1. Introduction

The advancement of biotechnology has brought major changes to the ways enzymes are produced and characterized, especially those with industrial potential [

1]. Among these, collagenolytic proteases have stood out for their ability to break down collagen, the main structural protein found in animal connective tissues. By cleaving specific peptide bonds, these enzymes produce bioactive peptides that can be used in several areas. In the biomedical and cosmetic industries, they are important for wound-healing treatments and skincare products. In the food industry, they help improve the nutritional and functional properties of foods, tenderize meat, produce peptides with antioxidant and antimicrobial properties, and add value to by-products from meat and poultry processing. In agriculture, they can also play a role by contributing to bioconversion processes and residue valorization [

2,

3].

Microbial collagenases are particularly valued for their specificity in targeting the triple-helical structure of collagen, making them highly effective in the production of bioactive peptides and in facilitating tissue remodeling. In this context, the fungus

Mucor subtilissimus has emerged as a promising source of collagenolytic proteases, showing significant potential for industrial applications and notable versatility in enzyme production under different fermentation conditions [

4]. A deeper understanding of the properties and behavior of these enzymes is crucial for developing efficient strategies aimed at their application in various biotechnological processes.

Understanding the thermodynamic properties of enzymes is key to unlocking their full potential in industrial and biotechnological applications. By analyzing parameters such as Gibbs free energy, enthalpy, and entropy, it becomes possible to gain valuable insights into the enzyme’s stability, activity profile, and behavior under different environmental conditions [

5]. For collagenolytic proteases, thermodynamic analysis helps determine how resistant the enzyme is to temperature variations, which is crucial for optimizing its use in processes like food production, waste valorization, and the development of bioactive compounds [

6]. Therefore, the present study aims to partially characterize the collagenolytic protease from

Mucor subtilissimus UCP 1262, focusing on its thermodynamic properties and potential applications.

2. Materials and Methods

2.1. Production and Purification of Collagenolytic Protease from Mucor subtilissimus UCP 1262 Fermentation

The collagenolytic protease studied was generated and isolated following the procedure described by Nascimento

et al. [

4]. The production phase was conducted via solid-state fermentation using

Mucor subtilissimus UCP 1262 on wheat bran substrate. Subsequently, purification was performed through DEAE-Sephadex A50 ion-exchange chromatography in a glass column that had been pre-equilibrated with 125 mM sodium phosphate buffer at pH 7.0, according to Cardoso

et al. [

7].

2.2. Protein Assay and Enzymatic Activities

Protein concentration was determined according to the method of Smith et al. [

8], using bovine serum albumin as the standard protein. The method for determining protease activity was modified from Ginther [

9] using azocasein (1%) as substrate, the absorbance was measured at 420 nm using a spectrophotometer, and the calculation was performed considering 1 unit of enzymatic activity (U) as an absorbance change of 0.1 in one hour.

Collagenase activity was assessed following the protocol outlined by Chavira [

10] using azocoll (5 mg/L) as substrate, one unit of enzymatic activity (U) was defined as the amount of enzyme per mL of sample that, after 60 minutes of incubation, resulted in an increase of 0.001 in absorbance at λ550 nm. Specific activity was calculated as the ratio of enzymatic activity to the total protein content of the sample, expressed in U/mg.

2.3. Effect of Temperature and pH on Collagenase Activity

The effect of pH on protease activity was evaluated by mixing the enzyme solution with the specific substrate, prepared in 0.05 M buffer solutions at different pH values: sodium citrate (pH 5, 6, 7) and Tris-HCl (pH 7, 8, and 9). The effect of temperature was determined using a reaction mixture containing the specific substrate and enzyme solution, incubated at various temperatures (20 °C, 30 °C, 40 °C, 50 °C, 60 °C, and 70 °C) for 60 minutes, and proteolytic activity of both temperature and pH tests was determined following the same methodology described previously.

2.4. Thermodynamics of Protease Thermal Inactivation

The thermal stability of the protease was investigated at temperatures of 10, 30, and 60 °C. The enzyme was incubated for up to 120 minutes without the presence of substrate. Samples were collected at various time points, and the initial (A₀) and final (A) activities were determined as described in section 2.2.

The experimental data were used to calculate the decay constants (kₑ) for each temperature. The lines were determined by plotting a graph of ln(A/A₀) versus time. The kₑ values were used to determine the deactivation energy (Eₑ) using the linearized Arrhenius equation:

The thermodynamic parameters for protease denaturation, such as enthalpy (ΔH*), Gibbs free energy (ΔG*), and entropy (ΔS*), were calculated using the following equations at temperatures of 10, 30, and 60 °C:

where h is Planck's constant (6.626 × 10⁻³⁴ J·s) and k_B is Boltzmann's constant (1.381 × 10⁻²³ J K⁻¹).

Other important parameters for denaturation, such as the half-life (t₁/₂) and the decimal reduction time (D-value), which are defined as the times after which enzymatic activity is reduced to half and one-tenth of the initial value, respectively, at a given temperature, were determined according to the respective equations:

2.5. Collagen Peptide Production

The evaluation of the protease's affinity for cleaving different types of collagen was performed according to Chavira [

10], with modifications. A total of 5 mg of Type I and Type V collagen were used in 950 µL of 0.1 M TRIS-HCl buffer at pH 8, along with 50 µL of the sample. The reaction occurred for 1 hour under agitation at 37 °C, followed by incubation of the entire contents at 100 °C for 3 minutes and then centrifugation for 15 minutes at 4000 rpm. The performance of the activity was monitored using a UV-VIS spectrophotometer (UV-1900i Shimadzu, Barueri, Brazil) in the range of 500 to 190 nm.

2.6. Statistical Analysis

Statistical evaluations were performed using the standard deviation from triplicate experiments. The data were examined through one-way analysis of variance (ANOVA) or the Kruskal-Wallis test employing the open-source software RStudio (version 2023.12.1+402). The significance levels were determined using Tukey's test or Dunn's test based on multiple post-hoc comparisons, with a significance threshold set at p < 0.05.

3. Results

3.1. Enzymatic Activities

The enzyme produced and purified using the described methodology exhibited a proteolytic activity of 98 U/mL and a collagenolytic activity of 41.70 U/mL. These results demonstrate a significant capacity for protein and collagen degradation, indicating the efficiency of the production and purification processes employed.

3.2. Partial Biochemical Characterization

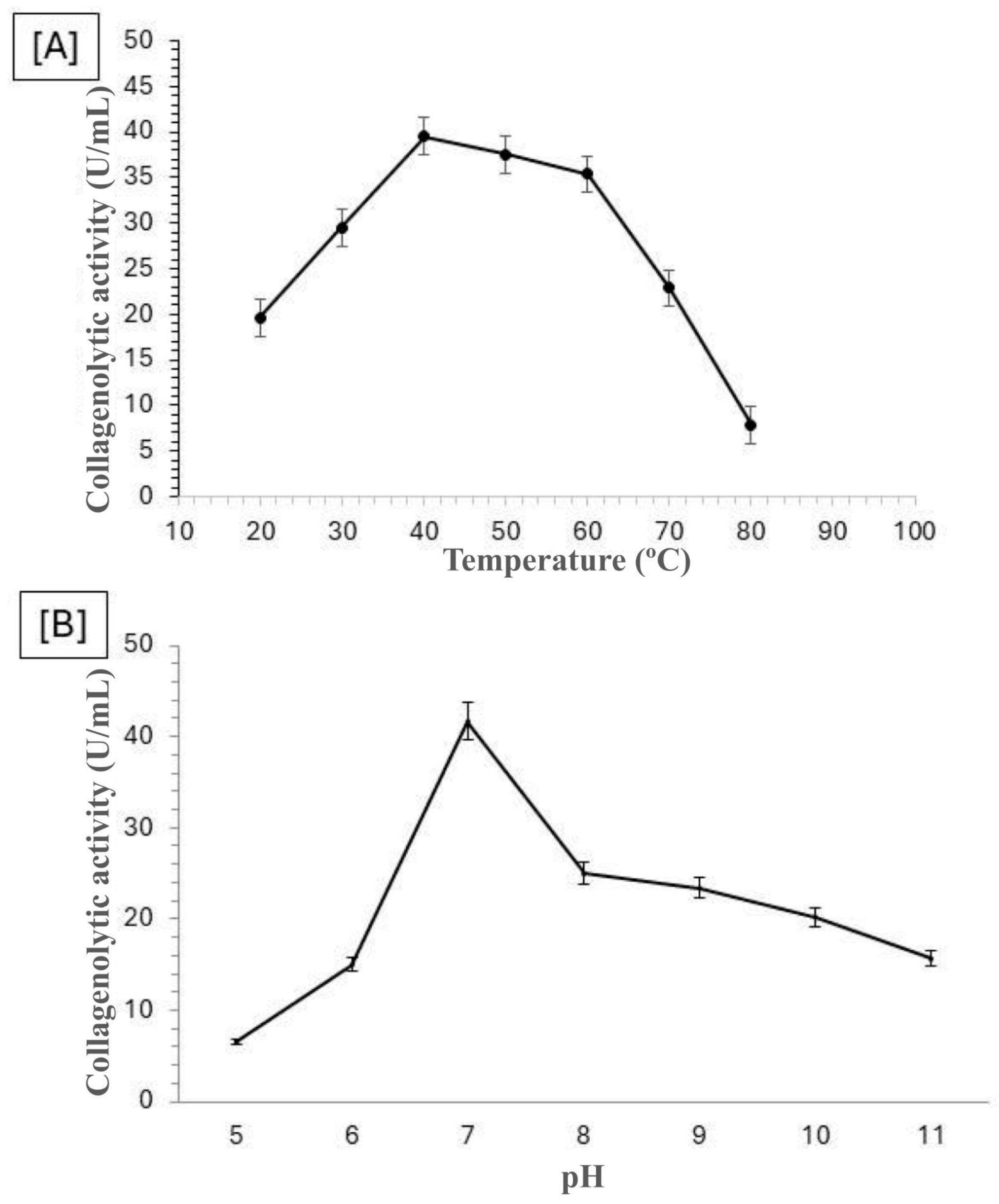

The partial characterization of the collagenolytic protease from

Mucor subtilissimus UCP 1262 revealed that its enzymatic activity is optimized at a temperature of 40 °C and at a neutral pH (pH 7), as shown in

Figure 1.

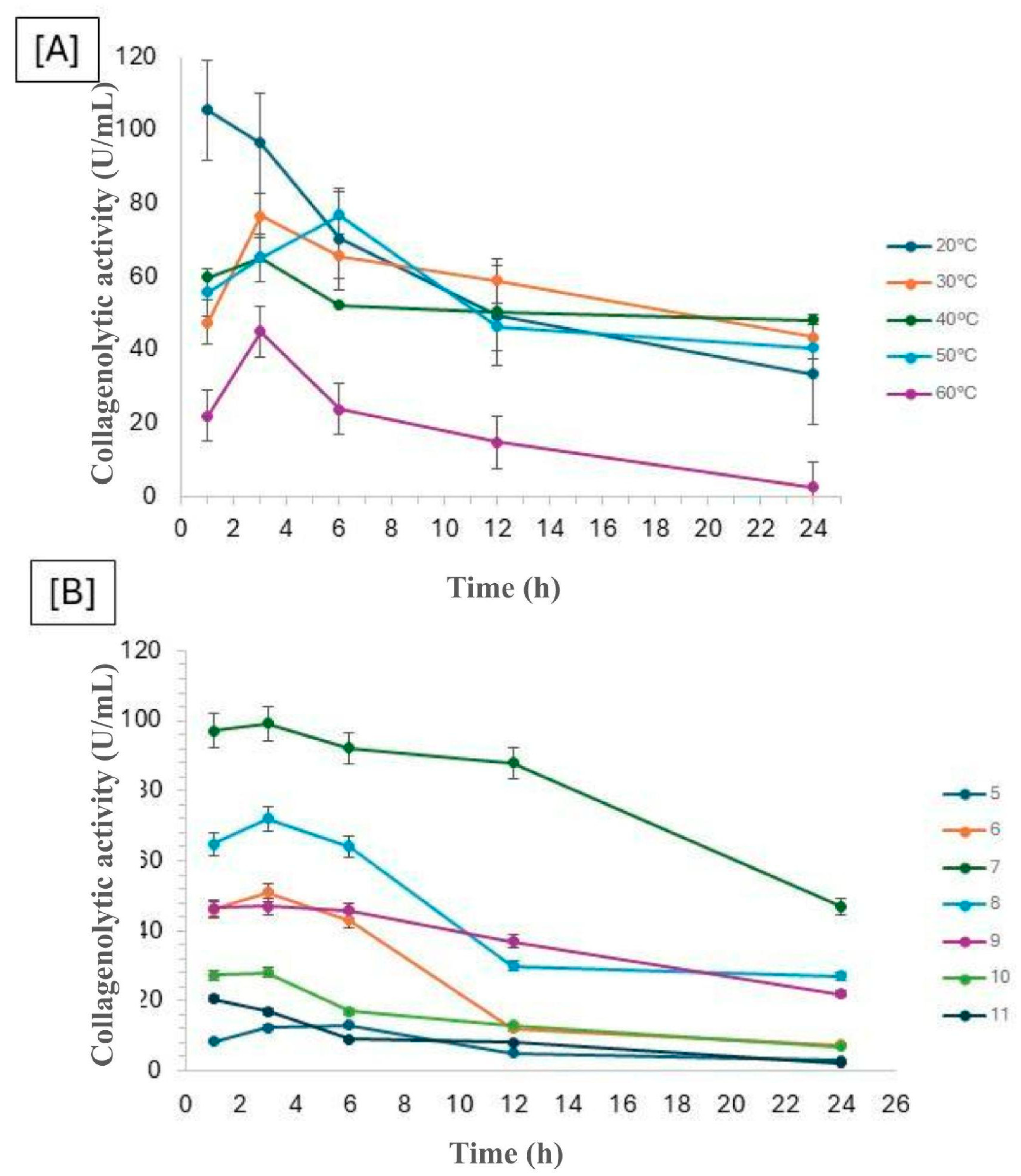

The stability of fungal collagenase concerning pH and temperature is crucial for its application across various industries. The collagenolytic protease from

Mucor subtilissimus UCP 1262 was evaluated under different temperatures and pH levels, and the results are presented in

Figure 2. It was observed that, after 6 hours, all enzymatic activities at different temperatures began to decline, indicating the enzyme's sensitivity to exposure time. Although the temperature of 20°C initially exhibited superior performance, its activity rapidly decreased, whereas the temperatures of 30°C and 40°C maintained activity at approximately 50% for up to 24 hours. These results suggest that, although the initial activity at 20°C was promising, the enzyme's stability at higher temperatures is advantageous for industrial applications. Regarding pH, the value of 7 stood out, as it maintained enzymatic activity close to the original for 12 hours, demonstrating good stability, with activity only declining to half after 24 hours.

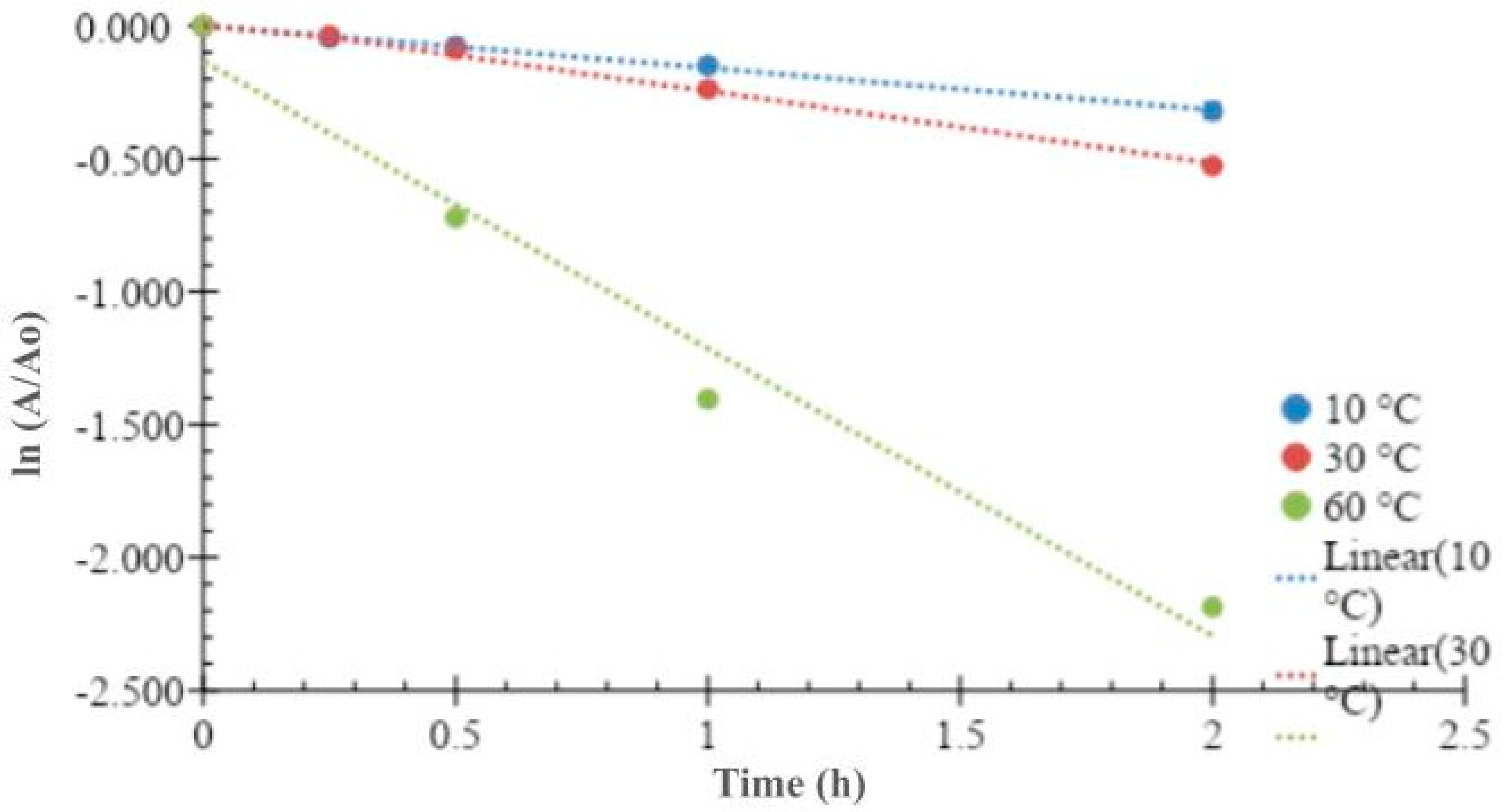

3.3. Thermodynamics of Thermal Inactivation of the Protease

The thermal inactivation parameters of the collagenolytic protease from Mucor subtilissimus UCP 1262 were estimated at temperatures of 10, 30, and 60 °C, demonstrating high linearity (

Figure 3).

The values of kd decreased (

Table 1) with increasing temperature, indicating that non-covalent bonds were more affected due to increased agitation/vibration of the atoms. From these results, a deactivation energy of 31.9 kJ/mol was obtained.

Table 1 presents the Gibbs free energy values, which increased with rising temperature, suggesting greater stability.

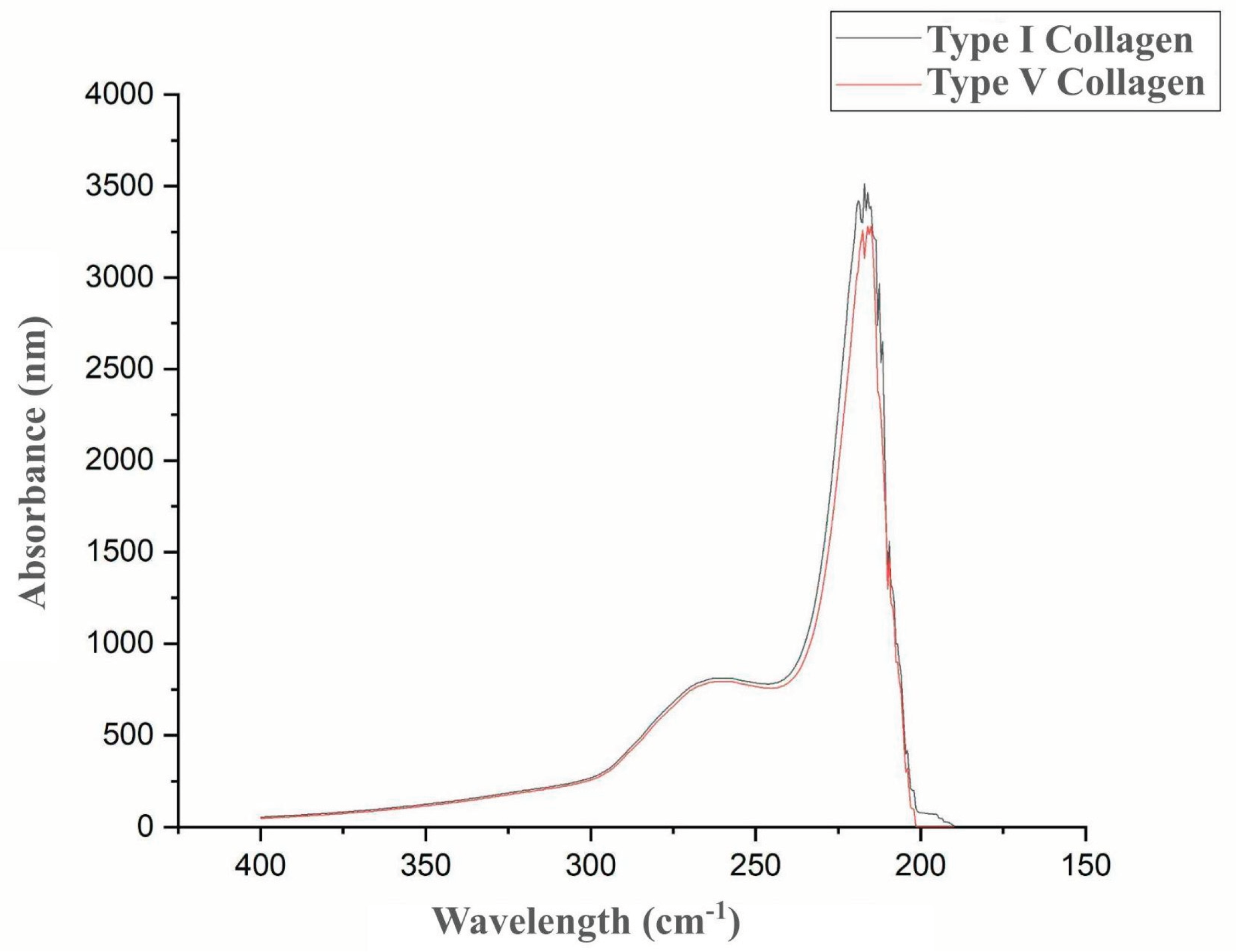

3.4. Collagen Degradation

The collagenolytic protease from

Mucor subtilissimus UCP 1262 was evaluated for its ability to degrade collagen types I and V.

Figure 4 presents the results of the degradation of both collagen types by the enzyme. The protease demonstrated activity on both substrates, confirming its collagenolytic capacity, with a slight preference for type I collagen.

4. Discussion

4.1. Enzymatic Activities

The results obtained, as demonstrated above, indicate the efficiency of the production and purification processes employed. The production of collagenase by

Mucor subtilissimus UCP 1262 has been previously analyzed. Nascimento

et al. [

4] reported collagenolytic activity of 161.4 U/mL, along with proteolytic (102.9 U/mL), fibrinolytic (26.1 U/mL), keratinase (39.6 U/mL), and amidolytic (10.28 U/mL) activities. Souza

et al. [

11], on the other hand, optimized the production process of collagenolytic proteases by the same microorganism, achieving up to 179.81 U/mL. This difference may be attributed to variations in fermentation and purification conditions, underscoring the importance of continuous optimization of protocols to maximize enzymatic activity and the industrial viability of the enzyme. Nevertheless, it is evident that

M. subtilissimus demonstrates a capacity for producing collagenolytic protease.

4.2. Partial Biochemical Characterization

The parameters obtained regarding optimal pH and temperature are consistent with previous studies that evaluated the influence of pH and temperature on proteases from filamentous microorganisms, as described by Nascimento

et al. [

4]. In Nascimento's study, a fibrinolytic protease from

M. subtilissimus UCP 1262 was tested across various temperature ranges (10 to 90 °C) and pH values (3 to 11), revealing an enzymatic profile similar to our study. However, it is noteworthy that, to date, no study has specifically focused on the characterization of a collagenolytic protease produced by

M. subtilissimus.

The finding that the enzyme is most active at 40°C and pH 7 is particularly relevant. The optimal temperature near body temperature suggests that the enzyme could be useful in biomedical applications, such as wound treatment or tissue regeneration, where collagen degradation can be beneficial for healing processes [

12]. Additionally, the neutral pH conditions expand the possibilities for using the enzyme in food systems, particularly in dairy products and meat processing, where maintaining a stable pH environment is essential for preserving the sensory and nutritional properties of the products [

13]. Similarly, Da Silva

et al. [

14] characterized collagenase from

Aspergillus tamarii obtaining an optimal temperature of 40°C; Danial

et al. [

15] emphasized that optimal activities in this range are crucial for maintaining effectiveness during processing. This initial characterization opens avenues for more detailed studies on enzymatic kinetics and the potential optimization of its large-scale production, facilitating the development of applications in various industrial sectors, such as pharmaceuticals, cosmetics, and food.

Regarding the stability of fungal collagenase in relation to pH and temperature, the literature presents findings that both diverge from and align with the results obtained in this study. For instance, the collagenase from

Streptomyces antibioticus exhibits stability over a broader pH range (6.0–11.0) and at temperatures between 30–55°C [

16], differing from our observations. On the other hand, a collagenolytic protease from Bacillus subtilis demonstrates optimal activity at pH 7.5, indicating a preference for neutral conditions [

17], which is consistent with our findings.

4.3. Thermodynamics of Thermal Inactivation of the Protease

As demonstrated the Gibbs free energy values increased with rising temperature. This parameter is related to the amount of energy still present in the molecule [

18]. These data corroborate the entropy values, where the negative values indicate that within the studied temperature range, the protease underwent reversible denaturation, and the irreversible denaturation process occurs at high temperatures [

19]. The enthalpy values showed slight variation; however, considering that the energy required to break a non-covalent bond is 5.4 J/mol, approximately five bonds were broken [

20]. The half-life and decimal reduction time values decreased with increasing temperature. It is important to highlight that at 60 °C, the protease requires approximately 2 hours to reduce its initial activity to 10%. These findings suggest that the protease produced by

Mucor subtilissimus UCP 1262 exhibits moderate thermal stability, making it a suitable candidate for applications that require enzyme functionality at mild to moderate temperatures [

5].

These results are comparable to those reported by da Da Silva

et al. [

14] for a purified protease from Aspergillus tamarii URM4634, which exhibited a denaturation energy (Ed) of 28.8 kJ/mol, enthalpy of 26.1 kJ/mol, entropy of −203.1 J/molK, and Gibbs free energy values ranging from 91.8 to 98.0 kJ/mol. In contrast, the protease from Aspergillus heteromorphus reported by Fernandes

et al. [

19] showed different values from those found in this study, with a denaturation energy (Ed) of 8.05 kJ/mol, enthalpy values between 5.36 and 5.69 kJ/mol, entropy ranging from −274.89 to −276.96 J/molK, and Gibbs free energy values between 83.85 and 94.19 kJ/mol. These differences in thermodynamic parameters can largely be attributed to structural variations between the proteases, such as differences in amino acid composition, the presence of intramolecular interactions (e.g., hydrogen bonds and hydrophobic interactions), and the three-dimensional organization of the enzymes, which directly influence their thermal stability and the energy required for denaturation [

18]. The moderate enthalpy changes and relatively high Gibbs free energy values indicate that the enzyme maintains significant structural integrity under stress, a feature that is often associated with the presence of stabilizing intramolecular interactions [

21].

4.4. Collagen Degradation

The ability of the collagenase to degrade type 1 and type 5 collagen, with a slight advantage for type I collagen can be attributed to the more organized and fibrillar structure of type I collagen, which facilitates the protease's access to cleavage sites. Conversely, type V collagen, being less abundant and structurally distinct, exhibited greater resistance to degradation, corroborating previous studies that suggest that smaller or less fibrillar collagens may be less susceptible to proteolytic action [

22]. The enzyme's activity on both collagen types highlights its potential for biomedical applications, as the ability to degrade multiple types of collagen opens the possibility for utilizing this enzyme in procedures that require tissue remodeling with varying collagen compositions, such as in complex wound healing or treatments for fibrotic diseases [

23].

These data provide a promising basis for future applications of the protease from Mucor subtilissimus, suggesting that its comprehensive characterization, along with the optimization of conditions to maximize the degradation of various types of collagen, could expand its utility in biotechnology and regenerative medicine.

5. Conclusions

The partial characterization of the collagenolytic protease from Mucor subtilissimus UCP 1262 demonstrated its potential for biomedical and industrial applications, with optimized activity at 40°C and neutral pH. The results confirm the enzyme's ability to efficiently degrade collagen, highlighting its promising use in wound healing processes and the food industry. Continued studies on the optimization and practical application of these proteases could significantly contribute to innovations in biotechnology and sustainability, broadening their usage possibilities across various industries.

Author Contributions

Conceptualization, Kethylen Barbara Barbosa Cardoso anf Kétura Rhammá Cavalcante; methodology, Kethylen Barbara Barbosa Cardoso, Kétura Rhammá Cavalcante, and Jonatas de Carvalho Silva; software, Jonatas de Carvalho Silva; validation, Kethylen Barbara Barbosa Cardoso, Kétura Rhammá Cavalcante, and Luiz Henrique Svintiskas Lino; formal analysis, Kethylen Barbara Barbosa Cardoso; investigation, Kethylen Barbara Barbosa Cardoso; resources, Kethylen Barbara Barbosa Cardoso and Raphael Luiz Andrade Silva; data curation, Anna Gabrielly Duarte Neves; writing—original draft preparation, Kethylen Barbara Barbosa Cardoso, Daniela de Araújo Viana Marques and Maria Eduarda Luiz Coelho de Miranda; writing—review and editing, Kethylen Barbara Barbosa Cardoso and Maria Eduarda Luiz Coelho de Miranda; visualization, Raphael Luiz Andrade Silva; supervision, Daniela de Araújo Viana Marques; project administration, Romero M P Brandão-Costa; funding acquisition, Romero M P Brandão-Costa, Ana Lucia Figueiredo Porto, and Thiago Pajeú Nascimento.

Funding

This work was supported by the Pernambuco Science and Technology Support Foundation (FACEPE) (IBPG-1491-2.08/19), the National Council for Scientific and Technological Development (CNPq) (88887.668849/2022-00), the Foundation for Science and Technology (FCT) under the strategic funding of the unit UIDB/04469/2020, by LABBELS—Associated Laboratory in Biotechnology, Bioengineering, and Microelectromechanical Systems (LA/P/0029/2020), by the Marie Skłodowska-Curie (MSCA-RISE; FODIAC; 778388) program, and by the European Regional Development Fund (ERDF) through the Operational Programme for Competitiveness Factors—North 2020, COMPETE.

Data Availability Statement

The original contributions presented in this study are included in the article; further inquiries can be directed to the corresponding author.

Acknowledgments

We thank FACEPE and CAPES for their financial support.

Conflicts of Interest

The authors declare no conflicts of interest.

References

- Puntambekar, A.; Dake, M. Microbial Proteases: Potential Tools for Industrial Applications. Res. J. Biotechnol. 2023, 18, 159–171. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Nicholson, P.J. Enzymes: New Uses for Old Hazards. Occup. Med. 2022, 72, 351–353. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Jabalia, N.; Mishra, P.C.; Chaudhary, N. Applications, Challenges and Future Prospects of Proteases: An Overview. J. Agroecol. Nat. Resour. Manag. 2014, 1, 179–183. [Google Scholar]

- Nascimento, T.P.; et al. Protease from Mucor subtilissimus UCP 1262: Evaluation of Several Specific Protease Activities and Purification of a Fibrinolytic Enzyme. An. Acad. Bras. Ciênc. 2020, 92, e20200882. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Salehi, M. Evaluating the industrial potential of naturally occurring proteases: A focus on kinetic and thermodynamic parameters. International Journal of Biological Macromolecules 2024;254:127782. [CrossRef]

- Rigoldi, F.; Donini, S.; Redaelli, A.; Parisini, E.; Gautieri, A. Review: Engineering of Thermostable Enzymes for Industrial Applications. 2018, 2, 011501. [CrossRef]

- Cardoso, K.B.B.; et al. Role of Gamma Radiation as an Agent Modulator of Mucor subtilissimus UCP1262 Fibrinolytic Enzyme (MsFE). Process Biochem. 2024, 143, 13–22. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Smith, P.K.; et al. Measurement of Protein Using Bicinchoninic Acid. Anal. Biochem. 1985, 150, 76–85, Erratum in: Anal. Biochem. 1987, 163, 279. PMID: 3843705. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Ginther, C.L. Sporulation and the Production of Serine Protease and Cephamycin C by Streptomyces lactamdurans. Antimicrob. Agents Chemother. 1979, 15, 522–526. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Chavira, R.; Burnett, T.J.; Hageman, J.H. Assaying Proteinases with Azocoll. Anal. Biochem. 1984, 136, 446–450. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Souza, K.P.S.; et al. A Novel Collagenolytic Protease from Mucor subtilissimus UCP 1262: Comparative Analysis of Production and Extraction in Submerged and Stated-Solid Fermentation. An. Acad. Bras. Ciênc. 2022, 94, e20201438. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Ramachandregowda, S.; et al. Collagen as the Extracellular Matrix Biomaterials in the Arena of Medical Sciences. Tissue Cell 2024, 90, 102497. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Khvostov, D.V.; Khryachkova, A.Yu.; Minaev, M.Yu. The Role of Enzymes in the Formation of Meat and Meat Products. Theory Pract. Meat Process. 2024, 9, 40–52. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Da Silva, O.S.; et al. Purification and Characterization of a Novel Extracellular Serine-Protease with Collagenolytic Activity from Aspergillus tamarii URM4634. Int. J. Biol. Macromol. 2018, 117, 1081–1088. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Danial, S.; et al. Production and Characterization of Collagenase from Bacillus sp. 6-2 Isolated from Fish Liquid Waste. J. Akta Kim. Indones. (Indones. Chim. Acta) 2019, 58–66.

- Costa, E.P.; et al. Extracellular Collagenase Isolated from Streptomyces antibioticus UFPEDA 3421: Purification and Biochemical Characterization. Prep. Biochem. Biotechnol. 2024, 54, 260–271. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Bhuimbar, M.V.; et al. Purification, Characterization and Application of Collagenolytic Protease from Bacillus subtilis Strain MPK. J. Biosci. Bioeng. 2024, 138, 21–28. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- De Carvalho Silva, J.; et al. Kinetic and Thermodynamic Characterization of a Novel Aspergillus aculeatus URM4953 Polygalacturonase. Comparison of Free and Calcium Alginate-Immobilized Enzyme. Process Biochem. 2018, 74, 61–70. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Fernandes, L.M.G.; et al. Purification and Characterization of a Novel Aspergillus heteromorphus URM 0269 Protease Extracted by Aqueous Two-Phase Systems PEG/Citrate. J. Mol. Liq. 2020, 317, 113957. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Fernandes, L.M.G.; et al. Valorization of Agro-Industrial Residues Using Aspergillus heteromorphus URM0269 for Protease Production: Characterization and Purification. Int. J. Biol. Macromol. 2024, 133199. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Chisti, Y. Chemical Stabilization of Enzymes. In; Academic Press, 2021; pp. 77–132.

- Perumal, S.; Antipova, O.; Orgel, J.P. Collagen Fibril Architecture, Domain Organization, and Triple-Helical Conformation Govern Its Proteolysis. Proc. Natl. Acad. Sci. USA 2008, 105, 2824–2829. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Cuoghi, S.; et al. Challenges of Enzyme Therapy: Why Two Players Are Better Than One. Wiley Interdiscip. Rev. Nanomed. Nanobiotechnol. 2024, 16, e1979. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

|

Disclaimer/Publisher’s Note: The statements, opinions and data contained in all publications are solely those of the individual author(s) and contributor(s) and not of MDPI and/or the editor(s). MDPI and/or the editor(s) disclaim responsibility for any injury to people or property resulting from any ideas, methods, instructions or products referred to in the content. |

© 2025 by the authors. Licensee MDPI, Basel, Switzerland. This article is an open access article distributed under the terms and conditions of the Creative Commons Attribution (CC BY) license (http://creativecommons.org/licenses/by/4.0/).