1. Introduction

Understanding the statistical mechanics of structured particles with arbitrary size and shape in external fields remains a major theoretical challenge, largely due to the complex entropic contributions arising from particle configurations at finite densities. Even for simplified models, such as linear particles with hard-core interactions on regular lattices, the problem is analytically intractable. This difficulty stems from spatial correlations among allowed particle configurations, which complicate the calculation of thermodynamic potentials. These correlations underlie various emergent collective behaviors, including nematic ordering in systems of linear

k-mers [

1], and entropy-driven competition in multicomponent mixtures. Exact solutions have been found only in a few special cases, such as dimers on square lattices [

2] and hexagons on regular lattices [

3].

In continuum systems, this problem has been extensively studied. In three-dimensional colloidal suspensions, Onsager famously demonstrated that elongated molecules undergo a phase transition from an isotropic to a nematic phase [

1]. In two dimensions, although continuous rotational symmetry cannot be spontaneously broken, a Kosterlitz–Thouless transition occurs, characterized by a power-law decay in orientational correlations [

4,

5].

In contrast, the case of hard-core particles on lattices is less well understood. Early work by Flory [

6] and Huggins [

7] initiated the study of rigid rods, or

k-mers, modeled as linear arrangements of

k identical units occupying contiguous lattice sites. These rods interact solely through hard-core exclusion, meaning that no site may be occupied by more than one unit.

The Flory–Huggins (

) theory, developed independently by Flory [

6] and Huggins [

7], generalizes the theory of binary liquid mixtures or dilute polymer solutions on lattices. In the lattice–gas framework, the adsorption of

k-mers on homogeneous surfaces is formally analogous to polymer–solvent binary solutions.

Extensive efforts have been made to assess

theory against experimental results, the theory being completely satisfactory in a qualitative, or semi-quantitative way. There is no doubt that this simple theory contains the essential features which distinguish high polymer solutions from ordinary solutions of small molecules. Modified forms of the

approximation have been also proposed. A comprehensive discussion on this subject is included in the book by Des Cloizeaux and Jannink [

8].

The

statistics, given for the packing of molecules of arbitrary shape but isotropic distribution, provides a natural foundation onto which the effect of the orientation of the ad-molecules can be added. Following this line of thought, DiMarzio [

9] developed an approximate method of counting the number of ways,

, to pack together linear polymer molecules of arbitrary shape and of arbitrary orientations. Accordingly,

was evaluated as a function of the number of molecules in each permitted direction. These permitted directions can be continuous so that

is derived as a function of the continuous function

which gives the density of rods lying in the solid angle

, or the permitted directions can be discrete so that

is the the number of ways to pack molecules onto a lattice. Based on the detailed knowledge of the orientations of the molecules, the various types (nematic, smetic, and cholestic) of liquid crystals were argued for and the reasons for their existence were ascertained. In the case of allowing only those orientations for which the molecules fit exactly onto the lattice is that for the case of an isotropic distribution the value of

reduces to the earlier result by Guggenheim [

10], now known as the Guggenheim–DiMarzio (

) approximation.

In the 2000s, two novel approaches were proposed for describing multisite adsorption. The first, developed by Ramirez-Pastor et al. [

11], introduced the Extension Ansatz (

) model for linear adsorbates on homogeneous surfaces, based on exact one-dimensional thermodynamic expressions and their generalization to higher dimensions. The second, the Fractional Statistical Theory of Adsorption (

) [

12,

13], incorporates the internal configuration of the adsorbed molecule as a model parameter.

generalizes Haldane’s fractional exclusion statistics [

14,

15], originally developed for quantum systems, to describe classical polyatomic adsorption at gas–solid interfaces.

Comparisons with simulation data [

11] have shown that the

approximation agrees well at low surface coverage, while the

model performs better at high coverage. These insights led to the development of the Semiempirical (

) Model for Polyatomic Adsorption [

11,

16], a hybrid model combining exact 1D results with

approximations, weighted appropriately.

More recently, the Multiple Exclusion (

) statistics framework was introduced to describe classical systems in which particles access spatially correlated states [

17,

18].

statistics accounts for situations in which multiple particles simultaneously exclude access to a common state, an intrinsic feature of non-monomeric particles on a lattice. The uncorrelated limit of

statistics recovers both the Haldane-Wu and

formalisms. This approach was further extended in Ref. [

19] to mixtures of particles with arbitrary shapes and sizes, allowing for analytical expressions of thermodynamic quantities in terms of coverage and species densities.

Despite the number of studies dealing with the adsorption of polyatomics on discrete lattices, there are many aspects which are still outstanding. While the problem can be easily and precisely defined, exact solutions for adsorbed correlated particles, such as

k-mers, have historically proved elusive, with results being limited to one-dimensional substrates [

20] and a few shapes in dimensions greater than one. The classic example of such a model is the lattice-gas of dimers (

) [

2,

21,

22,

23,

24,

25,

26,

27,

28]. A review on the entropy of fully packed dimers on planar lattices may be found in Ref. [

29].

The inherent complexity of the

k-mer problem is further increased when attempting to obtain approximate solutions for the thermodynamic functions of systems that, in addition to allowing multiple site occupancy, also involve lateral interactions among adsorbed molecules and/or surface heterogeneity. In this context, simple solvable models of adsorption on homogeneous surfaces serve as valuable foundations for developing alternative approaches to more complex cases involving interacting adsorbates [

30,

31] and heterogeneous surfaces [

32,

33,

34,

35,

36,

37].

In this work, we present a comprehensive overview of foundational and recent theoretical developments in the modeling of structured particle adsorption on regular lattices (commonly referred to as multisite occupancy adsorption). We focus on how particle geometry and size affect the configurational entropy of the adsorbed layer, an aspect that has rarely been systematically treated in thermodynamic models. Understanding entropic effects in polyatomic systems is particularly relevant for applications such as alkane and hydrocarbon adsorption, which are key to petrochemical separation technologies.

The paper is structured as follows:

Section 2 examines the thermodynamics of one-dimensional lattice gases composed of interacting and non-interacting linear particles, covering both single-species and mixture adsorption, including monolayer and multilayer regimes.

Section 3 presents theoretical approximations for non-interacting polyatomic species in two dimensions, including the

and

models, the

extension of one-dimensional results, the

framework based on fractional statistics, the Occupation Balance (

) approximation, and the

model. Adsorption of single and multicomponent species is discussed in both monolayer and multilayer contexts.

Section 4 explores two-dimensional lattice gases of interacting structured species via mean-field and quasi-chemical approaches. Intermolecular interactions give rise to possible phase transitions.

Section 5 introduces the

statistics framework for classical lattice gases of arbitrarily shaped particles, generalizing the formalism of multiple exclusion statistics presented in Ref. [

18].

Section 6 extends

statistics to multicomponent systems, analytically describing the exclusion spectra in terms of lattice coverage and species densities. This appears as a suitable framework to address complex lattice gases mixtures where spatial state correlations are significant to understand their phase behavior.

Section 7 discusses applications of the main theoretical models developed in this review, comparing model predictions with Monte Carlo simulations and experimental data.

Section 8 focuses on computational methods. The statistics of polyatomics is also a very demanding problem from a computational point of view. Whereas for monomer particles (

) the thermal equilibrium is quickly reached using standard adsorption–desorption MC algorithms, the relaxation time for large particles increases very quickly as the density increases. Consequently, MC simulations are very time consuming at high density and produce artefacts related to non-accurate equilibrium states. In order to cope with these difficulties, efficient MC simulations based on cluster moves were developed in the literature. The use of these techniques has made it possible to investigate the behavior of the system at high densities. In

Section 8, the main computational algorithms of interest for the study of adsorption problems involving multiple-site occupancy are presented. Most of these algorithms have been used throughout the present work. Finally,

Section 9 presents our conclusions and future perspectives.

5. Latest Developments, Part I: Multiple Exclusion Statistics for Spatially Correlated Single Species

Recently, it has been proposed that the complex problem of interacting particles with arbitrary size and shape can be addressed using concepts from fractional statistics, extending them to classical systems of particles with spatially correlated states [

12]. This approach reframes the counting of allowed configurations in terms of exclusion principles that go beyond Pauli-type constraints, providing a new route to approximate thermodynamic functions in structured lattice gases.

We briefly revisit the foundational arguments and structure of the formalism for a single particle species in a homogeneous external field. The generalization to mixtures of species will be presented in the following section of this review (

Section 6).

5.1. Multiple Exclusion Statistics Formalism

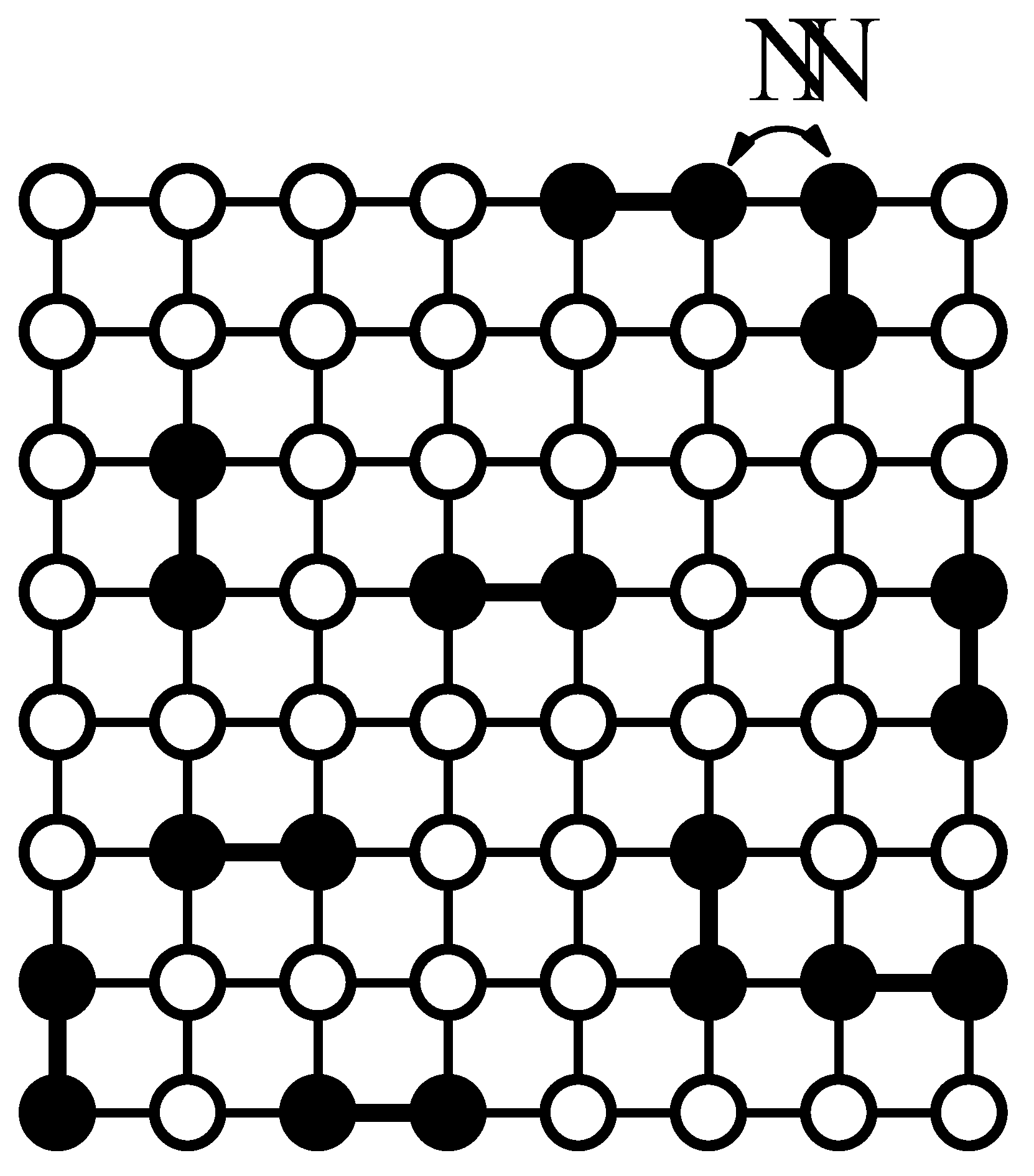

We consider the equilibrium of identical particles distributed over a set of states within a volume

V. These states are, in general, spatially correlated—meaning that the allowed equilibrium positions (i.e., the state spectrum) are distributed over space with correlation lengths smaller than the size of a particle

8. As a result, a particle occupying a particular state not only excludes that state but also prevents occupation of additional states due to the spatial extent of the particle relative to the distribution of states.

In systems where each particle excludes a constant number

g of states, this process has a classical analogy to the quantum exclusion principle, as introduced in Ref. [

14]. However, due to the spatial arrangement of states (or the lattice topology, in the case of lattice systems), multiple particles may simultaneously exclude the same state. This occurs, for example, in regular lattices with structured particles spanning more than one site. We refer to this statistical phenomenon as multiple exclusion (

) of states, which significantly influences the entropy and thermodynamic behavior of the system.

Since

is inherently configuration-dependent, we construct an approximate expression for the partition function using a state-counting ansatz that captures the configuration-dependent

while allowing for analytical and numerical thermodynamic analysis. In the special case of configuration-independent, constant statistical exclusion,

statistics reduces to the well-known fractional statistics introduced by Wu [

15]. Our objective is to develop a thermodynamic framework to describe lattice gases of structured particles through the lens of state exclusion, and to further extend it to mixtures of hard-core particles of arbitrary shape and size on a lattice.

Consider N identical particles with access to G single-particle states within volume V, at temperature T, and single-particle energy . The canonical partition function is given by , where is the Hamiltonian of the configuration, , is the total number of configurations, and the internal partition function.

Assuming particles exclude states among the

G available, which are not independent (i.e., spatially correlated), the number of configurations is approximated by

, where

is the number of states available to the

particle once the previous

have been added to the system. This expression is exact when the states are independent and the exclusion is constant, as in Ref. [

15]. For correlated states, it is approximate, since

generally depends on configuration.

A statistical ansatz has been formulated to evaluate and, in the thermodynamic limit, the density of accessible states per particle , where is the occupation number.

Applying Stirling’s approximation

, the Helmholtz free energy

leads to the intensive functions per state

and

, with

The chemical potential

takes the form

or, alternatively, as a ratio between occupied and unoccupied states:

where

,

, and

is the fraction of unoccupied states. For simplicity, we assume

.

If the system exchanges particles with a reservoir at and T, the time evolution of the occupation number is , where and are the probabilities of a state being empty or occupied, and , are the transition rates.

At equilibrium,

, which implies

Since

, Equation (

287) yields the expression

which is approximate, as long as

is not exact.

We now define the exclusion spectrum function [

17]

which gives the average number of excluded states per particle at occupation

n9.

Additionally, the exclusion density function is defined through the excluded fraction , such that . Then, measures the number of states excluded by inserting a particle at occupation n.

The normalization defines , where g is the number of states excluded per particle at saturation. Thus, corresponds to the exclusion caused by a single isolated particle, and .

From Equations (

287) and (

290), we obtain:

where

. These spectral functions provide a route to obtain detailed statistical information about the exclusion spectrum from thermodynamic observables such as the adsorption isotherm

, as will be further explored in

Section 5.7. All quantities are expressed in terms of the occupation number

n, which facilitates interpretation in this framework. They can be converted to lattice coverage

by the transformation

.

5.2. States Counting Ansatz: Density of States

The exact configuration counting for a general problem of this nature remains an open challenge in statistical mechanics and constitutes a demanding analytical task. Here, we introduce a self-consistent thermodynamic approximation, based on a new

statistics inspired by fractional statistics ideas [

14,

15], to describe classical systems of a single species with spatially correlated states—such as structured particles on regular lattices. We develop a general approximation for the density of states

that accounts for statistical correlations among states. Applications to the phase behavior of the classical problem of

k-mers on square lattices show that this

formulation predicts simulation results with remarkable accuracy. Additional results for squares and rectangles on square lattices have also been discussed [

18]. The extension to mixtures and more detailed treatment of

k-mer transitions have been recently addressed [

19] which we summarize in the next section.

All thermodynamic and exclusion functions introduced in

Section 5.1 are determined by the density of states. We now present the approximation for

.

The state counting scheme for a single species is summarized as follows. Let G be the total number of states available to a single particle within volume V. As we successively add identical particles from 1 to N, each occupies one state and excludes others. Importantly, the number of states excluded per particle changes with N, due to spatial correlations among the states—resulting in multiple exclusion () as previously discussed.

The following recursion relations define the number of available states for the

particle:

,

, ...,

, where

represents the state occupied by the particle plus

, the number of states excluded uniquely by the

particle [

17]

10.

In the thermodynamic limit

,

, and

, the exclusion

depends only on

n. Along with the recursion, we introduce a counting ansatz to evaluate

, assuming

, where

is a system-dependent parameter called the exclusion correlation parameter

11. Here,

represents the fraction of states still accessible to the

particle, and

resembles a mean-field-like approximation over single-particle states.

Thus, the recursion becomes:

In the limit with , retaining the first term of the sum yields , which describes the fraction of states (relative to total G) accessible to a particle at occupation n.

More generally,

takes the form

, where constants

,

are determined by boundary conditions:

and

at saturation. This gives

and

, with

being the state density at maximum occupation

. Hence,

For systems where the entropy per state vanishes at saturation (i.e., ), such as symmetric k-mers on a 1D lattice, one has . However, in most structured-particle systems on lattices, , and therefore .

For independent particles with uncorrelated states,

and

, and Equation (

294) reduces to

, corresponding to Haldane-Wu fractional statistics for constant state exclusion

g per particle. While Haldane’s generalization of the Pauli principle was originally introduced for quantum particles with

[

14], structured classical particles with excluded-volume interactions can behave as super-fermions with

.

To better illustrate how the

framework generalizes known statistics, from Equations (

289) and (

287), the

distribution function

can be written as

where

and

satisfies

In the limiting cases: for independent states (

,

) and

,

, so

, and Equation (

295) becomes the Fermi-Dirac distribution. For

,

,

, recovering the Bose-Einstein statistics. For constant exclusion

, with

, Equation (

296) reduces to Wu’s equation

, and Equation (

295) yields the Haldane-Wu fractional

g-statistics [

14,

15].

In general, for particles with spatially correlated states (as studied here), one finds

,

,

, and Equation (

296) must be solved for

n at a given chemical potential. In this work, we alternatively compute

as a function of

n directly using Equation (

286).

5.3. Density of States Parameters

In this section, we examine the statistical and physical interpretation of the parameters involved in the density of states function , and discuss how these parameters are practically determined through the relationship between lattice topology and particle structure (size and shape) via the thermodynamic limits of the exclusion spectrum.

In

Section 5.2, the constant

was introduced so that the density of states satisfies the boundary condition

. Physically,

represents the ratio between the number of states available to a particle at saturation and the number of states available to an isolated particle. Generally, for a phase of structured particles on a lattice at saturation, a finite number of configurations per particle is expected, so

. The saturation entropy per state

is related to

via Equations (

285) and (

294), yielding

The parameter

(or alternatively, the saturation entropy

) is the only free parameter of the

statistics needed to describe a wide class of complex lattice gases. However, in the analysis of the

k-mers problem on the square lattice (developed in subsequent sections),

is not treated as a free parameter. Instead, it is fixed for each value of

k using Equation (

297) to match the Monte Carlo values of

reported in [

90,

91].

As an example, for k-mers on a square lattice, assuming that the entropy vanishes at saturation () implies . Within this minimal approximation, the formalism predicts an isotropic-nematic (I-N) transition at intermediate coverage for . However, both the I-N and a high-density nematic-isotropic (N-I) transition arise only for , even for small positive values of . This behavior is latter discussed in the following section.

Next, we determine the exclusion correlation parameter from the lattice and particle characteristics. For a given particle-lattice system, the total number of distinguishable single-particle states G and the number of particles at saturation (i.e., the maximum number of particles that fit without overlap) are first computed. Then, gives the number of states excluded per particle at full coverage. For instance, for rod-like k-mers on a 1D lattice with M sites, , , and . On a 2D square lattice with sites, (two orientations per site), and , leading to .

Since each particle occupies one state, the occupation number (i.e., fraction of occupied states) relates to lattice coverage .

The exclusion correlation parameter

can be determined from the configurational boundary condition at infinite dilution. In this limit,

represents the number of states excluded by an isolated particle, denoted

. From the definitions of

,

,

, and

[Equations (

289)–(

294)], we find that

, which gives

This fundamental

equation relates model parameters to the number of states excluded by an isolated particle. Since

is known for a given species on a lattice, Equation (

298) can be solved to determine

. The solution has an analytical form:

where

is the principal branch of the Lambert function

12 and

. Details of the Lambert function are given in the next section.

Moreover, , so the limits of at and provide full characterization of state exclusion.

In 1D systems of ideal

k-mers, we have

,

, and

, which yield

for any

k, reproducing the exact results of Ref. [

20].

In contrast, for straight rigid

k-mers on square lattices with

and

, it follows that

, so

. The number of excluded states is

for

, while

,

for monomers (

). Here,

accounts for exclusion across the particle, and

for exclusion along it. The solution for

becomes:

with

.

Statistically,

originates from the

state counting ansatz in

Section 5.2. The exponential decay term

in

becomes

in terms of lattice coverage

. The ratio

thus defines the typical coverage at which the

term in the density of states decays. For instance, in the

k-mer model discussed next, the isotropic-nematic transition occurs around the point where

, indicating that most of the single particle states are excluded and so are most of the isotropic-phase configurations. Hence, the ratio

has a clear statistical and physical meaning.

5.4. Lambert Function

The Lambert function

, introduced in 1758 [

92], is defined by the equation

, with notable values

,

, and

as

.

The solution of Equation (

298),

yields:

with

, valid for

,

, and

. The function

denotes the principal (positive) branch. In particular,

for

. For

k-mers in 1D,

,

, which results in

.

For equations of the form

, with

, a substitution

transforms it into

, with solution

, yielding

. Specifically, for

k-mers, setting

,

, and

, we obtain:

valid for

, where

is the principal branch.

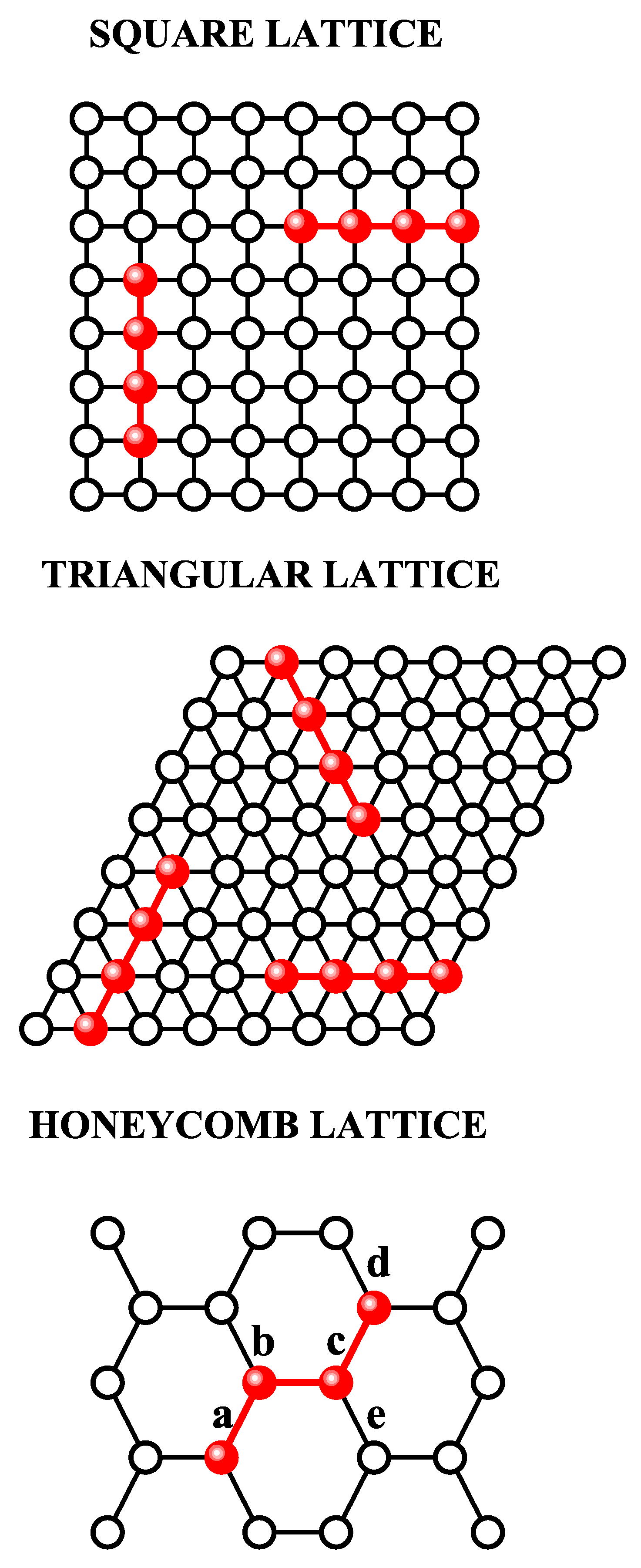

5.5. Entropy of k-Mers on Square Lattices: Orientational Phase Transitions

This section examines the phase behavior of straight rigid

k-mers adsorbed on the square lattice. This system was initially studied in Ref. [

96], where Monte Carlo simulations provided strong numerical evidence that nematic order emerges at intermediate densities for

, beyond a critical density

. Additionally, using high-density expansions, Ghosh and Dhar [

96] offered a qualitative description of a second phase transition, from a nematic to a non-nematic state, occurring at a critical density

for large

k.

Building on the seminal work of Ghosh and Dhar [

96], numerous studies have explored the phase transitions in systems of long, straight, rigid rods on two-dimensional lattices with discrete allowed orientations [

97,

98,

99,

100,

101,

102,

103,

104,

105,

106]. These investigations showed that for

, no phase transition occurs. However, for

, increasing the density leads to three distinct phases: a low-density disordered (isotropic) phase, an intermediate-density nematic phase, and a high-density disordered phase with no orientational order. The threshold value

depends on the lattice geometry:

for square [

96,

97] and triangular [

98] lattices, and

for honeycomb lattices [

99]. The intermediate-density nematic phase, characterized by a large domain of parallel

k-mers, is separated from the low-density isotropic state by a continuous phase transition at a finite critical density

. This first transition, commonly referred to as the isotropic–nematic (I–N) phase transition, belongs to the two-dimensional Ising universality class for square lattices [

97], and to the three-state Potts universality class for triangular [

97] and honeycomb [

99] lattices. In all three lattice types, the critical density associated with the I–N transition,

, follows a power-law scaling of the form

[

98]. The existence of this first transition has also been rigorously proven [

100].

While the second transition has been less understood, Ref. [

101] suggested it is continuous for

, but more recent findings [

106] argue it is first-order, showing MC evidence of phase coexistence for

.

Let us now return to the case of square lattices, which is the subject of this section. For

, the first transition occurs at

,

, and the second transition at

,

[

101,

104].

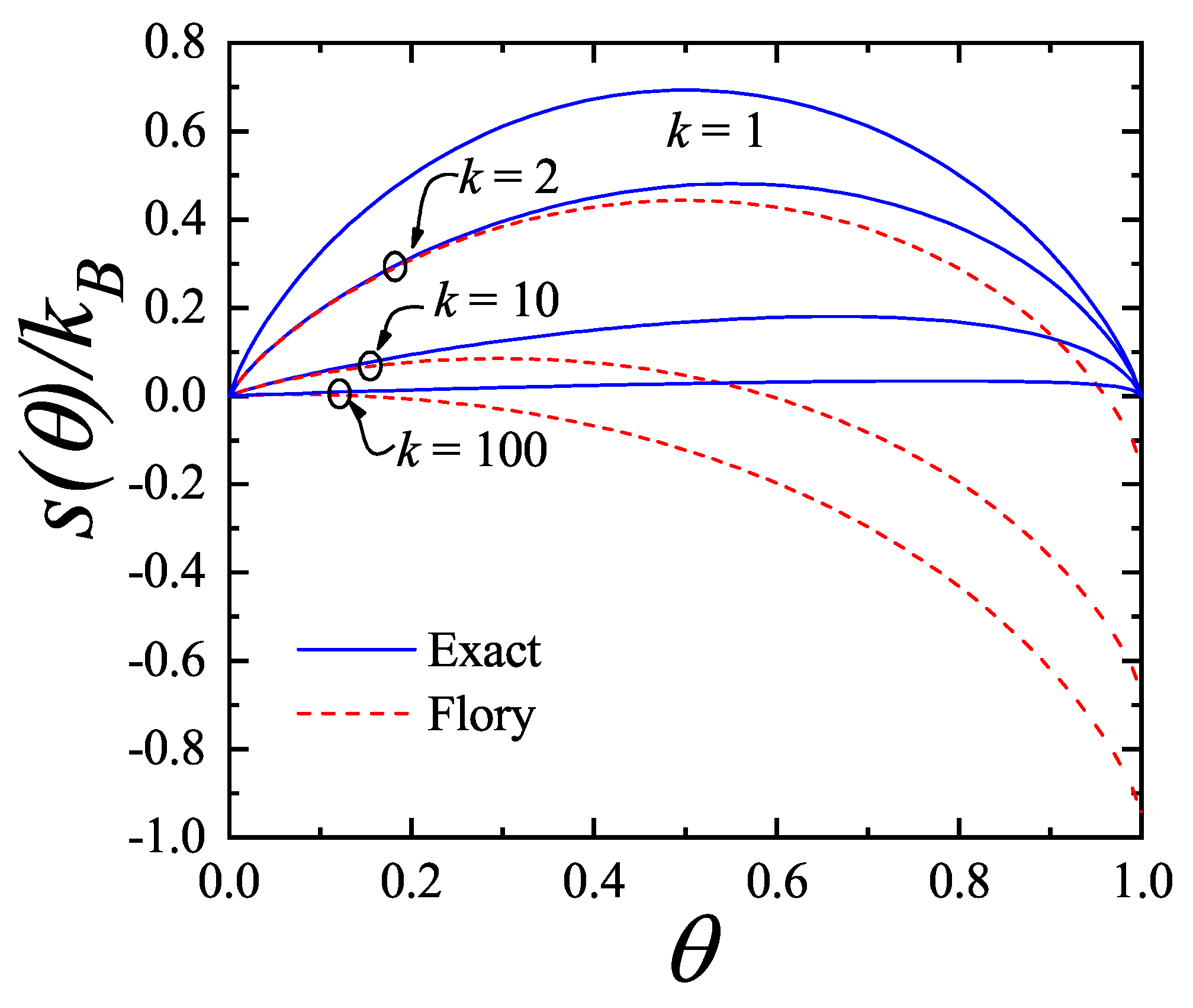

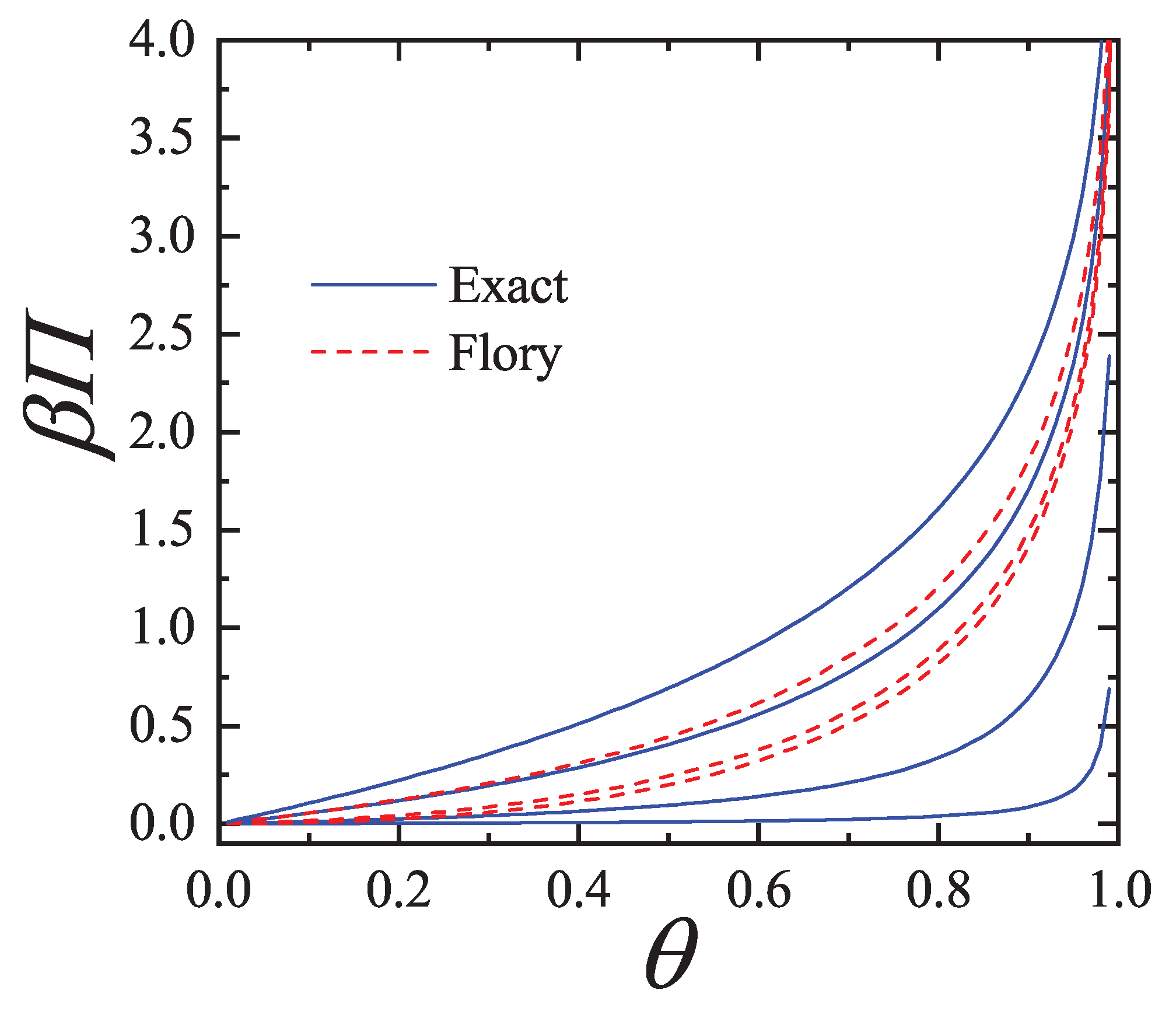

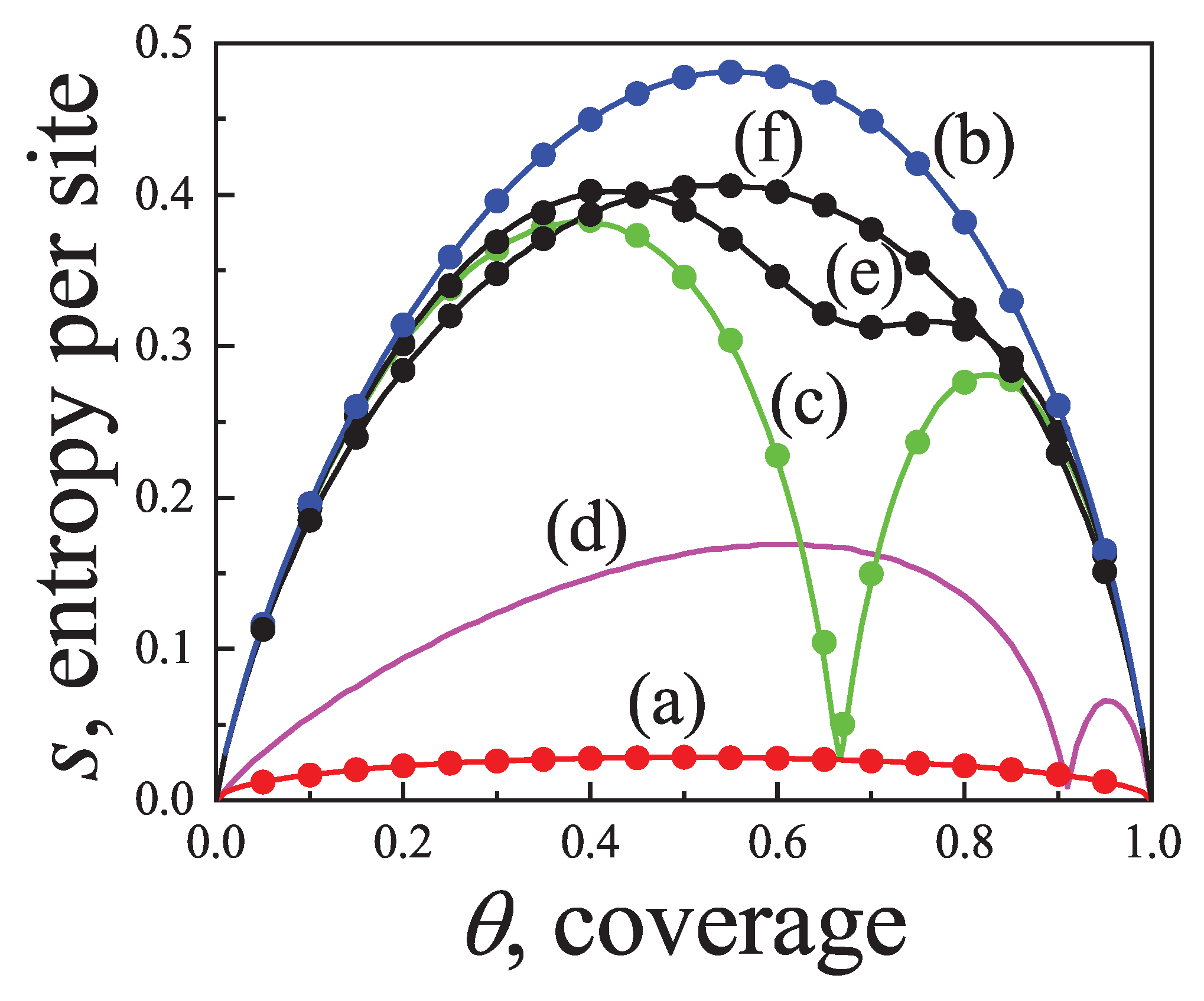

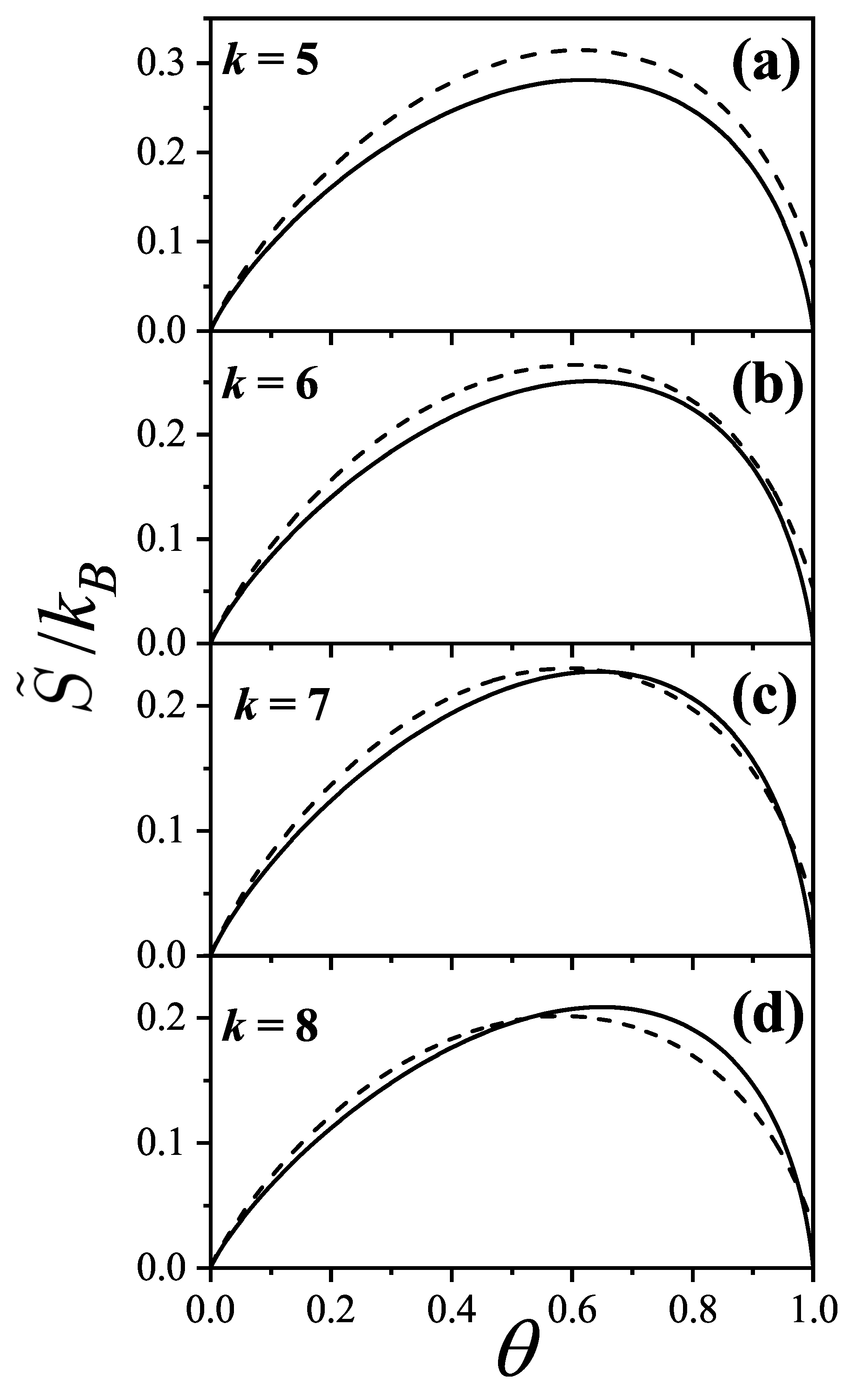

We focus on the entropy as a function of density, as derived from

statistics for both isotropic and nematic phases as

k increases. Two levels of approximation are considered: (i) a first-order approximation, where

is constant and the entropy of the isotropic phase at saturation is matched to Monte Carlo (MC) values, i.e.,

and

is fixed using Equation (

297). Additionally, the effect of assuming vanishing entropy at saturation (

,

) on the transitions and critical coverages is discussed; (ii) a second-order approximation, where

is a slowly decaying linear function of the density, as discussed in footnote

11. In both cases, the phase transitions and corresponding critical densities are predicted, with the first-order approximation yielding reasonable agreement with MC data and the second-order approximation showing very accurate results.

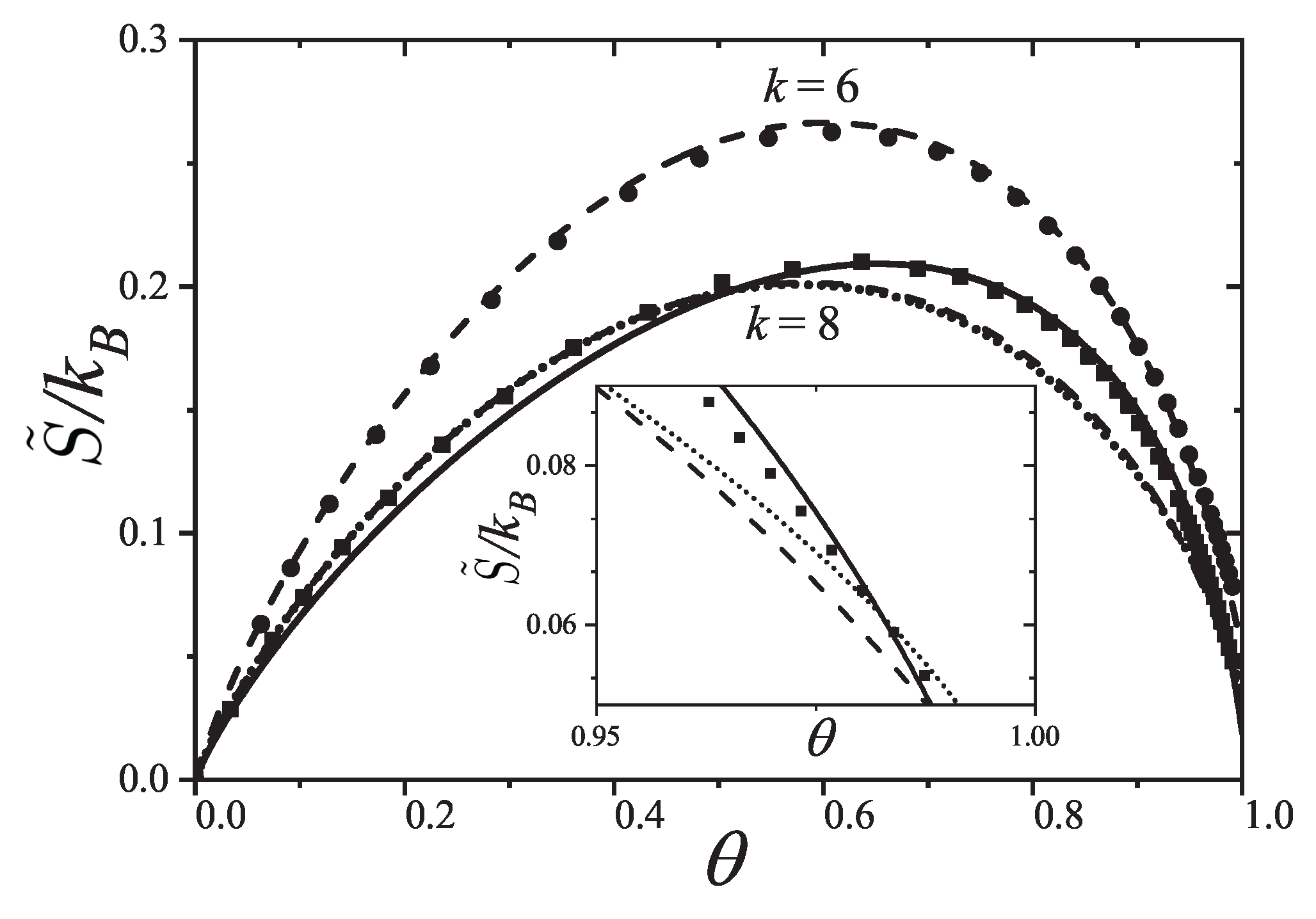

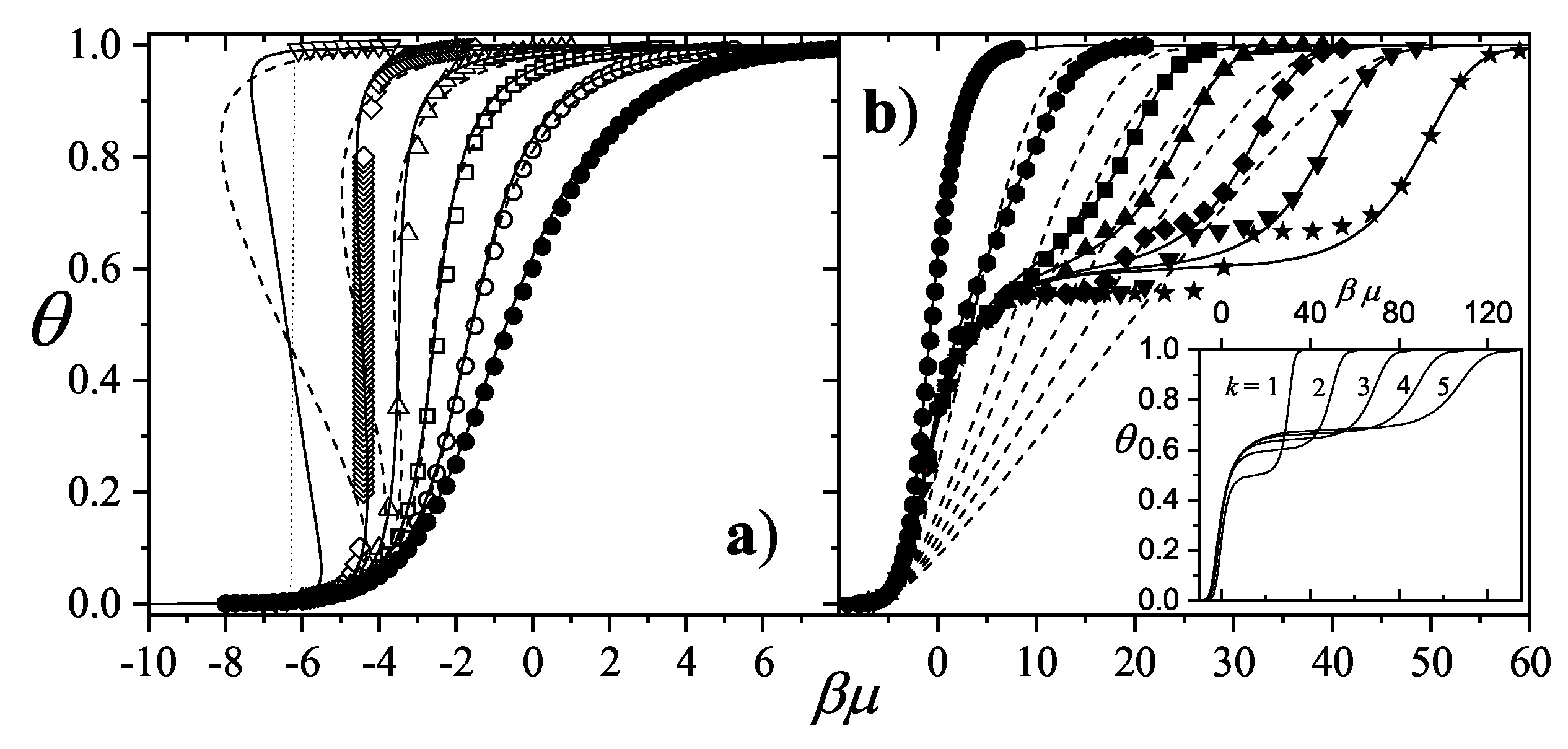

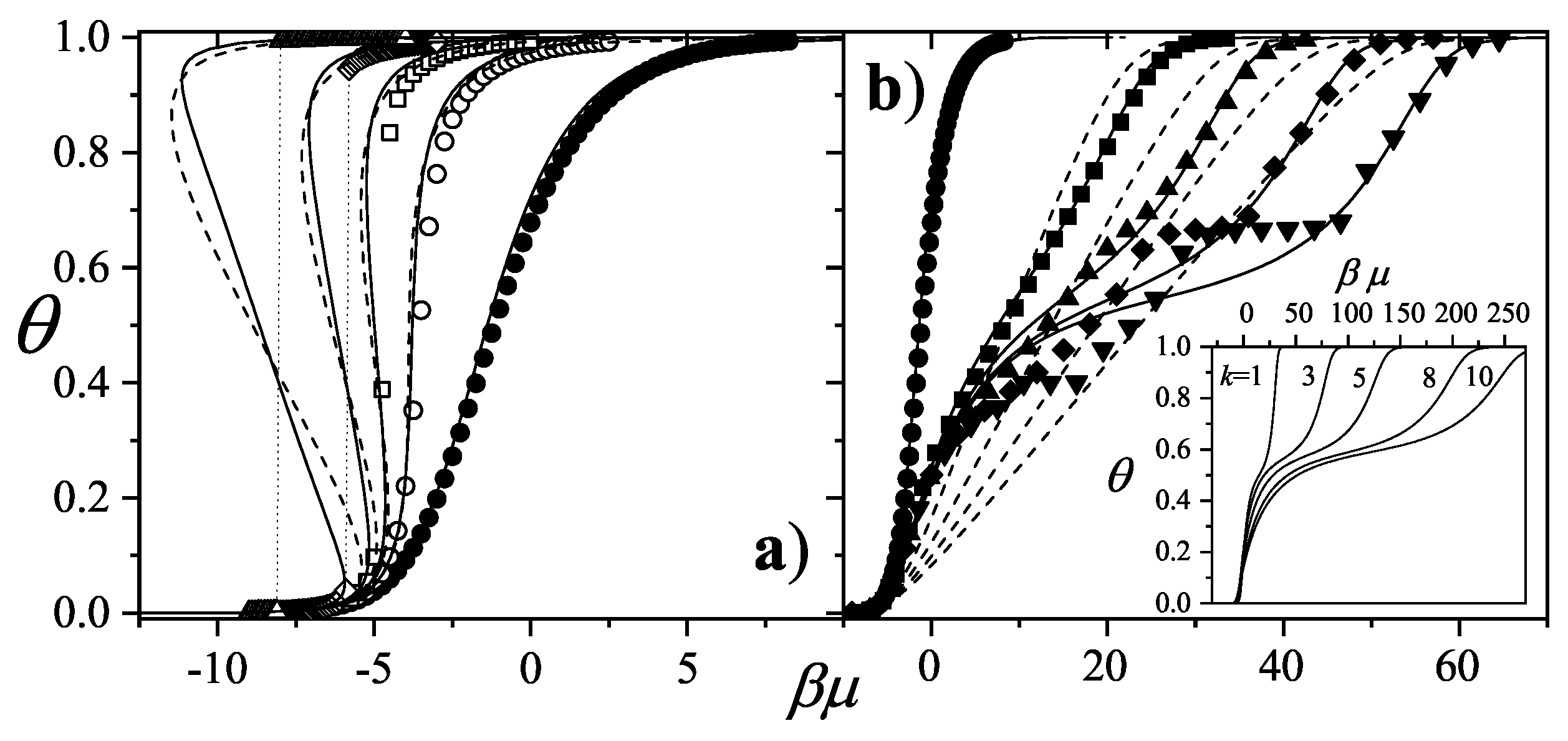

The prediction of transitions and their critical points is obtained by analytically evaluating the entropy per site as a function of

n for a fully aligned (nematic) phase,

, and for an isotropic phase,

, at the same occupation

n. The factor 2 accounts for the two possible orientations (states) per site in the isotropic phase, in contrast to one in the aligned nematic phase. The entropy per site as a function of coverage

is presented in

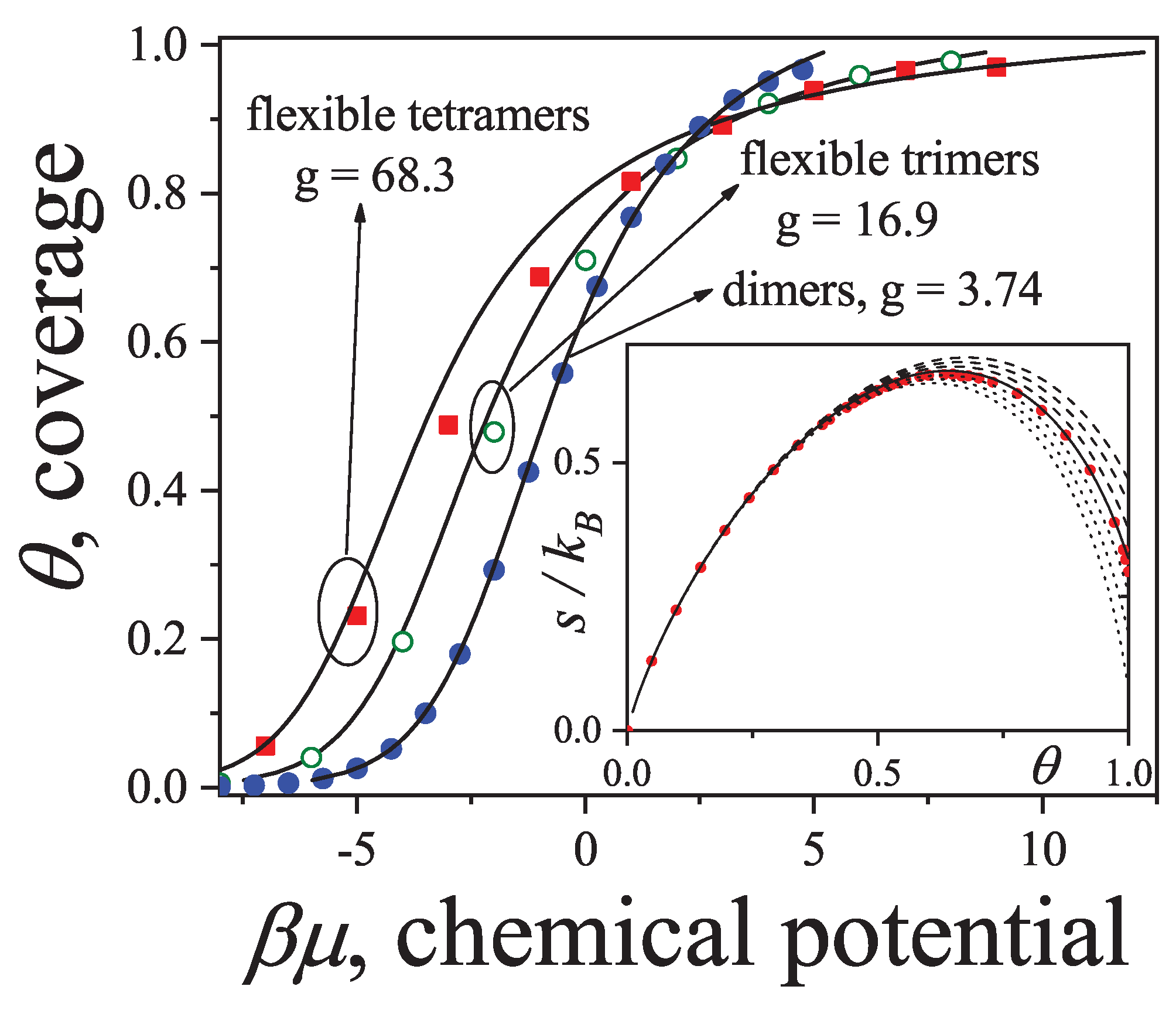

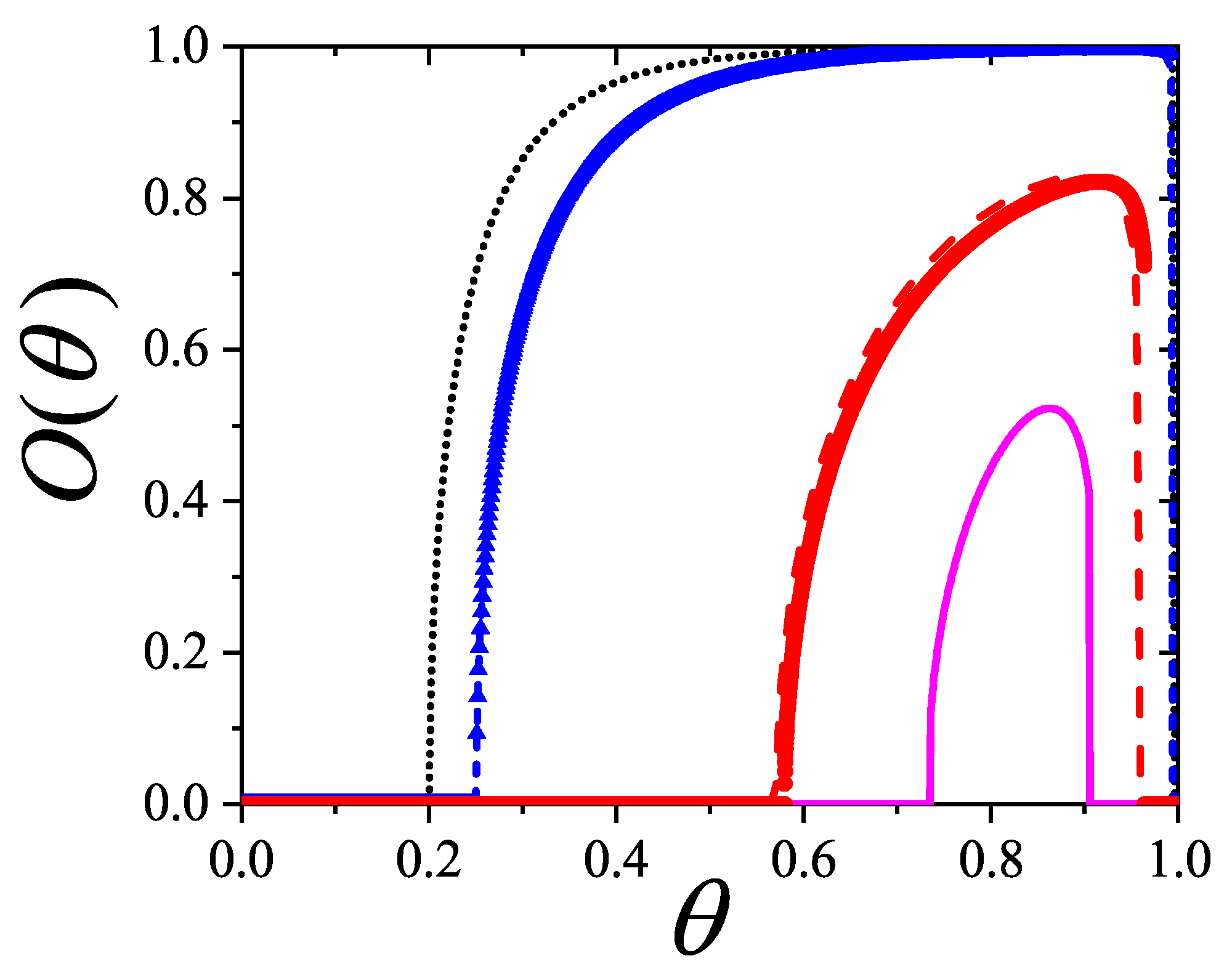

Figure 16 for

, and 8, based on Equations (

285), (

294), (

297), and (

298).

For

k-mers in a fully aligned nematic phase, the parameters are

,

,

,

, and

according to Equation (

298). For the isotropic phase, we have

,

, and

;

and

are computed using Equations (

297) and (

298). The entropy values

are taken from [

90,

91,

107] for

to 10, and for

,

and the corresponding values of

were reported in [

19]. The critical coverages

are determined by solving the equation

.

This equation yields two solutions

and

only for

; for

there is no solution other than the trivial equality at zero coverage. This behavior is shown in

Figure 16.

In particular, for

,

Figure 16(b) shows that

for

, indicating that the isotropic phase is the only stable phase. The same holds for

. Notably, for

, the smallest entropy difference occurs near

.

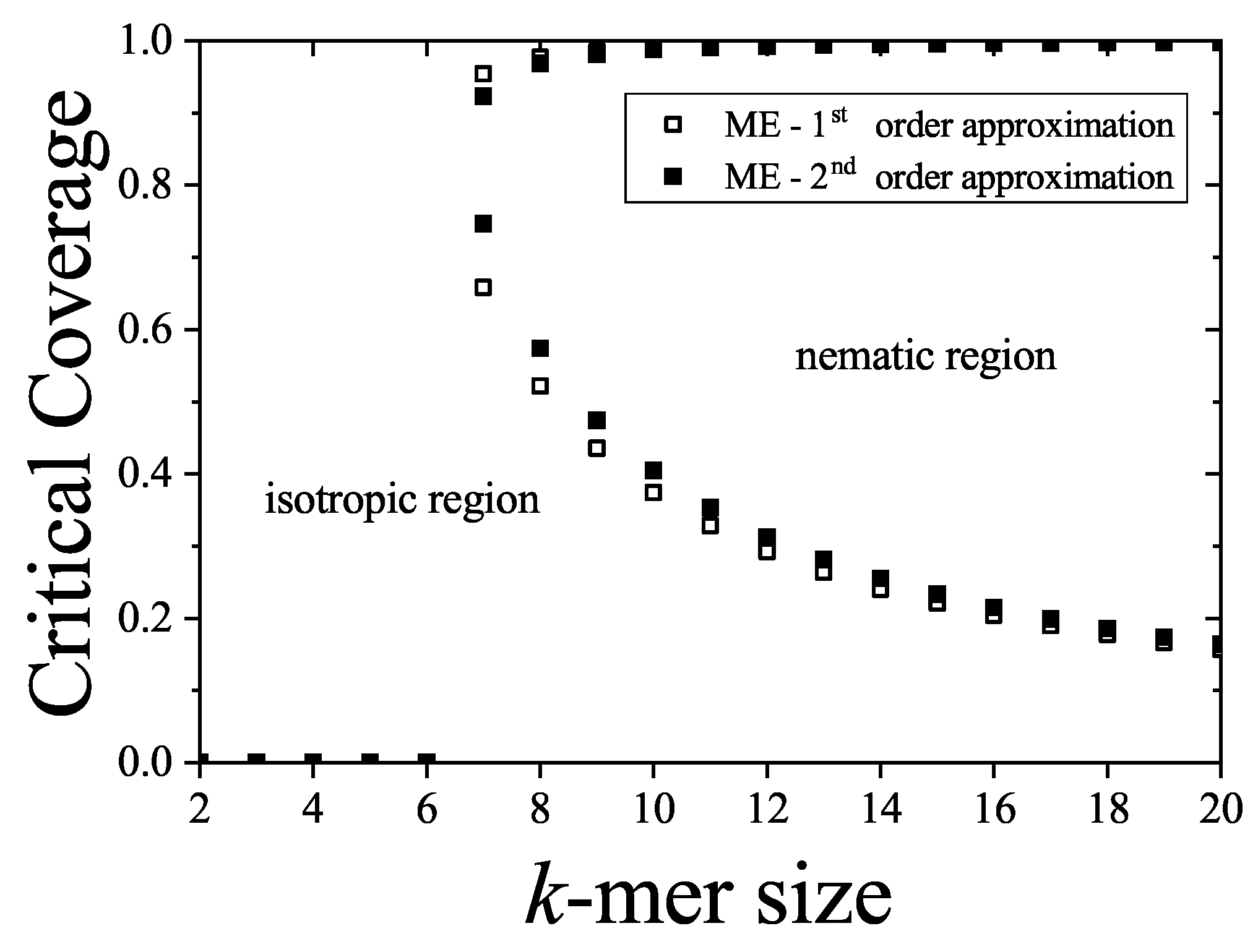

For , there are two critical coverages: and in the first-order approximation. This dual-transition pattern is found for all , consistent with the results discussed, where a mixture of cross-excluding of differently oriented species is considered. Although the nature of the transitions is not addressed here, there it finds that the I→N transition is continuous, indicating that this formalism does not matches a typical mean-field approach. For the sake of reference, in Bethe lattices with coordination q, a first-order transition occurs for depending on q [?] for this nematic transition.

In the second-order approximation,

is assumed to decay slowly with density as

, with

and

. For

, the critical coverages for

are

and

, which agree remarkably well with MC values

and

[

101].

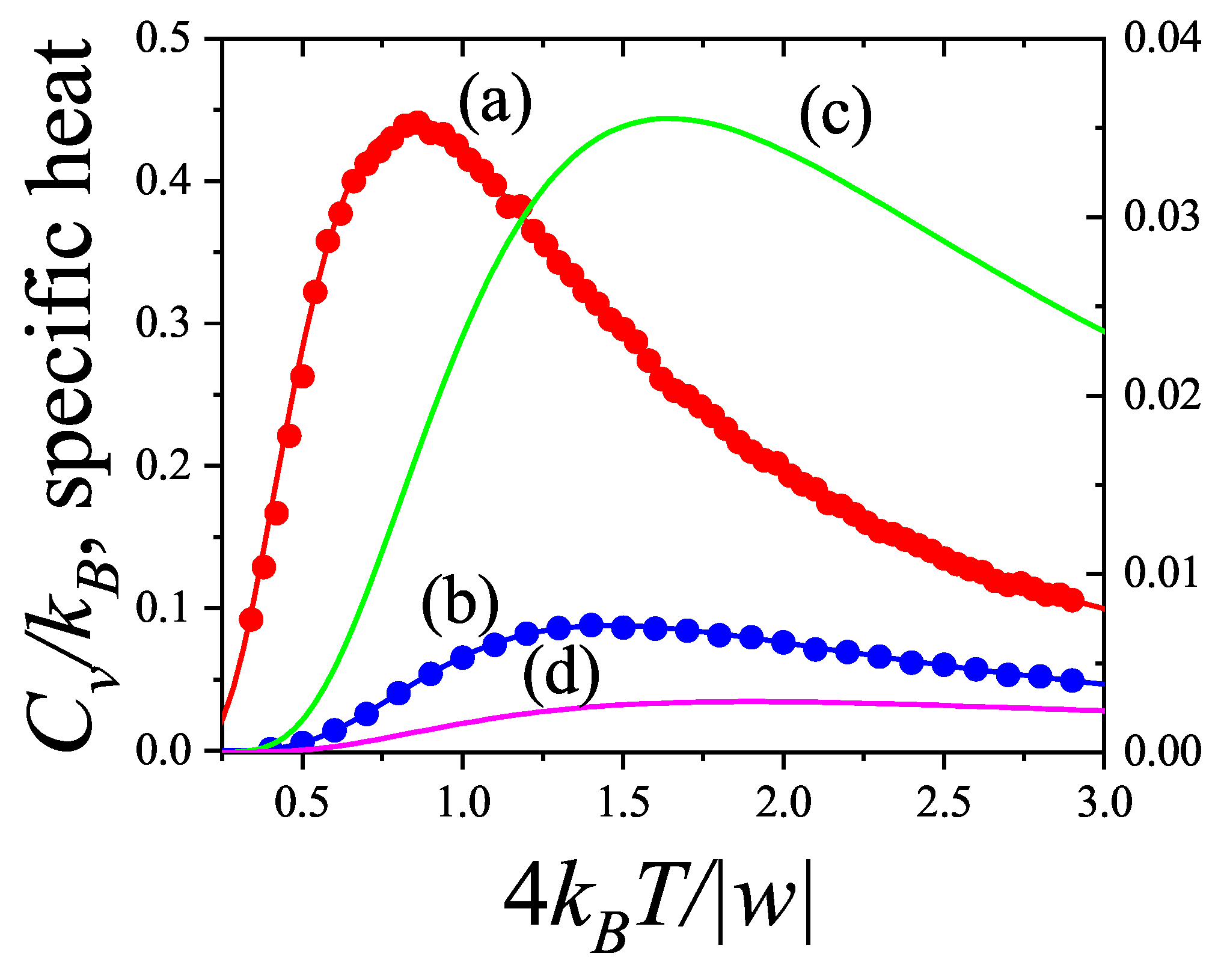

Figure 17 shows the variation of

with

k. As

,

and

.

This model predicts a sequence of phases: isotropic at low/intermediate density, nematic at higher density, and isotropic again at high coverage, in agreement with MC results for . Even assuming vanishing saturation entropy, the formalism still predicts an I-N transition for , though no N-I transition occurs.

Figure 18 compares

results with MC data for

and 8, showing good agreement in both phases, especially at intermediate coverage. Discrepancies at high density explain differences in

, since it equals the derivative of entropy with respect to

(in

units).

For

, Equation (

294) becomes exact only in 1D. In 2D systems,

due to allowed local configurations at high coverage [

90,

91]. Thus,

underestimates entropy at high density. This distinction is critical for understanding the N-I transition for

, as seen in the inset of

Figure 18.

While already captures high coverage entropy via , an empirical correction improves quantitative agreement. We define , where . The term matches the MC saturation entropy, ensures , and the exponential captures high coverage behavior.

Appropriate values of

and

reproduce MC results in both isotropic and nematic regimes. Since

, the correction is significant only very close to saturation. Saturation entropy values are taken as

for

, and

for

[

90,

91,

107].

This empirical correction also accurately reproduces the entropy of more complex particles such as trimers (straight or bent) and triangles on triangular lattices [

110].

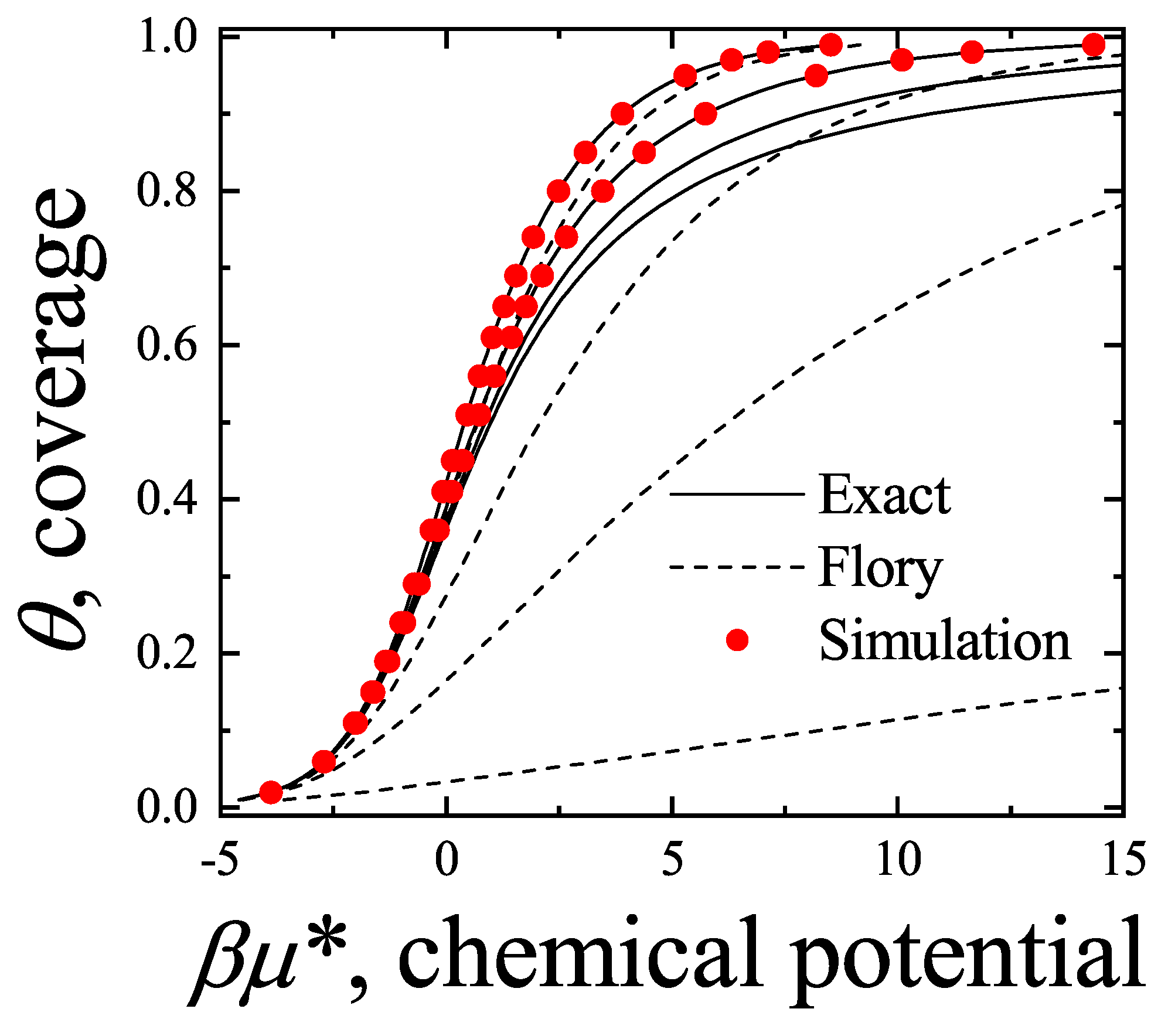

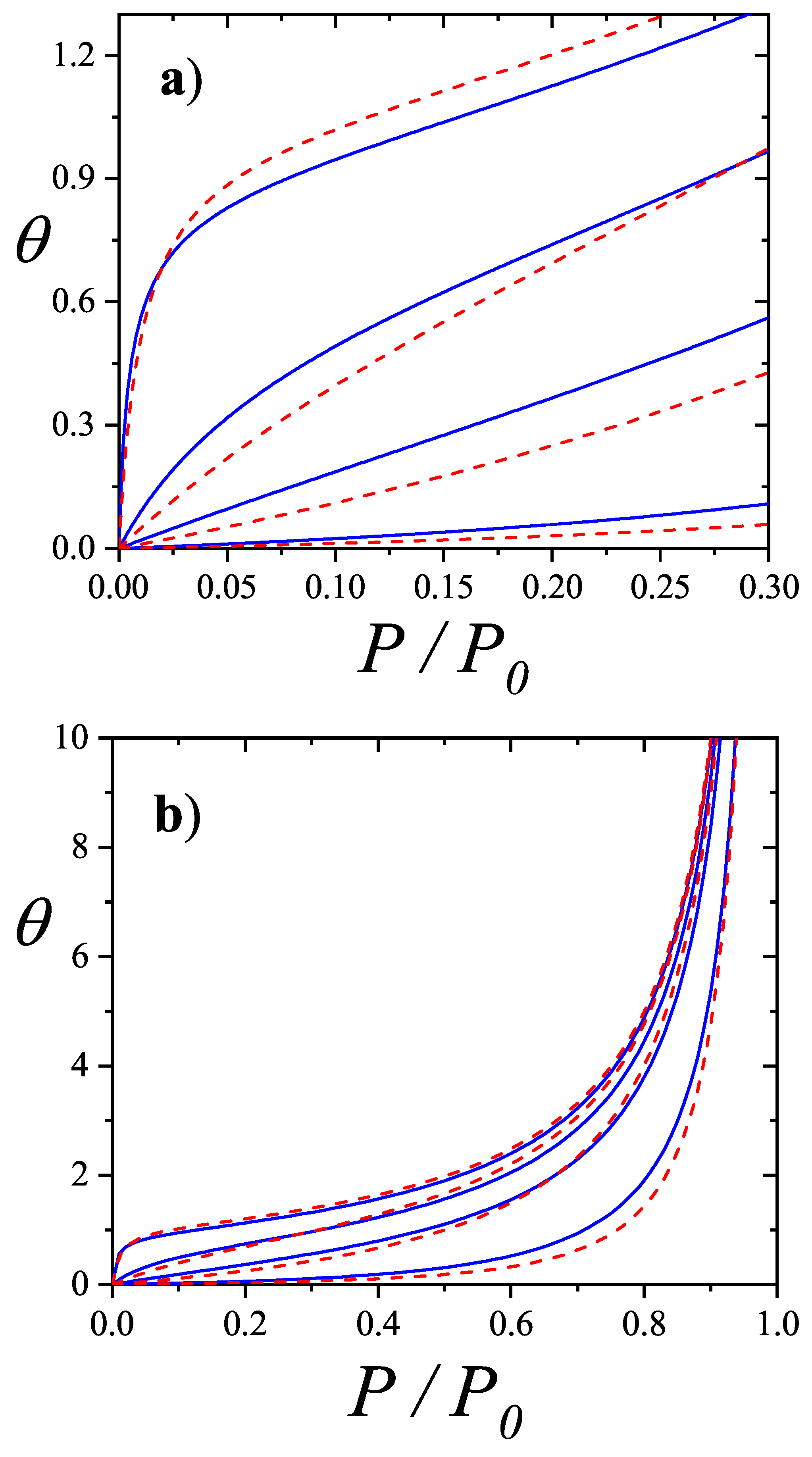

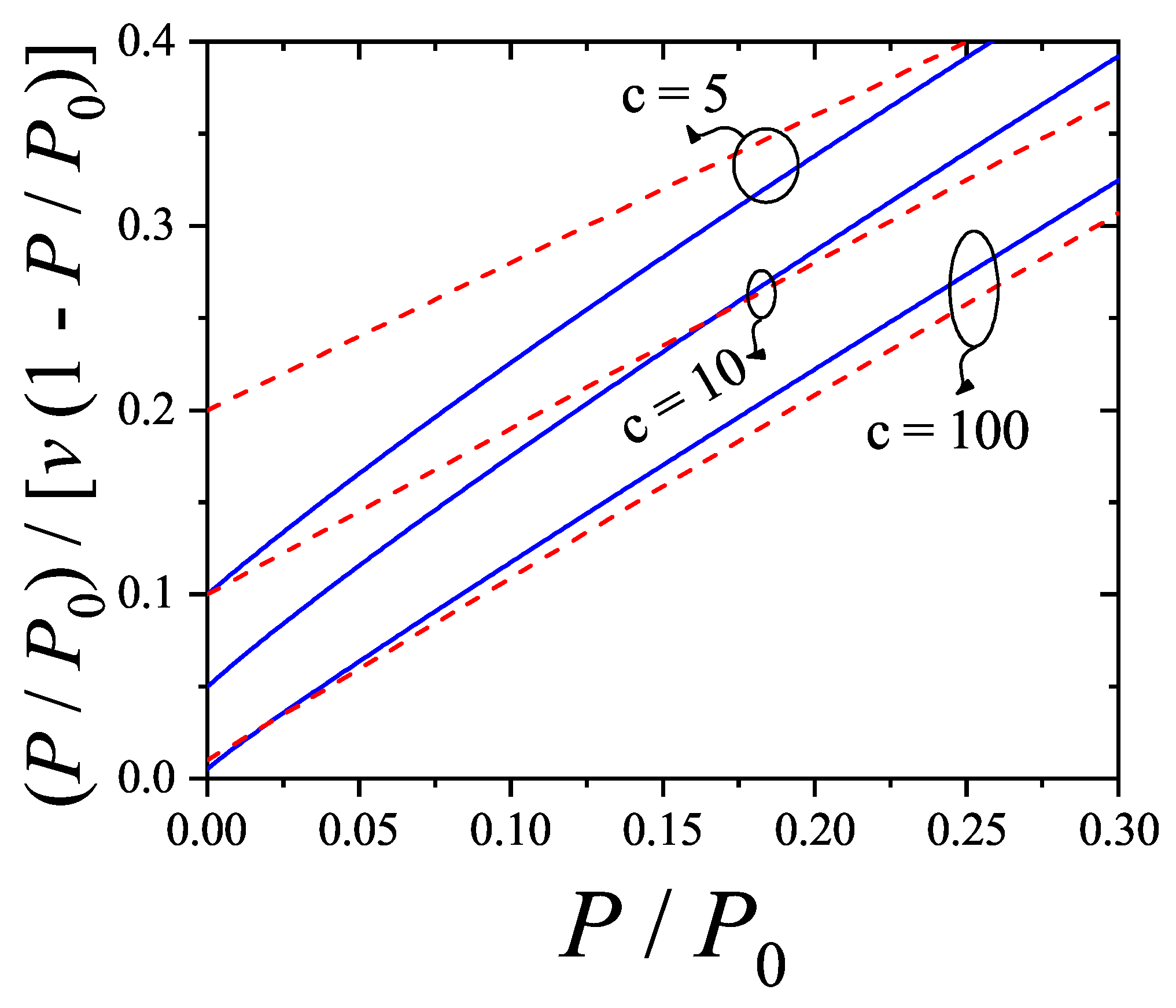

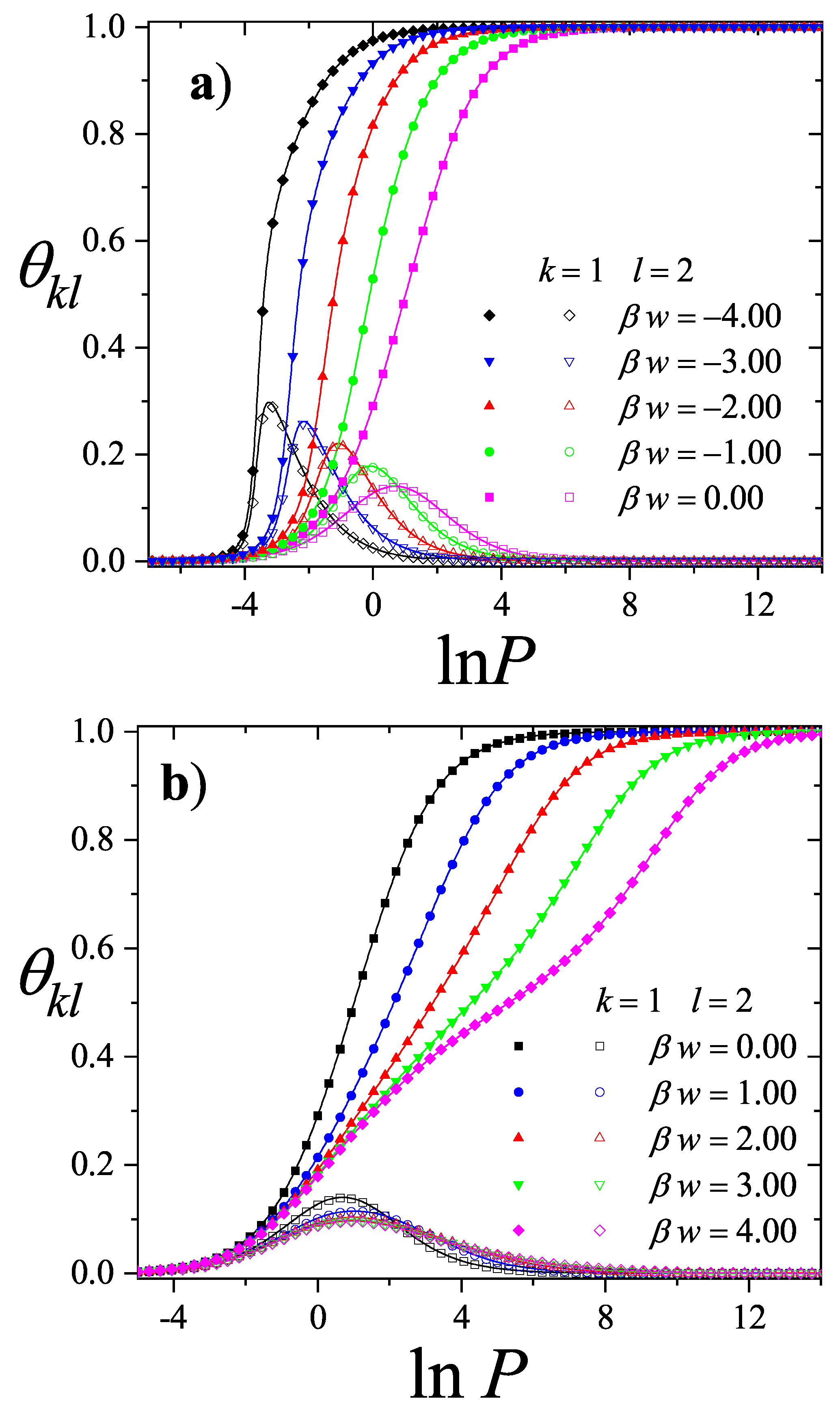

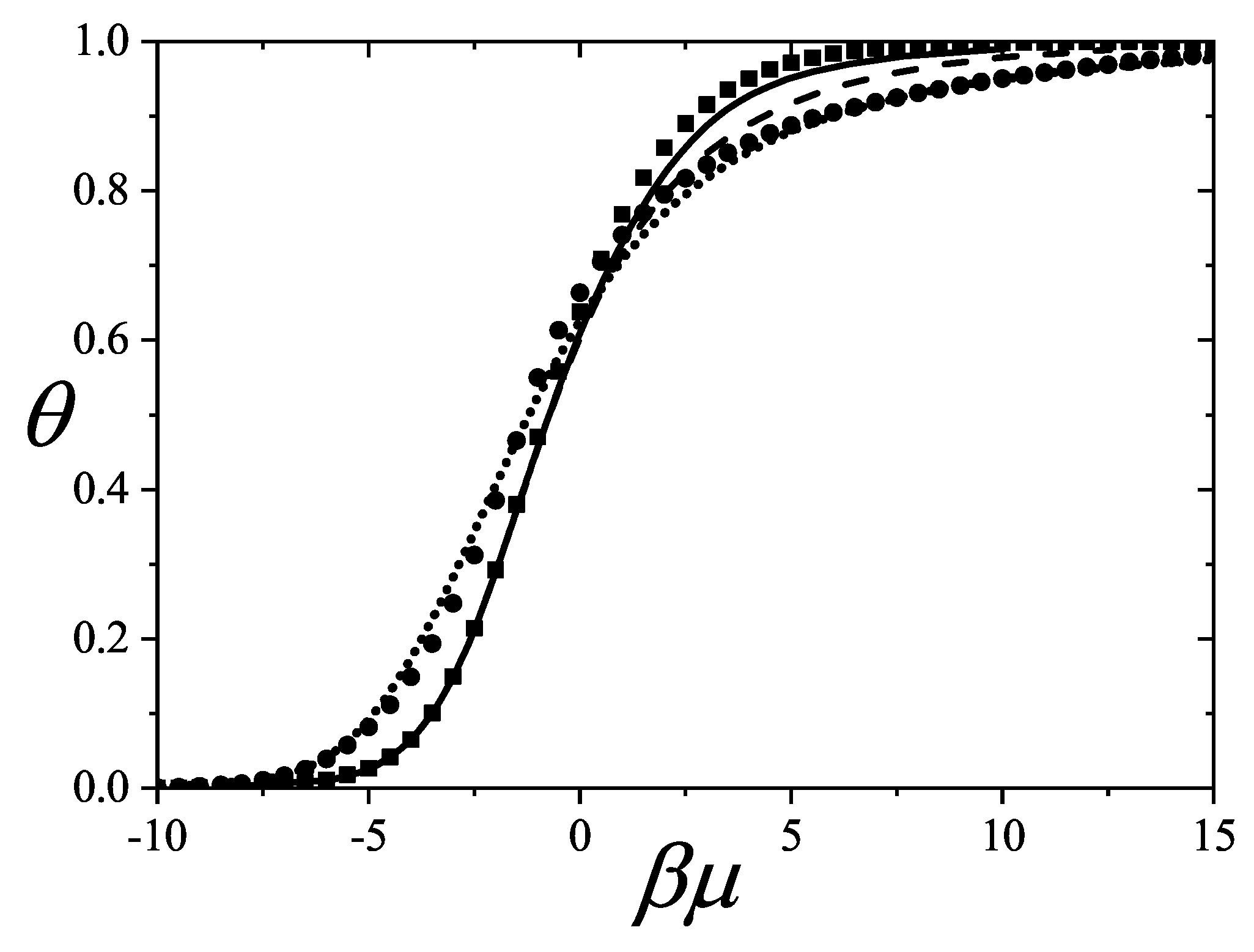

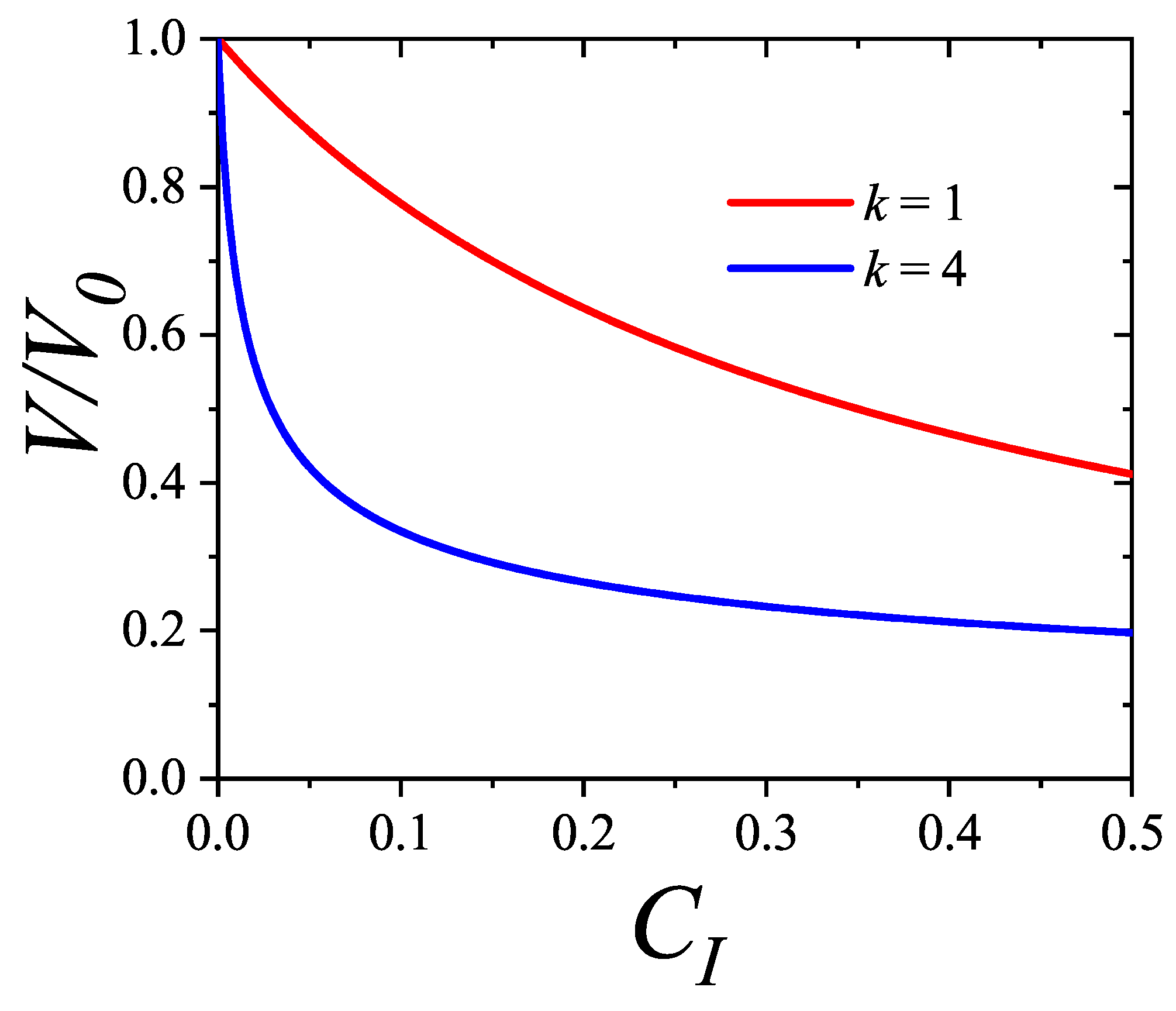

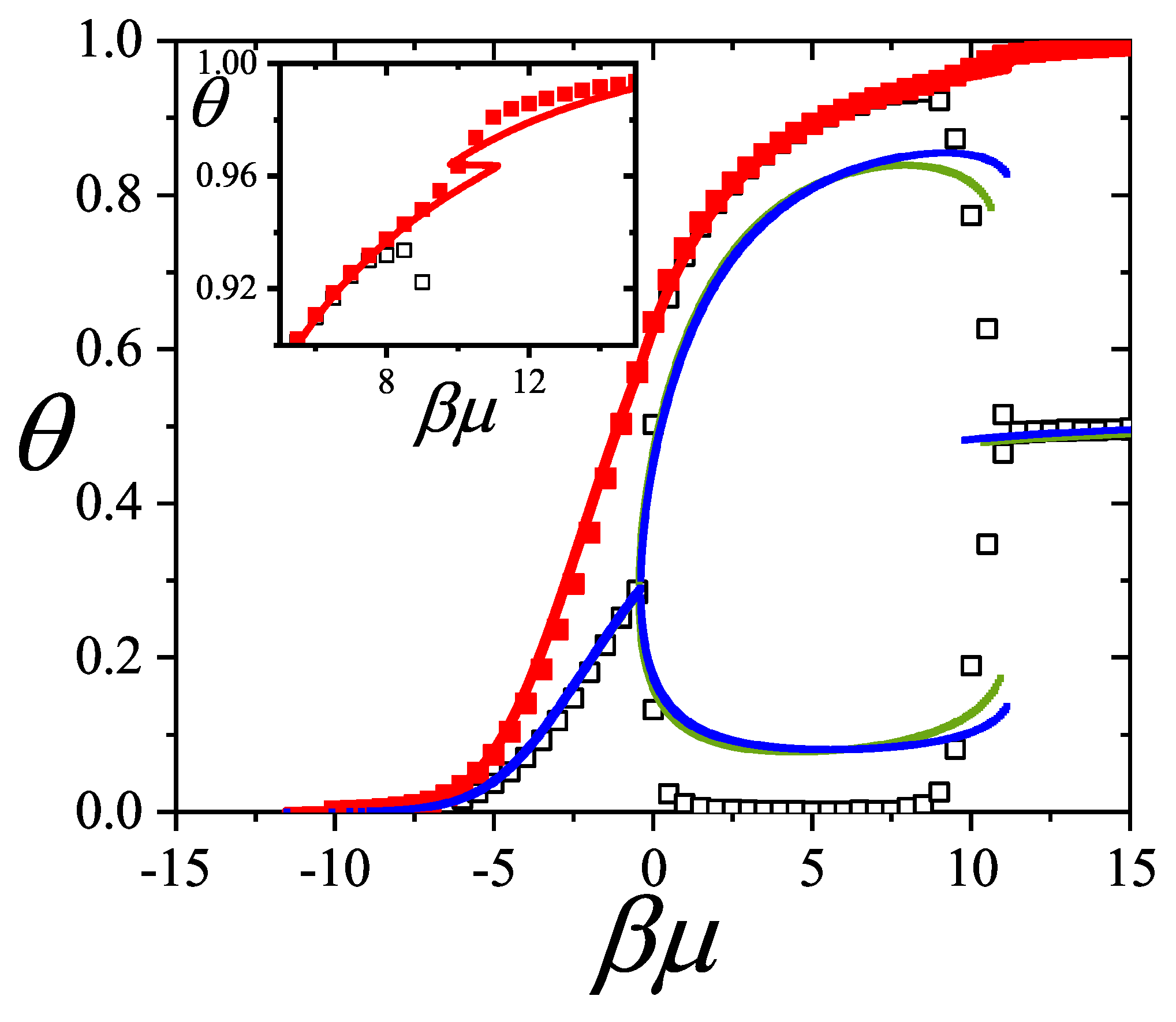

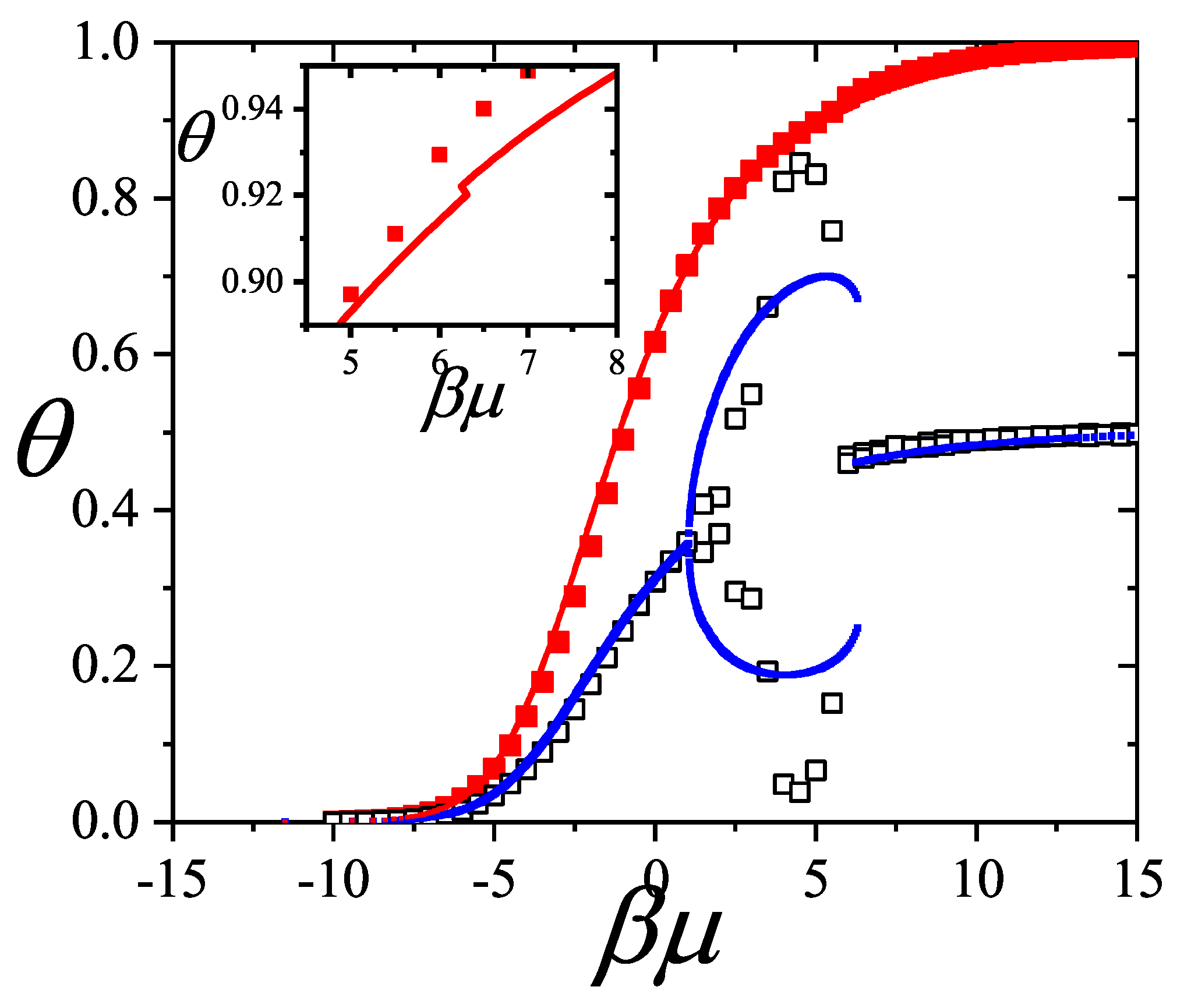

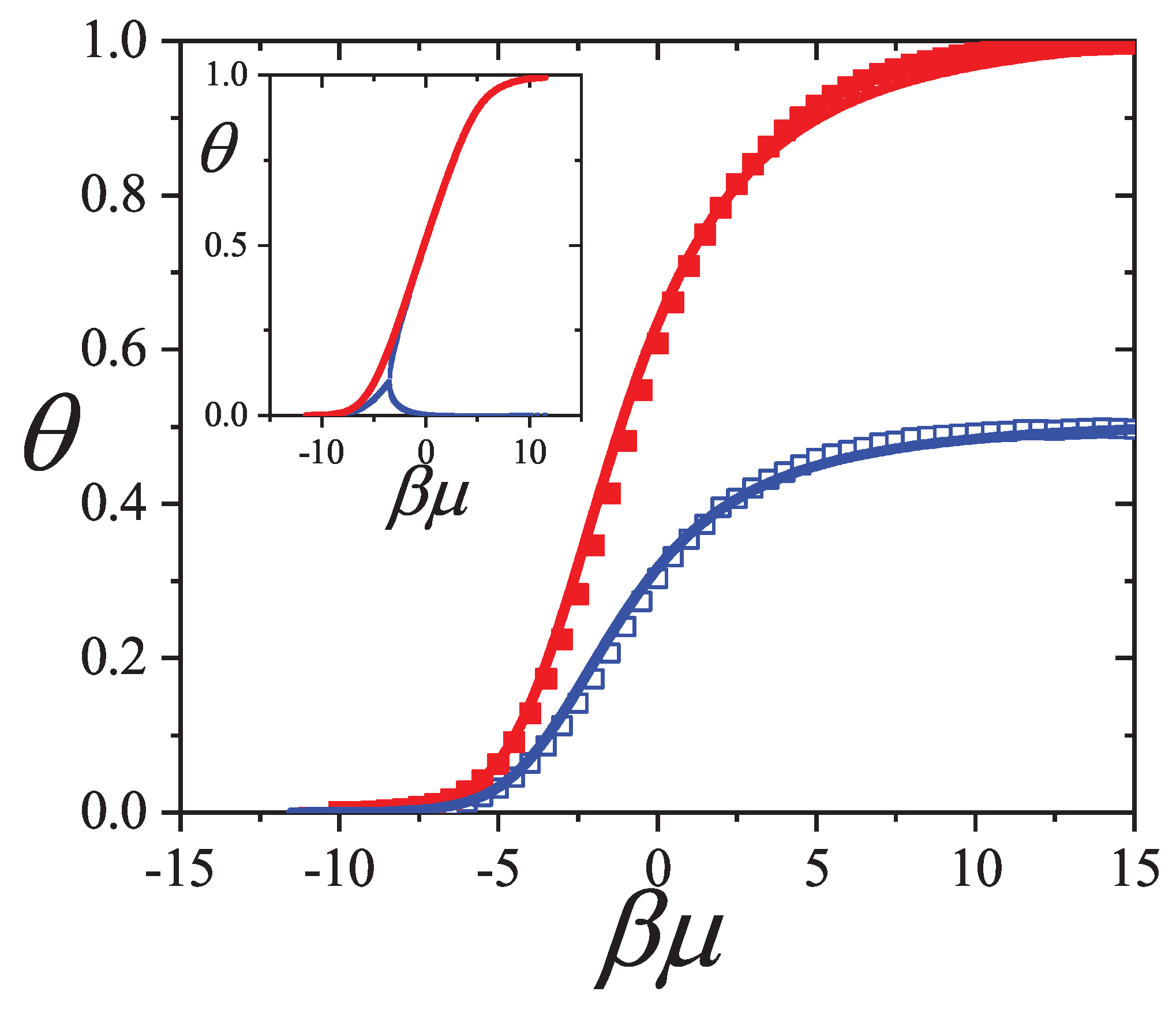

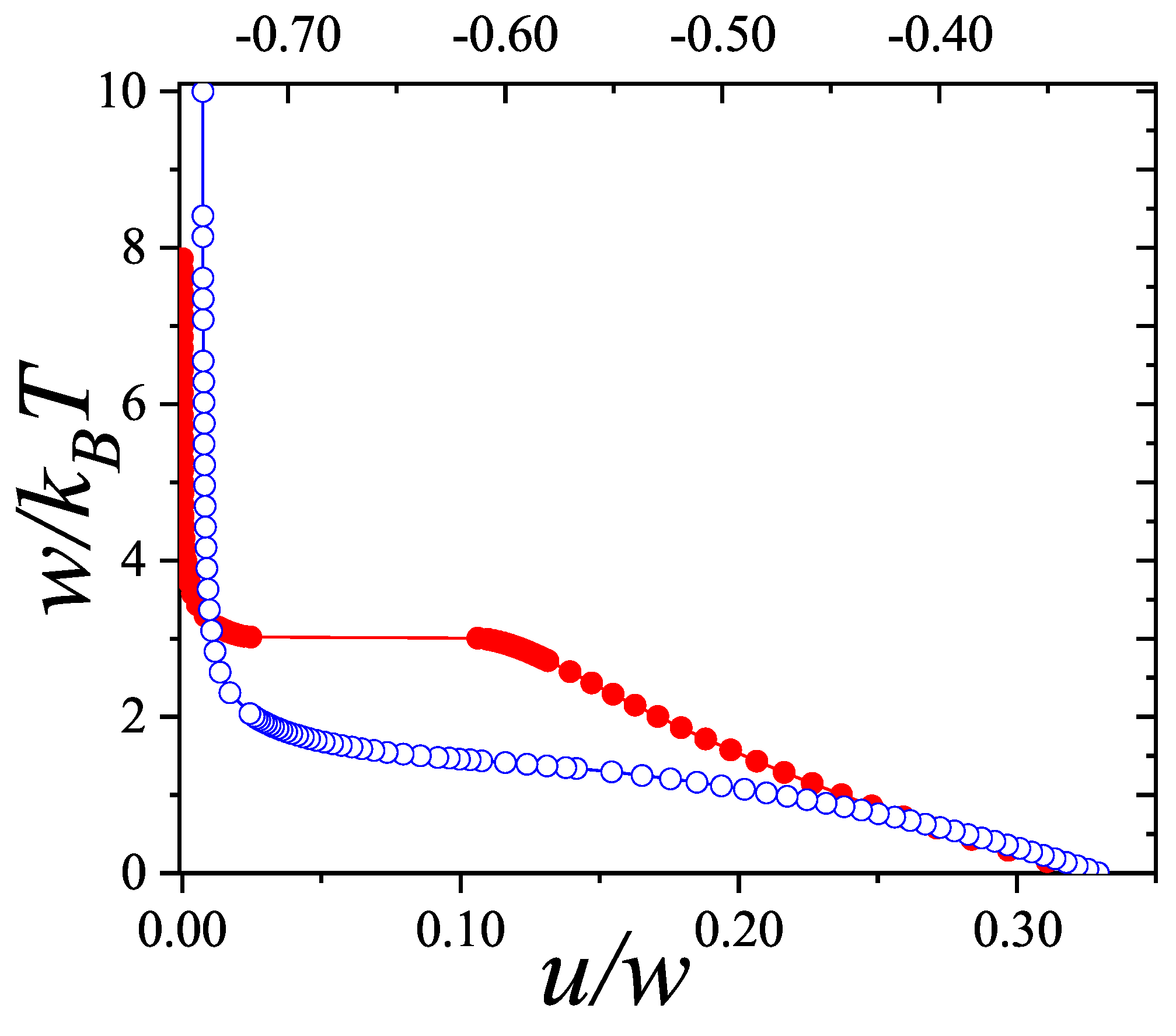

Concerning with the coverage dependence of the chemical potential from

statistics, following, we reproduce the results

for two very different k-mer’s size,

and

as illustrative examples in

Figure 19 [

18].

The variables are expressed in terms of coverage

, via the substitution

. For further details on the simulations, see Refs. [

17,

101,

111,

112].

In

Figure 19, MC data for

k-mers are compared with two analytical predictions. The dashed line corresponds to the limiting case where entropy vanishes at saturation, i.e.,

,

. When the correct value

is used, the

approximation (through Equation (

294)) provides better agreement with MC at high coverage, as seen in the solid line.

The discrepancy at high coverage for

between theory and MC is attributable to the behavior of the entropy

near

in Equation (

285). A qualitatively similar result is obtained using the empirical form

introduced in the previous section.

For

, MC simulations show that

k-mers undergo a continuous I-N transition at intermediate

[

96], consistent with predictions from the

model based on entropy comparison between nematic and isotropic phases. Despite this, Equation (

286) still gives a fair approximation for

if a value of

smaller than that from Equation (

300) is used.

This is understood as follows: nematic ordering forms compact bundles of neighboring k-mers. For a fixed particle number N, such alignment leads to more multiply excluded states and fewer total excluded states per particle, effectively reducing the parameter . A simple illustration of this can be made by comparing the number of states excluded when two k-mers are perpendicular vs. parallel and aligned.

For instance, in

Figure 19, the case

with

yields a good fit to MC data. This value of

is significantly smaller than the isotropic value

obtained from Equation (

300) reflecting bundled-like configurations of the lattice gas.

The MC simulation results presented in this section were obtained using the efficient algorithm introduced by Kundu et al. [

101,

111,

112] and described in

Section 8.5. Simulations were performed on

square lattices with periodic boundary conditions. The ratio

was set to 120, a value for which finite-size effects were found to be negligible. Equilibrium was typically reached after

MCSs, and observables were computed by averaging over

configurations.

Illustrative results for

from

statistics for squares and rectangles on square lattices were presented and compared with fast-relaxation Monte Carlo simulations in Ref. [

18]. A comprehensive study of the various phases formed by rectangles on square lattices, and other hard-core lattice gases, can be found in Refs. [

111,

113,

114,

115].

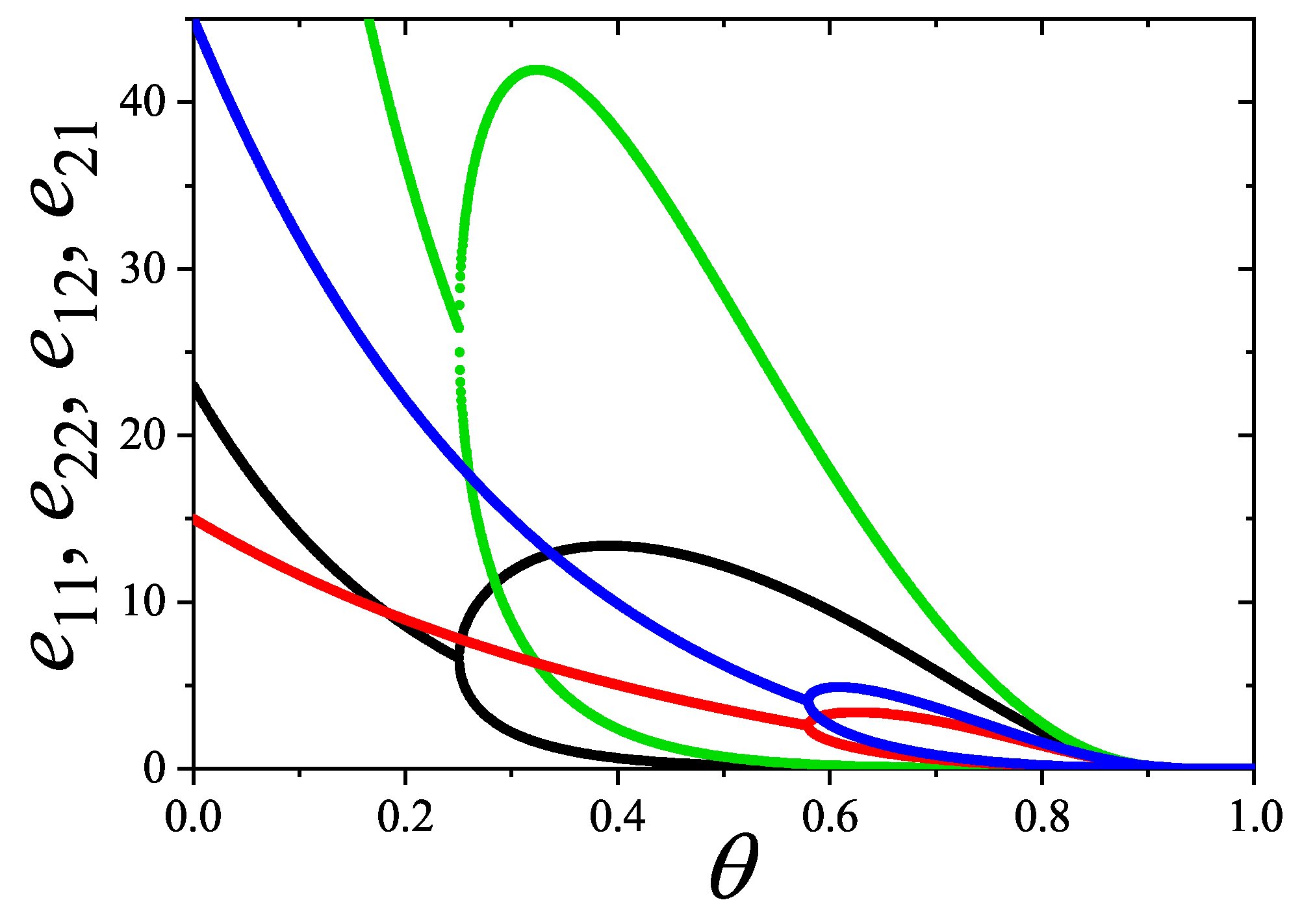

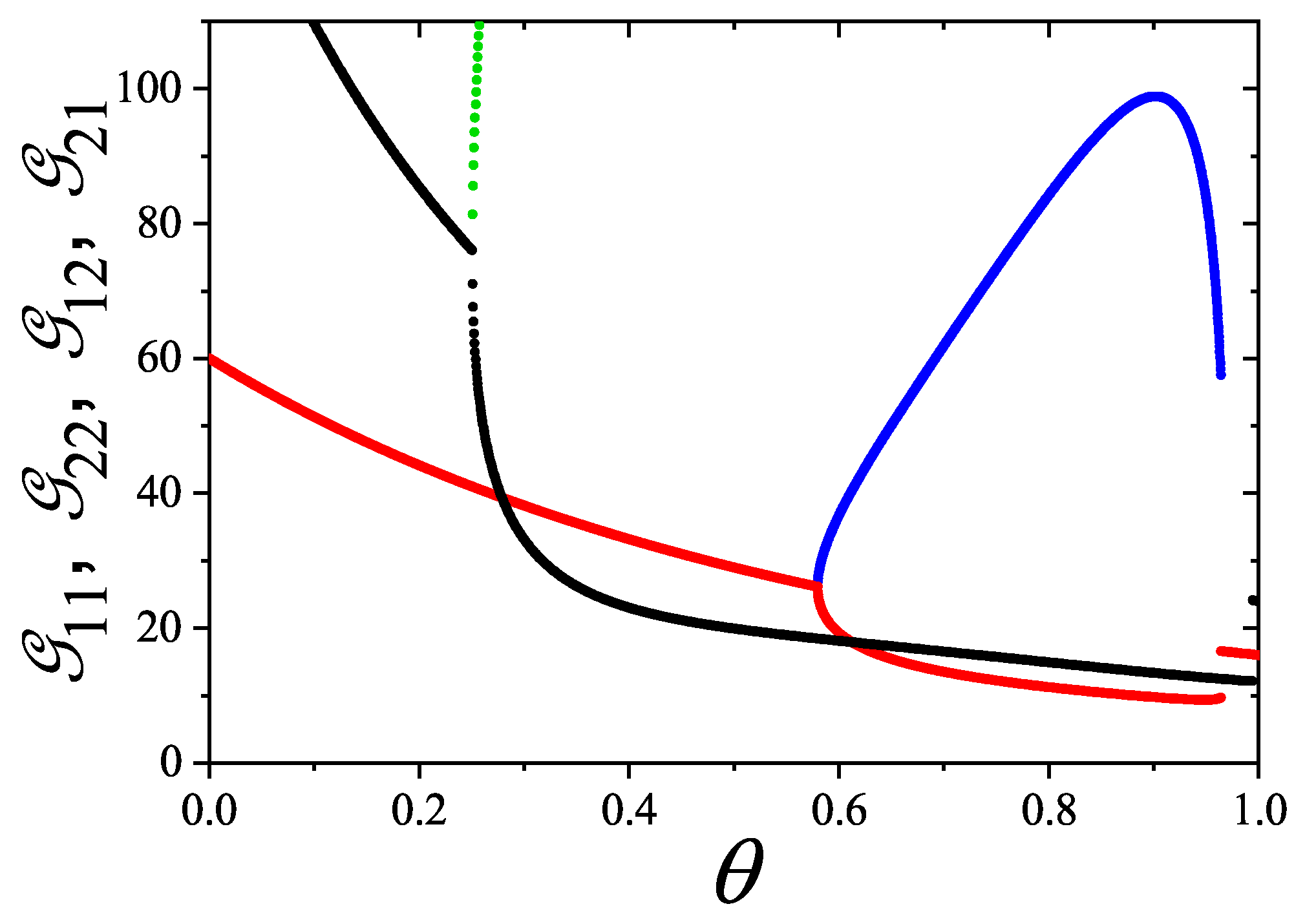

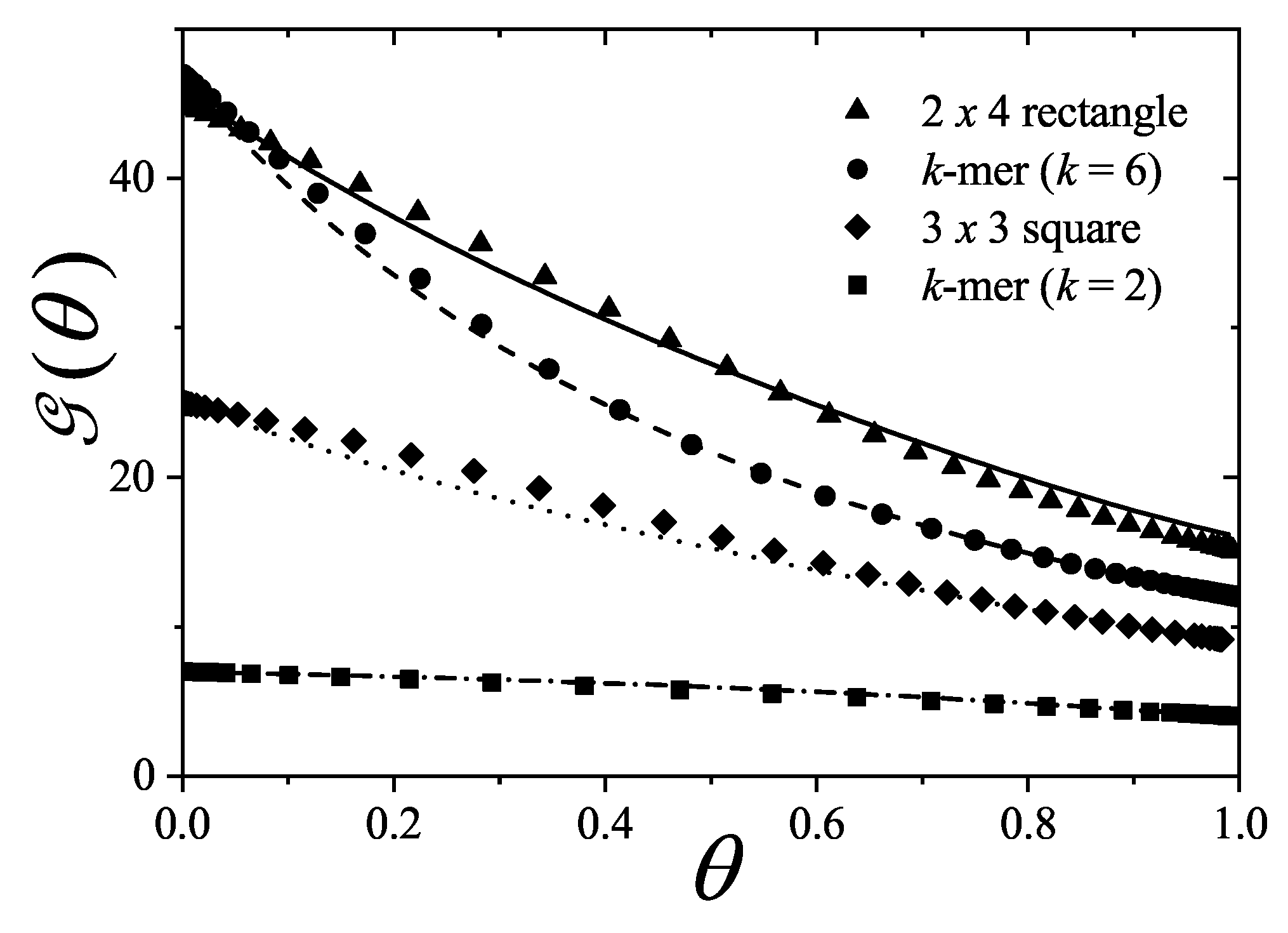

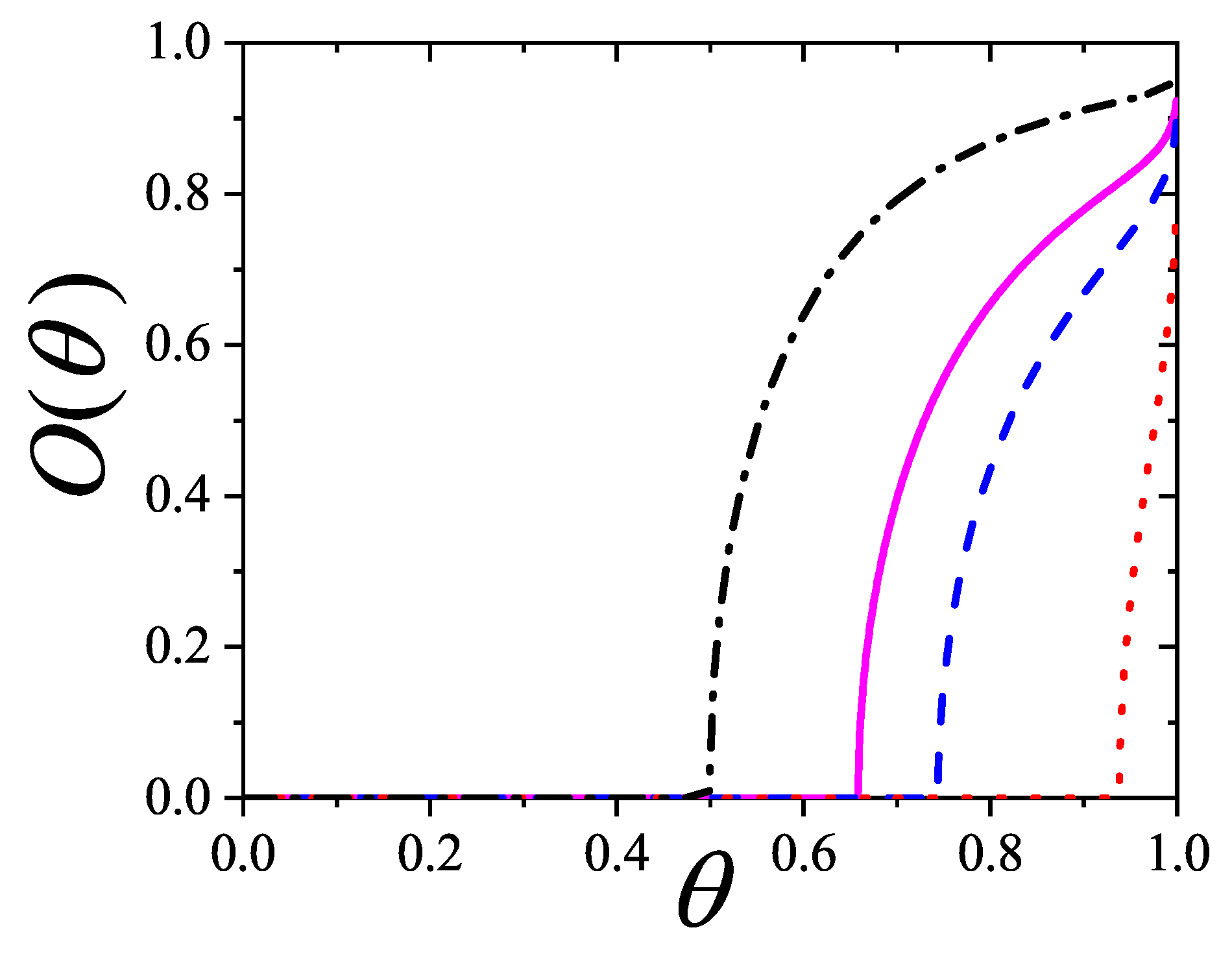

5.6. Exclusion Spectrum Functions

A singular outcome of this formalism is the thermodynamic characterization of the configuration space or state exclusion spectrum through the exclusion per particle frequency function and the cumulative exclusion per particle function , referred to collectively as exclusion spectrum functions.

From Equations (

291) and (

292), both

and

can be expressed in terms of the density dependence of the chemical potential, providing a thermodynamic description of equilibrium particle configurations.

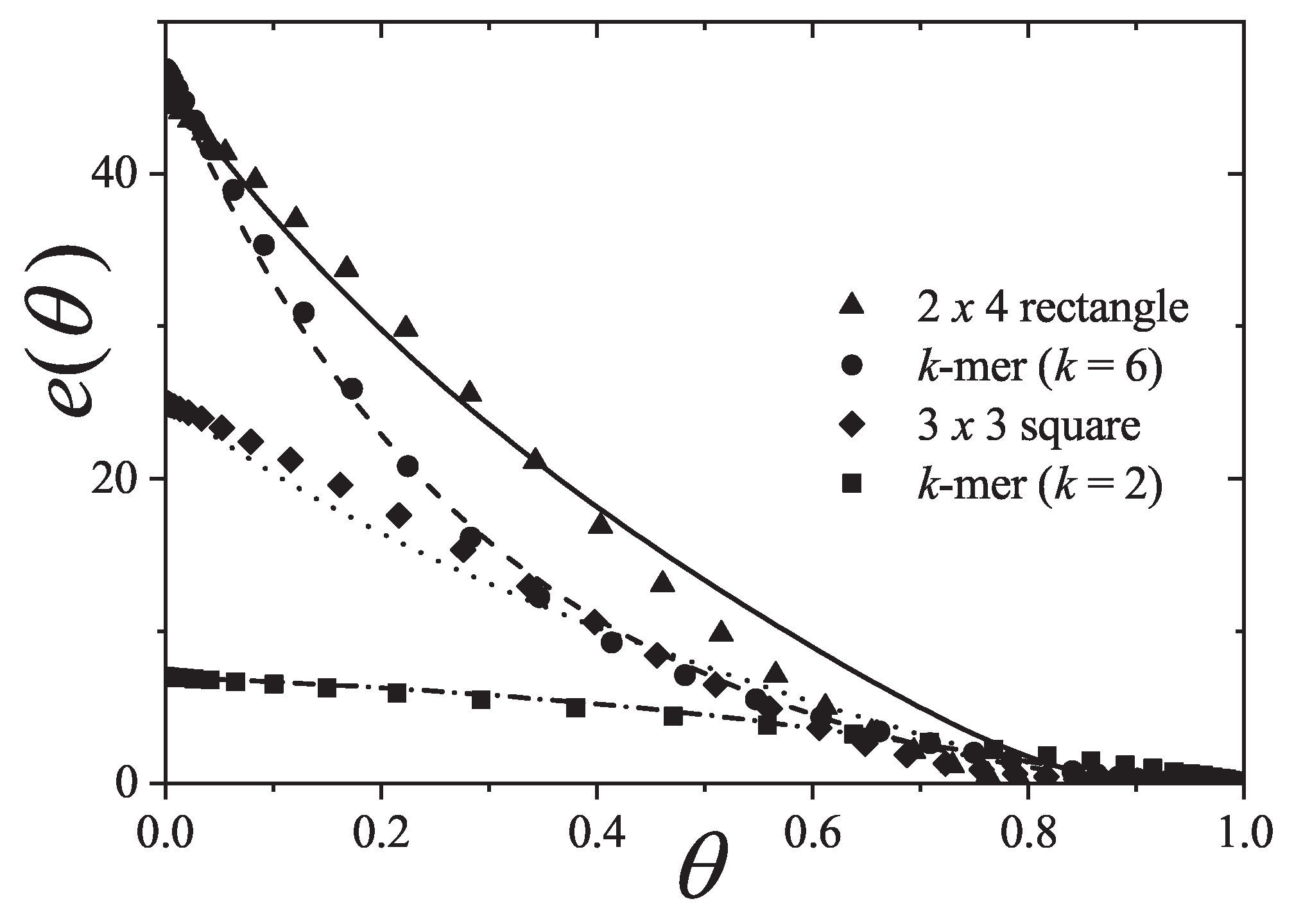

Illustrative results for

and

for

k-mers, squares, and rectangles in the isotropic phase are shown in

Figure 20 and

Figure 21. Analytical results are shown as lines, and MC simulation data are indicated with symbols:

rectangles (triangles),

k-mers (circles),

squares (diamonds), and

k-mers (squares). The simulations were performed following the same scheme and using the same parameters as those used in

Section 5.5.

For

with

, both

and

decrease rapidly with increasing coverage:

and

. In contrast, in a 1D lattice with

, the decay is slower:

and

(not shown in

Figure 20 and

Figure 21 for clarity).

In the other cases shown: for rectangles, , , , ; for squares, , , , ; for k-mers, , , , . A good agreement is observed between analytical predictions and MC data for both and , particularly for . At saturation, , since each particle excludes on average g states, and , as all single-particle states are either occupied or excluded.

As shown in

Figure 20 and

Figure 21,

statistics provides an accurate description of the exclusion spectrum functions across the full range of

. In particular, the results for

k-mers show excellent agreement for both small and large

k. Moreover, particles with higher

g tend to exhibit larger values of

, regardless of shape. In contrast,

captures more detailed configuration-specific features, as evidenced in

Figure 21. For instance, while isolated

k-mers exclude more states than

squares, there exists an intermediate coverage range

where they exclude fewer states per particle. This indicates local alignment among

k-mers at high

, reducing exclusion relative to a disordered configuration.

These results confirm that statistics captures the thermodynamic signature of configurational exclusion with remarkable accuracy across all densities. A more in-depth analysis of the exclusion spectrum and its behavior near phase transitions is provided discussed in following sections.

5.7. Adsorption of Polyatomics: Relation Between Exclusion Functions, Thermodynamic Observables, and Adsorption Field Topology

In this section, we explore potential applications of the exclusion spectrum functions defined in

Section 5.1 in connection with experimental thermodynamic measurements. This relation provides insight into how adsorbed particles occupy and exclude states based on the spatial distribution of local minima in the adsorption field—here generically referred to as the adsorption field topology.

The average exclusion spectrum function

connects a configurational property, related to the spatial correlation of states and influenced by particle geometry, to the density dependence of a thermodynamic observable such as the chemical potential. From the relation

or equivalently , it becomes apparent that these exclusion functions can, in principle, be inferred from experiments via the dependence of on n.

A more refined exclusion description is provided by the frequency function

. Introducing

, we have

and

. Hence, the analytical or experimental form of

encapsulates the configurational exclusion information. Thus, for a given shape and size of adsorbate molecule the number of states at very low coverage could be determined and the spatial arrangement of the adsorption potential minima could be inferred, so called here, the adsorption potential topology [

18]. Additionally, the complete configuration changes on density are embodied in

and

through

. A more detailed experimental analysis of adsorption isotherms on well-defined particle–substrate systems is needed to assess the feasibility and value of this configurational framework, though that lies beyond the scope of the present review.

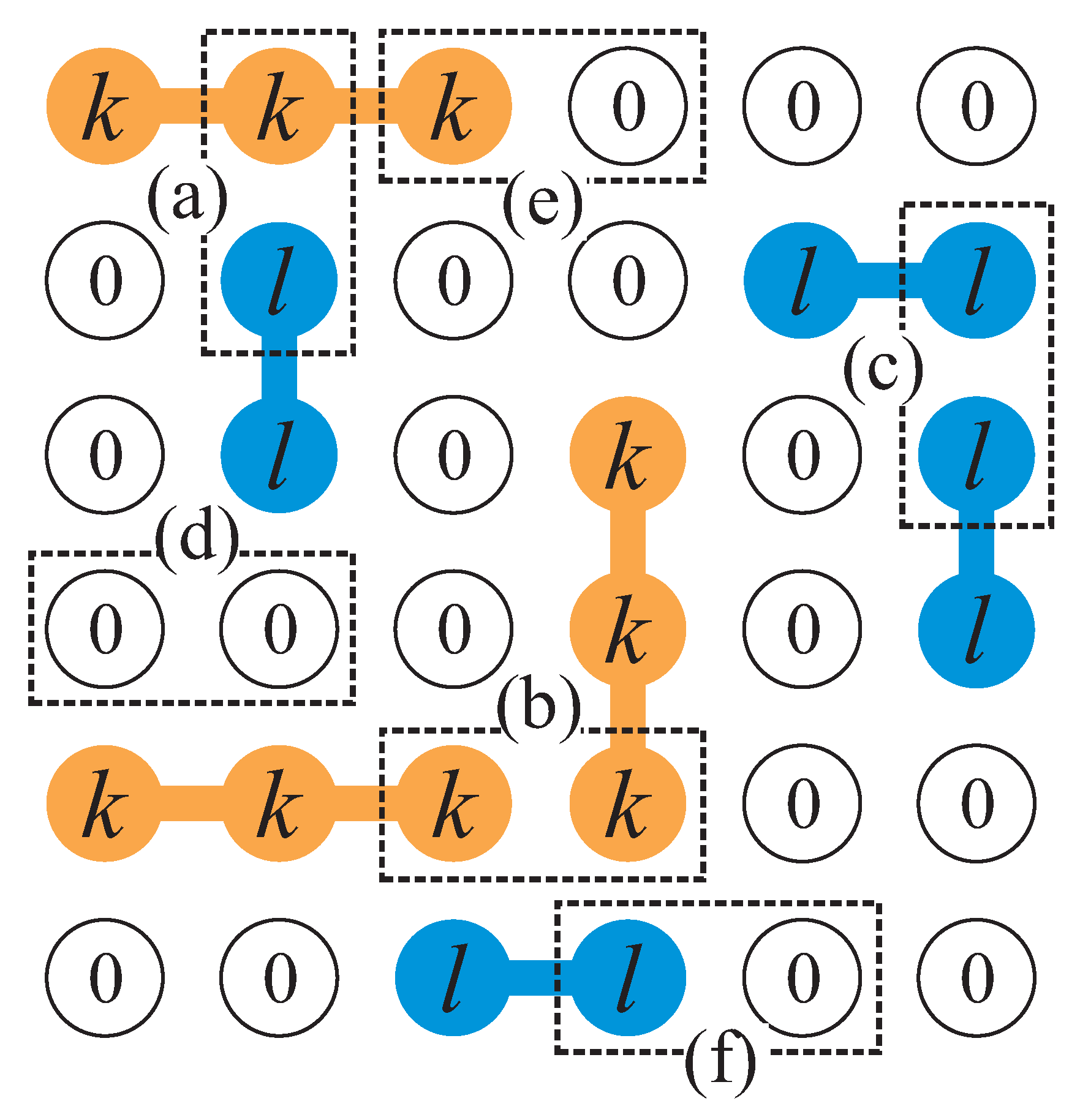

6. Latest Developments, Part II: Multiple Exclusion Statistics Formulation for Mixtures

In this section the statistical thermodynamics framework is extended to describe mixtures of particles with arbitrary size and shape, each having a spectrum of topologically correlated states and subject to statistical exclusion. A generalized distribution is obtained from a configuration space ansatz recently proposed for single species, accounting for the multiple exclusion phenomenon, where correlated states can be simultaneously excluded by more than one particle. Statistical exclusion on correlated state spectra is characterized by parameters , which are self-consistently determined. Self- and cross-exclusion spectral functions and are introduced to describe the density-dependent exclusion behavior. In the limit of uncorrelated states, the formalism recovers Haldane’s statistics and Wu’s distribution for single species and for mixtures of mutually excluding species with constant exclusion.

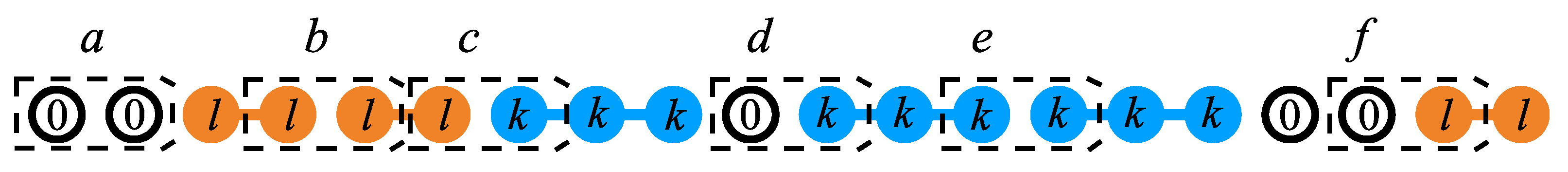

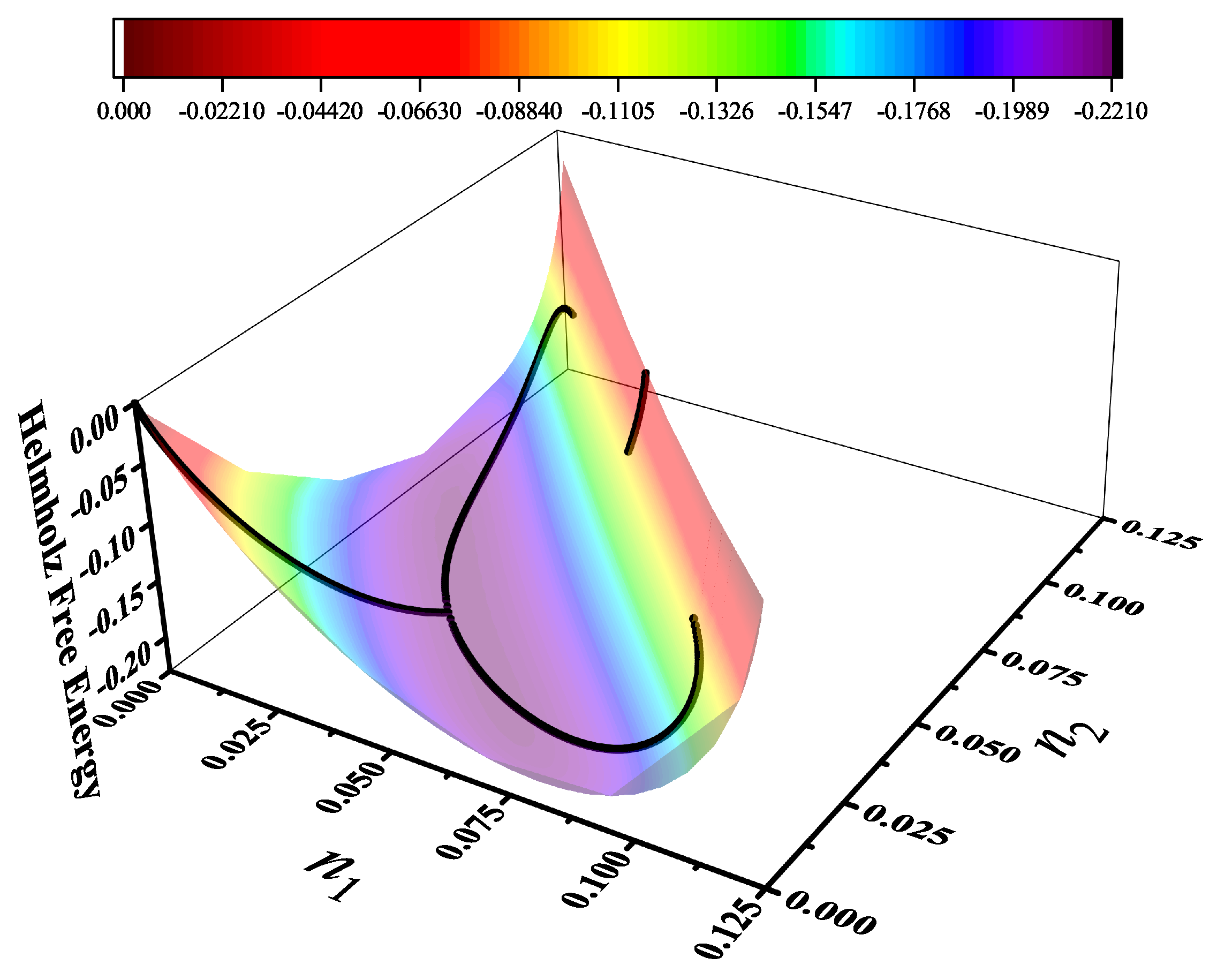

The formalism is latter applied to k-mers on the square lattice, modeled as a mixture of two orthogonally oriented, self- and cross-excluding pseudo-species. This approach offers a general and consistent framework for entropy-complex lattice gases. It reproduces k-mer phase transitions and provides access to configurational information through the exclusion spectrum functions. We summarize here basis of this approach for mixtures and the relevant analytical predictions for rigid k-mers on the square lattice are discussed in the section devoted to applications.

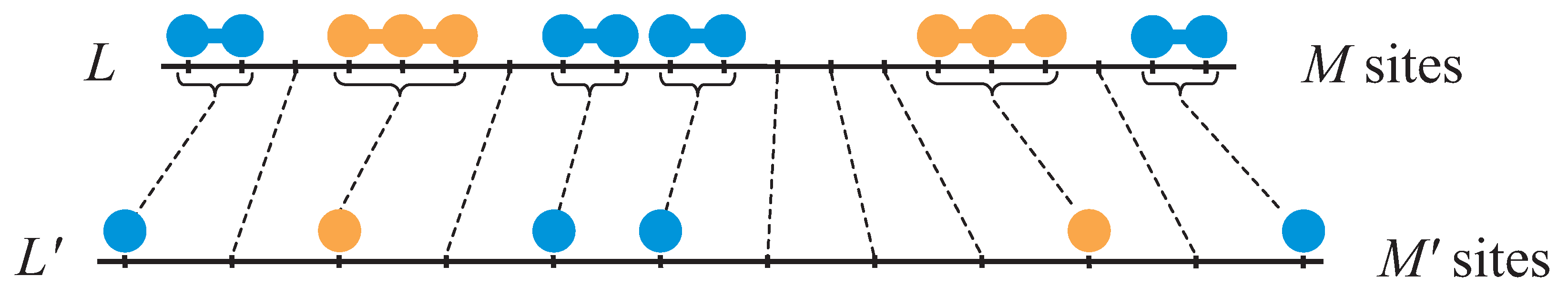

6.1. State Counting Approximation and Density of States for Mixtures with Multiple State Exclusion

The general self-consistent formulation for the thermodynamics of mixtures consisting of an arbitrary number of species in a volume

V is summarized in the following subsections. Each species are assumed to exclude accessible states to itself and to the others, a phenomenon intensified by spatial correlations among the states—referred to as Multiple Exclusion Statistics (

) [

17]. This leads to a particularly challenging statistical problem, especially in lattice models involving linear or arbitrarily shaped particles.

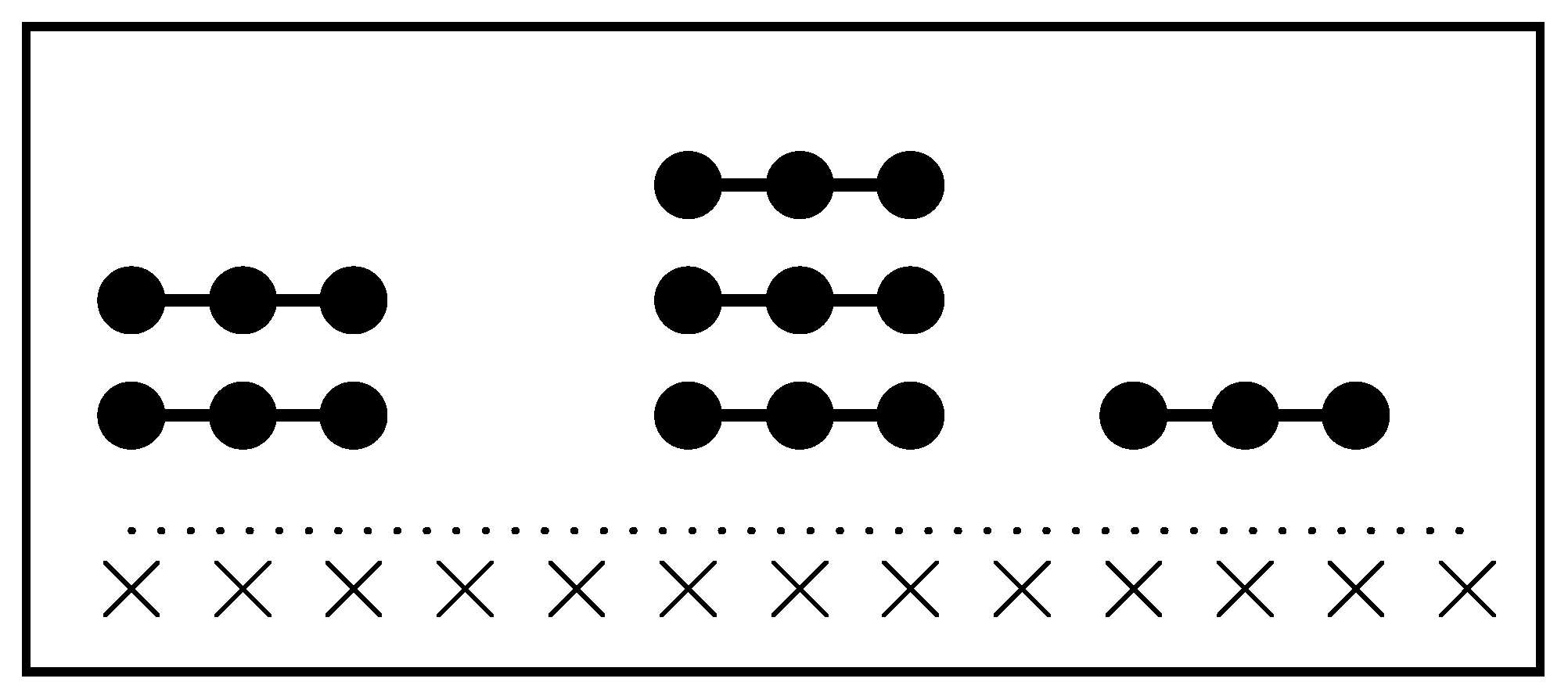

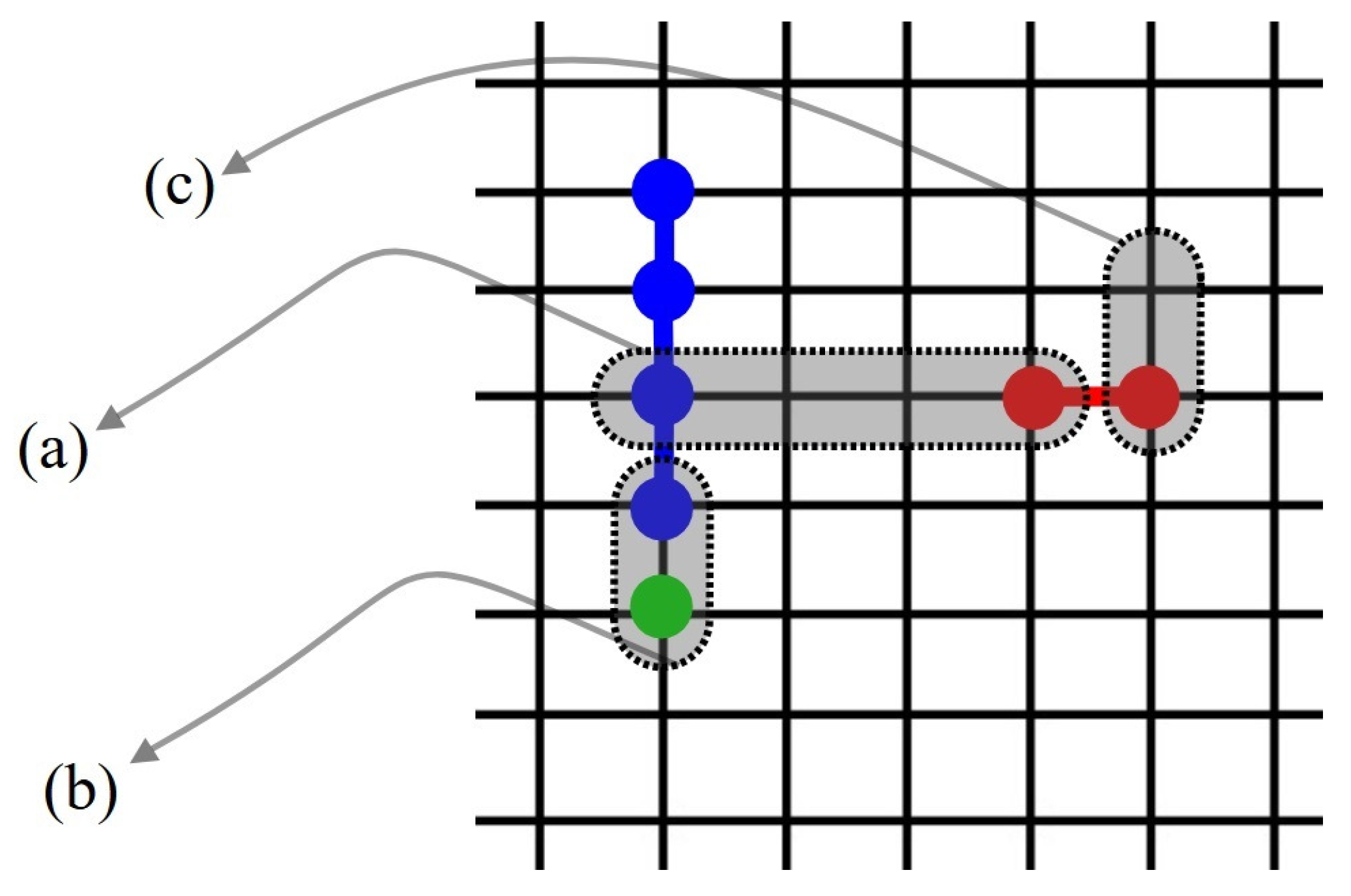

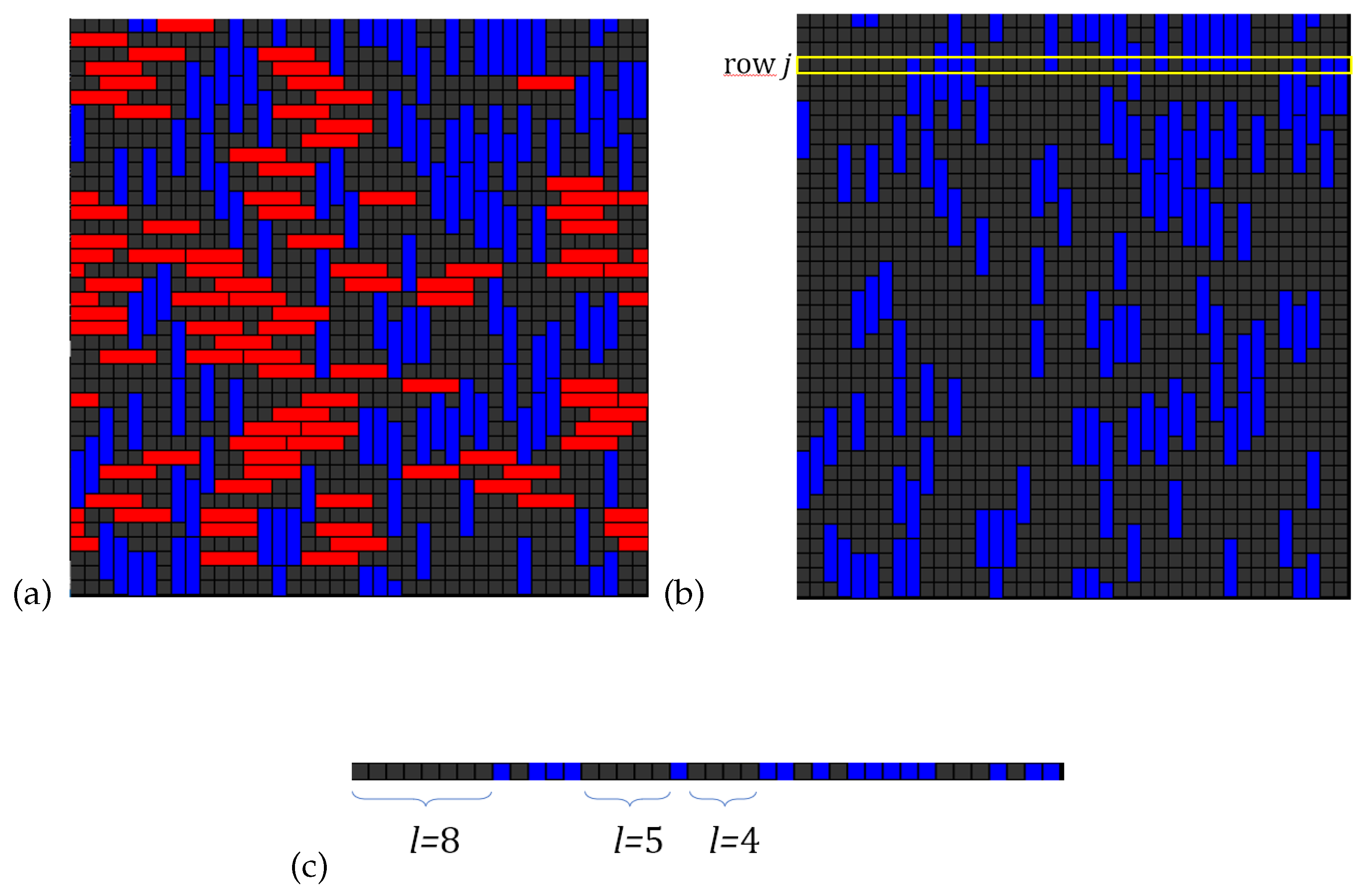

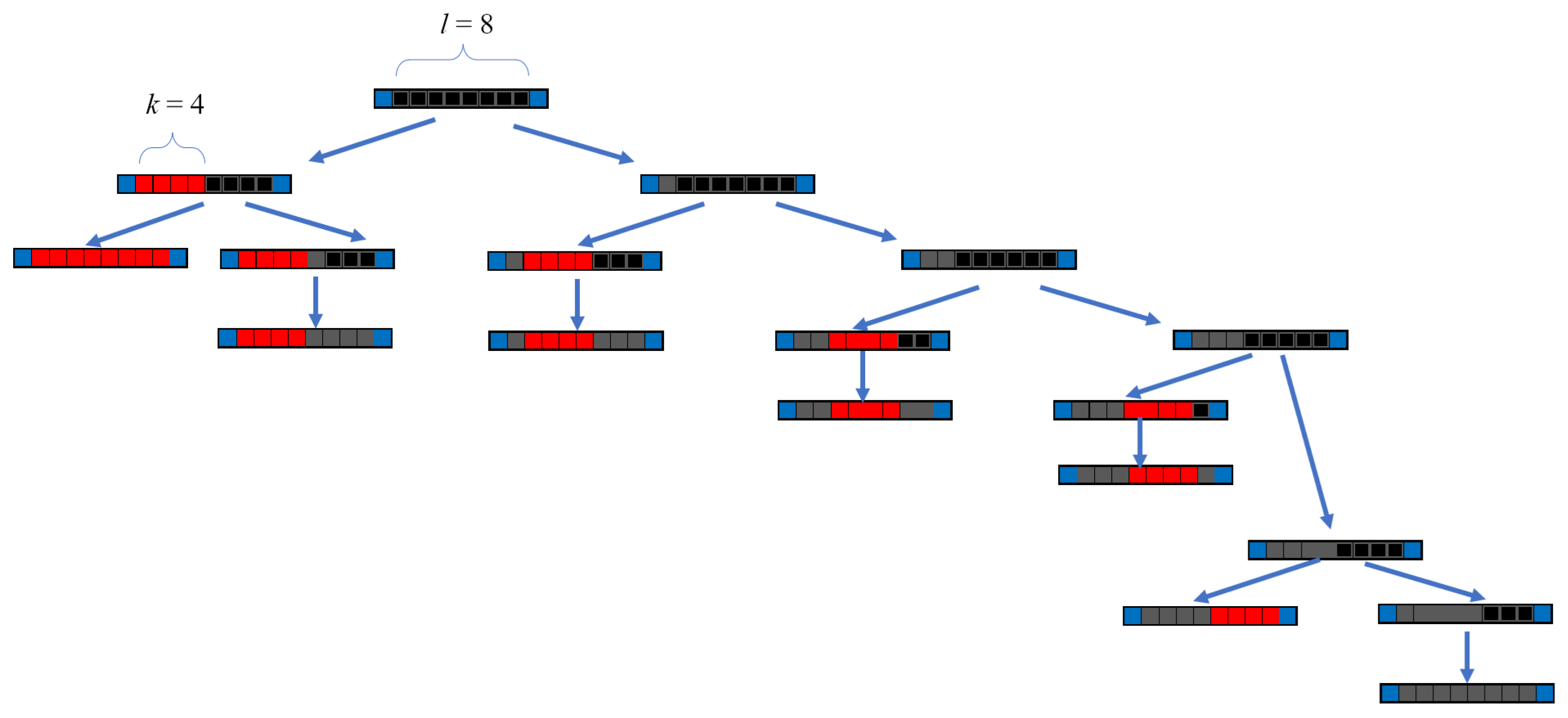

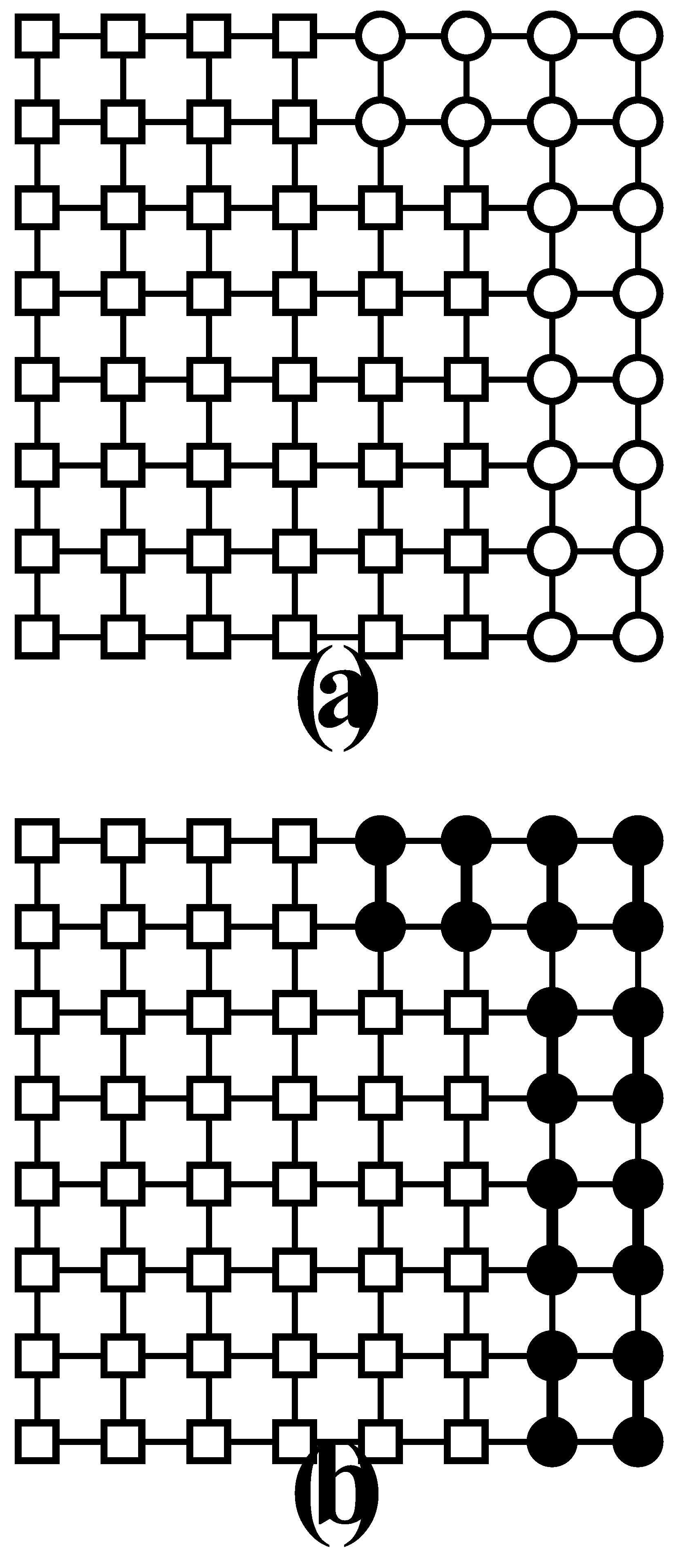

Figure 22 illustrates

through a ternary mixture of monomers, dimers, and tetramers. The single-species theory of Ref. [

18] was extended to mixtures and state density and exclusion distribution functions were derived [

19] in order to formulate an analytical thermodynamic model applicable to

k-mers on lattices with correlated spectra as well to other particle shapes.

We define the self- and cross-exclusion parameters and based on the number of states excluded per particle at saturation. Let be the total states available to an isolated particle of species i and its number in V. The occupation number is , with its maximum, and .

Cross-exclusion is rather more subtle-quantified by , where are the non-excluded states of i when j saturates the system. Expressed in terms of fractions: , with and .

The canonical partition function is , where is the energy per particle(eventually, due to an external field such as the interaction with the lattice)and henceforth. The configurational term captures how particles distribute over their respective sets of accessible states.

We define

as the number of states available to a particle of species

i given occupation vector

(and analogously for

). Generalizing the form introduced in [

18] for single species, the configuration count is:

Using Stirling’s approximation and defining

, the Helmholtz free energy becomes:

In the thermodynamic limit, we define the free energy per state of species

i as

. This leads to:

where

.

The entropy per state (in units of

) follows from Equation (

306):

In general, depends not only on the occupation vector but also on the microstates, which are inaccessible analytically. Thus, we postulate a functional form based on average occupations—sufficient for thermodynamic descriptions. The next section formalizes the derivation of based on a counting ansatz and pairwise exclusion analysis.

It is worth noting that the expression for

is exact only if particles can occupy states that are completely independent of one another. This is the case in the Haldane-Wu

g-statistics framework discussed in Ref. [

18], where each particle excludes

g states regardless of

N or the specific configuration. For a single species, this leads to

with constant

g, while for a mixture, the generalized form becomes

with constants

. In general, however,

in Equation (

304) is only approximate, since the actual number of available states for species

i should depend not only on

but also on the specific microscopic configuration of the ensemble; that is, it should be configuration-dependent.

Yet, since exact configuration counting is intractable, we develop a general approximation for based on a state counting ansatz. In the thermodynamic limit, this approach yields the density of states as a function only of the average occupation numbers at equilibrium. This can be interpreted as the effective density of states corresponding to typical equilibrium configurations which contribute most significantly to the system’s entropy.

We now show the derivation of the functional form of . Let denote the set of available states for a single particle of species i, with cardinality . We define the tuple , whose components correspond to the total number of states for each species.

To quantify how the presence of other species modifies the state space of species i, we denote by the number of available states for a particle of species i when the system contains particles in total, satisfying when for all j. We first isolate the effect of species j on species i by defining under the condition , with only species j present.

The recursion relation introduced in

Section 5 for single species can be extended to such pair interactions. The function

is then defined recursively as follows:

in general,

where

denotes the number of states of species

i excluded by the

-th particle of species

j added to the system.

Following the analogy with the single-species case, we posit that . Here, the term 1 accounts for the exclusion of at least one state, while represents the additional number of excluded states due to spatial correlations between the state spectra of species i and j.

The correlation term

is defined by the state counting ansatz [

17] as

. Substituting this into the recursive definition yields:

and so forth. The general expression becomes:

valid for

.

For convenience, we introduce in Equation (

309) the rescaled exclusion parameters

, and similarly

, where

and

.

By retaining only the leading term of the summation in Equation (

310) and taking the thermodynamic limit

, with

,

, and

, we obtain:

which yields

, in agreement with the approximation proposed in Ref. [

17]. Here,

represents the fraction of states of species

i that remain available in the presence of a concentration

of species

j, under the condition that all other species are absent (

for

). Statistically, this function encodes the depletion of the state spectrum of species

i due to the presence of species

j, and can be interpreted as a pairwise statistical interaction function.

The function

must satisfy the boundary conditions

and

. To ensure this, we define constants

and

such that

. Imposing the boundary conditions yields

and

. Therefore, the final expression for the pair function becomes:

Because of the spatial self- and cross-correlations, state multiple exclusions occur for a given microscopical configuration of the statistical ensemble (as shown in

Figure 22), then, the total fraction of states excluded to a given species

i by the others species is not merely

, being

the fraction of states of

i excluded by

j at

. Accordingly, the fraction of states for a particle of species

i when all the species are coexisting, namely

, corresponds to the ratio between the number of states in the intersection sets

and the total number of states

. Ultimately, the total fraction of states for a single particle of species

i at occupation

of all the species is given by

, which can be approximated by

.

Figure 23.

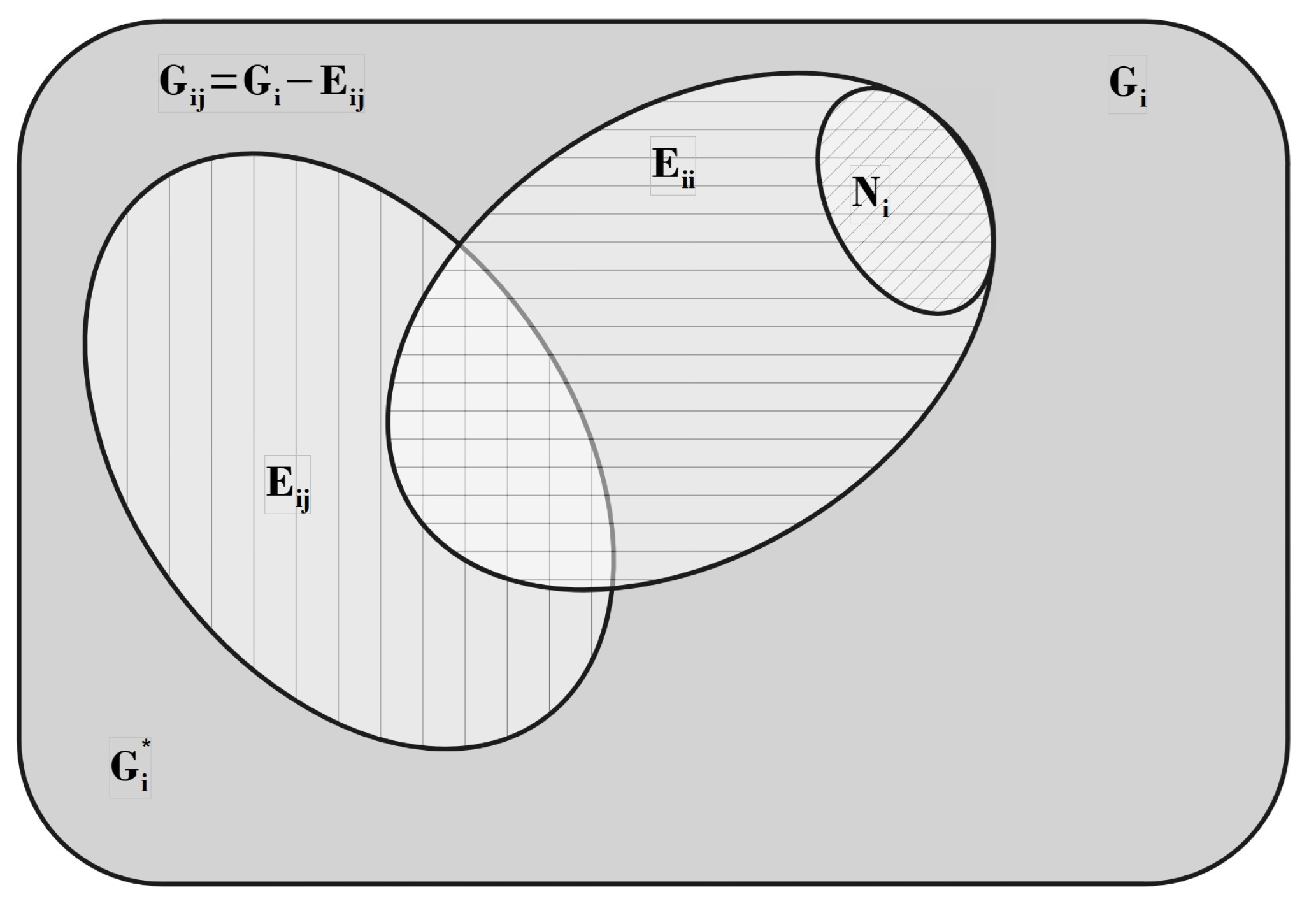

Symbolic representation of the species i’s states set (whole framed area) whose elements are the states accessible to species i when for , being its cardinality. represent the sets of states of a particle of species i excluded by the particles of species , respectively (shown generically and by the areas filled by vertical and horizontal lines), being their cardinalities, respectively. The states occupied by species i are represented by the set (oblique lines area). represents the set of states for particles of species i not excluded by particles of species j. The intersection is the set of states for a particle of species i non-excluded by any of the species (dark gray area), with cardinality and fraction .

Figure 23.

Symbolic representation of the species i’s states set (whole framed area) whose elements are the states accessible to species i when for , being its cardinality. represent the sets of states of a particle of species i excluded by the particles of species , respectively (shown generically and by the areas filled by vertical and horizontal lines), being their cardinalities, respectively. The states occupied by species i are represented by the set (oblique lines area). represents the set of states for particles of species i not excluded by particles of species j. The intersection is the set of states for a particle of species i non-excluded by any of the species (dark gray area), with cardinality and fraction .

It is worth noticing that the fraction

can also be interpreted as the probability for a state of species

i being non-excluded by particles of species

j. Accordingly,

represents the probability that a state of species

i is simultaneously non-excluded by all species. Then, assuming in a first approximation that the pairs cross-exclusion events are independent,

can be written as

where the functions

are given by Equation (

311).

In order to finally obtain

as defined in Equation (

306) from

in Equation (

312), and by denoting

, it is required that

satisfies

and

13, where

is the maximum occupation of species

i when other species are at densities

.

Introducing normalization constants

and

so that

, and using

, the boundary conditions are fulfilled by setting

and

. Then, the density of states reads

for

, with

given by Equation (

311).

The Helmholtz free energy for the generalized mixture on spatially correlated states can now be computed from Equations (

311), (

313), and (

306), providing the full thermodynamic behavior.

As will be discussed in the applications, the quantities

can be predetermined in model systems such as

k-mer mixtures on regular lattices from the system symmetry

14.

Finally, note that the set cardinalities in this derivation do not depend on specific microstates, but represent effective values for configurations at equilibrium minimizing the Helmholtz free energy at given T and V (i.e., given ).

The parameters

are consistently determined from particle and lattice properties (size, shape, connectivity), and from thermodynamic boundary conditions by generalizing the analysis developed introduced for single-component systems [

18] .

6.2. Mixtures Statistical Thermodynamics

From the Helmholtz free energy in Equation (

306) we derive the density dependence of the chemical potential

,

consequently, from Equations (

306) and (

314),

where, for the sake of shortness, the explicit dependence of

on

is implicit in Equation (

315) and

. We write Equation (

315) more conveniently as

with

for

which straightforwardly give the chemical potentials

as a function of the species state occupation numbers

, or specie’s density. The Equation (

316) also represents a system of

s-coupled equations whose solutions are the species occupation numbers

for given chemical potentials

.

By defining

, Equation (

316) can be rewritten as

or

which are the coupled equations within the

statistics from which the equilibrium distributions

can be determined.

It is worth noticing that Equation (

318) reduces to Wu’s distribution for fractional exclusion statistics [

15] when the species’s states are spatially uncorrelated. An alternative picture of what the Wu’s limiting case of spatially uncorrelated species’s states means here is that the numbers of self-excluded and cross-excluded states per particle are constants in Wu’s formalism [

15] and density dependent in

statistics.

6.3. State Exclusion Spectrum Functions: Determination of Exclusion Correlation Parameters

This section is devoted to determining the parameters from the thermodynamic limits of the exclusion spectrum functions, which quantify the average cumulative number of self-excluded and cross-excluded states per particle as functions of the occupation numbers . For model systems where both the size/shape of the particles and the spatial distribution of accessible states (e.g., the lattice geometry) are known, the values of can be determined within the statistics framework, enabling a complete thermodynamic description.

Assume that species

in volume

V can exchange particles with a reservoir at temperature

T and chemical potentials

. The time evolution of the mean occupation number

follows:

where

and

denote the average fractions of empty and occupied states for species

i, and

,

are the respective transition rates. At equilibrium,

and the detailed balance condition gives

. Since

, then from Equation (

316), we have

Substituting from Equation (

316), we obtain:

The generalized exclusion spectrum function is defined as

, which measures the total average fraction of states excluded to a particle of species

i at given occupations

(including both self- and cross-exclusion). The cumulative number of excluded states of species

i per particle of species

j, i.e., the spectrum function

, is defined as:

Additionally, the rate of excluded states per particle due to self- or cross-exclusion is given by the partial derivatives:

Let

,

, and

, which yield:

From Equations (

320) and (

322), it can be shown:

Solving for the self-exclusion parameters

,

where

refers to Lambert function (see

Section 5.4).

For the cross-exclusion case

For uncorrelated states (

),

and

, as in Wu’s formalism [

15].

The exclusion spectrum functions

are related to density and chemical potential through

Although this formulation links measurable thermodynamic quantities to exclusion spectrum functions, its experimental application, especially for mixtures, requires further work. In dicussing applications further on in

Section 7.8, we illustrate how

and

can be computed for

k-mers on a square lattice, their behaviour through the

k-mers transitions and usefulness display and characterize the order of transitions.

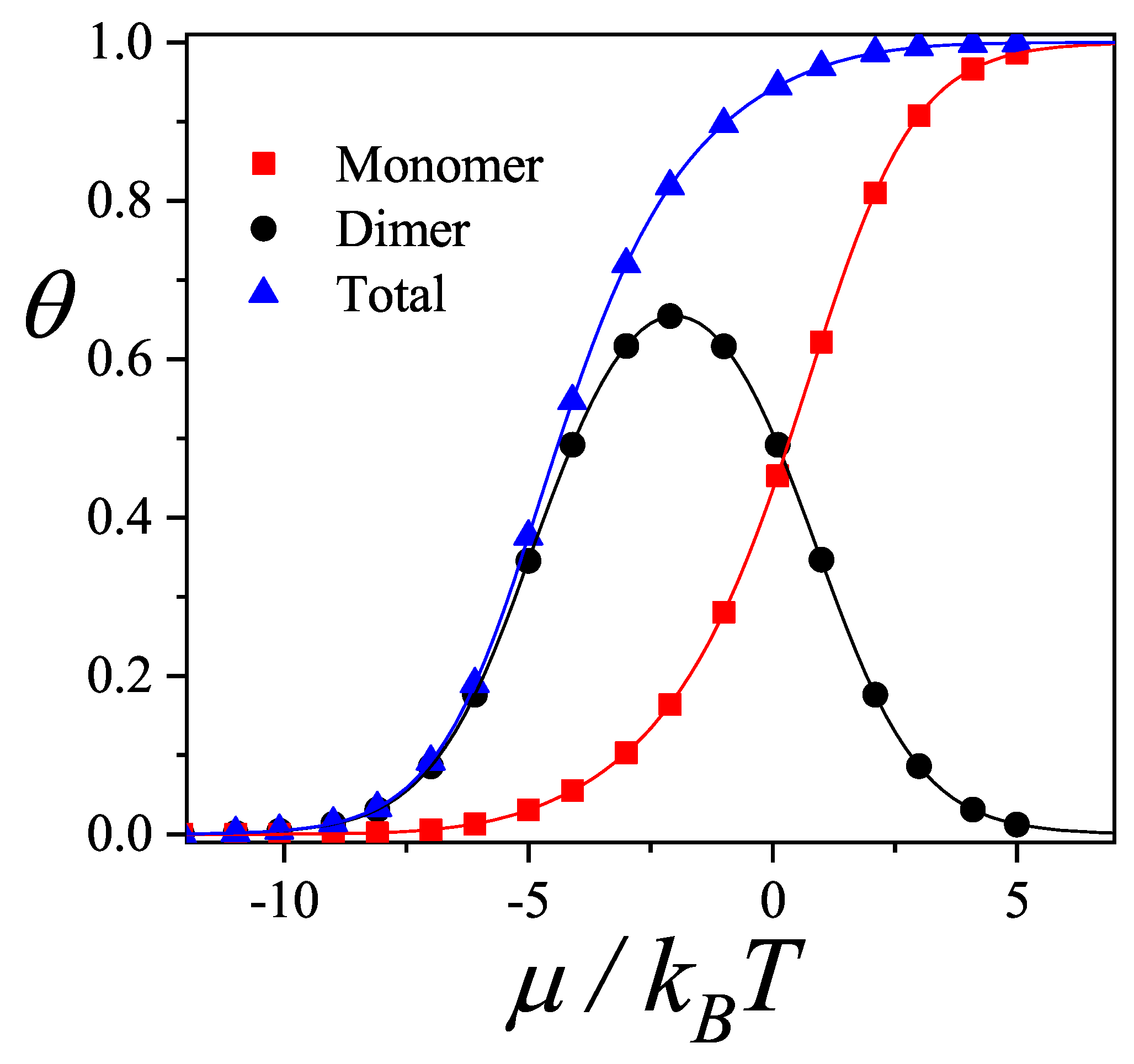

6.4. The k-Mers Problem as a Mixture Model: Basic Definitions

Preliminarly to applications of

statistics, which we will discuss in

Section 7.8, we introduce here the problem of

k-mers on square lattice of

M sites rationalized as a mixture of two differently oriented species.

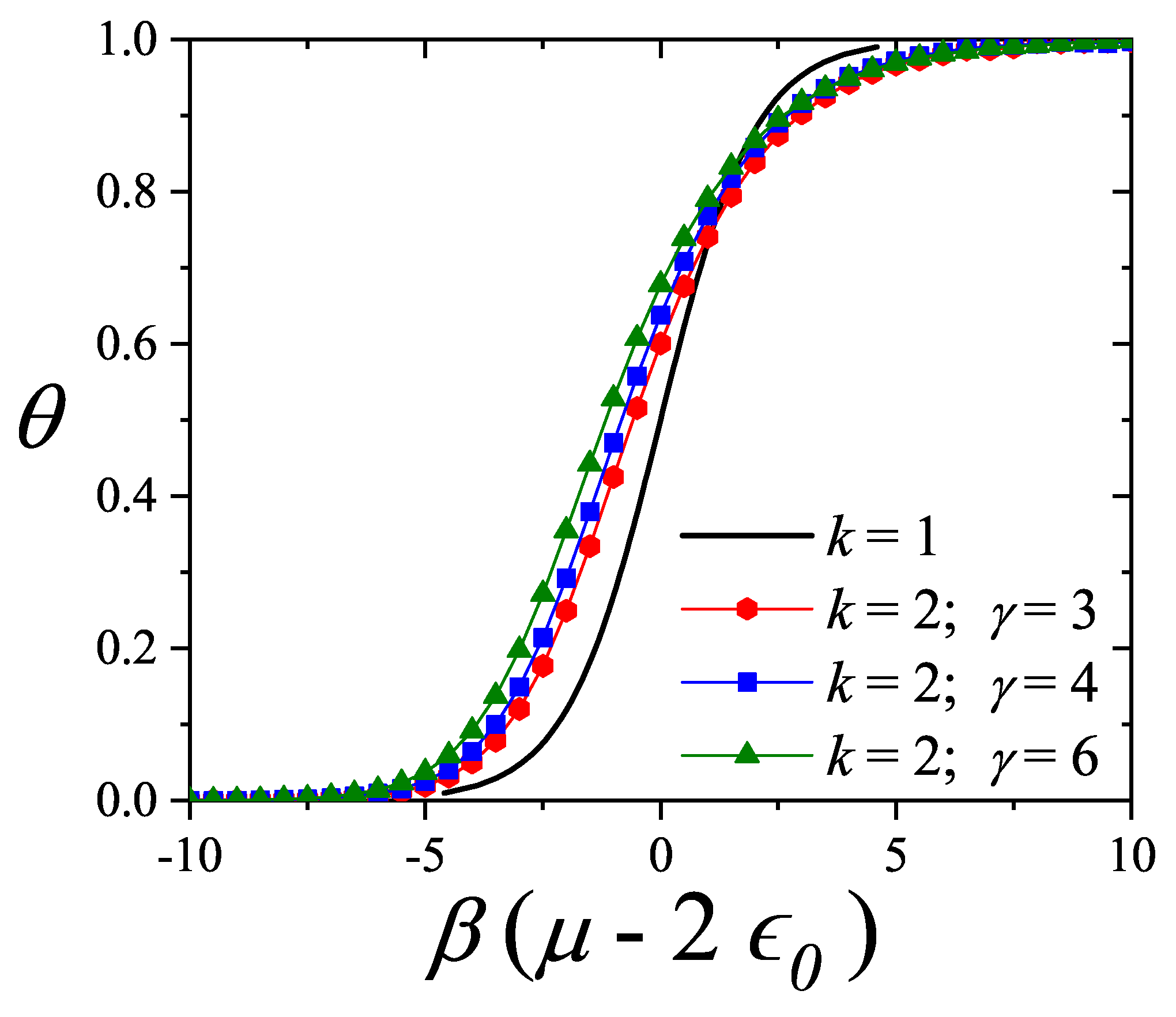

As discussed in

Section 5.5, the adsorption of straight rigid

k-mers on square lattices for

exhibits two distinct phase transitions: (1) a continuous, entropy-driven isotropic-to-nematic (I-N) transition occurring at intermediate surface coverage [

96,

101,

104], and (2) a nematic-to-isotropic (N-I) transition taking place at densities approaching lattice saturation [

106].

In Ref. [

18]

k-mers on the square lattice has been modeled as a binary mixture of species aligned along the horizontal (

) and vertical (

) lattice directions, denoted as species 1 and 2, respectively. Both species occupy

k consecutive lattice sites along their respective directions. According to our definitions:

,

,

, and

. The exclusion parameters are

, and the saturation values satisfy

.

From Equation (

313), the saturation occupations under coexistence are:

The self-exclusion at infinite dilution is , leading to . For cross-exclusion, each k-mer excludes states orthogonal to its direction, of which are shared. Thus, .

Using Equation (

326), the cross-exclusion correlations are

where

is the Lambert function. Solving this yields

for

,

for

,

for

, and

for

.

Based upon this elementary definition of the mixture parameter, the thermodynamic and exclusion functions in the

statistics, a much comprehensive treatment of the problem is given in

Section 7.8, leading to the entropy surface, equilibrium paths, density branches, order parameters, transition critical points and state exclusion spectrum are obtained for various values of

k.

7. Applications

In the present section, we analyze the scope and limitations of the theoretical models developed in previous sections by comparing them with Monte Carlo simulations and experimental data available in the literature.

7.1. Two-Dimensional Adsorption: Comparison Between Theory and Monte Carlo Simulations

In this section, adsorption isotherms are calculated for the theoretical models introduced in

Section 3 (

,

,

,

, and

) and compared both among themselves and against Monte Carlo simulations performed within the grand canonical ensemble framework [see

Section 8]. These comparisons are conducted for honeycomb, square, and triangular lattices.

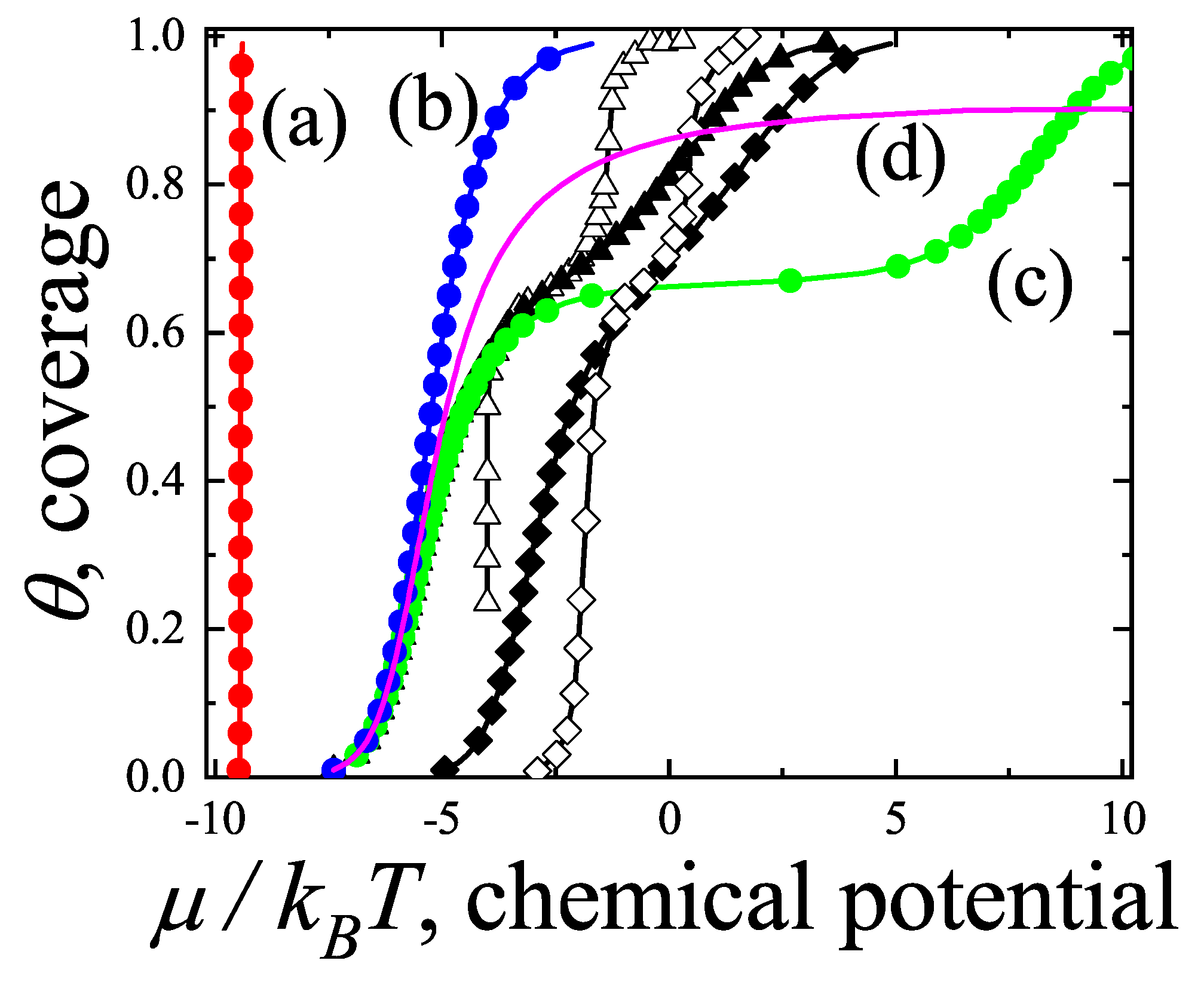

Monte Carlo simulations were carried out on honeycomb, square, and triangular lattices of size , with , and 150, respectively, using periodic boundary conditions. This lattice size ensures that finite-size effects are negligible. In addition, MCSs.

We begin by discussing some fundamental features of the adsorption isotherms.

Figure 24 presents a comparison between the exact adsorption isotherm for monomers and the simulated isotherms for dimers on honeycomb, square, and triangular lattices. As observed, the particle–vacancy symmetry, which holds for monoatomic adsorbates, breaks down when

. Furthermore, while the dimer adsorption isotherms appear similar across the different lattice types, the curves shift to lower values of

as the connectivity

increases. In other words, for a given value of

, the equilibrium surface coverage rises with increasing

. This behavior can be explained using the following relation:

which is valid for linear

k-mers at low concentrations [see Equation (

149)]. As the chemical potential increases, this effect diminishes, and consequently, the slope of the isotherms decreases with increasing

.

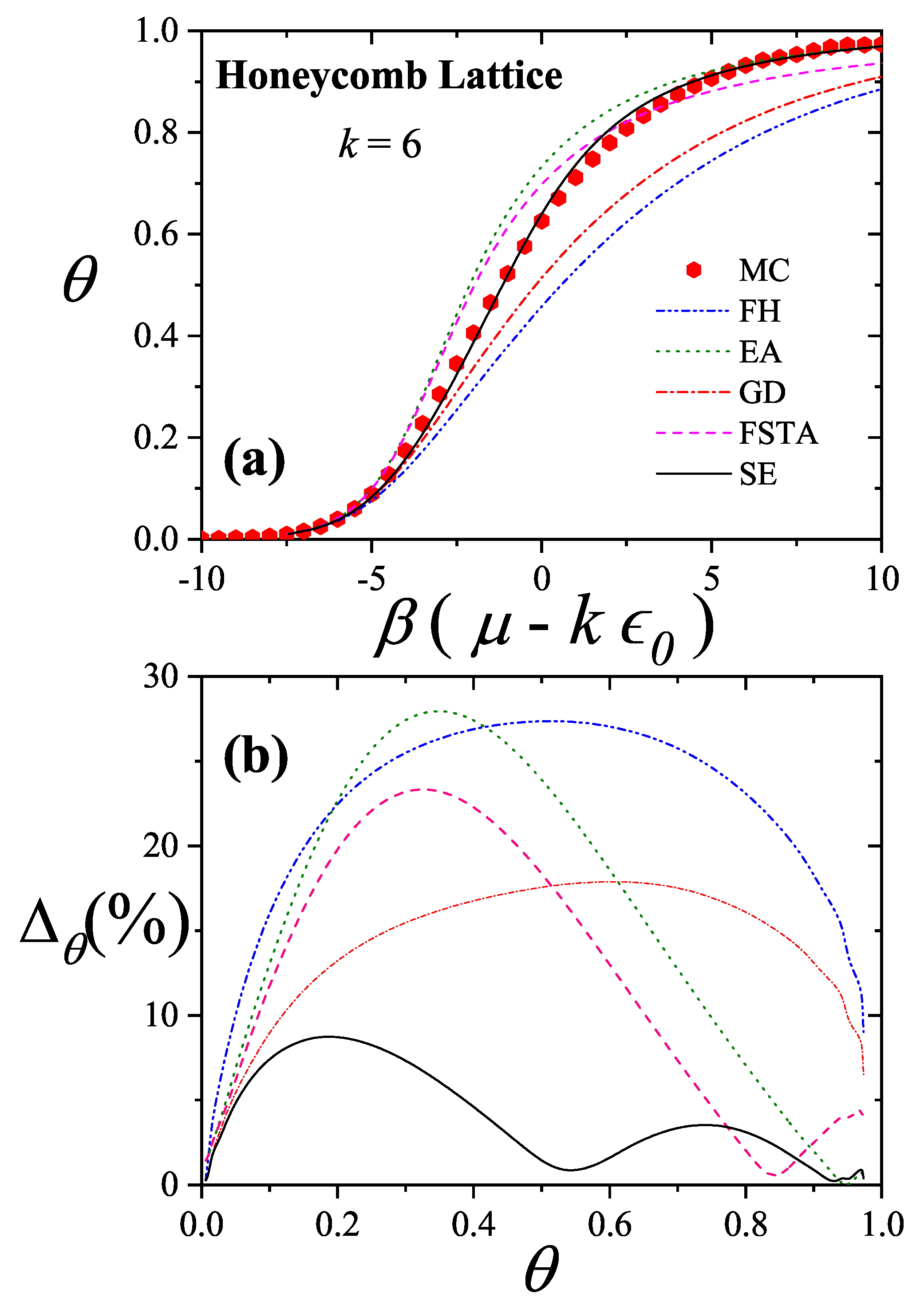

We now consider the case of linear adsorbates larger than dimers. For honeycomb lattices,

k-mers adsorb as described in

Section 3.1.1. When a site is selected, there are six possible equilibrium orientations for a single

k-mer (

) at extremely low coverage, resulting in a total number of

k-uples equal to

(i.e.,

), as is also the case for triangular lattices.

Based on these conditions, extensive simulations were conducted for linear adsorbates with

k ranging from 2 to 10. As illustrative examples,

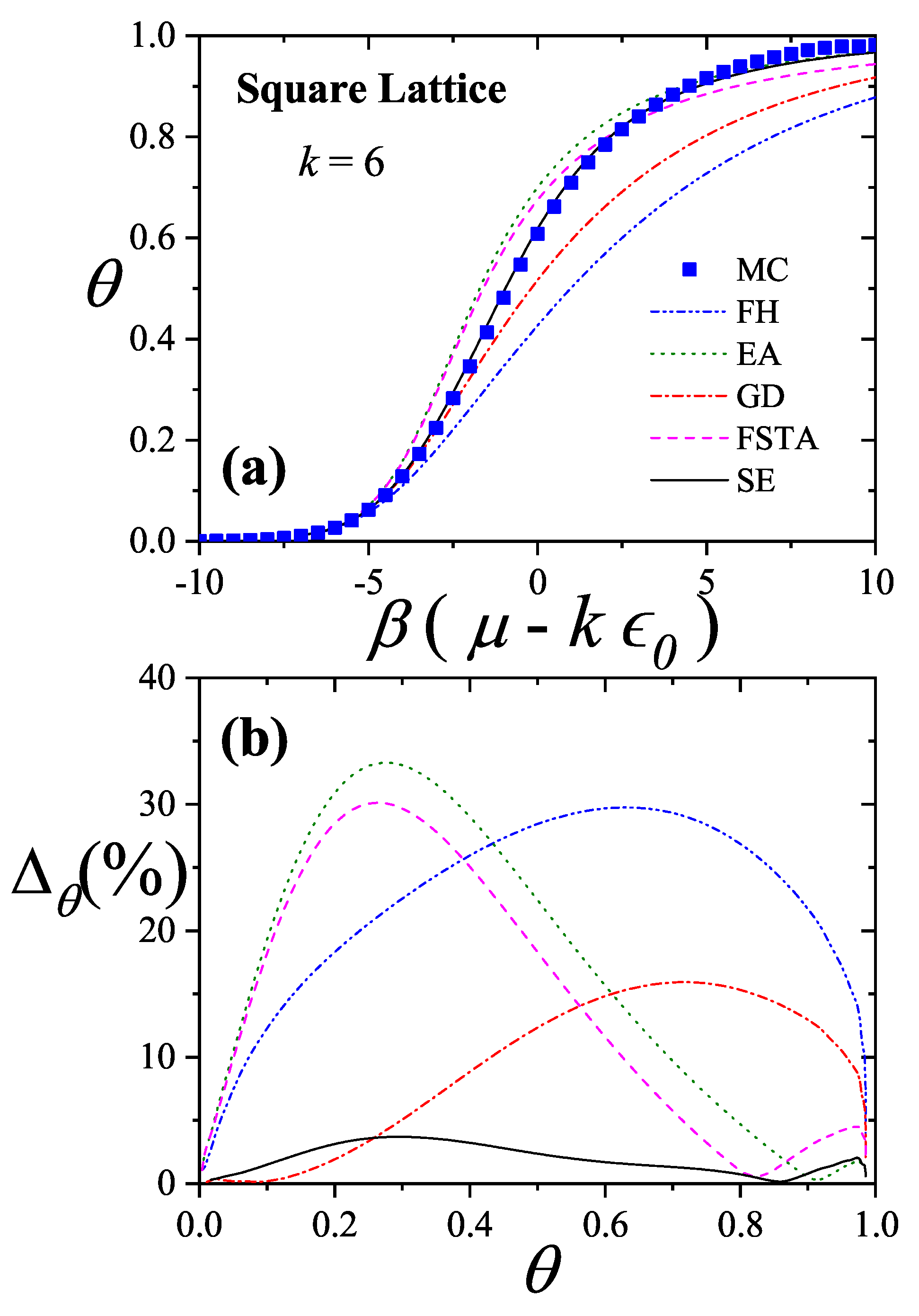

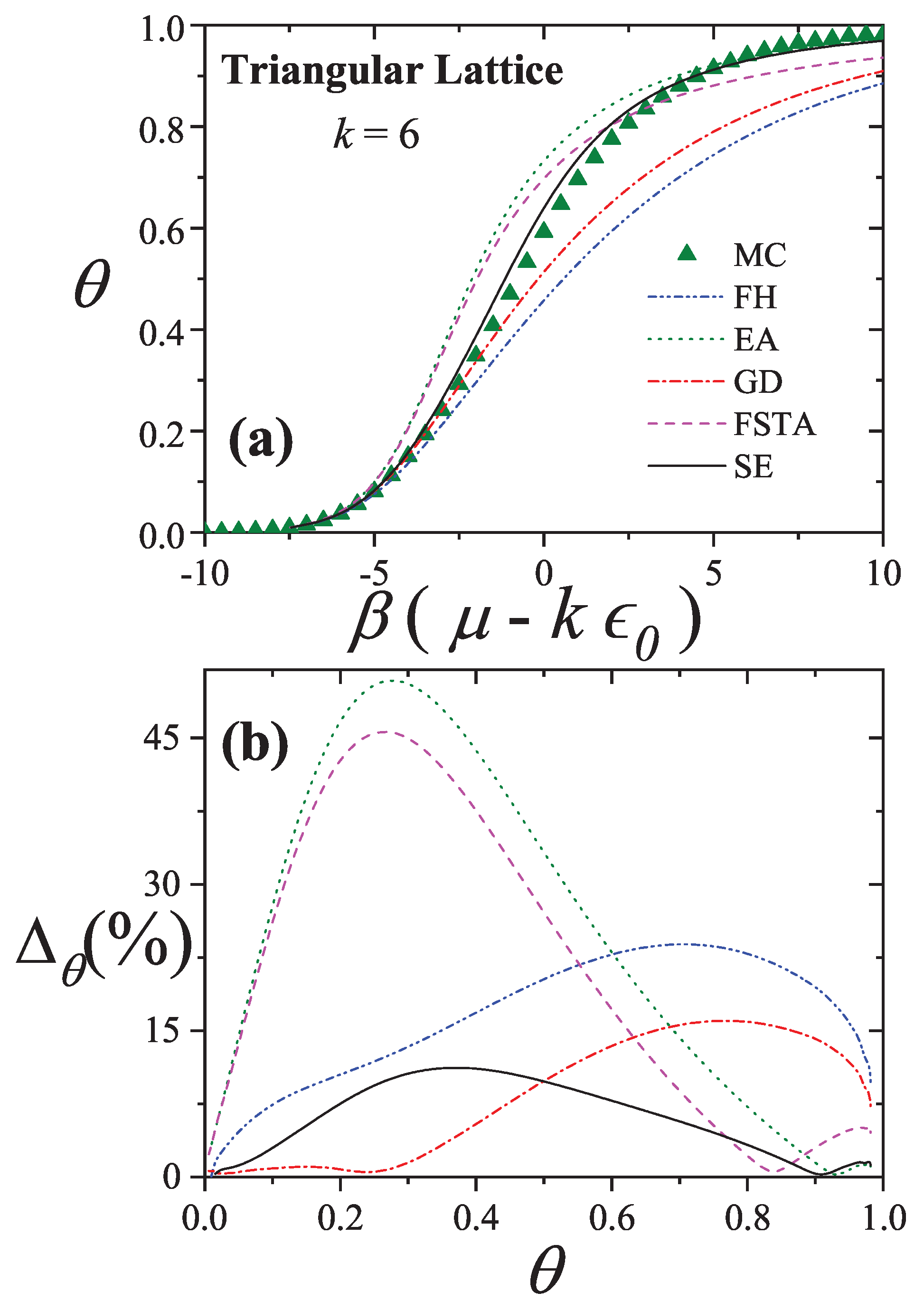

Figure 25(a),

Figure 26(a), and

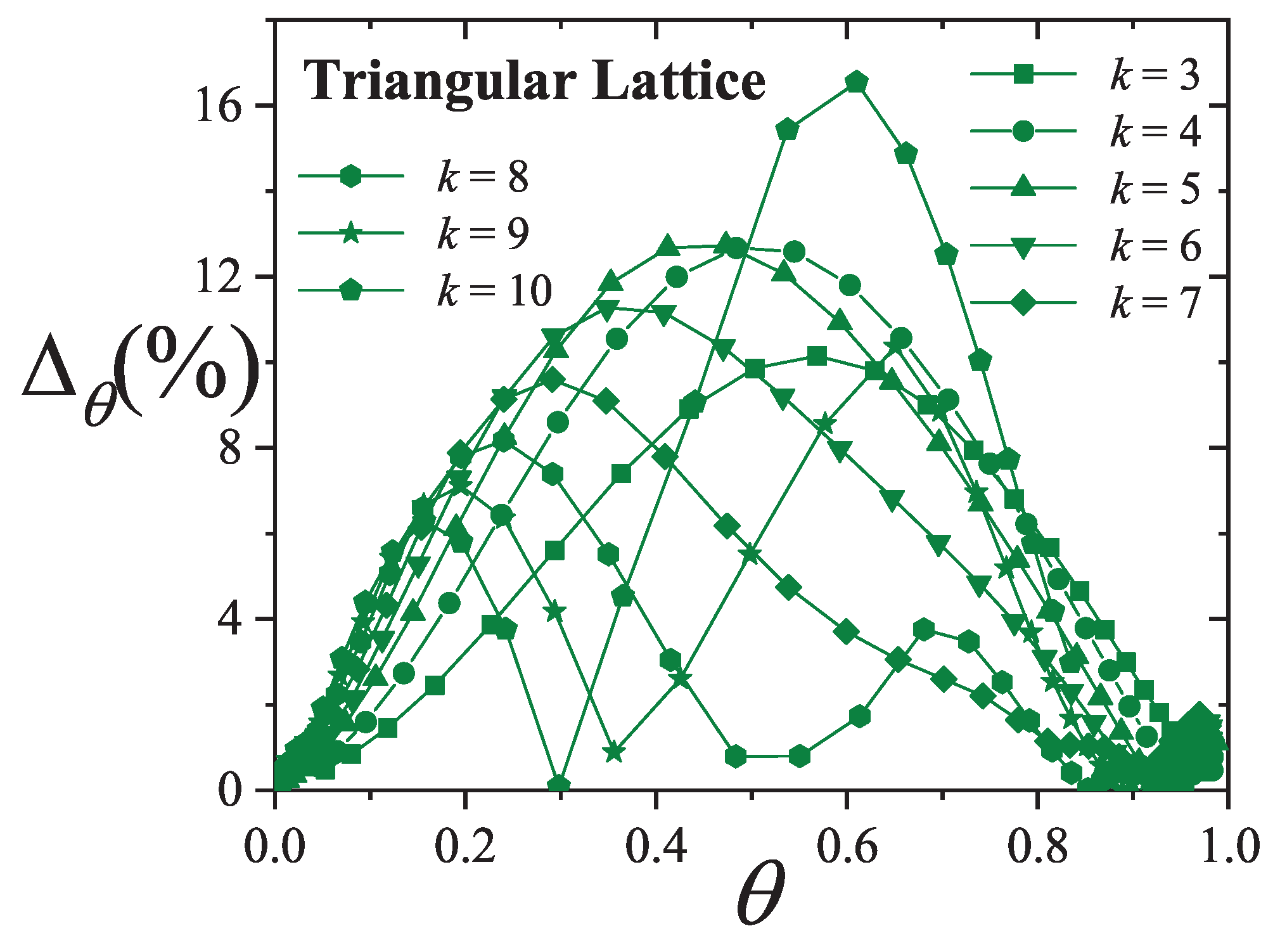

Figure 27(a) compare simulation isotherms with theoretical predictions for 6-mers on honeycomb, square, and triangular lattices, respectively. In all cases, the theoretical models agree well with simulations at low coverages, but deviate significantly as the surface coverage increases.

The discrepancies between simulation and theory can be quantified by the percentage reduced coverage, defined as [

73]

where

(

) represents the coverage obtained by using MC simulation (analytical approach). Each pair of values (

) is obtained at fixed

.

Figure 25b,

Figure 26b, and

Figure 27b show how

varies with surface coverage for the different lattice types. The performance of each theoretical model is as follows: the

model (dashed line) shows very good agreement with simulation results, with minimal discrepancies. Both the

(dash-dot-dot line) and

(dash-dot line) models tend to underestimate the coverage across the entire range. The

model (dotted line) performs poorly at intermediate coverages but improves at high coverages. With respect to lattice connectivity, the accuracy of

and

improves as

decreases, while the opposite trend is observed for

and

. The behavior of the

and

models supports the formulation of the semi-empirical (

) isotherm (solid line) given in Equation (

155). This trend is also illustrated in

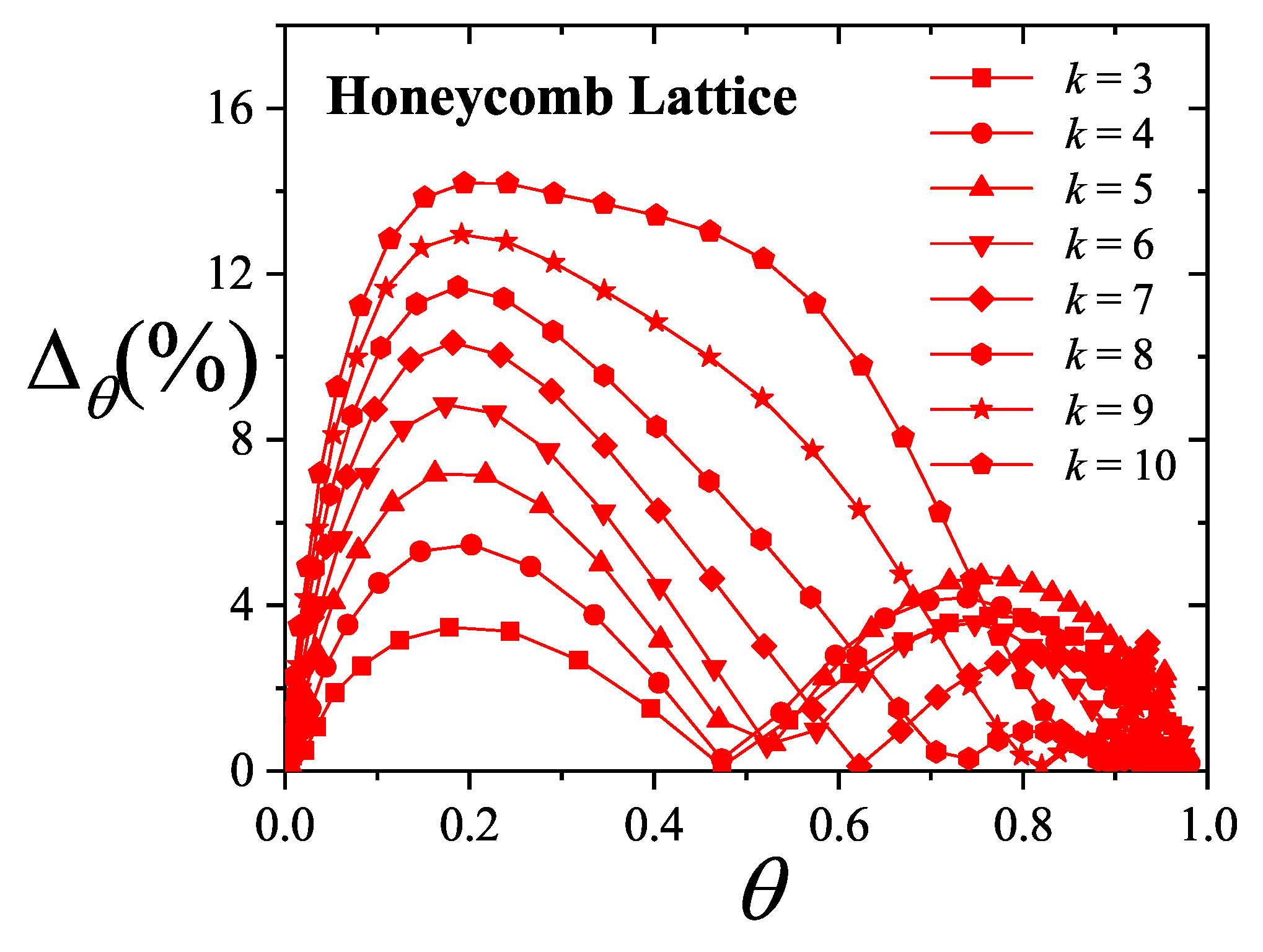

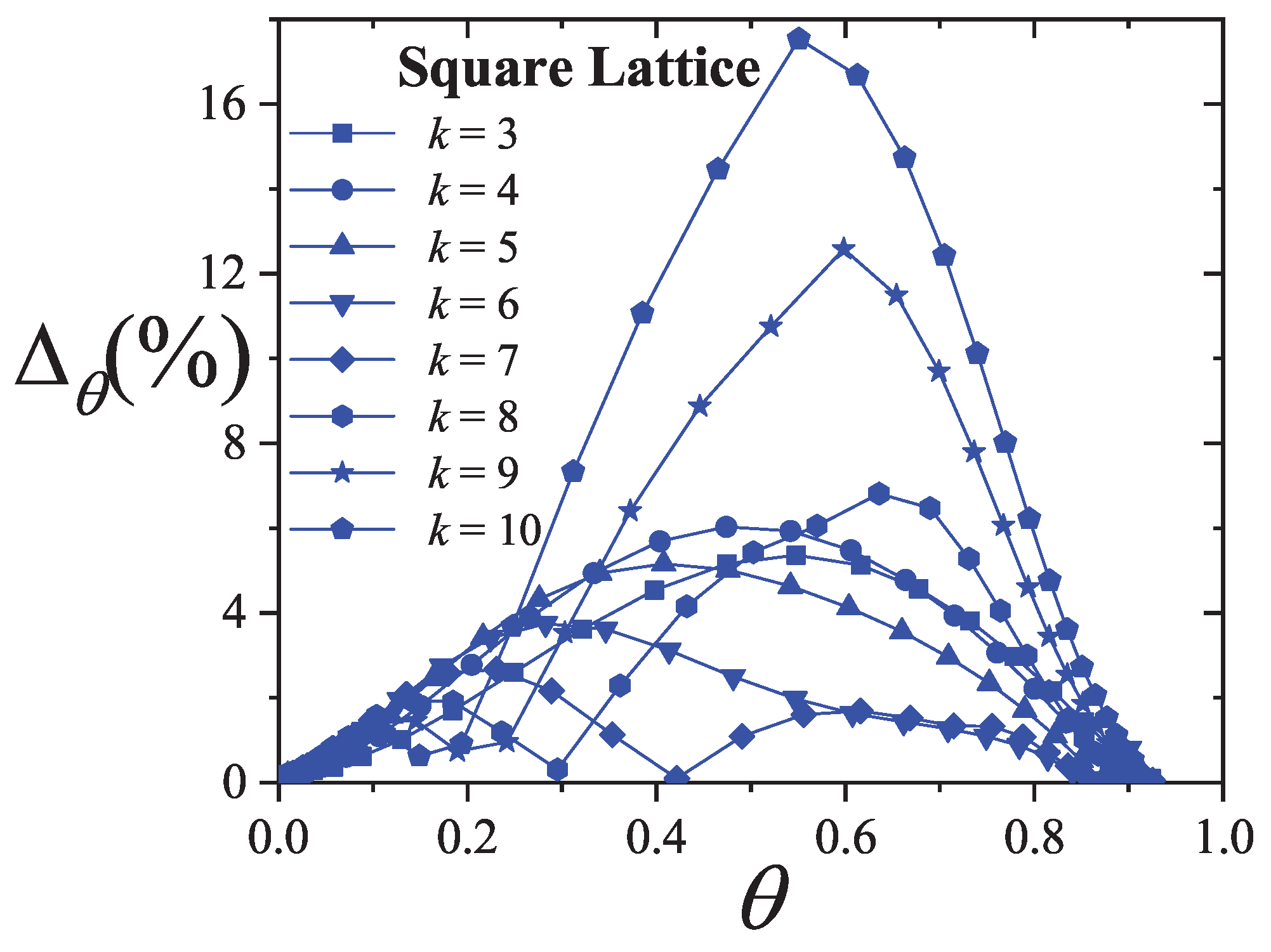

Figure 28,

Figure 29, and

Figure 30, which show the percentage reduced coverage for the

model as a function of concentration for various values of

and

k.

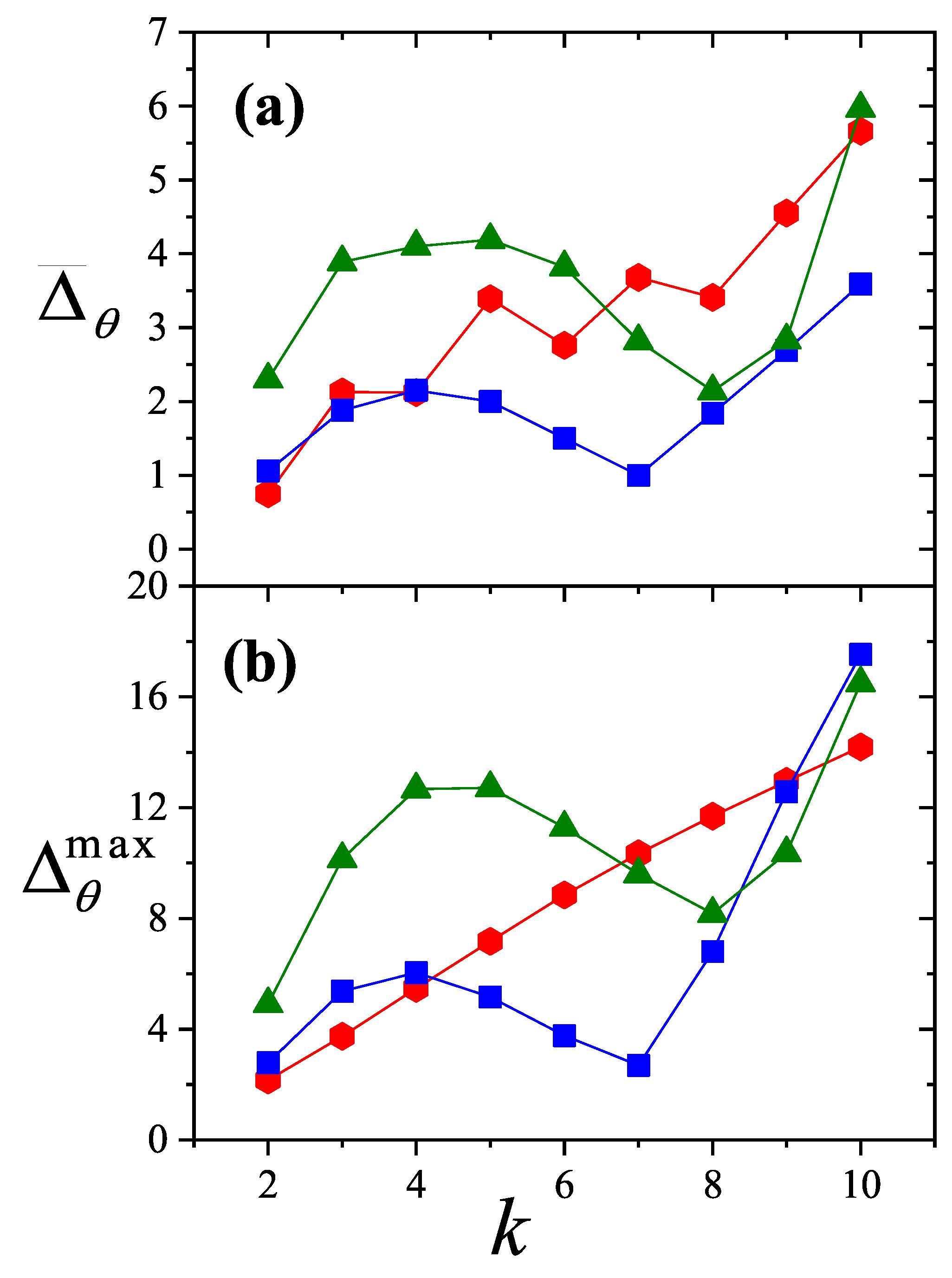

To better interpret the data shown in

Figure 28,

Figure 29 and

Figure 30, we consider two summary metrics: (1) the average absolute difference between simulation and theoretical coverage,

; and (2) the maximum value of the percentage reduced coverage,

. These metrics are presented in

Figure 31. Several conclusions can be drawn: (i) theoretical models generally perform better on square lattices; (ii) both

and

remain nearly constant for

k values between 2 and 8; and (iii) both quantities increase for

. Finally, since the values of

remain below

, the

model can be considered a reliable approximation for describing multisite occupancy adsorption, at least for the

k values analyzed here.

7.2. Two-Dimensional Adsorption of Binary Mixtures: Comparison Between Theory and Monte Carlo Simulations

In this section, we analyze the main characteristics of the theoretical approximations developed in

Section 3.3 in comparison with MC simulation results and experimental data.

We consider a gas mixture composed of rigid rods of lengths

k and

l, with each component present in equal molar fraction in the gas phase. Adsorption occurs on a regular, homogeneous lattice with connectivity

(square lattice) and 6 (triangular lattice). The parameters used in the HPTMC simulations (see

Section 8.3) were:

, and

MCSs. For simplicity, we assume the standard chemical potentials are zero and that the equilibrium constants

for all species.

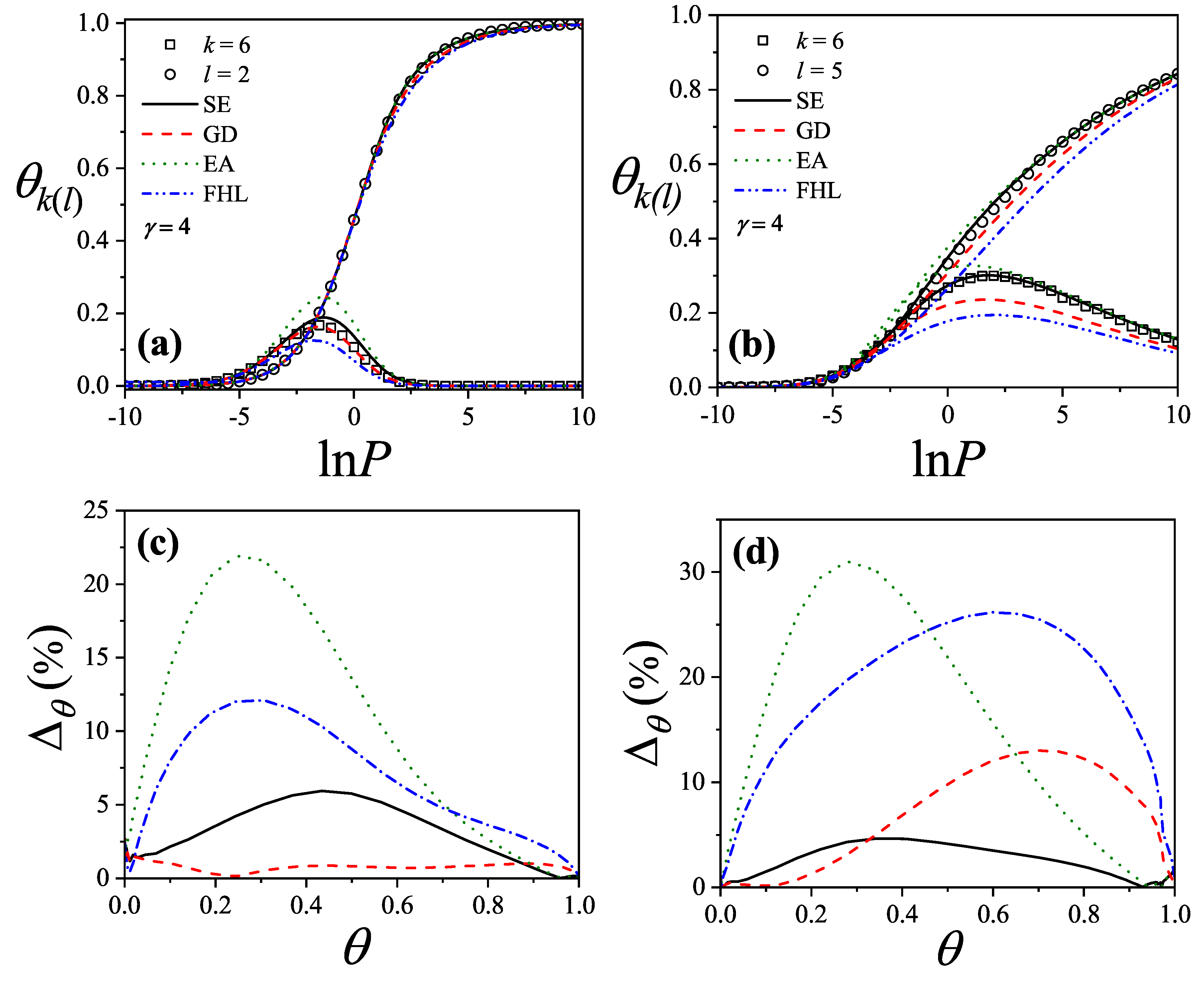

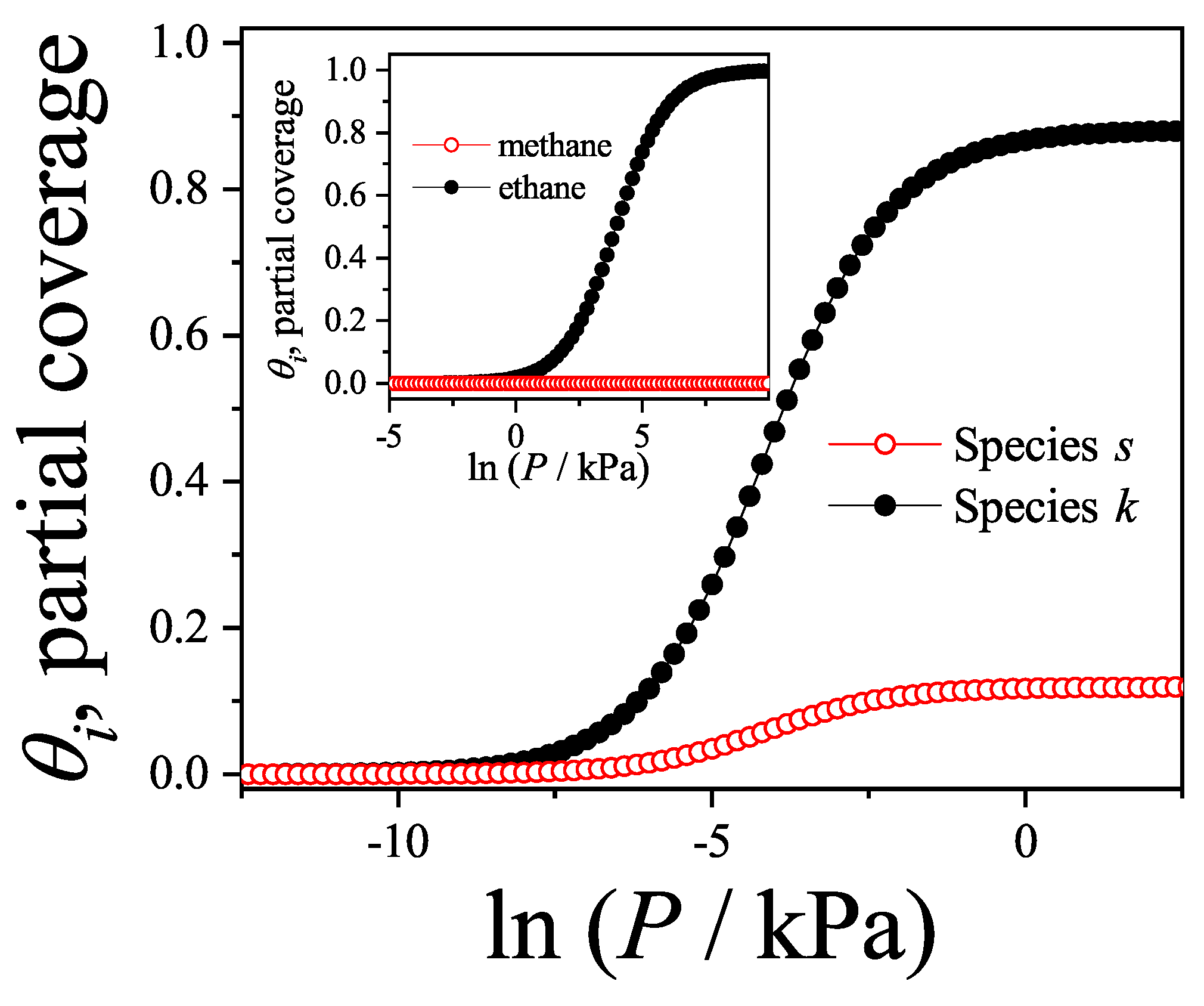

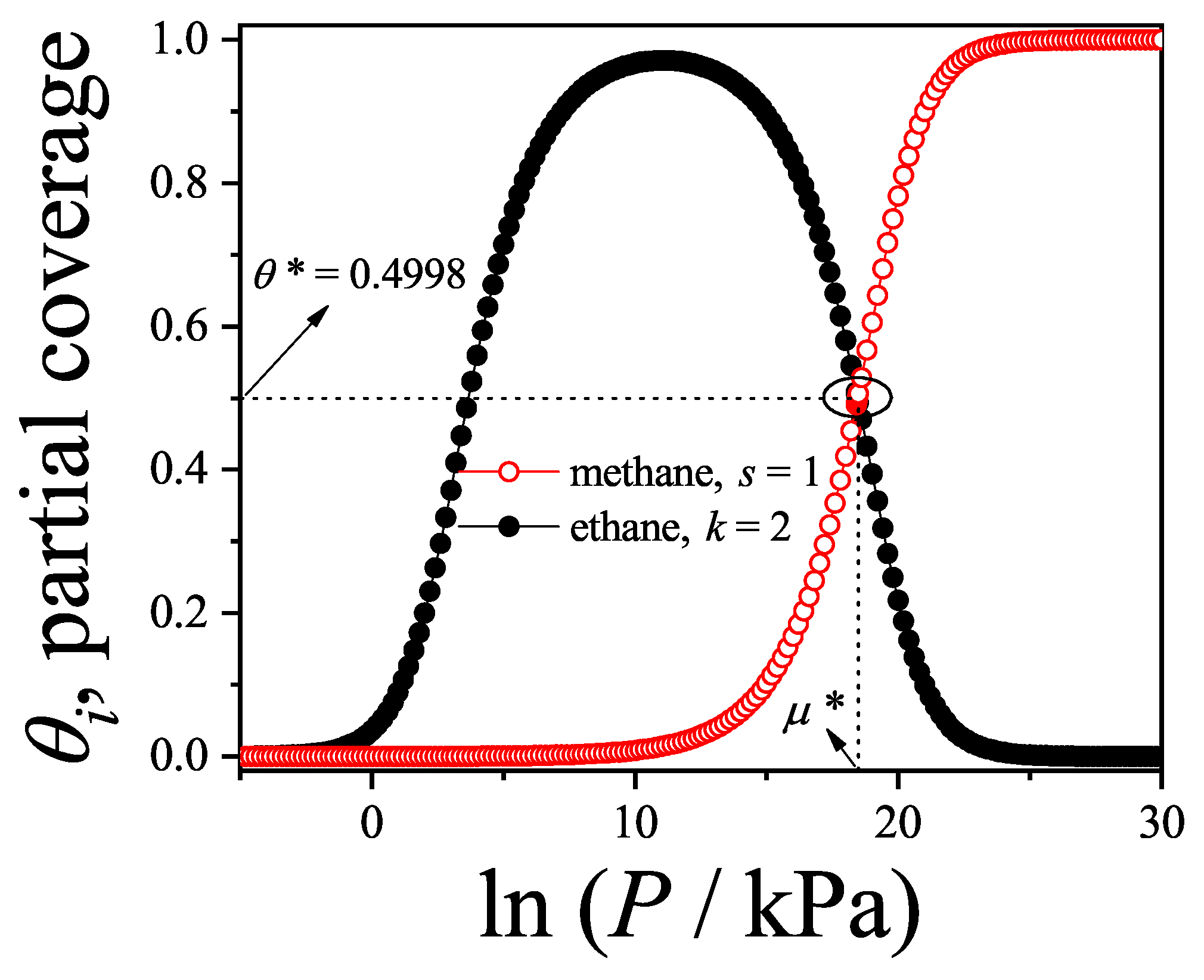

The partial adsorption isotherms for

,

, and two values of

are shown in

Figure 32(a) and

Figure 32(b), respectively. Symbols denote MC simulation data, while the lines represent various theoretical approaches as indicated.

A characteristic feature observed in binary mixtures of polyatomic species is evident in both figures: at higher pressures, the smaller species are displaced by the larger ones. This phenomenon, known as adsorption preference reversal (APR), arises from entropic competition between adsorbed species. A detailed investigation of the APR effect, focusing on the impact of molecular size difference, is presented in

Section 7.4.

In

Figure 32(a), the most significant discrepancies between simulation and theoretical predictions occur in the partial adsorption isotherm of the larger species. As clearly shown in

Figure 32(b), the magnitude of these deviations depends on the level of approximation used in evaluating

[

11].

To quantitatively assess the agreement between simulation and analytical results, we use the reduced coverage error defined in previous section [

73],

where

represents the value of the total coverage obtained by using the MC simulation (analytical approach). Each pair (

,

) corresponds to the same value of pressure

P.

The results obtained from Equation (

332) are shown in

Figure 32c,d. In

Figure 32c, better agreement is observed at surface coverage above

, where only dimers are present, a case where all theoretical models perform well [

16]. Conversely, for larger adsorbates, classical approaches fail to accurately describe the adsorption behavior across the entire range of coverage, as illustrated in

Figure 32d. In contrast, the

approximation yields satisfactory results, with errors remaining below

in both cases.

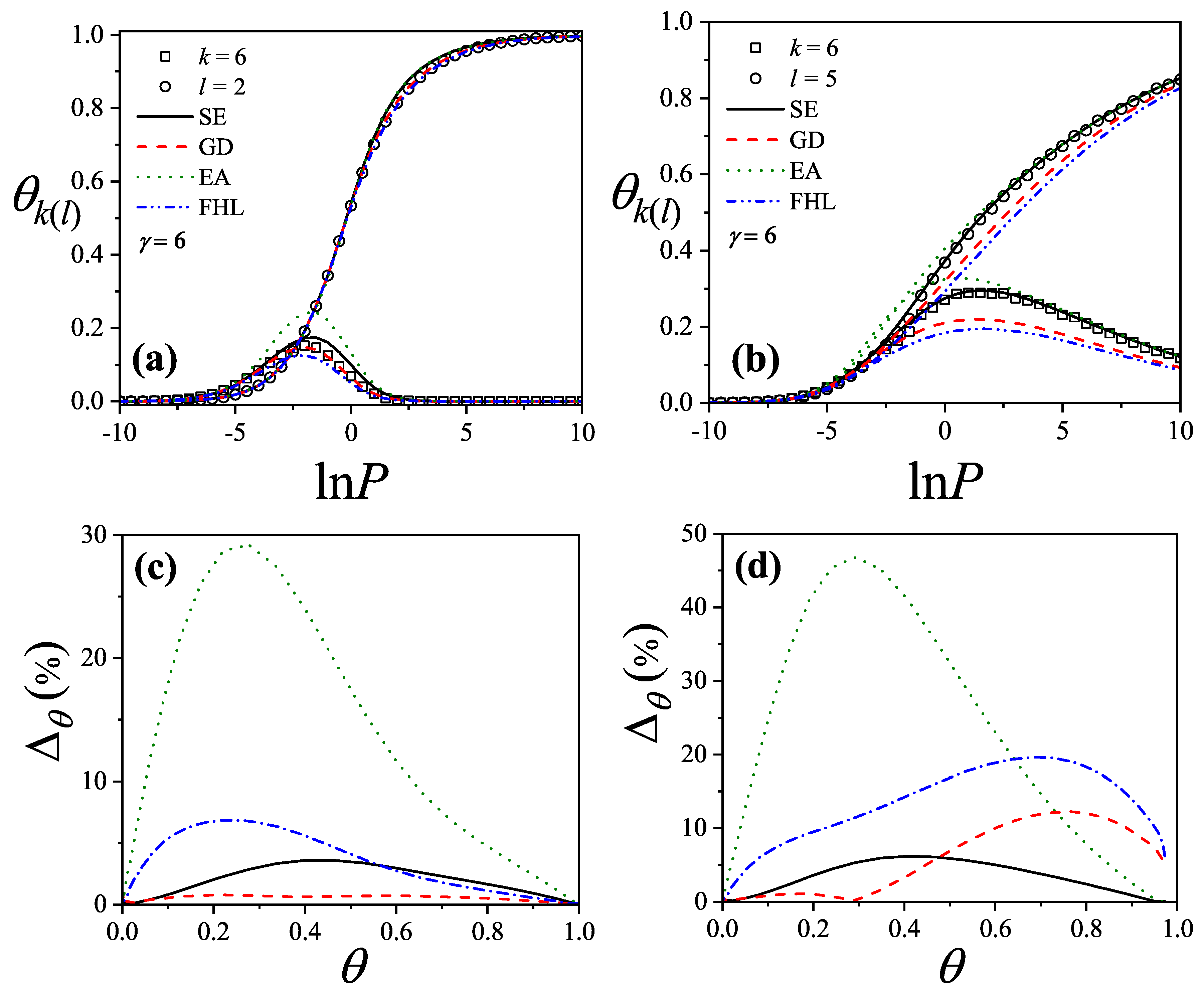

The same analysis presented in

Figure 32 is repeated for triangular lattices, with the corresponding results shown in

Figure 33. In most cases, the error increases with lattice connectivity. However, the

approximation consistently yields an error below

, indicating that it is a highly reliable method for modeling binary mixture adsorption with multisite occupancy, at least for the molecular sizes considered in this study.

To complete our analysis, we examine partial isotherms for mixtures with varying sizes of

l, keeping

fixed. For each pair (

k,

l), the discrepancies between theoretical predictions and simulation results are assessed using the average error across the full coverage range, defined as

where

R is the total number of isotherm points (or the number of replicas, as described in

Section 8.3).

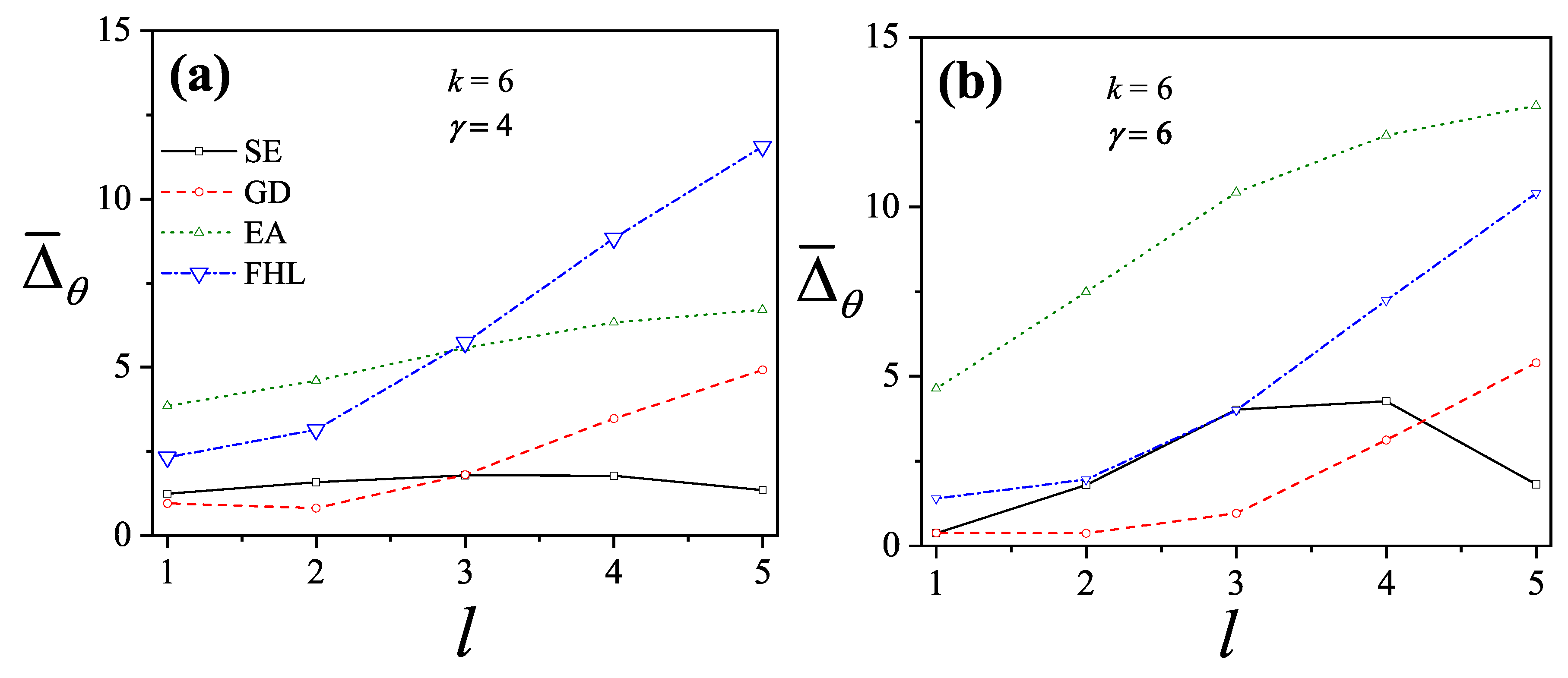

Figure 34 illustrates the dependence of

on the size of the

l-mers and the lattice geometry for the various theoretical approaches evaluated in this work. As shown,

increases monotonically with

l, indicating that the divergence between MC simulations and analytical models becomes more significant for larger adsorbates. In contrast, the error associated with the

approximation remains nearly constant, around

for square lattices and

for triangular lattices. This excellent agreement across all values of

l highlights the robustness of the

method and underscores the importance of accurately computing the correction function [Equation (

187)] for understanding the adsorption behavior of rigid rod mixtures.

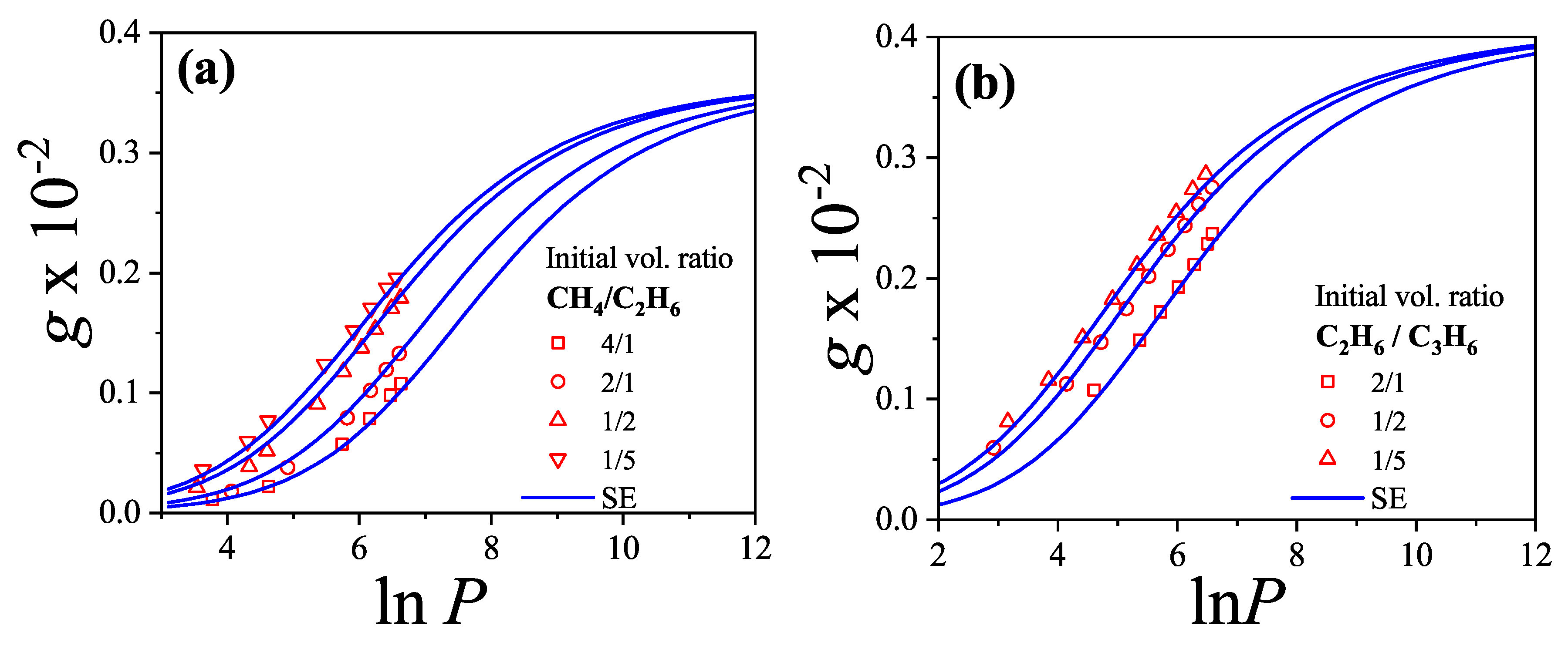

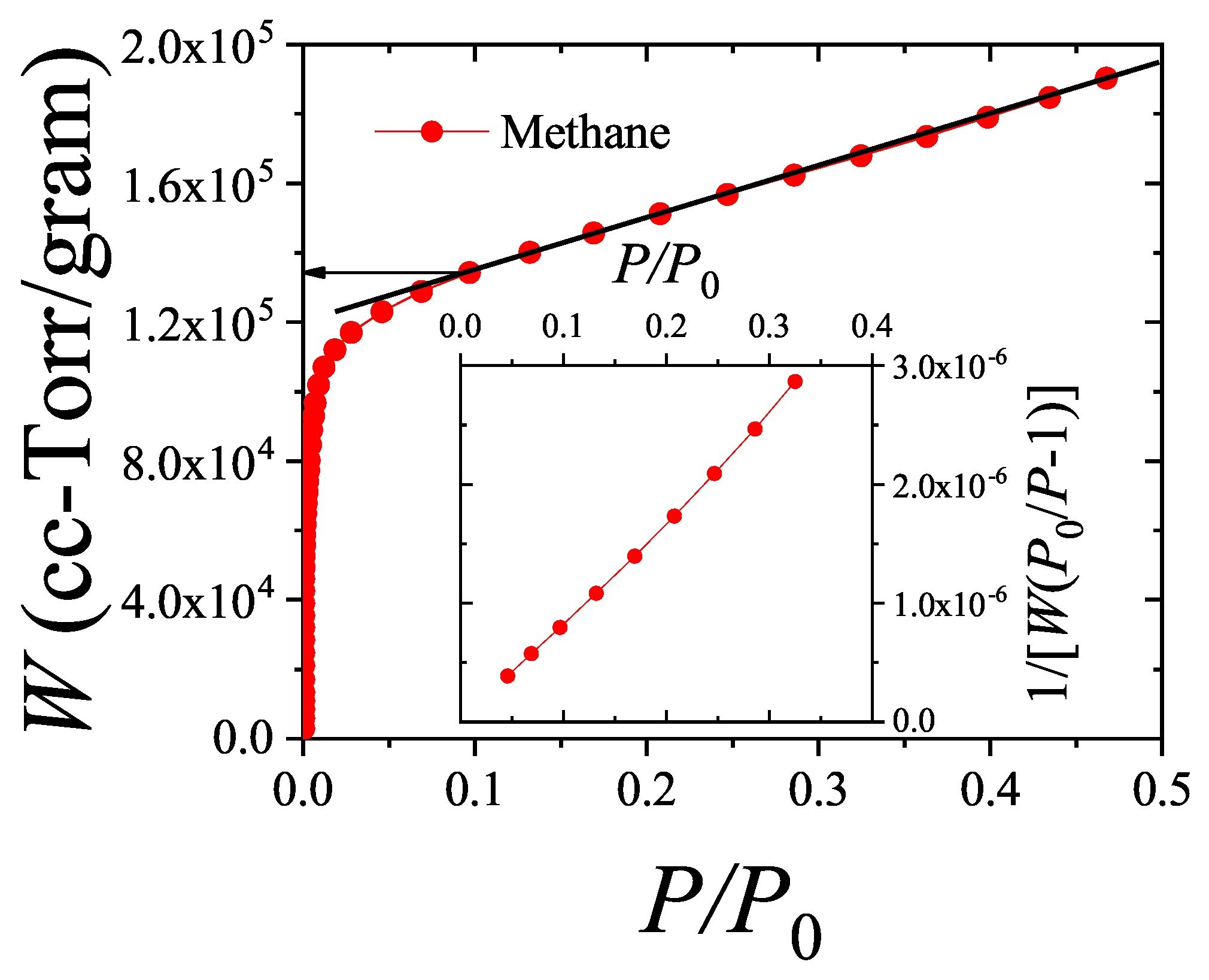

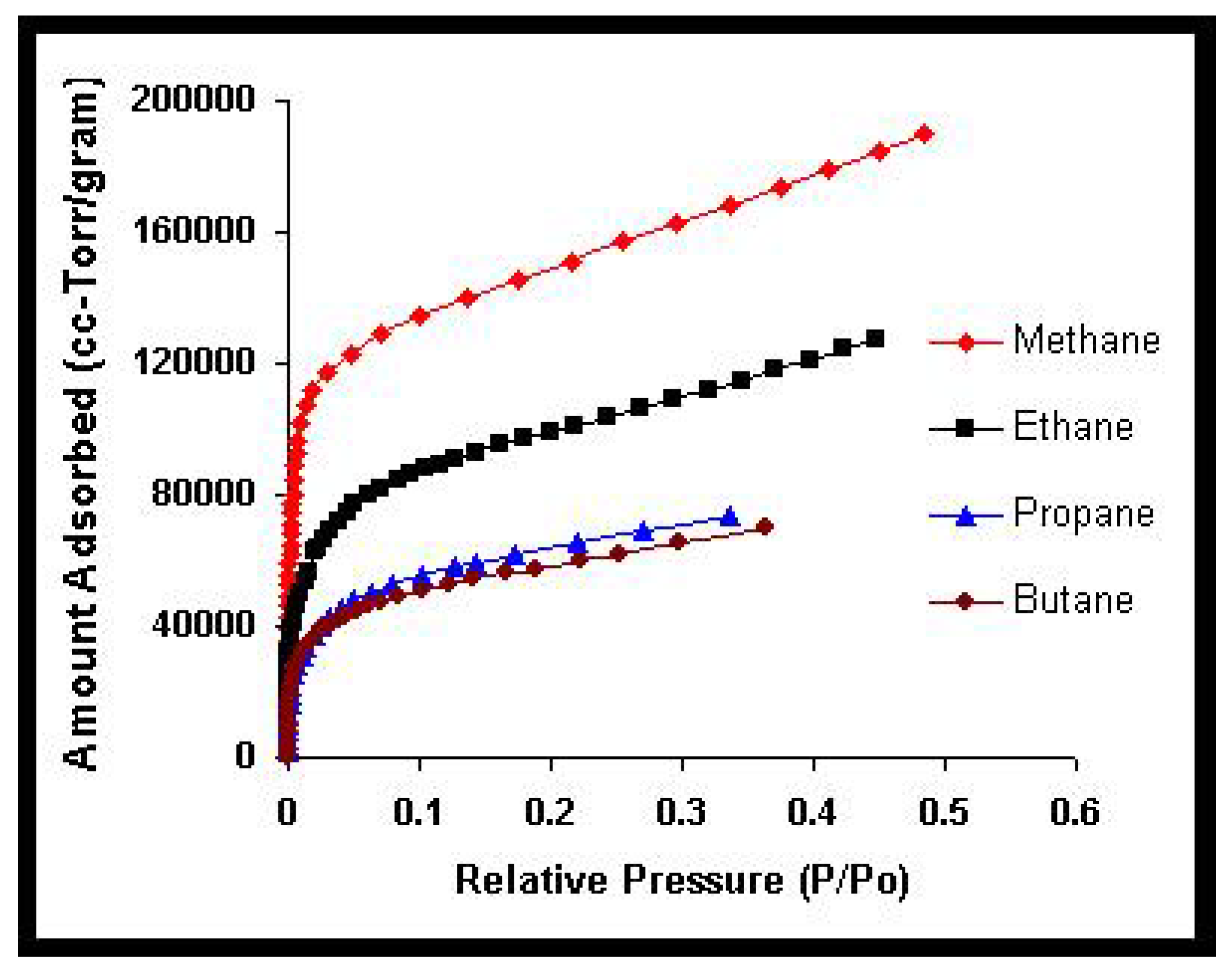

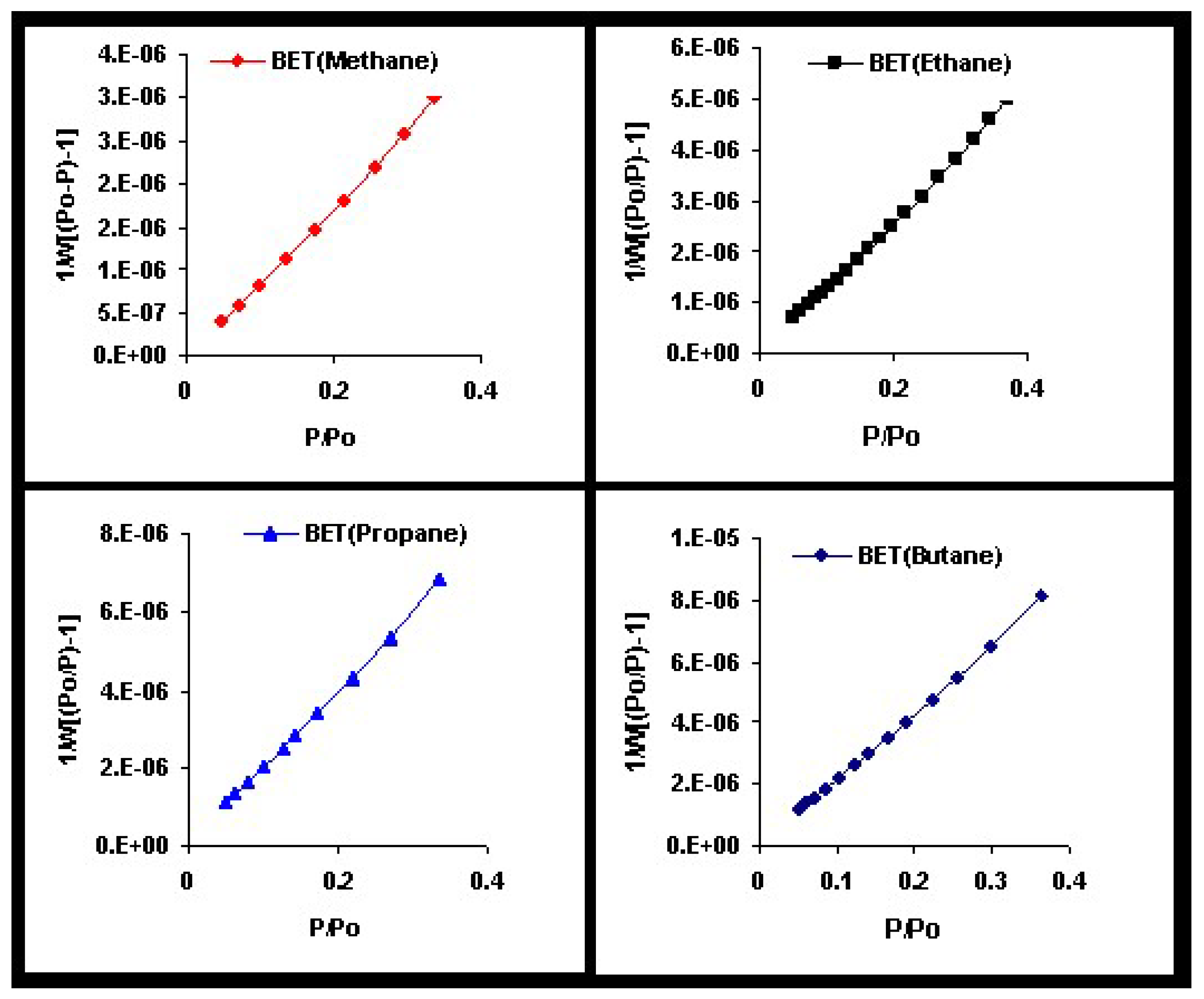

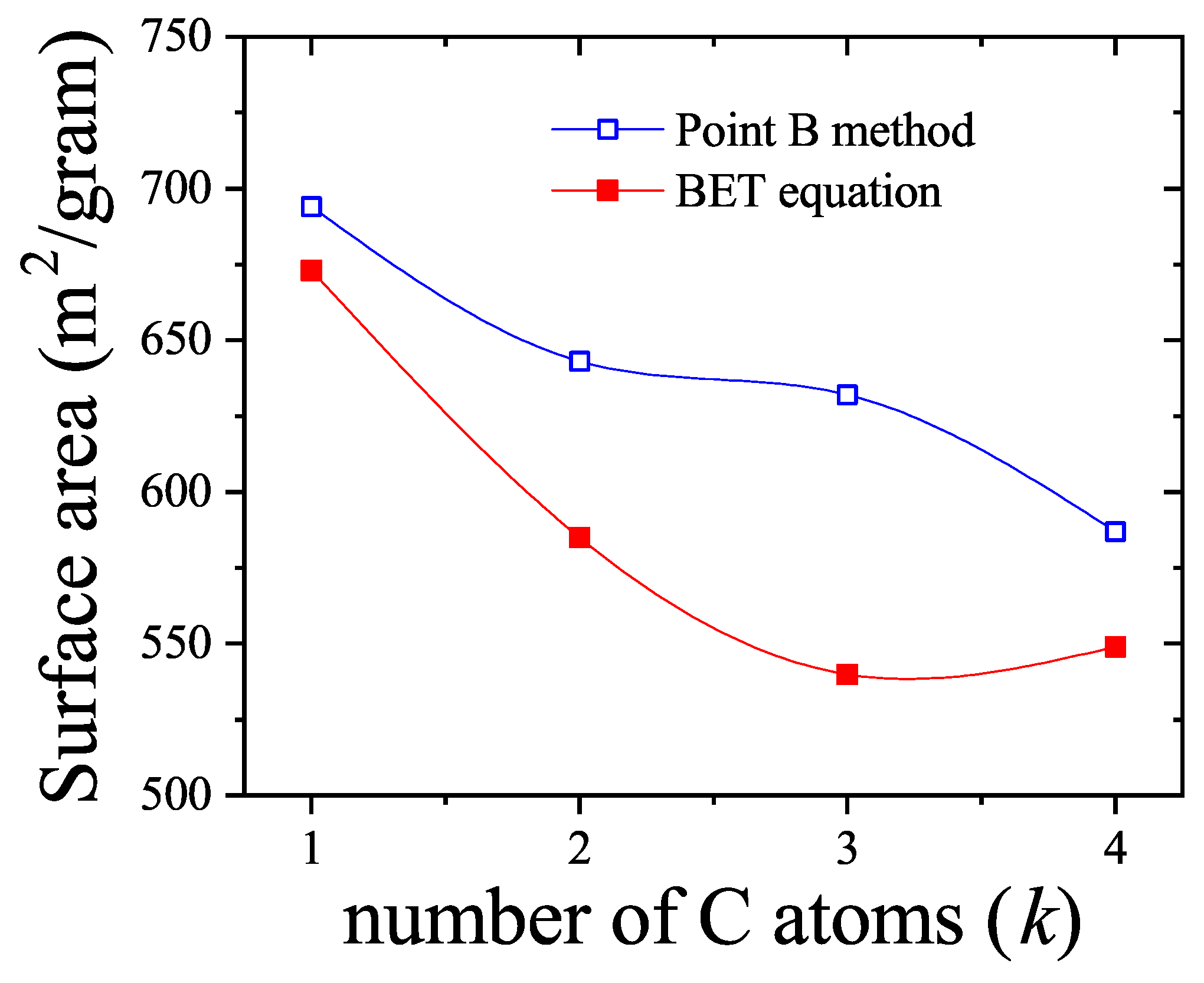

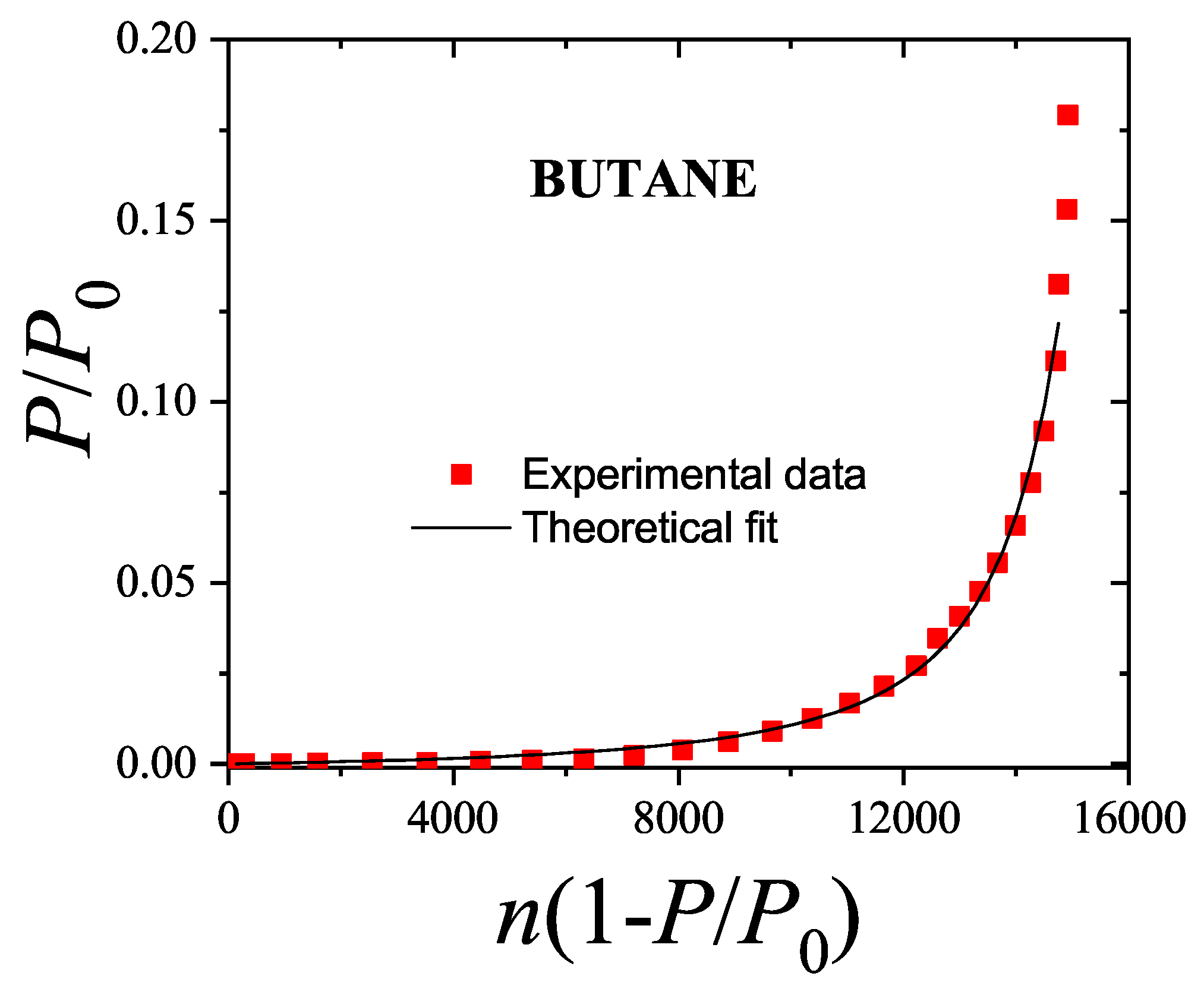

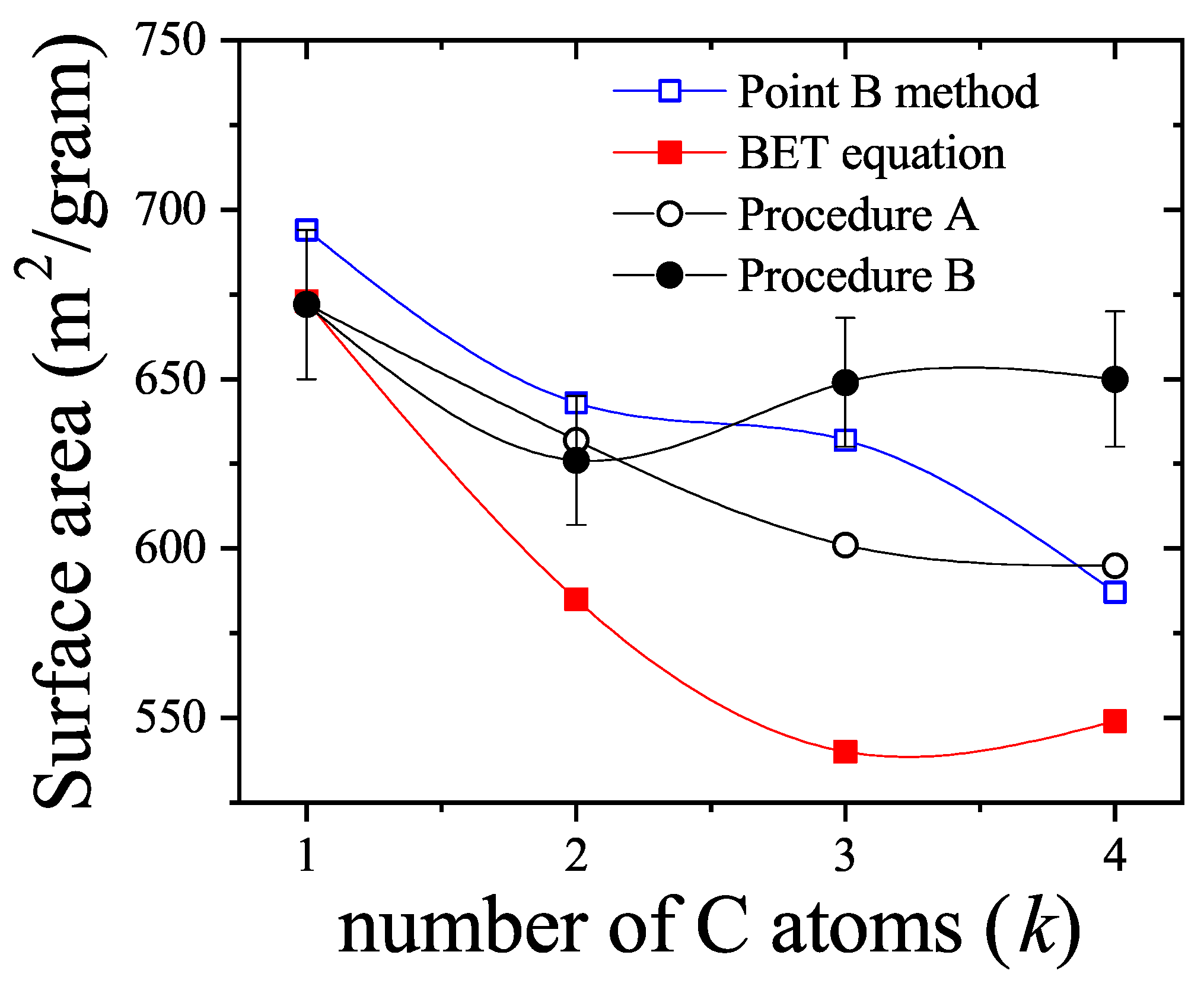

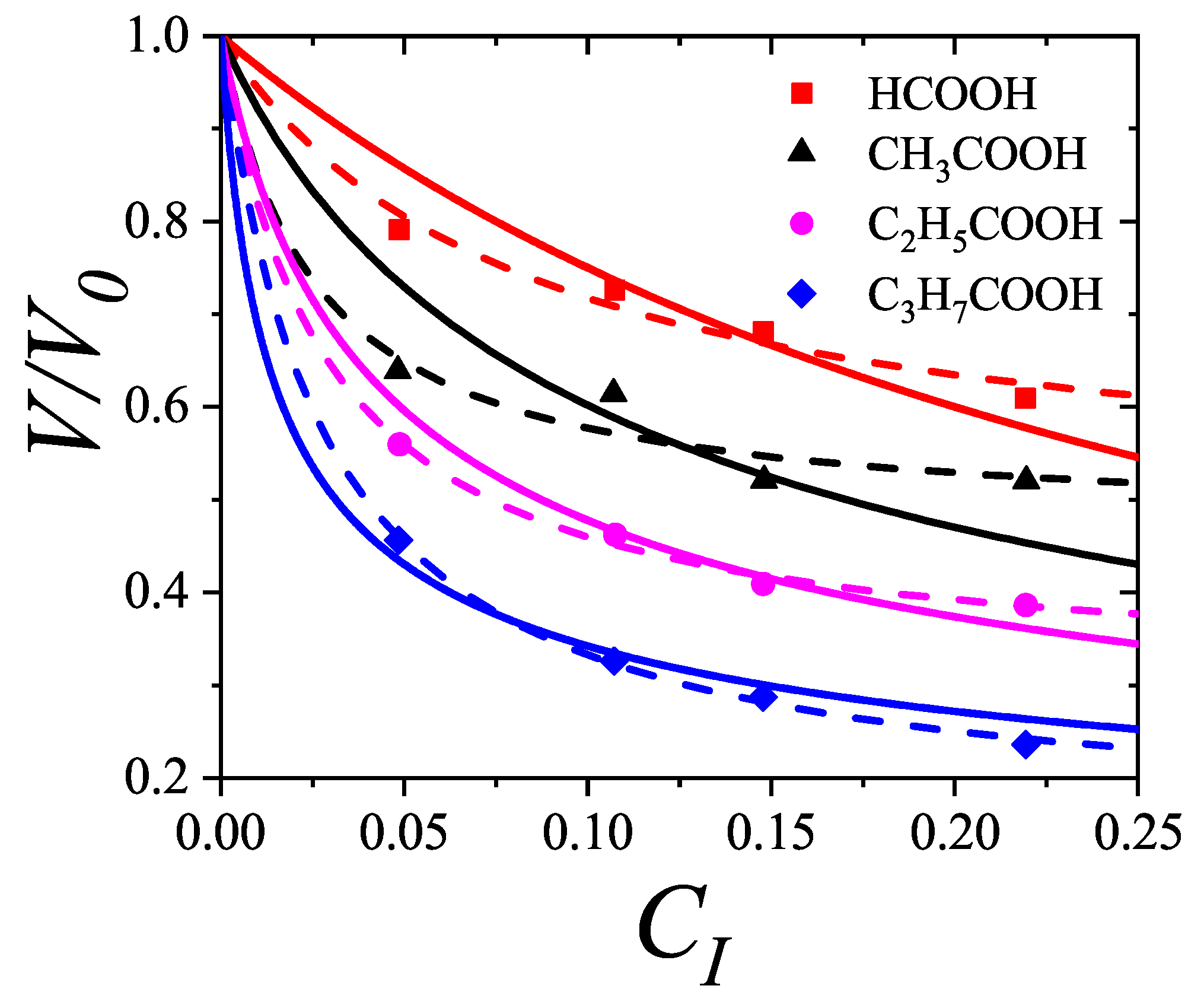

Finally, to evaluate the applicability of the proposed model, we analyzed experimental data extracted from Ref. [

116]. Specifically, adsorption isotherms of hydrocarbon mixtures—methane–ethane and ethane–propylene—on activated carbon (AC-40) at

C were examined using the

adsorption model introduced in this work. Since the experimental data were reported as adsorbed amount (in

) versus pressure (in mmHg), the theoretical isotherms were reformulated in terms of pressure

P and adsorbed amount

g to enable direct comparison and fitting.

Assuming equilibrium between the adsorbed phase and an ideal gas-phase mixture, the chemical potentials were related to the system pressure and molar fractions. Additionally, the coverage was defined as , where represents the maximum adsorption capacity of the surface.

Following a common approach in the literature, a “bead segment” chain model was employed in which each CH

n group (bead) occupies one adsorption site on the surface. Accordingly, each hydrocarbon species C

m was modeled as a rigid rod of length

[

117].

Within this framework, the experimental isotherms for methane–ethane and ethane–propylene mixtures at

C and varying molar fractions were fitted using a single value of

and temperature-dependent equilibrium constants

as adjustable parameters. The results of the fitting procedure are shown in

Figure 35, and the corresponding parameter values are summarized in

Table 1. A very good agreement is observed between experimental data (symbols) and theoretical predictions (solid lines).

While a more extensive analysis of experimental adsorption isotherms is still needed, these results suggest that the theory provides a promising and accurate framework for describing the adsorption thermodynamics of interacting polyatomic species.

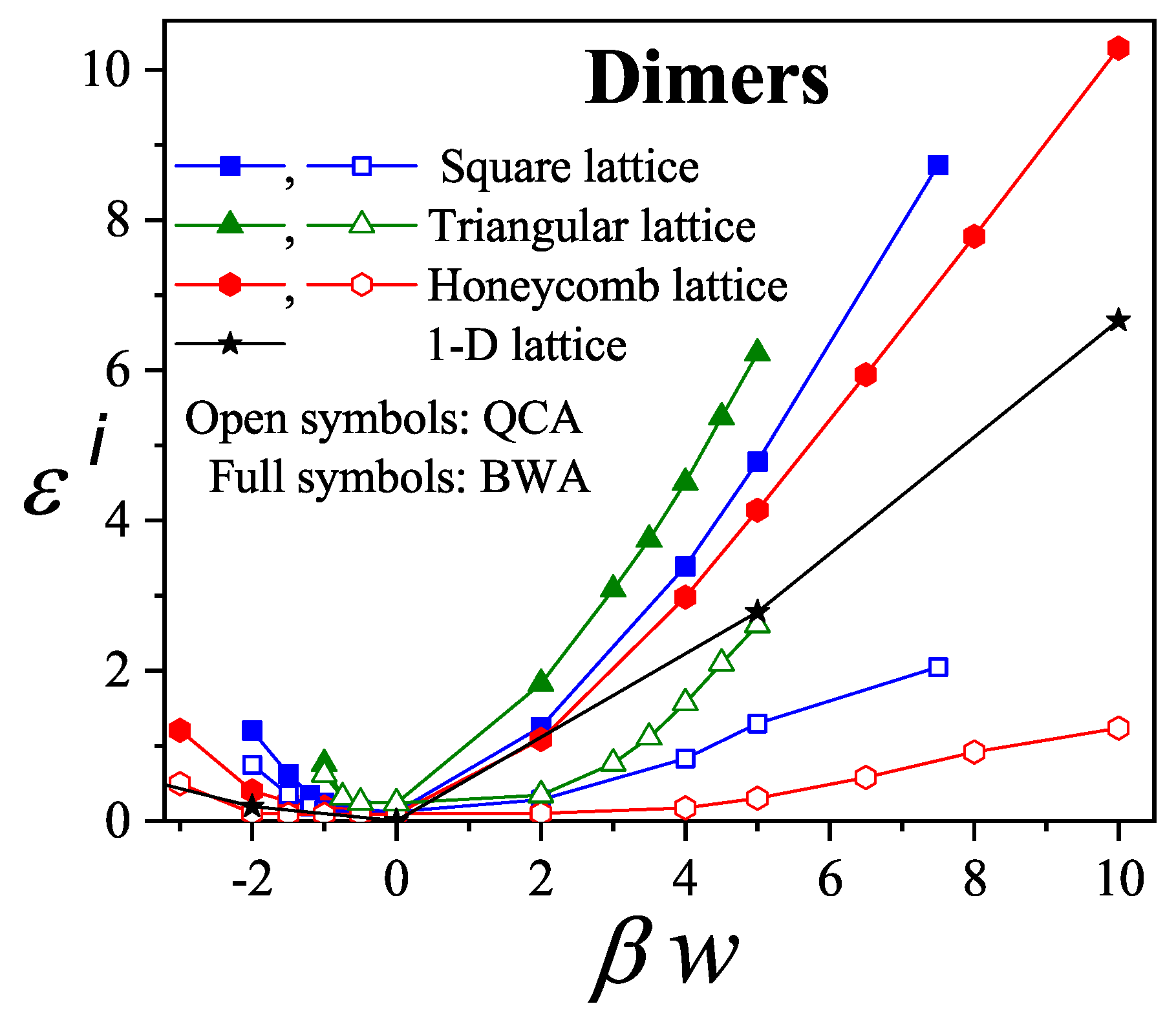

7.3. Two-Dimensional Adsorption of Interacting k-Mers: Comparison Between Theory and Monte Carlo Simulations

In this section, we analyze the main features of the thermodynamic functions derived from the models presented in

Section 4.1 (Bragg-Williams Approximation,

) and

Section 4.2 (Quasi-Chemical Approximation,

), in comparison with Monte Carlo simulation results for a lattice-gas of interacting dimers on honeycomb, square, and triangular lattices.

15

As in

Section 7.1, simulations were conducted on honeycomb, square, and triangular lattices of size

, with

, 144, and 150, respectively, using periodic boundary conditions. Moreover, the lattice size

L was carefully selected to avoid perturbation of the adlayer structure.

Representative adsorption isotherms obtained from Monte Carlo simulations in the grand canonical ensemble (symbols), along with their comparison to the

(solid lines) and

(dashed lines), are shown in

Figure 36,

Figure 37, and

Figure 38 for honeycomb, square, and triangular lattices, respectively.

For attractive interactions [

Figure 36a,

Figure 37a, and

Figure 38a], as temperature decreases, a first-order phase transition occurs, evidenced by the discontinuity in the simulated isotherms and the appearance of characteristic loops in the theoretical curves. This behavior, experimentally observed in many systems [

80], corresponds to a low-coverage lattice-gas phase coexisting with a higher-coverage “lattice-fluid” phase. The lattice-fluid can be considered as a diluted version of the registered

phase where all lattice sites are occupied except for some vacancies.

This two-dimensional gas-to-liquid condensation closely resembles that of a monomeric lattice gas with attractive interactions. However, for k-mers, the particle-vacancy symmetry (valid for monomers) is broken, resulting in adsorption isotherms that are asymmetric with respect to .

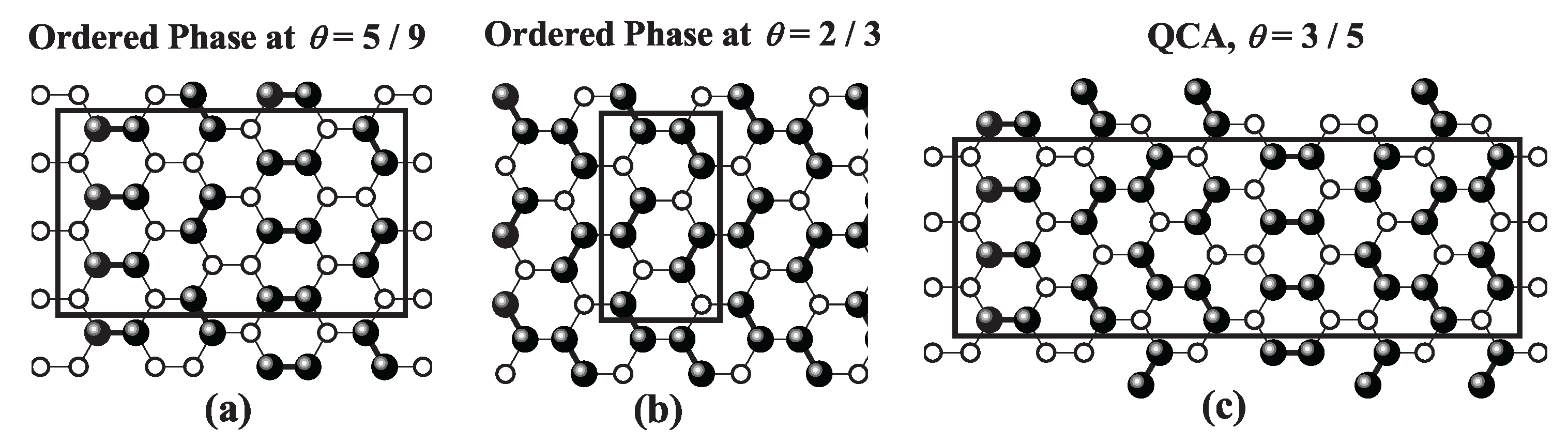

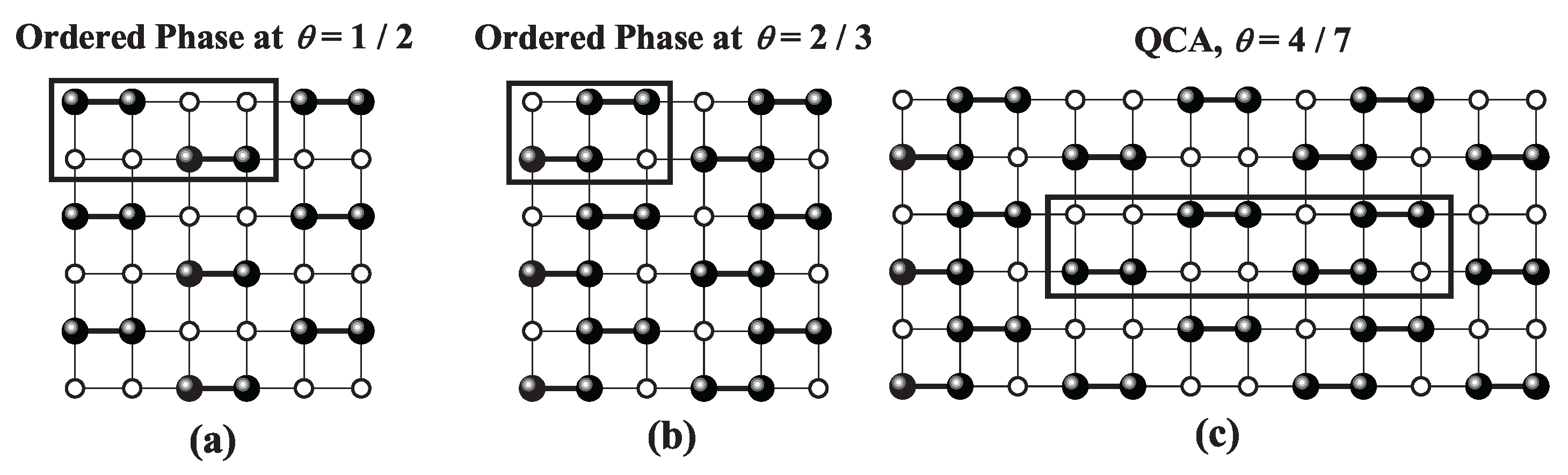

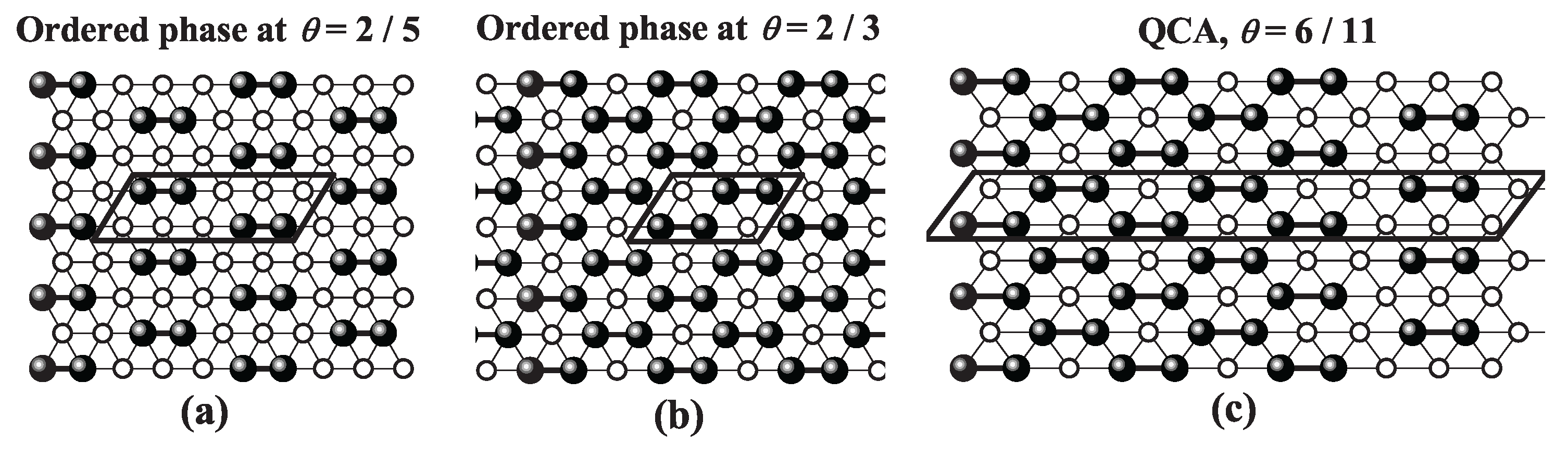

In the case of repulsive interactions [

Figure 36b,

Figure 37b, and

Figure 38b], the isotherms exhibit more complex features due to the formation of ordered structures in the adsorbed layer. These ordered arrangements are indicative of subcritical behavior, where continuous phase transitions occur from disordered to ordered phases [

118,

119]. At high temperatures, isotherms remain featureless, but at low temperatures, they display distinct steps corresponding to the emergence of ordered phases. The specific form of these steps depends strongly on the lattice connectivity. As the chemical potential

increases and the surface coverage

spans from 0 to 1, two ordered phases are typically observed: (1) a low-coverage ordered phase (LCOP), characterized by site occupancies of

,

, and

for honeycomb, square, and triangular lattices, respectively; and (2) a high-coverage ordered phase (HCOP), with

site occupancy across all three geometries. Snapshots of the LCOP [part a)] and HCOP [part b)] configurations for each lattice type are presented in

Figure 39,

Figure 40, and

Figure 41. For a detailed discussion of these phases, refer to Refs. [

118,

119].

Under attractive interactions, both theoretical models yield qualitatively similar results, and the isotherms from

and

are nearly indistinguishable. However, it is known that isotherms derived from fundamentally different approximations can appear deceptively similar [

67]. To better assess the accuracy of each model, we use the absolute error in the chemical potential,

, which is defined as

where

(

) represents the chemical potential obtained by using MC simulation (analytical approach). Each pair of values (

,

) is obtained at fixed

.

As an example,

Figure 42(a) presents

for three representative attractive interaction strengths: squares for

, triangles for

, and circles for

. Solid and open symbols correspond to

and

results, respectively. In all cases,

outperforms

.

The corresponding analysis for repulsive interactions is shown in

Figure 42b, which includes

(squares),

(triangles), and

(circles). Again, solid and open symbols represent

and

, respectively. Here, differences between the two models are both quantitative and qualitative. While

fails to predict any ordered structures,

captures the formation of a pronounced plateau at low temperature. This critical coverage,

, appearing between the LCOP and HCOP, depends on both lattice geometry and adsorbate size. The adsorbate configuration at

can be interpreted as a mixture of LCOP and HCOP phases [see part (c) in

Figure 39,

Figure 40, and

Figure 41].

The curves in

Figure 42 correspond to a honeycomb lattice. However, the behavior of

for square and triangular lattices is very similar (data are not shown here for sake of simplicity).

To quantify the overall deviation between theory and simulation across the full coverage range, we define the integral error

as:

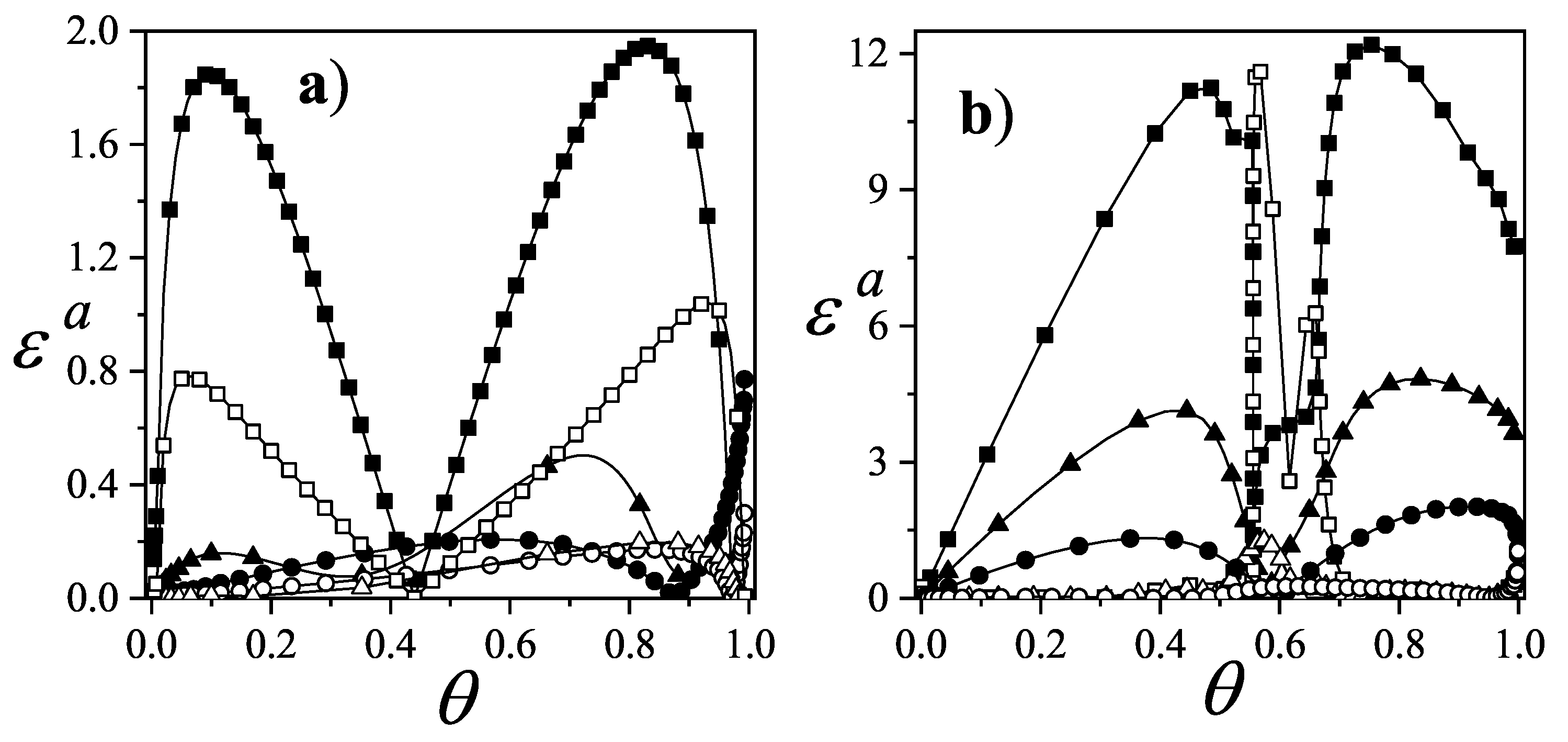

Figure 43 shows

for all lattice geometries and a broad range of

values. Several key conclusions can be drawn:

In all cases,

provides a significantly better fit to the simulation data than

. This is particularly true for repulsive interactions, where

shows large discrepancies, while

remains the simplest yet effective model for describing multisite occupancy adsorption.

The value of

increases with lattice connectivity. This may be attributed to a loss in accuracy of

as

increases [

73].

There exists a broad range of interaction strengths (

) for which

matches the simulation data extremely well. Notably, most surface science experiments fall within this range of interaction energies.

Therefore, not only represents a clear improvement over the in modeling k-mer adsorption but also provides a solid theoretical framework and compact expressions for the interpretation of thermodynamic adsorption data of polyatomic species—such as alkanes, alkenes, and other hydrocarbons—on regular surfaces.

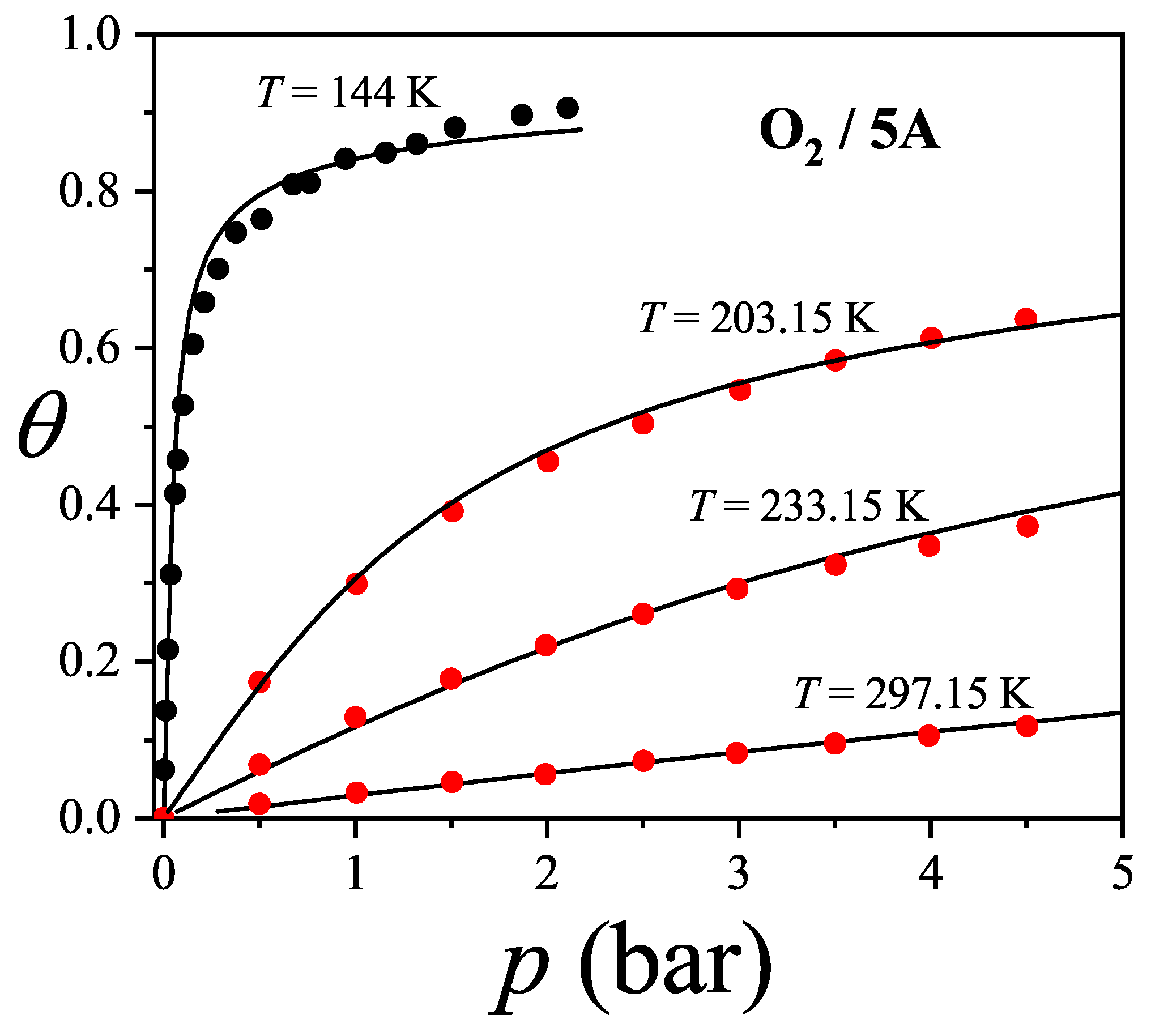

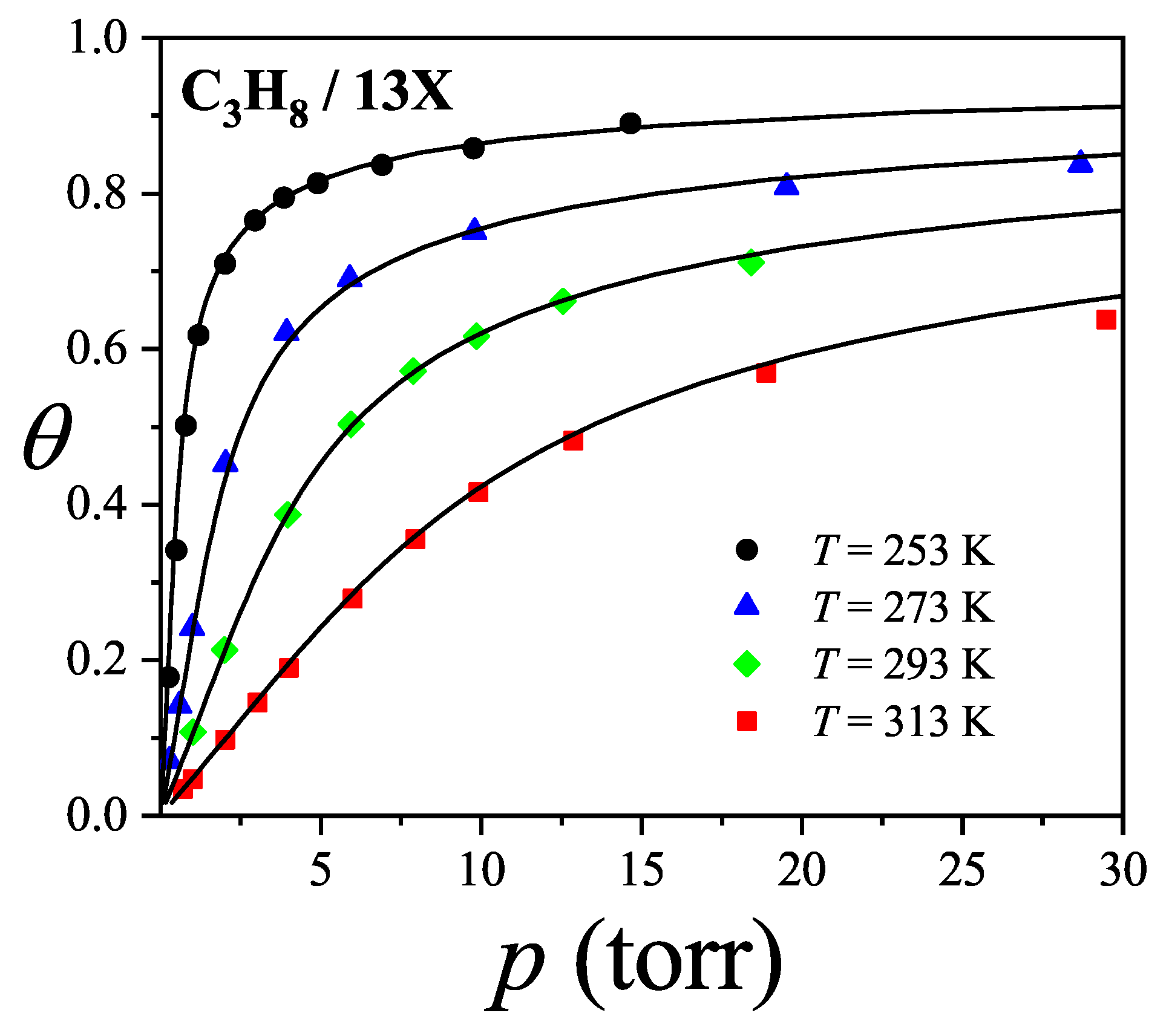

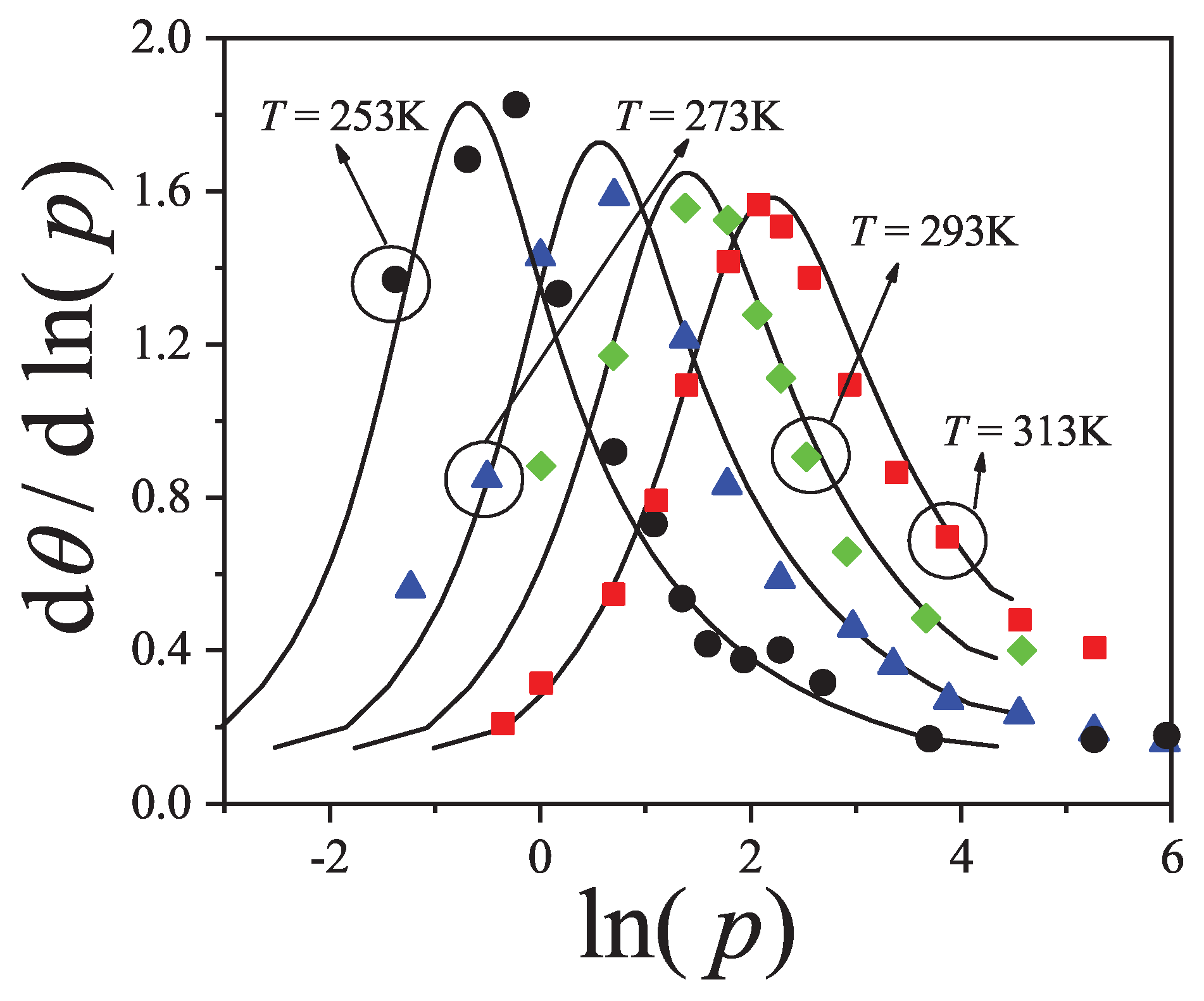

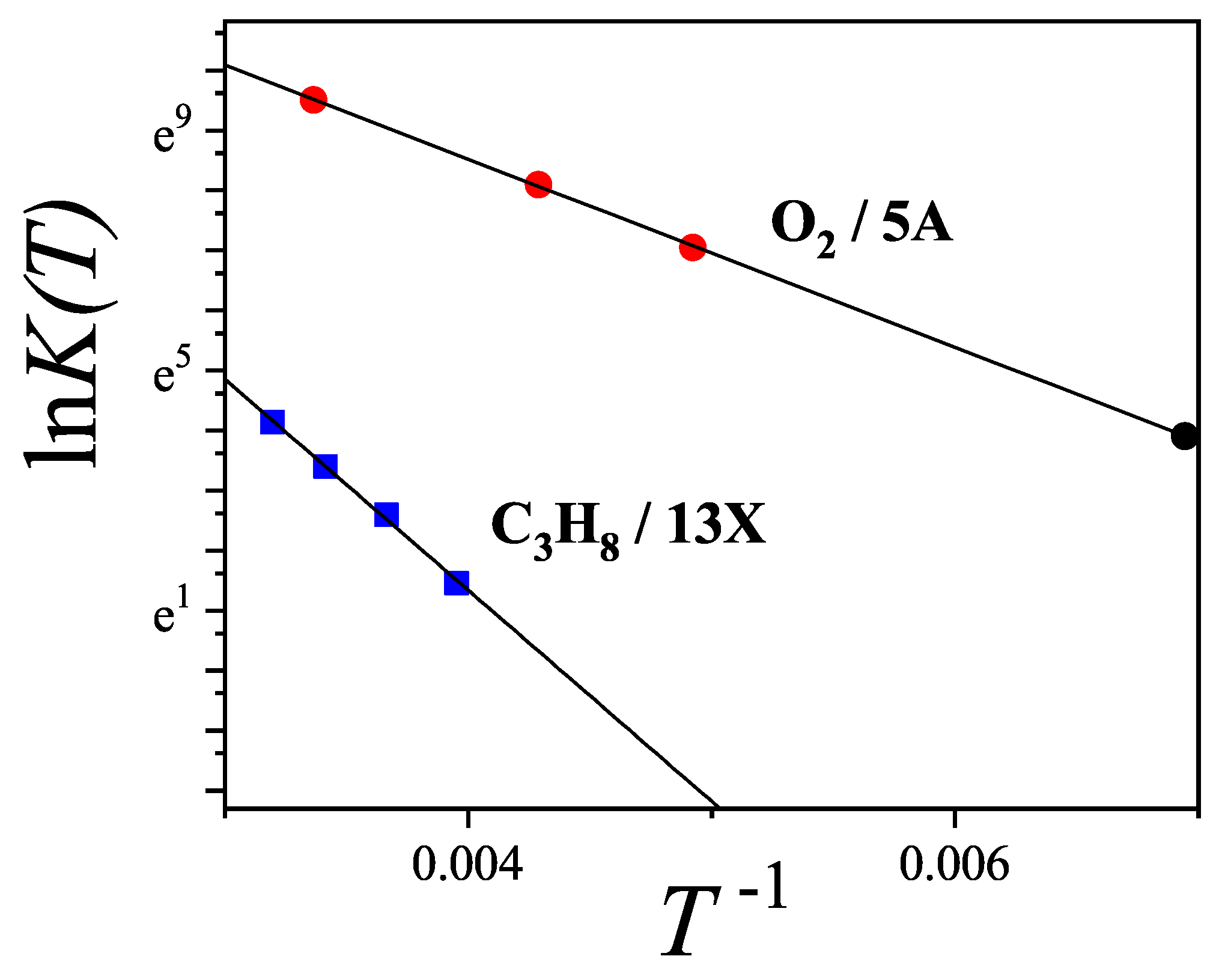

7.4. Application of to the Adsorption of and in Zeolites 13X and 5A: Determination of the Adsorption Configuration

One interesting application of the theoretical framework presented in

Section 3.2.2 on a lattice gas model involves the interpretation of experimental adsorption isotherms for propane [

120] and oxygen [

121,

122] in 13X and 5A zeolites, as well as in simulation-based systems. In our approach, we employed Equation (

125) under two main assumptions:

since

constant, if a single molecule has

m distinct ways to adsorb per lattice site at zero coverage, then the presence of an adsorbed

k-mer, occupying

sites, effectively excludes

states from being accessible to other molecules [thus,

]; and

the energetic contribution from adsorbate-adsorbate interactions is accounted for using a mean-field approximation, as described in

Section 4.1. This analysis highlights the physical interpretation of the parameters

g and

a, linking them to the spatial configuration of adsorbed molecules and the geometric structure of the surface.

Because the experimental data are presented as adsorbed volume

v, against pressure

p, we rewrite Equation (

125) in the more convenient form:

where

(

is the volume corresponding to monolayer completion);

;

is the equilibrium constant

; and

is the mean-field term. In addition,

can be associated with the isosteric heat of adsorption

.

Figure 44 presents the adsorption isotherms of propane (

) in

zeolite. Solid lines represent theoretical predictions using the

model, while symbols show experimental data from Ref. [

120]. Following conventional modeling, alkane chains are treated as "bead segments," where each methyl group corresponds to one adsorption site. Accordingly, propane is modeled as a trimer with

. Given that the propane molecule (

) is relatively large compared to the cavity diameter (

), it likely adsorbs along a preferred orientation. Otherwise, accommodating 5–6 molecules per cavity would be unfeasible. We thus assign

(with

and

, mimicking a 1D configuration). The best fit to the experimental data over the full temperature and pressure range was obtained by simultaneously optimizing

,

and

w (see

Table 2).