1. Introduction

Ecology might be considered as the experimental analysis of distribution and abundance of species (Krebs 2009). In regard to birds, such an analysis has been thoroughly conducted in Europe, resulting in a huge amount of data (Glutz von Blotzheim 1966-1996; Cramp 1977-1994; Tucker & Heath 1994; Bauer & Berthold 1997; BirdLife International 2004). In the tropical regions of the world. it is however still far from completion (del Hoyo et al. 1992-2011). For example, while in southern Africa, fauna of which is one of the most intensively studied in tropical regions of the world, bird distribution has been well-researched (Hockey et al. 2005, SABAP1, SABAP2), but still little is known about abundance of most species. Even population densities of conspicuous and strongly territorial birds, such as shrikes (Laniidae) and bush-shrikes (Malaconotidae) are poorly investigated (Hockey et al. 2005, Brown et al. 2020). These groups are well-represented in Africa, with 136 species from the family Malaconotidae (excluding Prionopidae and Platysternidae, as today these are regarded as separate families), and 31 species from the family Laniidae (Brown et al. 2020). In Namibia, 10 and 7 species respectively were recorded (Kolberg 2022).

Shrikes are also known as strongly territorial species. Since it is a diverse group in Africa and many species are common, they are also a convenient object of studies on territoriality. This phenomenon has been intensively studied in many Palearctic and Nearctic bird species (Cramp 1977-1994, Glutz von Blotzheim 1966-1996, Barthold & Bauer 1997), but much less in the Afrotropical Region (Hockey et al. 2005; Brown et al. 2020). Territoriality has usually intraspecific character, and its main function is population density regulation (Krebs 2009). There are, however, cases of interspecific territoriality, even among not closely-related species, for example between, between the Parus major and Fringilla coelebs in Scotland (Reed 1982); Acrocephalus species in Europe (Brown and Davies 1949, Murray 1988, Hoi et al. 1991); Corvus corone - C. monedula, C. frugilegus in UK (Combs 1960); Lanius collurio – L. nubicus in Egypt (Simmons 1951); Asio otus – Otus asio – Aegoluis accadicus in Michigan, USA (Wilson 1938), Strix varia – Tyto alba in Michigan (Wilson 1938), Parulidae in north America (Losin et al. 2016), among Sylvia and among Phylloscopus species in UK and Scandinavia (Cody 1978). Drury et al. (2020) have shown that interspecific territoriality is actually widespread, recorded in 32% of Nearctic passerines, most of which (73%) are territorial with only one other species, but with 19% of cases involving not closely-related species, i.e. represented by different families. The knowledge on the issue of the interspecific territoriality and the philopatry in African birds is almost non-existent (Hockey et al. 2005; Brown et al. 2020).

The territoriality is often accompanied by the philopatry, which can be defined as an attachment to the natal place. It can be assumed that the stronger the territoriality, the higher the degree of the philopatry. The philopatry may affect territorial behaviour, mortality rate and reproductive success, population density and dynamics, and genetic variability of a population (Krištín et al. 2007). The degree of the philopatry is not only variable interspecifically, but may also vary within a species. It is shaped by environmental factors and population density (Coulson 2006). The philopatry is, however, understudied and the subject is especially little known in African birds (Hockey et al. 2005; Brown et al. 2020).

The aim of the study is to: 1) estimate population densities of selected shrike species and year-to-year changes in the density (population dynamics); 2) investigate interspecific territoriality among shrike species; 3) investigate the philopatry of these species; 4) study habitat preferences of particular shrike species; 5) compare population densities of these shrike species in different habitats in Africa.

2. Materials and Methods

2.1. Study Area

The study area is situated in Ogongo UNAM Campus, Omusati Region, N Namibia. The Cuvelai Drainage System, where the study area is loctaed, is a unique ecosystem comprising a network of water canals (oshanas), mopane and acacia savannas (Mendesohn et al. 2000, 2009; Mendesohn & Weber 2011). The natural vegetation comprises acacia savanna composed mainly of Acacia erioloba, A. nilotica, A. fleckii, A. mellifera, Albizia anthelmintica, Dichrostachys cinerea, Colophospermum mopane, Combretum spp., Commiphora spp., Grewia spp., Ficus sycomorus, Boscia albitrunca, Sclerocarya birrea, Terminalia sericea, Zyzyphus mucronata, Hyphaene petersiana (Kangombe 2007). There is only small part of mopane savanna, composed almost entirely of young Colophospermum mopane shrubs. Both savannas are utilized as a pasture for cattle, sheep and goats.

The total surface of the study area was 400 ha. Most of it (70%) constitutes natural acacia savanna, the remaining is converted into yards with buildings, arable fields, orchards and sport fields. The contribution and distribution of different land forms is shown in

Table 1 and

Figure 2,

Figure 3,

Figure 4 and

Figure 5 respectively. There are also numerous exotic trees planted in and around human settlements, such as

Kigelia africana, Moringa oleifera, Melia azedarach, Dodonaea viscosa, Eucalyptus camelduensis. There are several permanent water bodies with standing water, and the area borders with an artificial water canal to the north and an extensive oshana (natural grassy depression filled with water in the rainy season) to the east.

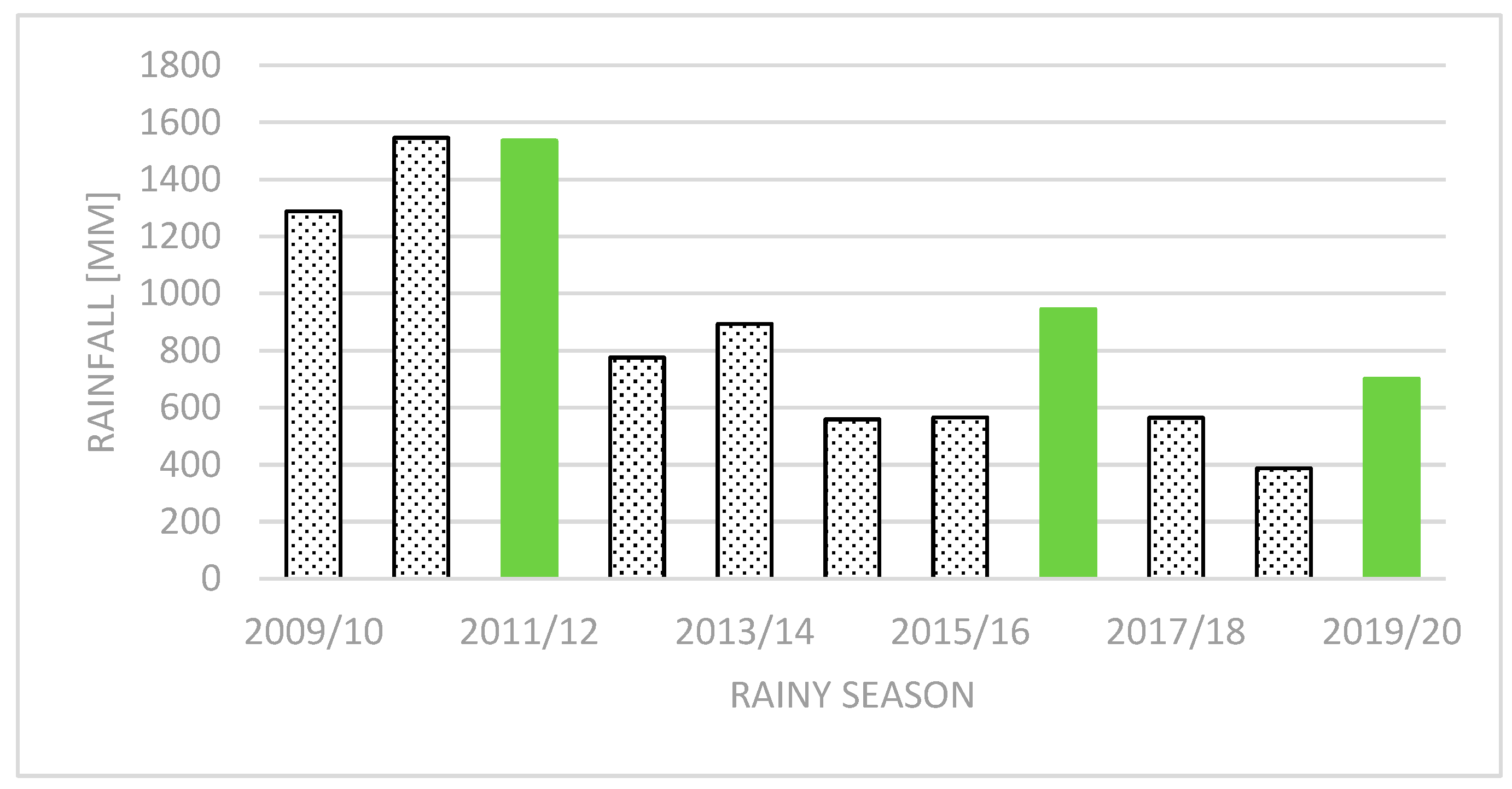

Ogongo has semi-arid climate. The summers are sweltering and partly cloudy; the winters are short, comfortable, and clear (Mendelsohn et al., 2000; Mendelsohn & Weber 2011). In 2019/2020 rainy season (September-April) the total amount of rain in nearby Onguadiva was 702 mm, in the previous rainy season – 388 mm; the long-term annual average is 724 mm (

https://weatherandclimate.com/namibia/oshana/ongwediva).

Table 1.

Microhabitats distinguished in the study area within the acacia savanna.

Table 1.

Microhabitats distinguished in the study area within the acacia savanna.

| Microhabitat |

Size [ha] |

% |

| Natural savanna |

278 |

69.5 |

| Transformed savanna |

122 |

30.5 |

| Arable fields |

30 |

7.5 |

| Orchards |

10 |

2.5 |

| Sport field |

2 |

0.5 |

| Yards with buildings |

70 |

17.5 |

| Total |

400 |

100 |

Figure 1.

Year-to-year changes in the amount of rain in rainy seasons (September-April) in Onguadiva in 2009-2020.

Figure 1.

Year-to-year changes in the amount of rain in rainy seasons (September-April) in Onguadiva in 2009-2020.

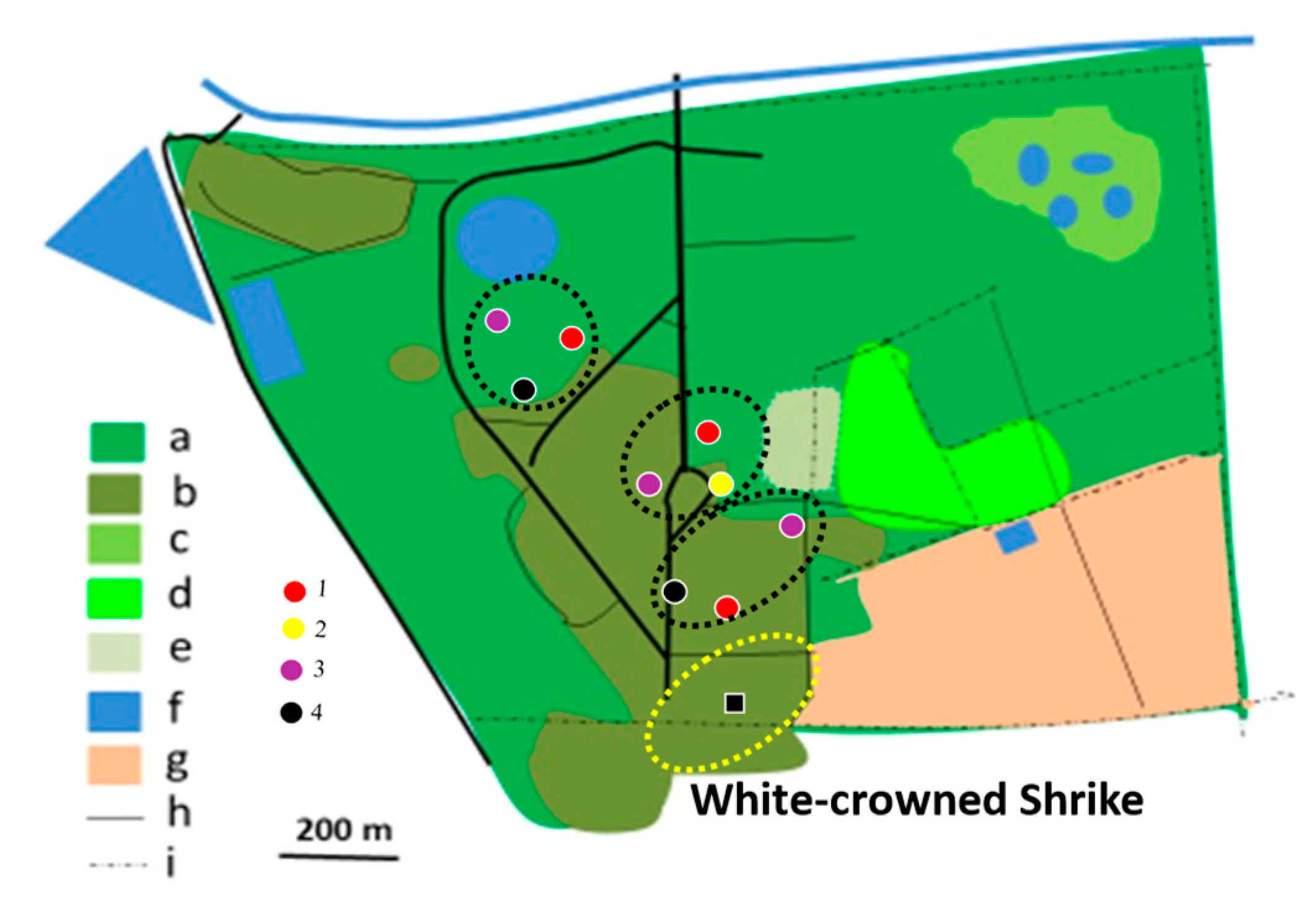

Figure 2.

Distribution of Southern White-crowned Shrike territories in Ogongo in 2017 (yellow circles) and 2020 (black circles). Explanations: habitats (land uses): a – acacia savanna, b – built-up area, c – disturbed acacia savanna, d – orchard, e – sport field, f – water bodies, g – arable ground, h – roads, i – fences. 1, 2, 3, 4 – records of birds during survey 1, 2, 3, or 4. Encircled are occupied territories. .

Figure 2.

Distribution of Southern White-crowned Shrike territories in Ogongo in 2017 (yellow circles) and 2020 (black circles). Explanations: habitats (land uses): a – acacia savanna, b – built-up area, c – disturbed acacia savanna, d – orchard, e – sport field, f – water bodies, g – arable ground, h – roads, i – fences. 1, 2, 3, 4 – records of birds during survey 1, 2, 3, or 4. Encircled are occupied territories. .

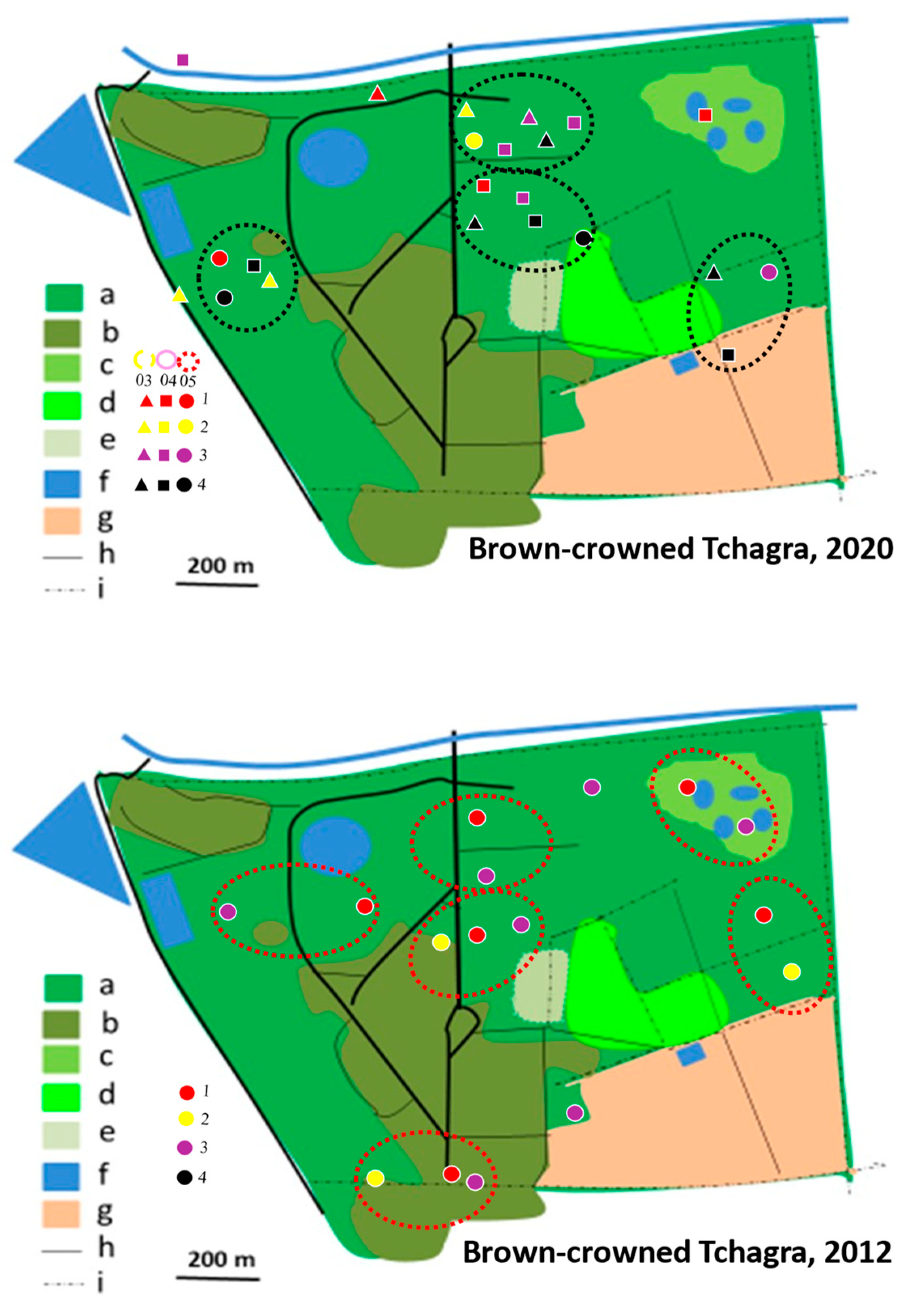

Figure 3.

Distribution of Brown-crowned Tchagra territories in Ogongo in 2012 and 2020. Explanations: Surveys: 1, 2, 3, 4: first, second, third and fourth survey respectively in March (03), April (04) and May (05). Other symbols as in

Figure 2.

Figure 3.

Distribution of Brown-crowned Tchagra territories in Ogongo in 2012 and 2020. Explanations: Surveys: 1, 2, 3, 4: first, second, third and fourth survey respectively in March (03), April (04) and May (05). Other symbols as in

Figure 2.

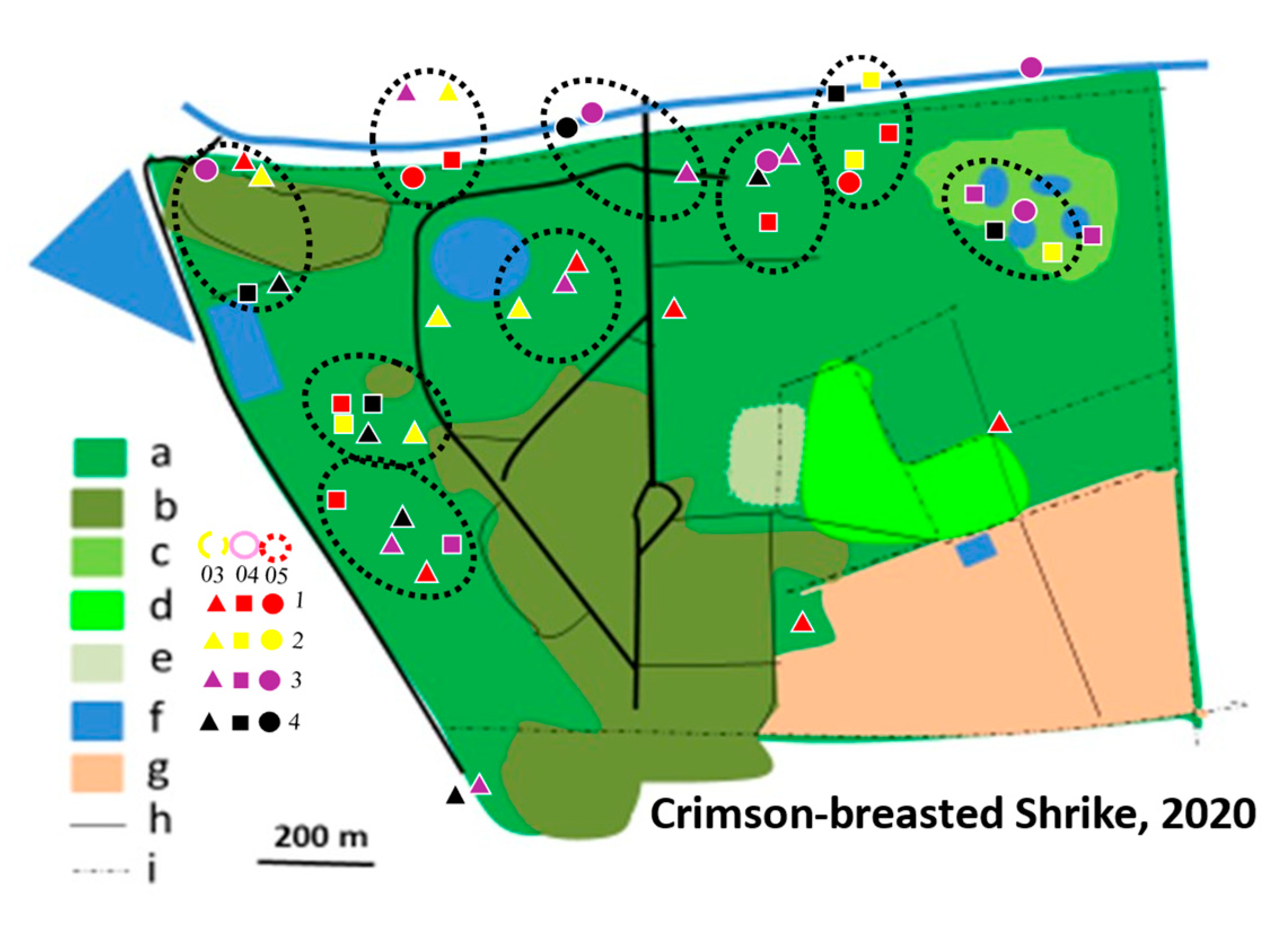

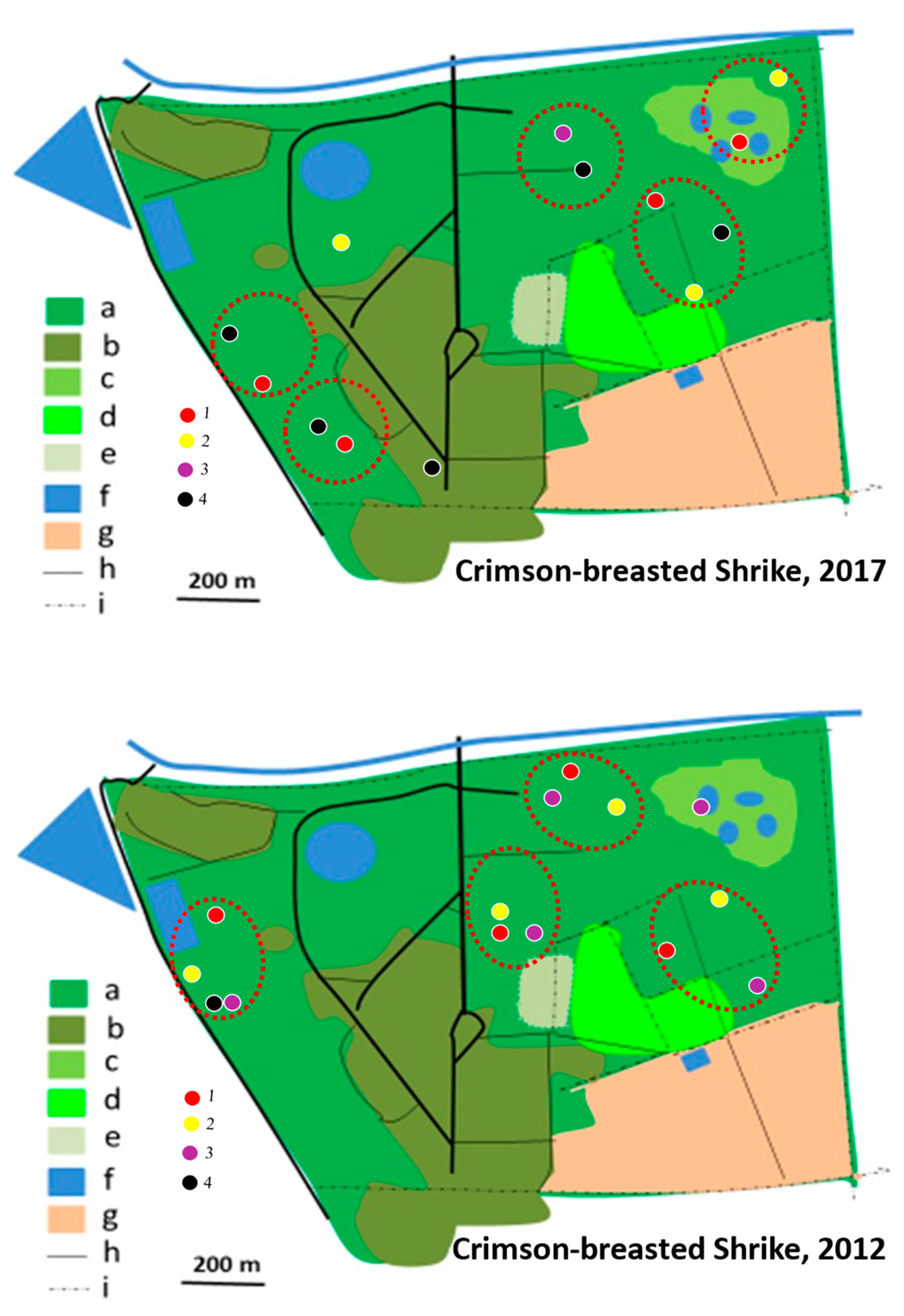

Figure 4.

Distribution of Crimson-breasted territories in Ogongo in 2012, 2017 and 2020.

Figure 4.

Distribution of Crimson-breasted territories in Ogongo in 2012, 2017 and 2020.

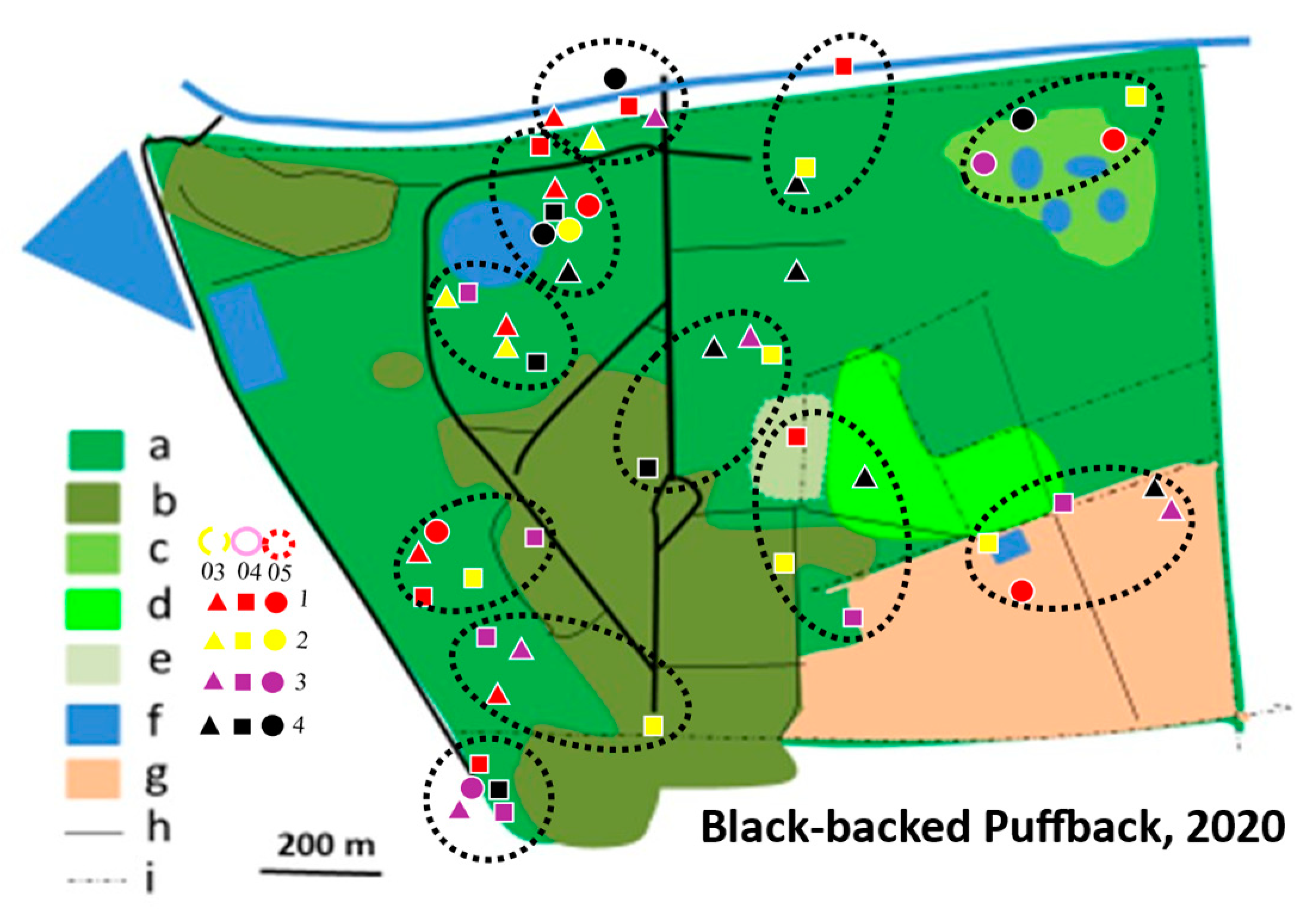

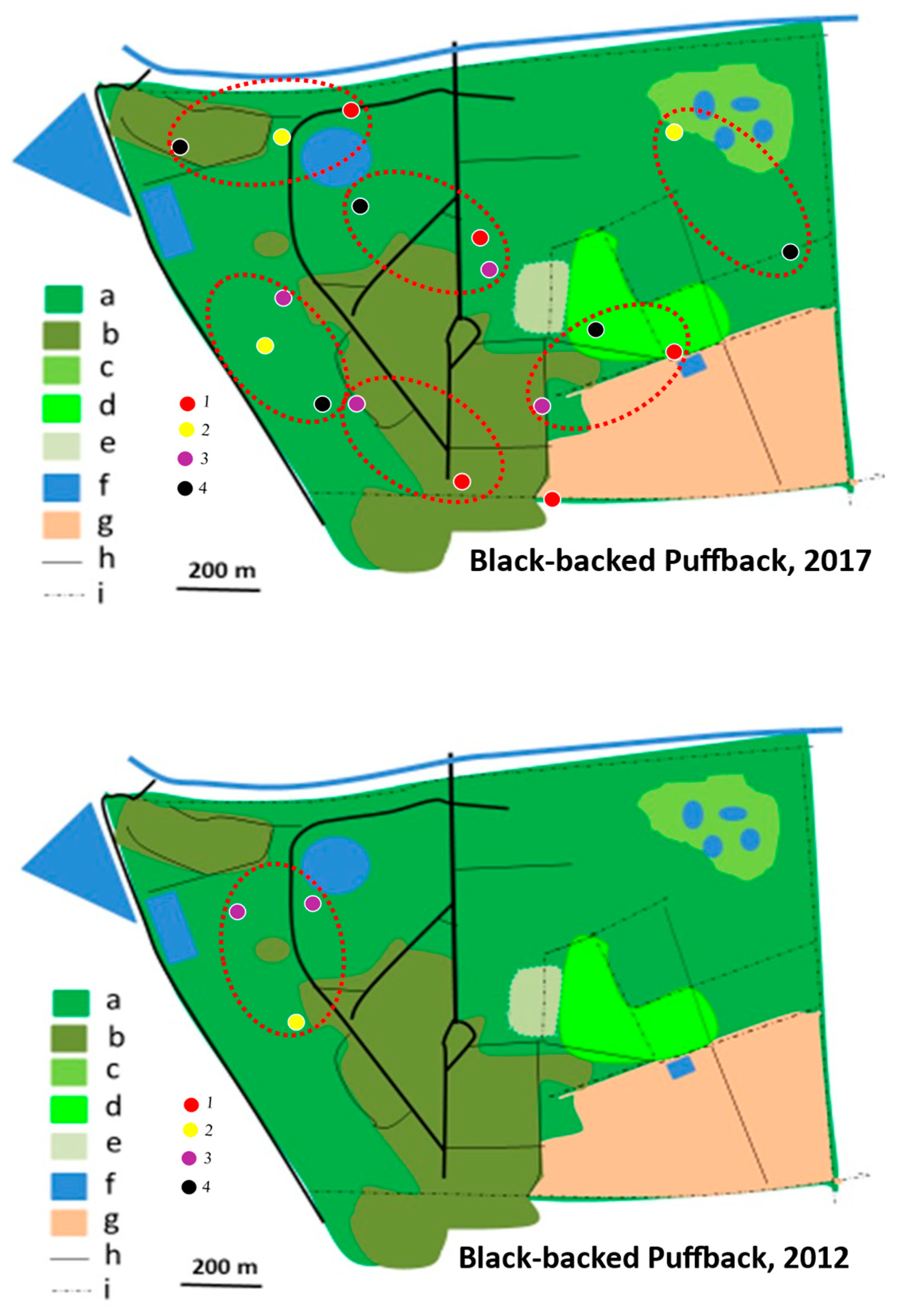

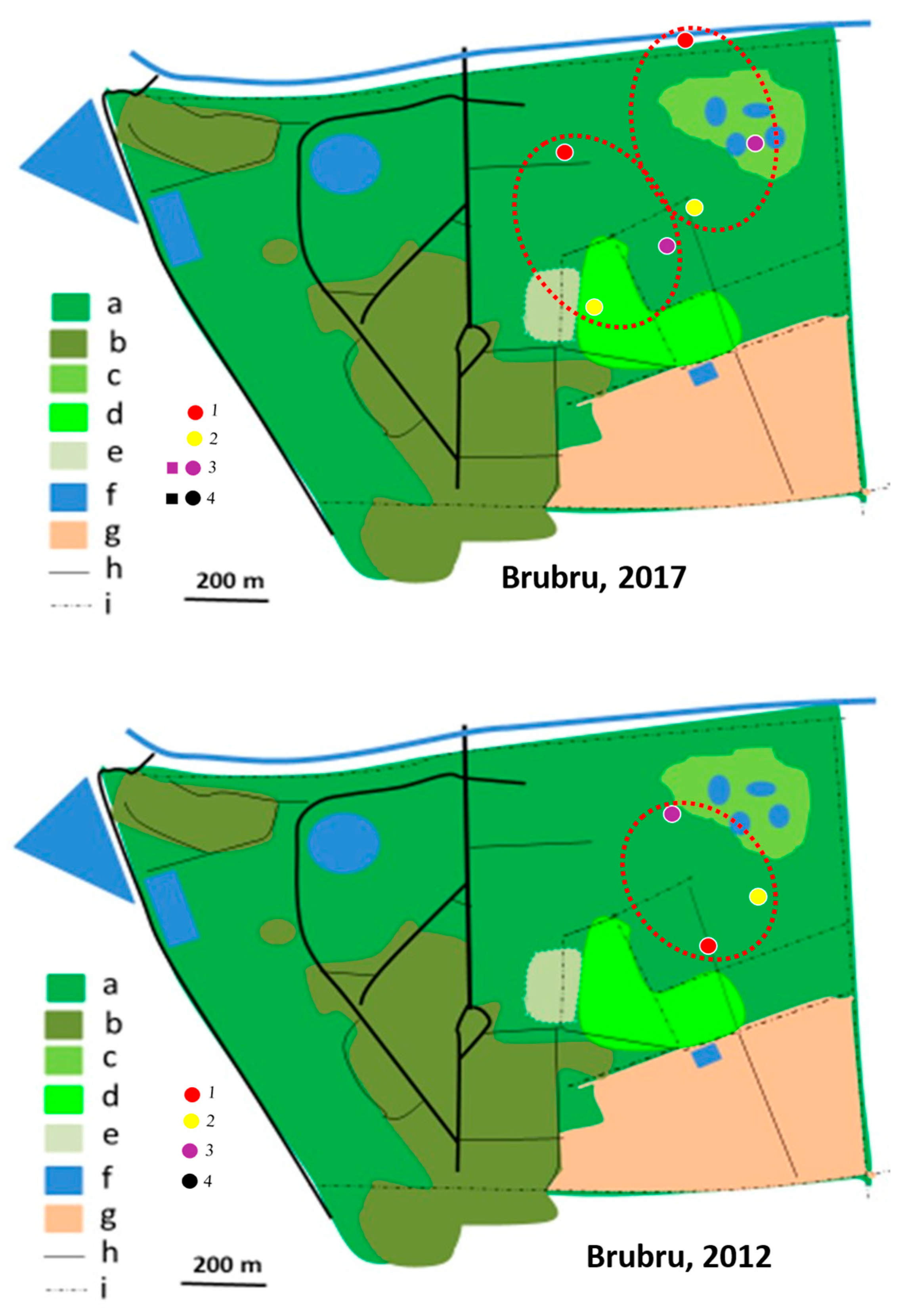

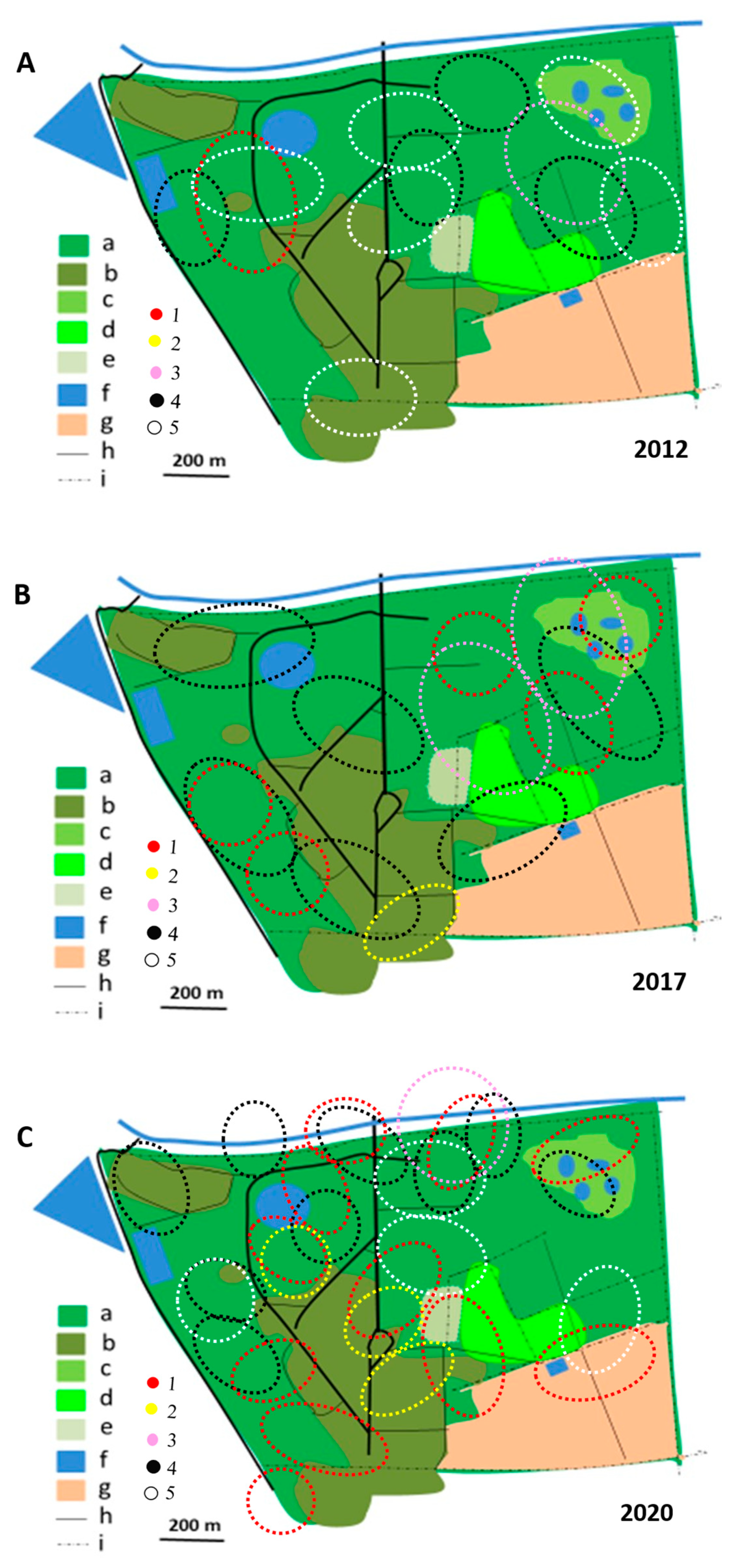

Figure 5.

Distribution of Black-backed Puffback territories in Ogongo in 2012, 2017 and 2020.

Figure 5.

Distribution of Black-backed Puffback territories in Ogongo in 2012, 2017 and 2020.

2.2. Methods

Studies were conducted in three years: 2012, 2017 and 2020. A territory mapping method (Sutherland 1996; Bibby et al. 2012) has been applied to assess population densities of shrike (Lanidae) and bush shrike (Malaconotidae) species breeding in the study area. Field observations were aided with binocular 10 x 50.

Four surveys of the whole area were conducted in each year. In 2012 the first survey was conducted in the first half of November, the second survey in the second half of November, the third survey in the first half of December and the fourth one in the second half of December. In 2017, the first survey was conducted in the first half of February, second survey in the second half of February, third survey in the first half of March, and the fourth one in the second half of March. In 2020, the timing of surveys was as in 2017.

Since the study plot was too large to survey it within one morning, 4-5 morning counts were required to complete the survey of the whole study plot. Birds calling and showing other territorial or breeding behaviour (especially important were calling and singing birds) were identified to species and plotted on the map. Noted were the number of birds observed, their sex and kind of perforemd behaviour. A caution was taken to not register the same individuals by noting movements of birds in the field and by paying special attention to birds simultaneously calling at the same time.

At least two records of a given species in a clump were required to distinguish an occupied territory (Bibby et al. 2012). However, if nest with eggs or chicks were find, one record was sufficient. Each occupied territory was assumed as being an eqivalent of one breeding pair. Population density was expressed as the number of breeding pairs per 100 ha. The study plot consisted a mosaic of natural, and transformed acacia savanna habitat. In order to measure selectivity of natural versus transformed habitats, each mapped territory was classified to three groups: a) covering mostly or entirely natural habitat; b) covering mostly or entirely transformed habitat; c) covering approximately equal proportion of natural and transformed habitats. Philopatry was determined by counting territories held in the same site, partly in the same sites, and in different sites in two compared years (2012 vs. 2017, 2012 vs. 2020 and 2017 vs. 2020).

3. Results

In 2012-2020, one shrike and four bush shrike species were recorded as breeding in the study plot: Southern White-crowned Shrike

Eurocephalus auguitimens from the family Laniidae, and 4 species from the family Malaconotidae: Crimson-breasted Shrike

Laniarius atrococcineus, Brubru

Nilaus afer, Black-backed Puffback

Dryoscopus cubla, and Brown-crowned

Tchagra Tchargra australis. The least common was the Brubru and the White-crowned Shrike, each species with a population density below 1 pair per 100 ha in all seasons. The most abundant was the Black-backed Puffback and Crimson-breasted Shrike, reaching a density of 2.5 pairs per 100 ha and 1.9 pairs per 100 ha respectively (

Table 2).

While the density of the Brown-crowned Tchagra and Brubru remained stable over the years, the population densities of the Black-backed Shrike, Crimson-breasted Shrike and Southern White-crowned Shrike showed a remarkably increase over the years 2012-2020 (

Table 2).

All bush-shrike species showed a preference for patches of natural savanna vegetation. This was especially evident in the Crimson-breasted Shrike and the Brubru. However, the White-crowned Shrike did not show such preferences (

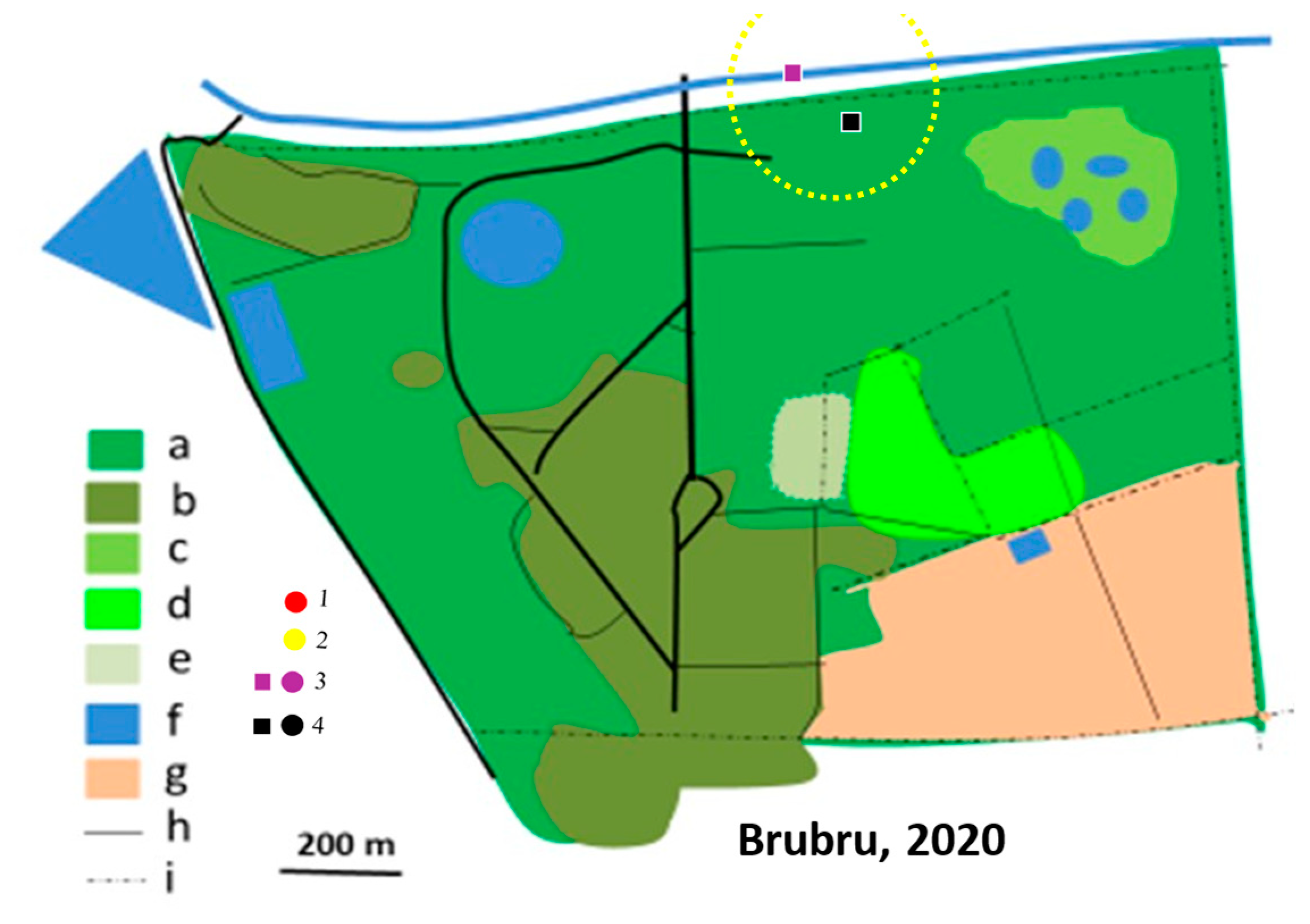

Table 3). Most Crimson-breasted Shrike, Black-backed Shrike and Black-crowned Tchagra territories were in the same or nearly the same sites in the year 2012, 2017 and 2020 (

Table 4), which suggest fairly high degree of philopatry. Due to a low sample size the differences are however not significant statistically.

In 2012, most territories of the Brown-crowned Tchagra and the Crimson-breasted Shrike remained separated, while only single territories of two other species were established (

Figure 4). In 2017, most territories of the Black-backed Puffback excluded Crimson-breasted Shrike territories. The Brubru territories partly overlapped with the Black-backed Puffback territories, but excluded Crimson-breasted Shrike ones. The Southern White-crowned territory excluded territories of all other shrikes and bush-shrikes (

Figure 4). In 2020, the overall density of shrikes and bush-shrikes in Ogongo was twice higher than in 2012 and 2017 (

Table 1). Crimson-breasted Shrike territories excluded six Black-backed Puffback territories, but remaining five overlapped to lesser or greater extend (

Figure 6). The Brown-crowned Tchagra territories completely excluded these of the White-crowned Shrike (

Figure 6). Territories of the latter species overlap with those of the Black-backed Puffback, but excluded territories of the Crimson-breasted Shrike.

Table 2.

Population densities (pairs/100 ha) of shrike and bush-shrike species in Ogongo. n – number of breeding pairs, d – density (pairs per 100 ha).

Table 2.

Population densities (pairs/100 ha) of shrike and bush-shrike species in Ogongo. n – number of breeding pairs, d – density (pairs per 100 ha).

| Species |

2012 |

2017 |

2020 |

| n |

d |

n |

d |

n |

d |

| White-crowned Shrike Eurocephalus auguitimens

|

0 |

0 |

0.5 |

0.13 |

3 |

0.75 |

| Crimson-breasted Shrike Laniarius atrococcineus

|

4 |

1 |

5 |

1.25 |

7.5 |

1.88 |

| Brubru Nilaus afer

|

1 |

0.25 |

2 |

0.50 |

0.5 |

0.13 |

| Black-backed Puffback Dryoscopus cubla

|

1 |

0.25 |

6 |

1.50 |

10 |

2.50 |

| Brown-crowned Tchagra Tchagra australis |

6 |

1.5 |

0 |

0 |

4 |

1.00 |

| Total |

12 |

3.0 |

13.5 |

3.38 |

25 |

6.26 |

Table 3.

Number of territories of shrike and bush-shrike species established in natural vs. transformed savanna.

Table 3.

Number of territories of shrike and bush-shrike species established in natural vs. transformed savanna.

| Species |

Natural savanna |

Partly natural/ partly transformed |

Transformed savanna |

| |

n |

% |

n |

% |

n |

% |

| White-crowned Shrike |

1 |

0.33 |

1 |

0.33 |

1 |

0.33 |

| Crimson-breasted Shrike |

16 |

94.1 |

1 |

5.9 |

0 |

0.0 |

| Brubru |

3 |

100 |

0 |

0.0 |

0 |

0.0 |

| Black-backed Puffback |

5 |

62.5 |

2 |

25 |

1 |

12.5 |

| Brown-crowned Tchagra |

7 |

70 |

2 |

20 |

1 |

10 |

Table 4.

Philopatry in shrikes. Number of territories held in the same site (T), partly the same (P) and in different sites (N) in two compared years.

Table 4.

Philopatry in shrikes. Number of territories held in the same site (T), partly the same (P) and in different sites (N) in two compared years.

| Species |

2012 vs. 2017 |

2012 vs. 2020 |

2017 vs. 2020 |

Total |

| T |

P |

N |

T |

P |

N |

T |

P |

N |

T |

P |

N |

| White-crowed Shrike |

- |

- |

- |

- |

- |

- |

0 |

0 |

1 |

0 |

0 |

1 |

| Crimson-breasted Shrike |

0 |

2 |

2 |

1 |

1 |

2 |

2 |

2 |

1 |

3 |

5 |

5 |

| Brubru |

1 |

0 |

0 |

0 |

0 |

1 |

0 |

0 |

1 |

1 |

0 |

2 |

| Black-backed Puffback |

0 |

1 |

0 |

0 |

1 |

0 |

3 |

1 |

2 |

3 |

3 |

2 |

| Brown-crowned Tchagra |

- |

- |

- |

0 |

4 |

0 |

- |

- |

- |

0 |

4 |

2 |

| Total |

1 |

3 |

2 |

1 |

5 |

3 |

5 |

3 |

4 |

7 |

12 |

12 |

Figure 6.

Distribution of Brubru territories in Ogongo in 2012, 2017 and 2020.

Figure 6.

Distribution of Brubru territories in Ogongo in 2012, 2017 and 2020.

Figure 6.

Shike territories in 2012, 2017 and 2020. 1 – Black-backed Puffback, 2 – Southern White-crowned Shrike, 3 – Brubru, 4 – Crimson-breasted Shrike, 5 – Brown-crowed Tchagra.

Figure 6.

Shike territories in 2012, 2017 and 2020. 1 – Black-backed Puffback, 2 – Southern White-crowned Shrike, 3 – Brubru, 4 – Crimson-breasted Shrike, 5 – Brown-crowed Tchagra.

4. Discussion

Data on population densities of African shrikes and bush-shrikes are available only from one biome, woodland (Hockey et al. 2005). As expected, the population densities are, in overalll, higher in the woodland than those recorded in savanna (this study). This remains true also in rgard to particular species occupying both biomes. Probable reason for this these differences in population densities is the fact that forest is more productive than savanna in the same geographic region (Smith 1996).

The Brubru occurs all over Namibia (SABAP2). It is shy and unobtrusive, but strongly territorial species; pairs are duetting while advertising territory boundaries (Browie 2005a). Mean territory size ranged from 33 to 42 ha (Tarboton 1980). In broad-leaved woodland in the Limpopo province, South Africa, it nested at a density of 2-3 pairs/100 ha (Tarboton 1980), which is higher than the density recorded in this study (

Table 1) or in Kasane, NE Botswana (Kopij 2018).

The Black-backed Puffback is sparsely distributed in the northern half of Namibia (SABAP2). It is strongly territorial, actively advertising its territory with a distinct song (Dean 2005b). In the broad-leaved woodland in Limpopo it nested at a density of 2.4 p./100 ha (Tarboton 1980). It is therefore similar to that recorded in this study (2.5 p./100 ha) and in Kasane, (3.0 p./100 ha; Kopij 2018) .

The Brown-crowned Tchagra occur all over Namibia north of the Capricorn (SABAP2). It is also strongly territorial, fairly noisy and conspicuous (Browie 2005b). In the broad-leaved woodland in Limpopo, 4 p./100 ha were recorded (Tarboton 1980), which is much higher than in this study (1.0 p./100 ha) and in Kasane (1.3 p./100 ha; Kopij 2018)

The Crimson-breasted Shrike was recorded all over Namibia, except for the deserts (SABAP2). It is strongly territorial and vocal (Browie 2005c). In acacia woodland in Nylsvlei, Limpopo Province, 8 p./100 ha were recorded (Tarboton 1980), which is much higher than in present study (1.9 p./100 ha).

The Southern White-crowned Shrike was the only true shrike species in the study area. It occurs only in the northern half of Namibia, except deserts. It is territorial, conspicuous and noisy, and often it breeds cooperatively (Dean 2005a). To date, no data on population density of this species were available.

Only the Black-backed Puffback had in Ogongo density comparable to that recorded in the natural savanna in Limpopo (Tarboton 1980). Other bush-shrikes reached in natural savanna in Limpopo much higher densities than those recorded in this study. As shown also in this study, bush-shrike species show a strong preference for natural vegetation, most of which has been modified or transformed in Ogongo (this study), hence their population densities were lower there if compared with natural savanna in Limpopo (Tarboton 1980).

Population densities of bush-shrikes are much higher in acacia savanna than in neighbouring mopane savanna (

Table 4). The densities of the selected shrike and bush-shrike species are also much higher in savanna than in grasslands (

Table 4). In grasslands two other shrike species, the Common Fiscal

Lanius collaris and Bokmakierie

Telophorus zeylonus, are common and even dominated in avian communities (Kopij 2001, 2006, 2019b). The only bush-shrike species which appears to be not affected by habitat alternations is the Black-backed Puffback. The highest population density recorded for this species was in the urbanized habitat of Kasane (Kopij 2018).

Interspecific territoriality in birds is expected: a) between species that prey on large, ground-dwelling arthropods by preying from a vantage point; b) between ground-foraging species; c) between rapros preying on small mammals; d) between species foraging on tree bark (Orian & Wilson 1964). Shrikes belong to the first group, as their main diet includes large ground-dwelling invertebrates and small vertebrates hunted from a perching site (Hockey et al. 2005; Brown et al. 2020). The presented study suggests the occurrence of interspecific competition between some of them. It is probably an adaptive response to resource competition and reproductive interference. Within families, it may shape both resource competition or mate competition, while between families – it may shap resource competition only (Drury et al. 2020).

The presented study suggests that shrikes show relatively high degree of philopatry (

Table 3). In the study area, many territories were shifted to other places, from year to year, but this may not necessary indicate low philopatry. The degree of philopatry may be even higher than the overlapping territories indicate (

Figure 6). The applied method is, however, not the best way to study philopatry, as particular individuals are not recognizable. More robust data can be obtained with colour-ringed birds.

Little is known about the philopatry in shrikes (Harries & Franklin 2000). In the Lesser Grey Shrike Lanius minor, a long-distance migrant, 30% (97/319) of the nests were built in the same nest tree in successive years and more than half (183/319 = 57.4%) of the nests were in the same or neighboring trees (up to 20 m). However very seldom the nest were built by the same individuals (Krištín et al. 2007). In the Loggerhead Shrikes Lanius ludovicianus in North America, 14% of adult birds were philopatric; so low probably because high winter mortality (Haas & Sloane 1989). In two sympatric migratory shrike species in Japan, the Bull-headed Shrike Lanius bucephalus and Brown Shrike L. cristatus the philopatry was low in the previous (18% males, 0% females), but high in the latter species (43% males and 13% of females) (Takagi 2003).

Takagi (2003) suggested that the philopatry should be higher in habitat specialists compared to habitat generalists. Weatherhead & Forbes (1994) have shown, on the other hand, that migratory passerines are characterized by a low natal philopatry compared to resident passerines. Zimmerman & Finck (1989) suggest that a degree of the philopatry is related to the previous reproductive success of particular pair: the higher reproductive success the higher the philopatry. The shrikes in the presented study can be classified as food specialists. They prey mostly on larger arthropods collected from the ground, they are restricted mainly to acacia savanna, and they are all residents (Harris & Franklin 2000; Hockey et al. 2005, Brown et al. 2020). It is therefore not surpriing to find that shrikes and bush shrikes in the presented study displayed relatively high level of the philopatry.

Table 5.

Population densities (pairs/100 ha) of shrike species in Ogongo compared with other sites in Namibia.

Table 5.

Population densities (pairs/100 ha) of shrike species in Ogongo compared with other sites in Namibia.

| Species |

A |

B |

C |

D |

E |

| White-crowned Shrike |

0.8 |

0.2 |

0 |

0 |

0 |

| Crimson-breasted Shrike |

1.9 |

0.5 |

0 |

0 |

0.3 |

| Brubru |

0.0 |

0.4 |

1.2 |

0 |

<0.1 |

| Black-backed Puffback |

2.5 |

0.2 |

1.2 |

5.0 |

0 |

| Brown-crowned Tchagra |

1.0 |

0.7 |

0 |

0 |

<0.1 |

5. Conclusions

Shrikes and bush-shrikes as strongly territorial birds constitute convenient objects of studies on population density, territoriality, and philopatry. The presented studies shown marked interspecific differences in these behaviours. Furthermore, even within the same species, marked temporal differences were shown in population density and probably also in philopatry. These variations are probably adaptive responses to resource competition and reproductive interference. Further studies, with marked individuals, are required to better elucidate these aspects of behavioural ecology in diffenert habitats.

Funding

This research received no external funding.

Conflicts of Interest

The authors declare no conflicts of interest.

References

- Bauer, H.-G.; Berthold, P. Die Brutvögel Mitteleuropas. Bestand und Gefährdung. Alua-Verlag: Wiesbaden, 1997.

- Bibby, C.J.; Burgess, N.D.; Hill, D.A. Bird censuses techniques. Academic Press: London, 2012.

- BirdLife International. Birds in Europe: population estimates, trends and conservation status. BirdLife International: Cambridge (UK), 2004.

- Brown, L.; Fry, C.H.; Keith, S; Newman, K.B.; Urban, E.K. The birds of Africa. Vol. 1-7. Bloomsbury Publishing, 2020.

- Brown, P.E.; Davies, M.G. Reed-warblers. Foy: East Molesey, Surrey (U.K.), 1949.

- Browie, R.C.K. Brubru Nilaus afer. In: Hockey, P.A.R.; Dean, W.R.J.; Ryan, P.; Maree, S. (eds.). Roberts’ birds of southern Africa. John Voelcker Bird Book Fund, Cape Town, 2005a; p. 688-690.

- Browie, R.C.K. 2005b. Brown-crowned Tchagra Tchagra australis. In: Hockey, P.A.R.; Dean W.R.J.; Ryan, P.G.; Maree S. (eds.). Roberts’ birds of southern Africa. Cape Town: John Voelcker Bird Book Fund, 2005; p. 693-694.

- Browie, R.C.K. 2005c. Crimson-breasted Shrike Laniarius atrococcineus. In: Hockey P. A. R., Dean W. R. J., Ryan P. G., Maree S. (eds.). Roberts’ birds of southern Africa. John Voelcker Bird Book Fund, Cape Town, 2005; p. 699-700.

- Cody, M.L. Habitat selection and interspecific territoriality among the sylviid warblers of England and Sweden. Ecological Monographs 1978, 48, 351–396. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Combs, C.J.F. Observations on the rook Corvus frugilegus in southwest Cornwall. Ibis 1960, 102, 394–419. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Coulson, J.C. A review of philopatry in seabirds and comparisons with other waterbird species. Waterbirds 2016, 39, 229–240. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Cramp, S. (ed.). Handbook of the Birds of Europe, the Middle East and North Africa. Vol. 1-9. Oxford University Press: Oxford, 1977-1994.

- Dean, W.R.J. 2005a. White-crowned Shrike Eurocephalus auguitimens. In: Hockey P. A. R., Dean W. R. J., Ryan P. G., Maree S. (eds.). Roberts’ birds of southern Africa. John Voelcker Bird Book Fund: Cape Town, 2005a; p. 730-731.

- Dean, W.R.J. Black-backed Puffback Dryoscopus cubla. In: Hockey P. A. R., Dean, W.R.J.; Ryan, P.G.; Maree, S. (eds.) (2005): Roberts’ birds of southern Africa. John Voelcker Bird Book Fund: Cape Town, 2005b; p. 90-91.

- del Hoyo, J.; Elliott, A.; Christie, D.A. (eds.). Handbook of Birds of the World. Vol. 1-16. Lynx Edicions: Barcelona, 1992-2011.

- Drury, J.P.; Cowen, M.C.; Grether, G.F. Competition and hybridization drive interspecific territoriality in birds. Proceedings of the National Academy of Sciences 2020, 117, 12923–12930. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Glutz von Blotzheim, U.N. (eds.). Handbuch der Vögel Mitteleuropas. Vol. 1-15. Aula-Verlag: Wiesbaden, 1966-1996.

- Haas, C.A.; Sloane, S.A. Low return rates of migratory Loggerhead Shrikes: winter mortality or low site fidelity? The Wilson Bulletin, 1989, 101, 458–460. [Google Scholar]

- Harries, T.; Franklin, K. Shrikes and Bush-shrikes. Christopher Helm: London, 2000.

- Hockey, P.A.R.; Dean, W.R.J.; Ryan, P.G.; Maree, S. (eds.). Roberts’ birds of southern Africa. John Voelcker Bird Book Fund: Cape Town, 2005.

- Hoffman, M.T.; Schmiedel, U.; Jurgens, N. (eds.). Biodiversity in southern Africa. Volume 3: Implications for land use and management. Klaus Hess Publishers: Gottingen & Windhoek, 2010.

- Hoi, H.; Eichler, T.; Dittami, J. Territorial spacing and interspecific competition in three species of reed warblers. Oecologia, 1991, 87, 443–448. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Jurgens, N.; Haarmeyer, D.H.; Luther-Mosebach, J.; Dengler, J.; Finck, H.M.; Schmiedel, U. (eds.). Biodiversity in southern Africa. Volume 1: Patterns at local scale the BIOTA Observatories, Klaus Hess Publishers: Gottingen & Windhoek, 2010.

- Kangombe, F.N. Vegetation description and mapping of Ogongo Agricultural College and the surrounds with the aid of satellite imagery. B.Sc. thesis. University of Pretoria: Pretoria, 2007.

- Kolberg, H. Annotated checklist of the birds of Namibia. Lanioturdus 2022, 55(5), 1–99. [Google Scholar]

- Kopij, G. Atlas of Birds of Bloemfontein. Department of Biology, National University of Lesotho/Free State Bird Club: Roma. (Lesotho)/Bloemfontein (RSA), 2001.

- Kopij, G. The Structure of Assemblages and Dietary Relationships in Birds in South African Grasslands. Wydawnictwo Akademii Rolniczej we Wrocawiu, Wrocław, 2006.

- Kopij, G. Atlas of breeding birds of Kasane. Babbler 2018, 64, 3–15. [Google Scholar]

- Kopij, G. Structure of avian communities in a mosaic of built-up and semi-natural urbanised habitats in Katima Mulilo town, Namibia. Welwitschia International Journal of Agricultural Sciences, 2019, 1, 68–75. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Kopij, G. Structure of breeding bird community along the urban gradient in a town on Zambezi River, northeastern Namibia. Biologija 2020a, 66, 1–9. [Google Scholar]

- Kopij, G. Changes in the structure of avian community along a moisture gradient in an urbanized tropical riparian forest. Polish Journal of Ecology 2020b, 68, 251–262. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Kopij, G. Population densities of selected bird species in the city of Windhoek, Namibia. Berkut 2022b, 31(1/2), 40-47.

- Kopij, G. Status, distribution and numbers of birds in the Ogongo Game Park, north-central Namibia. Namibian Journal of Environment 2023, 7B, 9–20. [Google Scholar]

- Krištín, A.; Hoi, H.; Valera, F.; Hoi, C. Philopatry, dispersal patterns and nest-site reuse in Lesser Grey Shrikes (Lanius minor). Biodiversity and Conservation 2007, 16, 987–995. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Losin, N.; Drury, J.P.; Peiman, K.S.; Storch, C.; Grether, G.F. The ecological and evolutionary stability of interspecific territoriality. Ecology letters 2016, 19, 260–267. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Mendelsohn, J.; Jarvis, A.; Roberts, C.; Robertson, T. Atlas of Namibia. A Portrait of the Land and its People. Sunbird Publishers, Cape Town, 2009.

- Mendelsohn, J.; el Obeid, S.; Roberts, C. A profile of north-central Namibia. Gamsberg Macmillan Publishers, Windhoek, 2000.

- Mendelsohn, J. , Weber, B.. The Cuvelai Basin, its water and people in Angola and Namibia. Occasional Paper no. 8. Development Workshop, Luanda, 2011.

- Murray Jr., B. G. Interspecific territoriality in Acrocephalus: a critical review. Ornis Scandinavica, 1988, 19, 309–313. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Orians, G.H.; Willson, M.F. Interspecific territories of birds. Ecology 1964, 45, 736–745. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Pasinelli, G.; Müller, M.; Schaub, M.; Jenni, L. Possible causes and consequences of philopatry and breeding dispersal in red-backed shrikes Lanius collurio. Behavioral Ecology and Sociobiology 2007, 61, 1061–1074. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Reed, T.M. Interspecific territoriality in the chaffinch and great tit on islands and the mainland of Scotland: playback and removal experiments. Animal Behaviour 1982, 30, 171–181. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Schmiedel, U.; Jurgens, N. (eds.). Biodiversity in southern Africa. Volume 2: Patterns and processes at regional scale. Klaus Hess Publishers, Gottingen & Windhoek, 2010.

- Simmons, K. E. L. Interspecific territorialism. Ibis 1951, 93, 407–413. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Smith, R.L. Ecology and Field Biology. 5th ed. Addison Wesley Longman: Menlo Park (USA: CA), 1996.

- Takagi, M. Philopatry and habitat selection in Bull-headed and Brown shrikes. Journal of Field Ornithology 2003, 74, 45–52. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Tarboton, W.R. Avian populations in Transvaal savanna. Proceedings IV Pan-African Ornithological Congress, 1980; p. 113-124.

- Tucker, G.M.; Heath, M.F. Birds in Europe: their conservation status. BirdLife International: Cambridge (UK), 1994.

- Weatherhead, P.J.; Forbes, M.R. Natal philopatry in passerine birds: genetic or ecological influences? Behavioral Ecology 1994, 5, 426–433. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Wilson, K.A. Owl studies at Ann Arbor, Mich. Auk 1938, 55, 187–197. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Zimmerman, J.L.; Finck, E.J. Philopatry and correlates of territorial fidelity in male Dickcissels. North American Bird Bander 1989, 14. [Google Scholar]

|

Disclaimer/Publisher’s Note: The statements, opinions and data contained in all publications are solely those of the individual author(s) and contributor(s) and not of MDPI and/or the editor(s). MDPI and/or the editor(s) disclaim responsibility for any injury to people or property resulting from any ideas, methods, instructions or products referred to in the content. |

© 2025 by the author. Licensee MDPI, Basel, Switzerland. This article is an open access article distributed under the terms and conditions of the Creative Commons Attribution (CC BY) license (https://creativecommons.org/licenses/by/4.0/).