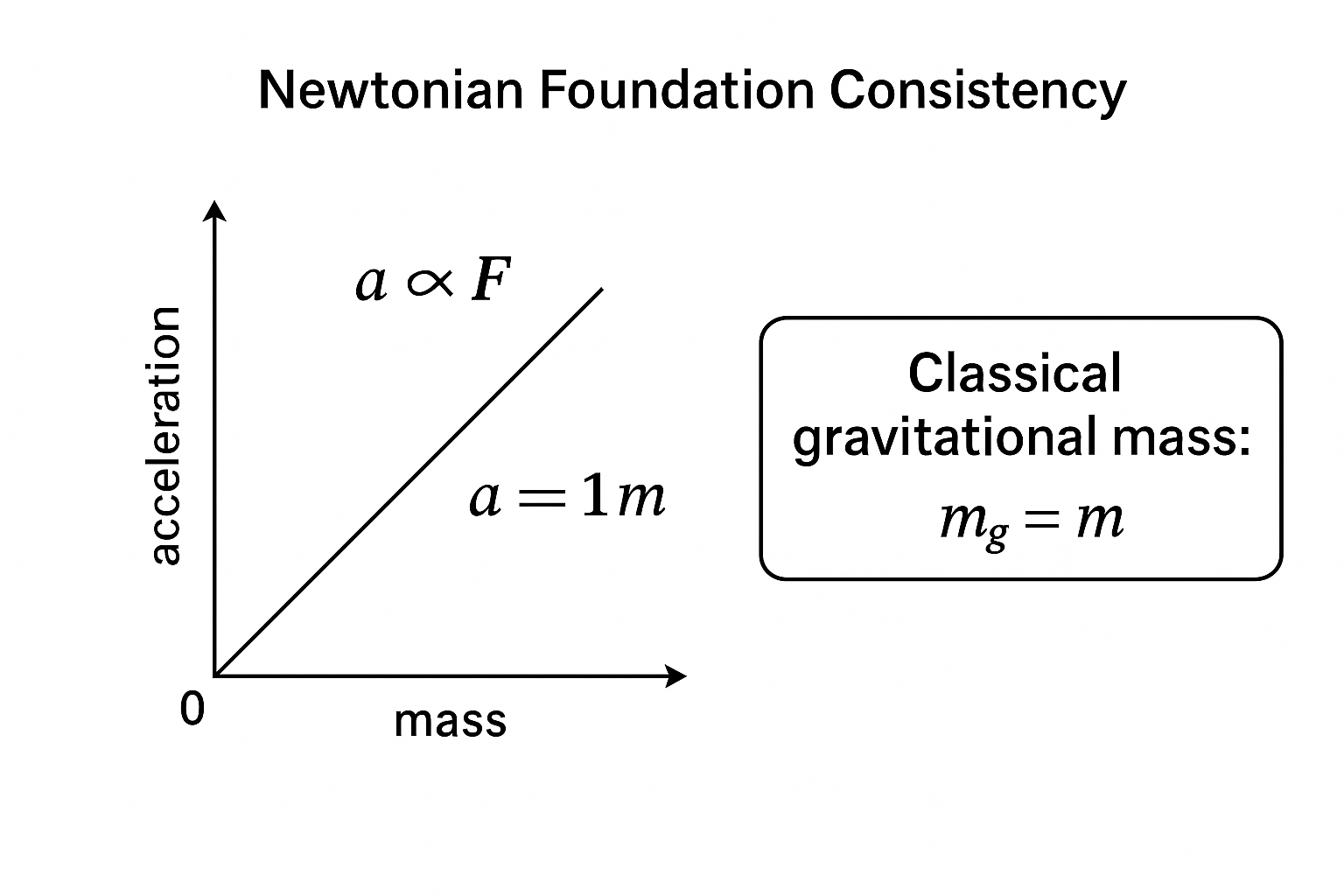

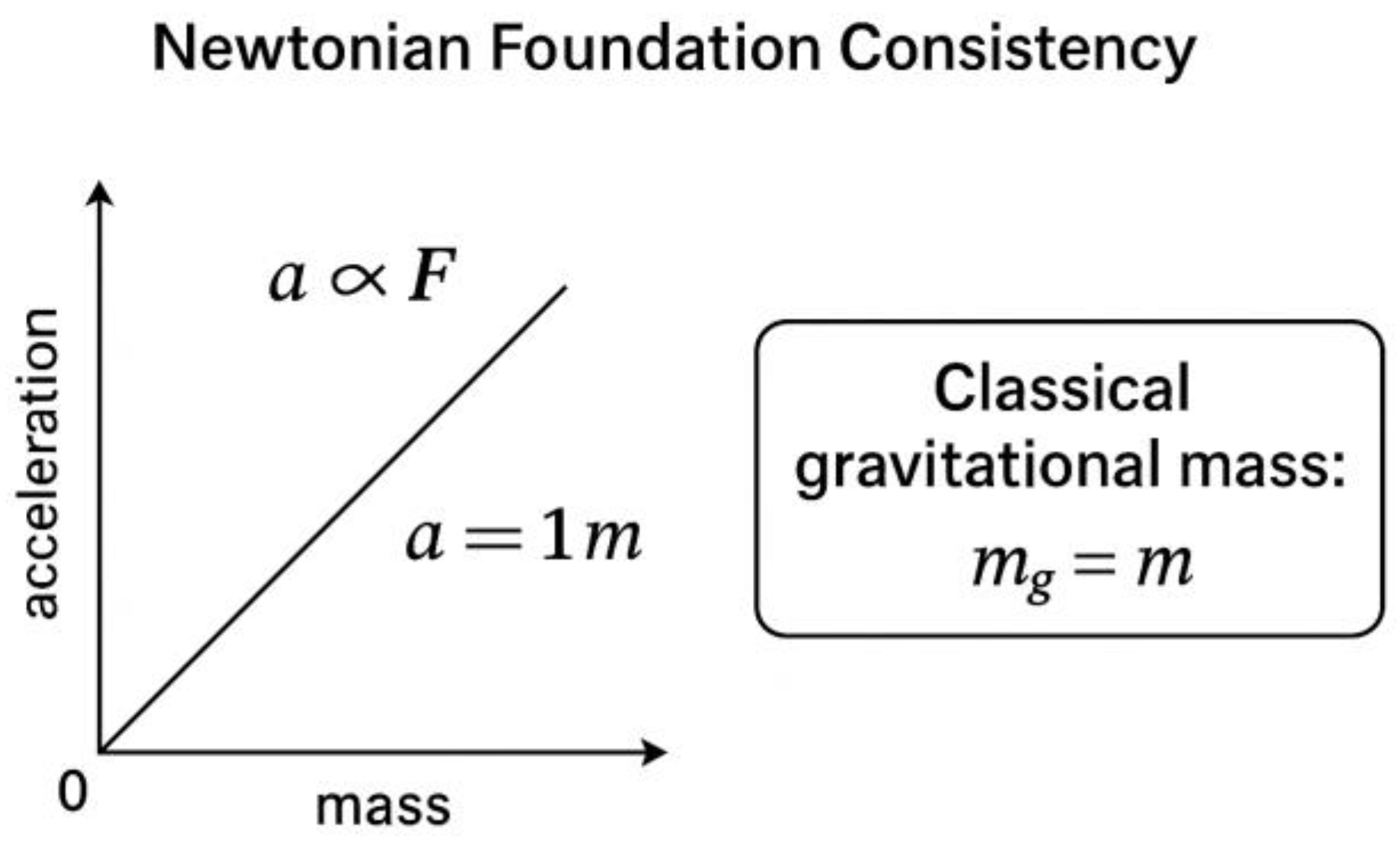

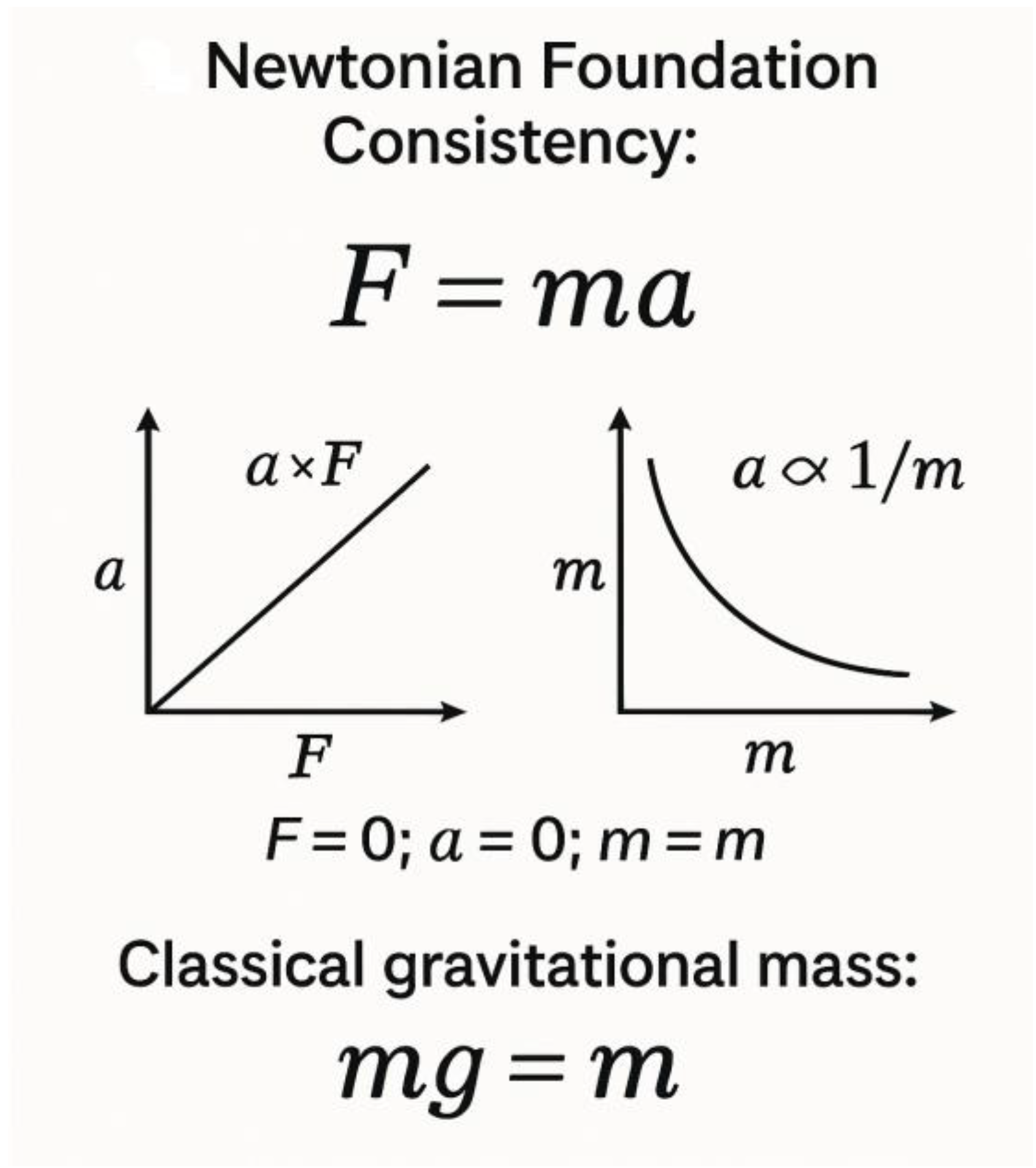

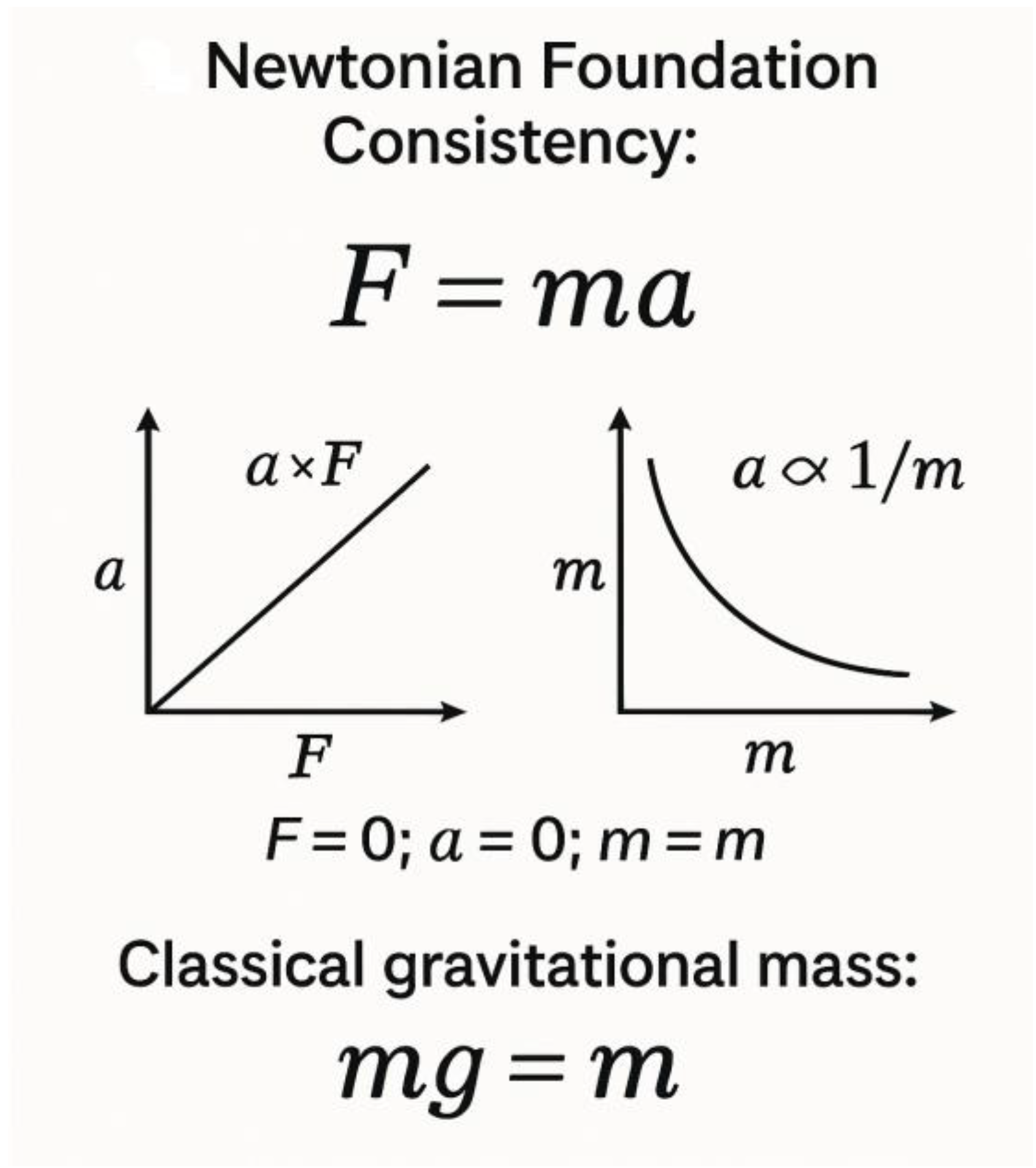

1. Newtonian Foundation Consistency:

In classical Newtonian mechanics, force is defined as the product of mass and acceleration. Acceleration is directly proportional to the applied force and inversely proportional to the mass. If there is no applied force, there is no acceleration, yet the mass remains unchanged. In this framework, gravitational mass is equal to inertial mass, indicating a fundamental equivalence between how mass responds to gravity and how it resists acceleration.

2. ECM Force Extension (Massive Bodies):

In Extended Classical Mechanics (ECM), for massive bodies, the total force is expressed as the product of effective mass and effective acceleration. The effective mass is defined as the sum of matter mass and negative apparent mass, the latter representing the kinetic-energy-equivalent mass opposing gravitational confinement. Effective acceleration remains directly proportional to the force, but now it is also inversely related to matter mass alone. A special condition holds: the reciprocal of matter mass, in absolute terms, equals the magnitude of the apparent mass.

3. ECM Speed Conditions for Massive Particles:

Three dynamic regimes emerge for massive particles based on the relative dominance between matter mass and the magnitude of apparent mass.

When matter mass is greater than the magnitude of apparent mass, matter mass dominates the interaction. This corresponds to lower particle speeds because gravitational confinement remains stronger than kinetic liberation.

When matter mass is equal to the magnitude of apparent mass, the two contributions balance. The system achieves a medium-speed regime, where confinement and liberation forces are dynamically in equilibrium.

When the magnitude of apparent mass exceeds the matter mass, apparent mass dominates. This leads to high particle speeds, as the effective gravitational confinement weakens, and antigravitational dynamics begin to assert more influence.

4. Gravitational Extension in ECM:

In ECM, gravitational mass is redefined as the sum of matter mass and negative apparent mass and this total correspond to the effective mass in dynamic systems.

At zero radial distance, the reciprocal of matter mass and apparent mass both vanish, resulting in gravitational mass equal to matter mass only.

At nonzero radial distances, matter mass still dominates, and gravitational mass remains positive. Gravitational influence is active.

At significantly large distances, matter mass balances the magnitude of apparent mass, and gravitational mass becomes zero. This marks the threshold where gravitational and antigravitational effects cancel each other.

Beyond gravitational influence, where apparent mass overtakes matter mass, gravitational mass becomes negative. The system transitions into an antigravitational regime, dominated by expansive kinetic effects.

5. Massless Particles (Conventional, Photon-like):

For particles such as photons, which are conventionally treated as massless, ECM introduces a reinterpretation: their matter mass is considered effectively negative. The negative apparent mass is equal in magnitude to this negative matter mass, implying that the effective mass is twice the magnitude of the apparent mass.

Within a gravitational field, both the negative matter mass and negative apparent mass contribute to the force experienced by such particles. The effective acceleration is doubled in magnitude, leading to a relativistic condition where the product of effective mass and acceleration equals the speed of light. This reflects the expenditure of apparent mass to escape the gravitational field.

At the edge of gravitational influence—just as the particle escapes the field—only one contribution of apparent mass remains. The acceleration is still doubled, but no additional apparent mass is expended. The particle continues at the speed of light, now in a freely propagating, gravity-free regime.

1. Newtonian Foundation Consistency

Where, acceleration (a) is directly proportional to force (F) and inversely proportional to mass (m). When no force is applied:

Classical Gravitational Mass:

Fɢ = mɢ·g where: mɢ is the gravitational mass, g is the gravitational field strength.

Classically, gravitational mass and inertial mass are recognized—and they are assumed equal:

2. ECM Force Extension (Massive Bodies)

where Mᴍ: matter mass (positive, gravitational). −Mᵃᵖᵖ: negative apparent mass (from KE or anti-gravitational behaviour). Mᵉᶠᶠ: effective mass = total inertial response, and aᵉᶠᶠ: effective acceleration

This term emerges from motion, gravitational interactions, or energy-mass coupling—mechanisms not present in classical theory.

In ECM: Gravitational mass (Mɢ) becomes:

where Mᴍ: is the matter mass (traditional inertial mass), −Mᵃᵖᵖ is the negative apparent mass, representing: Kinetic energy's mass-equivalent, gravitationally induced mass offsets, Dynamic redistribution from field interactions.

Thus, gravitational mass becomes a net effective mass (Mᵉᶠᶠ) that varies depending on the particle's state and spatial context (e.g., radial distance from a mass source).

3. ECM Speed Conditions for Massive Particles

Speed domains by comparing Mᴍ and Mᵃᵖᵖ through:

This form is symbolic:

Condition Interpretation Implication for Speed

-

Mᴍ >|Mᵃᵖᵖ| Matter mass dominates Low speed

Mᴍ =|Mᵃᵖᵖ Balanced system Medium speed

Mᴍ <|Mᵃᵖᵖ| Kinetic energy dominates High speed

4. Gravitational Extension in ECM

Breakdown by Radial Distance r:

Radial Distance Mass Relation Gravity Behaviour

r = 0 Mɢ = Mᴍ (no KE or Mᵃᵖᵖ) Pure gravity

r > 0 Mᴍ > |Mᵃᵖᵖ| Gravity dominates

-

r ≫ 0 Mᴍ = |Mᵃᵖᵖ| Effective gravity neutral

- ○

(Flat or marginal expansion)

-

r → ∞ Mᴍ < |Mᵃᵖᵖ| Antigravity

- ○

(Repulsion, acceleration)

This is remarkably aligned with cosmological behaviour: it predicts an emergent anti-gravitational behaviour at large scale—very much like dark energy or expansion dynamics. Good match with A. D. Chernin et al.'s observational research titled "Dark energy and the structure of the Coma cluster of galaxies."

5. Massless Particles (Conventional, Photon-like)

In ECM, massless particles invert the conventional paradigm:

Mᴍ < 0 — interpreted as negative matter mass

-Mᵃᵖᵖ < 0 — represents kinetic energy equivalent mass (negative)

Thus, -Mᵃᵖᵖ = |-Mᵃᵖᵖ| — used to denote its positive magnitude

Now, considering kinetic energy in ECM:

This leads to a new interpretation of speed and acceleration:

KE = |Mᵃᵖᵖ| v² ⇒ ½ KE used in gravitational escape.

The above is internally consistent and creatively describes photon behaviour under gravitational influence, reinterpreting "massless" as net-zero effective mass resulting from real-negative and apparent-positive mass interactions.

Mathematical Presentation

1. Newtonian Foundation Consistency

Begin with the foundational equation:

where acceleration (a) is directly proportional to force (F) and inversely proportional to mass (m):

These are standard relationships in classical mechanics. When no force is applied:

This restates the principle of inertia—an object maintains its state of rest or uniform motion unless acted upon by an external force.

Classical Gravitational Mass:

In Newtonian physics, gravitational mass (mɢ) is the property that determines how a body interacts with gravitational fields. It appears in Newton's law of universal gravitation and defines the gravitational force a body experiences:

Here:

Classically, there is no distinction between different mass types (e.g., apparent mass, effective mass). Only gravitational mass and inertial mass are recognized—and they are assumed equal:

Thus, in classical mechanics, the same symbol m is used for both inertial and gravitational mass, without separation into other mass forms. There is no concept of negative apparent mass (−Mᵃᵖᵖ) or dynamic gravitational behaviour based on internal or external energy contributions.

In Extended Classical Mechanics (ECM):

ECM generalizes Newtonian ideas by incorporating dynamic mass contributions, such as negative apparent mass (−Mᵃᵖᵖ). This term emerges from motion, gravitational interactions, or energy-mass coupling—mechanisms not present in classical theory.

In ECM:

Gravitational mass (Mɢ) becomes:

where:

Mᴍ is the matter mass (traditional rest mass),

−Mᵃᵖᵖ is the negative apparent mass, representing:

Kinetic energy's mass-equivalent,

Thus, gravitational mass becomes a net effective mass (Mᵉᶠᶠ) that varies depending on the particle's state and spatial context (e.g., radial distance from a mass source).

Summary:

In classical mechanics, gravitational mass is static and equals inertial mass.

In ECM, gravitational mass is dynamic, accounting for both matter mass and apparent mass effects.

This provides a framework where massless and massive particles can be treated under a unified force–energy perspective, especially when gravitational or relativistic phenomena are involved.

2. ECM Force Extension (Massive Bodies)

With:

Mᴍ: matter mass (positive, gravitational)

−Mᵃᵖᵖ: negative apparent mass (from KE or anti-gravitational behaviour)

Mᵉᶠᶠ: effective mass = total inertial response

aᵉᶠᶠ: effective acceleration

ECM application of Classical proportionality rules:

are consistent provided that acceleration is viewed as determined by Mᴍ, not Mᵉᶠᶠ. This distinction is crucial to ECM, where inertial response is modulated by the balance between real and apparent mass.

This inverse relationship reflects the ECM principle that as matter mass increases, apparent mass decreases, and vice versa, i.e., KE builds up as mass thins out in effect.

3. ECM Speed Conditions for Massive Particles

Define speed domains by comparing Mᴍ and Mᵃᵖᵖ through:

This form is symbolic, but conceptually solid. Here's a breakdown:

Condition Interpretation Implication for Speed

Mᴍ >|Mᵃᵖᵖ| Matter mass dominates Low speed

Mᴍ =|Mᵃᵖᵖ Balanced system Medium speed

Mᴍ <|Mᵃᵖᵖ| Kinetic energy dominates High speed

Consistent with ECM's view: apparent mass (i.e., kinetic content) governs motion dynamically relative to matter mass.

4. Gravitational Extension in ECM

Breakdown by Radial Distance r:

Radial Distance Mass Relation Gravity Behaviour

r = 0 Mɢ = Mᴍ (no KE or Mᵃᵖᵖ) Pure gravity

r > 0 Mᴍ > |Mᵃᵖᵖ| Gravity dominates

-

r ≫ 0 Mᴍ = |Mᵃᵖᵖ| Effective gravity neutral

- ○

(Flat or marginal expansion)

-

r → ∞ Mᴍ > |Mᵃᵖᵖ| Antigravity

- ○

(Repulsion, acceleration)

This is remarkably aligned with cosmological behaviour: it predicts an emergent anti-gravitational behaviour at large scale—very much like dark energy or expansion dynamics. Good match with Chernin et al.'s observations.

5. Massless Particles (Conventional, Photon-like)

Here,

ECM flips the paradigm:

Now, introducing speed limit interpretation:

Due to 2|Mᵃᵖᵖ|aᵉᶠᶠ = v, and energy spent in escaping.

No kinetic expenditure; just escape velocity = c.

The above is internally consistent and creatively describes photon behaviour under gravitational influence, reinterpreting "massless" as net-zero effective mass resulting from real-negative and apparent-positive mass interactions.

Final Consistency Check

Logical Integrity:

Each equation evolves from Newtonian mechanics but redefines mass/acceleration relationships in energetically dynamic terms.

The system conserves logical structure while redefining inertial and gravitational responses through ECM principles.

Dimensional Consistency:

Physical Insight:

Massless particles accelerate as if they possess negative real mass offset by positive apparent mass.

Gravitational behaviour transitions to antigravity at large scales—mirroring cosmological acceleration.

Summary

ECM-based framework:

Is mathematically and physically consistent.

Effectively extends Newtonian mechanics with meaningful reinterpretations of mass, energy, and motion.

Offers novel insight into massless particles, antigravity, and cosmic-scale gravitational behaviour.

Supports intuitive analogues to dark energy, inertia-kinetic duality, and relativistic limits.

ECM Term Definition — Matter Mass (Mᴍ):

Matter Mass, symbolized as Mᴍ, refers to the total positive gravitational mass derived from all forms of matter, both visible and non-visible. It is defined as:

where:

Mᴏʀᴅ is the Ordinary Matter Mass, consisting of atoms, particles, and objects observable through electromagnetic interaction (e.g., stars, gas, planets, etc.).

Mᴅᴍ is the Dark Matter Mass, which cannot be directly observed but whose gravitational influence is well-documented (e.g., via galaxy rotation curves, cluster dynamics, and lensing effects).

This formulation reflects the observational evidence that approximately 27% of the universe's total energy content is attributed to matter, with ordinary matter contributing only about 5%, and dark matter making up the remaining ~22%. These proportions are consistent with studies such as:

Chernin, A. D., Bisnovatyi-Kogan, G. S., Teerikorpi, P., Valtonen, M. J., Byrd, G. G., & Merafina, M. (2013), Astronomy and Astrophysics, 553, A101.

In the ECM framework, Matter Mass forms the foundational term used in both gravitational and dynamic considerations. However, ECM does not equate Mᴍ to gravitational mass. Instead, gravitational mass is redefined as:

where −Mᵃᵖᵖ is the Apparent Mass (with a negative sign), which in ECM is equivalent to the effective mass of dark energy (Mᴅᴇ). This relationship accounts for the antigravitational behaviour observed on cosmological scales and aligns with the balance conditions observed in Chernin’s “zero-gravity spheres” at large radial distances.

Discussion

The presented formulation offers a clear and comprehensive departure from traditional Newtonian mechanics by extending foundational principles through the lens of Extended Classical Mechanics (ECM). While rooted in Newton’s force law F = ma, ECM redefines the nature and composition of mass, bringing kinetic energy and gravitational context into dynamic roles previously unaccounted for.

Newtonian Groundwork and the ECM Shift

Classical mechanics treats mass as both inertial and gravitational, implicitly assuming their equivalence and constancy. However, in ECM, this uniformity dissolves. Mass becomes a dynamic quantity—decomposed into two components:

Matter Mass (Mᴍ) representing intrinsic gravitational matter (including both ordinary and dark matter), and

Negative Apparent Mass (-Mᵃᵖᵖ), representing the mass-equivalent of kinetic energy and gravitational-field interaction.

This dual-mass framework transforms classical gravitational mass into an effective mass:

This shift allows ECM to address dynamic systems where energy exchange alters the net mass, which classical mechanics cannot account for without invoking relativistic or quantum principles.

Force and Acceleration: A Redefined Relationship

One of the striking innovations in ECM is the distinction between inertial source and accelerative response. While force remains proportional to acceleration, the inertial resistance is attributed to the effective mass, not solely the matter mass. Yet, paradoxically, acceleration remains inversely proportional to matter mass:

This distinction introduces an ECM-specific inertia principle, where the observable acceleration stems from how much real mass resists motion, while the net force includes additional dynamic components like kinetic mass or gravitational distortion.

Speed Regimes and Mass Balance

By comparing (Mᴍ) and |Mᵃᵖᵖ|, ECM introduces a robust classification of motion:

Low speeds occur when rest mass dominates,

Medium speeds at a critical balance point, and

High speeds when kinetic (apparent) mass becomes dominant.

This interpretation yields a continuous transition from rest to motion, closely linked with energy-mass dynamics. It also implies that velocity is not an isolated vector but the outcome of a shifting mass-energy balance, a nuance classical mechanics lacks.

Gravitational Radius and Cosmological Insight

The model’s capacity to account for varying gravity with radial distance (r) stands as a profound contribution. It elegantly explains:

Local gravity (r = 0) as pure mass-dominated attraction,

Intermediate distances ( r > 0) as zones of mass-kinetic interplay, and

Cosmic-scale distances (r ≫ 0) where Mᴍ ≈ |Mᵃᵖᵖ|, leading to net gravitational neutrality or repulsion.

This is not only consistent with Chernin et al.'s observations of "zero-gravity spheres" but also offers a functional explanation for dark energy as a dynamic outcome of negative apparent mass, rather than a cosmological constant or exotic field.

Massless Particle Redefinition

The treatment of massless particles under ECM is especially transformative. ECM reframes the photon not as a truly massless particle, but as one exhibiting a cancellation between negative matter mass and positive kinetic energy mass:

This leads to ECM's prediction that photons under gravitational influence experience acceleration as if propelled by their internal energy redistribution—a viewpoint supporting both relativistic speed limits and gravitational redshift mechanisms without invoking spacetime curvature directly.

Logical and Physical Coherence

The ECM framework remains dimensionally and logically consistent with Newtonian mechanics while allowing for:

Mass variation with energy and spatial context,

Force expressions consistent across massive and massless systems,

Interpretation of relativistic and cosmological behaviors using classical equations enhanced with new terms.

Implications and Broader Significance

This approach does more than reinterpret equations—it provides a unifying language for classical, relativistic, and cosmological phenomena. By internalizing the concept of apparent mass, ECM not only bridges gaps in Newtonian mechanics but also offers testable insights into:

Dark energy and cosmic expansion,

High-velocity particle behavior,

Gravitational influence at multiple scales, and

Photon dynamics within gravitational fields.

Alphabetical Glossary of Mathematical Terms in ECM

The acceleration resulting from the ECM-adjusted net mass (Mᵉᶠᶠ), it represents the physical acceleration observed when accounting for both real and apparent mass components.

The fundamental speed limit for information and energy propagation in spacetime, in ECM, it represents the upper bound for particles under gravitational escape or massless propagation.

Defined by Newton’s second law as F = ma. In ECM, this forms the foundational equation upon which force extensions are built.

The generalized ECM force expression: Fᴇᴄᴍ = Mᵉᶠᶠ aᵉᶠᶠ = (Mᴍ + (−Mᵃᵖᵖ)) aᵉᶠᶠ Accounts for both real matter mass and negative apparent mass contributions in the system's inertial behaviour.

The intensity of gravitational acceleration experienced by a mass, appears in the classical gravitational force equation (F = mɢ g).

The actual gravitational acceleration experienced by a body in ECM, defined as the net field influence resulting from both matter mass (Mᴍ) and apparent mass (−Mᵃᵖᵖ). Appears in the generalized gravitational force equation: Fɢ = Mɢ gᵉᶠᶠ = (Mᴍ + (−Mᵃᵖᵖ)) gᵉᶠᶠ. Unlike classical (g), which is static, gᵉᶠᶠ dynamically changes with spatial context (radial distance), mass-energy redistribution, and the local gravitational environment is — especially reflecting transitions between gravity-dominated and antigravity dominated regions.

Total positive gravitational mass composed of ordinary matter (Mᴏʀᴅ) and dark matter (Mᴅᴍ). It is the primary rest-mass term in ECM.

Mass made of observable matter (atoms, particles, objects emitting or interacting with EM radiation) Subset of Mᴍ.

Non-luminous, indirectly observed mass inferred from gravitational effects, also a component of Mᴍ.

A dynamic mass component arising from kinetic energy or gravitational interaction, in ECM, it is negative and represents the inertial contribution from energy motion, not substance.

Defined as the net inertial mass in ECM: Mᵉᶠᶠ = Mᴍ + (-Mᵃᵖᵖ)

Determines how body resists acceleration, incorporating both positive matter mass and negative apparent mass.

In ECM, redefined from its classical form to: Mɢ = Mᴍ + (-Mᵃᵖᵖ) = Mᵉᶠᶠ. This formulation allows mass to evolve based on energy redistribution and gravitational conditions.

The spatial separation from a central gravitational source, in ECM, the different values of (r) change the relative dominance of Mᴍ and Mᵃᵖᵖ, leading to shifts between gravity and antigravity behaviour.

The speed of a particle, determined in ECM as a function of apparent mass and acceleration, for massless particles under gravity: Fᴇᴄᴍ = 2|Mᵃᵖᵖ| aᵉᶠᶠ ⇒ v = c

Conclusion

The formulation of Extended Classical Mechanics (ECM) equations from classical foundations provides a coherent and innovative extension of Newtonian mechanics, bridging conventional limitations through the introduction of effective mass and negative apparent mass. By redefining gravitational and inertial interactions, ECM offers a refined understanding of force, acceleration, and mass behaviour across both massive and massless regimes. It maintains classical proportionality principles while enhancing interpretative power for relativistic and cosmological phenomena—such as high-speed particle dynamics and the transition from gravitational to antigravitational domains. ECM's consistent treatment of mass-energy coupling, particularly through its reinterpretation of photons and gravitational thresholds, introduces a unifying framework applicable to both local and large-scale dynamics. This advancement aligns with empirical research, notably Chernin et al.'s observations of cosmic structures, and sets a robust groundwork for further theoretical and experimental exploration.

Funding

No financial aid is received for this work.

Conflicts of Interest

Author declares no conflict of Interest.

References

- Chernin, A. D., Bisnovatyi-Kogan, G. S., Teerikorpi, P., Valtonen, M. J., Byrd, G. G., & Merafina, M. (2013). Dark energy and the structure of the Coma cluster of galaxies. Astronomy and Astrophysics, 553, A101. [CrossRef]

- Goldstein, H., & Twersky, V. (n.d.). Classical Mechanics. Physics Today, 5(9), 19–20. [CrossRef]

- Famaey, B., & Durakovic, A. (2025). Modified Newtonian Dynamics (MOND). arXiv (Cornell University). [CrossRef]

- Thakur, S. N. (2024). Extended Classical Mechanics: Vol-1 - Equivalence Principle, Mass and Gravitational Dynamics. Preprints. [CrossRef]

- Thakur, S. N., & Bhattacharjee, D. (2023a). Phase Shift and Infinitesimal Wave Energy Loss Equations. preprints.org (MDPI). [CrossRef]

- The Large Scale Structure of Space-Time by Stephen Hawking and eorge Ellis.

- Dark Matter and the Dinosaurs: The Astounding Interconnectedness of the Universe" by Lisa Randall.

- Cosmology by Steven Weinberg.

- The Quantum Theory of Fields by Steven Weinberg.

|

Disclaimer/Publisher’s Note: The statements, opinions and data contained in all publications are solely those of the individual author(s) and contributor(s) and not of MDPI and/or the editor(s). MDPI and/or the editor(s) disclaim responsibility for any injury to people or property resulting from any ideas, methods, instructions or products referred to in the content. |

© 2025 by the authors. Licensee MDPI, Basel, Switzerland. This article is an open access article distributed under the terms and conditions of the Creative Commons Attribution (CC BY) license (http://creativecommons.org/licenses/by/4.0/).