1. Introduction

Owing to clinical effectiveness, dental implant treatments have emerged as the preferred alternative to dental prostheses supported by natural teeth or adjacent oral soft tissues. However, the volume of hard and soft tissues is often insufficient due to changes in the ridge after tooth extraction [

1]. Bone loss can negatively affect the success of dental implantation. Therefore, new protocols are required to enhance the width and height of the alveolar crest. A commonly used method is guided bone regeneration (GBR), which involves the placement of mechanical barriers to exclude certain cell types (e.g., rapidly proliferating epithelium and connective tissue), thereby promoting the growth of slow-growing cells capable of forming the bone [

2]. GBR membranes serve as mechanical barriers and play a crucial role in the clinical success of GBR. These membranes should ideally support new bone formation and maturation for at least 6 months. Favorable GBR membranes possess high biocompatibility, occlusive properties, space-making capacity, and tissue integration and are clinically manageable [

2]. However, although numerous commercially available resorbable or non-resorbable GBR membranes are available [

3], none possess all these properties, and each has inherent advantages and disadvantages.

The first material used as a mechanical barrier for GBR was a non-resorbable membrane made of polytetrafluoroethylene (PTFE), which effectively prevented the migration of epithelial cells to the regenerated site [

4]. Titanium-reinforced PTFE, high-density PTFE, and titanium meshes have also been used, particularly for large defects. However, these non-resorbable membranes have associated disadvantages, including the need for a second surgical intervention to remove the membrane and the risk of infection due to membrane exposure [

5]. Resorbable membranes offer the advantage of being naturally resorbed by the body, eliminating the need for second-stage removal surgery. Resorbable membranes are preferred by clinicians and patients because of their reduced risk of morbidity, tissue damage, radiolucency and imaging. However, the resorption speed of these membranes varies among products and is unpredictable clinically, significantly affecting bone formation [

6].

The most commonly used natural polymers for barrier membranes in GBR procedures are type I and type III collagen derived from the porcine dermis and bovine tendons [

7]. Non-crosslinked collagen barrier membranes can begin to degrade as early as 4-28 days after placement [

8]. Although crosslinked membranes have longer degradation times, higher exposure rates have been reported for these membranes [

9]. Furthermore, most collagen membranes are weak under wet conditions and lose their space-maintaining ability under humid conditions. In addition, there is a potential risk of unknown pathogens being associated with animal-derived collagen [

10]. Synthetic biodegradable barrier membranes are considered suitable for use in GBR. However, although numerous membranes have been developed, an ideal barrier membrane has yet to be identified. The bioactivity and resorption time of the synthetic biodegradable membranes can be controlled by modifying their crystallinity, molecular weight, and hydrophobicity. These materials include biodegradable aliphatic polyesters such as polylactic acid, polyglycolic acid, polycaprolactone, and their copolymers polylactic-co-glycolic acid and polylactic-co-caprolactone acid [

11]. As it can be challenging to improve mechanical properties using only biodegradable polyesters, a combination of layers with different porosities has been proposed.

Recently, a new resorbable bilayer membrane for GBR composed of poly(l-lactic acid) and poly(-caprolactone) (PLACL membrane) was developed [

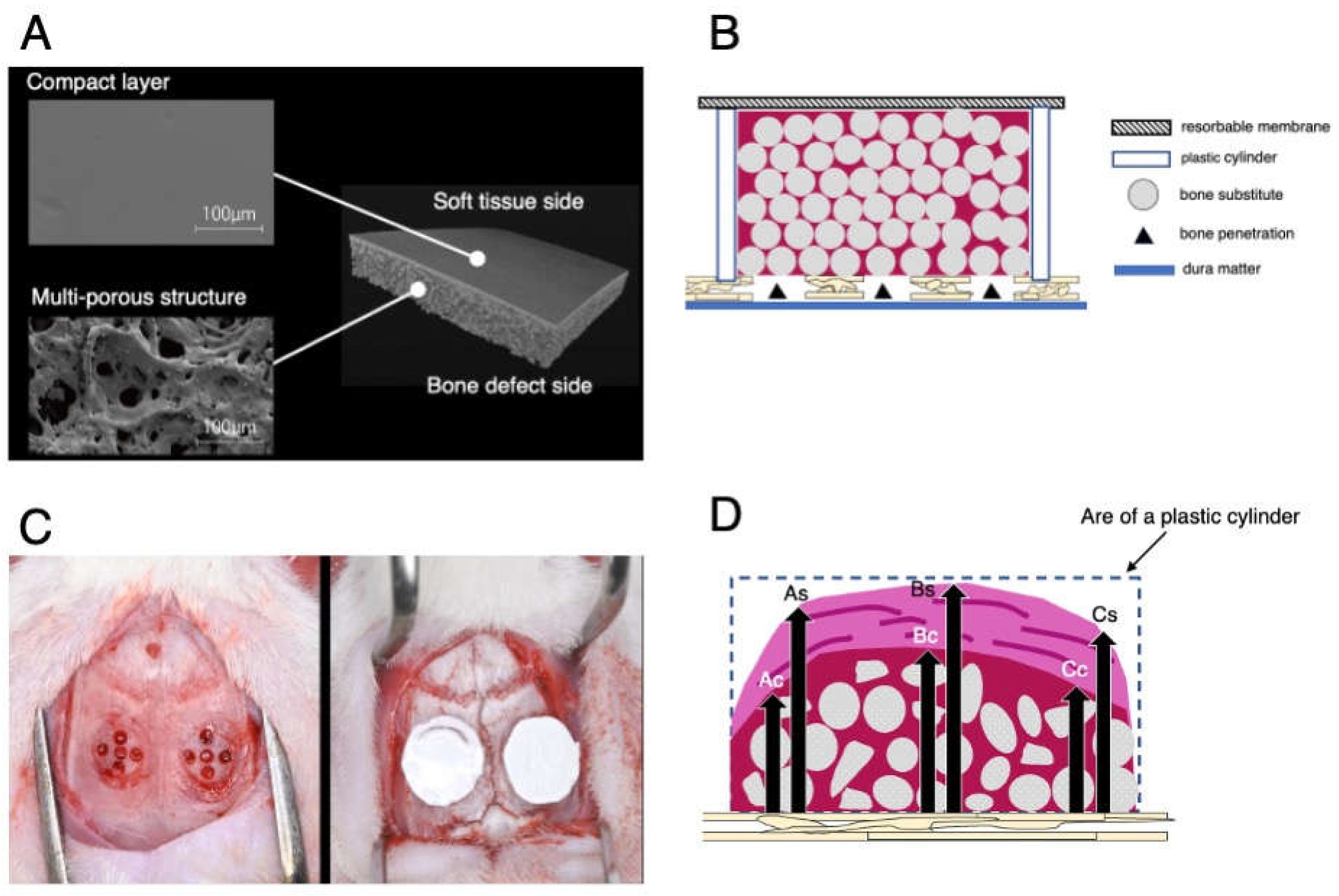

12]. By copolymerizing poly(L-lactic acid) with poly(-caprolactone), the rate of polymer degradation can be reduced, resulting in a more durable and biocompatible bilayer membrane for GBR. This biomaterial consisted of a compact layer and a multiporous layer (

Figure 1A). The compact layer on the soft tissue side prevents fibroblasts from entering the bone defect site, whereas the multiporous layer on the bone defect side promotes the differentiation of undifferentiated cells into osteoblasts and allows for flexible operability owing to its multiporous structure. In vitro analysis demonstrated that the PLACL bilayer membrane possessed excellent stretching ability and fitting properties. Furthermore, only 55% of the PLACL membranes were resorbed after 26 weeks in an in vitro setting [

13]. Therefore, the PLACL membrane acted as a barrier for a longer duration than other resorbable membrane products. The PLACL membrane is commercially available in the Japanese dental market.

However, although the PLACL membrane functions as a cell barrier during bone generation using GBR, preclinical data with histological assessments are lacking. Thus, this study aimed to compare the effects of a PLACL membrane with those of a natural collagen membrane on bone regeneration in a rat calvarial vertical GBR model. Therefore, we developed a rat calvarial vertical GBR model using plastic caps and examined the effectiveness of bioactive molecules, scaffolds, and membranes in GBR. The dynamics of osteogenesis were elucidated through micro-computed tomography (micro-CT) and histological examination.

2. Materials and Methods

2.1. Surgical Procedure and Experimental Groups

Animal experiments were approved by the Animal Experimentation Committee of Nihon University School of Dentistry (AP21D009). All applicable international, national, and/or institutional guidelines for the care and use of animals were followed.

From an animal welfare perspective, minimizing the use of animals was prioritized to a significant extent. Forty surgical sites were included in the study, involving 9-week-old male Fisher rats weighing 250–300 g. The sample size for the study was determined using a rigorous power analysis conducted using G*Power software v. 3.1 (University of Dusseldorf, Dusseldorf, Germany). The analysis utilized an alpha level of 0.05 and a statistical power of 95%. Data from a previous study using the same animal model [

13] were employed the appropriate sample size. This previous study compared the percentages of newly formed tissues using two different barriers and demonstrated a statistically significant difference. The results indicated percentages of 40±4.5% and 31.5±4.7% for the respective barriers.

The animals were acclimatized for 1 week and housed in pairs in standard cages in a controlled environment with regard to temperature, humidity, light/dark cycle, and diet. Surgery was performed under general anesthesia, initially using 4% isoflurane inhalation for 2 min, followed by an intraperitoneal injection of a mixture of dexmedetomidine hydrochloride (0.15 mg/kg), midazolam (2.0 mg/kg), and butorphanol tartrate (2.5 mg/kg). Local anesthesia was achieved with a 0.5 ml solution of 1:80,000 dilution of lidocaine to control bleeding and pain. All the surgical procedures were performed by an experienced surgeon (NW). The surgical procedure involved shaving and disinfecting the area between the eyes and posterior end of the skull with 70% ethanol. A 6.0-cm midline incision was made, and a mucoperiosteal flap was elevated to expose the cranial vertex. Bilateral circular grooves, 5 mm in diameter, were created at the center of each parietal bone using a trephine bur. Within the experimental site, five small holes (diameter: 0.5 mm) were drilled inside the circles without penetrating the inner dura of the cranial bone to induce bleeding from the marrow space, allowing the infusion of the graft material with blood.

Plastic cylinders measuring 5.0 mm in diameter and 3.0 mm in height were tightly fixed into circular grooves on the denuded bone. Surgical sites were randomly categorized to four groups based on the bone graft and mechanical barriers used as follows: (1) carbonate apatite (CO3AP, Cytrans®, GC, Tokyo, Japan) and a PLACL membrane (PLACL, Cytrans Elashield®, GC, Tokyo, Japan) (CO3AP+ PLACL); (2) carbonate apatite (CO3AP, Cytrans®, GC, Tokyo, Japan) + collagen membrane (COL, Bio-Gide, Geistlich-Pharma, Wolhusen, Switzerland) (CO3AP+COL); (3) deproteinized bovine bone mineral (DBBM, Bio-Oss®, Geistlich-Pharma, Wolhusen, Switzerland) and a PLACL membrane (PLACL, Cytrans Elashield®, GC, Tokyo, Japan) (DBBM+PLACL); and (4) deproteinized bovine bone mineral (DBBM, Bio-Oss®, Geistlich-Pharma, Wolhusen, Switzerland) + collagen membrane (COL, Bio-Gide, Geistlich-Pharma, Wolhusen, Switzerland) (DBBM+COL).

Each plastic cylinder was filled with the assigned bone graft and aligned with circular grooves. The cylinders were then covered with designated mechanical barriers (

Figure 1B). Two surgical sites were established in the calvaria of each animal (

Figure 1C). Finally, the mucoperiosteal flaps were repositioned using resorbable interrupted sutures (VSORB 4-0). The day of surgery was designated as day 0.

2.2. Outcome Assessments

2.2.1. Micro-CT Analysis

Mineral volume at the surgical sites was assessed using an in vivo micro-CT system (R_mCT2 system; Rigaku, Tokyo, Japan) without euthanizing the rats. The rats were anesthetized with an oxygen-isoflurane mixture administered via a facemask and positioned on an imaging stage. The exposure parameter was set to 90 kV. The region of interest for micro-CT assessment was the circular grooves (diameter: 5.0 mm, height: 3.0 mm) on the calvaria. Images were reconstructed using the i-View software (i-View Image Center, Tokyo, Japan) on a personal computer. The bone volume within the plastic caps in the voxel images was analyzed using the same software. The enhanced volume was calculated by subtracting the volume on day 0 from that at each follow-up. Micro-CT assessments were performed by a single, blinded examiner (TW) under the supervision of an experienced examiner (YA).

2.2.2. Histomorphometric Analysis

At 24 weeks postoperatively, all rats were euthanized by administering excess CO2 gas after the last micro-CT scan. The skin was dissected, and the calvarial bone defects with a fixed plastic cap were resected. Bone segments containing the cylinders were surgically removed and fixed in 10% neutral-buffered formalin. After fixation, the samples were dehydrated and embedded in paraffin wax blocks. To obtain thin sections for analysis, paraffin-embedded blocks were processed, and 5-μm sections were cut from the central region of each cylinder. The samples were stained with hematoxylin and eosin. Histomorphometric analyses were performed on histological sections obtained within the area of the plastic cylinders under a light microscope and an image analyzer computer system using FIJI (ImageJ 1.50b or 1.52i; National Institutes of Health, Bethesda, MD, USA). Specifically, we assessed osteogenesis (bone formation) in the experimental GBR sites.

Quantitative measurements were performed on each HE-stained histological section. These measurements included the percentage of newly generated bone area; percentage of remaining bone substitute particles; and heights of the total tissue, calcified tissue, and non-calcified tissue (

Figure 1D). Each height measurement was taken as the average of three different locations: the horizontal center of the plastic cylinder and both parts located 1 millimeter away from the center. Measurements for histomorphometric assessment were performed by an experienced and blinded examiner (SW).

2.3. Statistical Analysis

The means and standard deviations (SD) of each variable were calculated and analyzed using GraphPad Prism 7 software (GraphPad Inc., La Jolla, CA, USA). To assess the statistical significance of the bone volumes obtained from the micro-CT images and the percentages of residual bone substitutes in HE staining, a Kruskal-Wallis test with a Steel-Dwass post-hoc test was performed. The height measurements after HE staining were analyzed for statistical significance using the Mann-Whitney test. Statistical significance was set at p < 0.05.

3. Results

3.1. Visual Observation Postoperatively

After the surgical procedures, all rats displayed excellent tolerance and made a swift and uneventful recovery. Notably, there were no signs of wound dehiscence, graft migration, infection, or other complications.

3.2. Micro-CT Analysis

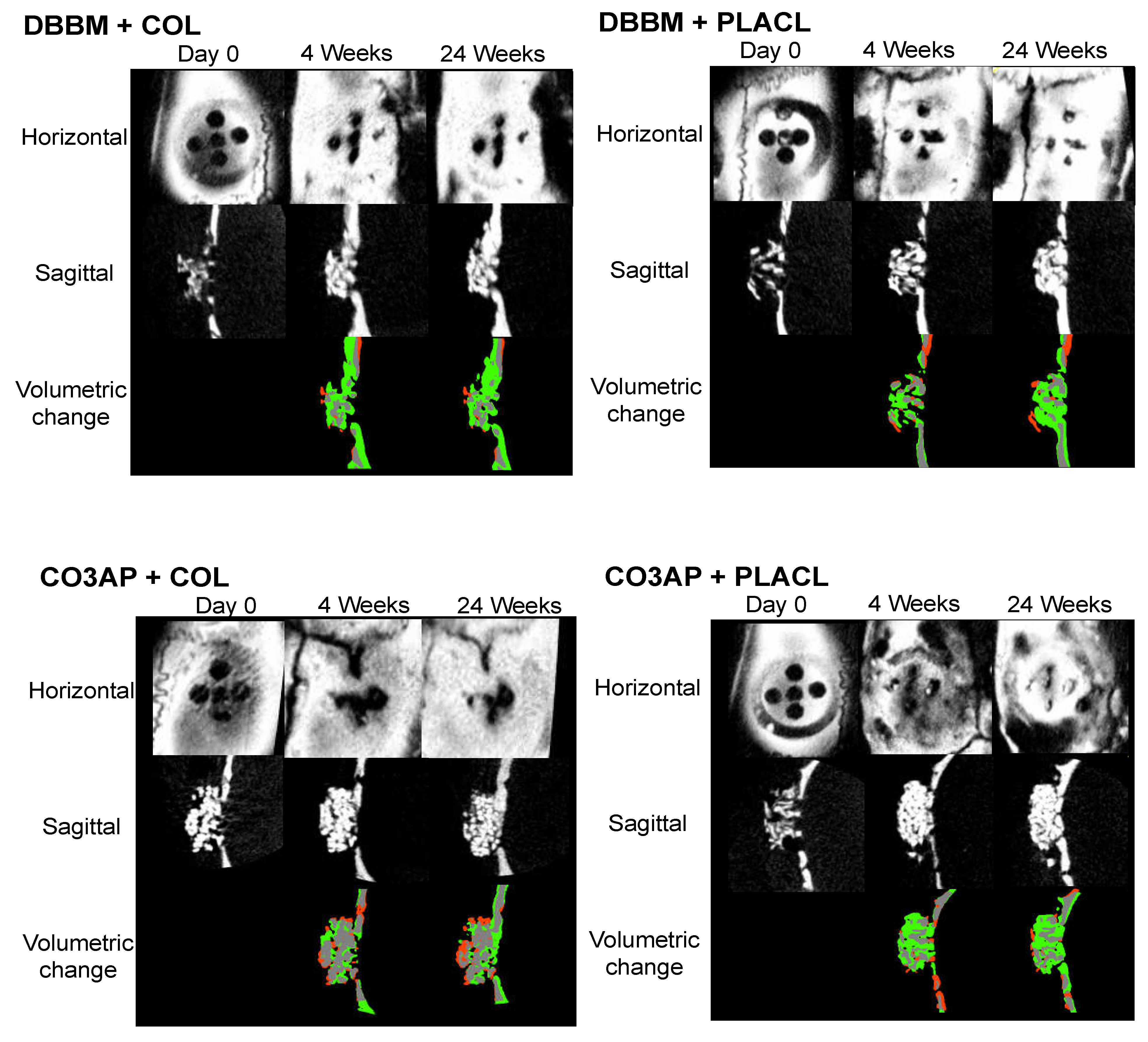

Figure 2 shows the micro-CT images of representative surgical sites from each group, offering enhanced visualization. The three-dimensional micro-CT images showed a gradual improvement in the radiopaque contrast within the cylinders in all four groups. Specifically, in the sagittal images captured at the 24-week milestone, the gap between the particles was partially filled with radiopacity in all four groups. Notably, throughout the observation period, the distinct characteristics of each DBBM particle were clearly distinguishable. This was in contrast to the aggregated appearance of CO3AP, which appeared as a conglomeration of multiple particles. However, these differences in particle appearance did not have any impact on the voxel-based volumetric bone analysis. Quantitative volumetric analysis revealed a progressive increase in the bone volume within the cylinders in all four groups. The total voxel count increased in a time-dependent manner until 8 weeks and reached a state of equilibrium thereafter. Nevertheless, statistical analysis indicated that the observed differences among the four groups were not statistically significant (

Table 1).

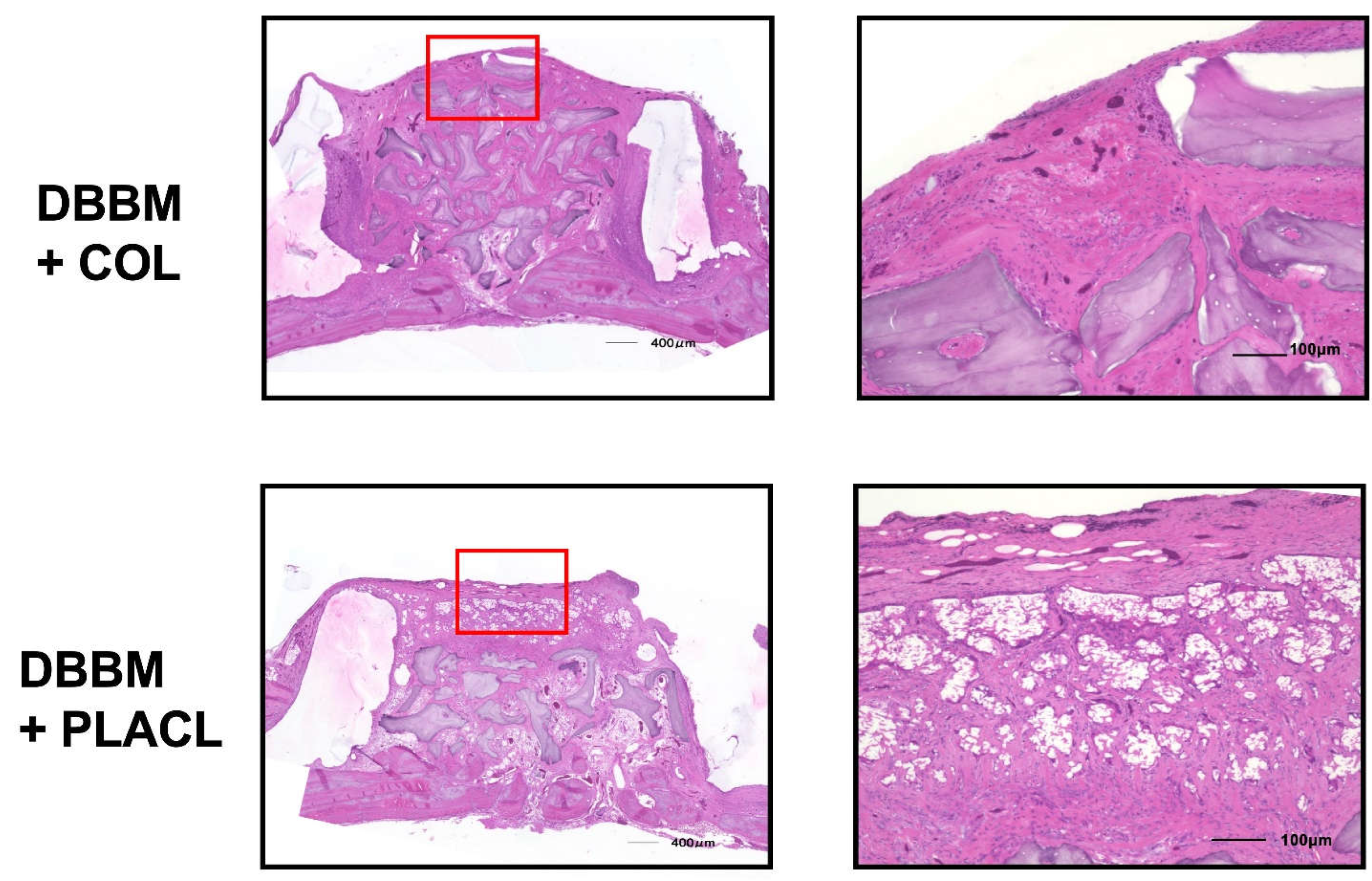

3.3. Histomorphometric Analysis

Figure 3 shows the histology of the rats treated with DBBM. At 24 weeks postoperatively, both the groups treated with COL and PLACL exhibited significant bone augmentation, as observed in the images. The bone-substituted particles were surrounded by newly formed bone tissue, without any signs of inflammation or heterogenization. The percentage of residual bone substitutes was similar for both types of bone substitutes: 31.4% for COL and 26.4% for PLACL. Interestingly, the height of the total tissue volume was significantly greater in the DBBM+COL group than in the DBBM+PLACL group (2.43 mm vs. 1.95 mm). This difference was primarily due to the height of the soft tissue, which measured 0.63 mm in the DBBM+PLACL group and 0.23 mm in the DBBM+COL group. However, there were no significant differences in the height of the calcified tissue between the two groups (1.76 mm in the DBBM+COL group vs 1.72 mm in the DBBM+PLACL group). In the DBBM + COL group, augmented calcified tissue was covered with a thin fibrous tissue layer. In contrast, in the DBBM + PLACL group, the augmented calcified tissue was covered with thick soft tissue that exhibited air bubbles and ruptured fibrous tissue.

Figure 4 shows the histology of samples treated with CO3AP at 24 weeks postoperatively. The CO3AP-treated rats exhibited a similar trend to the DBBM-treated rats. The analysis revealed no significant difference in the percentage of residual bone substitutes between the CO3AP+COL and the CO3AP+PLACL groups (29.1% vs 33.3%). While the total height (2.50 mm vs 1.99 mm) and soft tissue height (0.62 mm vs 0.17 mm) were greater in the CO3AP+PLACL group than in the CO3AP+COL group, the height of calcified tissue was comparable in both groups (1.83 mm vs 1.82 mm).

Table 2.

Height of calcified and non-calcified tissue in the DBBM groups (mm).

Table 2.

Height of calcified and non-calcified tissue in the DBBM groups (mm).

| Height (mm) |

Total tissue |

Calcified tissue |

|

Non-calcified tissue |

|

| PLACL |

2.43* |

|

(0.29) |

|

1.76 |

|

(0.14) |

|

0.63** |

|

(0.29) |

|

| COL |

1.95* |

|

(0.24) |

|

1.72 |

|

(0.20) |

|

0.23** |

|

(0.13) |

|

Table 3.

Height of calcified and non-calcified tissue in the CO3AP groups (mm).

Table 3.

Height of calcified and non-calcified tissue in the CO3AP groups (mm).

| Height (mm) |

Total tissue |

Calcified tissue |

|

Non-calcified tissue |

|

| PLACL |

2.50* |

|

(0.22) |

|

1.83 |

|

(0.17) |

|

0.62** |

|

(0.30) |

|

| COL |

1.99* |

|

(0.25) |

|

1.82 |

|

(0.32) |

|

0.17** |

|

(0.10) |

|

4. Discussion

The present study conducted a comprehensive analysis to evaluate the effects of PLACL membranes on bone regeneration in a rat model of calvarial vertical GBR comparing with COL membranes. Micro-CT analysis revealed a gradual improvement in radiopaque contrast within the cylinders in all groups. The particles were distinguishable, and there was a progressive increase in bone volume within the cylinders over time. Histomorphometric analysis of 24 weeks also showed significant bone augmentation in both PLACL and COL groups. In 24 weeks, PLACL groups had a greater total tissue volume and height of non-calcified tissue compared to COL groups. These results were independent of the type of bone graft material used. Based on these results, we successfully demonstrated the potential of PLACL membranes to overcome challenges related to the infiltration of epithelial cells into the bone, which can impede proper bone formation.

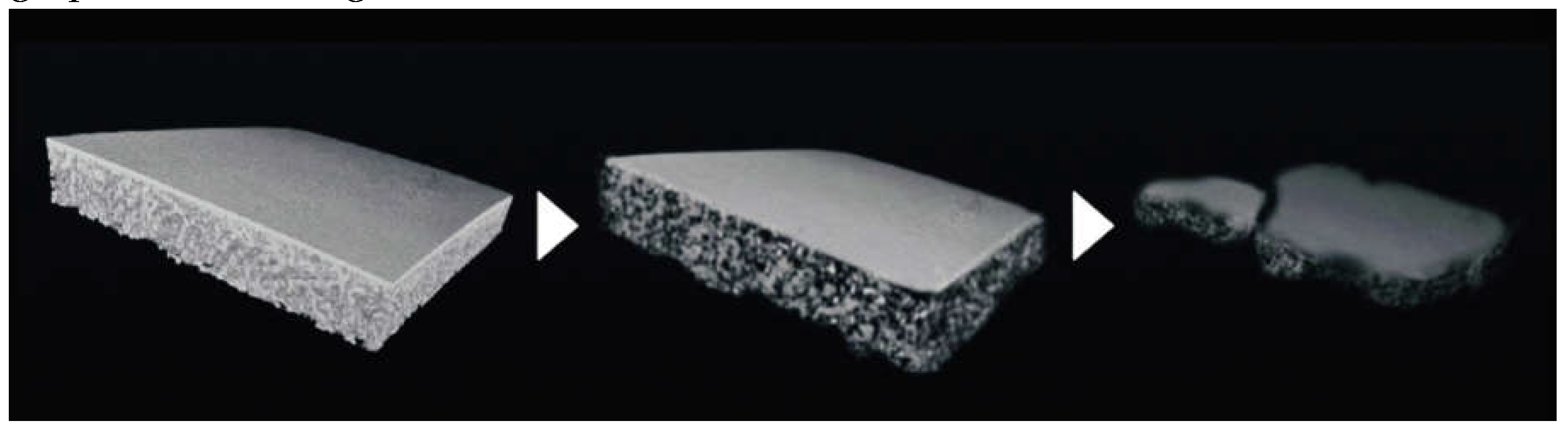

Previous studies indicated that the PLACL bilayer membrane exhibits a slow degradation rate

in vitro, suggesting that it can provide sufficient space for bone regeneration. Based on these findings, we evaluated the dynamic structural changes in bone regeneration in our rat model using micro-CT scans. This imaging technique allowed us to visualize and quantify important parameters such as bone volume and morphology. Our results revealed a gradual increase in bone volume over an 8-week period in the two groups utilizing PLACL and collagen membranes, indicating successful bone regeneration. Hence, based on our findings, we can conclude that the critical period for the blocking effect of the GBR membrane is approximately 8 weeks. This crucial timeframe signifies the optimal duration during which the membrane effectively prevents unwanted tissue ingrowth and facilitates proper tissue regeneration. Our histological analysis showed partially degraded PLACL membranes after a 24-week follow-up period. The 24-week follow-up period represents a remarkable achievement in the field of tissue regeneration research, particularly when considering its extended duration for observations conducted on rats. This extended timeframe allows for a comprehensive evaluation of the long-term effects of the treatment, providing valuable insights into the sustained efficacy and stability of the regenerative process. Our histological findings correspond with those of previous

in vitro report regarding material degradation and support a prolonged barrier effect during GBR protocols [

13].

Figure 5 illustrates the time-dependent degradation of the PLACL material using schematic images. Notably, even at 24 weeks post transplantation, the PLACL membrane showed significant resilience, with only occasional areas of partial degradation and the presence of intermittent air bubbles. This extended preservation of the barrier effect holds great promise in facilitating optimal bone regeneration.

The current study did not specifically confirm the presence of inflammation above and beneath the PLACL membranes. This characteristic is primarily attributed to the exceptional biocompatibility of this PLACL membrane. In a previous study by Abe et al.[

14], bacteria were directly seeded-collected onto the compact layer of the PLACL membrane. They observed significantly fewer adherent bacteria on the PLACL bilayer membrane than on the control membranes throughout the experimental period. Moreover, the PLACL membrane effectively blocked bacterial penetration, as no bacterial cells were detected within its structure. The unique structure of the PLACL membrane contributed to its barrier function against both bacteria and epithelial cells. Additionally, the porous layer of the membrane provides support for the proliferation and differentiation of osteogenic cells.

In this study, two different types of particulate bone substitutes were used in cylinders covered with two distinct barrier membranes: DBBM and CO3AP. DBBM is a widely used bone graft material, especially in regions where the use of human-donated grafts is prohibited. Although xenografts are the initial standard replacement materials similar to autografts and allografts, they are generally do not resorbed over time. Recently, a CO3AP bone substitute has been developed as an alternative to allografts and xenografts. Commercially available CO3AP particles are chemically pure and are produced through a dissolution-precipitation reaction in a water-based solution using a calcite block instead of through a sintering process. This innovative manufacturing method ensures that the CO3AP particles retain their biodegradability. This result aligns closely with our previous report, which also utilized the same model and had a follow-up period of 12 weeks [

13]. However, it is important to note that our histological analysis conducted over 24 weeks revealed no resorption of DBBM or CO3AP particles.

These findings have significant implications in clinical practice, particularly in addressing issues associated with the use of animal- or human-derived materials. The combination of the synthesized absorbable materials, PLACL membranes, and CO3AP bone substitutes is a promising solution. The potential practical application of the presented options provides positive prospects for a wider range of patients needing medical interventions.

One significant limitation of this study is the utilization of an animal model, specifically the rat calvaria, which may not accurately reflect the behavior and response of human jawbones. Although the current study demonstrated partial resorption of the membrane over 24 weeks, it remains uncertain whether similar results would be observed in humans. Additionally, observations made during the 24-week period revealed limited resorption on the PLACL membranes and no resorption on CO3AP. Consequently, conducting further long-term observations is crucial for gaining a more comprehensive understanding of the long-term behavior and potential resorption patterns of these materials. By extending the observation period, researchers could collect more robust data and insights, ultimately providing a more accurate assessment of the clinical viability and effectiveness of PLACL membranes and CO3AP bone substitutes.

5. Conclusions

PLACL membranes preserved the barrier effect over an extended period in a rat calvarial vertical GBR model. These findings highlight the potential of PLACL as a durable barrier that supports bone regeneration.

Author Contributions

Conceptualization, AH. and S.S.; investigation, T.W., S.W. and K.K.; methodology, S.M., Y.A. and S.S.; resources, N.W. and R.S.; super- vision, S.M. and Y.A.; project; funding acquisition, A.H. and S.S.; writing-original draft: A.H.; writing-review and editing, M.S, Y.A. and S.S. All authors have read and agreed to the published version of the manuscript.

Funding

This work was financially supported in part by the Sato Fund and Grant-in-Aid from the Dental Research Center, Nihon University School of Dentistry, Tokyo, Japan. This work was also supported by the JSPS KAKENHI Grant-in-Aid for Scientific Research (C) Number 22K10042 for A.H. and 21K09940 for S.S. Funds were used for illustration outsourcing, language editing, and submission.

Institutional Review Board Statement

Approvement by the Animal Experimentation Committee of Nihon University School of Dentistry (AP21D009).

Informed Consent Statement

Not applicable

Data Availability Statement

Not applicable

Acknowledgments

Schematic images and microscopic images of PLACL membrane were provided by GC, Tokyo, Japan.

Conflicts of Interest

The authors declare no conflict of interest.

References

- Thoma, D.S.; Gil, A.; Hämmerle, C.H.F.; Jung, R.E. Management and Prevention of Soft Tissue Complications in Implant Dentistry. Periodontol 2000 2022, 88, 116–129. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Omar, O.; Elgali, I.; Dahlin, C.; Thomsen, P. Barrier Membranes: More than the Barrier Effect? J. Clin. Periodontol. 2019, 46 (Suppl. 21), 103–123. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Alauddin, M.S.; Abdul Hayei, N.A.; Sabarudin, M.A.; Mat Baharin, N.H. Barrier Membrane in Regenerative Therapy: A Narrative Review. Membranes 2022, 12, 444. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Becker, W. , Becker, BE., McGuire, MK.; Localized ridge augmentation using absorbable pins and e-PTFE barrier membranes: A new surgical technique. Case reports. Int J Periodontics Restorative Dent 1994, 14, 48–61. [Google Scholar] [PubMed]

- Zhang, M.; Zhou, Z.; Yun, J.; Liu, R.; Li, J.; Chen, Y.; Cai, H.; Jiang, H.B.; Lee, E.S.; Han, J.; et al. Effect of Different Membranes on Vertical Bone Regeneration: A Systematic Review and Network Meta-Analysis. Biomed. Res. Int. 2022, 7742687. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Solomon, S.-M.; Sufaru, I.-G.; Teslaru, S.; Ghiciuc, C.M.; Stafie, C.S. Finding the Perfect Membrane: Current Knowledge on Barrier Membranes in Regenerative Procedures: A Descriptive Review. Appl. Sci. 2022, 12, 1042. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Elgali, I.; Omar, O.; Dahlin, C.; Thomsen, P. Guided Bone Regeneration: Materials and Biological Mechanisms Revisited. Eur. J. Oral Sci. 2017, 125, 315–337. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Tal, H.; Kozlovsky, A.; Artzi, Z.; Nemcovsky, C.E.; Moses, O. Long-Term Bio-Degradation of Cross-Linked and Non-Cross-Linked Collagen Barriers in Human Guided Bone Regeneration. Clin. Oral Implants Res. 2008, 19, 295–302. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Jiménez Garcia, J.; Berghezan, S.; Caramês, J.M.M.; Dard, M.M.; Marques, D.N.S. Effect of Cross-Linked vs Non-Cross-Linked Collagen Membranes on Bone: A Systematic Review. J. Periodontal Res. 2017, 52, 955–964. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Wang, H. A Review of the Effects of Collagen Treatment in Clinical Studies. Polymers 2021, 13, 3868. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Pappalardo, D.; Mathisen, T.; Finne-Wistrand, A. Biocompatibility of Resorbable Polymers: A Historical Perspective and Framework for the Future. Biomacromolecules 2019, 20, 1465–1477. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Yoshimoto, I.; Sasaki, J.I.; Tsuboi, R.; Yamaguchi, S.; Kitagawa, H.; Imazato, S. Development of Layered PLGA Membranes for Periodontal Tissue Regeneration. Bioengineering 2018, 5, 64. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Abe, G.L.; Sasaki, J.I.; Katata, C.; Kohno, T.; Tsuboi, R.; Kitagawa, H.; Imazato, S. Fabrication of Novel Poly(lactic acid/caprolactone) Bilayer Membrane for GBR Application. Dent. Mater. 2020, 36, 626–634. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Senoo, M.; Hasuike, A.; Yamamoto, T.; Ozawa, Y.; Watanabe, N.; Furuhata, M.; Sato, S. Comparison of macro-and micro-porosity of a titanium mesh for guided bone regeneration: An in vivo experimental study. In Vivo 2022, 36, 76–85. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Abe, G.; Tsuboi, R.; Kitagawa, H.; Sasaki, J.I.; Li, A.; Kohno, T.; Imazato, S. Poly(lactic acid/caprolactone) Bilayer Membrane Blocks Bacterial Penetration. Bioengineering 2022, 9, 41. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

|

Disclaimer/Publisher’s Note: The statements, opinions and data contained in all publications are solely those of the individual author(s) and contributor(s) and not of MDPI and/or the editor(s). MDPI and/or the editor(s) disclaim responsibility for any injury to people or property resulting from any ideas, methods, instructions or products referred to in the content. |

© 2023 by the authors. Licensee MDPI, Basel, Switzerland. This article is an open access article distributed under the terms and conditions of the Creative Commons Attribution (CC BY) license (http://creativecommons.org/licenses/by/4.0/).