1. Introduction

Predation and competition play a major role in animal interactions. Competition occurs when individuals, belonging to different species (often closely related), utilize the same environmental resources which are limited. Competition for food resources may lead to character displacement (morphological or behavioural differentiation) among competing species, and this, in turn, may result in the niche segregation (KREBS 2009). Competing species may segregate their food niches in three major ways: trophic (what they eat), spatial (when they forage) and temporal (when they forage).

Closely related species may co-exist in the same habitat if their niches do not overlap to a large extend. This overlap decreases with increasing environmental variability, and/or with increasing diffuse competition (increasing number of competing species). A maximal tolerable niche overlap should, therefore, vary inversely with the intensity of competition (PIANKA 1974). Lizards living in arid environments constitute good study objects to test niche differentiation and similar related issues of interspecific competition (PIANKA 1969, 1974; HUEY ET AL. 1974; TOFT 1985; WINEMILLER, PIANKA 1990; SHENBROT ET AL. 1991; COOPER, WHITING 1999; BAKER ET AL. 2021). Due to the habitat heterogeneity and long isolation, some arid regions, like these in Namibia, support also a high level of lizard endemicity, especially skinks and geckos (MURRAY et al. 2016).

The family Scincidae is the largest and most diverse lizard family represented by more than 1685 species, 158 genera and seven subfamilies (UETZ et al. 2020). One of the subfamily Mabuyinae consists one of the most speciose lizard genus – Trachylepis (previously Mabuya), with 87 species. Most of them (n=84) are confined to the Afrotropical Region (UETZ et al. 2020). In southern Africa, the genus consists 23 species (ALEXANDER & MARAIS 2017). HUEY & PIANKA (1977) studied diet of T.spilogaster, T.occidentalis, in the southern Kalahari. However, no quantitative data on food consumption are available for T.acutilabris, T.sulcata and T.hoeschi (BRANCH 1992, ALEXANDER & MARAIS 2017).

I set out to investigate whether the feeding niches differ for five common Trachylepis species living in arid regions of Namibia: T.spilogaster (Kalahari tree skink), T. acutilabris (wedge-snouted skink), T.sulcata (western rock skin), T.hoeschi (Hoesch’s skink), and T. occidentalis (western-tree-striped skink) (ALEXANDER & MARAIS 2017). Since these species are very similar and often occur sympatrically (ALEXANDER & MARAIS 2017), I hypothesize that there may be differences between the feeding niches of these selected species of the genus Trachylepis. I address this hypothesis by analysing the composition of their diet.

2. Materials and Methods

I studied food composition of stomachs dissected from museum specimens deposited in the National Museum of Namibia in Windhoek (

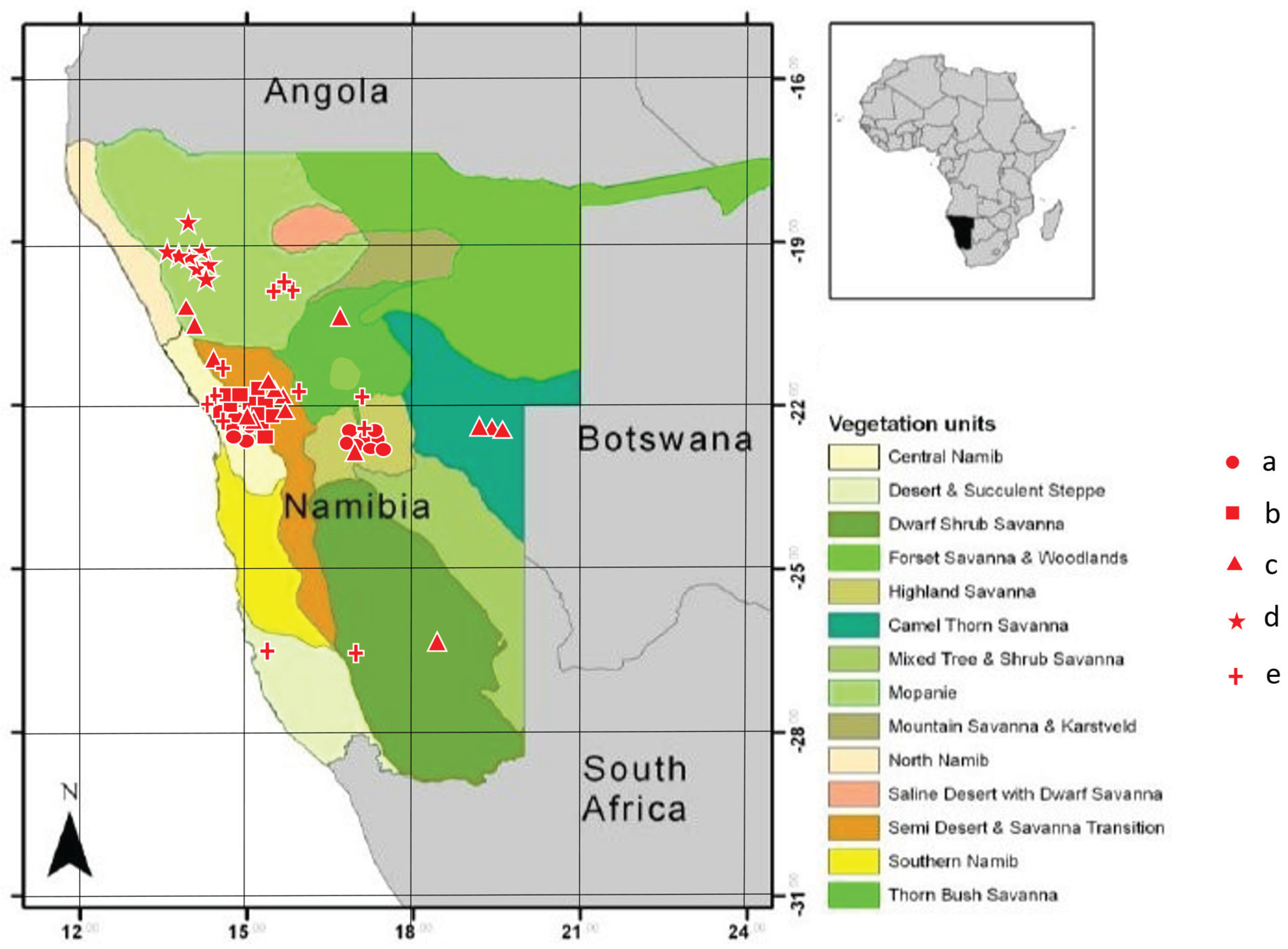

Table 1). Specimens were collected in various sites in the western part of Namibia, dominated by deserts, and semi-deserts (

Figure 1). Specimens were collected throughout the year (

Table 1).

Stomach content was placed in Petri dishes. Prey were identified to the least possible taxon. Food content were assessed in terms of the frequency of occurrence of prey taxa (the percentage of stomachs containing given taxon in relation to the total number of stomachs containing prey) and numerical percentage of prey items (the percentage pf given prey taxa in relation to the total number of prey items identified). Each prey item was measured with a ruler to the nearest 1 mm.

For each species, also the niche breath, and niche breath overlap were calculated using the following formula:

Niche breadth (PIANKA 1986):

where: i – resource category, p – proportion of resource category i, n- total number of categories

B ranges from 1 to n, indicating whether the species preys upon a wide range of prey (high value, close to n) or specializes on a limited range of prey (low value, close to one).

Niche breadth overlap (PIANKA 1986):

where: i – resource category, p – proportion of resource category i, n- total number of categories, j –female, k – male

Ojk ranges from 0 (no similarity) to 1 (totally similar).

3. Results

All skink species investigated preyed almost exclusively on insects (

Table 2). Only in the diet of

T.acutilabris single spider was recorded (

Table 3). Among insects four taxa comprised the bulk of diet in all five species investigated: beetles (Coleoptera), grasshoppers (Orthoptera), termites (Isoptera), ants (Hymenoptera: Formicidae) and larvae. Their overall contribution changed from 92.2% to 97.7% of all prey items in the diet of particular skink species. However, the proportions of particular taxa varied markedly. Beetles were important prey of

T.sulcata, and

T.occidentalis; grasshoppers –

T.sulcata, termites –

T.hoeschi and

T.acutilabris; ants –

T.spilogaster and

T.acutilabris; while larvae were important diet of

T. sulcata. Beetles were represented by at least five families, associated mainly with the ground as feeding place. Orthopterans were also represented by at least five families, with clear dominance of locusts (Acrididae) and crickets (Gryllidae), also associated mainly with the ground as foraging place (

Table 3). Also termites and ants are typical ground-foraging insects. Insect larvae were represented mainly by Coleoptera, Diptera and Lepidoptera. Other insects were preyed upon only occasionally and belonged to the order Hymenoptera, represented by bees Apionoidea and wasps Vespoidea. These, like ants and termites, are social taxa.

Most prey items (ants, termites, spiders, most beetles, flies) were below 10 mm long, some were 11-20 mm in length (crickets, grasshoppers, larvae, some beetles and wasps) and only two wasp species were 25 mm in length. One exceptionally large prey was recorded in the diet of T.sulcata (SMR4607; SVL: 62.3, TL: 7.7 [tail broken off], collected in Suiderhof, Windhoek, on 25 April 1985), a locust (Orthoptera: Acrididae: Acridinae) 30.2 mm long

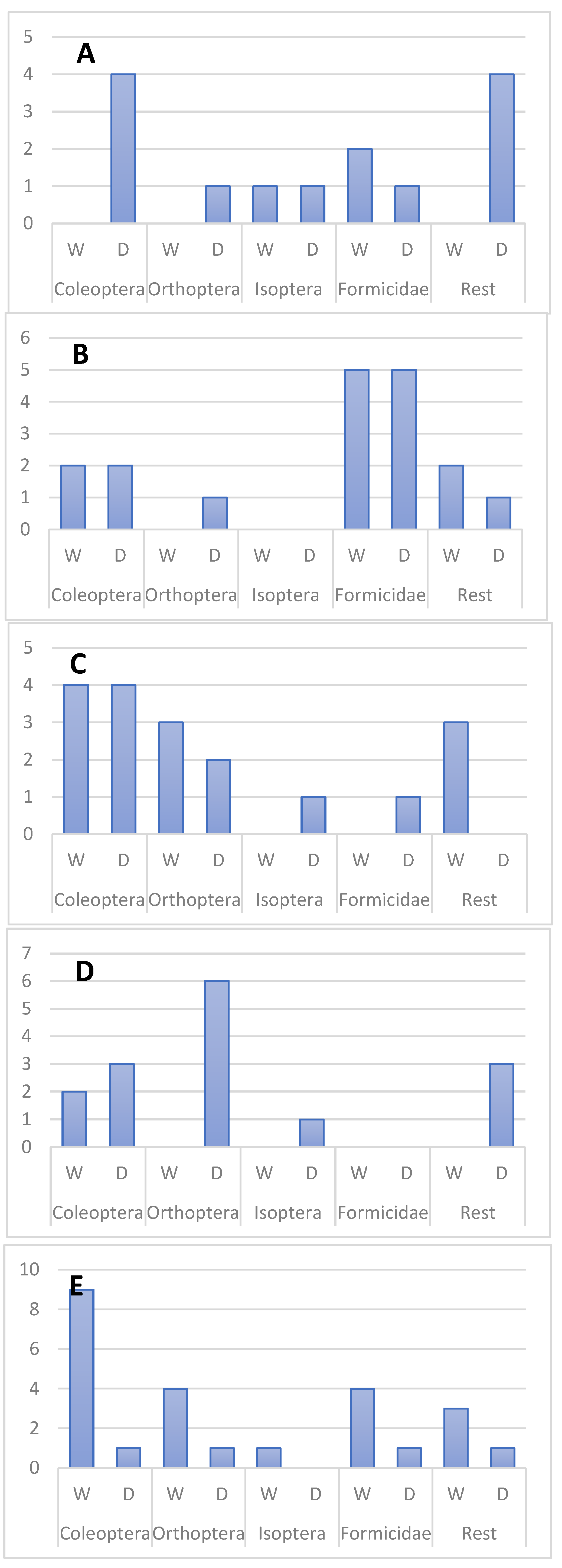

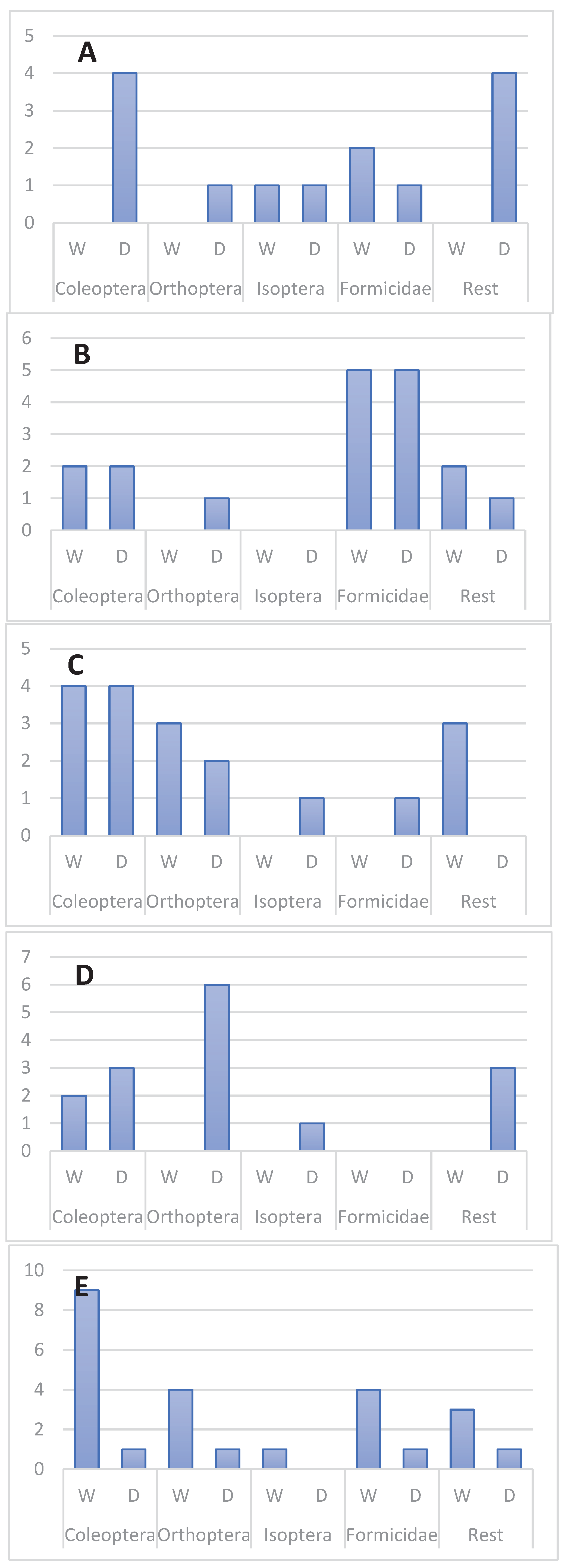

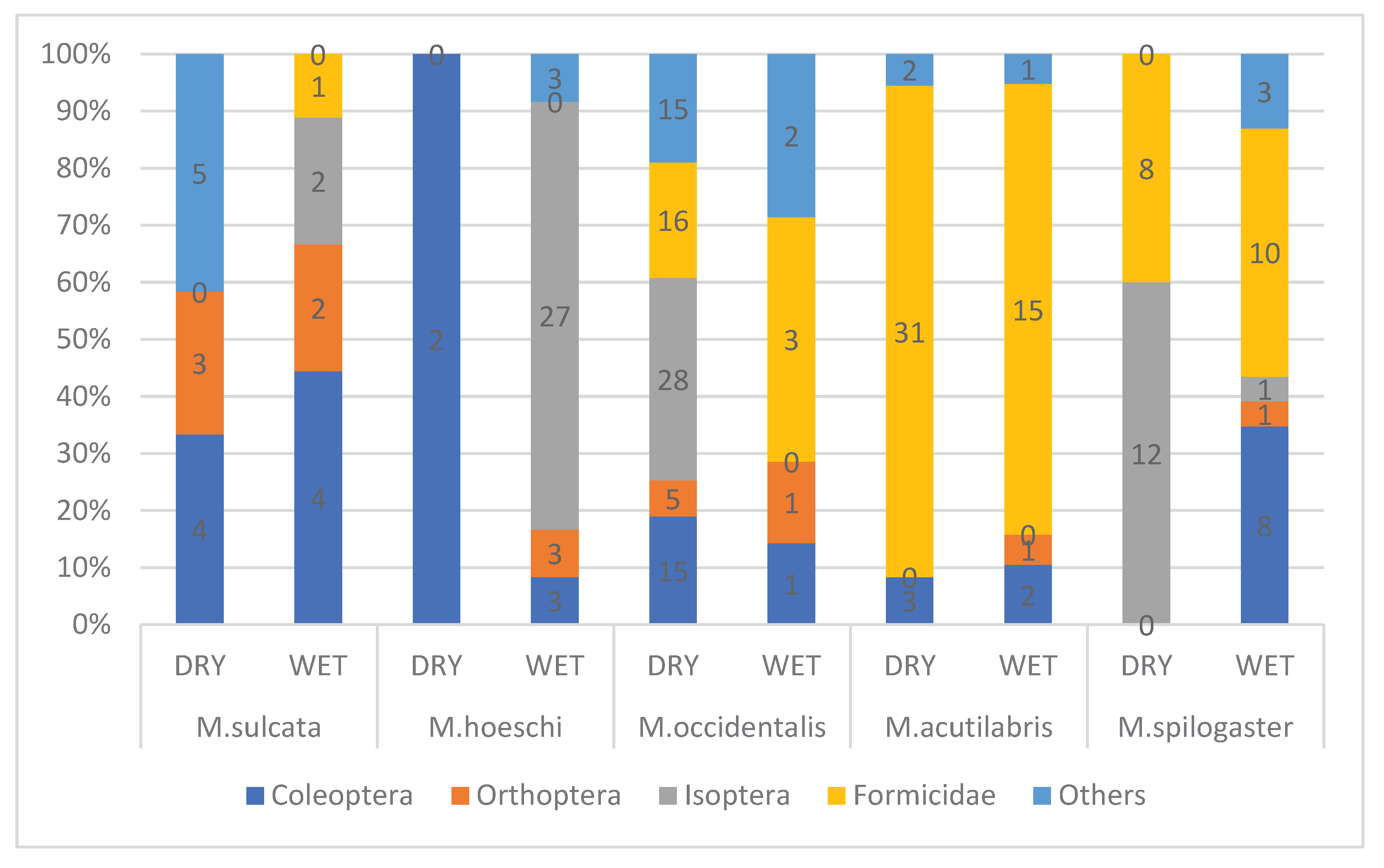

All main prey groups were recorded in dry and wet season in all five skink species. Ants appear to be more important in dry, while termites – in wet season.

T. hoeschi preyed mostly on beetles in dry, while on termites – in the wet season (

Figure 2,

Figure 3 and

Figure 5).

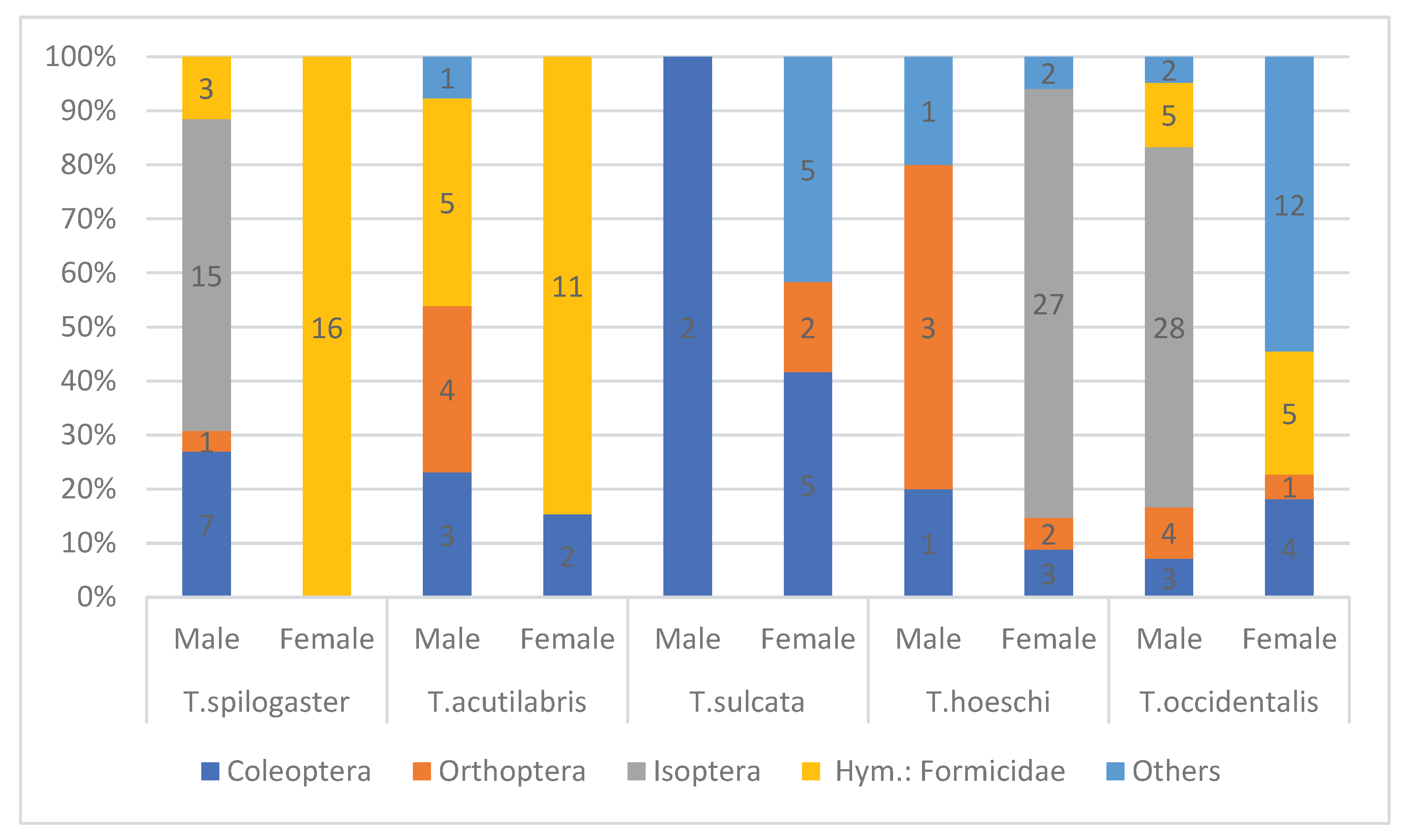

Both males and females fed on the same prey groups, but there were marked differences in the proportions of these groups in particular skink species. In general males preyed more on beetles, while females – more on ants (

Figure 4).

Niche breath ranged from 0.25 in

T.occidentalis to 0.47 in

T.hoeschi (

Table 2). The highest overlap of feeding niches was recorded between

T.spilogaster and

T.sulcata, and between

T.spilogaster and

T.acutilabris; while the lowest overlap was recorded between

T.acutilabris and

T.sulcata, and between

T.sulcata and

T.hoeschi (

Table 4).

Very high (O

jk >0.90) niche overlap was recorded between

T.spilogaster and T.acutilabris, T.subcostata and

T.occidentalis, and between

T.acutilabris and

T. occidentalis. On the other end, low food niche overlap (O

jk<0.40) was recorded between

T.sulcata and

T.acutilabris, and between

T.sulcata and

T.hoeschi (

Table 4).

Figure 2.

Seasonal variation in the diet of T. spilogaster (A), T. acutilabris (B), T. sulcata (C), T. hoeschi (D) and T. occidentalis (E). Number of prey items are shown on vertical axis.

Figure 2.

Seasonal variation in the diet of T. spilogaster (A), T. acutilabris (B), T. sulcata (C), T. hoeschi (D) and T. occidentalis (E). Number of prey items are shown on vertical axis.

Figure 3.

Seasonal variation in the frequency of occurrence of main prey groups in the diet of T. spilogaster (A), T. acutilabris (B), T. sulcata (C), T. hoeschi (D) and T. occidentalis (E). Number of prey items are shown on vertical axis.

Figure 3.

Seasonal variation in the frequency of occurrence of main prey groups in the diet of T. spilogaster (A), T. acutilabris (B), T. sulcata (C), T. hoeschi (D) and T. occidentalis (E). Number of prey items are shown on vertical axis.

Figure 4.

Proportions of main prey groups in the diet of male and female of five Trachylepis species occurring in arid south-west Africa. The number of prey items are indicated in each bar (prey group) of each column.

Figure 4.

Proportions of main prey groups in the diet of male and female of five Trachylepis species occurring in arid south-west Africa. The number of prey items are indicated in each bar (prey group) of each column.

Figure 5.

Seasonal variation in the proportions of main prey groups in the diet of five Trachylepis species occurring in arid south-west Africa. The number of prey items are indicated in each bar (prey group) of each column.

Figure 5.

Seasonal variation in the proportions of main prey groups in the diet of five Trachylepis species occurring in arid south-west Africa. The number of prey items are indicated in each bar (prey group) of each column.

4. Discussion

In Trachylepis punctatissima and T. varia from the Free State, South Africa, females had wider niche breadths than males and isopterans comprised the bulk of the diet. The diet was supplemented by larvae in both species, and arachnids in T. varia (Heidemann et al. 2024). Lizards represented by Mabuya, Agama, Ichnotropis and Lygodactylus from Dambwa Forest Reserve, Livingstone, Zambia, fed mainly on termites and supplemented the diet with ants, beetles, grasshoppers and other insects (Simbotwe, Garber 1979). In southern Africa, the diet of Trachylepis margarifer was dominated by termites (WYMANN & WHITING 2002); geckos preyed mainly on Hodotermes mossambicus termites (48.2v%), beetles (10.6v%), and grasshoppers (9.1v%) (PIANKA & HUEY 1978); the tree agama Acanthocercus a. atricollis preyed mainly upon ants (92.8 % of all prey items, 17.9 % of total prey volume) and beetles (4n% vs. 26.3v%) (REANEY & WRITING 2002); Pedioplanis husabensis and Rhoptropus bradfieldi mainly on beetles (MURRAY et al. 2016); Acanthocercus atricollis mostly on ants (REANEY & WHITING 2002); Meroles cuneirostris fed mainly (in the order of preference): Curculionidae > Tenebrionidae larvae > Tenebrionidae imagi > ants > other Hymenoptera; while Aporosaura anchietae: Tenebrionidae larvae > Lepidoptera > Tenebrionidae imagi > Pentatonidae > other beetle larvae (ROBINSON & CUNNINGHAM 1978). BAUER et al. (1989) recorded Hodotermes mossambicus termites as main prey of lizards.

Beyond southern Africa, beetles constituted the main prey of three skin species (Chalcides ocellatus, Scincus scincus and Sphenops sepsoides) in Sinai, Egypt (ATTUM et al. 2004); Trachylepis quinquetaeniata in Egypt (KADRY et al. 2017); Chalcides ocellatus in Cyprus Island (CICEK & GOCMEN 2013). While ants, bugs and grasshopper often supplemented their diet (ATTUM et al. 2004, KADRY et al. 2017, CICEK & GOCMEN 2013). The staple diets of Trachylepis adamastor and T. thomensis from the Gulf of Guinea consisted of mites, ants, spiders, flies and beetles (SOUSSA ET AL. 2022).

Ants, termites, small beetles and grasshoppers comprise, therefore, the main diet of skins both in southern Africa and other regions of Africa. Results of the present study also this general statement. Most of the insects preyed upon by the Trachylepis skinks are among the most common invertebrate groups in arid regions of southern Africa (own observ.). However, contrary to expectations, Tenebrionidae beetles comprised a low contribution to the diet of all skink species studied. This is the most diverse, widespread and commonest terrestrial beetle family in arid regions of Namibia and other regions of southern Africa (BRANCH 1992). Probably they are poisonous to the lizards and their exoskeletons may be too hard for digestion.

Morphological, ecological, and behavioural characters may influence feeding techniques in lizards. Two main hunting strategies can be distinguished in this group living in arid regions of southern Africa: sit-and-wait predatory strategy recorded among others in geckos and chameleons; and cruising (intensive) predatory strategy known among others in skinks and lacertids (ANANJEVA & TSELLARIUS 1986, WYMANN & WHITING 2002). The sit-and-wait strategy increases with the increase of food resources, while the intensive strategy is linked to territoriality (WYMANN & WHITING 2002). In all Trachylepis skink species studied here, the intensive predatory strategy predominates.

Mean prey size is correlated with the mean size of lizards of Gekkonidae, Scincidae, Lacertidae and Agamidae (ANANJEVA & TSELLARIUS 1986). Since skinks are relatively small, prey longer than 20 mm were rare, and longer than 30 mm were preyed upon sporadically. In most cases, larger preys were slow-moving insects, such as larvae.

Most Trachylepis skinks preyed mostly on termites and ants. These are social insects living mainly on the ground or underground. This suggests patchy resource utilization by these lizards. The contribution of these insects may be much higher at the beginning of rainy season, when alate termites swarm usually 3-5 days after first heavy rain (in Namibia usually in October/November) (BAUER et al. 1989).

Trophic niche overlap between the male and female of the same species was low suggesting strong competition for the food resource. Lower niche breadth in males compared to females may be due to morphological and behavioural differences and merits further investigation (HEIDEMANN ET AL. 2024).

As shown in this study, Trachylepis skinks living in Namibia (KOPIJ 2021; this study) are food generalists, preying upon the most common and most easily available insect prey, such as beetles, locusts, ants and termites. In fact, most lizard species worldwide are generalist foragers and are probably relatively unselective of the various types of arthropods available in their environment (TOFT 1985, LUISELLI 2008).

The Trachylepis skinks studied here may avoid competitive exclusion by foraging among a different microhabitats, by using different foraging mode (most lizard species are sit-and-wait foragers), and by preying upon insects (e.g., termites and ants) occurring in higher aggregations.

The niche overlap hypothesis of PIANKA (1972) holds that maximal tolerable niche overlap should vary inversely with the intensity of competition for the resource. A review of more than 50 studies conducted by LUISELLI (2008) concludes, however, that trophic niche separation was not a general rule among sympatric lizards. This has been also supported by TOFT (1985), KOPIJ (2021), HEIDEMANN ET AL. (2024), and the present study.

In order to co-exists at the same place, the Trachylepis species have to partition their temporal (diurnal or nocturnal), spatial (habitat or micro habitat), and trophic niche axes to reduce interspecific competition and enable co-existence.

The method for identifying dietary items (mostly stomach or faecal-pellet content analysis) does not allow for accurate prey identification. Prey items (mostly insects) in majority of cases are identified to order level. For studies of niche segregation, diet should be analyzed at least to the family or genus level. Inappropriate methods may lead to the erroneous conclusion on feeing niche partitioning in most diet studies.

Structure has a temporal dimension (GOTELLI AND GRAVES 1996). In most cases, data on diet composition are obtained in different seasons of the year and over several years. Id averaged, results of such studies provide mean values, which may obscure short-term dietary differences, more important for studies on food niche segregations.

5. Conclusions

This section is not mandatory but can be added to the manuscript if the discussion is unusually long or complex.

Funding

This research received no external funding.

Conflicts of Interest

The author declare no conflicts of interest.

References

- Ananjeva, N.B.; Tsellarius, A.Y. On the factors determining desert lizard’s diet. In: Roček Z. (ed.): Studies in Herpetology; p. 445–448; 1986.

- Alexander, G.; Marais, J. A guide to the reptiles of southern Africa. Struik Nature, Cape Town, 2017.

- Attum, O.; Covell, C.; Eason, P. The comparative diet of three Saharan sand dune species. African Journal of Herpetology 2004, 53, 91–94. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Baker, M.A.A.; Katbeh–Bader, A.A.; Ghlelat, A.A.; Disi, A.M.; Amr, Z.S. Diet and food niche relationships of lizard assemblages in Jordán. Herpetological Conservation and Biology 2021, 16, 117–127. [Google Scholar]

- Bauer, A.M.; Russell, A.P.; Edgar, B.D. Utilization of the termite Hodotermes mossambicus (Hagen) by gekkonid lizards near Keetmanshoop, South West Africa. South African Journal of Zoology 1989, 24, 239–243. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Branch, B. Snakes and other reptiles of southern Africa. 2nd ed. Struik, Cape Town, 1992.

- Broadley, D.G. A review of the genus Mabuya in southeastern Africa (Sauria: Scincidae). African Journal of Herpetology, 2000, 49. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Cicek, K.; Gocmen, B. Food composition of ocellated skink Chalcides ocellatus (Forskal, 1775) (Squamata: Scincidae), from the Cyprus Island. Acta Herpetologica 2013, 8, 167–170. [Google Scholar]

- de Sousa, A.C.A. Phylogeography, ecology and conservation of skink Adamastor, Trachylepis adamastor Ceríaco, 2015 (Master's thesis, Universidade de Evora (Portugal), 2017.

- Heideman, N.; Bates, M.; Zhao, Z. Trophic structure and dietary overlap in the sympatric skinks Trachylepis punctatissima and Trachylepis varia from central South Africa. African Journal of Ecology 2024, 62. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Herrmann, H.W.; Branch, W.R. Fifty years of herpetological research in the Namib Desert and Namibia with an updated and annotated species checklist. Journal of Arid Environments, 2013, 93, 94–115. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Holm, E.; Scholz, C.H. Insects of southern Africa. 2nd ed. Protea Boekhuis, 2012.

- Huey, R.B.; Pianka, E.R. Pattern of niche overlap among broadly sympatric versus narrowly sympatric Kalahari lizard. Ecology 1977, 58, 119–128. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Kadry, M.A.M.; Mohamed, H.R.H.; Hosney, M. Ecological and biological studies on five-lined skink, Trachylepis (=Mabuya) quinquetaeniata inhabiting two different habitats in Egypt. Cellular & Molecular Biology 2017, 63, 27–36. [Google Scholar]

- Kopij, G. Diet of five Trachylepis skink species (Scincidae: Mabuyinae) in savanna biome of Namibia. Polish Journal of Ecology 2021, 69, 183–192. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Kopij, G.; Buiswalelo, B. Notes on the reproduction of Trachylepis skins in Namibia. African Herp News 2022, 80, 34–39. [Google Scholar]

- Luiselli, L. Do lizard communities partition the trophic niche? A worldwide meta-analysis using null models. Oikos 2008, 117, 321–330. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Miller, A.K.; Erasmus, B.F.N.; Alexander, G.J. Gut and intestinal passage time in the rainbow skink (Trachylepis margaritifer): implications for stress measures using faecal analysis. Journal of Animal Physiology and Animal Nutrition 2013, 97, 960–970. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Murray, I.W.; Fuller, A.; Lease, H.M.; Michell, D; Hetem, R. S. Ecological niche separation of two sympatric insectivorous lizard species in the Namib Desert. Journal of Arid Environment 2016, 124, 225–232. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Pianka, E.R. Ecology and natural history of desert lizards. Princeton University Press, Princeton (N.J.), 1986.

- Pianka, E.R.; Huey, R.B. Comparative ecology, resource utilization and niche segregation among gekkonid lizards in southern Kalahari. Copeia 1978, 4, 691–701. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Reaney, L.T.; Writing, M.J. Life on a limb. Ecology of the tree agama (Acanthocercus a. atricollis) in southern Africa. Journal of Zoology (London) 2022, 257, 439–448. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Simbotwe, M.P.; Garber, S.D. Feeding habits of lizards in the genera Mabuya, Agama, Ichnotropis and Lygodactylus in Zambia, Africa. Transactions of the Kansas Academy of Science (1903), 1979, 1979, 55–59. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Sousa, A.C.A.; Marques, M.P.; Ceríaco, L.M. Population size and diet of the Adamastor skink, Trachylepis adamastor Ceríaco, 2015 (Squamata: Scincidae), on Tinhosa Grande Islet, São Tomé and Príncipe, Gulf of Guinea. Herpetology Notes, 2022, 15, 553–557. [Google Scholar]

- Robinson, M.D.; Cunningham, A.B. Comparative diet of two Namib Desert sand lizards (Lacertidae). Madoqua 1978, 11, 41–53. [Google Scholar]

- Toft, C.A. Resource Partitioning in Amphibians and Reptiles. Copeia 1985, 1, 1–21. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Uetz, P.; Freed, P.; Hošek, J. (Eds.) . The Reptile Database. http:/www/.reptile-databaes.org. Accessed: 11.05.2020.

- Wymann, M.N.; Whiting, M.J. Foraging ecology of rainbow skink (Mabuya margaritifer) in southern Africa. Copeia 2002, 4, 943–957. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

|

Disclaimer/Publisher’s Note: The statements, opinions and data contained in all publications are solely those of the individual author(s) and contributor(s) and not of MDPI and/or the editor(s). MDPI and/or the editor(s) disclaim responsibility for any injury to people or property resulting from any ideas, methods, instructions or products referred to in the content. |

© 2025 by the authors. Licensee MDPI, Basel, Switzerland. This article is an open access article distributed under the terms and conditions of the Creative Commons Attribution (CC BY) license (http://creativecommons.org/licenses/by/4.0/).