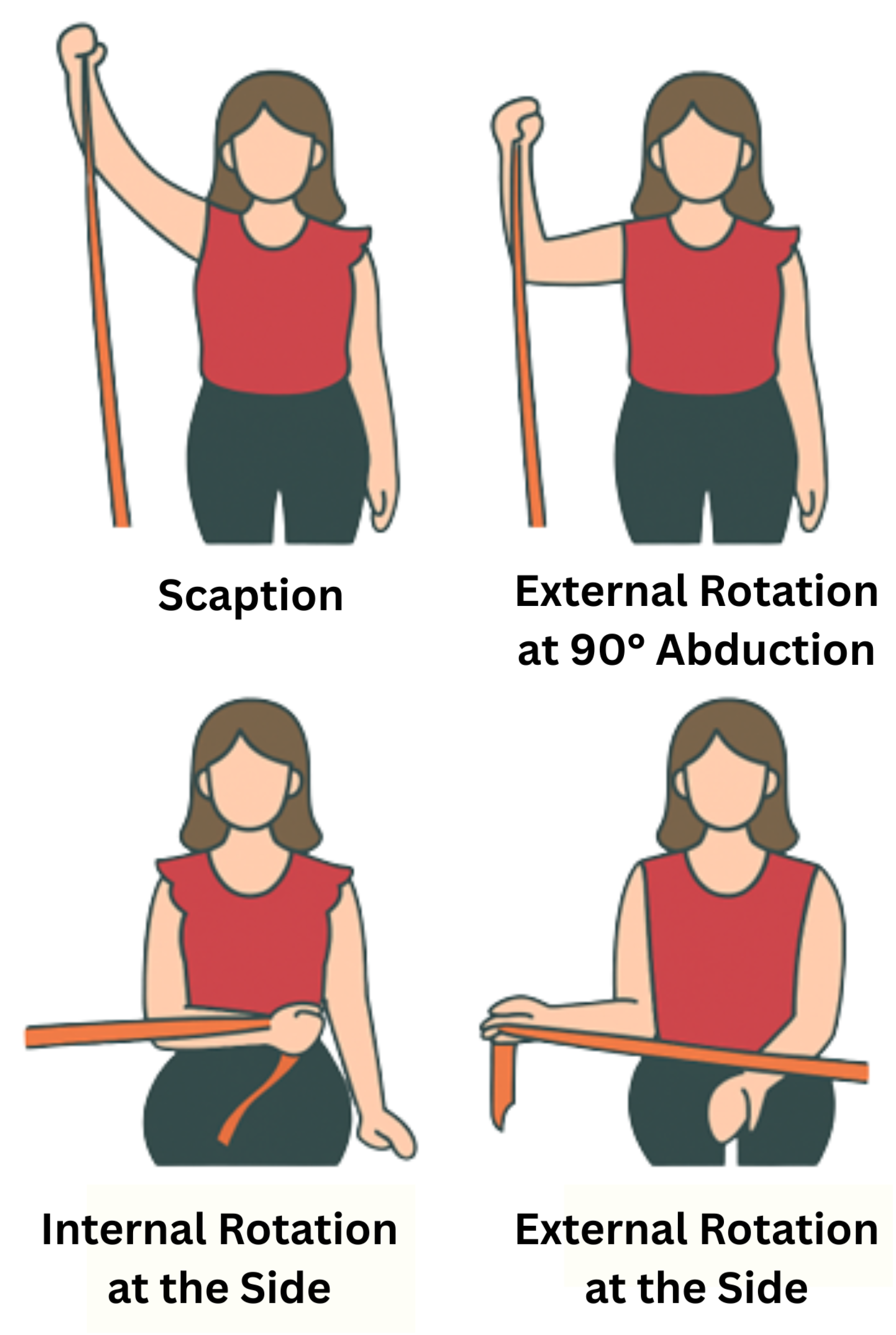

For this study, the right shoulders of eight healthy individuals were assessed while performing four muscle exercises: scaption, internal rotation at the side, external rotation at the side, and external rotation at 90 ° abduction, as shown in

Figure 1. Two datasets were collected for each subject to reduce potential biases. The subjects had a mean age of 20.2 ± 0.6 years (mean ± SD), and all of them had similar heights and anthropometric characteristics. Before starting the test, each subject filled out a consent form and a basic information form (see Ethical Statement). From the information sheet, it was found that all subjects were right-handed, which provides more consistency in the results between different subjects [

40].

EMG signals were recorded using surface electromyography (sEMG) sensors placed on six muscles critical to rotator cuff rehabilitation. These included three superficial muscles (medial deltoid, posterior deltoid, trapezius) and three deeper muscles (supraspinatus, infraspinatus, teres minor). The signals were collected as time-series recordings of muscle activation during each exercise. Table 1 summarizes the primary muscles activated during each exercise, classified by anatomical layer.

Table 1.

Primary Muscles Activated per Exercise with Anatomical Classification (S: Superficial, D: Deep).

Table 1.

Primary Muscles Activated per Exercise with Anatomical Classification (S: Superficial, D: Deep).

| Exercise |

Activated Muscles |

| Scaption |

Medial Deltoid (S)

Trapezius (S)

Supraspinatus (D)

Infraspinatus (D)

Teres Minor (D) |

| External Rotation at the Side |

Posterior Deltoid (S)

Infraspinatus (D)

Teres Minor (D) |

| Internal Rotation at the Side |

Medial Deltoid (S) |

| External Rotation at 90° Abduction |

Posterior Deltoid (S)

Supraspinatus (D)

Teres Minor (D) |

sEMG provides a non-invasive and practical method for real-time monitoring, but it is more accurate for superficial muscles. Its ability to measure deep muscle activity is limited due to signal cross-talk from adjacent muscles. In contrast, needle EMG requires inserting electrodes into the muscle which makes it invasive. Although needle EMG offers greater specificity, its invasiveness makes it impractical for dynamic rehabilitation tasks. Therefore, sEMG was selected for its clinical feasibility and ease of use.

2.2. Sample Size Justification

To address concerns about the small number of samples, the study incorporated careful signal preprocessing, followed the same labeling process for all samples, and tested the models thoroughly. These steps helped reduce variability, minimize signal noise, and made sure the machine learning models could work well for different people. As a pilot investigation, feasibility of using machine learning to personalize PT was explored. We leveraged the small sample size to allow close monitoring of each session, ensuring high-quality signal capture, and carefully evaluating the performance of our modeling pipeline. At this stage, the goal was to test whether the proposed approach is technically viable and worth scaling to a larger, more diverse population. Similar sample sizes have been used in early-stage EMG and neuromechanics research, particularly when developing or validating new analytical methods. We believe this focused approach provides a meaningful first step toward integrating adaptive therapy models into rehabilitation practice.

2.3. Data Preprocessing and Feature Extraction

The raw sEMG data was preprocessed by merging both datasets for each subject to better train the model. A new column named "Movement" was added in each subject’s dataset which contained categorical values for the muscle exercises. This column was encoded numerically using Label Encoding to ensure that the movement names could be fed into machine learning models as numerical features. Root Mean Square (RMS) values were computed for each muscle to summarize the activation signals. This was done using a sliding window approach, where each window had 250 samples. The RMS value for each window was then computed using the following equation:

where:

2.4. Machine Learning Model Selection and Cross-Subject Validation

To determine the most suitable model for predicting muscle activation, several regression algorithms were compared, including Support Vector Regression (SVR), K-Nearest Neighbors (KNN), AdaBoost Regressor, and XGBoost. These models were chosen because they strike a good balance between accuracy, interpretability, and responsiveness factors when working with a small dataset. More complex models like Random Forests and Neural Networks were excluded since they require more computing power and are more likely to overfit, especially with limited data. With just eight subjects, simpler models not only reduce the risk of overfitting but also make the approach more practical for real-world clinical use, where quick predictions and low computational cost really matter.

These models were tested using cross-subject validation to assess their accuracy and how well they could generalize. Instead of using a random train-test split, Leave-One-Subject-Out Cross-Validation was implemented to ensure robust generalization across subjects. For each iteration, data from eight subjects was used for training, and the remaining subject’s data was used for testing. This method simulates real-world conditions where the model must generalize to unseen patients. The RMS values served as the input features.

XGBoost builds a sequence of simple decision trees, with each tree learning from the mistakes of the previous one. This way, it not only achieves strong predictive performance but also controls overfitting. XGBRegressor was chosen for this study because it effectively captures non-linear interactions between muscle activations and exercise movements without compromising computational efficiency.

XGBoost builds an additive model in a forward stage-wise manner; it allows optimization of an arbitrary differentiable loss function. At each step

t, XGBoost adds a new function

to minimize the following regularized objective

:

where:

l is a differentiable loss function (such as mean squared error for regression),

is the prediction at iteration ,

is the function (a decision tree) added at iteration t,

is a regularization term to penalize model complexity, encouraging simpler trees.

The regularization term

is defined as:

where:

T is the number of leaves in the tree,

is the weight of leaf j,

and are regularization parameters.

In this framework, the predicted muscle activation value

for each observation

i is computed by summing the outputs of all decision trees up to iteration

t. At each boosting round, a new function

is fitted to the residual errors, updating the prediction as:

This iterative process minimizes the objective function

by reducing the prediction error step by step. After all trees are added, the final

is used to calculate the Mean Squared Error (MSE) and the coefficient of determination (

). For other methods,

is obtained differently: in Support Vector Regression (SVR), it is the output of the fitted hyperplane; in K-Nearest Neighbors (KNN), it is the mean of the target values of the

k nearest neighbors; and in AdaBoost, it is the weighted sum of predictions from multiple weak learners, usually shallow decision trees [

45]. All models, including SVR, KNN, and AdaBoost, were implemented and evaluated using scikit-learn’s standard library functions.

Model performance was evaluated using two common regression metrics: Mean Squared Error (MSE) and R-squared (

), measured across all test subjects. MSE measures the average of the squares of the errors between the predicted and true muscle activation values. Lower MSE values indicate more accurate predictions by penalizing large errors more heavily. It is defined as:

where:

represents the true activation value,

is the predicted value,

n is the total number of samples.

The

score quantifies the proportion of variance in the dependent variable that is predictable from the independent variables. It is calculated as:

where

is the mean of the observed data.

An value closer to 1 indicates a better fit between the model predictions and the actual outcomes, while a negative suggests the model performs worse than simply predicting the mean of the data.

Using both metrics (MSE and

) provides a balanced and rigorous evaluation of model quality. While MSE assesses the magnitude of prediction errors,

captures how well the model explains variance in the data. This dual-metric approach ensures that the selected model is both numerically precise and generalizable—critical qualities for clinical applications where both accuracy and interpretability are essential. This evaluation strategy is widely recommended in regression modeling practices [

46].

2.5. Time Allocation Optimization

After predicting muscle activations, the next step was to optimize how the 60-minute rehabilitation session should be divided among the different exercises. This duration was selected based on common clinical practice guidelines for outpatient PT, balancing sufficient therapeutic intensity with patient tolerance and scheduling feasibility. sEMG sensors primarily capture signals from superficial muscles more reliably than deep muscles; the goal was to increase the activation of superficial muscles compared to deep muscles, while keeping the time distribution balanced and practical for real-world use. The objective function was defined as:

where:

n corresponds to the four rehabilitation exercises evaluated: scaption, internal rotation at the side, external rotation at the side, and external rotation at 90° abduction,

represents the time allocated to exercise i,

and represent the predicted superficial and deep muscle activations for each exercise i, calculated as the average predicted RMS values of the three superficial muscles (medial deltoid, posterior deltoid, trapezius) and the three deep muscles (supraspinatus, infraspinatus, teres minor), respectively,

penalizes high variance in time distribution across exercises,

and are weights to control the emphasis on superficial versus deep muscles depending on rehabilitation goals.

Three different weighting strategies were evaluated:

Case 1: 70% superficial / 30% deep

Case 2: 50% superficial / 50% deep

Case 3: 30% superficial / 70% deep

To address the challenge of optimally distributing exercise time, a constrained nonlinear optimization approach was implemented using the trust-constr algorithm from Python’s scipy.optimize.minimize function. This derivative-based method combines interior-point trust region techniques with Sequential Quadratic Programming (SQP), making it a good fit for problems with both equality constraints and bounds. The goal was to maximize the weighted sum of predicted superficial muscle activations, while also minimizing deep muscle strain and reducing excessive variability in time allocation across exercises.

To ensure that the resulting plans were clinically practical and aligned with real-world rehabilitation protocols, two main constraints were applied. First, an equality constraint ensured that the total exercise time always added up to exactly 60 minutes. Second, bound constraints kept each individual exercise within a practical range of 5 to 30 minutes. The optimization process was initialized by assigning equal time to each exercise, and the solver consistently generated stable and interpretable time allocations under various superficial-to-deep muscle weighting scenarios. This enabled the study to test model robustness by examining how muscle group emphasis affected the optimized plans, supporting flexible, goal-driven rehabilitation strategies.

Additionally, the training time for each model was monitored using Python’s time module. The time was measured taking timestamps just before and after the training for each cross-validation fold. This helped to ensure which model was more efficient than the rest.

3. Results

3.1. Model Comparison and Selection

Table 2 summarizes the cross-subject validation results used to evaluate how well different regression models predict muscle activation from EMG features.

Table 2.

Performance comparison of regression models (mean ± — values reported).

Table 2.

Performance comparison of regression models (mean ± — values reported).

| Model |

Average MSE |

Average () |

Training Time (s) |

| |

() |

|

|

| SVR |

136.6163 |

0.7891 |

296 |

| KNN |

32.2439 |

0.7152 |

24 |

| AdaBoost |

6.6699 |

0.9234 |

185 |

| XGBoost |

15.0983 |

0.9875 |

23 |

3.1.1. Performance

Among all tested models, XGBoost demonstrated the most reliable and balanced predictive performance. It achieved the highest value (0.9875), indicating that it explained over 98% of the variance in muscle activation levels across different subjects. While AdaBoost produced the lowest average MSE (6.6699 ), its value (0.9234) was notably lower, suggesting it captured less of the overall activation dynamics.

Other models such as SVR (MSE: 136.6163 , : 0.7891) and KNN (MSE: 32.2439 , : 0.7152) underperformed on both metrics. These results highlight XGBoost’s strong ability to generalize across subjects and capture complex relationships within the EMG feature space.

3.1.2. Efficiency

In addition to predictive accuracy, training time was also considered as a practical performance factor. XGBoost stood out as the fastest, completing the full cross-subject evaluation in just 23 seconds. KNN came close at 24 seconds, though its predictive performance was significantly weaker. Despite achieving a slightly lower MSE, AdaBoost took much longer—185 seconds—to complete the same process. SVR was the slowest overall, requiring 296 seconds to train and evaluate. These results further support XGBoost as the most efficient and effective choice for this application.

The combination of high accuracy and low computation time makes XGBoost particularly well-suited for scalable, real-time rehabilitation systems. As a result, it was selected as the primary model for all subsequent optimization analyses.

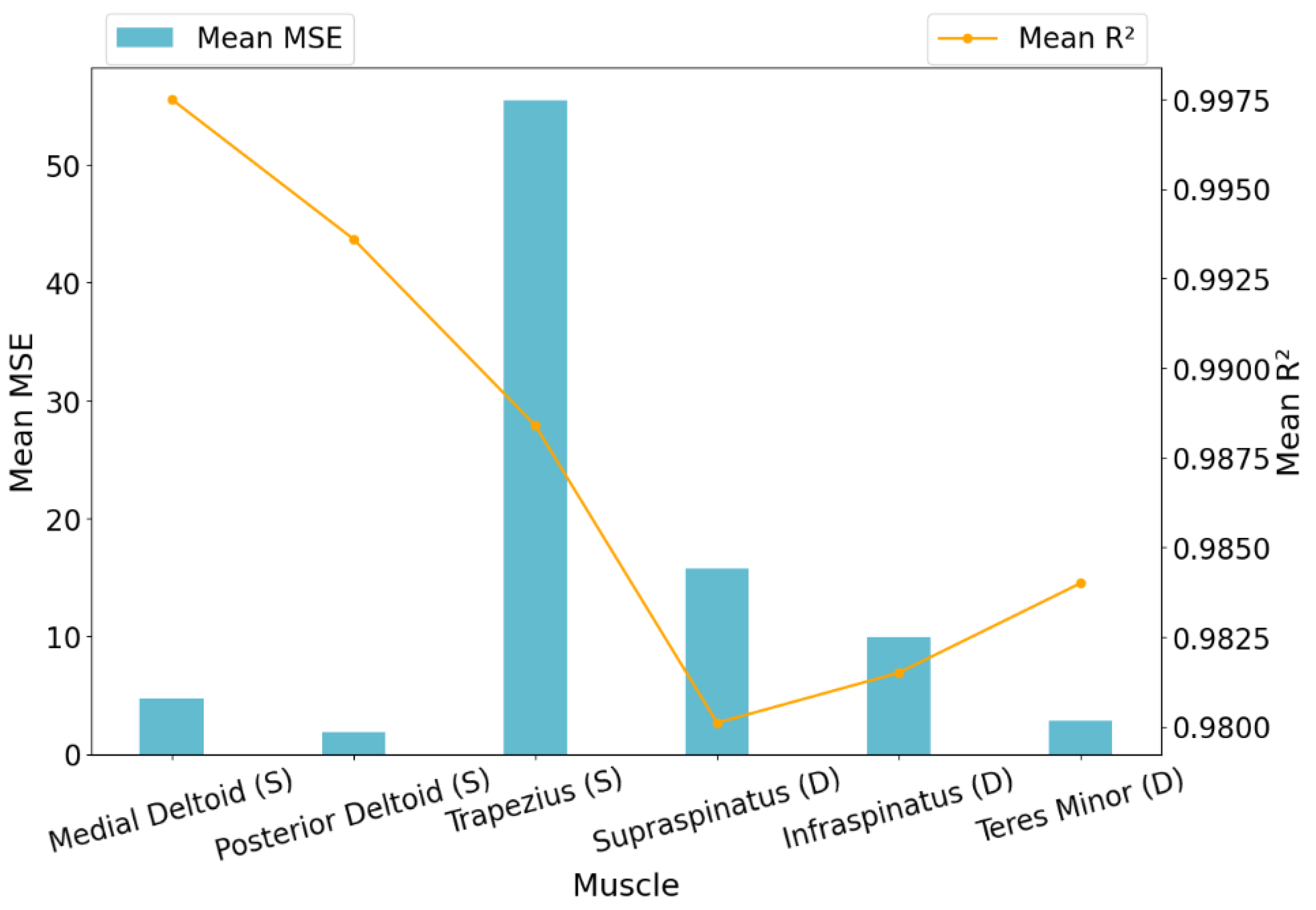

3.2. XGBoost Evaluation Across All Muscles

Having been selected as the final model, XGBoost’s predictive performance was analyzed in more detail. It achieved an average MSE of 15.0983

across all muscles and subjects, indicating strong overall accuracy. However, there was some variation in error across different muscles. The trapezius showed higher MSE values, suggesting more variability in its activation predictions, while muscles like the teres minor and medial deltoid were predicted with notably higher precision. Detailed results across individual muscles, based on cross-subject validation prior to optimization, are visualized in

Figure 2.

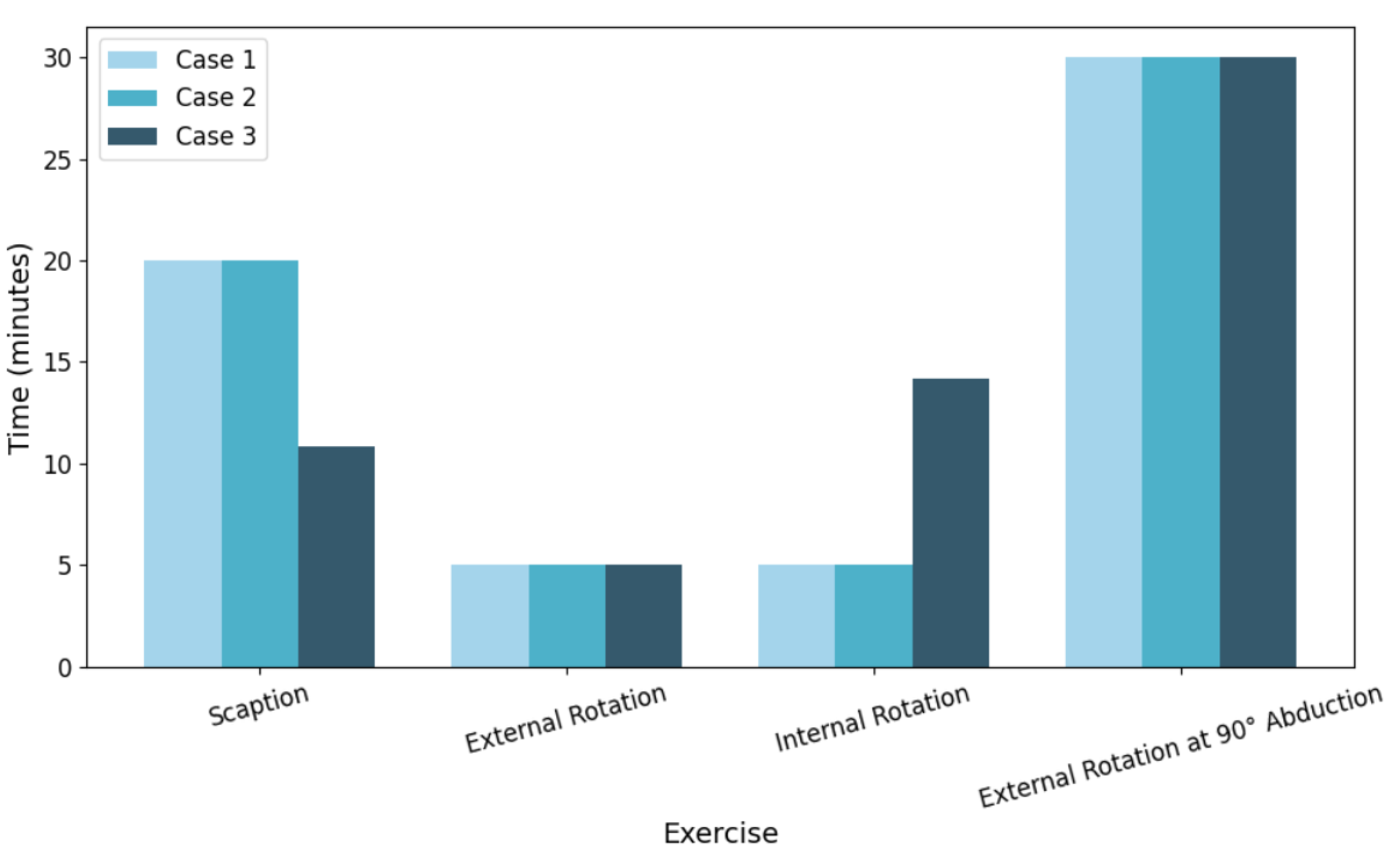

3.3. Optimized Time Allocation

Following the prediction of muscle activation levels, an optimization framework was applied to determine the ideal time allocation for a 60-minute rehabilitation session. The results of the optimized durations for each exercise under three different superficial-to-deep muscle weighting strategies are shown in

Figure 3.

3.3.1. Case 1: 70% Superficial / 30% Deep

In this case, the optimization prioritized the activation of superficial muscles. External rotation at 90° abduction (30.00 minutes) was allocated a significant portion of the session time followed by scaption (20.00 minutes), which contributed to both superficial and deep muscle engagement. Minimal time was assigned to internal and external rotation at the side (5.00 minutes each), reflecting their relatively lower superficial activation.

3.3.2. Case 2: 50% Superficial / 50% Deep

With equal weighting between superficial and deep muscles, the time allocation pattern remained consistent with Case 1. Scaption and external rotation at 90° abduction continued to receive the majority of the time (20.00 and 30.00 minutes respectively), indicating their balanced contribution to both muscle groups. This suggests that the model’s predictions are stable under moderate weighting changes.

3.3.3. Case 3: 30% Superficial / 70% Deep

When the priority was shifted towards deep muscle engagement, the time allocated to scaption was significantly reduced to 10.84 minutes. Instead, internal rotation at the side received increased attention with 14.16 minutes, as it is more effective at engaging deeper rotator cuff muscles. External rotation at 90° abduction remained fixed at the 30-minute cap due to its well-rounded activation profile.

Overall, the relatively minor shifts in optimized time allocations between different weighting strategies indicate that the machine learning model predictions and optimization process were robust. This suggests that the system can reliably generate therapy session plans even when rehabilitation priorities (superficial versus deep muscle focus) are adjusted.

4. Discussion

This study demonstrated that machine learning models trained on sEMG data can support more efficient PT planning for rotator cuff recovery. sEMG signals were collected from eight participants and analyzed using an XGBoost Regressor which demonstrated robust predictive capabilities. The model achieved an average MSE of 15.0983 and an R² value of 0.9875 which reflected its effectiveness in capturing the variations of muscle activation during a variety of rehabilitation exercises.

Analysis of the sEMG dataset showed specific muscle activation patterns associated with specific movements. Through the model’s prediction, a 60-minute rehabilitation session was designed using an optimization framework. The study noted that external rotation at 90° abduction consistently received the maximum allowable time allocation (30 minutes) across all weighting strategies and highlighted its general efficiency. When the framework prioritized superficial muscle activity, scaption complemented abduction by receiving additional time allocation as a supportive movement, but it was not able to exceed abduction in significance. On the other hand, internal rotation at the side was chosen more often when the focus was on engaging deeper muscles. The small changes in time across different plans show that the model is both reliable and flexible, able to support different rehabilitation goals without losing consistency.

Three optimization cases were evaluated to simulate varying clinical priorities. In all scenarios, external rotation at 90° abduction consistently received the maximum time allocation, reinforcing its effectiveness as a core rehabilitation movement. When superficial muscles were prioritized (70/30), scaption raised as a key complementary exercise, whearas the deep muscle focused case (30/70) emphasized on internal rotation at the side. The consistent time distribution across different cases shows that the model can adjust well to different therapy goals.

In addition to evaluating the primary model, a comparative analysis was conducted using other regression algorithms such as Support Vector Regression (SVR), K-Nearest Neighbors (KNN), and AdaBoost Regressor. The XGBoost model achieved the highest score (0.9875) by showing a strong ability to explain the variance in muscle activation patterns and by also maintaining a relatively low Mean Squared Error (MSE) of 15.0983 . Although AdaBoost achieved a lower MSE of 6.6699 , its value (0.9234) was clearly lower than that of XGBoost. SVR and KNN performed significantly worse, with lower values (0.7891 and 0.7152, respectively) and higher MSE values. These results supported the selection of XGBoost as the main modeling framework due to its strong predictive accuracy and ability to generalize across different subjects.

In summary, this study shows that combining sEMG-based machine learning with optimization techniques is a promising and practical approach to support data-driven planning of physical therapy. While there are still some limitations, the results provide a great starting point for developing more personalized rehabilitation practices based on real clinical data.

5. Clinical Implications and Recommendations

Although the results of this study are encouraging, several limitations should be also be kept in mind. One of the major limitations among them is the small sample size (only eight participants) which restricts the generalizability of the findings to the wider population. Also, the participant group lacked diversity in terms of demographics and physical attributes, which could introduce bias into the model’s performance and limit its applicability across various clinical populations.

To ensure strong internal validity, the researchers implemented overall signal preprocessing, accurate labeling and model validation techniques. These methodological steps helped minimize noise and improved the reliability of the results within the sample studied.

As a proof of concept, this work highlights the promise of using surface EMG (sEMG) data in combination with machine learning to develop more effective and individualized physical therapy process. Future studies should address the current limitations by incorporating measurement techniques like fine-wire EMG or ultrasound imaging to capture deeper muscle activity more accurately. Increasing the sample size and ensuring diversity in greater participants in real-world clinical settings will be crucial for validating the methodology and advancing toward more personalized rehabilitation strategies.

To enable clinical application, the system could be developed into a user-friendly interface that integrates smoothly with wearable EMG devices and existing rehabilitation platforms. Such interfaces would allow physical therapists to monitor muscle activity in real time and adjust treatment plans based on personalized feedback. For the system to be practical and scalable in real-world settings, it must also be compatible with current clinical tools, regulatory requirements and extensive training for healthcare providers.

6. Conclusions

This study successfully demonstrated the efficiency of using machine learning approach, specifically XGBoost, to optimize physical therapy dosage for rotator cuff rehabilitation based on sEMG data. The model achieved high predictive accuracy (R² = 0.9875; MSE = 15.0983 ), confirming its ability to predict muscle activation patterns across four commonly used shoulder movements. The optimization framework planned a 60-minute therapy session, consistently giving the most time to external rotation at 90° abduction, followed by scaption which highlighted their importance in rehabilitation. The similar results across different muscle focus settings show that the system is reliable. This data-driven approach offers a solid base for creating personalized rehabilitation plans that can improve outcomes and move away from one-size-fits-all treatments.

Alongside XGBoost, a range of other machine learning regression models like K-Nearest Neighbors (KNN), Support Vector Regression (SVR), and AdaBoost were also analyzed for their predictive performance. Although AdaBoost yielded the lowest Mean Squared Error (6.6699 ), its R² score (0.9234) lagged behind that of XGBoost. Both SVR and KNN performed significantly lower, showing lower R² values (0.7891 and 0.7152, respectively) and experiencing higher computational demands or error rates. XGBoost proved to be the most effective option which offered a good balance between accuracy and efficiency. These results highlighted the importance of choosing the right model in clinical machine learning and shows XGBoost’s ability to handle complex muscle optimization tasks.

This research demonstrated that optimizing exercise dosage through EMG-guided machine learning models offers a promising result on rotator cuff rehabilitation. Across eight subjects that were tested, high model performance confirms that EMG signals can predict muscle activation across multiple arm movements.

An optimization framework was developed to allocate a fixed 60-minute therapy session across key exercises. Results consistently focused external rotation at 90° abduction with time allocations remaining stable across various superficial-to-deep muscle weighting strategies and highlighted the robustness of the approach. This work builds on previous efforts by offering a quantitative, individualized method for exercise allocation and moving toward new rehabilitation protocols.

This research provides a quantitative dosage allocation on how time should be optimally distributed among exercises during the therapy session to get the best outcome. This study introduces a data-driven optimization framework using machine learning technique like (XGBoost) that allocates a fixed 60-minute PT session across four commonly prescribed movements. It blends machine learning technique "XGBoost" to forecast EMG activity so that it can be effectively used by physical therapists and practitioners for facilitating scalable and adaptive therapy planning.

Funding

This research did not receive any specific grant from funding agencies in the public, commercial, or not-for-profit sectors.

Author Contributions: A. MajidiRad

: Writing – original draft, Writing – review & editing, Methodology, Investigation, Data curation, Validation, Conceptualization. I. Azam: Writing – original draft, Writing – review & editing, Investigation, Software, Formal analysis, Data curation, Methodology, Validation. J. Adhikary: Writing – original draft, Writing – review & editing, Investigation, Software, Formal analysis, Data curation, Methodology, Validation. M. Damircheli: Writing – review & editing, Supervision, Validation.

Institutional Review Board Statement

The data used for this project were obtained from tests conducted under IRB application #1796088-2, approved on August 27, 2021, by the University of North Florida Institutional Review Board. Informed consent was obtained from all healthy participants prior to their involvement.

Conflicts of Interest

The authors declare that they have no known competing financial interests or personal relationships that could have appeared to influence the work reported in this paper.

References

- Jeanfavre, M.; Husted, S.; Leff, G. Exercise therapy in the non-operative treatment of full-thickness rotator cuff tears: a systematic review. Int. J. Sports Phys. Ther. 2018, 13, 335–344. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Edwards, P.; Ebert, J.; Joss, B.; Bhabra, G.; Ackland, T.; Wang, A. Exercise rehabilitation in the non-operative management of rotator cuff tears: a review of the literature. Int. J. Sports Phys. Ther. 2016, 11, 279–289. [Google Scholar]

- Weiss, L.J.; Wang, D.; Hendel, M.; Buzzerio, P.; Rodeo, S.A. Management of rotator cuff injuries in the elite athlete. Curr. Rev. Musculoskelet. Med. 2018, 11, 102–112. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Vakanski, A.; Ferguson, J.M.; Lee, S. Metrics for performance evaluation of patient exercises during physical therapy. Int. J. Phys. Med. Rehabil. 2017, 5, 403–409. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Burns, D.; Boyer, P.; Razmjou, H.; Richards, R.; Whyne, C. Adherence patterns and dose response of physiotherapy for rotator cuff pathology: Longitudinal cohort study. JMIR Rehabil. Assist. Technol. 2021, 8, e21374. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Cooke, E.V.; Mares, K.; Clark, A.; Tallis, R.C.; Pomeroy, V.M. The effects of increased dose of exercise-based therapies to enhance motor recovery after stroke: a systematic review and meta-analysis. BMC Medicine 2010, 8, 1–13. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Jiang, Y.; Chen, C.; Zhang, X.; Chen, C.; Zhou, Y.; Ni, G.; Lemos, S. Shoulder muscle activation pattern recognition based on sEMG and machine learning algorithms. Comput. Methods Programs Biomed. 2020, 197, 105721. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Sassi, M.; Carnevale, A.; Mancuso, M.; Schena, E.; Pecchia, L.; Longo, U.G. Classification of shoulder rehabilitation exercises by using wearable systems and machine learning algorithms. IEEE Sensors Journal 2024, 24, 1234–1245. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Sadikoglu, F.; Kavalcioglu, C.; Dagman, B. Electromyogram (EMG) signal detection, classification of EMG signals and diagnosis of neuropathy muscle disease. Procedia Computer Science 2017, 120, 422–429. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Belli, I.; Joshi, S.; Prendergast, J.M.; Beck, I.; Santina, C.D.; Peternel, L.; Seth, A. Does enforcing glenohumeral joint stability matter? A new rapid muscle redundancy solver highlights the importance of non-superficial shoulder muscles. PLOS ONE 2023, 18, e0295003. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Xu, K.; Feng, H.; He, G.; Li, M. Research on rehabilitation assessment methods for patients after rotator cuff surgery based on attitude sensors and XGBoost algorithm. In Proceedings of the 2024 3rd International Conference on Computing, Communication, Zhuhai, China, 2024, Perception and Quantum Technology (CCPQT); pp. 312–316.

- Smith TO, Chester R, C. A.D.S. A systematic review of electromyography studies in normal shoulders to inform postoperative rehabilitation following rotator cuff repair. Shoulder & Elbow 2012, 4, 127–135. [Google Scholar]

- Reinold, D.W.; Wilk, K.E.; Fleisig, M.R.; Cain, R.E.; Dugas, T.C.; Andrews, J.R. Electromyographic analysis of the rotator cuff and deltoid musculature during common shoulder external rotation exercises. Journal of Orthopaedic & Sports Physical Therapy 2004, 34, 385–394. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Ashraf, H.; Waris, A.; Gilani, S.O.; et al. . Optimizing the performance of convolutional neural networks for enhanced gesture recognition using sEMG. Scientific Reports 2024, 14. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Li C, Zhang X, Z. Z.C.W.W.Y. Machine learning model successfully identifies important clinical features for predicting outpatients with rotator cuff tears. Knee Surgery, Sports Traumatology, Arthroscopy 2023, 31, 2615–2623. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Kim J, Kim Y, C. J.e.a. Ruling out rotator cuff tear in shoulder radiograph series using deep learning: redefining the role of conventional radiograph. Korean Journal of Radiology 2021, 22, 2023–2032. [Google Scholar]

- Chang, H.H.; Huang, Y.F.; Yu, T.H.; Lee, Y.J.; Wang, C.J. Predictive modeling of blood pressure during hemodialysis: A comparison of linear model, random forest, support vector regression, XGBoost, LASSO regression and ensemble method. PLoS ONE 2021, 16, e0261160. [Google Scholar]

- Wang, R.; Wang, L.; Zhang, J.; He, M.; Xu, J. XGBoost machine learning algorithm performed better than regression models in predicting mortality of moderate-to-severe traumatic brain injury. World Neurosurg. 2022, 163, e617–e622. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Inoue, T.; Ichikawa, D.; Ueno, T.; Cheong, M.; Inoue, T.; Whetstone, W.D.; Tominaga, T. XGBoost, a machine learning method, predicts neurological recovery in patients with cervical spinal cord injury. Neurotrauma Rep. 2020, 1, 8–16. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Lim, Y.; Kim, H.; Park, J. Factors associated with predicting knee pain using knee X-ray and personal factors: A multivariate logistic regression and XGBoost model analysis from the nationwide Korean database (KNHANES). Int. J. Environ. Res. Public Health 2021, 18, 2564. [Google Scholar]

- Zhang, X.; Zhu, H.; Zhang, Y.; Chen, L. Prediction of outpatient rehabilitation patient preferences and optimization of graded diagnosis and treatment based on XGBoost machine learning algorithm. J. Healthc. Eng. 2022, 2022, 1–11. [Google Scholar]

- Yang, Z. Application of a data-driven XGBoost model for the prediction of COVID-19 in the USA: A time-series study. IEEE Access 2020, 8, 115512–115520. [Google Scholar]

- Lu, Z.; Chen, S.; Yang, J.; Liu, C.; Zhao, H. Prediction of lower limb joint angles from surface electromyography using XGBoost. Expert Systems with Applications 2025, 264, 125930. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Wang, B.; Liu, Y.; Lin, Y.; Zhang, H. Estimating gait parameters from sEMG signals using machine learning techniques under different power capacity of muscle. Front. Neurorobot. 2021, 15, 1–10. [Google Scholar]

- Garcia, M.C.; Vieira, T.M.M. Surface electromyography: Why, when and how to use it. Rev. Andal. Med. Deporte 2011, 4, 17–28. [Google Scholar]

- Chen, Y.; Qiu, L.; Sun, B. Development of machine learning models to determine hand gestures using EMG signals. IEEE Trans. Instrum. Meas. 2020, 69, 5761–5770. [Google Scholar]

- Ahmed, I.; Saeed, F.; Wang, H. Surface electromyography and artificial intelligence for human activity recognition—A systematic review on methods, emerging trends, applications, challenges, and future implementation. IEEE Rev. Biomed. Eng. 2022, 15, 211–230. [Google Scholar]

- Wang, L.; Wu, T.; Li, X.; Zhang, M. Surface electromyography and artificial intelligence in rehabilitation: Current state and future directions. IEEE Trans. Neural Syst. Rehabil. Eng. 2021, 29, 2385–2396. [Google Scholar]

- Liu, Z.; Song, M.; Zhang, S.; Xu, J.; Wu, Y. Enhancing trauma care: A machine learning approach with XGBoost for predicting urgent hemorrhage interventions using NTDB data. J. Trauma Acute Care Surg. 2021, 90, 590–597. [Google Scholar]

- Sun, T.; Zhang, Y.; Liu, J. Survival regression with accelerated failure time model in XGBoost. IEEE Access 2021, 9, 10317–10325. [Google Scholar]

- Kim, K.; Lee, J.; Choi, M. Relation of superficial and deep layers of delaminated rotator cuff tear to supraspinatus and infraspinatus insertions. J. Shoulder Elbow Surg. 2019, 28, 1938–1946. [Google Scholar]

- Alaiti, R.K.; et al. Using machine learning to predict nonachievement of clinically significant outcomes after rotator cuff repair. Orthop. J. Sports Med. 2023, 11, 23259671231206180. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Natras, R.; Soja, B.; Schmidt, M. Ensemble machine learning of random forest, AdaBoost and XGBoost for vertical total electron content forecasting. Remote Sens. 2022, 14, 3547. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Bentéjac, C.; Csörgo, A.; Martínez-Muñoz, G. A comparative analysis of XGBoost. arXiv 2019, arXiv:1911.01914. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Rahman, H.A.A.; et al. Comparisons of AdaBoost, KNN, SVM and logistic regression in classification of imbalanced dataset. In Proceedings of the Proc. 1st Int. Conf. Soft Comput. Data Sci. (SCDS 2015), Putrajaya, Malaysia 2015. [Google Scholar]

- Deshmukh, J.; Bhosle, U. A study of mammogram classification using AdaBoost with decision tree, KNN, SVM and hybrid SVM-KNN as component classifiers. Int. Res. J. Eng. Technol. (IRJET) 2018, 9, 548–557. [Google Scholar]

- Azmi, S.S.; Baliga, S. An overview of boosting decision tree algorithms utilizing AdaBoost and XGBoost boosting strategies. Int. Res. J. Eng. Technol. (IRJET) 2020, 7, 6867–6870. [Google Scholar]

- Thakkar, H.K.; Liao, W.; Wu, C.Y.; et al. . Predicting clinically significant motor function improvement after contemporary task-oriented interventions using machine learning approaches. J. NeuroEngineering Rehabil. 2020, 17, 131. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Bai, A.; Song, H.; Wu, Y.; Dong, S.; Feng, G.; Jin, H. Sliding-window CNN + channel-time attention transformer network trained with inertial measurement units and surface electromyography data for the prediction of muscle activation and motion dynamics leveraging IMU-only wearables for home-based shoulder rehabilitation. Sensors 2025, 25, 1275. [Google Scholar] [PubMed]

- Mitchell, A.; MajidiRad, A.; Pujalte, G. A CASE STUDY ON ACTIVATION LEVEL OF ROTATOR CUFF MUSCLES USING ELECTROMYOGRAPHY AND ASSOCIATED MUSCLE FORCES. Frontiers in Biomedical Devices 2023, 86731. [Google Scholar]

- Wells, S.N.; et al. . A literature review of studies evaluating rotator cuff activation during early rehabilitation exercises for post-op rotator cuff repair. Journal of Exercise Physiology Online 2016, 19. [Google Scholar]

- Mabrouk, O.M.; Hady, D.A.A.; El-Hafeez, T.A. Machine learning insights into scapular stabilization for alleviating shoulder pain in college students. Scientific Reports 2024, 14, 28430. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Yousif, H.A.; Zakaria, A.; Rahim, N.A.; Salleh, A.F.B.; Mahmood, M.; Alfarhan, K.A.; Hussain, M.K. Assessment of muscles fatigue based on surface EMG signals using machine learning and statistical approaches: A review. IOP Conf. Ser. Mater. Sci. Eng. 2019, 705, 012010. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Hajian, G. Generalized Force Estimation using Machine Learning and Deep Learning with EMG and Motion Data. PhD thesis, Queen’s Univ., Ontario, Canada, 2020. Order No. 28387874.

- Pedregosa, F.; Varoquaux, G.; Gramfort, A.; Michel, V.; Thirion, B.; Grisel, O.; Blondel, M.; Prettenhofer, P.; Weiss, R.; Dubourg, V.; et al. Scikit-learn: Machine Learning in Python. Journal of Machine Learning Research 2011, 12, 2825–2830. [Google Scholar]

- Chicco, D.; Jurman, G. The advantages of the Matthews correlation coefficient (MCC) over F1 score and accuracy in binary classification evaluation. BMC Genomics 2020, 21, 1–13. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

|

Disclaimer/Publisher’s Note: The statements, opinions and data contained in all publications are solely those of the individual author(s) and contributor(s) and not of MDPI and/or the editor(s). MDPI and/or the editor(s) disclaim responsibility for any injury to people or property resulting from any ideas, methods, instructions or products referred to in the content. |

© 2025 by the authors. Licensee MDPI, Basel, Switzerland. This article is an open access article distributed under the terms and conditions of the Creative Commons Attribution (CC BY) license (http://creativecommons.org/licenses/by/4.0/).