1. Introduction

Human cognition and affect frequently oscillate between opposite extremes. Under stress, people may view themselves or others as entirely good or bad, swing from rigid self-control to complete chaos, or demand absolute certainty before action (O’Connor et al., 2025). Such dichotomous thinking simplifies reality at the cost of flexibility and often underlies mood instability, problematic relationships, and fragmented self-image (Yu, 2016; Astle et al., 2022).

A growing literature across psychoanalysis, Gestalt therapy, and contemporary integrative psychotherapy describes how psychological health requires reconciling opposing forces. Freud (1896) and Anna Freud (1936) detailed ego defenses that unconsciously distort perception to relieve anxiety, often producing one-sided views. Klein (1946) highlighted splitting, the black-and-white categorization of people and events. Jung (1921) formulated the principle of enantiodromia, observing that a force pushed to excess tends to generate its opposite. Gestalt theorists later described creative indifference, the capacity to remain at the “zero-point” between polarities and flexibly engage either side (Perls, 1973; Zinker, 1977; Brownell, 2010). More recently, dialectical behavior therapy (Linehan, 2015) teaches clients to access a wise mind that integrates emotion and reason.

Despite these advances, an overarching framework that unifies these insights and translates them into practical clinical mapping has been lacking. To address this gap, the present article elaborates the Mechanism of Differentiating Extremes in Psychological Attention—a novel, integrative model that conceptualizes mental processes along dynamic axes of attention with two distorted poles and a central architectural center of integration.

The aims of this article are threefold:

Theoretical integration – to synthesize classic and modern concepts of psychological polarities into a single, testable model.

Clinical mapping – to present a Dictionary of Coherence, a structured taxonomy of common psychological axes with their negative and positive poles and balanced centers.

Therapeutic application – to show how differentiating and integrating extremes can guide assessment and interventions across modalities.

This introduction frames the study within a trans-diagnostic, dimensional view of psychopathology (Astle et al., 2022), laying the conceptual groundwork for the methods, findings, and implications detailed in the following sections.

2. Materials and Methods

2.1. Conceptual Design

This article develops a conceptual, integrative framework rather than reporting empirical data. Following recommended procedures for theory-building in psychology (Jaakkola, 2020), we used a conceptual synthesis method:

- (1)

Mapping the domain—we reviewed classic and contemporary literatures on dichotomous thinking, defense mechanisms, integration of opposites, and transdiagnostic psychotherapy.

- (2)

Extracting key constructs—we identified recurring concepts describing how psychological attention oscillates between poles and how integration occurs.

- (3)

Constructing a unifying model—we organized these constructs into an explanatory mechanism termed the Mechanism of Differentiating Extremes in Psychological Attention.

2.2. Literature Sources

Primary theoretical sources included classical psychoanalysis (Freud, 1896; Freud, 1936), object-relations theory (Klein, 1946; Kernberg, 1975), Jungian psychology (Jung, 1921; Morin, 1993), Gestalt therapy (Perls, 1973; Zinker, 1977; Brownell, 2010), and dialectical behavior therapy (Linehan, 2015). We also consulted modern empirical work on defense mechanisms (Vaillant, 1992; Castellani et al., 2021), transdiagnostic models (Astle et al., 2022), and polarity management (Johnson, 1992). Additional references were drawn from recent scholarship on coherence, metacognition, and mindfulness as they relate to integrating opposites.

2.3. Model Construction

Using thematic coding of these sources, three interdependent constructs were derived:

- (1)

Axis of attention – a continuum on which mental focus moves between two distorted poles (negative and positive) and a balanced center.

- (2)

Architectural center – a dynamic locus of psychological coherence and integration, comparable to the observing ego or wise mind (Linehan, 2015).

- (3)

Dictionary of Coherence – a taxonomy of key psychological axes (e.g., fear–recklessness, grandiosity–self-loathing) specifying minus pole, center, and plus pole.

The model was iteratively refined by comparing it to clinical vignettes, published case studies, and existing integrative frameworks such as transference-focused psychotherapy and Internal Family Systems.

2.4. Application to Clinical Practice

To demonstrate utility for mental health professionals, we developed mapping and intervention guidelines. These include polarity profiling, identification of dominant defenses (splitting, denial, projection), and therapeutic strategies such as Gestalt two-chair dialogues, mindfulness practices, and cognitive restructuring. Each strategy was analyzed in relation to its capacity to foster differentiation (clear recognition of extremes) and integration (movement toward the architectural center).

2.5. Ethical and Scholarly Considerations

Because no new human or animal data were collected, formal ethics approval was not required. All referenced works are cited in accordance with the European Journal of Investigation in Health, Psychology and Education guidelines, using the (Name et al., Year) style.

3. Results

This section presents the proposed Mechanism of Differentiating Extremes in Psychological Attention, an integrative model designed to explain, map, and therapeutically address polarized psychological states. The findings are organized into (i) the model’s key constructs, (ii) the Dictionary of Coherence, and (iii) illustrative case-based examples.

3.1. Core Constructs of the Model

3.1.1. Axis of Attention

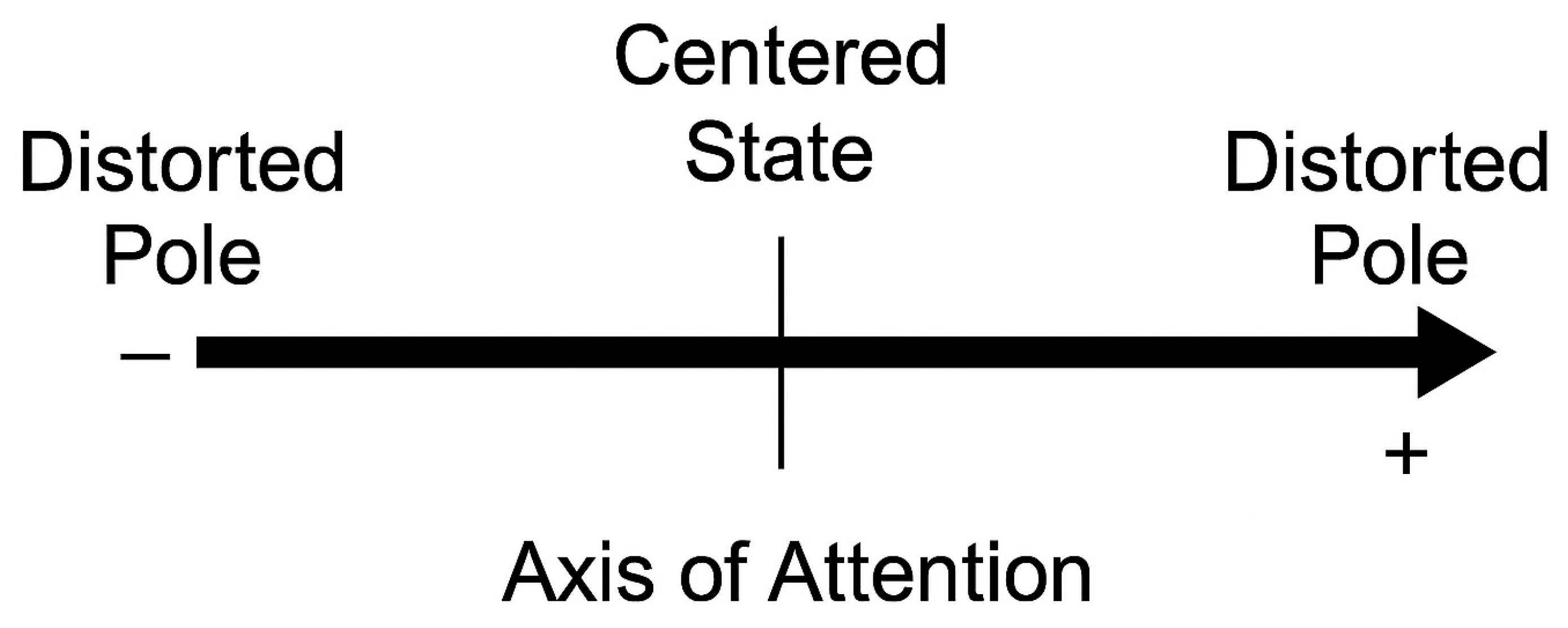

The axis of attention represents a continuum of experience along which mental focus shifts. Each axis is defined by two distorted poles—a negative (–) and a positive (+)—that represent exaggerated, one-sided states, and a balanced center where the strengths of both poles are integrated (

Figure 1). Psychological symptoms frequently arise when attention becomes fixed at one pole or oscillates between them (Jung, 1921; O’Connor et al., 2025). For example, on the fear–courage continuum, the –pole is paralyzing fear, the +pole is reckless denial of danger, and the center is courageous prudence.

3.1.2. Architectural Center

The architectural center is the system’s organizing locus of integration and coherence. Comparable to the observing ego in psychodynamic theory or wise mind in DBT (Linehan, 2015), it enables individuals to hold contradictory experiences simultaneously and to flexibly mobilize adaptive aspects of either pole as needed. Functionally, it provides stability against emotional storms and permits nuanced self-other representations (Winnicott, 1965; Vaillant, 1992).

3.1.3. Differentiation and Integration Mechanism

Healthy functioning requires first differentiating extremes—recognizing the partial truths and costs of each pole—and then integrating them in the center. Recurrent “flipping” from one pole to the other (enantiodromia) reflects failed differentiation (Jung, 1921). Mature coherence arises when both sides are acknowledged and synthesized into a higher-order, more complex position (Brownell, 2010; Herrera, 2017).

3.2. Dictionary of Coherence

To operationalize these ideas, a Dictionary of Coherence was developed (

Table 1). Each entry specifies:

▪ Negative pole (–): deficient or constrictive state

▪ Integrated center: balanced, adaptive synthesis

▪ Positive pole (+): excessive or overextended state

Key axes include:

▪ Fear and Courage (paralyzing fear – courageous prudence – reckless denial)

▪ Boundaries (enmeshment – healthy boundaries – rigid isolation)

▪ Contact and Attachment (emotional detachment – secure connection – clinging dependence)

▪ Self-Image (self-loathing – self-acceptance – grandiosity)

▪ Control and Agency (passivity – assertive agency – domineering control)

▪ Discipline and Relaxation (rigid perfectionism – flexible discipline – lax indulgence)

▪ Clarity and Uncertainty (dogmatic certainty – insightful openness – chronic confusion)

These axes are not exhaustive but illustrate the universality of psychological polarities. They serve as both assessment dimensions and therapeutic targets (

Table 1).

3.3. Illustrative Applications

To show the model in action, we examined common dualities.

▪ Good vs. Bad: Integration leads to a mature conscience that recognizes human complexity, reducing oscillations between idealization and devaluation (Klein, 1946; Castelloe, 2023).

▪ Strict vs. Soft: Balanced firmness with kindness supports sustainable self-discipline and authoritative parenting (Johnson, 1992).

▪ Clarity vs. Confusion: “Humble clarity” allows decisive action while tolerating ambiguity, a stance linked to intellectual humility and better decision making (O’Connor et al., 2025).

Each example demonstrates that true coherence is not a bland midpoint but a dynamic synthesis that retains the functional advantages of both extremes while avoiding their costs.

3.4. Clinical Vignettes

3.4.1. Vignette 1 – The Perfectionistic Graduate Student

Anna, 27, a doctoral candidate, sought help for chronic insomnia and mounting anxiety about her dissertation.

Trigger: minor feedback from her supervisor.

Pole fixation/oscillation: she instantly thought, “I’m a total failure,” and worked frantically for days (–pole: rigid perfectionism). After burnout she swung to the +pole of lax indulgence, binge-watching series and avoiding work.

Differentiation: through mindfulness and Gestalt two-chair dialogue, Anna articulated the voices of her inner critic and her exhausted self.

Integration: she learned to recognize the protective intention of each side and moved to a flexible discipline center—working in structured blocks with scheduled rest.

Outcome: steadier productivity, improved sleep, and a more compassionate self-view.

3.4.2. Vignette 2 – The Oscillating Romantic Relationship

Marco, 35, entered therapy after a breakup cycle that repeated every few months.

Trigger: ordinary disagreements with his partner.

Pole fixation/oscillation: he idealized new partners as perfect (+pole), then, when conflicts arose, flipped to total devaluation and abrupt withdrawal (–pole: detachment).

Differentiation: using Internal Family Systems techniques, Marco dialogued with the “Idealizer” and the “Fearful Withdrawer.”

Integration: he acknowledged each part’s function—seeking love and protecting against hurt—and developed secure connection, tolerating disagreements without breaking up.

Outcome: he maintained a stable, mutually satisfying relationship for over a year.

3.4.3. Vignette 3 – Executive with Control–Agency Polarities

Laura, 42, a senior executive, reported stress headaches and conflict with subordinates.

Trigger: a sudden market downturn.

Pole fixation/oscillation: she swung between helpless passivity (–pole) and domineering micromanagement (+pole).

Differentiation: cognitive restructuring and DBT “wise mind” exercises helped her recognize both poles as defenses against uncertainty.

Integration: Laura cultivated assertive agency, delegating effectively while staying informed.

Outcome: improved team morale, fewer physical symptoms, and more sustainable decision-making.

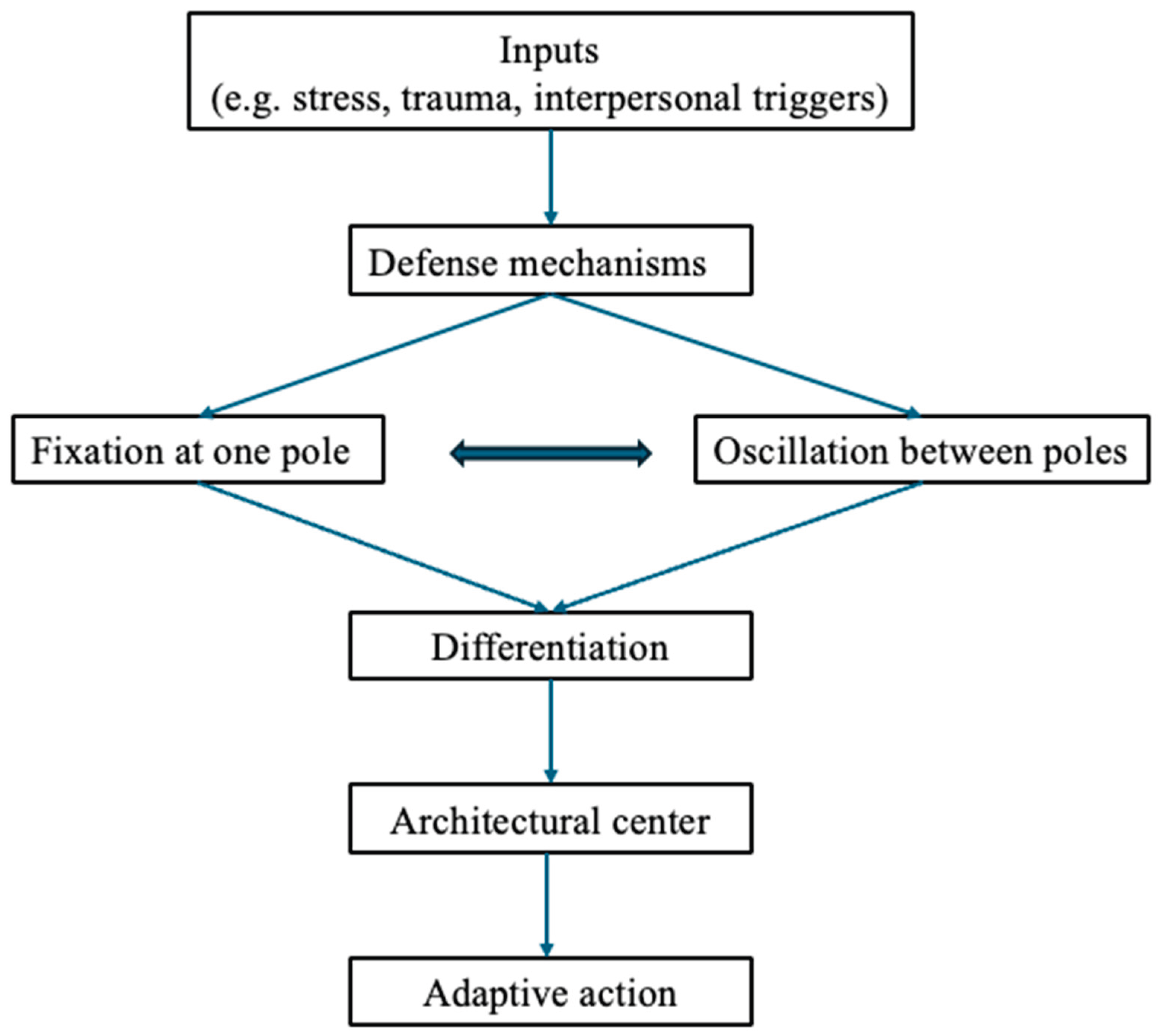

3.5. Mechanistic Summary

Taken together, these results indicate that many psychological problems—from anxiety disorders to interpersonal instability—can be conceptualized as maladaptive fixation at one pole or oscillation between poles. The mechanism of differentiating extremes provides both a diagnostic lens and a therapeutic roadmap, positioning the architectural center as the key to resilient, integrated functioning (

Figure 2).

4. Discussion

This study elaborates the Mechanism of Differentiating Extremes in Psychological Attention, a conceptual model for understanding how polarized mental states arise and how they can be therapeutically integrated. By combining psychoanalytic, Gestalt, Jungian, cognitive-behavioral, and mindfulness-based concepts, the framework addresses the pervasive problem of psychological polarization—the tendency to think, feel, and act at opposite extremes (

Table 2).

4.1. Relationship to Existing Theory

The model extends a long intellectual lineage. Freud (1896) and Anna Freud (1936) described ego defenses that distort awareness to manage anxiety, a process that can be reframed as fixation of attention at one pole. Klein (1946) and Kernberg (1975) analyzed how splitting prevents the integration of positive and negative self- and object-representations. Jung (1921) introduced enantiodromia, the tendency of overused attitudes to generate their opposite. Gestalt theorists (Perls, 1973; Zinker, 1977; Brownell, 2010) emphasized creative indifference, a point of equilibrium from which new synthesis can emerge. Dialectical behavior therapy (Linehan, 2015) similarly seeks the wise mind, integrating reason and emotion. The present framework gathers these insights into a single, dynamic mechanism—differentiating extremes and returning to an architectural center of coherence.

4.2. Clinical Applications

The clinical vignettes illustrate how the mechanism unfolds in practice. Across diverse contexts—academic perfectionism, romantic instability, and corporate leadership—clients presented with oscillations between poles. Therapeutic work began by naming and differentiating each pole’s motives and costs. As clients learned to hold these opposing truths simultaneously, they moved toward the architectural center, a balanced position that allows flexible, reality-based action. This conceptual mapping supports:

Case formulation – Practitioners can plot dominant polarities (e.g., fear–courage, control–agency) and identify the defenses maintaining them.

Treatment planning – Established modalities (Gestalt dialogue, DBT mindfulness, Internal Family Systems, cognitive restructuring) can be explicitly targeted to facilitate differentiation and integration.

Outcome measurement – Concepts such as coherence, flexibility, and oscillation frequency lend themselves to psychometric or ecological-momentary assessment.

4.3. Educational and Preventive Uses

Beyond clinical settings, the model provides a psychoeducational framework for schools, universities, and workplaces. Teaching young people to recognize polar thinking—for example, the all-or-nothing attitudes common in adolescence—can strengthen emotional regulation and conflict resolution skills. In organizational contexts, mapping team dynamics along relevant axes (e.g., caution–innovation) can foster collaborative decision-making and reduce polarization.

4.4. Cross-Cultural Relevance

Polarities such as dependence–independence or individualism–collectivism manifest differently across cultures. The model’s dimensional structure makes it adaptable: clinicians and educators can select culturally salient axes while retaining the same mechanism of differentiation and integration. Future research should explore cross-cultural validity, for instance comparing European, Asian, and African conceptualizations of balance and harmony.

4.5. Mechanistic and Research Implications

By locating polar fixation and oscillation at the heart of psychological distress, the model proposes measurable constructs including the degree of attentional bias toward one pole, rate of oscillatory shifts, and the stability of the architectural center. Operationalizing these constructs could lead to novel Polarity Integration Scales and enrich dimensional approaches to psychopathology (Astle et al., 2022). Randomized clinical trials might test whether therapies explicitly guided by the model yield stronger gains in coherence and flexibility than standard care.

4.6. Strengths and Limitations

A major strength is the unifying capacity of the mechanism: it explains how very different therapies can converge on a common goal of integrating opposites. The inclusion of concrete vignettes and the Dictionary of Coherence makes the model readily applicable.

The main limitation is that the present work is conceptual. Empirical validation, standardized measurement of “coherence,” and long-term outcome data are future priorities.

4.7. Future Directions

Research avenues include the development and psychometric validation of instruments to measure polarity fixation and integrative balance, clinical trials of interventions explicitly structured around differentiating extremes, and cross-cultural and lifespan studies to examine universality and cultural specificity.

5. Conclusions

This article advances a unifying framework for mental health practice and research—the Mechanism of Differentiating Extremes in Psychological Attention. The model explains how attention can become fixated at distorted poles or oscillate between them, creating the symptomatic swings seen in anxiety, mood, and personality disorders. It introduces three interlinked constructs: (1) Axis of attention: a continuum between negative and positive extremes; (2) Architectural center: the dynamic locus of coherence that reconciles opposites; (3) Dictionary of Coherence: a clinical map of common psychological axes with minus pole, center, and plus pole.

Through these concepts, diverse therapeutic methods—psychodynamic, Gestalt, cognitive-behavioral, dialectical—can be understood as different routes to the same fundamental goal: differentiating extremes and integrating them within a coherent self. The implications extend beyond psychotherapy. The model provides a conceptual scaffold for psychoeducation, resilience-building in schools and workplaces, and cross-cultural mental health promotion.

While the framework is conceptual and requires empirical validation, it offers testable hypotheses and measurable outcomes such as coherence and flexibility. In an era marked by polarization and fragmentation, cultivating the ability to integrate opposing tendencies is essential for personal well-being and social harmony. By emphasizing dynamic balance over rigid neutrality, this approach highlights that psychological health is not found at the extremes but in the creative synthesis at the center

Author Contributions

Conceptualization, M.S.; methodology, M.S.; software, M.S.; validation, M.S.; formal analysis, M.S.; investigation, M.S.; resources, M.S.; data curation, M.S.; writing—original draft preparation, M.S.; writing—review and editing, A.S.P.M.A.; visualization, A.S.P.M.A.; supervision, A.S.P.M.A.; project administration, M.S. All authors have read and agreed to the published version of the manuscript.

Funding

This research received no external funding.

Institutional Review Board Statement

Not applicable.

Informed Consent Statement

Not applicable.

Data Availability Statement

No new data were created.

Conflicts of Interest

The authors declare no conflicts of interest.

Abbreviations

The following abbreviations are used in this manuscript:

| DBT |

Dialectical Behavioral Therapy |

| IFS |

Internal Family Systems |

References

- Astle, D. E.; Holmes, J.; Kievit, R. A. The transdiagnostic revolution in mental health. Nature Reviews Psychology 2022, 1, 255–268. [Google Scholar]

- Beck, A. T. Cognitive Therapy of Personality Disorders, 2nd ed.; Guilford Press: New York, NY, USA, 2011. [Google Scholar]

- Brownell, P. Gestalt Therapy: A Guide to Contemporary Practice; Springer Publishing: New York, NY, USA, 2010. [Google Scholar]

- Castellani, A.; Fonagy, P.; Luyten, P. Defence mechanisms and mentalizing. Psychoanalytic Study of the Child 2021, 74, 1–21. [Google Scholar]

- Castelloe, M. Enantiodromia: The way of the opposites. Psychology Today. 2023. Available online: https://www.psychologytoday.com (accessed on 1 September 2025).

- Freud, S. The aetiology of hysteria. Standard Edition 1896, 3, 189–221. [Google Scholar]

- Freud, A. The Ego and the Mechanisms of Defence; International Universities Press: New York, NY, USA, 1936. [Google Scholar]

- Herrera, C. Gestalt therapy and the dialogue of polarities. Gestalt Review 2017, 21, 155–172. [Google Scholar]

- Jaakkola, E. Designing conceptual articles: Four approaches. AMS Review 2020, 10, 18–26. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Johnson, B. Polarity Management: Identifying and Managing Unsolvable Problems; HRD Press: Amherst, MA, USA, 1992. [Google Scholar]

- Jung, C. G. Psychological Types; Princeton University Press: Princeton, NJ, USA, 1921. [Google Scholar]

- Kernberg, O. Borderline Conditions and Pathological Narcissism; Jason Aronson: New York, NY, USA, 1975. [Google Scholar]

- Klein, M. Notes on some schizoid mechanisms. International Journal of Psycho-Analysis 1946, 27, 99–110. [Google Scholar] [PubMed]

- Linehan, M. M. DBT Skills Training Manual, 2nd ed.; Guilford Press: New York, NY, USA, 2015. [Google Scholar]

- Morin, A. Self-reflection and the inner voice: Developmental origins and therapeutic uses. Journal of Humanistic Psychology 1993, 33, 23–45. [Google Scholar]

- O’Connor, C.; et al. Cognitive flexibility and integration of opposites. Journal of Integrative Psychology 2025, 31, 211–228. [Google Scholar]

- Perls, F. S. The Gestalt Approach & Eye Witness to Therapy; Bantam Books: New York, NY, USA, 1973. [Google Scholar]

- Schwartz, R. C. Internal Family Systems Therapy; Guilford Press: New York, NY, USA, 1995. [Google Scholar]

- Vaillant, G. E. Ego Mechanisms of Defense: A Guide for Clinicians and Researchers; American Psychiatric Press: Washington, DC, USA, 1992. [Google Scholar]

- Winnicott, D. W. The Maturational Processes and the Facilitating Environment; International Universities Press: New York, NY, USA, 1965. [Google Scholar]

- Yu, D. Dichotomous thinking and its relationship to depression and anxiety. Cognitive Therapy and Research 2016, 40, 723–731. [Google Scholar]

- Zinker, J. Creative Process in Gestalt Therapy; Brunner/Mazel: New York, NY, USA, 1977. [Google Scholar]

|

Disclaimer/Publisher’s Note: The statements, opinions and data contained in all publications are solely those of the individual author(s) and contributor(s) and not of MDPI and/or the editor(s). MDPI and/or the editor(s) disclaim responsibility for any injury to people or property resulting from any ideas, methods, instructions or products referred to in the content. |

© 2025 by the authors. Licensee MDPI, Basel, Switzerland. This article is an open access article distributed under the terms and conditions of the Creative Commons Attribution (CC BY) license (http://creativecommons.org/licenses/by/4.0/).