1. Introduction

Maintaining sufficient alveolar ridge height and width is critical for preserving natural teeth, enabling successful prosthetic rehabilitation, and ensuring safe implant placement [

1]. However, the alveolar bone frequently undergoes significant resorption following periodontal disease progression, prolonged use of ill-fitting dentures, or extended periods after tooth extraction without intervention. This bone loss complicates prosthetic treatment and restricts the options for implant placement [

2].

Once resorbed, the alveolar bone does not regenerate spontaneously. To address this, various approaches, including autologous bone grafts and the application of bone sub-stitutes, have been developed to reconstruct alveolar defects [

3]. Nevertheless, during the bone regeneration process, the infiltration of soft tissue into the defect site can inhibit osteogenesis. This is largely because fibroblasts (FBs), derived from soft tissues, proliferate more rapidly than osteoblasts [

4,

5]. Consequently, preventing soft tissue invasion and preserving the regenerative space are critical prerequisites for successful bone aug-mentation [

6,

7].

Barrier membranes, a central component of the guided tissue regeneration (GTR) and guided bone regeneration (GBR) techniques, have been developed to selectively guide cellular repopulation and promote tissue-specific regeneration. GTR was first introduced in 1982 by Nyman et al. to facilitate periodontal regeneration by creating a space for periodontal ligament-derived cells to migrate, while GBR, introduced in 1988, specifically targets alveolar bone defects by encouraging osteoblast migration and simultaneously preventing soft tissue ingrowth [

8,

9,

10,

11].

Membranes used in GTR and GBR are broadly classified into non-resorbable and re-sorbable types [

12,

13]. Non-resorbable membranes, such as expanded polytetrafluoro-ethylene and titanium mesh, provide excellent space maintenance but require a second surgery for removal, which can cause patient discomfort and risks damaging newly formed tissues [

14,

15]. By contrast, resorbable membranes—primarily made of collagen or synthetic polymers like poly(lactic-co-glycolic acid) (PLGA)—biodegrade over time, eliminating the need for retrieval surgery and reducing patient morbidity [

16,

17,

18,

19].

Despite their advantages, conventional resorbable membranes face challenges, including uncontrolled degradation rates, insufficient mechanical strength, and potential immu-nogenicity associated with animal-derived materials. Therefore, the development of synthetic, biocompatible membranes with predictable resorption profiles has gained significant attention [

20,

21,

22].

Recently, a novel bilayer resorbable membrane composed of poly(L-lactic ac-id-co-ε-caprolactone) (P(LA/CL); PBM) has been introduced. PBM features a dual-layer structure: a smooth, solid outer layer designed to prevent soft tissue invasion and maintain space, and a porous inner layer that promotes tissue integration and supports osteogenesis. Furthermore, its slow degradation profile and elasticity make it suitable for large defect sites requiring prolonged healing periods [

23,

24,

25].

In this study, we aimed to evaluate the wound healing effects and biological performance of PBM compared to conventional PLGA membranes, focusing on soft tissue healing, bone regeneration, and cell–membrane interactions through comprehensive in vivo and in vitro analyses.

2. Materials and Methods

2.1. Materials

Two types of commercially available resorbable membranes were used in this study: a PLGA membrane (GC Membrane, GC Corporation, Tokyo, Japan) and a bilayer membrane composed of P(LA/CL) (PBM; Cytrans Elashield, GC Corporation). Both membranes were utilized in in vitro and in vivo experiments.

2.2. Cell Culture

Oral epithelial cells (OECs) and FBs were isolated from rat oral mucosa [

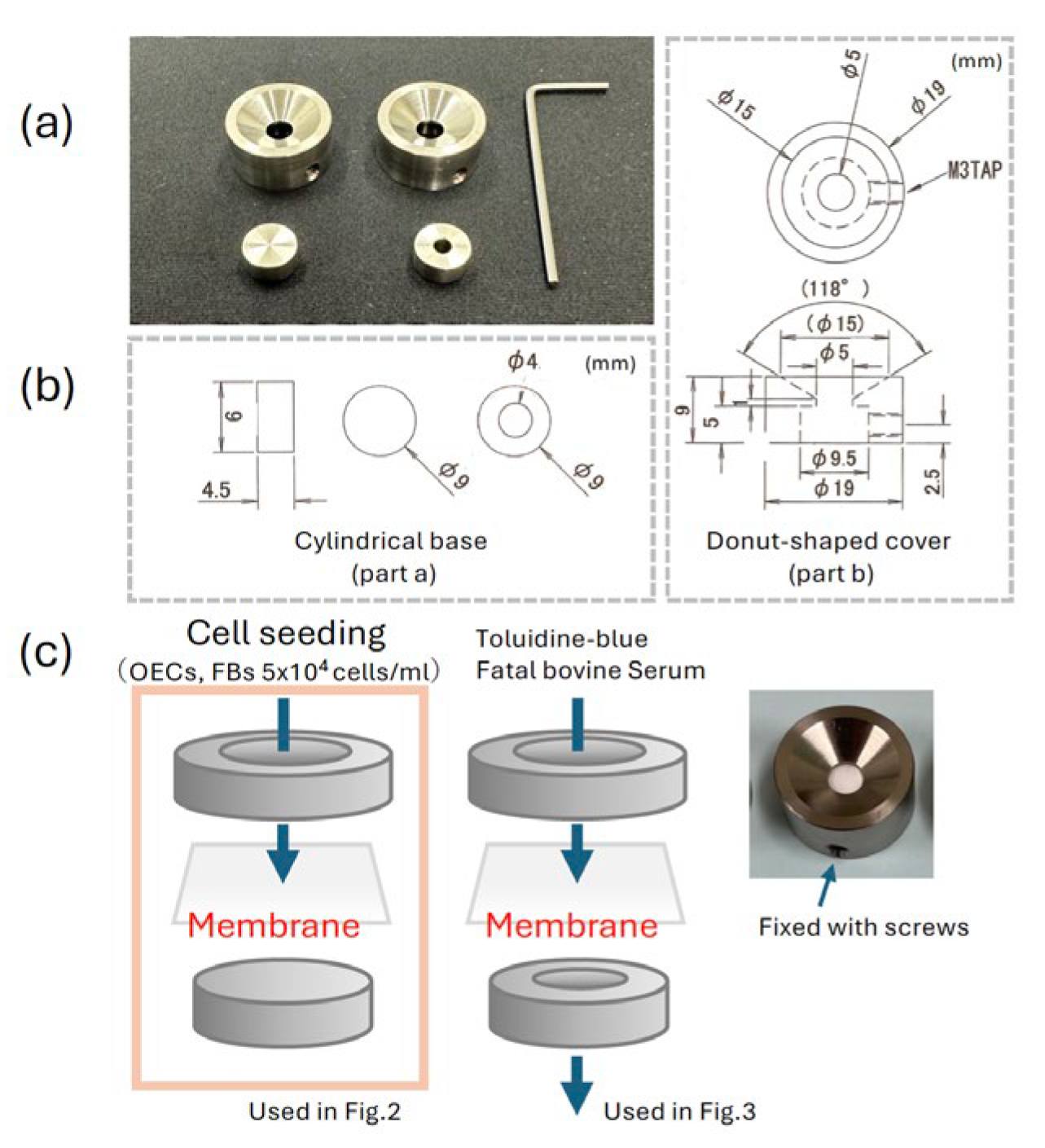

26]. Cells were seeded onto either the surface or the reverse side of each membrane at a density of 2 × 10⁴ cells/membrane. For seeding, a custom-designed titanium apparatus was used (

Figure 1). This device consisted of two parts: a cylindrical base (part a) supporting the membrane and a donut-shaped cover (part b), which is secured to the base by tightening side screws using a small hex wrench. This mechanism firmly locks the membrane in place, pre-venting displacement and ensuring that cells cannot pass underneath during culture. Cells were cultured under standard conditions (37°C, 5% CO₂) for 5 days prior to further analysis.

2.3. Scanning Electron Microscopy (SEM)

After 5 days of culture, cell morphology on the membranes was examined by SEM. Samples were fixed with 2.5% glutaraldehyde, dehydrated through a graded ethanol series, dried, sputter-coated with gold, and observed. In parallel, for quantification of adherent cells, membranes were treated with TrypLE Express (Thermo Fisher Scientific, MA, USA) to detach the cells, and the number of cells was counted using an automated cell counter (TC20, Bio-Rad, Tokyo, Japan) [

27].

2.4. Membrane Permeability Test

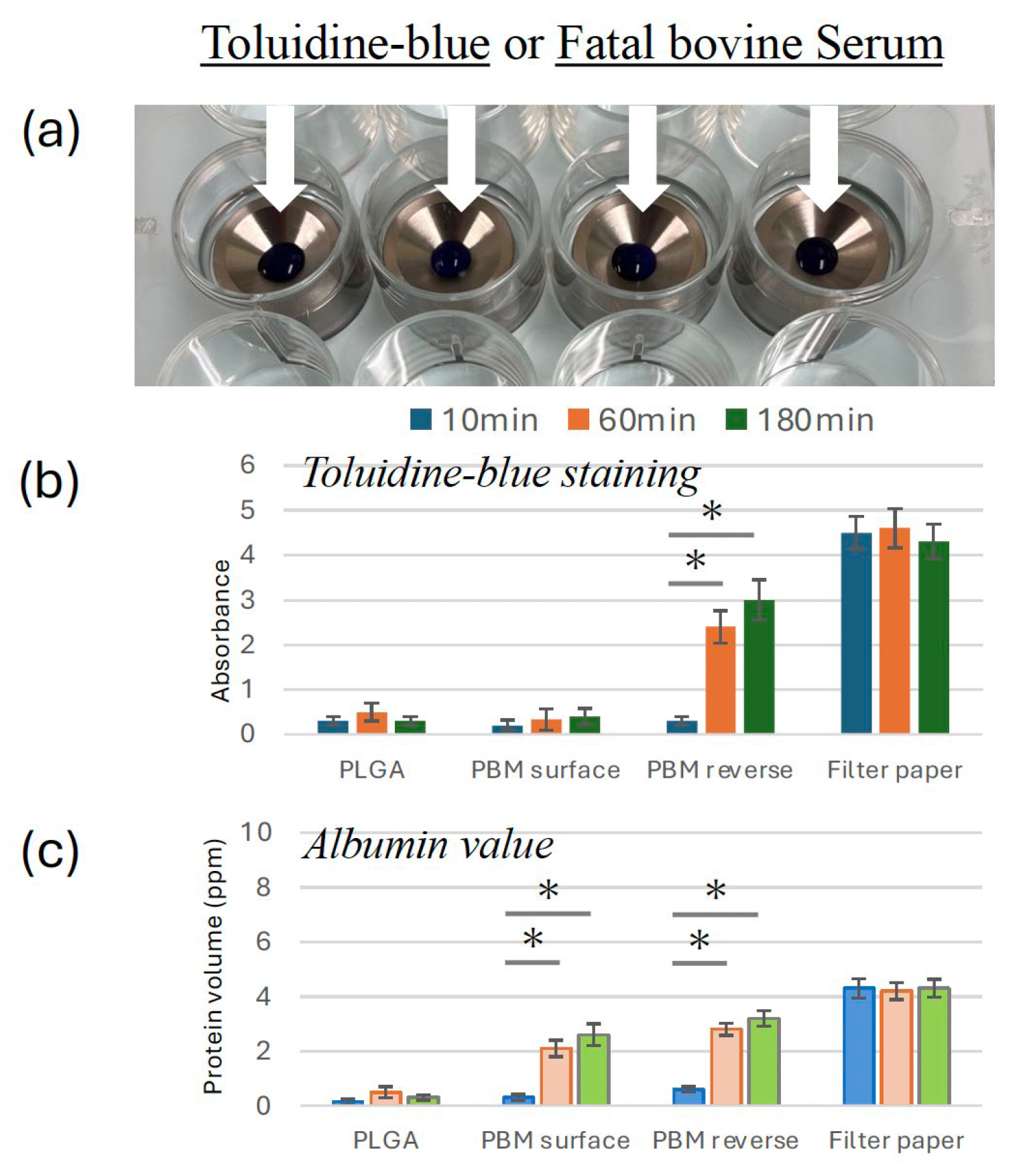

The permeability of membranes was assessed using a modified titanium apparatus de-signed to hold the membranes in place (

Figure 2a). Each membrane (PLGA and PBM surfaces, PBM reverse side, or filter paper as control) was mounted on the device, which was submerged in distilled water within a 12-well culture plate. Toluidine blue dye or fetal bovine serum (FBS) was applied onto the top of the membranes. After incubation, the degree of penetration was evaluated by determining the absorbance of the underlying water using a spectrophotometer.

2.5. Establishment of the Rat Membrane Model

Sixty male Wistar rats (6 weeks old, weight 130–160 g) were used for the in vivo model (Kyudo Co.) [

28]. Under general anesthesia, the maxillary right first and second molars were extracted. After extraction, the septum between the extraction sockets was removed using a round bur (CA φ1.0, Dentech, Tokyo, Japan). Each extraction socket was covered with either a PLGA or a PBM membrane. The membranes were sutured to the sur-rounding mucosa using 4-0 silk thread (two stitches per site) (

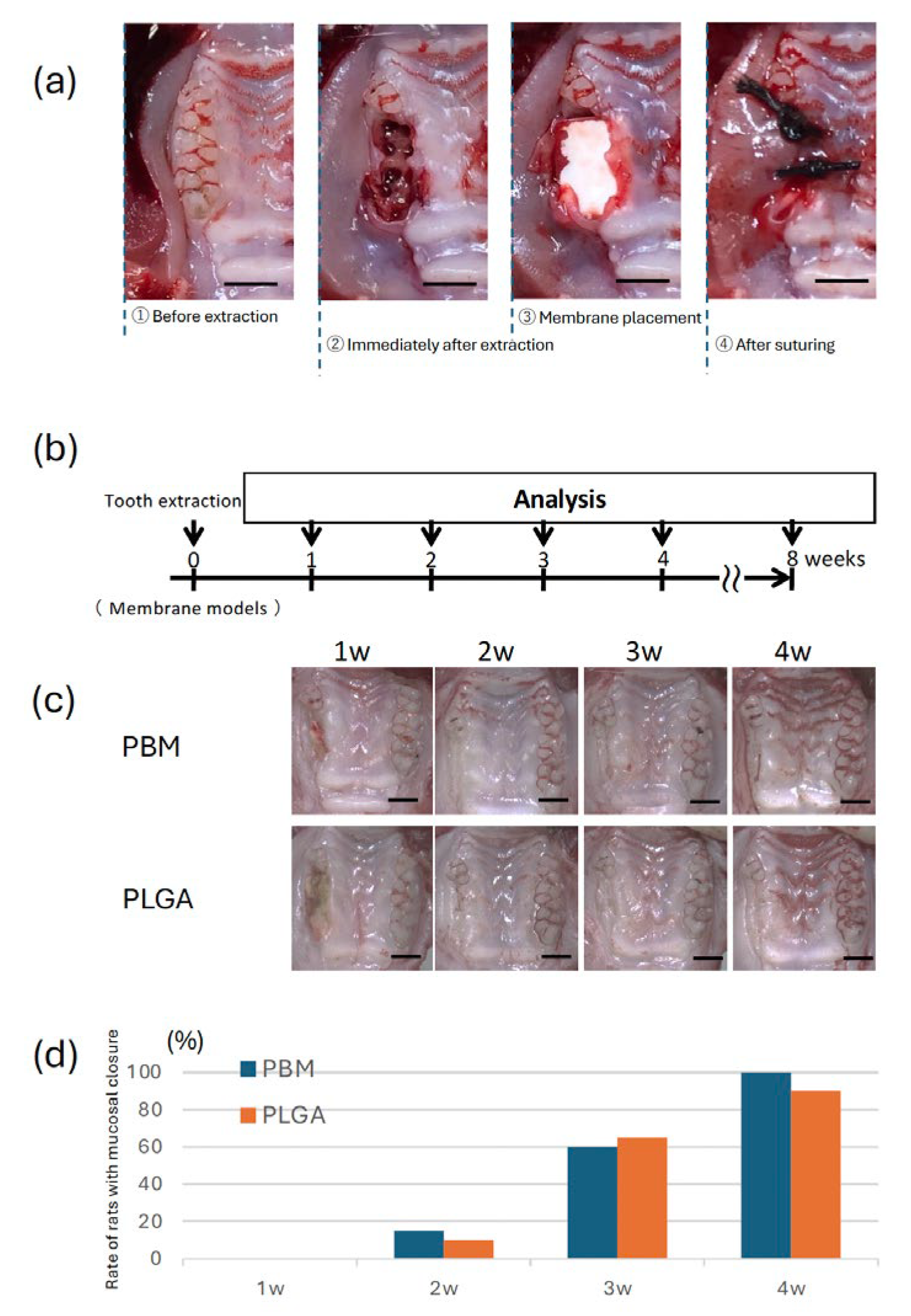

Figure 3a). Surgery was performed under systemic anesthesia (0.3 mg/kg medetomidine, 4.0 mg/kg midazolam, and 5.0 mg/kg butorphanol), and the animals were maintained in accordance with the guidelines approved by the Animal Care and Use Committee of Kyushu University (Approval Number: A25-240-0). Sutures were removed 3 days postoperatively.

2.6. Euthanasia and Sample Preparation

The experimental schedule is shown in

Figure 3b, at 1-4 and 8 weeks post-surgery, animals were euthanized by anesthesia overdose. Phosphate-buffered saline perfusion followed by Zamboni’s fixative perfusion was performed. The maxillae were harvested for further analysis. For macroscopic evaluation, specimens were observed using a ste-reomicroscope. For histological analysis, the specimens were trimmed to preserve the area of interest, fixed in 4% paraformaldehyde for 48h, and subsequently decalcified in Kalkitox™ solution (Wako, Osaka, Japan) at 4°C for 24 hours. After decalcification, samples were embedded in Optimal Cutting Temperature compound (Sakura Finetek, Tokyo, Japan) and cryosectioned at a thickness of 10 μm using a cryostat .

2.7. Micro-Computed Tomography (Micro-CT) Analysis

For radiographic assessment, micro-CT scanning was performed (SkyScan 1076, Bruker, Kontich, Belgium) at 49 kV tube voltage and 201 μA current, with a pixel size of 18 μm. Three-dimensional image reconstruction and bone volume quantification within the extraction sockets were performed using CTAn software (Bruker microCT) [

29].

2.8. Histological Analysis

Frozen sections were stained with hematoxylin and eosin and observed by light mi-croscopy to evaluate soft tissue healing and new bone formation beneath the membranes.

2.9. Statistical Analysis

Quantitative data were expressed as mean ± standard deviation. Statistical comparisons between groups were performed using one-way analysis of variance followed by Tukey’s post hoc test for multiple comparisons. A p-value of < 0.05 was considered to be statistically significant.

3. Results

3.1. Comparison of OEC and FB Adhesion on PBM Membrane Surfaces

Using a custom-designed titanium culture apparatus (

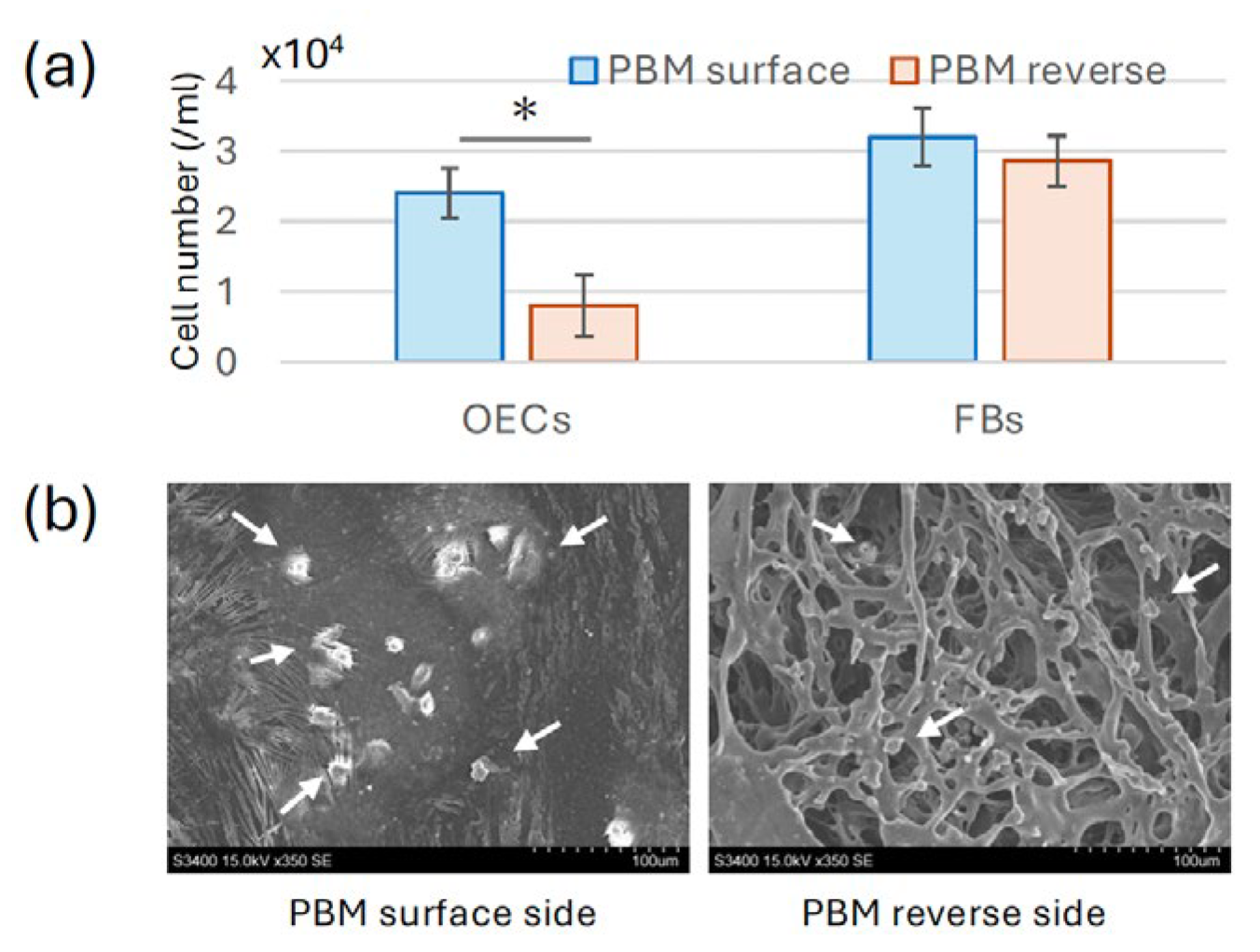

Figure 1), OECs and FBs were cultured separately on the surface and reverse sides of the PBM membrane. After 5 days of culture, OECs displayed extensive proliferation on the surface side of the PBM membrane, whereas only minimal adhesion was observed on the reverse side (

Figure 4a). Higher magnification SEM images confirmed numerous well-spread epithelial cells with extended lamellipodia on the surface side, whereas few cells were present on the reverse side (

Figure 4b). No notable differences in FB adhesion were observed between the two sides of the PBM membrane.

3.2. Permeability Differences Between Membranes

Toluidine blue dye and FBS permeability tests were conducted to evaluate membrane barrier properties. The PBM surface and PLGA effectively blocked dye and serum penetration (

Figure 2b and c). By contrast, the reverse side of the PBM membrane exhibited increased permeability over time, similar to that of the filter paper control.

3.3. Mucosal Wound Healing over Membranes

Gross examination showed progressive mucosal closure in both the PBM and PLGA groups (

Figure 3c). By 3 weeks postoperatively, complete mucosal closure was observed in almost all cases in both groups. Quantitative analysis revealed no statistically significant difference in the rate of mucosal closure between the two groups (

Figure 3d).

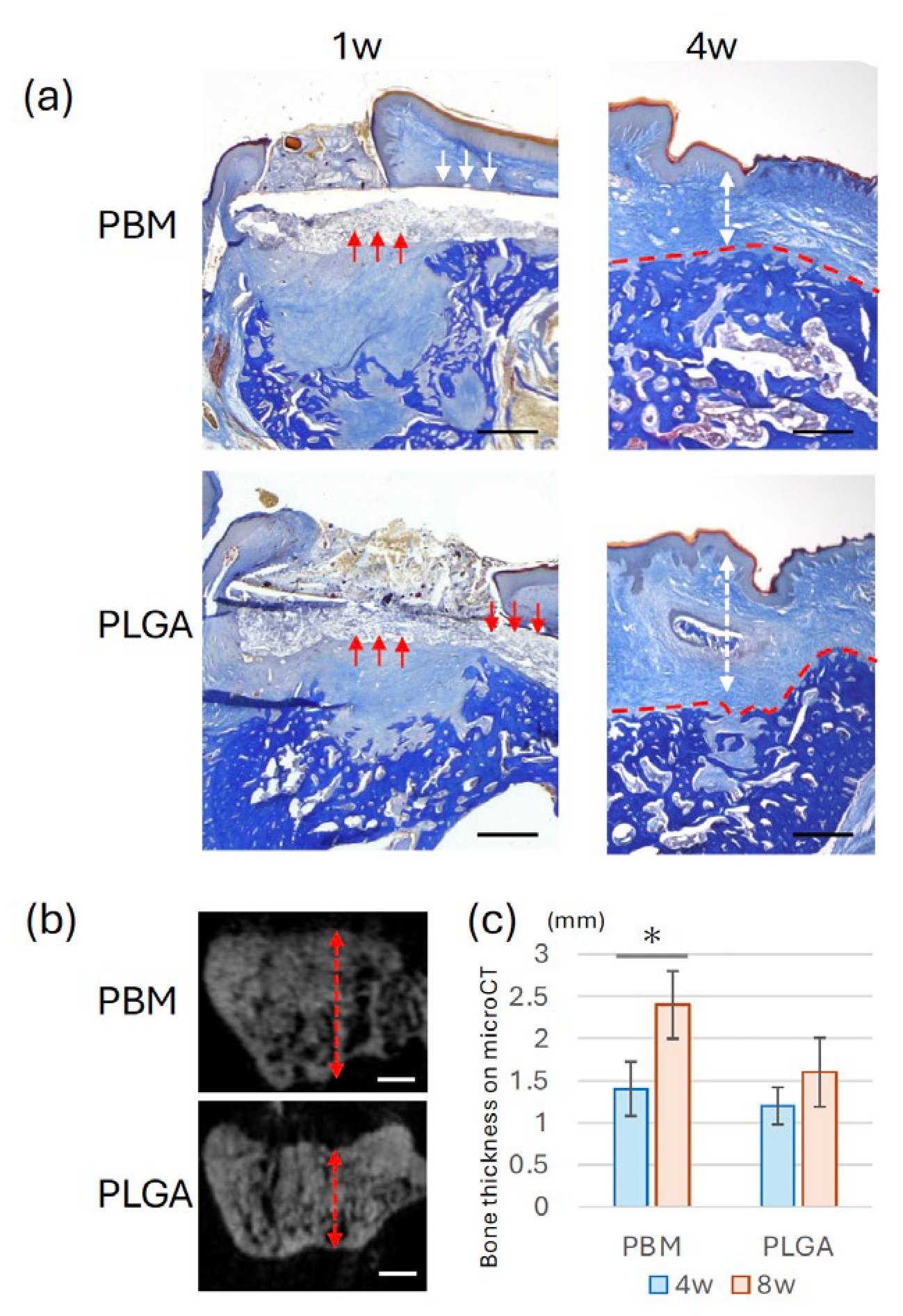

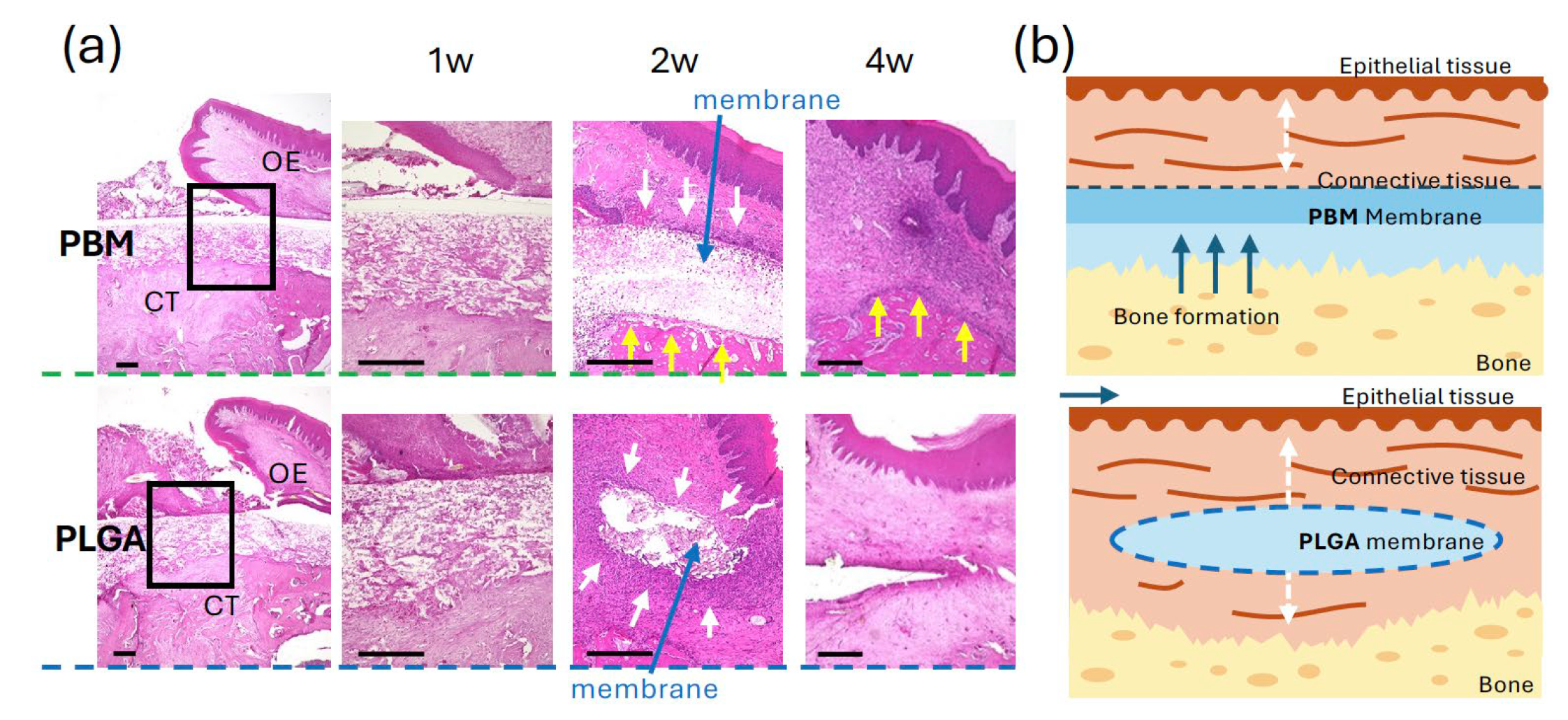

3.4. Bone Formation Beneath the Membranes

Histological analysis at 4 weeks demonstrated differences in the spatial relationship between the membrane and new bone (

Figure 5a). In the PBM group, newly formed bone appeared to extend along the membrane. In the PLGA group, a concave defect area was observed beneath the membrane. Micro-CT analysis confirmed these observations (

Figure 5b, 5c), bone thickness was significantly higher in the PBM group than in the PLGA. As shown in

Figure 6a, newly formed bone in the PBM group was observed in direct contact with the underside of the membrane. By contrast, the PLGA membrane was surrounded predominantly by connective tissue, with no direct bone contact.

4. Discussion

Cell adhesion experiments were performed only on the PBM membrane using a custom titanium apparatus. OECs displayed robust adhesion and spreading with extended lamellipodia on the surface side of PBM, whereas minimal attachment was observed on the reverse side. This indicated that the PBM’s surface side offers a favorable environment for epithelial cell adhesion, likely due to surface topography or hydrophilic properties. Rapid epithelial coverage is critical to prevent postoperative contamination and may support improved early-stage soft tissue healing [

30,

31]. The lack of adhesion on the reverse side also reflects the directional nature of PBM, emphasizing the importance of correct membrane orientation during surgical placement.

In the permeability assay using toluidine blue and FBS, both, the PBM and PLGA surface sides effectively prevented dye permeation. However, the reverse side of PBM exhibited high permeability comparable to filter paper. This finding underscores a functional limitation of the bilayer PBM design—although the solid surface layer provides strong barrier function, the porous reverse layer may allow undesirable molecular or cellular infiltration if placed incorrectly [

32,

33]. PLGA, by contrast, is a non-layered uniform membrane, and although permeability testing was limited to one side, it displayed consistent barrier performance. These differences highlight the need for precise membrane orientation when using bilayer membranes like PBM in GBR procedures.

Gross examination showed no statistically significant difference in the mucosal healing rate between the PBM and PLGA groups, with both achieving near-complete closure by week three. These results suggested that both materials exhibit adequate biocompatibility to support soft tissue closure. However, considering PBM’s favorable epithelial cell adhesion in vitro, it may offer advantages in more challenging healing environments or in mucosa-compromised patients [

34].

Histological and micro-CT evaluation revealed that the PBM group exhibited a larger amount of new bone formation within the extraction sockets compared to the PLGA group. In the PBM group, bone tissue filled the defect space more thoroughly, and a clear boundary was maintained between the membrane and the regenerating bone [

35]. This suggested that PBM functions effectively as a space maintainer, promoting osteogenesis while preventing collapse or early soft tissue invasion [

36,

37,

38].

Notably, as shown in

Figure 6, new bone was observed in direct contact with the underside of the PBM membrane, suggesting that the membrane surface provided a favorable scaffold for osteogenesis. By contrast, in the PLGA group, the membrane was frequently observed in close contact with connective tissue, and bone regeneration appeared less robust. This may reflect the PLGA membrane’s tendency to integrate with soft tissue earlier, leading to partial loss of regenerative space during the healing process [

39]. Taken together, these findings suggested that PBM’s bilayer structure—combining a solid barrier side with a tissue-friendly porous layer—may create an optimal environment for bone healing, provided that its orientation is correct [

40].

The study results suggested that PBM offers several clinical advantages:

Enhanced epithelial compatibility for early soft tissue sealing

Effective space maintenance for bone regeneration

Synthetic and fully resorbable, free from animal-derived components

However, the performance of PBM is strongly orientation-dependent. Incorrect placement could result in reverse-side exposure to soft tissues, leading to increased permeability and reduced barrier function. By contrast, PLGA membranes, though simpler and less supportive of epithelial attachment, offer a consistent barrier function regardless of placement direction, and may be preferable in cases where membrane orientation is difficult to maintain.

This study has several limitations. First, it used a small animal model with a limited bone defect size and rapid healing capacity, which may not replicate the challenges of human clinical GBR procedures. Second, only short-term healing (up to 4 weeks) was assessed. Long-term membrane degradation, integration, and bone quality outcomes remain unclear.

Future studies should:

Evaluate PBM performance in larger animal models with more complex defects

Investigate long-term space maintenance and bone maturation

Consider design improvements to enhance the barrier function of the reverse side

5. Conclusions

The synthetic bilayer PBM membrane exhibited favorable characteristics for maintaining bone-soft tissue separation and promoting wound healing. These results suggested that PBM may serve as an effective alternative to conventional resorbable membranes for GBR procedures. Further investigations are required to elucidate its long-term clinical applicability.

Author Contributions

Conceptualization, T.X. and I.A.; methodology, T.X. and B.J.; validation, I.A. and I.N.; formal analysis, T.X., I.A. and Y.J.; investigation, A.T.; resources, I.A. and M.I.; writing—original draft preparation, T.X. and I.A.; writing—review and editing, I.A., I. N., and B.J.; visualization, Y.J. and T.X.; supervision, K.K. and Y.A.; project administration, Y.A. All authors have read and agreed to the published version of the manuscript.

Funding

This research received no external funding.

Institutional Review Board Statement

The study was conducted according to the guidelines of the Declaration of Helsinki, and approved by the Animal Care and Use Committee of Kyushu University (Approval Number: A25-240-0).

Data Availability Statement

The data presented in this study are available on request from the corresponding author.

Conflicts of Interest

T.X., M.I., K.K. and Y.A. belong to the Division of Advanced Dental Devices and Therapeutics, Faculty of Dental Science, Kyushu University. This division is endowed by GC Corporation, Tokyo, Japan. GC Corporation had no specific roles in the conceptualization, design, data collection, analysis, decision to publish or preparation of the manuscript. All other authors declare that they have no competing interests.

Abbreviations

The following abbreviations are used in this manuscript:

| PBM |

Poly(L-lactic acid-co-ε-caprolactone) bilayer membrane |

| PLGA |

Poly(lactic-co-glycolic acid) |

| GBR |

Guided Bone Regeneration |

| GTR |

Guided Tissue Regeneration |

| OECs |

Oral Epithelial Cells |

| FBs |

Fibroblasts |

| FBS |

Fetal Bovine Serum |

| SEM |

Scanning Electron Microscopy |

| Micro-CT |

Micro-Computed Tomography |

| OCT |

Optimal Cutting Temperature (compound) |

| HE |

Hematoxylin and Eosin |

| OE |

Oral Epithelium |

| CT |

Connective Tissue |

References

- Benic, G. I.; Hämmerle, C. H. F. Horizontal Bone Augmentation by Means of Guided Bone Regeneration. Periodontology 2000 2014, 66(1), 13–40. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Liu, J.; Kerns, D. G. Mechanisms of Guided Bone Regeneration: A Review. Open Dent J 2014, 8, 56–65. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Miron, R. J. Optimized Bone Grafting. Periodontology 2000 2024, 94(1), 143–160. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Polimeni, G.; Xiropaidis, A. V.; Wikesjö, U. M. E. Biology and Principles of Periodontal Wound Healing/Regeneration. Periodontology 2000 2006, 41(1), 30–47. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Retzepi, M.; Donos, N. Guided Bone Regeneration: Biological Principle and Therapeutic Applications. Clinical Oral Implants Research 2010, 21(6), 567–576. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Buser, D.; Dahlin, C.; Schenk, R. K. Guided Bone Regeneration in Implant Dentistry; Quintessence Books, 1994.

- Cardaropoli, G.; Araújo, M.; Lindhe, J. Dynamics of Bone Tissue Formation in Tooth Extraction Sites. Journal of Clinical Periodontology 2003, 30(9), 809–818. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Nyman, S.; Lindhe, J.; Karring, T.; Rylander, H. New Attachment Following Surgical Treatment of Human Periodontal Disease. J Clin Periodontol 1982, 9(4), 290–296. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Dahlin, C.; Linde, A.; Gottlow, J.; Nyman, S. Healing of Bone Defects by Guided Tissue Regeneration. Plast Reconstr Surg 1988, 81(5), 672–676. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Melcher, A. H. On the Repair Potential of Periodontal Tissues. J Periodontol 1976, 47(5), 256–260. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Faria-Almeida, R.; Astramskaite-Januseviciene, I.; Puisys, A.; Correia, F. Extraction Socket Preservation with or without Membranes, Soft Tissue Influence on Post Extraction Alveolar Ridge Preservation: A Systematic Review. J Oral Maxillofac Res 2019, 10(3), e5. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Limitations and options using resorbable versus nonresorbable membranes for successful guided bone regeneration. Quintessenz Verlags-GmbH. https://www.quintessence-publishing.com/deu/en/article/841003 (accessed 2025-05-03).

- Scantlebury, T. V. 1982-1992: A Decade of Technology Development for Guided Tissue Regeneration. J Periodontol 1993, 64 Suppl 11S, 1129–1137. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Rakhmatia, Y. D.; Ayukawa, Y.; Furuhashi, A.; Koyano, K. Current Barrier Membranes: Titanium Mesh and Other Membranes for Guided Bone Regeneration in Dental Applications. Journal of Prosthodontic Research 2013, 57(1), 3–14. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Korzinskas, T.; Jung, O.; Smeets, R.; Stojanovic, S.; Najman, S.; Glenske, K.; Hahn, M.; Wenisch, S.; Schnettler, R.; Barbeck, M. In Vivo Analysis of the Biocompatibility and Macrophage Response of a Non-Resorbable PTFE Membrane for Guided Bone Regeneration. Int J Mol Sci 2018, 19(10), 2952. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Wang, H. A Review of the Effects of Collagen Treatment in Clinical Studies. Polymers (Basel) 2021, 13(22), 3868. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Radenković, M.; Alkildani, S.; Stoewe, I.; Bielenstein, J.; Sundag, B.; Bellmann, O.; Jung, O.; Najman, S.; Stojanović, S.; Barbeck, M. Comparative In Vivo Analysis of the Integration Behavior and Immune Response of Collagen-Based Dental Barrier Membranes for Guided Bone Regeneration (GBR). Membranes 2021, 11(9), 712. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Hoornaert, A.; d’Arros, C.; Heymann, M.-F.; Layrolle, P. Biocompatibility, Resorption and Biofunctionality of a New Synthetic Biodegradable Membrane for Guided Bone Regeneration. Biomed. Mater. 2016, 11(4), 045012. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Lyu, C.; Shao, Z.; Zou, D.; Lu, J. Ridge Alterations Following Socket Preservation Using a Collagen Membrane in Dogs. Biomed Res Int 2020, 2020, 1487681. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Sheikh, Z.; Najeeb, S.; Khurshid, Z.; Verma, V.; Rashid, H.; Glogauer, M. Biodegradable Materials for Bone Repair and Tissue Engineering Applications. Materials (Basel) 2015, 8(9), 5744–5794. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Sasaki, J.-I.; Abe, G. L.; Li, A.; Thongthai, P.; Tsuboi, R.; Kohno, T.; Imazato, S. Barrier Membranes for Tissue Regeneration in Dentistry. Biomater Investig Dent 8 (1), 54–63. [CrossRef]

- Wang, H.-L.; Boyapati, L. “PASS” Principles for Predictable Bone Regeneration. Implant Dent 2006, 15(1), 8–17. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Abe, G. L.; Sasaki, J.-I.; Katata, C.; Kohno, T.; Tsuboi, R.; Kitagawa, H.; Imazato, S. Fabrication of Novel Poly(Lactic Acid/Caprolactone) Bilayer Membrane for GBR Application. Dental Materials 2020, 36(5), 626–634. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Abe, G. L.; Sasaki, J.-I.; Tsuboi, R.; Kohno, T.; Kitagawa, H.; Imazato, S. Poly(Lactic Acid/Caprolactone) Bilayer Membrane Achieves Bone Regeneration through a Prolonged Barrier Function. J Biomed Mater Res B Appl Biomater 2024, 112(1), e35365. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Watanabe, T.; Hasuike, A.; Wakuda, S.; Kogure, K.; Min, S.; Watanabe, N.; Sakai, R.; Chaurasia, A.; Arai, Y.; Sato, S. Resorbable Bilayer Membrane Made of L-Lactide-ε-Caprolactone in Guided Bone Regeneration: An in Vivo Experimental Study. Int J Implant Dent 2024, 10(1), 1. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Atsuta, I.; Ayukawa, Y.; Furuhashi, A.; Narimatsu, I.; Kondo, R.; Oshiro, W.; Koyano, K. Epithelial Sealing Effectiveness against Titanium or Zirconia Implants Surface. J Biomed Mater Res A 2019, 107(7), 1379–1385. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Baumhammers, A.; Langkamp, H. H.; Matta, R. K.; Kllbury, K. Scanning Electron Microscopy of Epithelial Cells Grown on Enamel, Glass and Implant Materials. Journal of Periodontology 1978, 49(11), 592–597. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Zhang, X.; Atsuta, I.; Narimatsu, I.; Ueda, N.; Takahashi, R.; Egashira, Y.; Zhang, J.-Q.; Gu, J.-Y.; Koyano, K.; Ayukawa, Y. Replacement Process of Carbonate Apatite by Alveolar Bone in a Rat Extraction Socket. Materials (Basel) 2021, 14(16), 4457. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Adachi, N.; Ayukawa, Y.; Yasunami, N.; Furuhashi, A.; Imai, M.; Sanda, K.; Atsuta, I.; Koyano, K. Preventive Effect of Fluvastatin on the Development of Medication-Related Osteonecrosis of the Jaw. Sci Rep 2020, 10(1), 5620. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Simion, M.; Maglione, M.; Iamoni, F.; Scarano, A.; Piattelli, A.; Salvato, A. Bacterial Penetration through Resolut® Resorbable Membrane in vitroAbstract. Clinical Oral Implants Research 1997, 8(1), 23–31. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- L. Journal of Periodontal Research 2022, 57(3), 510–518. [CrossRef]

- Ku, Y.; Shim, I. K.; Lee, J. Y.; Park, Y. J.; Rhee, S.-H.; Nam, S. H.; Park, J. B.; Chung, C. P.; Lee, S. J. Chitosan/Poly(L-Lactic Acid) Multilayered Membrane for Guided Tissue Regeneration. Journal of Biomedical Materials Research Part A 2009, 90A (3), 766–772. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Hürzeler, M. B.; Quiñones, C. R.; Morrison, E. C.; Caffesse, R. G. Treatment of Peri-Implantitis Using Guided Bone Regeneration and Bone Grafts, Alone or in Combination, in Beagle Dogs. Part 1: Clinical Findings and Histologic Observations. Int J Oral Maxillofac Implants 1995, 10 (4), 474–484.

- Viateau, V.; Guillemin, G.; Calando, Y.; Logeart, D.; Oudina, K.; Sedel, L.; Hannouche, D.; Bousson, V.; Petite, H. Induction of a Barrier Membrane to Facilitate Reconstruction of Massive Segmental Diaphyseal Bone Defects: An Ovine Model. Vet Surg 2006, 35(5), 445–452. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Malchiodi, L.; Scarano, A.; Quaranta, M.; Piattelli, A. Rigid Fixation by Means of Titanium Mesh in Edentulous Ridge Expansion for Horizontal Ridge Augmentation in the Maxilla. Int J Oral Maxillofac Implants 1998, 13(5), 701–705. [Google Scholar] [PubMed]

- Shido, R.; Ohba, S.; Tominaga, R.; Sumita, Y.; Asahina, I. A Prospective Study of the Assessment of the Efficacy of a Biodegradable Poly(l-Lactic Acid/ε-Caprolactone) Membrane for Guided Bone Regeneration. Journal of Clinical Medicine 2023, 12(18), 5994. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Dimitriou, R.; Mataliotakis, G. I.; Calori, G. M.; Giannoudis, P. V. The Role of Barrier Membranes for Guided Bone Regeneration and Restoration of Large Bone Defects: Current Experimental and Clinical Evidence. BMC Med 2012, 10, 81. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Monje, A.; Pons, R.; Nart, J.; Miron, R. J.; Schwarz, F.; Sculean, A. Selecting Biomaterials in the Reconstructive Therapy of Peri-Implantitis. Periodontology 2000 2024, 94(1), 192–212. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Resorbable Membranes for Guided Bone Regeneration: Critical Features, Potentials, and Limitations | ACS Materials Au. https://pubs.acs.org/doi/10.1021/acsmaterialsau.3c00013 (accessed 2025-05-04).

- Zhou, W.-H.; Li, Y.-F. A Bi-Layered Asymmetric Membrane Loaded with Demineralized Dentin Matrix for Guided Bone Regeneration. J Mech Behav Biomed Mater 2024, 149, 106230. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

|

Disclaimer/Publisher’s Note: The statements, opinions and data contained in all publications are solely those of the individual author(s) and contributor(s) and not of MDPI and/or the editor(s). MDPI and/or the editor(s) disclaim responsibility for any injury to people or property resulting from any ideas, methods, instructions or products referred to in the content. |

© 2025 by the authors. Licensee MDPI, Basel, Switzerland. This article is an open access article distributed under the terms and conditions of the Creative Commons Attribution (CC BY) license (http://creativecommons.org/licenses/by/4.0/).