1. Introduction

Energy shortage and environmental pollution are urgent global crises that not only threaten the balance of ecosystems but also challenge the sustainable development of human society [1,2]. To tackle these problems, a variety of approaches have been researched and developed for improving energy efficiency, developing renewable energy sources, and adopting advanced pollution treatment technologies [3–8]. Among them, tribocatalysis is a newly emerging catalytic technology and is gaining increasing attention [9–12]. Tribocatalysis is a technology that harnesses mechanical friction energy to activate the catalytic activity of materials [13], thereby promotes chemical reactions, including degradation of organic pollutants [14–24], conversion of CO2 [17–20], and nitrogen fixation [21]. A mechanism has been established for tribocatalysis, which suggests that electron-hole pairs are excited in materials through friction and they subsequently lead to redox reactions in the surrounding environment [9].

In order to enhance the efficiency of tribocatalysis in various applications, extensive researches have been conducted. In 2023, Lei et al. reported that the introduction of some coatings in magnetically stirred tribocatalysis significantly increases the production of carbon-contained combustible gases [18]. Similarly, Cui et al. reported that the introduction of silicon single crystals as a coating in tribocatalysis greatly improves the degradation rate of Al2O3 powders that are originally chemically inert [22]. In 2024, Mao et al. suggested that the bandgap width of tribocatalysts has a direct impact on their efficiency of tribocatalysis [23]. The bandgap width directly affects materials' ability to absorb energy and the capability of electron transition, thereby influencing the efficiency of tribocatalysis [24]. Obviously, as both coatings and the bandgap width of tribocatalysts play a crucial role in tribocatalysis, it is meaningful to explore those combinations of important coatings and powders with narrow bandgap for tribocatalysis.

Cadmium sulfide (CdS) is well-known as a semiconductor material with a band gap of 2.4 eV. This material is notable for its capacity to absorb a wide range of electromagnetic radiation, resulting in significant studies on its potential use as a photocatalyst under visible light [25–30]. In addition, CdS has stood out as a notable semiconductor for tribocatalytic study [31]. In a recent paper, the effects of Al2O3 coating on the tribocatalytic degradation of organic dyes by CdS nanoparticles have been studied [24]. The Al2O3 coating increased the degradation rate constant of 50 mg/L rhodamine B (RhB) by 4.38 times and that of 20 mg/L methyl orange (MO) by 5.87 times, leading to 99.8% degradation of RhB after 8 h and 95.6% degradation of MO after 12 h of magnetic stirring. Metals exhibit superior ductility and toughness over Al2O3 ceramics, providing better structural stability in applications due to their ability to balance ultrahigh strength with excellent resistance to fracture. This makes metals more reliable for use in environments where ceramics would be prone to shattering, especially in structural applications requiring high temperatures and resistance to mechanical stress. Obviously, metallic coatings should be investigated in tribocatalytic studies of CdS.

As a matter of fact, Ti coating has been found to have surprising performance in several tribocatalytic investigations [32–37]. In this paper, we have conducted a series of experiments to study the effects of Ti coating on the tribocatalytic degradation of organic dyes by CdS nanoparticles. In particular, wide bandgap boron nitride (BN) nanoparticles have been employed to replace CdS nanoparticles in the tribocatalytic degradation of organic dyes with Ti coatings for comparison. Not only a dramatic enhancement in tribocatalytic degradation of organic dyes by CdS has been revealed for Ti coatings, MO molecules have also been found to degrade by CdS in two different modes between Al2O3 and Ti coatings. The results obtained in this paper thus should be helpful for the development of advanced, highly efficient environmental purification technologies.

2. Results

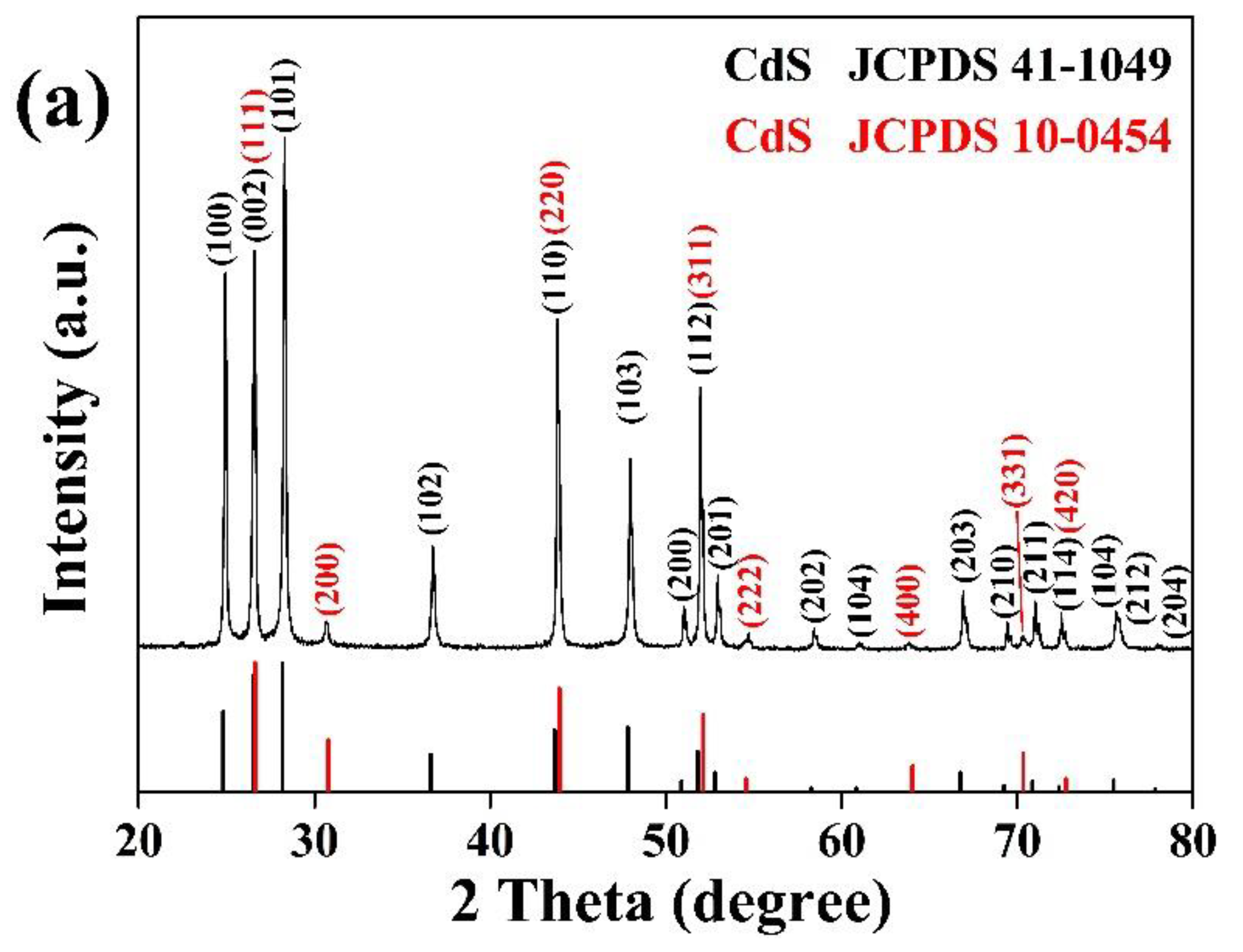

The XRD patterns of CdS and BN powders used in this study are shown in

Figure 1. Two CdS polymorphs were observed in the CdS nanoparticles: greenockite (JCPDS 41-1049) as a major phase and hawleyite (JCPDS 10-0454) as a minor phase. This is similar to a well-known commercial photocatalyst Degussa P25, in which TiO

2 nanoparticles exist in anatase (80%) and rutile (20%) phases [10]. In contrast, the BN nanoparticles display a pure crystal phase consistent with cubic BN (JCPDS 25-1033).

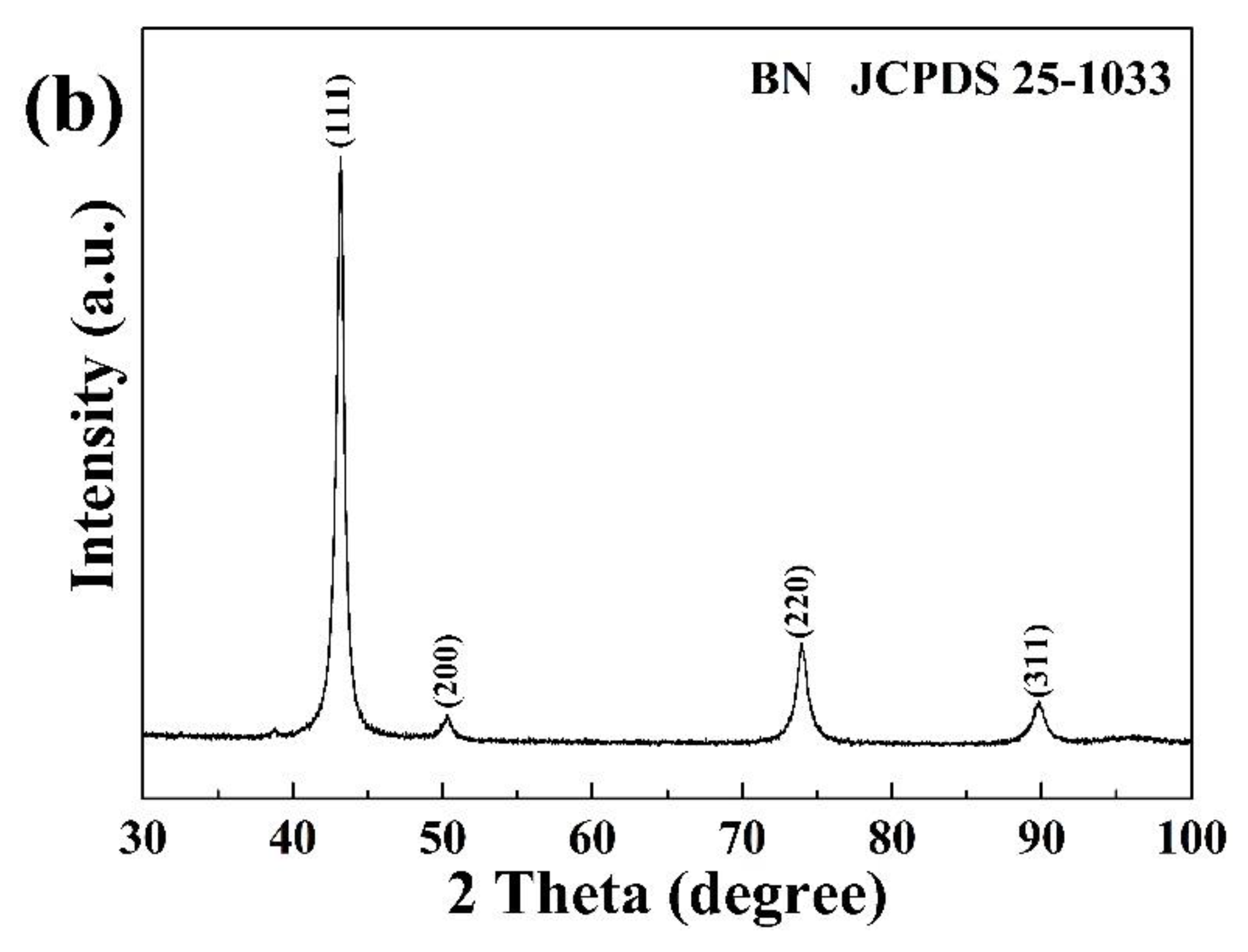

Two representative SEM images of the CdS and BN powders used in this study are displayed in

Figure 2. CdS nanoparticles exhibit a mean diameter of 140 nm, encompassing a size spectrum that spans from 50 nm up to approximately 300 nm. BN nanoparticles have an average diameter of 60 nm, with particle sizes varying from a minimum of 20 nm to a maximum of around 120 nm. Generally speaking, relatively clear edges could be observed for CdS nanoparticles, suggesting a high crystallinity.

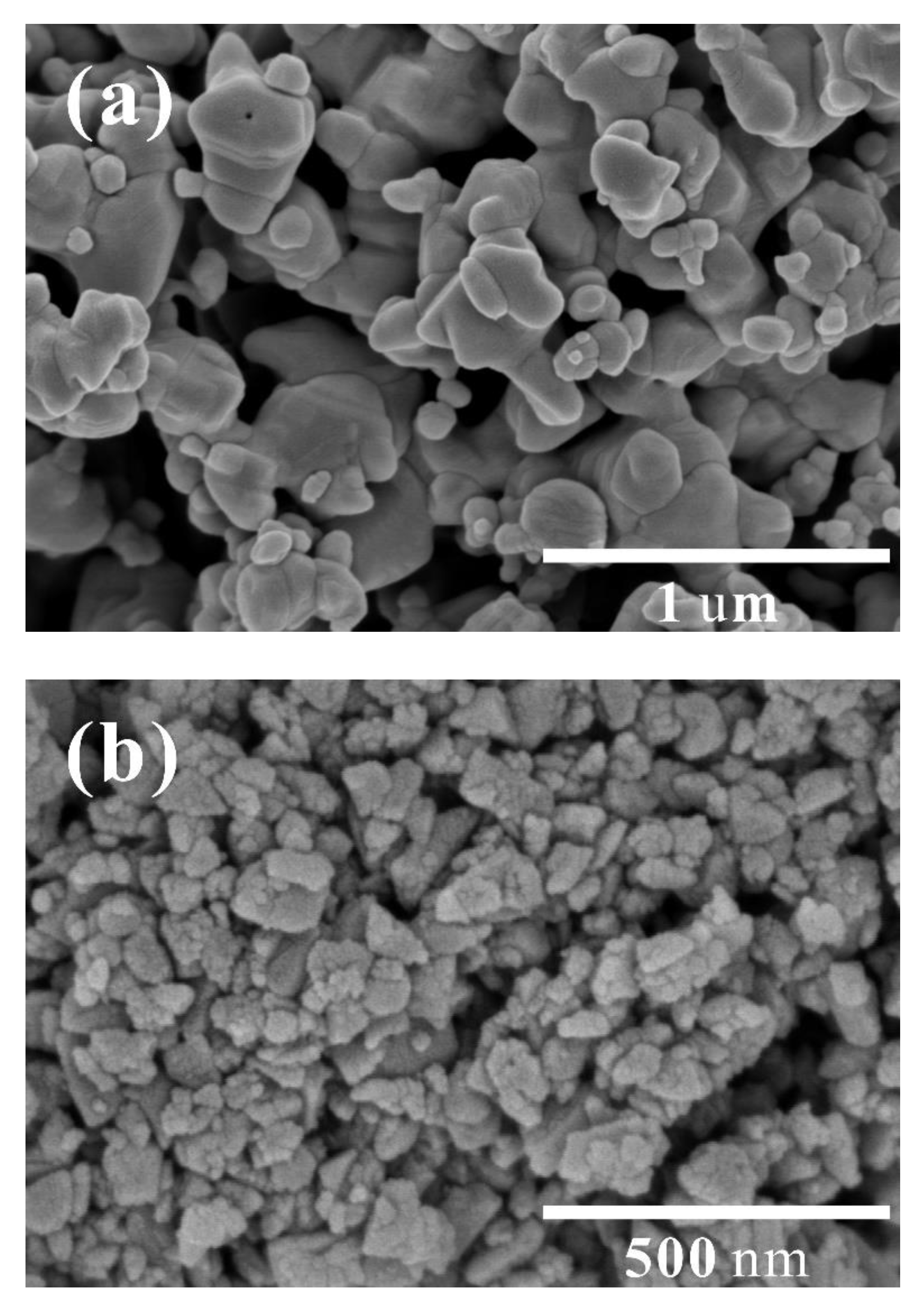

The UV-visible absorption spectra of 50 mg/L RhB solutions, subjected to tribocatalytic degradation by CdS nanoparticles in beakers with a glass bottom and with a Ti coating, are depicted in

Figure 3a,b, respectively.

Figure 3a illustrates that within the glass beaker, the 554 nm absorption peak of RhB diminished gradually as the stirring duration increased. After 9 h of magnetic stirring, the degradation efficiency reached 62.67%. Despite the significant reduction in its absorption peak, the solution maintained a vivid hue due to its initially high concentration, as illustrated in the inset of

Figure 3a. In marked contrast, the degradation of 50 mg/L RhB by CdS nanoparticles with Ti coating exhibited a significantly enhanced effect. As shown in

Figure 3b, after 6 h of magnetic stirring, the solution became colorless, and the 554 nm absorption peak in the UV-visible spectrum nearly vanished. Clearly, the presence of a Ti coating significantly increased the tribocatalytic degradation efficiency of RhB by CdS nanoparticles.

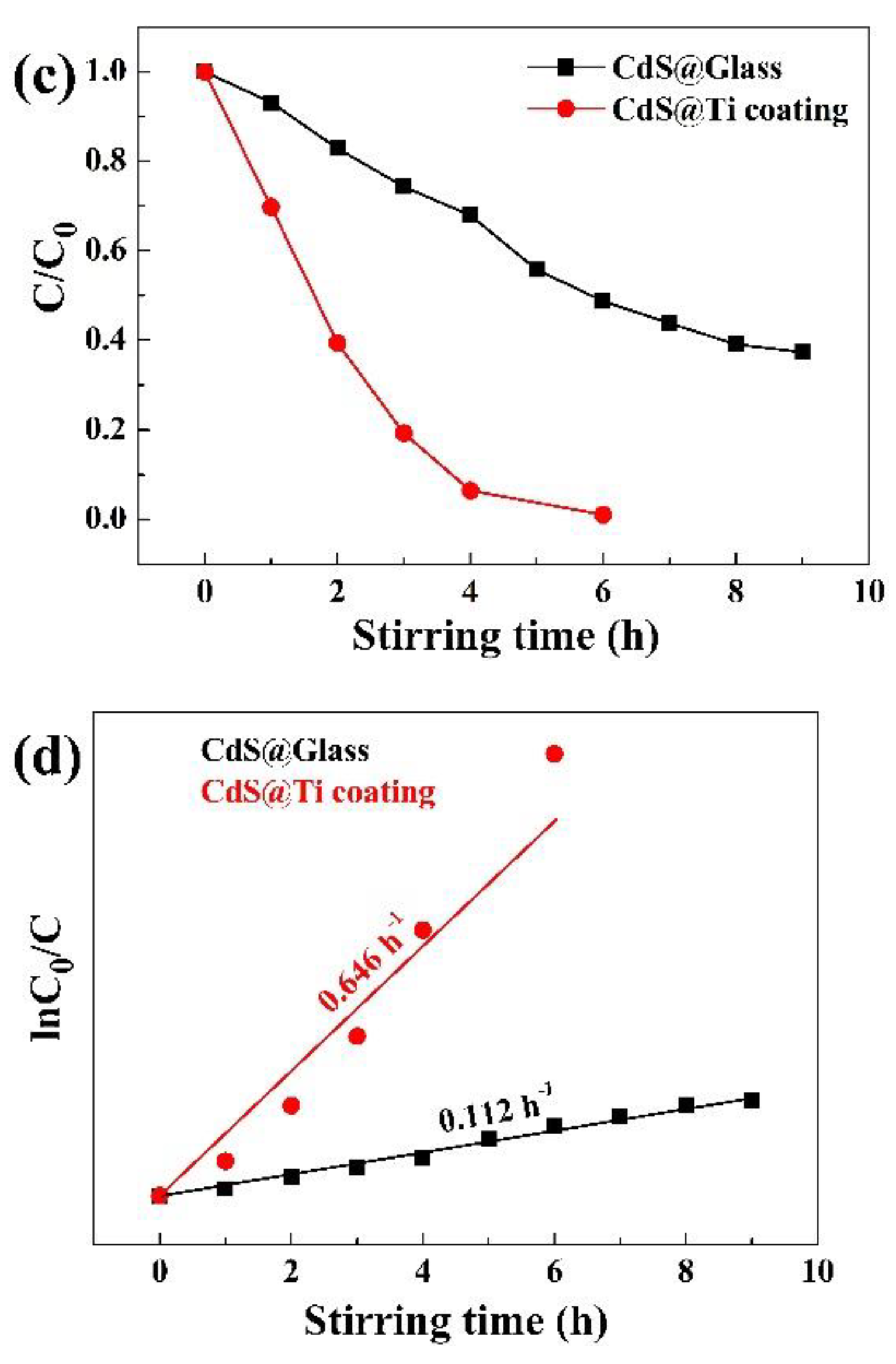

Figure 3c illustrates a comparative study of the degradation efficiency of RhB solution catalyzed by CdS nanoparticles on different types of beakers over time. Concurrently,

Figure 3d provides the pseudo-first-order kinetic model fitting for the RhB solution's degradation efficiency. The degradation rate constants for CdS nanoparticles on glass and Ti coating were 0.112 h

−1 and 0.646 h

−1, respectively, indicating that the Ti coating increased the degradation rate constant of CdS nanoparticles by 4.77 times.

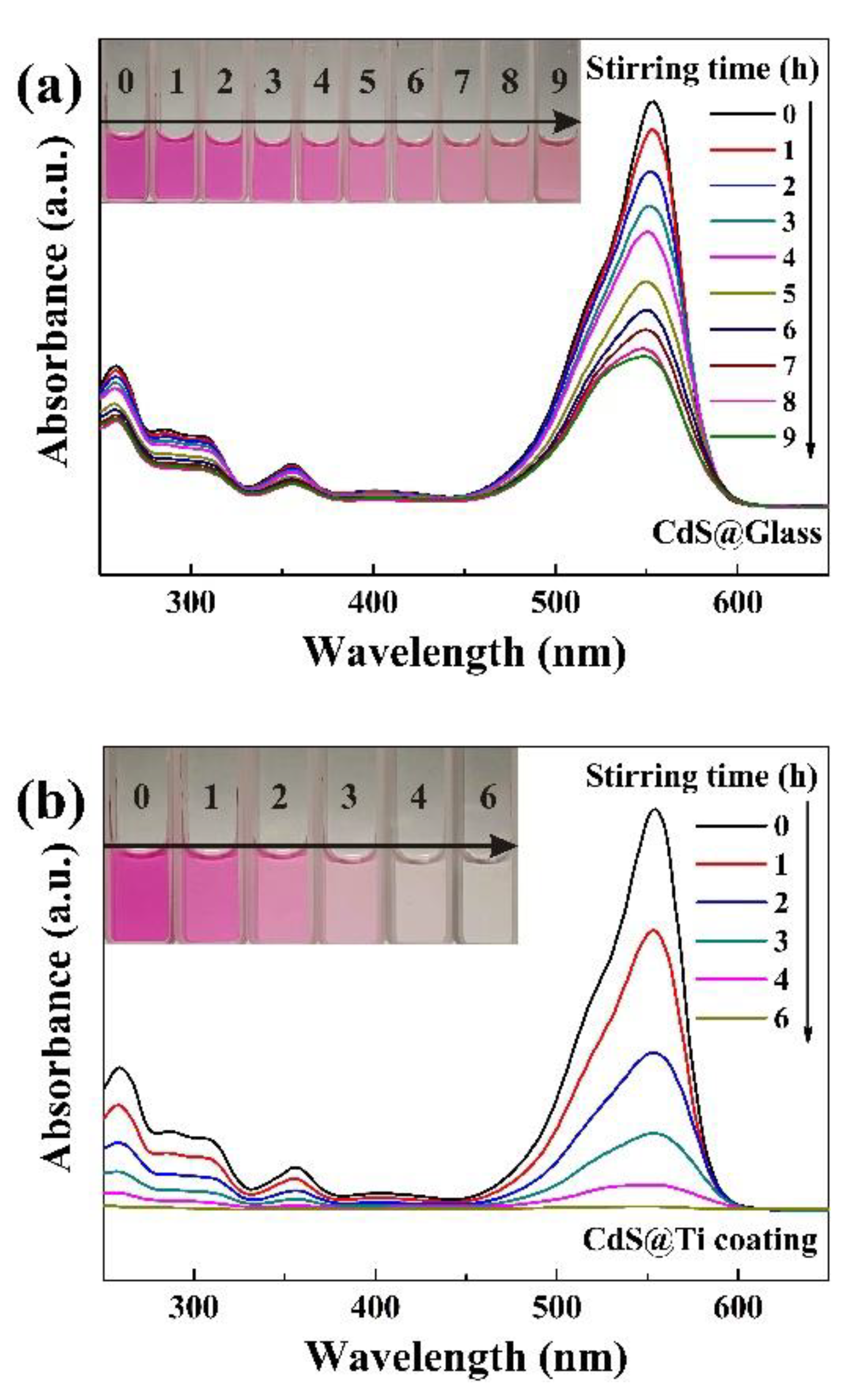

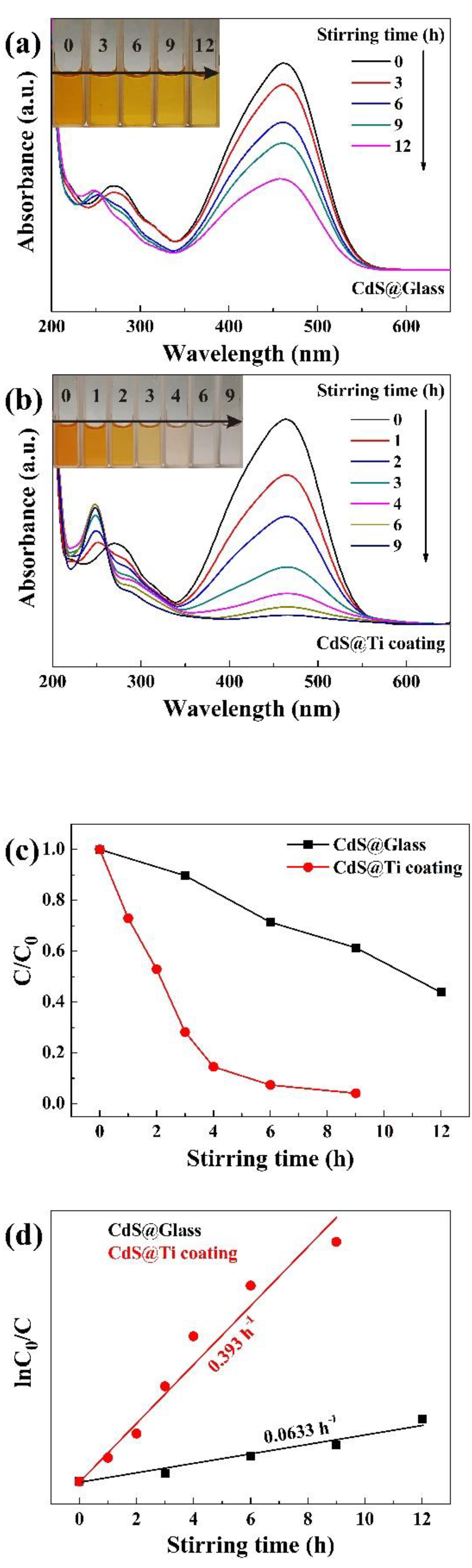

The UV-visible absorption spectra of 20 mg/L MO solutions, subjected to tribocatalytic degradation by CdS nanoparticles in beakers with a glass bottom and with a Ti coating, are depicted in

Figure 4a,b, respectively.

Figure 4a illustrates that within the glass beaker, the 464 nm absorption peak of MO diminished gradually as the stirring duration increased. Following 12 h of magnetic stirring, the efficiency of degradation achieved 56.21%. Concurrently, as the 464 nm peak diminished, a novel absorption peak emerged at 250 nm in the UV region. This observation aligns with prior research, which suggests that MO molecules were merely fragmented into smaller organic molecules, such as benzoic acid, succinic acid, and hydroquinone [22]. The inherent presence of high-energy bonds (C=N and N=N) in MO's molecular structure renders it relatively recalcitrant to degradation compared to other common organic dyes, making the slow degradation by CdS on glass quite typical. In marked contrast, the degradation of 20 mg/L MO by CdS nanoparticles with a Ti coating exhibited a significantly enhanced effect.

Figure 4b illustrates that after 9 h of magnetic stirring, the solution turned colorless, and the absorption peak at 464 nm in the UV-visible spectrum almost disappeared. As a semiconductor with a relatively narrow band-gap (2.4 eV), CdS is commonly used in photocatalytic research [25,26]. It is evident that the Ti coating significantly enhances the degradation efficiency of CdS nanoparticles in the tribocatalytic breakdown of both RhB and MO.

Figure 4c compares the degradation efficiency of the MO solution catalyzed by CdS nanoparticles over time in the two different types of beakers, whereas

Figure 4d shows the pseudo-first-order kinetic fitting for the MO solution's degradation efficiency. The degradation rate constants for CdS nanoparticles on glass and Ti coatings were 0.0633 h

−1 and 0.393 h

−1, respectively, which suggests that the Ti coating has increased the degradation rate constant of CdS nanoparticles by a factor of 5.21.

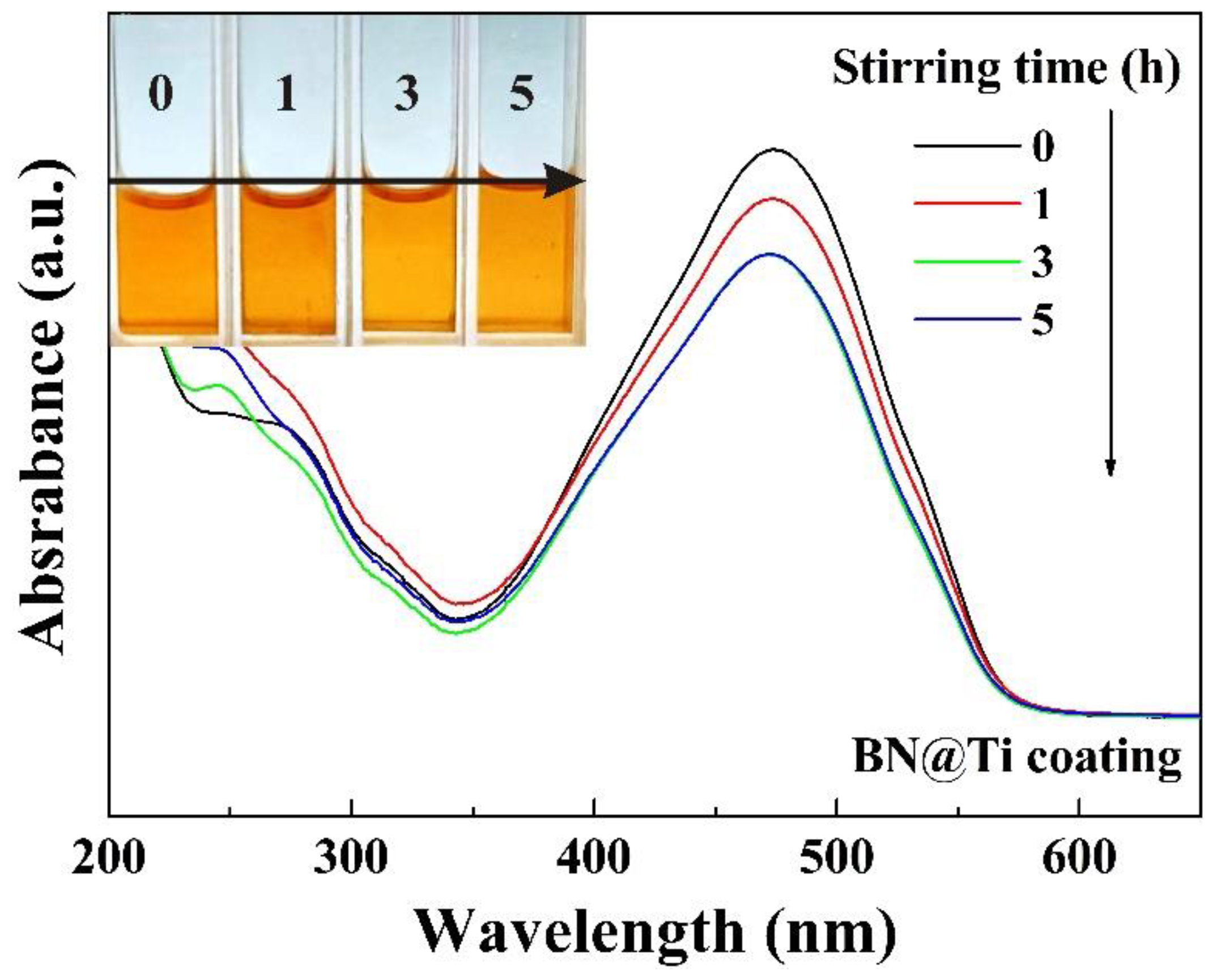

In a previous investigation, Si single crystals have been employed as coatings to degrade MO solutions through friction [22]. A quick de-coloration can be observed when many kinds of powders, including α-Al

2O

3, are dispersed in the solutions and driven to rub against Si coatings through magnetic stirring. As a result, it has been concluded that mechanical energy has been absorbed by Si single crystals for the de-coloration, or the catalytic effect has arisen from Si coatings. Similarly, it is possible for Ti coatings to be mainly responsible for the absorption of mechanical energy in this study. To verify this, BN nanoparticles were dispersed in 20 mg/L MO solution in a Ti-coated beaker and were driven to rub against Ti coating through magnetic stirring. The UV-visible absorption spectra of the 20 mg/L MO solution in the course of magnetic stirring are shown in

Figure 5. It can be observed that the degradation was very slow and the color of the solution hardly changed even after 5 h of magnetic stirring. This forms a sharp contrast with that for CdS nanoparticles shown in

Figure 4b. BN has a wide band gap of 6.3 eV [38–40]. This suggests that the enhancement of Ti coatings on the tribocatalytic degradation is related to the band gap of the tribocatalysts. On the other hand, Ti coatings cannot initiate the quick de-coloration as Si single crystals do through friction, either.

3. Discussion

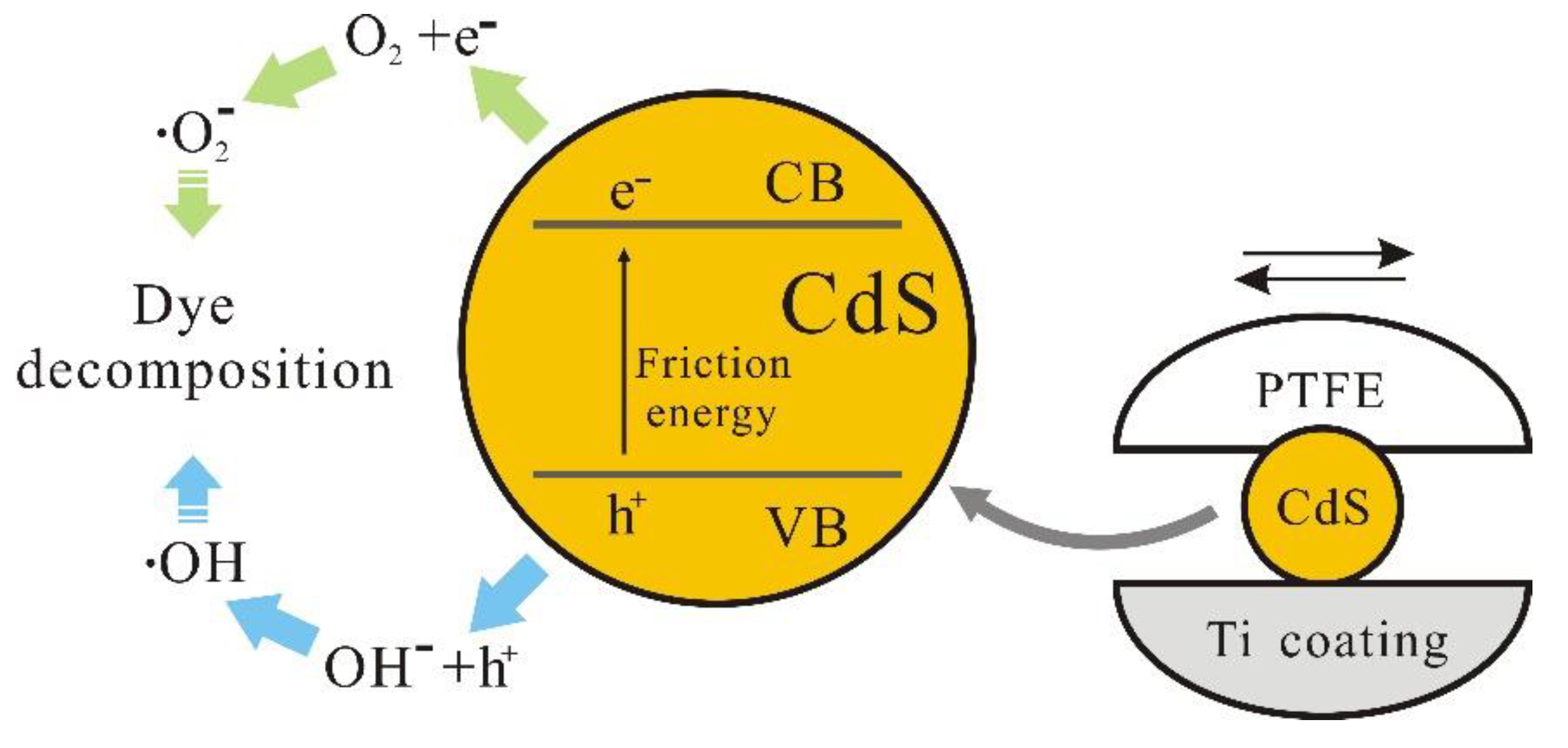

The application of coatings to the interior surfaces of beakers or reactors has proven to be a straightforward and efficacious approach for boosting or controlling the tribocatalytic breakdown of organic contaminants and the conversion of H

2O and CO

2 [13]. The beneficial impact of these coatings is largely ascribed to the frictional forces that arise during their interaction with the catalysts. In particular, the improved organic dye degradation by CdS nanoparticles in beakers with Ti coatings suggests that the frictional interaction between the Ti surface and the nanoparticles is a critical factor. This concept is graphically elucidated in a schematic representation of the tribocatalysis mechanism, as depicted in

Figure 6.

Based on the electronic transition mechanism of tribocatalysis [

9], the mechanical energy generated by friction stimulates the formation of electron-hole pairs in CdS, which can be represented as:

Subsequently, holes interact with hydroxide ions, resulting in the creation of hydroxyl radicals, and electrons engage in reactions with oxygen, leading to the formation of superoxide radicals, as follows:

Hydroxyl and superoxide radicals subsequently undergo reactions with organic dyestuffs, facilitating the degradation of these dyes and their transformation into non-polluting, smaller molecular entities:

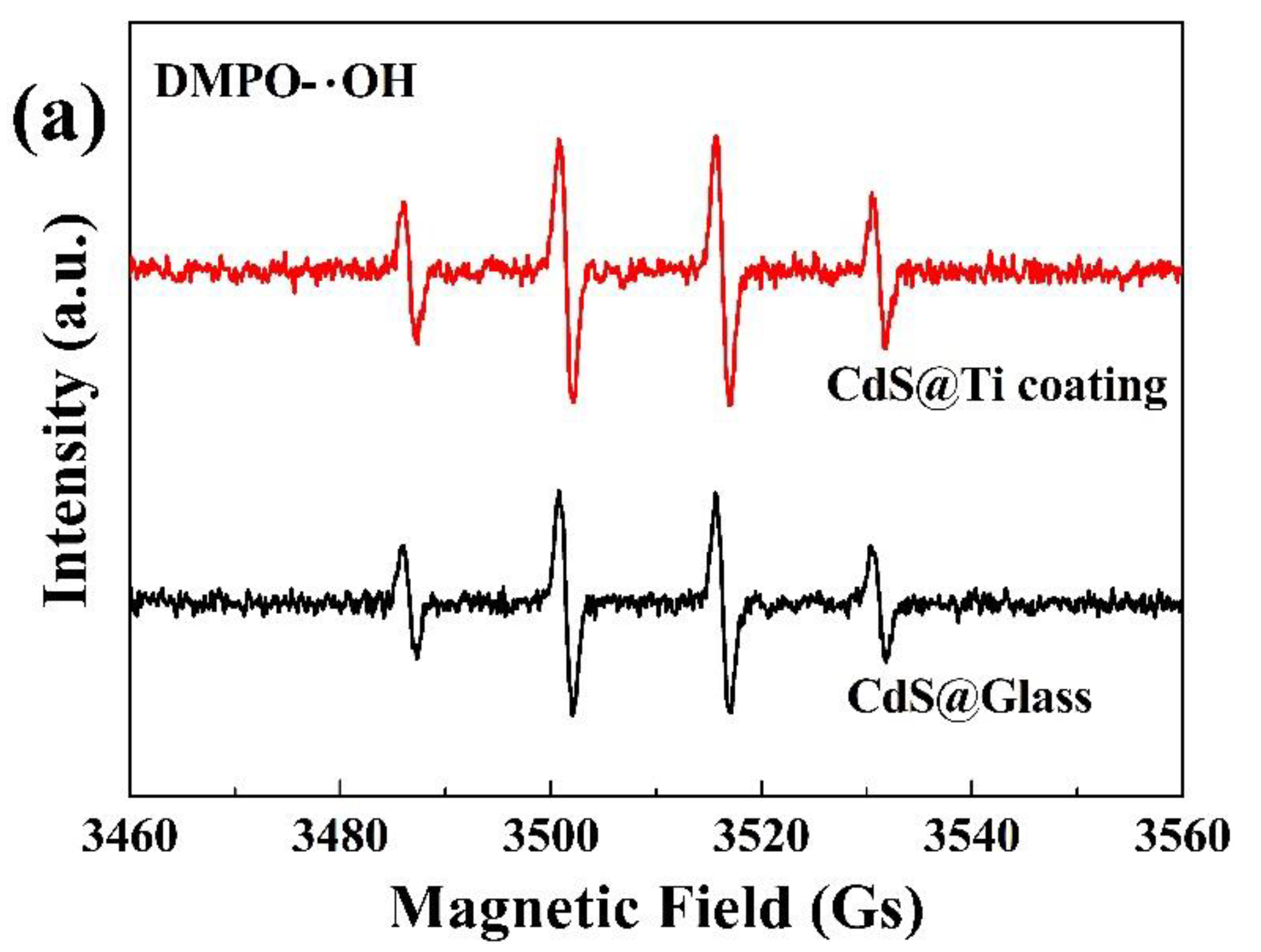

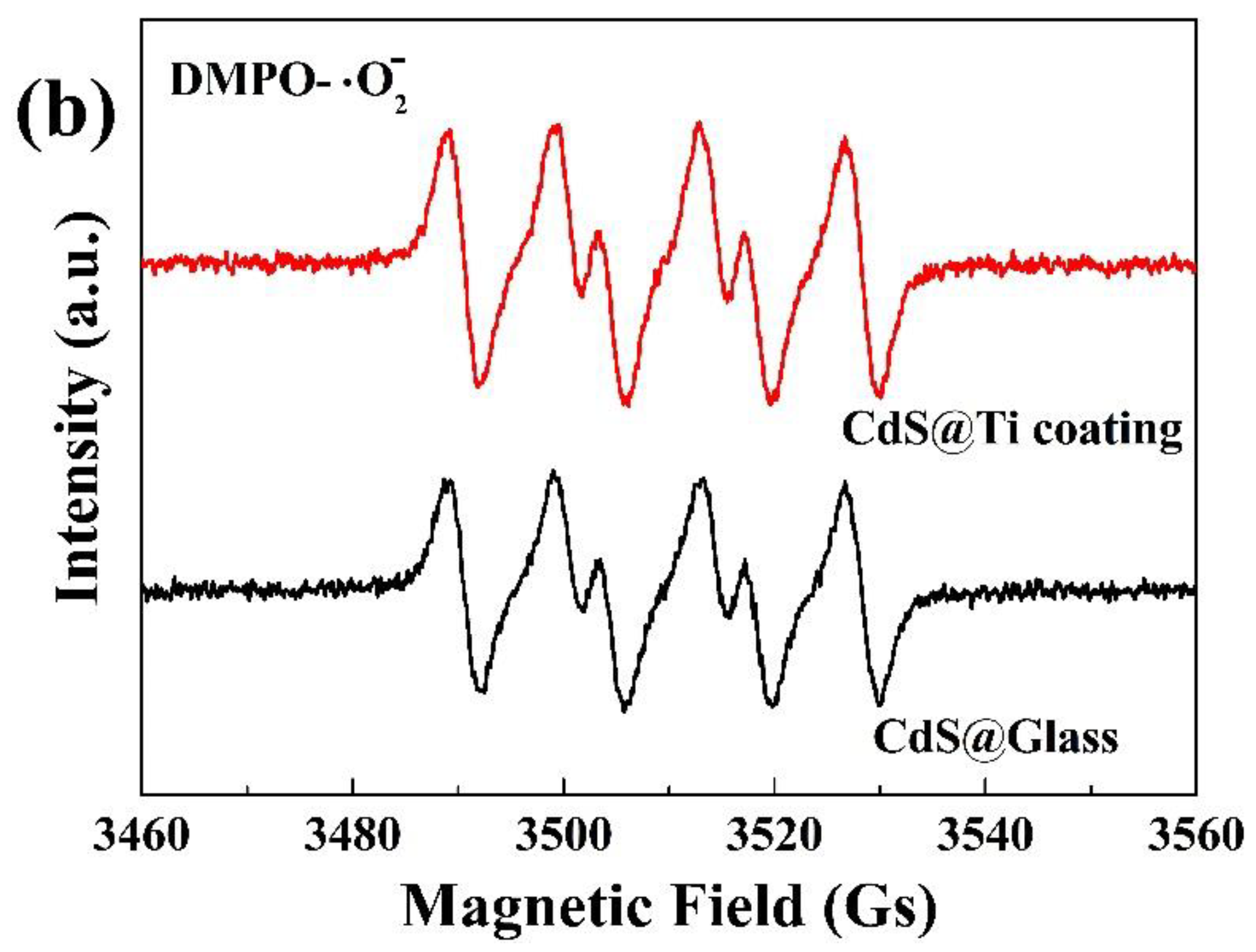

CdS nanoparticles, when subjected to magnetic stirring, produce hydroxyl and superoxide radicals, as evidenced by EPR spectroscopy obtained with microwave frequency at 9.85 GHz and modulation frequency at 100 kHz. The findings are depicted in

Figure 7. Notably, after 15 min magnetic stirring of the nanoparticles in deionized water, a clear set of four characteristic peaks for hydroxyl radicals, with a ratio of (1:2:2:1), were discernible in both glass and Ti-coated beakers (

Figure 7a). Similarly, upon stimulation in methanol, four distinct peaks for superoxide radicals, with a ratio of (1:1:1:1), were observed (

Figure 7b). It is also evident that the intensity of the peaks for both types of radicals is greater in the Ti-coated beaker compared to the glass one, indicating a higher generation of radicals with the Ti coating.

It is worthy to note that Al

2O

3 coating has also been found to show a strong enhancement in the tribocatalytic degradation of MO solutions by CdS nanoparticles [24], while there is a huge difference between them: In the UV-visible absorption spectra depicted in

Figure 4(b), the peak at 250 nm, which is associated with the Ti coating, was not present when the coating was Al

2O

3.. It indicates that with Al

2O

3 coating, MO molecules are degraded by CdS nanoparticles mostly into CO

2 and H

2O; while with Ti coating, MO molecules are degraded by CdS nanoparticles only into smaller organic molecules like benzoic acid, succinic acid, and hydroquinone [41–43]. Such a difference has been quite unexpected and is difficult to understand at present.

RhB and MO are only two examples for organic pollutants. It is expected that Ti coating also should be able to greatly enhance the tribocatalytic degradation of other organic pollutants by CdS. As coating disk-shaped Ti and other materials on the bottoms of vessels can be readily scaled up, Ti and other coatings will play vital roles in future tribocatalytic applications. On the other hand, many findings related with effects of coatings in tribocatalysis, including these in this study, cannot be explained explicitly. Further studies are highly desirable to reveal in-depth the interactions between coatings and catalysts in tribocatalysis, which are crucial for the development of tribocatalysis both practically and theoretically.

4. Materials and Methods

4.1. Materials and Characterization

High-purity commercial CdS nanoparticles (99.99 wt%) and BN nanoparticles (99.9 wt%) were utilized in this research. The CdS nanoparticles were purchased from Shanghai Aladdin Biochemical Technology Co., Ltd. (Shanghai, China). The BN nanoparticles were purchased from Shanghai Yaotian New Material Technology Co., Ltd. (Shanghai, China). The crystalline structure of the nanoparticles was analyzed using an X-ray diffractometer (XRD, Philips X-ray diffractometer system) with Cu Kα radiation. The morphology of the nanoparticles was observed using a field-emission scanning electron microscope (FESEM, JEOL JSM-6700F). The diameter of the nanoparticles was estimated through the software Nano Measure, which quantified the sizes of a large number of particles in SEM images by marking them and obtained the average value, as well as the maximum and minimum values.

4.2. Formation of Ti Coating on the Bottom of Glass Beakers

For the tribocatalytic experiments, commercial flat-bottomed glass beakers with dimensions of φ 45 mm × 60 mm were divided into two groups. The first group consisted of as-received glass beakers, while beakers in the second group were modified through pasting Ti disks (φ 40 mm × 1 mm) on their bottoms using a strong adhesive (deli super glue 502) prior to use. This process resulted in two distinct types of beakers: some with glass bottoms and others with Ti-coated bottoms.

4.3. Tribocatalytic Degradation of RhB and MO Solutions

For organic dye solutions, usually the higher concentration the greater challenge for degradation. To fully explore the tribocatalytic performance of CdS nanoparticles, relatively concentrated 50 mg/L RhB solutions and 20 mg/L MO solutions were employed in this study. In an experiment, 0.30 g of CdS nanoparticles were introduced into a glass beaker containing 30 ml of a solution, which was either 50 mg/L of RhB or 20 mg/L of MO. A homemade Teflon magnetic stirrer, the specifics of which were described in an earlier publication [13], was used to agitate the suspension at a rate of 400 rpm. The ambient temperature was maintained at 25°C, and the beaker was kept in darkness. At regular intervals, 1 mL of the solution was extracted and centrifuged at 8000 rpm for 5 min to separate CdS nanoparticles. The absorbance of the supernatant was measured using a UV-visible spectrometer (UV-2550; Shimadzu, Kyoto, Japan) over the range of 250-650 nm for RhB solution and 200-650 nm for MO solution. The efficiency of organic dye degradation is typically calculated using the equation D = 1−A/A0, with A0 and A denoting the initial and remaining absorbance at the dye's characteristic peak, respectively.

4.4. Detection of Radical Species

In the process of detecting hydroxyl radicals, two separate glass beakers, each with a glass bottom and titanium coating, were filled with 10 mL of deionized water, 50 µL of 5, 5-dimethyl-1-pyrroline-N-oxide (DMPO), and 0.15 g of CdS nanoparticles. For the detection of superoxide radicals, the same setup was used but with 10 mL of methanol instead of deionized water. Each beaker was equipped with a Teflon magnetic rotary disk to agitate the mixture at a speed of 400 rpm for 15 min in a dark environment at ambient temperature. Hydroxyl and superoxide radicals were then detected using an electron paramagnetic resonance (EPR) spectrometer (A300-10/12, Bruker, Berlin, Germany).

5. Conclusions

The use of Ti-coated disks at the bottom of the beakers successfully intensified the tribocatalytic degradation of 50 mg/L RhB and 20 mg/L MO solutions by CdS nanoparticles. In Ti-coated beakers dispersed with CdS nanoparticles, the RhB and MO solutions were completely degraded after 6 h and 9 h of magnetic stirring, respectively; while in as-received glass-bottomed beakers, only 62.67% of the RhB solution and 56.21% of the MO solution were degraded after 9 h and 12 h of magnetic stirring, respectively. Ti coating increased the degradation rate constant by 4.77 and 5.21 times for RhB and MO, respectively. However, the MO degradation mode associated with Ti coatings was surprisingly different from that previously revealed for Al2O3 coatings. Electron paramagnetic resonance (EPR) spectroscopy analyses showed that the friction between CdS and Ti was more effective for radical formation than that between CdS and glass, and the interaction between CdS and Ti rather than Ti itself was revealed responsible for the enhancement through replacing CdS with BN nanoparticles to form friction with Ti. Coating disk-shaped materials on the bottoms of vessels is highly effective for tribocatalysis enhancement and should be widely adopted in various tribocatalytic applications.

Author Contributions

Conceptualization, M.Z. and Z.S.; methodology, M.Z., J.S. and S.K.; validation, M.Z., Y.G. and Z.S.; formal analysis, M.Z. and Z.S.; investigation, L.B. and Z.S.; data curation, Z.S.; writing—original draft preparation, M.Z.; writing—review and editing, L.B., Z.S. and W.C; visual-ization, Z.S. and W.C; supervision, Z.S. and W.C.; project administration, L.B. and Z.S.; funding acquisition, L.B. and Z.S. All authors have read and agreed to the published version of the manuscript.

Funding

This work was financially supported by the Natural Science Foundation of Hainan Province under Grant No. 220RC595, and the National Natural Science Foundation of China under Grant No. 11304069. Support from the specific research fund of the Innovation Platform for Academicians of Hainan Province (YSPTZX202207), Key Laboratory of Laser Technology and Optoelectronic Functional Materials of Hainan Province and the Innovational Fund for Scientific and Technological Personnel of Hainan Province under Grant No. KJRC2023C05 are also acknowledged.

Data Availability Statement

The data underlying this article will be shared on reasonable request to the corresponding author.

Conflicts of Interest

The authors declare no conflicts of interest.

References

- Ren, G.; Ye, J.; Hu, Q.; Zhang, D.; Yuan, Y.; Zhou, S. Growth of electroautotrophic microorganisms using hydrovoltaic energy through natural water evaporation. Nat. Commun. 2024, 15, 4992. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Zhang, G.; Li, Y.; Zhao, C.; Gu, J.; Zhou, G.; Shi, Y.; Zhou, Q.; Xiao, F.; Fu, W.; Chen, Q.; Ji, Q.; Qu, J.; Liu, H. Redox-neutral electrochemical decontamination of hypersaline wastewater with high technology readiness level. Nat. Nanotechnol. 2024, 19, 1130–1140. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Raccichini, R.; Varzi, A.; Passerini, S.; Scrosati, B. The role of graphene for electrochemical energy storage. Nat. Mater. 2015, 14, 271–279. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- You, V.; Kakinaka, M. Modern and traditional renewable energy sources and CO2 emissions in emerging countries. Environ. Sci. Pollut. Res. 2022, 29, 17695–17708. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Goti, G.; Manal, K.; Sivaguru, J.; Dell’Amico, L. The impact of UV light on synthetic photochemistry and photocatalysis. Nat. Chem. 2024, 16, 684–692. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Xiang, H.; Yang, S.; Talukder, E.; Huang, C.; Chen, K. Research and Application Progress of Inverse Opal Photonic Crystals in Photocatalysis. Inorganics 2023, 11, 337. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Linsebigler, A.; Lu, G.; Jr, J. Photocatalysis on TiO2 Surfaces: Principles, Mechanisms, and Selected Results. Chem. Rev. 1995, 95, 735–758. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Asahi, R.; Morikawa, T.; Ohwaki, T.; Aoki, K.; Taga, Y. Visible-Light Photocatalysis in Nitrogen-Doped Titanium Oxides. Science 2001, 293, 269–271. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Li, P.; Wu, J.; Wu, Z.; Jia, Y.; Ma, J.; Chen, W.; Zhang, L.; Yang, J.; Liu, Y. Strong tribocatalytic dye decomposition through utilizing triboelectric energy of barium strontium titanate nanoparticles. Nano Energy 2019, 63, 103832. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Li, P.; Tang, C.; Xiao, X.; Jia, Y.; Chen, W. Flammable gases produced by TiO2 nanoparticles under magnetic stirring in water. Friction. 2022, 10, 1127–1133. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Cui, X.; Li, P.; Lei, H.; Tu, C.; Wang, D.; Wang, Z.; Chen, W. Greatly enhanced tribocatalytic degradation of organic pollutants by TiO2 nanoparticles through efficiently harvesting mechanical energy. Sep. Purif. Technol. 2022, 289, 120814. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Lei, H.; Cui, X.; Jia, X.; Qi, J.; Wang, Z.; Chen, W. Enhanced Tribocatalytic Degradation of Organic Pollutants by ZnO Nanoparticles of High Crystallinity. Nanomaterials 2023, 13, 46. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Li, X.; Tong, W.; Shi, J.; Chen, Y.; Zhang, Y.; An, Q. Tribocatalysis mechanisms: electron transfer and transition. J. Mater. Chem. A 2023, 9, 4458–4472. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Wu, M.; Xu, Y.; He, Q.; Sun, P.; Weng, X.; Dong, X. Tribocatalysis of homogeneous material with multi-size granular distribution for degradation of organic pollutants. J. Colloid Interface Sci. 2022, 622, 602–611. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Kumar, M.; Gaur, A.; Chauhan, V. Tribocatalytic dye degradation using BiVO4. Ceram. Int. 2024, 5, 8360–8369. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Xu, Y.; Meng, Y.; Xiang, X.; Tang, Q.; Zhang, H.; Liu, L.; Gao, J.; Xu, B.; Liang, R.; Shu, L.; Jia, Y.; Chen, W. Modulating low-frequency tribocatalytic performance through defects in uni-doped and bi-doped SrTiO3. J. Adv. Ceram. 2024, 13, 1153–1163. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Cui, X.; Wang, H.; Lei, H.; Jia, X.; Jiang, Y.; Fei, L.; Jia, Y.; Chen, W. Surprising Tribo-catalytic Conversion of H2O and CO2 into Flammable Gases utilizing Frictions of Copper in Water. ChemistrySelect 2023, 8, e202204146. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Lei, H.; Jia, X.; Wang, H.; Cui, X.; Jia, Y.; Fei, L.; Chen, W. Tribo-Catalytic Conversions of H2O and CO2 by NiO Particles in Reactors with Plastic and Metallic Coatings. Coatings 2023, 13, 396. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Jia, X.; Wang, H.; Lei, H.; Mao, C.; Cui, X.; Liu, Y.; Jia, Y.; Yao, W.; Chen, W. Boosting tribo-catalytic conversion of H2O and CO2 by Co3O4 nanoparticles through metallic coatings in reactors. J. Adv. Ceram. 2023, 12, 1833–1843. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Lei, H.; Wu, Z.; Wang, H.; Mao, C.; Guo, Z.; Fei, L.; Chen, W. Converting H2O and CO2 into chemical fuels by nickel via friction. Surf. Interfaces. 2024, 46, 104203. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Wu, Z.; Xu, T.; Ruan, R.; Guan, J.; Huang, S.; Dong, X.; Li, H.; Jia, Y. Strong Tribocatalytic Nitrogen Fixation of Graphite Carbon Nitride g-C3N4 through Harvesting Friction Energy. Nanomaterials 2022, 12, 1981. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Cui, X.; Guo, Z.; Lei, H.; Jia, X.; Mao, C.; Ruan, L.; Zhou, X.; Wang, Z.; Chen, F.; Chen, W. Tribo-Catalytic Degradation of Methyl Orange Solutions Enhanced by Silicon Single Crystals. Coatings 2023, 13, 1804. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Mao, C.; Zhang, Y.; Lei, H.; Jia, X.; Chen, F.; Yao, W.; Liu, P.; Chen, W. Boosting tribo-catalytic degradation of organic pollutants by BaTiO3 nanoparticles through metallic coatings. Appl. Surf. Sci. 2024, 663, 160172. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Ke, S.; Mao, C.; Luo, R.; Zhou, Z.; Hu, Y.; Zhao, W.; Chen, W. Surprising Effects of Al2O3 Coating on Tribocatalytic Degradation of Organic Dyes by CdS Nanoparticles. Coatings 2024, 14, 1057. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Jie, L.; Gao, X.; Cao, X.; Wu, S.; Long, X.; Ma, Q.; Su, J. A review of CdS photocatalytic nanomaterials: Morphology, synthesis methods, and applications. Mater. Sci. Semicond. Process. 2024, 176, 108288. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Fard, N.; Fazaeli, R.; Ghiasi, R. Band Gap Energies and Photocatalytic Properties of CdS and Ag/CdS Nanoparticles for Azo Dye Degradation. Chem. Eng. Technol. 2016, 39, 149–157. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Dou, F.; Harvey, S.; Mason, K.; Homer, M.; Gamelin, D.; Cossairt, B. Effect of a redox-mediating ligand shell on photocatalysis by CdS quantum dots. J. Chem. Phys. 2023, 158, 184705. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Xia, Z.; Yu, R.; Yang, H.; Luo, B.; Huang, Y.; Li, D.; Shi, J.; Xu, D. Novel 2D Zn-porphyrin metal organic frameworks revived CdS for photocatalysis of hydrogen production. Int. J. Hydrogen Energy 2022, 47, 13340–13350. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Seo, O.; Azizar, G.; Hong, J. Band Multi-synergies of hollow CdS cubes on MoS2 sheets for enhanced visible-light-driven photocatalysis. Appl. Surf. Sci. 2024, 655, 159552. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Wang, X.; Zhao, F.; Zhang, W. Band Hollow Spherical Pd/CdS/NiS with Carrier Spatial Separation for Photocatalytic Hydrogen Generation. Nanomaterials 2023, 13, 1326. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Yang, B.; Chen, H.; Guo, X.; Wang, L.; Xu, T.; Bian, J.; Yang, Y.; Liu, Q.; Du, Y.; Lou, X. , Enhanced tribocatalytic degradation using piezoelectric CdS nanowires for efficient water remediation. J. Mater. Chem. C. 2020, 8, 14845–14854. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Xu, X.; Mao, C.; Song, J.; Ke, S.; Hu, Y.; Chen, W.; Pan, C. Surprising Effects of Ti and Al2O3 Coatings on Tribocatalytic Degradation of Organic Dyes by GaN Nanoparticles. Materials 2024, 17, 3487. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Yang, X.; Ma, W.; Zhang, Z.; Liu, S.; Tang, H. Ultra-high specific strength Ti6Al4V alloy lattice material manufactured via selective laser melting. Mater. Sci. Eng. A. 2022, 840, 142956. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Lu, Y.; Liu, L.; Mandler, D.; Lee, P. S. High switching speed and coloration efficiency of titanium-doped vanadium oxide thin film electrochromic devices. J. Mater. Chem. C. 2013, 1, 7380–7386. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Qu, J.; Fu, Y.; Meng, X.; He, Y.; Sun, H.; Yang, R.; Wang, H.; Su, Z. A porous Ti-based metal-organic framework for CO. Chem. Commun. 2023, 59, 1070–1073. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Zhang, J.; Yang, Q.; Matsushita, T.; Sun, S.; Tatsuoka, H. Growth of brookite TiO2 nanorods by thermal oxidation of Ti metal in air. J. Mater. Sci.: Mater. Electron. 2024, 35, 1520. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Dai, D.; Qiu, J.; Zhang, L.; Ma, H.; Yao, J. Amino-functionalized Ti-metal-organic framework decorated BiOI sphere for simultaneous elimination of Cr(VI) and tetracycline. J. Colloid Interface Sci. 2022, 607, 933–941. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Beiranvand, R.; Valedbagi, S. Electronic and optical properties of advance semiconductor materials: BN, AlN and GaN nanosheets from first principles. Optik 2016, 127, 1553–1560. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Nag, A.; Raidongia, K.; Hembram, K.; Datta, R.; Waghmare, U.; Rao, C. Graphene Analogues of BN: Novel Synthesis and Properties. Acs Nano 2010, 4, 1539–1544. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Gupta, S.; Joshi, P.; Sachan, R.; Narayan, J. Fabricating Graphene Oxide/h-BN Metal Insulator Semiconductor Diodes by Nanosecond Laser Irradiation. Nanomaterials 2022, 12, 2718. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Kharton, V.; Viskup, A.; Kovalevsky, A.; Jurado, J.; Naumovich, E.; Vecher, A.; Frade, J. Oxygen ionic conductivity of Ti-containing strontium ferrite. Solid State Ion. 2000, 133, 57–65. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Schubart, M.; Mitchell, G.; Kottke, T.; Gade, L.; Mcpartlin, M. Ionic cleavage of Ti–Co and Zr–Co bonds: the role of the nucleophilicity of the late transition metal in the reactive behaviour of early–late heterobimetallics. Chem. Commun. 1999, 3, 233–234. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Bresciani, L.; Stülp, S. Photoelectrocatalytic conversion of biomethane and biogas to hydrogen over a nanostructured Ti/TiO2 semiconductor. Int. J. Energy Res 2022, 27, 281. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

|

Disclaimer/Publisher’s Note: The statements, opinions and data contained in all publications are solely those of the individual author(s) and contributor(s) and not of MDPI and/or the editor(s). MDPI and/or the editor(s) disclaim responsibility for any injury to people or property resulting from any ideas, methods, instructions or products referred to in the content. |

© 2025 by the authors. Licensee MDPI, Basel, Switzerland. This article is an open access article distributed under the terms and conditions of the Creative Commons Attribution (CC BY) license (http://creativecommons.org/licenses/by/4.0/).