Submitted:

27 October 2025

Posted:

03 November 2025

You are already at the latest version

Abstract

Keywords:

1. Introduction

2. Results and Discussion

2.1. Phase-State Control of Deposition (Overview)

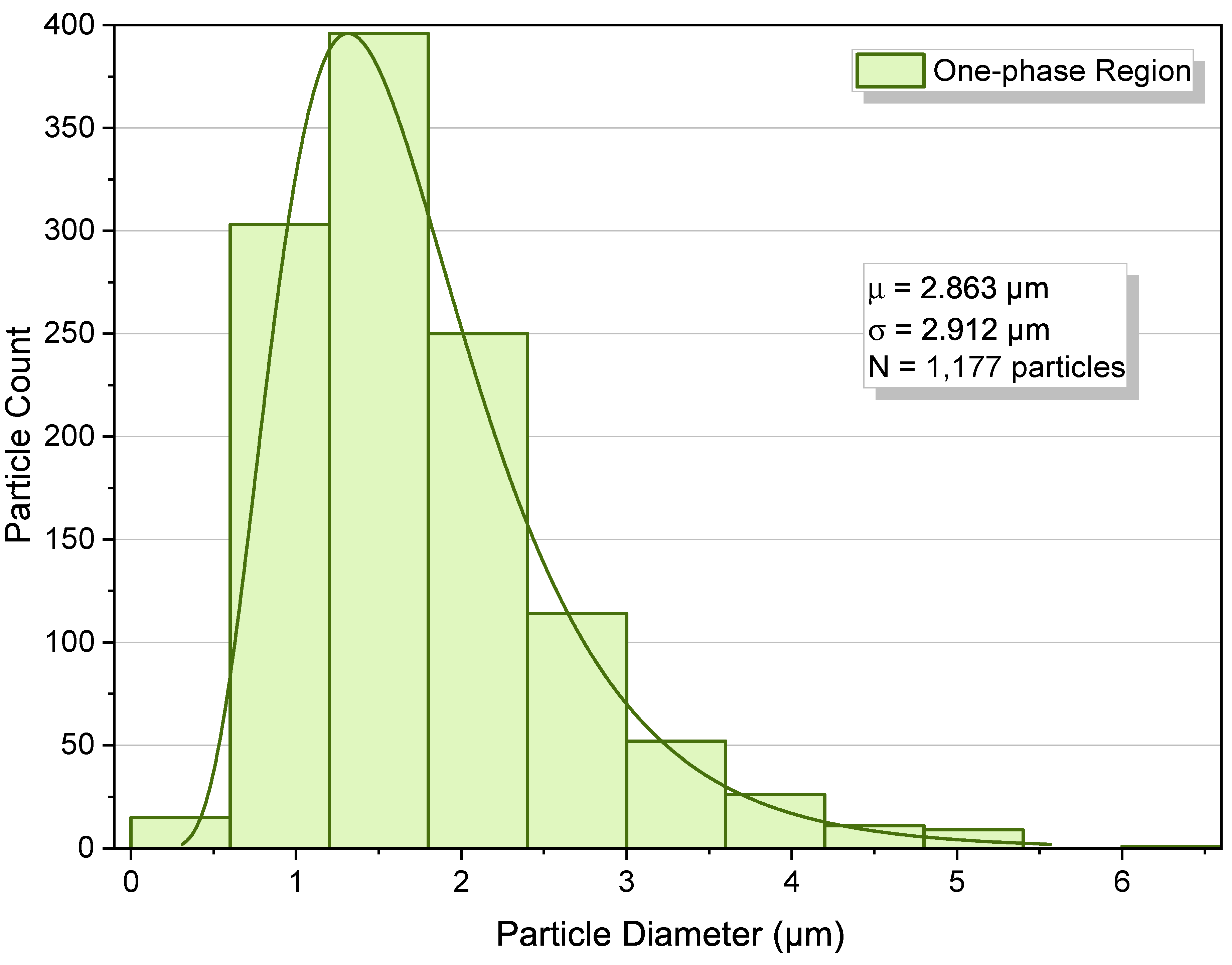

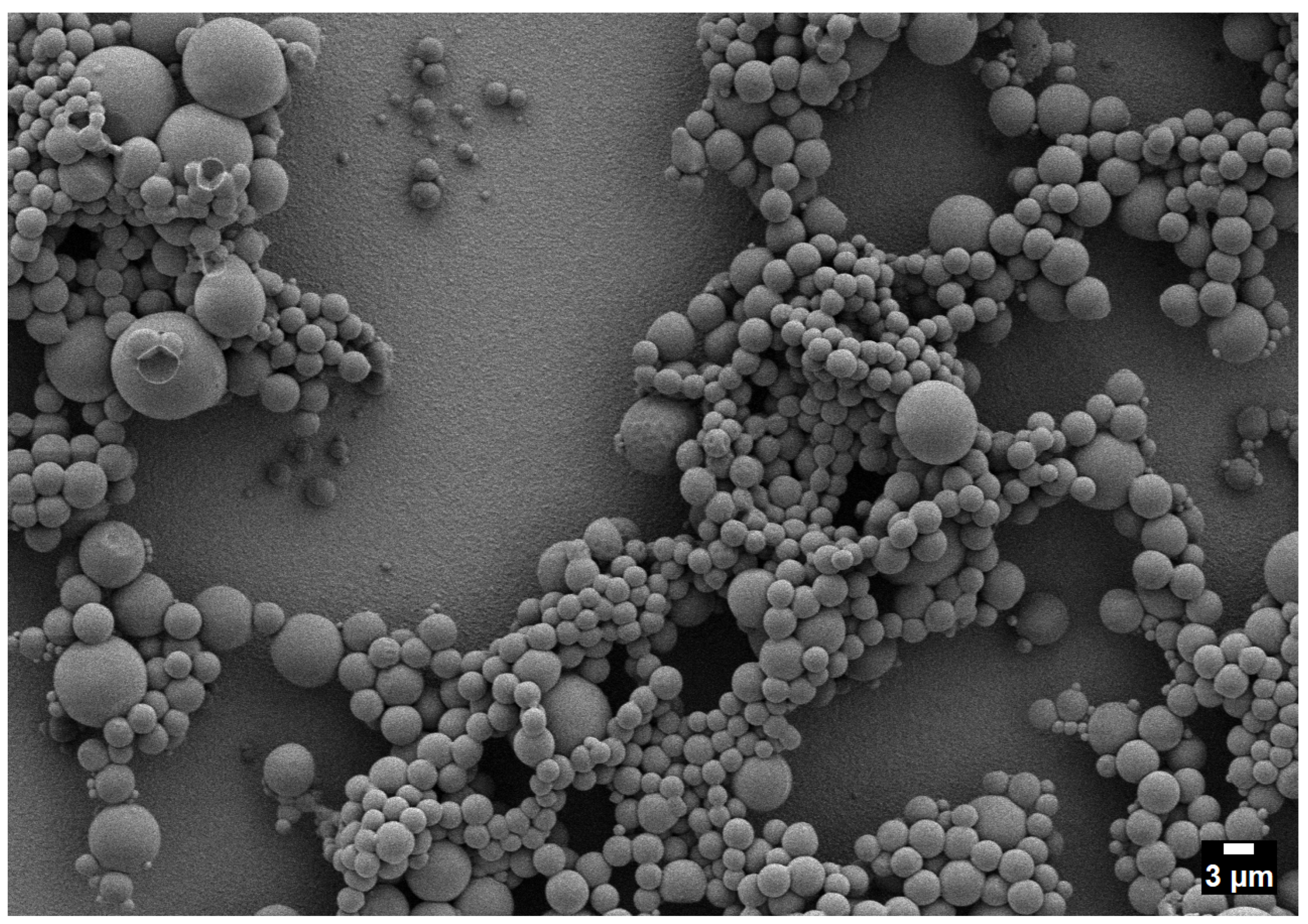

2.2. One-Phase Region

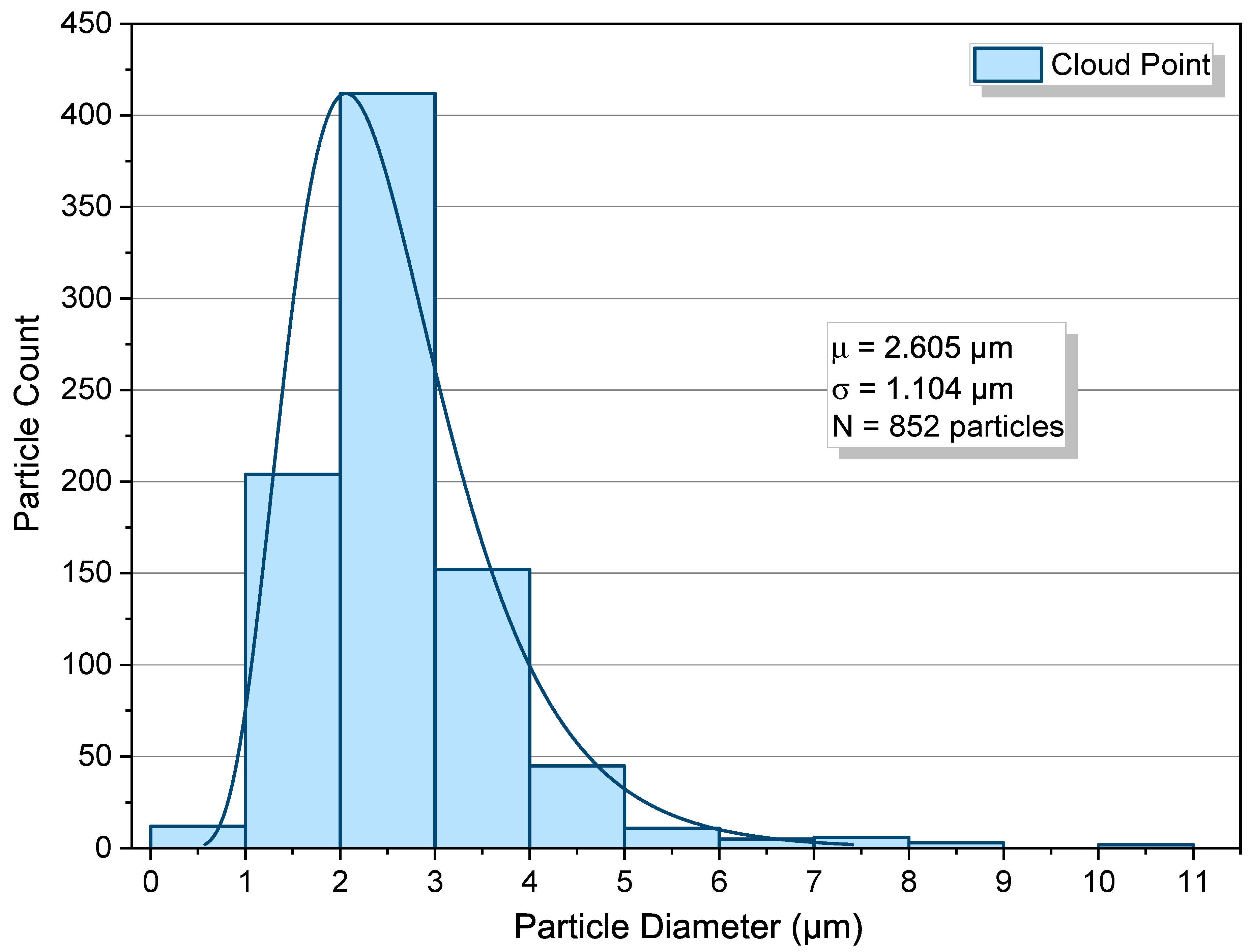

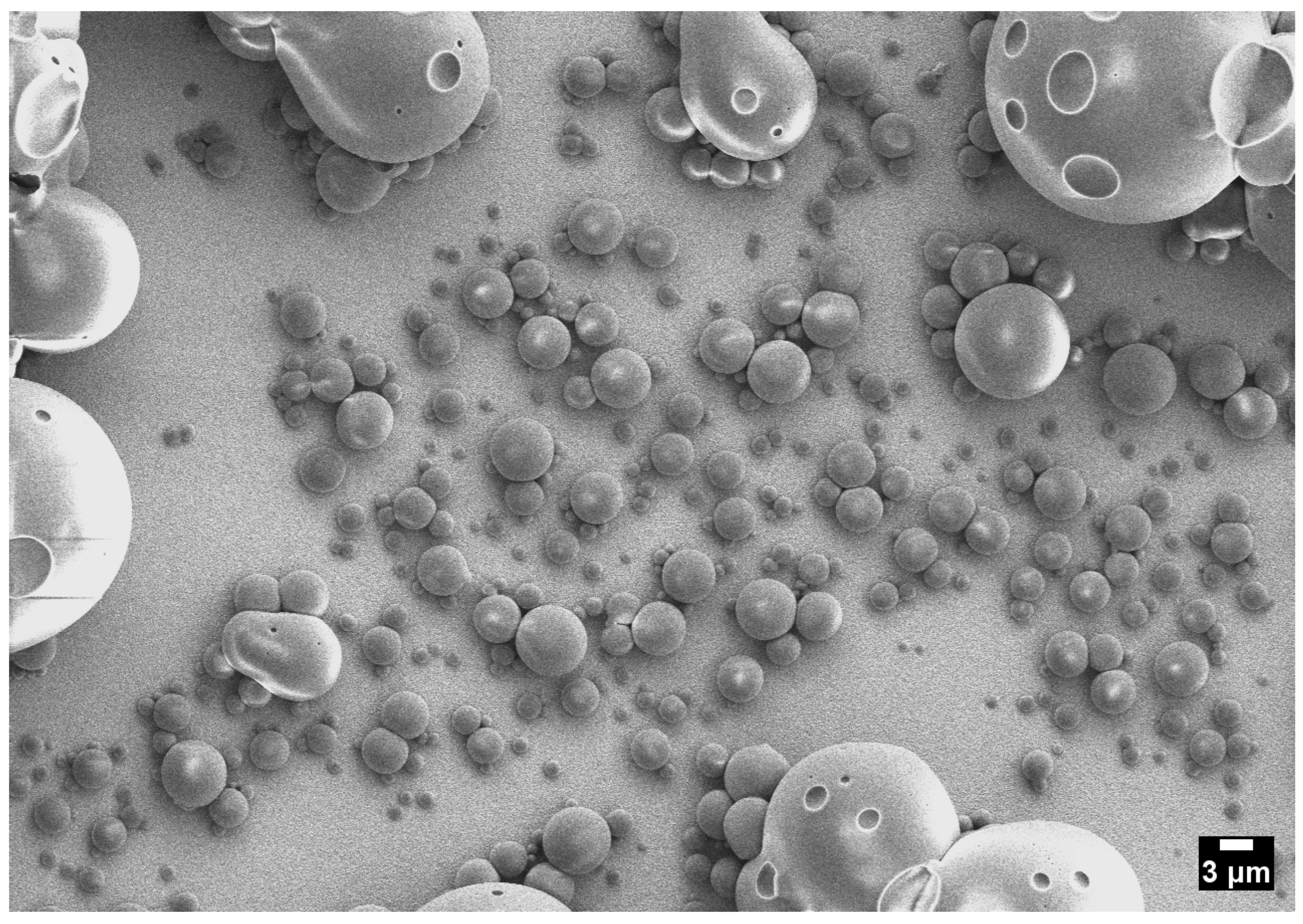

2.3. Cloud-Point Condition

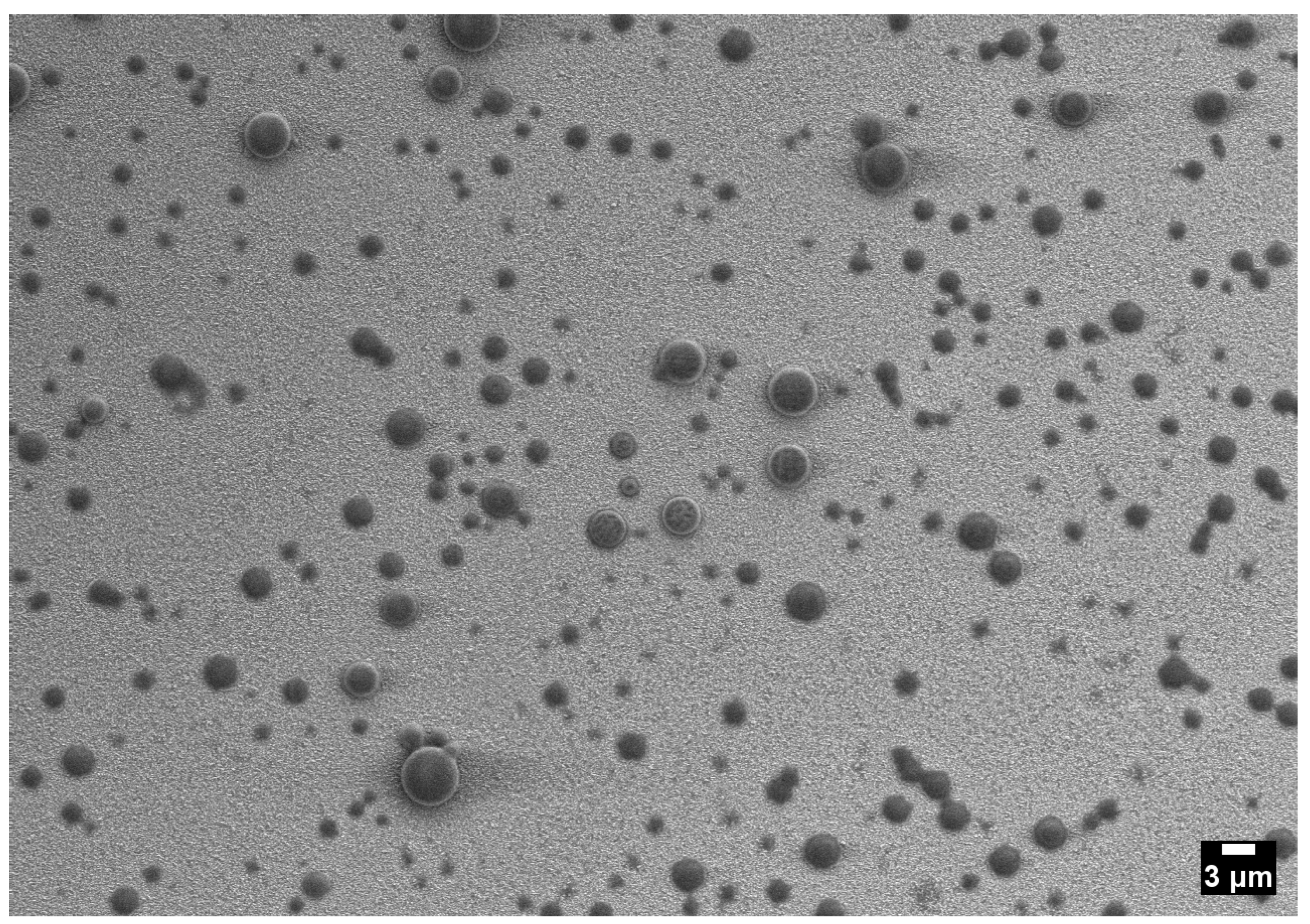

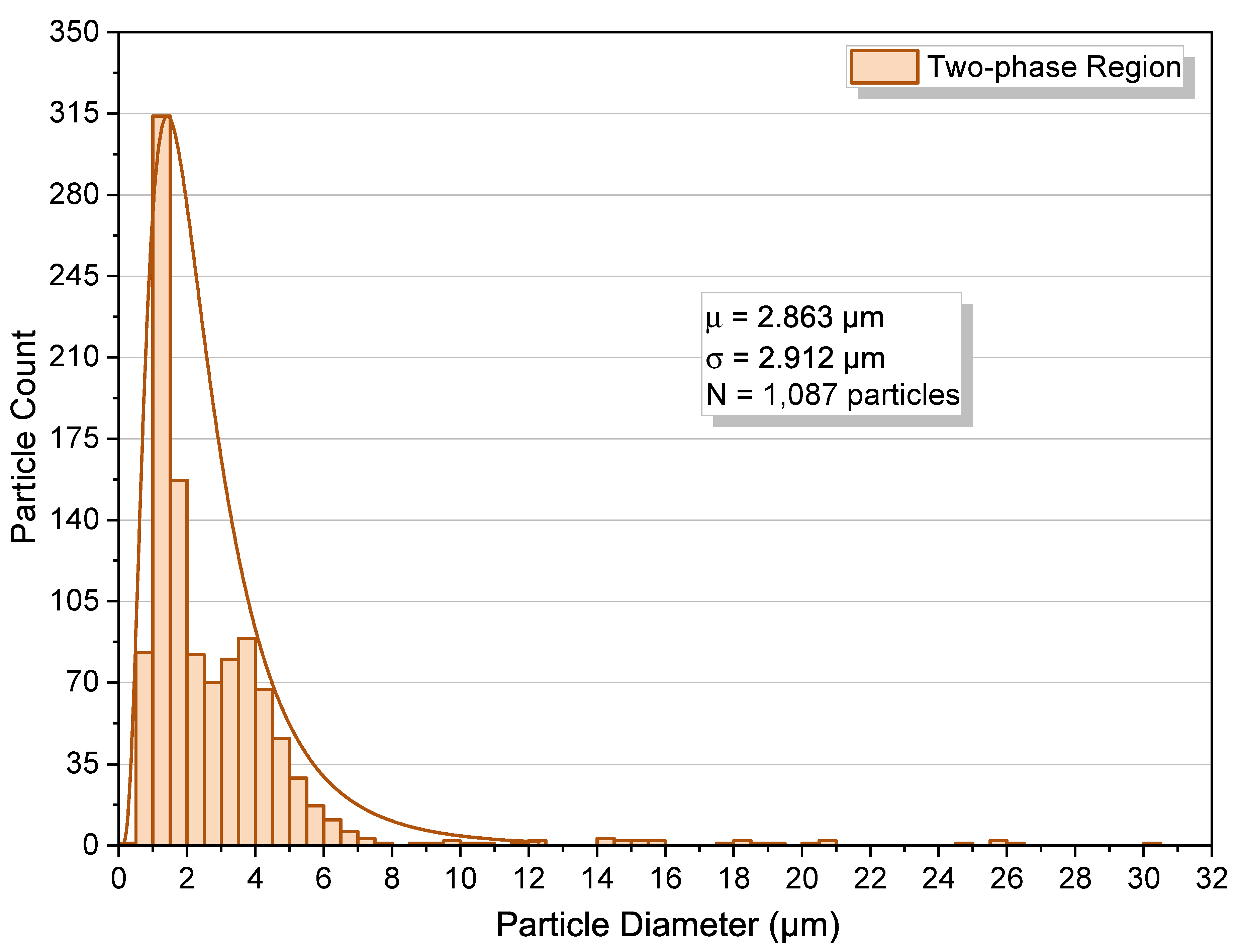

2.4. Two-Phase Region

2.4.1. Origin of Crater-Like Pits (Outgassing Mechanism)

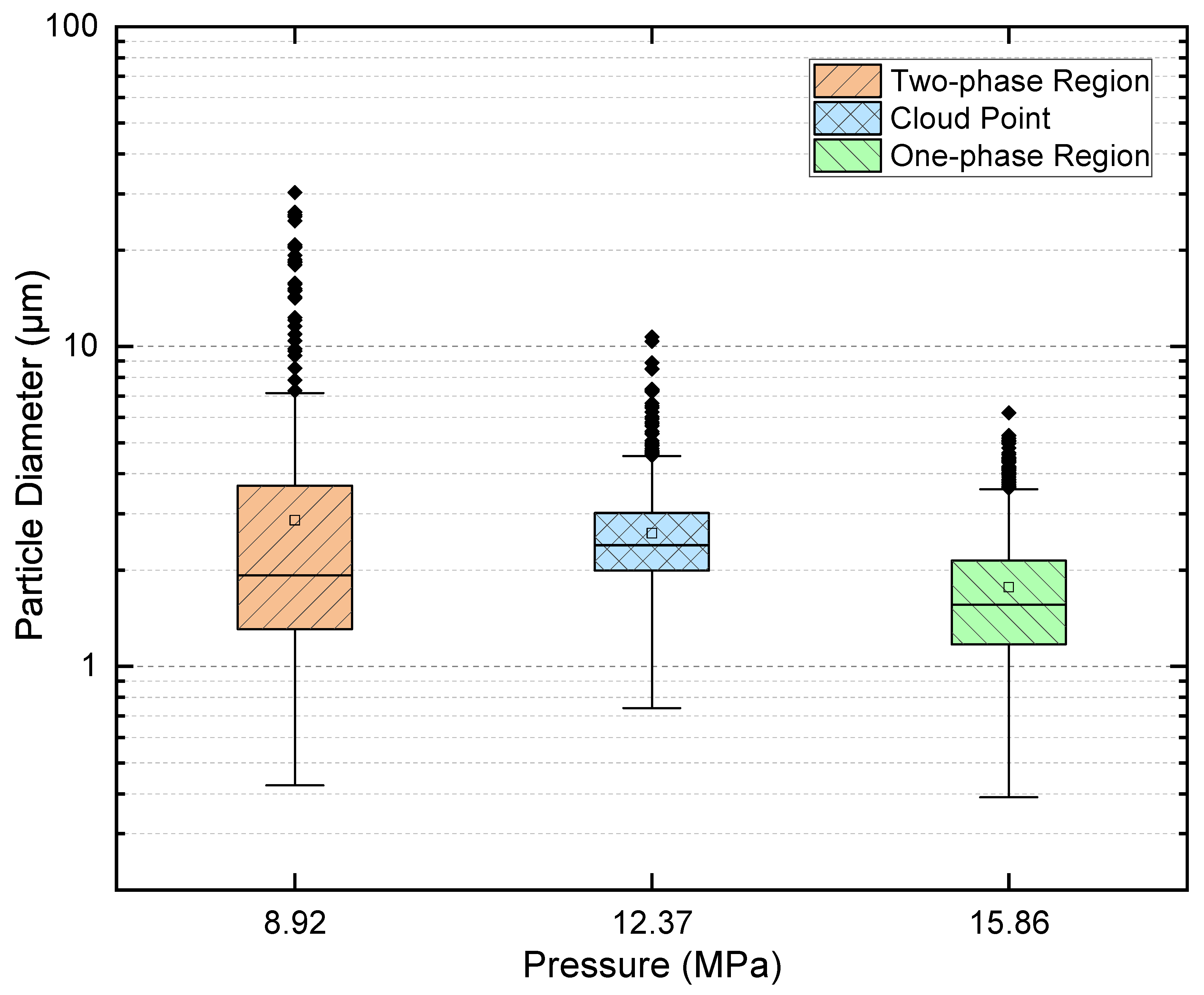

2.5. Quantitative Cross-Condition Comparison and Mechanistic Synthesis

- One-phase operation favors compact, relatively uniform deposits with minimal interparticle interaction.

- Cloud-point operation increases coverage and shifts sizes upward while retaining a single mode and only modest dispersion.

- Two-phase operation yields the broadest dispersions and the largest outliers as a result of coalescence and vent-induced hollowing.

3. Materials and Methods

3.1. Materials

- Carbon dioxide (CO2), obtained from Airgas (Philadelphia, PA, USA); certified purity 99.9995%.

- Poly(2,2,2-trifluoroethyl methacrylate) [poly(TFEMA); trifluoroethyl methacrylate homopolymer], obtained from Specific Polymers (Castries, France). Supplier data: , , .

- Toluene (C7H8; 99.8%), obtained from Sigma-Aldrich (St. Louis, MO, USA).

- Fluorine-doped tin oxide (FTO) coated glass substrates, 25 mm × 25 mm, obtained from Ossila Ltd (Solpro Business Park, Windsor Street, Sheffield, S4 7WB, UK).

3.2. Substrate Preparation

- Initial wash: Substrates were washed with a solution of deionized (DI) water and Alconox detergent (Powder Precision Cleaner, Sigma-Aldrich), then rinsed with DI water and placed into a polypropylene substrate cleaning rack (Ossila, Product Code E102).

- Ultrasonic cleaning with Hellmanex: The rack was placed in a Branson Ultrasonic Cleaner (Model 1510; Branson Ultrasonics Corp., Wallingford, CT, USA). A Hellmanex III working solution (prepared by diluting 2 mL Hellmanex III, Ossila, in 100 mL DI water) was added to the rack compartments. The ultrasonic bath reservoir was filled with water to a level just below the top of the rack height to ensure full immersion. Sonication was performed for 15 min at ambient temperature.

- Rinsing: Substrates were removed and rinsed with DI water to remove Hellmanex residues.

- Sequential solvent sonication: Substrates were sonicated first in isopropyl alcohol (IPA, ≥99.7%, Sigma-Aldrich) for 15 min, followed by acetone (≥99.5%, Sigma-Aldrich) for 15 min.

- Final rinses and drying: After solvent sonication, substrates were rinsed with acetone and then with IPA, and quickly dried using a stream of high-pressure dry air to prevent residues or liquid spots.

- Plasma treatment: Substrates were plasma-cleaned for 4 min in a Solarus 950 advanced plasma system (Gatan Inc., Pleasanton, CA, USA). The plasma environment consisted of 75% argon and 25% oxygen at 25 psi, with feed gases of 99.995% purity.

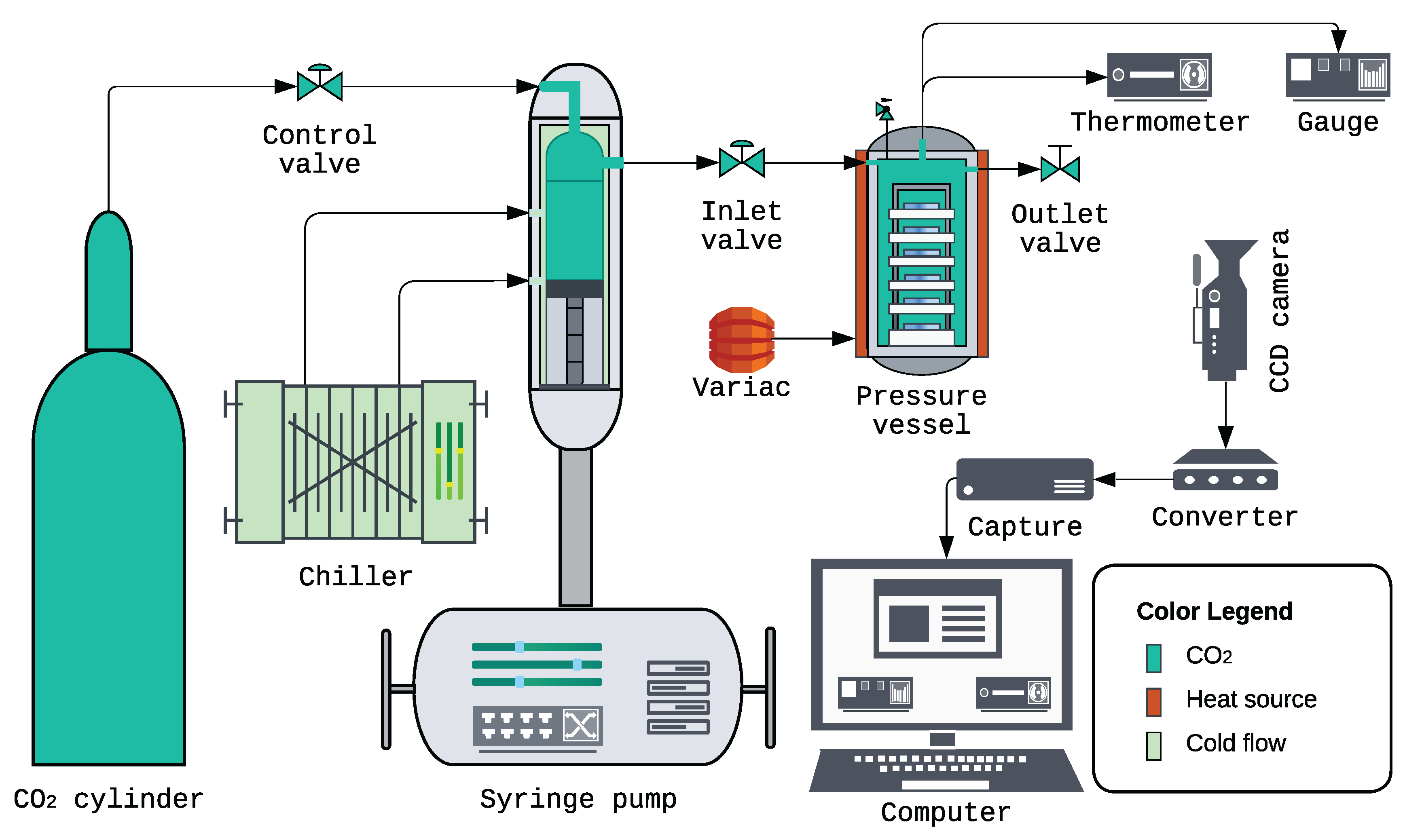

3.3. Supercritical Deposition System and Instrumentation

- CO2 cylinder: High-purity CO2 was supplied from a compressed-gas cylinder via high-pressure stainless-steel tubing and a control valve to the syringe pump, providing a clean and continuous feed.

- Syringe pump: Teledyne ISCO 260D (Teledyne Isco, Lincoln, NE, USA) pressurized and delivered CO2 to the pressure vessel with precise control of delivery rate and final set pressure, enabling reproducible attainment of the one-phase, cloud-point, and two-phase conditions.

- Pump-head chiller: Neslab CFT-25 refrigerated recirculator (Neslab Instruments Inc., Portsmouth, NH, USA) cooled the syringe pump head to increase CO2 density during each loading cycle, thereby increasing the mass delivered per stroke and reducing the number of charging iterations needed to reach the target vessel pressure.

- High-pressure vessel: Parr 4768 reactor (Parr Instrument Company, Moline, IL, USA) housed the substrates, polymer, cosolvent, and scCO2 during deposition (nominal capacity 600 mL). The effective working volume was experimentally determined by an Archimedes displacement procedure to be 424.89 mL. Key specifications: head style VGR; maximum working pressure 3000 psi at 350 ℃; maximum working temperature 350 ℃ with flat PTFE gasket.

- Heating and temperature monitoring: A Staco Variac autotransformer (Model 3PN1010B; Staco Energy Products Co., Dayton, OH, USA; input 120 V, output 0–140 V, 12 A, 1.4 kVA) powered a heavy-duty heating tape (HTS/Amptek AWD-051-060, Stafford, TX, USA; 120 V, 312 W) wrapped around the vessel to regulate temperature. The internal temperature was measured with a J-type thermocouple inserted through the head of the vessel (the rod extending into the chamber) and read on an OMEGA HH506 digital thermometer (Omega Engineering Inc., Norwalk, CT, USA).

- Pressure monitoring: The vessel pressure was measured using an OMEGA PX309-10KGI pressure transducer with readout on an OMEGA DP400TP high-speed panel meter (Omega Engineering Inc., Norwalk, CT, USA). The combined system precision was of full scale (including linearity, hysteresis, and repeatability), providing reliable real-time control.

- Video monitoring: A Vanxse CCTV Mini HD 1/3 CCD 960H Auto Iris Camera (Model BX2812; Shenzhen Kaixing Security Technology Co., Ltd., Shenzhen, China; NTSC) recorded the HH506 (temperature) and DP400TP (pressure) displays. The signal passed through a NOVPEAK BNC CCTV S-Video to VGA converter (Model UPD39 E01A; SQdeal) and an ATCCPYDM VGA-to-USB 2.0 capture card (Model V2U-LO) prior to transfer to the computer.

- Data acquisition: Video files containing synchronized pressure and temperature readings were captured and archived for each run using OBS Studio 30.0.2 (OBS Project, open-source). These time-stamped recordings were used for post hoc frame-by-frame analysis to verify vessel conditions and improve the accuracy of the reported experimental values across all deposition regimes.

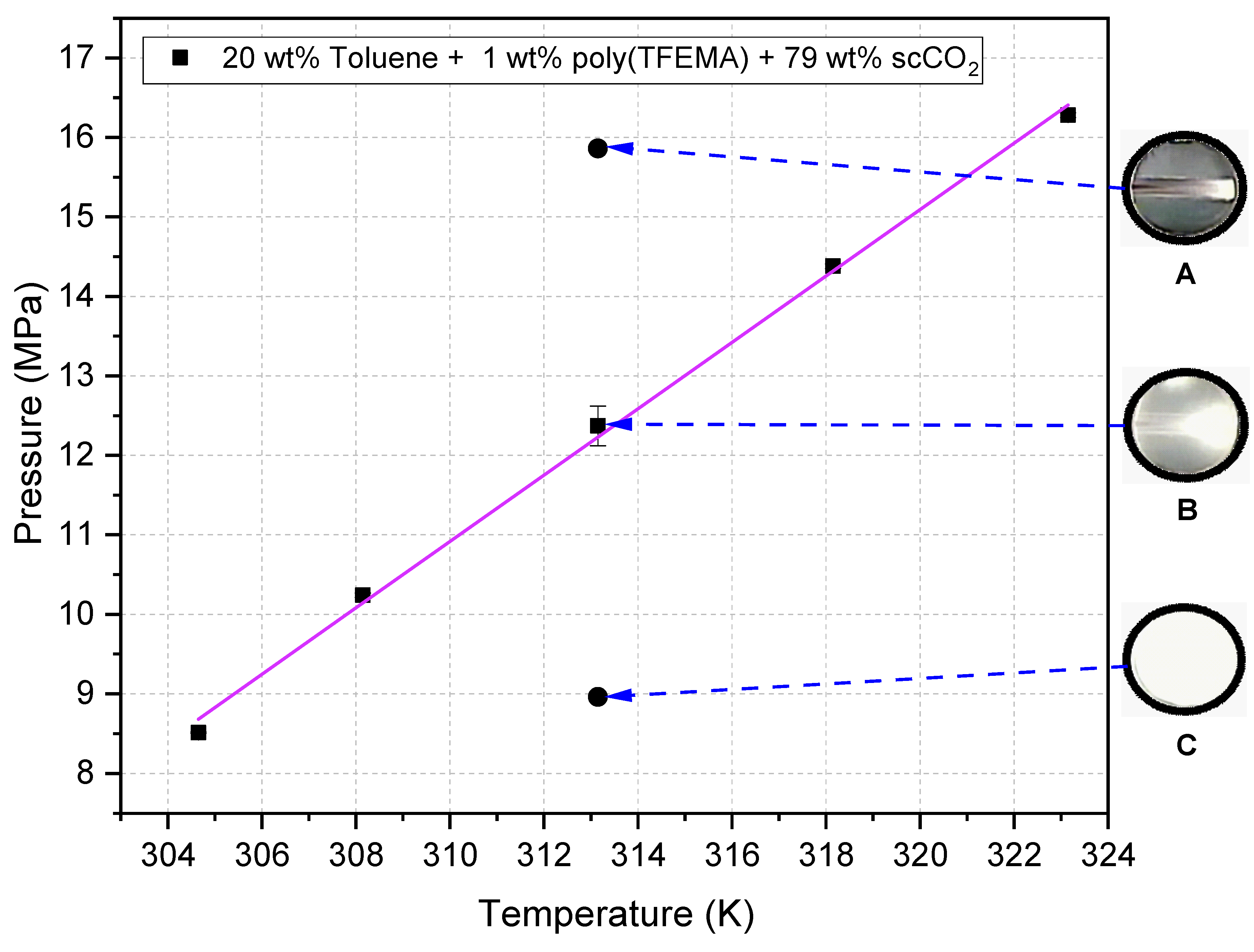

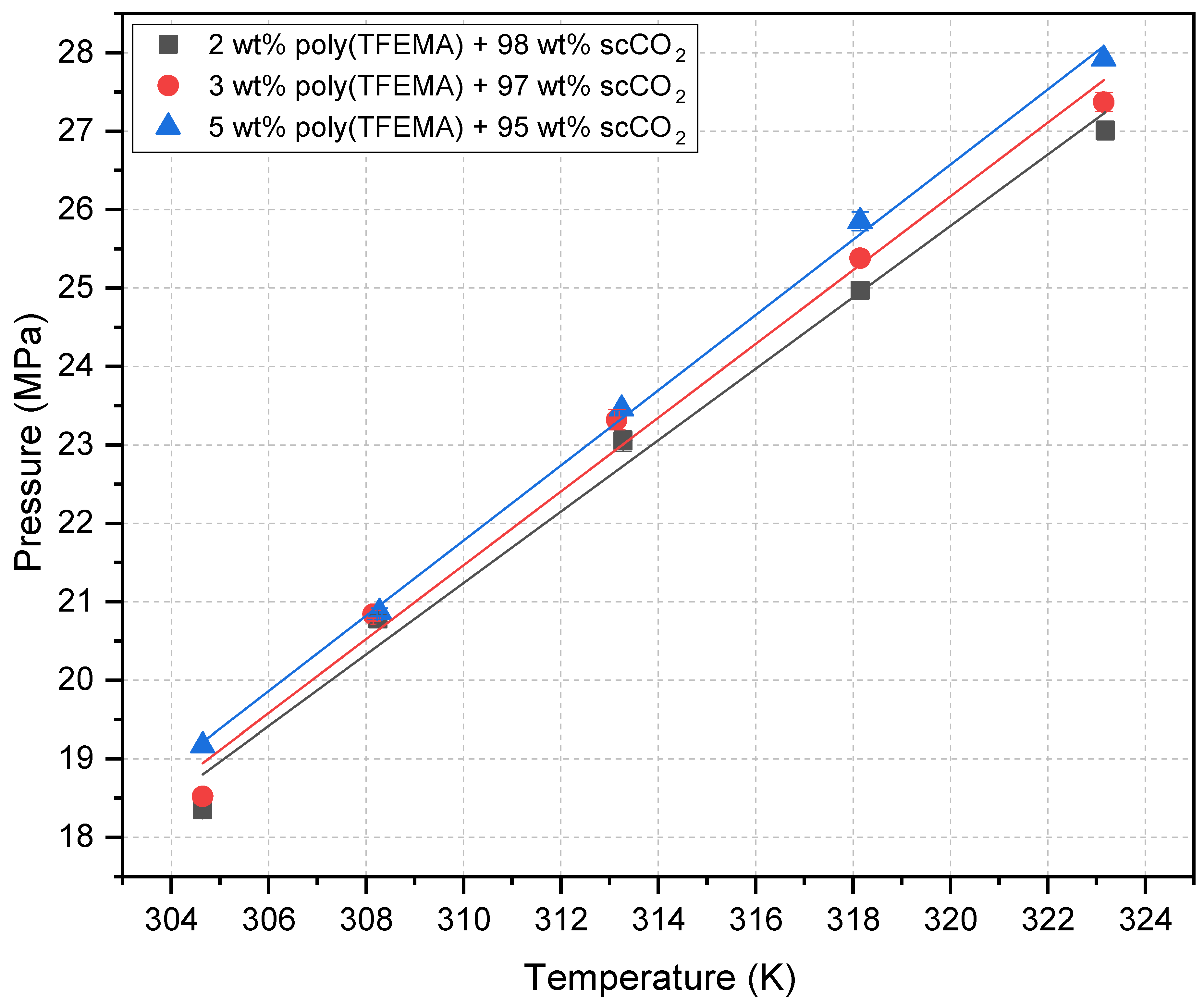

3.4. Cloud-Point References and Set-Point Selection

3.5. Deposition Procedures and Compositions

- Charge and fixturing. Dispense the prescribed toluene volume (Table 3) into the open vessel using a beaker and calibrated pipette. Mount one cleaned substrate on each of the top three rack levels; place the weighed poly(TFEMA) on the fourth level, directly beneath the lowest substrate.

- Sealing and heating. Install the head; tighten bolts in a star pattern in 5 lb-ft increments to a final torque of 25 lb-ft (∼34 N·m). Apply heat with a Variac-driven tape and equilibrate at 40 ℃ (313.15 K).

- CO2 introduction and purge. With the syringe pump set to 20 mL min−1, pressurize to ∼3.45 MPa (∼500 psi), then purge three times by venting to ∼2.07 MPa (∼300 psi) and repressurizing to remove air and moisture while retaining polymer and toluene (outlet valve cracked only minimally).

- Stabilization. Resume CO2 addition and follow the pressure path specific to the targeted regime (as specified in Pressure paths and rationale, below). Start the 30 min deposition clock only when both temperature (313.15 K) and pressure are stable.

- One-phase, 15.86 MPa. Pressurize directly at 20 mL min−1 to 15.86 MPa at 313.15 K; close the inlet valve to isolate; hold 30 min. This sets a homogeneous one-phase state throughout the treatment, consistent with the clear-field phase-monitor image in Figure 12A.

- Cloud point, 12.37 MPa. First pressurize to ≈12.62 MPa at 313.15 K (one-phase region) to ensure complete dissolution; then reduce slowly to 12.37 MPa by cracking the outlet valve to minimize solvent or polymer loss; hold 30 min. The visual endpoint is the first persistent haze captured through the phase monitor (Figure 12B), our reversible-turbidity criterion.

- Two-phase, 8.96 MPa. First pressurize to ≈12.41 MPa at 313.15 K to dissolve polymer; then decompress slowly to 8.96 MPa; hold 30 min. The phase monitor shows sustained turbidity at this isobar (Figure 12C), confirming operation in the polymer-saturated two-phase region.

- Immerse the vessel in an ice–water bath (0 ℃) while sealed to precipitate toluene from the supercritical phase and quench further mass transfer.

- When the external thermometer reads ∼16 ℃, vent slowly and continuously to ambient pressure, remove the head, and retrieve the substrates for ex situ characterization.

3.6. SEM Preparation and Imaging

4. Conclusions

References

Author Contributions

Funding

Institutional Review Board Statement

Informed Consent Statement

Data Availability Statement

Acknowledgments

Conflicts of Interest

Abbreviations

| AG–HGK | Altunin–Gadetskii–Haar–Gallagher–Kell (equation of state for CO2) | |

| CCD | Charge-coupled device (camera) | |

| CV | Coefficient of variation () | |

| DI | Deionized (water) | |

| EOS | Equation of state | |

| FTO | Fluorine-doped tin oxide | |

| IPA | Isopropyl alcohol | |

| IQR | Interquartile range | |

| PDI | Polydispersity index | |

| PSD | Particle-size distribution | |

| PTFE | Polytetrafluoroethylene | |

| scCO2 | Supercritical carbon dioxide | |

| SEM | Scanning electron microscopy | |

| TFEMA | 2,2,2-trifluoroethyl methacrylate (poly(TFEMA) denotes the homopolymer) | |

| Glass transition temperature | ||

| Symbol | Description | Units |

| P | Pressure | MPa |

| T | Temperature | K (or ℃) |

| CO2 density (EOS) | kg m−3 | |

| Mass of scCO2 charged | g | |

| Mass of toluene charged | g | |

| Volume of toluene charged | mL | |

| Mass of poly(TFEMA) | g | |

| Polymer mass fraction | wt% | |

| Cloud-point pressure | MPa | |

| N | Sample size (particle count) | – |

| Mean particle diameter | m | |

| Standard deviation of diameter | m | |

| Coefficient of variation () | – | |

| Critical nucleus radius | nm (or m) | |

| Nucleation free-energy barrier | J |

References

- Ovaskainen, L.; Rodriguez-Meizoso, I.; Birkin, N.A.; Howdle, S.M.; Gedde, U.; Wågberg, L.; Turner, C. Towards superhydrophobic coatings made by non-fluorinated polymers sprayed from a supercritical solution. The Journal of Supercritical Fluids 2013, 77, 134–141. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Vasylyshyn, T.; Patsula, V.; Filipová, M.; Konefal, R.L.; Horák, D. Poly(glycerol monomethacrylate)-encapsulated upconverting nanoparticles prepared by miniemulsion polymerization: morphology, chemical stability, antifouling properties and toxicity evaluation. Nanoscale Adv. 2023, 5, 6979–6989. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Lv, C.; Liao, X.; Zou, F.; Tang, W.; Xing, S.; Li, G. Generating porous polymer microspheres with cellular surface via a gas-diffusion confined scCO2 foaming technology to endow the super-hydrophobic coating with hierarchical roughness. Chemical Engineering Journal 2022, 442, 136192. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Zhu, H.; Wang, W.; Wang, Y.; Lin, Z.; Ji, H.; Chen, X.; Li, G.; Ma, Y.; Xie, L. Preparation of PP/PC Light-Diffusing Materials with UV-Shielding Property. Polymer Composites 2023, 44, 5553–5566. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Zhang, A.; Zhang, Q.; Bai, H.; Li, L.; Li, J. Polymeric nanoporous materials fabricated with supercritical CO 2 and CO 2-expanded liquids. Chemical Society Reviews 2014, 43, 6938–6953. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Barroso, T.; Temtem, M.; Casimiro, T.; Aguiar-Ricardo, A. Development of pH-responsive poly(methylmethacrylate-co-methacrylic acid) membranes using scCO2 technology. Application to protein permeation. The Journal of Supercritical Fluids 2009, 51, 57–66. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Scholes, C.A.; Kanehashi, S. Polymeric membrane gas separation performance improvements through supercritical CO2 treatment. Journal of Membrane Science 2018, 566, 239–248. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Ratcharak, O.; Sane, A. Surface coating with poly(trifluoroethyl methacrylate) through rapid expansion of supercritical CO2 solutions. The Journal of Supercritical Fluids 2014, 89, 106–112. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Leitner, W. Designed to dissolve. Nature 2000, 405, 129–130. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Zhang, X.; Heinonen, S.; Levänen, E. Applications of supercritical carbon dioxide in materials processing and synthesis. RSC Advances 2014, 4, 61137–61152. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Tomasko, D.L.; Li, H.; Liu, D.; Han, X.; Wingert, M.J.; Lee, L.J.; Koelling, K.W. A Review of CO2 Applications in the Processing of Polymers. Industrial & Engineering Chemistry Research 2003, 42, 6431–6456. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Tutek, K.; Masek, A.; Kosmalska, A.; Cichosz, S. Application of Fluids in Supercritical Conditions in the Polymer Industry. Polymers 2021, 13, 729. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Kortsen, K.; Fowler, H.R.; Jacob, P.L.; Krumins, E.; Lentz, J.C.; Souhil, M.R.; Taresco, V.; Howdle, S.M. Exploiting the tuneable density of scCO2 to improve particle size control for dispersion polymerisations in the presence of poly(dimethyl siloxane) stabilisers. European Polymer Journal 2022, 168, 111108. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Hakuta, Y.; Hayashi, H.; Arai, K. Fine particle formation using supercritical fluids. Current Opinion in Solid State and Materials Science 2003, 7, 341–351. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Yan, H.; Sato, T.; Komago, D.; Yamaguchi, A.; Oyaizu, K.; Yuasa, M.; Otake, K. Electrochemical Synthesis of a Polypyrrole Thin Film with Supercritical Carbon Dioxide as a Solvent. Langmuir 2005, 21, 12303–12308. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Medina-Gonzalez, Y.; Camy, S.; Condoret, J.S. scCO2/Green Solvents: Biphasic Promising Systems for Cleaner Chemicals Manufacturing. ACS Sustainable Chemistry & Engineering 2014, 2, 2623–2636. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Wood, C.D.; Tan, B.; Zhang, H.; Cooper, A.I. Chapter 21 - Supercritical Carbon Dioxide as a Green Solvent for Polymer Synthesis. In Thermodynamics, Solubility and Environmental Issues; Letcher, T.M., Ed.; Elsevier: Amsterdam, 2007; pp. 383–396. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Khanyile, A.; Andrew, J.; Paul, V.; Sithole, B. A comparative study of supercritical fluid extraction and accelerated solvent extraction of lipophilic compounds from lignocellulosic biomass. Sustainable Chemistry and Pharmacy 2022, 26, 100608. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- do Espirito Santo, A.T.; Siqueira, L.M.; Almeida, R.N.; Vargas, R.M.F.; do N Franceschini, G.; Kunde, M.A.; Cappellari, A.R.; Morrone, F.B.; Cassel, E. Decaffeination of yerba mate by supercritical fluid extraction: Improvement, mathematical modelling and infusion analysis. The Journal of Supercritical Fluids 2021, 168, 105096. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Marco, I.D.; Riemma, S.; Iannone, R. Supercritical Carbon Dioxide Decaffeination Process: a Life Cycle Assessment Study. Chemical Engineering Transactions 2017, 57, 1699–1704. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Zhang, H.; Huang, T.; Liao, X.; Zhou, Y.; Chen, S.; Chen, J.; Xiong, W. Extraction of Camphor Tree Essential Oil by Steam Distillation and Supercritical CO2 Extraction. Molecules 2022, 27. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Yıldırım, M.; Erşatır, M.; Poyraz, S.; Amangeldinova, M.; Kudrina, N.O.; Terletskaya, N.V. Green Extraction of Plant Materials Using Supercritical CO2: Insights into Methods, Analysis, and Bioactivity. Plants 2024, 13. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Handy, K.; Tepper, G.C. Incorporation of Poly(TFEMA) in Perovskite Thin Films Using a Supercritical Fluid. Molecules 2023, 28. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- von Schnitzler, J.; Eggers, R. Mass transfer in polymers in a supercritical CO2-atmosphere. Journal of Supercritical Fluids 1999, 16, 81–92. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Furtado, A.I.; Bonifácio, V.D.B.; Viveiros, R.; Casimiro, T. Design of Molecularly Imprinted Polymers Using Supercritical Carbon Dioxide Technology. Molecules 2024, 29, 926. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Naguib, H.E.; Park, C.B.; Song, S.W. Effect of Supercritical Gas on Crystallization of Linear and Branched Polypropylene Resins with Foaming Additives. Industrial & Engineering Chemistry Research 2005, 44, 6685–6691. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Luna-Bárcenas, G.; Mawson, S.; Takishima, S.; DeSimone, J.M.; Sanchez, I.C.; Johnston, K.P. Phase behavior of poly(1,1-dihydroperfluorooctylacrylate) in supercritical carbon dioxide. Fluid Phase Equilibria 1998, 146, 325–337. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Blackburn, J.M.; Long, D.P.; Cabañas, A.; Watkins, J.J. Deposition of Conformal Copper and Nickel Films from Supercritical Carbon Dioxide. Science 2001, 294, 141–145. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Cabañas, A.; Long, D.P.; Watkins, J.J. Deposition of Gold Films and Nanostructures from Supercritical Carbon Dioxide. Chemistry of Materials 2004, 16, 2028–2033. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Rasadujjaman, M.; Watanabe, M.; Kondoh, E. Codeposition of Cu/Ni thin films from mixed precursors in supercritical carbon dioxide solutions. Japanese Journal of Applied Physics 2014, 53, 5–7. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Pandiyarajan, S.; Hsiao, P.J.; Liao, A.H.; Ganesan, M.; Manickaraj, S.S.M.; Lee, C.T.; Huang, S.T.; Chuang, H.C. Influence of ultrasonic combined supercritical-CO2 electrodeposition process on copper film fabrication: Electrochemical evaluation. Ultrasonics Sonochemistry 2021, 74, 105555. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Ganesan, M.; Liu, C.C.; Pandiyarajan, S.; Lee, C.T.; Chuang, H.C. Post-supercritical CO2 electrodeposition approach for Ni-Cu alloy fabrication: An innovative eco-friendly strategy for high-performance corrosion resistance with durability. Applied Surface Science 2022, 577, 151955. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Hosokawa, S.; Tomita, E.; Kanehashi, S.; Ogino, K. Study on effect of supercritical CO2 on structural ordering and charge transporting property in thiophene-based block copolymer. Japanese Journal of Applied Physics 2022, 61, 021001. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Marie Sajfrtová, Marie Cerhová, V. J.V.D.S.D.L.M. The effect of type and concentration of modifier in supercritical carbon dioxide on crystallization of nanocrystalline titania thin films. The Journal of Supercritical Fluids 2018, 133, 211–217. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Wei, M.; Wang, K.; Yanagida, M.; Sugihara, H.; Morris, M.A.; Holmes, J.D.; Zhou, H. Supercritical fluid processing of mesoporous crystalline TiO2 thin films for highly efficient dye-sensitized solar cells. Journal of Materials Chemistry 2007, 17, 3888–3893. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Sanli, D.; Bozbag, S.E.; Erkey, C. Synthesis of nanostructured materials using supercritical CO2: Part I. Physical transformations. Journal of Materials Science 2012, 47, 2995–3025. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Kaleva, A.; Heinonen, S.; Nikkanen, J.P.; Levänen, E. Synthesis and Crystallization of Titanium Dioxide in Supercritical Carbon Dioxide (scCO2). In Proceedings of the IOP Conference Series: Materials Science and Engineering. IOP Publishing, Vol. 175; 2017; p. 012034. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Wei, T.Y.; Chen, C.H.; Chien, H.C.; Lu, S.Y.; Hu, C.C. A Cost-Effective Supercapacitor Material of Ultrahigh Specific Capacitances: Spinel Nickel Cobaltite Aerogels from an Epoxide-Driven Sol-Gel Process. Advanced Materials 2010, 22, 347–351. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Pu, N.W.; Wang, C.A.; Sung, Y.; Liu, Y.M.; Ger, M.D. Production of few-layer graphene by supercritical CO2 exfoliation of graphite. Materials Letters 2009, 63, 1987–1989. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Wang, Y.; Zhou, C.; Wang, W.; Zhao, Y. Preparation of Two Dimensional Atomic Crystals-BN, WS2 and MoS2 by Supercritical CO2 Assisted with Ultrasonic. Industrial & Engineering Chemistry Research. [CrossRef]

- Rindfleisch, F.; DiNoia, T.P.; McHugh, M.A. Solubility of Polymers and Copolymers in Supercritical CO2. The Journal of Physical Chemistry 1996, 100, 15581–15587. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Ekart, M.P.; Bennett, K.L.; Ekart, S.M.; Gurdial, G.S.; Liotta, C.L.; Eckert, C.A. Cosolvent Interactions in Supercritical Fluid Solutions. AIChE Journal 1993, 39, 235–248. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Beckman, E.J. Supercritical and near-critical CO2 in green chemical synthesis and processing. The Journal of Supercritical Fluids 2004, 28, 121–191. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Ting, Y.S.; Hsieh, C.M. Prediction of solid solute solubility in supercritical carbon dioxide with organic cosolvents from the PR+COSMOSAC equation of state. Fluid Phase Equilibria 2016. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Ren, H.; Song, J.; Xu, Q.; Yin, J. Solubility of the silver nitrate in supercritical carbon dioxide with ethanol and ethylene glycol as double cosolvents: Experimental determination and correlation. Chinese Journal of Chemical Engineering 2018. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Gurina, D.L.; Antipova, M.L.; Odintsova, E.G.; Petrenko, V.E. The study of peculiarities of parabens solvation in methanol- and acetone-modified supercritical carbon dioxide by computer simulation. The Journal of Supercritical Fluids 2017, xxx, xxx–xxx. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Tomasko, D.L.; Knutson, B.L.; Pouillot, F.; Liotta, C.L.; Eckert, C.A. Spectroscopic study of structure and interactions in cosolvent-modified supercritical fluids. The Journal of Physical Chemistry 1993, 97, 11823–11834. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Yang, H.; Zhong, C. Modeling of the solubility of aromatic compounds in supercritical carbon dioxide–cosolvent systems using SAFT equation of state. Journal of Supercritical Fluids 2005, 33, 99–106. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Zhang, G.; Wu, T.; Li, J.; Pang, Q.; Yang, H.; Liu, G.; Huang, H.; Zhu, Y. Dynamics Simulation of the Effect of Cosolvent on the Solubility and Tackifying Behavior of PDMS Tackifier in Supercritical CO2 Fracturing Fluid. Colloids and Surfaces A: Physicochemical and Engineering Aspects 2023, 662, 130985. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Haifei Zhang, Zhimin Liu, B. H. Critical points and phase behavior of toluene-CO2 and toluene-H2-CO2 mixture in CO2-rich region. Journal of Supercritical Fluids 2000, 18, 185–192. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Hiroaki Matsukawa, Tomoya Tsuji, K. O. Measurement of the Density of Carbon Dioxide/Toluene Homogeneous Mixtures and Correlation with Equations of State. Journal of Chemical Thermodynamics 2022, 164, 106618. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Jialong Wu, Qinmin Pan, G. L.R. Pressure-Density-Temperature Behavior of CO2/Acetone, CO2/Toluene, and CO2/Monochlorobenzene Mixtures in the Near-Critical Region. Journal of Chemical and Engineering Data 2004, 49, 976–979. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Rowane, A.J.; Mallepally, R.R.; Bamgbade, B.A.; Newkirk, M.S.; Baled, H.O.; Burgess, W.A.; Gamwo, I.K.; Tapriyal, D.; Enick, R.M.; McHugh, M.A. High-temperature, high-pressure viscosities and densities of toluene. The Journal of Chemical Thermodynamics 2017, 115, 34–46. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Pitzer, K.S.; Schreiber, D.R. Improving equation-of-state accuracy in the critical region; equations for carbon dioxide and neopentane as examples. Fluid Phase Equilibria 1988, 41, 1–17. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Ameduri, B. Fluoropolymers: the right material for the right applications. Chemistry–A European Journal 2018, 24, 18830–18841. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Ciardelli, F.; Rubino, G.; Ranieri, G.; Licciulli, A.; Laviano, R. Fluorinated polymeric materials for the protection of monumental buildings. Macromolecular Symposia 2000, 152, 211–222. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Leivo, E.; Wilenius, T.; Kinos, T.; Vuoristo, P.; Mäntylä, T. Properties of thermally sprayed fluoropolymer PVDF, ECTFE, PFA and FEP coatings. Progress in Organic Coatings 2004, 49, 69–73. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Kwon, S.; Bae, W.; Lee, K.; Byun, H.S.; Kim, H. High Pressure Phase Behavior of Carbon Dioxide + 2,2,2-Trifluoroethyl Methacrylate and + Poly(2,2,2-trifluoroethyl methacrylate) Systems. Journal of Chemical & Engineering Data 2007, 52, 89–92. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Kwon, S.; Bae, W.; Kim, H. The Effect of CO2 in Free-radical Polymerization of 2,2,2-Trifluoroethyl Methacrylate. Korean Journal of Chemical Engineering 2004, 21, 910–914. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Zelaya, J.R.; Tepper, G.C. Cloud Point Behavior of Poly(trifluoroethyl methacrylate) in Supercritical CO2–Toluene Mixtures. Molecules 2025, 30. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Byun, H.S.; Kim, C.R.; Yoon, S.D. Cloud-point measurement of binary and ternary mixtures for the P(MMA-co-PnFPA) in supercritical fluoric solvents. The Journal of Supercritical Fluids 2017, 120, 226–239. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- An-hou Xu, Lu-qing Zhang, J. c.M.Y.m.M.B.G.S.x.Z. Preparation and surface properties of poly(2,2,2-trifluoroethyl methacrylate) coatings modified with methyl acrylate. Journal of Coatings Technology and Research 2016, 13, 795–804. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Annohene, G.; Tepper, G. Moisture Stability of Perovskite Solar Cells Processed in Supercritical Carbon Dioxide. Molecules 2021, 26, 7570. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Annohene, G.; Tepper, G.C. Efficient perovskite solar cells processed in supercritical carbon dioxide. The Journal of Supercritical Fluids 2021, 171, 105203. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Annohene, G.; Pascucci, J.; Pestov, D.; Tepper, G.C. Supercritical fluid-assisted crystallization of CH3NH3PbI3 perovskite films. The Journal of Supercritical Fluids 2020, 156, 104684. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Annohene, G.; Tepper, G.C. Low temperature formation of CH3NH3PbI3 perovskite films in supercritical carbon dioxide. Journal of Supercritical Fluids 2019, 154, 104604. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Oxtoby, D.W. Homogeneous nucleation: theory and experiment. Journal of Physics: Condensed Matter 1992, 4, 7627. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Kalikmanov, V.I., Classical Nucleation Theory. In Nucleation Theory; Springer Netherlands: Dordrecht, 2013; pp. 17–41. [CrossRef]

- Kashchiev, D. Nucleation; Elsevier, 2000.

- Kalikmanov, V.I., Heterogeneous Nucleation. In Nucleation Theory; Springer Netherlands: Dordrecht, 2013; pp. 253–276 [CrossRef]

- Liu, X. Heterogeneous nucleation or homogeneous nucleation? The Journal of Chemical Physics 2000, 112, 9949–9955. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Lifshitz, I.M.; Slyozov, V.V. The kinetics of precipitation from supersaturated solid solutions. Journal of physics and chemistry of solids 1961, 19, 35–50. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

| Temperature (K) | Cloud point pressure (MPa) | ||

|---|---|---|---|

| 2 wt% poly(TFEMA) | 3 wt% poly(TFEMA)a | 5 wt% poly(TFEMA) | |

| 304.65 | 18.35 | 18.52 | 19.17 |

| 308.15 | 20.78 | 20.84 | 20.87 |

| 313.15 | 23.05 | 23.32 | 23.46 |

| 318.15 | 24.97 | 25.38 | 25.85 |

| 323.15 | 27.01 | 27.37 | 27.92 |

| a 3 wt% values from our previous publication [60] | |||

| Pressure (MPa) | Classification |

|---|---|

| 15.86 | One-phase |

| 12.37 | Cloud point |

| 8.96 | Two-phase |

| Regime | P (MPa) | (kg ) | (g) | (g) | (mL) | (g) |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| One-phase | 15.86 | 793.8639 | 337.3009 | 85.3926 | 99.0289 | 4.2696 |

| Cloud point | 12.37 | 729.1488 | 309.8044 | 78.4314 | 90.9562 | 3.9216 |

| Two-phase | 8.96 | 477.8338 | 203.0244 | 51.3990 | 59.6064 | 2.5699 |

Disclaimer/Publisher’s Note: The statements, opinions and data contained in all publications are solely those of the individual author(s) and contributor(s) and not of MDPI and/or the editor(s). MDPI and/or the editor(s) disclaim responsibility for any injury to people or property resulting from any ideas, methods, instructions or products referred to in the content. |

© 2025 by the authors. Licensee MDPI, Basel, Switzerland. This article is an open access article distributed under the terms and conditions of the Creative Commons Attribution (CC BY) license (http://creativecommons.org/licenses/by/4.0/).