1. Introduction

The accelerating population growth worldwide, changes in consumption habits, deforestation, acid rain, global warming, and the thinning of the ozone layer are having negative impacts on the natural environment, and one of the main reasons for these processes is the prevalence of poorly designed structures that are not environmentally friendly [1,2]. Various green building certification systems have been developed to minimize the environmental impacts of the construction industry [3,4]. These systems ensure that buildings fulfill their environmental responsibilities while also contributing to the creation of prestigious buildings with high energy efficiency [5,6,7].

The construction industry has become critical for environmental sustainability, accounting for approximately 40% of the total raw material consumption worldwide [8]. The increasing construction volume and consumption trends are contributing to environmental pollution. Healthcare facilities, which are actively used at all hours of the day and impact human health, also play a significant role in this process [9,10].

Energy conservation is a major objective in designing and operating green buildings [11]. Sustainability-conscious designers employ strategies such as using high-performance insulation, designing energy-efficient lighting systems, and integrating diverse renewable energy sources to reduce energy consumption by as much as 30-40% compared to traditional buildings [12,13]. Especially in areas with high energy consumption, such as operating rooms, it is projected that energy efficiency strategies can provide savings of approximately $25,000 per operating room annually [14]. Considering that an average-size hospital has approximately 11 operating rooms, these savings add up to a significant saving at the institutional level.

The initial investment cost of green buildings is higher compared to traditional buildings, but green buildings provide significant savings in energy and operating expenses in the long run [15,16]. It is known that even healthcare facilities constructed in the 20th century were designed with natural ventilation and orientation towards the sun in mind [17,18]. However, in the 21st century, large-scale healthcare facilities incorporating multiple functions have been constructed in a manner that deviates from the passive designs of the past, leading to an increase in energy consumption per person. Therefore, there is a need for passive designs to increase efficiency in newly constructed healthcare facilities that house modern healthcare services [19,20]. Additionally, healthcare facilities should be reassessed to ensure the most suitable conditions for patients and healthcare personnel [21,22].

Healthcare facilities are actively used day or night, are different from other buildings due to their functional characteristics, and contain complex systems including operating rooms, x-ray/scanner rooms, patient rooms, and various sterile areas. Heating, cooling and ventilation systems in these areas consume considerable energy. Indeed, the energy cost of healthcare facilities amount to $8.5 billion per year, twice as much compared to office buildings [19].

Green practices are gaining importance in designing, constructing, and operating healthcare facilities worldwide thanks to green healthcare facilities’ economic and environmental advantages and innovative healthcare technologies. The effective functioning of these practices is possible through green certification systems [20,21,22].

The green building concept emerged in the 1990s and has gained importance with various improvements over the years and paved the way for the development of new standards for sustainable building designs [23]. Each green building certification system has a specific application process, registration fee, number of categories and criteria, and rating system. The relevant details are included in guidelines, regulations and web resources [24]. There are more than 80 green building certification systems implemented in different countries around the world [25]. The first major certification systems have been developed in advanced countries such as the U.S. (LEED), the U.K. (BREEAM), and Germany (DGNB) [25,26]. Green buildings reduce life cycle costs by approximately 28% compared to conventional buildings [27].

The effects of the COVID-19 pandemic, which showed its first symptoms in 2019, continue today, and digital diagnosis and treatments gained importance [28]. During the pandemic process, digital tools such as electronic health records, information management systems, and wearable technologies have enabled the use of more effective and faster treatment processes in hospitals [28]. Modern imaging and surgical systems that accelerate diagnosis and treatment are among the indispensable elements of green healthcare structures [28,29]. For example, sustainable radiology practices are being developed and integrated into green healthcare facilities. These practices minimize their environmental impact and increase their energy efficiency.

Kouka et al. [30] examined in their study some globally active green building certification systems including DGNB (Deutsches Guetsiegel Nachhaltiges Bauen, supported by the German government and the German Sustainable Building Council), HQE (Haute Qualité Environnementale, developed in France in 1996 with state support), ITACA (Innovazione e Trasparenza degli Appalti e la Compatibilità Ambientale, based on life cycle analysis in sustainable building practices in Italy), and SBTool (Sustainable Building Tool, developed in Germany as an internationally applicable green building certification tool) [30]. Kouka et al. [30] assessment has revealed that these green building certification systems vary greatly from each other and show differences in sustainability performance. In another study Yoon and Lim [31], examined the Green Mark certification system developed for conditions in Singapore and G-SEED (Green Standard for Energy and Environmental Design) developed for conditions in South Korea [31]. Based on their observations, Yoon and Lim [31] recommended that certification systems for healthcare facilities be designed based on the geographical and cultural values of the region, rather than directly adopting imported certification systems. In addition, Yoon and Lim [31] discussed the requirements for healthcare facilities and drew attention to the importance of patient safety and well-being.

While environmentally friendly building practices have long been adopted and standardized in advanced countries, developments in developing countries are more recent and diverse [32]. The rationale for comparing green certification systems for healthcare facilities in advanced and developing countries is to understand the similarities and differences between green certification systems for healthcare facilities in radically different socio-economic contexts [33].

When examining sustainable processes in the design and construction of healthcare facilities, it is observed that significant progress has been made in areas such as energy efficiency and waste management. For example, improvements made to the boiler room of a 600-bed hospital in Spain resulted in a 20.3-ton increase in oxygen production and a 23-ton reduction in CO₂ emissions thanks to energy-saving measures [34]. Also, the creation of advanced storage areas for the effective disposal of the large amount of waste generated in hospitals, the training of healthcare staff on waste management appears to be critical in sustainable healthcare facilities in India.

As stated by Li et al. [35], analyzing existing green building certification systems is important when developing new and functional systems. Although the number of such comparative studies has increased in recent years, studies based on comprehensive content analysis are still deficient. This situation clearly reveals the need for more research to improve existing systems, especially in the context of green healthcare facilities [35].

The objective of this research is to compare green certification systems for healthcare facilities in advanced and developing countries based on the categories, criteria, sub-criteria, and scoring schemes used in these systems. Green building standards are critical for reducing negative environmental impacts and improving user health, especially in buildings with high energy and resource consumption such as healthcare facilities [36,37]. Healthcare facilities undergo renovation cycles at frequent intervals as they are structures that are continuously used by staff and patients. Healthcare facilities cause greater environmental impacts and generate more waste than other buildings. Therefore, the design and construction of sustainable healthcare facilities is of great importance and deserves a detailed certification system that helps to minimize the environmental impacts of these facilities. Furthermore, establishing standardized methodologies by collecting measurable environmental performance data throughout the life cycle of these facilities can be a significant improvement in future practice. The data obtained would be indispensable for ensuring improved green awareness and more sustainable healthcare facilities [38].

Another aim of this study is to emphasize the critical importance of green healthcare facilities in the literature and to draw attention to the positive contributions of these facilities to human health, environmental sustainability, and economic development. The findings of the study are visualized through graphs and tables. In line with the literature, the necessity of green healthcare facilities and the value of certification systems have been emphasized. This study is expected to provide an analytical basis for understanding how regional differences shape the models and the strategies applicable to designing and constructing sustainable healthcare facilities. Another objective of the study is to contribute to the dissemination of sustainability principles in the healthcare industry and to provide a theoretical and methodological basis for future studies.

2. Materials and Method

The methodology used in the study is presented in four stages:

1. Academic publications, industry-specific reports, and national/international certification guidelines related to green buildings and healthcare facilities were researched and reviewed. The method was generally based on a comprehensive literature review, and searches were conducted through academic databases using keywords such as “green hospitals,” “sustainable healthcare facilities,” and “green building certification systems.”

2. Four certification systems that are in use in advanced countries (LEED in the U.S., BREEAM in the U.K., Green Star in Australia, and CASBEE in Japan) and four certification systems that are in use in developing countries (YeS-TR in Turkiye, IGBC in India, GBI in Malaysia, and GREENSHIP in Indonesia) were selected for use in this study. The reasons why these certifications systems were selected are presented in

Section 3. Quantitative and qualitative data were collected about these eight certification systems from their official guidelines and relevant scientific publications. This study provides an analytical basis for understanding how regional differences shape the models and strategies applicable for sustainable healthcare.

3. The categories, criteria, sub-criteria and scoring systems used in each certification system were analyzed. The similarities and differences in the eight certification systems developed around the world were evaluated, and the critical criteria for sustainable healthcare facilities were identified. The data about these critical criteria were collected from the eight certification systems and visualized with tables and graphs. The similarities and differences between the systems were compared based on the most common categories used in the systems, namely “Sustainable Land and Transportation” (SLT), “Water and Waste Management” (WWM), “Energy Efficiency” (EE), “Materials and Life Cycle Impact” (MLC), “Indoor Environmental Quality” (IEQ), “Project Management Process” (PMP) and “Innovation” (IN). It must be noted that certification systems developed under different socio-cultural and economic conditions in different countries often contain criteria that are unique to the location, making it difficult to compare these systems. CASBEE's scoring and graphic format, BREEAM's percentage calculations, GBI's lack of mandatory criteria in its specifications are cases in point [39,40,41]. Nevertheless, as stated by Li et al. [35], comparing and analyzing existing green building certification systems is an important approach for developing new and more functional systems. In addition, after a content analysis of the categories, criteria, and sub-criteria used in every certification system, the strengths and weaknesses of each certification system were identified and discussed in the light of the literature.

4. Based on the findings obtained after the comparisons, specific recommendations were made for not only healthcare facilities in developing countries but also for the widespread adoption of sustainable practices on a global scale. Recommendations were shared to increase investor awareness in this area and increase the number of green healthcare facilities.

3. Green Certification Systems for Healthcare Facilities

Green building certification systems offer various types of certificates that were developed specifically for the location and the function of a building, using the values of the country [24]. The World Green Building Council (WGBC), an umbrella coalition of more than 100 members, aims to encourage green investments across the world [42]. According to Wu [43], Out of the many certification systems in the world, LEED, BREEAM, Green Star, and CASBEE are ranked among the most important ones. Information about the eight green healthcare facility certification systems used in the study is presented in

Table 1 [43]. The selection of the four green certification systems available in advanced countries was motivated by the large number of citations that these systems received in the literature. The four advanced countries included in the study (USA, UK, Japan, and Australia) are represented by long years of institutional experience and internationally recognized certification systems. In contrast, developing countries such as Turkiye, India, Malaysia, and Indonesia were selected because they are turning towards green building practices with rapidly increasing urbanization rates that involve extensive health investments. Different priorities and approaches are adopted in these countries due to local socio-economic conditions, resource limitations, and legislative challenges [44].

LEED and BREEAM are widely used not only in the U.S. and the U.K., respectively, but also around the world [50,51]. LEED and BREEAM include different practical applications and are updated often to include improvements and technological advances. Indeed, looking at the previous versions of LEED and BREEAM, it is observed that the weights of the criteria have been changed over the years [50,51]. In addition, new prerequisites have been established in some categories. Each one of the eight certification systems has many unique sub-criteria.

As shown in

Table 2, comparing certification systems is not easy because each of the eight certification systems has many unique sub-criteria. While the maximum total score for seven certification systems ranges from 100 to 110, only CASBEE has a maximum total score calculated out of 5. While only the Green Star Healthcare certification system has six different assessment levels, BREEAM and CASBEE have five, and the other certification systems have only four.

The increase in healthcare costs after the COVID-19 pandemic has accelerated investments in healthcare facilities and the European Green Deal aimed to reduce greenhouse gas emissions by 55% by 2030 and eliminate negative environmental factors by 2050 [30]. In some countries, there are various requirements according to the size of the healthcare facilities. For example, in Turkiye, according to the regulations issued by the Ministry of Health in 2012, all hospital buildings with 200 beds or more must have a LEED Gold or Platinum Certificate [53].

It was seen in the literature review that although there are many comparative studies on green building certification systems, only few analyze these systems in detail, especially in the context of healthcare facilities. This deficiency points to an important gap about the critical role of sustainability in healthcare facilities even though healthcare facilities are quite different from other buildings because they provide uninterrupted service, have high user density and high energy demand. Green building certification systems need to have sustainability criteria that are specific to healthcare facilities. For example, due to the large size of the land they occupy and the large size of the buildings, healthcare facilities require a significant level of irrigation outdoors, while indoors, the use of water with predetermined temperatures for medical devices and sterilization processes is mandatory [25]. These findings reveal that designing and constructing green healthcare facilities provides not only environmental but also human benefits. Therefore, the certification systems used in the design and construction of green healthcare facilities should be evaluated in detail, the environmental impacts of healthcare facilities should be measured, the contribution of healthcare facilities to user health and to enhancing resource efficiency should be considered. In this study, eight leading green certification systems for healthcare facilities including LEED-Healthcare BD+C V4.1, BREEAM Healthcare V6.1, Green Star Healthcare Design and As Built v1.2, CASBEE Hospital 2014 Edition, YeS-TR V1, IGBC Healthcare V1.0, Greenship New Building V1.2, and GBI Hospital V1.0 are examined.

3.1. LEED-Healthcare BD+C V4.1

LEED was developed by the United States Green Building Council (USGBC) in 1993 for use in designing and constructing green buildings [50]. LEED is a non-profit organization with no U.S. government affiliation. The LEED Green Building Certification System is the most widely used certification system in the world. It has been used in numerous projects of different types. Considering the unique needs of healthcare facility projects compared to other building types, the USGBC has designed the “LEED-Healthcare” certification system to meet healthcare-specific requirements such as climate control tailored to the space with advanced equipment and 24/7 professional monitoring. As of September 2024, there were approximately 4,000 LEED-Healthcare certified projects worldwide [50]. LEED-Healthcare-certified medical campuses total 86 million square meters. The Healthcare version was first introduced in LEED v3 and was finalized in LEED v4 by increasing the number of certification categories and redesigning the scoring process to be performance-oriented rather than prescriptive. LEED-Healthcare covers details specific to healthcare systems such as smoke controls, cleaning strategies, and asbestos monitoring [54].

3.2. BREEAM-Healthcare V6.1

The full name of the certification system designed by the Building Research Establishment (BRE) in the U.K. is Building Research Establishment Environmental Assessment Methodology (BREEAM) [51]. The first green building certification system in the world was developed by BRE. More than 1 million buildings have been certified since its introduction in 1990 [51]. The BREEAM-Healthcare certification system was used in certifying over 1,000 healthcare buildings, starting in 2008. Updates were made in the following years, including on its scoring system [51]. BREEAM-Healthcare has specialized versions for specialist hospitals, general hospitals, mental health centers, operating rooms, and clinics [40].

3.3. Green Star - Healthcare Design and As Built v1.2

The Green Star certification system was developed by the Green Building Council Australia in 2003. With over 5,500 certified projects for all building types since then, Green Star has over 650 members and more than 26 million square meters of certified space [55]. The potential number of people served by the built areas certified by Green Star exceeds 800,000. Green Star certifies 20 different functions, including homes, plazas, educational buildings, offices, and healthcare facilities. In collaboration with academic researchers and government institutions, Green Building Council Australia also provides green building training courses to promote professional development in green design and construction. The Green Star - Healthcare Design and As Built v1 guide was first published in June 2009 [56]. Cardno, a global infrastructure services company that operates in the 6-Star Green Star certified Green Square Tower North in Brisbane, Australia was relocated from a 4,500 m² office to a larger 7,800 m² space resulting in a reduction of monthly energy costs from approximately $12,000 to $8,000. This case illustrates that green building practices yield not only environmental benefits but also substantial economic advantages [56].

3.4. CASBEE-Hospital 2014 Edition

CASBEE was first introduced in 2001 with the support of the Japan Sustainable Building Consortium (JSBC) and provides sustainability advice through nine different checklists and more than 20 tools [41]. Developed in response to frequent natural disasters in Japan, the system is designed to provide solutions against potential threats [41]. As seen in

Table 2, while a scoring scheme of 100-110 is used in other certification systems, a 5-point system is used in CASBEE. CASBEE’s scoring process is not as straightforward and clear as in other certification systems. So, Kotesli [58], had to convert this 5-point scoring system to a 100-point scoring system to be able to compare CASBEE with other certificate systems [58].

3.5. YeS-TR V1

YeS-TR was developed by the Ministry of Environment, Urbanization and Climate Change of Turkiye (MEUCC), not by voluntary non-government institutions like in other countries. YeS-TR stands for “Yesil Sertifika (Green Certificate) – Turkiye” [59]. The Turkish Ministry of Environment, Urbanization and Climate Change announced that the YeS-TR certificate will be mandatory after 2026 for public building projects with a surface area exceeding 10,000 m². There are currently no healthcare facilities in Turkiye with YeS-TR certification, and it is expected that newly constructed healthcare facilities will be certified by YeS-TR [59].

3.6. IGBC-Healthcare V1.0

The Indian Green Building Council (IGBC) was established by the Confederation of Indian Industry in 2001 [60]. Since then, IGBC has certified over 5,800 construction projects in India. These projects include numerous healthcare facilities, including healthcare centers, clinics, and hospitals [60]. Green healthcare strategies were defined by IGBC, and a certification guide was created by a committee composed of architects, engineers, and healthcare professionals. Environmentally friendly actions were recommended during the design and construction processes. Special emphasis was placed on the extensive use of copper, because copper reduces the amount of pollutants in relaxation areas near windows and landscaping elements, and because copper-containing products hold fewer microbes. Recycled material preferences, automatic solid waste management systems, and pollution management are also included in the IGBC certification criteria [47,60].

3.7. GREENSHIP New Building V1.2

The GREENSHIP certification system was established by Green Building Council Indonesia (GBCI), a non-profit civil society organization. GREENSHIP is a long-standing member of the World Green Building Council and is the largest recognized green building certification program in Indonesia. The certification aims to raise awareness in the community about sustainability by enabling green transformations in the construction sector.

Furthermore, cooperation is pursued with real estate developers, expert engineers, professional associations, and official institutions to increase the use of the GREENSHIP certification system [48]. GREENSHIP has provisions for healthcare buildings, but there is no specific version for healthcare facilities [62].

3.8. GBI-Hospital V1.0

The Green Building Index (GBI), Malaysia's first comprehensive green building certification system, was developed by the Malaysian Institute of Architects and the Malaysian Association of Consulting Engineers based on Australia's Green Star Certification System to promote sustainable development. The certification criteria were designed for Malaysia's tropical climate, and for cultural and social needs in mind [49]. There are 753 certified buildings in Malaysia, 469 of which are located in Kuala Lumpur and Selangor states [63]. The certification system that was specifically designed for hospitals was developed in collaboration with the Malaysian Ministry of Health and Health Technical Services [52,63].

According to the information in

Table 3, energy use and efficiency is a priority category in many green healthcare facility certification systems. The percentages cited in the next and succeeding sentences refer to the categories’ shares in the scoring system. LEED (39%), GBI (35%), YeS-TR (27%), IGBC (23%), and GREENSHIP (25%) have high weights allocated to energy use and efficiency. Water management and efficiency is another important category that stands out especially in IGBC (29%), GREENSHIP (26%) and YeS-TR (19%) certifications. Indoor environmental quality and patient health criteria are also critical in many certification systems, with BREEAM (14%), Green Star (18%), GBI (21%) and IGBC (23%) at the top of the list. On the other hand, the categories innovation and sustainable building are considered in many certification systems but are generally assessed with a weight between 5-10%. In conclusion, the differences between certification systems vary according to the environmental priorities and sustainability policies of the countries in question. This finding makes sense because the conditions in each country are different and so are the emphases on each category. For example, it is not surprising that the energy use and efficiency category enjoys a high priority in Turkiye where natural oil reserves are extremely limited.

4. Results and Discussion

In general, although some categories listed in

Table 3 differ from one certification system to another, the categories represent similar interests. However, it must be noted that sometimes similar criteria are used in different categories. For example, in GREEN STAR and GBI, the “rainwater harvesting” criterion is included in the “water efficiency” category, while in LEED, the “rainwater storage” criterion is included in the “sustainable sites” category. Nevertheless, a comparison of the eight certification systems showed that most of the categories in almost every certification system involve “energy”, “water”, “indoor environmental quality”, “materials”, “waste”, “transport”, and “sustainable land selection”. Finally, the most evaluated categories were: “Sustainable Land and Transportation” (SLT), “Water and Waste Management” (WWM), “Energy Efficiency” (EE), “Materials and Life Cycle Impact” (MLC), “Indoor Environmental Quality” (IEQ), “Project Management Process” (PMP) and “Innovation” (IN). The “project management process” and the “innovation” categories are usually presented as an additional category in some certification systems. The comparisons are shown in

Table 4,

Table 5,

Table 6,

Table 7,

Table 8,

Table 9 and

Table 10.

LEED and BREEAM are available in many countries worldwide for rating buildings, including healthcare facilities [39,40]. Except for CASBEE, the other seven certification systems have some mandatory prerequisites, as shown in

Table 4,

Table 5,

Table 6,

Table 7,

Table 8,

Table 9 and

Table 10. Prerequisites are environmentally friendly requirements that contribute to sustainability efforts but do not have a direct impact on the rating score.

4.1. Sustainable Land and Transport

The “Sustainable Land and Transport” category encompasses strategies for identifying the appropriate project site, sustainable planning of transport alternatives, and ecosystem protection to minimize the environmental impacts of healthcare facilities [64,65]. This category has a broad perspective ranging from accessibility, functional use of land, heat island and climate impacts, public transport facilities, cycling infrastructure, to green vehicle practices. As seen in

Table 4, in this category, different approaches are adopted in different certification systems.

In the LEED system, actions taken to prevent environmental pollution from construction processes and optimize site layout are in line with sustainable development models. Green Star prioritizes the protection of endangered species, allowing biodiversity to be integrated with sustainable urbanism practices [66].

From the perspective of developing countries, IGBC's emphasis on local building codes and safety compliance shows the importance of integrating the regional regulatory framework into the certification criteria [67]. The fact that GREENSHIP requires a core green space module points out to the critical role of green spaces in urban planning processes [68].

Moreover, the emphasis that the GBI certification system places on green roof applications is in line with global trends towards the mainstreaming of green infrastructure solutions at the building scale [69]. With the exception of YeS-TR, all other certification systems have sub-criteria for the sustainable land and transport category. LEED emphasizes direct outdoor access and recreational areas, while BREEAM focuses on ecological maintenance and repairs. CASBEE's criteria for landscape and biotope conservation reflect an understanding parallel to sustainable urbanism approaches [70]. GREENSHIP's requirement to collect green building data through building user surveys is conducive to improve user experience [71].

Ultimately, systems such as LEED and BREEAM focus on transport infrastructure, while CASBEE and GREENSHIP include broader ecological sustainability measures. YeS-TR and GBI place more emphasis on country-specific requirements such as compliance with local building codes and site management. These differences are shaped by countries' climate policies and sustainability priorities. A more comprehensive implementation of sustainable land and transport practices in developing countries may reduce the environmental impacts of healthcare facilities in these countries.

The “Sustainable Land and Transportation” category encompasses general sustainability criteria that focus on core values such as green vehicles, bicycle parking areas, quality public transportation access, and heat island reduction. When these criteria, typically seen in most green building certification systems, are evaluated in the context of healthcare facilities, they have been found to be deficient in covering critical healthcare facility-specific issues such as uninterrupted access for emergency vehicles and special access for disabled patients

4.2. Water and Waste Management

Effective use of water and reducing environmental pollution are the main objectives in the “Water and Pollution Management” category. Water saving and efficient water management are the common criteria in all green building certification systems [72,73]. A comparative overview of the eight green healthcare facility certification systems with respect to the “Water and Waste Management” category is presented in

Table 5.

The existence of prerequisites for monitoring and measuring water consumption in LEED, GREENSHIP, YeS-TR, and IGBC indicates that these certification systems adopt a holistic and data-based approach. However, IGBC's requirement for rainwater storage and water-saving faucets demonstrates that this system takes a stricter and clearer stance on the conservation of water resources [60]. This situation shows the importance of using different criteria based on local conditions especially in water-scarce countries such as India where the environmental conditions are radically different than the conditions in advanced countries and where sustainability goals should address the local conditions [74]. On the other hand, the fact that BREEAM and GREEN STAR include comprehensive criteria for pollution management and that these criteria are diversified in different dimensions such as light, noise, and microbial control shows that a more detailed and comprehensive environmental understanding is adopted in these systems.

The fact that drinking water consumption is addressed with microbial control criteria in GREEN STAR makes a significant contribution to the protection of public health [55]. Similarly, the fact that BREEAM addresses environmental issues such as noise pollution and surface water runoff in detail reflects the rigor and environmental sensitivity of European-based certificate systems [40]. In conclusion, although the general objectives related to water consumption and pollution management are similar in the eight certification systems, differences in implementation are noteworthy. In addition to the stricter practices of IGBC, the global adoption of BREEAM and GREEN STAR's comprehensive approaches to environmental pollution is important in terms of increasing awareness of sustainability. CASBEE, on the other hand, offers a different certification approach by linking resource management and water use.

The criteria in the “water and waste management” category effectively promote values such as pollution control and water supply efficiency. The criteria mentioned are seen not only in green healthcare facilities but also in other green buildings. This situation may be inadequate for healthcare facility designers and operators. Among the key findings, water treatment systems specific to the many pathogens found in hospital environments, clinical risk management systems, and infection control are among the criteria that will enable fundamental improvements in healthcare facilities across all green certification systems.

4.3. Energy Efficiency

Energy management is at the center of sustainability strategies and is addressed in detail in all green building certification systems. The “energy efficiency” category generally involves renewable energy use, reduction of greenhouse gas emissions, refrigerant management, and the commissioning processes [75]. For a comparison of the systems, see

Table 6. In YeS-TR, energy systems are designed based on the national "Regulation on Energy Performance in Buildings" and reflects local conditions [46]. YeS-TR provides a more specific structure compared to the other certification systems, enabling better evaluation. LEED is designed to evaluate energy management by measuring the degree of adherence to five basic requirements: optimizing energy performance, measuring energy consumption, managing refrigerants, basic commissioning, and verification processes [76]. These requirements aim to ensure that energy consumption is systematically measured and effectively managed so that the performance of sustainable buildings remains consistently high.

The fact that YeS-TR does not emphasize commissioning processes can be considered as a deficiency compared to the other certification systems even though according to Kubba [72], advanced commissioning processes are critical elements that guarantee the long-term performance and sustainability of building energy systems. The criteria of “using renewable energy sources”, “increasing energy efficiency”, and “reducing greenhouse gas emissions”, which are common to all green building certification systems, constitute the cornerstones of global sustainability goals. In sum, all certification systems reflect universal standards and offer a common perspective in the fight against global climate change. LEED's and GREEN STAR’s detailed criteria for refrigerant management are important in protecting the ozone layer and preventing global warming [55].

Advanced commissioning systems are indispensable for continuous monitoring and improvement of energy consumption. It is frequently emphasized in the literature that these systems should be included in all certification systems [77]. In general, LEED, BREEAM, and Green Star focus on engineering solutions for energy efficiency and reduction of carbon emissions, while certificate systems such as CASBEE, YeS-TR, IGBC, and GREENSHIP attach more importance to building design, natural resource utilization, and renewable energy integration. GBI aims to optimize energy consumption with an emphasis on energy metering and building management systems.

The “Energy Efficiency” category demonstrates the most mature alignment with green building standards, while also focusing on renewable energy sources, emissions, and commissioning, making it similar to general green buildings. For designers, this approach is satisfactory only in terms of reducing overall consumption, but it has been found to be insufficient in meeting indisputable needs such as uninterruptible power supply, redundancy for emergencies, and energy resilience during disasters.

4.4. Materials and Resources

“Materials and Resources” is one of the basic categories in green building certification systems. It involves the recovery and reuse of materials and aims to reduce the environmental impact of the building construction industry. Although the “Materials and Resources” category is shaped around common objectives in different green building certification systems, the criteria developed for this category have significant differences [72]. A comparison of the eight green certification systems for healthcare facilities with respect to the “Materials and Resources” category is presented in

Table 7.

LEED sets stricter prerequisites in waste management compared to the other certification systems and includes detailed procedures such as separation of recyclable waste and waste control in construction/demolition processes [76]. YeS-TR has strong criteria for the use of sustainable materials even though these criteria are not as strict as the LEED prerequisites [46].

IGBC encourages particularly the selection of certified wood and prefabricated materials to ensure efficiency in material use and reduced waste [47]. In addition, the LEED criteria for the reduction of toxic substances such as lead, mercury, and cadmium directly support user health [72]. The fact that BREEAM encourages the use of recycled aggregates contributes to resource efficiency by supporting the reuse of waste, especially in urban transformation and infrastructure projects [40]. GREENSHIP's criteria, which emphasize certified wood are vital for the conservation of tropical forests and the protection of biodiversity and aim to reduce the environmental impact of the selected materials [48].

In general, LEED, BREEAM and Green Star focus on the use of sustainable materials in construction processes and waste management, while in CASBEE, YeS-TR and GREENSHIP, more weight is assigned to criteria with low environmental impact, recyclable systems, and increased use of local resources. Attention to ecological product certifications and the use of environmentally friendly materials are encouraged in GBI and IGBC. These differences are shaped by the sustainability priorities and regional building policies in each country.

The “Materials and Resources” category for healthcare facilities is similar to the same category for general green buildings. The lack of criteria specific to healthcare facilities indicate that it needs improvements and additions to fully meet the expectations of healthcare facility investors. The findings in this category highlight the need for a tailor-made green certification system that firmly places healthcare-specific life cycle issues at the center of the “Material and Resources” category, from the supply of durable, cleanable surfaces to the safe disposal of medical waste.

4.5. Indoor Environmental Quality

The ‘Indoor Environmental Quality’ category directly affects the health and comfort of building users and is addressed by various criteria in different certification systems. It is shaped by criteria such as thermal comfort, acoustic performance, indoor air quality, daylight, and tobacco smoke control that are directly related to human health [78]. Information about the eight green certification systems for healthcare facilities with respect to the “Indoor Environmental Quality” category is presented in

Table 8.

The inclusion of tobacco smoke control as a prerequisite in the LEED and IGBC systems points out a strong emphasis on the protection of user health and shows commitment to ensuring clean air quality [47,76]. On the other hand, GBI includes criteria such as mold prevention, the use of high-frequency ballast, occupancy comfort surveys, i.e., innovative practices that can maximize the health and indoor comfort of building users [49]. The IGBC system is patient-oriented and differs from the other systems on its emphasis on healing gardens, color psychology, and spatial design criteria, especially designed for patients [47]. It creates healing environments in healthcare facilities, accelerates the recovery time of patients, and increases patient satisfaction. YeS-TR, on the other hand, has an approach that includes only basic criteria including indoor air quality, daylight, and thermal comfort relative to local conditions [46]. The fact that YeS-TR does not include additional criteria suggests that there is potential for improvement in Yes-TR and possibly other certification systems currently used in developing countries.

While LEED, BREEAM, and Green Star offer technical criteria to assess air quality, lighting, and thermal comfort, IGBC and GREENSHIP pursue psychological and ergonomic design solutions that support patient health. YeS-TR and GBI focus on measurable criteria including efficiency of air exchange, management of fresh air intake, and design for acoustic comfort. All systems aim to support patient recovery processes by improving the indoor environmental quality in healthcare facilities, to improve patient recovery times, and to enable healthcare professionals to work in an environment that can improve their performance. The information in this sub-section indicates that the criteria used to assess “indoor environmental quality” in green certification systems for healthcare facilities should include not only quantitative but also qualitative criteria.

While systems such as LEED and GBI provide a solid framework for indoor environmental quality in terms of air quality and thermal comfort, these criteria largely serve as a sophisticated patch applied to an office building model rather than a system specifically designed for patient outcomes. Criteria should also include clinical design considerations that reduce patient stress and lower infection rates. For example, principles such as specific acoustic levels for patient rest or access to nature for psychological healing are only partially accepted by IGBC. Therefore, the contents of current green certification systems convincingly demonstrate the need for independent green certification systems where the “Indoor Environmental Quality” criteria are developed uniquely around clinical evidence and patient recovery metrics, not just user comfort.

4.6. Project Management Process

The “Project Management Process” category is defined by a wide range of criteria including ensuring environmental sustainability throughout the project, including integrated design, planning, commissioning, operating, and maintenance processes [72]. The absence of criteria or prerequisites directly addressing the project management process in the GBI, IGBC, and GREENSHIP systems reveals that these systems focus on technical elements such as energy, materials, or indoor air quality rather than project management. However, the “integrated planning” prerequisite in LEED aims to ensure the coordination of project stakeholders in the design and construction processes and plays a key role in achieving sustainability goals [76]. In addition, Green Star includes criteria such as environmental performance targets, use of accredited personnel, and environmental management processes, indicating that comprehensive management and monitoring processes are in place [55]. In BREEAM, it is important that commissioning processes, maintenance, and construction practices are specifically included, emphasizing that the project management process is important not only in the design and construction phases but also in the operation phase, thus ensuring a building performance that is sustainable throughout a healthcare facility’s life cycle [40]. The emphasis on service, function, durability, reliability, and adaptability criteria in CASBEE shows that it is aimed to increase structural resilience against natural disasters and climate crises that Japan frequently experiences [57]. In particular, criteria that address project teams, project scope, stakeholder engagement, and occupational health and safety practices have the potential to improve sustainability performance in the construction industry in Turkiye [46]. Unlike the other certification systems, YeS-TR has a detailed and localized approach to project management. Information about the eight green certification systems for healthcare facilities with respect to the “Indoor Environmental Quality” category is presented in

Table 9.

The eight green certification systems for healthcare facilities involve different approaches in to the “Project Management Process” category. LEED and Green Star's criteria for process management and environmental performance, BREEAM's coverage of commissioning and maintenance, CASBEE's focus on resilience and adaptation, and YeS-TR's prioritization of project scope and stakeholder engagement offer complementary perspectives for effectively managing the entire life cycle of sustainable healthcare facilities. GBI, IGBC and GREENSHIP certificates do not have a category directly related to the project management but include some guidance on sustainable building management.

The findings in the "Project Management Process" category reveal the most profound disconnect between generic certification frameworks and the complex reality of delivering a healthcare facility. The absence of this category in systems like GBI, IGBC, and GREENSHIP is not a minor omission but a fundamental flaw, reducing sustainability to a set of technical checkboxes rather than an integrated, managed outcome. For project managers and designers, this gap is entirely unsatisfactory, as it fails to mandate the rigorous, cross-disciplinary coordination, clinical equipment integration, and operational risk management that are critical to a successful hospital project. While the integrated planning in LEED and the operational focus in BREEAM are valuable patches, they remain additions to a system not designed for healthcare's procurement and commissioning complexity. The comprehensive and localized approach of YeS-TR stands as the exception that proves the rule. Therefore, the widespread neglect or underdevelopment of healthcare-specific project management protocols in most systems is unacceptable.

4.7. Innovation

The “Innovation” category stands out as an important category that supports technological and managerial improvements to achieve sustainability goals. This category has a privileged place in green certification systems for healthcare facilities as it encourages designers, constructors, and facility managers to think about and implement out-of-the-box solutions to sustainability related issues in healthcare facility design and construction [72].

The “Innovation” category in LEED and IGBC shows that innovative solutions are encouraged through an audit mechanism that requires the input of accredited experts [47,76]. In contrast, GREENSHIP's criteria emphasize the economic and technological dimensions of innovation by covering technological breakthroughs, market improvements, and global sustainability trends [48]. On the other hand, in systems such as IGBC, LEED, and BREEAM, innovation is treated as a bonus or additional point category without any prerequisites, encouraging project owners to produce innovative and original solutions, hence providing creativity and flexibility in building design and construction [40,76]. In this sense, YeS-TR's special emphasis on innovation is valuable in terms of promoting the understanding of environmentally friendly and innovative design and construction methods in the Turkish building construction industry [46]. Information about the “Innovation” category is presented in

Table 10.

The innovation category highlights the most significant gaps in meeting the dynamic needs of healthcare facilities. In the eight green certification systems examined, innovation has been addressed as an integrated element of sustainability standards, such as in LEED, BREEAM, and Green Star; as a life cycle emphasis in YeS-TR and GBI; or as part of green design processes in IGBC. Regardless however, innovation has been treated as either an optional “extra” like deserving bonus points or within a narrow framework. Indeed, “Innovation” does not even exist as a direct category in CASBEE and GREENSHIP. This fragmentation lacks concrete guidance that would tangibly direct a healthcare facility designer to develop vital and original solutions, such as modular systems that can be deployed in crises like a pandemic or technologies that directly support patient recovery. Although the explicit and implicit approaches in current systems emphasize the importance of innovation, they fall short of reflecting a holistic, healthcare facility-focused understanding of innovation. Minor modifications in existing systems are insufficient, and the future of sustainable healthcare structures will be shaped by the development of an independent certification system centered on innovation that is specific to healthcare facilities.

4.8. Comparison of the Criteria Used in Green Certification Systems for Healthcare Facilities

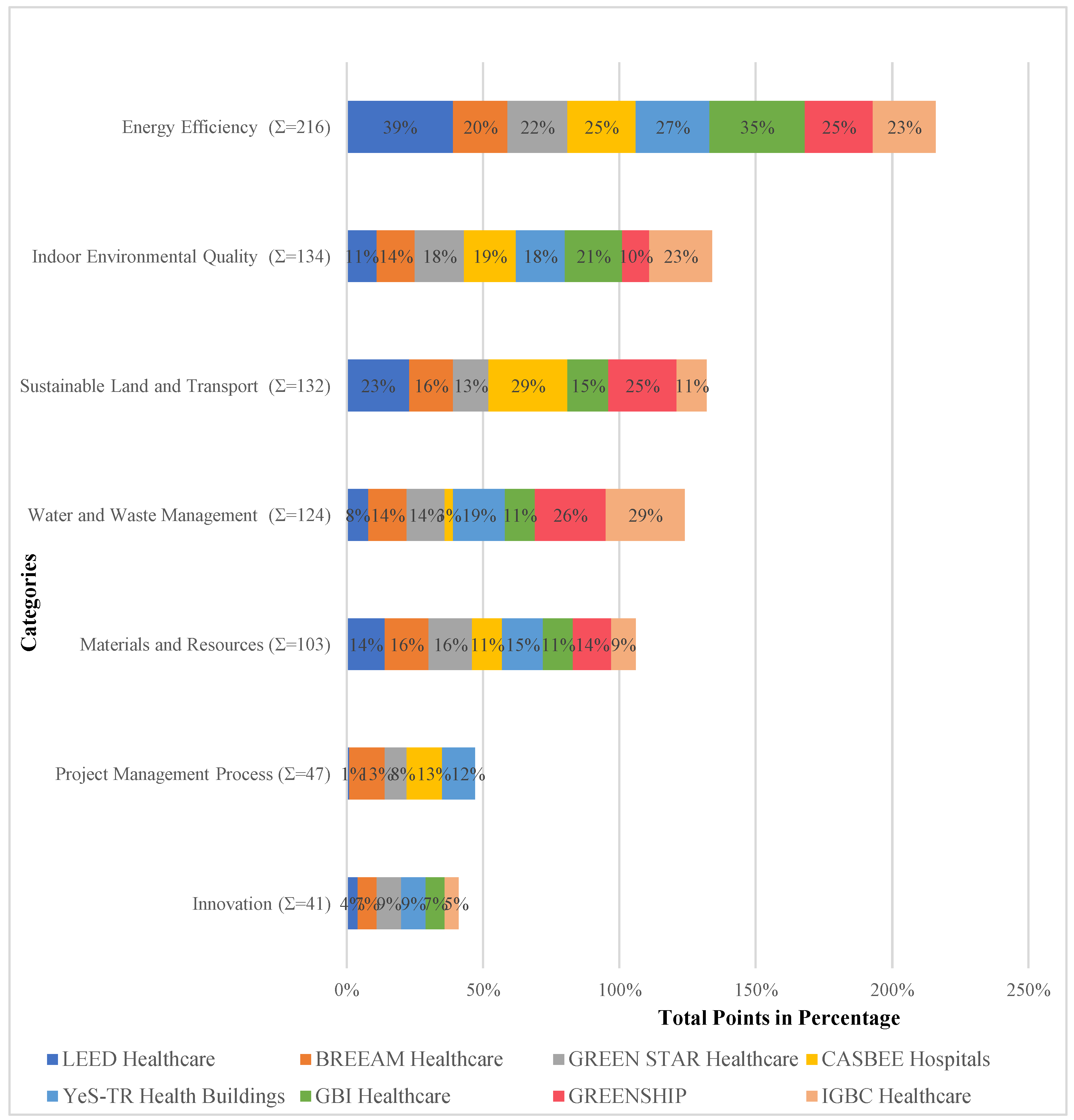

In this study, eight green certification systems for healthcare facilities were selected from those available in advanced and developing countries, were examined in detail and compared in terms of sustainability criteria. The total weights of the following categories were derived from the information presented in

Table 3 and are presented in Chart1: “Sustainable Land and Transport”, “Water and Waste Management”, “Energy Efficiency”, “Material and Life Cycle Impact”, “Indoor Environmental Quality”, “Project Management Process”, and “Innovation”. The weights of the categories add up to 100% for each certification system. Each of the eight certification systems displays different priorities to reduce the environmental impact of healthcare facilities. The main purpose of the study is to provide a guiding framework for the design and construction of complex healthcare facilities with green consciousness and to reveal the differences of the existing green certification systems augmented to handle healthcare facilities.

Chart 1.

Percentage distribution of certification system categories.

Chart 1.

Percentage distribution of certification system categories.

The category with the highest joint weight is “Energy Efficiency” (Σ=216), which is far ahead of the other categories. Systems such as LEED (39%) and GBI (35%) aim to reduce the high energy consumption of hospitals with sustainable methods by assigning a large weight to this area. In addition, systems such as YeS-TR (27%), GREENSHIP (25%) and CASBEE (25%) also prioritize energy management. This reveals that energy consumption is a critical factor in terms of sustainability in healthcare buildings [75,76].

The category with the second highest joint weight is “Indoor Environmental Quality” (Σ=134) with IGBC (23%), GBI (21%) and CASBEE (19%) standing out. In these certification systems, criteria such as indoor air quality, daylight, acoustic comfort, and psychological healing environments play an important role [78]. In LEED (11%) and GREENSHIP (10%), the importance of this category lags behind the other certification systems.

The category with the third highest joint weight is “Sustainable Land and Transport” (Σ=132). It is particularly prominent in CASBEE (29%), GREENSHIP (25%) and LEED Healthcare (23%). In this category, factors such as public transportation facilities, access to green space and climate adaptation are prioritized [64]. This finding shows that healthcare facilities should be considered not only in-building but also in-city integration as a part of sustainability.

The category with the fourth highest joint weight is “Water and Waste Management” (Σ=124) with IGBC (29%) and GREENSHIP (26%) standing out, while CASBEE (3%), LEED (8%) and GBI (11%) give very limited importance to this category. The fact that IGBC applies stricter criteria for water management in a water-stressed country such as India with a value of 29% shows how sustainability priorities based on geographical conditions are reflected in certifications [74].

The category with the fifth highest joint weight “Material and Life Cycle Impact” (Σ=103) includes GREEN STAR (16%), BREEAM (16%), LEED (14%), and CASBEE (11%) at the top of the list. In other words, the four certification systems in advanced countries have the highest collective weight (Σ=57), while the collective weight of the four certification systems in developing countries is only slightly less (Σ=49) with YeS-TR (15%), GREENSHIP (14%), GBI (11%), and IGBC (9%). The fact that such a similarity is observed reveals that the quality of the materials selected to construct healthcare facilities is of almost equal importance regardless of location and regardless of the certification system used.

The category with the sixth highest joint weight “Project Management Process” (Σ=47) is one of the least weighted categories as it is somewhat represented in all certifications systems available in advanced countries but not represented at all in certification systems available in developing countries, except for YeS-TR (12%). The fact that YeS-TR addresses the project process with detailed criteria such as occupational health and safety, stakeholder engagement, and integrated management reveals that YeS-TR is more closely aligned with well-established and popular certification systems available in advanced counties.

The least weighted category across the eight certification systems is “Innovation” (Σ=41). It is barely represented in Green Star (9%), YeS-TR (9%), BREEAM (7%), GBI (7%), IGBC (5%) and LEED (4%). It is only indirectly represented in other criteria (CASBEE and GREENSHIP). However, “innovation” is critical for potentially increased efficiency in healthcare facilities through digital technologies and smart building systems.

5. Conclusions

In this study, eight green certification systems for healthcare facilities were analyzed and compared relative to seven fundamental categories. Half of these certification systems are extensively used in advanced countries and worldwide, and the other half originated in developing countries and are used rather locally. The findings revealed that the majority of the green certification systems used for healthcare facilities are adaptations of general-purpose green building certification systems. Consequently, the essential requirements of healthcare facilities, such as hygiene, infection control, medical waste management, and patient and staff safety, which are critical to healthcare systems, are not sufficiently emphasized in any of the eight certification systems reviewed in the study. Furthermore, shortcomings in areas such as disaster resilience, digitization, and operational process management highlight the need to broaden the scope of these systems. In other words, there is an urgent need to develop specialized green certification systems that focus on the unique complexity of healthcare services, centered not only on environmental but also medical, social and operational sustainability. The findings of this study are expected to encourage the development of green certification systems specifically designed for healthcare facilities in the future and to serve as a guide for building more resilient, efficient, and patient-centered healthcare infrastructures.

Considering the findings, green certification systems for healthcare facilities vary according to countries' level of development, sustainability priorities, level of access to resources, and healthcare needs. For example, while LEED, BREEAM and Green Star systems stand out with carbon emission reductions and highly engineered solutions, GREENSHIP, IGBC and YeS-TR focus more on local resource management and water efficiency.

Green healthcare facilities can consist of multiple buildings, such as hospitals, laboratories, diagnostic services, and treatment centers and represent large and complex projects. As such, green certification systems for healthcare facilities should focus more on digitization and project management processes in the future. The green healthcare facilities of the future should be equipped with smart systems, have reduced environmental impacts, and achieve maximum patient comfort. Such a development will not only contribute to global climate goals but also improve the quality of healthcare services and lead to more resilient and efficient healthcare facilities.

The multifaceted benefits of green healthcare facilities, such as operational efficiency, patient well-being, and minimal environmental impact, underscore the strategic importance of this study. The observed differences in priorities, such as the emphasis on water and waste management in IGBC and GREENSHIP versus the focus on energy performance in LEED and CASBEE, provide stakeholders with valuable insights that encourage users of green certification systems to accommodate specific regional contexts and resource constraints. In addition, it has been observed that issues such as disaster management, earthquake and climate risks are not sufficiently detailed in green certification systems except for only CASBEE that includes criteria such as durability and reliability. Green certification systems for healthcare facilities should be supported with more comprehensive resilience criteria.

Tables 4 to 10 show that there are not enough criteria or prerequisites that pertain to the operation of green healthcare systems, except for YeS-TR. A certification system for healthcare facilities should include a holistic approach that prioritizes patient and healthcare personnel safety/comfort in addition to energy savings and environmentally friendly designs. Instead of focusing only on building performance in healthcare facilities, architectural solutions that consider entrance-exit areas, emergency service integration, and patient flow should be adopted. Healthcare facility users’ feedback is important for integrating user experience into the green certification process.

One of the recommendations developed in this study is to include practices related not only to the design and construction process of green healthcare facilities, but also to the management, monitoring, and maintenance processes in the operation phase, as in Green Star and BREEAM. The detailed criteria that YeS-TR brings to the project management process is a good example of considering the local conditions in a country.

The information presented in

Table 4,

Table 5,

Table 6,

Table 7,

Table 8,

Table 9 and

Table 10 indicates that existing green certification systems that have been modified to include healthcare facilities constitute a very good first step to developing more healthcare facility-focused certification systems. The general criteria in the “Land and Transportation” and “Materials and Resources” categories are augmented only by a patchwork of weak requirements in designing and building healthcare facilities. Although the “Energy Efficiency” and “Water Management” criteria are based on a mature infrastructure, the critical issues related to healthcare facilities such as energy resilience and hospital-acquired pathogen control are overlooked. “Indoor Environmental Quality” covers the usual requirements for green buildings but has not evolved into a category that makes use of clinical evidence for patient recovery in the design and construction of healthcare facilities. The deepest disconnect is seen in the “Project Management Process” category as most certification systems ignore this process, reducing sustainability to a technical checklist. The superficiality in the “Innovation” category does not sufficiently meet the dynamic future needs of healthcare facilities. Based on the information acquired in this study, it is argued that the future of sustainable healthcare facilities will be shaped by the development of green certification systems that are specifically oriented to the design, construction, and operation of healthcare facilities, centered on clinical evidence, operational continuity, patient outcomes, and technical/managerial innovation.

This study provides a critical roadmap for designing and constructing healthcare facilities with prioritized environmental, social, and operational sustainability. It is anticipated that this work will significantly raise sustainability awareness within the healthcare sector, promote the adoption of green healthcare concepts globally, and stimulate further research.

In designing green healthcare facilities, it is important to be prepared for managing crises or pandemics by addressing issues such as the optimization of emergency service transportation and the planning of disaster-resilient buildings. To improve resource efficiency, separating critical and non-critical loads to monitor waste management and implementing steps such as monitoring water consumption per patient will be important gains. The recycling of single-use medical supplies, barrier-free access areas, accommodation options tailored to companions, a sustainability council established by hospital administrators and staff, and soundscape designs composed of natural sounds to improve the patient's psychological state are also among the criteria that can be added.

This study's focus on eight certification systems, while representative of practices in advanced and developing countries, presents a limitation in capturing all regional nuances. Furthermore, the analysis is based on documentary criteria rather than empirical performance data collected from professionals who participated in the design and construction of certified healthcare facilities. To address these constraints, future research should expand the scope to include a larger number of green certification systems for healthcare facilities and to explore the differential impacts of these systems across varied geographic zones, building functions, and operational lifetimes. Longitudinal studies could also be performed to quantitatively assess the real-world outcomes of existing green certification systems. Investigating the influence of specific variables such as climate zone and number of patient rooms would further refine the development of context-sensitive green certification systems for healthcare facilities.

Author Contributions

Conceptualization, R.A.B.; methodology, R.A.B. and R.K.; validation, R.A.B. and D.A.; formal analysis, R.A.B. and R.K.; investigation, R.A.B. and R.K.; resources, R.A.B. and R.K.; data curation, R.A.B. and D.A.; writing—original draft preparation, R.A.B. and D.A.; writing—review and editing, R.K.; supervision, D.A.; project administration, R.A.B All authors have read and agreed to the published version of the manuscript.

Funding

This research received no external funding.

Institutional Review Board Statement

Not applicable.

Informed Consent Statement

Not applicable.

Data Availability Statement

The data used to support the findings of this study are available from the corresponding author upon request.

AI Usage Statement

During the preparation of this article, the authors utilized artificial intelligence resources for language editing and assume full responsibility for the content after reviewing it.

Conflicts of Interest

The authors declare no conflicts of interest.

References

- International Energy Agency (IEA). Buildings – Energy System. Available online: https://www.iea.org/energy-system/buildings (accessed on 23 December 2024).

- Allen, J.G.; MacNaughton, P.; Satish, U.; Santanam, S.; Vallarino, J.; Spengler, J.D. Associations of Cognitive Function Scores with Carbon Dioxide, Ventilation, and Volatile Organic Compound Exposures in Office Workers: A Controlled Exposure Study of Green and Conventional Office Environments. Environ. Health Perspect. 2016, 124, 805–812. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Sartori, T.; Drogemuller, R.; Omrani, S.; Lamari, F. A Schematic Framework for Life Cycle Assessment (LCA) and Green Building Rating System (GBRS). J. Build. Eng. 2021, 38, 102180. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Ferrari, S.; Zoghi, M.; Blázquez, T.; Dall’O, G. New Level(s) Framework: Assessing the Affinity between the Main International Green Building Rating Systems and the European Scheme. Renew. Sustain. Energy Rev. 2021, 155, 111924. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Bertiz, D.; Eksi, I.; Tokmak, M.; Ozbey, D. Comparison of International and National Green Building Certification Systems in Terms of Green Infrastructure. Peyzaj-Eğitim, Bilim, Kültür ve Sanat Dergisi 2019, 1, 31–39. [Google Scholar]

- Gil-Ozoudeh, I.; Iwuanyanwu, O.; Okwandu, A.C.; Ike, C.S. The Impact of Green Building Certifications on Market Value and Occupant Satisfaction. Int. J. Mod. Eng. Res. 2024, 6, 45–58. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Chen, L.; Hu, Y.; Wang, R.; Zhang, Y.; Liu, X. Green Building Practices to Integrate Renewable Energy in the Construction Sector: A Review. Environ. Chem. Lett. 2024, 22, 751–784. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Mazur, L.; Resler, M.; Koda, E.; Walasek, D.; Vaverková, M.D. Energy Saving and Green Building Certification: Case Study of Commercial Buildings in Warsaw, Poland. Sustain. Energy Technol. Assess. 2023, 60, 103520. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Cilhoroz, Y.; Isik, O. Green Hospital Certification Systems. J. Health Sci. Prof. 2019, 6, 161–169. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Komurlu, R.; Kalkan Ceceloglu, D.; Arditi, D. Exploring the Barriers to Managing Green Building Construction Projects and Proposed Solutions. Sustainability 2024, 16, 5374. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Garg, A.; Dewan, A. Green Hospitals. In Manual of Hospital Planning and Designing; Springer: Singapore, 2022; pp. 485–498. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- United States Green Building Council (USGBC). Benefits of Green Building. 2023. Available online: https://www.usgbc.org/press/benefits-of-green-building (accessed on 17 December 2024).

- Kusi, E.; Boateng, I.; Danso, H. Energy Consumption and Carbon Emission of Conventional and Green Buildings Using Building Information Modelling (BIM). Int. J. Build. Pathol. Adapt. 2025, 43, 826–854. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Sullivan, G.A.; Petit, H.J.; Reiter, A.J.; Westrick, J.C.; Hu, A.; Dunn, J.B.; Gulack, B.C.; Shah, A.N.; Dsida, R.; Raval, M.V. Environmental Impact and Cost Savings of Operating Room Quality Improvement Initiatives: A Scoping Review. J. Am. Coll. Surg. 2023, 236, 411–423. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Liu, T.; Chen, L.; Yang, M.; Sandanayake, M.; Miao, P.; Shi, Y.; Yap, P.S. Sustainability Considerations of Green Buildings: A Detailed Overview on Current Advancements and Future Considerations. Sustainability 2022, 14, 14393. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Tavsan, F.; Bektas, U. Sustainable Design Approaches of LEED-Certified Healthcare Buildings. J. Inter. Des. Acad. 2023, 3, 120–132. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Read, J.; Meath, C. A Conceptual Framework for Sustainable Evidence-Based Design for Aligning Therapeutic and Sustainability Outcomes in Healthcare Facilities: A Systematic Literature Review. HERD 2025, 18, 1–17. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Mapsted. Latest Hospital Design Trends in 2024. Available online: https://mapsted.com/en-ca/blog/hospital-design-trends (accessed on 23 December 2024).

- Bharara, T.; Gur, R.; Duggal, S.D.; Jena, P.; Khatri, S.; Sharma, P. Green Hospital Initiative by a North Delhi Tertiary Care Hospital: Current Scenario and Future Prospects. J. Clin. Diagn. Res. 2018, 12, DC10–DC14. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Badanta, B.; Porcar Sierra, A.; Fernández, S.T.; Rodríguez Muñoz, F.J.; Pérez-Jiménez, J.M.; Gonzalez-Cano-Caballero, M.; Ruiz-Adame, M.; de-Diego-Cordero, R. Advancing Environmental Sustainability in Healthcare: Review on Perspectives from Health Institutions. Environments 2025, 12, 9. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Lazar, N.; Chithra, K. A Comprehensive Literature Review on Development of Building Sustainability Assessment Systems. J. Build. Eng. 2020, 32, 101450. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- United Nations Development Programme (UNDP). UN Sustainable Development Cooperation Framework 2021–2025; United Nations: New York, NY, USA, 2022; Available online: https://www.undp.org/sites/g/files/zskgke326/files/2022-08/UN%20Sustainable%20Development%20Cooperation%20Framework%202021-2025.pdf (accessed on 17 December 2024).

- Tang, K.H.D.; Foo, H.; Tan, I.S. A Review of the Green Building Rating Systems. IOP Conf. Ser. Mater. Sci. Eng. 2020, 943, 012060. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Marchi, L.; Antonini, E.; Politi, S. Green Building Rating Systems (GBRSs). Encyclopedia 2021, 1, 998–1009. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- El Safty, A.M.K. The Concept of Green Hospitals and Sustainable Practices (Review Article). Egypt. J. Occup. Med. 2024, 48, 117–132. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Danilov, A.; Benuzh, A.; Yeye, O.; Compaore, S.; Rud, N. Design of Healthcare Structures by Green Standards. E3S Web Conf. 2020, 164, 05002. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Weerasinghe, A.S.; Ramachandra, T.; Thurairajah, N. Life Cycle Cost Analysis: Green vs Conventional Buildings in Sri Lanka. Proc. 33rd Annu. ARCOM Conf. 2017, 1, 309–318. Available online: https://www.researchgate.net/publication/328138784_Life_Cycle_Cost_analysis_green_vs_conventional_buildings_in_Sri_Lanka (accessed on 10 January 2025).

- Tuncsiper, C. Digital Transformation and Health Economics: A Bibliometric Analysis on Digital Health. Gumushane Univ. J. Health Sci. 2023, 12, 21–31. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Dion, H.; Evans, M.; Farrell, P. Hospitals Management Transformative Initiatives; Towards Energy Efficiency and Environmental Sustainability in Healthcare Facilities. J. Eng. Des. Technol. 2022, 21, 552–584. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Kouka, D.; Russo, M.; Barreca, F. Building Sustainability Assessment: A Comparison between ITACA, DGNB, HQE and SBTool Alignment with the European Green Deal. Heliyon 2024, 10, e34478. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Yoon, E.; Lim, Y. A Study on Green Building Certification Criteria for Healthcare Facilities—Focused on System and Contents for Healthcare in BREEAM, LEED, CASBEE. J. Korea Inst. Healthc. Archit. 2016, 22, 17–26. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Wang, Q.; Gao, W.; Su, Y.; Cheng, H. Green Building Performance Analysis and Energy-Saving Design Strategies in Dalian, China. Sustainability 2024, 16, 5233. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Illankoon, I.M.; Chethana, S.; Tam, V.W.Y.; Le, K.N.; Shen, L. Key Credit Criteria Among International Green Building Rating Tools. J. Clean. Prod. 2017, 164, 209–224. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Wardana, M.; Setyonugroho, W.; Pribadi, F. Cost and Environmental Benefits of Green Hospitals: A Review. J. Aisyah J. Ilmu Kesehatan 2024, 9, 1–12. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Li, Y.; Chen, X.; Wang, X.; Xu, Y.; Chen, P.-H. A Review of Studies on Green Building Assessment Methods by Comparative Analysis. Energy Build. 2017, 146, 152–159. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Assefa, S.; Lee, H.-Y.; Shiue, F.-J. Sustainability Performance of Green Building Rating Systems (GBRSs) in an Integration Model. Buildings 2022, 12(2), 208. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Alkhayatt, N.; Agha, R. Applied the Indicators of Green Building in Educational Hospitals in Iraq. Assoc. Arab Univ. J. Eng. Sci. 2024, 31, 20–33. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Practice Greenhealth. 2021 Sustainability Benchmark Data. Available online: https://practicegreenhealth.org/sites/default/files/2023-03/2021.Benchmark.Tables.pdf (accessed on 30 January 2025).

- Leadership in Energy and Environmental Design (LEED) v4. 1, Building Design and Construction Guide; U.S. Green Building Council: Washington, DC, USA, 2024. [Google Scholar]

- BREEAM, New Construction Version 6. 5079.

- CASBEE. Comprehensive Certification System for Built Environment Efficiency, CASBEE for Building New Construction, Technical Manual; 2014 Edition. Accessed on . Available online: http://www.ibec.or. 19 December.

- Dhillon, V.S.; Kaur, D. Green Hospital and Climate Change: Their Interrelationship and the Way Forward. J. Clin. Diagn. Res. 2015, 9, LE01–LE05. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Wu, Z. Evaluation of a Sustainable Hospital Design Based on Its Social and Environmental Outcomes. Master’s Thesis, Cornell University, Ithaca, NY, USA, 2011. Available online: http://iwsp.human.cornell.edu/files/2013/09/Ziqi-Wu-2011-19cxn60.pdf (accessed on 17 December 2024).

- Doan, D.T.; Tran, H.V.; Aigwi, I.E.; Naismith, N.; Ghaffarianhoseini, A.; Ghaffarianhoseini, A. Green Building Rating Systems: A Critical Comparison between LOTUS, LEED, and Green Mark. Environ. Res. Commun. 2023, 5, 075008. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Green Building Council of Australia (GBCA). Green Star Design and As Built v1.2, Submission Guidelines; Green Building Council of Australia: Sydney, Australia, 2017. [Google Scholar]

- YeS-TR, Ministry of Environment, Urbanization and Climate Change, Republic of Türkiye. Green Certification Guide: Regulation on Green Certification of Buildings and Settlements; Official Gazette: Ankara, Türkiye, 2022; Volume 31864, Available online: https://www.resmigazete.gov.tr/eskiler/2022/06/20220612-1.htm (accessed on 16 September 2025).

- Indian Green Building Council (IGBC). Green Healthcare Facilities Rating System Version 1.0 Abridged Reference Guide; Indian Green Building Council: Hyderabad, India, 2020; Available online: https://www.igbc.in (accessed on 4 December 2024).

- Green Building Council Indonesia (GBCI). GREENSHIP New Building Version 1.2: Rating Tools; Green Building Council Indonesia: Jakarta, Indonesia, 2024. [Google Scholar]

- Green Building Index (GBI). GBI Executıve Summary, Available online:. Available online: https://www.greenbuildingindex.org/how-gbi-works/gbi-executive-summary/ (accessed on 26 September 2025).

- LEED Support. 2024. Applying LEED to Healthcare Projects. U.S. Green Building Council, 2024. Available online: https://support.usgbc.org/hc/en-us/articles/12126333712659-Applying-LEED-to-healthcare-projects (accessed on 23 December 2024).

- BREEAM Tools. Accessed on . Available online: https://tools.breeam.com/projects/explore/index. 20 December.

- Sahamir, S.R.; Zakaria, R.; Alqaifi, G.; Abidin, N.I.; Rooshdi, R.R.R.M. Investigation of Green Assessment Criteria and Sub-criteria for Public Hospital Building Development in Malaysia. Chem. Eng. Trans. 2017, 56, 307–312. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Kilic, H.C.; Guduk, Ö. The Concept of a Green Hospital is an Example of a Hospital Based on the Expectations of End Users in Turkiye. GU J. Health Sci. 2018, 7, 167–169. [Google Scholar]

- Ullah, Z.; Thaheem, M.J.; Waheed, A.; Maqsoom, A. Are LEED-Certified Healthcare Buildings in the USA Truly Impacting Sustainability? Indoor Built Environ. 2020, 29, 7–23. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Green Building Council Australia (GBCA). About Us. Available online: https://new.gbca.org.au/about/about-us/ (accessed on 18 December 2024).

- Green Building Council Australia (GBCA). Green Star Healthcare v1 Fact Sheet, Available online:. Available online: https://www.gbca.org.au/uploads/144/1936/Fact%20Sheet%20Healthcare.pdf?_ga=2.123440335.576783461.1662070796-851839291.1662070788 (accessed on 26 September 2025).

- CASBEE. Composition of the Certification Software (CASBEE). Available online: https://www.ibecs.or.jp/CASBEE/english/softwareE.htm (accessed on 10 September 2025).

- Kotesli, T. Evaluation of the Local System Requirement within the Scope of Green Building Certifications. Master's Thesis, Mimar Sinan Fine Arts University, Istanbul, Turkiye, 2013; pp. 21–43. [Google Scholar]

- Ministry of Environment, Urbanization and Climate Change (MEUCC), Republic of Türkiye. Green Certificate Mandatory for Public Buildings. Available online: https://www.csb.gov.tr/kamu-binalarina-yesil-sertifika-zorunlugu-getiriliyor-bakanlik-faaliyetleri-40378 (accessed on 30 November 2024).

- Indian Green Building Council (IGBC). IGBC Green Healthcare Facilities; Indian Green Building Council: Hyderabad, India, 2024; Available online: https://igbc.in/igbc/redirectHtml.htm?redVal=showigbcgreenhealthcare (accessed on 5 December 2024).

- Indian Green Building Council (IGBC). Healthcare in India Health Safety Savings; Indian Green Building Council: Hyderabad, India, 2019; Available online: https://igbc.in/frontend-assets/html_pdfs/booklet%20-%20healthcare%20in%20India.pdf (accessed on 4 December 2024).

- Sutanto, S.; Putri, E.I.K.; Pramudya, B.; Utomo, S.W. Atribut Penilaian Keberlanjutan Pengelolaan Lingkungan Rumah Sakit Menuju Green Hospital di Indonesia. J. Kesehat. Lingkung. Indones. 2020, 19, 51–61. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Green Building Index (GBI). Non-Residential New Construction (NRNC): Hospital Version 1.0; Green Building Index: Kuala Lumpur, Malaysia, 2015. [Google Scholar]

- Newman, P.; Kenworthy, J. The End of Automobile Dependence: How Cities Are Moving Beyond Car-Based Planning; Island Press: Washington, DC, USA, 2015. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Buser, M.A.; Ramezani, S.; Stead, D.; Arts, J. Policy Packaging for Land-Use and Transport Planning: The State-of-the-Art. Transp. Rev. 2025, 45, 333–365. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]