1. Introduction

Ethidium Bromide (EtBr) has long served as a cornerstone reagent in molecular biology, primarily used as a nucleic acid stain in gel electrophoresis due to its high sensitivity and fluorescent properties [

1]. Its ability to intercalate between DNA base pairs makes it an effective tool for visualizing DNA under ultraviolet light [

2,

3]. Despite its widespread utility, EtBr poses significant health and environmental hazards, having been classified as a mutagen and potential carcinogen [

4]. These risks stem from its ability to disrupt DNA replication and transcription, leading to genetic mutations in exposed organisms[

5].

The widespread use of EtBr in academic, clinical, and industrial laboratories generates substantial volumes of chemical waste, raising concerns over improper disposal practices. EtBr is water-soluble and chemically stable, which increases the risk of environmental persistence and contamination of aquatic ecosystems [

6]. Given its mutagenic nature, even trace amounts can pose significant ecological and public health concerns. As awareness of these issues has grown, regulatory bodies and institutional biosafety committees have emphasized the need for effective treatment and disposal methods [

7].

Over the years, several chemical, biological, and physicochemical strategies have been developed to mitigate the risks associated with EtBr waste. These include chemical degradation methods using oxidizing agents such as sodium hypochlorite and potassium permanganate, advanced oxidation processes (AOPs) including photocatalysis and Fenton-like reactions, as well as adsorption using activated carbon and other bio-based materials [

8,

9,

10,

11,

12,

13,

14,

15,

16,

17,

18,

19,

20,

21,

22,

23,

24]. Recently, research has also explored the potential of microbial degradation as an eco-friendly and sustainable alternative [

25,

26,

27,

28,

29,

30]. Each method presents its own advantages, limitations, and challenges with respect to efficiency, scalability, safety, and cost.

This review aims to provide a comprehensive and critical overview of the current methods available for the degradation and detoxification of Ethidium Bromide. Special emphasis is placed on comparing the mechanisms, efficiency, practicality, and environmental safety of these approaches. By synthesizing existing knowledge and identifying gaps in current research, this article seeks to support the development of safer laboratory practices and inform future innovations in EtBr waste management.

2. Historical Background and Applications of Ethidium Bromide

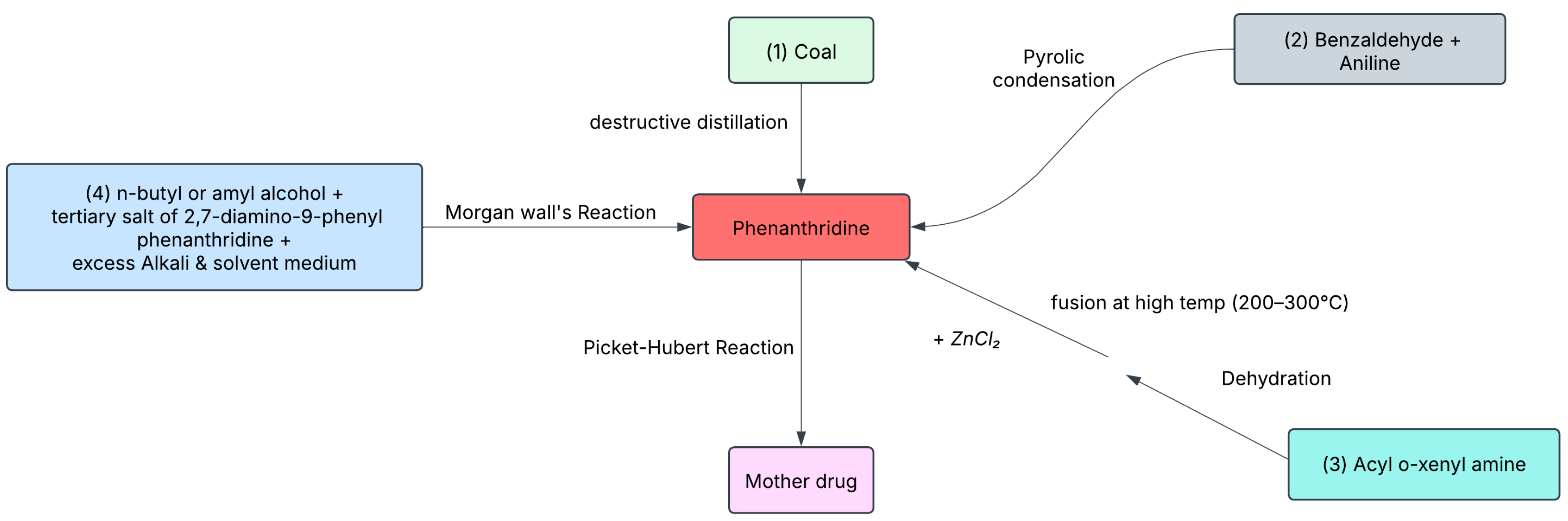

The development of ethidium bromide (EtBr) traces back to the discovery of phenanthridine through the destructive distillation of coal. Because of its structural resemblance to quinoline—an antimalarial agent—phenanthridine attracted interest for potential therapeutic applications. During the 1930s, scientists were actively searching for drugs to combat trypanosomiasis, a parasitic disease severely affecting cattle in sub-Saharan Africa. In 1938, British researchers discovered that certain phenanthridine derivatives, such as dimidium bromide, could provide temporary relief from trypanosomiasis. However, their high toxicity limited therapeutic potential.

In 1952, researchers at Boots Pure Drug Company modified these compounds and developed a safer and more effective alternative: ethidium bromide, commercially introduced as "Homidium." This new compound soon replaced dimidium bromide as a veterinary drug. By the early 1960s, researchers from Cambridge University and the Gustave-Roussy Institute in France identified EtBr's ability to intercalate between DNA base pairs, interfering with replication—a key discovery that expanded its relevance beyond parasitology.

In 1970s when Dutch scientist Piet Borst and his student Cees Aaij, working at the University of Amsterdam, sought an alternative to ultracentrifugation for mitochondrial DNA analysis after their equipment failed. From earlier studies on viral DNA, they stained DNA with EtBr and subjected it to agarose gel electrophoresis. Under UV light, vivid orange bands revealed the presence of DNA, effectively demonstrating EtBr's utility as a nucleic acid stain. Around the same time, across the Atlantic, American biologist Philip Sharp and his team at Cold Spring Harbor Laboratory independently confirmed these findings while working with viral DNA, further validating EtBr's role in molecular biology. These discoveries laid the foundation for the widespread use of EtBr in DNA visualization techniques.

Table 1 summarizes the historical development and major applications of EtBr and the

Figure 1 shows the numerous mechanisms used in the synthesis of phenanthridine.

3. Structural Features and Chemical Properties

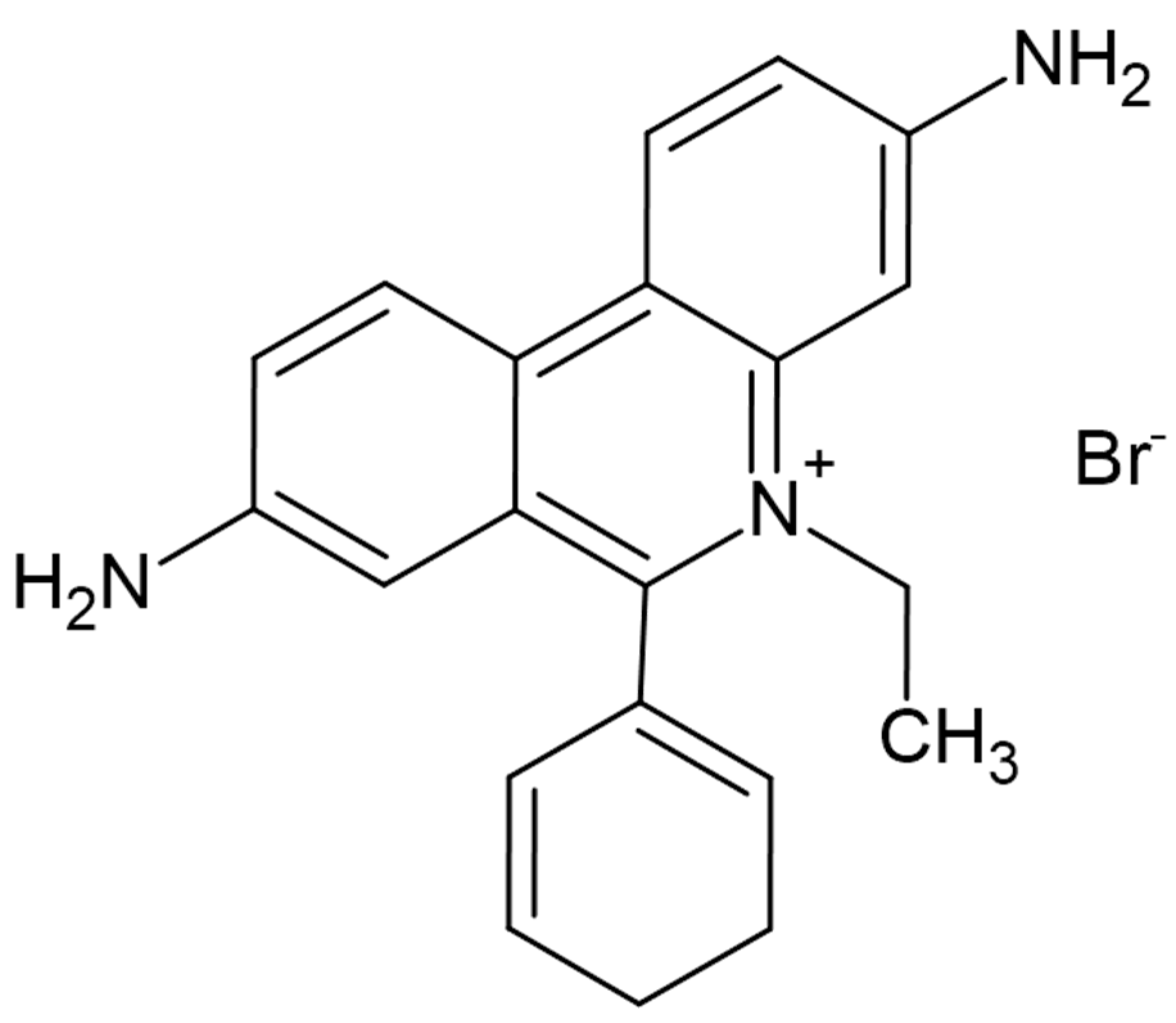

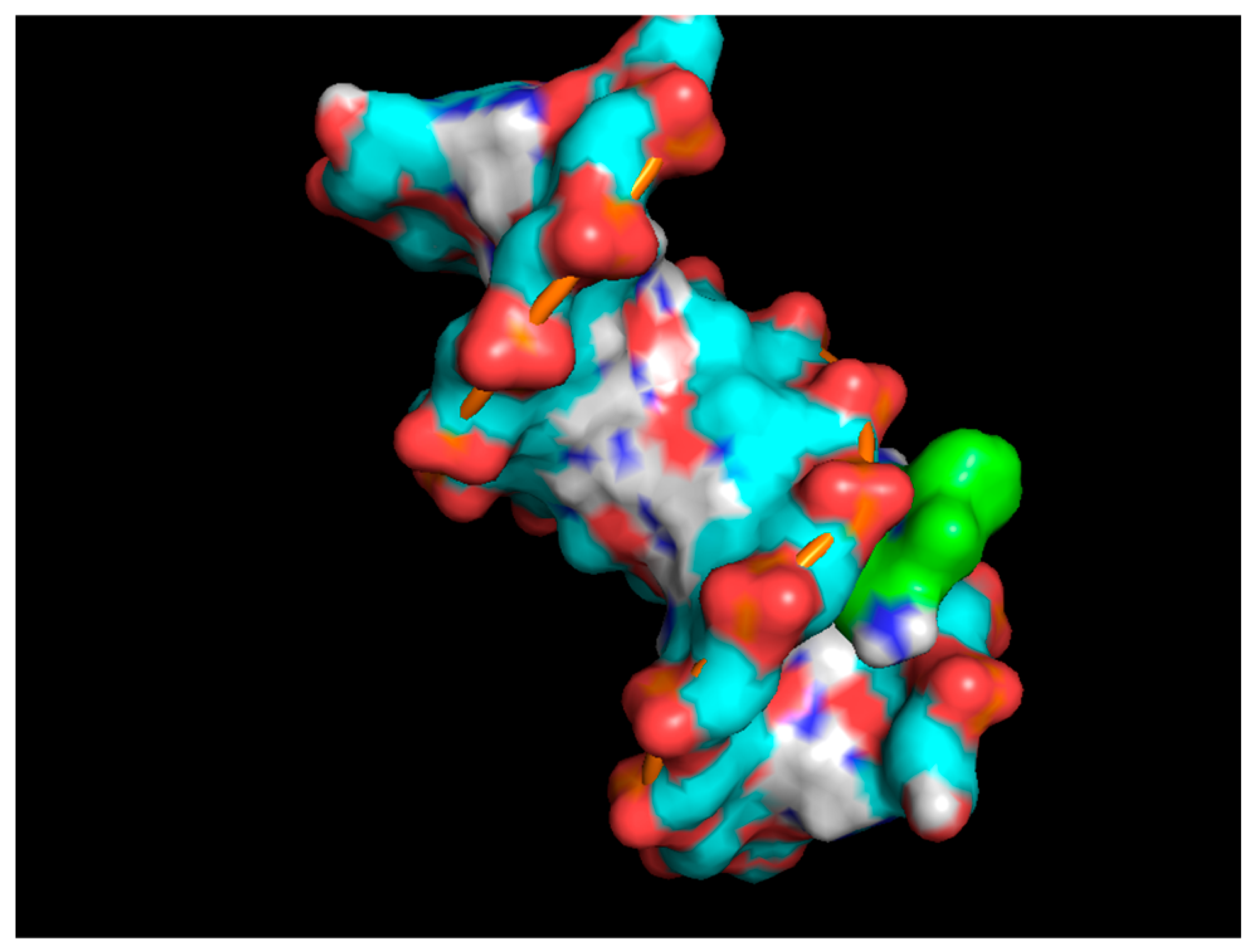

Ethidium bromide (EtBr) is a planar tricyclic compound belonging to the phenanthridine family, characterized by both hydrophilic and hydrophobic properties. The molecular structure consists of three fused rings—two aromatic benzene rings and a nitrogen-containing heterocyclic ring—forming the phenanthridine backbone, shown in

Figure 2. The aromatic rings contribute to the compound’s hydrophobic nature and enable strong π–π interactions with the base pairs of nucleic acids, facilitating intercalation between DNA strands [

32,

33,

34].

The molecule bears a positive charge primarily due to amino groups located at the third and eighth positions of the phenanthridine ring. These amino groups enhance electrostatic interactions with the negatively charged phosphate backbone of DNA or RNA, improving the compound’s binding affinity and fluorescence intensity [

35].

Additional structural features, such as the phenyl group at the sixth position and an ethyl group at the fifth position of the phenanthridine ring, along with a bromine atom attached to the nitrogen in the heterocyclic ring, further enhance the hydrophobicity, steric configuration, and overall stability of the molecule. These structural attributes not only strengthen DNA intercalation but also contribute to EtBr’s effectiveness as a fluorescent dye in molecular biology, particularly in visualizing nucleic acids during gel electrophoresis. The fundamental physicochemical characteristics of Ethidium Bromide, including its molecular formula and related parameters, are summarized in the

Table 2.

4. Mechanism of Action as a DNA Intercalator and Drug Agent

4.1. Mechanism of EtBr as a Drug

Ethidium bromide (EtBr), originally synthesized from dimidium bromide, was commercialized by Boots Pure Drug Co. Ltd. under the trade name Homidium. For nearly three decades, it served as the frontline treatment for trypanosomiasis—a parasitic disease caused by

Trypanosoma species—particularly in livestock. EtBr was especially valued for its efficacy and relatively low toxicity in cattle compared to other available drugs [

37].

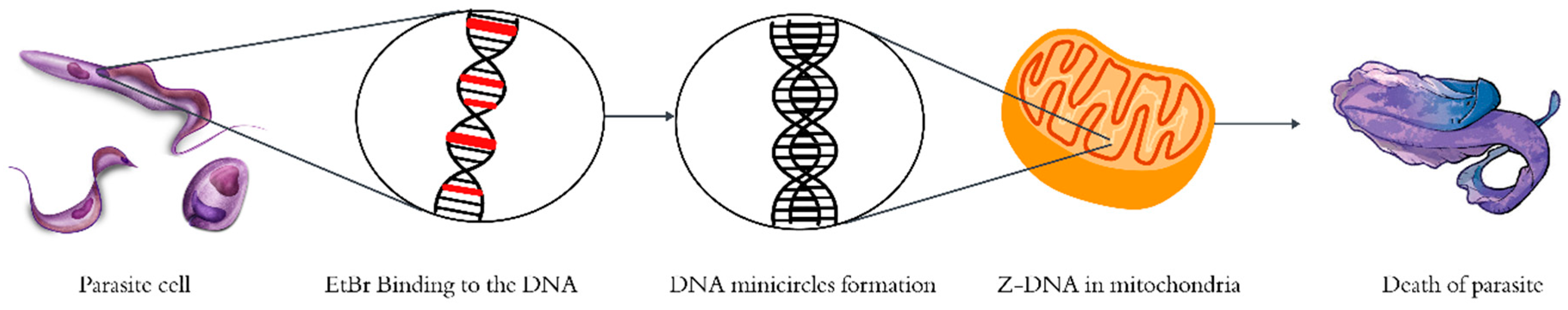

EtBr exerts its anti-trypanosomal activity by targeting the kinetoplast DNA (kDNA) within the parasite's mitochondria, specifically the DNA mini-circles. These mini-circles are normally stabilized by associated proteins that hinder helix unwinding. However, unbound mini-circles, especially those poised for replication, exhibit a high affinity for EtBr.

Upon binding, EtBr intercalates into the DNA, inducing supercoiling and promoting the transition to left-handed Z-DNA. This structural distortion disrupts the normal helical conformation of DNA, thereby inhibiting replication initiation. The loss of functional kDNA leads to mitochondrial dysfunction and ultimately results in parasite cell death. This mode of action made EtBr one of the most extensively studied and effective phenanthridine-based antiprotozoal drugs during the 1950s and 1960s, and the mechanism is illustrated in

Figure 3.

However, prolonged and widespread use of Homidium, especially in regions like Nigeria, led to the emergence of drug-resistant strains of

Trypanosoma congolense [

38]. This resistance trend was later corroborated in Ethiopia [

39]. Consequently, Homidium was progressively replaced by newer anti-trypanosomal agents such as Diaminazene, Metamidium, and Prothidium [

31,

40].

4.2. Mechanism of EtBr as a Dye

Other than a drug, Ethidium bromide (EtBr) is a widely used orange, cationic fluorescent dye, primarily employed for visualizing DNA and RNA in molecular biology. While EtBr often shows sequence-specific binding to nucleic acids, it can also stain proteins to a certain extent. The key feature that makes EtBr especially useful in research is its remarkable fluorescence enhancement upon binding to nucleic acids—its emission intensity can increase up to 20-fold when in the bound state. This enhancement is crucial for molecular techniques like gel electrophoresis, where the visualization of DNA or RNA fragments is required. The underlying mechanism of this fluorescence increase is linked to EtBr’s intercalation into the DNA double helix, a process that alters both the solvent environment surrounding the dye and its electronic configuration.

Several scientific theories have been proposed to explain this fluorescence enhancement. LePecq and Paoletti (1967) suggested that the increase in fluorescence occurs when EtBr intercalates into the hydrophobic region of DNA, where its fluorescence is no longer quenched by water [

41]. In contrast, Burns (1969) theorized that intercalation induces a structural rearrangement in EtBr that allows a previously forbidden electronic transition, thereby increasing fluorescence output [

42]. Another perspective was offered by Hudson and colleagues, who proposed that the dye's triplet state is nearly identical in energy to its lowest excited singlet state, and that the fluorescence enhancement arises due to shifts in energy separation between these two states.[

43] Despite these plausible mechanisms, none of them has been definitively proven, and the precise reason for the fluorescence enhancement remains inconclusive. This uncertainty complicates the use of EtBr as a precise analytical tool for probing DNA structure and its interactions with proteins.

When EtBr binds to DNA, it intercalates mainly through the minor groove, causing significant structural changes in the DNA helix. Specifically, this intercalation reduces the natural helical twist from 36° to about 10°, thereby unwinding the helix by 26°. Ethidium bromide exhibits a preferential binding to GC-rich sequences due to the more favourable structural and energetic interactions these base pairs offer. The intercalation process itself is driven by strong hydrophobic interactions, where the planar aromatic rings of EtBr are pulled into the nonpolar interior of the DNA double helix, away from the surrounding aqueous environment. This is further stabilized by frontier orbital interactions, in which the lowest unoccupied molecular orbital (LUMO) of EtBr interacts with the highest occupied molecular orbital (HOMO) of purine bases like guanine [

44].

Additionally, EtBr tends to dock in specific regions of the DNA helix, particularly toward the lower part or anchor region, which facilitates the stability of the intercalated complex. However, interpreting EtBr’s binding behaviour is complicated by discrepancies in structural studies. For instance, nuclear magnetic resonance (NMR) data support an intercalative binding mode, while certain X-ray diffraction studies suggest a non-intercalative form of binding. This inconsistency, combined with the variability in EtBr’s fluorescence based on its binding extent and sequence context, makes it challenging to use as a reliable probe for precise DNA structural analysis [

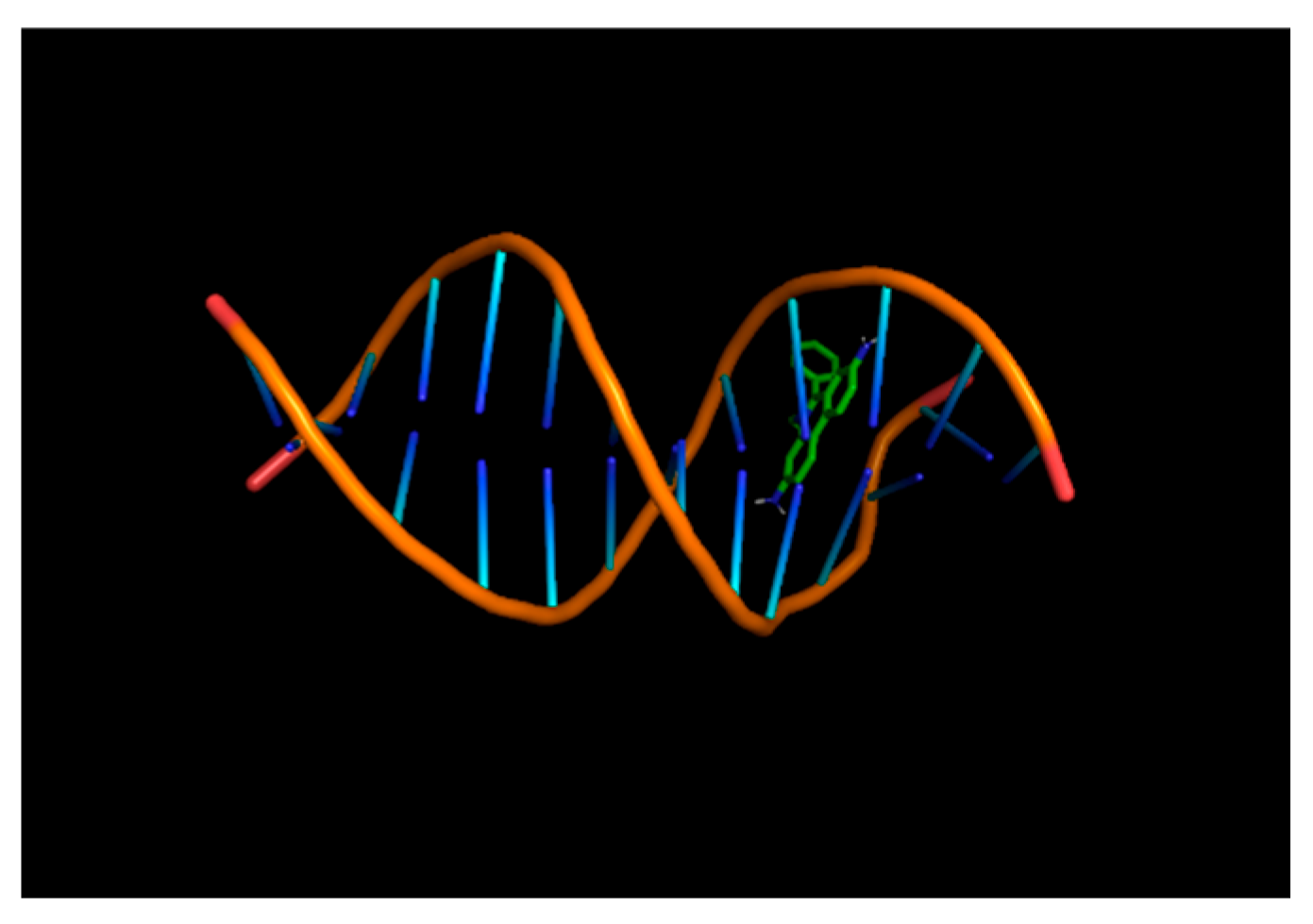

45]. The accompanying illustrations in

Figure 4 and

Figure 5 visually depict Ethidium Bromide intercalating between DNA base pairs in wireframe and surface models, highlighting the molecular interactions and is done with the help of Molecular docking tool Autodock vena.

5. Toxicological Profile: Mutagenic and Carcinogenic Potential

Despite its widespread application in molecular biology, ethidium bromide (EtBr) is a known mutagen and potential carcinogen, which necessitates strict handling protocols and disposal practices in laboratory environments. Its improper management poses significant environmental and health hazards, especially when it escapes from controlled settings into the broader ecosystem. Although EtBr remains a staple in many labs due to its affordability and strong fluorescence properties, its disposal continues to raise serious concerns. EtBr waste, if untreated or discarded by landfill mode can leach into soil and water systems, threatening groundwater quality, agricultural productivity, and public health.

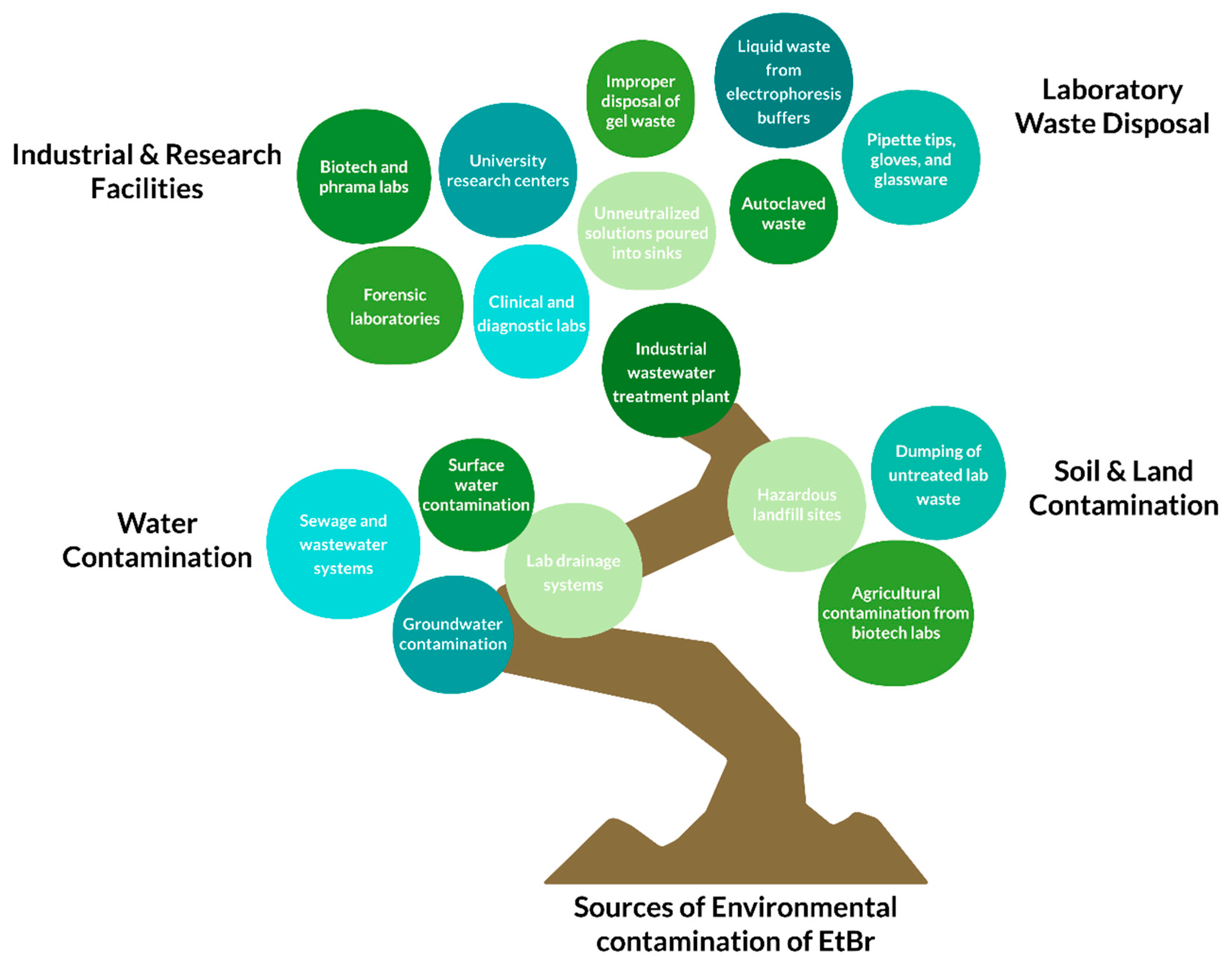

Major contributors to EtBr contamination include manufacturing units, research and development facilities, industries employing EtBr, veterinary dispensaries, urban and industrial wastewater treatment plants, and landfill sites. These sources serve as environmental entry points, allowing EtBr to persist and spread. The compound is known to be both genotoxic and mutagenic and

Figure 6 briefly discusses the major sources of the environmental contamination of EtBr, including laboratory waste disposals, soil and land contamination, water contamination, industrial and research facilities.

Experimental studies have shown that EtBr can induce recessive lethal mutations in

Drosophila melanogaster and exert strong mutagenic effects on bacterial populations. Its classification as a potent mutagen and carcinogen underlines the serious risks it poses to both the environment and human health [

46,

47].

Historical research provides clear evidence of EtBr’s disruptive biological effects. In 1957, it was observed to inhibit nucleic acid synthesis and cell growth in the flagellate

Strigomonas oncopelti, reducing the DNA content of cells by nearly 50% during replication [

48]. Follow-up experiments in 1964 demonstrated that

Escherichia coli was unable to grow in the presence of EtBr [

49]. Additional studies revealed that EtBr could induce chromosomal abnormalities in sea urchin eggs, thereby interfering with proper cell division [

50,

51]. In mammalian cells, such as mouse fibroblasts and hamster kidney cells, EtBr disrupted mitochondrial DNA, a finding that was later linked to impaired respiration in human cells due to reduced cytochrome oxidase activity [

52]. In high doses, EtBr not only depleted mitochondrial DNA but also led to irreversible cell death [

53].

Further studies expanded on EtBr’s mutagenic profile. It was shown to induce frameshift mutations in bacteria, particularly after metabolic activation by liver microsomes [

54]. In fruit flies (

Drosophila melanogaster), EtBr exposure resulted in toxic effects such as reduced productivity, altered morphology, and disturbed biochemical markers—likely due to its strong genotoxic nature [

55]. Although much of the current toxicological data stems from research involving cultured cells, microorganisms, and a few model organisms, the broader ecological implications—especially concerning aquatic life, plants, and humans—remain underexplored. Given its potent mutagenic, genotoxic, and cytotoxic effects, it is imperative that EtBr undergo thorough degradation before disposal to avoid environmental contamination and associated health hazards [

26,

51,

56].

6. Strategies for Safe Handling and Removal of EtBr

The growing concern over the environmental and health hazards posed by Ethidium Bromide (EtBr) contamination has intensified the need for its effective and safe disposal from laboratory and industrial waste streams. EtBr, a potent mutagen and suspected carcinogen, when released untreated into the environment, can persist in water and soil systems, posing serious risks to human health, wildlife, and ecological balance [

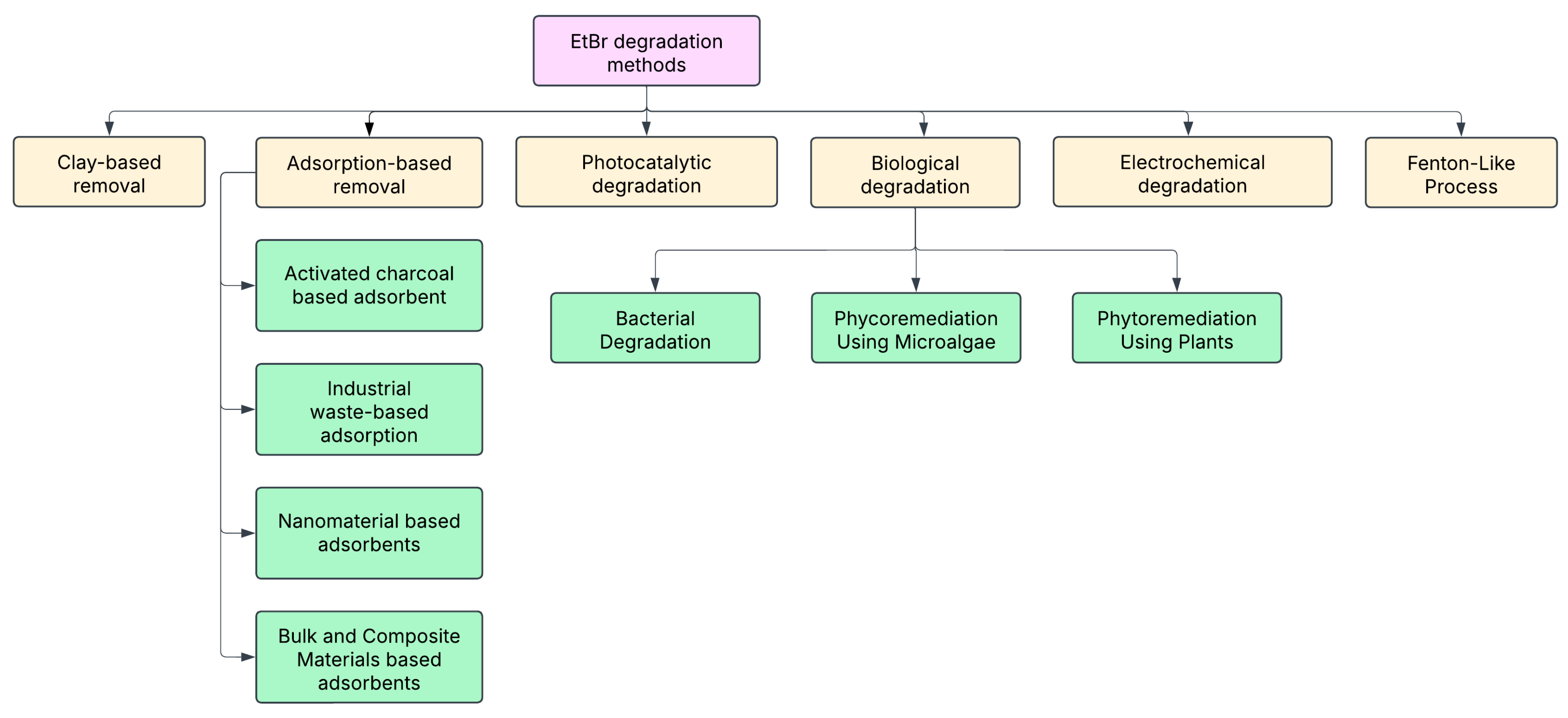

6]. Therefore, the primary objective is to achieve the complete degradation or removal of EtBr from various waste sources using advanced, reliable, and sustainable treatment strategies.

To address this challenge, a wide range of decontamination technologies have been developed and optimized, including physical, chemical, and biological approaches. Among the most prominent are adsorption-based techniques (utilizing activated carbon and advanced porous materials), clay-based adsorption systems, electrochemical degradation methods, biological degradation using microbial consortia, photocatalytic degradation driven by semiconductors under light exposure, Fenton and Fenton-like catalytic oxidation processes, and nanoparticle-assisted remediation strategies [

6,

8,

9,

10,

11,

12,

13,

14,

15,

16,

17,

18,

19,

20,

21,

22,

23,

24,

25,

26,

27,

28,

29,

30,

35,

57,

58,

59]. Each of these methods offers unique advantages in terms of efficiency, scalability, environmental compatibility, and cost-effectiveness.

The following section explores these EtBr remediation techniques in detail, highlighting their underlying mechanisms, efficacy, and potential for integration into sustainable laboratory waste management protocols. An illustrative

Figure 7 is also provided to visually summarize the diverse EtBr removal strategies and their classification based on the underlying mechanism.

6.1. Adsorption-Based Techniques

Several treatment methods are available for the removal of contaminants from water, including membrane separation, precipitation, flocculation, coagulation, adsorption, and ion-based separation processes [

60]. Among these, adsorption is considered one of the most effective techniques due to its non-toxic nature, economic feasibility, operational simplicity, reusability, and its high selectivity [

8]. However, at the industrial scale, adsorption faces certain limitations, primarily due to the low adsorption capacity of some adsorbents.

Adsorption is a reversible surface phenomenon, generally classified into two types: physisorption and chemisorption. Physisorption relies on weak physical forces, while chemisorption involves the formation of chemical bonds, making it relatively stronger and more stable [

61].

In recent years, a wide range of adsorbents have been explored for the removal of Ethidium Bromide (EtBr), driven by the increasing demand for cost-effective and sustainable alternatives. The performance of an adsorbent is influenced by several critical parameters, including its adsorption capacity, available surface area, pore size and volume, regenerability, and environmental compatibility [

11]. Among these, the maximum adsorption capacity is a key determinant of effectiveness and is typically evaluated using adsorption isotherm models.

Various isotherm models—such as the Langmuir, Freundlich, Temkin, Brunauer–Emmett–Teller (BET), and Dubinin–Radushkevich (D–R) isotherms—are used to describe the adsorption behaviour of solutes. These models are derived by plotting the concentration of adsorbate on the solid phase against the concentration of the solute in the liquid phase at a constant temperature [

61].

Numerous adsorbents have been investigated for EtBr removal, including palladium nanoparticles, activated charcoal, nutraceutical industrial fennel seed spent, natural pumice, aluminum-coated pumice, pyrophyllite nanoclay, single-walled carbon nanotubes (SWCNTs), carboxylate-functionalized SWCNTs, palygorskite, and sodium alginate/graphene oxide composite beads [

11,

12,

13,

14,

18,

23,

57]. Each of these materials exhibits unique surface properties and adsorption characteristics, which significantly influence their suitability and efficiency in EtBr removal from aqueous environments.

6.1.1. Activated Charcoal-Based Adsorbent

Activated charcoal is a widely studied adsorbent due to its cost-effectiveness, eco-friendliness, and broad compatibility with various adsorbates [

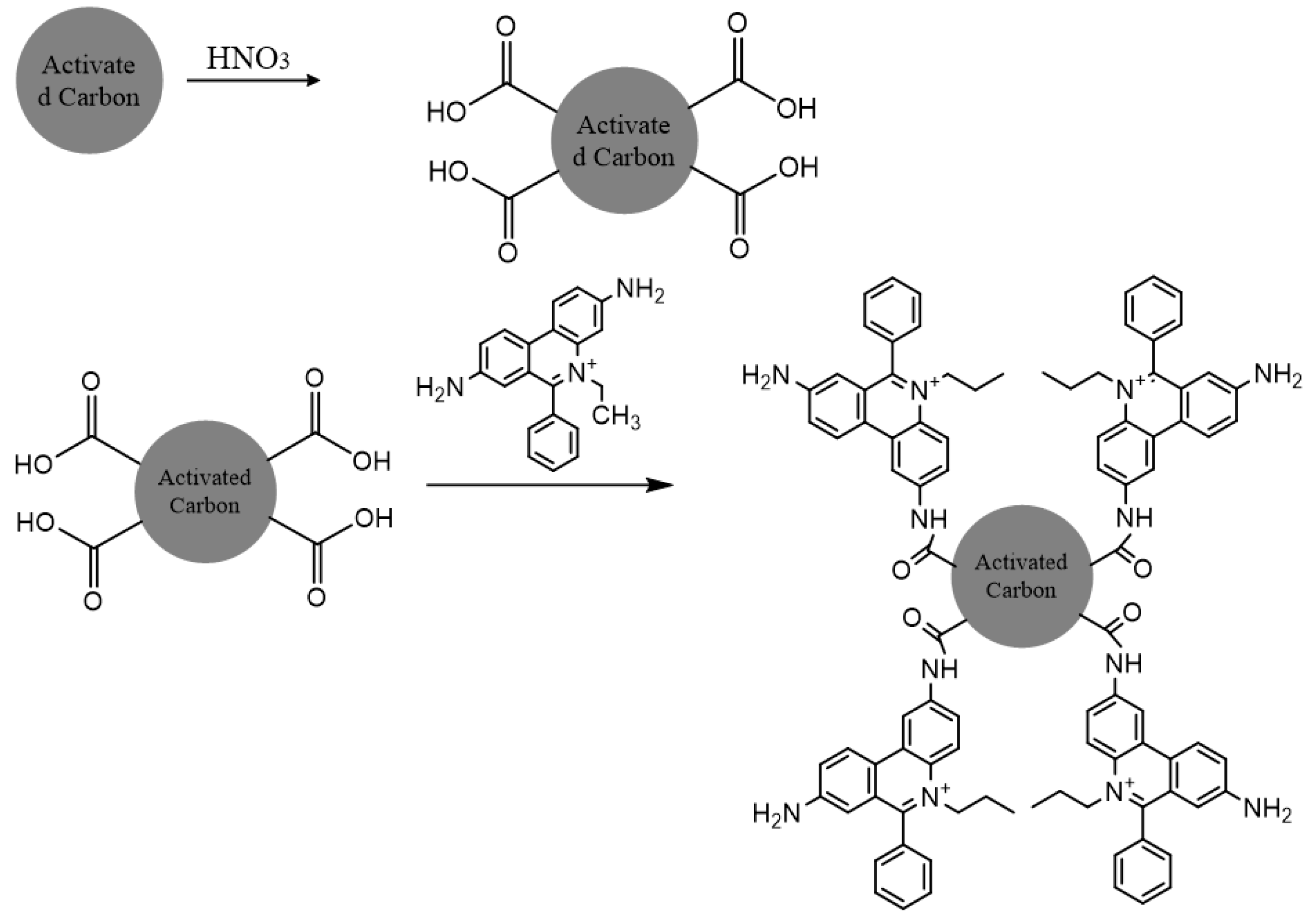

62]. Its application in the removal of Ethidium Bromide (EtBr) has recently gained attention. The adsorption efficiency of activated charcoal is significantly influenced by factors such as pore size and the functional groups present on its surface and within its porous structure. Studies have shown that EtBr removal efficiency increases with higher concentrations of activated charcoal. For instance, in a 1:2 dye-to-charcoal ratio, the removal efficiency for 0.5 mg/mL of EtBr reached 94.4%. Optimal adsorption conditions were found to include a neutral to slightly basic pH range (7–8), dissolved oxygen levels of 5.0–9.0 mg/L, biochemical oxygen demand (BOD) between 25.06–78.2 mg/L, and chemical oxygen demand (COD) in the range of 302.56–310.98 mg/L. Under these conditions, the primary binding mechanisms contributing to EtBr adsorption are π-π interactions, electrostatic interactions, hydrogen bonding, and physical pore-filling.

The proposed reaction mechanism for EtBr adsorption onto activated carbon involves a three-step functionalization process. Initially, activated carbon is oxidized using nitric acid (HNO₃), introducing carboxyl (-COOH) and amine (-NH

2) functional groups onto the surface. In the second step, the oxidized carbon reacts with an amine-containing linker molecule to form stable amide (-CONH-) or imide bonds. Finally, EtBr molecules are covalently attached to the functionalized carbon through multiple bonding sites, enhancing the stability and adsorption efficiency of the system [

11]. The overall mechanism for binding of EtBr on the surface of the activated charcoal is discussed in

Figure 8.

6.1.2. Industrial Waste-Based Adsorption

In recent years, researchers have increasingly focused on transforming industrial and other forms of waste into value-added products. One such promising material investigated for this purpose is nutraceutical industrial fennel seed spent (NIFSS), which has been explored as an effective adsorbent for the removal of Ethidium Bromide (EtBr) from aqueous solutions. NIFSS, collected from a local industry, was dried and characterized using scanning electron microscopy (SEM), which revealed a fibrous and porous structure conducive to adsorption. Fourier-transform infrared (FTIR) spectroscopy confirmed the adsorption of EtBr onto the NIFSS surface. Shifts in characteristic peaks, including -NH stretching at 3178 cm⁻¹ and C-N stretching in both aliphatic (1318–1259 cm⁻¹) and aromatic (1621–1499 cm⁻¹) regions, indicated strong molecular interactions. Further spectral changes in C=C and C-C stretching vibrations provided additional evidence supporting its adsorption capability.

Experimental investigations under varying conditions demonstrated that fennel seed spent, despite having undergone multiple chemical, thermal, and mechanical processes during its initial use, retains significant potential as a low-cost and sustainable adsorbent rather than being discarded as waste [

57]. The optimal parameters identified for effective EtBr removal using NIFSS are summarized in

Table 3.

6.1.3. Nano-Composites

Nanosized materials, characterized by at least one dimension in the 1–100 nm range, exhibit unique physicochemical properties that make them highly effective for environmental remediation, particularly in adsorption applications. Various nanoparticles, including CuO, Fe₃O₄, Pd, Mn²⁺-doped ZnS, and single-walled carbon nanotubes (SWCNTs), have been extensively explored for their enhanced surface reactivity and adsorption efficiency [

8,

13,

63].

Nanoparticles possess a high surface-to-volume ratio, which significantly improves their adsorption capacity. Functionalization, such as carboxyl-modified SWCNTs (SWCNT-COOH), enhances electrostatic interactions, facilitating pollutant removal [

13]. Fe₃O₄ nanoparticles, due to their small size, enable faster adsorption kinetics, while Pd nanoparticles demonstrate a specific affinity toward pollutants[

8]. These nano-composites have been successfully employed for removing contaminants such as heavy metals, dyes, trihalomethanes (THMs), and ethidium bromide (EtBr) from aqueous systems.

Despite their promising efficiency and versatility, the large-scale use of nano-composites faces several challenges. High production costs, the need for regeneration, and difficulties in downstream processing limit their widespread adoption. Nanoparticles, particularly non-magnetic variants, tend to aggregate, reducing their adsorption efficiency and making their separation from treated solutions challenging[

59,

64]. However, materials like magnetic Fe₃O₄ nanoparticles offer easier recovery through external magnetic fields [

59]. The recyclability of nano-composites remains a crucial concern, with limited studies evaluating their long-term usability. Additionally, their environmental impact, particularly in terms of toxicity and persistence in water systems, necessitates further investigation. Adsorption mechanisms, especially in non-swelling aluminosilicates, are not fully understood, limiting their optimization and scalability [

58].

To address these challenges, researchers are exploring cost-effective and naturally occurring alternatives such as pumice stone and aluminum-coated pumice. While nano-composites offer substantial potential for pollutant remediation, improving cost-efficiency, recyclability, and environmental compatibility is essential for their practical implementation [

23].

6.1.4. Bulk Composites

Bulk composites, including clay minerals and other natural or modified adsorbents, have been widely used for contaminant removal due to their affordability, availability, and adsorption efficiency. These materials offer practical advantages over nano-composites, especially in large-scale applications where cost and ease of handling are critical factors [

14,

16,

18,

19].

Clay minerals, such as Ca-montmorillonite, rectorite, and palygorskite, are highly valued for their abundance and minimal pretreatment requirements. These materials exhibit adsorption capacities as high as 500 mg/g, making them effective in removing various contaminants, including EtBr. Some clay minerals, such as palygorskite, have demonstrated exceptional adsorption efficiencies, exceeding their cation exchange capacities (CEC), with adsorption values reaching 275 mmol/kg (108 mg/g). Additionally, their negative surface charge facilitates interactions with positively charged pollutants, enhancing their removal efficiency [

14].

Despite these benefits, bulk composites present several limitations. One significant challenge is the difficulty in separating these materials from aqueous solutions after pollutant adsorption. Swelling and non-swelling clay minerals may undergo electrostatic interactions that reduce adsorption efficiency or complicate desorption. The pore structure and size distribution of bulk composites can also impact their performance, requiring careful selection based on the specific contaminant.

Overall, bulk composites provide a cost-effective, widely available, and efficient option for environmental remediation. However, factors such as separation difficulties, electrostatic interactions, and contaminant-specific performance variations must be considered for optimal implementation in adsorption-based removal strategies [

14,

18,

19,

35]. The various methods described are summarized in

Table 3

6.2. Clay-Based Removal

Since 2020, various clay-based adsorbents have been extensively studied and reported for their efficient removal of Ethidium Bromide (EtBr). These materials offer significant advantages, including high surface area, cost-effectiveness due to their natural abundance, and unique layered structures with surface charge characteristics. While multiple adsorption mechanisms occur on the surface, the predominant mechanism in clay-based adsorbents has been identified as cation exchange-based adsorption.

Several clay-based materials, such as Montmorillonite, Ca-Montmorillonite, and Rectorite, have demonstrated excellent adsorptive capabilities, following a similar adsorption mechanism [

16,

19,

35]. The high cation exchange capacity and large surface area of these clays facilitate efficient adsorption of EtBr. In aqueous solutions, EtBr exists as a cationic species (Et⁺), balanced by bromide ions (Br⁻). Due to the negatively charged nature of clays and their high cation exchange capacity, they effectively attract and adsorb EtBr molecules. This process involves the replacement of interlayer cations with Et⁺, stabilizing EtBr within the clay structure through strong electrostatic interactions.

Reported adsorption capacities include 502.89 mg/g for Ca-Montmorillonite, 600 mg/g for Montmorillonite, and 157.72 mg/g for Rectorite. Despite their advantages, clay-based adsorbents face certain limitations, such as structural and functional degradation over repeated adsorption-desorption cycles. Additionally, studies have not clearly distinguished between adsorption occurring at the external surface and within the interlayers of these materials.

6.3. Biological Degradation

Biological methods for EtBr degradation offer eco-friendly and sustainable alternatives to conventional removal techniques. Several mechanisms have been explored, including bacterial degradation, phycoremediation, and phytoremediation.

6.3.1. Bacterial Degradation

Studies have focused on isolating EtBr-degrading bacteria from soil, but interestingly, soil bacteria showed no degradation potential based on study from Sukhumungoon et al. Instead, bacteria found in tap water and sewage demonstrated the ability to degrade EtBr, highlighting their potential for laboratory waste treatment. In one study, the B4 bacterial strain accumulated EtBr within its biomass, indicating uptake potential but limited degradation ability, whereas the B3 strain exhibited actual degradation capabilities. However, neither strain could utilize EtBr as a sole carbon source [

25].

Anil Kumar et al. isolated two bacterial species, BR3 and BR4. BR3, similar to

Proteus terrae N5/687, is non-pathogenic and part of human microflora, while BR4, similar to

Morganella morganii subsp. morganii ATCC 25830, is an opportunistic pathogen classified in risk group II. BR3 was identified as a potential candidate for large-scale EtBr degradation. However, bacterial degradation presents significant limitations: it is time-consuming, requiring 2–5 days for a 30 µg/mL solution and 5–8 days for a 60 µg/mL solution, compared to adsorption, which occurs within hours. Additionally, prolonged bacterial exposure to EtBr may lead to antibiotic resistance, posing another concern [

26].

6.3.2. Phycoremediation Using Microalgae

Microalgae-based remediation presents advantages over bacterial methods, as algae require simpler substrates and are easier to cultivate [

65]. In one study, three algal species were tested for EtBr removal.

Chlorella vulgaris showed potential for short-term treatment, while

Desmodesmus subspicatus demonstrated long-term efficiency, removing EtBr after one hour and sustaining biomass production after three hours. However, high EtBr concentrations reduced algal yield and inhibited growth [

28]. The scalability of phycoremediation remains uncertain, as most studies have been conducted on a laboratory scale. Optimization of parameters such as initial algae concentration, species selection, and treatment time could enhance removal efficiency. Additionally, a deeper understanding of algal metabolic pathways could aid future research.

6.3.3. Phytoremediation Using Plants

Plants have also been investigated for EtBr removal. However, studies indicate that EtBr inhibits plant growth within a few days and causes plant death after ten days. Future research could explore strategies such as encouraging contaminant accumulation in plant shoots rather than roots to enhance reusability. While EtBr toxicity in plants is lower than in animals, a major concern is bioaccumulation. If food-producing crops are used for remediation, EtBr could enter the food chain, raising safety concerns [

27].

6.4. Photocatalytic Degradation

Photocatalytic degradation of ethidium bromide (EtBr) is an advanced oxidation process that utilizes light and a catalyst, typically metal oxides, to break down the dye molecule [

66]. In recent years, research on photocatalytic dye degradation has significantly increased, with EtBr gaining attention due to its hazardous nature. The advantage of this method is that EtBr, being a derivative of phenanthridium, can be easily degraded by sunlight-induced reactive oxygen species, particularly in the presence of metal oxides, especially Titanium oxide [

64,

66,

67,

68,

69,

70].

6.4.1. Mechanism of Photocatalytic Degradation

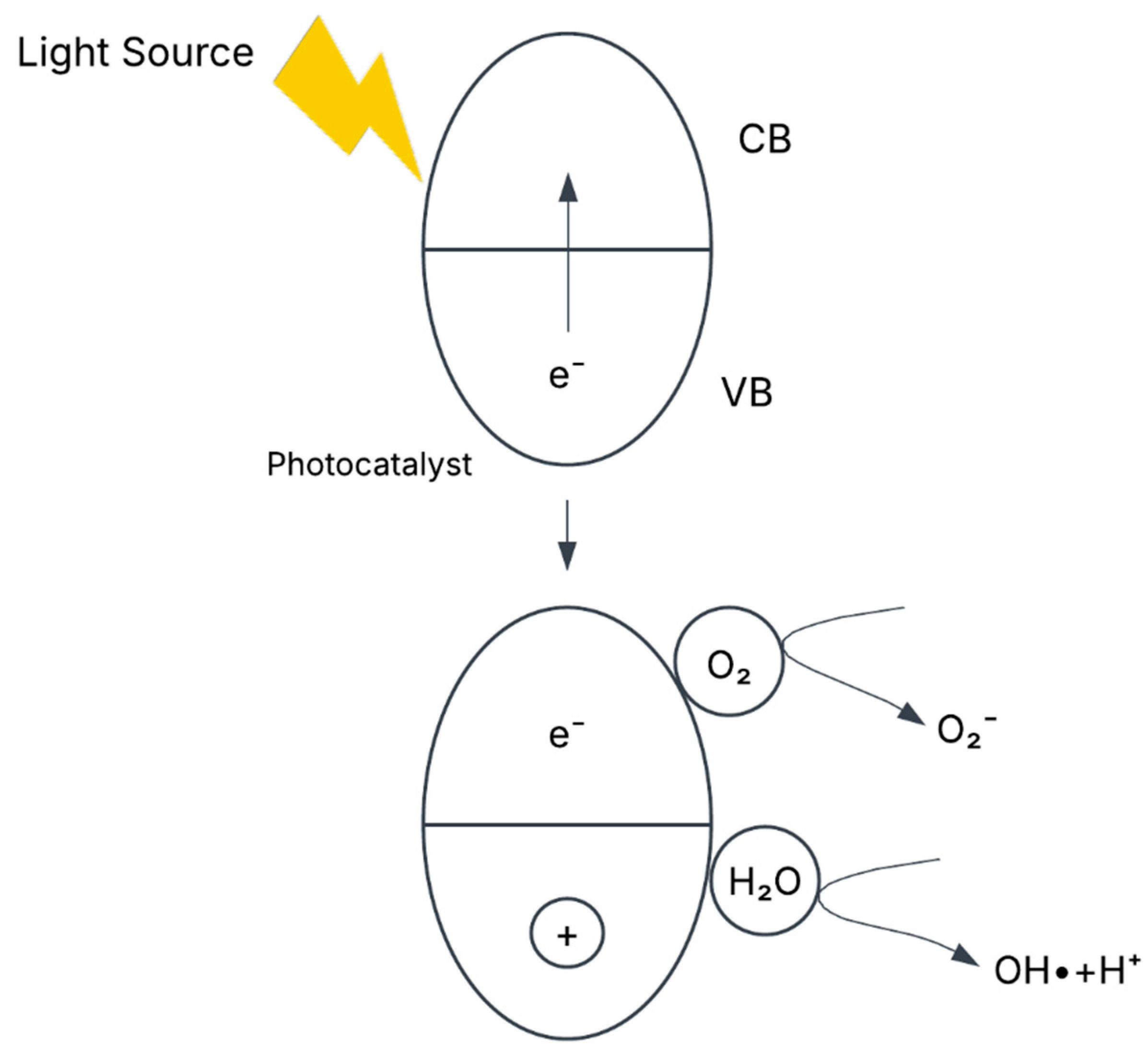

In photocatalytic degradation, the photocatalyst acts as a semiconductor that absorbs photons upon light irradiation. This energy excites electrons from the valence band (VB) to the conduction band (CB), creating electron-hole pairs. The holes in the valence band exhibit high oxidative potential, directly oxidizing EtBr into reactive intermediates (Et⁺). Additionally, hydroxyl radicals (•OH), generated either by water decomposition under irradiation or through interactions with holes, play a crucial role in further oxidizing and mineralizing EtBr. The generalized mechanism of photocatalytic degradation is depicted in the

Figure 9.

Key Reactions includes the

- 2.

Oxidation of EtBr and Hydroxyl Radical Formation

- 3.

Reduction of Oxygen and Formation of Reactive Oxygen Species (ROS)

The overall photocatalytic mechanism begins with the establishment of adsorption-desorption equilibrium between EtBr and the photocatalyst through continuous stirring in the dark. Upon light exposure, photoexcitation occurs, leading to electron-hole generation. These charge carriers interact to form reactive species such as hydroxyl radicals (•OH) and superoxide anions (•O2⁻), which facilitate the oxidative and reductive breakdown of EtBr. Ultimately, this process results in the complete degradation and mineralization of EtBr into non-toxic by-products, demonstrating the effectiveness of photocatalysis for EtBr removal.

Titanium oxide nanoparticles are widely used as photocatalysts for EtBr degradation, with various synthesis methods available for their production. These include the sol-gel method, co-precipitation, hydrothermal and solvothermal synthesis, microemulsion method, green synthesis, and electrochemical synthesis. Among these, the sol-gel and reverse microemulsion methods are the most preferred due to their efficiency in producing highly active photocatalysts. Additionally, metal doping is commonly employed to enhance photocatalytic efficiency by modifying the band gap and extending light absorption [

68,

69]. Co-doping with multiple elements further improves performance by combining band gap narrowing and charge trapping effects, leading to superior degradation capabilities [

64]. However, a notable limitation of using titanium oxide nanoparticles is the need for ultrafiltration or sedimentation to separate the catalyst from water bodies after degradation. To address this issue, a study by Youssef et al. proposed an innovative solution by developing a nanocomposite in which TiO

2 is immobilized as a thin film, providing an effective approach to overcome separation challenges while maintaining photocatalytic efficiency. The following

Table 4 provides a summary of various studies on photocatalytic degradation of EtBr.

6.5. Electrochemical Degradation

Another method employed for the removal of EtBr from water is electrochemical degradation, which is considered an effective approach for treating contaminated water. One of its main advantages is its eco-friendly nature, as it operates under mild conditions, involves limited operational costs, and ensures efficient contaminant removal [

20].

The electrochemical degradation process depends on several key parameters, including anode material, solution pH, reaction time, temperature, electrolyte type, and concentration, all of which influence the oxidation process. Among these, current density and organic load are the most critical factors regulating the yield of oxidants. The electrochemical oxidation mechanism begins with electron transfer at the anode, where pollutants—such as EtBr—adsorb onto the anode surface and undergo direct oxidation. The anode acts as an electron acceptor, breaking down organic compounds. In the case of non-active anodes, water molecules are oxidized, forming highly reactive hydroxyl radicals (•OH), which facilitate pollutant degradation [

71]. This process is represented by the following reaction:

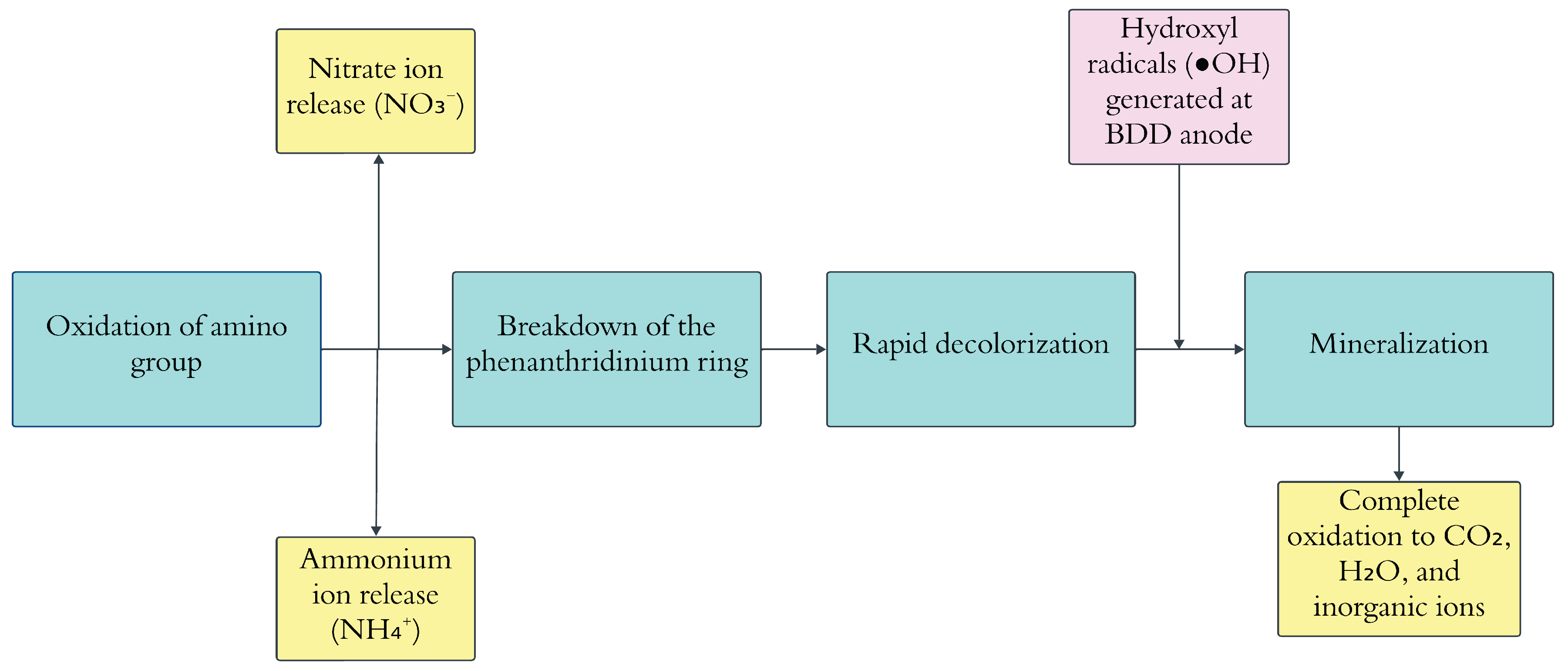

Despite its efficiency, electrochemical degradation has certain limitations, including rapid electrode activity loss, limited-service life, and partial oxidation. However, a study by C. Zhang et al. suggested that boron-doped diamond (BDD) electrodes could effectively overcome these challenges. Their findings demonstrated that anodic oxidation using a BDD electrode is a highly efficient method for treating EtBr-contaminated effluents, ensuring complete degradation while maintaining low energy consumption [

20].

The following flowchart depicted in the

Figure 10 illustrates the possible reaction mechanism proposed by C. Zhang et al.

6.6. Fenton-like Process Degradation

The Fenton-like process is an advanced oxidation process (AOP) that facilitates the generation of hydroxyl radicals (•OH) through the catalytic decomposition of hydrogen peroxide (H

2O

2) using iron-based or other transition metal catalysts [

72]. This mechanism serves as a variation of the conventional Fenton reaction, which relies on Fe²⁺ (ferrous ions) and H

2O

2 under acidic conditions to produce highly reactive hydroxyl radicals for the degradation of organic pollutants [

73].

Recent studies have explored the potential of fly ash and its magnetic fraction as heterogeneous Fenton catalysts for ethidium bromide (EtBr) degradation in aqueous solutions. Experimental findings indicated that surface adsorption by fly ash and its magnetic fraction did not significantly contribute to EtBr removal. Additionally, H

2O

2 alone exhibited minimal degradation efficiency. However, when H

2O

2 was combined with fly ash and its magnetic fraction, an enhanced degradation rate was observed. This improvement was attributed to the high iron oxide content in the magnetic fraction, which facilitated a more effective Fenton-like catalytic process [

59].

Reaction Mechanism of the Heterogeneous Fenton-Like Process

- 2.

Hydroxyl Radical Generation

- 3.

Target Pollutant Oxidation

The study further demonstrated that the fly ash magnetic fraction exhibited superior catalytic efficiency due to its higher iron content, which promoted greater hydroxyl radical formation. This highlights its potential as a highly promising heterogeneous Fenton catalyst for EtBr degradation.

Heterogeneous Fenton catalysts derived from iron-bearing minerals have gained significant attention due to their advantages, including high natural abundance, mild operating conditions, the absence of hazardous reagents, and low cost. The fly ash magnetic fraction exhibited a catalytic degradation efficiency of approximately 98% under optimal conditions. Additionally, the preparation of this material requires only a simple clean-up and separation process, making it a viable option for large-scale applications. Reusability assessments further indicated that both fly ash and its magnetic fraction retained more than 95% of their catalytic activity even after three reaction cycles (totalling 8 hours of reaction time). This high stability suggests that these materials can be efficiently employed in continuous treatment systems for the removal of EtBr and potentially other organic contaminants from aqueous environments [

59].

7. Future Directions

Despite the considerable advancements in developing a range of photocatalytic and adsorptive materials for the effective removal of Ethidium Bromide (EtBr) from aqueous environments, several critical research gaps continue to hinder their practical and scalable deployment. Addressing these limitations is essential for transitioning from laboratory-scale studies to real-world environmental and industrial applications. The following avenues outline key directions for future research:

7.1. Mechanistic Elucidation at the Molecular Level

Although a variety of materials—including doped titanium dioxide (TiO2), palladium nanoparticles (PdNPs), activated carbon, bio-waste-derived adsorbents, nanoclays, and polymeric composite beads—have demonstrated notable EtBr removal efficiencies, the underlying mechanisms remain inadequately explored in many cases. Insights into adsorption kinetics, intercalation behaviour, electron transfer dynamics, and surface interaction chemistry are often limited. Integrating advanced spectroscopic techniques (e.g., FTIR, XPS, EPR) with computational simulations and molecular modeling could provide a deeper understanding of these interactions, ultimately enabling the rational design of more selective and efficient systems.

7.2. Long-Term Performance and Regeneration

Many current studies assess material performance over a limited number of cycles under static conditions. However, for real-world applications, it is necessary to evaluate the long-term stability, reusability, and regeneration potential of these materials, especially under continuous-flow systems or fixed-bed reactors. Understanding catalyst degradation pathways and the stability of adsorbed or degraded by-products is essential to ensure sustainable application and prevent secondary pollution.

7.3. Performance in Complex and Real Wastewater Matrices

Experimental evaluations are frequently conducted under ideal laboratory conditions, which do not accurately represent the complex nature of actual pharmaceutical or laboratory wastewater. These real matrices often contain diverse co-contaminants, fluctuating pH, high ionic strengths, and organic loads that can significantly influence removal efficacy. Future studies should include real-world simulations or field trials to validate the robustness, selectivity, and operational feasibility of the proposed materials under practical environmental conditions.

7.4. Scalability and Economic Viability

Materials such as graphene oxide and metal-organic frameworks (MOFs) have shown promise but are often limited by high production costs and complex synthesis protocols. Future research should emphasize the development of economically viable, low-cost alternatives using abundant and renewable precursors. In addition, life-cycle assessments and techno-economic analyses are necessary to evaluate the feasibility of upscaling these technologies for industrial-scale wastewater treatment.

7.5. Fate of Degradation Products and Environmental Safety

Whether removal is achieved via adsorption or photocatalytic degradation, the transformation products and residual-loaded materials must be critically assessed for their potential ecotoxicity and environmental impact. Comprehensive toxicity assays, coupled with proper disposal or regeneration strategies, are required to ensure that treatment processes do not introduce new contaminants into the environment.

7.6. Design of Multifunctional and Hybrid Systems

Given the limitations of standalone adsorptive or photocatalytic systems, the future holds great promise for the development of multifunctional materials. Hybrid systems that couple adsorption and photocatalysis—or that integrate antimicrobial, sensing, and catalytic functionalities—can enhance treatment efficiency and broaden the spectrum of target pollutants. Such integrative approaches may offer more adaptable and robust solutions for complex wastewater treatment scenarios.

8. Conclusion

Ethidium bromide has played a pivotal role in molecular biology, particularly in the visualization of nucleic acids. However, with growing awareness of its mutagenic and potentially carcinogenic nature, concerns regarding its environmental persistence and biosafety implications have intensified. From its historical adoption as a laboratory staple to its current classification as a hazardous pollutant, EtBr has transitioned from utility to liability in many research and clinical settings.

Efforts to mitigate EtBr contamination have led to the exploration of a diverse array of removal strategies. Conventional chemical degradation methods such as bleach oxidation and autoclaving, while widely practiced, may fall short in completely neutralizing the compound or may generate toxic intermediates. As a result, alternative approaches—such as adsorption using activated carbon, biochar, nanoclays, and polymeric matrices—have gained momentum due to their relative simplicity and low-cost appeal. However, issues related to adsorbent saturation, disposal, and regeneration persist.

In parallel, photocatalytic degradation methods, particularly those employing nanomaterial-based catalysts, have emerged as effective and sustainable solutions. These systems demonstrate high efficiency under UV or visible light, offering the potential for complete mineralization of EtBr. Yet, the scalability, cost, and performance of these materials in real wastewater conditions remain areas requiring deeper investigation.

This review deliberately emphasizes degradation technologies and material-based strategies over molecular-level analyses of EtBr’s DNA interactions. While such molecular studies have clarified the compound’s biological risks, our primary aim was to consolidate and critically assess the practical methodologies available for its environmental removal.

Moving forward, the development of hybrid materials and multifunctional systems, capable of combining adsorption and degradation in a single step, appears promising. Moreover, addressing current gaps—such as long-term reusability, treatment of real effluents, and eco-toxicological impact of breakdown products—will be essential for translating lab-scale success into practical, large-scale solutions. As awareness of EtBr’s hazards continues to grow, the adoption of safer alternatives and stricter disposal protocols must complement these technological advances, ensuring comprehensive protection of both human health and the environment.

Statement of Disclosure

The authors declare that they have no known competing financial interests or personal relationships that could have appeared to influence the work reported in this article. All data and sources of information used in this study have been appropriately cited and acknowledged. No funding was received for this review, and the study does not involve any conflicts of interest related to its content.

Funding

No funding was received for the preparation of this manuscript.

Abbreviations

EtBr- Ethidium bromide, DNA- Deoxyribonucleic acid, AOP- Advanced oxidation process, UV- Ultraviolet, NMR- Nuclear magnetic resonance, SWCNT- single-walled carbon nanotubes, COD- Chemical oxygen demand, NIFSS- Nutraceutical industrial fennel seed spent, FTIR- Fourier-transform infrared Spectroscopy, SEM- Scanning electron microscopy, XPS- X-ray Photoelectron Spectroscopy, EPR- Electron Paramagnetic Resonance, NP- Nanoparticles.

References

- Y. Wang et al., “Role of the sodium hydrogen exchanger in maitotoxin-induced cell death in cultured rat cortical neurons,” Elsevier, Accessed: Mar. 12, 2025. [Online]. Available: https://www.sciencedirect.com/science/article/pii/S0041010109001652.

- P. Scaria, R. S.-J. of B. Chemistry, and undefined 1991, “Binding of ethidium bromide to a DNA triple helix. Evidence for intercalation.,” Elsevier, Accessed: Mar. 12, 2025. [Online]. Available: https://www.sciencedirect.com/science/article/pii/S0021925819676118.

- Nafisi, A. Saboury, N. Keramat, … J. N.-J. of M., and undefined 2007, “Stability and structural features of DNA intercalation with ethidium bromide, acridine orange and methylene blue,” Elsevier, Accessed: Mar. 12, 2025. [Online]. Available: https://www.sciencedirect.com/science/article/pii/S0022286006004819.

- C. T. Mcmurray and K. E. Van Holde, “The binding of ethidium bromide to chromatin: model for carcinogen interactions,” 1987, Accessed: Mar. 12, 2025. [Online]. Available: https://ir.library.oregonstate.edu/concern/graduate_thesis_or_dissertations/vt150n10g.

- M. Hogan, N. Dattagupta, J. W.-J. of B. Chemistry, and undefined 1981, “Carcinogen-induced alteration of DNA structure.,” jbc.org, vol. 256, no. 9, pp. 4504–4613, 1981. [CrossRef]

- H. Hatami and M. Sieyahchehreh, “Investigating the effects of ethidium bromide on some hematological parameters in Cyprinus carpio.,” 2012, Accessed: Mar. 12, 2025. [Online]. Available: https://www.cabidigitallibrary.org/doi/full/10.5555/20143091472.

- “Ethidium Bromide – Laboratory Safety.” Accessed: Mar. 12, 2025. [Online]. Available: https://wp.stolaf.edu/chemical-hygiene/ethidium-bromide/.

- P. S. Sadalage and K. D. Pawar, “Adsorption and removal of ethidium bromide from aqueous solution using optimized biogenic catalytically active antibacterial palladium nanoparticles,” Environmental Science and Pollution Research, vol. 30, no. 2, pp. 5005–5026, Jan. 2023. [CrossRef]

- B. Heibati et al., “Adsorption of ethidium bromide (EtBr) from aqueous solutions by natural pumice and aluminium-coated pumice,” J Mol Liq, vol. 213, pp. 41–47, Jan. 2016. [CrossRef]

- R. Sulthana, S. N. Taqui, F. Zameer, U. T. Syed, and A. A. Syed, “Adsorption of ethidium bromide from aqueous solution onto nutraceutical industrial fennel seed spent: Kinetics and thermodynamics modeling studies,” Int J Phytoremediation, vol. 20, no. 11, pp. 1075–1086, Sep. 2018. [CrossRef]

- S. Novania, A. R. P. Widagdo, D. M. Prihatiningrum, S. Fauziyah, and T. H. Sucipto, “Ethidium Bromide Waste Treatment with Activated Charcoal,” EnvironmentAsia, vol. 16, no. 1, pp. 138–145, Jan. 2023. [CrossRef]

- S. A. Shaik, J. B. Shaik, and A. Goswami, “Ethidium bromide adsorption on pyrophyllite nanoclay: Insights from batch, thermodynamic, kinetic, and recyclability studies and optimization through response surface methodology,” Colloids Surf A Physicochem Eng Asp, vol. 692, p. 133900, Jul. 2024. [CrossRef]

- O. Moradi, A. Fakhri, S. Adami, and S. Adami, “Isotherm, thermodynamic, kinetics, and adsorption mechanism studies of Ethidium bromide by single-walled carbon nanotube and carboxylate group functionalized single-walled carbon nanotube,” J Colloid Interface Sci, vol. 395, pp. 224–229, Apr. 2013. [CrossRef]

- P.-H. Chang and B. Sarkar, “Mechanistic insights into ethidium bromide removal by palygorskite from contaminated water,” J Environ Manage, vol. 278, p. 111586, Jan. 2021. [CrossRef]

- P.-H. Chang et al., “Efficient ethidium bromide removal using sodium alginate/graphene oxide composite beads: Insights into adsorption mechanisms and performance,” Chemical Engineering Journal, vol. 500, p. 156379, Nov. 2024. [CrossRef]

- Z. Li, P. H. Chang, W. T. Jiang, and Y. Liu, “Enhanced removal of ethidium bromide (EtBr) from aqueous solution using rectorite,” J Hazard Mater, vol. 384, p. 121254, Feb. 2020. [CrossRef]

- Z. Ge, T. Sun, J. Xing, and X. Fan, “Efficient removal of ethidium bromide from aqueous solution by using DNA-loaded Fe 3 O 4 nanoparticles,” Environmental Science and Pollution Research, vol. 26, no. 3, pp. 2387–2396, Jan. 2019. [CrossRef]

- P. H. Chang et al., “Efficient ethidium bromide removal using sodium alginate/graphene oxide composite beads: Insights into adsorption mechanisms and performance,” Chemical Engineering Journal, vol. 500, p. 156379, Nov. 2024. [CrossRef]

- L. Wang, Z. Li, X. Zhang, G. Lv, and X. Wang, “High capacity ethidium bromide removal by montmorillonites,” Korean Journal of Chemical Engineering, vol. 37, no. 12, pp. 2202–2208, Dec. 2020. [CrossRef]

- C. Zhang, L. Liu, J. Wang, F. Rong, and D. Fu, “Electrochemical degradation of ethidium bromide using boron-doped diamond electrode,” Sep Purif Technol, vol. 107, pp. 91–101, Apr. 2013. [CrossRef]

- E. Xie, L. Zheng, A. Ding, and D. Zhang, “Mechanisms and pathways of ethidium bromide Fenton-like degradation by reusable magnetic nanocatalysts,” Chemosphere, vol. 262, p. 127852, Jan. 2021. [CrossRef]

- C. Zhang, L. Liu, J. Wang, F. Rong, and D. Fu, “Electrochemical degradation of ethidium bromide using boron-doped diamond electrode,” Sep Purif Technol, vol. 107, pp. 91–101, Apr. 2013. [CrossRef]

- B. Heibati et al., “Adsorption of ethidium bromide (EtBr) from aqueous solutions by natural pumice and aluminium-coated pumice,” J Mol Liq, vol. 213, pp. 41–47, Jan. 2016. [CrossRef]

- C. Adán, A. Martínez-Arias, M. Fernández-García, and A. Bahamonde, “Photocatalytic degradation of ethidium bromide over titania in aqueous solutions,” Appl Catal B, vol. 76, no. 3–4, pp. 395–402, Nov. 2007. [CrossRef]

- P. Sukhumungoon, P. Rattanachuay, F. Hayeebilan, and D. Kantachote, “Biodegradation of ethidium bromide by Bacillus thuringiensis isolated from soil,” Afr J Microbiol Res, vol. 7, no. 6, pp. 471–476, 2013.

- V. Gandhi, K. Kesari, A. K.- BioTech, and undefined 2022, “The identification of ethidium bromide-degrading bacteria from laboratory gel electrophoresis waste,” mdpi.comVP Gandhi, KK Kesari, A KumarBioTech, 2022•mdpi.com, 2022. [CrossRef]

- S. Amirijavid, M. Chizari, M. S.-I. J. P. B. Res, and undefined 2014, “Phytoremediation of ethidium bromide by tomato and alfalfa plants,” researchgate.netS Amirijavid, M Chizari, M SadrzadehInt J Plant Biol Res, 2014•researchgate.net, Accessed: Mar. 12, 2025. [Online]. Available: https://www.researchgate.net/profile/Shaghayegh-Amirijavid/publication/275520986_Phytoremediation_of_Ethidium_Bromide_by_Tomato_and_Alfalfa_Plants/links/553e587c0cf294deef7096c2/Phytoremediation-of-Ethidium-Bromide-by-Tomato-and-Alfalfa-Plants.pdf.

- H. Cavalcante de Almeida, A. Luís de Sá Salomão, J. Lambert, L. Cardoso Rocha Saraiva Teixeira, M. Marques, and A. S. Lu ıs de Salom, “Phycoremediation potential of microalgae species for ethidium bromide removal from aqueous media,” Taylor & FrancisHC de Almeida, ALS Salomão, J Lambert, LCRS Teixeira, M MarquesInternational Journal of Phytoremediation, 2020•Taylor & Francis, vol. 22, no. 11, pp. 1168–1174, Sep. 2020. [CrossRef]

- A. Kumar, P. Swarupa, … V. G.-I. J. of, and undefined 2017, “Isolation of ethidium bromide degrading bacteria from Jharkhand,” drive.google.com, Accessed: Mar. 12, 2025. [Online]. Available: https://drive.google.com/file/d/1nPyZDWpkSWorOVxQFF0sycU2dllMsUzB/view.

- V. Jhalora, S. Mathur, R. B.-R. J. of Pharmacy, and undefined 2024, “Screening and Evaluation of Biodegradation Potential of Bacterial Isolates Against Ethidium Bromide,” researchgate.netV Jhalora, S Mathur, R BistResearch Journal of Pharmacy and Technology, 2024•researchgate.net, Accessed: Mar. 12, 2025. [Online]. Available: https://www.researchgate.net/profile/Vandana-Jhalora/publication/381519726_Screening_and_Evaluation_of_Biodegradation_Potential_of_Bacterial_Isolates_Against_Ethidium_Bromide/links/66726b6285a4ee7261d109e8/Screening-and-Evaluation-of-Biodegradation-Potential-of-Bacterial-Isolates-Against-Ethidium-Bromide.pdf.

- K. L.-S. Visualization and undefined 2016, “The making of modern biotechnology: how ethidium bromide made fame,” sciencevision.orgK LalchhandamaScientific Visualization, 2016•sciencevision.org, Accessed: Mar. 12, 2025. [Online]. Available: https://sciencevision.org/storage/journal-articles/February2019/Qqzr9WRH7oWA55dcup5h.

- M. Waring, “Ethidium and Propidium,” Mechanism of Action of Antimicrobial and Antitumor Agents, pp. 141–165, 1975. [CrossRef]

- S. Thititananukij, R. Vejaratpimol, T. Pewnim, and A. W. Fast, “Ethidium bromide nuclear staining and fluorescence microscopy: An alternative method for triploidy detection in fish,” J World Aquac Soc, vol. 27, no. 2, pp. 213–217, 1996. [CrossRef]

- V. Singer, T. Lawlor, S. Y.-M. R. T. and, and undefined 1999, “Comparison of SYBR® Green I nucleic acid gel stain mutagenicity and ethidium bromide mutagenicity in the Salmonella/mammalian microsome reverse,” Elsevier, Accessed: Mar. 12, 2025. [Online]. Available: https://www.sciencedirect.com/science/article/pii/S1383571898001727.

- P. H. Chang, Z. Li, and W. T. Jiang, “Mechanisms of ethidium bromide removal by Ca-montmorillonite,” Desalination Water Treat, vol. 254, pp. 80–93, Apr. 2022. [CrossRef]

- “Ethidium Bromide | C21H20BrN3 | CID 14710 - PubChem.” Accessed: Mar. 12, 2025. [Online]. Available: https://pubchem.ncbi.nlm.nih.gov/compound/14710.

- T. Watkins, G. W.- Nature, and undefined 1952, “Effect of changing the quaternizing group on the trypanocidal activity of dimidium bromide,” nature.comTI Watkins, G WoolfeNature, 1952•nature.com, Accessed: Mar. 13, 2025. [Online]. Available: https://www.nature.com/articles/169506a0.

- F. Hawking, “Drug-resistance of trypanosoma congolense and other trypanosomes to quinapyramine, phenanthridines, berenil and other compounds in mice,” Ann Trop Med Parasitol, vol. 57, no. 3, pp. 262–282, 1963. [CrossRef]

- R. G. Pegram and J. M. Scott, “The prevalence and diagnosis of Trypanosoma evansi infection in camels in southern Ethiopia,” Trop Anim Health Prod, vol. 8, no. 1, pp. 20–27, Dec. 1976. [CrossRef]

- T. Leach, C. R.-P. & therapeutics, and undefined 1981, “Present status of chemotherapy and chemoprophylaxis of animal trypanosomiasis in the eastern hemisphere,” ElsevierTM Leach, CJ RobertsPharmacology & therapeutics, 1981•Elsevier, Accessed: Mar. 13, 2025. [Online]. Available: https://www.sciencedirect.com/science/article/pii/0163725881900693.

- J. B. Lepecq and C. Paoletti, “A fluorescent complex between ethidium bromide and nucleic acids: Physical—Chemical characterization,” J Mol Biol, vol. 27, no. 1, pp. 87–106, Jul. 1967. [CrossRef]

- V. W. F. Burns, “Fluorescence decay time characteristics of the complex between ethidium bromide and nucleic acids,” Arch Biochem Biophys, vol. 133, no. 2, pp. 420–424, Sep. 1969. [CrossRef]

- B. Hudson and R. Jacobs, “The ultraviolet transitions of the ethidium cation,” Biopolymers, vol. 14, no. 6, pp. 1309–1312, Jun. 1975. [CrossRef]

- S. Ramotowska, P. Spisz, J. Brzeski, A. Ciesielska, and M. Makowski, “Application of the SwitchSense Technique for the Study of Small Molecules’ (Ethidium Bromide and Selected Sulfonamide Derivatives) Affinity to DNA in Real Time,” Journal of Physical Chemistry B, vol. 126, no. 38, pp. 7238–7251, Sep. 2022. [CrossRef]

- J. Olmsted and D. R. Kearns, “Mechanism of Ethidium Bromide Fluorescence Enhancement on Binding to Nucleic Acids,” Biochemistry, vol. 16, no. 16, pp. 3647–3654, Aug. 1977. [CrossRef]

- T. Ohta, S. I. Tokishita, and H. Yamagata, “Ethidium bromide and SYBR Green I enhance the genotoxicity of UV-irradiation and chemical mutagens in E. coli,” Mutation Research/Genetic Toxicology and Environmental Mutagenesis, vol. 492, no. 1–2, pp. 91–97, May 2001. [CrossRef]

- R. Y. Ouchi, A. J. Manzato, C. R. Ceron, and G. O. Bonilla-Rodriguez, “Evaluation of the effects of a single exposure to ethidium bromide in Drosophila melanogaster (Diptera-Drosophilidae),” Bull Environ Contam Toxicol, vol. 78, no. 6, pp. 489–493, Jun. 2007. [CrossRef]

- B. A. NEWTON, “The mode of action of phenanthridines: the effect of ethidium bromide on cell division and nucleic acid synthesis,” J Gen Microbiol, vol. 17, no. 3, pp. 718–730, Dec. 1957. [CrossRef]

- R. TOMCHICK and H. G. MANDEL, “BIOCHEMICAL EFFECTS OF ETHIDIUM BROMIDE IN MICRO-ORGANISMS.,” J Gen Microbiol, vol. 36, no. 2, pp. 225–236, Aug. 1964. [CrossRef]

- V. Vacquier, J. B.- Nature, and undefined 1969, “Chromosomal abnormalities resulting from ethidium bromide treatment,” nature.comVD Vacquier, J BrachetNature, 1969•nature.com, Accessed: Mar. 21, 2025. [Online]. Available: https://www.nature.com/articles/222193a0.

- S. Singh and A. Singh, “Ethidium bromide: Is a stain turning into a pollutant? A synthesis on its status, waste management, monitoring challenges and ecological risks to the environment Issue 4 IJRAR1904431,” Oct. 2018.

- Y. Naum, D. P.-E. C. Research, and undefined 1971, “Reversible inhibition of cytochrome oxidase accumulation in human cells by ethidium bromide,” Elsevier, Accessed: Mar. 21, 2025. [Online]. Available: https://www.sciencedirect.com/science/article/pii/0014482771900103.

- N. von Wurmb-Schwark, … L. C.-… M. M. of, and undefined 2006, “A low dose of ethidium bromide leads to an increase of total mitochondrial DNA while higher concentrations induce the mtDNA 4997 deletion in a human,” Elsevier, Accessed: Mar. 21, 2025. [Online]. Available: https://www.sciencedirect.com/science/article/pii/S0027510705005336.

- J. McCann and B. N. Ames, “The Salmonella/microsome mutagenicity test: Predictive value for animal carcinogenicity,” Origins of Human Cancer, vol. 4, pp. 1431–1450, 1977.

- R. Ouchi, A. Manzato, … C. C.-B. of environmental, and undefined 2007, “Evaluation of the Effects of a Single Exposure to Ethidium Bromide in Drosophila melanogaster (Diptera-Drosophilidae),” SpringerRY Ouchi, AJ Manzato, CR Ceron, GO Bonilla-RodriguezBulletin of environmental contamination and toxicology, 2007•Springer, vol. 78, no. 6, pp. 489–493, Jun. 2007. [CrossRef]

- Z. Jiang, J. Li, G. Huang, L. Yan, and J. Ma, “Efficient removal of ethidium bromide from aqueous solutions using chromatin-loaded chitosan polyvinyl alcohol composites,” Environ Sci Pollut Res Int, vol. 31, no. 2, pp. 3276–3295, Jan. 2024. [CrossRef]

- R. Sulthana, S. N. Taqui, F. Zameer, U. T. Syed, and A. A. Syed, “Adsorption of ethidium bromide from aqueous solution onto nutraceutical industrial fennel seed spent: Kinetics and thermodynamics modeling studies,” Int J Phytoremediation, vol. 20, no. 11, pp. 1075–1086, Sep. 2018. [CrossRef]

- B. Heibati et al., “Adsorption of ethidium bromide (EtBr) from aqueous solutions by natural pumice and aluminium-coated pumice,” J Mol Liq, vol. 213, pp. 41–47, Jan. 2016. [CrossRef]

- E. Xie, L. Zheng, A. Ding, and D. Zhang, “Mechanisms and pathways of ethidium bromide Fenton-like degradation by reusable magnetic nanocatalysts,” Chemosphere, vol. 262, p. 127852, Jan. 2021. [CrossRef]

- G. Crini and E. Lichtfouse, “Advantages and disadvantages of techniques used for wastewater treatment,” Environ Chem Lett, vol. 17, no. 1, pp. 145–155, Mar. 2019. [CrossRef]

- B. Sivasankar, Biosperations: Principles and Techniques. PHI Learning Pvt. Ltd., 2005.

- G. S. Simate, N. Maledi, A. Ochieng, S. Ndlovu, J. Zhang, and L. F. Walubita, “Coal-based adsorbents for water and wastewater treatment,” J Environ Chem Eng, vol. 4, no. 2, pp. 2291–2312, Jun. 2016. [CrossRef]

- Saruchi, R. Verma, V. Kumar, and A. A. ALOthman, “Comparison between removal of Ethidium bromide and eosin by synthesized manganese (II) doped zinc (II) sulphide nanoparticles: kinetic, isotherms and thermodynamic studies,” J Environ Health Sci Eng, vol. 18, no. 2, pp. 1175–1187, Dec. 2020. [CrossRef]

- A. E.-E. H. Gad, … A. Y.-E. J. of, and undefined 2020, “Synthesis of high efficient CS/PVDC/TiO2-Au nanocomposites for photocatalytic degradation of carcinogenic ethidium bromide in sunlight,” ejchem.journals.ekb.eg, Accessed: Mar. 12, 2025. [Online]. Available: https://ejchem.journals.ekb.eg/article_69527.

- A. R. Kumar et al., “A state of the art review on the cultivation of algae for energy and other valuable products: Application, challenges, and opportunities,” Renewable and Sustainable Energy Reviews, vol. 138, p. 110649, Mar. 2021. [CrossRef]

- Lavand, Y. M.-J. of T. A. and Calorimetry, and undefined 2016, “Visible-light photocatalytic degradation of ethidium bromide using carbon- and iron-modified TiO2 photocatalyst,” SpringerAB Lavand, YS MalgheJournal of Thermal Analysis and Calorimetry, 2016•Springer, vol. 123, no. 2, pp. 1163–1172, Feb. 2016. [CrossRef]

- Lavand, Y. M.-J. of T. A. and Calorimetry, and undefined 2016, “Visible-light photocatalytic degradation of ethidium bromide using carbon- and iron-modified TiO2 photocatalyst,” SpringerAB Lavand, YS MalgheJournal of Thermal Analysis and Calorimetry, 2016•Springer, vol. 123, no. 2, pp. 1163–1172, Feb. 2016. [CrossRef]

- J. Carbajo, C. Adán, A. Rey, … A. M.-A.-A. C. B., and undefined 2011, “Optimization of H2O2 use during the photocatalytic degradation of ethidium bromide with TiO2 and iron-doped TiO2 catalysts,” Elsevier, Accessed: Mar. 12, 2025. [Online]. Available: https://www.sciencedirect.com/science/article/pii/S0926337310005163.

- S. Swetha, R. B.-C. J. of Catalysis, and undefined 2011, “Preparation and characterization of high activity zirconium-doped anatase titania for solar photocatalytic degradation of ethidium bromide,” ElsevierS Swetha, RG BalakrishnaChinese Journal of Catalysis, 2011•Elsevier, Accessed: Mar. 12, 2025. [Online]. Available: https://www.sciencedirect.com/science/article/pii/S1872206710602008.

- Adán, A. Martínez-Arias, … M. F.-G.-A. C. B., and undefined 2007, “Photocatalytic degradation of ethidium bromide over titania in aqueous solutions,” ElsevierC Adán, A Martínez-Arias, M Fernández-García, A BahamondeApplied Catalysis B: Environmental, 2007•Elsevier, Accessed: Mar. 12, 2025. [Online]. Available: https://www.sciencedirect.com/science/article/pii/S0926337307001907.

- S. Singh, V. Srivastava, I. M.-T. J. of Physical, and undefined 2013, “Mechanism of dye degradation during electrochemical treatment,” ACS Publications, vol. 117, no. 29, pp. 15229–15240, Jul. 2013. [CrossRef]

- Y. Zhu, W. Fan, W. Feng, Y. Wang, … S. L.-J. of H., and undefined 2021, “A critical review on metal complexes removal from water using methods based on Fenton-like reactions: Analysis and comparison of methods and,” Elsevier, Accessed: Mar. 12, 2025. [Online]. Available: https://www.sciencedirect.com/science/article/pii/S0304389421004805.

- A. Shokri, M. F.-E. Challenges, and undefined 2022, “A critical review in Fenton-like approach for the removal of pollutants in the aqueous environment,” Elsevier, Accessed: Mar. 12, 2025. [Online]. Available: https://www.sciencedirect.com/science/article/pii/S2667010022000920.

|

Disclaimer/Publisher’s Note: The statements, opinions and data contained in all publications are solely those of the individual author(s) and contributor(s) and not of MDPI and/or the editor(s). MDPI and/or the editor(s) disclaim responsibility for any injury to people or property resulting from any ideas, methods, instructions or products referred to in the content. |

© 2025 by the authors. Licensee MDPI, Basel, Switzerland. This article is an open access article distributed under the terms and conditions of the Creative Commons Attribution (CC BY) license (http://creativecommons.org/licenses/by/4.0/).