1. Introduction

1.1. The Landscape of Disconnection

Connection plays a pivotal role in the lives of emerging adults, typically defined as individuals between the ages of 18 and 25. This distinct developmental stage gradually shifts young people from adolescence to full adulthood, during which they explore their identities, make important life decisions, and begin to establish independence (Arnett, 2000). Within this context, connection refers to sustained engagement with meaningful roles, relationships, and environments that provide structure, affirmation, and purpose. It includes active participation in education, employment, or community life and emotional bonds with peers, mentors, and institutions that support a sense of belonging and forward momentum. When emerging adults experience such connections, they are more likely to cultivate self-confidence, psychological resilience, and a clear sense of direction. Connection nurtures their ability to navigate uncertainty, make purposeful choices, and build lives rooted in both personal meaning and social contribution.

However, not all emerging adults experience this developmental phase within conditions that promote connection. A growing number of young people in the United States are no longer actively participating in education, employment, or structured training programs, with estimates reaching over four million young people (Brookings, 2022). These individuals, often referred to as disconnected or opportunity youth, face a convergence of structural barriers that restrict access to academic progression, sustainable employment, reliable mental health care, and consistent adult support systems (Bintliff, 2011; Bridgeland & Milano, 2012; Brookings, 2022). Despite often being associated with disconnection, poverty, marginalization, and trauma, these issues affect young people from all walks of life. Disconnection represents more than the absence of opportunity; it signals a disruption in the developmental process that can destabilize housing, health, relationships, and identity. For some, the compounded stress and uncertainty that accompany disconnection result in anxiety, depression, and a diminished capacity to envision or pursue a coherent future (Napier, Slemp, & Vella-Brodrick, 2024; Volpe, Katsiaficas, & Neal, 2021).

Still, it is important to recognize that disconnection does not equal disengagement of spirit. Even under adverse conditions, many emerging adults demonstrate resilience, vision, and a drive to reconnect with meaningful opportunities (Belfield & Levin, 2012; Guthrie, Ellison, Sami, & McCrea, 2014). As Fike and Mattis (2023) argue, traditional measurements often fail to capture the internal strengths that motivate youth to persist. These lived experiences point to the need for a more expansive developmental framework that sees potential in participation and the capacity to reimagine and re-engage life on new terms.

1.2 Disconnection as a Developmental Interruption

Disconnection during emerging adulthood often interrupts critical developmental processes such as identity formation, goal setting, and long-term planning. As discussed in

Section 1.1, when young people lack sustained engagement in education, employment, or community life, they face emotional stagnation, reduced agency, and difficulty linking present actions to future goals (Booker, Brakke, & Pierre, 2022; Hope, Hoggard, & Thomas, 2015). Instead of viewing this disconnect as a behavioral issue, consider it a disruption in developmental momentum. For many emerging adults, especially those from marginalized communities, this interruption heightens vulnerability to psychological distress, social isolation, and diminished life outcomes (Volpe et al., 2021; Napier et al., 2024).

Framing disconnection as a developmental interruption calls for deeper, identity-centered interventions. Programs prioritizing agency, cultural relevance, and purpose-driven support can move young people beyond compliance and toward enduring transformation (Marques, Lopez, & Pais-Ribeiro, 2011; Snyder, Rand, & Sigmon, 2002). Rather than merely requiring youth to return to existing systems, Infinite Hope encourages re-entry on new terms through narratives of belonging, vision, and ethical purpose (Hope et al., 2015; Nairn et al., 2025).

1.3 Hope and the Infinite Mindset as Pathways to Re-Engagement

Building on this foundation, this paper introduces a novel integration of Snyder's Hope Theory and Simon Sinek's infinite mindset to understand better how disconnected emerging adults can reconnect with purpose, direction, and possibility. Although both frameworks have influenced their respective fields, scholars have not yet synthesized them to inform re-engagement strategies for youth navigating systemic barriers. This conceptual model bridges the gap by combining motivational psychology with adaptive leadership philosophy. It contributes three core advancements. First, it unites two complementary but previously unlinked theories. Second, it proposes a psychologically and ethically grounded framework for re-engagement. Third, it offers evaluative guidance focused on sustained connection rather than short-term compliance or credentialing.

Snyder's Hope Theory defines hope as a dynamic cognitive process comprising three interrelated elements: goal setting, pathway generation, and agency. These components together form an internal framework that enables individuals to envision and pursue goals despite adversity (Gallagher & Lopez, 2009; Snyder et al., 2002). Higher levels of hope are associated with academic persistence, emotional resilience, and long-term motivation (Marques et al., 2011; Scioli et al., 2011). For disconnected youth, a lack of hope often signals disrupted agency and weakened belief in possible outcomes rather than an absence of aspiration (Booker et al., 2022; Valle, Huebner, & Suldo, 2006).

Research and practice affirm the transformative power of hope. When emerging adults lose sight of their goals or doubt their ability to achieve them, targeted interventions can help restore hope by clarifying goals, strengthening agency, and reshaping narratives to emphasize possibility (Booker et al., 2022; Cheavens, Feldman, Gum, Michael, & Snyder, 2006). These strategies go beyond addressing disengagement. They rebuild the psychological foundation required for sustained motivation and direction.

Still, hope alone is not enough. For youth facing compounding inequities, reclaiming hope also requires a resilient worldview capable of withstanding long-term adversity. Programs cultivating belief in the future must nurture hope as a mindset and method.

Simon Sinek's infinite mindset offers a vital worldview for reimagining youth development. Built upon Carse's (2012) theory of finite and infinite games, Sinek (2019) redefines leadership as a long-term commitment to meaningful purpose rather than short-term victories. He proposes that individuals and organizations thrive when guided by five enduring principles:

Advancing a Just Cause: A future-focused vision that lends significance to everyday action. The Infinite Hope framework links individual aspirations to broader ethical considerations in its goal-setting.

Building Trusting Teams: Cultivating safe, affirming spaces where people can take risks, express vulnerability, and grow. For disconnected youth, this relational safety is essential to developing hope.

Embracing Existential Flexibility: A readiness to pivot or abandon successful strategies when a more aligned path emerges. It strengthens long-term planning by encouraging intentional change.

Learning from Worthy Rivals: Seeing others not as threats but as mirrors for personal growth. This element reframes competition into self-reflection and supports a growth-oriented agency.

Leading with Courage: Choosing principled action even when outcomes are uncertain. This component reinforces a moral backbone, allowing youth to act despite fear.

These five principles are not merely abstract values. When aligned with Snyder's Hope Theory, they become a blueprint for transformation. Hope Theory defines hope as a cognitive-motivational process of goals, agency, and pathways. The Infinite Hope model builds on this foundation by introducing ethical purpose and adaptive flexibility as key components of sustained motivation.

Table 1 clarifies how Sinek's principles operate within this framework by providing concise definitions that translate each concept into practical, measurable terms relevant for youth development settings.

These leadership principles serve as the scaffolding for Infinite Hope, but their strength emerges in synthesis with Hope Theory.

Table 2 presents a conceptual comparison that integrates Snyder's cognitive-motivational model of hope with Sinek's infinite mindset philosophy. This synthesis shows how Infinite Hope weaves goal pursuit, agency, moral clarity, and adaptability into a developmental strategy for young adults facing disconnection from education, employment, or training.

Table 1 and

Table 2 illustrate how Infinite Hope synthesizes distinct theoretical traditions to form a more holistic approach. What emerges is a framework that does more than teach goal setting. It reorients emerging adults toward a life guided by purpose, trust, adaptability, and courage. The following section will explore the theoretical roots of hope and an infinite mindset, then present two integrated models to demonstrate how these constructs converge across developmental layers visually. These models will help clarify how Infinite Hope functions as a psychological catalyst and an ethical compass, particularly for disconnected youth striving to reclaim direction and future possibility.

2. Method

2.1 Conceptual Framing and Review Methodology

The Infinite Hope conceptual framework development draws from empirical research, theoretical models, and applied practices across psychology, education, youth development, and leadership studies. It synthesizes Snyder's Hope Theory (Snyder et al., 2002) and Sinek's Infinite Mindset (Sinek, 2019) into a unified model that addresses how disconnected emerging adults can re-engage with purpose, direction, and possibility. Rather than introducing new empirical data, this framework reinterprets existing scholarship to propose a practice-informed, interdisciplinary approach grounded in lived experience.

The study employed a narrative synthesis methodology to gather insights across disciplines and support the creation of a theoretically grounded framework (see

Table 3). The researcher retrieved sources from ProQuest Central, EBSCOhost Academic Search Premier, PsycINFO, ERIC, Scopus, Web of Science, and Google Scholar, supplemented by citation tracing and manual reviews. Priority was given to English peer-reviewed publications about 18-to 25-year-old emerging adults who had disconnected from education or employment.

The keyword strategy covered hope theory, agency, identity development, purpose, infinite mindset, and narrative identity. Out of 175 sources initially screened, seventy-two peer-reviewed studies met inclusion criteria and informed the framework. These included foundational works by Snyder, Rand, and Sigmon (2002), Marques et al. (2011), Sinek (2019), and Bridgeland and Milano (2012), along with studies on resilience, critical consciousness, and values-based goal pursuit (Fike & Mattis, 2023; Hope et al., 2015; Di Consiglio et al., 2025).

The researcher considered gray literature sources, including practitioner reflections and implementation models, for contextual insight, but ultimately excluded them from the final synthesis to maintain methodological rigor and focus on peer-reviewed evidence.

This integrated approach confirmed that sustainable re-engagement relies on more than behavioral compliance. Identity alignment, values clarity, and purposeful connection support the psychological transformation that underpins sustainable re-engagement. The resulting conceptual synthesis strengthens both the developmental theory and the practical utility of Infinite Hope.

2.2 Positioning Infinite Hope Among Established Motivational Theories

This section offers a comparative lens to place Infinite Hope within the broader tradition of motivational theory. Drawing from Ryan and Deci's Self-Determination Theory (2000) and Pekrun's Control-Value Theory (2006), the analysis identifies conceptual overlap, theoretical distinctions, and added value. According to Self-Determination Theory (SDT), autonomy, competence, and relatedness are three key universal needs that drive motivation. Control-Value Theory (CVT) explains how perceived control over tasks and the subjective value of those tasks shape emotional experience and self-regulated behavior (Pekrun, 2002). This framing aligns with foundational contributions by Marques et al. (2011), Sinek (2019), and Snyder et al. (2002).

The Infinite Hope construct aligns with elements of these foundational theories. For example, agency in Hope Theory parallels SDT's autonomy and CVT's control appraisals (Fike & Mattis, 2023; Marques et al., 2011; Sinek, 2019; Snyder et al., 2002). Pathways thinking reflects competence and adaptive control strategies (Pekrun, 2006). Goal setting anchored in a just cause extends intrinsic motivation and deepens the value dimension emphasized in CVT (Pekrun & Bühner, 2002). Existential flexibility introduces moral adaptability, a feature SDT and CVT rarely highlight but one that proves essential for identity reconstruction and resilience (Di Consiglio et al., 2025).

Table 4 provides a side-by-side comparison of Infinite Hope constructs and their SDT and CVT counterparts. It highlights Infinite Hope's distinctive contributions to each dimension, offering a conceptual bridge between traditional motivational theory and contemporary frameworks grounded in identity, values, and future orientation (Marques et al., 2011; Sinek, 2019; Snyder et al., 2002).

Integrating cognitive motivation, emotional regulation, and ethical orientation gives Infinite Hope its distinctive strength (Marques et al., 2011; Sinek, 2019; Snyder et al., 2002). While SDT emphasizes psychological need satisfaction and CVT addresses achievement-related emotions, Infinite Hope links personal striving with purpose-driven leadership, identity clarity, and moral vision. The framework defines hope as a goal-directed trait and a socially constructed and ethically grounded practice that individuals cultivate through adaptive strategy, community support, and principled courage (Shao, 2025).

This alignment affirms the conceptual coherence of Infinite Hope and expands its utility (Sinek, 2019; Snyder et al., 2002). The framework builds on established psychological theory while introducing a values-based model of agency and purpose designed for young adults navigating uncertainty and transition.

2.3 Literature Integration and Theoretical Anchoring

Hope Theory anchors infinite Hope in psychological theory. Snyder (1994) and later Snyder et al. (2002) defined hope as a cognitive-motivational structure composed of three interrelated components: goal setting, pathway thinking, and agency. These elements enable individuals to envision meaningful futures and pursue them intentionally. Prolonged adversity often erodes hope among disconnected emerging adults. However, research demonstrates that targeted interventions restoring goal clarity, enhancing adaptive thinking, and fostering self-efficacy can rebuild hope and renew purposeful engagement (Gallagher & Lopez, 2009; Marques et al., 2011; Sinek, 2019; Valle et al., 2006).

Sinek's Infinite Mindset (2019), inspired by Carse's (2012) theory of finite and infinite games, adds philosophical and ethical depth to this model. Sinek identified five leadership practices: advancing a just cause, building trusting teams, embracing existential flexibility, learning from worthy rivals, and leading with courage. Each principle reinforces a dimension of Hope Theory (Snyder et al., 2002). Existential flexibility, for example, broadens pathway thinking by validating moral redirection. Leading with courage strengthens agency through value-aligned action. Advancing a just cause elevates goal setting into a collective, ethical endeavor.

Although Infinite Mindset lacks formal validation in developmental psychology, its philosophical clarity and alignment with Hope Theory and recent studies on values-based motivation underscore its relevance (Marques et al., 2011; Sinek, 2019; Snyder et al., 2002). Its core principles resonate with developmental priorities such as meaning-making, moral identity, and resilience in uncertainty. Researchers should prioritize psychometric development, mixed-methods testing, longitudinal analyses of goal persistence, emotional adaptability, and narrative repair. These methods offer the empirical tools necessary to test, refine, and validate Infinite Hope's theoretical claims across diverse developmental contexts.

2.4 Scope and Relevance of Literature

The literature reviewed spans developmental psychology, educational leadership, civic engagement, and youth development. This interdisciplinary foundation reflects the complexity of disconnection and the diverse strategies required for meaningful and sustainable re-engagement (Snyder et al., 2002). The review integrates foundational and emerging contributions to clarify how constructs such as hope, mindset, and identity operate within transformative interventions.

Table 5 provides a thematic summary of these key concepts, highlighting core propositions and areas of scholarly divergence. By organizing the literature into clear theoretical domains, the table underscores the framework's conceptual grounding and illuminates unresolved tensions in the field (Sinek, 2019; Snyder et al., 2002). This visual synthesis also affirms Infinite Hope's contribution to advancing integrated, forward-looking approaches to youth development.

Key theoretical models anchoring the Infinite Hope framework include Snyder's Hope Theory, Deci and Ryan's Self-Determination Theory (2000), Pekrun's Control-Value Theory (2006), Dweck's Growth Mindset (2016), and Sinek's Infinite Mindset (2019) (Fike & Mattis, 2023). Together, these models offer critical insights into how cognition, emotion, relational experience, and ethical direction shape engagement, agency, and resilience during transitional life stages.

Recent research has deepened the understanding of hope across multiple fields. Marques et al. (2011) introduced a structured intervention that cultivated future-oriented thinking among youth (Snyder et al., 2002). Hope et al. (2022) demonstrated that strong mentoring relationships can help restore direction and belief. Di Consiglio et al. (2025) found that mental simulations grounded in personal values can activate long-term goals. Shao (2025) explored the role of AI tools in enhancing students' motivation and emotional autonomy. Meanwhile, Nurmi (2005) identified key developmental transitions that shape how young people envision their futures over time.

These studies highlight that hope is not solely a matter of internal willpower. It takes root through a dynamic interplay of meaning, agency, and human connection (Sinek, 2019; Snyder et al., 2002). Affirming environments and inner empowerment cultivate hope in young adults. Infinite Hope builds on this foundation to guide disconnected emerging adults from a sense of disorientation toward a renewed sense of purpose. Young people are more likely to persevere and confidently move forward when identity and vision align.

Building on this conceptual foundation, this study uses an interdisciplinary literature review to explore how hope, agency, and purpose are framed within emerging adulthood (Marques et al., 2011; Sinek, 2019; Snyder et al., 2002). Rather than focusing on lived experience through primary data collection, the study synthesizes existing theoretical and empirical findings. Guided by the Infinite Hope framework, it examines how internal motivation and external context interact to influence future orientation. The following section outlines the research methods used to structure this integrative analysis.

3. Conceptual Integration

3.1 Empirical Grounding

A substantial body of research affirms the central role of hope in fostering positive developmental outcomes during emerging adulthood. Young people with elevated levels of hope show stronger academic performance, greater emotional regulation, and sustained persistence through adversity (Gallagher & Lopez, 2009; Marques et al., 2011; Snyder et al., 2002). These individuals express meaningful goals, identify multiple strategies for achieving them, and sustain the motivation for progress. For those experiencing disconnection, hope often diminishes, not because of an absence of aspiration, but in response to repeated systemic barriers that compromise their belief in future possibilities (Booker et al., 2022; Valle et al., 2006).

Recent empirical studies deepen this understanding and support key propositions within the Infinite Hope framework. Burrow et al. (2009) demonstrated that a strong sense of purpose enhances psychological resilience and goal-directed behavior in youth, affirming Infinite Hope's emphasis on courageous leadership and sustained agency. Marques et al. (2011) found that structured interventions increase future-oriented thinking and strengthen a sense of control, reinforcing the framework's focus on adaptive pathways and value-driven motivation. The philosophical propositions of Infinite Mindset and Sinek's (2019) assertion that purposeful leadership and moral clarity drive sustainable change further support these findings (Fike & Mattis, 2023).

Additional studies extend and refine these propositions. Hope et al. (2015) connected critical consciousness with purpose-driven action, showing that when young people align their goals with a just cause, their motivation and identity clarity increase. Booker, Brakke, and Pierre (2022) offered further evidence that identity-affirming supports lead to greater hope and persistence, reinforcing Infinite Hope's claim that personal goals gain power when linked to social purpose. Poteat et al. (2025) found that affirming peer spaces, such as Gender-Sexuality Alliance groups, promote agency and belonging. This idea aligns with the framework's emphasis on relational environments that cultivate leadership and reinforce direction (Marques et al., 2011; Sinek, 2019; Snyder et al., 2002).

These patterns provide conceptual scaffolds and open practical avenues for testing. The Infinite Hope model encourages researchers to explore original combinations of existing constructs. Researchers can use Snyder's State Hope Scale (1994) to assess baseline levels of goal-directed agency and pathways thinking. For constructs related to an infinite mindset, they may apply relevant tools in organizational psychology that emphasize purpose, values alignment, and ethical leadership. These tools function as interim proxies while Infinite Hope-specific measures continue to emerge (Sinek, 2019).

This body of work shows hope is not an isolated emotion or a static trait. Individuals cultivate hope through coherence of identity, alignment with deeply held values, and purposeful engagement in action (Sinek, 2019; Snyder et al., 2002). The Infinite Hope framework emphasizes that disconnected emerging adults do more than build skills. They reclaim belief, clarify their values, and align their direction with a sense of ethical purpose. Researchers can deepen this model by connecting hope assessments to longitudinal measures of identity development, moral leadership, and sustained purpose over time.

3.2 Integrated Model of Infinite Hope

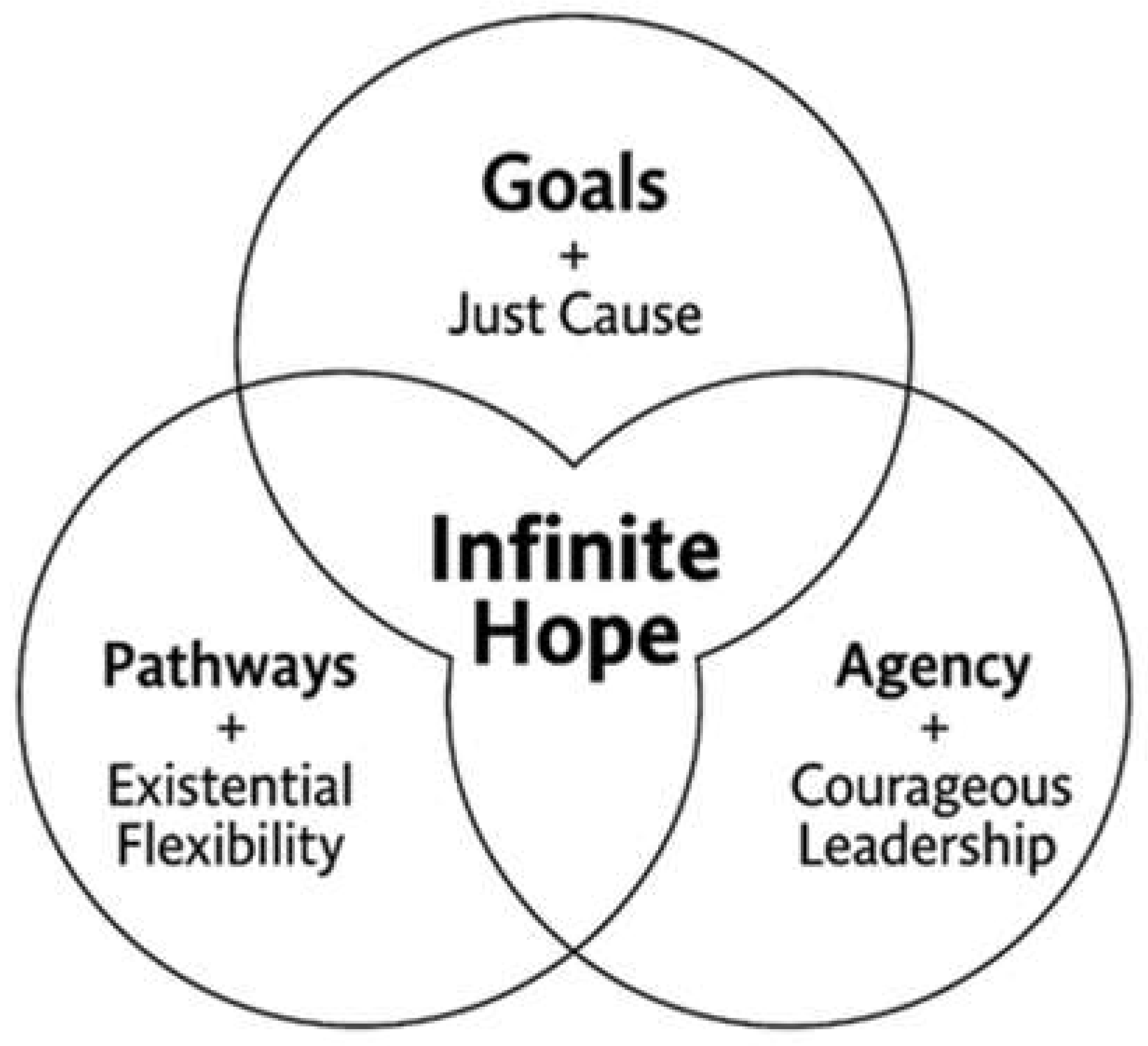

The Infinite Hope framework emerges from a foundation of empirical research and theoretical insight. It unifies two powerful developmental approaches: Snyder's cognitive theory of hope and Sinek's infinite mindset. They create a model that activates internal capacities and outward expressions of purpose-driven growth. The visual models provide a conceptual synthesis of this integration, showing how the core components of Infinite Hope interconnect and develop across time. Descriptions and interpretive captions for Figures 1 and 2 appear in Appendix A.

Figure 1 presents a three-circle Venn diagram that illustrates how the core elements of Snyder's theory—goals, pathways, and agency—intersect with Sinek's principles of the infinite mindset: just cause, existential flexibility, and courageous leadership (Sinek, 2019; Snyder, 2002). Each intersection transforms individual capacities into integrated strengths. For example, aligning goals with a just cause elevates them beyond personal ambition, imbuing them with ethical and communal significance. Purpose operates not just as a destination but as a compass, offering directional clarity grounded in values and future vision (Bronk et al., 2009; Yeager et al., 2014). Likewise, existential flexibility shapes adaptive pathways, empowering young people to revise strategies while staying rooted in long-term goals (Sinek, 2019; Snyder, 2002). Courageous leadership fortifies agency, allowing individuals to act with integrity amid fear or uncertainty (Donald et al., 2020; Dweck, 2016).

Adapted from Sinek (2019) and Snyder (2002).

This model shows how goals, pathways, and agency converge around an ethically sound purpose aligned with identity. Youth begin to align hope with deeper values and long-term vision. These intersections reveal more than conceptual compatibility; they generate developmental synergy. Each pairing enables hope to function as a coping mechanism and a transformative process rooted in core values and guided by vision (Sinek, 2019; Snyder, 2002). Hope shifts from a passive belief to an active, lived experience. This transformation becomes especially meaningful for emerging adults who navigate instability, disconnection, or marginalization. When immersed in these integrated frameworks, young people reinterpret their past, clarify their direction, and actively shape their future with confidence and conviction (Booker et al., 2022; Bronk et al., 2009).

One young adult, reflecting on the initial realization of this shift, might say, "I used to set goals without really knowing why. Now I know what matters to me, and that's what keeps me going." This statement shows an early stage of transformation, where new clarity of purpose grounds hope. As development progresses and self-understanding deepens, a more advanced insight may emerge. Another participant might explain, "I stopped chasing what looked good and started focusing on what felt right." This second reflection captures the internalization of purpose and identity alignment, demonstrating a more stable embodiment of Infinite Hope.

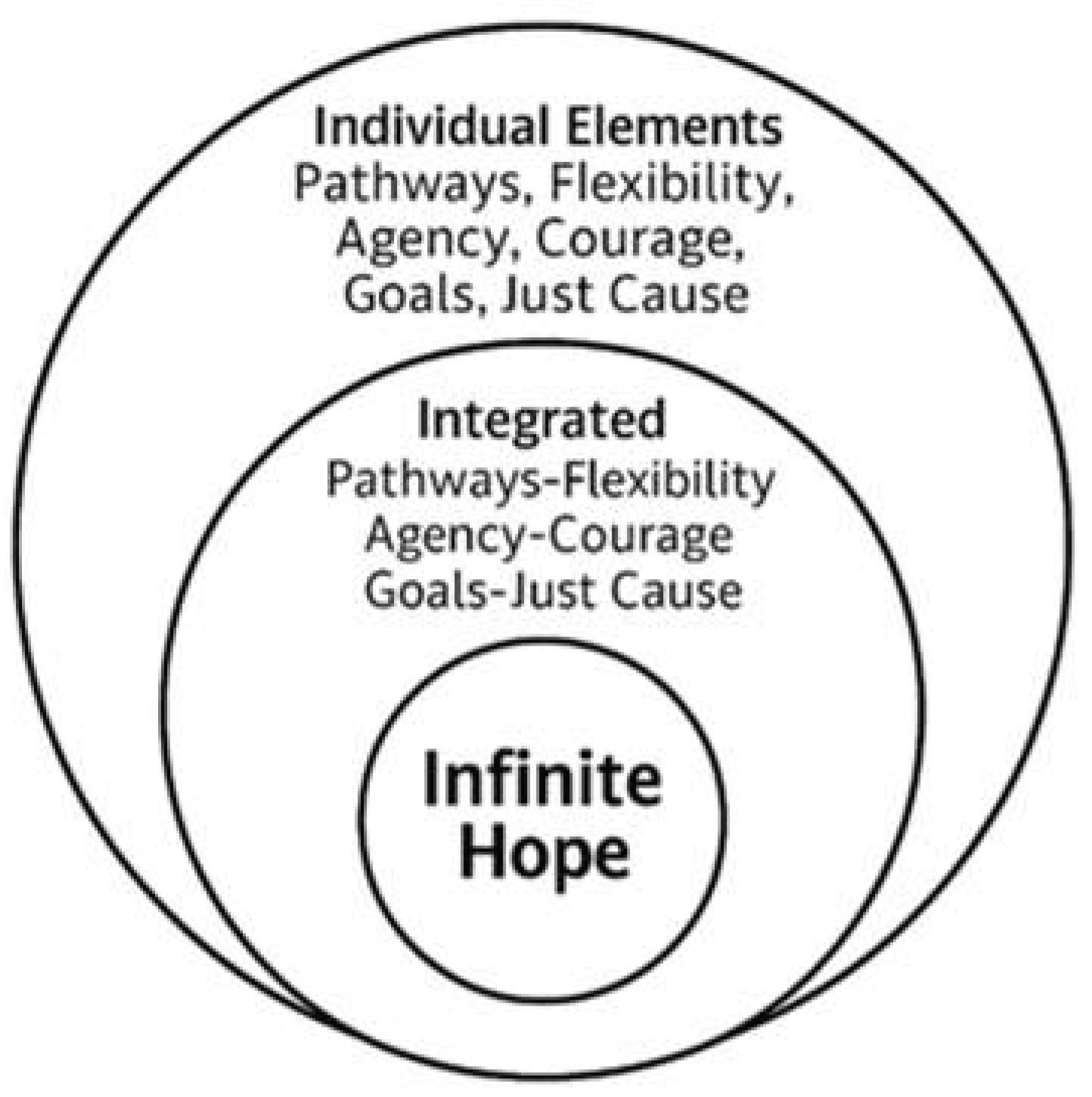

Figure 2 introduces a concentric circles model that maps the developmental progression of this integration. The outer ring identifies foundational skills essential to hope and mindset development—setting goals, imagining future possibilities, managing setbacks, and cultivating self-belief. These early competencies represent the beginning of intentional growth and motivational engagement. As individuals apply infinite mindset principles, these skills gain strength and flexibility. In the middle ring, youth shift from merely setting goals to grounding them in meaning. They demonstrate greater adaptability in their pathways and begin to lead themselves with courage and clarity. Infinite Hope is at the model's core, a stable internal state defined by identity alignment, ethical clarity, and consistent, values-driven action.

A young adult describing this evolution might say, "At first, I just wanted to finish something. But over time, I started thinking about who I want to become." This quote illustrates the transition from basic goal orientation to reflective identity development. Eventually, that transformation culminates in an empowered mindset, as expressed by another participant: "I realized I do not just want to get by. I want to live with purpose." Together, these reflections offer a narrative arc that traces the layered maturation of Infinite Hope.

Adapted from Sinek (2019) and Snyder (2002).

The concentric rings trace a developmental sequence from foundational habits to identity alignment. Growth strengthens when supported by emotional regulation, purpose, and adaptive flexibility.

Figure 2 portrays the layered development of Infinite Hope as a process that unfolds over time. The outer ring secures initial momentum through goal setting, future envisioning, and intrinsic motivation. These foundational components reflect well-established elements of hope theory and purpose development (Bronk et al., 2009; Snyder et al., 2002). The middle ring deepens those capacities through infinite mindset principles—adaptability, long-term vision, and values-based action (Sinek, 2019). As youth embody these practices, they draw closer to Infinite Hope at the center.

At its core, Infinite Hope does not emerge as a sudden realization or isolated moment. It grows through reflection, disciplined practice, and meaningful engagement. Young people build this state when their environments move beyond encouragement, providing structured opportunities for self-discovery, narrative reconstruction, and identity alignment. As they move through each layer, developing skills, embracing purpose, and leading with courage, they stop viewing themselves as disconnected and begin authoring their future with agency and clarity. Infinite Hope becomes a lived, durable reality anchored in purpose, directed by vision, and powered by intentional action (Burrow et al., 2009; Dweck, 2016). An example of this shift might be: "I used to wait for someone to believe in me. Now I am learning to believe in myself first."

3.3 Implications for Practice and Program Design

The Infinite Hope framework urges youth practitioners to rethink how they connect with young people who have become disengaged from education, employment, or their communities (Sinek, 2019; Snyder et al., 2002). Authentic engagement does not begin with control or compliance. It begins with meaning. Programs must move past transactional models and instead cultivate belief, reinforce agency, and center purpose. These conditions restore a young person's relationship with their future.

Evidence supports this direction. Hope et al. Marques et al. (2015) demonstrated that surrounding young people with emotionally present and structurally supportive adults fosters greater clarity and momentum in their development (2011; Snyder et al., 2002). These were not always formal mentors. The most effective adults showed up consistently, listened with care, and made space for growth. Poteat et al. (2025) found that affirming peer environments, particularly those built around shared identities, enhanced agency and strengthened belonging. Donald et al. Deci and Ryan (2020) further showed that nurturing internal motivation through autonomy and connectedness makes individuals more likely to sustain purposeful action. These findings confirm that hope is not self-generated. It is relational. Young people's hope grows when others see, affirm, and support them.

Programs informed by Infinite Hope must center cultural identity and validate lived experience (Sinek, 2019; Snyder et al., 2002). Whether through youth-led organizing, supportive peer spaces (Poteat et al., 2025), or trauma-attuned learning settings (Hope et al., 2015), these environments help youth attach meaning to their narratives. They do more than deliver information. They create belonging and spark reflection. In these spaces, purpose begins to take root.

This model also necessitates rethinking how we define and evaluate success (Sinek, 2019; Snyder et al., 2002). Conventional outcome indicators, such as attendance, credential attainment, and program completion, offer only a superficial measure of developmental progress. The Infinite Hope framework calls for a deeper assessment approach that captures internal transformation, including agency, goal clarity, value alignment, and purposeful action. Marques et al. (2011) found that programs grounded in future-oriented motivation significantly enhance youth self-efficacy and persistence. Booker et al. (2022) similarly emphasized that re-engagement is most effective when rooted in purpose and psychological empowerment, particularly for youth navigating systemic disconnection. Yeager et al. (2014) further confirmed that when young people perceive their environments as respectful and affirming, they are more likely to internalize constructive feedback and sustain meaningful growth.

Bringing Infinite Hope into practice means translating each component into a strategy (Sinek, 2019; Snyder et al., 2002).

Table 6 offers that map. It links principles from Hope Theory and Infinite Mindset to practical coaching, instruction, and engagement methods. This framework provides not just a theory but a direction. A way to walk with youth as they reclaim the future on their terms.

Table 6 presents programmatic strategies that operationalize the Infinite Hope framework by connecting constructs from Hope Theory and Infinite Mindset to specific applications in practice (Sinek, 2019; Snyder et al., 2002). Each pairing of constructs guides actionable strategies across program design and facilitation. Practitioners can use this structure to embed Infinite Hope into their engagement models, fostering sustained connection, reflection, and future orientation.

Programs seeking to re-engage disconnected youth must prepare staff for more than instructional delivery. Youth workers become developmental guides, modeling purpose, supporting agency, and embodying the integrity they hope to foster (Bridgeland & Milano, 2012; Fike & Mattis, 2023; Sinek, 2019). To serve in this capacity, practitioners need structured, experience-based professional development rooted in youth identity, resilience, and the integrated principles of the Infinite Hope framework (Arnett, 2000; Snyder et al., 2002). When organizations cultivate this capacity and promote a reflective, purpose-aligned culture, they strengthen their ability to activate Infinite Hope. Staff become co-constructors of growth, translating core concepts into relational interactions that help youth reclaim their future with clarity and direction. For an outline of recommended training components, see Appendix B.

Professional learning should be ongoing. It must include robust onboarding and continuous development through reflective practice. Training in trauma-responsive communication, cultural humility, motivational interviewing, and purpose-based advising deepens practitioner impact (Donald et al., 2020; Hope et al., 2015; Lerner et al., 2021; Marques et al., 2011). When adults model key mindsets (e.g., adaptability, long-range thinking, and courage), they reinforce the qualities they seek to cultivate in young people.

The success of Infinite Hope depends on staff who demonstrate and embody its principles in daily practice (Sinek, 2019; Snyder et al., 2002). Rather than follow scripts, practitioners build trust through relational presence and developmental responsiveness. Emotional availability, deep listening, and belief in youth capacity support psychological transformation. Studies link these relational behaviors to increased hope, purpose, and persistence in vulnerable populations (Cheavens et al., 2006; Donald et al., 2020; Guthrie et al., 2014; Hope et al., 2015). Therefore, investing in staff is not supplemental but foundational for organizations implementing Infinite Hope. The model lives or falters in how adults show up. Youth are likelier to do the same when they lead with clarity, conviction, and care.

Core competencies should include values clarification, identity exploration, purpose facilitation, and narrative listening (Hope et al., 2015; Snyder et al., 2002). These skills enable staff to support emerging adults as they examine goals, interpret experience, and shape self-understanding. Programs should also incorporate structured journaling as a reflective tool to deepen this developmental process. Journaling gives voice to emerging adults, allowing them to critically engage with their past, articulate present intentions, and imagine future possibilities (Bronk et al., 2009; Dillon, 2010; Kerpelman et al., 1997; Layland et al., 2018; Mason, 2019). Reflective writing enhances metacognitive awareness and narrative coherence, core components of psychological resilience and the development of hope (Bronk et al., 2009; Snyder et al., 2002). Thoughtful questions and emotionally safe environments, fostered by youth workers, help transform past disruption into purposeful engagement. For aligned journal prompts that support this process, see Appendix C.

4. Discussion

4.1 Rethinking Disconnection as Developmental Interruption

The Infinite Hope framework reconceptualizes disconnection, portraying it not simply as a lapse in academic or professional engagement but as a disruption in developmental momentum and identity formation. Rather than locating failure within the individual, Infinite Hope identifies disconnection as a systemic interruption of the psychological resources that sustain motivation, purpose, and agency. This shift clarifies why conventional re-engagement strategies that emphasize behavioral compliance or credential attainment often yield limited success. Although job placement and educational advancement remain important, they fail to address the underlying narrative fractures that many disconnected youth experience (Booker et al., 2022; Flennaugh, Stein, & Andrews, 2017).

Disconnection fractures the continuity of a young person's story of self, interrupting their sense of direction and diminishing their belief in possible futures. These fractures compromise the core capacities emphasized in Hope Theory and Infinite Mindset—agency, goal clarity, and future orientation—essential to resilient development (Sinek, 2019; Snyder et al., 2002). Reconnection requires a relational and narrative process, not merely a procedural one. It thrives in environments that validate lived experiences, support identity reintegration, and promote critical reflection (Kerpelman et al., 1997; Dillon, 2010). Effective programs reject prescriptive mandates and instead cultivate belonging, purpose, and emotional safety—conditions that restore belief in one's capacity to act (Napier et al., 2024).

4.2 Reclaiming Motivation and Forward Momentum Through Hope

Hope Theory powers the Infinite Hope model by explaining how young people shift from disorientation to goal-directed momentum. Instead of prioritizing compliance with external benchmarks, Hope Theory focuses on internal mechanisms: the ability to set goals, construct pathways, and sustain belief in one's capacity to reach them (Snyder et al., 2002). When these elements align, hope strengthens and self-concept evolves.

Within the Infinite Hope framework, programs nurture these dynamics by offering structured yet flexible tools (e.g., narrative reframing, purpose mapping, and scaffolded goal setting) that help participants reclaim authorship of their lives. These strategies gain transformative power in environments that support emotional regulation, peer validation, and reflective growth (Marques et al., 2011; Layland et al., 2018). Such practices reinforce a sustained sense of agency by affirming that one's actions carry purpose and contribute to future possibilities.

Infinite Hope frames hope not as a fleeting emotional state but as a renewable developmental capacity. Practitioners can teach, model, and expand hope through consistent, supportive relationships. When young people reinterpret past interruptions as sources of insight rather than failure, they reorient themselves toward possibility and direction (Cheavens et al., 2006; Bronk et al., 2009). In this way, hope serves as both a bridge and a catalyst, linking disrupted experiences to renewed purpose and equipping young people with the mindset and tools to build a coherent and empowered future.

4.3 Navigating Youth Agency in the Age of AI and Digital Systems

Digital environments increasingly influence how emerging adults construct identity, develop agency, and shape future goals. Infinite Hope responds to this evolving landscape by addressing the dual role of artificial intelligence (AI) and algorithmic systems in supporting or constraining youth autonomy, purpose, and decision-making. For many young people, self-expression and goal formation now unfold in ecosystems driven by data, behavioral prediction, and curated feedback loops. These systems can narrow vision by reinforcing conformity or open new pathways for exploration, reflection, and growth (Baker & Siemens, 2014; Layland et al., 2018).

Shao (2025) demonstrates that AI-powered learning environments can enhance motivation and self-efficacy when prioritizing user control, relevance, and transparent feedback. Features allowing emerging adults to monitor their progress, engage in goal-aligned tasks, and receive responsive input increase their sense of agency and future orientation. Similarly, when digital tools invite critical engagement rather than passive consumption, they help sustain long-term learning and psychological investment (Donald et al., 2020).

However, digital engagement must move beyond questions of access or device availability. Infinite Hope encourages programs to build digital discernment - the capacity to question how digital systems shape beliefs, filter opportunities, and impact identity formation. Youth must become users and interpreters of their digital environments, learning to recognize how data-driven tools can support or suppress their development. This perspective aligns with Turin et al. (2023), who conceptualize community engagement, including digital participation, as an infinite game defined not by outcomes but by sustained meaning-making and iterative learning.

By framing digital interaction as part of an ethical and identity-shaping process, Infinite Hope expands its commitment to youth agency. Programs should integrate reflective digital literacy practices, including journaling, narrative creation, and goal-mapping within online spaces. These practices allow youth to make sense of their digital lives in ways that affirm dignity, purpose, and direction (Dillon, 2010; Kerpelman et al., 1997). In doing so, Infinite Hope reinforces its core proposition: that youth agency must remain adaptive, reflective, and future-oriented.

4.4 Infinite Mindset: Shaping Identity Through Enduring Purpose

The Infinite Mindset offers a strategic lens for supporting disconnected emerging adults in sustaining identity development and purposeful engagement amid uncertainty. While Snyder’s Hope Theory explains how young people move forward through agency, pathways, and goals, the Infinite Mindset clarifies why they persist. It guides young people toward a future grounded in ethical clarity and enduring meaning rather than short-term benchmarks (Snyder et al., 1991; Sinek, 2019).

Sinek's five principles address key developmental needs. A just cause encourages youth to construct future-oriented goals that extend beyond survival and foster a sense of contribution (Bronk et al., 2009; Yeager et al., 2014). Trusting teams foster psychological safety and connection, essential for youth navigating instability and marginalization (Poteat et al., 2025). Existential flexibility enables youth to adapt purposefully, reinforcing autonomy and strategic growth (Dennis & Vander Wal, 2010). Learning from rivals cultivates humility, reflection, and resilience through relational comparison (Nairn et al., 2025). Leading with courage affirms agency and nurtures moral identity formation in the face of social and emotional risk (Schwarzer & Jerusalem, 1995; Walumbwa et al., 2008).

Youth-driven contexts reveal the transformative power of these principles. Nairn et al. (2025) observed how youth-led activist collectives fostered ethical self-authorship, allowing emerging adults to align actions with beliefs and reframe identity through civic purpose. Similarly, Poteat et al. (2025) documented how participation in identity-affirming spaces increased well-being, hope, and belonging. These environments function as transformative ecosystems that help youth cultivate self-concept, reconstruct aspirations, and internalize agency and social contribution (Fike & Mattis, 2023; Poteat et al., 2025).

Practitioners who cultivate an Infinite Mindset help youth sustain hope by grounding it in narrative coherence and ethical direction. Rather than replacing Snyder’s goal-agency-pathways triad, the Infinite Mindset expands it into a broader ethos of intentional living. Infinite thinking shifts resilience from a reactive coping mechanism into a proactive strategy rooted in long-range values, strategic flexibility, and identity alignment (Dennis & Vander Wal, 2010; Luyckx et al., 2008; Sinek, 2019). This mindset transforms setbacks into opportunities for growth rather than interpreting them as evidence of inadequacy (Booker et al., 2022; Yeager et al., 2014).

Disconnected youth gain strength from adopting an infinite mindset. It provides a lasting foundation for meaning making, anchors goals in values, supports intentional decision making, and nurtures narrative healing across past, present, and imagined futures (Bronk et al., 2009; Yeager et al., 2014). As young people lead themselves through uncertainty with clarity, conviction, and courage, they shift from reactive persistence to purpose-driven transformation. In doing so, they redefine their identities with agency and sustain hope with integrity.

4.5 From Framework to Practice: Integrating Hope and Mindset for Transformative Growth

Infinite Hope offers a forward-thinking conceptual framework grounded in positive youth development, purpose theory, and hope theory. While its foundations draw from research identifying the psychological strengths young people need to thrive, such as agency, self-determination, and future orientation (Bronk et al., 2009; Marques et al., 2011; Snyder et al., 1991), the model pushes beyond traditional applications. Unlike initiatives limited to adolescents in school environments, Infinite Hope's design meets the specific needs of older disengaged youth and emerging adults who have disengaged from or been excluded by conventional developmental pathways. Its emphasis on critical reflection, narrative identity, and adaptive purpose aligns with the complexities faced by disconnected young people navigating structural barriers and disrupted transitions. Still, like any evolving model, Infinite Hope requires further testing, refinement, and validation. Much of the current support comes from qualitative studies and pilot programs that, while rich in insight, may not generalize across diverse populations or systems (Bintliff, 2011; Booker et al., 2022).

Rather than dismiss these limitations, future researchers should build on early findings by addressing measurement validity, cultural responsiveness, and practitioner interpretation issues. Standardized tools and culturally adaptive approaches can enhance the model's scalability and fidelity across varied institutional and community settings. Without such tools, programs risk applying Infinite Hope inconsistently or overlooking its developmental depth.

Expanding the empirical base through longitudinal, cross-cultural, and participatory studies can help clarify how Infinite Hope performs across contexts and developmental stages (Arnett, 2000; Bronk et al., 2009). Hope and purpose operate differently depending on youth access to relationships, resources, and community networks (Brookings, 2022; Sulimani Aidan & Melkman, 2022). Programs should therefore tailor implementation to reflect local needs and the diverse identities of young people (Flennaugh et al., 2017).

Emerging adults experience development in ways that go far beyond job placement or credential attainment. While these external benchmarks hold some value, they often overlook the deeper internal shifts that drive sustained growth—changes in self-concept, cognitive flexibility, future orientation, and moral clarity. Researchers must adopt a broader evaluative lens to capture these processes. Appendix E provides a validated crosswalk of interim instruments aligned with each dimension of the Infinite Hope framework. These include the Revised Youth Purpose Survey (Bronk et al., 2009), which measures clarity and commitment to personally meaningful goals; the Self-Transcendent Purpose for Learning Scale (Yeager et al., 2014), which captures motivation rooted in contribution; the Hope Scale subscales for pathways and agency thinking (Snyder et al., 1991); the General Self-Efficacy Scale (Schwarzer & Jerusalem, 1995), which assesses belief in one's capacity to act; the Cognitive Flexibility Inventory (Dennis & Vander Wal, 2010), which measures the ability to adapt and reframe; and the Dimensions of Identity Development Scale (Luyckx et al., 2008), which evaluates identity exploration and coherence. Practitioners and researchers should use Appendix E not as a rigid checklist, but as a flexible guide to select and triangulate measures based on context and developmental goals. When paired with reflective interviews, narrative journals, or participatory inquiry methods, these tools reveal the internal architecture of hope as it develops in real time, layered, contextual, and transformative.

The framework can also benefit from deeper integration with broader developmental theory. Although Infinite Hope builds on Snyder's hope theory and Carse's concept of infinite games (Carse, 2012; Sinek, 2019), it must more fully align with models such as Arnett's theory of emerging adulthood and identity development frameworks that emphasize culture and context (Arnett & Jensen, 2014). Constructs like existential flexibility and clarity of purpose require sharper operationalization to ensure consistent application to research and practice (Bronk et al., 2009).

Qualitative and mixed methods research provides valuable pathways to explore Infinite Hope in ways that center the youth voice. Narrative interviews, reflective journaling, and participatory inquiry reveal how young people understand disconnection, hope, and transformation (Bintliff, 2011; Gómez & Cammarota, 2022). These approaches help adapt the model to reflect the lived experience of diverse youth while honoring the internal changes that often precede external progress.

Longitudinal studies remain essential to showing how shifts in mindset and hope influence long-term outcomes such as education, employment, civic engagement, and well-being (Lerner et al., 2021; Napier et al., 2024). Following emerging adults over time reveals patterns of change in agency, identity, and purpose, along with the protective factors that support growth despite adversity (Arnett, 2000).

As Infinite Hope evolves, researchers and practitioners must recognize the cultural variation in how young people experience and express hope (Fike & Mattis, 2023; Hope et al., 2015). Implementation in under-resourced settings requires intensive strategies anchored in relationship building, mentorship, and ethical presence. While effective, these efforts often depend on local capacity and institutional investment (Bridgeland & Mason Elder, 2012; Guthrie et al., 2014). Without clear guidance and training, adults may unintentionally misapply the framework as a compliance tool rather than as a means of youth empowerment (Flennaugh et al., 2017).

These challenges underscore, not undermine, the potential of Infinite Hope. They highlight the need for continued research, collaborative experimentation, and youth co-design. Each story and study adds to the framework's depth, creating a richer tool for re-engaging disconnected youth. As Arnett (2000) emphasized, emerging adulthood marks a period of possibility. Infinite Hope expands that possibility by equipping young people to imagine, construct, and pursue futures grounded in agency, purpose, and integrity. Appendix F outlines a research agenda featuring testable hypotheses aligned with the framework's core dimensions.

5. Conclusions

Infinite Hope offers more than a synthesis of theory. It presents a forward-looking vision for how emerging adults can reclaim agency, rebuild purpose, and navigate disconnection with clarity, resilience, and conviction. This manuscript has demonstrated that disconnection is not merely the absence of credentials or employment. It represents a disruption in developmental progression that interrupts identity formation, future orientation, and the ability to act with purpose and direction. Rather than pathologizing this interruption, the Infinite Hope framework reframes it as an inflection point, a moment that, with the proper support and opportunity, can spark profound growth, meaningful renewal, and intentional re-engagement.

Integrating Snyder's Hope Theory with Sinek's Infinite Mindset allows Infinite Hope to offer both the psychological infrastructure and the values-based worldview necessary for sustained transformation. The model draws strength from goal setting, agency, and pathways thinking, the core tenets of psychological hope that empower youth to take intentional steps toward growth. When reinforced by existential flexibility, courageous leadership, and a just cause, these elements expand individual capacity into collective purpose. This integration fosters an ethical and enduring foundation that supports emerging adults as they navigate challenges, reframe disruption, and pursue long-term personal and social development.

Infinite Hope also recognizes that environments shape outcomes. Emerging adults require more than isolated interventions. They thrive within ecosystems of trust, cultural affirmation, and opportunities for narrative repair. Programs grounded in this framework create spaces where youth feel safe to explore identity, express vulnerability, and connect experiences with future aspirations. These environments affirm identity, support reflective growth, and foster belonging and self-discovery. As a result, they move beyond behavior management and into the realm of transformational, youth-centered support that affirms potential and builds capacity for sustained engagement.

This model urges educators, practitioners, researchers, and policymakers to transform the approach to re-engagement by shifting focus from transactional outcomes to developmental growth. Measuring success requires attention to more than employment or course completion; it calls for recognizing the presence of purpose, the clarity of personal vision, and the motivation young people demonstrate as they move through challenges. When programs create environments that affirm identity, foster reflection, and build agency, young people gain the tools to shape their own stories with intention and confidence. Transformation takes root when youth recognize their value, trust their voice, and act purposefully.

To support this paradigm shift, several concrete policy and programmatic recommendations emerge:

Integrate Hope-Centered Assessments: Adopt tools that measure agency, purpose, and cognitive flexibility alongside traditional academic or workforce metrics.

Fund Ecosystemic Youth Support Models: Prioritize funding for programs that create consistent, culturally affirming, and developmentally supportive environments.

Incentivize Reflective Pedagogies: Support professional development for educators and youth practitioners in narrative-based methods, trauma-informed practice, and identity-affirming curricula.

Embed Purpose-Building in Workforce Programs: Ensure that job training and credentialing initiatives include goal-setting, leadership, and personal narrative development modules.

Promote Cross-Sector Collaborations: Encourage education, workforce, mental health, and justice systems to align around integrated re-engagement strategies centered on Infinite Hope principles.

Infinite Hope creates the conditions for authentic transformation. The framework confronts the complexity of disconnection while advancing the belief that every young person can re-engage and grow. It centers emerging adults not on what they lack, but on what they can cultivate when supported with the tools, relationships, and beliefs that align with their strengths and potential. By recognizing the value in lived experience and affirming the capacity for change, Infinite Hope helps youth reconnect with their goals, redefine their identity, and step into a more purposeful future. More than a framework, Infinite Hope serves as an invitation to imagine boldly, design intentionally, and walk beside young people as they build lives they can both envision and lead with confidence.

Researchers should conduct future studies and pilot programs to test the Infinite Hope framework across diverse community contexts. Researchers and practitioners can refine the model's real-world application and scale its transformative potential by examining how hope and an infinite mindset interact across time, identity groups, and support systems.