Submitted:

26 January 2025

Posted:

27 January 2025

You are already at the latest version

Abstract

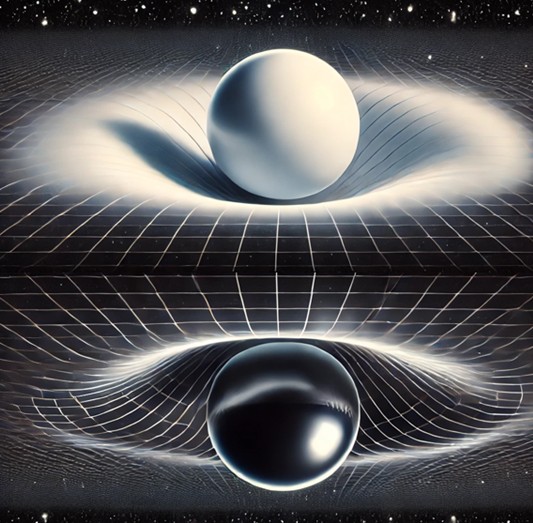

We propose a Space-Time Membrane (STM) model that treats four-dimensional spacetime as an elastic membrane paired with a hypothetical “mirror” universe on its opposite side. Energy external to the membrane deforms it, producing gravitational curvature akin to General Relativity (GR), while energy distributed uniformly within the membrane remains curvature-neutral. Localised particle excitations manifest as oscillatory modes on one face, partnered with mirror antiparticles on the other. Although the STM model does not claim to replace established quantum field theory (QFT), it offers a complementary route to reconciling gravity and quantum phenomena: deterministic wave interactions can reproduce quantum-like interference and “entanglement analogues,” potentially seeded by small, persistent waves at sub-Planck scales. A modified elastic wave equation—incorporating tension, bending stiffness, and spatially varying membrane properties—captures weak-field gravitational effects reminiscent of GR. Simultaneously, it supports stable standing waves analogous to quantum interference. Within this picture, photons emerge as “wave-plus-anti-wave” oscillations that remain massless, exhibit correct polarisation states, and respect U(1) gauge symmetry and Lorentz invariance. By tuning intrinsic coupling constants, time-averaged stiffness shifts can align with observed vacuum energy, offering insight into the cosmological constant. Despite these promising features, the STM model remains speculative. Further theoretical and observational work is needed to clarify its relationship to standard physics and evaluate its quantitative predictions. As a geometric, deterministic perspective, it complements but does not supersede GR or QFT, suggesting pathways for future theoretical investigations and possible analogue experiments.

Keywords:

1. Introduction

Key Aspects of the STM Model

- 1.

-

Modified Elastic Wave EquationWe derive a wave equation for the membrane that combines tension, bending stiffness, and local variations in elastic modulus . These modulations depend on oscillation energy densities and an intrinsic coupling constant. While still speculative, the resultant equation captures elements that resemble gravitational curvature on large scales and quantum-type interference on small scales.

- 2.

-

Photons as Wave–Anti-Wave OscillationsInterpreting photons as global wave-plus-anti-wave excitations ensures they remain massless, respect U(1) gauge invariance, exhibit correct polarisation states, and preserve Lorentz invariance (see Appendices A–E). From the viewpoint of the STM model, this provides a geometric explanation for classical interference and entanglement analogues, albeit in a deterministic setting.

- 3.

-

Avoidance of SingularitiesIn strong curvature regimes (such as black hole interiors), the STM model posits that grows with energy density, increasing local membrane stiffness. This heightened stiffness can, in principle, tame unbounded curvature predicted by classical GR, potentially removing central singularities and enabling finite-energy wave patterns to form (Appendices F–H).

- 4.

-

Vacuum Energy and the Cosmological ConstantBy adjusting an intrinsic coupling constant , time-averaged changes in membrane stiffness may align with observed vacuum energy, offering a route to interpret the cosmological constant (Appendix K). Further refinements—such as a second coupling constant —could allow spatial variations in vacuum energy, with possible ramifications for dark matter distributions or the Hubble tension.

- 5.

-

Consistency with Existing FrameworksCrucially, this approach is not presented as a full unification or replacement for QFT; it remains a continuum-based analogy that recasts aspects of both gravity and quantum phenomena within an elastic model. Where it reproduces known results, it does so in ways reminiscent of GR and QFT, rather than deriving or superseding those theories.

Paper Structure and Limitations

2. Methods

2.1. Conceptual Framework and Analogy

2.2. Elasticity and Material Parameters

Local Stiffness Variation

2.3. Incorporating Particle–Mirror Particle Dynamics

- Appendices D–E: Interference and entanglement analogues

- Appendices F–H: Black hole interiors, Hawking-like radiation, and potential resolution of the information paradox

2.4. Deriving the Modified Elastic Wave Equation

- is the standard tension term (like a drumhead),

- provides bending stiffness, including local stiffness changes,

- is an external force derived from a potential energy functional (discussed further in Appendix B).

2.5. Force Function and Persistent Waves

- Sustain persistent standing waves,

- Regulate wave amplitudes and frequencies via feedback from ,

- Reproduce stable interference patterns analogous to those seen in quantum experiments (Appendices D–E).

2.6. Relating Strain to Curvature and Einstein Field Equations

2.7. Composite Photons and Persistent Oscillations

- Masslessness (net zero deformation over one oscillation cycle),

- Gauge-Like Invariance (analogous to U(1) symmetry at low energies),

- Lorentz Invariance (through suitable tension and stiffness parameters).

2.8. Extreme Regimes: Black Hole Interiors and Cosmological Parameters

2.9. Introducing a Density-Driven Coupling Constant

3. Results

3.1. Unified Emergence of Gravity and Quantum-Like Behaviour

-

Gravitational AnalogyBy mapping strain to metric perturbations and relating the membrane’s elastic energy to a gravitational action, the STM model recovers equations structurally similar to the linearised Einstein Field Equations (EFE) [1–3]. Though not a comprehensive replacement for General Relativity (GR), it illustrates how continuum elasticity, with suitable parameters, might capture large-scale curvature effects.

-

Quantum-Like Wave BehaviourOn shorter length scales, the membrane hosts wave solutions modulated by local stiffness variations . These can form stable interference and entanglement analogues (see Appendices D–E), reminiscent of experimental outcomes in quantum settings [4–6]. The STM approach thus provides a single mechanical framework unifying gravitational-like curvature and wave interference, albeit as an analogy rather than a fundamental re-derivation of QFT.

3.2. Composite Photons: Consistency with QFT Principles

- 1.

-

Masslessness and Gauge-Like SymmetryBecause the net membrane deformation over one oscillation cycle cancels, the photon carries no rest mass. Additionally, the wave-plus-anti-wave pairing preserves a symmetry analogous to U(1) gauge invariance at low energies, although the STM model is complementary to the full gauge structure of quantum electrodynamics.

- 2.

-

Lorentz Invariance and PolarisationBy appropriate calibration of tension and stiffness (), the membrane’s wave propagation can respect relativistic principles, yielding two transverse modes that correspond to standard photon polarisations. High-energy processes like pair production would need further elaboration, but nothing in the STM picture contradicts standard QFT processes [7,8].

- 3.

-

No Forced Pair AnnihilationBecause the photon is not modelled as a localised particle–antiparticle pair, there is no immediate need for them to annihilate in the membrane picture. In standard QFT terms, apparent annihilations or pair productions emerge naturally from reconfigurations of the membrane’s global wave states, preserving consistency with observed quantum phenomena.

3.3. Deterministic Interference and Entanglement Analogues

-

Deterministic InterferenceLocal stiffness modulations and a conservative force (derived in Appendix B) can “lock in” interference nodes and antinodes. In effect, wave amplitude distributions on the membrane reproduce classical interference patterns, consistent with the shapes seen in typical quantum double-slit experiments (see Appendix D). However, no intrinsic randomness or wavefunction collapse is assumed here.

-

Entanglement AnaloguesWhen multiple particle waves share the membrane, their coupling via yields correlated modes that cannot be factorised into independent solutions—an analogue to quantum entangled states (see Appendix E). Detection corresponds to boundary condition changes that disturb the global wave, enforcing deterministic yet correlated outcomes.

3.4. Black Hole Interiors Without Singularities

-

Finite Curvature CapBy requiring infinite energy to achieve infinite curvature, the membrane cannot form a point-like singularity. Instead, one finds finite-amplitude standing waves in regions of extreme density (Appendix F). This parallels certain quantum gravity ideas where Planck-scale effects preclude classical singularities, though here explained via classical elasticity.

-

Information StorageIf the interior wave patterns remain stable, they can retain information about infalling matter. Thus, the STM model posits that black hole cores are not regions of infinite density but extremely stiff domains capable of encoding data in classical wave modes. This idea, while speculative, underscores the model’s capacity to host gravity-like and quantum-like features in one medium.

3.5. Modified Hawking Radiation and Information Leakage

-

Non-Thermal EmissionThe membrane stiffness near or inside the black hole can induce small deviations from a purely thermal spectrum, allowing highly redshifted signals—bearing imprints of interior wave modes—to escape over very long timescales (Appendices G and H). This might offer a gradual channel for information release, reducing or resolving the black hole information paradox.

-

Prolonged EvaporationAs black hole mass decreases, the modified emission spectrum can extend the lifetime compared to standard Hawking predictions, giving the interior wave modes more time to leak out encoded data. Confirming such effects, however, would require observational evidence well beyond current technology.

3.6. Connecting Vacuum Energy and the Cosmological Constant

-

Cosmological ConstantA uniform term acts like a cosmological constant, and by tuning the coupling , one may match the observed value of dark energy [17]. Small spatial variations in can then serve as perturbations to the vacuum energy density, opening possibilities for accounting for discrepancies like dark matter distributions or local Hubble tensions.

-

Dark Matter and Hubble TensionThe second coupling allows for distribution-level adjustments to vacuum energy, potentially explaining local discrepancies in expansion rates (Appendix I). Though speculative, these features show how a classical elastic framework might link microscopic wave phenomena to large-scale cosmological parameters.

4. Discussion

4.1. Unifying Quantum and Gravitational Concepts

4.2. Photons, Gauge Invariance, and Consistency with QFT

- Masslessness: The net membrane deformation over one oscillation cycle cancels out, implying no rest mass.

- Gauge-Like Symmetry: At low energies, the wave-plus-anti-wave structure can mimic U(1)-type gauge invariance, complementing standard quantum electrodynamics (QED). In practice, the STM approach does not seek to derive or supersede QFT’s gauge structure; it instead provides a continuum-based view in which massless excitations can naturally form.

- Preserved Lorentz Invariance and Polarisation: Through suitable choices of tension and bending stiffness (T and ), wave propagation respects relativistic constraints, yielding two transverse modes consistent with observed photon polarisation states.

4.3. Compatibility with the Higgs Mechanism

4.4. Deterministic Analogues of Quantum Phenomena

4.5. Black Holes, Singularity Avoidance, and Information Retention

-

Finite CurvatureInstead of a singularity, the membrane supports finite-energy standing waves in the high-density core (Appendix F). This scenario loosely parallels certain quantum gravity predictions where Planck-scale physics halts unbounded collapse.

-

Information EncodingIn principle, these standing waves could encode information about the collapsing matter. Since there is no true singularity, the model suggests that no absolute information destruction need occur. Still, rigorous numerical work would be required to confirm how the membrane stores and releases this information.

4.6. Connecting Vacuum Energy to Cosmological Scales

-

Dark Matter and Hubble TensionIf these inhomogeneities act gravitationally, they might mimic dark matter distributions or account for local discrepancies in the measured Hubble parameter (Appendix I). Verifying this idea would demand careful cosmological modelling, but the STM perspective at least outlines a potential continuum-based mechanism for linking micro-level wave energy to macro-level vacuum energy distributions.

4.7. Implications for Vacuum Energy Variations and the Hubble Tension

4.8. Rationale for the Constructs of the STM Model

4.9. Towards Experimental and Observational Testing

- 1.

-

Cosmological ObservationsSubtle deviations from the model—such as localised expansions or lensing anomalies—could indicate non-uniform vacuum energy as per variations. High-precision cosmological surveys might one day detect such signatures.

- 2.

-

Laboratory AnaloguesMetamaterials, acoustic systems, or optical waveguides with tunable refractive indices could mimic the role of . One could examine whether stable interference or multi-wave correlations arise deterministically, drawing parallels to the STM mechanism (Appendix J).

- 3.

-

Finite Element AnalysisProposed numerical simulations (Appendix L) might test whether a single value can reproduce both photon-like and electron-like interference patterns. If distinct parameters are required for different particles or wavelengths, the model would need refinement or additional coupling constants.

5. Conclusion

- 1.

- Numerical and Experimental Validation: Aligning the STM model’s parameters (, , E_STM, ) with experimental data through simulations and analogue experiments in metamaterials or acoustic systems.

- 2.

- Cosmological Alignment: Developing detailed models that match the STM framework with cosmological observations, such as supernova distances and the cosmic microwave background.

- 3.

- Black Hole Physics: Rigorously modelling horizon dynamics and evaporation processes to produce observable predictions differing from classical GR.

Statements

- Conflict of Interest: The author declares that there is no conflict of interest.

- Data Availability: All relevant data are contained within the paper and its supplementary appendices.

- Ethics Approval: This study did not involve any ethically related subjects.

- Funding: The author received no specific funding for this work.

Declaration of generative AI and AI-assisted technologies in the writing process

Acknowledgments

Acknowledgments

Conflicts of Interest

Abbreviations

| MDPI | Multidisciplinary Digital Publishing Institute |

| DOAJ | Directory of open access journals |

| TLA | Three letter acronym |

| LD | Linear dichroism |

Appendix A

Appendix A: Derivation of the Elastic Wave Equation

A.1 Overview

A.2 Assumptions and Definitions

- 1.

-

Small DeformationsWe assume the displacement field from equilibrium is small. This justifies using the linear approximation of strain and stress.

- 2.

-

Isotropic and Homogeneous (Base State)The STM membrane is considered isotropic and uniform in its baseline (unperturbed) material properties: elastic modulus , mass density , and tension T. Variations arise only from local oscillations or external forces.

- 3.

-

Thin Membrane ApproximationAlthough conceptually 4D, we draw on analogies with a 3D-plus-time membrane. The “thickness” is negligible or accounted for by effective parameters (). This approach parallels how one models a thin elastic sheet or plate, albeit with additional terms.

- 4.

-

Displacement FieldThe displacement vector in the membrane is . In some treatments, one may focus on a scalar u if motion is primarily normal to the membrane’s equilibrium surface. A vector form is straightforward but not essential for the core derivation.

A.3 Fundamental Equations of Continuum Mechanics

A.4 Stress–Strain Relationship

A.5 Strain–Displacement Relationship

A.6 From 3D Elasticity to a Membrane Equation

A.7 Introducing Bending Stiffness

A.8 Inclusion of Local Elastic Modulus Variation ΔE

A.9 Derivation of ΔE(x,y,z,t)

- Immediate Response: Reflects instantaneous changes in stiffness where oscillation energy is high.

- Time-Averaged Offset: Over many cycles, rapid fluctuations may average out, leaving a uniform baseline that behaves like vacuum energy.

- Distribution-Level Effects: One can further introduce a second constant (Appendix I) to handle spatially integrated effects, allowing persistent wave distributions to affect vacuum energy on larger scales.

A.10 Physical Interpretation

- 1.

- Local Wave Propagation: Tension drives ordinary membrane-like waves, while bending stiffness suppresses sharp curvature.

- 2.

- Feedback Mechanism: Where particle oscillations concentrate energy, the membrane stiffens (), modifying wave speeds and potential wave interference patterns.

- 3.

- Possible Cosmological Implications: The time-averaged uniform stiffness shift from can act as a cosmological constant, while slight spatial variations may produce dark-energy-like or dark-matter-like phenomena at large scales.

A.11 Summary

Appendix B: Derivation of the Force Function F ext

B.1 Overview

B.2 Potential Energy Functional

- T is the membrane’s effective tension.

- is its intrinsic elastic modulus.

- represents local stiffness variations due to particle oscillations (Appendix A).

B.3 Functional Variation to Obtain F ext

- Variation of the Tension Term

- Variation of the Bending Term

- again neglecting boundary terms. Additional partial derivatives of with respect to u can appear if explicitly depends on u; for simplicity, assume here that depends on the energy density associated with u, rather than on u itself in direct functional form. (See Section B.4 below for a more involved case.)

B.4 Incorporating ΔE(x,t) for Persistent Waves

- is the intrinsic coupling constant linking oscillation energy to local stiffness changes (Appendix A).

- represents a potential energy function associated with the particle’s oscillation, such as:

- with k an effective spring constant and a characteristic wavelength scale.

- introduces a feedback mechanism enforcing certain mode frequencies (associated, for example, with photon-like oscillations).

B.5 Final Expression for F ext

B.6 Interpretation and Physical Significance

- 1.

- Tension Term: Reflects standard wave-like behaviour of a tensioned membrane, analogous to a drumhead oscillation.

- 2.

- Bending Stiffness: Imposes higher energy costs on sharper curvatures, modulated by local oscillation energy. Larger near high-energy regions stiffens the membrane locally, changing wave propagation.

- 3.

- Feedback Mechanism: The explicit dependence of on u (and hence on wave amplitude or local potential energies) can reinforce specific mode frequencies, supporting stable or long-lived oscillations—analogous in some ways to resonant states in quantum mechanics.

B.7 Ensuring Energy–Frequency Consistency (E=hν)

B.8 Summary

- Conservative Force: By deriving from the potential energy functional , the STM model maintains a conservative system that can sustain persistent oscillations.

- Wave Lock-In: The explicit dependence of on wave amplitude and phase can tune the membrane to support wave modes at targeted frequencies.

- Analogy with Photon Frequencies: One may interpret these targeted frequencies as analogous to photon energies , although this is an analogy rather than a derivation of the quantum formalism.

Appendix C: Derivation of Einstein Field Equations and Time Dilation

C.1 Overview

- 1.

- Linking Membrane Strain to Metric Perturbations

- 2.

- Introducing an Elastic Energy–Based Action (Including Matter Fields)

- 3.

- Showing That Varying This Action Produces Field Equations Identical in Form to the Einstein Field Equations (EFE)

C.2 Metric Tensor and Displacement Field

C.3 Elastic Energy and the Action Principle

C.4 Variation of the Action and Emergence of EFE

- 1.

-

Variation of the Matter ActionFrom standard field theory in curved spacetime,

- which defines the stress–energy tensor .

- 2.

-

Variation of the Elastic EnergySince and , variations induce variations in . Carefully performing these variations (including integration by parts to handle derivatives) shows that, in the linearised regime,

- if one identifies appropriate proportionality factors.

C.5 Role of ΔE(x,y,z,t) and the Force Function

C.6 Cosmological Constant Λ

C.7 Time Dilation

C.8 Summary

- 1.

- Strain ↔ Metric Perturbations By linking to , we map mechanical strain to small deviations of the metric from flat spacetime.

- 2.

- Action Variation Yields EFE Structure Including elastic-plus-matter terms in a 4D action, then varying with respect to , recovers equations that parallel the Einstein Field Equations in the linearised regime.

- 3.

- Time Dilation and Effects like gravitational time dilation follow from , while a uniform offset in membrane tension or behaves as a cosmological constant .

- 4.

- Equivalence in the Linearised Limit With proper scaling ( etc.), the STM model is not merely an analogy—it can achieve structural equivalence to GR’s field equations for weak fields, thus providing a compelling mechanical interpretation of gravitational phenomena.

Appendix D: Deterministic Double-Slit Experiment Emergent Effects

D.1 Overview

D.2 The Governing Wave Equation with ΔE

- 1.

- is relatively small or slowly varying over the region of interest, enabling a quasi-uniform approximation.

- 2.

- The external force is derived from a conservative potential (Appendix B), allowing for steady-state (time-harmonic) solutions.

D.3 Double-Slit Boundary Conditions and Interference

D.3.1 Far-Field Approximation

D.3.2 Incorporating ΔE Feedback

- LocalisedIncreases: Where the wave amplitude is high, becomes larger if . This increased stiffness can prevent the wave from simply dispersing, stabilising the interference nodes/antinodes.

- Steady-State Modes: If is chosen to favour certain resonant frequencies, the interference pattern can become a long-lived or permanent structure.

D.4 Numerical Illustration (Conceptual)

D.5 Interpretation Compared to Quantum Theory

- 1.

-

Deterministic WavesThe interference pattern is a direct outcome of classical wave superposition in an elastic medium. No fundamental randomness or wavefunction collapse is needed.

- 2.

-

Persistent PatternsThe presence of and a suitably derived from a potential energy functional (Appendix B) ensures the pattern remains stable or standing over time.

- 3.

-

No Immediate ContradictionAlthough this classical approach does not replicate all quantum features (e.g., discrete detection events, Born rule probabilities), it does illustrate how wave-like interference can emerge from a non-quantum continuum. From the STM perspective, the “which slit?” dilemma is resolved by noting that the displacement field spans both slits continuously, so both slits contribute to the final pattern.

D.6 Summary

- Analogy to Quantum Double-Slit: The STM model replicates interference fringes deterministically, with membrane wave solutions passing through two slits and superposing on the far side.

- Role of: Local stiffness modulations lock in interference nodes and stabilise the standing wave pattern, preventing simple dissipation.

- Classical Yet Suggestive: While it lacks a probabilistic or fundamentally quantum interpretation, this example shows that many features attributed to wave–particle duality (in particular, interference) may also occur in a purely classical, deterministic wave setting—provided the medium has the right feedback mechanisms.

Appendix E: Deterministic Quantum Entanglement Emergent Effects

E.1 Overview

E.2 Multi-Particle Wave Solutions on the Membrane

- Nonlinear Stiffness Modulations: depends on the combined energy densities of both waves.

- Mirror Particle Effects: Interactions across the membrane can alter boundary conditions or local forces.

E.3 Coupled Equations and Non-Factorisable Modes

E.4 Deterministic Analogue of Entanglement

-

Global Mode StructureMeasurement (or detection) on one part of the membrane alters boundary conditions, thereby reconfiguring the entire standing wave pattern. This can manifest as correlated outcomes if the wave modes are strongly coupled.

-

No Hidden Variable NecessityThe correlations do not stem from non-local hidden variables but from the fact that both oscillations reside in a single continuum. The global wave solution enforces constraints akin to entangled states, yet in a deterministic system.

-

Limits to the AnalogyUnlike quantum theory, the STM model does not inherently reproduce probabilistic measurement statistics or fully replicate quantum measurement postulates. It shows, however, that non-factorisable modes—sometimes labelled “classically entangled”—can arise from purely classical wave coupling. **In Section E.8, we further explore how these correlations might extend to Bell-type violations and discuss how persistent, sub-Planck-scale waves could seed apparent randomness, though this remains speculative and does not equate to a full quantum derivation.**

E.5 Stability and Measurement Interpretation

-

Detector InteractionCoupling to a localised detector near particle 1 changes the boundary conditions, forcing the standing wave pattern to readjust.

-

Global Wave ReconfigurationParticle 2’s modes likewise shift to remain consistent with the single global solution. The result is a deterministic correlation in the final wave profile—an effect that parallels entanglement correlations.

E.6 Practical Example: Two-Slit Entanglement Analogue

E.7 Summary

-

Multi-Particle Coupling-driven stiffness variations create a coupling between separate particle-like oscillations on the STM membrane.

-

Non-Factorisable ModesOne obtains coupled eigenstates reminiscent of entangled quantum states in that they cannot be decomposed into independent modes.

-

Deterministic Yet CorrelatedThese correlated modes remain purely classical solutions to the membrane wave equation but can exhibit “entangled-like” correlations upon measurement or boundary condition changes.

-

Comparison with Quantum EntanglementAlthough not a full replacement for quantum entanglement (as aspects of locality and measurement probability differ), the STM model provides a classical wave demonstration that certain strongly correlated patterns need not rely on quantum mechanical formalisms alone.

E.8 Potential Extension: Bell Inequality Violations and Persistent Waves

E.8.1 Scope and Disclaimer

E.8.2 Entangled States as Non-Separable Displacement Modes

E.8.3 Measurement Operators and Correlation Functions

E.8.4 Persistent Waves as a Randomness Seed

- Proposed Mechanism: A background of persistent low-level waves at tiny (sub-Planck) scales, influenced by the mirror sector or vacuum boundary conditions. Over many runs, the wave’s slight variations in phase or amplitude cause chaotic divergence, so each run sees effectively different initial micro-states.

E.8.5 No-Signalling and Lorentz Invariance

E.8.6 Numerical Validation

E.8.7 Deterministic Chaos and Apparent Randomness

E.8.8 Conclusion

- No-signalling: Pre-existing global conditions, no instant communication.

- Lorentz invariance: Covariant elasticity, no preferred frame.

- Speculative Probability: The ensemble of sub-Planck excitations might explain quantum-like randomness, but it is not a rigorous derivation of the Born rule.

Appendix F: Singularity Prevention in Black Holes

F.1 Overview

F.2 Elastic Wave Equation in Strong Deformation Regimes

F.3 Stationary Solutions and Standing Waves in the Core Region

- 1.

-

High Stiffness Counteracts CurvatureAs the membrane deforms more severely, intensifies the local bending rigidity, halting runaway curvature.

- 2.

-

Finite-Amplitude Wave ModesRather than a singularity, the interior can form stable standing wave configurations. The radial dependence of these waves yields a maximum curvature well below the infinite limit of classical GR. Mathematically, solutions to

- can remain finite even under boundary conditions implying significant gravitational collapse.

- 3.

-

Avoiding Pathological BehaviourIn classical GR, singularities arise because curvature feedback is unbounded. In STM, feedback saturates once becomes large enough to sustain finite strains without further collapse.

F.4 Information Storage in Standing Wave Patterns

-

Stable Core ModesThe interior standing waves can, in principle, encode details of the collapse (amplitudes, phases, etc.). No singular region forms to destroy this information.

-

Potential for Evaporation or LeakageAs described in Appendices G–H, non-thermal components in Hawking-like radiation might gradually release these wave-encoded data over extremely long times. Although the precise mechanism would need rigorous numerical checks, the model implies that black hole interiors remain well-defined elastic regions rather than pathological singularities.

F.5 No Arbitrary Boundary Conditions

- 1.

-

No Breakdown of EquationsThe same elastic wave equation remains valid throughout the interior, thanks to self-regulating stiffness ().

- 2.

-

Physical RegularityBoundary conditions at (for a spherically symmetric collapse) or analogous “centre” coordinates are finite. The model thus stays within continuum mechanics, avoiding infinite curvature or metric discontinuities.

F.6 Summary

-

Runaway Curvature PreventedAs deformation grows in a black hole interior, sharply raises local bending stiffness, requiring infinite energy for infinite curvature—thus precluding a true singularity.

-

Finite-Energy Standing WavesInstead of a singularity, stable oscillatory modes form in the centre. This offers a classical elasticity interpretation akin to how some quantum gravity proposals regularise the Schwarzschild singularity [12,13].

-

Consistent Boundary ConditionsNo breakdown of the membrane equations occurs; the same wave equation applies throughout, eliminating the pathological region predicted by classical GR.

-

Information RetentionThese finite core modes can store information about the collapsing matter. The possibility of slow, non-thermal emission of this information is discussed further in Appendices G–H.

Appendix G: Modifications to Hawking Radiation and Potential Resolution of the Information Loss Paradox

G.1 Overview

G.2 Modified Horizon Structure and Finite Redshift

- 1.

-

Finite (But Large) RedshiftWhile curvature near the horizon still becomes extreme, it never reaches the fully infinite limit. The local membrane stiffness prevents total collapse. This means that outgoing signals, though highly redshifted, are not infinitely redshifted.

- 2.

-

Non-Singular CoreSince there is no true singularity, quantum field effects near the horizon can interact with interior wave modes in a way that differs from classical GR. The standard calculation of Hawking radiation, which presumes a particular horizon geometry, thus receives corrections.

G.3 Particle Creation as Reconfiguration of Wave Modes

-

Elastic Membrane PerspectiveThe membrane’s global wave modes include high-curvature interior solutions. Particle creation can be viewed as local fluctuations in these wave modes, influenced by both the horizon boundary conditions and the stiffness gradient.

-

Non-Thermal CorrectionsBecause modifies the dispersion relation and horizon geometry, the resulting Bogoliubov transformations (which map in-states to out-states) deviate from pure thermal behaviour. Small non-thermal terms can encode phase information about the interior wave structure.

G.4 Potential Information Leakage

- 1.

-

Standing Waves Retain InformationThe finite-energy core (Appendix F) stores data about infalling matter in stable wave patterns.

- 2.

-

Weak Non-Thermal ComponentsAs the black hole evaporates over long timescales, these non-thermal components—though minuscule—carry away correlations from the interior. In principle, if one collects all outgoing radiation, it might reconstruct the initial quantum state, preserving unitarity.

G.5 Consistency with Known Hawking Results

-

Late-Stage EvaporationAs the hole’s mass diminishes, standard GR predicts higher temperatures and faster evaporation. The STM approach introduces a feedback that can slow mass loss by maintaining additional wave modes near the horizon.

-

Very High Curvature ZonesNear the would-be singularity, the STM approach changes boundary conditions, thus altering the interior state and, consequently, the details of pair creation near the horizon.

G.6 Comparison with Traditional Resolutions

- 1.

-

Purely Classical Elastic ExplanationNo full quantum framework is invoked; instead, changes in membrane stiffness replace the singular region, letting information persist as classical waves.

- 2.

-

Non-Thermal OutletA slight but persistent leakage of interior wave patterns over time.

- 3.

-

Potential Observational SignatureIn principle, one might detect small deviations from thermal Hawking spectra if primordial or small black holes are ever observed near their end states. However, such signatures would be extremely faint.

G.7 Summary

-

Replacing Singularity-enhanced stiffness prevents infinite curvature, leaving a stable interior wave region.

-

Adding Non-Thermal ComponentsThe horizon geometry is subtly altered, allowing low-level emission that carries information about the interior.

-

Resolving Information LossOver extremely long timescales, the black hole can radiate away stored data, preserving unitarity in principle.

Appendix H: Modification to Black Hole Evaporation Rates

H.1 Overview

H.2 Standard Hawking Evaporation Timescale

H.3 Modified Emission Spectrum

H.4 Reduced Mass-Loss Rate and Extended Lifetimes

- 1.

-

Prolonged Late StagesThe final mass drop may take longer, giving more time for information-laden radiation to trickle out.

- 2.

-

Residual Mass or Remnant PossibilityIf the emission rate falls off steeply enough, one might even speculate about tiny remnants instead of complete evaporation. The STM model does not require remnants explicitly, but the possibility is not excluded by the existing equations.

H.5 Observational Consequences

- 1.

-

Late-Stage EmissionPrimordial black holes near the end of their evaporation might display non-thermal spectra or extended lifetimes compared to standard predictions. Detecting such deviations would require very high sensitivity and knowledge of background astrophysical processes.

- 2.

-

Absence of High-Energy Final BurstsStandard theory predicts a sudden, energetic burst in the final phases of black hole evaporation. In the STM model, the final phases might be less violent if non-thermal corrections spread out the energy release over a longer timescale.

- 3.

-

Information LeakageNon-thermal emission carrying correlation data (Appendix G) might manifest in subtle spectral line shapes or time correlations. Again, extremely challenging to observe in practice.

H.6 Summary

-

Modified Hawking SpectrumThe STM model’s internal wave structure and finite redshift factor yield a non-thermal correction to the emitted flux, slowing the evaporation rate compared to standard Hawking theory.

-

Prolonged EvaporationAs may be reduced, black holes live longer, providing more time for residual information to leak away in the emitted radiation.

-

Potential RemnantsDepending on how steeply alters emission at lower masses, stable or quasi-stable remnants could form, bypassing a complete evaporation scenario.

Appendix I: Mathematical Details of Density-Driven Vacuum Energy Variations

I.1 Overview

I.2 Definition of the Wave Distribution Operator F

I.3 Effective Vacuum Energy Offset ΔE eff

- is the time-averaged local stiffness increment, analogous to a uniform baseline shift.

- is a new coupling constant controlling how strongly persistent wave distributions modulate vacuum energy on larger scales.

I.4 Physical Interpretation and Scale Dependence

- 1.

-

Immediate Response ()The parameter handles the local, pointwise conversion of oscillation energy into stiffness changes, influencing phenomena like interference and short-range gravitational curvature.

- 2.

-

Long-Range Influence ()By integrating or smoothing over persistent wave distributions, captures how larger-scale, time-averaged patterns may shift the effective vacuum energy. Such effects might explain dark matter-like or dark energy-like structures if they act gravitationally.

- 3.

-

Choice of KernelKOne can select different kernels for F. A Gaussian kernel with a characteristic length L could localise the influence to a region of size L. Alternatively, a power-law kernel might allow for more extended-range correlations.

I.5 Consistency with the Action Principle

I.6 Future Work and Parameter Calibration

-

Theoretical ConstraintsOne may compare derived vacuum energy distributions with known large-scale structure to see if certain choices of and K can mimic dark matter haloes or local expansion rate anomalies.

-

Cosmological TensionsIf the local can vary regionally, then the Hubble tension (discrepancies in the measured Hubble constant at different scales) might be alleviated by slight inhomogeneities in vacuum energy.

-

Laboratory AnaloguesAlthough more speculative, advanced metamaterials or acoustic analogues might be designed to test whether distribution-level feedback leads to detectable wave changes at macro scales.

I.7 Summary

Appendix J: Experimental Setups and Expected Deviations Resulting from the STM Model Equations

J.1 Overview

J.2 Table-Top Analogue Experiments

- 1.

-

Membrane Analogues

- High-Tension Films: One could construct a literal tensioned membrane or thin plate whose local stiffness can be modulated externally (e.g., via temperature, electric fields, or embedded piezoelectric elements). By adjusting these modulations to mimic , it may be possible to observe stable interference patterns or correlated modes analogous to those in Appendices D–E.

- Small-Scale “Black Hole” Analogues: Though purely classical, one might attempt to mimic horizons or trapping regions in a curved elastic membrane—similar to fluid “dumb holes” in analogue gravity research. Observing wave propagation in such a system could provide insights into how affects horizon-like boundaries.

- 2.

-

Acoustic or Optical Metamaterials

- Intensity-Dependent Refractive Index: If a metamaterial’s refractive index changes with the local wave intensity, one could emulate the feedback mechanism . Stable interference fringes might form under conditions where conventional wave theory predicts partial decoherence.

- Transmission Through Double-Slit Analogues: With metamaterials designed to have a tunable refractive index profile, one could set up a double-slit configuration (Appendix D). If observed fringe patterns remain resilient to perturbations that normally cause decoherence, it might parallel the STM’s stabilised interference effect.

J.3 Quantum Mechanical Experiments

- 1.

-

Double-Slit Interference with Varying Environments

- Reduced Decoherence: If the STM-like feedback were real, one might expect interference fringes to remain stable under conditions where standard quantum theory predicts a partial washout. Detecting such anomalies would be challenging.

- Large Molecules: Experiments with increasing molecule size (fullerenes, etc.) have shown quantum interference. If future experiments push to larger masses, any unexplained enhancements in fringe contrast could hint at a “classical wave feedback” mechanism akin to STM.

- 2.

-

Entanglement Robustness

- Multi-Photon or Multi-Electron Entanglement: Testing whether entangled states resist decoherence under conditions that ordinarily degrade them. If the STM feedback were physically realised, it might manifest as unusually robust correlations.

J.4 Gravitational Wave Observations

-

Ringdown Frequencies After Black Hole MergersGravitational-wave detectors such as LIGO or Virgo measure the quasi-normal modes (“ringdown”) of merging black holes. If the interior structure differs from GR predictions (due to high near the would-be singularity), the final ringdown frequencies or damping times might show slight deviations from the Kerr black hole spectrum. Next-generation detectors (e.g., LISA) may have sensitivity to such small effects.

-

No Obvious Deviations in Strong Field Regime YetCurrent gravitational-wave data align well with GR; any STM-induced anomalies would likely be very small, especially for large black holes.

J.5 High-Energy Particle Colliders

- 1.

-

Casimir Effect

- Shifts in Plate Separation Forces: If the underlying vacuum energy is modulated by local wave intensities, one might detect small deviations from the standard Casimir force between parallel plates.

- Ultra-High-Precision Measurements: Advances in Casimir force experiments might eventually reveal minute discrepancies that could be interpreted as an STM-like feedback in vacuum energy.

- 2.

-

Vacuum Birefringence or Photon–Photon Scattering

- Polarisation-Dependent Shifts: Some versions of quantum electrodynamics (QED) predict minuscule birefringence in strong fields. An STM-based “elastic sub-structure” might add small corrections to these predictions, though existing constraints are already tight.

J.6 Cosmological Observations

- 1.

-

Spatial Variations in Dark Energy

- Dark Matter-Like Lensing: Regions with higher wave energy density might mimic additional gravitational mass.

- Hubble Tension: Slight local modifications to expansion rates could reconcile discrepant Hubble parameter measurements if tuned appropriately. However, no detailed fit to cosmological data yet exists under the STM framework.

- 2.

-

CMB Anisotropies

- If inhomogeneous vacuum energy modifies the growth of structure, one might see specific signatures in the Cosmic Microwave Background (CMB) power spectrum or lensing. Again, real constraints would require a full-blown STM-based cosmological model.

J.7 Practical Feasibility and Challenges

- Planck-Scale Stiffness: The membrane’s baseline modulus is estimated to be of order , implying extremely high energy scales.

- Weak Deviations: Deviation from standard theories (QFT, GR) is likely small, except in extreme environments (e.g., near black hole singularities or the Planck scale).

- Analogue vs. Real Tests: Laboratory experiments with membranes or metamaterials serve primarily as conceptual analogues. Actual astrophysical or cosmological tests would require extraordinary precision or new phenomena to be uncovered.

J.8 Summary

- Laboratory Analogues: Mechanical or optical setups with intensity-dependent stiffness or refractive index can test the concept of -induced wave stabilisation.

- Quantum and Gravitational Observations: Rare or subtle deviations in interference, entanglement, gravitational wave ringdown, or black hole evaporation could offer hints of an STM-like mechanism.

- Cosmological Fits: Allowing for inhomogeneous vacuum energy might address phenomena like the Hubble tension or dark matter distributions, but quantitative modelling is needed.

Appendix K: Estimation of Constants for the STM Model

K.1 Overview

K.2 Intrinsic Elastic Modulus E STM

K.3 Membrane Density ρ and Tension T

K.4 Effective Spring Constant k

K.5 Coupling Constant α and Localised Stiffness Changes

- 1.

-

Setto the Measured Vacuum EnergyObservationally, in natural units.

- 2.

-

Relateto typical quantum fluctuationsOne might integrate zero-point energies up to some cutoff, or consider other vacuum estimates.

- 3.

-

Solve forAdjust so that the time-averaged matches .

K.6 Introducing β for Distribution-Level Effects

- 1.

-

Spatial Smoothing OperatorIf one chooses a kernel and an averaging scale L, then can be tuned to reproduce local anomalies in dark matter-like distributions or local expansion rates.

- 2.

-

Hubble TensionBy allowing slight differences in vacuum energy across cosmic distance scales, might reconcile the Hubble constant measured locally (e.g., via supernova data) with that inferred from early-universe data (CMB, BAO).

K.7 Connection to Vacuum Energy and Λ

- This offset does not overshadow local gravitational phenomena,

- Small fluctuations do not break known observational constraints (e.g., big bang nucleosynthesis, CMB anisotropies),

- It remains stable over cosmic timescales or evolves in ways consistent with dark energy observations.

K.8 Estimating α and β Numerically

- 1.

-

Double-Slit InterferenceBy comparing the predicted intensity patterns for photons and electrons (Appendix L), one could tweak to see if the same value fits both data sets. If a single is insufficient, the model might need extra scale-dependent couplings.

- 2.

-

Black Hole Evaporation RatesAdjusting or might alter the late-stage black hole evaporation spectrum (Appendices G–H). If one tries to match hypothetical observational data (for instance, from primordial black hole bursts), these constants could be constrained.

- 3.

-

Inhomogeneous Cosmological SimulationsIncorporating in large-scale structure codes, one might ask if small fluctuations in vacuum energy (driven by wave distributions) can reproduce any known anomalies (e.g., mismatch in lensing signals vs. luminous matter).

K.9 Summary

- sets the baseline stiffness scale for linking strain to curvature in a manner akin to the Einstein Field Equations.

- must be chosen so wave speeds remain at or below c.

- handles local, immediate conversions of oscillation energy to modulus changes, possibly explaining vacuum energy or interference patterns.

- introduces distribution-level, larger-scale modifications to vacuum energy, potentially addressing dark matter-like or Hubble tension effects.

- Tuning to known phenomena—ranging from double-slit interference to cosmic expansion—would require a mix of numerical simulation, laboratory analogues, and cosmological data comparisons.

Appendix L: Finite Element Analysis for Determining Coupling Constants

L.1 Overview

L.2 Setup for the Double-Slit Simulation

- 1.

-

Geometry

- A 2D cross-sectional plane through the membrane, with slit separation d and slit width w, and a distance to the observation screen.

- The domain extends sufficiently beyond the slits so boundary reflections or absorption can be managed.

- 2.

-

Particle Properties

- Photon case: Wavelength in the relevant frequency range (e.g., visible or another testable regime).

- Electron case: de Broglie wavelength for electrons of given momentum/energy.

- 3.

-

Baseline STM Parameters

- from Appendix K, chosen to ensure physically reasonable wave speeds and bending.

- An initial guess for the local oscillation-to-stiffness coupling, possibly derived from vacuum energy considerations.

- 4.

-

Boundary Conditions

- The slits at have specified aperture geometry.

- The incoming wave may be approximated by a plane wave (for the photon case) or by a plane wave modulated by a de Broglie wavelength (for the electron case).

L.3 Numerical Procedure

- 1.

-

DiscretisationImplement the STM wave equation

- in a finite element solver (e.g., COMSOL, ANSYS, or an open-source equivalent). One may either solve it directly in the time domain or assume time-harmonic solutions and solve in the spatial domain.

- 2.

-

Initial Guess forSet . If is also under test (Appendix I), choose a provisional . Keep or in the solver.

- 3.

-

Compute Interference PatternLook at the numerically computed intensity on the observation screen at . Extract the fringe spacing and contrast.

- 4.

-

Compare to Experimental Data

- Photon Data: Standard laser-based double-slit experiments, measuring fringe spacing and intensity distribution.

- Electron Data: Electron diffraction experiments at comparable slit separations and energies, again measuring fringe patterns and comparing with quantum mechanical predictions.

- 5.

-

Iterative Parameter AdjustmentAdjust (and if relevant) to minimise the discrepancy between the STM-predicted fringe patterns and the measured ones. For instance, define a cost function:

- over discrete points i on the detection plane. Numerical optimisation then yields an optimal .

L.4 Analysis of Results

- 1.

-

SingleFits Both Photons and Electrons

- If , the STM model gains simplicity and generality. A single coupling constant may suffice to reproduce interference across multiple particle types.

- 2.

-

DifferentValues

- If the best-fit values for photons and electrons diverge significantly, it suggests the STM model requires additional scale-dependent couplings or separate constants for massive vs. massless excitations.

- 3.

-

Role of

- If distribution-level effects become relevant, one might extend the analysis to see if incorporating spatial averaging (Appendix I) alters the predicted fringe structures. Typically, might matter less at small laboratory scales, unless the experiment is designed to accumulate persistent waves over time.

L.5 Future Extensions

- 1.

-

Multiple Slit or Advanced InterferometerTesting the STM model in multi-slit or Mach–Zehnder configurations might yield further constraints on .

- 2.

-

Energy DependenceOne might vary the particle energy for electrons or the photon wavelength, checking how well the same fits different energies. If must vary with energy/frequency, that indicates a non-trivial scale dependence.

- 3.

-

3D Full SimulationsFor completeness, a 3D FEA would capture more realistic boundary geometries and wave propagation. Although more computationally demanding, it could verify the stability of the patterns predicted in 2D cross-sections.

L.6 Summary

-

Conceptual ValidationFinite element analysis offers a direct means to solve the STM wave equation for a double-slit scenario, comparing the resulting interference fringes to experimental data for photons and electrons.

-

Single or MultipleA single coupling constant might suffice if the model is truly universal at low energies, but discrepancies could necessitate additional parameters or scale-dependent forms.

-

Practical FeasibilityWhile feasible in principle, implementing and interpreting such simulations would demand careful numerical treatment (especially regarding boundary conditions, damping, or high operators). Still, it provides a concrete strategy to test whether STM’s deterministic interference analogies can quantitatively align with real-world interference experiments.

Appendix M: Glossary of Symbols

Fundamental and Physical Constants

-

cSpeed of light in vacuum.

-

GGravitational constant.

-

ℏReduced Planck’s constant .

-

Cosmological constant, commonly interpreted as vacuum energy in GR.

-

Boltzmann’s constant (when discussing thermal aspects of black hole radiation).

-

In various contexts, these denote particle mass, angular frequency, and wavelength, respectively.

STM Model Parameters and Fields

-

The displacement field of the STM membrane, indicating how each point in spacetime shifts from its equilibrium.

-

Effective mass density of the membrane.

-

TTension in the STM membrane, contributing to wave-like behaviour ().

-

Intrinsic elastic modulus of the membrane. Sets the baseline stiffness for bending ().

-

Local variation in the elastic modulus due to oscillations. Defined via or more elaborate expressions (e.g., Appendix B).

-

Intrinsic coupling constant relating oscillation energy densities to local stiffness changes. Governs short-range interactions that modulate .

-

A second coupling constant for distribution-level effects, linking persistent wave energy distributions to large-scale or inhomogeneous vacuum energy changes (Appendix I).

-

kEffective spring constant in local potential energy functions (Appendix B). Sometimes used to link particle mass/energy to membrane oscillation parameters.

Elasticity and Geometry

-

,Strain and stress tensors in the membrane, used in Hooke’s law: .

-

,The Laplacian and the biharmonic operator, respectively. Appear in the tension () and bending () terms of the STM wave equation.

-

Inertial term in the membrane’s equation of motion.

-

External force contribution derived from a potential energy functional (Appendix B). Summarises interactions not captured by tension or bending alone.

-

Effective vacuum energy offset combining local and integral transforms of persistent wave distributions via (Appendix I).

Gravitational and Relativistic Quantities

-

Minkowski metric for flat spacetime.

-

Full metric with small perturbations .

-

Strain tensor in the relativistic (linearised) sense.

-

Greybody factor in black hole evaporation integrals (Appendix H). Can be modified by STM boundary conditions.

-

Stress–energy tensor representing matter–energy distributions in standard GR analogies.

-

Ricci tensor and Ricci scalar, appear in linearised Einstein Field Equations analogies (Appendix C).

-

Common constant in Einstein’s equations.

Energy and Oscillations

-

orLocal energy density of the membrane oscillations. Forms the basis for computing .

-

Vacuum energy density. Related to the cosmological constant by .

-

Time-averaged wave energy density (Appendix I), used in integral operator transforms for large-scale vacuum energy variations.

-

Integral or smoothing operator, aggregating persistent wave densities over spatial regions to produce inhomogeneous .

Wave and Field Equations

-

Tension term yielding wave-like behaviour akin to drumhead vibrations.

-

Bending stiffness, elevated locally by oscillation-driven . Prevents infinite curvature in black hole cores (Appendices F–H).

-

Time-Harmonic FormsOften, is used to simplify the PDE in steady-state scenarios (e.g., double-slit interference).

-

Bogoliubov TransformationsIn black hole evaporation contexts, these transformations convert in-states to out-states, normally yielding a thermal spectrum. Modifications appear if horizon geometry or interior modes deviate from classical GR (Appendices G–H).

Cosmological and Quantum Considerations

-

,The uniform or time-averaged part of , interpreted as vacuum energy (Appendix K). Tuning aligns it with the observed .

-

Dark Matter / Hubble TensionSlight spatial variances in might mimic dark matter gravitational effects or local expansions (Appendix I).

-

Hawking RadiationIn standard theory, black holes radiate thermally with temperature . STM modifies this into a non-thermal component (Appendices G–H).

References

- A. Einstein, “The Foundation of the General Theory of Relativity,” Annalen der Physik, 49(7), 769–822 (1916).

- C. W. Misner, K. S. Thorne, and J. A. Wheeler, Gravitation, W. H. Freeman and Company, 1973.

- R. M. Wald, General Relativity, The University of Chicago Press, 1984.

- M. E. Peskin and D. V. Schroeder, An Introduction to Quantum Field Theory, Addison-Wesley, 1995. [CrossRef]

- S. Weinberg, The Quantum Theory of Fields, Vol. I, Cambridge University Press, 1995.

- L. Mandel and E. Wolf, Optical Coherence and Quantum Optics, Cambridge University Press, 1995. [CrossRef]

- W. Heitler, The Quantum Theory of Radiation, 3rd ed., Oxford University Press, 1954.

- F. Sauter, “Über das Verhalten eines Elektrons im homogenen elektrischen Feld nach der relativistischen Theorie Diracs,” Zeitschrift für Physik, 69, 742–764 (1931).

- E. Joos, H. D. Zeh, C. Kiefer, D. J. W. Giulini, J. Kupsch, and I. O. Stamatescu, Decoherence and the Appearance of a Classical World in Quantum Theory, Springer, 2003.

- G. Greenstein and A. G. Zajonc, The Quantum Challenge: Modern Research on the Foundations of Quantum Mechanics, Jones and Bartlett, 2006. [CrossRef]

- A. Zeilinger, “Experiment and the Foundations of Quantum Physics,” Rev. Mod. Phys., 71, S288–S297 (1999).

- R. Penrose, “Gravitational Collapse and Space-Time Singularities,” Phys. Rev. Lett., 14, 57–59 (1965). [CrossRef]

- A. Ashtekar and M. Bojowald, “Quantum Geometry and the Schwarzschild Singularity,” Class. Quantum Grav., 23, 391–411 (2006). [CrossRef]

- S. W. Hawking, “Particle Creation by Black Holes,” Commun. Math. Phys., 43, 199–220 (1975). [CrossRef]

- A. G. Riess et al., “Observational Evidence from Supernovae for an Accelerating Universe and a Cosmological Constant,” Astron. J., 116, 1009–1038 (1998). [CrossRef]

- S. Perlmutter et al., “Measurements of Ω and Λ from 42 High-Redshift Supernovae,” Astrophys. J., 517, 565–586 (1999).

- S. Weinberg, “The Cosmological Constant Problem,” Rev. Mod. Phys., 61, 1–23 (1989).

- Wheeler, J. A. & Feynman, R. P., “Interaction with the Absorber as the Mechanism of Radiation,” Reviews of Modern Physics 17, 157–181 (1945). [CrossRef]

- Dirac, P. A. M., “Classical Theory of Radiating Electrons,” Proceedings of the Royal Society A 167, 148–169 (1938). [CrossRef]

- Cramer, J. G., “The Transactional Interpretation of Quantum Mechanics,” Reviews of Modern Physics 58, 647–687 (1986). [CrossRef]

- Wheeler, J. A. & Feynman, R. P., “Classical Electrodynamics in Terms of Direct Interparticle Action,” Reviews of Modern Physics 21, 425–433 (1949). [CrossRef]

Disclaimer/Publisher’s Note: The statements, opinions and data contained in all publications are solely those of the individual author(s) and contributor(s) and not of MDPI and/or the editor(s). MDPI and/or the editor(s) disclaim responsibility for any injury to people or property resulting from any ideas, methods, instructions or products referred to in the content. |

© 2025 by the authors. Licensee MDPI, Basel, Switzerland. This article is an open access article distributed under the terms and conditions of the Creative Commons Attribution (CC BY) license (http://creativecommons.org/licenses/by/4.0/).