Submitted:

14 June 2025

Posted:

16 June 2025

You are already at the latest version

Abstract

Keywords:

1. Introduction

2. Thermodynamic Functions of Multicomponent Lattice Gases with Hard-Core Interactions

3. Monte Carlo Simulation Scheme

-

Initialization:

- Set temperature T, pressure P and molar compositions , and . Accordingly,

-

Random species selection:

- Randomly select one of the three species.

-

Random -uple selection:

-

Randomly select a valid -uple.

- -

- If the -uple is empty: attempt to adsorb a -mer of type selected in step 2 with probability .

- -

- If the -uple is fully occupied by a k-mer of type selected in step 2: attempt to desorb it with probability .

-

-

Repeat the simulation step:

- Repeat steps 2–3 a total of M times to complete one MCS.

4. Results

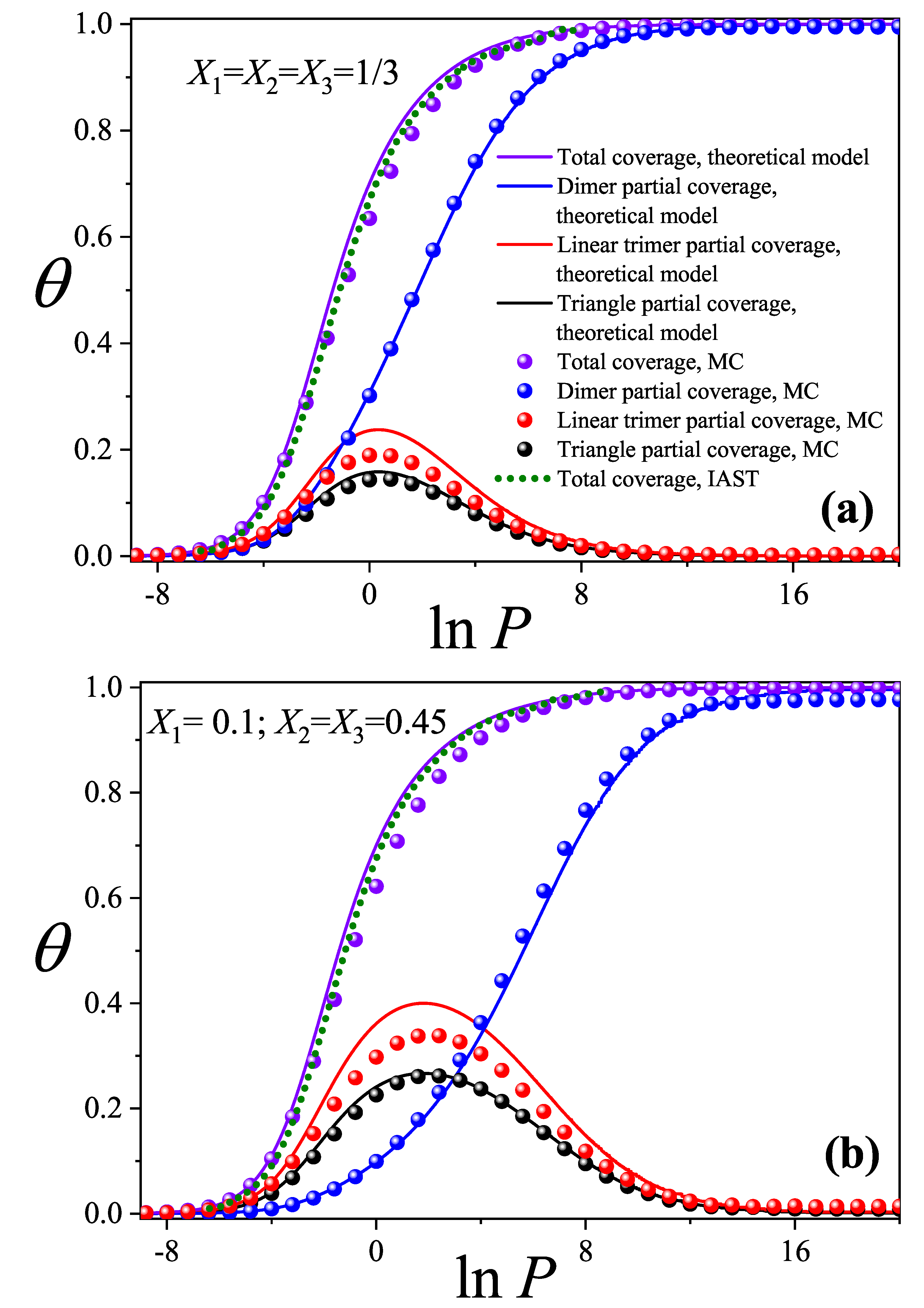

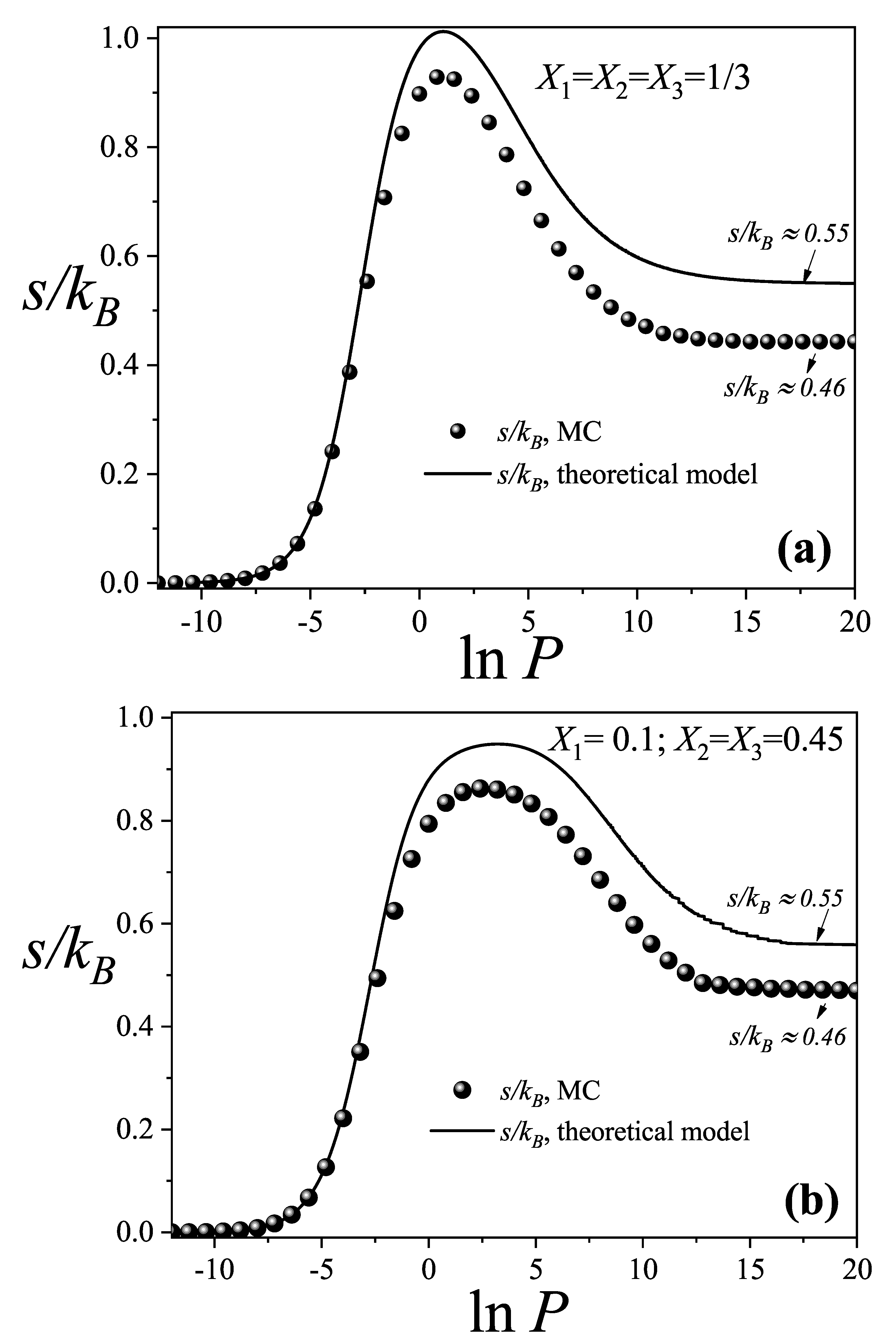

4.1. Adsorption Isotherms and Total Configurational Entropy per Site

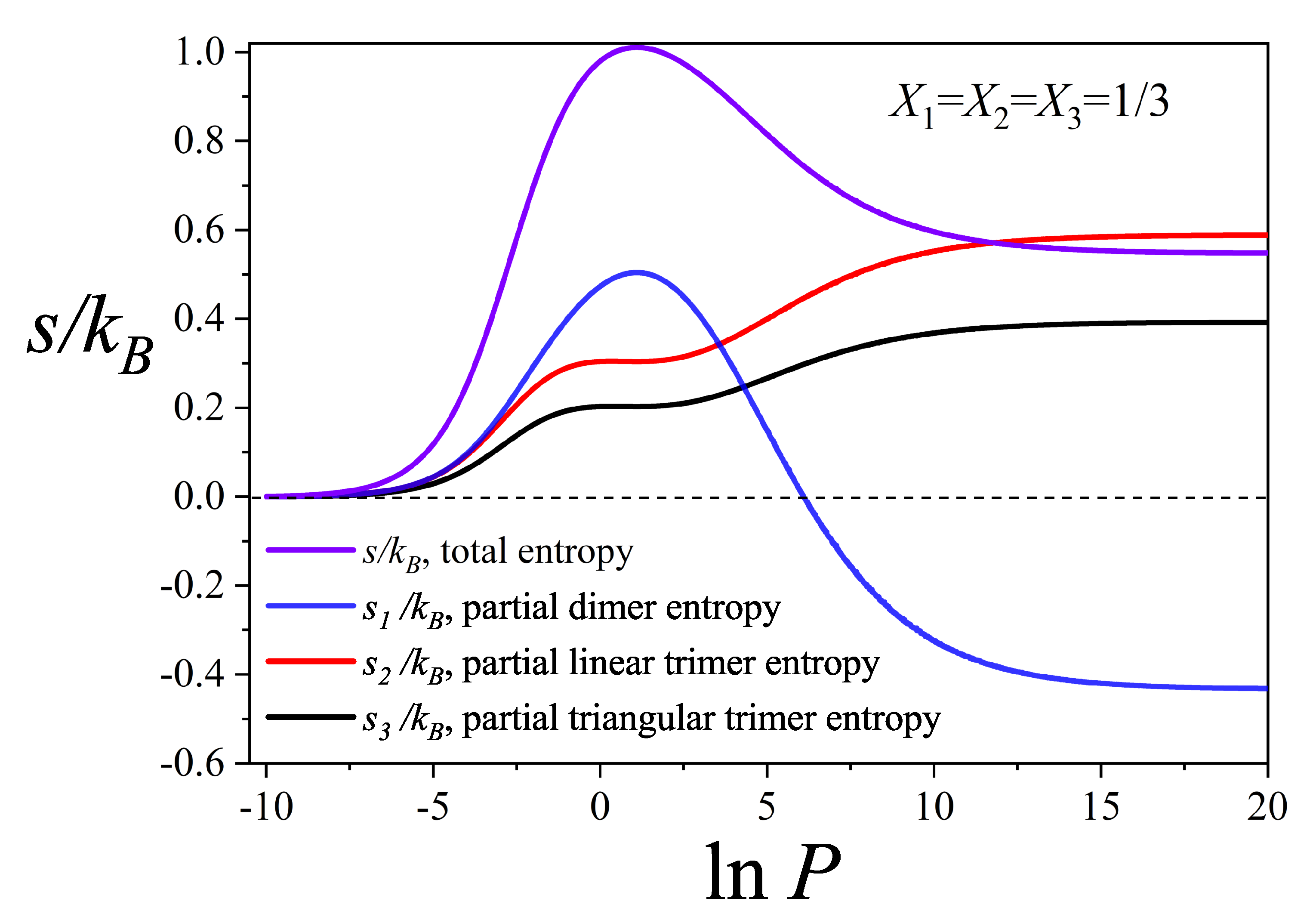

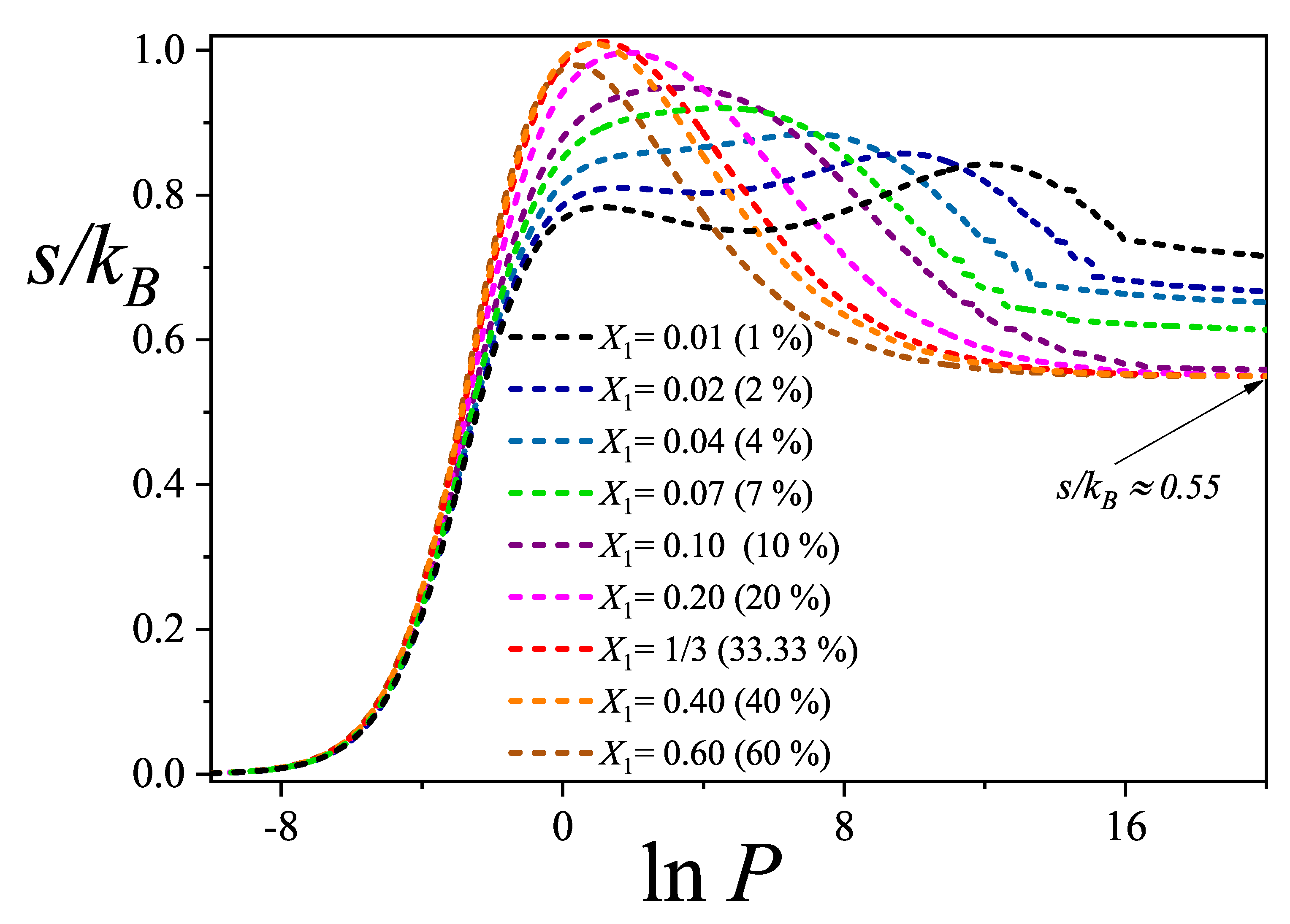

4.2. Configurational Entropy per Site for Different Molar Compositions

5. Conclusions

- The generalized lattice-gas model effectively captures the competitive adsorption behavior driven by molecular size and shape, illustrating the essential role of multisite occupation in realistic surface processes.

- Analytical expressions for thermodynamic quantities, Helmholtz free energy, configurational entropy per site, and total and partial coverage, were derived as functions of pressure. These predictions show excellent agreement with MC simulations for both total and partial isotherms, particularly for dimers and triangular trimers. Some deviations for linear trimers were observed, likely due to an overcounting of accessible configurations.

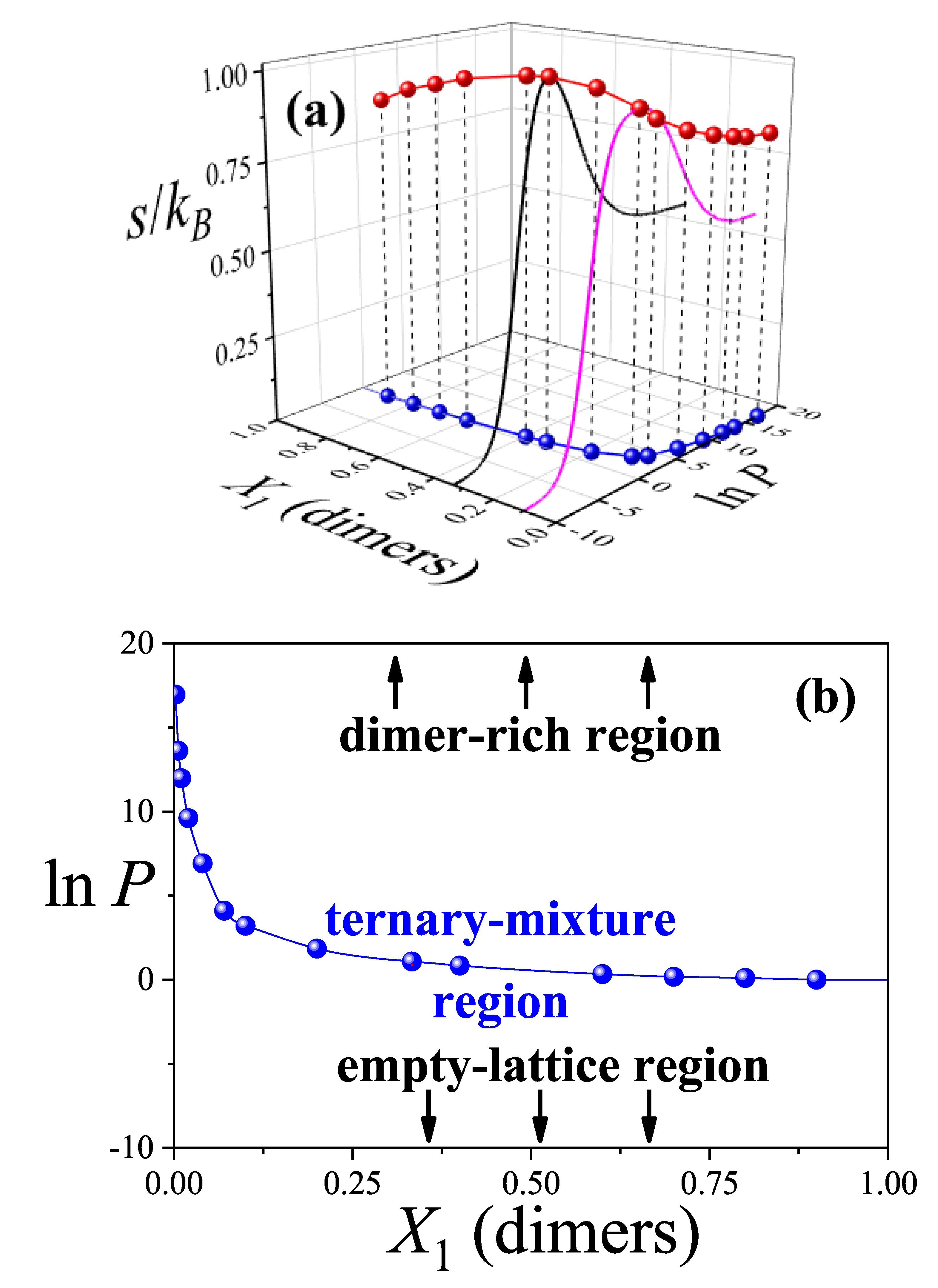

- A detailed entropy analysis reveals an entropy-driven displacement mechanism, where dimers progressively replace larger species at higher pressures, maximizing the system’s entropy prior to lattice saturation. In the high-coverage regime, entropy approaches a limiting value dominated by dimer adsorption, in line with previous studies on fully occupied lattices.

- Despite dimers playing a central role in the displacement process, larger molecules contribute cooperatively. Their ability to occupy residual voids left by smaller species supports the preservation of positive entropy and reinforces thermodynamic consistency, particularly in the behavior of mixing entropy.

- The maximum entropy is attained for equimolar compositions, and the entropy landscape enables construction of an“entropic phase diagram" in the composition-pressure–maximum entropy space. This diagram delineates regions where competitive displacement is either enhanced or suppressed, offering a predictive tool for controlling surface composition, and illustrating the richness of configurational possibilities in such systems.

Author Contributions

Data Availability Statement

Acknowledgments

Conflicts of Interest

Appendix A. Ideal Adsorbed Solution Theory (IAST)

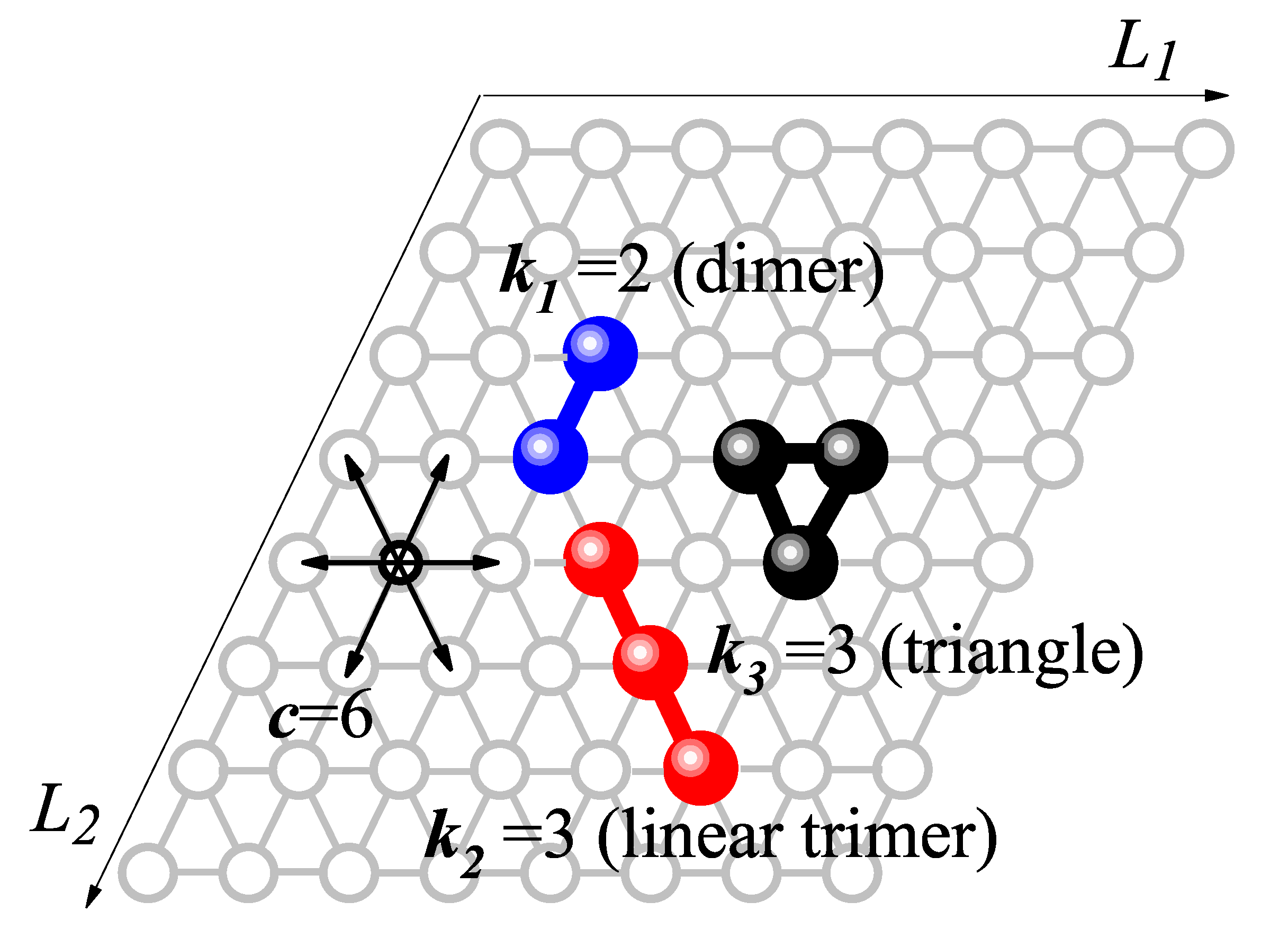

| i | Species | Adsorption isotherm equation | ||

| 1 | dimer | 2 | 3 | |

| 2 | linear trimer | 3 | 3 | |

| 3 | triangular trimer | 3 | 2 |

References

- Rudziński, W.; Steele, W.A.; Zgrablich, G. Equilibria and Dynamics of Gas Adsorption on Heterogeneous Solid Surfaces; Elsevier Science: Amsterdam, Holland, 1996. [CrossRef]

- Yang, R.T. Gas Separation by Adsorption Processes; Butterworth-Heinemann, Oxford, UK, 2013. [CrossRef]

- Ruthven, D.M. Principles of Adsorption and Adsorption Processes; John Wiley & Sons: New York, USA, 1984.

- Talu, O. Needs, status, techniques and problems with binary gas adsorption experiments. Adv. Colloid Interface Sci. 1998, 77, 227–269. [CrossRef]

- Myers, A.L.; Prausnitz, J.M. Thermodynamics of mixed-gas adsorption. AIChE J. 1965, 11, 121–127. [CrossRef]

- Walton, K.S.; Sholl, D.S. Predicting multicomponent adsorption: 50 years of the ideal adsorbed solution theory. AIChE J. 2015, 61, 2757–2762. [CrossRef]

- Tovbin, Y.K. The Theory of Physical Chemistry processes at a Gas-Solid Interfaces; Mir Publishers & CRC Press: Boca Raton, FL, USA, 1991.

- Votyakov, E.V.; Tovbin, Y.K. Phase States of Mixed Adspecies on Heterogeneous Surfaces. Langmuir 1997, 13, 1079–1088. [CrossRef]

- Fefelov, V.F.; Stishenko, P.V.; Kutanov, V.M.; Myshlyavtsev, A.V.; Myshlyavtseva, M.D. Monte Carlo study of adsorption of additive gas mixture. Adsorption 2016, 22, 673–680. [CrossRef]

- Fefelov, V.F.; Myshlyavtsev, A.V.; Myshlyavtseva, M.D. Phase diversity in the adsorption model of additive binary gas mixture for all sets of lateral interactions. Phys. Chem. Chem. Phys. 2018, 20, 10359–10368. [CrossRef]

- V.F.; Myshlyavtsev, A.V.; Myshlyavtseva, M.D. Complete analysis of phase diversity of the simplest adsorption model of a binary gas mixture for all sets of undirected interactions between nearest neighbors. Adsorption 2019, 25, 545–554. [CrossRef]

- Ghosh, A.; Dhar, D. On the orientational ordering of long rods on a lattice. Eur. Phys. Lett. 2007, 78, 20003. [CrossRef]

- Matoz-Fernandez, D.A.; Linares, D.H.; Ramirez-Pastor, A.J. Determination of the critical exponents for the isotropic-nematic phase transition in a system of long rods on two-dimensional lattices: Universality of the transition. Eur. Phys. Lett. 2008, 82, 50007. [CrossRef]

- Khettar, A.; Jalili, S.E.; Dunne, L.J.; Manos, G.; Du, Z. Monte-Carlo simulation and mean-field theory interpretation of adsorption preference reversal in isotherms of alkane binary mixtures in zeolites at elevated pressures. Chem. Phys. Lett. 2002, 362, 414–418. [CrossRef]

- Dunne, L.J.; Manos, G.; Du, Z. Exact statistical mechanical one-dimensional lattice model of alkane binary mixture adsorption in zeolites and comparision with Monte-Carlo simulations. Chem. Phys. Lett. 2003, 377, 551–556. [CrossRef]

- Smit, B.; Maesen, T.L.M. Molecular Simulations of Zeolites: Adsorption, Diffusion, and Shape Selectivity. Chem. Rev. 2008, 108, 4125–4184. [CrossRef]

- Abdul-Reham, H.B.; Loughlin, K.F. Quaternary, Ternary, Binary, and Pure Component Sorption on Zeolites. 1. Light Alkanes on Linde S-115 Silicalite at Moderate to High Pressures. Ind. Eng. Chem. Res. 1990, 29, 1525–1535. [CrossRef]

- Du, Z.; Manos, G.; Vlugt, T.J.H.; Smit, B. Molecular simulation of adsorption of short linear alkanes and their mixtures in silicalite. AIChE J. 1998, 44, 1756–1764. [CrossRef]

- Krishna, R.; Smit, B.; Calero, S. Entropy effects during sorption of alkanes in zeolites. Chem. Soc. Rev. 2002, 31, 185–194. [CrossRef]

- Jiang, J.; Sandler, S.I.; Schenk, M.; Smit, B. Adsorption and separation of linear and branched alkanes on carbon nanotube bundles from configurational-bias Monte Carlo simulation. Phys. Rev. B 2005, 72, 045447. [CrossRef]

- Jiang, J.; Sandler, S.I. Monte Carlo Simulation for the Adsorption and Separation of Linear and Branched Alkanes in IRMOF-1. Langmuir 2006, 22, 5702–5707. [CrossRef]

- Hill, T. L. An Introduction to Statistical Thermodynamics; Addison-Wesley: Reading, USA, 1960.

- Flory, P.J. Thermodynamics of High Polymer Solutions. J. Chem. Phys. 1942, 10, 51–61. [CrossRef]

- Huggins, M.L. Some properties of solutions of long-chain compounds. J. Chem. Phys. 1942, 46, 151–158. [CrossRef]

- Des Cloizeaux, J.; Jannink, G. Polymers in Solution. Their Modelling and Structure; Clarendon Press: Oxford, UK, 1990. [CrossRef]

- Guggenheim, E.A. Statistical Thermodynamics of Mixtures with Zero Energies of Mixing. Proc. R. Soc. London 1944, A183, 203–212. [CrossRef]

- DiMarzio, E.A. Statistics of Orientation Effects in Linear Polymer Molecules. J. Chem. Phys. 1961, 35, 658–669. [CrossRef]

- Ramirez-Pastor, A. J.; Eggarter, T. P.; Pereyra, V.; Riccardo, J. L. Statistical thermodynamics and transport of linear adsorbates, Phys. Rev. B 1999, 59, 11027-11036. [CrossRef]

- Ramirez-Pastor, A.J.; Pereyra, V.D.; Riccardo, J.L. Statistical Thermodynamics of Linear Adsorbates in Low Dimensions: Application to Adsorption on Heterogeneous Surfaces. Langmuir 1999, 15, 5707–5712. [CrossRef]

- Romá, F.; Ramirez-Pastor, A.J.; Riccardo, J.L. Multisite Occupancy Adsorption: Comparative Study of New Different Analytical Approaches. Langmuir 2003, 19, 6770–6777. [CrossRef]

- Riccardo, J.L.; Romá, F.; Ramirez-Pastor, A.J. Fractional Statistical Theory of Adsorption of Polyatomics. Phys. Rev. Lett. 2004, 93, 186101. [CrossRef]

- Riccardo, J.L.; Romá, F.; Ramirez-Pastor, A.J. Generalized statistical description of adsorption of polyatomics. Applied Surf. Sci. 2005, 252 505–511. [CrossRef]

- Haldane, F.D.M. “Fractional statistics" in arbitrary dimensions: A generalization of the Pauli principle Phys. Rev. Lett. 1991, 67, 937–940. [CrossRef]

- Wu, Y.S. Statistical distribution for generalized ideal gas of fractional-statistics particles. Phys. Rev. Lett. 1994, 73, 922–925. [CrossRef]

- Romá, F.; Ramirez-Pastor, A.J.; Riccardo, J.L. Configurational entropy for adsorbed linear species (k-mers). J. Chem. Phys. 2001, 114, 10932–10937. [CrossRef]

- Romá, F.; Ramirez-Pastor, A.J.; Riccardo, J.L. Configurational Entropy in k-mer Adsorption. Langmuir 2000, 16, 9406–9409. [CrossRef]

- Romá, F.; Riccardo, J.L.; Ramirez-Pastor, A.J. Semiempirical Model for Adsorption of Polyatomics. Langmuir 2006, 22, 3192–3197. [CrossRef]

- Riccardo, J.L.; Romá, F.; Ramirez-Pastor, A.J. Adsorption of polyatomics: theoretical approaches in model systems and applications. Int. J. Mod. Phys. B 2006, 20, 4709–4778. [CrossRef]

- Dávila, M.; Riccardo, J.L.; Ramirez-Pastor, A.J. Exact statistical thermodynamics of alkane binary mixtures in zeolites: New interpretation of the adsorption preference reversal phenomenon from multisite-occupancy theory. Chem. Phys. Lett. 2009, 477, 402–405. [CrossRef]

- Matoz-Fernandez, D.A.; Ramirez-Pastor, A.J. Adsorption preference reversal phenomenon frommultisite-occupancy theory for two-dimensional lattices. Chem. Phys. Lett. 2014, 610–611, 131–134. [CrossRef]

- Dávila, M.; Riccardo, J.L.; Ramirez-Pastor, A.J. Fractional statistics description applied to adsorption of alkane binary mixtures in zeolites. J. Chem. Phys. 2009, 130, 174715. [CrossRef]

- De La Cruz Feliz, N.M.; Longone, P.J.; Sanchez-Varretti, F.O.; Bulnes, F.M.; Ramirez-Pastor, A.J. Cluster approximation applied to multisite-occupancy adsorption: configurational entropy of the adsorbed phase for dimers and trimers on triangular lattices. Phys. Chem. Chem. Phys. 2023, 25, 14942–14954. [CrossRef]

- Nitta, T.; Kuro-Oka, M.; Katayama, T. An adsorption isotherm of multi-site occupancy model for heterogeneous surface. J. Chem. Eng. Jpn. 1984, 17, 45–52. [CrossRef]

- Nitta, T.; Yamaguchi, A. J. A hybrid isotherm equation for mobile molecules adsorbed on heterogeneous surface of random topography. J. Chem. Eng. Jpn. 1992, 25, 420–426. [CrossRef]

- Longone, P.; Martín, A.; Ramirez-Pastor, A.J. Stability and cell distortion of sI clathrate hydrates of methane and carbon dioxide: A 2D lattice-gas model study. Fluid Phase Equilib. 2015, 402, 30–37. [CrossRef]

- Longone, P.; Martín, A.; Ramirez-Pastor, A.J. Lattice-gas Monte Carlo study of sI clathrate hydrates of ethylene: Stability analysis and cell distortion. Fluid Phase Equilib. 2020, 521, 112739–37. [CrossRef]

- Longone, P.; Martín, A.; Ramirez-Pastor, A.J. CO2-CH4 Exchange Process in Structure I Clathrate Hydrates: Calculations of the Thermodynamic Functions Using a Flexible 2D Lattice-Gas Model and Monte Carlo Simulations. J. Phys. Chem. B 2022, 126, 878–-889. [CrossRef]

- Schick, M. The classification of order-disorder transitions on surfaces. Prog. Surf. Sci. 1981, 11, 245–-292. [CrossRef]

- Yeomans, J.M. Statistical Mechanics of Phase Transitions; Clarendon Press: Oxford, UK, 1992.

- Kinzel, K.; Schick, M. Phenomenological scaling approach to the triangular Ising antiferromagnet. Phys. Rev. B 1981, 23, 3435–-3441. [CrossRef]

- Chin, K.K.; Landau, D.P. Monte Carlo study of a triangular Ising lattice-gas model with two-body and three-body interactions. Phys. Rev. B 1987, 36, 275–-284. [CrossRef]

- Phares, A.J.; Grumbine Jr., D.W.; Wunderlich, F.J. Adsorption on an Equilateral Triangular Terrace Three Atomic Sites in Width: Application to Chemisorption of CO on Pt(112). Langmuir 2006, 22, 7646–7651. [CrossRef]

- Phares, A.J.; Grumbine Jr., D.W.; Wunderlich, F.J. Monomer Adsorption on Equilateral Triangular Lattices with Attractive First-neighbor Interactions. Langmuir 2008, 24, 124–134. [CrossRef]

- Nicholson, D.; Parsonage, N.G. Computer Simulation and the Statistical Mechanics of Adsorption; Academic Press: London, UK, 1982.

- Binder, K. Applications of the Monte Carlo method in statistical physics. In Topics in current Physics, vol. 36; Binder, K., Ed.; Springer, Berlin, Germany, 1984; pp. 1–36. https://link.springer.com/book/10.1007/978-3-642-51703-7.

- Binder, K. Static and dynamic critical phenomena of the two-dimensionalq-state Potts model. J. Stat. Phys. 1981, 24, 69–86. [CrossRef]

- Polgreen, T.L. Monte Carlo simulation of the fcc antiferromagnetic Ising model. Phys. Rev. B 1984, 29, 1468–1471. [CrossRef]

- Hansen, J.P.; Verlet, L. Phase Transitions of the Lennard-Jones System. Phys. Rev. 1969, 184, 151–161. [CrossRef]

- Press, W.H.; Flannery, B.P.; Teukolsky, S.A.; Vetterling, W.T. Numerical Recipes in C: the Art of Scientific Computing; Cambridge University Press: Cambridge, UK, 1992.

- Sanchez-Varretti, F.O.; Garcia, G.D.; Pasinetti, P.M.; Ramirez-Pastor, A.J. Adsorption of binary mixtures on two-dimensional surfaces: theory and Monte Carlo simulations. Adsorption 2014, 20, 855–862. [CrossRef]

- Sanchez-Varretti, F.O.; Bulnes, F.M.; Ramirez-Pastor, A.J. A cluster-exact approximation study of the adsorption of binary mixtures on heterogeneous surfaces. Appl. Surf. Sci. 2016, 387, 268–273. [CrossRef]

- Sanchez-Varretti, F.O.; Pasinetti, P.M.; Bulnes, F.M.; Ramirez-Pastor, A.J. Adsorption of laterally interacting gas mixtures on homogeneous surfaces. Adsorption 2017, 23, 651–662. [CrossRef]

- Sanchez-Varretti, F.O.; Bulnes, F.M.; Ramirez-Pastor, A.J. Cluster-exact approximation applied to adsorption with non-additive lateral interactions. Physica A 2019, 518, 145–157. [CrossRef]

- Lopez Ortiz, J.I.; Torres, P.; Quiroga, E.; Narambuena, C.F.; Ramirez-Pastor, A.J. Adsorption of three-domain antifreeze proteins on ice: a study using LGMMAS theory and Monte Carlo simulations, Phys. Chem. Chem. Phys. 2017, 19, 31377–31388. [CrossRef]

- Wu, F.Y. Dimers on two-dimensional lattices. Int. J. Mod. Phys. B 2006, 20, 5357–5371. [CrossRef]

- Scatchard, G. The Gibbs Adsorption isotherm. J. Phys. Chem. 1962, 66, 618–620. [CrossRef]

| 1 | This phenomenon, known as adsorption preference reversal (APR), is observed in systems such as methane–ethane mixtures [14,15]. APR involves a counterintuitive inversion in selectivity with pressure: ethane dominates adsorption at low pressure, whereas methane becomes predominant at higher pressures. Similar behavior has been reported for hydrocarbon mixtures in silicalite [16,17,18,19], carbon nanotube bundles [20], and MOFs [21]. APR arises due to the difference in molecular size and, consequently, site occupancy. |

Disclaimer/Publisher’s Note: The statements, opinions and data contained in all publications are solely those of the individual author(s) and contributor(s) and not of MDPI and/or the editor(s). MDPI and/or the editor(s) disclaim responsibility for any injury to people or property resulting from any ideas, methods, instructions or products referred to in the content. |

© 2025 by the authors. Licensee MDPI, Basel, Switzerland. This article is an open access article distributed under the terms and conditions of the Creative Commons Attribution (CC BY) license (http://creativecommons.org/licenses/by/4.0/).