5. Discussion

Table 18 shows the three-valued logic (i.e., “it appears to be positive,” “judgment suspended,” and “it appears to be negative”) based on the exact p-value and effect size for LEED project size, five individual LEED-EB v4.1 indicators, and “overall LEED” of LEED-EB v4.1 gold-certified projects certified in San Francisco, New York, and Washington, D.C. The data in

Table 18 are based on the summarized results of

Table 8,

Table 9,

Table 10,

Table 11,

Table 12,

Table 13 and

Table 14.

It should be noticed that project size in San Francisco differed from project size in New York City and Washington, D.C. Despite this difference between project size, there was no difference between three cites (“it seems to be negative”) in five individual LEED-EB v4.1 indicators: “transportation”, “water”, “energy”, “waste”, and “IEQ”. The only exception was in the “IEQ” indicator, in which San Francisco outperformed New York City. As a result, San Francisco surpassed New York and Washington in terms of overall LEED score.

According to LEED-EB v4.1 [

12], four of five indicators are completely based on measurements of their performance flows. “Transportation” indicator measures occupant-related traveled distances. Depending on the transportation mode (convenient car or public transportation), these traveling kilometers are then converted into CO

2 emissions. The “water” indicator measures potable water consumption for a year per resident and per unit area. The “energy” indicator measures occupants’ energy consumption during a year. Then, depending on the energy source (non-renewable or renewable), this consumption is converted into greenhouse gas (GHG) emissions. The “waste” indicator measures waste quantities (the total waste generated, including recycled and nonrecycled) of plastic, glass, and paper during a year.

The fifth indicator, “IEQ”, measures CO

2 emissions and total volatile organic compounds (TVOC) over a year. However, in addition, this indicator also requires conducting an occupant satisfaction survey. The measured CO

2 and TVOC, and the results of the occupant survey, are then converted into LEED points [

12]. Thus, given residents’ subjective assessment of indoor air quality, the IEQ indicator showing that San Francisco outperformed New York City should be interpreted with caution.

The similar results across all five individual indicators were expected, since the same type of project (office), all located in large central metro areas, according to urban–rural classification, was chosen for comparison across all three cities (

Table 4). However, despite this similarity in all five individual indicators, their medians in San Francisco were somewhat higher (“transportation: 13.0, “water”: 9.0, “energy”: 23, “waste”: 5.0, and “IEQ”: 18.0 points) than the corresponding medians in New York City and Washington, D.C. (“transportation: 12.0, “water”: 8.0, “energy”: 20.0/19.0, “waste”: 5.0/6.0, and “IEQ”: 16.0 points) (

Table 9,

Table 10,

Table 11,

Table 12 and

Table 13). As a result, “overall LEED” in San Francisco was higher (median: 69.0 points) compared to “overall LEED” in New York City and Washington, D.C. (median: 62.0 in both sites) (

Table 14).

San Francisco’s higher overall LEED score scores contrast with the much lower overall LEED scores (median: 62-65 points) from previous research that studied projects certified under previous LEED-EB versions (3 and 4) [

60]. However, the San Francisco result aligns with the LEED-EB v4.1 gold certification results previously observed in some European countries, such as Ireland, Germany, Italy, and Spain (median: 69.5–70.5 points) [

10]. It can be supposed that the approach of measuring all main LEED-EB v4.1 indicators has promising results due to addressing key factors such as “transportation”, “water”, “energy”, “waste”, and “IEQ”. This contrasts with the previous LEED-EB v4 version, where only “water” and “energy” were measurable indicators.

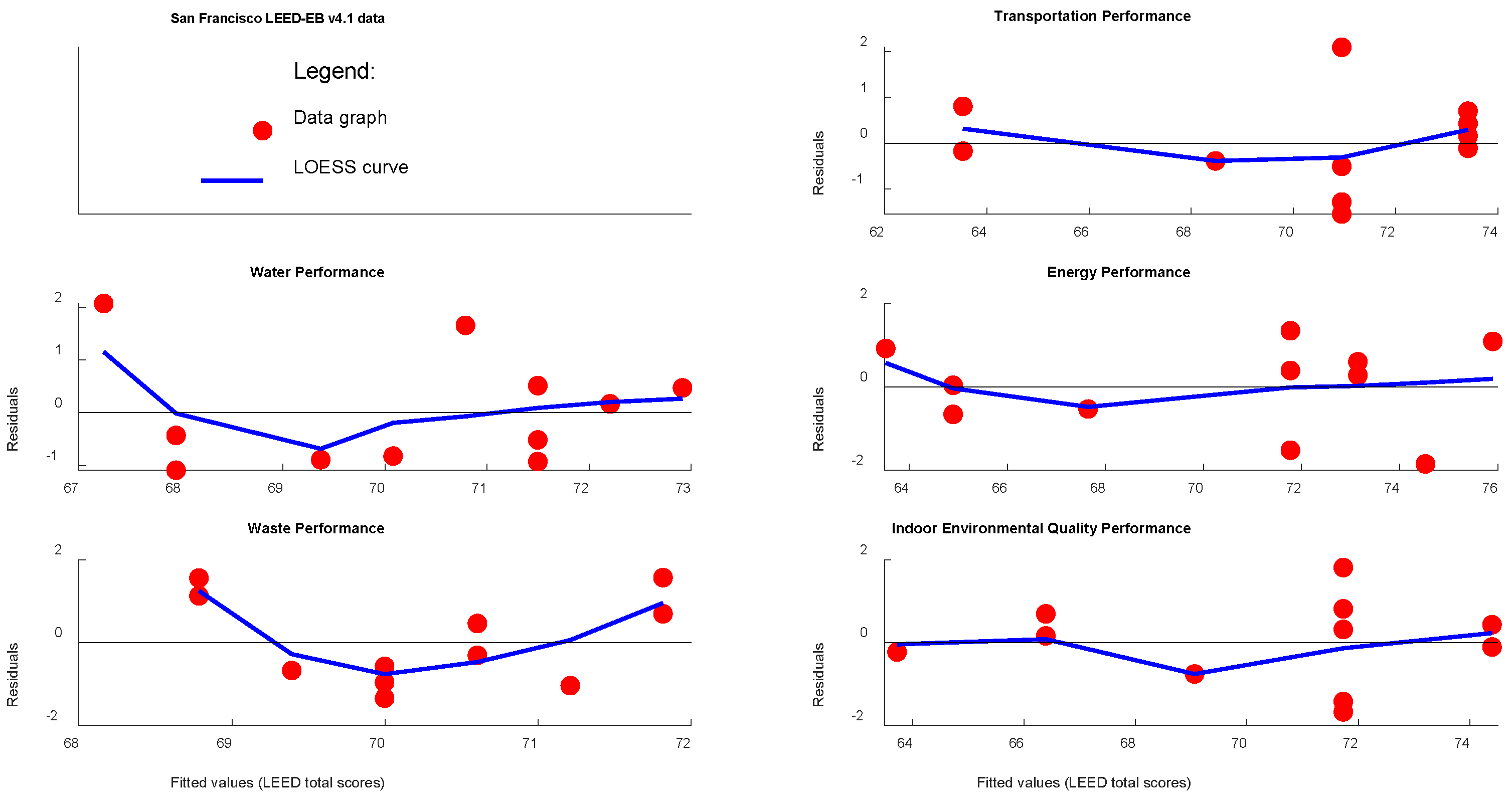

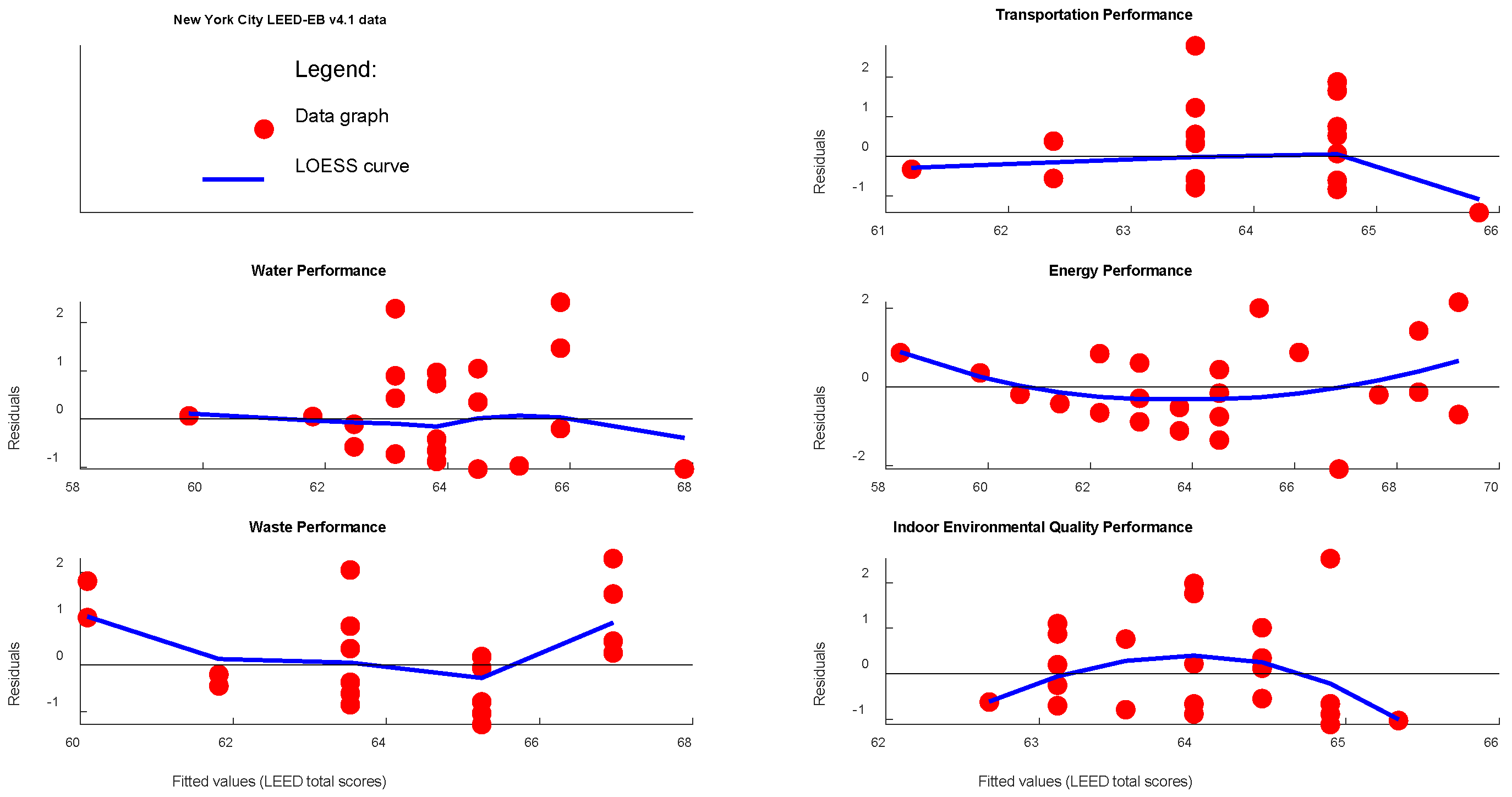

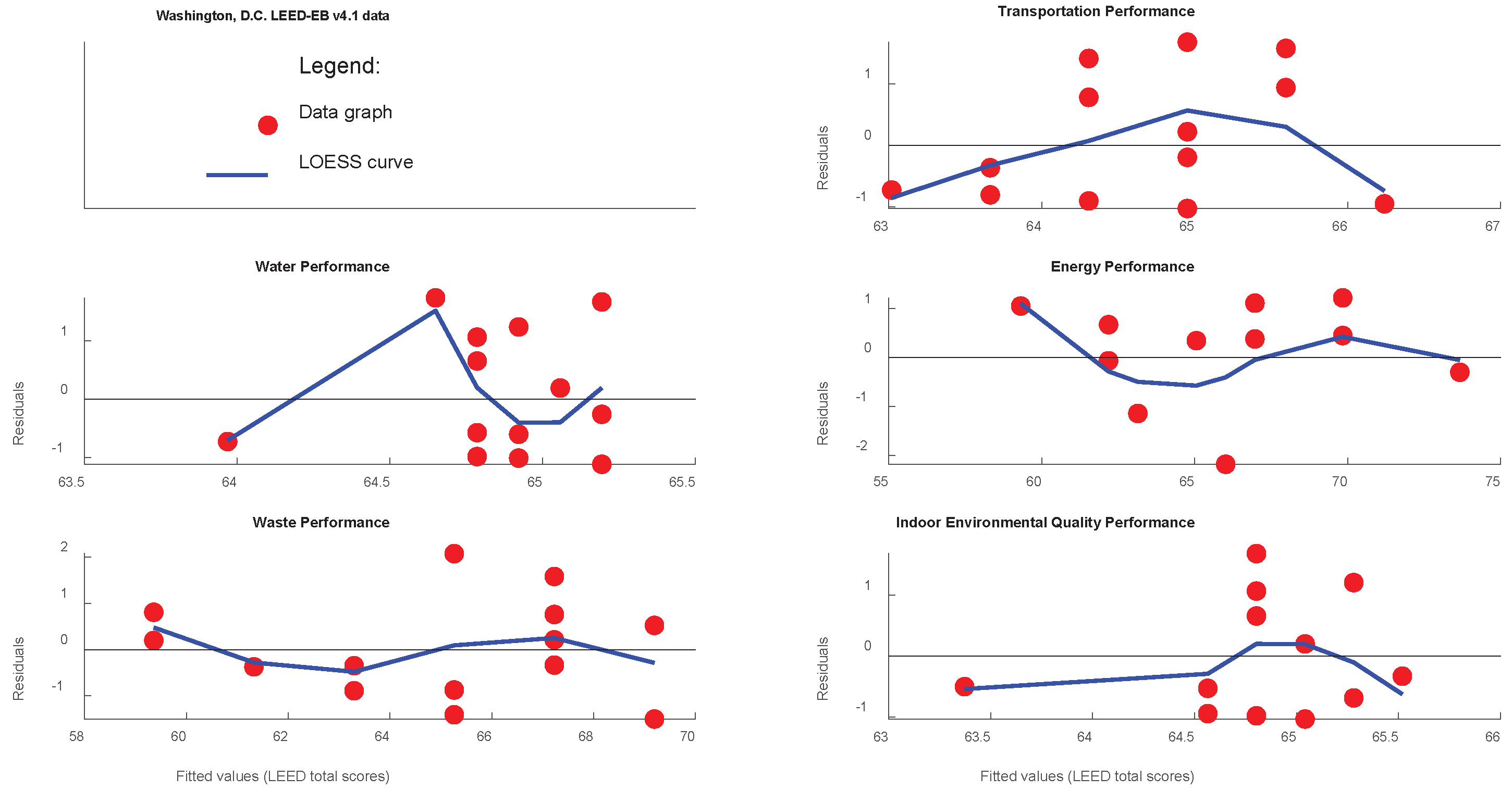

Table 19 shows the three-valued logic (i.e., “it appears to be positive,” “judgment suspended,” and “it appears to be negative”) based on the exact

p-value and

r for correlations between each of the five main LEED-EB v4.1 indicators and “overall LEED” for San Francisco, New York City, and Washington, D.C. In general, it can be supposed that the correlation between individual indicators and “overall LEED” can be explained by the availability of local green policies related to this indicator [

16].

The dominant significant positive correlation was noticed in all three sites between “energy” and “overall LEED”. The correlations between “energy” and “overall LEED” have been well-established in the literature [17,29,30,32;33]. This is due to the largest number of maximum points allowed by this credit [

17]. Regarding this indicator, San Francisco has a local energy efficiency code, such as the Green Building Code (launched in 2008), which is connected to the LEED system; in addition, this city prioritizes renewable energy due to the current Renewables Portfolio Standard practiced in California since 2013 [

61]. Aiming for full decarbonization, California has set a goal to reach 90% renewable energy use by 2035 [

62]. New York City follows New York State energy-related policies that aim to reduce emissions by 40% by 2030 [

63]. Since 2014, Washington, D.C., has been a member of the Carbon Neutral Cities Alliance (CNCA) governance network, which is a pioneer of urban “deep decarbonization” [

61].

The three additional correlations were between “transportation” and “overall LEED” in San Francisco, “waste” and “overall LEED” in Washington, D.C., and “IEQ” and “overall LEED” in San Francisco. However, in the literature, there are few studies on the correlation between these main LEED indicators and “overall LEED” [

32]. For example, Lee et al. [

64] found that a decrease in the LT category resulted in a decrease in overall LEED scores.

Regarding the “transportation” indicator, in 2006, California launched the Global Warming Solutions Act to reduce its GHG emissions by 40% by 2030. Transportation emissions comprise a significant portion of total emissions. In this respect, Kim et al. [

65] found that in San Francisco, CO

2 emissions decreased by about 8% during 2018-2020. The authors concluded that this result stemmed from policy-driven changes decreasing transportation-related GHG emissions. Jin et al. [

66] studied 12 major American cities in terms of their status as a 15-minute walking city and concluded that San Francisco and New York City are the most suitable. A 15-minute travel time for daily activities through walking, cycling, or public transit trips helps to greatly decrease CO

2 emissions related to transportation.

Regarding the “waste” indicator, an increase in this indicator was correlated with “overall LEED” only in Washington, D.C. In the US, many municipalities initiate policies to decrease solid waste going into landfills. For example, New York City aims to send zero waste to landfills by 2030 [

67]. However, Tonjes et al. [

68] analyzed municipal solid waste in 2021 at 11 locations in New York State and concluded that only 18.2% of paper–glass–metal–plastic waste was recycled. This is reflected in the relatively low results obtained by LEED-EB v4.1-certified projects revealed in this study.

“IEQ” is a very important indicator that improves occupants’ quality of life and increases property value [

69]. However, in our study, “IEQ” was only correlated with “overall LEED” in one of the three cities, San Francisco. As mentioned earlier, the IEQ score depends not only on CO

2 and TVOC measurements (objective measures, 50% of IEQ score), but also on occupant satisfaction ratings (subjective measures, 50% of IEQ score) [

12]. The effectiveness of subjective assessments depends not only on the quality of the survey design (what questions are asked) but also on how and when these questions are asked [

70]. In conclusion, it should be noted that the IEQ value may vary across projects due to differences in subjective perception between different people in the building, despite the same physical measurements.

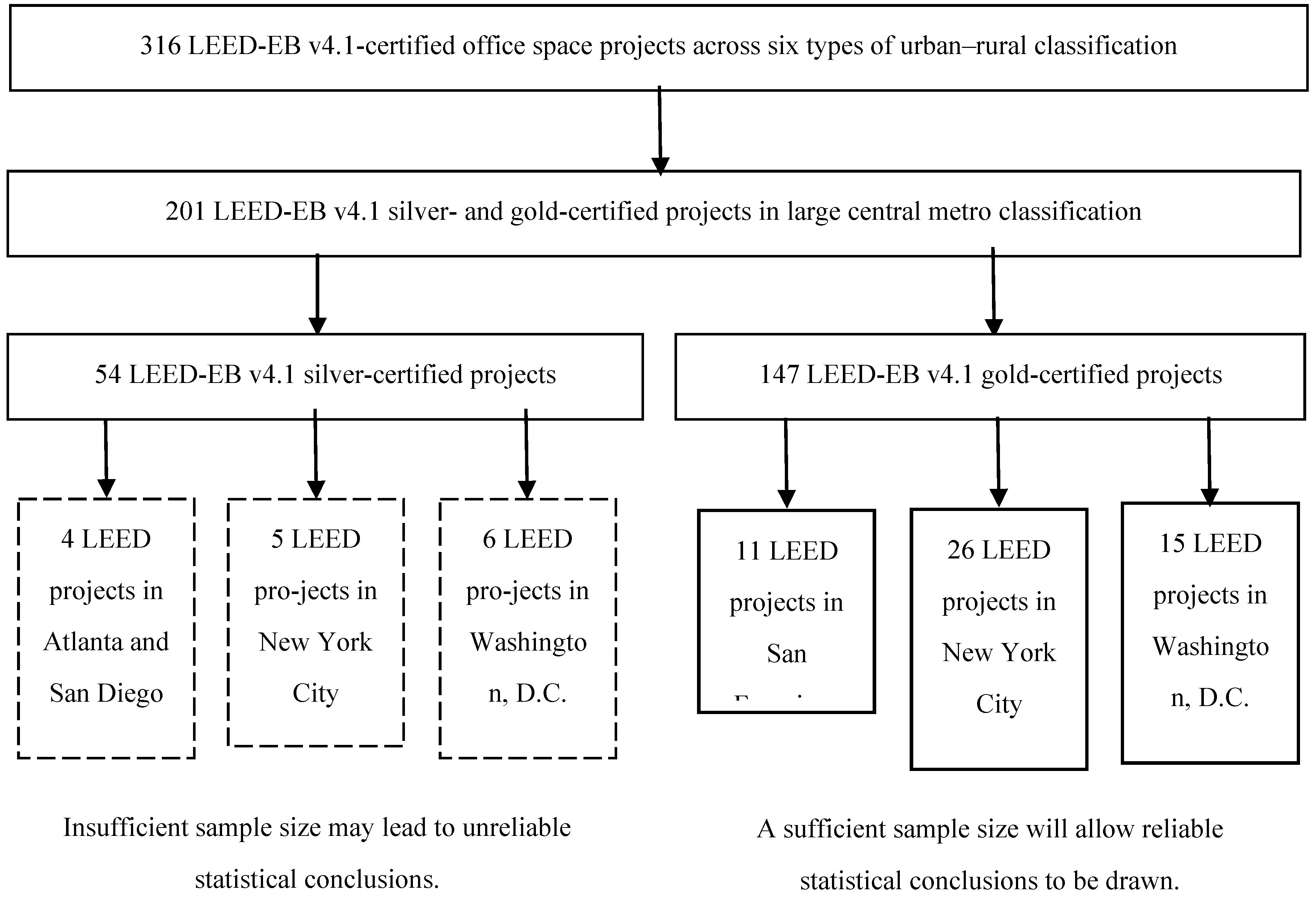

Figure 1.

Flow chart of the study design. Boxes with dotted lines indicate sample sizes that are inappropriate for significance tests. Boxes with solid lines indicate sample sizes appropriate for significance tests.

Figure 1.

Flow chart of the study design. Boxes with dotted lines indicate sample sizes that are inappropriate for significance tests. Boxes with solid lines indicate sample sizes appropriate for significance tests.

Table 1.

Four types of comparison of LEED-certified projects in the US.

Table 1.

Four types of comparison of LEED-certified projects in the US.

| LEED-NC v4-certified projects |

Comparison of independent groups |

[Ref] |

| LEED-NC v4-certified projects encompass all building types |

Nine U.S. climate regions |

[17] |

| LEED NC v2009-certified hotel projects |

Four certification levels |

[23] |

| LEED-CI v4 gold-certified office projects in California |

Low vs. High Transport Accessibility |

[26] |

| LEED-CI v4 gold-certified office projects in New York City |

Low vs. High energy performance in building |

[27] |

Table 2.

A summary of the correlation results between individual LEED category scores and overall LEED scores in the United States using the correlation coefficient (r) across six publications.

Table 2.

A summary of the correlation results between individual LEED category scores and overall LEED scores in the United States using the correlation coefficient (r) across six publications.

| LEED-Certified Projects |

LT |

SS |

WE |

EA |

MRs |

IEQ |

RP |

Ref. |

| LEED-NC v4-certified projects encompass all building types |

0.35 |

0.36 |

0.30 |

0.61 |

0.39 |

0.37 |

0.40 |

[17] |

| LEED-NC v3-certified university residence hall projects |

– |

0.45 |

0.28 |

0.80 |

0.35 |

0.28 |

– |

[29] |

| LEED-NC v3-certified multifamily residential projects |

– |

0.40 |

0.25 |

0.68 |

0.23 |

0.26 |

– |

[30] |

| LEED-NC 2009 v3-certified multifamily residential projects |

– |

– |

– |

– |

– |

– |

0.38 |

[31] |

| LEED-NC v4-certified multifamily residential projects |

0.43 |

0.28 |

0.23 |

0.52 |

0.20 |

0.43 |

– |

[32] |

| LEED-HC (healthcare) v4.1-certified projects |

– |

0.46 |

0.58 |

0.60 |

0.33 |

0.39 |

– |

[33] |

Table 3.

National Center for Health Statistics’ (NCHS) urban–rural classification in the United States.

Table 3.

National Center for Health Statistics’ (NCHS) urban–rural classification in the United States.

| NCHS Urban–Rural Group |

Classification Rules |

| Metropolitan counties |

Large central metro |

Counties in MSAs 1 with a population of 1 million or more |

| Large fringe metro |

Counties in MSAs 1 with a population of 1 million or more that do not qualify as large central metro counties |

| Medium metro |

Counties in MSAs 1 with populations of 250,000–999,999 |

| Small metro |

Counties in MSAs 1 with populations less than 250,000 |

| Nonmetropolitan counties |

Micropolitan |

Counties in micropolitan statistical areas |

| Noncore |

Nonmetropolitan counties that do not qualify as micropolitan |

Table 4.

Distribution of LEED-EB v4.1-certified office projects across six types of urban–rural classification.

Table 4.

Distribution of LEED-EB v4.1-certified office projects across six types of urban–rural classification.

| Certification level |

Nonmetropolitan counties |

Metropolitan counties |

| Noncore |

Micropolitan |

Small metro |

Medium metro |

Large fringe metro |

Large central metro |

| Certified |

0 |

0 |

0 |

2 |

3 |

5 |

| Silver |

0 |

0 |

1 |

7 |

27 |

54 |

| Gold |

0 |

0 |

1 |

22 |

43 |

147 |

| Platinum |

0 |

0 |

0 |

0 |

1 |

3 |

Table 5.

Distribution of LEED-EB v4.1 silver- and gold-certified office projects among most popular cities located in “large central metro” counties.

Table 5.

Distribution of LEED-EB v4.1 silver- and gold-certified office projects among most popular cities located in “large central metro” counties.

| Certification level |

Atlanta |

San Diego |

San Francisco |

New York City |

Washington, D.C |

| Silver |

4 |

4 |

2 |

5 |

6 |

| Gold |

2 |

6 |

11 |

26 |

15 |

Table 6.

Cohen’s d and Cliff’s δ effect sizes in absolute value.

Table 6.

Cohen’s d and Cliff’s δ effect sizes in absolute value.

| Negligible |

Small |

Medium |

Large |

Reference |

| |δ| < 0.147 |

0.147 ≤ |δ| < 0.33 |

0.33 ≤ |δ| < 0.474 |

|δ| ≥ 0.474 |

[46] |

Table 7.

Interpretation of the correlation coefficient in absolute value (|r|).

Table 7.

Interpretation of the correlation coefficient in absolute value (|r|).

| Coefficient |

Very Weak |

Weak |

Moderate |

Strong |

Very Strong |

Reference |

| |r| |

0.00–0.19 |

0.20–0.39 |

0.40–0.59 |

0.60–0.79 |

0.80–1.00 |

[51] |

Table 8.

LEED-EB v4.1-certified office project sizes in three US cities.

Table 8.

LEED-EB v4.1-certified office project sizes in three US cities.

| LEED-EB v4.1 gold-certified office projects |

San Francisco |

New York City |

Washington, D.C. |

San Francisco vs. New York City |

San Francisco vs. Washington, D.C. |

New York City vs. Washington, D.C. |

| Median, 25–75th Percentiles (IQR/M) |

δ |

p-value |

δ |

p-value |

δ |

p-value |

| Project size (m2) |

9,369, 7,912–18,054 (1.08) |

45,766, 19,449–64,824 (0.99) |

25,448, 21,300–35,343 (0.55) |

-0.80 |

<0.001 |

-0.76 |

<0.001 |

0.29 |

0.133 |

Table 9.

“Transportation” of LEED-EB v4.1-certified office project in three US cities.

Table 9.

“Transportation” of LEED-EB v4.1-certified office project in three US cities.

| Performance |

Max Points |

San Francisco |

New York City |

Washington, D.C. |

San Francisco vs. New York City |

San Francisco vs. Washington, D.C. |

New York City vs. Washington, D.C. |

| Median, 25–75th Percentiles (IQR/M) |

δ |

p-value |

δ |

p-value |

δ |

p-value |

| Transportation |

14 |

13.0, 12.2–14.0 (0.13) |

12.0, 12.0–13.0 (0.08) |

12.0, 11.0–13.0 (0.17) |

0.33 |

0.092 |

0.33 |

0.151 |

0.20 |

0.283 |

Table 10.

“Water” of LEED-EB v4.1 gold-certified office space projects in three US cities.

Table 10.

“Water” of LEED-EB v4.1 gold-certified office space projects in three US cities.

| Performance |

Max Points |

San Francisco |

New York City |

Washington, D.C. |

San Francisco vs. New York City |

San Francisco vs. Washington, D.C. |

New York City vs. Washington, D.C. |

| Median, 25–75th Percentiles (IQR/M) |

δ |

p-value |

δ |

p-value |

δ |

p-value |

| Water |

15 |

9.0, 8.0–12.5 (0.50) |

8.0, 7.0–9.0 (0.25) |

8.0, 7.2–9.0 (0.22) |

0.30 |

0.153 |

0.27 |

0.243 |

-0.02 |

0.918 |

Table 11.

“Energy” of LEED-EB v4.1 gold-certified office space projects in three US cities.

Table 11.

“Energy” of LEED-EB v4.1 gold-certified office space projects in three US cities.

| Performance |

Max Points |

San Francisco |

New York City |

Washington, D.C. |

San Francisco vs. New York City |

San Francisco vs. Washington, D.C. |

New York City vs. Washington, D.C. |

| Median, 25–75th Percentiles (IQR/M) |

δ |

p-value |

δ |

p-value |

δ |

p-value |

| Energy |

33 |

23.0, 18.5–24.0 (0.24) |

20.0, 18.0–23.0 (0.25) |

19.0, 18.0–23.0 (0.26) |

0.23 |

0.280 |

0.20 |

0.403 |

-0.03 |

0.877 |

Table 12.

“Waste” of LEED-EB v4.1 gold-certified office space projects in three US cities.

Table 12.

“Waste” of LEED-EB v4.1 gold-certified office space projects in three US cities.

| Performance |

Max Points |

San Francisco |

New York City |

Washington, D.C. |

San Francisco vs. New York City |

San Francisco vs. Washington, D.C. |

New York City vs. Washington, D.C. |

| Median, 25–75th Percentiles (IQR/M) |

δ |

p-value |

δ |

p-value |

δ |

p-value |

| Waste |

8 |

5.0, 4.2–6.8 (0.50) |

5.0, 4.0–6.0 (0.40) |

6.0, 5.0–7.0 (0.33) |

0.07 |

0.750 |

-0.13 |

0.594 |

-0.25 |

0.188 |

Table 13.

“IEQ” of LEED-EB v4.1 gold-certified office space projects in three US cities.

Table 13.

“IEQ” of LEED-EB v4.1 gold-certified office space projects in three US cities.

| Performance |

Max Points |

San Francisco |

New York City |

Washington, D.C. |

San Francisco vs. New York City |

San Francisco vs. Washington, D.C. |

New York City vs. Washington, D.C. |

| Median, 25–75th Percentiles (IQR/M) |

δ |

p-value |

δ |

p-value |

δ |

p-value |

| IEQ |

20 |

18.0, 16.2–18.0 (0.10) |

16.0, 14.0–17.0 (0.19) |

16.0, 16.0–17.8 (0.11) |

0.53 |

0.009 |

0.38 |

0.090 |

-0.20 |

0.283 |

Table 14.

“Overall LEED” of LEED-EB v4.1 gold-certified office space projects in three US cities.

Table 14.

“Overall LEED” of LEED-EB v4.1 gold-certified office space projects in three US cities.

| Performance |

Min Points 1

|

San Francisco |

New York City |

Washington, D.C. |

San Francisco vs. New York City |

San Francisco vs. Washington, D.C. |

New York City vs. Washington, D.C. |

| Median, 25–75th Percentiles (IQR/M) |

δ |

p-value |

δ |

p-value |

δ |

p-value |

| LEED total |

60 |

69.0, 66.0–74.8 (0.13) |

62.0, 60.0–67.0 (0.11) |

62.0, 60.5–69.5 (0.15) |

0.66 |

0.001 |

0.59 |

0.001 |

-0.13 |

0.491 |

Table 15.

Correlation between “overall LEED” and each of the five “individual LEED” in LEED-EB v4.1 gold-certified office projects in San Francisco.

Table 15.

Correlation between “overall LEED” and each of the five “individual LEED” in LEED-EB v4.1 gold-certified office projects in San Francisco.

| Country |

Performance |

r |

p-value |

| Variable 1 |

Variable 2 |

| San Francisco |

Overall LEED vs. |

Transportation |

0.69 a

|

0.018 |

| Water |

-0.35 b

|

0.294 |

| Energy |

0.81 a

|

0.003 |

| Waste |

0.20 a

|

0.555 |

| IEQ |

0.61 b

|

0.049 |

Table 16.

Correlation between “overall LEED” and each of the five “individual LEED” in LEED-EB v4.1 gold-certified office projects in New York.

Table 16.

Correlation between “overall LEED” and each of the five “individual LEED” in LEED-EB v4.1 gold-certified office projects in New York.

| Country |

Performance |

r |

p-value |

| Variable 1 |

Variable 2 |

| New York City |

Overall LEED vs. |

Transportation |

0.34 b

|

0.093 |

| Water |

0.32 b

|

0.116 |

| Energy |

0.61 b

|

0.001 |

| Waste |

0.40 b

|

0.044 |

| IEQ |

0.24 b

|

0.245 |

Table 17.

Correlation between “overall LEED” and each of the five “individual LEED” in LEED-EB v4.1 gold-certified office projects in Washington, D.C.

Table 17.

Correlation between “overall LEED” and each of the five “individual LEED” in LEED-EB v4.1 gold-certified office projects in Washington, D.C.

| Country |

Performance |

r |

p-value |

| Variable 1 |

Variable 2 |

| Washington DC |

Overall LEED vs. |

Transportation |

0.30 b

|

0.275 |

| Water |

0.07 b

|

0.816 |

| Energy |

0.83 a

|

<0.001 |

| Waste |

0.65 a

|

0.009 |

| IEQ |

0.07 b

|

0.801 |

Table 18.

Pairwise comparative analysis in project size, five main LEED-EB v4.1 indicators, and overall LEED between three cities in terms of “it seems to be positive” (A), “judgment is suspended” (B), and “it seems to be negative” (C).

Table 18.

Pairwise comparative analysis in project size, five main LEED-EB v4.1 indicators, and overall LEED between three cities in terms of “it seems to be positive” (A), “judgment is suspended” (B), and “it seems to be negative” (C).

| Indicators |

San Francisco vs. New York City |

San Francisco vs. Washington, D.C. |

New York City vs. Washington, D.C. |

| A |

B |

C |

A |

B |

C |

A |

B |

C |

| Project size |

✓ |

|

|

✓ |

|

|

|

|

✓ |

| Transportation |

|

|

✓ |

|

✓ |

|

|

|

✓ |

| Water |

|

|

✓ |

|

✓ |

|

|

|

✓ |

| Energy |

|

|

✓ |

|

✓ |

|

|

|

✓ |

| Waste |

|

|

✓ |

|

✓ |

|

|

|

✓ |

| IEQ |

✓ |

|

|

|

✓ |

|

|

|

✓ |

| Overall LEED |

✓ |

|

|

✓ |

|

|

|

|

✓ |

Table 19.

Frequency analysis of inferential conclusions for correlations between five main LEED-EB v4.1 indicators and overall LEED in terms of “it seems to be positive” (A), “judgment is suspended” (B), and “it seems to be negative” (C) in three sites.

Table 19.

Frequency analysis of inferential conclusions for correlations between five main LEED-EB v4.1 indicators and overall LEED in terms of “it seems to be positive” (A), “judgment is suspended” (B), and “it seems to be negative” (C) in three sites.

| City |

Energy |

Transportation |

Waste |

IEQ |

Water |

| A |

B |

C |

A |

B |

C |

A |

B |

C |

A |

B |

C |

A |

B |

C |

| San Francisco |

✓ |

|

|

✓ |

|

|

|

|

✓ |

✓ |

|

|

|

|

✓ |

| New York City |

✓ |

|

|

|

✓ |

|

|

✓ |

|

|

|

✓ |

|

|

✓ |

| Washington, D.C. |

✓ |

|

|

|

|

✓ |

✓ |

|

|

|

|

✓ |

|

|

✓ |