1. Introduction

The study of psychological well-being has evolved from unidimensional approaches focused on subjective happiness toward comprehensive perspectives that consider multiple facets of human development [

1]. Carol Ryff’s model of psychological well-being, originally developed in Western contexts, has proven particularly relevant by incorporating both individual and relational aspects within its six-dimensional structure. Research such as that conducted by Díaz et al. [

2] has shown that these dimensión self, acceptance, positive relations, autonomy, environmental mastery, personal growth, and purpose in life require cultural adaptations to maintain ecological validity in Latin American contexts, particularly in collectivist societies where the constructs of autonomy and interpersonal relationships acquire nuances different from those originally described in the Anglo-Saxon literature.

This perspective is complemented by Keyes’ model of social well-being [

3], which expands the theoretical framework by incorporating five fundamental social dimensions: integration, acceptance, contribution, actualization, and social coherence. As Keyes [

4] notes, in cultures such as that of the Colombian Caribbean, where family and community networks play a central role, mental health is sustained by collective or group dynamics. Studies conducted in the Colombian Caribbean have shown that these social dimensions of well-being display stronger correlations with mental health indicators than purely individual aspects [

5]. This suggests that, in cultural contexts such as ours, theoretical models should prioritize the relational and community components of psychological well-being.

However, the complexity of these phenomena in our setting requires moving beyond traditional methodological approaches. While correlational analyses and multiple regression models [

6] have provided valuable evidence on linear relationships between variables, they are insufficient to capture the dynamic and relational nature of well-being in specific cultural contexts. In such cases, network analysis [

7] emerges as an alternative that can identify patterns of interconnection among variables beyond traditional methods. This approach is particularly relevant for studying how dimensions such as autonomy or positive relations are articulated in unique ways within collectivist cultures.

In this regard, methodological triangulation between these approaches becomes an important strategy for advancing the understanding of psychological well-being in such contexts. As Joshanloo et al. [

8] point out, the convergence of diverse methods not only increases the validity of findings but also makes it possible to capture the complexity of evolving psychosocial phenomena. In the Colombian Caribbean, where deeply rooted cultural traditions coexist with accelerated processes of urban modernization, this integrative approach is particularly pertinent. Previous studies in the region [

9] have identified unique patterns in the configuration of well-being that do not align with expectations derived from traditional theoretical models, reinforcing the need to adopt innovative methodological perspectives.

Moreover, recent research in cities such as Barranquilla and Cartagena [

10] has documented how the post-pandemic context, along with processes of internal migration and social mobility, is reshaping the determinants of psychological well-being and mental health. These changes generate tensions between traditional values of family interdependence and the new demands for individual autonomy inherent to urban environments. In this regard, Naberushkina et al. [

11] note that, from the perspective of young people, although they recognize the family as crucial in people’s lives, the traditional view of the family has been changing, with an emerging individualistic approach to family life that undermines its capacity to meet emotional needs for love, care, and personal support. Hence, they emphasize the need for policies that support the restoration of the family as a guarantor of the well-being of its members.

As Woodman & Ross [

12] point out, although the importance of family ties and relationships for adolescents’ mental health is widely recognized, such relationships can have either a positive or negative impact on young people, closely linked to the degree of family functionality.

Several studies have shown a positive correlation between family functionality and psychological well-being in adults. This means that better family functionality is directly related to higher levels of psychological well-being [

13]. Similarly, a study conducted among high school students in Ecuador found that higher family functionality was associated with greater subjective well-being [

14].

In light of this complexity, the present study seeks to overcome the limitations of previous research through an innovative methodological approach that combines traditional analyses with the potential of network analysis.

To this end, protective and risk factors for mental health were identified through correlational analyses and multiple regression models. The network structure of psychological well-being and mental health variables was examined using network analysis, triangulation of findings between traditional methods and network analysis was carried out to validate the convergence of results, and an integrative model was developed incorporating the cultural specificity of the Colombian Caribbean context.

The following Integrative Hypotheses are presented:

H1: Differential Perceived Social Support by Source and Cultural Context

Among urban young adults in the Colombian Caribbean, support from friends (horizontal) is expected to have a greater impact on well-being and mental health than family support (vertical), due to processes of autonomy and changes in support networks. This hypothesis is grounded in the buffering role of social support against stress [

15] and in the relevance of support sources for social well-being [

3]. Evidence from Latin America confirms the importance of peer support among urban youth [

5,

9], and systematic reviews highlight its differential effect on mental health [

16].

H2: Social Coherence as a Culturally Sensitive Protective Factor

In urban contexts of the Colombian Caribbean, characterized by high complexity, cultural diversity, and uncertainty, social coherence understood as the ability to comprehend and make sense of social dynamics acts as a protective factor against psychological distress. This concept, a cornerstone of social well-being according to [

3], has shown relevance in scenarios marked by high mobility and inequality [

8]. A systematic review in multicultural contexts confirms its role in resilience and mental health [

17], and regional studies corroborate this finding in the Colombian Caribbean [

5].

H3: Social Support as a Moderator/Mediator of Family Crises and Mental Health

Perceived social support acts as a mediator or moderator between family crises and mental health, buffering the negative effect of stressful events on psychological well-being, particularly in contexts of vulnerability and social change. This protective effect is explained by the stress-buffering model [

15] and the theories of Keyes [

4] and Ryff [

1]. Latin American evidence confirms this role in populations affected by family and social crises [

18,

19], and a systematic review supports its function in the face of adverse life events [

20].

H4: The High-Autonomy Paradox in Collectivist Contexts

In urban contexts of the Colombian Caribbean, high levels of autonomy may be associated with greater psychological distress due to the tension between individualistic values and the collectivist expectations characteristic of the region. Although autonomy is a key element in Western theories of well-being [

1], research in Latin America shows that it can generate role conflicts and isolation in collectivist cultures [

5,

20]. A systematic review confirms that its protective effect depends on the cultural context [

8].

2. Materials and Methods

To test the hypotheses, a cross-sectional descriptive–correlational design was implemented with the aim of examining the relationships among variables of psychological well-being, social support, family functionality, and mental health in a sample from urban populations in the Colombian Caribbean. The study integrated traditional statistical analyses with network analysis to achieve methodological triangulation and to compare the validity of the findings using different analytical strategies.

Participants

The study was conducted in the Caribbean region of Colombia, specifically in the Department of Atlántico (Barranquilla District) and the Department of Bolívar (Cartagena District), in low socioeconomic status neighborhoods, using accessibility and snowball sampling. Two clusters were selected one in each district/municipality and the instruments were administered in the selected area by previously trained personnel. Households without family members over the age of 18 were excluded. Recruitment for participation was carried out through educational institutions and foundations with representativeness in the study context, which is essential in community-based research, as it facilitates access and promotes the active participation of families.

The sociodemographic characteristics of the sample showed a gender distribution of 79 men (19.2%) and 333 women (80.8%). The mean age was 40.27 years (SD = 14.78, range 18–65 years). Regarding educational level, 13 participants (3.2%) had no formal education; the most represented levels were completed secondary education (136 participants, 33%), incomplete secondary education (84 participants, 20.4%), and technical education (90 participants, 21.8%). Additional participant data are available in the supplementary material (

Table 1).

Instruments

The instruments were administered at times agreed upon with the participants to avoid fatigue effects and the possibility of falsified responses. Data collection was conducted in two separate sessions with a minimum interval of two days, following the signing of informed consent.

Ryff’s Psychological Well-Being Scale: The Spanish adaptation validated by Díaz et al. [

24] was used, which assesses six dimensions of psychological well-being across 25 items: self-acceptance, positive relations, autonomy, environmental mastery, personal growth, and purpose in life. The scale uses a 6-point Likert format (1 = strongly disagree to 6 = strongly agree). Reliability coefficients for the study sample ranged from α = 0.73 to α = 0.86 across the different dimensions.

Keyes’ Social Well-Being Scale [

3]: The adapted version was used, which assesses five dimensions of social well-being through 25 items: social integration, social acceptance, social contribution, social actualization, and social coherence. It uses a 5-point Likert scale (1 = never to 5 = always). Cronbach’s alpha coefficients for the sample ranged from α = 0.71 to α = 0.82.

Subjective/Emotional Well-Being Scale: Life satisfaction was assessed using 5 items on a 5-point Likert scale (1 = never to 5 = always) [

22].

Positive and Negative Affect Schedule (PANAS) [

23]: This instrument measured positive and negative emotions using a 12-item validated version for Latin American populations, with responses given on a 5-point Likert scale (1 = never to 5 = always).

Multidimensional Scale of Perceived Social Support: Three subscales were administered, totaling 12 items, which assess perceived social support from family, friends, and significant others. Each subscale uses a 7-point Likert format, and reliability coefficients for the sample were above α = 0.85 [

25].

Self-Reporting Questionnaire (SRQ): The SRQ validated for the Colombian population was used, consisting of 30 items [

26], allowing the screening of common mental health problems, including anxiety symptoms, depressive symptoms, and alcohol-related problems. The psychosis indicator was not considered due to the elevated scores obtained. It uses a dichotomous response format (yes/no), with cut-off points established for the Colombian population.

Family APGAR: This tool, developed by Smilkestein [

27] in 1978, consists of five closed-ended questions in a self-administered questionnaire that assesses the family functioning as perceived by the respondent, allowing the suspicion of dysfunction but not its diagnosis. Each question can be scored from 0 to 4 (never, almost never, sometimes, almost always, and always); the questionnaire yields scores from 0 to 20, where scores of 9 or less indicate severe family dysfunction, 10 to 13 indicate moderate family dysfunction, 14 to 17 indicate mild family dysfunction, and scores above 18 indicate good family functioning.

Normative and Non-Normative Family Crises: A specific instrument or ad-hoc questionnaire that assesses situations such as violent death, natural death, illness, separation, leaving the household, arrival of a new member, starting school, expulsion from school, unemployment, relationship problems, retirement, economic changes, pregnancy, adoption, and infidelity.

Statistical Analyses

The database was prepared in MS Excel, where the extracted data were coded, and an initial filtering process was performed. In IBM SPSS Statistics v.29, the variables were analyzed using absolute and relative frequencies in percentages or with measures of central tendency and dispersion, after verifying the normality of the distribution.

The study integrated traditional statistical analyses with network analysis to achieve methodological triangulation and to compare the validity of the findings using different analytical strategies.

Correlations between variables were examined using Spearman’s coefficient, which is appropriate for ordinal data and data not necessarily normally distributed.

Stepwise forward multiple linear regression models were implemented to identify the most significant predictors of mental health. In addition, binary logistic regression was performed to examine categorical predictors of mental health problems.

Network Analysis: Network analysis was conducted using JASP software with the following specifications:

Estimator: EBICglasso for partially correlated networks

Threshold: Significant with Bonferroni correction

Centrality measures: betweenness, closeness, and strength

Clustering measures: Barrat, Onnela, WS, and Zhang

Subgroup analyses: city, gender, family crises, life cycle stage, and family functionality

The results of traditional analyses were systematically compared with the findings from network analysis to identify convergences and divergences. The consistency of protective and risk factors identified by both methods was evaluated.

Ethical Considerations

This study complied with the provisions of Resolution 8430 of 1993 [

21], which regulates health research in Colombia, and with the Helsinki Declaration [

22]. Informed consent was obtained from all subjects involved in the study. It was approved by the Research Ethics Committee in the Health Area of Universidad del Norte under Minutes No. 264 of 2022.

3. Results

3.1. Psychological and Social Well-Being

Analysis of the dimensions of psychological well-being according to Ryff’s scale showed that autonomy had the highest mean score (M = 24.79, SD = 5.48), followed by purpose in life (M = 24.53, SD = 5.49) and environmental mastery (M = 23.12, SD = 5.12). Conversely, positive relations had the lowest mean score (M = 15.67, SD = 4.87), suggesting challenges in building satisfactory interpersonal relationships in urban contexts of the Colombian Caribbean (

Table 2).

Table 2 also presents Keyes’ social well-being results, where social contribution obtained the highest mean score (M = 20.01, SD = 5.93), indicating that participants perceive themselves as contributing positively to their community. However, social coherence showed the lowest mean score (M = 11.94, SD = 4.06), which may reflect difficulties in understanding social dynamics in contexts of urban complexity.

Subjective well-being showed a mean life satisfaction score of 17.12 (SD = 5.49), while perceived social support results indicated that family support had the highest mean score (M = 22.53, SD = 7.22), followed by friend support (M = 21.11, SD = 7.37) and support from significant others (M = 17.93, SD = 8.89).

3.2. Prevalence of Mental Health Problems

Table 3 shows an overall prevalence of mental health problems of 11.33% in the total sample, while alcohol-related problems reached 14.46%. Cartagena shows higher prevalences of mental health problems, psychosis, and alcoholism compared to Barranquilla.

Table 4 shows that 36.5% of families present good functioning, 33.1% mild dysfunction, 8.4% moderate dysfunction, and 9.0% severe dysfunction. In caregiver burden, the absence of overload predominates, although there is a fraction with intense burden that requires attention.

In family functionality, a mixed picture is observed: although good function and mild dysfunction predominate, around 1 in 4 families present moderate or severe dysfunction, which may affect the mental health and well-being of their members.

3.3. Correlational Analysis: Protective and Risk Factors

Spearman correlations revealed significant patterns between the dimensions of well-being and mental health indicators.

Table 4 shows that social acceptance emerged as the strongest protective factor, displaying significant negative correlations with mental health screening (r = -0.405, p < 0.01) and mental health problems (r = -0.362, p < 0.01). As Keyes states, “social acceptance reflects trust, acceptance, and positive attitudes toward others—indicators of mental health”.

Social coherence also exhibited significant protective associations (r = -0.292 with mental health screening, r = -0.279 with mental health problems), confirming its role as a mediator between understanding the social environment and psychological well-being. Subjective well-being showed protective correlations as well (r = -0.215 with screening, r = -0.256 with mental health problems), validating the importance of affective balance for mental health (

Table 5).

Regarding perceived social support,

Table 4 shows that friendship support displayed stronger protective correlations (r = -0.212 with mental health screening, r = -0.208 with mental health problems) compared to family support (r = -0.167 with mental health problems). This pattern suggests differential effects depending on the source of support, confirming the hypothesis of culturally contextualized differential social support.

Family functioning, as measured by the APGAR, showed significant negative correlations with mental health problems (r = -0.188, p < 0.05), whereas the Zarit Burden Interview exhibited stronger correlations (r = -0.290 with screening, r = -0.268 with mental health problems) (

Table 5).

3.4. Bivariate Analysis of Sociodemographic Variables and Mental Health

The bivariate analysis of demographic variables and mental health is presented in

Table 5. The bivariate analysis identified specific sociodemographic risk factors. Family structure showed significant associations (p < 0.001), with single-parent families presenting a higher risk (7 out of 15 cases at high risk). Couple problems emerged as a significant risk factor (p < 0.001), with 7 out of 19 cases at risk.

Social support variables showed consistent protective effects. The absence of support from significant others was associated with higher risk (9 out of 20 cases), while its presence was protective (7 out of 158 cases at high risk). Similar patterns were observed for family support and support from friends. The full table is provided in the supplementary material.

Table 5.

Bivariate analysis of risk and protective factors for mental health problems.

Table 5.

Bivariate analysis of risk and protective factors for mental health problems.

|

Variable

|

Category

|

n |

n |

Sig. |

|

Family structure

|

Nuclear |

59 |

1 |

<.001ᵃ,ᵇ,* |

| |

Extended |

64 |

4 |

|

| |

Expanded |

10 |

1 |

|

| |

Single-parent |

8 |

7 |

|

| |

Reconstituted |

13 |

3 |

|

| |

Conjugal dyad |

6 |

0 |

|

| |

Single-person |

2 |

0 |

|

|

Alcohol consumption

|

No |

142 |

12 |

.157ᵃ |

| |

Yes |

20 |

4 |

|

|

Tobacco consumption

|

No |

159 |

14 |

.014ᵃ,ᵇ,* |

| |

Yes |

3 |

2 |

|

|

Other substance use

|

No |

160 |

16 |

.655ᵃ,ᵇ |

| |

Yes |

2 |

0 |

|

|

Separation

|

No |

150 |

12 |

<.001ᵃ,ᵇ,* |

| |

Yes |

12 |

2 |

|

| |

Yes, ongoing |

0 |

2 |

|

|

Unemployment

|

No |

88 |

6 |

0.244453 |

| |

Yes |

48 |

8 |

|

| |

Yes, ongoing |

26 |

2 |

|

|

Relationship problems

|

No |

146 |

9 |

<.001ᵃ,ᵇ,* |

| |

Yes |

12 |

7 |

|

| |

Yes, ongoing |

4 |

0 |

|

|

Support from significant others

|

Absent |

11 |

9 |

<.001ᵃ,* |

| |

Present |

151 |

7 |

|

|

Family support

|

Absent |

19 |

8 |

<.001ᵃ,* |

| |

Present |

143 |

8 |

|

|

Friend support

|

Absent |

44 |

11 |

<.001ᵃ,* |

| |

Present |

118 |

5 |

|

|

Zarit scale

|

No burden |

31 |

3 |

.021ᵃ,ᵇ,* |

| |

Mild burden |

2 |

1 |

|

| |

Severe burden |

6 |

5 |

|

|

Family APGAR

|

Good functioning |

63 |

2 |

<.001ᵃ,* |

| |

Mild |

56 |

3 |

|

| |

Moderate |

12 |

3 |

|

| |

Severe |

11 |

5 |

|

3.5. Traditional Predictive Models

Stepwise regression identified a final model explaining 42.2% of the variance in mental health problems (R² = 0.422; F = 17.86; p < 0.001). Predictors included (

Table 6):

Social acceptance (β = -0.248, t = -3.87, p < 0.001) – strongest predictor.

Negative emotions (β = -0.268, t = -4.46, p < 0.001) – second strongest predictor.

Family crisis due to separation (β = 3.272, t = 3.05, p = 0.003) – only positive predictor.

Family APGAR (β = -0.199, t = -2.54, p = 0.012) – family protective factor.

Friend support (β = -0.082, t = -2.29, p = 0.023) – protective horizontal support.

Social coherence (β = -0.193, t = -2.14, p = 0.034) – social mediating factor.

In the stepwise regression analysis, the first model included the variable social acceptance, which explained a significant proportion of the variance in mental health problems (β = -0.321; F = 27.33). Subsequently, the incorporation of negative emotions substantially improved the model fit (β = -0.363 and β = -0.347; F = 31.90). In the following steps, family crisis due to separation, Family APGAR, friend support, and social coherence were progressively added, resulting in a final model that explained 42.2% of the variance (R² = 0.422; F = 17.863; p < 0.001).

In this final model, social acceptance (β = -0.248) and negative emotions (β = -0.268) remained the most relevant predictors, while family crisis due to separation was the only positive risk factor (β = 3.272). Family APGAR (β = -0.199), friend support (β = -0.082), and social coherence (β = -0.193) acted as protective factors. Full details of each model are presented in

Table 6.

3.6. Binary Logistic Regression Model

In the final binary logistic regression model (Model 4a), both risk and protective factors associated with mental health problems were identified.

Among the significant risk factors, couple problems (B = 3.487; OR = 32.70; p = 0.001) and social acceptance (B = 3.886; OR = 48.74; p = 0.003) stood out, substantially increasing the likelihood of presenting mental health problems.

In contrast, several protective factors were identified: social coherence (B = -4.076; OR = 0.017; p = 0.001), subjective well-being (B = -2.190; OR = 0.112; p = 0.026), and Family APGAR (B = -0.243; OR = 0.784; p = 0.004), all of which were significantly associated with a reduced probability of risk.

Taken together, these findings highlight the importance of family dynamics and social networks in both generating risks and providing protection against mental health problems in the Colombian Caribbean region. (

Table 7).

Variables entered in Step 1: Couple problems (Categorical), Family separation (Categorical), Friends’ support (Grouped), Family support (Grouped), Social coherence (Grouped), Social acceptance (Grouped), Subjective well-being (Grouped), Family APGAR. Final model fit: −2 Log Likelihood = 47.033; Cox & Snell R² = 0.239; Nagelkerke R² = 0.544; Model Chi-square = 42.109, df = 5, p < 0.001.

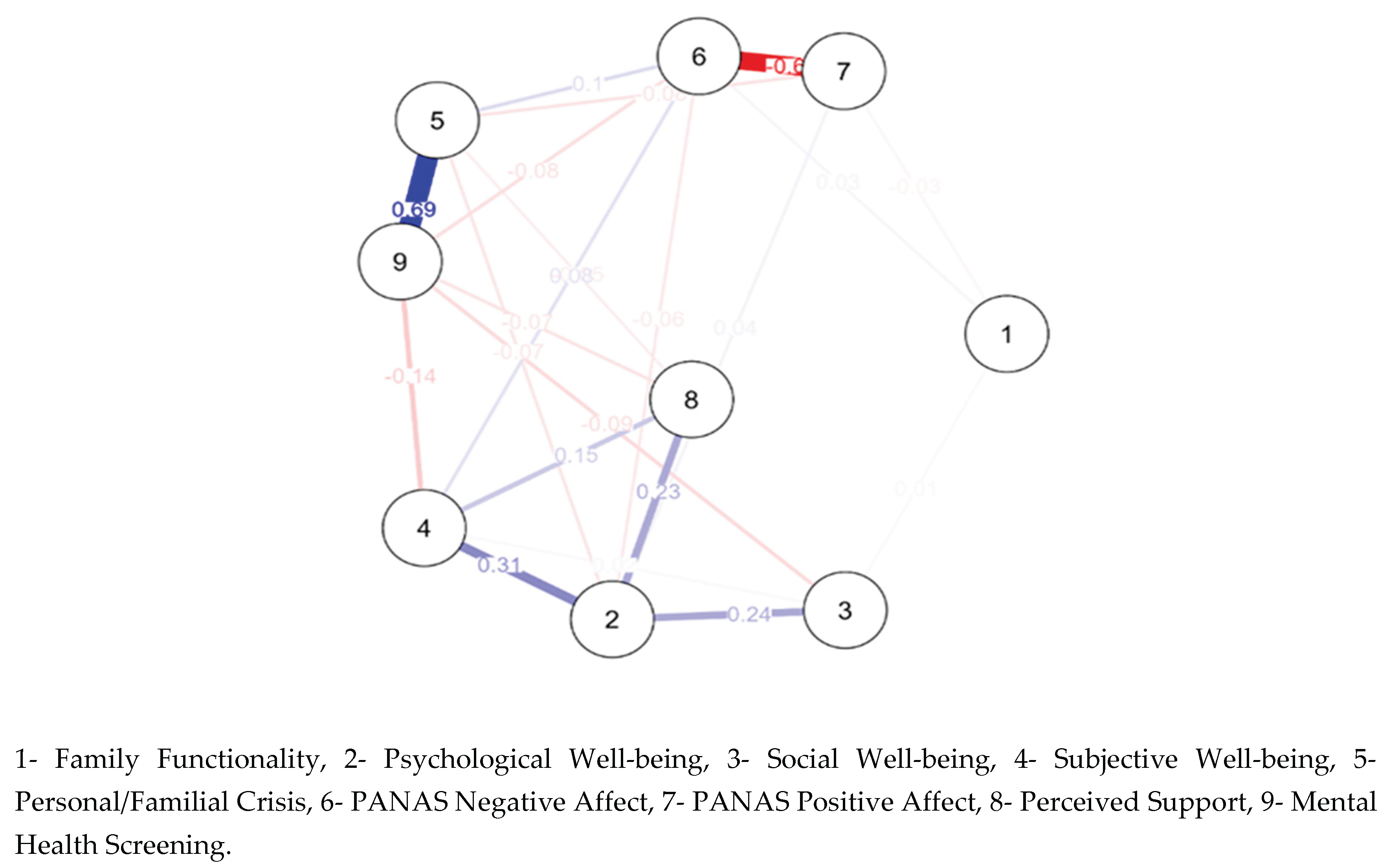

3.7. Network Analysis: General Structure of the Network

The network analysis was carried out based on 9 nodes confirmed by the scores of the variables: Family Functionality, Psychological Well-being, Social Well-being, Subjective Well-being, Personal/Familial Crisis, PANAS Negative Affect, PANAS Positive Affect, Perceived Support, and Mental Health Screening. The number of edges was 21/36, and the network showed a complex structure of interconnections among psychological well-being and mental health variables, with moderate density (0.417) and specific clusters according to variable types and their interactions (

Table 8).

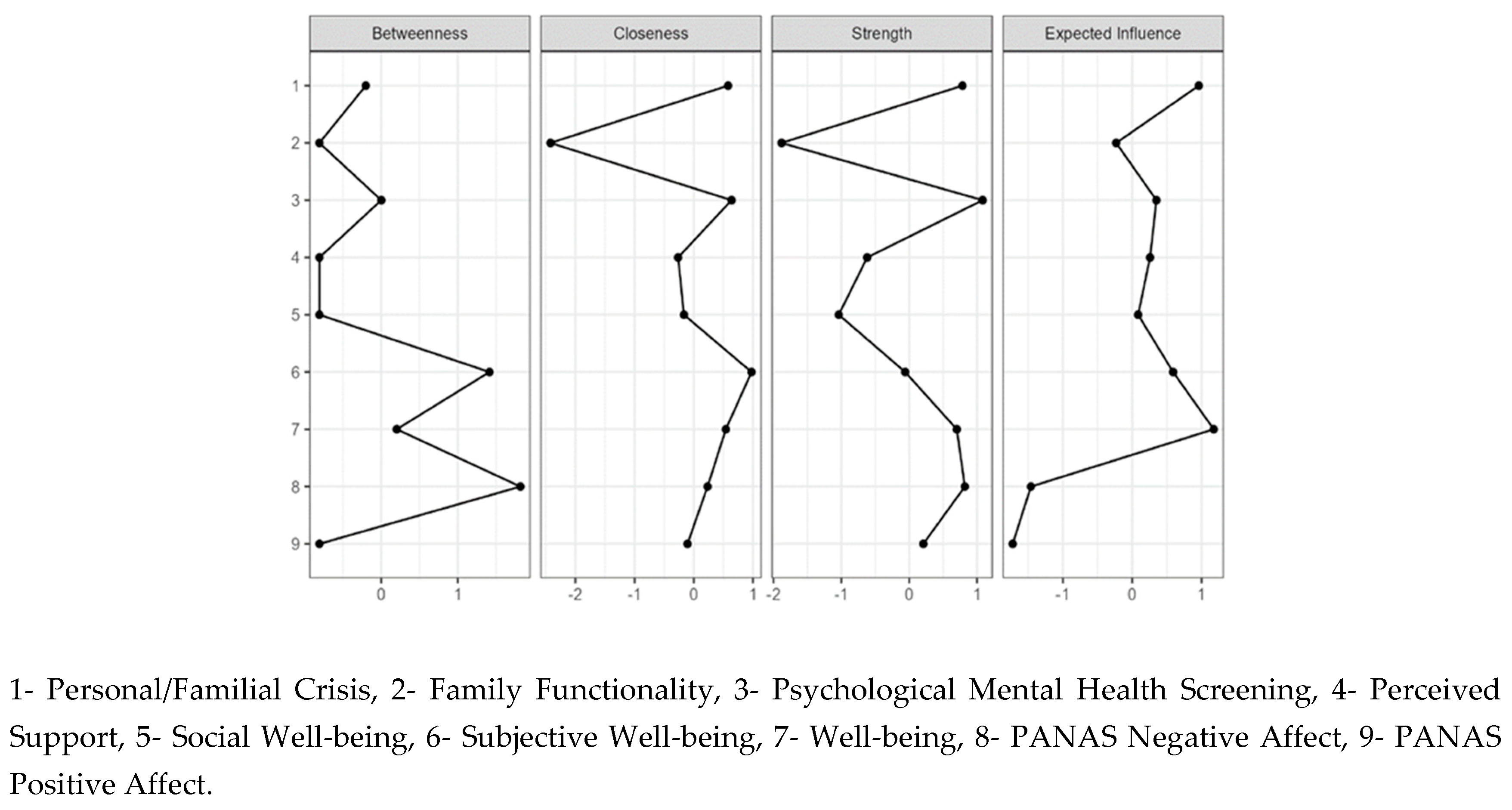

Using centrality measures, key nodes were identified within the network structure (

Figure 1):

•Strength centrality: Social acceptance, social coherence, and subjective well-being emerged as the nodes with the strongest connections.

•Betweenness centrality: Family support and negative emotions showed high betweenness, suggesting their role as bridges between different clusters.

•Closeness centrality: The dimensions of social acceptance and social coherence (social well-being) showed greater proximity to other nodes.

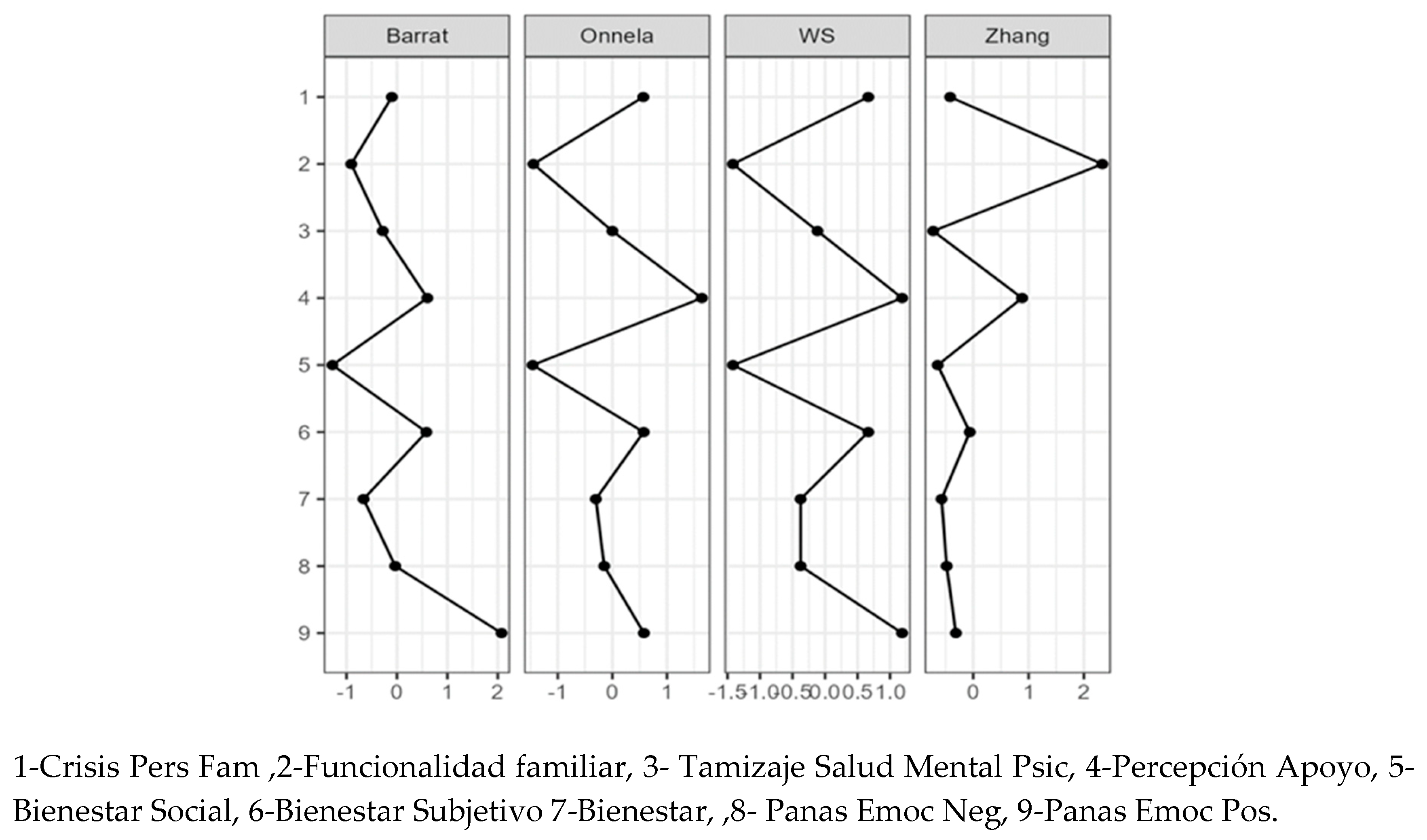

In the clustering analyses, three main groups emerged (

Table 9 and

Figure 2):

•Social Well-being Cluster: Social acceptance, social coherence, and social integration.

•Family Support Cluster: Family APGAR, family support, and family crises.

•Individual Well-being Cluster: Ryff’s psychological well-being and emotions.

The clustering measures showed relevant variations depending on the method used (Barrat, Onnela, WS, and Zhang). In general, positive values were identified for protective variables such as PANAS Positive Affect (Barrat = 2.076; Onnela = 0.577; WS = 1.185), Subjective Well-being (Barrat = 0.584; Onnela = 0.573; WS = 0.665), and Perceived Support (Barrat = 0.603; Onnela = 1.639; WS = 1.185; Zhang = 0.883), indicating greater cohesion around these dimensions within the network.

In contrast, variables associated with higher vulnerability, such as Social Well-being (Barrat = -1.280; Onnela = -1.459; WS = -1.416; Zhang = -0.643), Family Functionality (Barrat = -0.906; Onnela = -1.445; WS = -1.416), and Psychological Well-being (Barrat = -0.662; Onnela = -0.302; WS = -0.376; Zhang = -0.573), showed negative coefficients across most methods, reflecting lower connection density.

Notably, the Zhang method displayed a differentiated pattern, with a high positive value for Family Functionality (2.334) in contrast to the other methods, and a negative value for Positive Affect (-0.314), suggesting this algorithm’s particular sensitivity to network structure.This section may be divided by subheadings. It should provide a concise and precise description of the experimental results, their interpretation, as well as the experimental conclusions that can be drawn.

Overall, the network structure suggests that positive emotions and perceived support act as potential protective factors, whereas personal and family crises, as well as negative emotions, are associated with a higher risk of mental health problems. The inverse interaction between subjective well-being and psychological well-being deserves further analysis, as it may reflect either a measurement phenomenon or a particular pattern in the population under study (

Figure 3).

3.8. Network Analysis: Subgroups

Analysis by City. The differentiated analyses between Barranquilla and Cartagena revealed generally similar network structures, but with specific differences in the centrality of certain variables. In Barranquilla, friendship support showed greater centrality, whereas in Cartagena, family support was more central. See supplementary data.

Analysis by Gender. The gender-differentiated networks showed distinct patterns. Among men, autonomy and environmental mastery displayed greater centrality, whereas among women, positive relationships and social support were more central.

Analysis by Family Crises. Participants with high levels of family crises showed networks with lower overall density but greater centrality of external social support, suggesting compensatory mechanisms. In contrast, those with low family crises presented denser networks centered on family functionality.

Analysis by Individual Life Cycle. Age-group analyses revealed significant differences in network structure. Young adults (18–30 years) showed greater centrality of friendship support and autonomy, whereas adults (31–50 years) presented greater centrality of family functionality and social coherence. Older adults (51+ years) showed centrality of subjective well-being and social acceptance.

Analysis by Family Functionality. Families with adequate functionality showed dense and balanced networks, whereas families with some degree of dysfunction presented fragmented networks with greater reliance on external social support.

3.9. Triangulation of Results across Methods

A robust convergence is observed in the main findings:

Central Node in Network Analysis (high strength centrality).

•Social Coherence: Significant in predictive models and central in network analysis, confirming its mediating role.

•Family Crises: Main risk factor in regression (β = 3.272) and associated with network fragmentation in network analysis.

•Differential Social Support: Traditional analyses showed a stronger protective effect of friendship support, confirmed by the higher centrality of this variable in the youth network analysis.

•Family Functionality: Protective in both analyses, with convergent evidence of its structuring role in well-being networks.

4. Discussion

The results provide convergent and robust evidence on the determinants of psychological well-being and mental health in urban populations of the Colombian Caribbean. The methodological triangulation between traditional statistical analyses and network analysis revealed consistent patterns that strengthen the validity of the findings and offer a deeper understanding of the complex dynamics of well-being in culturally specific contexts.

Social acceptance emerges as the most consistent and powerful protective factor, identified both as the strongest predictor in multiple regression models and as the node with the highest centrality in the network analyses. This finding is consistent with Keyes’ [

28] conceptualization of social acceptance as “the perception that one is accepted by others and accepts others,” constituting a fundamental mechanism of social integration in community contexts.

In the specific context of the Colombian Caribbean, characterized by a collectivist culture with an emphasis on social cohesion, social acceptance acquires particular relevance as a mediator between individual and community functioning. The consistency of this finding across different methodological approaches suggests that interventions aimed at strengthening social acceptance could have significant effects on promoting regional psychological well-being.

Validation of the Integrative Hypotheses

Hypothesis 1: Differential Perceived Social Support by Source and Cultural Context. The results partially confirm this hypothesis. Correlational analyses showed that friendship support exerts a stronger protective effect than family support against mental health problems. However, the network analysis highlights that this differentiation is more evident in specific subgroups, particularly among urban youth, where friendship support showed greater centrality.

This differentiation reflects processes of social transition in urban contexts of the Caribbean, where young people experience greater social mobility and autonomy, shifting traditional patterns of family support toward more horizontal networks. As noted by Moreno-Carmona et al. [

9], “horizontal support facilitates the development of social and emotional competences in non-family contexts,” which is particularly relevant in populations undergoing sociocultural transformations.

Hypothesis 2: Social Coherence as a Culturally Sensitive Protective Factor. This hypothesis was fully validated. Social coherence showed significant negative correlations with mental health problems and emerged as a significant predictor in the regression models. In the network analysis, social coherence displayed high centrality and functioned as an integrative node across different clusters of well-being.

In highly complex urban contexts such as those of the Colombian Caribbean where traditional and modern dynamics coexist—the capacity to make sense of social experience becomes fundamental for psychological well-being. This finding is consistent with research highlighting the importance of social coherence in contexts of change and cultural diversity [

8].

Hypothesis 3: Social Support as a Moderator/Mediator of Family Crises and Mental Health. The results provide robust evidence for this hypothesis. Bivariate analyses showed that the presence of social support significantly reduces the risk of mental health problems, even in the presence of family crises. The network analysis identifies that, among participants with high levels of family crises, external social support displays greater centrality, suggesting compensatory mechanisms.

Family crises due to separation emerged as the main identified risk factor, but their impact is significantly attenuated in the presence of strong social support. This pattern confirms the stress-buffering model proposed by Cohen and Wills [

15] and validates the importance of social support as an adaptive resource in situations of family adversity.

Hypothesis 4: The Paradox of High Autonomy in Collectivist Contexts. This hypothesis was not confirmed in the analyses. Contrary to expectations, autonomy did not show negative associations with mental health. In the network analyses, autonomy maintained a neutral or slightly protective profile, with no evidence of adverse effects within the collectivist context of the Colombian Caribbean.

This result suggests that urban modernization processes in the Colombian Caribbean have fostered a cultural adaptation that allows the coexistence of individual autonomy values with traditional collectivist norms, without generating significant psychological conflict. This contrasts with research in more traditional contexts, where high autonomy can generate cultural tensions [

20].

Convergence between Classical Analysis and Network Analysis

The convergence between the findings obtained through traditional analyses and network analysis reinforces the internal and external validity of the results. This alignment between different methodological approaches has previously been reported as an effective strategy to increase interpretive robustness in psychosocial and mental health studies [

7,

29].

At the level of central variables, it was observed that the main predictors identified in the regression model’s social acceptance, social coherence, and family crises coincided with the nodes of highest centrality in the network analysis. This consistency supports the idea that both methods capture complementary aspects of complex phenomena, integrating both the magnitude of associations and their structural role within a system of relationships [

30].

At the level of relational structures, the clustering patterns identified in the network were consistent with the correlations and theoretical dimensions derived from classical analyses. The clusters of social well-being, family support, and individual well-being reflect constructs previously validated in the literature, such as the multidimensional well-being model proposed by Keyes [

28] and the social and family support frameworks associated with mental health [

31].

Finally, at the level of subgroup differences, the variations found by city, sex, and life cycle showed correspondence across both methods. The differentiated network structures by subgroups confirm that trajectories of well-being and vulnerability are modulated by sociodemographic variables, which is consistent with previous findings demonstrating the influence of context and life stage on mental health [

31,

33].

Taken together, this methodological convergence not only strengthens the credibility of the results but also provides a more holistic view of the interrelation between social determinants and mental health indicators, offering a solid framework for the design of contextualized, multicomponent interventions.

Theoretical Implications for Well-being Models

The findings contribute significantly to the theoretical development of integrative models of psychological well-being. The convergence between traditional analyses and network analysis suggests that well-being can be conceptualized both as a set of interrelated dimensions (traditional perspective) and as a dynamic network of interdependent factors (network perspective).

First, the Social Well-being Centrality Model proposes that the social dimensions of well-being particularly social acceptance and social coherence act as central nodes mediating the relationships between individual and family factors and mental health. This finding expands classical models, traditionally focused on individual dimensions [

28], by incorporating the structural importance of social functioning as a cross-cutting determinant of mental health. Previous studies have pointed out that social networks and community integration play a key role in promoting well-being, facilitating access to resources, and buffering the impact of stressors [

31,

34].

Second, the Social Support Compensation Model suggests that, in contexts of family crises, the availability of external social support can reorganize the structure of well-being to preserve psychological stability. This pattern is consistent with theories of adaptive plasticity, which propose that social and psychological systems can reconfigure themselves to maintain balance in the face of disruptions [

35]. Evidence shows that social support not only reduces the likelihood of developing symptoms of depression and anxiety but also modulates resilience in the face of adverse events [

36].

Finally, the Cultural Specificity Model emerges from the differentiated patterns observed in the Colombian Caribbean, where the centrality of social support stands out and the paradoxical effects of autonomy reported in other contexts are absent [

37]. This supports the need to adapt well-being models to sociocultural particularities, as the structure and meaning of psychosocial determinants may vary across contexts [

32,

38]. Incorporating this cultural specificity not only improves the predictive validity of the models but also increases their practical usefulness for designing contextualized and culturally relevant interventions.

Clinical and Intervention Implications

The findings have direct implications for the development of psychological interventions and mental health promotion programs in Colombian Caribbean contexts.

Interventions Centered on Social Acceptance. The centrality of social acceptance as a protective factor suggests that interventions aimed at strengthening positive attitudes toward others and the perception of social acceptance could have significant effects on community mental health. Group programs that promote tolerance, inclusion, and social cohesion emerge as promising strategies [

39,

40,

41].

Strengthening Social Coherence. Interventions aimed at developing the capacity to understand and make sense of social dynamics may be especially relevant in contexts of urban transformation. Educational programs that promote the comprehension of complex social dynamics and the development of coherent narratives about community experience can strengthen this protective factor [

42,

43,

44].

Differentiated Social Support Interventions. The findings on differential social support suggest the need for specific interventions according to life stage and context. For urban youth, programs that strengthen horizontal support networks (peers, friendships) may be more effective than interventions focused exclusively on the family [

45,

46,

47].

Preventive Family Interventions. The identification of family crises as the main risk factor indicates the need for prevention programs and early family interventions. Strategies aimed at strengthening family functioning and crisis management can have significant protective effects [

48,

49,

50].

Specific Cultural Considerations for the Colombian Caribbean

The results highlight the specific characteristics of the Colombian Caribbean cultural context that must be considered in the interpretation of findings and the development of interventions.

Cultural Adaptation of Autonomy. The absence of paradoxical effects of autonomy suggests a successful cultural adaptation that enables the integration of individualistic and collectivist values. This feature may reflect the influence of urban modernization processes that have generated specific cultural syntheses in the region [

51].

Centrality of Social Support. The importance of social support in its multiple forms reflects the region’s collectivist cultural heritage, where social networks constitute fundamental resources for coping with stress and promoting well-being. This characteristic should be considered in the design of interventions that build upon these cultural strengths.

Flexibility in Family Structures. The patterns of differential support according to the source suggest flexibility in support structures that transcend the traditional nuclear family. This flexibility may constitute an adaptive strength in contexts of accelerated social change.

Study Limitations

The cross-sectional design limits causal inferences, allowing only the establishment of associations between variables. Although the predictive models are robust, the directionality of the relationships requires longitudinal confirmation. Future studies should incorporate longitudinal follow-ups to establish causal relationships. The sample is concentrated in two cities of the Colombian Caribbean, which may limit generalization to other Colombian or Latin American urban contexts. The inclusion of rural populations and other regions would strengthen the external validity of the findings.

The cross-sectional design limits causal inferences, allowing only the establishment of associations between variables. Although the predictive models are robust, the directionality of the relationships requires longitudinal confirmation. Future studies should incorporate longitudinal follow-ups to establish causal relationships. The sample is concentrated in two cities of the Colombian Caribbean, which may limit generalization to other Colombian or Latin American urban contexts. The inclusion of rural populations and other regions would strengthen the external validity of the findings.

5. Conclusions

The study provides evidence on the feasibility and added value of methodological triangulation between traditional statistical analyses and network analysis for the study of psychological well-being and mental health in urban populations of the Colombian Caribbean. The findings offer convergent and robust evidence that strengthens a more detailed understanding of the complex dynamics of well-being in culturally specific contexts.

Social acceptance emerges as the most consistent protective factor, standing out simultaneously in regression models and network analyses, reaffirming its key role in psychosocial integration within collectivist contexts. Social coherence emerges as a culturally sensitive protective factor and as a mediator between individual and social functioning,

Family crises, especially marital separation, are the main risk factor; however, their effect is notably reduced by robust social support, evidencing buffering and adaptive mechanisms. Social support shows differential effects depending on the source, with horizontal support standing out among urban youth, reflecting a cultural adaptation that combines collectivist values with modern demands for autonomy.

In contrast to the autonomy paradox hypothesis, no significant negative relationship with mental health was observed; on the contrary, it showed a neutral or slightly protective effect. This suggests that, in urban and hybrid contexts of the Colombian Caribbean, autonomy can be integrated without generating psychological conflict, in line with recent studies on the cultural adaptation of individual values in collectivist societies.

Methodological triangulation demonstrated strong convergence between traditional analyses and network analysis, strengthening the validity of the results and revealing complementary perspectives on the same phenomena. Network analysis highlighted latent structures and critical nodes not detected by classical methods, as well as differentiated patterns across subgroups, underscoring the heterogeneity of well-being and the need for approaches adapted to sociodemographic and contextual characteristics.

The findings support integrative models of well-being that combine individual and social dimensions, highlighting the centrality of social functioning and proposing mechanisms of social mediation. The validation of hypotheses adapted to the Colombian Caribbean favors the development of culturally sensitive models for Latin American psychology. In addition, the identification of compensatory mechanisms through network analysis provides evidence of the adaptive plasticity of well-being and its role in resilience in the face of adversity.

The results provide guidance for public mental health policies in the Colombian Caribbean and similar sociocultural contexts, prioritizing protective factors such as social acceptance, social coherence, and differential social support. It is recommended to strengthen community networks to moderate the impact of family crises and promote social cohesion, as well as to develop specific family support and education policies to prevent crises and reinforce family functioning.

The findings highlight the need for differentiated policies according to demographic characteristics, prioritizing urban youth, families in crisis, and vulnerable populations. The applied methodological triangulation sets a precedent for research in health psychology that integrates traditional methods and network analysis, demonstrating the potential of hybrid approaches that leverage the strengths of both methodologies.

The comprehensive model developed for the Colombian Caribbean can serve as a reference for comparative studies in other Latin American contexts, strengthening a culturally grounded and scientifically rigorous health psychology. Its clinical application requires interventions that translate evidence into programs for the promotion of well-being and the prevention of mental health problems, adapted to cultural specificities and local strengths.

In summary, this study demonstrates that the integration of traditional approaches and network analysis provides a richer and more nuanced understanding of psychological well-being and mental health, with important theoretical, methodological, and practical implications for the field of mental health and well-being in Latin American contexts.

Author Contributions

Conceptualization, J.E.P.C. and M.Y.E.C.; methodology, J.E.P.C. and D.C.C.; software, D.C.C ;J.E.P.C., and M.Y.E.C; validation, J.E.P.C., M.Y.E.C;D.C.C and M.C.A.M ; formal analysis, JEPC and DCC; research, M.Y.E.;,J.P.C.E;D.C.C. and A.L.R.G; resources, M.Y.E.C.; data curation, D.C.C ;J.E.P.C., and M.Y.E.C; writing: preparation of original draft, JEPC,MYEC;A.L.R.G;M.C.A.C and DCC; writing: review and editing, M.Y.E.C.,A.L.R.G. and M.C.A.M; Visualization, M.Y.E.C, J.P.C.E and D.C.C; supervision, JEPC and MYEC; project administration, MYEC; funding acquisition, MYEC. All authors have read and agreed to the published version of the manuscript.

Funding

The author(s) declare that financial support was received for the research and/or publication of this article. This work was funded by Call 918/2022 "Strengthening Regional Public Health Research Capacities," issued by the Ministry of Science of Colombia under Contract No. 587-2022.

Institutional Review Board Statement

The study was conducted in accordance with the Declaration of Helsinki and was approved by the Research Ethics Committee in the Health Area of Universidad del Norte under Minutes No. 264 dated April 28, 2022.

Informed Consent Statement

Informed consent was obtained from all subjects involved in the study.

Data Availability Statement

The original data presented in the study are openly available in

https://osf.io/k72ts https://doi.org/10.17605/OSF.IO/M9KVJ

Conflicts of Interest

The authors declare no conflicts of interest. The funders had no role in the design of the study; in the collection, analyses, or interpretation of data; in the writing of the manuscript; or in the decision to publish the results.

References

- Ryff, CD. Psychological well-being revisited: Advances in the science and practice of eudaimonia. Psychother Psychosom. 2014;83(1):10-28. [CrossRef]

- Díaz D, Rodríguez-Carvajal R, Blanco A, Moreno-Jiménez B, Gallardo I, Valle C, van Dierendonck D. Adaptación española de las escalas de bienestar psicológico de Ryff. Psicothema. 2006;18(3):572-7. https://www.psicothema.com/pi?pii=3255.

- Keyes CLM. Social well-being. Social Psychology Quarterly. 1998; 61(2), 121–140.

- Keyes CLM. The mental health continuum: From languishing to flourishing in life. Journal of Health and Social Behavior. 2002; 43(2), 207–222. https://pubmed.ncbi.nlm.nih.gov/12096700/.

- Palacio-Sañudo J, Madariaga C, Sabatier C, Álvarez J, Restrepo D. Factores psicosociales asociados al bienestar de familias en el Caribe colombiano. Suma Psicológica.2020; 27(1), 1–11. [CrossRef]

- González MT, Landero Rl. Variables asociadas a la depresión: un modelo de regresión logística. Revista Electrónica de Metodología Aplicada. 2006; 11(1), 16–30.

- Epskamp S, Borsboom D, Fried E I. Estimating psychological networks and their accuracy: A tutorial paper. Behavior Research Methods.2016; 50(1), 195–212. [CrossRef]

- Joshanloo, M. Eastern conceptualizations of happiness: Fundamental differences with western views. Journal of Happiness Studies. 2014; 15, 475–493. [CrossRef]

- Moreno-Carmona ND, Palacio-Sañudo JE, Jiménez-Morales J. Apoyo social y funcionamiento familiar en jóvenes universitarios. Revista Colombiana de Psicología. 2018; 27(1), 47–58.

- Ruiz Eslava LF, Rodríguez Pérez DA. Percepción de las necesidades en salud mental de población migrante venezolana en 13 departamentos de Colombia. Reflexiones y desafíos. Rev. Ger. Pol. Sal [Internet]. 2020; 19:1-18. Available from: https://revistas.javeriana.edu.co/index.php/gerepolsal/article/view/31372.

- Naberushkina E, Besschetnova O, Sudorgin O. Familia y valores familiares en las percepciones de la generación joven. La Revista de Estudios de Política Social. 2024; 22(4), 697-714. [CrossRef]

- Woodman E, Ross J. Building family connectedness—A new practice tool for social workers. The British Journal of Social Work. 2022; 52 (6), 3130–3150, https://doi.org/10.1093/bjsw/bcab226. [CrossRef]

- Cargua Silva N, Gaibor González I. Funcionalidad familiar y bienestar psicológico en adultos LATAM Revista Latinoamericana de Ciencias Sociales y Humanidades. 2023; IV (2), 2314. [CrossRef]

- Lara-Moran L, Gaibor-Gonzalez I, Funcionalidad familiar y su relación con el bienestar subjetivo en estudiantes de bachillerato.LATAM Revista Latinoamericana de Ciencias Sociales y Humanidades. 2023; 4 (1), 987. [CrossRef]

- Cohen S, Wills TA. Stress, social support, and the buffering hypothesis. Psychological Bulletin. 1985; 98(2), 310–357 https://psycnet.apa.org/doi/10.1037/0033-2909.98.2.310.

- Holt-Lunstad J, Smith TB, Baker M, Harris T, Stephenson D. Loneliness and social isolation as risk factors for mortality: a meta-analytic review. Perspect Psychol Sci. 2015;10(2):227-37. [CrossRef]

- Gopalkrishnan, N. Cultural Diversity and Mental Health: Considerations for Policy and Practice. Front Public Health. 2018 Jun 19; 6:179. [CrossRef]

- González Parra D, Parada Pérez MA, Rojas Caballero SA. Revisión sistemática de la salud mental en universitarios de América Latina [Tesis], Bucaramanga. Universidad Cooperativa de Colombia; 2021. https://hdl.handle.net/20.500.12494/44428.

- Reyes-Ruiz L, Carmona-Alvarado F, Pacheco-Ariza A, & Sánchez-Villegas M. Apoyo Social Percibido, Depresión y Ansiedad En Estudiantes de una Institución Técnica y Tecnológica del Departamento del Atlántico-Colombia. Búsqueda, 2024;11(2). [CrossRef]

- Salas-Picón WM, Avendaño-Prieto BL. Adaptación de la escala de bienestar psicológico de Ryff con una muestra de sobrevivientes del conflicto armado colombiano. Revista Criminalidad. 2022; 63(3), 229–244. [CrossRef]

- Arcila Echavarría DC, Palacio Tobón EP, Tejada Llano JH. Aplicación de instrumentos para la detección temprana de trastornos afectivos como una estrategia innovadora en salud mental: el caso SRQ y ASSIST en la Plataforma de Salud Digital CSS- SENA. Cienc. tecnol. innov. salud [Internet]. 19 de noviembre de 2024; 8:67-76. [CrossRef]

- Diener ED, Emmons R A, Larsen R J, Griffin S.The Satisfaction with Life Scale. Journal of Personality Assessment. 1985; 49(1), 71-75. [CrossRef]

- Watson D, L A Clark G. Carey. “Positive and Negative Affectivity and Their Relation to Anxiety and Depressive Disorders”,Journal of Abnormal Psychology.1988; 97(3). [CrossRef]

- Vielma-Vicente M, Rioseco P, Medina E, Escobar B, Saldivia S, Cruzat M, Vicente M. Validación del Autorreportaje de Síntomas (SRQ) como instrumento de screening en estudios comunitarios. Rev Chil Salud Ment. 1994;11(4):180-5.

- Zimet GD, Dahlem NW, Zimet SG, Farley GK. The Multidimensional Scale of Perceived Social Support. J Pers Assess. 1988;52(1):30-41. https://psycnet.apa.org/doi/10.1207/s15327752jpa5201_2.

- Vicente Benjamín, Saldivia Sandra, Melipillán Roberto, Hormazabal Naín, Carroza Ana, Pihan Rolando. Inventario Concepción: Desarrollo y validación de un instrumento de tamizaje de depresión para atención primaria. Rev. méd. Chile [Internet]. 2016 ; 144( 5 ): 555-562. [CrossRef]

- Smilkstein, G. The family APGAR: A proposal for a family function test and its use by physicians. Journal of Family Practice. 1978; 6(6), 1231–1239.

- Keyes CLM. Mental health and/or mental illness? Investigating axioms of the complete state model of health. J Consult Clin Psychol. 2005;73(3):539-48. [CrossRef]

- Borsboom D, Cramer AOJ. Network analysis: An integrative approach to the structure of psychopathology. Annu Rev Clin Psychol. 2013; 9:91-121. [CrossRef]

- Bringmann LF, Elmer T, Epskamp S, Krause RW, Schoch D, Wichers M, Wigman JTW, Snippe E. What do centrality measures measure in psychological networks? J Abnorm Psychol. 2019;128(8):892-903. https://psycnet.apa.org/doi/10.1037/abn0000446.

- Thoits, PA. Mechanisms linking social ties and support to physical and mental health. J Health Soc Behav. 2011;52(2):145-61. [CrossRef]

- World Health Organization. World mental health report: transforming mental health for all. Geneva: WHO; 2022. https://www.who.int/publications/i/item/9789240049338.

- Ryff CD, Radler BT, Friedman EM. Persistent psychological well-being predicts improved self-rated health over 9–10 years: Longitudinal evidence from MIDUS. Health Psychol Open. 2021;8(1): 2055102921991723.

- VanderWeele, TJ. On the promotion of human flourishing. Proc Natl Acad Sci USA. 2017;114(31):8148-56. [CrossRef]

- Ungar, M. The social ecology of resilience: Addressing contextual and cultural ambiguity of a nascent construct. Am J Orthopsychiatry. 2011;81(1):1-17. [CrossRef]

- Kawachi I, Berkman LF. Social ties and mental health. J Urban Health. 2001;78(3):458-67. [CrossRef]

- Ryff CD, Keyes CLM. The structure of psychological well-being revisited. J Pers Soc Psychol. 1995;69(4):719-27.

- Helliwell JF, Layard R, Sachs JD, De Neve JE, Aknin LB, Wang S. World Happiness Report 2023. New York: Sustainable Development Solutions Network; 2023.

- Kawachi I, Berkman LF. Social cohesion, social capital, and health. In: Berkman LF, Kawachi I, Glymour MM, editors. Social Epidemiology. 2nd ed. New York: Oxford University Press; 2014. p. 290-319. https://www.scirp.org/reference/referencespapers?referenceid=1119775.

- Haslam C, Jetten J, Cruwys T, Dingle GA, Haslam SA. The new psychology of health: Unlocking the social cure. London: Routledge; 2018. [CrossRef]

- De Silva MJ, McKenzie K, Harpham T, Huttly SR. Social capital and mental illness: A systematic review. J Epidemiol Community Health. 2005;59(8):619-27. [CrossRef]

- Antonovsky A. The structure and properties of the sense of coherence scale. Soc Sci Med. 1993;36(6):725-33. [CrossRef]

- Eriksson M, Lindström B. Antonovsky’s sense of coherence scale and the relation with health: A systematic review. J Epidemiol Community Health. 2006;60(5):376-81. [CrossRef]

- Carpiano, RM. Neighborhood social capital and adult health: An empirical test of a Bourdieu-based model. Health Place. 2007;13(3):639-55. [CrossRef]

- Umberson D, Montez JK. Social relationships and health: A flashpoint for health policy. J Health Soc Behav. 2010;51(Suppl): S54-66. [CrossRef]

- Seeman, TE. Health promoting effects of friends and family on health outcomes in older adults. Am J Health Promot. 2000;14(6):362-70. [CrossRef]

- Wrzus C, Hänel M, Wagner J, Neyer FJ. Social network changes and life events across the life span: A meta-analysis. Psychol Bull. 2013;139(1):53-80. [CrossRef]

- Epstein NB, Baldwin LM, Bishop DS. The McMaster Family Assessment Device. J Marital Fam Ther. 1983;9(2):171-80.

- Walsh, F. Strengthening family resilience. 3rd ed. New York: Guilford Press; 2016.

- Repetti RL, Taylor SE, Seeman TE. Risky families: Family social environments and the mental and physical health of offspring. Psychol Bull. 2002;128(2):330-66. https://psycnet.apa.org/doi/10.1037/0033-2909.128.2.330.

- Kagitcibasi, C. Autonomy and relatedness in cultural context: Implications for self and family. J Cross Cult Psychol. 2005;36(4):403-22.

|

Disclaimer/Publisher’s Note: The statements, opinions and data contained in all publications are solely those of the individual author(s) and contributor(s) and not of MDPI and/or the editor(s). MDPI and/or the editor(s) disclaim responsibility for any injury to people or property resulting from any ideas, methods, instructions or products referred to in the content. |

© 2025 by the authors. Licensee MDPI, Basel, Switzerland. This article is an open access article distributed under the terms and conditions of the Creative Commons Attribution (CC BY) license (http://creativecommons.org/licenses/by/4.0/).