1. Introduction

The building industry accounts for approximately 40% of global greenhouse gas emissions — a figure that likely rises further when the entire building lifecycle is considered [

1,

2]. Beyond operational demands, building materials carry significant embodied energy, beginning at extraction and often magnified by long-distance transport [

3]. Together, these factors increase both total energy consumption and associated costs.

Over the past three decades, there has been strong emphasis on embedding sustainable principles into building design to reduce carbon footprint in the building sector [

4,

5]. Several green certification schemes have emerged to guide this shift; notably LEED, which originated in the United States and has achieved global adoption since its introduction in the late twentieth century [

6]. Other notable schemes include BREEAM, CASBEE, Green Star, Green Mark, Passivhaus, Three Star, Minergie, and Display Energy Certification, originating respectively from the United Kingdom, Japan, Australia, Singapore, Germany, China, Switzerland, and the European Union [

7].

These schemes typically prioritize core sustainability criteria, including sustainable siting (eco-friendly land development and management), energy conservation (reducing consumption and adopting renewables), water efficiency (minimizing potable water use), and indoor environmental quality (IEQ) [

8]. Policymakers have estimated that adhering to these green standards can yield operating cost savings ranging from at least 10% to as high as 97%, depending on certification level and the extent of sustainable design implementation [

9].

Importantly, these certification schemes apply not only to new buildings but also to existing structures considering retrofitting. However, a major deterrent remains: the high documentation and implementation costs required for certification. For example, Uğur and Leblebici [

10] found that LEED Gold and Platinum buildings incurred additional construction costs of 7.43% and 9.43%, respectively.

While certification remains largely voluntary, municipalities are now integrating green building principles into their building codes without mandating full certification [

11]. Beyond upfront costs, another key critique of certification schemes is the difficulty of assessing operational performance holistically. Questions persist about whether certified buildings consistently deliver on their promised benefits [

12,

13,

14].

Programs like ENERGY STAR in the U.S. provide operational benchmarking for commercial buildings, with a score ≥75% indicating top energy performance, but they focus solely on energy [

15]. The Home Energy Rating System (HERS), also prominent in the U.S., targets residential buildings and narrowly focuses on energy performance; its score can influence resale value, as energy-efficient homes often command a premium [

16].

Among the core sustainability categories, three stand out for operational assessment: indoor environmental quality, energy efficiency, and water efficiency. Yet research shows that certification alone does not guarantee superior operational performance, particularly when certified buildings are compared to uncertified counterparts. For example, Clay et al. [

17] found that LEED-certified federal retrofits did not achieve statistically significant average energy savings, although buildings with higher energy scores showed meaningful improvements. Similarly, a Korean study reported that certified non-residential buildings had energy use intensities (EUIs) nearly 50% lower than general buildings [

18]. In a Canadian longitudinal study, Issa et al. [

19] discovered that LEED-certified schools had 28% lower total energy costs than non-certified schools, though the savings often failed to offset higher construction costs.

Other studies show contradictory results. In a study of 100 certified commercial and institutional buildings, Newsham et al. [

20] found that while LEED buildings used 18–39% less energy, 28–35% consumed more energy than similar uncertified buildings. More recently, Vosoughkhosravi et al. [

21] reported that a LEED Silver-certified residential college building consumed more electricity, gas, and water over five years than seven non-LEED-certified ones. In a review of 44 papers, Amiri et al. [

12] found that 23% of the studies concluded LEED certification improved energy efficiency, while 18% reached the opposite conclusion. They also observed that lower operational performance was frequently associated with lower-level certifications.

These and other studies demonstrate that comparative research on energy performance often yields mixed results. Similar mixed patterns have emerged regarding indoor environmental quality (IEQ), where green certification does not consistently translate to superior performance [

21].

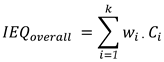

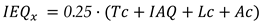

IEQ is typically assessed in three ways: (a) subjectively, through occupant satisfaction surveys covering the four critical components (4CCs) — thermal comfort (Tc), indoor air quality (IAQ), acoustic comfort (Ac), and lighting comfort (Lc), sometimes including aesthetics and cleanliness; (b) objectively, through sensor-based physical measurements; or (c) via dual-method approaches. A major innovation in the dual-method approach is the development of protocol-based weighting schemes (or models) to yield composite IEQ scores, as summarized in

Equation (1) [

22,

23]:

where

represents the weight assigned to component

, and

is the score or value of component

, and

k is the total number of IEQ components considered in the model.

Weighting is often achieved using either straightforward or complex approaches [

24,

25]. Several studies employ regression analysis on Likert-scale satisfaction responses to component-specific survey questions relative to overall satisfaction, or use the Analytical Hierarchy Process (AHP) to assess their relative importance through pairwise comparisons [

26,

27].

While the IEQ models aim to quantify overall IEQ, scholars like Piasecki et al. [

28] have argued that many become unnecessarily complex, introducing subjectivity due to variability in occupant perceptions. They advocate for crude weighting schemes that assign equal weights to each IEQ component, yielding simpler and often more practical results. Supporting studies [

23,

27] suggest that minor adjustments to category weights rarely change overall IEQ outcomes, making equal weighting a robust approach. Additionally, regression-derived weightings can be problematic, as they assume linear relationships and may exclude variables with minimal or negative coefficients [

29,

30], potentially dismissing meaningful contributors.

We propose that multiple linear regression (MLR) analysis be used primarily to understand statistically significant relationships between the 4CCs and overall satisfaction, while equal-weighted IEQ models should be employed independently to generate composite scores — particularly when working with sample sizes of at least 20 participants.

Energy performance assessments typically rely on utility bills or energy meters, calculating energy use intensity (EUI) benchmarked against design estimates or industry standards [

31,

32]. While useful, EUI benchmarks can emphasize competitive comparisons and overlook operational nuances or occupant needs. This is especially problematic in regions with extreme weather conditions, which elevate HVAC demands, operating costs, and thermal discomfort. Therefore, region-specific metrics are critical for estimating building energy performance. Furthermore, since dissatisfaction with rising energy costs can affect occupant well-being [

33,

34,

35], incorporating metrics that capture user perceptions may offer valuable insights into how satisfaction or dissatisfaction evolves over time.

Although some studies have employed quantitative models, IoT-enabled tracking, or simulations to examine IEQ–energy relationships [

36,

37], most have failed to provide a unified framework that integrates IEQ, energy, and water into a holistic operational performance metric. The preceding examples suggest that researchers often independently assess operational variables to evaluate building performance. While relatively few studies have measured at least two of the most critical operational variables concurrently, those that aim for holistic integration often do so based on differing rationales and sometimes flawed methodologies.

For example, Wang and Zheng [

31] and Roumi et al. [

38] independently explored the relationship between daily energy consumption and IEQ parameters using similar statistical models, but their findings diverged. The former identified relative humidity as the most energy-sensitive parameter, whereas the latter found that sufficient artificial lighting was the most energy-intensive.

Geng et al. [

39] proposed the Environmental Energy Efficiency (EEE) model to evaluate the trade-off between IEQ and energy consumption. This model was later adopted or modified in recent studies and applied to various building types [

40,

41]. However, the adopted energy performance metric underlying the overall EEE calculation exhibits a critical methodological flaw that limits its applicability for buildings that deviate significantly from the adopted EUI benchmark — an oversight that can compromise the validity of its conclusions. Additionally, the performance grading system of the final EEE model lacks clear intervention pathways, further reducing its practical value for informing energy policy and decision-making.

While these studies have advanced understanding of the trade-offs between energy and IEQ, they fall short of helping the building industry establish a holistic operational performance metric that can consistently rate buildings relative to others of similar type and function and that can be adopted without methodological pitfalls. A recent literature review by Perera et al. [

42] proposed integrating IEQ and energy efficiency as a promising future research direction to support improved building design and construction. However, their proposal lacks sufficient clarity regarding the development pathway, application framework, and procedural guidance.

To advance sustainable cities and societies, there is an urgent need to shift from sustainable building design to sustainable building operations. A promising way to achieve this is by developing a uniform metric that enables consistent evaluation of operational performance across buildings of similar types and functions, adaptable to diverse climates and regions. This study seeks to bridge key gaps in the literature—particularly the divide between policy and practice—by providing a proof of concept for a holistic operational performance evaluation framework, applied across three case studies encompassing six buildings located in a humid subtropical region (Cfa zone according to the Köppen climate classification) in the United States.

2. Methodology

The case study buildings are located in Baton Rouge, the capital city of Louisiana, which is situated in the southeastern United States and experiences distinct seasonal changes, with a cooling season typically spanning from April to September or October, and a heating season usually extending from mid-November to mid-March [

43]. Although October is often considered a transition month, shifts in local climate patterns can bring about a faster or slower transition. Over the past three years, Baton Rouge has experienced heating degree days ranging from 1,067 to 1,669, and cooling degree days ranging from 2,708 to 3,496, with January consistently recording the highest heating degree days and August the highest cooling degree days.

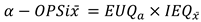

The methodology for this research involves two main phases. The first phase includes field measurements of environmental variables, the distribution of survey questionnaires, and the collection of energy usage data. The second phase focuses on the development and implementation of multiple dimensions of the Operational Sustainability Index (OPSi). The overall methodological approach is summarized in

Figure 1. Collected data were analyzed using Excel and Python environments following meticulous quality checks, and multiple linear regression was performed to examine the relationships between IEQ factors and overall user experience satisfaction.

2.1. Data Collection

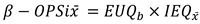

Case I consists of a Silver-level LEED-certified dormitory (LCD) and a non-certified dormitory (NCD), both four-story buildings, which began operation in 2015 and 2008, respectively. Among the several dorm rooms and corridors within the 110,000 ft² LCD and 70,000 ft² NCD, two representative dorm rooms and a corridor space were each selected for environmental measurements. Sensor equipment was used with the following specifications: temperature (measuring range [MR] 0–50 °C; accuracy [Ay] ±1 °C), humidity (MR 0–99.9%; Ay ±5%), CO₂ (MR 0–5,000 ppm; Ay ±5% ± 50 ppm), PM2.5 (MR 0–999 µg/m³; Ay ±10 µg/m³), formaldehyde (MR 0–2 mg/m³; Ay ±0.03 mg/m³), illuminance (MR 1–100,000 lx; Ay ±(4% + 2 lx)), and sound pressure level (MR 30–130 dB; Ay ±3.0 dB–±5.0 dB). Sensors were strategically placed at occupant breathing zones in dorm rooms and at convenient corridor locations, with data logged at 30-minute intervals over one month in the cooling season and one month in the heating season. Lighting and acoustic measurements were conducted on a single day, with equipment positioned at 0.75 m height in rooms and 1.55 m in corridors.

Case II includes a Certified-level, single-floor LEED-certified events building (LEB) and a non-certified events building (NEB), designed in 2014 and the 1980s, respectively. LEB is a 2,100 ft² auditorium, while NEB is a two-story, 60,000 ft² building comprising a conference room and a lobby as primary public spaces. Hygrothermal-IAQ equipment was placed at convenient locations, generally between 0.75 m and 1.55 m heights to represent seated and standing positions. Acoustic and lighting measurements were taken at heights of 0.75 m and 1.6 m, respectively. The same equipment used in Case I was deployed in Cases II and III. However, while Cases I and II followed the same monitoring durations, Case III (a 1,100 ft², four-bedroom multifamily housing unit occupied by four males [MHM], and a 1,300 ft², four-bedroom unit occupied by four females [MHF]) was monitored in a single day—approximately two weeks apart between the two units—due to privacy concerns. Sensors were placed in each bedroom and the living room. Layouts of typical rooms and sensor placements are shown in

Figure 2, while

Figure 3 provides interior views of the events spaces and equipment setups.

All buildings used mechanical systems for heating and cooling. The residential buildings had glazed windows with blinds, while the events buildings featured building envelopes with approximately 70% glazing. The dormitories were predominantly constructed with thick concrete envelopes, whereas the multifamily housing units primarily used wood-insulated envelopes.

Energy usage data for Cases I and II were obtained from facility managers, while multifamily housing users provided energy data for Case III. This study used one year of energy consumption data: April 2023–March 2024 for Case I, March 2023–February 2024 for Case II, and November 2023–October 2024 for Case III, with environmental monitoring occurring within these periods.

Survey questions were administered both online and in person, focusing on the 4CCs (thermal comfort, indoor air quality, acoustic comfort, and lighting comfort) for building users, and on energy use and costs for facility managers. A five-point Likert scale (1 = Very Dissatisfied to 5 = Very Satisfied) was used.

Table 1 presents a summary of survey questions and participant numbers. Notably, dormitory users were long-term residents, whereas events building users were occasional visitors, typically for short stays (e.g., a few hours on a single day). Due to the unintentional sharing of a single survey link with multifamily housing occupants, which made it difficult to separate male and female responses, subjective survey data were excluded from Case III analyses.

2.2. Development of the Operational Sustainability Index

The development of the Operational Sustainability Index (OPSi) metric begins with the establishment of Indoor Environmental Quality (IEQ) models and Energy Utility Quality (EUQ) models, which are later integrated to yield OPSi variants.

2.2.1. Indoor Environmental Quality Models

This study employs two main dimensions of IEQ:

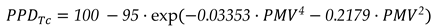

As presented in

Equations (2) and

(3), thermal comfort (Tc) is derived from the PPD-PMV model, which predicts the average thermal sensation of a large group on a scale from −3 (cold) to +3 (hot), with −0.5 to +0.5 considered optimal [

45]. While the Predicted Percentage Dissatisfied with the thermal environment (PPD

Tc) can be calculated using

Equation (2), this study used the thermal comfort software developed by the Center for the Built Environment (CBE), compliant with the latest version of ASHRAE Standard 55 [

46]. This software incorporates variables such as operative temperature, air velocity, clothing insulation, and metabolic rate.

For all cases, a fixed air velocity of 0.15 m/s was used.

For Case I (April–May), 0.5 clo was applied for dorm rooms and 0.54 clo for corridors during the cooling season, and 0.9 clo for the heating season (January–February), in line with field observations literature [

47], and the mean seasonal air temperature was adopted as the operative temperature. Metabolic rates of 1.0 met and 1.2 met were used for dorm rooms and corridors, respectively, reflecting activities such as eating, reading, sitting, and sleeping in dorm rooms, and fleeting standing and sitting in corridors [

48].

In Case II, an average metabolic rate of 1.1 met was assumed for both heating and cooling seasons, reflecting typical activities such as sitting and relaxed standing in events buildings, consistent with ASHRAE Standard 55 [

46]. Clothing insulation values of 0.57 clo and 0.9 clo were used for the cooling (March–April) and heating (November) seasons, respectively, based on existing recommendations [

49,

50].

For Case III, measured in the transition month of October, 0.75 clo was used, with metabolic rates of 1.0 met for bedrooms and 1.5 met for living rooms.

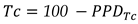

Applying the normalization steps in

Equations (4) to

(7), IAQ was assessed with a focus on three pollution indicators (

Iz, where z = CO₂, PM2.5, and formaldehyde [HCHO]), popular in several green building certification schemes. For these indicators, logarithmic performance scales were applied. For instance, an upper limit of 15,000 ppm was set for CO

2, and

denotes the logarithmic ratio of indoor CO

2 concentration (ppm) relative to the adopted outdoor reference concentration of 415 ppm.

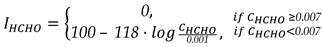

The U.S. EPA [

51] noncancer reference concentration for long-term exposure–0.007 mg/m

3 of HCHO–was adopted as the threshold for multifamily housing spaces and dorm rooms, as shown in

Equation (5a). For other spaces, the WHO [

52] short-term exposure guideline of 0.1 mg/m

3 was used to as the permissible limit, as indicated in

Equation (5b). Here,

represents the measured formaldehyde concentration in mg/m

3.

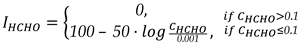

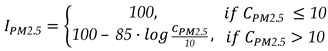

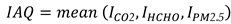

As indicated in

Equation (6), where

represents the concentration of particles < 2.5 µm measured in μg/m

3, values at or below 10 µg/m

3—as recommended by the WHO [

53]—were considered optimal for PM2.5, while values exceeding this threshold were adjusted using a logarithmic scale. For indicators measured across both seasons, seasonal averages were calculated and incorporated into the respective equations to ultimately derive the overall IAQ performance score, as shown in

Equation (7).

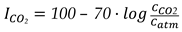

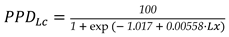

The Predicted Percentage Dissatisfied with lighting conditions (PPD

Lc) was calculated using

Equation (8), based on a regression model developed from reported case studies [

54,

55]. This model relates to illuminance (

Lx) levels, with an assumed upper limit of 1,400 lx. The resulting value was then subtracted from 100 to estimate the percentage of occupants satisfied with the lighting conditions in the building, according to

Equation (9).

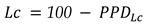

The Predicted Percentage Dissatisfied with acoustic conditions (PPD

Ac) was calculated by determining the numerical difference between the actual and design sound levels (SLs) for the examined spaces, doubling the resulting value, and then subtracting this from 100 to estimate the percentage of occupants satisfied with the acoustic environment.

Equations (10) and

(11) are based on reported methods [

44,

56,

57]. Following the ANSI S12.2 standard [

58], a design sound level of 40 dB was used for multifamily housing units and dorm rooms, while 45 dB was applied for other spaces across cases.

The objective indoor environmental quality, IEQx, was then calculated by averaging the performance scores of the 4CCs:

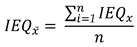

To further examine the effect of combination methods, IEQx was subdivided into two categories:

accounting for the

n spaces evaluated in each building, according to

Equations (13) and

(14), respectively:

2.2.2. Energy Utility Quality Models

In Louisiana and similar regions across the United States, historical data and climate model projections consistently show that substantially more energy—and therefore, more money—is consumed in both residential and commercial buildings during the cooling season to meet indoor comfort demands [

59,

60,

61,

62]. This pattern is largely driven by the long, hot, and humid summers, in contrast to the shorter, milder winters of the heating season. As a result, a building can be considered energy-efficient when its average energy consumption during the heating season is lower than during the cooling season.

In the United States, EUI remains the primary metric for assessing energy performance and is typically benchmarked against standards such as the U.S. Commercial Buildings Energy Consumption Survey (CBECS) [

63]. The CBECS survey provides comprehensive data on building characteristics and energy usage to evaluate efficiency. However, additional metrics that account for regional diversity are essential for more equitable and accurate assessments.

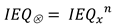

Thus, this study is the first to apply a two-dimensional energy utility quality (EUQ) metric, derived from EUI, to gauge building energy performance. These two dimensions are:

EUQa is computed using

Equation (15), where

and

represent the average EUI for the heating and cooling seasons, respectively.

Positive EUQa values indicate higher EUI during the heating season compared to the cooling season, suggesting inefficiency. Negative values suggest better efficiency during the heating season and potentially higher climate resilience. A quasi-neutral range, defined as −4.9% to +4.9%, reflects balanced seasonal energy use.

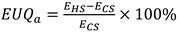

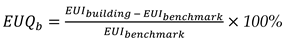

EUQb, the benchmark-based EUQ, is calculated as the numerical deviation of a building’s annual EUI from its adopted benchmark, according to

Equation (16).

For this study:

Case I reference benchmark = 57.9 kBTU/sqft (or 16.97 kWh/sqft),

Case II reference benchmark = 56.2 kBTU/sqft (or 16.47 kWh/sqft),

Case III reference benchmark = 59.6 kBTU/sqft (or 17.47 kWh/sqft),

based on the CBECS database for buildings with comparable functions. Positive EUQb values indicate that the building consumes more energy than the benchmark (relative inefficiency), whereas negative values indicate relative efficiency. A quasi-neutral range is defined as ±9.9% deviation from the benchmark.

EUQ Scoring System

Following preliminary consultations with building science and environmental policy experts—whose combined professional experience spans approximately 40 years—a scoring scale was developed to classify EUQ results, shown in

Table 2. This scale covers a continuum from extreme inefficiency to extreme efficiency, with higher efficiency levels aligning with the performance of top-rated certified green buildings [

12,

64,

65].

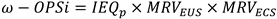

2.2.3. Variants of OPSi

The OPSi metric consists of five variants, including one subjective and four objective formulations. The subjective operational sustainability index (ω-OPSi) is calculated as the product of the subjective IEQ score (IEQp) and the percentage mean response values for energy usage satisfaction (MRV

EUS) and energy cost satisfaction (MRV

ECS), as presented in

Equation (17):

The combined MRVs can be interpreted as a perceptive valuation of EUQ. The importance of ω-OPSi lies in its ability to incorporate the perceptions of building stakeholders, ensuring their views on building performance are considered alongside—or even in the absence of—the objective OPSi variants. In essence, ω-OPSi serves as the “human sensor” for evaluating whole-building operational performance.

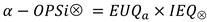

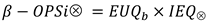

The first objective OPSi variant is α-OPSi⮾, defined as:

The second variant is β-OPSi⮾, expressed as:

The third variant is α-OPSix̄, defined as:

The fourth and final objective variant is β-OPSix̄, calculated as:

Together, these four objective variants enable a comprehensive assessment of building performance by integrating performance scores from the EUQ and IEQx dimensions using different aggregation strategies. To facilitate interpretation—particularly for the IEQ and OPSi performance metrics—a tiered evaluation system was employed to categorize performance scores into three levels:

Super-Optimal: 95% < Performance ≤ 100%

Optimal: 75% < Performance ≤ 95%

Suboptimal: 0% ≤ Performance ≤ 75%

3. Results

3.1. Indoor Environmental Quality

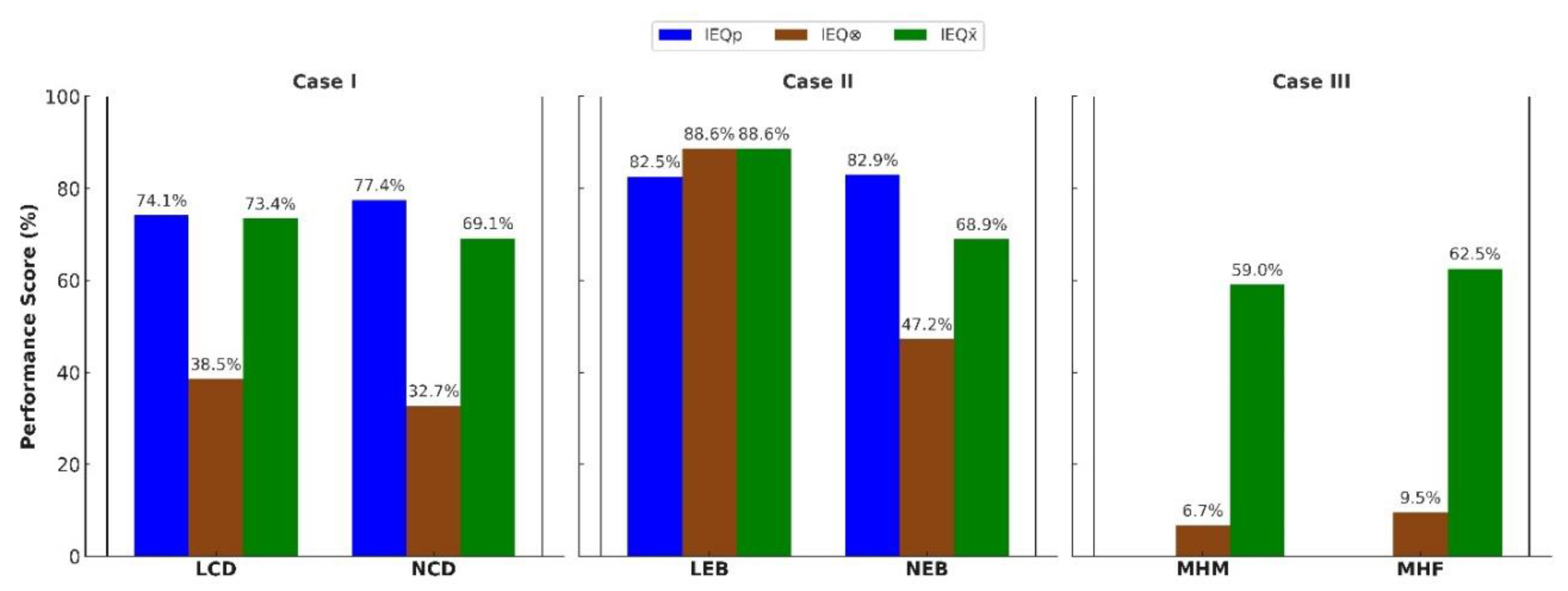

Figure 4 presents the comparative performance of the studied buildings across multiple metrics. In Case I, the subjective IEQ score (IEQp) was 74.1% for LCD and 77.4% for NCD. However, the product-based objective score (IEQ⮾) was lower, at 38.5% for LCD and 32.7% for NCD. For the mean-based objective score (IEQx̄), LCD achieved 73.4%, while NCD recorded 69.1%.

In Case II, LEB was slightly outperformed by NEB in IEQp, with the former at 82.5% and the latter at 82.9%. However, LEB surpassed NEB in both IEQ⮾ and IEQx̄, maintaining a consistent 88.6% in both metrics. For Case III, the multifamily housing occupied by males (MHM) and females (MHF) showed low IEQ⮾ scores, both below 10%, although MHF slightly outperformed MHM. Regarding IEQx̄, MHF again outperformed MHM, achieving 62.5% compared to 59.0% attained by MHM.

Overall, the non-certified dormitory attained an optimal IEQp rating, outperforming its LEED-certified counterpart. Both NEB and LEB attained optimal IEQp ratings; however, across all buildings, only LEB reached an optimal level in both IEQ⮾ and IEQx̄, with the others classified as suboptimal.

In regression analysis, key predictors of occupant satisfaction varied across cases. For LCD, artificial lighting emerged as the strongest positive predictor of overall experience satisfaction (p = 0.006), within a model explaining 63.5% of the variance (R² = 63.5%), alongside temperature and IAQ as significant factors (p < 0.05). In contrast, for NCD, acoustics was the sole significant predictor (p = 0.012) — with a model fit of R² = 64.5% — despite having only borderline significance in LCD (p = 0.071).

For LEB, the MLR model performed poorly, explaining only 2.1% of the variance (R² = 2.1%), with none of the IEQ components significantly influencing overall satisfaction; notably, lighting and air quality showed negative correlation coefficients. For NEB, only temperature had a statistically significant positive effect on overall satisfaction (p = 0.019), with the model explaining 43.5% of the variance (R² = 43.5%).

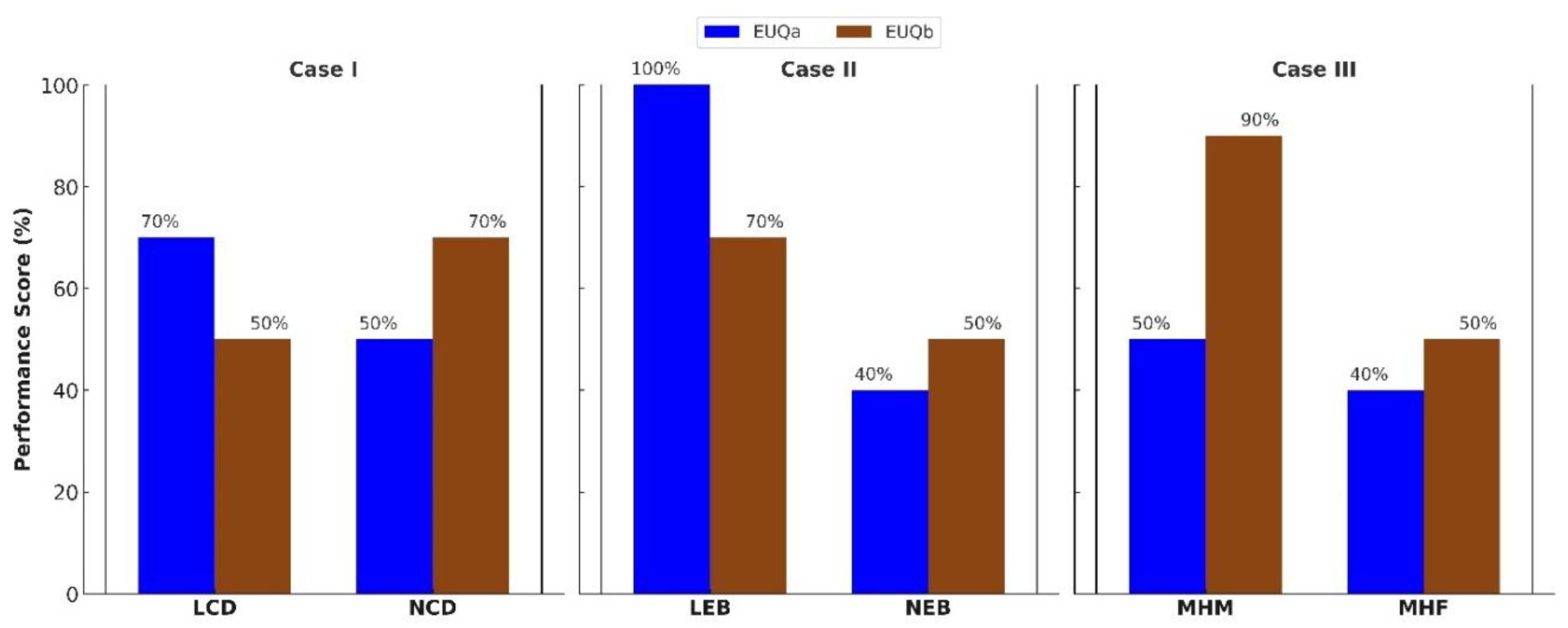

3.2. Energy Performance

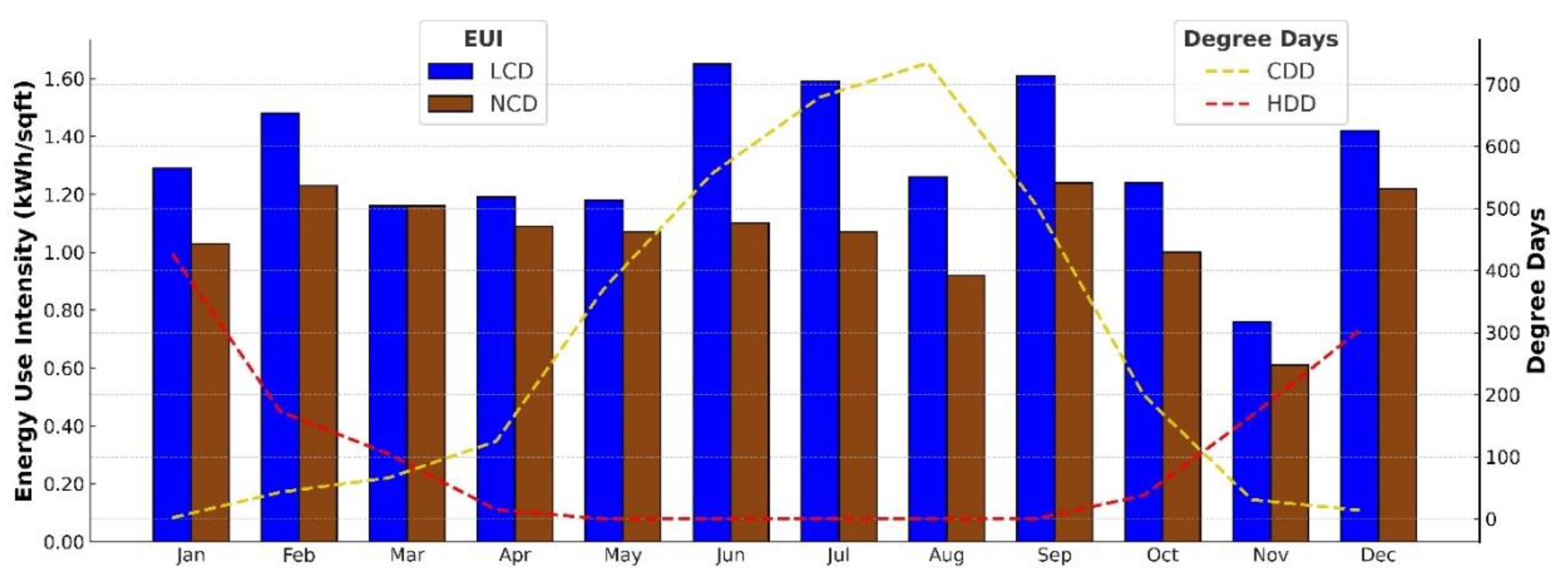

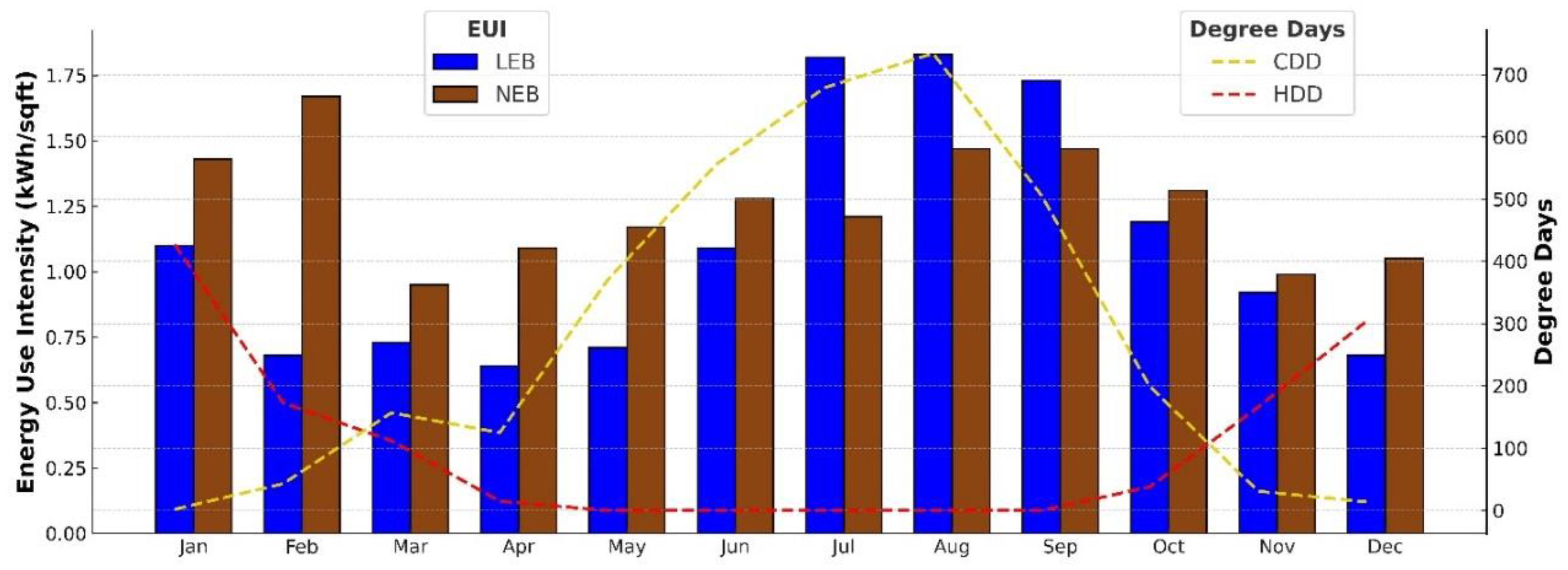

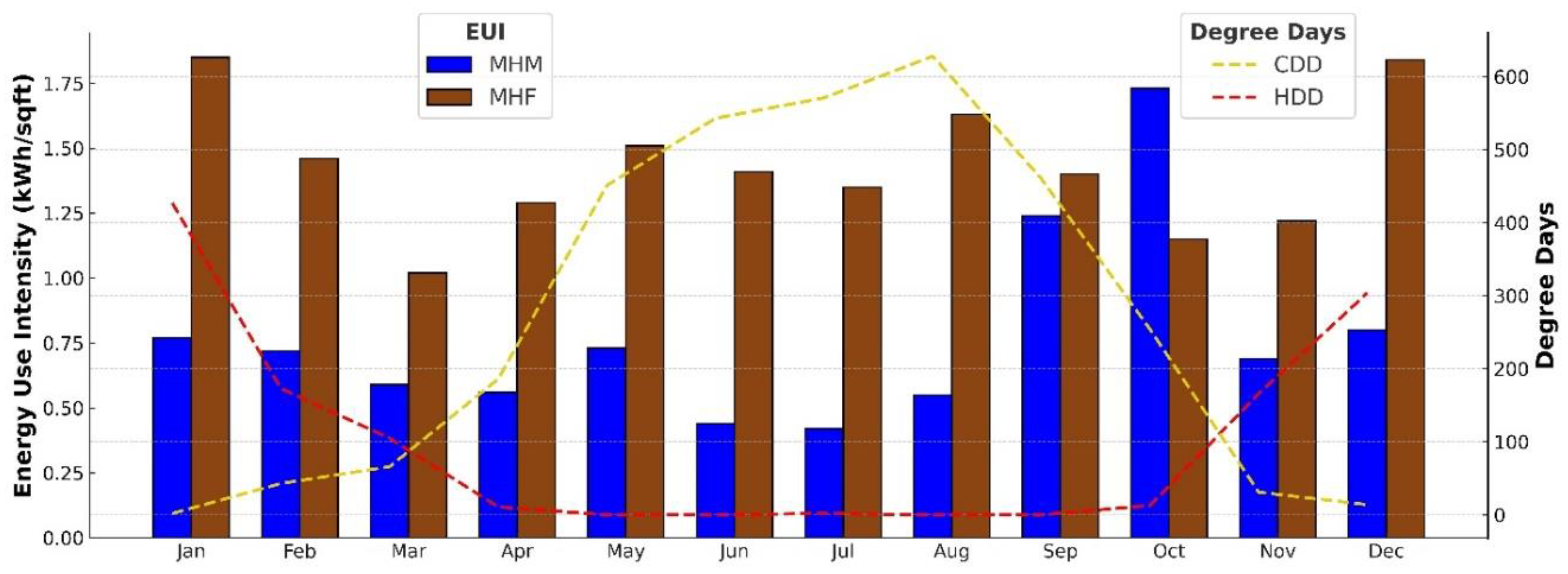

Variations in monthly EUI for the case study buildings are presented in

Figure 5,

Figure 6 and

Figure 7, revealing key trends: monthly EUI in LCD was often higher than in NCD; monthly EUI in LEB was consistently lower than in NEB; and monthly EUI in MHF was typically higher than in MHM. Interestingly, the two dormitories showed a reversal in their EUQa and EUQb outcomes, as illustrated in

Figure 8, which also includes results for the other cases. For LCD, a quasi-neutral performance was recorded for EUQb, indicating that its EUI was within a ±10% deviation from the benchmark. In contrast, NCD achieved a 70% score in EUQb, signaling an efficient performance. However, for EUQa, NCD exhibited a measurement deviation of −1.8% (i.e., quasi-neutral), indicating that the heating season EUI was slightly lower than the cooling season EUI.

Meanwhile, LEB outperformed NEB in both EUQa and EUQb, achieving an extremely efficient rating in EUQa and an efficient rating in EUQb. NEB, on the other hand, was either quasi-neutral or slightly inefficient across both energy metrics. A similar pattern was observed for MHF, while MHM outperformed MHF by achieving a quasi-neutral EUQa and a highly efficient EUQb, indicating that the EUI for MHM was at least 50% lower than the benchmark.

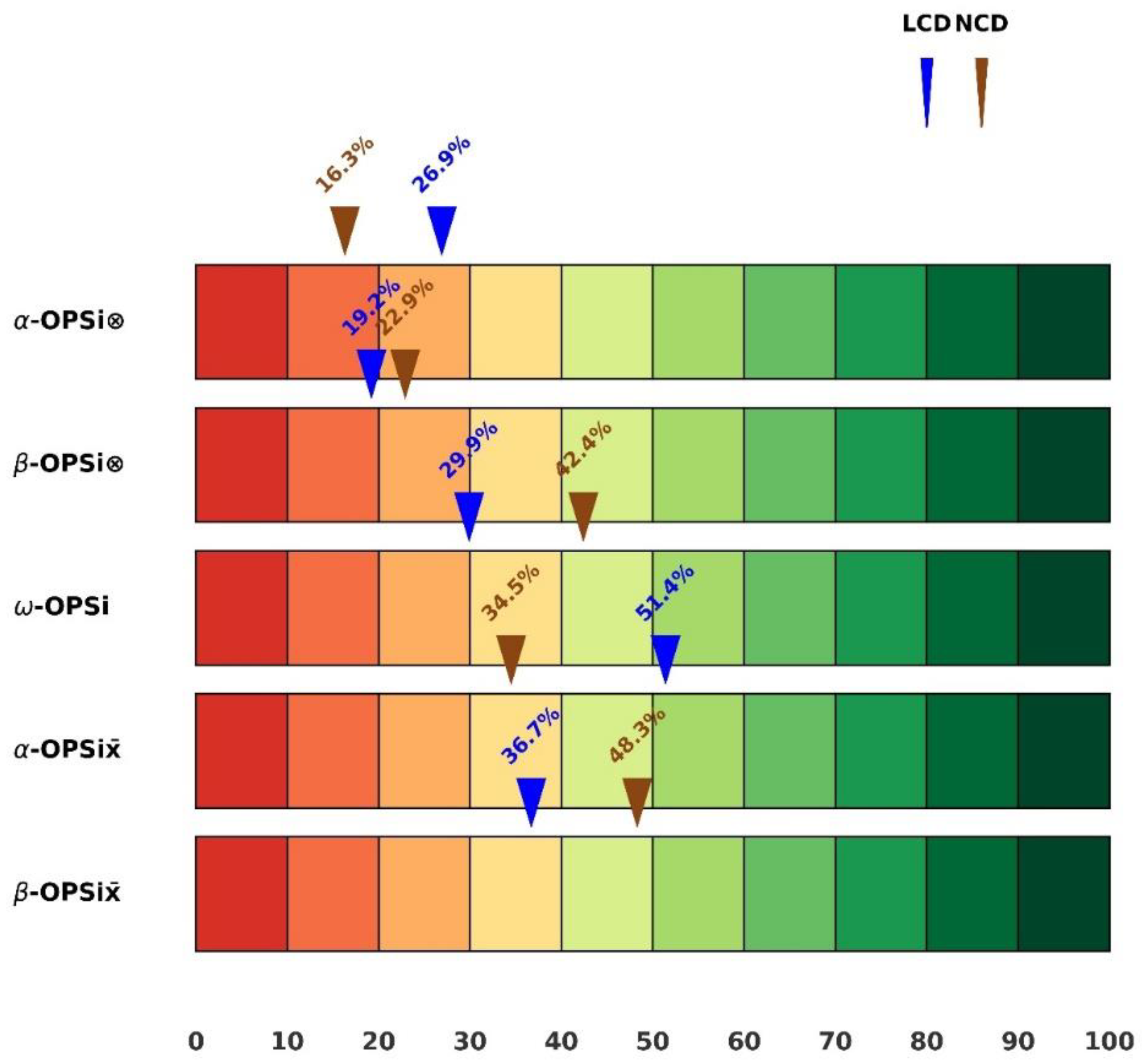

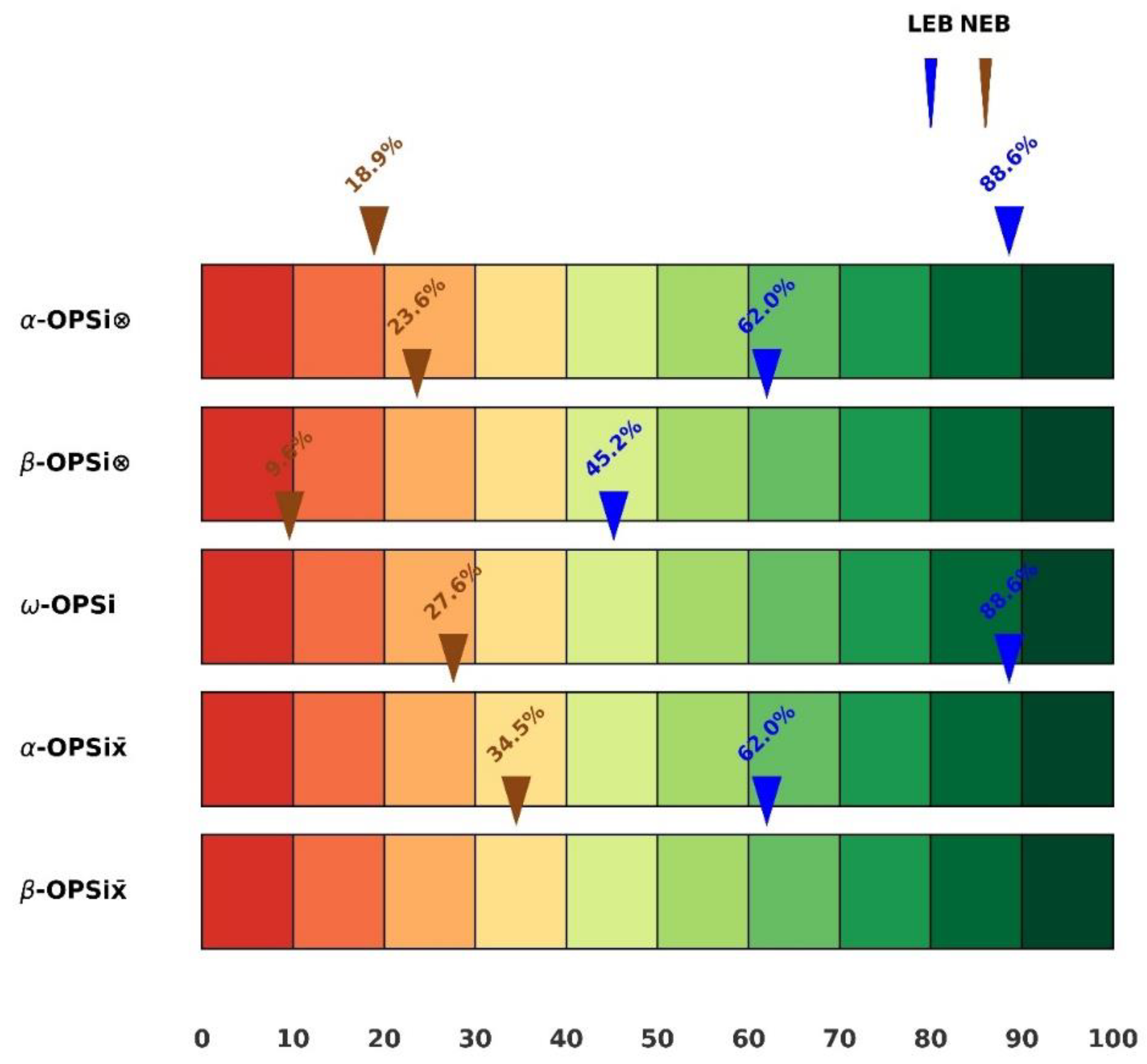

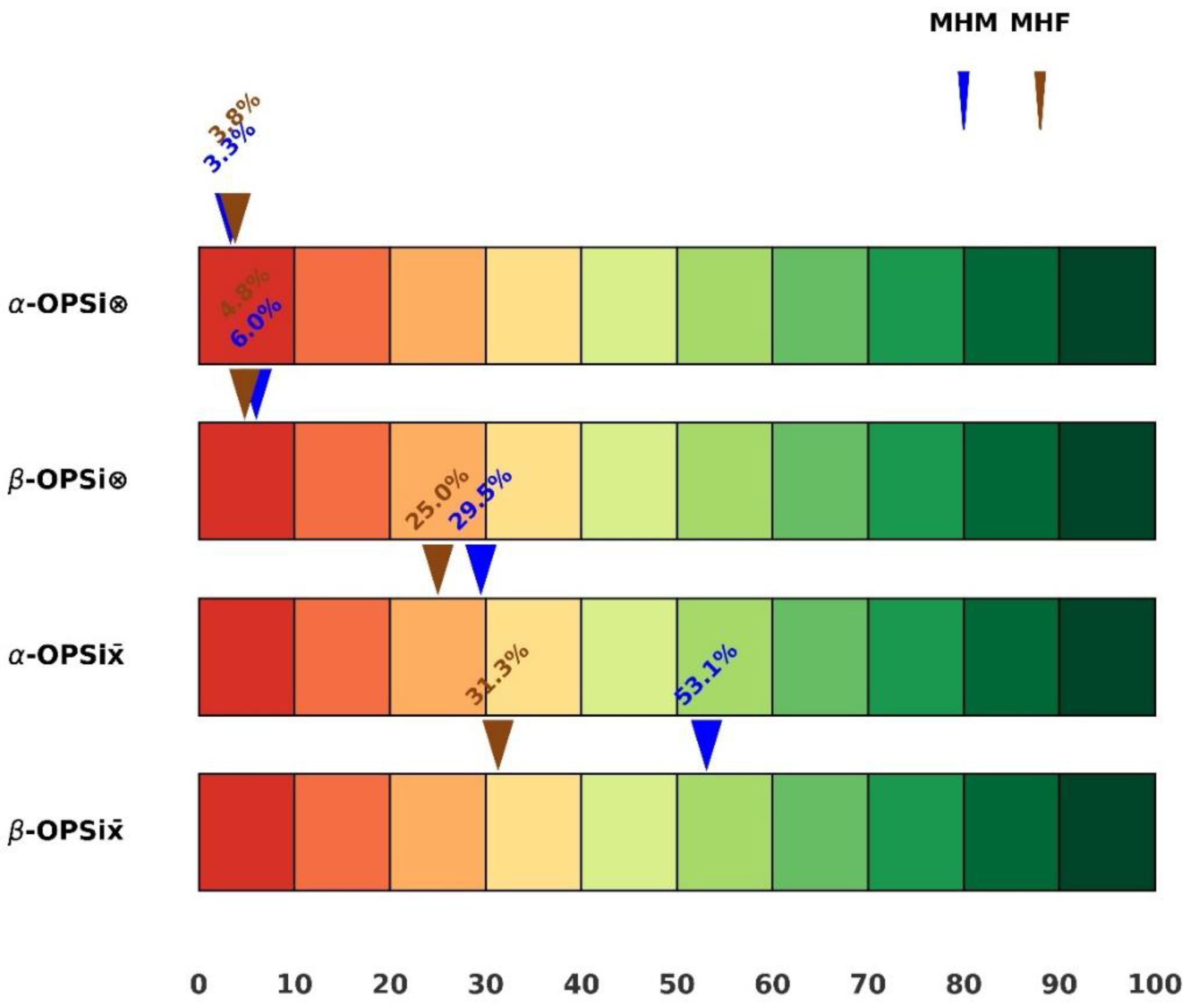

3.3. Operational Sustainability Index

Different dimensions of the OPSi metric and corresponding scores for comparable building types are presented in

Figure 9,

Figure 10 and

Figure 11. For the dormitory buildings, all derived scores were below 50%, except for LCD in terms of α-OPSix̄. While overall performance scores were generally low, LCD outperformed NCD in two dimensions: α-OPSi⮾ and α-OPSix̄. Meanwhile, ω-OPSi generally achieved higher values compared to the α- and β-OPSi⮾ variants but lower scores compared to the α- and β-OPSix̄ metrics.

Contrastingly, for the events buildings, ω-OPSi scores were lower than the other (non-subjective) OPSi variants. However, LEB consistently outperformed NEB across all dimensions, achieving its highest performance score at 88.6% for α-OPSi⮾ and α-OPSix̄, thus reaching an optimal α-OPSi performance. Similar to the results in the dormitory building case, only one OPSi score exceeded 50%, with MHM recording 53.1% for β-OPSix̄. Generally, MHM outperformed MHF across the various OPSi dimensions, except in α-OPSi⮾, where both recorded values below 5%.

4. Discussion

4.1. Discussion of Results

Overall, the results demonstrate the impact of adjusting metric combinations as well as the nuances between subjectivity-oriented and objectivity-oriented indices. For example, the satisfaction levels reported by occupants in LEED-certified buildings were lower than those in non-certified counterparts, even though the physical measurements of environmental variables suggested otherwise. This contrasts with the findings of Vosoughkhosravi et al. [

21], which reported superior subjective IEQ in LEED-certified dormitories. Moreover, the presence of negative coefficients and non-significant p-values underscores a drawback of integrating objective IEQ models using MLR-derived coefficients, as this approach may eliminate or undervalue IEQ variables that ideally should be considered together to capture composite IEQ.

Acoustic comfort and IAQ emerged as the most common factors negatively influencing objective IEQ scores in dormitories, while lighting was the primary issue in multifamily housing, and acoustic comfort again stood out in events buildings. Importantly, IEQ⮾ scores were consistently lower than IEQx̄ scores, reflecting that product-based integration of spatial IEQ performance is a more stringent approach than mean-based aggregation. The identical performance scores for LEB in both IEQ⮾ and IEQx̄, as well as in the pairs of α- and β-OPSi variants, highlight the challenge of comparing buildings with unequal numbers of measured spaces. For example, only one space was measured in LEB, whereas two were measured in NEB. This reinforces the need for future studies to adopt “apples-to-apples” comparisons between buildings — comparing the same number and type of spaces across cases to improve the fairness and generalizability of OPSi assessments.

The ω-OPSi metric offers valuable insights into how building stakeholders perceive energy usage and cost. For instance, occupants may report lower satisfaction in buildings with higher energy use, even when those buildings have greater operational capacity. While such biases are understandable from a residential occupant’s perspective, facility managers — particularly those overseeing and comparing multiple buildings — should assess satisfaction with a focus on EUI rather than raw energy use. Moreover, since cost dissatisfaction can stem from inflation or utility market fluctuations, these external factors should be carefully considered when interpreting survey responses.

The EUQa scores suggest that LEED-certified buildings demonstrated better climate resilience than their non-certified counterparts. To further advance sustainability and climate resilience, practical measures are recommended. These include adopting programmable or smart thermostats, installing dynamic window systems such as electrochromic glazing (which can reduce peak energy demand by 20–30% and save nearly 20% in primary energy) [

66,

67], or thermochromic glazing to control solar heat gain [

68]. Additional strategies such as soundproofing and noise-canceling technologies can help reduce HVAC-related noise, while improving ventilation and reducing exposure to materials that emit formaldehyde (such as certain building materials, cosmetics, laundry products, or unvented appliances) are also essential.

The importance of retrofitting with LED lighting, especially in housing units lacking this feature, cannot be overstated. Although payback periods vary, LED upgrades have consistently proven to enhance energy efficiency and operational sustainability [

69]. Given that HVAC systems are typically the most energy-intensive in humid subtropical climates like Baton Rouge, educating building occupants on optimal thermostat settings during occupancy, non-occupancy, and peak seasons is critical. Smart thermostats, as an advanced option, are strongly recommended across all case study buildings, along with routine inspection and maintenance of HVAC systems.

Findings related to MHM and MHF also open an important research avenue: exploring how apartment units occupied by different genders may vary in terms of climate resilience and energy efficiency. This study further lays the groundwork for debating whether EUQa or EUQb is a fairer metric for assessing energy performance. EUQa is particularly meaningful when researchers account for historical climate data and projections, making it adaptable across climates. EUQb, by contrast, offers a more generalized metric, though weather normalization should be applied when using cross-regional benchmarks.

Despite the important contributions of this study, several limitations should be acknowledged. These include the use of a fixed, though practical, air velocity value; the lack of occupant survey data and cross-seasonal environmental measurements in the multifamily housing cases; the non-uniform sample sizes across similar building comparisons; and the inability to conduct environmental monitoring campaigns in all dorm rooms.

4.2. Implications for Policy and Practice

This study highlights the importance of conducting fair building type comparisons and underscores the need for future applications to extend the OPSi framework to other building types, including office buildings. The multidimensional OPSi metric offers policymakers, particularly those in the green building sector, a flexible tool to select the most appropriate dimension for their context — whether they require a more stringent or a more adaptable performance indicator. Importantly, this work addresses one of the major criticisms of green certification systems: the lack of reliable methods to gauge the operational sustainability of buildings post-certification. By offering a clear and practical framework, this study provides both the concept and the means to fill that gap.

Moreover, adopting expensive green certifications may not be necessary to achieve operational sustainability. City governments, through education, incentives, institutional support, and regulatory enforcement, could promote the use of affordable OPSi-based certifications, making sustainability goals more accessible and scalable.

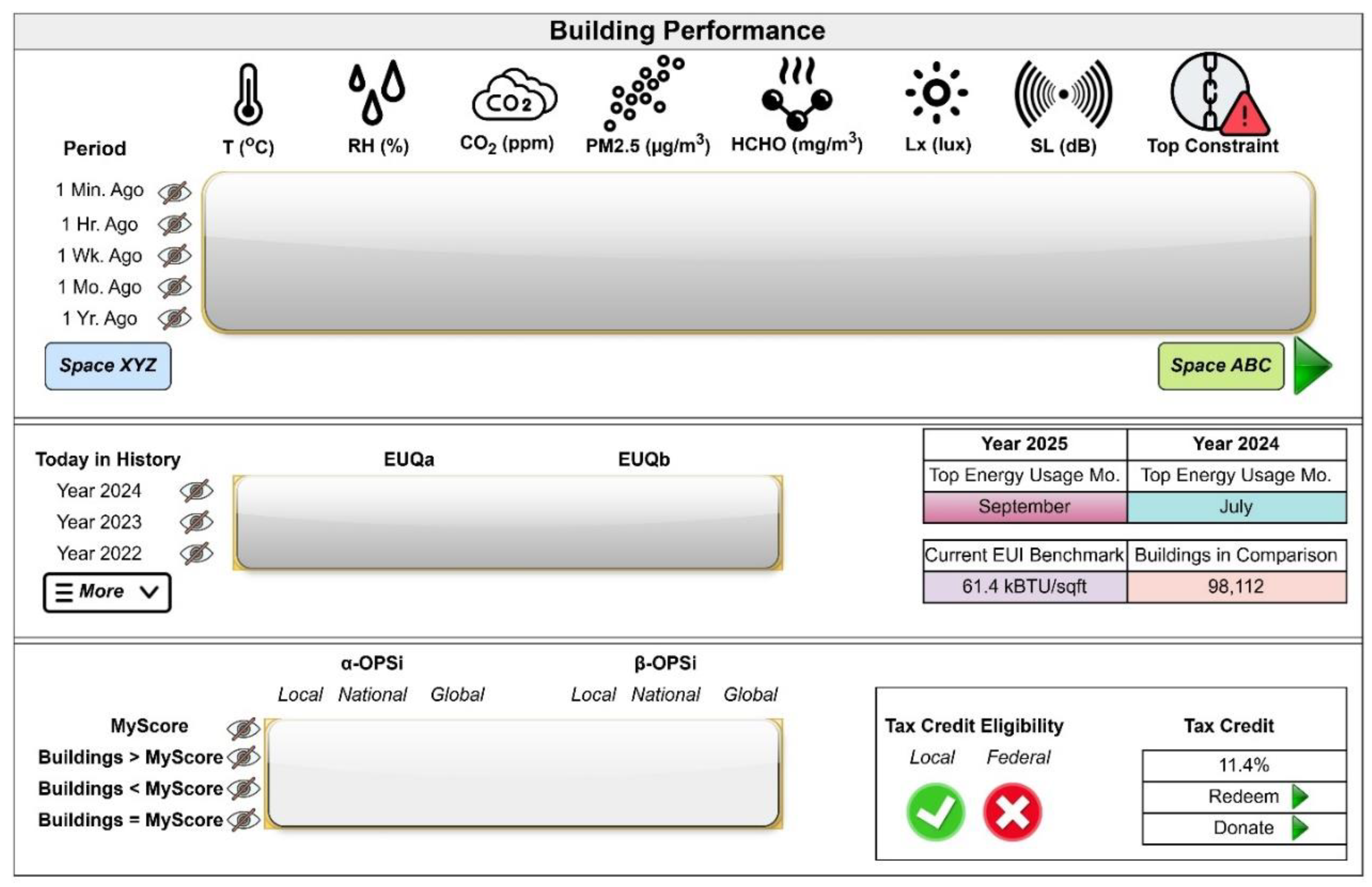

While future research should aim to apply the OPSi metric across larger building samples and varied contexts, there is also an opportunity for innovation on the technological front. Engineers are encouraged to develop multifunctional sensor systems capable of assessing objective IEQ across multiple building zones. Ideally, these systems would be integrated with smart meters to track EUQa and EUQb and connect to a cloud-based dashboard (see

Figure 12 for example dashboard elements). Such a dashboard could allow users to compare their building’s OPSi performance with that of others locally, nationally, or even globally, on an annual or biannual basis. A complementary tax credit system that rewards high-performing buildings could further strengthen the appeal and impact of such a system. Additionally, quarterly surveys of subjective IEQ satisfaction, especially in high-density buildings, are recommended to capture dynamic occupant feedback.

It is also critical that dashboard results highlight the specific factors contributing to lower IEQ scores and the months contributing to poor EUQ performance. This level of transparency would empower building owners and occupants to make informed, targeted decisions on cost-effective improvements.

However, the implementation of an integrated smart device system will face challenges, including costs, deployment logistics, and decisions on sensor placement — for example, determining optimal installation zones and heights within a building, and ensuring consistent measurement angles when comparing OPSi scores across similar buildings. Furthermore, if OPSi metrics are to be used for cross-country or cross-continental benchmarking, sensor equipment must comply with standardized industry specifications, ensuring equivalent detectability and resolution.

Lastly, while water efficiency remains an important pillar of sustainability, integrating it meaningfully into the OPSi framework presents challenges. Instead, future developments might consider incorporating basic water quality monitoring — for example, testing for lead (Pb) or coliform bacteria — to provide an added dimension of building health and performance.