Submitted:

14 May 2025

Posted:

15 May 2025

You are already at the latest version

Abstract

Keywords:

1. Introduction

2. Materials and Methods

2.1. Pilot–Developing the DEEP CTN Scale

2.1.1. Phase 1: Item Creation

2.1.2. Phase 2: Pilot Exploratory Factor Analysis

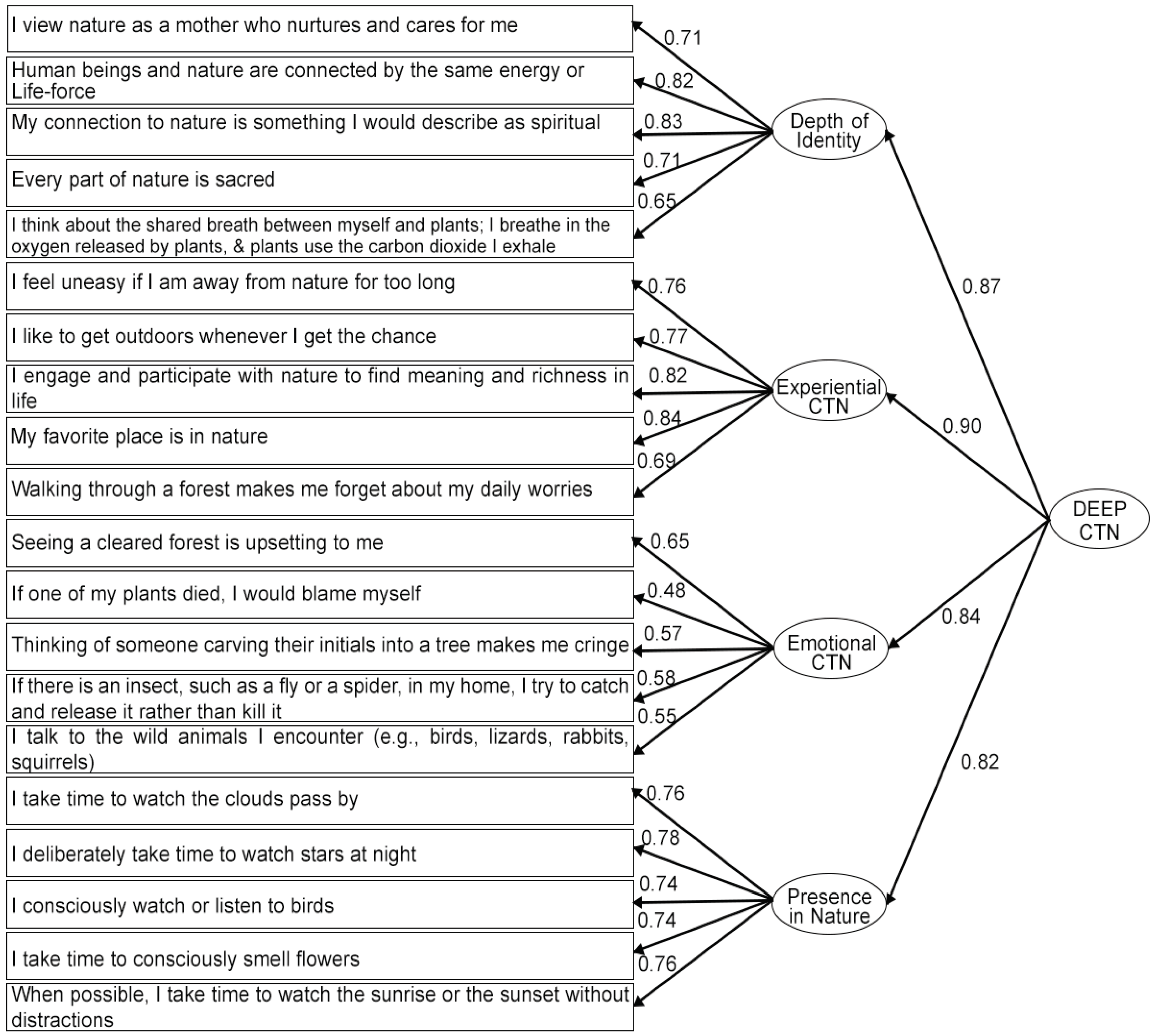

- Depth of identity (deeply seeing the self as part of nature, which represents the cognitive component of CTN)

- Emotional connection (emotional desire to connect with and care for nature, which represents an emotional component of CTN)

- Experiential connection (spending and enjoying time in nature, which represents one aspect of the behavioral component of CTN)

- Presence within nature (engaging mindfully and consciously with nature, which represents a second aspect of the behavioral component of CTN)

2.1.3. Phase 3: Pilot Confirmatory Factor Analysis

2.2. Pre-Registered CFA and Validation

2.2.1. Power Analysis

2.2.2. Participants

2.2.3. Materials & Procedure

2.2.4 Data Analysis

3. Results

3.1. CFA Analysis

3.2. Further Validation Analyses

3.2.1. Convergent Validity

3.2.2. Predictive Validity

3.2.3. Incremental Validity

4. Discussion

4.1. Dimensionality

4.2. Predicting Pro-Environmental Behavior

4.3. Predicting Well-Being

4.4. Limitations

5. Future Directions and Conclusion

Supplementary Materials

Author Contributions

Funding

Institutional Review Board Statement

Informed Consent Statement

Data Availability Statement

Conflicts of Interest

Abbreviations

| CTN | Connection to nature |

| PEB | Pro-environmental Behavior |

| HNR | Human-nature relations |

| WB | Well-being |

| DEEP | Depth of identity, emotional connection, experiential connection, presence in nature CTN scale |

| NR | Nature relatedness scale [30] |

| EID | Environmental identity scale [31] |

| CNS | Connectedness with nature scale [14] |

| AIMES | Attachment, identity, materialism, experiential, spiritual CTN scale [28] |

| CN-12 | Connection with Nature 12 item scale [27] |

| RPEBs | Recurring pro-environmental behavior scale [51] |

| EFA | Exploratory factor analysis |

| CFA | Confirmatory factor analysis |

| RMSEA | Root mean square error |

| RMSR | Standardized root mean square residual |

| CFI | Comparative fit index |

| TLI | Tucker Lewis index |

| AIC | Akaike information criterion |

| 1 | The HNR framework identifies five ways in which humans can relate to nature ranging from shallow to deep connections, with the deeper connections being proposed as the most likely to lead to both individual and systemic change in pro-environmental behavior. Three of these five are able to be directly mapped onto the three CTN dimensions: Cognitive (attitudes and values), Emotional (various emotions relating to nature), and Behavioral (engaging in activities within nature), as these operate almost exclusively at the individual level. While two are more appropriately viewed as human-nature worldviews given they operate at a more societal level: Material (using nature to extract value for humans), and Philosophical (beliefs of what nature is in relation to humans). |

| 2 | This consists of a multiple-choice question asking participants to report their experience answering questions during the study. Participants can respond: 1) I read all instructions and questions carefully, and answered honestly to the best of my ability; 2) I went through this survey quickly, and may have missed a few instructions or skimmed questions, but I still answered honestly; 3) I read most of the instructions and questions, but I clicked some answers without fully reading them; or 4) I tried to finish this as quickly as possible and did not read most of the questions or instructions, or I did not answer honestly. Only participants who respond 1 or 2 are retained as attentive and honest participants. Participants are told that their responses to this question is completely anonymous and will not in any way affect their Prolific payment, but is used to improve the validity of data included in our analyses. |

| 3 | While the Cronbach’s alpha within this sample was low, the alpha in the original paper was 0.87 [52] and 0.73 in our pilot study |

| 4 | Political Ideology was scored on a 7-point Likert scale with 1 = Most Liberal and 7 = Most Conservative The mean political ideology was 3.11(1.7). There was a skew towards more liberal ideologies. |

References

- IPCC, 2022: Summary for Policymakers. In Climate Change 2022: Mitigation of Climate Change. Contribution of Working Group III to the Sixth Assessment Report of the Intergovernmental Panel on Climate Change; Shukla, P.R., Skea, J., Reisinger, A., Slade, R., Fradera, R., Pathak, M., Al Khourdajie, A., Belkacemi, M., van Diemen, R., Hasija, A., Lisboa, S., Luz, S., Malley, D., McCollum, D., Some, S., Vyas, P., Eds.; Cambridge University Press: Cambridge, UK and New York, NY, USA, 2022.

- Ceballos, G.; Ehrlich, P.R.; Raven, P.H. Vertebrates on the Brink as Indicators of Biological Annihilation and the Sixth Mass Extinction. Proceedings of the National Academy of Sciences 2020, 117, 13596–13602. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Zylstra, M.J.; Knight, A.T.; Esler, K.J.; Le Grange, L.L.L. Connectedness as a Core Conservation Concern: An Interdisciplinary Review of Theory and a Call for Practice. Springer Science Reviews 2014, 2, 119–143. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Virgen-Urcelay, A.; Donner, S.D. Increase in the Extent of Mass Coral Bleaching over the Past Half-Century, Based on an Updated Global Database. PLOS ONE 2023, 18, e0281719. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Louv, R. Last Child in the Woods: Saving Our Children from Nature-Deficit Disorder; Algonquin Books, 2005;

- Soga, M.; Gaston, K.; Yamaura, Y.; Kurisu, K.; Hanaki, K. Both Direct and Vicarious Experiences of Nature Affect Children’s Willingness to Conserve Biodiversity. IJERPH 2016, 13, 529. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Kesebir, S.; Kesebir, P. A Growing Disconnection From Nature Is Evident in Cultural Products. Perspect Psychol Sci 2017, 12, 258–269. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Soga, M.; Gaston, K.J. Do People Who Experience More Nature Act More to Protect It? A Meta-Analysis. Biological Conservation 2024, 289, 110417. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Mayer, F.S.; Frantz, C.M.; Bruehlman-Senecal, E.; Dolliver, K. Why Is Nature Beneficial? : The Role of Connectedness to Nature. Environment and Behavior 2009, 41, 607–643. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Barragan-Jason, G.; de Mazancourt, C.; Parmesan, C.; Singer, M.C.; Loreau, M. Human–Nature Connectedness as a Pathway to Sustainability: A Global Meta-analysis. CONSERVATION LETTERS 2021, 15. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Clayton, S.; Czellar, S.; Nartova-Bochaver, S.; Skibins, J.C.; Salazar, G.; Tseng, Y.-C.; Irkhin, B.; Monge-Rodriguez, F.S. Cross-Cultural Validation of A Revised Environmental Identity Scale. Sustainability 2021, 13, 2387. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Dutcher, D.D.; Finley, J.C.; Luloff, A.E.; Johnson, J.B. Connectivity with Nature as a Measure of Environmental Values. Environment and Behavior 2007, 39, 474–493. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Kurth, A.M.; Narvaez, D.; Kohn, R.; Bae, A. Indigenous Nature Connection: A 3-Week Intervention Increased Ecological Attachment. Ecopsychology 2020, 12, 101–117. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Mayer, F.S.; Frantz, C.M. The Connectedness to Nature Scale: A Measure of Individuals’ Feeling in Community with Nature. Journal of Environmental Psychology 2004, 24, 503–515. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Nisbet, E.K.; Zelenski, J.M. The NR-6: A New Brief Measure of Nature Relatedness. Front. Psychol. 2013, 4. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Schultz, W., P. The Structure of Environmental Concern: Concern for Self, Other People, and the Biosphere. Journal of Environmental Psychology 2001, 21, 327–339. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Leopold, A. The Land Ethic. In A Sand County Almanac; Oxford University Press, 1949; pp. 201–226.

- Naess, A. The Shallow and the Deep, Long-Range Ecology Movement. A Summary. Inquiry 1973, 95–100. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Theodore, R. The Voice of the Earth: An Exploration of Ecopsychology; Simon & Schuster: New York, 1992.

- Kurle, C.M.; Cadotte, M.W.; Seo, M.; Dooner, P.; Jones, H.P. Considering Humans as Integral Comonents of “Nature.” Ecological Solutions and Evidence 2023, 4, e12220. [CrossRef]

- Tiscareno-Osorno, X.; Demetriou, Y.; Marques, A.; Peralta, M.; Jorge, R.; MacIntyre, T.E.; MacIntyre, D.; Smith, S.; Sheffield, D.; Jones, M.V.; et al. Systematic Review of Explicit Instruments Measuring Nature Connectedness: What Do We Know and What Is Next? Environment and Behavior 2023, 00139165231212321. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Perrin, J.L.; Benassi, V.A. The Connectedness to Nature Scale: A Measure of Emotional Connection to Nature? Journal of Environmental Psychology 2009, 29, 434–440. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Kals, E.; Schumacher, D.; Montada, L. Emotional Affinity toward Nature as a Motivational Basis to Protect Nature. Environment and Behavior 1999, 31, 178–202. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Dong, X.; Liu, S.; Li, H.; Yang, Z.; Liang, S.; Deng, N. Love of Nature as a Mediator between Connectedness to Nature and Sustainable Consumption Behavior. Journal of Cleaner Production 2020, 242, 118451. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Tam, K.-P. Concepts and Measures Related to Connection to Nature: Similarities and Differences. Journal of Environmental Psychology 2013, 34, 64–78. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Balundė, A.; Jovarauskaitė, L.; Poškus, M.S. Exploring the Relationship Between Connectedness With Nature, Environmental Identity, and Environmental Self-Identity: A Systematic Review and Meta-Analysis. SAGE Open 2019, 9, 215824401984192. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Hatty, M.A.; Graham Smith, L.D.; Goodwin, D.; Tinoziva Mavondo, F. The CN-12: A Brief, Multidimensional Connection with Nature Instrument. Frontiers in Psychology 2020, 11. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Meis-Harris, J.; Borg, K.; Jorgensen, B.S. The Construct Validity of the Multidimensional AIMES Connection to Nature Scale: Measuring Human Relationships with Nature. Journal of Environmental Management 2021, 280. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Whitburn, J.; Linklater, W.; Abrahamse, W. Meta-analysis of Human Connection to Nature and Proenvironmental Behavior. Conservation Biology 2020, 34, 180–193. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Nisbet, E.K.; Zelenski, J.M.; Murphy, S.A. The Nature Relatedness Scale: Linking Individuals’ Connection with Nature to Environmental Concern and Behavior. Environment and Behavior 2009, 41, 715–740. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Clayton, S. Environmental Identity: A Conceptual and an Operational Definition. In Identity and the natural environment: The psychological significance of nature; MIT Press, 2003; pp. 45–65.

- Olivos, P.; Aragonés, J.-I. Psychometric Properties of the Environmental Identity Scale (EID). Psyecology 2011, 2, 65–74. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Schwartz, S.H. Universals in the Content and Structure of Values: Theoretical Advances and Empirical Tests in 20 Countries. In Advances in Experimental Social Psychology; Elsevier, 1992; Vol. 25, pp. 1–65 ISBN 978-0-12-015225-4.

- Schwartz, S.H. A Theory of Cultural Values and Some Implications for Work. Applied Psychology 1999, 48, 23–47. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Stern, P.C.; Dietz, T. The Value Basis of Environmental Concern. Journal of Social Issues 1994, 50, 65–84. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Chew, P.K.H. Psychometric Evaluation of Two Instruments to Assess Connection to Nature / Evaluación Psicométrica de Dos Instrumentos Que Miden La Conexión Con La Naturaleza. PsyEcology 2019, 10, 313–343. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Ives, C.D.; Abson, D.J.; von Wehrden, H.; Dorninger, C.; Klaniecki, K.; Fischer, J. Reconnecting with Nature for Sustainability. Sustain Sci 2018, 13, 1389–1397. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Meis-Harris, J.; Saeri, A.; Boulet, M.; Borg, K.; Faulkner, N.; Jorgensen, B. Victorians Value Nature – Survey Results; BehaviourWorks Australia, Monash University: Melbourne, Australia, 2019.

- Sellbom, M.; Tellegen, A. Factor Analysis in Psychological Assessment Research: Common Pitfalls and Recommendations. Psychological Assessment 2019, 31, 1428–1441. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Rosellini, A.J.; Brown, T.A. Developing and Validating Clinical Questionnaires. Annu. Rev. Clin. Psychol. 2021, 17, 55–81. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Mackay, C.M.L.; Schmitt, M.T. Do People Who Feel Connected to Nature Do More to Protect It? A Meta-Analysis. Journal of Environmental Psychology 2019, 65, 101323. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Vesely, S.; Masson, T.; Chokrai, P.; Becker, A.M.; Fritsche, I.; Klöckner, C.A.; Tiberio, L.; Carrus, G.; Panno, A. Climate Change Action as a Project of Identity: Eight Meta-Analyses. Global Environmental Change 2021, 70, 102322. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Nathans, L.L.; Oswald, F.L.; Nimon, K. Interpreting Multiple Linear Regression: A Guidebook of Variable Importance. Practical Assessment, Research, and Evaluation 2012, 17. [CrossRef]

- Tonidandel, S.; LeBreton, J.M. Relative Importance Analysis: A Useful Supplement to Regression Analysis. J Bus Psychol 2011, 26, 1–9. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Capaldi, C.A.; Dopko, R.L.; Zelenski, J.M. The Relationship between Nature Connectedness and Happiness: A Meta-Analysis. Front Psychol 2014, 5. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Kasap, E.Z.; Ağzıtemiz, F.; Ünal, G. Cognitive, Mental and Social Benefits of Interacting with Nature: A Systematic Review. Journal of Happiness and Health 2021, 1, 16–27. [Google Scholar]

- Pritchard, A.; Richardson, M.; Sheffield, D.; McEwan, K. The Relationship between Nature Connectedness and Eudaimonic Well-Being: A Meta-Analysis. J Happiness Stud 2020, 21, 1145–1167. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Brügger, A.; Kaiser, F.G.; Roczen, N. One for All?: Connectedness to Nature, Inclusion of Nature, Environmental Identity, and Implicit Association with Nature. European Psychologist 2011, 16, 324–333. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Suganthi, L. Ecospirituality: A Scale to Measure an Individual’s Reverential Respect for the Environment. Ecopsychology 2019, 11, 110–122. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Pett, M.; Lackey, N.; Sullivan, J. Making Sense of Factor Analysis; SAGE Publications, Inc.: 2455 Teller Road, Thousand Oaks California 91320 United States of America, 2003; ISBN 978-0-7619-1950-6. ISBN 978-0-7619-1950-6.

- Brick, C.; Sherman, D.K.; Kim, H.S. “Green to Be Seen” and “Brown to Keep down”: Visibility Moderates the Effect of Identity on pro-Environmental Behavior. Journal of Environmental Psychology 2017, 51, 226–238. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Clifton, J.D.W.; Baker, J.D.; Park, C.L.; Yaden, D.B.; Clifton, A.B.W.; Terni, P.; Miller, J.L.; Zeng, G.; Giorgi, S.; Schwartz, H.A.; et al. Primal World Beliefs. Psychological Assessment 2019, 31, 82–99. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Ryff, C.D.; Keyes, C.L.M. The Structure of Psychological Well-Being Revisited. Journal of Personality and Social Psychology 1995, 69, 719–727. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Watson, D.; Anna, L.; Tellegen, A. Development and Validation of Brief Measures of Positive and Negative Affect: The PANAS Scales. Journal of Personality and Social Psychology 1988, 54, 1063–1070. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Ryan, R.M.; Frederick, C. On Energy, Personality, and Health: Subjective Vitality as a Dynamic Reflection of Well-Being. Journal of Personality 1997, 65, 529–565. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Gifford, R. Environmental Psychology Matters. Annu. Rev. Psychol. 2014, 65, 541–579. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Adler, N.; Epel, E.S.; Catellazzo, G.; Ickovics, J.R. Relationship of Subjective and Objective Social Status with Psychological and Physiological Functioning: Preliminary Data in Healthy White Women. Health Psychology 2000, 19, 586–592. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Hair, J.F.; Hult, G.T.M.; Ringle, C.M.; Sarstedt, M. A Primer on Partial Least Squares Structural Equation Modeling (PLS-SEM); 3rd ed.; Sage, 2017.

- Mardia, K.V. Measures of Multivariate Skewness and Kurtosis with Applications. Biometrika 1970, 57, 519–530. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Li, C.-H. Confirmatory Factor Analysis with Ordinal Data: Comparing Robust Maximum Likelihood and Diagonally Weighted Least Squares. Behav Res 2016, 48, 936–949. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Garson, G.D. Assumptions and Limitations of Factor Analysis. In FActor Analysis and Dimension Reduction in R; Routledge, 2022; Vol. 1.

- Rosseel, Y. Lavaan: An R Package for Structural Equation Modeling. Journal of Statistical Software 2012.

- Hu, L.; Bentler, P.M. Cutoff Criteria for Fit Indexes in Covariance Structure Analysis: Conventional Criteria versus New Alternatives. Structural Equation Modeling: A Multidisciplinary Journal 1999, 6, 1–55. [CrossRef]

- Brown, T. Confirmatory Factor Analysis for Applied Research; 2nd ed.; The Guilford Press, 2015.

- Rickard, S.C.; White, M.P. Barefoot Walking, Nature Connectedness and Psychological Restoration: The Importance of Stimulating the Sense of Touch for Feeling Closer to the Natural World. Landscape Research 2021, 46, 975–991. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Nisbet, E.K.; Zelenski, J.M.; Grandpierre, Z. Mindfulness in Nature Enhances Connectedness and Mood. Ecopsychology 2019, 11, 81–91. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Passmore, H.-A.; Holder, M.D. Noticing Nature: Individual and Social Benefits of a Two-Week Intervention. The Journal of Positive Psychology 2017, 12, 537–546. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Richardson, M.; Hamlin, I.; Butler, C.W.; Thomas, R.; Hunt, A. Actively Noticing Nature (Not Just Time in Nature) Helps Promote Nature Connectedness. Ecopsychology 2022, 14, 8–16. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Doherty, T.J.; Clayton, S. The Psychological Impacts of Global Climate Change. American Psychologist 2011, 66, 265–276. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Albrecht, G.A. Negative Psychoterratic Emotions. In Earth Emotions; Cornell University Press, 2019.

- Clayton, S.; Karazsia, B.T. Development and Validation of a Measure of Climate Change Anxiety. Journal of Environmental Psychology 2020, 69, 101434. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Jalin, H.; Sapin, A.; Macherey, A.; Boudoukha, A.H.; Congard, A. Understanding Eco-Anxiety: Exploring Relationships with Environmental Trait Affects, Connectedness to Nature, Depression, Anxiety, and Media Exposure. Curr Psychol 2024, 43, 23455–23468. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Hughes, J.; Rogerson, M.; Barton, J.; Bragg, R. Age and Connection to Nature: When Is Engagement Critical? Frontiers in Ecology and the Environment 2019, 17, 265–269. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Reese, R.F.; Lewis, T.F.; Kothari, B.H. Nature Connection Changes throughout the Life Span: Generation and Sex-based Differences in Ecowellness. Adultspan Journal 2020, 19, 94–106. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Lindsay, D.; Wang, E. Analyzing Differences in the Definition of Nature.; Riverside, CA, 2023.

- Davis, J.L.; Le, B.; Coy, A.E. Building a Model of Commitment to the Natural Environment to Predict Ecological Behavior and Willingness to Sacrifice. Journal of Environmental Psychology 2011, 31, 257–265. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Reese, R.F.; Myers, J.E.; Lewis, T.F.; Willse, J.T. Construction and Initial Validation of the Reese EcoWellness Inventory. Int J Adv Counselling 2015, 37, 124–142. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

| Item | Dimension |

|---|---|

| I view nature as a mother who nurtures and cares for me | Depth of Identity |

| Human beings and nature are connected by the same energy or Life-force | Depth of Identity |

| My connection to nature is something I would describe as spiritual | Depth of Identity |

| Every part of nature is sacred | Depth of Identity |

| I think about the shared breath between myself and plants; I breathe in the oxygen released by plants, and plants use the carbon dioxide I exhale | Depth of Identity |

| Seeing a cleared forest is upsetting to me | Emotional Connection |

| If one of my plants died, I would blame myself | Emotional Connection |

| Thinking of someone carving their initials into a tree makes me cringe | Emotional Connection |

| If there is an insect, such as a fly or a spider, in my home, I try to catch and release it rather than kill it | Emotional Connection |

| I talk to the wild animals I encounter (e.g., birds, lizards, rabbits, squirrels) | Emotional Connection |

| I like to get outdoors whenever I get the chance | Experiential Connection |

| I feel uneasy if I am away from nature for too long | Experiential Connection |

| I engage and participate with nature to find meaning and richness in life | Experiential Connection |

| My favorite place is in nature | Experiential Connection |

| Walking through a forest makes me forget about my daily worries | Experiential Connection |

| I take time to watch the clouds pass by | Presence within Nature |

| I deliberately take time to watch stars at night | Presence within Nature |

| I consciously watch or listen to birds | Presence within Nature |

| I take time to consciously smell flowers | Presence within Nature |

| When possible, I take time to watch the sunrise or the sunset without distractions | Presence within Nature |

| Dimension | M (SD) | α | 1 | 2 | 3 | 4 |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| 1. Depth | 4.69 (1.46) | 0.86 | ||||

| 3. Emotional | 4.59 (1.34) | 0.70 | 0.54*** | |||

| 2. Experiential | 4.88 (1.44) | 0.88 | 0.70*** | 0.57*** | ||

| 4. Presence | 4.56 (1.37) | 0.87 | 0.61*** | 0.57*** | 0.58*** | |

| 5. Total | 4.68 (1.18) | 0.93 | 0.85*** | 0.80*** | 0.85*** | 0.81*** |

| Model | χ² (df) | RMSEA (95% CI) | RMSR | TLI | CFI | AIC |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| 1-factor | 676.43 (170) | 0.11 (0.1 - 0.12) | 0.07 | 0.78 | 0.80 | 22,833.50 |

| 4-factor hierarchical | 358.4 (164) | 0.07 (0.06 - 0.08) | 0.05 | 0.91 | 0.93 | 22,446.42 |

| 4-factor | 366.6 (166) | 0.07 (0.06 - 0.08) | 0.05 | 0.91 | 0.92 | 22,452.24 |

| Total Score | Deep | Experiential | Emotional | Presence | |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| CNS | 0.72*** | 0.75*** | 0.62*** | 0.50*** | 0.53*** |

| EIDR | 0.78*** | 0.63*** | 0.81*** | 0.58*** | 0.55*** |

| Total Score | Deep | Emotional | Experiential | Presence | |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| PEB | 0.53*** | 0.44*** | 0.45*** | 0.44*** | 0.46*** |

| WB | 0.39*** | 0.42*** | 0.17** | 0.34*** | 0.39*** |

| Predictive Validity | Incremental Validity | |||||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Variable | Partial R2 | p | std Beta (99% CI) | Partial R2 | p | std Beta (99% CI) |

| Deep | 0.07 | 0.05 | 0.14 (0 - 0.28) | 0.06 | 0.36 | 0.07 (-0.08 - 0.22) |

| Emotional | 0.08*** | 0.00 | 0.21 (0.08 - 0.34) | 0.08*** | 0.00 | 0.22 (0.1 - 0.35) |

| Experiential | 0.07 | 0.08 | 0.12 (-0.02 - 0.27) | 0.06 | 0.09 | 0.12 (-0.02 - 0.26) |

| Presence | 0.08** | 0.01 | 0.17 (0.04 - 0.31) | 0.07* | 0.04 | 0.14 (0.01 - 0.28) |

| Primal Worldviews | 0.04** | 0.01 | 0.14 (0.03 - 0.25) | |||

| Age | 0.01 | 0.17 | 0 (0 - 0.01) | |||

| Model R2 | 0.30 | 0.31 | ||||

| Predictive Validity | Incremental Validity | |||||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Variable | Partial R2 | p | std Beta (99% CI) | Partial R2 | p | std Beta (99% CI) |

| Deep | 0.09*** | 0.00 | 0.22 (0.1 - 0.34) | 0.06* | 0.04 | 0.13 (0 - 0.25) |

| Emotional | 0.02** | 0.01 | -0.15 (-0.26 - -0.04) | 0.01 | 0.07 | -0.1 (-0.2 - 0.01) |

| Experiential | 0.05 | 0.11 | 0.10 (-0.02 - 0.22) | 0.04 | 0.27 | 0.07 (-0.05 - 0.18) |

| Presence | 0.08*** | 0.00 | 0.23 (0.11 - 0.34) | 0.07*** | 0.00 | 0.19 (0.08 - 0.3) |

| Worldviews | 0.07*** | 0.00 | 0.18 (0.09 - 0.27) | |||

| Politics | 0.04*** | 0.00 | 0.14 (0.06 - 0.22) | |||

| Age | 0.02* | 0.04 | 0.01 (0 - 0.01) | |||

| Model R2 | 0.24 | 0.31 | ||||

Disclaimer/Publisher’s Note: The statements, opinions and data contained in all publications are solely those of the individual author(s) and contributor(s) and not of MDPI and/or the editor(s). MDPI and/or the editor(s) disclaim responsibility for any injury to people or property resulting from any ideas, methods, instructions or products referred to in the content. |

© 2025 by the authors. Licensee MDPI, Basel, Switzerland. This article is an open access article distributed under the terms and conditions of the Creative Commons Attribution (CC BY) license (http://creativecommons.org/licenses/by/4.0/).