1. Introduction

Carbon dioxide (CO

2) is said to be the gas that has the greatest impact on global warming [

1,

2,

3]. Since the Industrial Revolution [

4], CO

2 emissions have continued to increase due to the large-scale use of fossil fuels such as oil, coal, and natural gas. In particular, high-concentration CO

2 is contained in large quantities in exhaust gas from thermal power plants and factories. Amine absorption has long been used as a method to capture CO

2 from the exhaust gas of high CO

2 concentration and reduce carbon emissions [

5,

6]. However, simply capturing CO

2 from exhaust gas is not enough to achieve carbon neutrality by 2050 [

7]. It is essential to capture CO

2 that has been released into the atmosphere in the past and make it carbon negative. Therefore, direct air capture (DAC) [

8] has attracted attention as a technology that can directly capture CO

2 already emitted into the atmosphere.

DAC is a technology that adsorbs very dilute CO

2 in the atmosphere (currently around 400 ppm) onto an adsorbent and then captures it by heating and reducing pressure. After capturing CO

2, methods such as highly concentrating it and storing it underground using CCS (Carbon Capture and Storage) technology can be applied. Presently, the most promising approach for DAC is to apply liquid amines to porous materials such as mesoporous silica [

9]. The high specific surface area of porous materials allows the chemical adsorption of amines to work more effectively [

10]. In addition, applying liquid amines to porous materials allows them to be treated like solid materials. However, amines have problems such as being easily volatilized at high temperatures, being easily washed away by moisture, having low heat resistance, and being easily oxidized [

11,

12]. This is because liquid amines generally contain a large number of primary amines, which have low molecular weights and are easily degraded by oxidation reactions. In addition, primary amines are highly reactive and easily adsorb CO

2, but they require high energy for desorption due to their high desorption temperature [

13].

In our previous reports, the fabrication of amine–epoxy/poly(vinyl alcohol) (AE/PVA) fibers with an average diameter of approximately 400 nm was achieved via in situ thermal curing during the electrospinning process [

14]. Alternatively, the AE/PVA nanofibers were successfully prepared without the need for inline heating by controlling the B-stage of the amine–epoxy reaction. The resulting fibers exhibited diameters ranging from 500 to 700 nm. Using a varnish solution with a low B-stage degree, it was difficult to maintain the fibrous morphology through electrospinning alone, and inline thermal curing was required [

15].

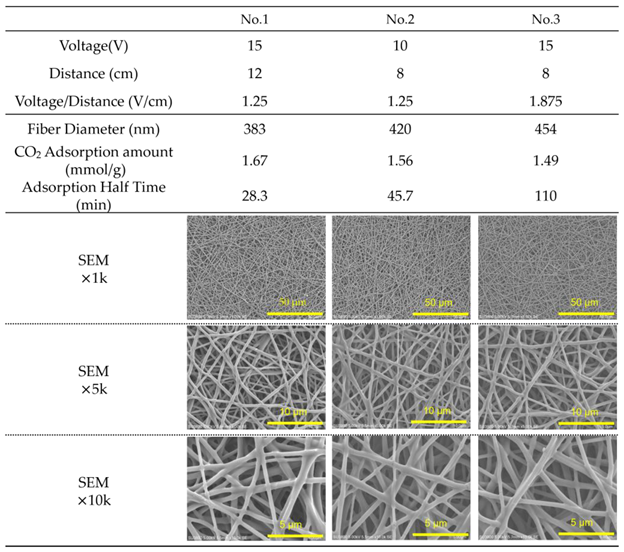

In this report, we investigated the effect of fiber diameter, epoxy-to-amine ratio (E/A), and degree of PVA Saponification on CO₂ adsorption properties of AE/PVA nanofiber webs prepared through electrospinning to explore the optimum conditions for fabricating the absorbent for DAC. Firstly, we investigated how variations in electrospinning conditions and formulation of AE/PVA nanofibers influence their CO₂ adsorption performance. For neat PVA materials, it has been reported that fiber diameter can be controlled by adjusting the concentration of the aqueous PVA solution, applied voltage, and the distance between the nozzle and the collector [

16,

17]. Based on this, the authors employed the same spinning solution for the AE/PVA system and systematically varied the applied voltage and the syringe-to-collector distance to examine their effects on fiber diameter and CO₂ adsorption behavior.

Furthermore, the authors explored the effect of varying the E/A from 0.3 to 0.55, which had previously been fixed at 0.5 to balance thermal stability and adsorption/desorption kinetics. Prior studies have shown that the E/A influences a trade-off among adsorption capacity, adsorption rate, and low-temperature desorption, depending on the degree of amine substitution.

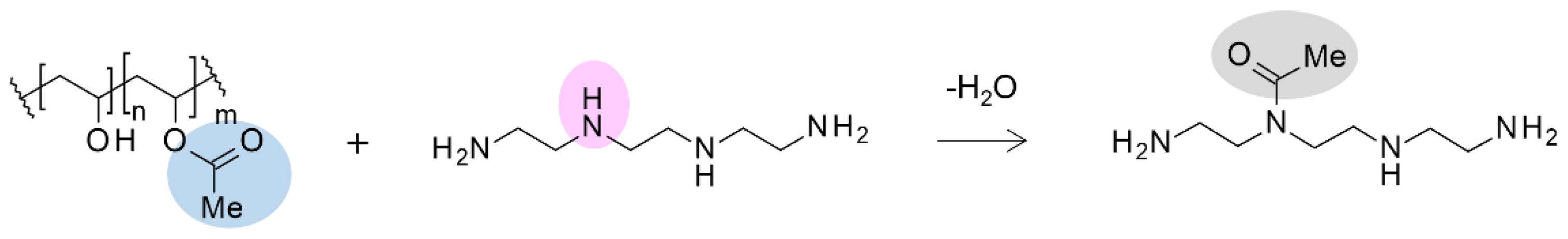

Lastly, the authors also examined the influence of the degree of saponification of PVA, which was introduced to improve spinnability. The terminal group composition of PVA varies depending on its degree of saponification, with lower saponification resulting in a higher proportion of acetate groups. It is known that under thermal conditions, such as in-situ thermal-curing in the spinning process or heat treatment of prepared webs, these acetate groups react with secondary amines to form amide bonds [

18,

19,

20].

4. Discussion

This study revealed that CO₂ adsorption behavior in AE/PVA nanofibers is governed by multiple interrelated factors—namely, fiber diameter, the epoxy-to-amine ratio (E/A), and the degree of PVA saponification. These findings elucidate the design principles for optimizing sorbent performance in direct air capture (DAC) applications.

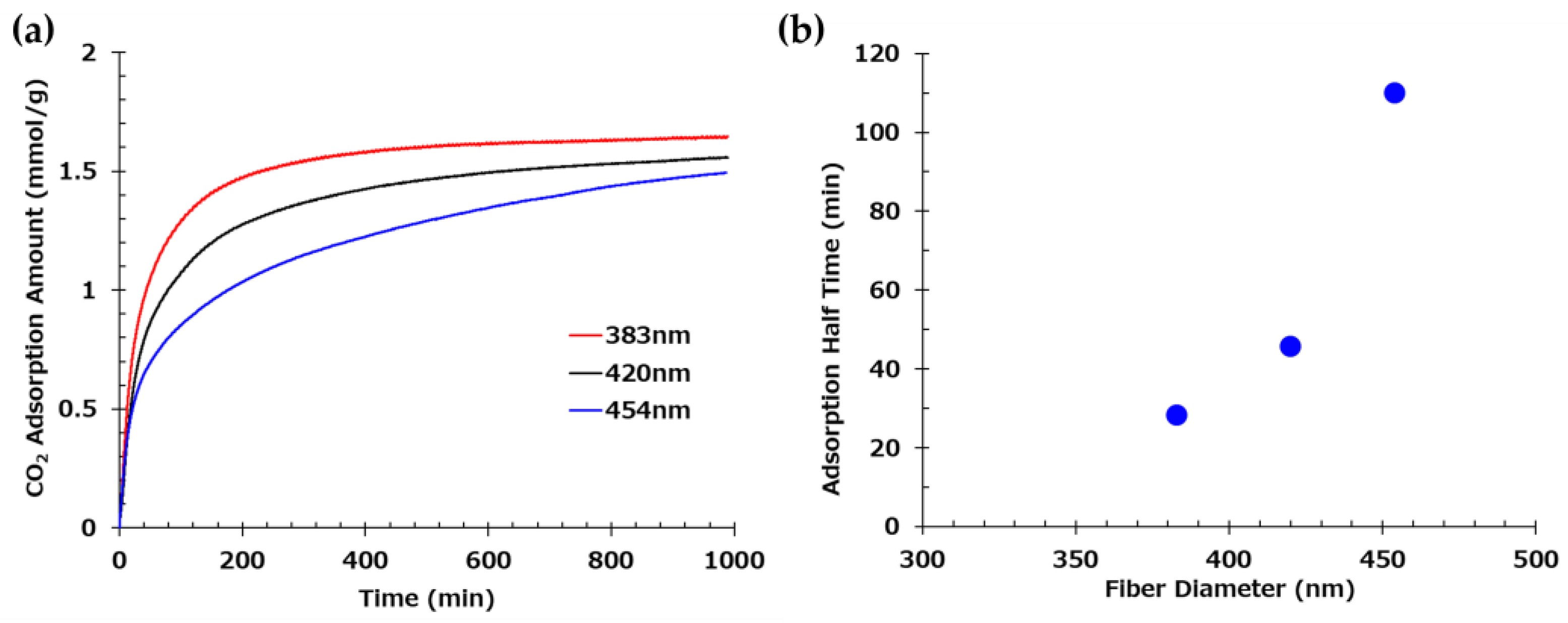

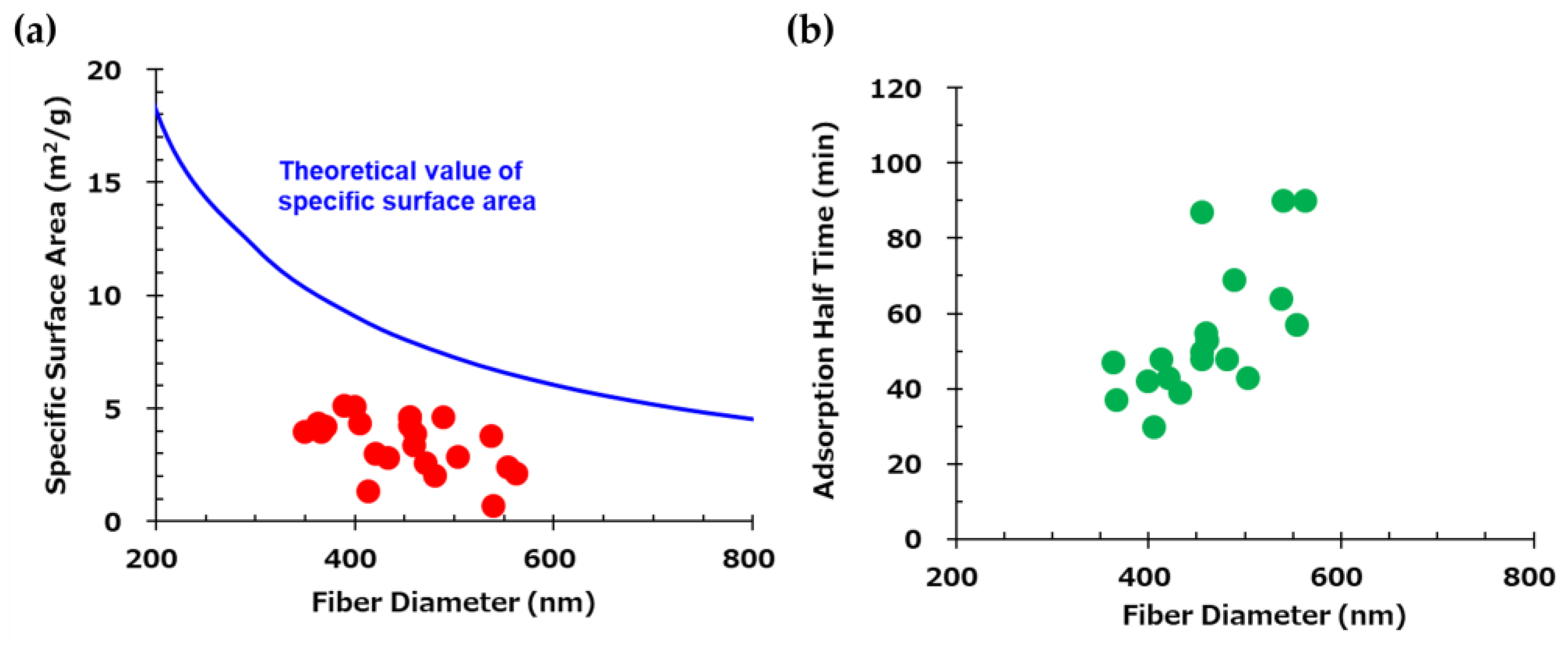

The influence of fiber diameter was particularly evident in the CO₂ adsorption rate. Finer nanofibers exhibited accelerated adsorption due to their higher specific surface area and enhanced exposure of amine functionalities. The correlation between fiber diameter and adsorption kinetics, including adsorption half-time, underscores the advantage of producing homogeneously thin fibers. However, the measured BET surface areas were significantly lower than theoretical predictions, suggesting that morphological factors such as fiber adhesion and diameter distribution limit accessible surface area, an issue warranting further process refinement.

The modulation of the E/A demonstrated a classic trade-off in amine-based sorbents. Lower E/A, which retains more primary amines, yielded fast adsorption but poor low-temperature desorption characteristics, while higher E/A (up to 0.5) facilitated secondary amine formation, achieving better desorption behavior and oxidative stability. E/A = 0.5 was identified as the optimal condition, balancing kinetic performance, desorption efficiency, and material stability.

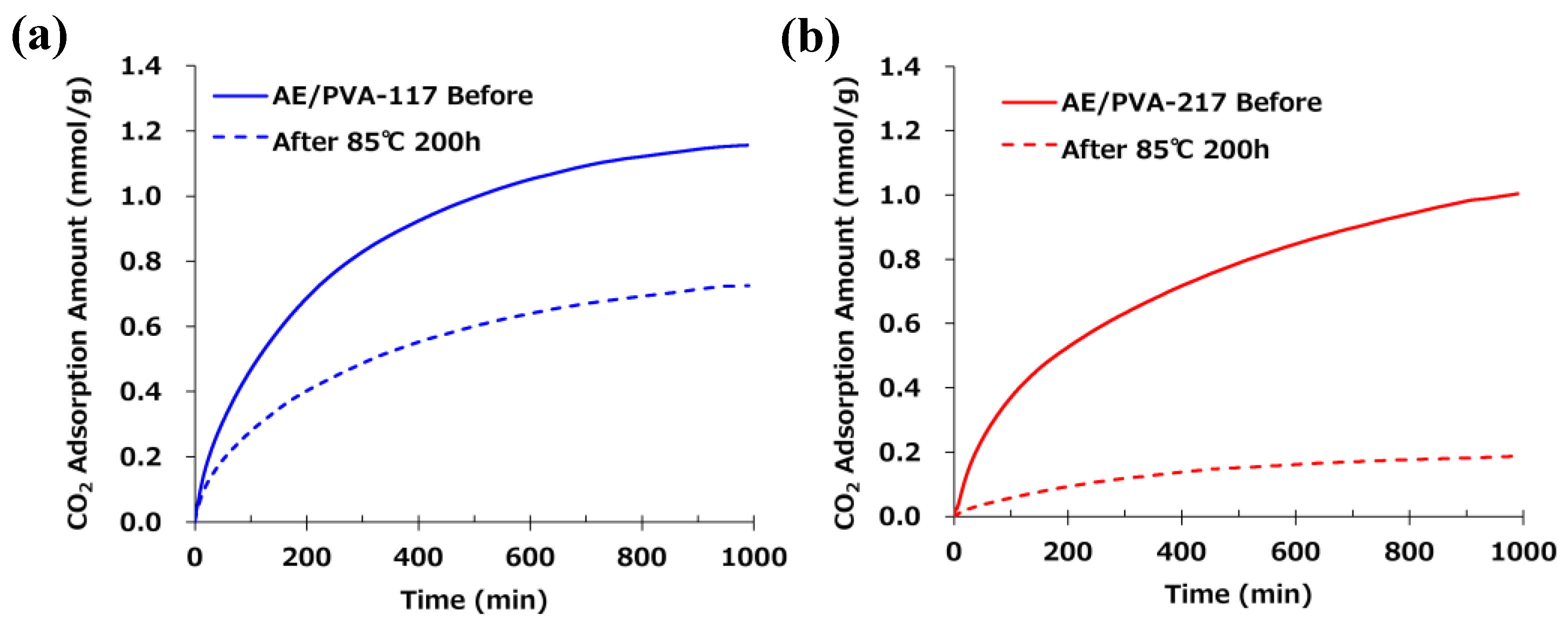

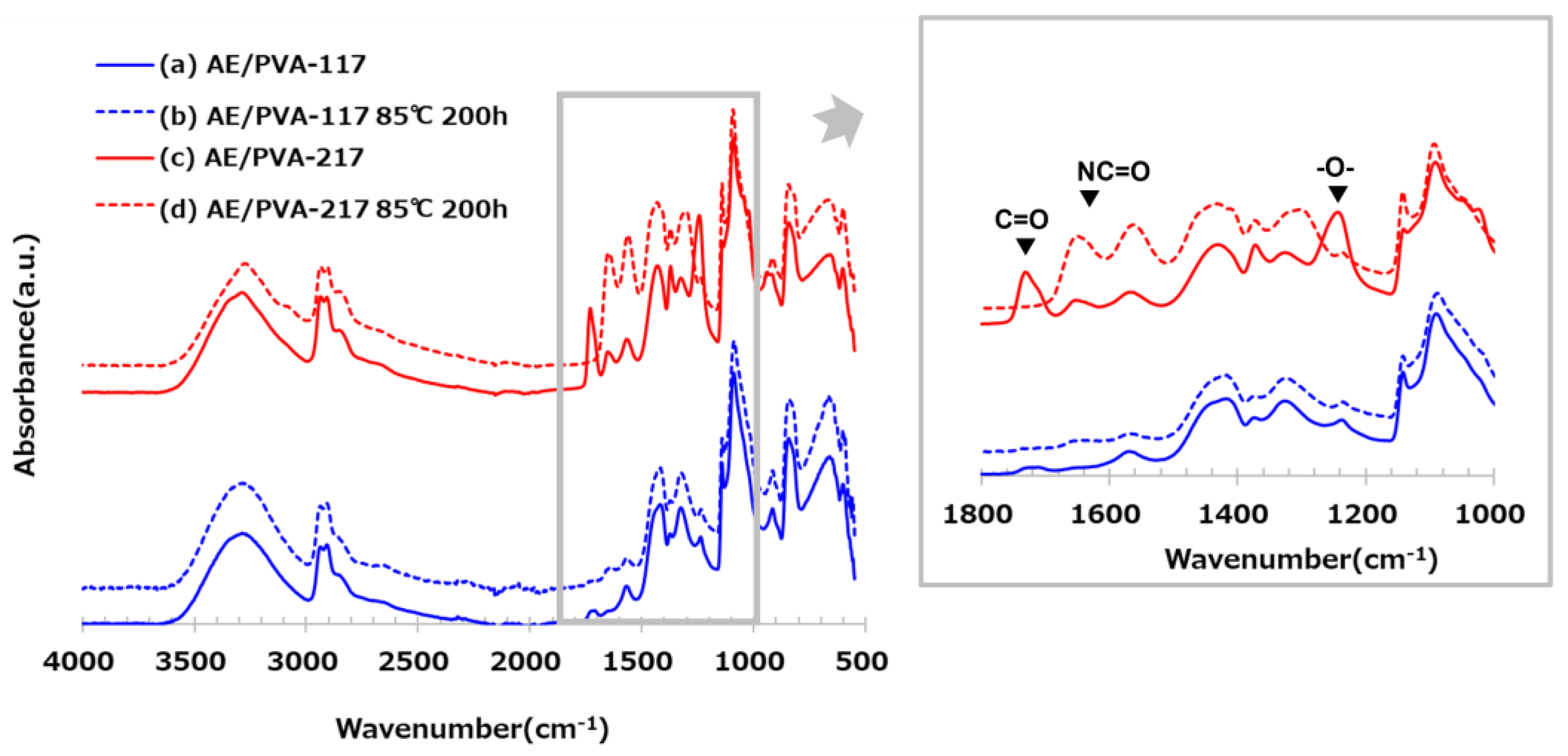

Additionally, the degree of PVA saponification played a critical role in long-term thermal durability. The presence of residual acetate groups in lower-saponified PVA led to amide bond formation with secondary amines during heat treatment, as evidenced by FT-IR analysis. This undesirable side reaction decreased the available amine sites for CO₂ capture. Consequently, highly saponified PVA-117 was deemed the superior spinnability enhancer due to its chemical inertness and compatibility.

Collectively, the interplay between formulation and processing conditions has a decisive impact on sorbent performance. Tailoring these parameters allows for strategic enhancement of DAC efficiency, underscoring the material’s potential for scalable deployment.

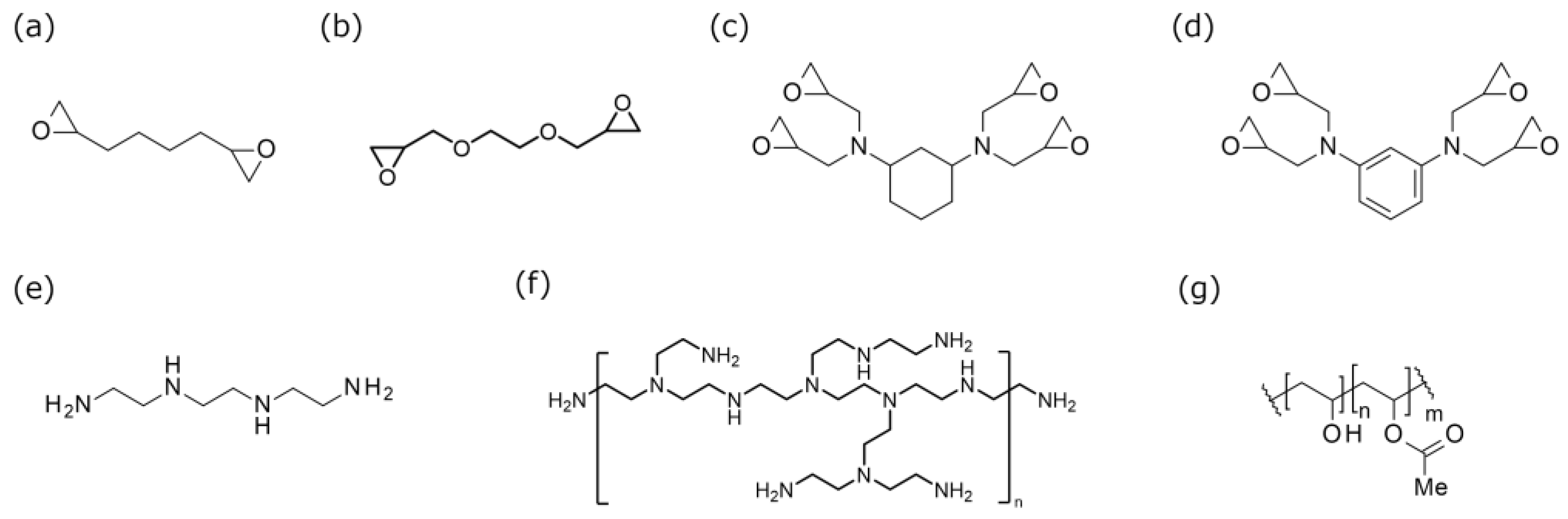

Figure 1.

Chemical structural formula of (a) 1,7-octadiene diepoxide (ODE), (b) ethylene glycol diglycidyl ether (EDE), (c) 1,3-bis (N,N-diglycidyl aminomethyl) cyclohexane (T-C), (d) N,N,N’,N‘,-tetraglycidyl-m-xylenediamine (T-X), (e) triethylenetetramine (TETA), (f) polyethyleneimine (PEI), and (g) poly(vinyl alcohol) (PVA).

Figure 1.

Chemical structural formula of (a) 1,7-octadiene diepoxide (ODE), (b) ethylene glycol diglycidyl ether (EDE), (c) 1,3-bis (N,N-diglycidyl aminomethyl) cyclohexane (T-C), (d) N,N,N’,N‘,-tetraglycidyl-m-xylenediamine (T-X), (e) triethylenetetramine (TETA), (f) polyethyleneimine (PEI), and (g) poly(vinyl alcohol) (PVA).

Figure 2.

Schematic illustration of the electrospinning apparatus. A heat gun is positioned between the syringe and the collector, angled at 45°, to direct heat toward the fiber formation zone. Fibers are collected on a cylindrical collector.

Figure 2.

Schematic illustration of the electrospinning apparatus. A heat gun is positioned between the syringe and the collector, angled at 45°, to direct heat toward the fiber formation zone. Fibers are collected on a cylindrical collector.

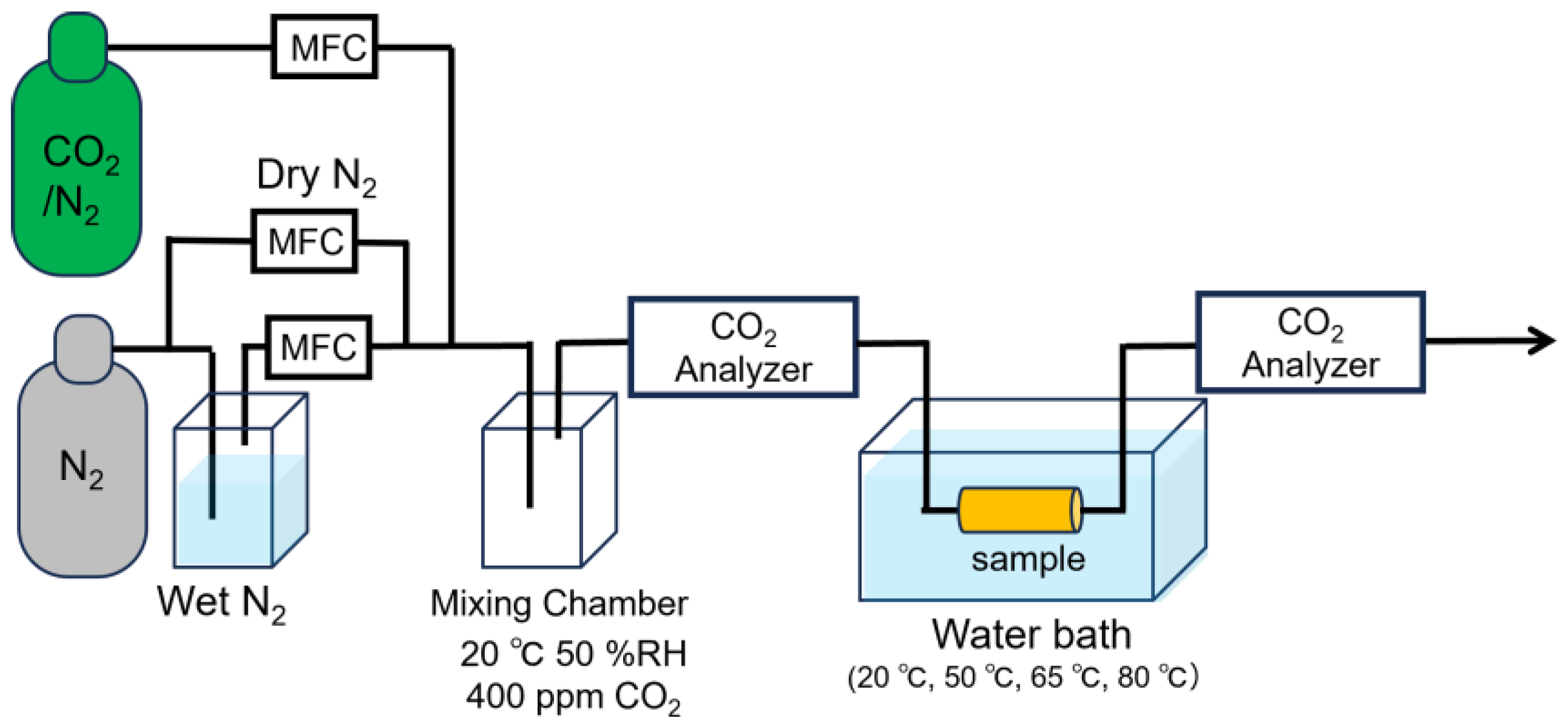

Figure 3.

Schematic diagram of the CO₂ adsorption test apparatus. Gas cylinders containing 10% CO₂/N₂ and pure N₂ are connected to mass flow controllers (MFCs). The gases are bubbled and mixed in a mixing chamber to produce a humidified gas stream at 20 °C and 50% relative humidity (RH), with a CO₂ concentration of 400 ppm. This gas is delivered to a sample placed in a water bath maintained at 20 °C, 50 °C, 65 °C, or 80 °C. CO2 concentrations are monitored before and after the sample using CO₂ analyzers.

Figure 3.

Schematic diagram of the CO₂ adsorption test apparatus. Gas cylinders containing 10% CO₂/N₂ and pure N₂ are connected to mass flow controllers (MFCs). The gases are bubbled and mixed in a mixing chamber to produce a humidified gas stream at 20 °C and 50% relative humidity (RH), with a CO₂ concentration of 400 ppm. This gas is delivered to a sample placed in a water bath maintained at 20 °C, 50 °C, 65 °C, or 80 °C. CO2 concentrations are monitored before and after the sample using CO₂ analyzers.

Figure 4.

(a) Time-dependent CO₂ adsorption profiles of three web samples with distinct fiber diameters. Measurements were conducted for samples with mean fiber diameters of 383 nm, 420 nm, and 454 nm. (b) Correlation between fiber diameter and CO₂ adsorption half-time.

Figure 4.

(a) Time-dependent CO₂ adsorption profiles of three web samples with distinct fiber diameters. Measurements were conducted for samples with mean fiber diameters of 383 nm, 420 nm, and 454 nm. (b) Correlation between fiber diameter and CO₂ adsorption half-time.

Figure 5.

(a) Theoretical and experimental values of specific surface area as a function of fiber diameter. The blue curve represents the theoretical values calculated assuming a material density of 1.1 g/cm³. Red points indicate experimentally measured values. (b) Correlation between mean fiber diameter and CO₂ adsorption half-time.

Figure 5.

(a) Theoretical and experimental values of specific surface area as a function of fiber diameter. The blue curve represents the theoretical values calculated assuming a material density of 1.1 g/cm³. Red points indicate experimentally measured values. (b) Correlation between mean fiber diameter and CO₂ adsorption half-time.

Figure 6.

CO₂ adsorption and desorption profiles of fiber samples prepared with different epoxy-to-amine ratios (E/A). The adsorption amount is plotted as a function of time for E/A of 0.3 (red), 0.4 (green), 0.5 (black), and 0.55 (blue). The temperature was varied at 20 °C for 990 min for adsorption, and at 50 °C, 65 °C, and 80 °C for desorption for 90 min each (For E/A=0.3, 110 min at 50 °C).

Figure 6.

CO₂ adsorption and desorption profiles of fiber samples prepared with different epoxy-to-amine ratios (E/A). The adsorption amount is plotted as a function of time for E/A of 0.3 (red), 0.4 (green), 0.5 (black), and 0.55 (blue). The temperature was varied at 20 °C for 990 min for adsorption, and at 50 °C, 65 °C, and 80 °C for desorption for 90 min each (For E/A=0.3, 110 min at 50 °C).

Figure 7.

(a) CO₂ adsorption profiles of AE/PVA-117 before and after heat treatment. The solid blue line represents the original AE/PVA-117 sample, while the dashed blue line corresponds to the sample after heat treatment at 85 °C for 200 hours. (b) CO₂ adsorption profiles of AE/PVA-217 before and after heat treatment. The solid red line represents the original AE/PVA-217 sample, while the dashed red line corresponds to the sample after heat treatment at 85 °C for 200 hours.

Figure 7.

(a) CO₂ adsorption profiles of AE/PVA-117 before and after heat treatment. The solid blue line represents the original AE/PVA-117 sample, while the dashed blue line corresponds to the sample after heat treatment at 85 °C for 200 hours. (b) CO₂ adsorption profiles of AE/PVA-217 before and after heat treatment. The solid red line represents the original AE/PVA-217 sample, while the dashed red line corresponds to the sample after heat treatment at 85 °C for 200 hours.

Figure 8.

FT-IR spectra of AE/PVA-117 (blue) and AE/PVA-217 (red) before and after heat treatment. Solid lines represent the original samples, and dashed lines correspond to samples after heat treatment at 85 °C for 200 hours. Enlarged FT-IR spectra of AE/PVA-117 and AE/PVA-217 in the range of 1800–1000 cm⁻¹ are inserted to highlight characteristic absorption bands. Peaks corresponding to C=O (~1700 cm⁻¹), NC=O (~1500 cm⁻¹), and –O– (~1200 cm⁻¹) are annotated.

Figure 8.

FT-IR spectra of AE/PVA-117 (blue) and AE/PVA-217 (red) before and after heat treatment. Solid lines represent the original samples, and dashed lines correspond to samples after heat treatment at 85 °C for 200 hours. Enlarged FT-IR spectra of AE/PVA-117 and AE/PVA-217 in the range of 1800–1000 cm⁻¹ are inserted to highlight characteristic absorption bands. Peaks corresponding to C=O (~1700 cm⁻¹), NC=O (~1500 cm⁻¹), and –O– (~1200 cm⁻¹) are annotated.

Figure 9.

Proposed reaction mechanism between the acetate groups in the PVA-based polymer and the amine groups in the curing agent. The reaction leads to the formation of amide bonds, R–C(=O) –N(–R’)–R”, as suggested by FT-IR spectral changes observed after heat treatment.

Figure 9.

Proposed reaction mechanism between the acetate groups in the PVA-based polymer and the amine groups in the curing agent. The reaction leads to the formation of amide bonds, R–C(=O) –N(–R’)–R”, as suggested by FT-IR spectral changes observed after heat treatment.

Table 1.

Degree of saponification, degree of polymerization, and molecular weight of poly(vinyl alcohol) (PVA) samples used in this study.

Table 1.

Degree of saponification, degree of polymerization, and molecular weight of poly(vinyl alcohol) (PVA) samples used in this study.

| |

Degree of Saponification

(%) |

Degree of

Polymerization |

Molecular

Weight |

| PVA-117 |

99 |

1700 |

76,000 |

| PVA-217 |

88 |

1700 |

83,000 |

Table 2.

SEM images of electro-spun fibers prepared under different electrospinning conditions by varying the applied voltage and the distance between the syringe and the collector. Diameter of the spun fibers, the CO2 adsorption amount obtained through the adsorption test, and the SEM images with ×1,000, ×5,000, and x10,000 magnifications for electro-spun AE/PVA fiber are also shown.

Table 2.

SEM images of electro-spun fibers prepared under different electrospinning conditions by varying the applied voltage and the distance between the syringe and the collector. Diameter of the spun fibers, the CO2 adsorption amount obtained through the adsorption test, and the SEM images with ×1,000, ×5,000, and x10,000 magnifications for electro-spun AE/PVA fiber are also shown.

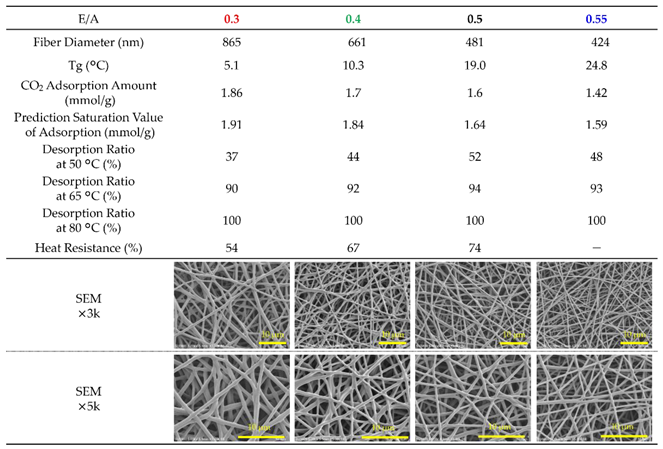

Table 4.

Fiber properties of epoxy-based materials prepared with varying epoxy-to-amine ratios (E/A). The table summarizes fiber diameter, glass transition temperature (Tg), CO₂ adsorption amount after 990 min at 20°C, predicted saturation values of adsorption based on the Avrami model, and desorption ratios after 90 min each at 50, 65, and 80 °C. (For E/A=0.3, 110 min at 50 °C). Heat resistance (Retention ratio of adsorption amount after treatment at 85 °C for 200 hours) is also included. SEM images at magnifications of ×3,000 and ×5,000 show the fiber morphologies under each condition.

Table 4.

Fiber properties of epoxy-based materials prepared with varying epoxy-to-amine ratios (E/A). The table summarizes fiber diameter, glass transition temperature (Tg), CO₂ adsorption amount after 990 min at 20°C, predicted saturation values of adsorption based on the Avrami model, and desorption ratios after 90 min each at 50, 65, and 80 °C. (For E/A=0.3, 110 min at 50 °C). Heat resistance (Retention ratio of adsorption amount after treatment at 85 °C for 200 hours) is also included. SEM images at magnifications of ×3,000 and ×5,000 show the fiber morphologies under each condition.

Table 5.

Compositional parameters of AE/PVA-117 and AE/PVA-217 systems. The table summarizes the amounts of ODE, T-C, TETA, and PVA solution, the ratio of ODE to T-C, the epoxy-to-amine ratio (E/A), the type of PVA used, the ratio of AE to PVA aqueous solution, and the weight percentage of AE in the resultant AE+PVA mixture.

Table 5.

Compositional parameters of AE/PVA-117 and AE/PVA-217 systems. The table summarizes the amounts of ODE, T-C, TETA, and PVA solution, the ratio of ODE to T-C, the epoxy-to-amine ratio (E/A), the type of PVA used, the ratio of AE to PVA aqueous solution, and the weight percentage of AE in the resultant AE+PVA mixture.

| |

AE/PVA-117 |

AE/PVA-217 |

| ODE (g) |

0.8 |

0.8 |

| T-C (g) |

0.2 |

0.2 |

| TETA (g) |

1.6 |

1.6 |

| 8wt% PVA Aq. Solution (g) |

23.4 |

23.4 |

| ODE:T-C |

8:2 |

8:2 |

| E/A |

0.5 |

0.5 |

| PVA |

PVA-117 |

PVA-217 |

| AE:PVA 8wt% Aq. Solution |

1:9 |

1:9 |

| AE/(AE+PVA) |

58% |

58% |

Table 6.

Comparison of fiber properties between AE/PVA-117 and AE/PVA-217 systems. The table summarizes fiber diameter, CO₂ adsorption amount, predicted saturation value, and heat resistance (Retention ratio of adsorption amount after treatment at 85 °C for 200 hours). SEM images at magnifications of ×3,000 and ×10,000 are shown for each sample.

Table 6.

Comparison of fiber properties between AE/PVA-117 and AE/PVA-217 systems. The table summarizes fiber diameter, CO₂ adsorption amount, predicted saturation value, and heat resistance (Retention ratio of adsorption amount after treatment at 85 °C for 200 hours). SEM images at magnifications of ×3,000 and ×10,000 are shown for each sample.