1. Introduction

The global building sector is one of the primary contributors to environmental degradation, responsible for over one-third of total energy use and carbon dioxide emissions [

1]. Due to its scale and environmental footprint, the sector holds a pivotal role in achieving international climate targets and sustainable development. In response, green building certification systems (GBCS) have emerged as key tools for driving sustainable practices across environmental, economic, and social domains.

Among the most widely adopted GBCS are LEED (Leadership in Energy and Environmental Design), BREEAM (Building Research Establishment Environmental Assessment Method), and the WELL Building Standard. These systems aim to guide sustainable building design, construction, and operation by establishing clear criteria and performance benchmarks.

LEED, introduced by the U.S. Green Building Council in 1998, emphasizes carbon emission reduction, energy efficiency, and responsible material use. LEED-certified buildings have demonstrated energy savings of up to 30% compared to conventional structures [

2]. BREEAM, developed in the UK in 1990, applies a lifecycle-based evaluation across areas such as energy use, biodiversity, and water efficiency. Research suggests that BREEAM-certified projects can achieve up to 25% reductions in total carbon emissions [

3].

In contrast, the WELL Building Standard, introduced in 2014, prioritizes human health and well-being. It evaluates indoor air quality, thermal comfort, lighting, and acoustic performance, connecting social and environmental sustainability [

4]. While timely—particularly in the context of post-pandemic indoor health—WELL has been critiqued for comparatively weak emphasis on energy performance and embodied carbon [

5].

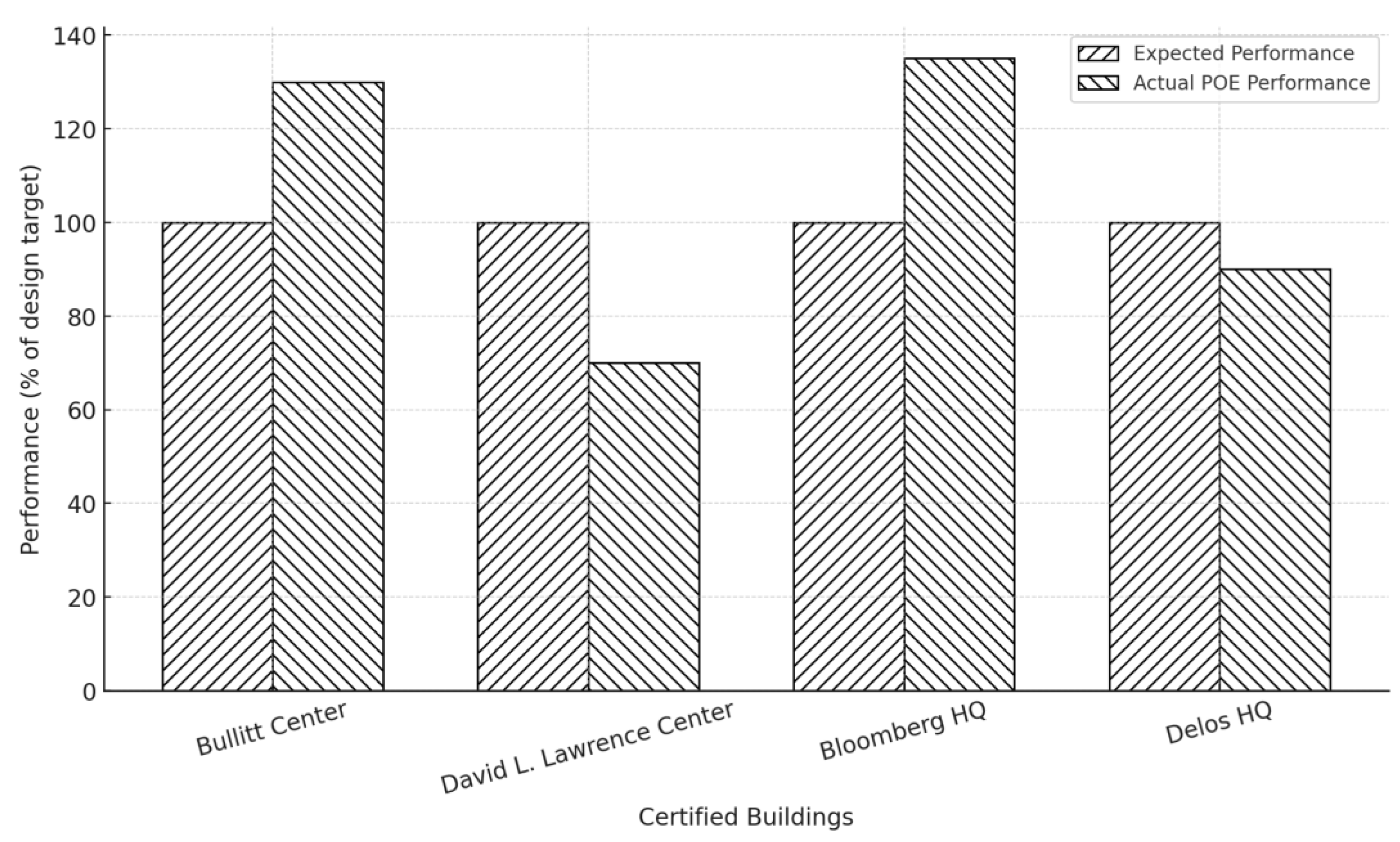

Despite the strengths of these frameworks, a persistent challenge remains: the “performance gap”—the difference between projected performance at the design stage and actual post-occupancy outcomes. For instance, the Bullitt Center in Seattle, a LEED Platinum-certified building, exceeded its targets with an energy use intensity (EUI) of just 16 kBtu/ft²/year due to real-time data monitoring and adaptive HVAC control [

6]. In contrast, the David L. Lawrence Convention Center, though LEED Gold-certified, failed to meet energy expectations due to operational inefficiencies revealed through post-occupancy evaluation (POE) [

7].

POE has thus become an essential feedback mechanism, providing data on real-world performance related to energy use, occupant satisfaction, and indoor environmental quality (IEQ). Systems like BREEAM incorporate POE through operational reviews, such as those implemented at Bloomberg’s European Headquarters, which achieved 30% lower energy use than peer buildings [

8]. Similarly, WELL-certified buildings like Mirvac HQ in Sydney and Delos HQ in New York integrate real-time monitoring of IEQ to optimize occupant health and comfort [

9,

10].

However, existing literature tends to focus on individual systems or on specific aspects (e.g., energy or health), often without holistic comparison. Furthermore, limited integration of post-occupancy insights into certification revisions remains a critical gap. This study addresses this gap by offering a comprehensive comparative analysis of LEED, BREEAM, and WELL using a Triple Bottom Line (TBL) framework that spans environmental, social, and economic criteria.

The study adopts a secondary research approach, integrating academic literature, industry case studies, and post-occupancy data from global projects. It also evaluates the alignment of certification systems with the United Nations Sustainable Development Goals (SDGs) particularly those related to climate action (SDG 13), health and well-being (SDG 3), and sustainable cities (SDG 11).

By critically examining both strengths and systemic limitations, this research aims to inform the evolution of green certification systems and offer actionable recommendations for improving their impact in real-world conditions. In doing so, it contributes to broader efforts in climate change mitigation, sustainable urban development, and human-centered design.

2. Materials and Methods

2.1. Research Approach

This study adopts a qualitative comparative methodology, grounded in secondary data analysis, to evaluate the effectiveness of three globally recognized green building certification systems—LEED, BREEAM, and WELL—through the lens of the Triple Bottom Line (TBL) framework. This model facilitates the integration of environmental, social, and economic sustainability criteria in a coherent evaluation approach [

11,

12,

13].

Rather than relying on primary data, the research is theory-driven and utilizes official certification documentation, academic studies, and real-world case analyses to investigate each system's contributions to sustainable development and their alignment with the United Nations Sustainable Development Goals (SDGs) [

14,

15].

2.2. Data Sources

The study synthesizes information from three validated source categories:

Official Certification Manuals: Technical guides and documentation from the U.S. Green Building Council (LEED), the Building Research Establishment (BREEAM), and the International WELL Building Institute (WELL) provided primary details about system structures, categories, and scoring criteria [

16,

17,

18].

Peer-Reviewed Literature: Academic publications were selected for their focus on green building certification impacts, post-occupancy evaluation (POE), energy and lifecycle performance, and occupant well-being [

12,

13,

19,

20,

21].

Industry Case Studies: Notable certified buildings—such as the Bullitt Center (LEED Platinum), Bloomberg HQ (BREEAM Outstanding), and Delos HQ (WELL Platinum)—were used to assess real-world operational outcomes and the persistent “performance gap” between design expectations and actual performance [

6,

8,

10,

22].

All data sources were evaluated for relevance, credibility, and contextual alignment with the TBL dimensions.

2.3. Analytical Framework

The evaluation process employed a two-phase analytical structure:

System-Level Analysis: Each certification system was examined independently to document its sustainability objectives, structural framework, and functional priorities. For instance, LEED focuses on energy efficiency and site planning [

12], BREEAM emphasizes lifecycle assessment and biodiversity [

20], and WELL centers around occupant health and indoor environmental quality [

13,

21].

Comparative Evaluation via TBL: The three systems were then assessed in parallel using the TBL framework:

Environmental: Metrics related to energy efficiency, water use, carbon emissions, and resource conservation [

12,

20];

Social: Occupant well-being, indoor environmental quality (IEQ), equity, and mental health [

13,

21];

Economic: Lifecycle cost efficiency, operational performance, and long-term resilience [

19,

22].

Each criterion was further substantiated by data from post-occupancy evaluations (POEs) where available.

2.4. Inclusion and Exclusion Criteria

The analysis focused exclusively on LEED, BREEAM, and WELL, due to their international prominence, contrasting orientations, and established application across multiple geographic contexts [

14,

16]. Systems such as Green Star or GSAS were excluded due to region-specific scoring methodologies that limit global comparability.

2.5. Study Limitations

A primary limitation of this study lies in its reliance on secondary data, which may include inconsistent methodologies or limited access to building-specific POE results. Furthermore, the availability of real-time operational data for certified buildings is uneven, particularly across different regions and building typologies [

19,

22]. Nevertheless, this triangulated approach offers a structured basis for comparing certification system performance within a global sustainability framework.

3. Benchmark and Comparative Analysis

Green building certification systems have become foundational to global sustainability frameworks, providing the architecture, real estate, and infrastructure sectors with measurable, policy-aligned tools to reduce carbon, optimize resource use, and enhance occupant well-being. Among the most globally recognized frameworks—LEED, BREEAM, and WELL—each embodies a distinct approach to evaluating sustainability across environmental, social, and economic dimensions. This chapter presents a consolidated benchmark analysis, unifying findings from the literature review, technical manuals, post-occupancy evaluations, and regional policy studies, with a comparative lens informed by the Triple Bottom Line (TBL) framework.

3.1. Global Deployment and Regional Adaptation

LEED, developed by the U.S. Green Building Council, has achieved global reach with over 180 countries applying its framework, most strongly represented in the United States, India, China, and the UAE studies shows that this increased knowledge and awareness affect the real estate market [

16,

23]. BREEAM, led by the UK’s BRE, maintains strong application in Europe and has expanded through region-specific adaptations such as BREEAM-NL and BREEAM-Gulf [

17]. WELL, though newer (launched in 2014), has seen accelerated uptake post-pandemic due to its occupant-centric health metrics, particularly in urban corporate sectors in North America, Australia, and Southeast Asia [

18].

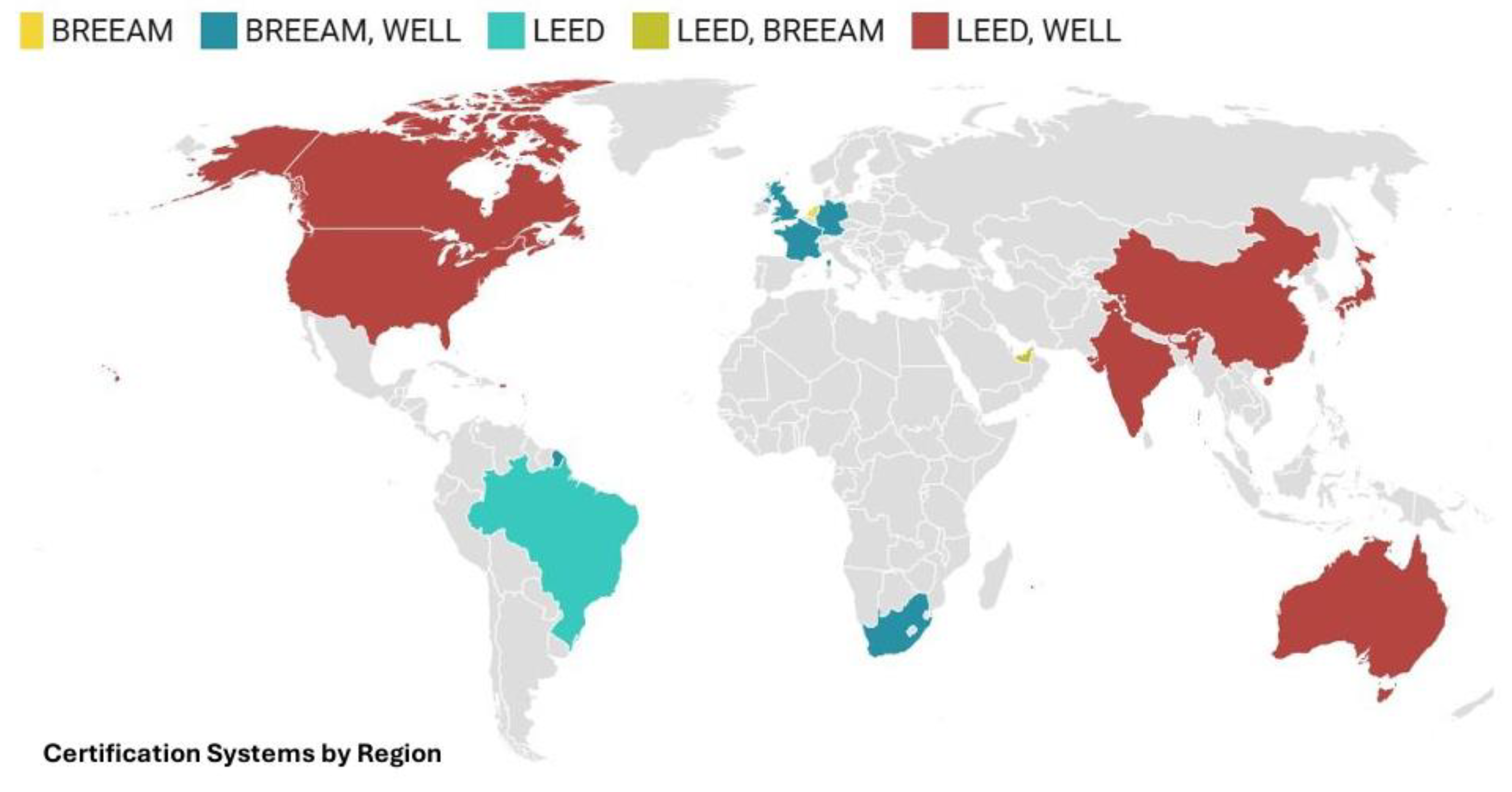

Figure 1 shows LEED-WELL dominance in North America, East Asia, and Oceania; BREEAM prevalence in Western Europe; and hybrid implementation in South Africa and Brazil. All the information have been collected from the certification systems official websites info and are presented in

Table 1. The increasing convergence in regional systems is driven by climate-specific needs and the desire to align with national energy action plans (e.g., India’s ECBC and UK’s Future Homes Standard) [

24,

25,

26,

27].

3.2. Comparative Evaluation of Certification Priorities

Each certification system exhibits internal prioritization of sustainability objectives. Each certification system emphasizes sustainability objectives through internally weighted criteria, as shown in their technical manuals and public guidance documentation.

Table 2 below summarizes the comparative emphasis on core categories based on official scoring rubrics from LEED v4.1, BREEAM, and WELL [

16,

17,

18]. These values were normalized to enable cross-system comparison.:

Sources confirm that LEED places greatest emphasis on operational energy savings [

28], while BREEAM offers a more holistic lifecycle approach, incorporating embodied carbon and regional biodiversity [

29]. WELL repositions the occupant as the central sustainability subject, anchoring its metrics around health outcomes, IEQ, and well-being [

21,

30].

A precise comparative evaluation of LEED, BREEAM, and WELL requires not only a surface comparison of credit weightings but also a deep examination of their criteria taxonomy, methodological constructs, and evaluation logics. Each certification system operationalizes sustainability differently across thematic domains, resulting in both epistemological divergence—differences in how sustainability is conceptualized—and functional asymmetries—differences in how performance is measured and verified.

Table 3 compares the structural logic of each system, including their scoring basis (e.g., point-based vs. performance optimization), verification methods, and certification tiers. This comparative framing helps illustrate how methodological design affects the credibility, transparency, and replicability of sustainability outcomes across the three systems.

The criteria across the three systems cluster around seven major thematic areas. However, each certification system defines and implements these categories with varying levels of scope, depth, and stringency.

Table 4 was developed through cross-analysis of certification manuals, project documentation, and post-occupancy evaluations from certified buildings. The table illustrates how each system addresses these themes—such as energy, water, or health—through distinct operational strategies and credit structures. This comparative mapping reveals areas of overlap as well as systemic gaps, particularly in domains like lifecycle integration and health-energy trade-offs.

LEED adopts a performance-anchored, engineering-led model centered around operational energy optimization and material impact, but its IEQ provisions are largely prescriptive and not dynamically verified post-occupancy. Critics have described it as “quantitative but weak in longitudinal tracking” [

28].

BREEAM introduces a hybrid model blending LCA with regional weighting schemes, especially strong in Europe. Its ecological criteria (e.g., biodiversity, flood resilience) extend beyond building-centric scopes. However, its complex documentation protocols can hinder adoption outside the UK [

29].

WELL reframes sustainability as a health science issue, grounding its approach in evidence-based medicine, human biology, and biophilic design theory. While its feedback mechanisms (e.g., SAMBA sensors, user surveys) enhance IEQ credibility, it lacks substantive modeling of energy or carbon intensity [

30].

3.3. Triple Bottom Line Benchmarking

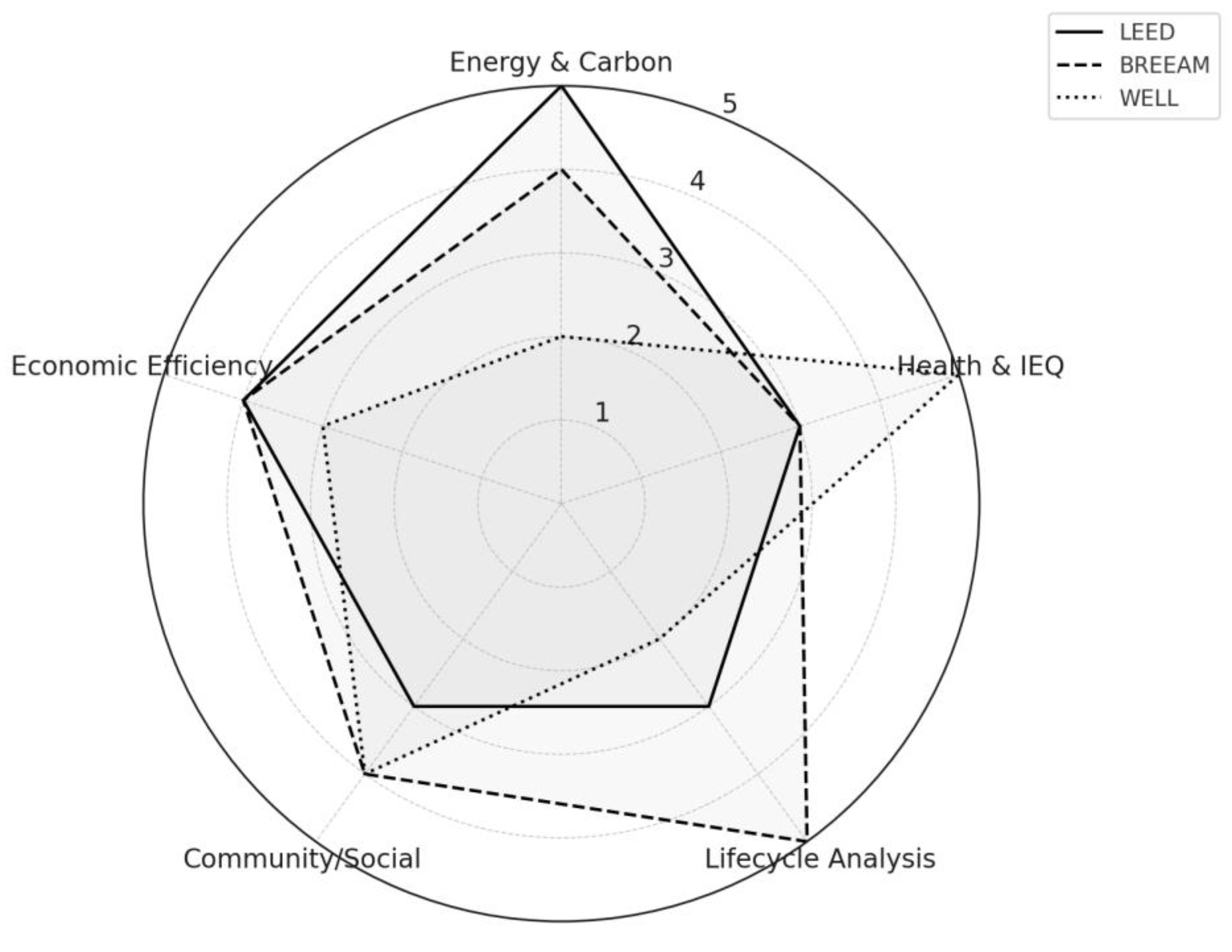

A radar chart comparison (

Figure 4) further illustrates the differentiated strengths of each certification scheme:

The radar chart presented in

Figure 2 offers a visual synthesis of how LEED, BREEAM, and WELL certification systems perform across five core sustainability metrics derived from the Triple Bottom Line framework: Energy & Carbon, Health & Indoor Environmental Quality (IEQ), Lifecycle Analysis, Community/Social Integration, and Economic Efficiency.

Each axis on the radar represents a normalized score (0–5), constructed from an aggregate of credit weightings, published performance data, and peer-reviewed case study benchmarks [

28,

29,

30,

31,

32,

33].

LEED demonstrates the highest performance in the Energy & Carbon category due to its strict requirements for energy modeling, site optimization, and renewable integration. Projects such as the Bullitt Center highlight LEED’s effectiveness in achieving ultra-low energy use intensities (EUIs) when paired with performance tracking [

22,

28,

34,

35]. It also shows solid scores in Economic Efficiency, driven by energy cost savings and demand-side management programs. However, LEED is relatively weaker in Lifecycle Analysis and Health & IEQ, where its metrics are optional or marginally weighted [

31].

BREEAM ranks highest in Lifecycle Analysis, emphasizing full lifecycle carbon accounting, embodied emissions, and biodiversity preservation [

29]. Its system rewards the use of locally sourced materials, passive systems, and long-term design resilience. It also fares well in Community/Social and Economic Efficiency, particularly in European contexts where policies like the EU Taxonomy influence building codes [

32]. Its performance in Health & IEQ, however, while included, is not as extensively developed as in WELL.

WELL dominates the Health & IEQ axis, with a high concentration of metrics focused on thermal comfort, acoustic quality, daylighting, mental health, and air purity [

30,

33]. Unlike LEED or BREEAM, WELL includes sensor-based verification and user experience surveys as part of its validation process. It also performs well in Community/Social, particularly through inclusive measures and behavioral wellness programming. Nevertheless, WELL underperforms in Energy & Carbon and Lifecycle Analysis due to limited environmental depth and the absence of requirements for embodied energy or operational carbon tracking.

Overall, the radar visualization underscores the complementary nature of these systems: while none fully satisfies all sustainability dimensions, their strengths are distinct and, when combined, can provide comprehensive coverage of TBL criteria. This supports growing advocacy for dual certification approaches, such as LEED+WELL or BREEAM+WELL, in delivering holistic sustainability outcomes.

3.4. Post-Occupancy Evaluation and Performance Gaps

Despite rigorous pre-certification modeling and sustainability forecasting in green building certification systems (GBCS), there exists a persistent and well-documented discrepancy between expected and realized performance — a phenomenon widely referred to as the "performance gap" [

34]. This gap undermines the credibility and effectiveness of even the most lauded rating systems such as LEED, BREEAM, and WELL, necessitating a more granular examination of post-occupancy evaluation (POE) practices as an essential bridge between design-stage predictions and real-world operational behavior [

30,

36].

POE, by definition, is a systematic process of assessing building performance once it is in use, capturing real-time data on factors such as energy consumption, occupant comfort, indoor environmental quality (IEQ), and HVAC functionality [

30]. Unlike static certification checklists, POE represents a dynamic feedback loop, capable of informing future design iterations, identifying operational inefficiencies, and recalibrating user interactions with the built environment.

3.4.1. Key Case-Based Insights on POE Effectiveness

Table 5 below synthesizes findings from key POE case studies across three certification systems. These illustrate how post-occupancy feedback can either validate sustainability achievements or expose substantial underperformance.

These examples show that certification status does not inherently guarantee high post-occupancy performance. In fact, studies suggest that up to 30–50% of LEED buildings underperform compared to projections [

35,

36], often due to occupant behavior, misaligned maintenance regimes, or incomplete commissioning [

30].

In WELL-certified environments, the performance gap manifests not in energy failures, but in overcompensation of thermal comfort systems, where strict air quality and acoustic parameters may inadvertently raise energy loads — revealing a trade-off between environmental and health priorities [

5,

37].

In contrast, buildings with embedded POE protocols (like the Bullitt Center) exemplify a best-practice paradigm in which continuous performance tracking enables adaptive management. By linking smart metering with real-time feedback, such projects not only achieve design targets but often exceed them [

38,

39,

40,

41,

42,

43].

3.4.2. Implications for Certification Frameworks

The consistent emergence of the performance gap across leading rating systems exposes a fundamental weakness in static, checklist-driven assessment models. As such, scholars and industry experts advocate the integration of POE into certification recertification loops, enabling:

✓ Data-driven corrections during operation

✓ Verification of real-time energy and IEQ metrics

✓ Stakeholder-responsive facility management

✓ Iterative design improvements across building portfolios [

44,

45,

46]

To enhance credibility and sustainability alignment, certifications must evolve toward a hybrid model — combining design compliance with longitudinal operational analytics.

As shown in

Figure 3, the post-occupancy performance of green-certified buildings demonstrates significant variability relative to their predicted design targets. The Bullitt Center, a LEED Platinum-certified building, exemplifies best practices in real-time performance monitoring, outperforming its energy use predictions by approximately 30% due to integrated POE mechanisms, advanced sub-metering, and proactive HVAC adjustments [

35]. In stark contrast, the David L. Lawrence Convention Center, despite its LEED Gold rating, underperformed by 30%, largely due to insufficient commissioning and a lack of operational training, revealing critical deficiencies in aligning design-stage modeling with post-occupancy reality [

36].

The Bloomberg Headquarters, rated BREEAM Outstanding, illustrates the value of dynamic recalibration, where lighting and HVAC systems optimized through POE achieved a 35% performance surplus, significantly surpassing expectations [

29]. On the other hand, the Delos Headquarters, a WELL Platinum-certified facility, demonstrated a trade-off between enhanced occupant comfort and energy use; real-time environmental controls improved thermal and acoustic conditions but inadvertently increased HVAC energy intensity [

33].

These results underscore the heterogeneous nature of certification outcomes, validating that high design scores alone are insufficient predictors of real-world sustainability performance. Instead, they emphasize the imperative role of operational transparency, continuous metering, and feedback-driven building management in fulfilling the holistic goals of green building certification systems.

3.5. SDG Alignment and Sustainability Leadership

The systems also vary in how well they align with the United Nations Sustainable Development Goals (SDGs).

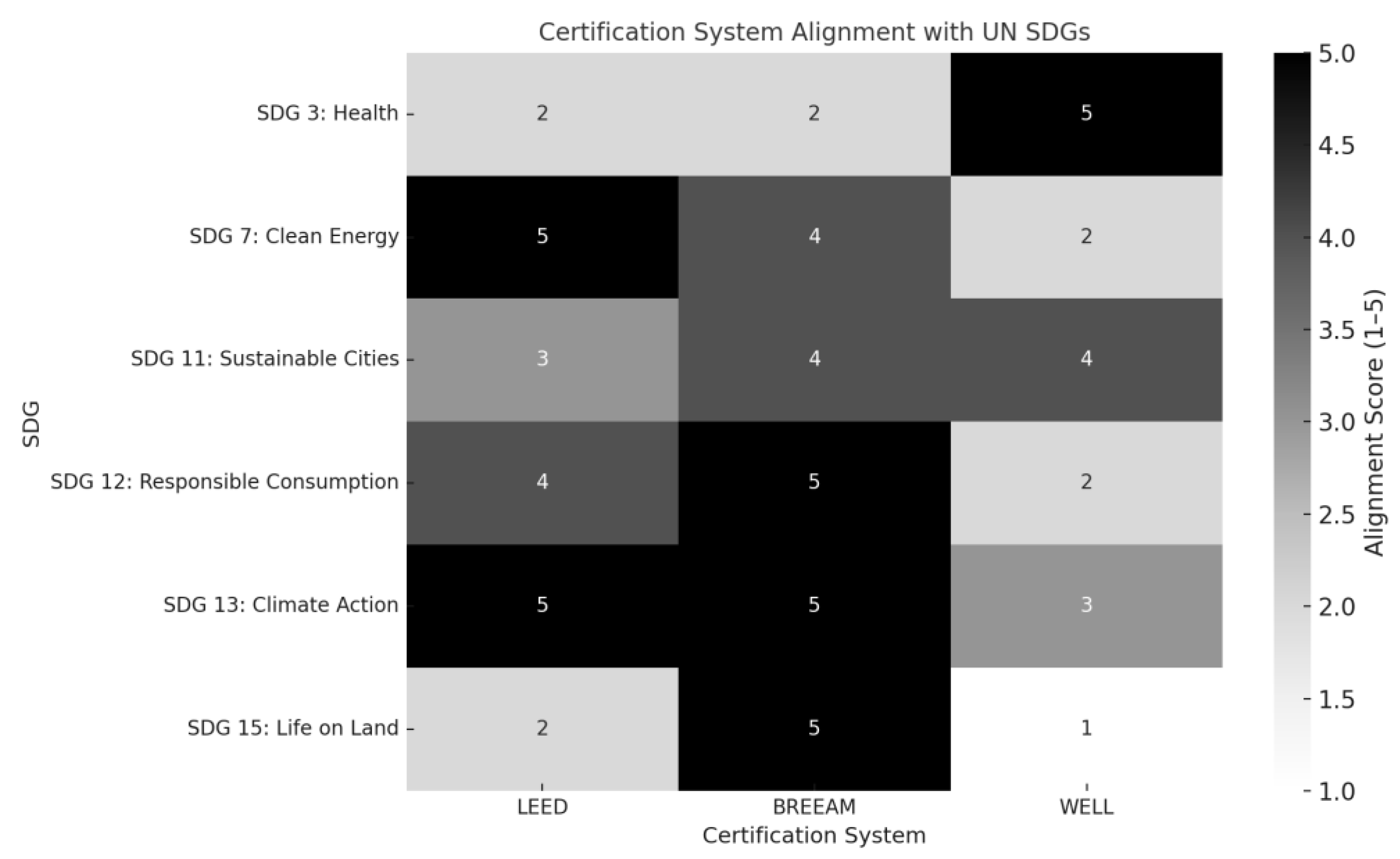

As shown in

Table 6, each system exhibits unique alignments with specific SDG targets, shaped by its methodological priorities, indicator selection, and certification culture. More specifically WELL dominates in SDG 3 (health), while BREEAM is aligned with SDGs 12 and 13 through its resource and carbon tracking systems. LEED strongly targets SDG 7 and 13 via renewable energy and GHG reduction requirements [

14,

28,

29,

30].

The alignment of LEED, BREEAM, and WELL with the United Nations Sustainable Development Goals (SDGs) provides an essential lens to evaluate their broader societal and ecological contributions beyond operational performance.

SDG 3 – Good Health and Well-Being

The WELL Building Standard demonstrates a robust commitment to SDG 3, prioritizing occupant health outcomes through its emphasis on indoor air quality, thermal comfort, lighting, acoustic performance, mental health, and fitness-supportive infrastructure [

5,

9,

10,

28,

33]. The system’s reliance on post-occupancy surveys and sensor-based IEQ tracking (e.g., SAMBA at Mirvac HQ [

9]) ensures that WELL-certified spaces continuously support physiological and psychological well-being. Unlike LEED and BREEAM, WELL's structure explicitly integrates biophilic design, non-toxic materials, and mental restoration elements, which are essential under WHO’s Healthy Buildings framework [

42].

SDG 6 – Clean Water and Sanitation

BREEAM and LEED align moderately with SDG 6 by incorporating water efficiency metrics, such as rainwater harvesting, low-flow fixtures, and greywater reuse [

24,

31]. BREEAM’s regional adaptations (e.g., BREEAM Gulf) further strengthen this alignment by addressing water scarcity through context-specific water benchmarks [

47]. WELL, while considering potable water quality for user health, lacks broader water conservation strategies, limiting its impact on systemic water sustainability [

33].

SDG 7 – Affordable and Clean Energy

LEED is the most aligned with SDG 7, especially through its Energy and Atmosphere category, which rewards projects that integrate on-site renewables, passive design strategies, energy modeling, and smart metering [

24,

28,

31]. The Bullitt Center case demonstrates LEED’s potential in operationalizing energy autonomy, where performance-based credits incentivize design optimization across energy use intensity (EUI) and net-zero readiness [

35]. BREEAM similarly integrates renewable targets, though its scoring is more procedural and lifecycle-focused [

29,

47].

SDG 11 – Sustainable Cities and Communities

All three systems contribute to SDG 11, though in differing ways. LEED and BREEAM support urban sustainability through categories on site location, transportation, resilience planning, and community connectivity [

24,

29]. BREEAM’s urban planning modules (e.g., “Land Use and Ecology”) provide tools to reduce urban heat island effects, promote biodiversity corridors, and improve walkability, particularly in masterplanning projects [

32,

34]. WELL, on the other hand, engages with this SDG through the lens of user inclusivity, accessibility, and mental wellness in dense urban settings, enhancing social sustainability dimensions often neglected in traditional environmental tools [

30,

33,

42].

SDG 12 – Responsible Consumption and Production

BREEAM stands out in its comprehensive integration of lifecycle assessment (LCA), embodied carbon, and circular economy principles, making it the most relevant certification under SDG 12 [

32,

34]. Its Material Efficiency and Waste categories reward local sourcing, adaptive reuse, and dematerialization — aligning with EU goals for resource neutrality. LEED addresses material sustainability as well but lacks the granularity of BREEAM’s end-of-life and supply chain impact scoring [

24,

26]. WELL has limited alignment with SDG 12, focusing more on human-centric aspects rather than resource systemicity [

33].

SDG 13 – Climate Action

Both LEED and BREEAM are directly aligned with SDG 13 by integrating greenhouse gas (GHG) assessments, carbon mitigation strategies, and climate resilience planning [

24,

29,

32]. LEED emphasizes operational carbon, including tools for energy simulation and emissions modeling (e.g., ASHRAE 90.1 compliance), while BREEAM expands its scope to embodied carbon and material sourcing emissions. Projects certified under these systems often contribute directly to national climate targets or green finance initiatives. WELL, despite offering health-oriented climate adaptation, lacks direct carbon measurement or energy reduction obligations, thereby making a limited contribution to this goal [

33].

3.6. Limitations, Regionalization, and Systemic Divergences

Despite growing global uptake, green building certification systems (GBCS) such as LEED, BREEAM, and WELL continue to exhibit significant adaptation challenges when deployed across varied geographical, climatic, and regulatory contexts. These limitations affect both the technical applicability of sustainability metrics and the cultural alignment of health, comfort, and social well-being parameters.

3.6.1. Limitations in Geographic Portability and Climatic Sensitivity

LEED, originating in the U.S., remains predominantly structured around North American codes, energy baselines (e.g., ASHRAE), and climate assumptions, creating friction when applied in European, African, and Middle Eastern regions. In arid or tropical climates, for example, LEED’s emphasis on HVAC efficiency and solar shading may not align with local building norms or passive design traditions, often leading to low local relevance and high cost of compliance.

BREEAM, by contrast, adopts a regional modular model, with variants like BREEAM International, BREEAM Gulf, and BREEAM NOR, designed to recalibrate baseline metrics such as water availability, solar exposure, and indigenous biodiversity. These schemes demonstrate superior contextual flexibility, for example, using native vegetation baselines and local thermal comfort indices in arid zones. However, critics argue that BREEAM’s documentation-heavy approach and complex scoring can deter widespread adoption in emerging markets.

WELL faces its own regional limitations, particularly in hot, humid, or high-heat regions. In countries like the UAE, Saudi Arabia, or India, maintaining WELL-compliant levels of thermal comfort, indoor air quality, and natural ventilation can paradoxically result in higher HVAC-related energy use, undercutting sustainability gains. This highlights a core conflict between comfort-centric design and carbon minimization, a trade-off not yet reconciled in WELL’s standard structure.

3.6.2. Systemic Divergences: Integrative Challenges

From a systems integration standpoint, the fragmentation of sustainability dimensions across LEED (environmental), BREEAM (lifecycle and governance), and WELL (health and wellness) creates functional silos. As urban environments become more complex, research increasingly calls for hybridized frameworks that blend LEED’s energy and water rigor with BREEAM’s lifecycle realism and WELL’s occupant-centered strategies. For example, combining POE-backed operational performance from LEED with WELL’s real-time environmental sensor feedback could create continuous verification loops, reducing the performance gap.

The need for this integration is also reflected in growing climate-health convergence frameworks, where carbon reduction, heat resilience, and social equity intersect. However, as yet, no certification program offers a truly cross-cutting, SDG-optimized solution adaptable across global bioclimatic and socioeconomic zones.

3.7. Conclusions of the Benchmark Comparative Analysis

This benchmark and comparative analysis reveal that no single certification system provides holistic coverage across all sustainability domains. Each excels in distinct aspects:

LEED leads in operational energy efficiency, emissions tracking, and material optimization, aligning most strongly with SDGs 7 and 13.

BREEAM outperforms in lifecycle analysis, circular economy integration, and biodiversity, making it a natural fit for SDGs 12 and 15.

WELL remains unmatched in advancing occupant well-being, mental health, and indoor environmental quality, making it the leading tool for realizing SDG 3.

Nevertheless, performance gaps persist, and regional incompatibility reduce efficacy without targeted localization. The lack of post-occupancy adaptation mechanisms and dynamic feedback loops continues to limit all three systems’ potential in climate-responsive design. To move forward, the field must embrace multi-criteria certification pathways, where credits are not merely additive but interoperable across tools. Future green building certifications should be incorporated:

Region-specific baselines rooted in local climatic, cultural, and ecological parameters.

Cross-certified POE integration to track actual use vs. design targets.

Unified indicators aligned with SDG metrics, to facilitate global benchmarking and ESG reporting.

Ultimately, a next-generation certification ecosystem should be modular, adaptive, and performance-verified, blending environmental resilience with social well-being and economic efficiency in ways today’s siloed frameworks still fall short of achieving.

4. Results & Discussion

The comparative evaluation of LEED, BREEAM, and WELL across global benchmark cases reveals distinct orientations in certification methodology and thematic emphasis. These systems operate under structurally divergent paradigms: LEED is primarily performance-anchored in energy and materials; BREEAM adopts a lifecycle and ecological foot printing lens; and WELL redefines building sustainability through the health and psychological well-being of occupants.

The case studies confirm that LEED-certified buildings consistently demonstrate superior outcomes in energy modeling and carbon intensity reduction, attributed to rigorous baseline modeling aligned with ASHRAE standards. BREEAM-certified projects, such as Bloomberg HQ, reveal deeper engagement with environmental management protocols, biodiversity considerations, and post-construction operational guidance [

47]. WELL buildings, on the other hand, exhibit the strongest performance in indoor environmental quality and user-centric design, yet often lack the embedded carbon tracking or LCA stringency found in LEED or BREEAM [

48].

The radar plot comparison (

Figure 2) illustrates these differences quantitatively. LEED scored highest on energy and materials; BREEAM led in lifecycle and management practices; WELL scored maximally in health and user feedback. The disparity in coverage suggests that these systems are not interchangeable. Rather, they act as complementary frameworks, each excelling in certain domains while leaving others underrepresented.

Further insights emerge when certification coverage is compared against selected Sustainable Development Goals (SDGs). The alignment matrix (

Figure 4) confirms that no certification system addresses the SDGs holistically. LEED performs strongly on SDG 7 (Clean Energy) and SDG 12 (Responsible Consumption), while BREEAM shows alignment with SDG 13 (Climate Action) and SDG 15 (Life on Land), largely due to its ecological design incentives [

49]. WELL, in contrast, aligns more directly with SDG 3 (Good Health and Well-being) and SDG 11 (Sustainable Cities), supported by its focus on biophilic design, air quality, and post-occupancy surveys [

50].

Figure 4.

Certification System Alignment with UN SDGs (1 = Low, 5 = High).

Figure 4.

Certification System Alignment with UN SDGs (1 = Low, 5 = High).

Post-occupancy evaluation (POE) emerges as a core divergence point. While WELL mandates POE through integrated feedback systems and biometric metrics, LEED and BREEAM consider it optional or limited to commissioning stages. The absence of longitudinal verification in LEED- and BREEAM-certified buildings raises concerns about performance decay and occupant dissatisfaction over time—a gap well documented in prior studies [

51,

52].

These findings directly address the original research questions posed in the introductory chapter. Certification systems are not functionally equivalent, and each prioritizes a different axis of sustainability. Their limitations, particularly in POE, SDG traceability, and social governance undermine efforts toward comprehensive, measurable sustainability transitions in the built environment. Given these results, several recommendations are proposed:

Projects should consider pursuing combined certifications (e.g., LEED + WELL or BREEAM + WELL) to leverage the strengths of both environmental performance and user-centered metrics. This hybridization strategy ensures greater TBL coverage without duplicative effort.

- 2.

Mandatory Post-Occupancy Evaluation

POE should become a structural requirement, not elective credit. Longitudinal data—collected through environmental sensors, occupant surveys, and real-time feedback—are essential to align operational outcomes with design intent [

53].

- 3.

SDG-Based Credit Structuring

Certification bodies should integrate SDG mapping directly into credit systems. Projects could then report their SDG contributions through standardized, verifiable indicators that would enhance both policy transparency and stakeholder accountability [

54].

- 4.

Regional Contextualization

Building on BREEAM’s localized weightings, certification schemes should allow regional climate, policy, and cultural differences to inform credit valuation. A Mediterranean office should not be evaluated with the same criteria as a Scandinavian school [

55].

- 5.

Feedback-Driven Recertification

Systems should adopt a cyclical recertification model that is contingent upon performance metrics, not time alone. Smart technology now enables this possibility on a scale and would allow more adaptive, responsive sustainability governance [

56].

The implications of these recommendations extend to design teams, certifying bodies, policy-makers, and occupants themselves. Buildings are no longer static infrastructure but living systems that mediate environmental, social, and economic feedback. As such, their certification should reflect this dynamism in structure, logic, and methodology.

The data support the original research questions: certification systems vary significantly in focus, overlap partially with SDGs, and are often siloed in disciplinary scope. Their current design limits cross-pillar integration. For example, WELL achieves high satisfaction rates in thermal and visual comfort, but does not impose strong requirements on embodied carbon or lifecycle durability. Conversely, LEED may deliver superior resource efficiency without systematically assessing user comfort over time.

Ultimately, the results underscore the need for a systemic redesign of certification logic. Cross-system interoperability, dynamic POE requirements, and SDG-traceable credit structures are necessary to support comprehensive sustainability outcomes in the built environment.

5. Conclusions

This study presents a comprehensive comparative assessment of three dominant green building certification systems—LEED, BREEAM, and WELL—evaluating their structure, sustainability depth, health-centered features, and real-world performance outcomes. Building upon a triangulated benchmarking framework developed in the research, the analysis integrates key criteria across energy performance, indoor environmental quality (IEQ), lifecycle assessment (LCA), human well-being, and alignment with the Sustainable Development Goals (SDGs). The benchmarking model revealed that:

LEED offers broad international applicability with strong energy modeling protocols. However, it remains partially prescriptive and underperforms in adaptive post-occupancy feedback systems [

57,

58].

BREEAM is robust in lifecycle criteria and biodiversity integration, aligning closely with EU environmental policies. Nevertheless, its documentation-intensive nature and region-specific tools reduce its adoption in global markets [

59].

WELL excels in occupant health, biophilic design, and active sensing strategies, yet its disconnection from carbon metrics and energy efficiency standards limits its comprehensive sustainability scope [

60,

61].

Across all certifications, the lack of longitudinal post-occupancy evaluation (POE) remains a recurring performance gap, affecting reliability in real-world impact assessments [

62].

Table 7 summarizes the systems' performance across five critical axes as a final Benchmarking Summary:

To address the identified limitations and elevate certification frameworks to a new level of evidence-based impact, the following recommendations are proposed:

Embed Post-Occupancy Evaluation (POE) in certification renewal cycles to ensure dynamic verification of occupant outcomes [

63].

Bridge the Energy–Health Divide by integrating WELL’s real-time feedback sensors into LEED/BREEAM operational workflows [

64].

Foster Open Data Benchmarking, encouraging data sharing to create global reference models for carbon, comfort, and well-being [

65].

Advance SDG Traceability by explicitly linking certification points to SDG indicators (e.g., SDG 3, 7, 11, 13) and sub-goals [

66].

The research identifies several key directions for future academic and industry exploration. First, longitudinal studies are essential to track how certified buildings perform over time in energy consumption, IEQ, and occupant health, addressing gaps in post-certification accountability [

67,

68]. Second, applying machine learning to POE data could reveal latent correlations between design intentions and real outcomes through telemetry and occupant feedback systems [

69]. Third, comparative policy analysis is needed to assess how local regulations—such as India’s ECBC and the UK Future Homes Standard—support or conflict with international certification schemes [

70,

71]. Finally, adapting rating systems to the Global South is a critical avenue for equitable decarbonization, requiring flexible tools that acknowledge economic and climatic disparities [

72,

73].

Sustainability certification systems have evolved from prescriptive checklists into strategic tools of global urban governance, but their success hinges on deeper integration of data, accountability, and long-term social equity. This study urges a transformation toward science-based benchmarking, human-centric metrics, and deeper alignment with the global SDG framework to ensure certifications do not only promise sustainability—but deliver it.

Ethics Statement

This research did not involve human participants, animals, or personal data and does not require ethical approval. The authors declare no conflicts of interest.

References

- Sbci, U.N.E.P. , 2009. Buildings and climate change: Summary for decision-makers. United Nations Environmental Programme, Sustainable Buildings and Climate Initiative, Paris, 1, p.62.

- Zhang, T.; Gu, J.; Ardakanian, O.; Kim, J. Addressing data inadequacy challenges in personal comfort models by combining pretrained comfort models. Energy Build. 2022, 264. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Yeom, S.; An, J.; Hong, T.; Kim, S. Determining the optimal visible light transmittance of semi-transparent photovoltaic considering energy performance and occupants’ satisfaction. Build. Environ. 2023, 231. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Doan, D.T.; Naismith, N.; Zhang, T.; Ghaffarianhoseini, A.; Tookey, J. A critical comparison of green building rating systems. Build. Environ. 2017, 123, 243–260. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Ildiri, N.; Bazille, H.; Lou, Y.; Hinkelman, K.; Gray, W.A.; Zuo, W. Impact of WELL certification on occupant satisfaction and perceived health, well-being, and productivity: A multi-office pre- versus post-occupancy evaluation. Build. Environ. 2022, 224. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Reeder, L. , 2016. Net zero energy buildings: case studies and lessons learned. Routledge.

- Newsham, G.R.; Mancini, S.; Birt, B.J. Do LEED-certified buildings save energy? Yes, but… Energy Build. 2009, 41, 897–905. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Rebelatto, B.G.; Salvia, A.L.; Brandli, L.L.; Filho, W.L. Examining Energy Efficiency Practices in Office Buildings through the Lens of LEED, BREEAM, and DGNB Certifications. Sustainability 2024, 16, 4345. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Mirvac. EY Centre: WELL Gold Certification Case Study; Mirvac Group: Sydney, Australia, 2021; Available online: https://www.mirvac.com (accessed on 15 June 2025).

- Delos. Delos Headquarters WELL Certification Summary; Delos Living LLC: New York, USA, 2023; Available online: https://www.delos.com (accessed on 15 June 2025).

- Awadh, O. Sustainability and green building rating systems: LEED, BREEAM, GSAS and Estidama critical analysis. J. Build. Eng. 2017, 11, 25–29. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Roderick, Y. , McEwan, D., Wheatley, C. and Alonso, C., 2009, July. Comparison of energy performance assessment between LEED, BREEAM and Green Star. In Building Simulation 2009 (Vol. 11, pp. 1167-1176). IBPSA. [CrossRef]

- Ferreira, A.; Pinheiro, M.D.; de Brito, J.; Mateus, R. A critical analysis of LEED, BREEAM and DGNB as sustainability assessment methods for retail buildings. J. Build. Eng. 2023, 66. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Goubran, S.; Walker, T.; Cucuzzella, C.; Schwartz, T. Green building standards and the United Nations’ Sustainable Development Goals. J. Environ. Manag. 2022, 326, 116552. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- United Nations. Transforming Our World: The 2030 Agenda for Sustainable Development; UN: New York, NY, USA, 2015. [Google Scholar]

- U. S. Green Building Council (USGBC). LEED v4.1 Building Design and Construction Guide; USGBC: Washington, DC, USA, 2021. [Google Scholar]

- Building Research Establishment (BRE). BREEAM International New Construction Technical Manual 2021; BRE Group: Watford, UK, 2021. [Google Scholar]

- International WELL Building Institute. WELL Building Standard v2 Pilot; IWBI: New York, NY, USA, 2022. [Google Scholar]

- Andersson, D. and Sterner, E., 2023. An exploration of the economic impact and project process influence of BREEAM certification on commercial properties.

- Olubunmi, O.A.; Xia, P.B.; Skitmore, M. Green building incentives: A review. Renew. Sustain. Energy Rev. 2016, 59, 1611–1621. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Kent, M.G.; Parkinson, T.; Schiavon, S. Indoor environmental quality in WELL-certified and LEED-certified buildings. Sci. Rep. 2024, 14, 1–7. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Designing a natural ventilation strategy for Bloomberg’s central London HQ 2017, Cibse Journal, Available online: https://www.cibsejournal.

- Katafygiotou, M.; Protopapas, P.; Dimopoulos, T. How Sustainable Design and Awareness May Affect the Real Estate Market. Sustainability 2023, 15, 16425. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Cole, R.J.; Valdebenito, M.J. The importation of building environmental certification systems: international usages of BREEAM and LEED. Build. Res. Inf. 2013, 41, 662–676. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Saleh, N.M.; Saleh, A.M.; Hasan, R.A.; Keighobadi, J.; Ahmed, O.K.; Hamad, Z.K. Analyzing and Comparing Global Sustainability Standards: LEED, BREEAM, and PBRS in Green Building arch article topic. Babylon. J. Internet Things 2024, 2024, 70–78. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Suzer, O. Analyzing the compliance and correlation of LEED and BREEAM by conducting a criteria-based comparative analysis and evaluating dual-certified projects. Build. Environ. 2019, 147, 158–170. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Cidell, J. Building Green: The Emerging Geography of LEED-Certified Buildings and Professionals. Prof. Geogr. 2009, 61, 200–215. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Wu, P.; Song, Y.; Shou, W.; Chi, H.; Chong, H.-Y.; Sutrisna, M. A comprehensive analysis of the credits obtained by LEED 2009 certified green buildings. Renew. Sustain. Energy Rev. 2017, 68, 370–379. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Wong, D.H.; Zhang, C.; Di Maio, F.; Hu, M. Potential of BREEAM-C to support building circularity assessment: Insights from case study and expert interview. J. Clean. Prod. 2024, 442. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Allen, J.G. , MacNaughton, P., Laurent, J.G.C., Flanigan, S.S., Eitland, E.S. and Spengler, J.D., 2015. Green buildings and health. Current environmental health reports, 2, pp.250-258.

- Scheuer, C.W. and Keoleian, G.A., 2002. Evaluation of LEED using life cycle assessment methods. Gaithersburg, MD, USA: National Institute of Standards and Technology.

- Diestelmeier, L. and Cappelli, V., 2023. Conceptualizing ‘Energy Sharing’as an Activity of ‘Energy Communities’ under EU Law: Towards Social Benefits for Consumers?. Journal of European Consumer and Market Law, 12(1).

- Condezo-Solano, M.J.; Erazo-Rondinel, A.; Barrozo-Bojorquez, L.M.; Rivera-Nalvarte, C.C.; Giménez, Z. Global Analysis of WELL Certification: Influence, Types of Spaces and Level Achieved. Buildings 2025, 15, 1321. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Biswas, T.; Wang, T.-H.; Krishnamurti, R. FROM DESIGN TO PRE-CERTIFICATION USING BUILDING INFORMATION MODELING. J. Green Build. 2013, 8, 151–176. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Pena, R. , 2014. Living Proof: Seattle’s Net Zero Energy Bullitt Center. University of Washington, Department of Architecture, 6.

- Mondor, C.; Hockley, S.; Deal, D. THE DAVID LAWRENCE CONVENTION CENTER: HOW GREEN BUILDING DESIGN AND OPERATIONS CAN SAVE MONEY, DRIVE LOCAL ECONOMIC OPPORTUNITY, AND TRANSFORM AN INDUSTRY. J. Green Build. 2013, 8, 28–43. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Zimring, C.M.; Reizenstein, J.E. Post-Occupancy Evaluation. Environ. Behav. 1980, 12, 429–450. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Pitì, A.; Verticale, G.; Rottondi, C.; Capone, A.; Schiavo, L.L. The Role of Smart Meters in Enabling Real-Time Energy Services for Households: The Italian Case. Energies 2017, 10, 199. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Ma, K.; Hu, G.; Spanos, C.J. Distributed Energy Consumption Control via Real-Time Pricing Feedback in Smart Grid. IEEE Trans. Control. Syst. Technol. 2014, 22, 1907–1914. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Alahmad, M.A.; Wheeler, P.G.; Schwer, A.; Eiden, J.; Brumbaugh, A. A Comparative Study of Three Feedback Devices for Residential Real-Time Energy Monitoring. IEEE Trans. Ind. Electron. 2011, 59, 2002–2013. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Pawar, J.P. ; S., A.; S., A.; B., S.K. Real time energy measurement using smart meter. 2016 Online International Conference on Green Engineering and Technologies (IC-GET). LOCATION OF CONFERENCE, IndiaDATE OF CONFERENCE; pp. 1–5.

- Lawrence, R.J. , 2005. Building healthy cities: the World Health Organization perspective. In Handbook of Urban health: Populations, methods, and practice (pp. 479-501). Boston, MA: Springer US.

- Kouka, D.; Cardinali, G.D.; Messina, G.; Barreca, F. BIM-based post-occupancy analysis of energy use and carbon impact in adaptive reused buildings: A case study of an olive mill in Southern Italy. Results Eng. 2025, 26. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Pastore, L.; Andersen, M. Building energy certification versus user satisfaction with the indoor environment: Findings from a multi-site post-occupancy evaluation (POE) in Switzerland. Build. Environ. 2019, 150, 60–74. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Becerik-Gerber, B.; Lucas, G.; Aryal, A.; Awada, M.; Bergés, M.; Billington, S.; Boric-Lubecke, O.; Ghahramani, A.; Heydarian, A.; Höelscher, C.; et al. The field of human building interaction for convergent research and innovation for intelligent built environments. Sci. Rep. 2022, 12, 1–19. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Katafygiotou, M.; Serghides, D. Indoor comfort and energy performance of buildings in relation to occupants' satisfaction: investigation in secondary schools of Cyprus. Adv. Build. Energy Res. 2013, 8, 216–240. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Moktar, A.E. , 2012. Comparative study of building environmental assessment systems: Pearl Rating System, LEED and BREEAM a case study building in Abu Dhabi, United Arab Emirates (Doctoral dissertation, The British University in Dubai (BUiD)).

- Lee, W. A comprehensive review of metrics of building environmental assessment schemes. Energy Build. 2013, 62, 403–413. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Altomonte, S.; Schiavon, S. Occupant satisfaction in LEED and non-LEED certified buildings. Build. Environ. 2013, 68, 66–76. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Colton, M.D.; MacNaughton, P.; Vallarino, J.; Kane, J.; Bennett-Fripp, M.; Spengler, J.D.; Adamkiewicz, G. Indoor Air Quality in Green Vs Conventional Multifamily Low-Income Housing. Environ. Sci. Technol. 2014, 48, 7833–7841. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Janda, K.B. Buildings don't use energy: people do. Arch. Sci. Rev. 2011, 54, 15–22. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Isaac, S.; Meir, I.; Pignatta, G. Net-Zero and Positive Energy Communities; Taylor & Francis: London, United Kingdom, 2023. [Google Scholar]

- Park, J.Y. , 2020. Occupant-centric building control: balancing occupant comfort and energy efficiency (Doctoral dissertation).

- United Nations. Transforming Our World: The 2030 Agenda for Sustainable Development. UN General Assembly, 2015.

- Barbu, A.D. , Griffiths, N. and Morton, G., 2013. Achieving energy efficiency through behaviour change: what does it take?

- Gana, V.; Giridharan, R.; Watkins, R. Application of Soft Landings in the Design Management process of a non-residential building. Arch. Eng. Des. Manag. 2017, 14, 178–193. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Lee, W. Benchmarking energy use of building environmental assessment schemes. Energy Build. 2012, 45, 326–334. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Doan, D.T.; Van Tran, H.; Aigwi, I.E.; Naismith, N.; Ghaffarianhoseini, A. Green building rating systems: A critical comparison between LOTUS, LEED, and Green Mark. Environ. Res. Commun. 2023, 5, 075008. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Mirzaie, S. , 2022. Influence of BREEAM, BIM, and Soft Landings on lifecycle performance of two non-domestic buildings (Doctoral dissertation, Heriot-Watt University).

- Darwish, B.H. , Rasmy, W.M. and Ghaly, M., 2022. Applying “well building standards” in interior design of administrative buildings. Journal of Arts & Architecture Research Studies, 3(5), pp.67-83.

- Licina, D.; Langer, S. Indoor air quality investigation before and after relocation to WELL-certified office buildings. Build. Environ. 2021, 204. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Elsayed, M.; Pelsmakers, S.; Pistore, L.; Castaño-Rosa, R.; Romagnoni, P. Post-occupancy evaluation in residential buildings: A systematic literature review of current practices in the EU. Build. Environ. 2023, 236. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Liang, H.-H.; Chen, C.-P.; Hwang, R.-L.; Shih, W.-M.; Lo, S.-C.; Liao, H.-Y. Satisfaction of occupants toward indoor environment quality of certified green office buildings in Taiwan. Build. Environ. 2014, 72, 232–242. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Mahdavi, A.; Berger, C. Predicting Buildings' Energy Use: Is the Occupant-Centric “Performance Gap” Research Program Ill-Advised? Front. Energy Res. 2019, 7. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Roth, J.; Lim, B.; Jain, R.K.; Grueneich, D. Examining the feasibility of using open data to benchmark building energy usage in cities: A data science and policy perspective. Energy Policy 2020, 139. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Guterres, A. , 2020. The sustainable development goals report 2020. United Nations publication issued by the Department of Economic and Social Affairs, pp.1-64.

- Haaskjold, H.; Langlo, J.A. Results from a ten-year longitudinal study of Norwegian construction industry performance. Int. J. Manag. Proj. Bus. 2025. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Rice, L.; Drane, M. Indicators of Healthy Architecture—a Systematic Literature Review. J. Urban Heal. 2020, 97, 899–911. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Patlakas, P. , 2022. Techniques for the utilisation and management of Post Occupancy Evaluation data by non-experts (Doctoral dissertation, Birmingham City University).

- Bureau of Energy Efficiency (2017). Energy Conservation Building Code (ECBC). Ministry of Power, Government of India.

- HM Government (2021). The Future Homes Standard: Consultation on Changes to Part L and Part F. UK Ministry of Housing.

- Cease, B.; Kim, H.; Kim, D.; Ko, Y.; Cappel, C. Barriers and incentives for sustainable urban development: An analysis of the adoption of LEED-ND projects. J. Environ. Manag. 2019, 244, 304–312. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Wong, I.L.; Krüger, E. Comparing energy efficiency labelling systems in the EU and Brazil: Implications, challenges, barriers and opportunities. Energy Policy 2017, 109, 310–323. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

|

Disclaimer/Publisher’s Note: The statements, opinions and data contained in all publications are solely those of the individual author(s) and contributor(s) and not of MDPI and/or the editor(s). MDPI and/or the editor(s) disclaim responsibility for any injury to people or property resulting from any ideas, methods, instructions or products referred to in the content. |

© 2025 by the authors. Licensee MDPI, Basel, Switzerland. This article is an open access article distributed under the terms and conditions of the Creative Commons Attribution (CC BY) license (http://creativecommons.org/licenses/by/4.0/).