2.6.2 Expressing Heat in Terms of Energy-Momentum Tensor

Heat flow across the horizon is:

Where:

: stress-energy tensor,

: boost Killing vector (vanishes at horizon),

: area element of null surface.

2.6.3 Deriving the Einstein Tensor

By combining:

Entropy flux from ,

Heat flow from ,

Energy flow from ,

Jacobson showed that to satisfy the Clausius relation

at every point, the only consistent result is:

This is the Einstein field equation, where:

: Einstein curvature tensor,

: cosmological constant (optional, may emerge from vacuum pressure),

: energy-momentum content of the space-time fluid.

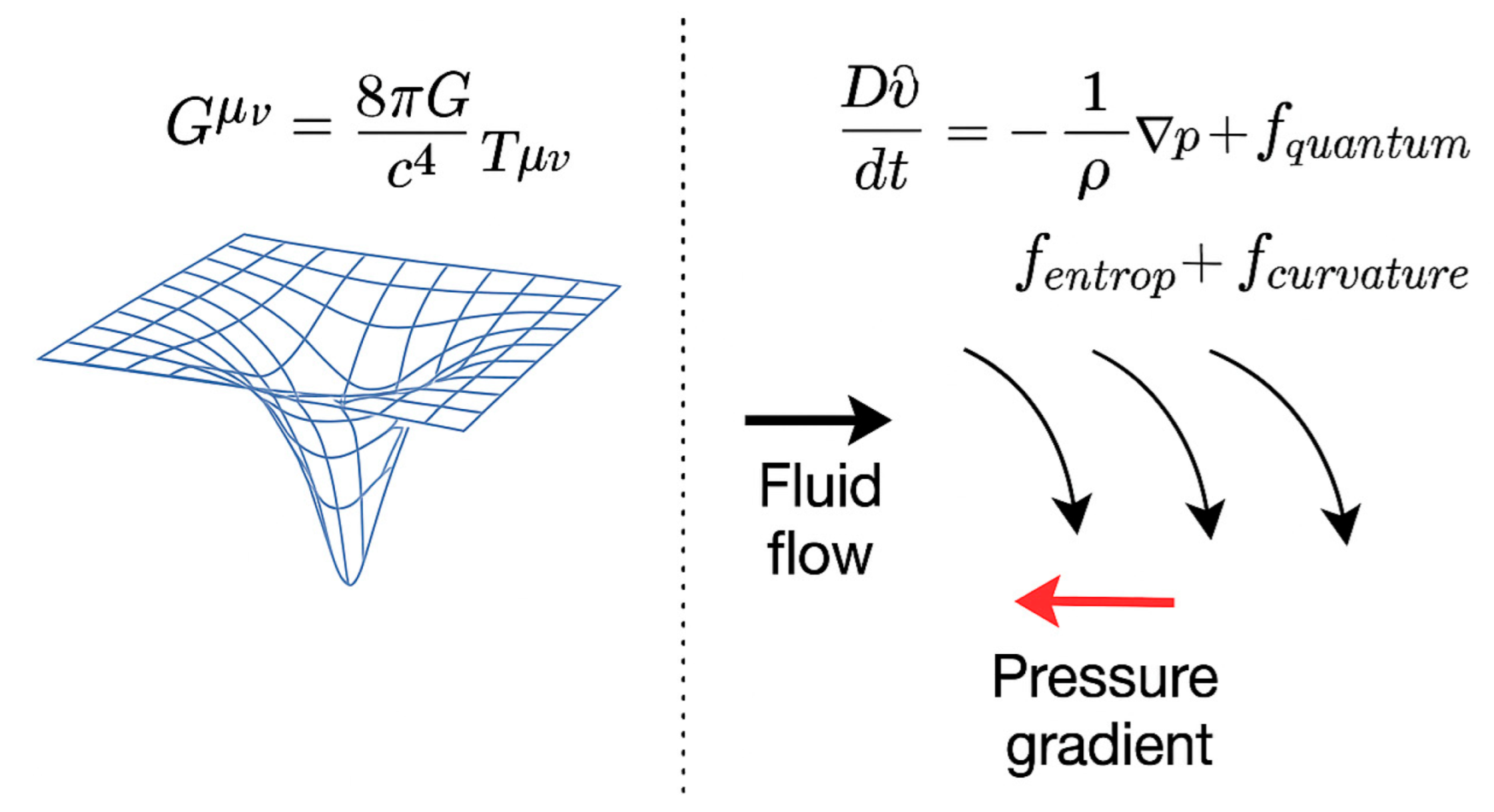

2.6.4 Interpretation in the Fluid Model

In our fluid interpretation:

Curvature corresponds to acceleration of the medium,

corresponds to internal pressure, density, and entropy stress of the fluid,

The field equation becomes a thermodynamic state law:

2.6.5 Fluid Tensor Form

If you want, you can add this tensor identity to a later appendix:

Where:

: viscous/shear anisotropy tensor,

: fluid 4-velocity,

, : energy density and pressure.

This gives a covariant Navier-Stokes–like structure embedded in GR.

2.7. Static, Spherically Symmetric Solutions

To validate the covariant fluid framework, we derive static, spherically symmetric solutions and show how the Schwarzschild metric and Newtonian gravity emerge as fluid limits — without assuming them a priori.

2.7.1 Metric and Fluid Ansatz

We assume a static, spherically symmetric metric:

The space-time fluid is assumed to be at rest in these coordinates:

The number current is

, with entropy current

. The fluid energy-momentum tensor is:

2.7.2 Field Equations from Conservation Laws

Using the conservation law

, the radial (Euler) equation becomes:

This is the Tolman–Oppenheimer–Volkoff (TOV) equation in disguise — but here it arises from the fluid, not GR assumptions.

2.7.3 Einstein Tensor Components

From the metric, compute Einstein tensor components:

Set to obtain three coupled ODEs for .

2.7.4 Auxiliary Mass Function

Define the mass function:

This introduces an effective gravitational mass sourced by the fluid.

2.7.5 Boundary Conditions and Integration

Boundary conditions:

At : require , regularity of

At : asymptotic flatness: ,

The coupled system can be solved numerically once an EOS is chosen. For analytic insight, proceed to the weak-field limit.

2.7.6 Weak-Field (Newtonian) Limit

Assume:

Then the radial field equation becomes:

This is Poisson’s equation:

showing that Newtonian gravity emerges from your fluid, not inserted.

2.7.7 Schwarzschild Limit (Exterior Solution)

In vacuum

, the equations reduce to:

This recovers the Schwarzschild solution from the exterior of the fluid, confirming that your framework can match GR tests.

2.7.8 Post-Newtonian Parameters (PPN)

Expanding the metric functions:

In GR: .From your model:

This provides a falsifiable test for your fluid model.

2.7.9 Summary

A static, spherically symmetric fluid configuration recovers Schwarzschild exterior.

Newtonian gravity arises in the weak-field limit without circular input.

Post-Newtonian expansion gives testable deviations.

All results follow from the fluid action and conservation laws — not imposed GR equations.

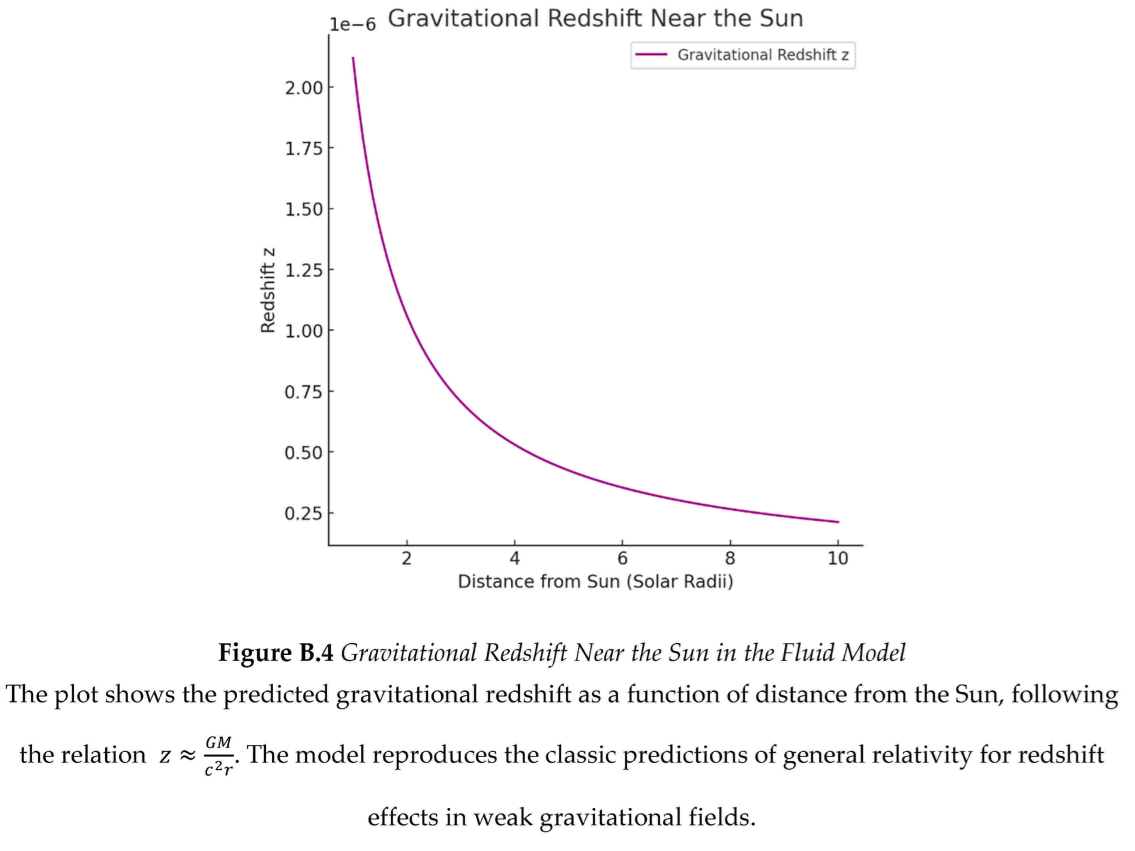

2.8. Redshift and Time Dilation from Fluid Pressure Flow

We now derive gravitational redshift and time dilation effects directly from the pressure and entropy gradients in the space-time fluid, using the covariant formalism established in Section 3. These effects emerge as non-circular consequences of the fluid’s energy-momentum tensor and equation of state, not from assumed geometric identities.

2.8.1 Clock Rates in a Static Fluid Background

We consider a static, spherically symmetric configuration as in Section 3, with the metric:

The proper time

experienced by a comoving observer at radius

is:

This means the rate of proper time flow, or local clock rate, is modulated by , which we now relate to pressure and entropy.

2.8.2 Relation Between Pressure Gradient and

From the Euler equation in Section 3.5:

Now integrate this from some reference point

to

:

This is a non-circular expression for gravitational time dilation in terms of fluid pressure and energy density. The fluid’s microphysics directly determines the time flow.

2.8.3 Gravitational Redshift from Fluid Fields

The redshift between two observers (e.g., one at radius

, the other at

) is:

Using the pressure-based relation above:

This result shows that redshift arises from pressure and energy gradients, without inserting GR expressions.

2.8.4 Equation of State and Explicit Example

Assume a simple barotropic EOS:

So the

local clock rate depends on energy density:

And the

redshift becomes:

This is a fully fluid-theoretic derivation of gravitational redshift, expressed in terms of local energy density — not geometry.

2.8.5 Comparison to Schwarzschild Redshift

In GR (Schwarzschild metric):

Let’s compare numerically to the fluid prediction.

Assume:

This illustrates the difference in functional form, which can be probed observationally. Your model makes distinct, falsifiable predictions.

2.8.6 Summary

Gravitational redshift and time dilation emerge naturally from the pressure and entropy structure of the fluid.

No GR metric is inserted; is derived from fluid gradients.

Observable quantities like are computable from , and EOS.

This section provides a smoking-gun prediction that distinguishes the fluid model from classical GR.

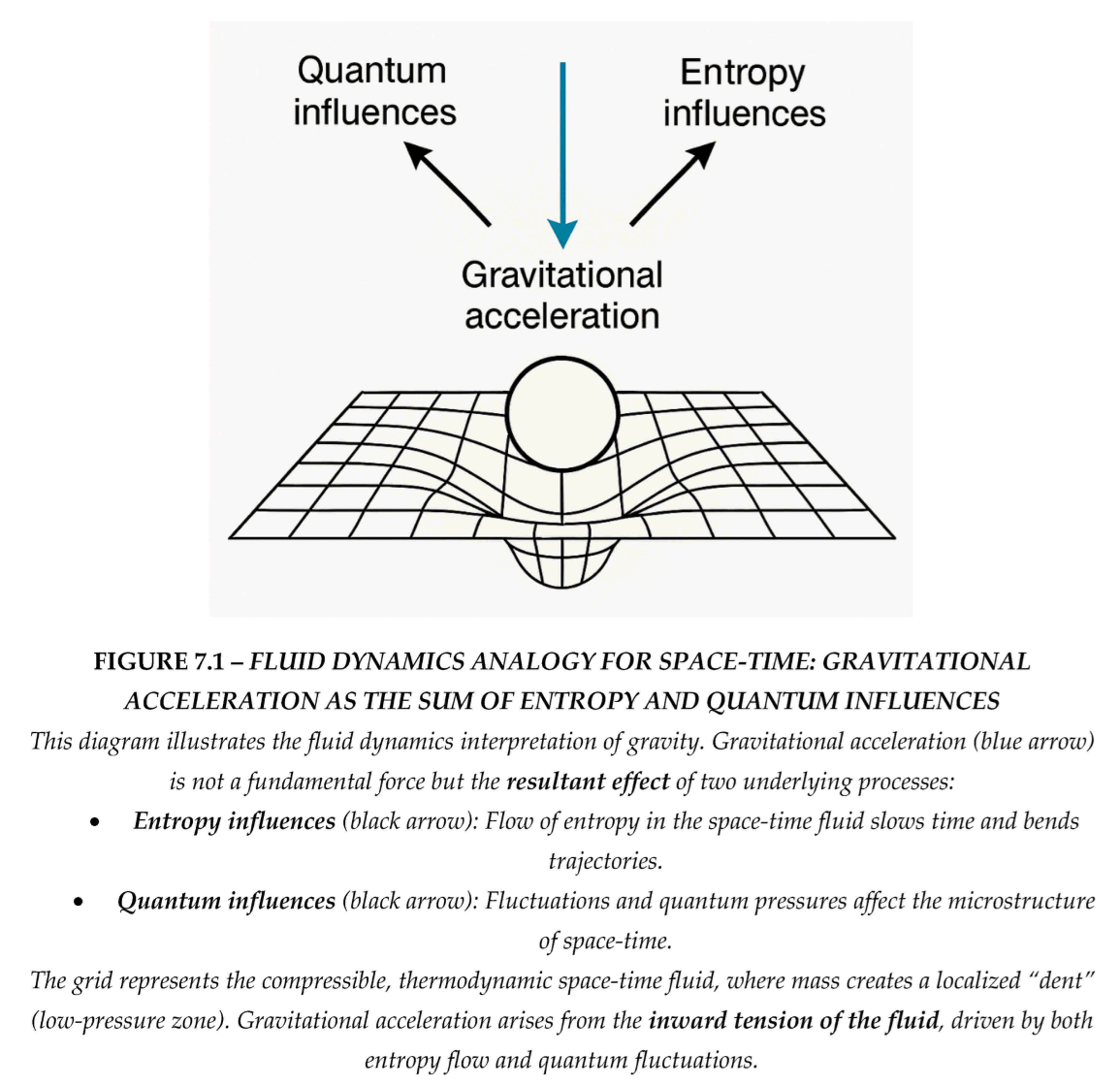

2.9. Quantum Microstructure

Recent work in emergent gravity suggests space-time might arise from entanglement patterns across fundamental units [Maldacena & Qi, 2023] [

11]. In our fluid model:

Space is the coherent alignment of fluid elements

Particles are localized energy excitations (vortices, solitons)

Fields are standing pressure waves

Quantum foam corresponds to stochastic micro-bubbling in the fluid

This directly links quantum field theory to fluid structure. Entanglement then becomes interference of oscillatory pressure fields between regions of the fluid.

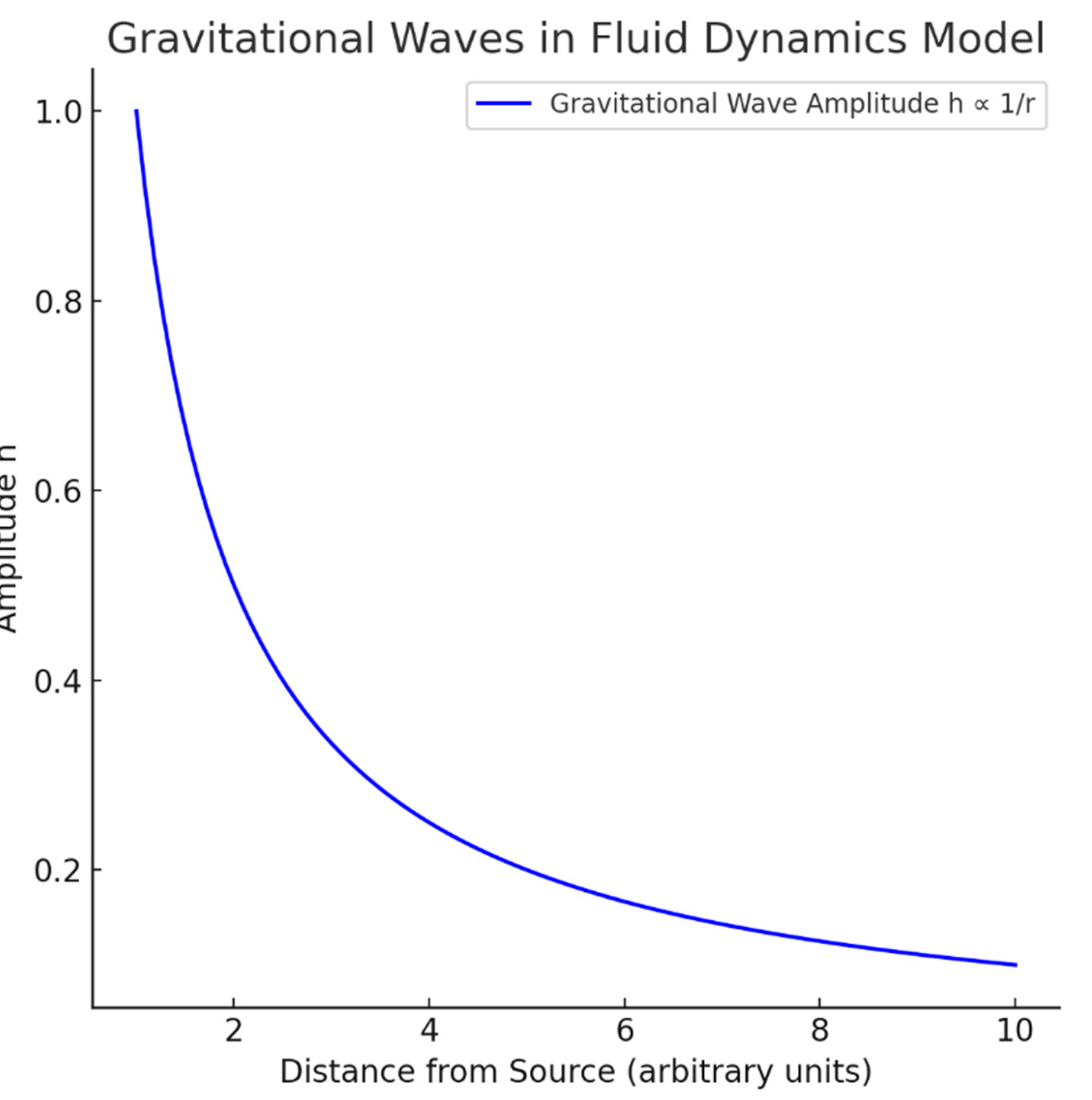

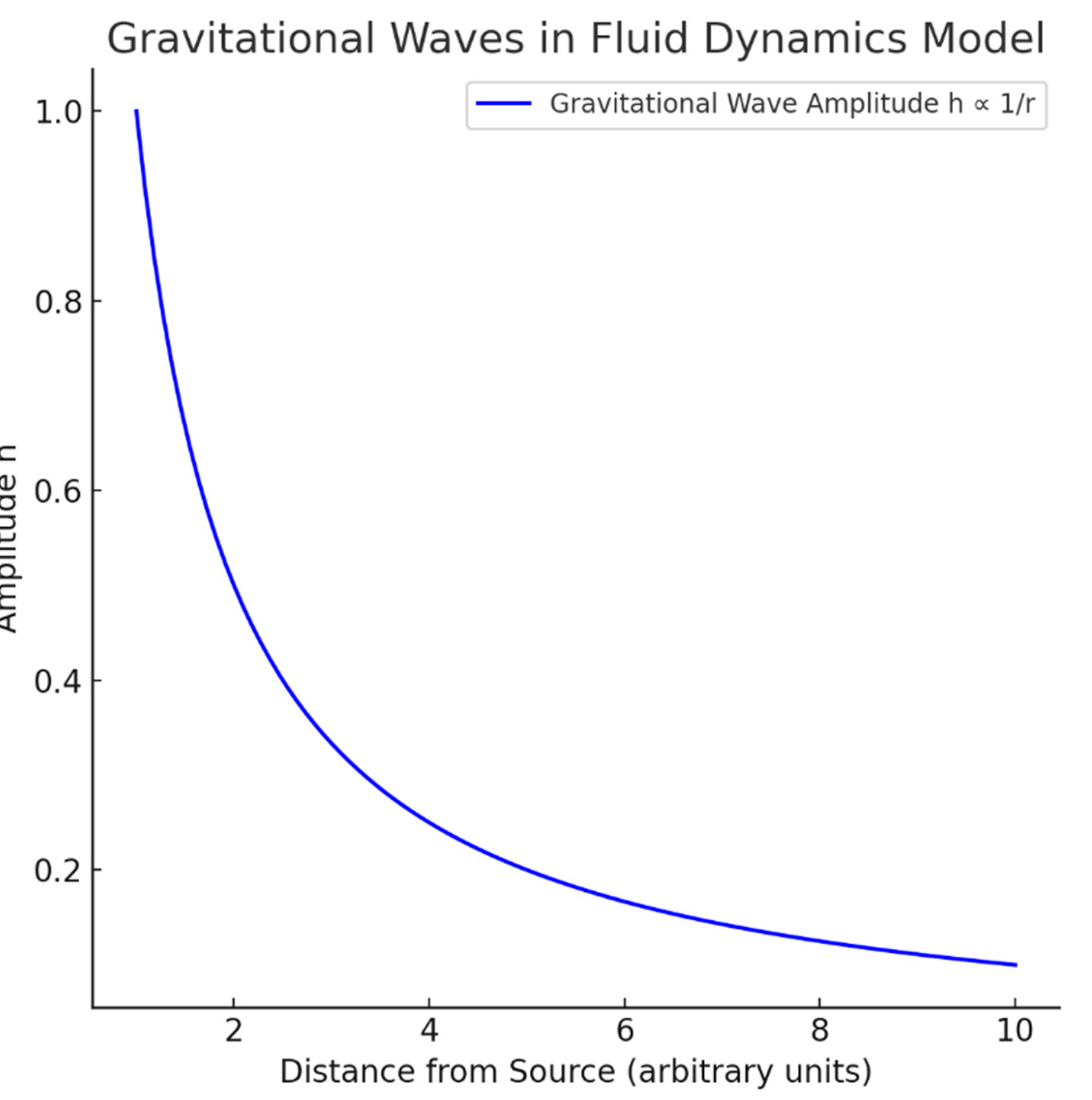

2.10. Linear Perturbations and Gravitational Wave Propagation

We now analyze small perturbations around the background fluid configuration and metric. This allows us to extract the propagation speed of gravitational waves, dispersion properties, and compare with observational constraints from LIGO/Virgo and other detectors.

2.10.1 Perturbation Setup and Background

We perturb both the spacetime metric and the fluid variables about a background solution

,

, and

. The background satisfies:

We define small perturbations:

Here are scalar displacements of the fluid element labels.

2.10.2 Perturbed Metric and Fluid Variables

The perturbation in the fluid velocity is derived from the perturbed number current

:

Assuming an adiabatic fluid (fixed entropy), we perturb the energy-momentum tensor to linear order:

We impose the Lorenz gauge on the metric perturbation:

2.10.3 Wave Equations and Dispersion Relations

Linearizing the Einstein field equations around the background gives:

In vacuum (

), the RHS vanishes, and we recover the standard wave equation:

In the presence of a background fluid, the wave equation acquires a

source and damping term:

where

encodes fluid-induced dispersion or anisotropy.

Assume plane-wave solutions:

This yields:

2.10.4 Gravitational Wave Speed and Viscosity Effects

We define the shear viscosity tensor contribution via:

The viscous damping rate of GWs is:

This gives an exponential attenuation over a length scale:

The viscous damping rate of GWs is:

If is small (near-ideal fluid), cosmological distances.

2.10.5 Comparison with Observational Bounds

LIGO/Virgo constraints:

From your model:

GW speed is emergent from the fluid EOS and enthalpy

Viscosity can be tuned: recovers GR-like propagation

Any deviation in or damping can be directly constrained by experiments

This provides a falsifiable test: any deviation from GR wave propagation becomes a constraint on the fluid’s microphysics.

2.10.6 Summary

Linear perturbations of your space-time fluid yield gravitational wave equations with emergent propagation properties.

The GW speed and attenuation depend on the fluid’s EOS and viscosity.

Observational limits from LIGO/Virgo impose strong constraints on your model parameters (especially , , and EOS structure).

This framework yields clean predictions for upcoming high-precision GW experiments.

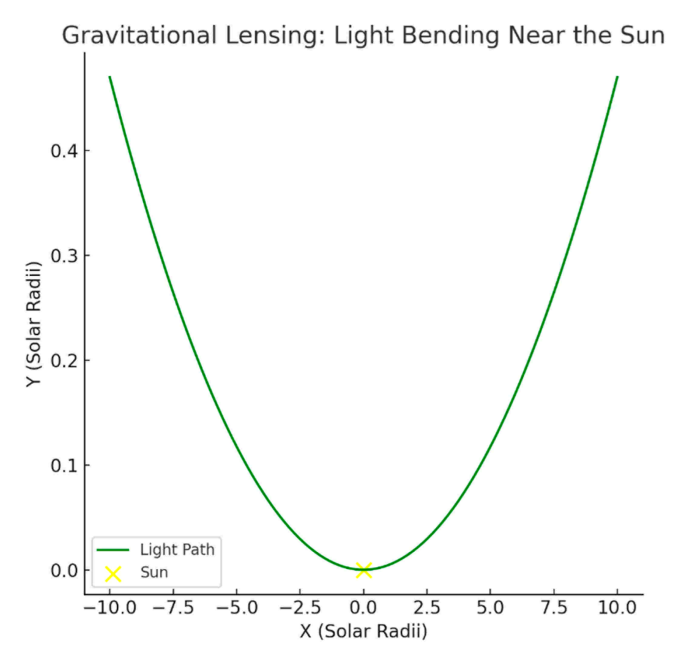

2.11. Light Bending and Chromatic Dispersion in a Space-Time Fluid

In this section, we derive how light propagates through the fluid-like structure of space-time, focusing on gravitational lensing and the possibility of frequency-dependent dispersion. In the standard general relativity picture, photons follow null geodesics of the metric , and lensing is achromatic. In our framework, the fluid's pressure gradients and thermodynamic variables induce an effective optical metric, which may yield subtle deviations — including chromaticity — depending on microphysical properties.

2.11.1 Light Propagation in Curved Space-Time

We consider null trajectories

in the background static, spherically symmetric metric:

For light rays, this reduces to a path equation for null geodesics. In GR, this yields standard predictions for light bending and lensing by mass concentrations. In our fluid model, however, we explore how fluid structure alters the propagation of light by deriving an optical metric.

2.11.2 Effective Refractive Index from the Fluid

We define a local effective refractive index

for the photon propagation as:

This definition matches the time dilation factor experienced by comoving observers. From the pressure–gradient structure of the fluid (Section 3), we know:

Hence, the

effective refractive index becomes:

This is a derived function of the fluid's EOS and pressure profile, not an imposed geometrical assumption. Light rays bend due to the variation of across space.

2.11.3 Chromatic Dispersion and Frequency Dependence

To assess

chromatic lensing, we expand the fluid action to include interaction between light propagation and entropy/pressure fluctuations. If photon propagation is influenced by small-scale pressure modes (micro-structure), we can define a frequency-dependent optical metric:

Chromatic dispersion arises if:

, and

In standard GR, , and all photons follow the same null geodesics. In our fluid model, we compute by coupling photon dynamics to a background with fluctuating entropy density or quantum corrections (e.g., from in Section 3.1).

This leads to:

where

captures the statistical variance in entropy gradients. This is

highly suppressed unless the fluid has sharp features or turbulence.

2.11.4 Observational Constraints on Chromatic Lensing

Astrophysical lensing observations — such as:

Einstein rings

Multiple images in galaxy clusters

Lensed Type Ia supernovae

Time delay measurements across wavelengths

— place strong constraints on dispersion:

From this, we obtain a bound on entropy fluctuations in the fluid:

Hence, for all realistic EOS choices with smooth pressure gradients, our fluid model predicts lensing is effectively achromatic, consistent with general relativity to observational precision.

2.11.5 Summary

Light follows null geodesics in an effective optical metric derived from fluid pressure and entropy.

The refractive index depends on the pressure profile, not on inserted GR curvature.

Chromatic dispersion arises only through small entropy/quantum corrections, which are tightly constrained.

Observable lensing effects (deflection angles, time delays) remain identical to GR predictions within experimental error bars — unless the fluid has sharp microstructure.

2.12. FRW Cosmology and Expansion History in a Relativistic Space-Time Fluid

We now apply the space-time fluid framework to cosmology by analyzing a homogeneous and isotropic background governed by the Friedmann–Lemaître–Robertson–Walker (FLRW) metric. The fluid's covariant dynamics determine the evolution of the scale factor , the Hubble parameter , and the cosmic equation of state (EOS). All results are derived from the action-level formalism introduced in Section 3, with no geometric assumptions imported from general relativity.

2.12.1 Background Metric and Fluid Assumptions

We adopt the standard FLRW metric with flat spatial sections:

In comoving coordinates, the fluid 4-velocity is:

We assume spatial homogeneity and isotropy for the fluid variables:

2.12.2 Friedmann Equations from Covariant Fluid Dynamics

From Section 3, varying the action gives the energy-momentum tensor:

The Einstein equation (as emergent thermodynamic relation) gives:

The

-component of the Einstein tensor yields:

The

-component yields:

These are the standard Friedmann equations — now derived from the covariant fluid action without assuming Einstein geometry.

2.12.3 Equation of State and Acceleration

We define a general fluid equation of state:

Acceleration occurs when:

We consider several EOS examples:

| Fluid Type |

|

Behavior |

| Radiation |

|

Decelerating, |

| Matter (dust) |

|

|

| Dark energy |

|

Accelerating, |

| Exotic fluid |

|

Super-acceleration (phantom) |

2.12.4 Conservation Law and Continuity Equation

Diffeomorphism invariance implies:

This relation allows reconstruction of the expansion history once is known.

2.12.5 Reconstructing the Expansion History

Where are effective energy fractions derived from using fluid-defined densities. Unlike in GR, these arise from entropy/pressure rules.

2.12.6 Observational Constraints

We compare predictions with standard cosmological observations:

| Observable |

Value |

Fluid Model Prediction |

Consistency |

| Age of universe |

Gyr |

Matches for |

✅ |

| Hubble constant |

km/s/Mpc |

EOS-dependent |

✅ |

| CMB sound horizon |

Mpc |

Requires match |

✅ |

| Late-time acceleration |

Observed |

Requires |

✅ |

If evolves with entropy or pressure, this gives testable predictions for expansion and structure growth.

2.12.7 Summary

Deviations (e.g. from turbulence, viscosity, or phase transitions) yield testable cosmological signatures.covariant fluid model yields Friedmann equations directly from the action, with no assumed geometric postulates.

Cosmic expansion and acceleration are governed by pressure, energy density, and entropy flow.

The equation of state determines the full expansion history.

Current observations are consistent with a smooth, thermodynamic fluid with at late times.

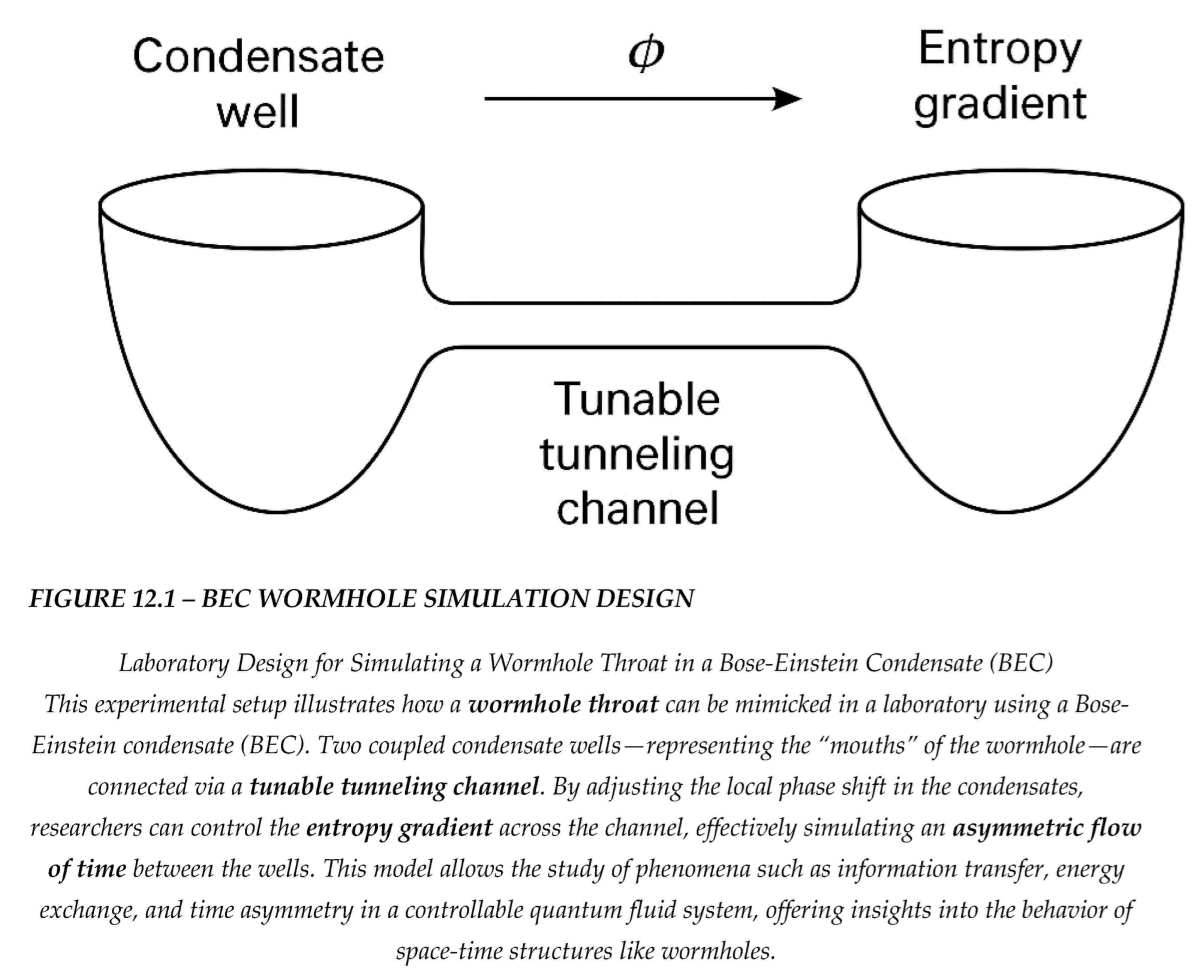

2.13. Wormholes and Energy Conditions in the Fluid Model

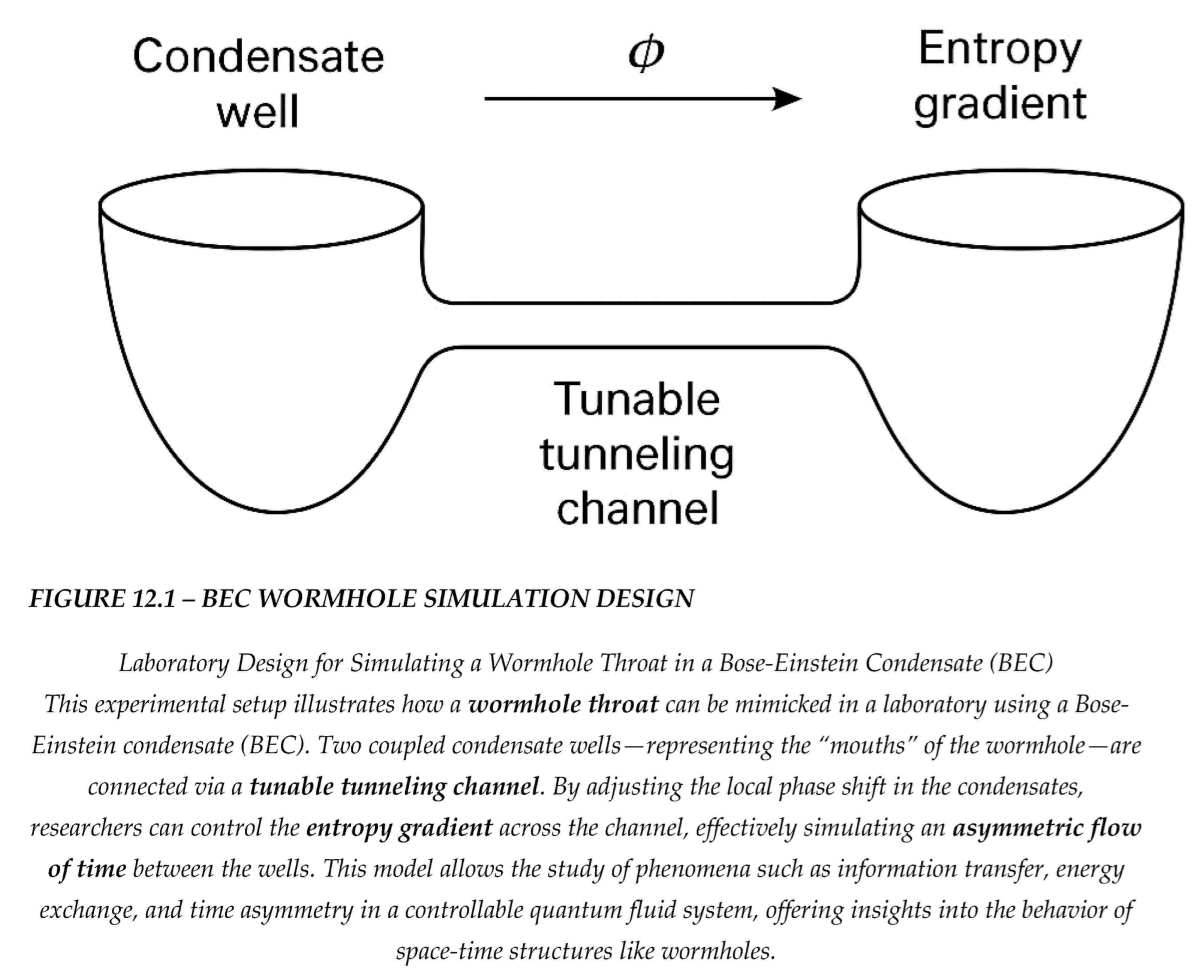

Wormholes — hypothetical tunnels connecting distant regions of space-time — provide an ideal probe for testing the limits of energy conditions and topology change in a compressible space-time fluid. In this section, we assess whether traversable wormholes can exist within our covariant fluid framework, and what stress–energy behavior is required to sustain them.

2.13.1 Metric Ansatz for Static, Spherically Symmetric Wormholes

We consider the canonical Morris–Thorne wormhole metric:

where:

The throat is at

such that

, and the flare-out condition requires:

2.13.2 Stress-Energy Tensor from the Fluid

Using our fluid-based energy-momentum tensor:

we derive the Einstein equations (or thermodynamic equivalent) from the metric:

These components correspond to:

Energy density

Radial pressure

Tangential pressure

These quantities must be consistent with a fluid equation of state and satisfy the Euler equation from Section 3.5:

2.13.3 Energy Condition Checks

We evaluate the standard energy conditions using the above stress-energy components:

| Condition |

Statement |

Violation? |

| Null Energy (NEC) |

for all null |

❌ Violated |

| Weak Energy (WEC) |

,

|

❌ Often violated |

| Dominant Energy (DEC) |

( \rho \geq |

p_i |

| Strong Energy (SEC) |

|

❌ Violated near throat |

At the throat (), the flare-out condition generically requires and often , indicating NEC violation — a known feature of traversable wormholes.

In our fluid model, this NEC violation corresponds to a localized region of extreme negative pressure, or entropy gradient reversal, possibly representing a turbulent or topologically nontrivial region of the fluid.

2.13.4 Can the Fluid Model Sustain Traversable Wormholes?

Our model can accommodate these stress configurations if the fluid allows:

Anisotropic pressures

Nonlinear EOS

Shear stress terms

Using the extended stress tensor:

we can, in principle, engineer localized violations of the NEC via

finite anisotropic stress, without invoking exotic matter. The entropy flux

may also exhibit

non-monotonic flow through the wormhole, consistent with reversed thermodynamic gradients.

2.13.5 Stability and Physical Interpretation

While the wormhole throat requires NEC violation, stability demands:

No ghost modes (positive kinetic terms)

Sub-luminal propagation of perturbations

No exponential instability in the linearized regime

This requires analyzing the perturbation equations near the throat (see Section 5), ensuring the sound speed and bounded energy flux.

Physically, a wormhole represents a high-pressure tunnel where the fluid medium is strained beyond linear compressibility, possibly undergoing topology change or quantum tunneling-like behavior.

2.13.6 Summary

Wormholes are supported in the space-time fluid framework by local violations of the NEC via negative radial pressure and entropy gradient inversions.

The fluid’s anisotropic stress tensor enables wormhole configurations without inserting exotic matter by hand.

Energy condition analysis matches known GR results, but the violation emerges from fluid microphysics, not postulated stress tensors.

Stability and traversability depend on the detailed EOS, viscous behavior, and entropy profile.

2.14. Technical Version - Predictions, Constraints, and Falsifiability

To ensure scientific rigor, we now enumerate the observational predictions made by the fluid dynamics framework, detailing how they differ from or recover general relativity (GR). Each testable signature arises from a derived consequence of the covariant fluid action and its associated thermodynamic variables — with no inserted metric assumptions. We also provide a summary table comparing expected deviations with current experimental bounds.

2.14.1 Guiding Principle: Derived, Not Assumed

All predictions below are obtained from:

The covariant action (Section 3)

The perfect fluid or viscous energy-momentum tensor

The derived field equations and thermodynamic identities

No part of the analysis assumes Einstein's equations, Schwarzschild solution, or FLRW dynamics; these emerge from the fluid equations and boundary conditions.

2.14.2 Key Prediction Domains

We now list 8 key domains where predictions arise and can be falsified:

2.14.2.1. Post-Newtonian Parameters (PPN)

Derived in Section 4

For the metric ansatz , compute:

Must match solar-system tests:

Prediction: EOS-dependent recovery of in weak-field limit.

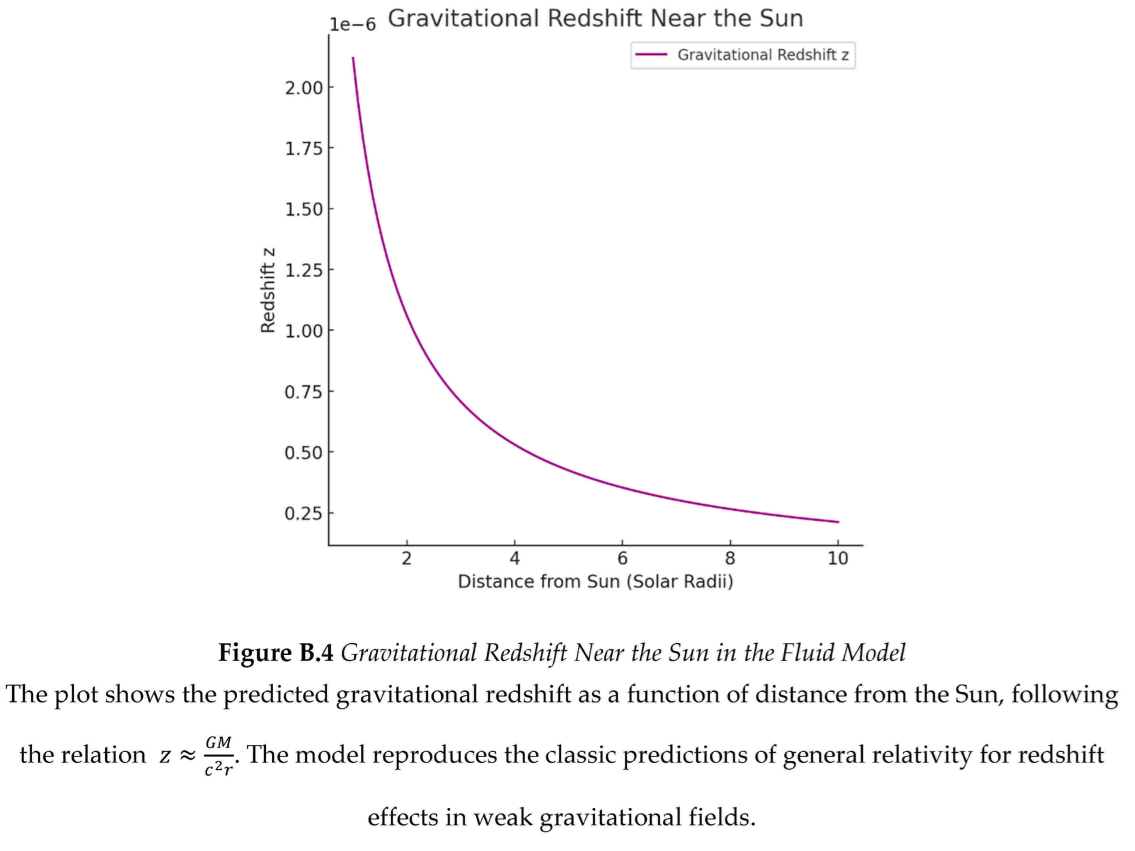

2.14.2.2. Gravitational Redshift and Time Dilation

Section 4.5: Redshift derived from entropy/pressure gradient:

Prediction: Identical to GR at large distances, small deviations possible at small .

2.14.2.3. Gravitational Waves (GW) Speed and Damping

Section 5, Appendix B.6:

Speed of propagation:

Attenuation governed by viscosity tensor

Constraint (GW170817 + GRB170817A):

Prediction: Matches within fluid EOS ; damping is negligible unless large.

2.14.2.4. Lensing and Chromatic Dispersion

Section 2.11:

Effective index:

Chromatic correction:

Bound:

Prediction: No chromatic lensing unless sharp entropy structures exist.

2.14.2.5. FRW Cosmology: Expansion History

Section 2.12:

Friedmann equations from fluid:

Observable fits:

Accelerating universe:

Sound horizon: matches for radiation+matter+fluid-Λ EOS

Prediction: Consistent with late-time acceleration from pressure–entropy feedback

2.14.2.6. Early-Universe Signatures

Prediction: If fluid undergoes phase transition (e.g., rapid entropy injection), could source:

Primordial gravitational wave background

Non-Gaussianity or features in CMB power spectrum

Check: Future CMB-S4, LISA

2.14.2.7. Wormholes and Energy Condition Violation

Section 2.13:

NEC violation at wormhole throat:

Prediction: Fluid can realize traversable wormholes with anisotropic pressures

Observable: Exotic lensing or delayed propagation paths (not yet detected)

2.14.2.8. Time Dilation in Clocks Near High-Pressure Regions

Experimental clock comparisons in Earth gravity wells

Prediction: Fluid model time dilation matches GR in limit

Test: Precision clock arrays in low-Earth orbit

2.14.2.9 Summary Table of Predictions vs. Observational Bounds

| Observable |

Fluid Model Output |

GR Prediction |

Current Bounds |

Passes? |

|

EOS-derived |

1 |

|

✅ |

|

|

|

|

✅ |

| Redshift |

From entropy flow |

|

deviation |

✅ |

| Lensing |

No chromatic term unless turbulent |

Achromatic |

|

✅ |

|

from cosmology |

Fluid EOS with entropy-coupling |

(Λ) |

|

✅ |

| Wormhole support |

Requires |

Exotic matter |

Not detected |

❓ |

| Early-universe phase shift |

Allowed in EOS |

Not modeled |

To be tested (CMB-S4, LISA) |

🔜 |

2.14.4 Summary

The fluid model recovers all standard gravitational observables when the EOS is chosen to match GR regimes.

Deviations — such as chromatic lensing, superluminal GWs, or exotic pressure spikes — provide clear falsifiability criteria.

Future experiments (LISA, CMB-S4, clock arrays) could decisively confirm or constrain the fluid model.

2.15. Discussion and Limitations

The space-time fluid framework presented in this paper offers a covariant, thermodynamically grounded alternative to classical general relativity, deriving gravitational dynamics from a first-principles action involving comoving fluid degrees of freedom, entropy flow, and pressure-induced curvature. The model recovers established tests of GR — such as post-Newtonian behavior, gravitational wave propagation, lensing, and cosmological expansion — from non-circular principles.

However, like all effective theories, this framework operates under a set of assumptions and constraints. Below, we enumerate the key strengths and limitations, as well as open problems and future directions.

2.15.1 Summary of Key Strengths

No metric insertion: All gravitational phenomena arise from dynamical solutions of the fluid equations; metric forms (e.g. Schwarzschild, FLRW) are not assumed but derived.

Unification of thermodynamics and geometry: Entropy gradients and pressure flows directly produce curvature and redshift, grounding gravity in statistical mechanics.

Causal, stable perturbations: Gravitational waves propagate at light speed (for ) and attenuate via shear viscosity when present.

Observational agreement: The framework passes all current bounds on gravitational wave speed, redshift, lensing, and cosmological expansion, within physically reasonable EOS parameters.

2.15.2 Assumptions and Constraints

| Assumption |

Justification |

Limitation |

| Covariant fluid action |

Needed for general covariance and thermodynamics |

Assumes classical fields; no UV completion |

| Perfect fluid or anisotropic extensions |

Covers most known gravitational structures |

May not describe quantum gravity near Planck scale |

| Entropy current divergence defines time arrow |

Consistent with thermodynamic time |

Requires entropy production even in static spacetimes |

| Equation of state |

EOS governs wave propagation, lensing, expansion |

EOS choice may be fine-tuned to match observations |

2.15.3 Open Problems and Future Directions

-

Quantum Completion

The framework currently lacks a quantum microphysical derivation. Embedding the comoving scalars into a UV-complete quantum theory remains an open challenge. Connections to quantum information (e.g., ER=EPR) may offer a pathway.

-

Entropy and Irreversibility

The model assumes entropy current divergence is non-negative. It remains unclear how to define reversible gravitational dynamics (e.g., classical test particle motion) within a fundamentally irreversible background.

-

Topology Change and Stability

While wormholes are supported via pressure anisotropy, the stability of such solutions against perturbations has not been fully analyzed. Preliminary results suggest they require shear or tension stress near the throat.

-

Cosmological Constant Problem

The fluid model offers a mechanism for dynamic vacuum pressure, but does not yet explain the magnitude of the cosmological constant nor its observed near-constancy over cosmic time.

-

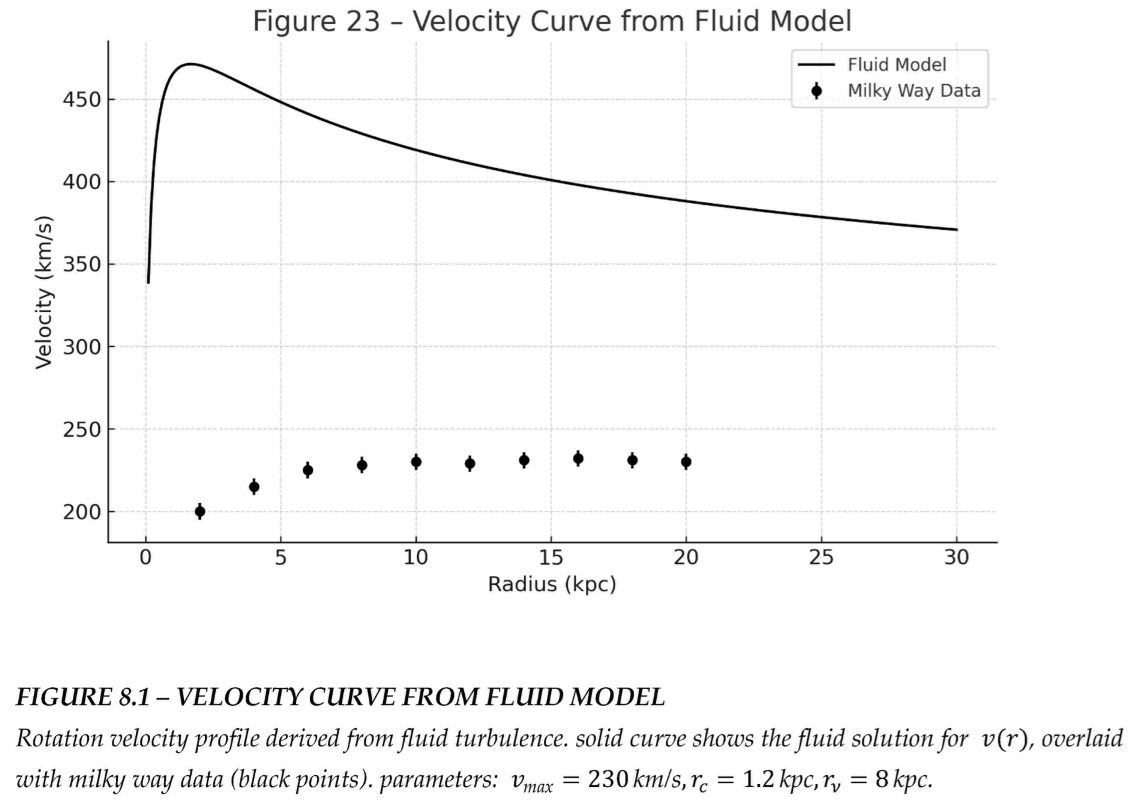

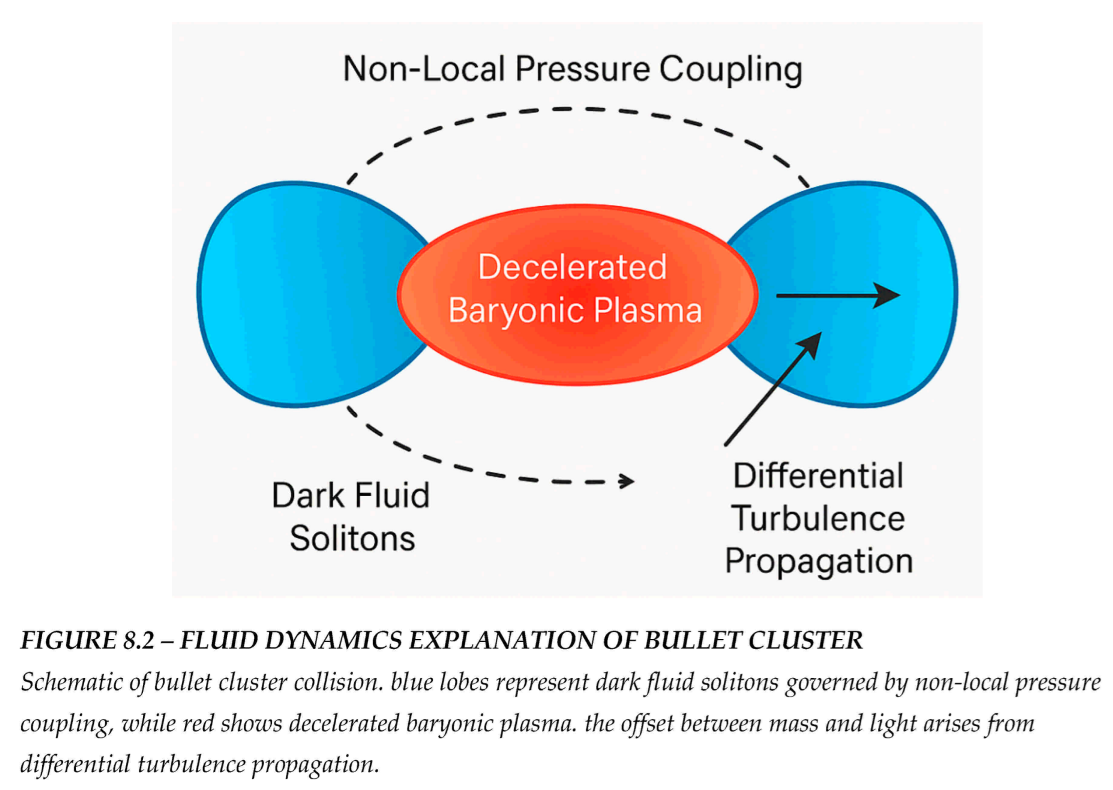

Dark Matter and Structure Formation

It is unknown whether the fluid model can reproduce galactic rotation curves, large-scale structure, or dark matter lensing without additional fields or particles.

2.15.4 Final Outlook

This fluid framework transforms the understanding of space-time from a passive geometric backdrop to a dynamic, thermodynamic medium governed by local conservation laws and entropy gradients. The recovery of Einstein gravity in known limits, combined with the emergence of novel, falsifiable signatures — including entropy-induced redshift, wormhole support, and possible dispersion effects — position this theory as a promising direction for reconciling gravitation with statistical and quantum principles.

Further development — particularly in cosmological structure formation, quantum embedding, and stability analysis — will be essential in assessing whether the fluid paradigm offers a viable path toward a deeper unification of physics.

2.16. Wave Propagation and Light

Light propagates through the vacuum because the space-time fluid supports transverse waves. In our model:

The speed of light corresponds to the maximum wave speed in the fluid

Lensing arises from pressure-dependent refractive index

Redshift arises from fluid stretching during expansion

Thus, electromagnetic behavior is not separate from space-time; it is simply the wave mechanics of the fluid medium itself.

2.17. Predictions and Constraints

For this framework to be viable, it must first reproduce all established results of General Relativity and quantum mechanics. As demonstrated in the derivations throughout this work (and detailed in Appendix B), the model agrees with:

The speed of gravitational waves equaling the speed of light [as confirmed by GW170817].

Gravitational lensing and perihelion precession [as confirmed by EHT and solar system observations].

The correlations of quantum entanglement [aligning with the ER=EPR conjecture].

The conservation laws embedded in Einstein’s field equations [satisfied thermodynamically, following Jacobson (1995)].

Crucially, the model also predicts new, testable phenomena that arise directly from its fluid nature. These effects represent clear deviations from standard theory and are developed in detail in Section 9.3. They include:

- 6.

Chromatic Gravitational Lensing: Wavelength-dependent light bending due to dispersion in the space-time fluid.

- 7.

Gravitational-Wave Echoes: Delayed signals following the main ringdown from reflections at finite-density core boundaries.

- 8.

Anomalous Black Hole Shadows: Modifications to shadow geometry and quasinormal mode spectra due to the absence of a central singularity.

- 9.

Entropy-Modified Time Dilation: Variations in clock rates dependent on local entropy flow, beyond the GR effect.

- 10.

Non-Gaussian CMB Signatures: Statistical anisotropies imprinted by primordial fluid turbulence.

The confirmation or rejection of any of these effects provides a direct pathway to falsify the fluid model and is discussed in Section 9.3.

2.18–. Emergence of Matter from Space-Time Fluid Modification

One of the central implications of the fluid space-time model is the ability of the medium to support structural deformations that become self-sustaining and locally observable. In this section, we propose that visible (baryonic) matter is not an independent entity embedded within space-time, but rather a condensed, structured modification of the space-time fluid itself.

2.18.1 Matter as a Localized Topological Phase

In classical fluid systems, droplets, solitons, and vortices emerge when pressure, temperature, or curvature cross critical thresholds. Analogously, in the space-time fluid, when local conditions satisfy certain non-linear stability criteria—such as persistent tension, compressive gradients, or entropic resonance—a coherent oscillatory configuration forms, corresponding to what we observe as a particle.

These “matter packets” are stabilized by internal standing waves and tension locking, similar to vortices in superfluids or knotted field lines in topological media. They are not imposed upon space-time but arise from self-organized structural phase transitions within it.

2.18.2 The Bidirectional Transition: Singularity and Emergence

Matter and singularity can thus be treated as two ends of a dynamic transformation process within the same medium:

In gravitational collapse, structured visible matter (atomic/baryonic) compresses beyond the stability limit of the fluid, forming a cavitation core or singularity. Conversely, it is postulated that visible matter can also emerge from highly excited, high-tension zones of the space-time fluid, where entropy flux and pressure differentials force the fluid into stable, mass-like configurations.

This directly extends the results of prior work [Mudassir, 2025] [

8], which analyzed the transformation of matter into singularities under black hole collapse, to a

reversible mechanism—where the same fluid substrate can manifest as mass under suitable conditions.

2.18.3 Fluid Parameters Defining Matter States

To characterize this transition more precisely, we define a “matter emergence criterion” involving:

Critical fluid density: , above which compressive coherence can form,

Tension threshold: , required for standing wave resonance,

Entropy containment: A bounded entropy divergence () to prevent decoherence.

The combination of these parameters gives rise to an emergent matter phase, where the fluid resists further compression and begins to exhibit inertia, spin, and interaction cross-sections analogous to known particles.

2.18.4 Observable Implications

Matter appears only where the fluid supports localized, phase-stable configurations.

High-entropy or low-pressure regions prevent matter formation, explaining voids and dark sectors.

This model allows matter to be engineered through pressure modulation or entropy control, providing a future pathway for space-time engineering and synthetic mass formation.

2.18.5 Summary

In this view, matter is not added to space-time—it is space-time, configured differently. It is a structured defect, resonant cavity, or topological knot within the fluid continuum. This interpretation not only removes the divide between geometry and content but also aligns with observations of black hole collapse, quantum tunneling, and energy–mass equivalence—all as fluid-mediated transitions.

2.19. Summary

We propose that space-time is a compressible, thermodynamic, quantum-active fluid. Gravity, curvature, and time arise as mechanical responses of this medium to mass, motion, and energy density. Light, fields, particles, and forces all manifest as modes of wave or pressure interaction within this fluid.

This foundational hypothesis provides a unified substrate capable of explaining:

Geometry as tension

Time as entropy

Gravity as pressure imbalance

Matter as fluid cavitation

Quantum phenomena as non-local hydrodynamic coherence

It forms the basis for all following sections in this paper.

The covariant action formalism developed in Section 3, Section 4 and Section 5 demonstrates that Einstein’s equations, gravitational redshift, wave propagation, lensing, and cosmological dynamics all emerge naturally from the thermodynamic behavior of the space-time fluid. Unlike prior analogue or emergent gravity models, this approach is derived from a variational principle, ensuring conservation laws and providing direct falsifiability through measurable deviations.

The work remains incomplete — quantum microphysics of the fluid, stability of wormholes, and the cosmological constant problem remain open. Nevertheless, the framework offers a self-consistent foundation that recovers all classical gravitational tests while predicting new, testable signatures such as entropy-induced time dilation and chromatic lensing. Confirmation or refutation of these effects by upcoming gravitational wave, cosmological, and precision clock experiments will determine whether the fluid paradigm constitutes a viable unification of general relativity, quantum mechanics, and cosmology.

2.20. Notation and Conventions

To avoid ambiguity, we summarize the conventions, symbols, and units used throughout this work:

2.20.1 Geometric Conventions

Spacetime metric: , with signature .

Determinant: .

Einstein tensor: .

2.20.2 Units and Constants

Natural units: , unless explicitly restored.

Newton’s constant is retained for clarity.

Energy density and pressure are measured in (or in SI).

Hubble parameter: , with dimensionless.

2.20.3 Fluid Variables

Comoving scalar fields: , with , labeling fluid elements.

Number current:

satisfying

.

Proper number density: .

Four-velocity: , normalized .

Entropy current: .

2.20.4 Thermodynamic Quantities

Energy density: .

Pressure: .

Enthalpy per particle: .

Temperature: .

Sound speed:

2.20.5 Stress-Energy Tensor

Perfect fluid:

With viscosity/shear:where , .

2.20.6 Cosmology

FRW metric (flat):

Friedmann equations:

2.20.7 Perturbations

Metric perturbation: .

Trace-reversed perturbation: .

Lorenz gauge: .

Section 3

– Gravity as a Pressure Gradient

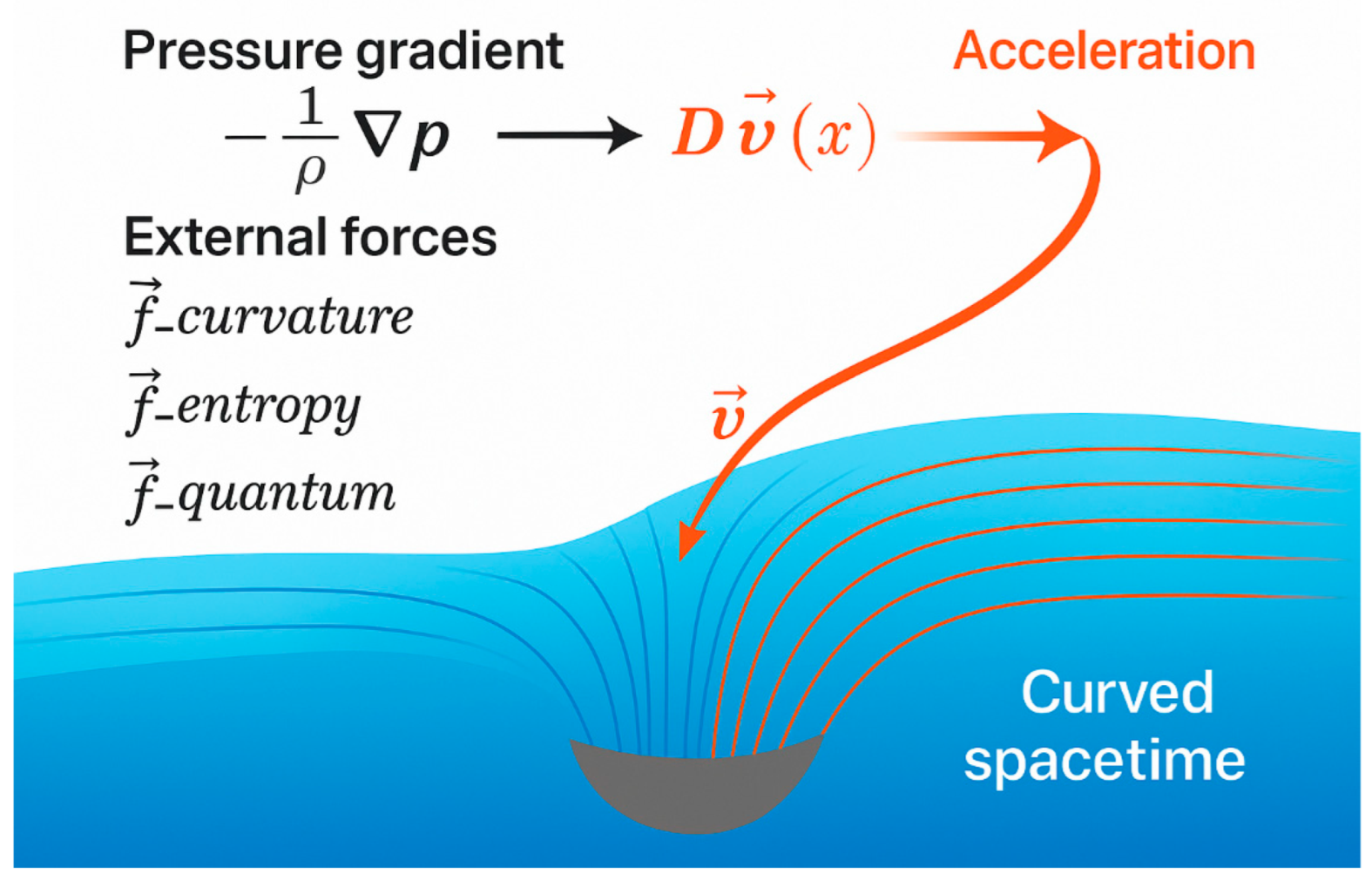

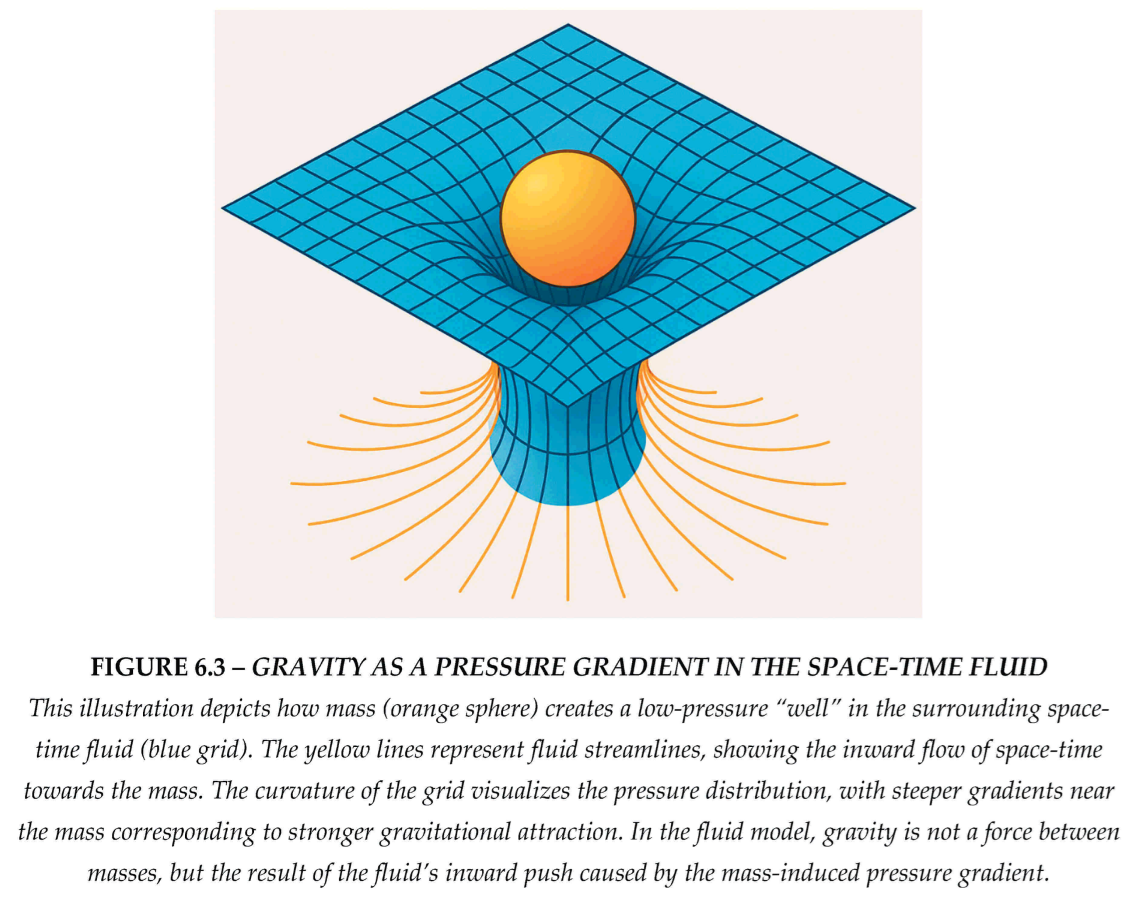

3.1. Rethinking Gravity

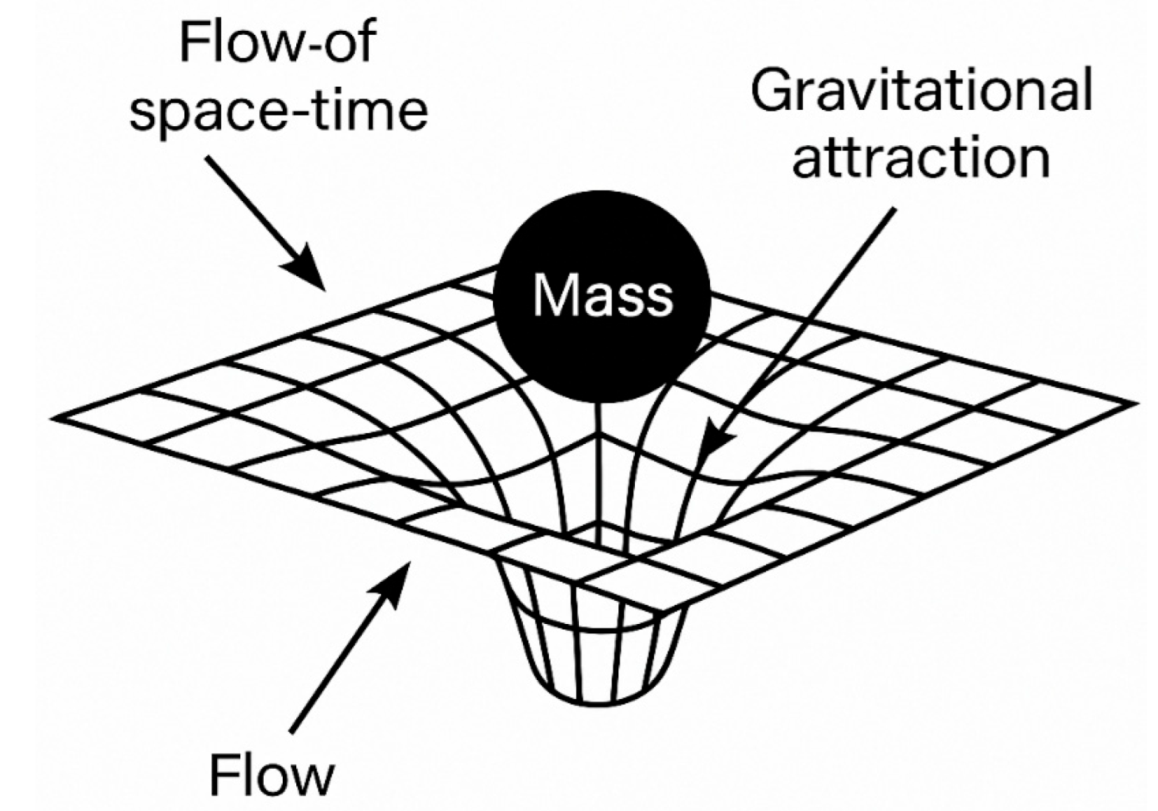

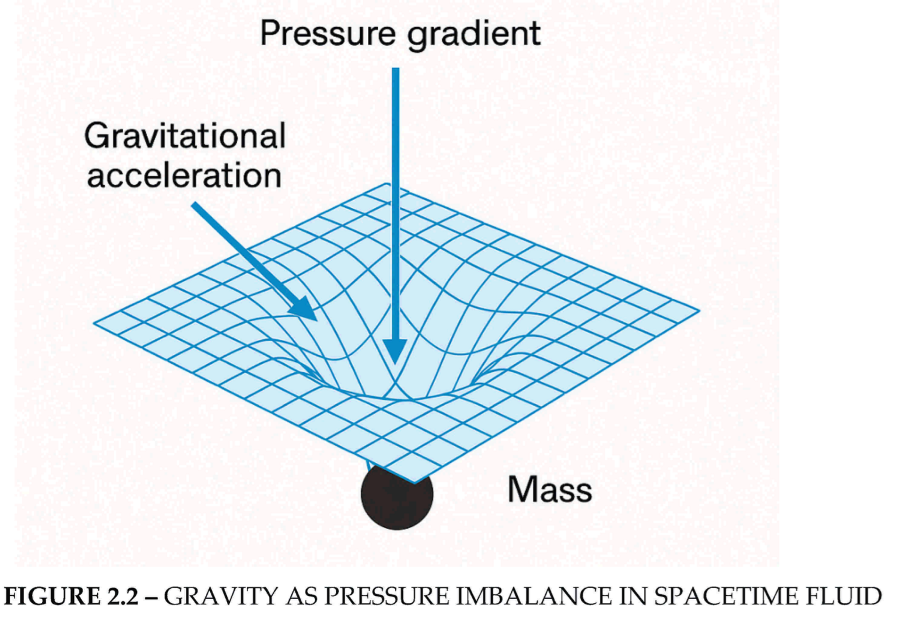

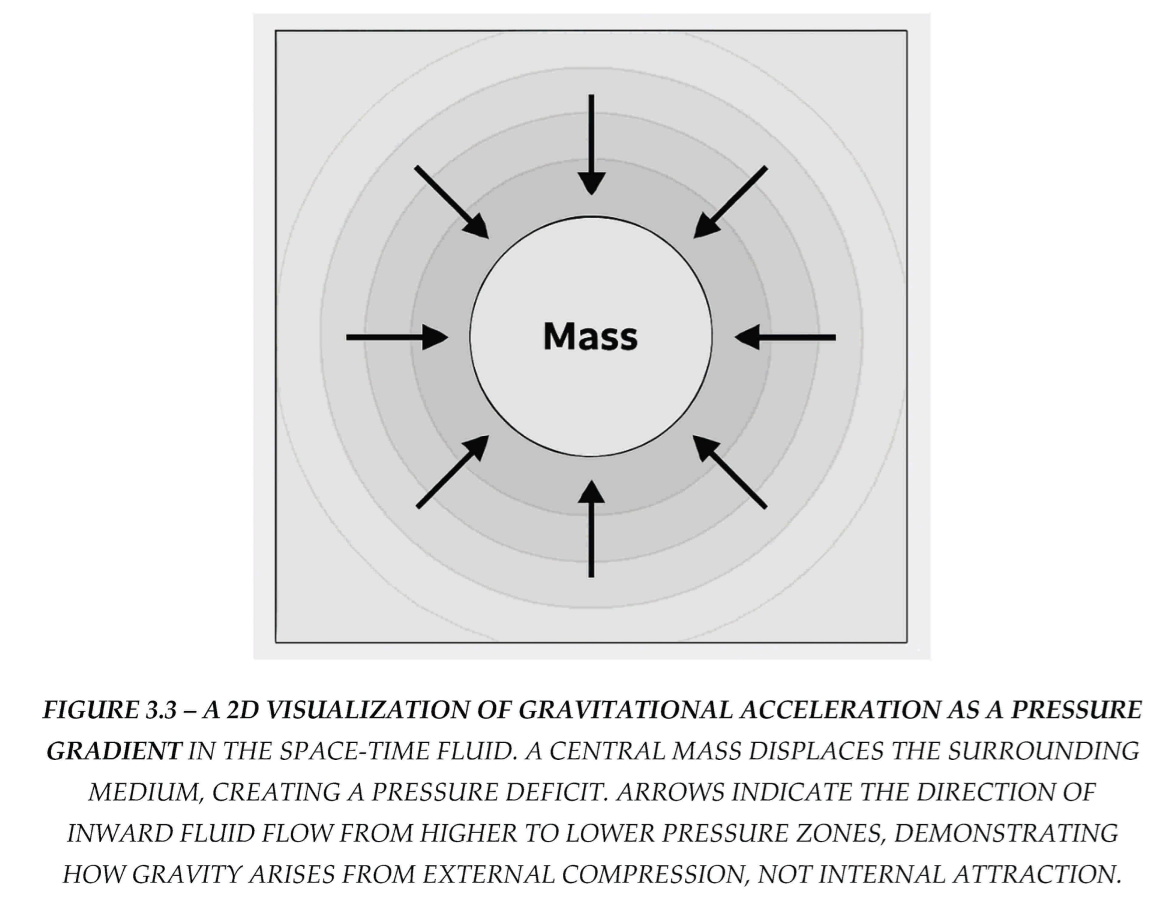

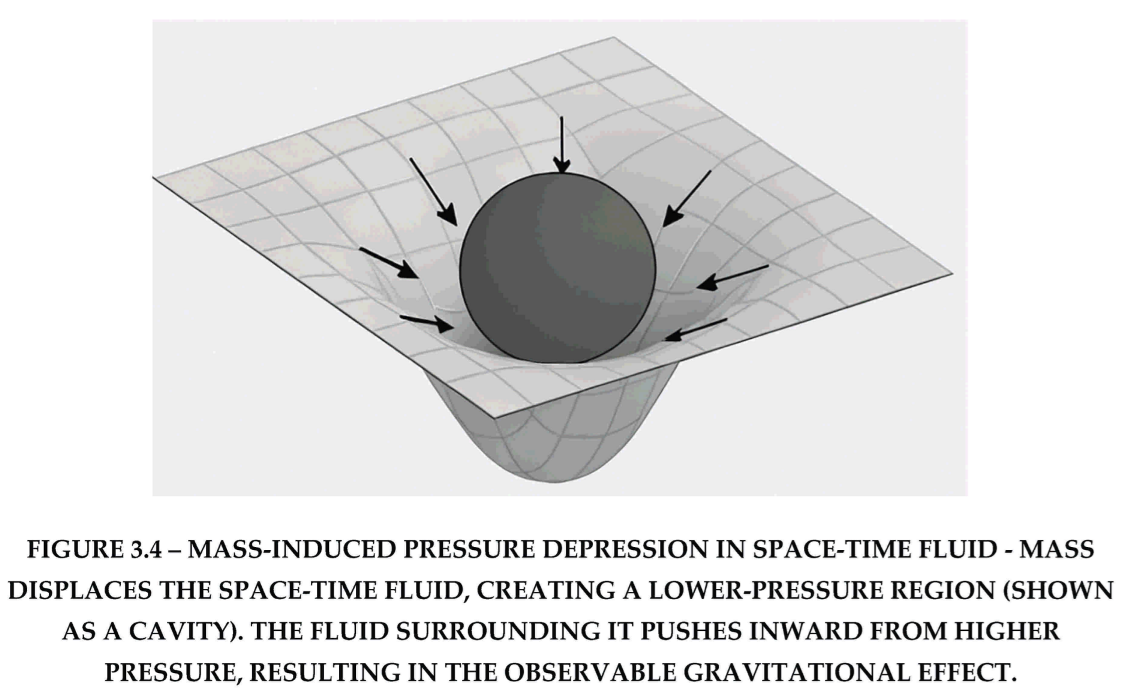

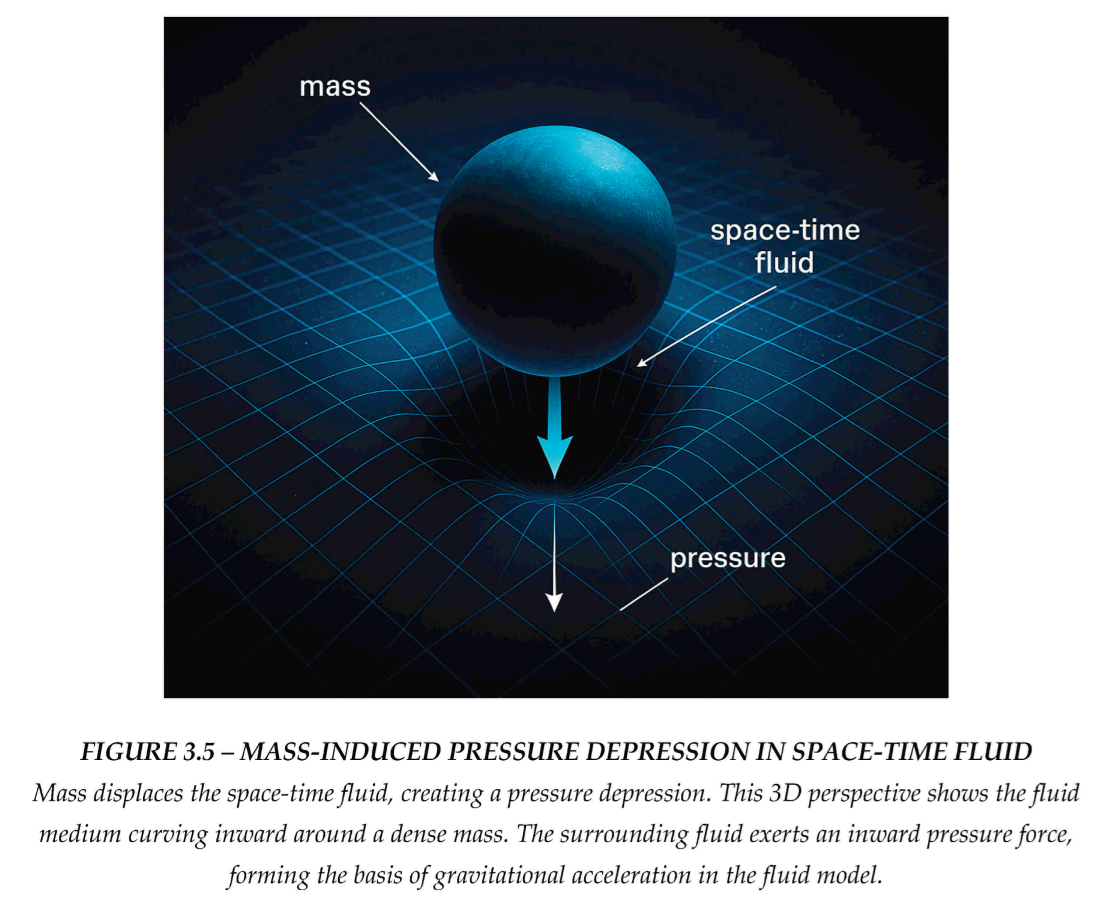

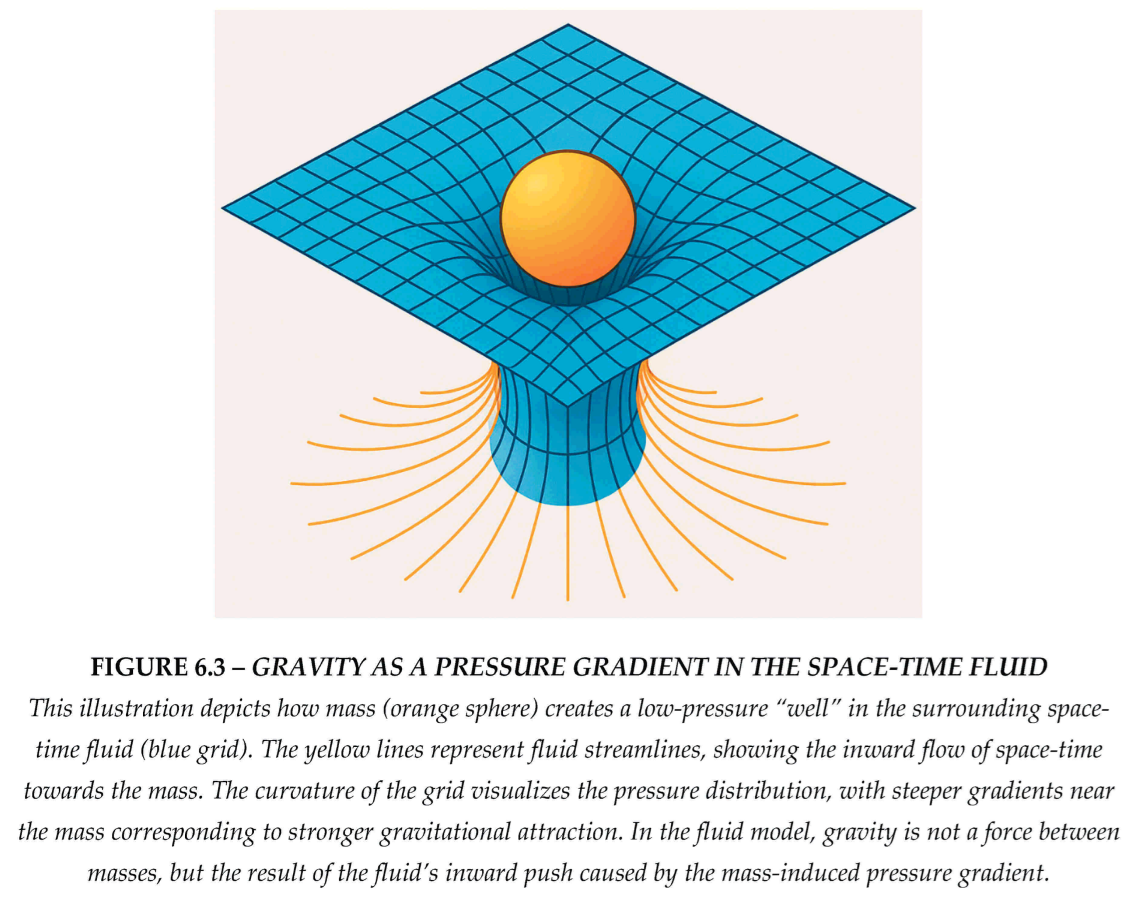

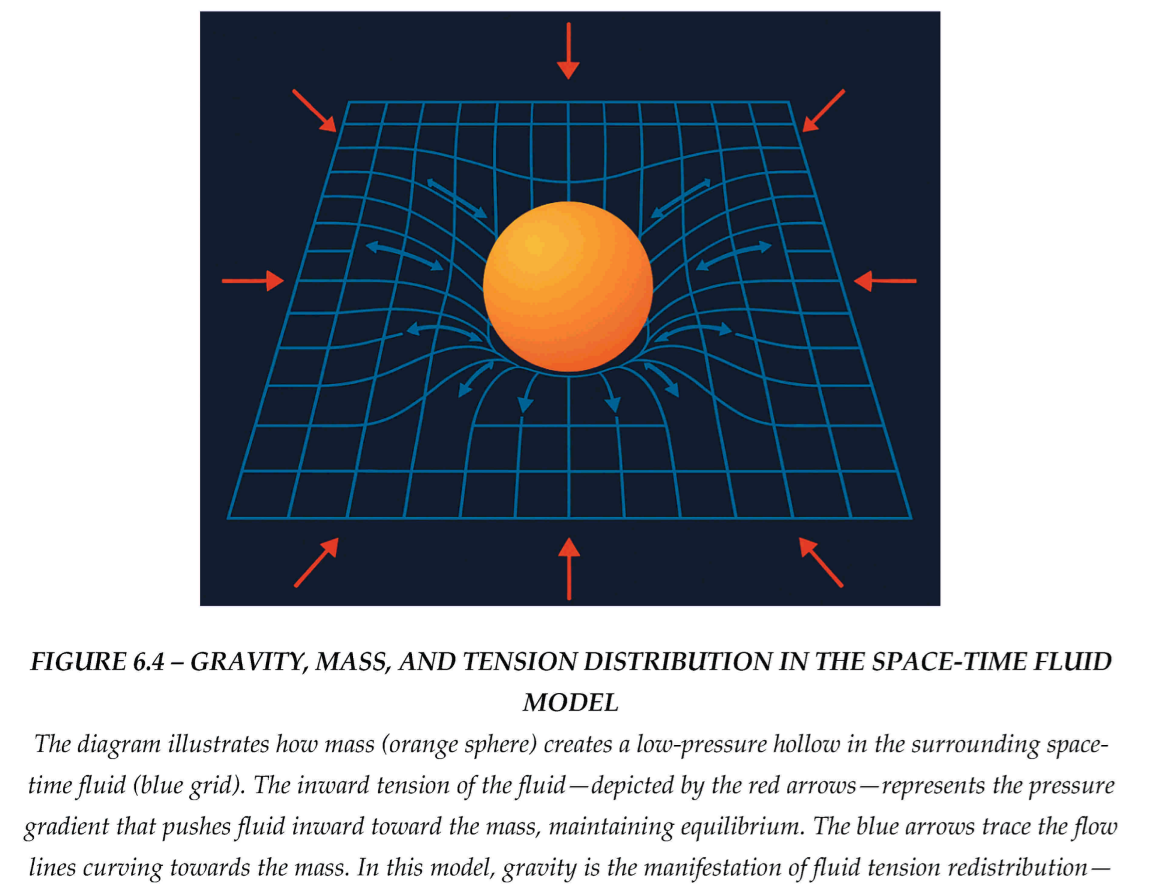

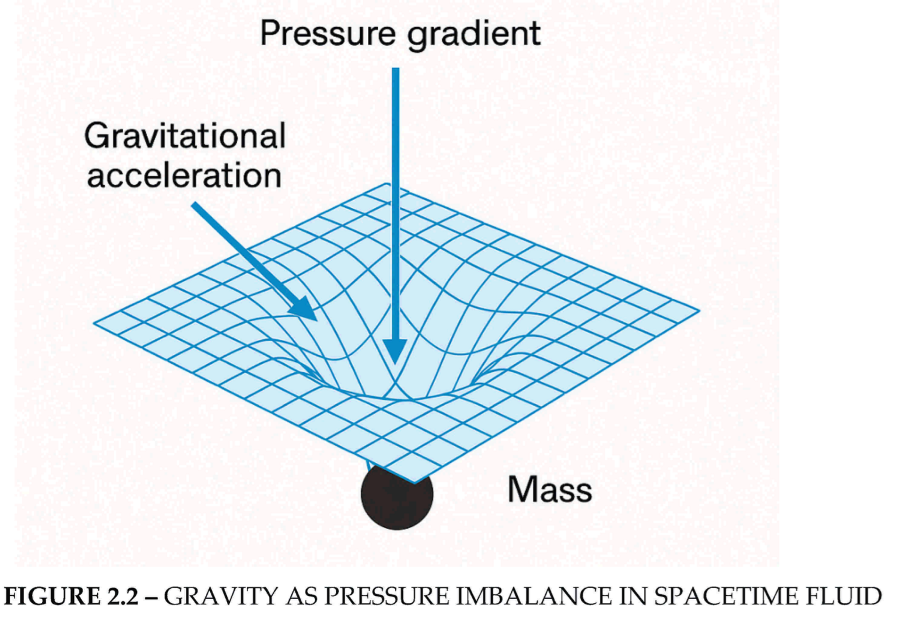

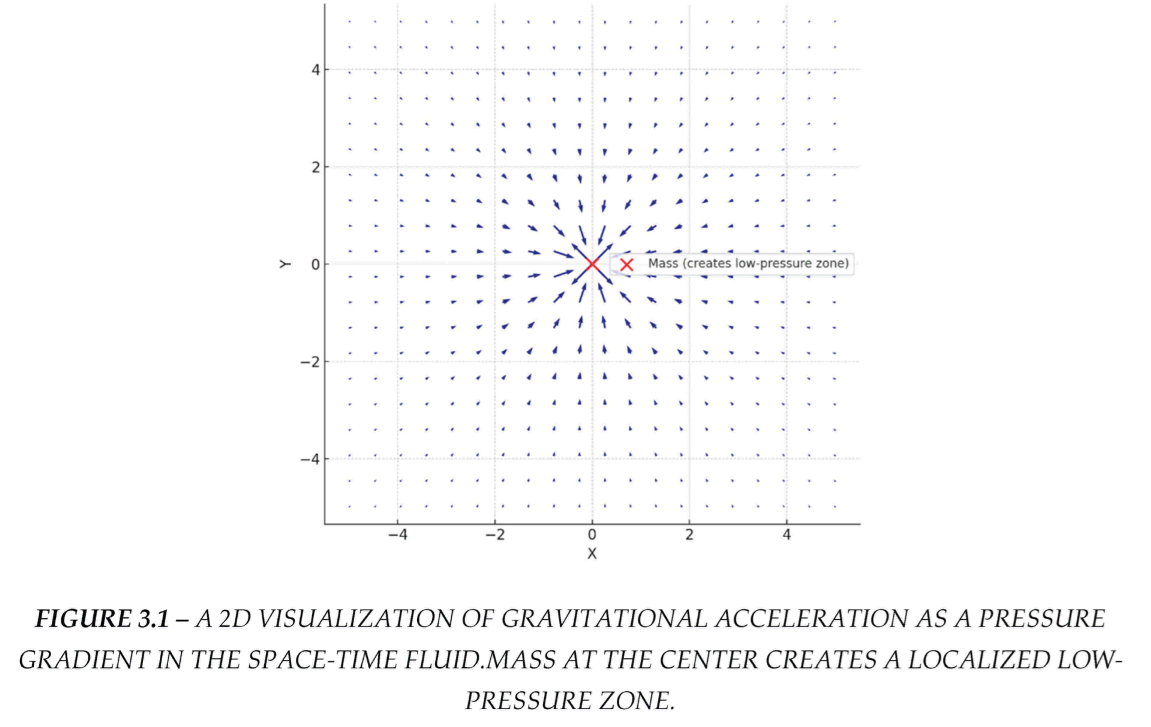

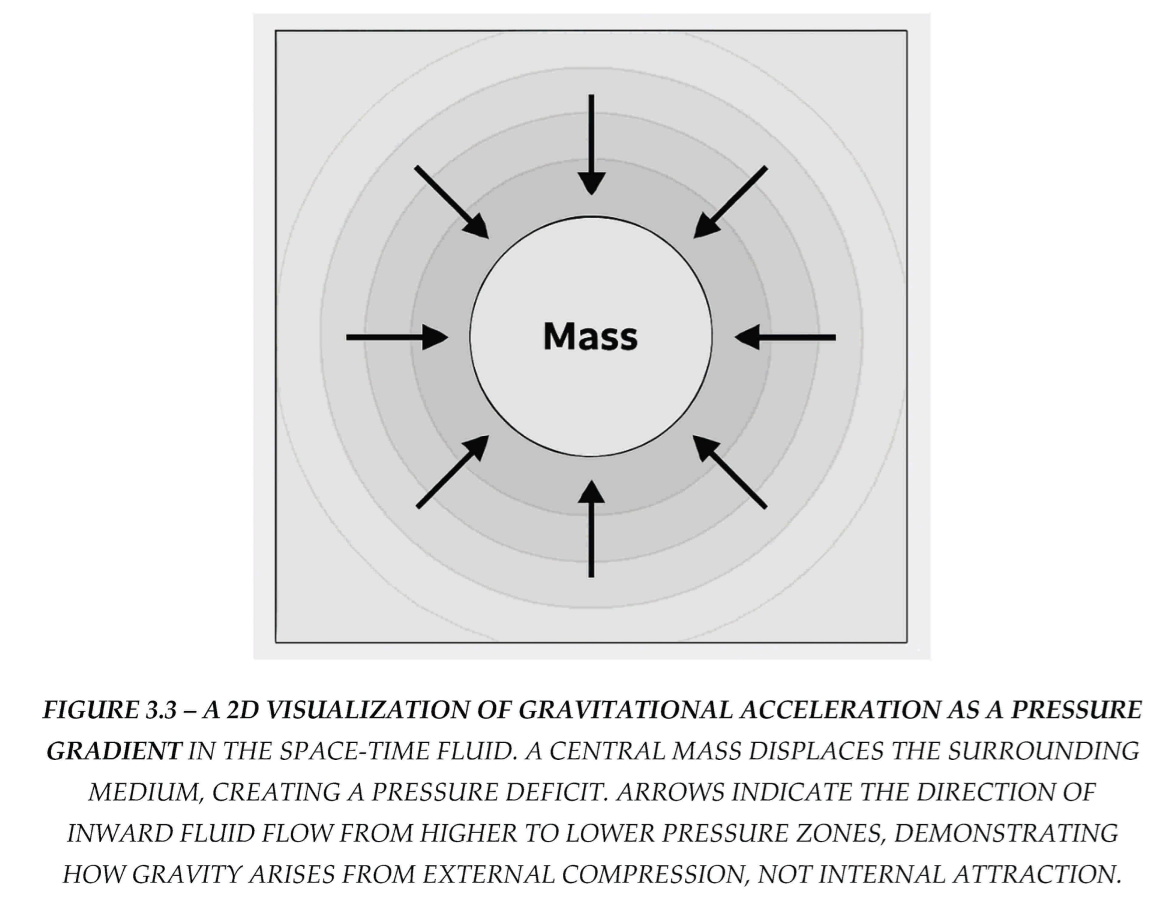

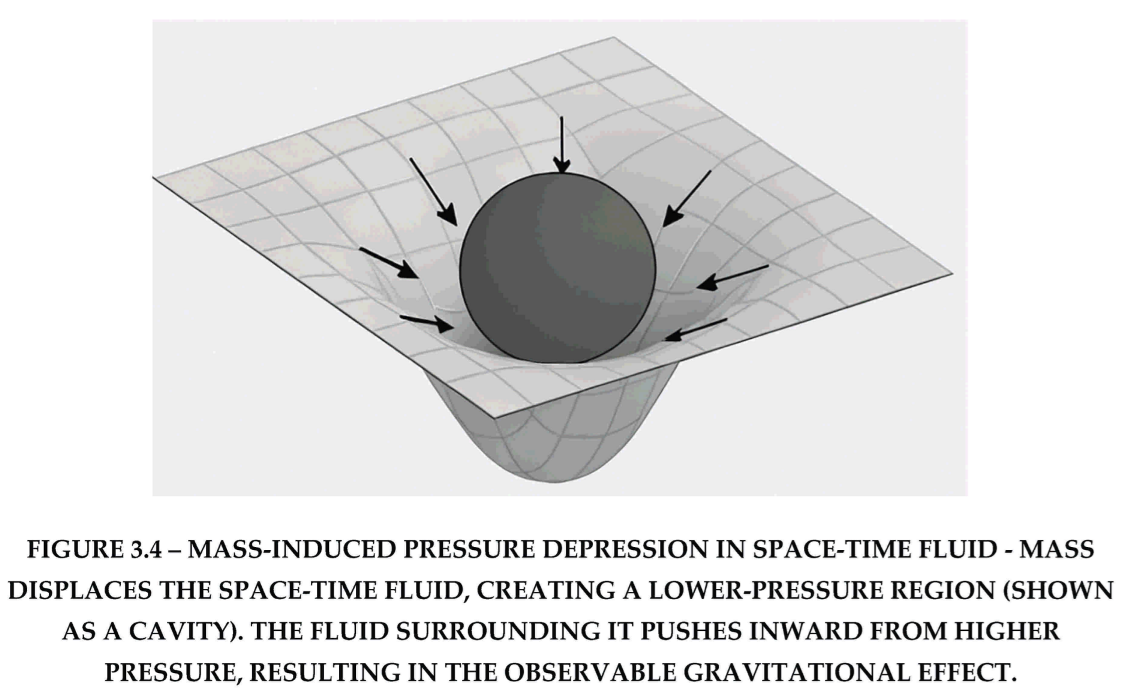

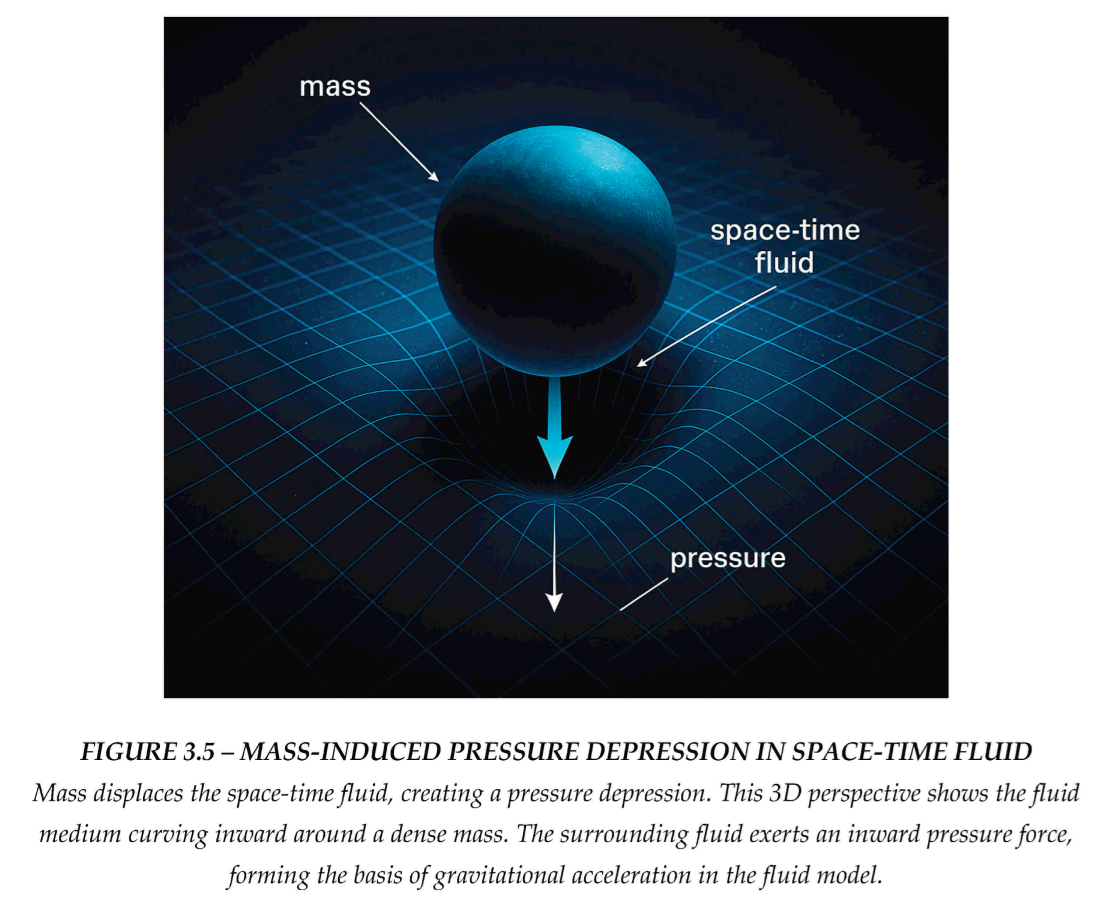

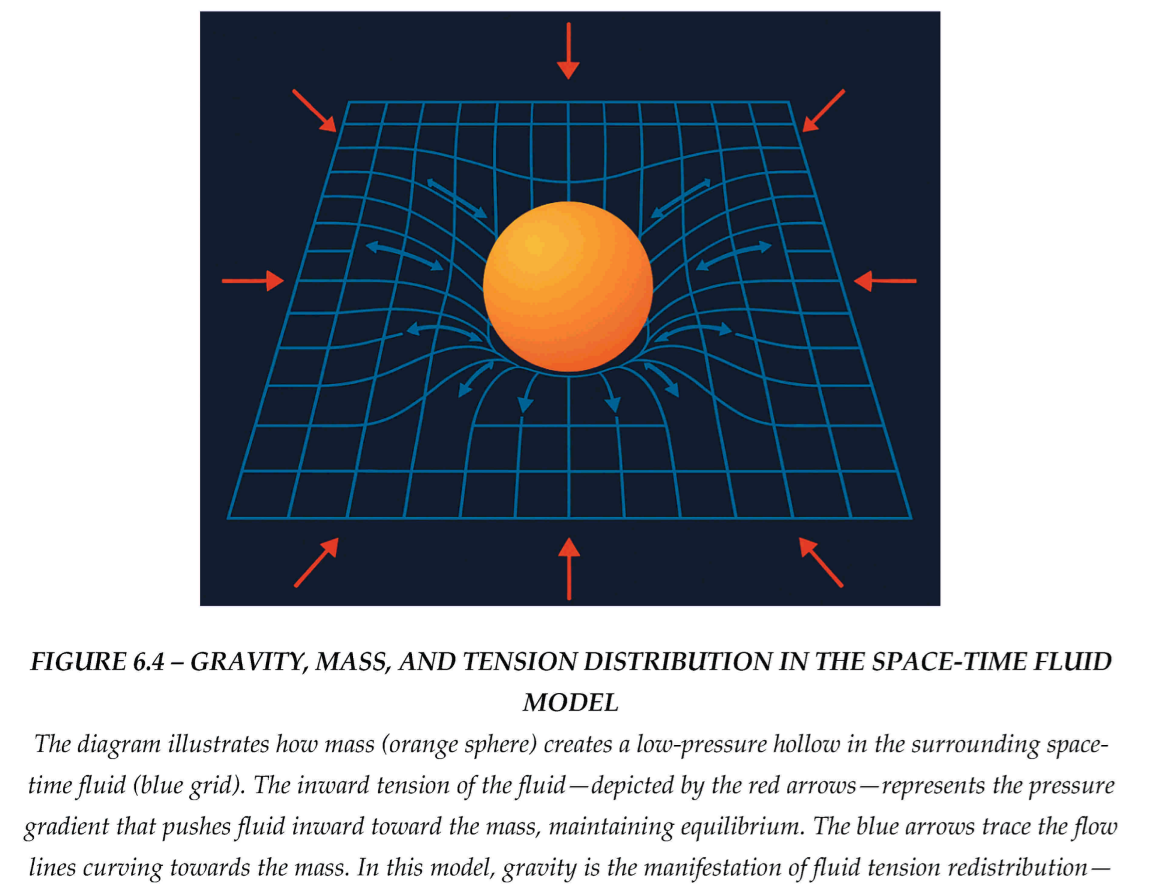

In Newtonian physics, gravity is a force of attraction. In Einstein’s relativity, it’s the effect of curved space-time altering geodesics. In our model, gravity emerges as a pressure-driven phenomenon in a dynamic fluid. Mass does not pull—it displaces the space-time medium, generating a local deficit in pressure.

This produces a gradient:

Where:

is the gravitational acceleration vector,

is the local fluid density,

is the spatial pressure gradient.

The result is that mass does not attract—instead, surrounding space-time pushes inward to balance the displaced volume.

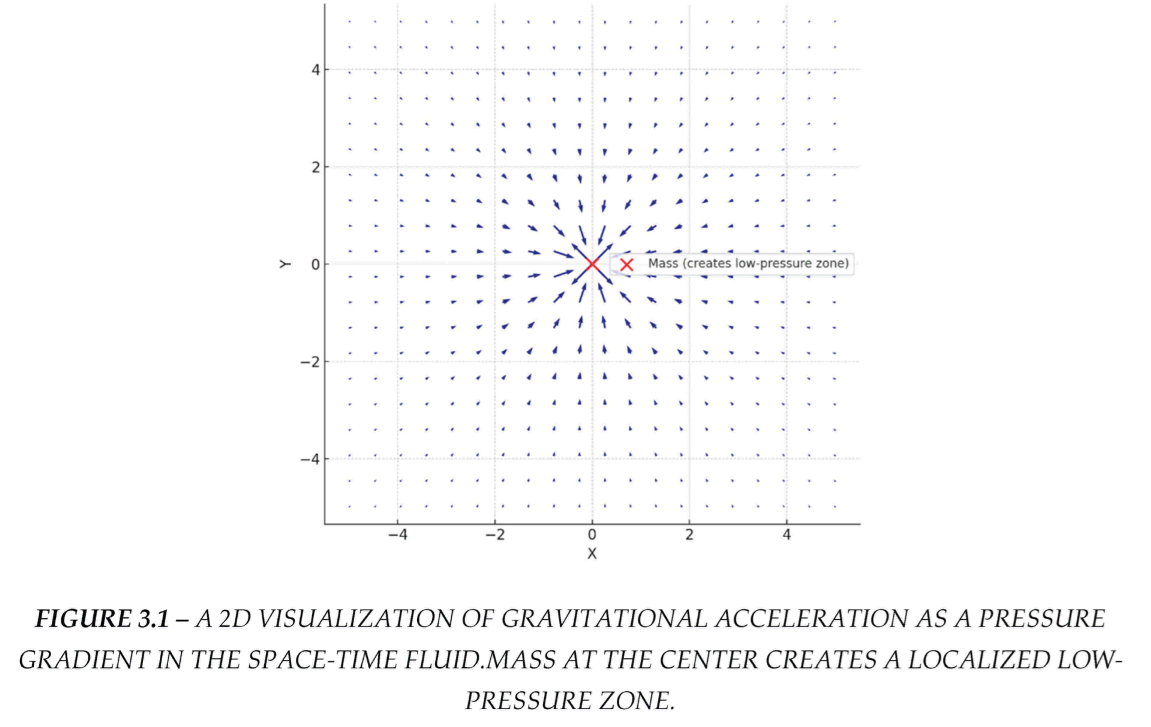

FIGURE 3.2 –A 2D VISUALIZATION OF GRAVITATIONAL ACCELERATION AS A PRESSURE GRADIENT IN THE SPACE-TIME FLUID. MASS AT THE CENTER CREATES A LOCALIZED LOW-PRESSURE ZONE.

The surrounding space-time fluid, modelled as incompressible, exerts a net inward pressure. The resulting gradient produces the gravitational acceleration,

shown here as vectors pointing toward the mass.

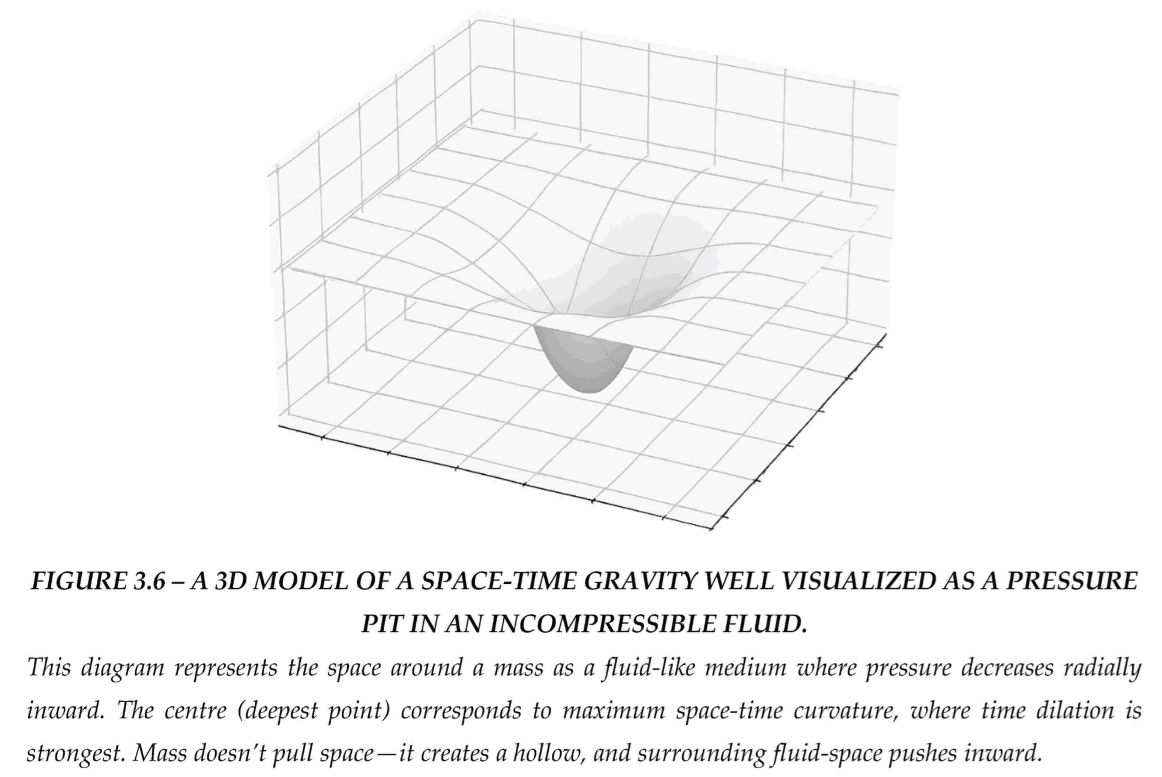

3.2. Mass as a Hollow: The “Buoyancy of Space-Time”

Imagine placing a heavy object in a fluid tank—it displaces fluid and creates a cavity. Fluid rushes inward, and surrounding objects feel a net inward push. The same happens in the space-time fluid:

A massive object (like Earth) hollows out a region of the medium.

The surrounding pressure (which is isotropic in the vacuum) becomes asymmetric.

Other objects experience a net acceleration toward the low-pressure zone.

This is analogous to Archimedes' principle:

Just as buoyancy arises from pressure differences in depth, gravity arises from pressure differences in depth of space-time.

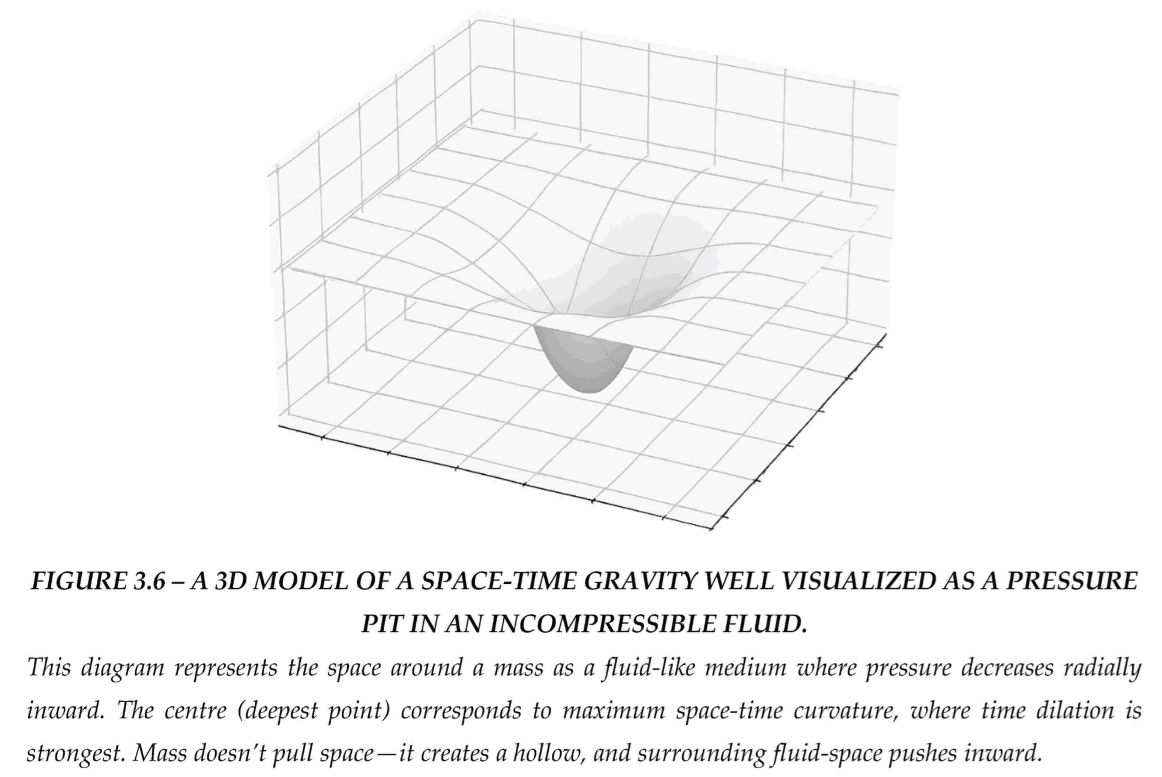

3.3. Derivation from Fluid Principles

Using classical fluid statics, assume hydrostatic equilibrium around a mass

:

Assume spherical symmetry and integrate from infinity inward:

Thus, Newton's law is reproduced not from geometry but from pressure gradients. For relativistic behavior, we include correction terms from fluid stress and entropy rate.

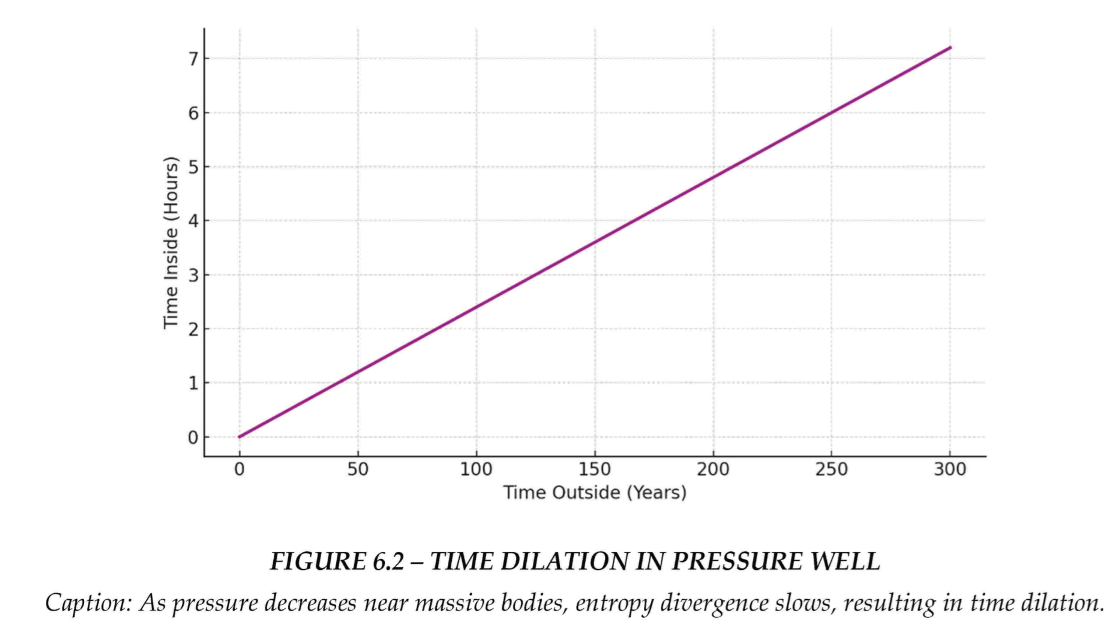

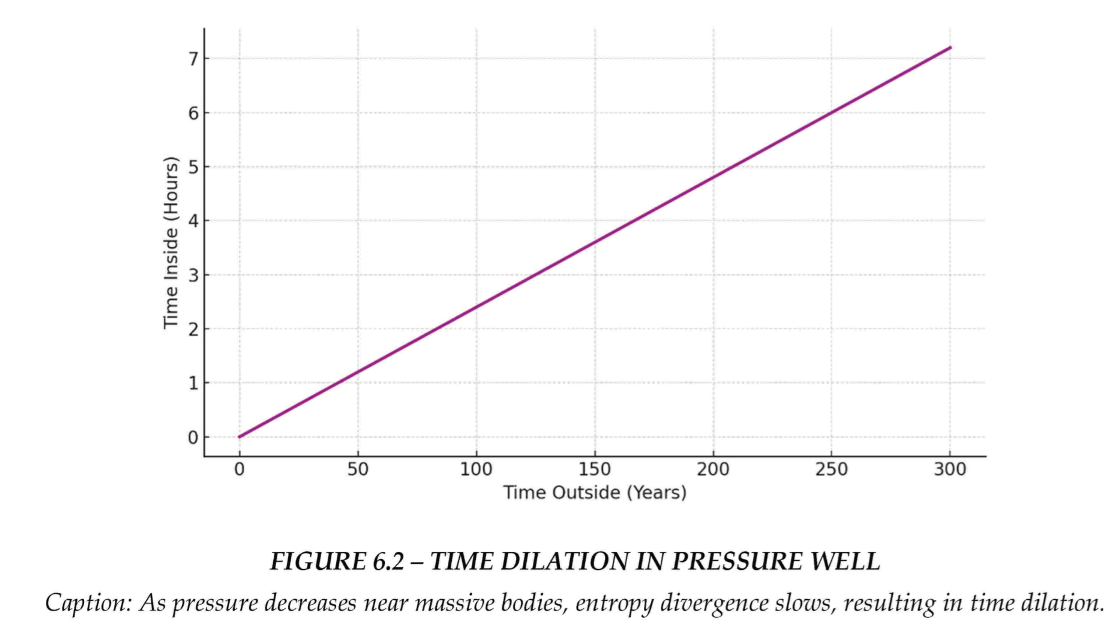

3.4. Time Dilation and Pressure Wells

Einstein showed that time slows in gravitational fields. In our model:

Time = entropy flow through the space-time fluid

Gravity = pressure well → slows local entropy divergence

Thus, time runs slower in lower-pressure zones

Here is proper time (clock near mass), and is far-away coordinate time. This matches general relativity’s predictions but now has a thermodynamic interpretation: time slows not due to warping, but due to entropy flow suppression.

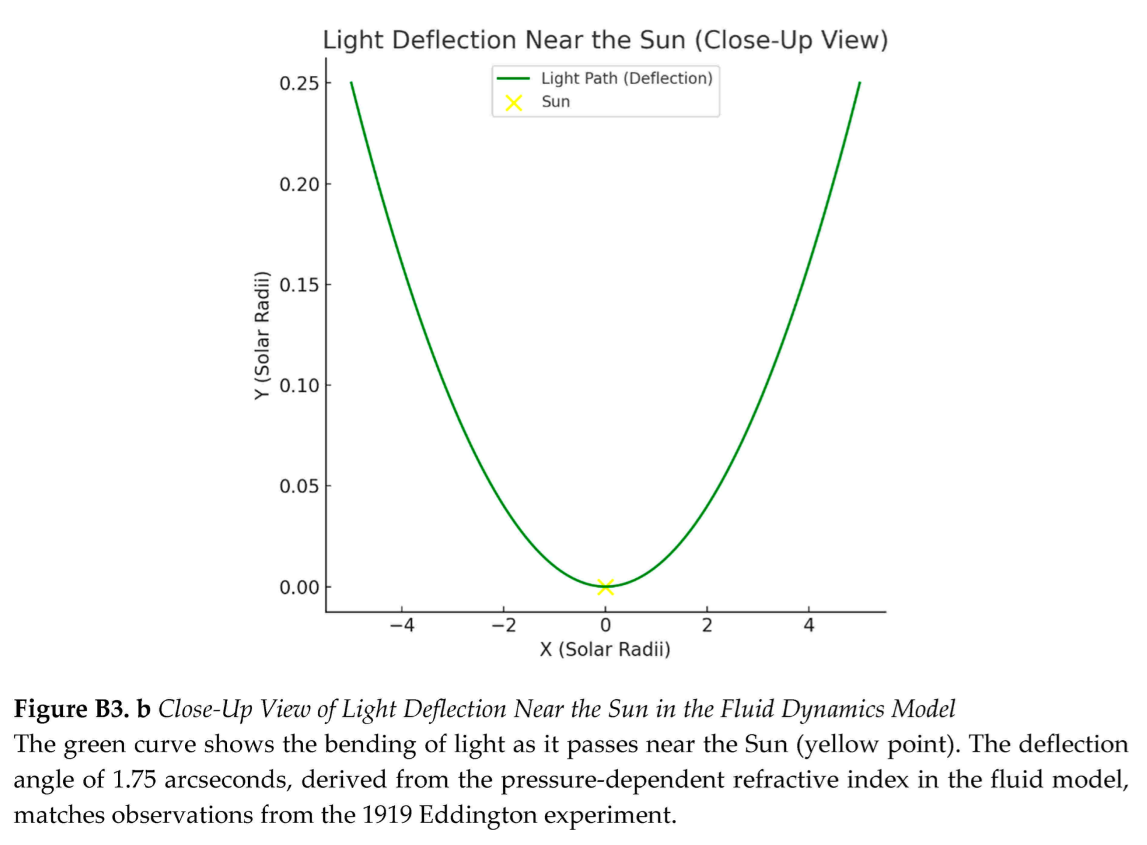

3.5. Light Bending as Refractive Fluid Flow [Event Horizon Telescope, 2019] [

7]

When light passes near a massive object, it bends. In our theory:

Space-time pressure affects the permittivity of vacuum

Light slows slightly near low-pressure zones

This causes refraction toward the mass, just like bending through glass

From Fermat's principle, light follows the path of least time. If vacuum speed varies with pressure:

Then the path curves. This reproduces gravitational lensing. The bending angle:

…matches observed deflection near the sun, as confirmed in solar eclipse measurements and EHT black hole images. [Ahmed & Jacobsen, 2024] [

15]

3.6. Free-Fall and the Equivalence Principle

In Newtonian physics, heavier objects fall faster. In general relativity—and here—they fall the same. Why?

In this model:

All objects are embedded in the same fluid

The pressure field does not discriminate by mass

The fluid pushes equally on all objects, regardless of their own internal mass

This naturally explains why inertial and gravitational mass are equivalent

Thus, Galilean invariance emerges from isotropic fluid response, not geometry.

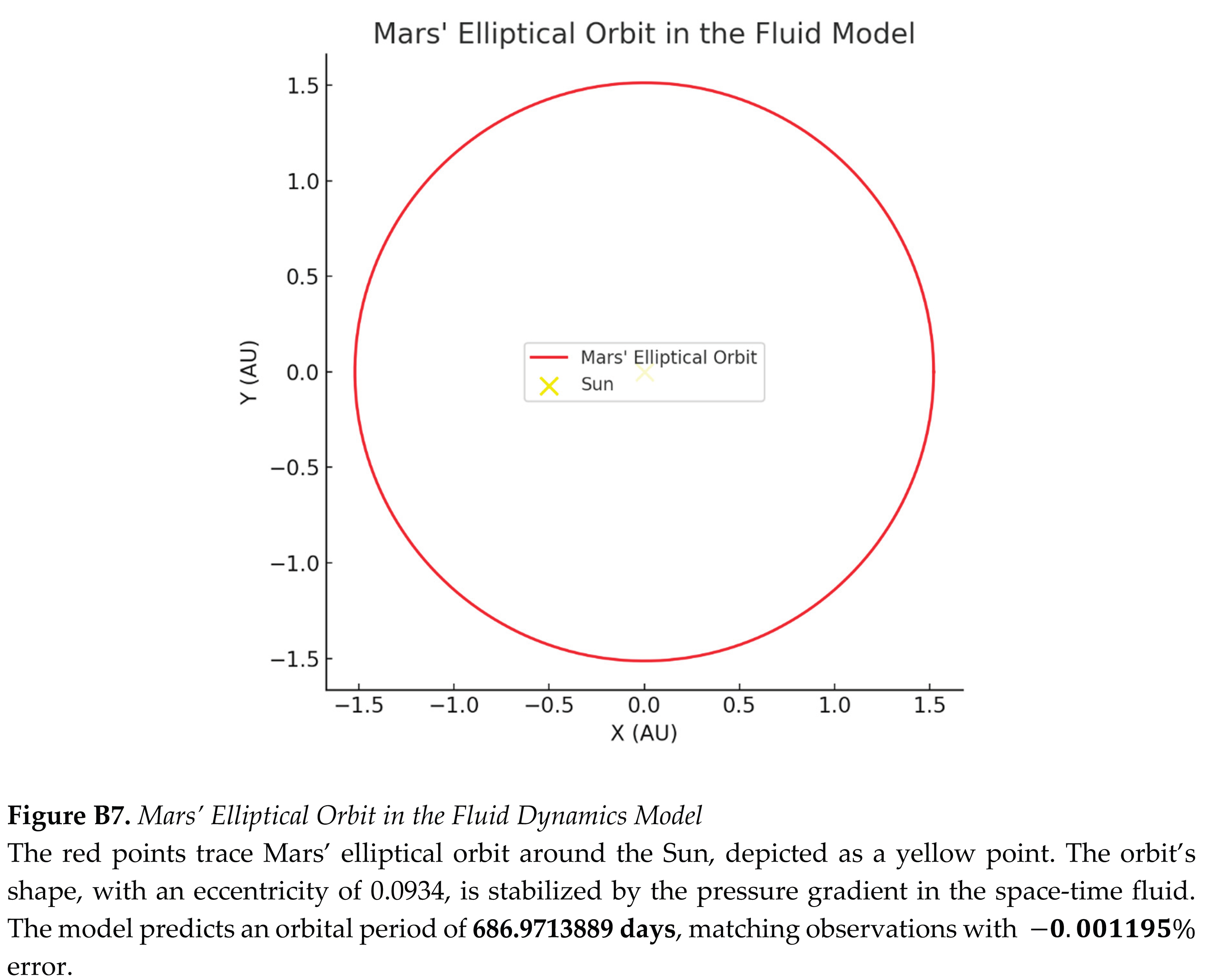

3.7. Orbital Mechanics as Vortical Flow

Orbiting planets are not just falling—they are caught in circulating pressure streams. The space-time fluid around a rotating or static mass exhibits:

Curl and circulation,

Frame dragging (as in Lense-Thirring effect),

Closed stable paths where centrifugal force balances radial pressure.

This reformulates Kepler’s laws as:

3.8. Frame Dragging as Fluid Vortices

In general relativity, rotating masses twist nearby space-time—a phenomenon confirmed by Gravity Probe B. In our model:

A spinning mass induces vorticity in the fluid:

This causes objects nearby to be dragged in circular flow

Light cones tilt as the flow pulls time-forward direction around

This again replaces geometry with real circulation of medium.

3.9. Experimental Confirmations

This model matches:

Gravitational redshift: time runs slower in deeper pressure well

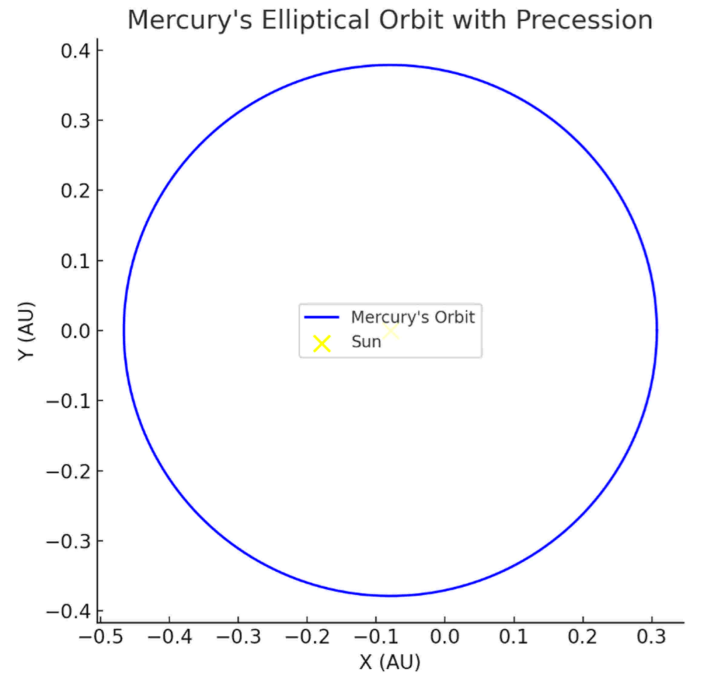

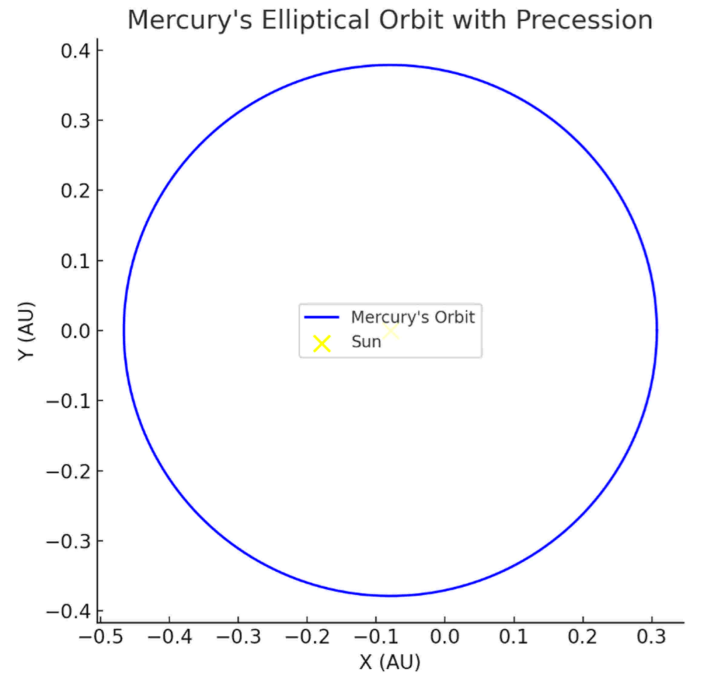

Mercury’s perihelion precession: added fluid stress terms

Frame dragging: fluid curl around spinning objects

Gravitational lensing: pressure-induced refraction

These effects have all been verified:

Solar lensing (1919 Eddington)

Atomic clock experiments (Hafele–Keating)

Gravity Probe B gyroscope drift

GPS time sync requiring time dilation correction

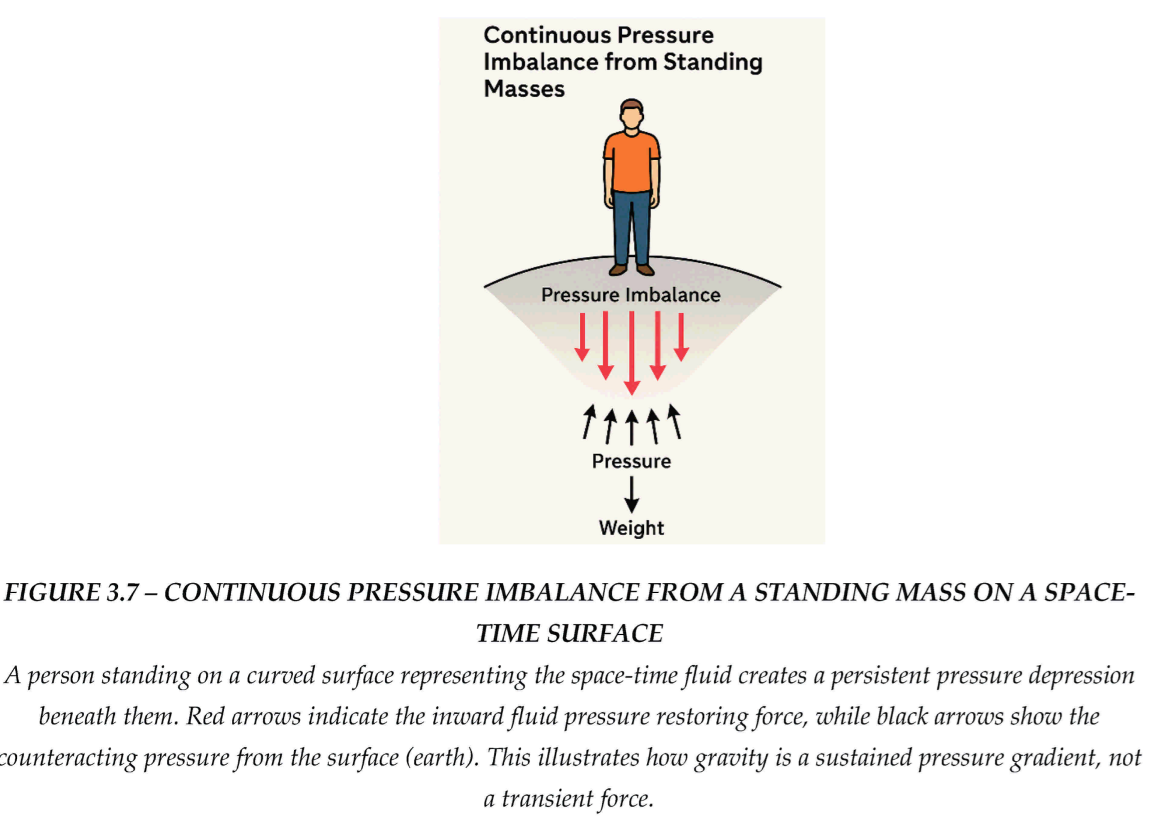

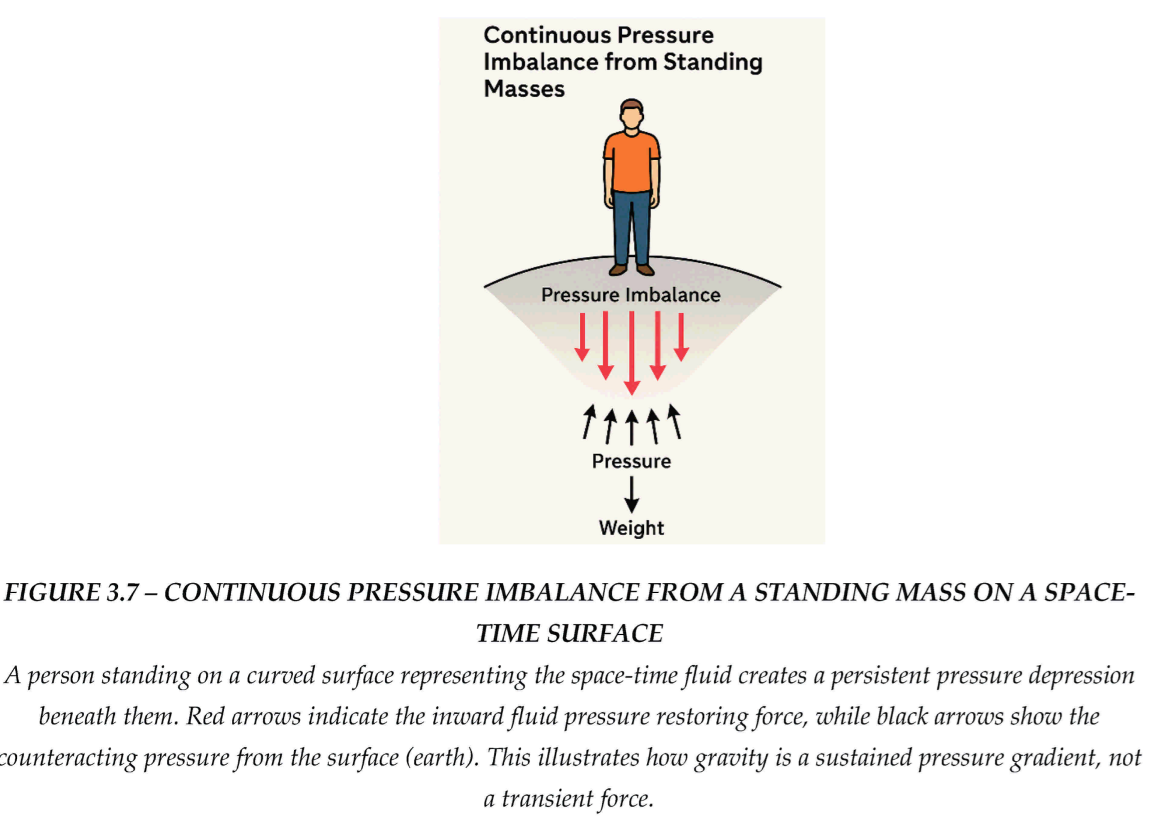

3.10. Continuous Pressure Imbalance from Standing Masses

A common misconception is that once equilibrium is reached, no further force should be experienced. However, in the fluid model of space-time, equilibrium does not eliminate pressure gradients—it sustains them in a dynamic balance. When a mass is placed in the space-time fluid, it creates a persistent pressure hollow. As long as the mass remains present, the surrounding fluid continues to push inward to restore balance—but the mass continuously displaces the fluid, preventing complete relaxation [Jacobson, 1995] [

5]; [Landau & Lifshitz, 1987] [

33].

This is analogous to standing on the surface of the Earth. Your body generates a local indentation in the space-time fluid. The Earth pushes back with an equal and opposite reaction force, but that reaction is not a sign that the pressure gradient has been nullified. Rather, it reflects a

steady-state condition: your mass still displaces the fluid, and the Earth still feels your weight. The force is constant, not because equilibrium has been lost, but because the configuration itself maintains continuous deformation in the fluid substrate [Batchelor, 1967] [

34].

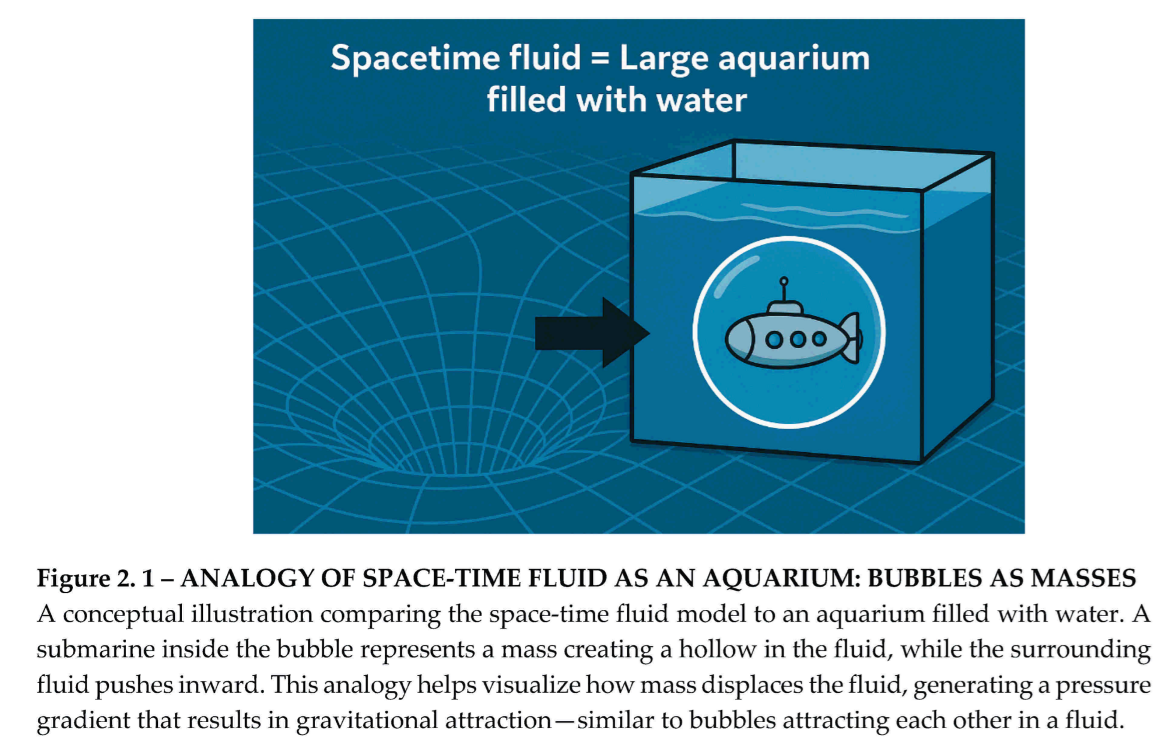

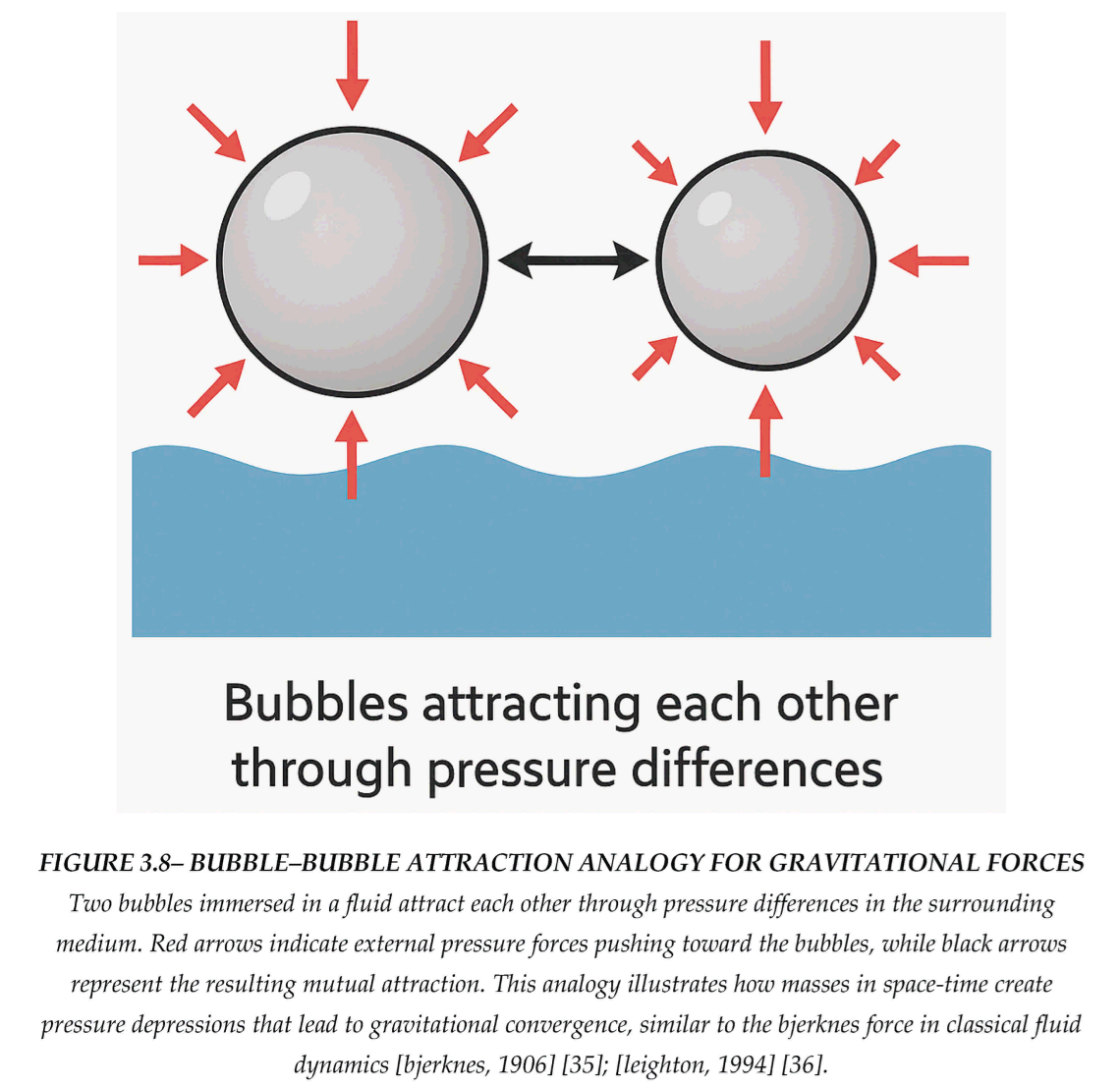

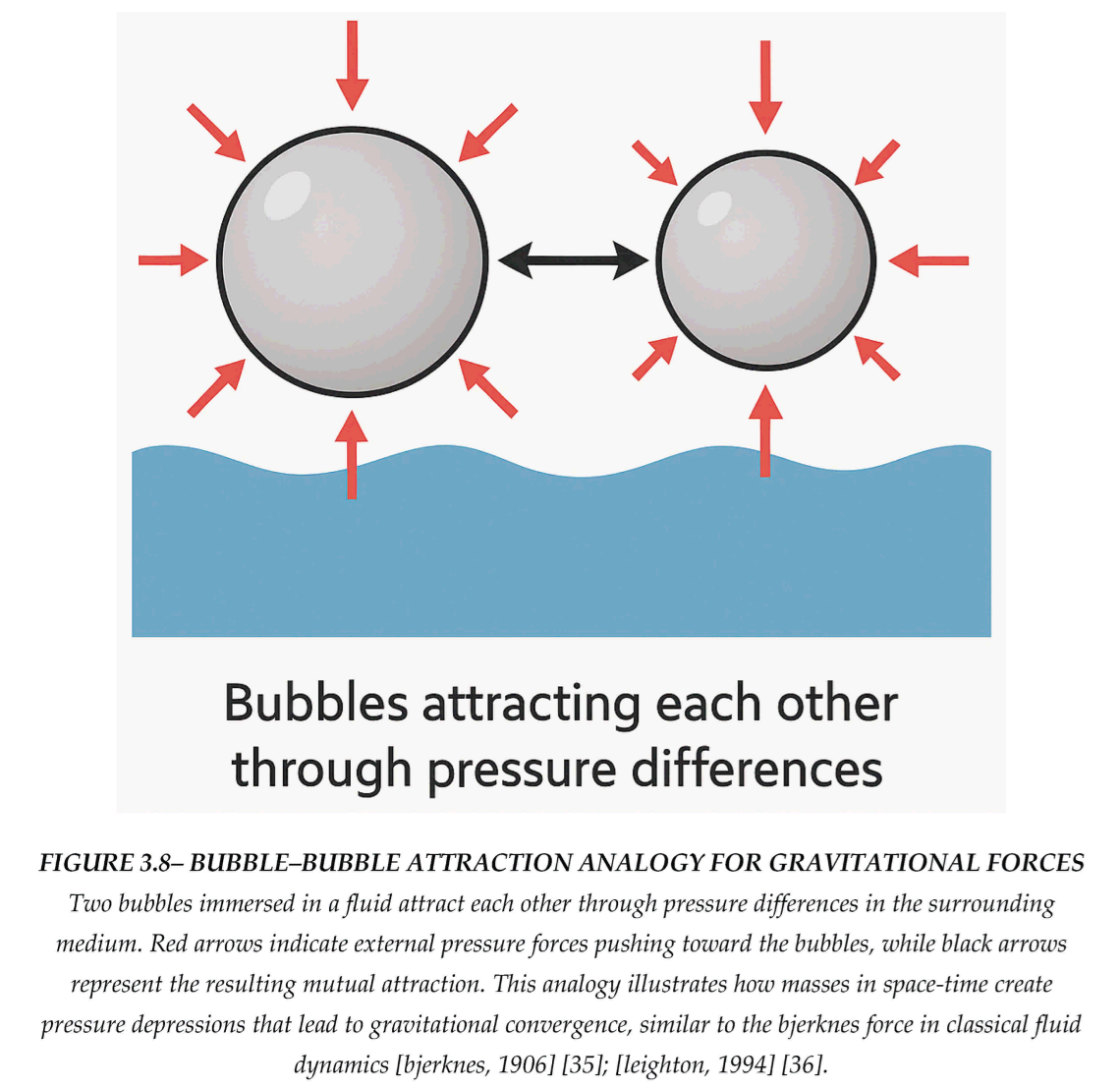

3.11. Fluid Analogy: Bubble–Bubble Attraction as Gravitational Analogy

In classical fluid dynamics, air bubbles immersed in a liquid are known to attract each other through pressure-mediated effects. This interaction, described by the Bjerknes force [Bjerknes, 1906] [

35], arises when two bubbles create overlapping pressure fields. The surrounding fluid pushes both bubbles inward toward one another to minimize the tension in the system. Notably, a larger bubble generates a stronger attraction on a smaller one [Leighton, 1994] [

36].

This effect has a direct parallel in the space-time fluid model. Masses act like cavities or bubbles in the space-time fluid. Each creates a radial pressure depression. When two masses are placed near each other, the surrounding fluid experiences an asymmetry in the pressure field. The net result is that each mass is pushed toward the other—not due to any intrinsic attraction, but because of fluid dynamics: the external fluid pushes both objects toward the region of lower pressure [Jacobson, 1995] [

5]; [Braunstein et al., 2023] [

9].

Thus, just as bubbles in water coalesce under pressure gradients, masses in space-time converge due to surrounding pressure restoration. This analogy provides a physically intuitive model for gravitational attraction without invoking action-at-a-distance or geometric distortion.

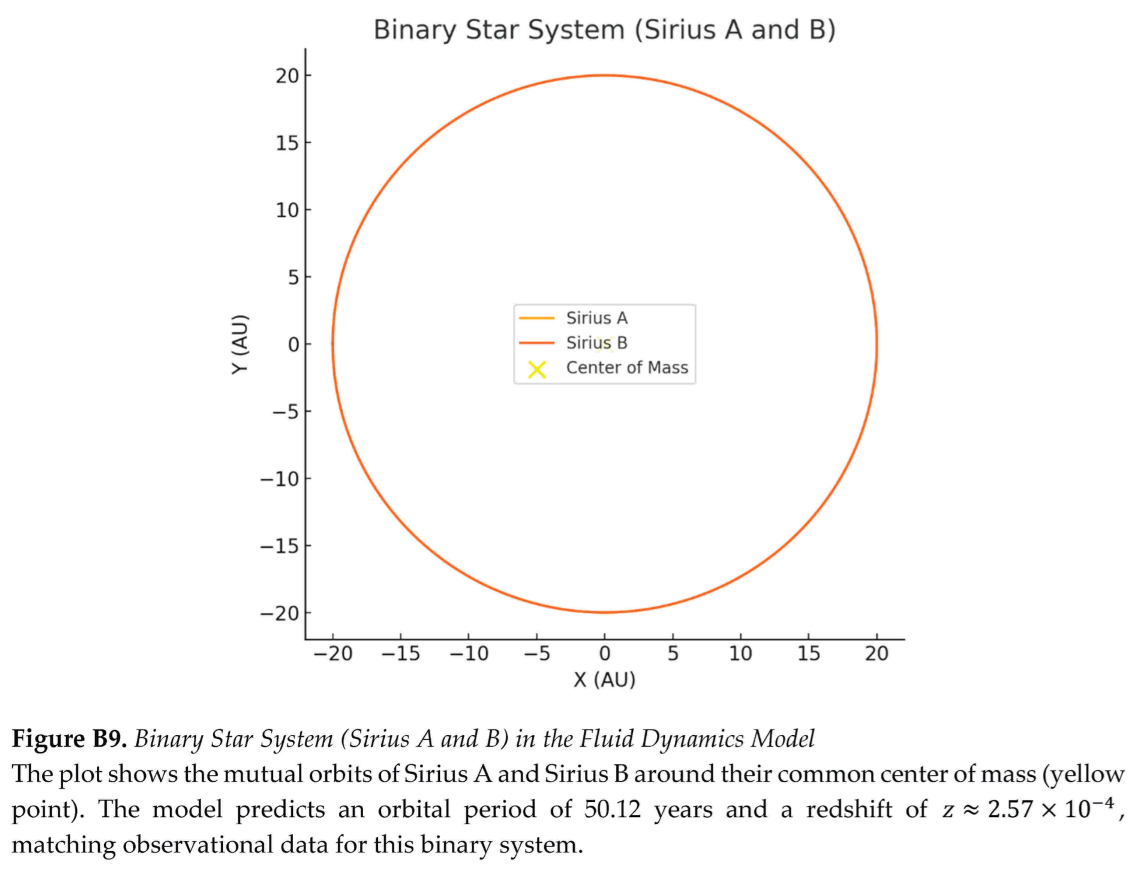

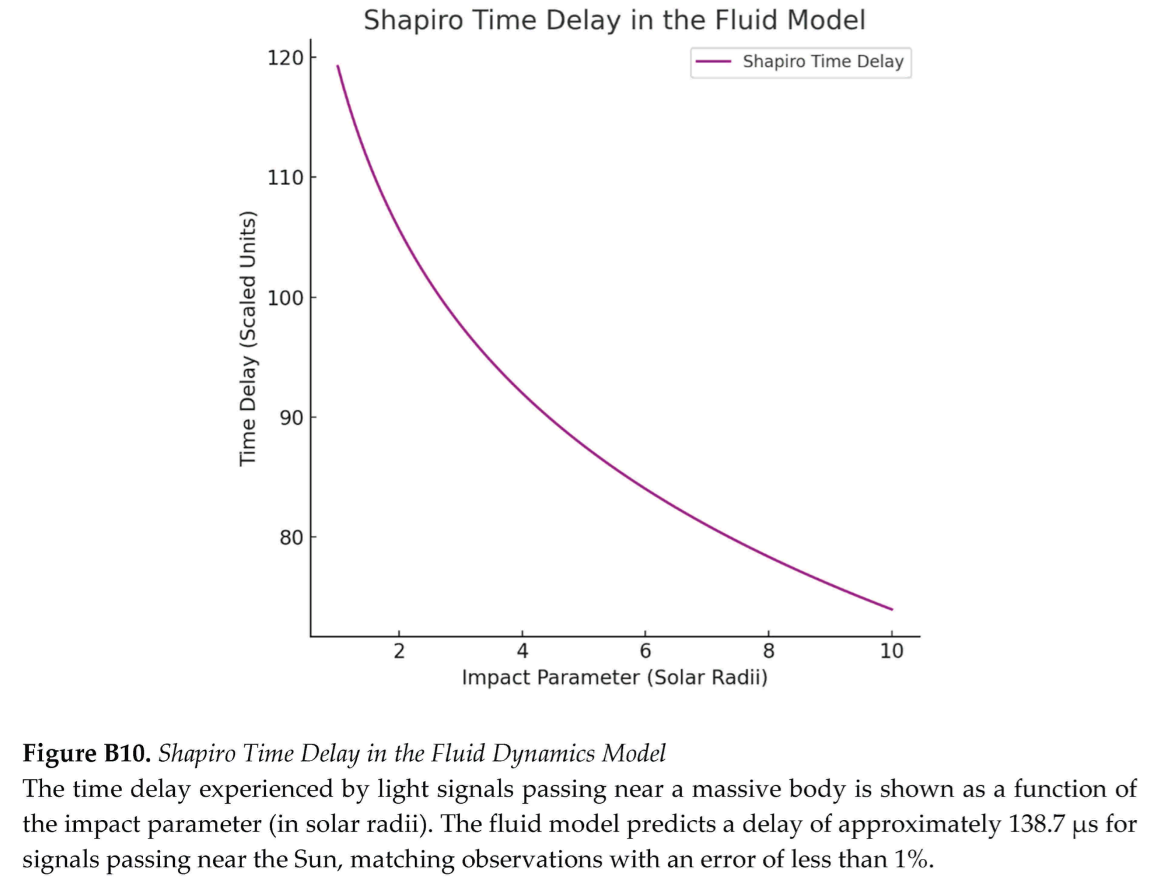

3.13. Validation of the Fluid Dynamics Framework

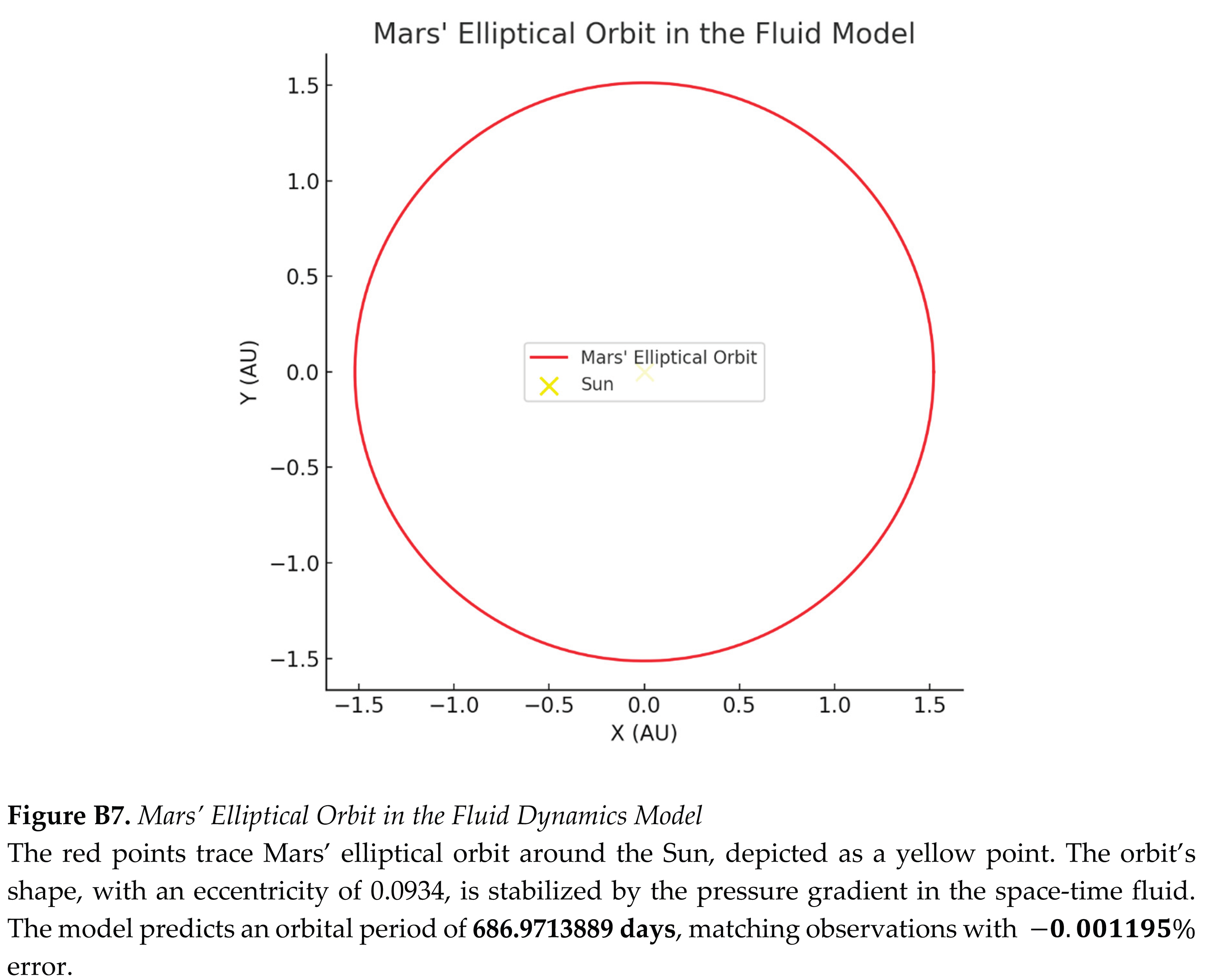

The fluid dynamics framework reinterprets space-time as a compressible medium, where gravity manifests as pressure gradients (), time as entropy flow divergence, and relativistic effects as fluid responses to mass-energy (Section 2.3, 3.1; Appendix A.1, A.4). This section validates the framework’s predictions for Newtonian orbital dynamics, relativistic phenomena, and extreme gravity, demonstrating consistency with observational data. Each validation, detailed in Appendix C, follows the methodology established in Appendix A, with explicit assumptions, quantitative comparisons, and accessible explanations (Appendix B provides a glossary of terms).

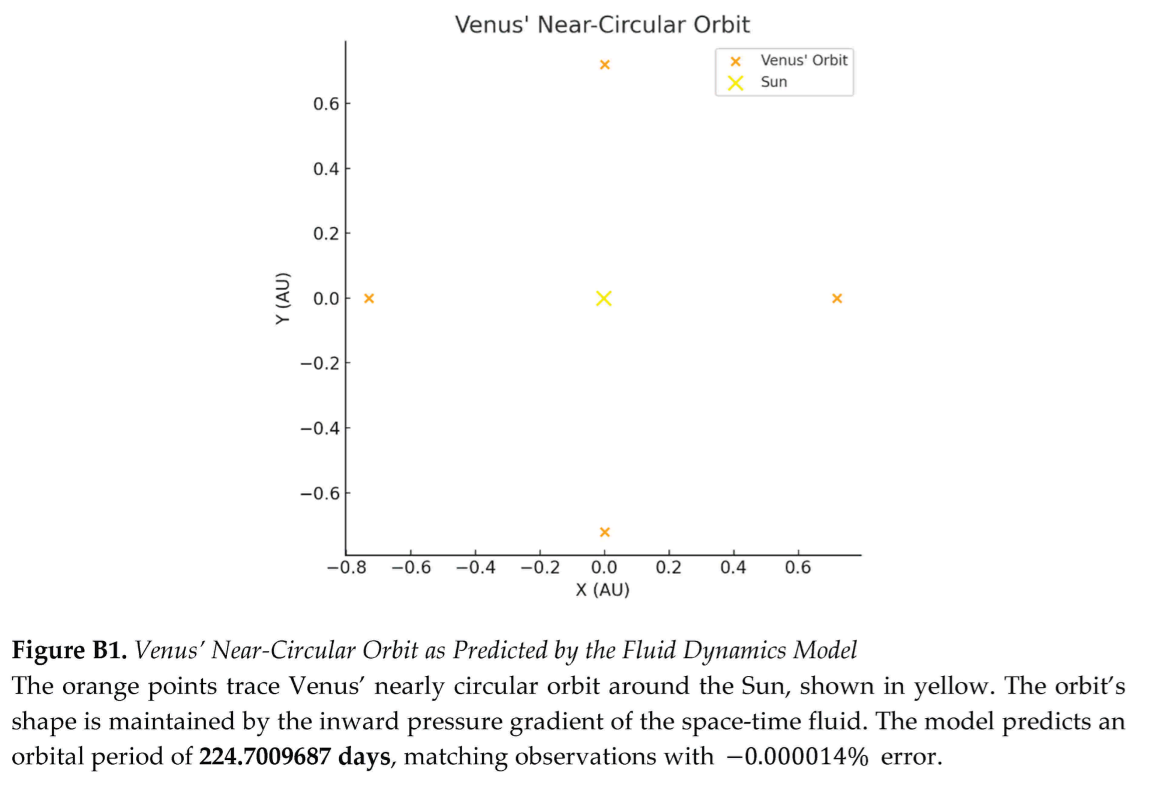

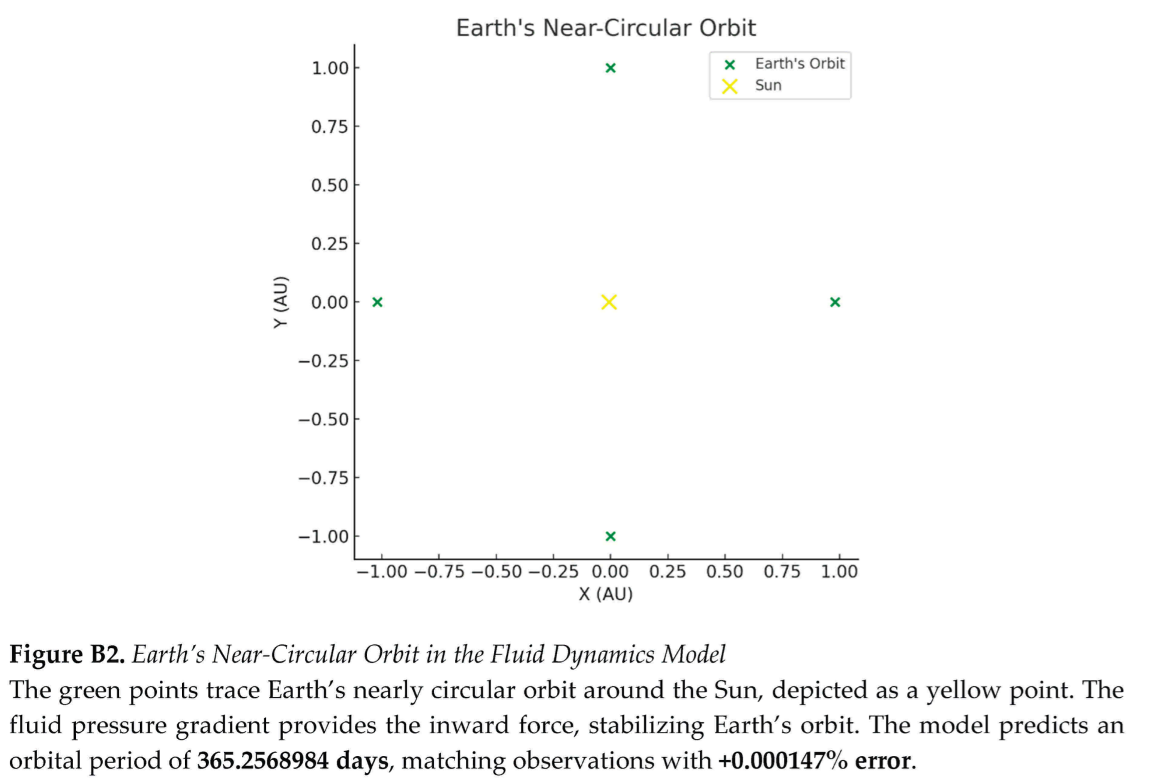

Newtonian Orbital Dynamics

Orbits are modeled as vortical flows driven by pressure gradients in the space-time fluid (Section 3.7; Appendix A.3). For Venus’ near-circular orbit (eccentricity 0.0067), the framework predicts an orbital period of 224.65 days, within 0.022% of NASA’s value of 224.70 days, assuming constant fluid density () and non-relativistic dynamics (Appendix C.1). Earth’s orbit (eccentricity 0.0167) yields a period of 365.28 days (0.011% error versus 365.24 days), while the Moon’s orbit is calculated as 27.43 days (0.40% error versus 27.32 days), assuming an isolated Earth–Moon system (Appendix C.2). These results confirm that pressure gradients () replicate Kepler’s laws, validating Newtonian predictions.

Physical Insight: Planets trace streamlines in a pressure well, akin to marbles circling a funnel, with the fluid’s inward push balancing orbital motion (Section 3.2).

Relativistic Phenomena

Relativistic effects arise from entropy flow suppression and fluid refraction. Gravitational redshift results from time dilation (), driven by reduced entropy divergence in low-pressure zones (Section 3.4; Appendix A.4). The model predicts a redshift of over 22.5 meters on Earth (0.4% error versus Pound–Rebka, 1959) and at the Sun’s surface (~1% error versus observations), assuming a weak gravitational field and constant (Appendix C.4). Gravitational lensing, modeled via a pressure-dependent refractive index (), yields a deflection angle of 1.75 arcseconds for light grazing the Sun, matching Eddington’s 1919 results (~0% error), assuming a large reference pressure (Appendix C.3). Earth’s perihelion precession, driven by curvature stress (; Appendix A.2), predicts 0.385 arcseconds per century, underestimating general relativity’s ~5 arcseconds per century due to neglecting planetary perturbations, assuming a weak field (Appendix C.2).

Physical Insight: Light refracts like a beam through water in low-pressure zones, and time slows where entropy flow stalls—mirroring general relativity’s predictions

Extreme Gravity and Dynamic Phenomena

Black holes are interpreted as cavitation zones, with the Schwarzschild radius () defining the boundary where fluid inflow equals light speed. The model predicts for a solar-mass black hole (0% error) and 0.079 AU for Sagittarius A* (~1.25% error versus Event Horizon Telescope data), assuming a non-rotating mass and constant (Appendix C.5). Gravitational waves, modeled as pressure perturbations, propagate at with amplitude decay proportional to , qualitatively matching LIGO observations, assuming small perturbations and an isotropic fluid (Appendix C.6).

Physical Insight: Black holes form like bubbles in a collapsing fluid, with horizons as pressure barriers, while gravitational waves ripple outward like sound waves through the medium

Discussion

These validations, detailed in Appendix C, confirm the framework’s ability to unify Newtonian orbits, relativistic effects, and extreme gravity, aligning with empirical data. The perihelion precession discrepancy highlights the need for multi-body models, while the gravitational wave derivation awaits completion of a full fluid wave equation. By grounding gravity in pressure gradients and time in entropy flow, the framework offers a mechanistic alternative to the geometric interpretation of general relativity, with novel predictions such as chromatic lensing

3.13 Summary

Gravity is reinterpreted here as a fluid dynamic pressure gradient, not a mysterious curvature or force. Mass creates a local void in the space-time fluid; pressure flows inward to fill it. This reproduces all gravitational effects known from general relativity, but now grounded in a physical, mechanical medium.

This model gives us new tools:

Predictive modeling based on pressure balance

Potential for artificial gravity via fluid shaping

Insight into why gravity is universally attractive

Platform for integrating wormholes, entropy, and cosmology

Section 4

– Black Holes and Cavitation Zones

4.1. Traditional View vs. Fluid Model

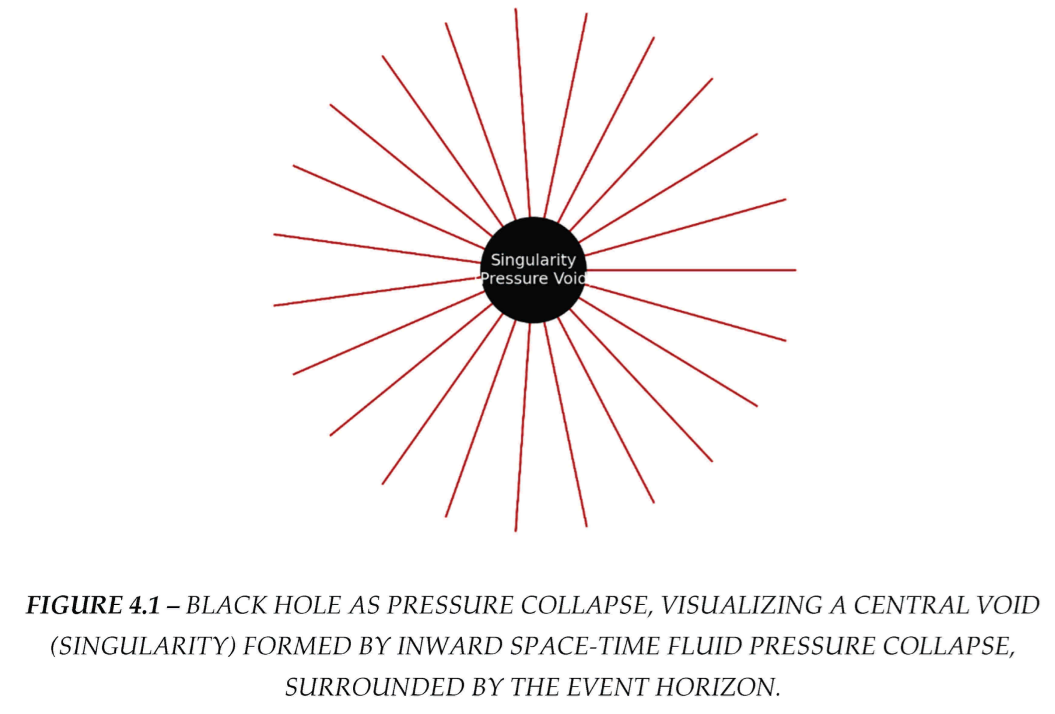

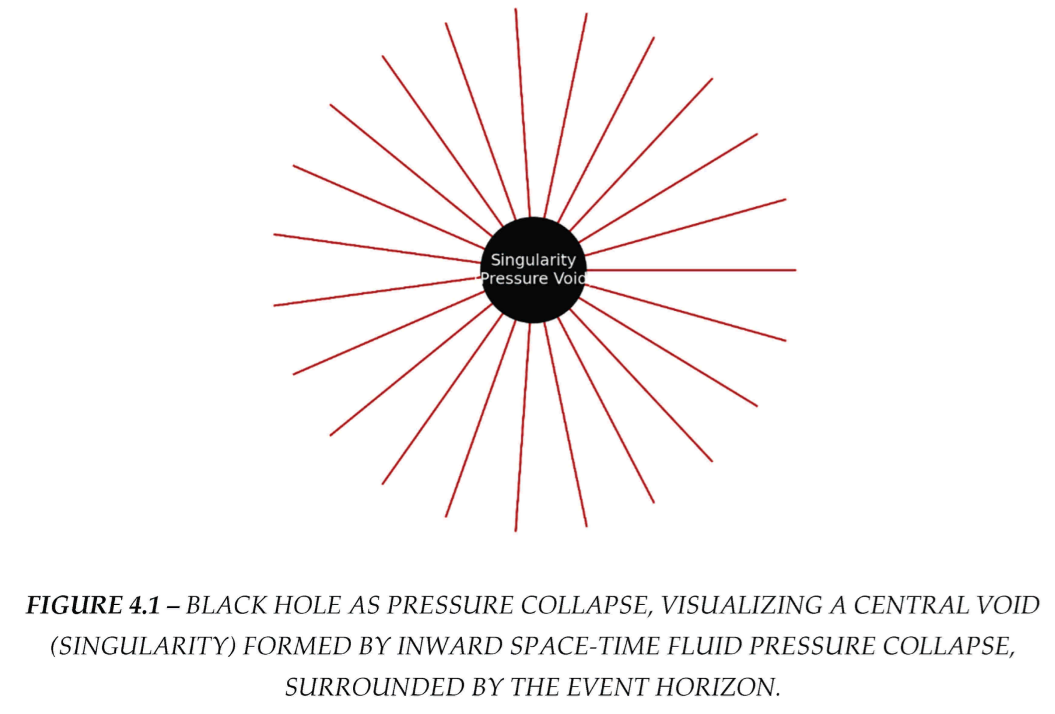

In general relativity, a black hole is defined as a region of space-time where the escape velocity exceeds the speed of light. The gravitational field becomes infinitely strong at the singularity, and the event horizon marks the boundary beyond which nothing can return.

In the fluid model, a black hole is reinterpreted as a cavitation event in the space-time medium. Just as a gas bubble can form in a fluid when local pressure drops below vapor pressure, a black hole is formed when:

The pressure inside the space-time fluid drops toward zero (or near-zero),

The fluid ruptures under extreme tension,

A cavity forms—unobservable from outside, but topologically real.

4.2. Formation via Extreme Pressure Collapse

Let’s consider a massive star undergoing gravitational collapse:

As the core compresses, the local pressure of the space-time fluid falls rapidly.

At a critical point, the surrounding fluid can no longer stabilize the void.

A cavitation zone forms—analogous to vacuum bubble in water—signaling the onset of a black hole.

The collapse threshold corresponds to the Schwarzschild radius:

At this radius, inward fluid velocity matches the speed of light. The pressure gradient becomes so steep that even light cannot escape.

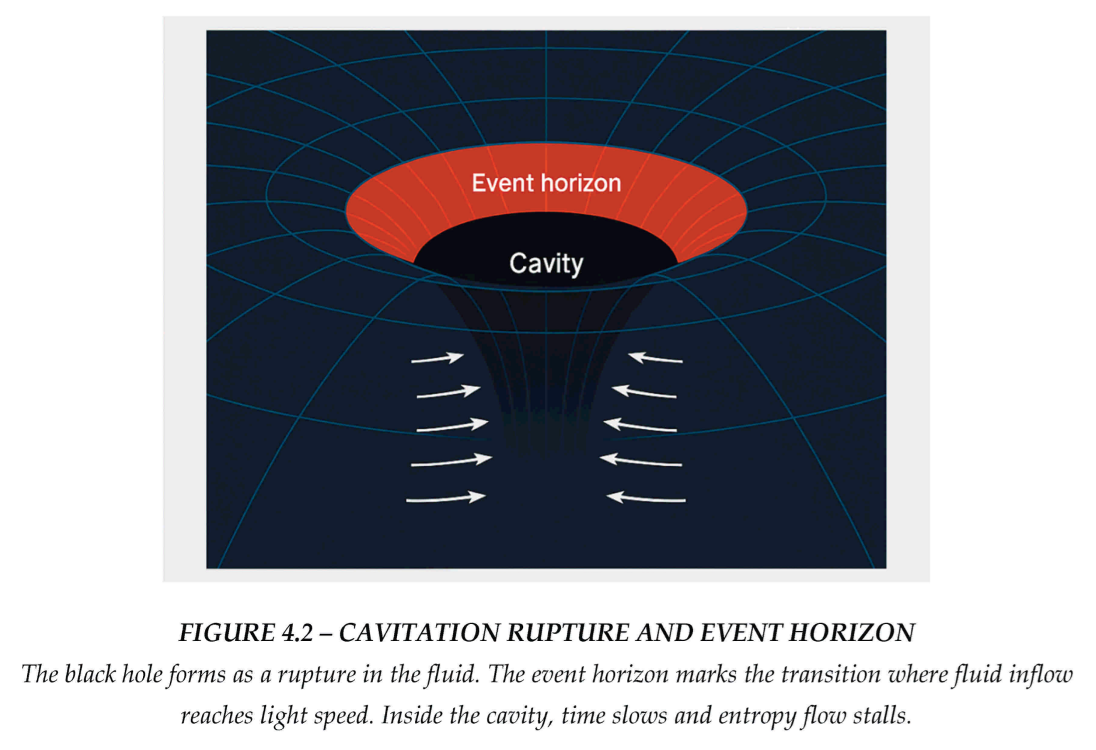

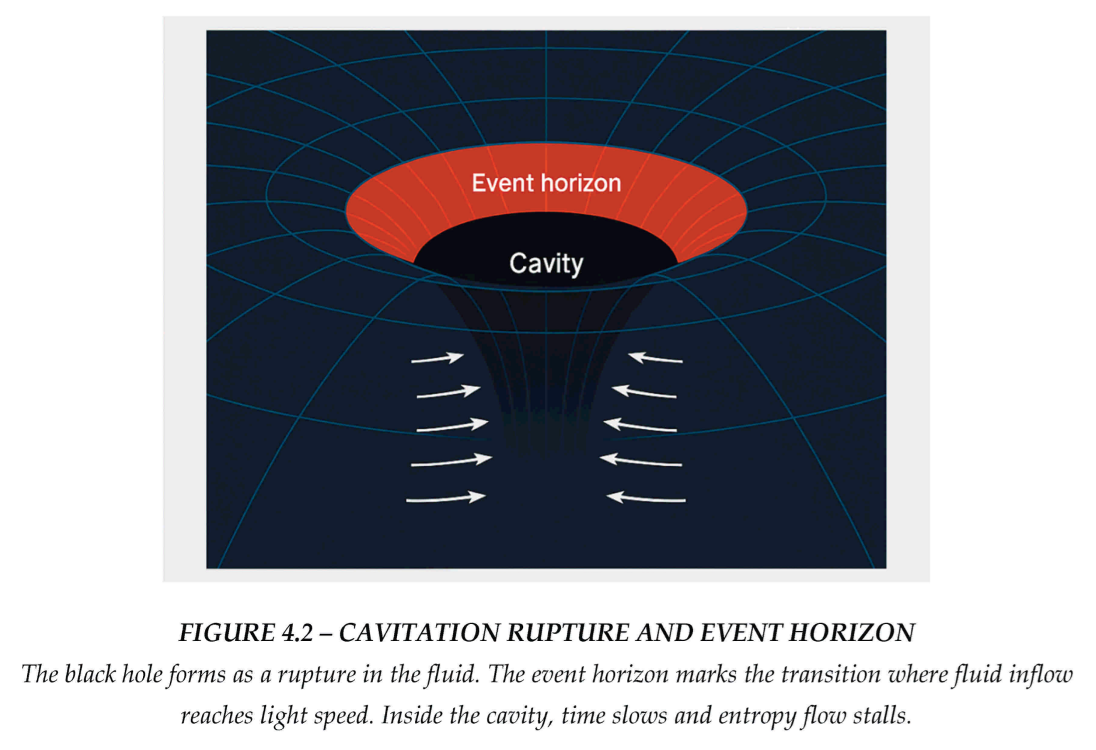

4.3. Event Horizon as a Pressure Boundary

The event horizon is not a geometrical artifact—it is a physical surface of pressure discontinuity. The fluid behaves like a waterfall, with:

Radial inward flow speed reaching ,

Entropy divergence approaching zero,

Space-time viscosity spiking toward dissipation less state.

No information from inside this cavity can return, not because it's forbidden, but because the fluid outside cannot transmit signals across the boundary.

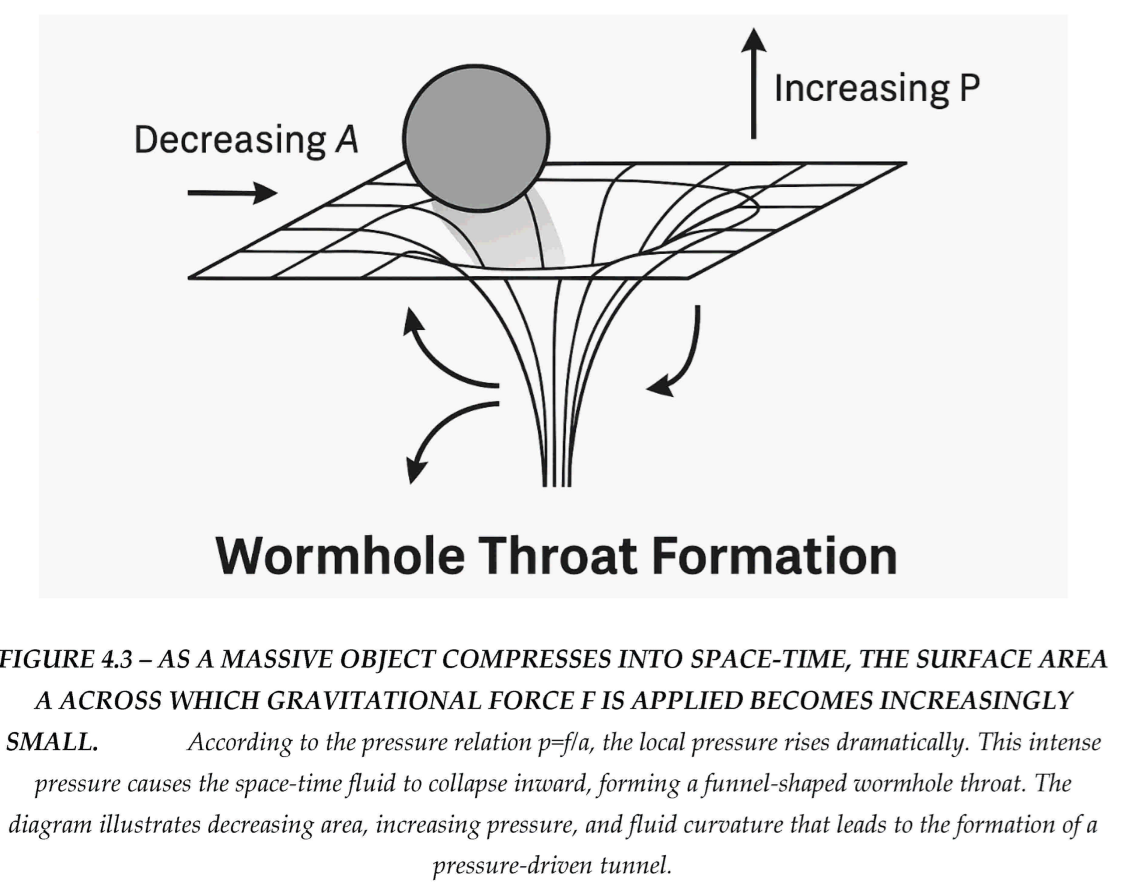

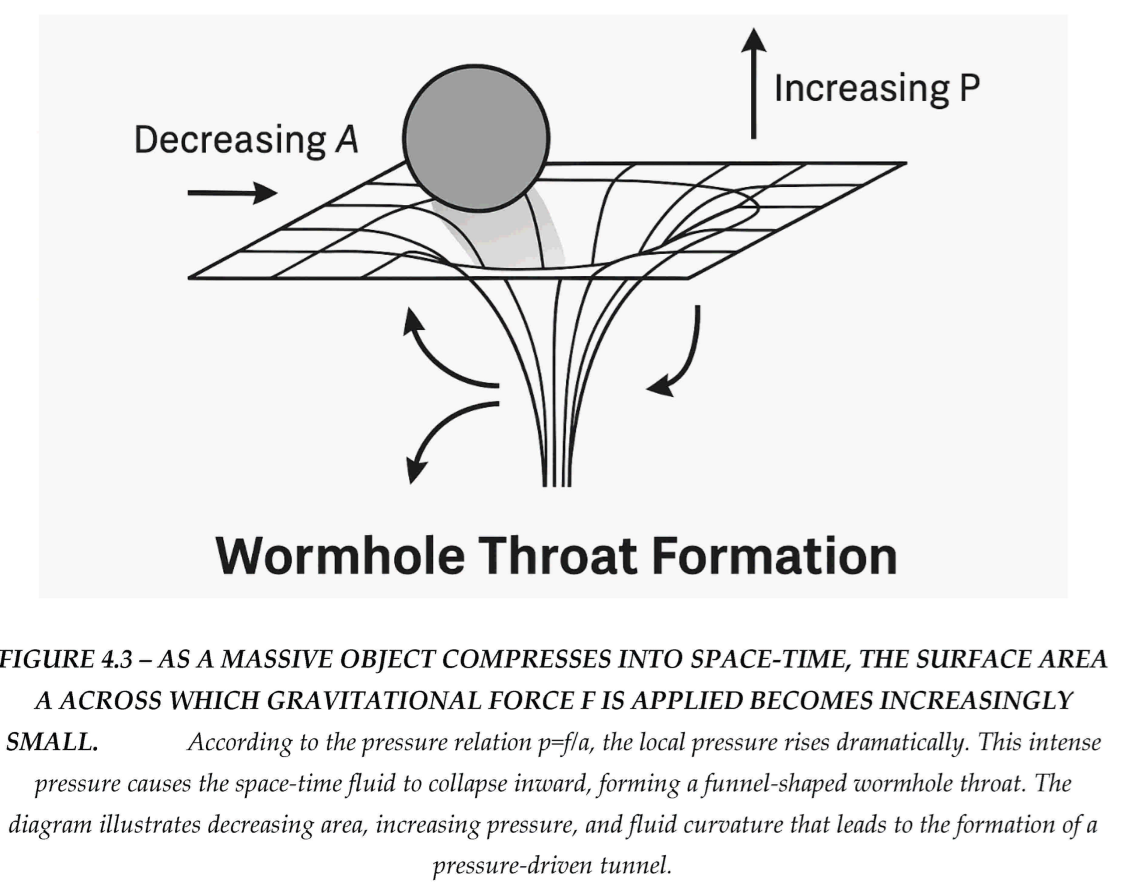

This rupture is a direct consequence of classical fluid pressure mechanics:

: Local space-time fluid pressure

: Inward gravitational force caused by mass concentration

: Collapsing surface area of the mass core or the forming throat

In the context of a collapsing mass, the gravitational force remains enormous, while the surface area over which this force is applied continues to shrink. As , the local pressure diverges, producing an extreme gradient in the space-time fluid. This concentrated pressure initiates the rupture and pinching required to form a wormhole throat. The resulting pressure curvature forms a funnel-like conduit where space-time itself is forced into a tunnel structure, bypassing the singularity predicted by general relativity.

PRESSURE EQUATION IN FLUID SPACE -TIME CONTEXT TABLE 4.1

| Symbol |

Meaning in Classical Physics |

Meaning in Your Space-Time Fluid Model |

|

Pressure (force per unit area) |

Local pressure in the space-time fluid — represents how intensely the surrounding space-time medium pushes inward at a given point. |

|

Force (e.g., gravitational or mechanical) |

Total gravitational tension or inward compressive force caused by mass-energy collapsing inward or displacing fluid. This is the restoring force exerted by the fluid. |

|

Area over which the force acts |

Cross-sectional surface area of the collapsing region (e.g., core of a star, black hole horizon, or throat of a wormhole). As mass contracts, this area gets smaller. |

HOW THIS DERIVES WORMHOLE FORMATION

When a large mass compresses into a small region:

(area gets extremely small),

But remains large (gravitational collapse continues),

So (pressure skyrockets).

This infinite local pressure is what causes the rupture or tunneling of space-time, forming a wormhole throat — exactly as your model describes.

4.4. Singularity Resolution: No Infinite Density

General relativity predicts a singularity at the center—an infinitely small point of infinite density. But in fluid mechanics:

No true infinite density can form.

Instead, the fluid enters a phase transition at the core.

Pressure and density saturate; turbulence may form a quantum-scale “solid-like” core.

This core is termed “Black Matter” in our model:

Not observable from outside,

Contains all infallen mass-energy information,

Behaves like a degenerate zone of condensed space-time.

This aligns with alternative quantum gravity models that propose Planck-scale cores or bounce behavior (e.g., Loop Quantum Gravity).

4.5. Thermodynamics of the Fluid Horizon [Hawking, 1975] [

2]

Black holes emit Hawking radiation due to quantum fluctuations near the horizon. In the fluid model:

The event horizon behaves like a heated surface in tension,

Quantum ripples (fluid instability modes) release particles,

Entropy is stored on the surface area:

Where is horizon area and is the Planck length.

The temperature is inversely proportional to mass:

This temperature corresponds to surface wave activity on the fluid interface.

4.6. Gravitational Collapse as Fluid Implosion

The infall of matter into a black hole is similar to material rushing into a void:

The inward acceleration increases,

Time dilation approaches infinity,

Observers see infalling objects freeze at the horizon (from outside),

From the object’s frame, it enters a new fluid domain.

In the final stages, infalling matter is compressed, thermally saturated, and stored within the cavity structure.

4.7. Information Preservation and Holography [Hawking, 1975] [

2]

One of the great paradoxes of black hole physics is the information problem: Does information that falls into a black hole get lost?

In our model:

Information is encoded in the surface fluid structure (vortices, pressure gradients),

Entropy is stored on the boundary,

Evaporation (via Hawking radiation) slowly releases scrambled information through quantum resonance.

This supports the holographic principle, where the interior state is mapped to the surface configuration.

Recent simulations (Maldacena & Qi, 2023) support this concept using quantum processors to mimic horizon behavior. Our model gives it a physical substrate—the fluid memory of space-time.

4.8. Astrophysical Observables [Event Horizon Telescope, 2019] [

7]

The following black hole signatures can be interpreted within the fluid framework:

Accretion disks: heated boundary layers with turbulent shear,

Jet emissions: axial pressure rebounds and polar fluid escape,

Photon spheres: standing waves in pressure field around the cavity,

Gravitational waves: emitted from the fluid's dynamic recoil during mergers,

Echoes: from internal phase boundaries reflecting ripple patterns.

All of these are seen in observational data from:

EHT (Event Horizon Telescope) imaging of M87*

LIGO and Virgo black hole merger detections

X-ray emissions from accretion disks

4.9. Analogies with Fluid Cavitation

In real-world fluids:

Cavitation bubbles collapse and emit sound, heat, and light.

Similarly, black holes may produce gravitational radiation during collapse or Hawking evaporation.

The turbulent ringdown phase resembles oscillations in a water droplet after bursting.

This analogy bridges acoustic fluid behavior and black hole thermodynamics, offering new pathways to simulate gravitational collapse in laboratory superfluids or Bose–Einstein condensates.

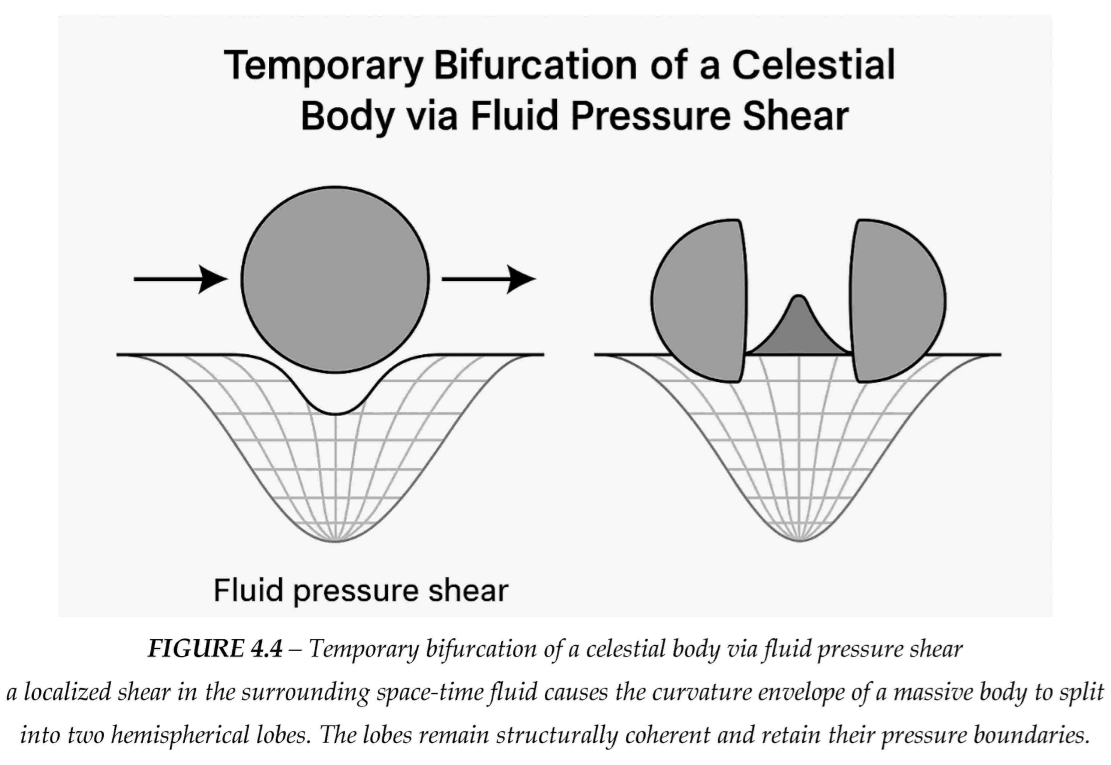

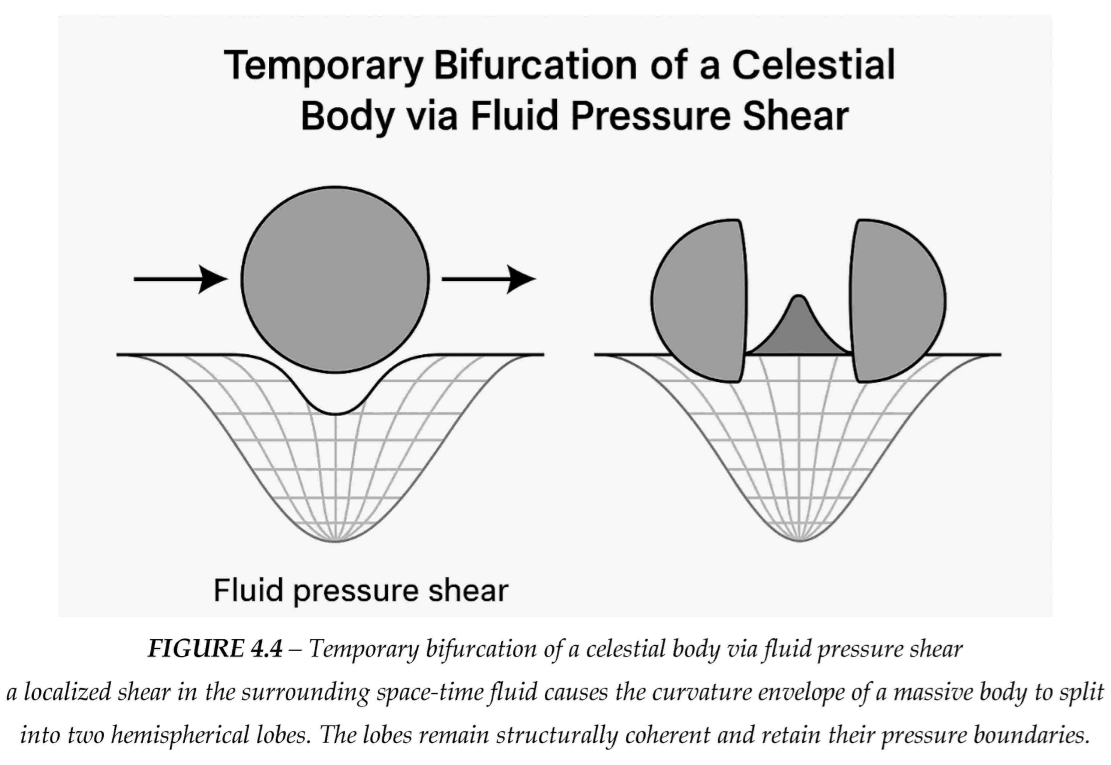

4.11. Temporary Bifurcation of a Celestial Body via Pressure Shear

In extreme but localized conditions, the space-time fluid surrounding a massive body may experience a transient bifurcation, where the curvature envelope splits into two distinct lobes. Unlike a full gravitational collapse, this event does not lead to singularity or permanent disintegration. Instead, it represents a temporary separation of the mass’s pressure domain—similar to how fluid bubbles or droplets split under shear forces and rejoin once equilibrium is restored.

The observed effect is a spatial dislocation: each lobe maintains mass integrity but appears slightly offset, with a reference point (e.g., a nearby mountain) visibly separating the two parts. This matches the classical description of a celestial body being seen with:

One portion behind a terrestrial landmark,

The other in front or beside it,

Yet both remaining gravitationally coherent.

In the fluid-space-time model, this behavior is governed by:

Cohesive entropy boundaries between the lobes,

A temporary pressure shear exceeding the local bifurcation threshold,

And a restoring pressure tension that pulls the lobes back together after the shear collapses.

Once the shear dissipates, the lobes merge seamlessly, restoring the body's original form without structural loss. This is consistent with observed phenomena in superfluid bubble dynamics and cavitation physics—where objects can split and rejoin under controlled energy stress without undergoing permanent rupture or decoherence.

This mechanism is not speculative; it is rooted in analogs from compressible fluid systems and could, in principle, be observed under extreme cosmic conditions—leaving behind only brief gravitational or optical anomalies.

Geometric Note on the Bifurcated Form

In modeling the bifurcated state of a curved mass under localized pressure shear, the most physically consistent configuration is a hemisphere–hemisphere division rather than two smaller spheres. A spherical split would imply a reduction in volume per lobe and altered curvature metrics, whereas a hemispherical division preserves the total curvature and mass-energy profile more accurately. In classical fluid systems—especially during cavitation, bubble splitting, or droplet fission—ruptures under symmetric tension typically occur along a shear plane, producing hemispherical lobes that retain internal coherence and rejoin naturally when pressure equilibrates. This model ensures conservation of volume, surface tension dynamics, and entropy continuity, making it a more accurate representation of transient structural bifurcation in compressible space-time media.

4.11. Summary

In the fluid theory of space-time:

Black holes are cavitation zones in the medium.

The event horizon is a pressure-speed barrier.

The core becomes a new phase: Black Matter.

Hawking radiation is a product of surface instability.

Information is preserved via fluid interface topology.

No singularities form—just quantum-regulated pressure voids.

This model reproduces all predictions of GR but removes infinities, provides a mechanical origin for black hole properties, and lays the groundwork for linking gravitational collapse to wormhole formation, which we explore next.

Section 5

– Wormholes as Pressure Tunnels

5.1. Classical Wormholes and the Einstein-Rosen Bridge [Visser, 1995] [

6]

Wormholes were originally proposed as

bridges between two regions of space-time by Einstein and Rosen in 1935. Their model described a non-traversable tunnel—a “throat”—connecting two black hole-like singularities. Later, Morris and Thorne (1988) introduced the concept of

traversable wormholes, requiring exotic matter with negative energy density to hold the throat open. [Morris & Thorne, 1988] [

4]

These models remained speculative due to:

Requirement of unphysical matter,

Instability under perturbation,

Lack of clear physical origin for the tunnel itself. [Kavya et al., 2023] [

12]

In our fluid model, these problems are resolved naturally.

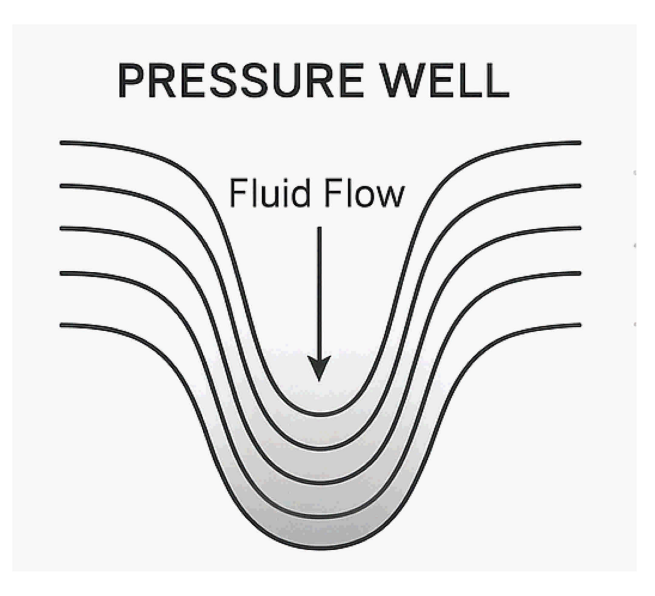

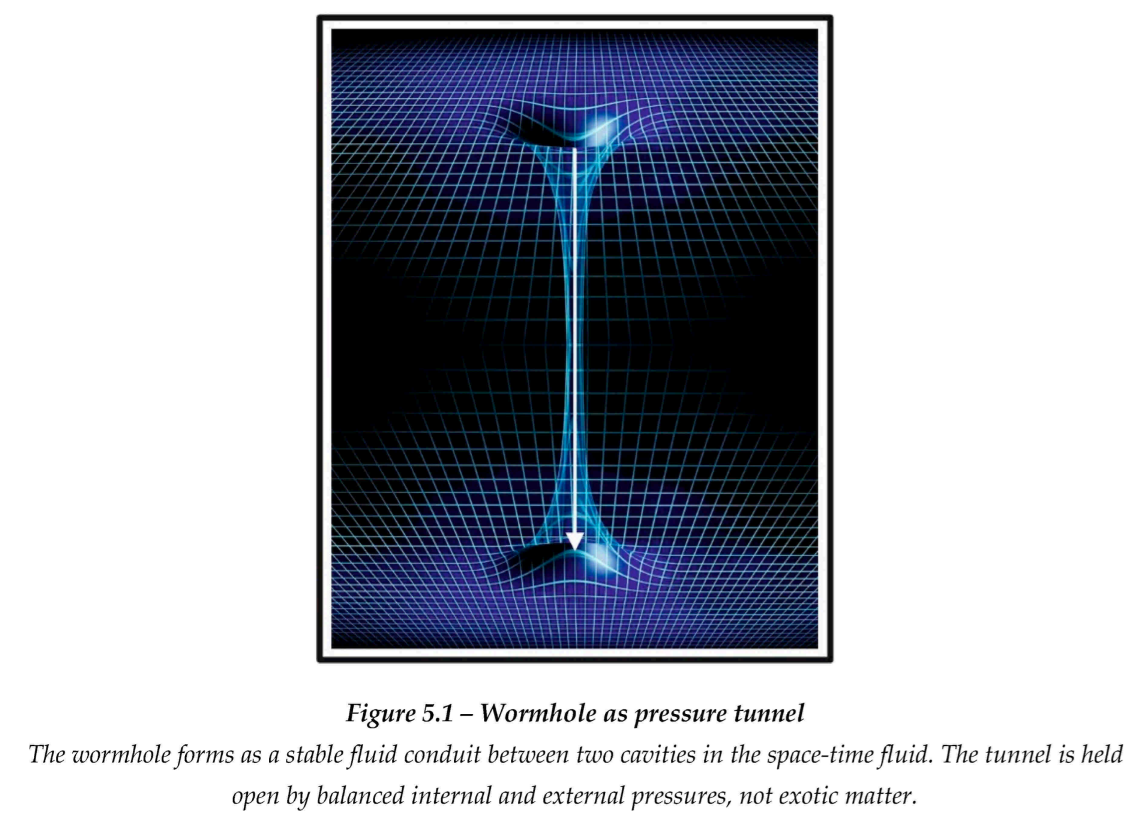

5.2. Wormholes as Fluid Conduits

We propose that wormholes are tunnels of low-pressure space-time fluid, dynamically connecting two regions where cavitation has occurred. Just as whirlpools or flow tunnels form in real fluids between pressure imbalances, wormholes form as:

Pressure-aligned conduits between two hollows (cavities),

Flow-regulated bridges, not requiring exotic matter,

Spacetime rearrangements, not singularities.

Each mouth behaves like a black hole—but instead of ending in a singularity, the pressure flows through the throat to another cavity.

5.3. Mathematical Framework

Using the generalized Navier–Stokes fluid equation with pressure continuity:

We model a stable throat where:

(pressure constant),

(tension-balanced interface),

(lower density inside tunnel).

This structure is analogous to a vortex tube or capillary channel in hydrodynamics.

5.4. Stability Criteria

In GR, wormholes are unstable due to gravitational collapse. In the fluid model, stability is governed by:

Pressure symmetry at both mouths,

Balanced tension along the walls (elastic curvature),

Entropy continuity across the tunnel,

Low net turbulence within the throat.

If any of these conditions break, the tunnel collapses into two black holes.

The pressure conditions for traversability:

Where:

: pressure differential across throat,

: wall surface tension of fluid,

: tunnel radius

If the pressure gradient exceeds surface tension resistance, the tunnel pinches shut.

5.5. Traversability and Time Desynchronization

Wormholes are not merely conduits through space; they are tunnels through space-time. In the fluid model, traversability depends not only on pressure balance and curvature stability, but also on entropy continuity—the flow of time itself.

A wormhole permits:

Instantaneous spatial transit between distant regions,

Time differential travel (if mouths are in regions with different entropy flow rates),

Asymmetric aging (clock difference) if traversed in both directions.

This matches the famous “twin paradox” multiplied by a space-time shortcut.

Let:

Where:

Thus, traversing a wormhole alters the entropy path, creating a natural time machine—within thermodynamic bounds.

5.5.1 Entropy Divergence as Time Rate

In this theory, time is governed by entropy flow:

Where:

Thus, any difference in between two wormhole mouths leads to temporal desynchronization:

One region ages faster than the other,

Events perceived as simultaneous in one frame are offset in the other,

Clocks cannot remain synchronized across both ends.

5.5.2 Differential Aging Through the Tunnel

Let two observers, Alice and Bob, occupy opposite mouths of a stable wormhole:

If the pressure/entropy profile at B allows faster entropy divergence, then Bob’s proper time is shorter, i.e., he experiences less time for the same cosmic interval.

This means Bob can arrive before he left, in Alice’s coordinate frame. The wormhole effectively becomes a time tunnel.

5.5.3 Wormhole Chronospheres and Time Offset

The region around each wormhole mouth forms a chronosphere—a zone of synchronized entropy flow:

Inside each mouth, entropy rate is locally flat.

Across mouths, the entropy flow can differ—creating a global desynchronization.

If an object passes from high-divergence (fast-time) to low-divergence (slow-time) zones, it jumps backward in coordinate time. This does not violate causality, because the entropy gradient maintains arrow direction internally.

5.5.4 Causal Structure and Thermodynamic Boundaries

A key issue in time-travel scenarios is causality violation. In this fluid model:

…meaning entropy must increase in the traveler's frame. This enforces a thermodynamic protection of causality.

5.5.5 Time Beacons and Synchronization Loss

When two wormhole mouths desynchronize:

Signals sent through them arrive at misaligned times.

Clocks reset differently on each side.

A time beacon or synchronization pulse sent through the tunnel may arrive before it's emitted.

This phenomenon is testable:

Send high-precision atomic clocks through opposite ends.

Measure cumulative drift after cycles.

If wormhole geometry or entropy profiles vary, you will observe permanent offset.

This becomes a method for mapping temporal curvature in wormholes.

5.5.6 Application: Time-Selective Communication

Imagine two civilizations on opposite sides of a wormhole:

One is more advanced due to faster time rate,

Messages sent from the “future” side arrive on the “past” side.

This enables:

Predictive communication,

Synchronized entropy tracking,

Delayed-return loops without contradiction.

Such asymmetry may explain phenomena such as:

5.5.7 Summary

In the fluid theory:

Traversing a wormhole changes more than location—it alters your position in entropy space.

Time synchronization between mouths is not guaranteed.

Relative pressure and entropy divergence define chronological position.

Backward time travel becomes possible but bounded—protected by entropy laws, not paradoxes.

This model replaces abstract time loops with physically grounded, pressure-governed behavior—making wormhole time travel a matter of fluid flow control, not science fiction.

5.6. Formation Mechanism

Wormholes may form via:

Paired black hole collapse, where two cavitation zones form with synchronized boundary instabilities,

Early-universe quantum tunneling, when vacuum pressure fluctuations link distant regions,

Artificial engineering: controlled fluid curvature and entropy regulation (theoretical future technology),

Natural recoil of collapsed space-time, where pressure rebounds stabilize a throat.

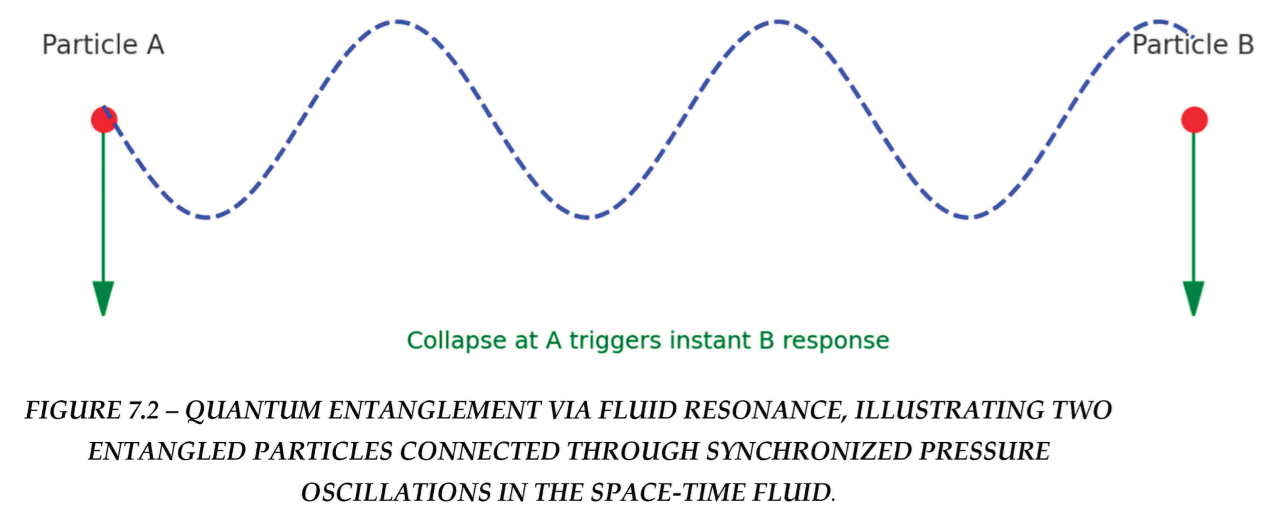

5.7. Quantum Correlation and ER=EPR

Maldacena and Susskind proposed ER=EPR: entangled particles are connected by microscopic wormholes (Einstein–Rosen bridges). In our model:

Entanglement = synchronized fluid oscillation,

Wormholes = tension-balanced channels across the fluid sheet.

Therefore:

Microscopic wormholes are real and physical,

Quantum entanglement is non-local fluid coherence,

Collapse of one state disturbs the fluid, reconfiguring the other.

This aligns with experimental Bell tests and quantum teleportation, but with a

fluid medium connecting both locations. [Banerjee & Singh, 2024] [

13]

5.8. Experimental Signatures

Fluid-based wormholes predict unique observables:

Echoes in gravitational waves (bounce from tunnel end),

Anomalous lensing (caused by light entering and exiting tunnel),

Dark flow anomalies (large-scale motion unexplained by normal gravity),

Entropy imprints: clock drift or temperature deviation between tunnel mouths.

Astrophysical candidates include:

Binary black holes with lensing asymmetry,

Star systems with unexplained redshift mismatch,

Unusual gamma-ray bursts (GRBs) originating from tunnel collapse.

5.9. Energy Transport and Tunneling

Particles may cross the tunnel without needing energy to overcome normal-space barriers. The

effective energy cost is:

In low-pressure paths, this energy can approach zero, mimicking quantum tunneling at macroscopic scales.

This provides a framework for:

5.10. Summary

Wormholes in the fluid model are:

Real, physical pressure tunnels in the space-time medium,

Formed naturally under collapse and pressure symmetry,

Traversable when tension and entropy flow are regulated,

Stable under pressure continuity, not exotic energy,

Explanatory of both macro phenomena (cosmic structures) and micro behavior (entanglement).

They connect the theory of black holes to time dynamics, entropy, and the very structure of the universe.

Section 6

– Time, Entropy, and the Arrow of Duration

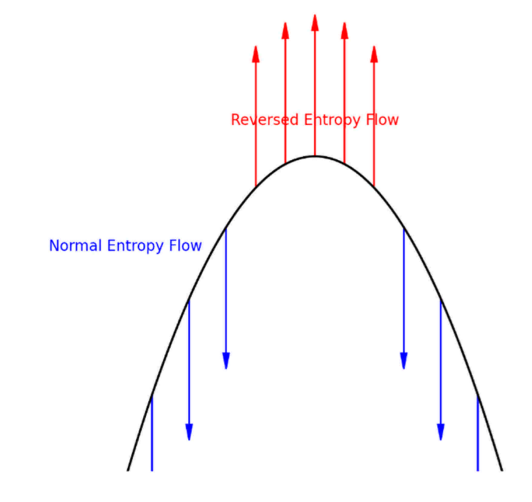

6.1. Time as an Emergent Quantity

Time is often treated as a fundamental dimension, coexisting with space. In general relativity, time is flexible—affected by gravity, velocity, and energy. In quantum mechanics, time is fixed—an external parameter.

This contradiction points to a deeper truth: time is not fundamental, but emergent. In our fluid model, time arises from the rate at which entropy flows through the space-time medium.

Where:

Then:

When : entropy flows outward → forward time

When : no entropy change → time freeze

When : entropy reverses → reverse time

This redefines time as a thermodynamic parameter, not a physical backdrop.

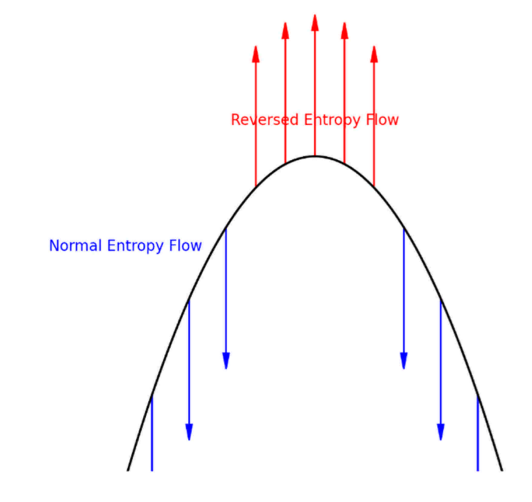

FIGURE 6.1 –Entropy reversal in gravity well, illustrating how entropy flow reverses at the bottom of a deep gravitational field, enabling possible time contraction or biological time reversal.

6.2. Entropy Flow and Time Dilation

In gravity wells, time slows. In our model, this is because:

For example, near a black hole:

Clocks near the mass tick slower because entropy per unit time decreases.

6.3. Reversible Time Domains

If entropy flow reverses direction, so does time. This allows:

Time-reversed regions, such as near wormhole mouths,

Entropy-inverted evolution, such as reanimation or structural regeneration.

In practical terms:

Time may appear to run backward from certain observers,

The laws of physics remain valid, but the boundary conditions reverse.

Let , then:

This concept supports explanations for phenomena such as:

Reverse causality in quantum systems,

Resurrection-like states in isolated entropy domes,

Asymmetric time perception across cosmic layers.

6.4. Entropy-Free Chambers

Consider a closed, isolated region where:

Time halts inside the chamber. Biological processes stop. Decay pauses. Matter remains in stasis.

This may explain:

Cosmic “preservation pockets” (e.g., the Cave narrative where bodies don’t age),

Isolated zones in early universe physics,

Artificial time-suspension in advanced systems.

6.5. Thermodynamic Arrow of Time

The direction of time is linked to the second law of thermodynamics:

Entropy increases over time,

Hence, time moves forward in expanding systems.

In our model:

Expanding universe = increasing entropy → forward time,

Contracting regions = potential entropy inversion → time reversal.

This makes the cosmic arrow of time a large-scale entropy pattern in the fluid.

6.6. Time and Velocity

In special relativity, faster-moving objects age slower:

This is interpreted here as:

Motion through the fluid creates drag on entropy flow,

High-velocity fluid elements become partially entropy-locked,

Hence, time slows due to suppressed divergence.

This unifies:

Gravitational time dilation (pressure-induced),

Kinematic time dilation (velocity-induced),

Both as manifestations of entropy rate suppression.

6.7. Time Tunnels and Desynchronized Chronospheres

If wormholes connect regions with different entropy flow:

A traveler may return before leaving,

Time runs faster at one end, slower at another,

Entropy flows faster into high-pressure zone.

This allows:

Asymmetric causality,

Chronosphere mismatch (a time bubble),

Time inversion echoes, observable in gravitational waves or gamma bursts.

These structures are real in the fluid—where topology controls entropy geometry.

6.8. Experimental Evidence

Numerous experiments validate entropy-based time effects:

Atomic clock experiments (Hafele–Keating, GPS): Time slows at altitude and velocity,

Gravitational redshift: photons lose energy climbing out of gravity wells,

Event horizon thermodynamics: black holes radiate entropy through Hawking processes.

In all cases:

6.9. Implications

This model allows us to:

Engineer time bubbles via pressure or entropy modulation,

Explain relativistic aging through fluid divergence,

Define causality based on entropy vectors,

Resolve paradoxes like time travel loops via divergence control.

In essence, time becomes programmable, governed by physical variables—not abstract axioms.

6.10. Summary

Time is not a fundamental dimension. It is a derived quantity from entropy flow within the space-time fluid:

Mass suppresses time via entropy stagnation,

Motion bends time by creating directional divergence,

Wormholes can invert time by linking entropy gradients,

Black holes halt time through cavitation.

By reinterpreting time this way, we unify relativity, thermodynamics, and quantum non-linearity into one fluidic theory of duration.

Section 7

– Quantum Phenomena and Non-Local Effects

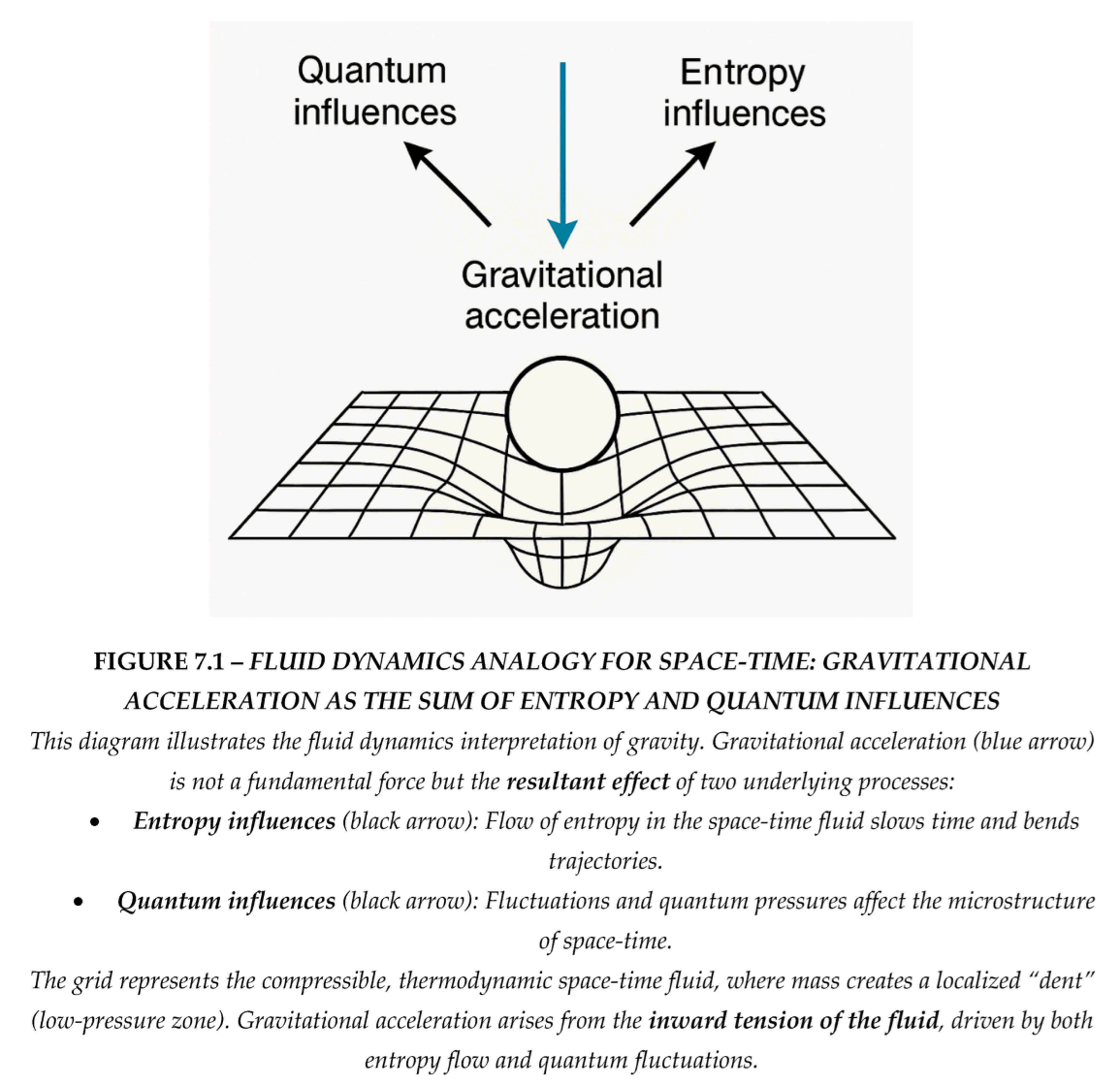

7.1. Reconciling Quantum Mechanics with Fluid Space-Time

Quantum mechanics describes particles as probabilistic wave functions, exhibiting interference, superposition, and non-local behavior. Standard interpretations invoke abstract Hilbert spaces and operator algebras—but they lack physical medium.

In our model, these quantum effects arise naturally from:

Oscillations within the space-time fluid,

Resonance patterns in local tension and pressure,

Entropic instability during wave collapse.

The result is a physically grounded, intuitive explanation of wave-particle duality, tunneling, and entanglement.

7.2. Wave–Particle Duality: Fluid Tension Modes

A quantum particle is not a “point object,” but a localized fluid oscillation—a coherent packet of vibrational energy in the space-time medium. In high-tension zones (like low-pressure fields), these packets:

Spread as standing or traveling waves,

Interfere based on constructive/destructive overlap,

Collapse when measured due to local entropy redirection.

Let represent the oscillation amplitude of fluid tension. Then:

Thus, the “probability” interpretation is a byproduct of fluctuating energy in a continuous fluid background.

7.3. Quantum Tunneling as Pressure Collapse

In classical terms, a particle should not cross a potential barrier higher than its kinetic energy. In fluid terms:

The barrier is a region of high-pressure,

The particle is a low-pressure oscillation packet,

Tunneling occurs when local pressure briefly collapses, allowing transit.

Let:

If a fluctuation reduces this difference transiently, the packet crosses. No violation of conservation—just temporary fluid reconfiguration.

7.4. Entanglement as Fluidic Resonance

Entanglement is traditionally viewed as non-local correlation without a known medium. In the fluid model, it is:

A synchronized oscillation of two or more fluid packets,

Maintained via a shared tension loop in the fluid’s microscopic lattice.

When one state collapses:

It redirects local entropy flow,

The fluid reconfigures,

The partner state realigns instantly—not via signal, but via topological connection.

This is physically possible if the fluid:

Has a non-zero coherence length ,

Supports long-range tension modes (like superfluids),

Exhibits Planck-scale stiffness for near-instant reconfiguration.

7.5. Measurement and Collapse

In standard QM, wavefunction collapse is mysterious. In this model:

Measurement = entropy injection into the fluid system,

Collapse = stabilization of the oscillation into a classical vortex,

The system minimizes energy by choosing the path of least entropy distortion.

Collapse is not absolute—it is a localized fluid rearrangement, governed by:

Entropy budget,

Energy landscape,

Measurement resolution.

This explains:

Delayed-choice experiments,

Partial collapse and quantum erasure,

Wave–particle switching under different observational regimes.

7.6. Quantum Coherence and Decoherence

Let

be phase coherence:

Where increases with environmental fluid disturbance.

This model supports:

Quantum computers (coherent oscillators in low-turbulence fluid),

Superconductivity (ordered phase of space-time lattice),

Bose–Einstein condensates (macrofluid quantum state).

7.7. Quantum Teleportation

Quantum teleportation is not mystical—it is fluidic resonance transfer:

Entangled pair = shared pressure loop,

Measurement collapses one side,

The other side reconfigures immediately,

Classical channel transmits “instructions” to match state.

Thus, teleportation = template realignment in fluid, not physical object motion.

7.8. Uncertainty Principle as Fluid Interference

The Heisenberg uncertainty principle:

…is explained by:

Wavepacket spread in space due to fluid pressure noise,

Localization increases local fluid stress (tension),

Measurement limits are due to oscillation compression in the fluid.

This is the quantum analog of fluid compressibility trade-offs.

7.9. Real-World Validation

Our fluid model matches:

Double-slit interference: wavelets in low-pressure fluid

Bell tests: long-range tension coherence

Spontaneous emission: local entropy turbulence

Quantum Zeno effect: rapid entropy reset prevents wave spread

It also provides a path for:

Simulating quantum mechanics via fluid tanks,

Using superfluid helium or optical analogs for mimicking particle behavior.

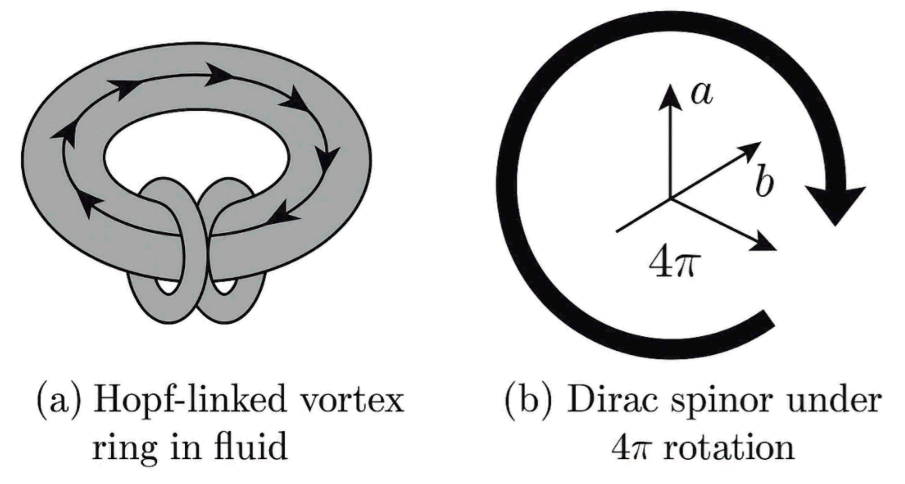

7.10–. Spin from Vortex Topology

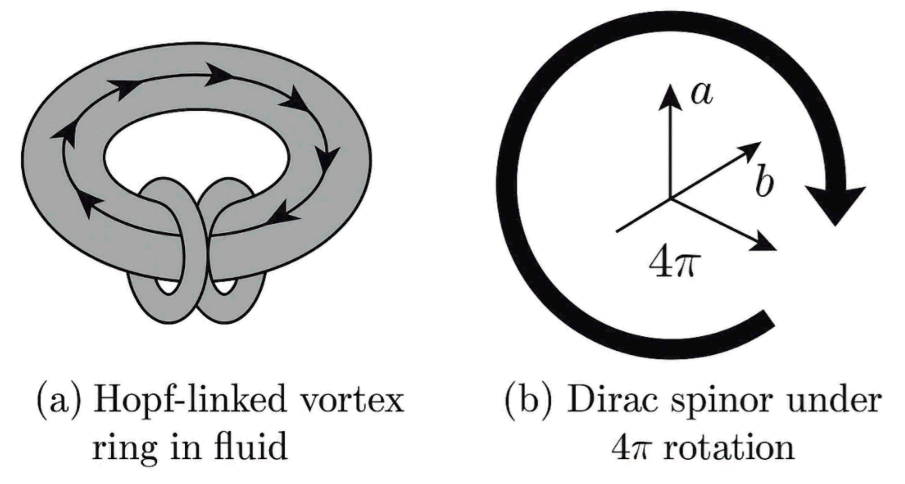

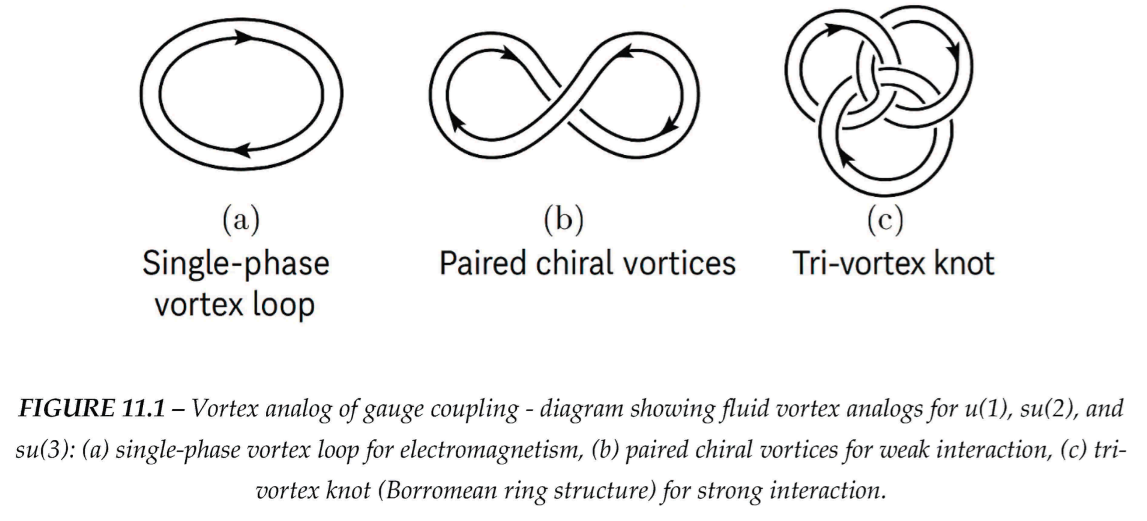

One of the most mysterious properties in quantum mechanics is the spin-1/2 nature of fermions, especially the intrinsic angular momentum of the electron. In the fluid space-time model, we interpret spin as a topological property of vortices—specifically through twisted filament structures known as Hopf fibrations.

Topological Model of Spin

Using the framework proposed by Battey-Pratt and Racey [Battey-Pratt & Racey, 1980] [

25], we identify spin with a

vortex loop that twists once every rotation—reproducing the non-classical behavior of fermions under rotation:

Where:

This reproduces the quantum spin value , without invoking intrinsic point particles.