1. Introduction

With the increasing demand for efficient and sustainable energy storage systems, supercapacitors have emerged as promising candidates due to their high-power density, long cycle life, and rapid charge–discharge characteristics [

1,

2]. Among various components, the performance of supercapacitors is critically influenced by the nature of the electrode materials. Recent advancements in materials science have focused on developing hybrid and nanostructured materials that combine electric double-layer capacitance with pseudocapacitive behavior to enhance both energy and power densities [

3,

4].

Polyaniline (PANI) is among the leading conductive polymers used in supercapacitors, owing to its high specific capacitance, good conductivity and facile synthesis [

5]. Its main drawbacks—poor mechanical stability and limited cycle life—are largely overcome by forming composites with various nanomaterials [

6]. Metal oxides, especially ruthenium oxide (RuO₂) [

7], stand out for their exceptional pseudocapacitive activity and are often incorporated into electrode formulations. Despite its excellent conductivity, RuO₂ is expensive, which limits its practical use. This has driven research toward more affordable alternatives, such as MnO₂ [

8], NiO [

9], Fe₂O₃ [

10], CuO [

11] and ZnO [

12]. These oxides provide active centers for redox processes and, when combined with PANI, exhibit enhanced electrochemical stability and capacitance. For example, the PANI/MnO₂ composite achieves a capacitance significantly higher than that of pure PANI and retains 86.3 % of its capacitance after 1000 cycles [

13]. Similar improvements are seen in composites with graphite and carbon nanotubes, where energy densities up to 318 Wh kg⁻¹ and power densities of 12.5 kW kg⁻¹ have been reported [

14]. It is important to note that the overall pseudocapacitance of these hybrids is not simply the sum of individual components: for instance, sharp redox peaks of MoO₃ diminish when composited with PANI, indicating interfacial interactions that require further study [

15].

This demonstrates that efforts should focus on optimizing composite architecture, employing more accessible materials, and developing novel PANI-based electrodes with improved stability, capacitance and applicability in real-world devices.

In parallel with the drive to improve the electrochemical performance of PANI-based composites and the development of highly efficient energy storage systems, there is a growing need to effectively deal with industrial environmental waste, particularly in sectors such as mining and mineral processing. Flotation wastewater, generated during the beneficiation of copper-porphyry ores, contains a complex mixture of heavy metal ions (Cu²⁺, Ni²⁺, Zn²⁺, Fe³⁺), sulfate ions, and organic flotation reagents including xanthates, (e.g., potassium ethyl xanthate – C₂H₅OCS₂K), oil (20 g/t ore), frothers (e.g., methyl isobutyl carbinol), and depressants (e.g., CaO (500–1000 g/t ore)). The molybdenum flotation process further contributes compounds such as H₂SO₄, NaHS, and kerosene.Such effluents pose serious environmental threats due to their toxicity and persistence in ecosystems [

16,

17,

18].

Xanthates, though widely used in mineral flotation for their efficiency, are highly toxic and pose significant environmental risks, especially in Arctic regions. Even at low concentrations (below 1 mg/L,), they harm aquatic life (microorganisms like algae and bacteria) and contribute to heavy metal bioaccumulation, potentially impacting human health through the food chain (by facilitating the bioaccumulation of heavy metals in fish). They also degrade into hazardous compounds like carbon disulfide (CS₂). With global xanthate use expected to reach 372 million tons by 2025—and only half consumed in the process—there is an urgent need for more sustainable, effective and reusable removal methods. While destructive (e.g., oxidation) and adsorptive (e.g., zeolites) treatments exist, most are single-use and generate waste. Reusable and scalable options, especially for cold climates, remain limited [

19,

20,

21,

22,

23,

24,

25,

26,

27,

28,

29,

30,

31,

32,

33,

34,

35,

36,

37,

38,

39,

40,

41,

42,

43].

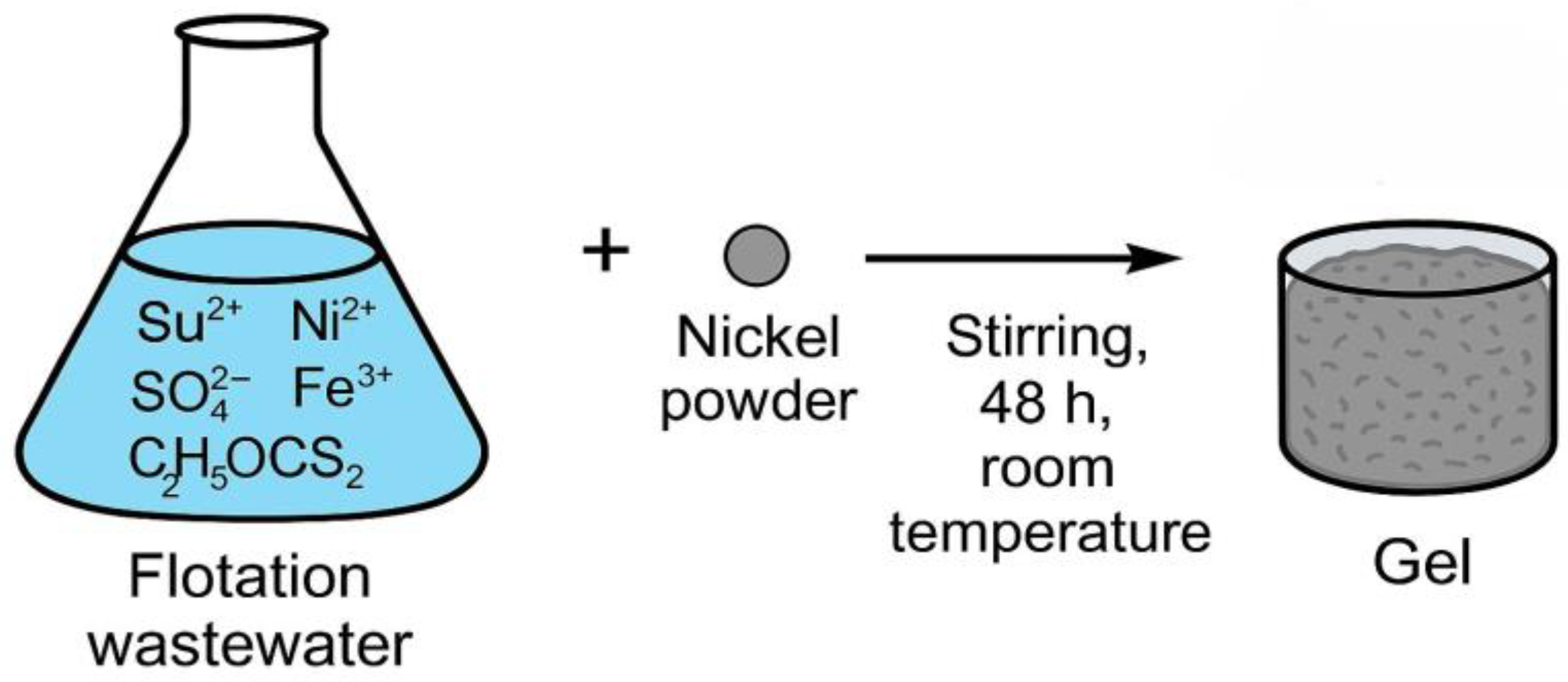

In this context, the present study introduces a novel dual-purpose strategy that not only mitigates the environmental impact of flotation wastewater but also utilizes its constituents for the fabrication of functional materials. Specifically, we report the synthesis of a metal-xanthate gel directly from copper flotation wastewater, using nickel powder as the sacrificial material. This process promotes the formation of a composite gel incorporating metal hydroxides and xanthate-metal complexes, facilitated by the spontaneous redox reactions [

44].

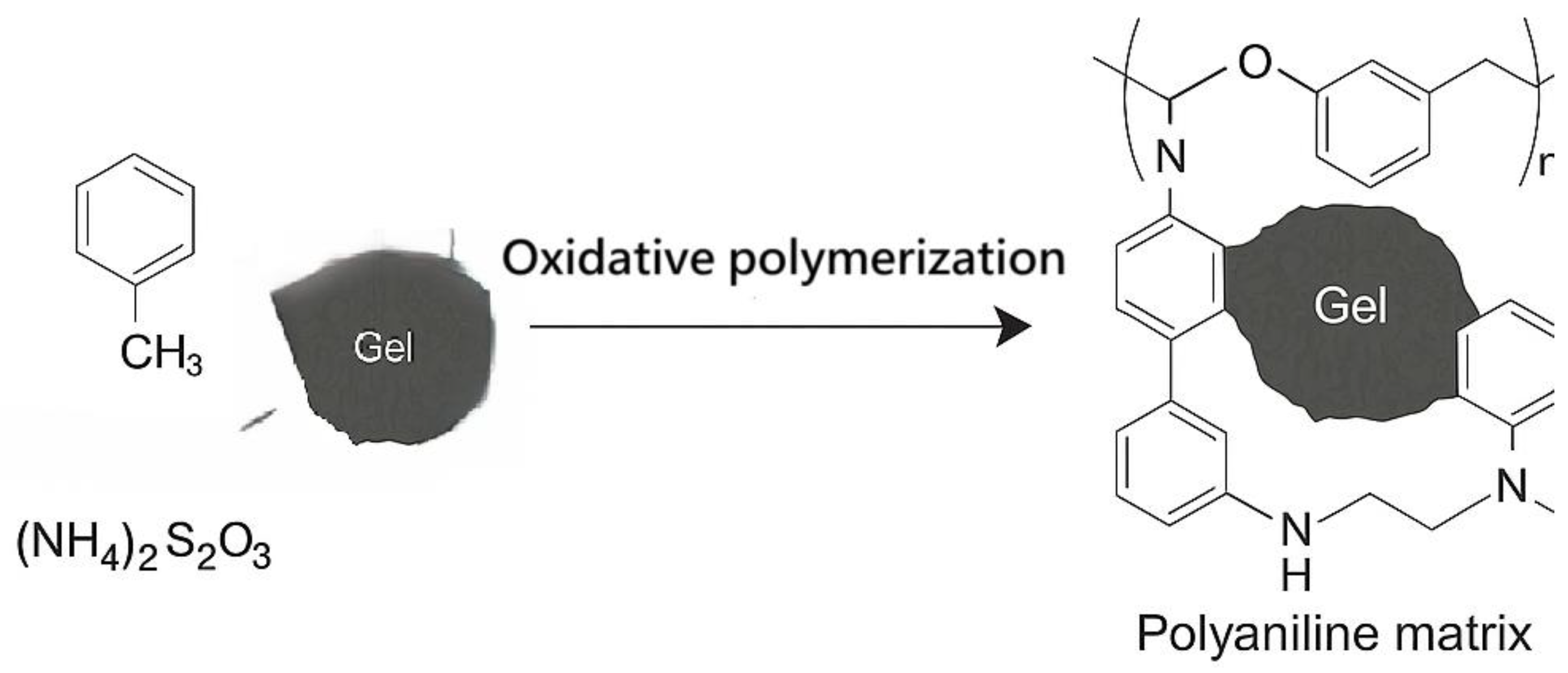

The resulting gel was incorporated into a polyaniline (PANI) matrix through oxidative polymerization, forming a nanocomposite with both Faradaic and capacitive charge storage capabilities. Polyaniline has been widely studied for supercapacitor applications due to its high theoretical capacitance, environmental stability, and cost-effective synthesis [

45,

46]. The integration of metal-xanthate complexes into the conductive PANI network was found to significantly enhance the electrochemical properties, yielding a material suitable for use as the cathodic electrode in asymmetric supercapacitor configurations.

Asymmetric supercapacitors, which combine a pseudocapacitive electrode with a capacitive counterpart, offer a broader voltage window and higher energy density than symmetric counterparts [

47]. In our study, the synthesized nanocomposite was paired with a YP-50F activated carbon electrode, and the assembled device demonstrated outstanding specific capacitance, energy density, and cycling stability.

This work bridges the domains of wastewater valorization and advanced energy storage, offering a circular economy approach that transforms hazardous industrial byproducts into value-added functional materials. To our knowledge, this is the first report detailing the direct utilization of flotation wastewater for the fabrication of supercapacitor electrode materials, presenting a scalable and environmentally relevant innovation for sustainable energy technologies.

2. Results and Discussion

2.1. Physicochemical Data

2.1.1. XRD Analysis of the Precursor Gel

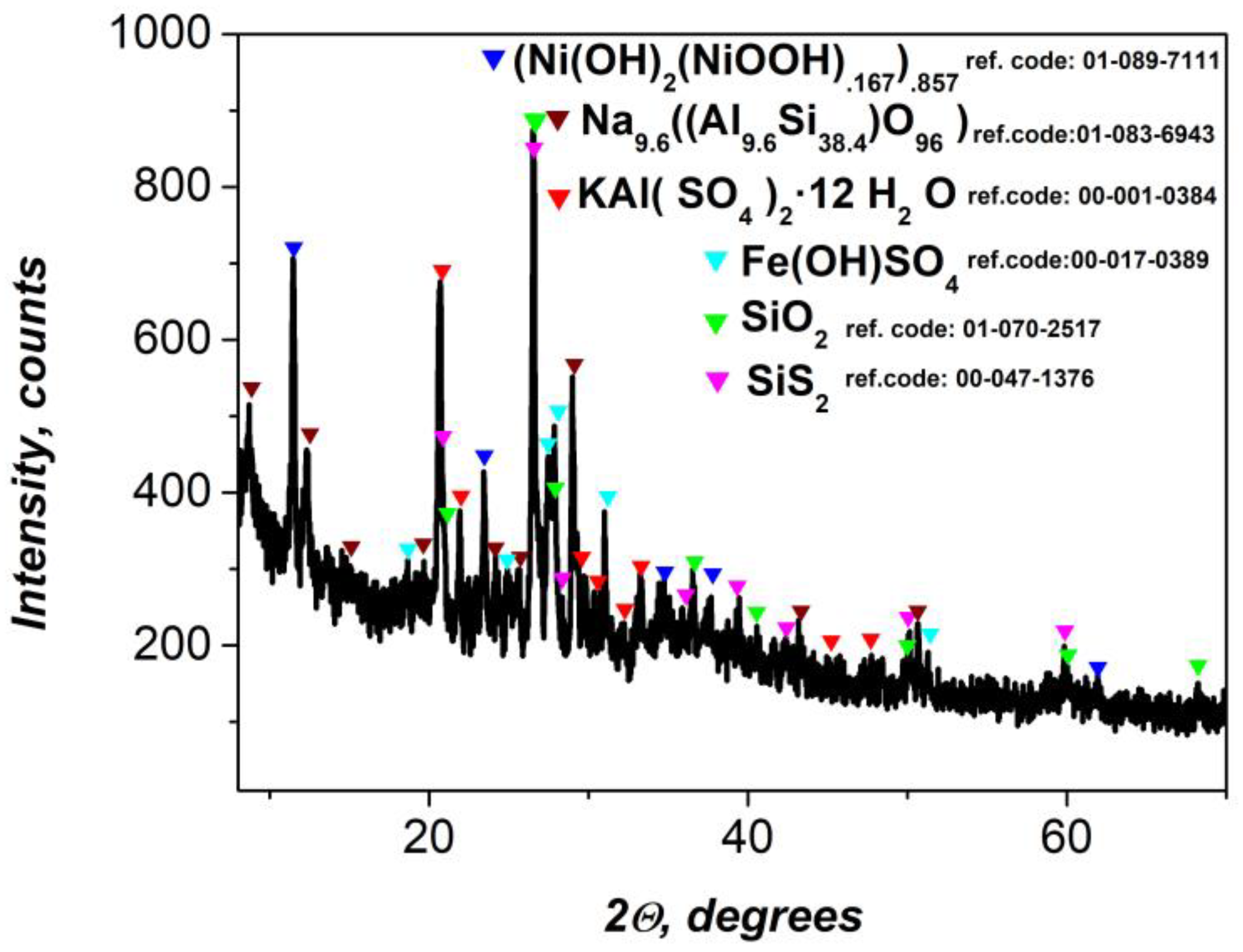

X-ray diffraction (XRD) analysis of the precursor gel (

Figure 1) revealed the presence of multiple crystalline phases, reflecting its heterogeneous origin and complex chemical composition derived from flotation wastewater treatment. The dominant diffraction peaks corresponded to nickel hydroxide and nickel oxyhydroxide species—Ni(OH)₂ / NiOOH—with characteristic reflections consistent with known β-Ni(OH)₂ and γ-NiOOH phases. These phases are known to play an active role in redox reactions and contribute to the electrochemical performance of composite materials.

Diffractogram showed well-defined peaks corresponding to a sodium aluminosilicate phase, identified as Na₉.₆Al₉.₆Si₃₈.₄O₉₆, which is indicative of zeolitic or feldspathoid-type structures. These mineral species may serve as mechanical supports and also contribute to ionic interactions within the matrix [

48].

A third identified phase was iron hydroxysulfate (Fe(OH)SO₄), which reflects the oxidation and precipitation products of Fe³⁺ ions in the acidic flotation environment. This compound may participate in further redox processes or influence charge transport properties when embedded in the polymer matrix [

49]. The XRD results confirm that the gel precursor consists of both electrochemically active (Ni-based) and structurally supportive (silico-aluminate) phases, along with minor transition metal salts, making it a complex but functionally versatile component for nanocomposite fabrication. These findings further confirm the suitability of the material for supercapacitor electrodes, as the crystalline Ni(OH)₂/NiOOH phases are well known for their high pseudocapacitive behavior, and the additional components improve mechanical integrity and electrochemical stability during cycling.

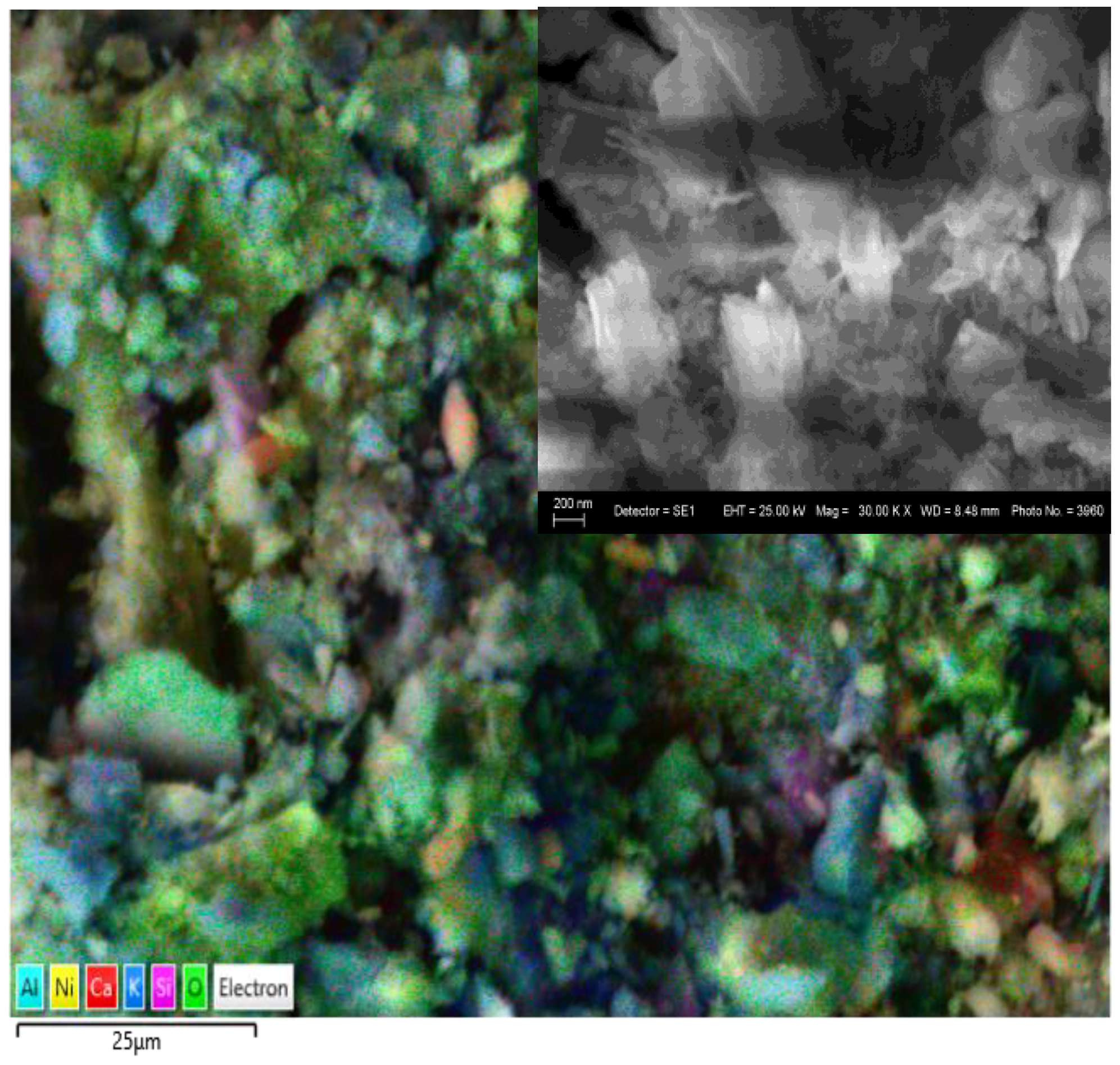

Тhe morphology and elemental composition of the gel prior to polymerization were investigated using scanning electron microscopy (SEM) and energy-dispersive X-ray spectroscopy (EDS). EDS analysis confirmed the presence of a broad range of elements associated with both the original flotation wastewater and the introduced nickel precursor. The elemental composition of the precursor gel is summarized in

Table 1.

The high oxygen content (41.12 wt%) and significant presence of nickel (21.34 wt%) confirm the formation of nickel hydroxides, likely Ni(OH)₂, as a major inorganic component of the gel. The presence of sulfur and carbon also supports the incorporation of xanthate residues (C₂H₅OCS₂⁻) from the flotation reagents, forming mixed organic-inorganic complexes. The elements Al, Si, and Ca likely originate from gangue minerals or residual processing agents. These results indicate that the precursor gel contains a structurally and chemically diverse composition, serving as a multifunctional component for further polymer matrix integration. The structural features and compositional richness observed in the precursor suggest that upon incorporation into the polyaniline matrix, the resulting nanocomposite is likely to exhibit synergistic effects in terms of conductivity, stability, and ion storage. Carbon (7.28 wt%) is attributed to residual organic flotation reagents, primarily xanthates, which are known to bind strongly with transition metals like Ni and Cu. The presence of sulfur (2.37 wt%) further supports the incorporation of xanthate-derived groups (–OCS₂⁻), confirming their retention during the gel formation process. Significant quantities of aluminum (4.44 wt%) and silicon (11.98 wt%) point to the likely entrainment of aluminosilicate species, possibly from gangue minerals in the ore or process residues. Calcium (2.61 wt%), potassium (2.95 wt%), and sodium (2.39 wt%) may derive from the flotation depressants (e.g., CaO) and pH regulators used during ore beneficiation. Trace elements such as Fe (1.63 wt%), Mg (1.18 wt%), and Ti (0.22 wt%) are also present, indicating complex mineralogical diversity.

SEM images (

Figure 2) revealed a heterogeneous, porous structure, indicative of incomplete aggregation of inorganic phases and the presence of organic matrix residues. This morphology facilitates ionic mobility and suggests potential for enhanced electrochemical performance after polymerization.

2.1.2. XRD Analysis of the Polymer Nanocomposite

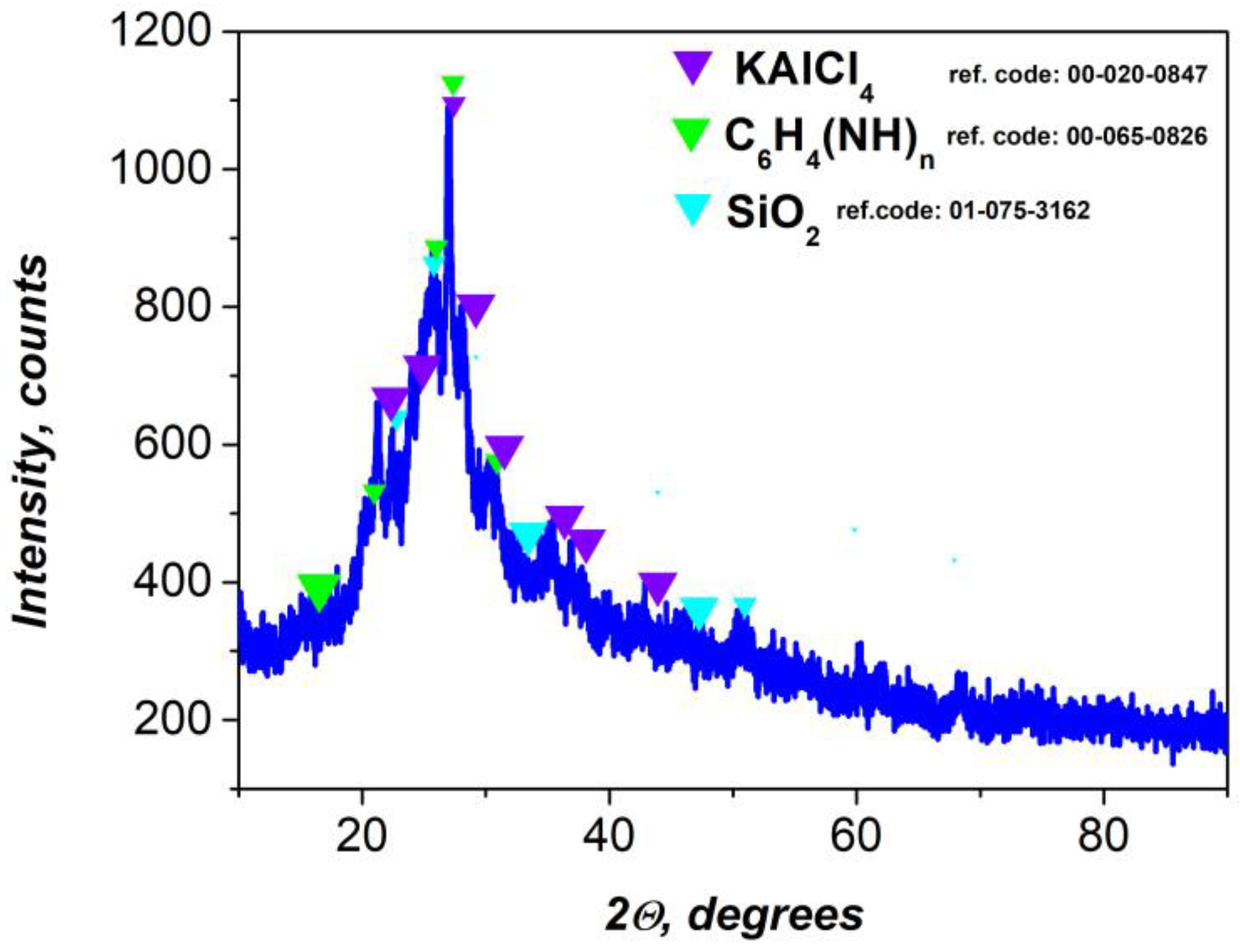

The X-ray diffraction pattern of the final nanocomposite, formed by embedding the flotation-derived gel into a polyaniline matrix, confirms the coexistence of both crystalline and amorphous components (

Figure 3). Three main crystalline phases were identified was KAlCl₄, C₆H₄(NH)ₙ (polyaniline), and SiO₂, indicating a hybrid organic-inorganic structure with functional heterogeneity.

The presence of KAlCl₄ suggests the retention or formation of aluminum–potassium–chloride complexes during the synthesis [

50]. This phase is result from ionic interactions between aluminum ions from the gel and chloride ions from the HCl medium used in the oxidative polymerization. These compounds act as dopants or stabilizers within the polymer matrix, potentially affecting conductivity and morphology.

The polymer matrix, represented by C₆H₄(NH)ₙ, gives rise to broad diffraction features centered near 2θ ≈ 25°, typical of the emeraldine salt form of polyaniline. This broad halo is indicative of a semi-crystalline or amorphous polymer phase, in agreement with previous reports on conductive polyaniline systems [

51].

The detection of SiO₂ the form of amorphous or partially crystalline silica suggests the persistence of inorganic silicate species from the flotation process. The presence of silica can provide mechanical strength and thermal stability to the composite [

52].

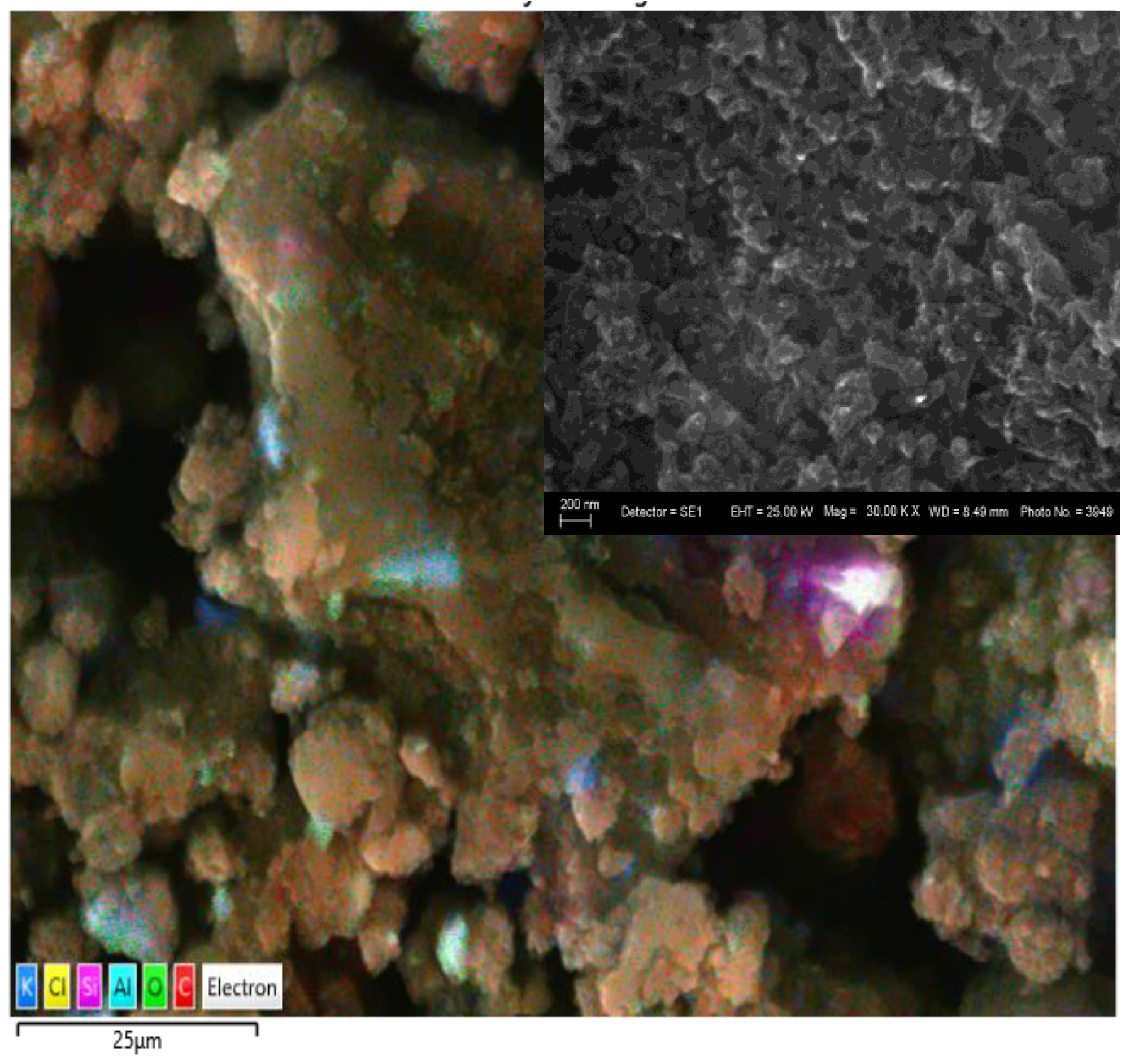

The elemental composition of the final polymer nanocomposite (PANI-MX), determined via energy-dispersive X-ray spectroscopy (EDS), is presented in

Table 2. The analysis reveals a material dominated by carbon (82.96 wt%, 90.74 at%) and oxygen (5.95 wt%), consistent with the presence of a polyaniline matrix and oxidized species.

After the integration of the gel into the polyaniline matrix, EDS analysis shows a sharp increase in the carbon content (82.96 wt%), which corresponds to the formation of a polyaniline film on or around the gel particles

Figure 4. The significant decrease or disappearance of nickel and other metal elements from the surface spectrum (Ni: from 21.34 wt% to below the detection limit) suggests an effective encapsulation of the inorganic components in the polymer network. The appearance of chlorine (7.52 wt%) in the composition is related to the doping of polyaniline with Cl⁻ ions from the HCl medium, which is a known condition for obtaining the conductive “emeraldine salt” form. The presence of sulfur (S) and carbon fragments due to residual xanthate compounds (C₂H₅OCS₂⁻) indicates their preservation in the gel phase and their participation in the final polymer structure. Xanthates probably form metal-organic complexes with Cu²⁺, Ni²⁺ and Fe³⁺ ions, which remain stable after polymerization and act as internal pseudocapacitive centers in the composite. These hybrid complexes contribute to the increase in overall capacitance through fast and reversible surface redox reactions, which builds on the basic charge-storage mechanism characteristic of polyaniline. Polymerization not only “seals” the gel in a conductive polymer shell, but also preserves key functional groups from the waste environment, leading to the formation of a composite electrode with improved electrochemical activity and stability.

2.2. Electrochemical Results

Electrochemical evaluations, including cyclic voltammetry (CV), galvanostatic charge–discharge (GCD) measurements at 20 °C, and long-term cycling tests, were conducted on assembled asymmetric supercapacitor cells incorporating the synthesized material as the negative electrode. For comparison, symmetric supercapacitor cells using YP-50F activated carbon electrodes were tested under identical GCD conditions.

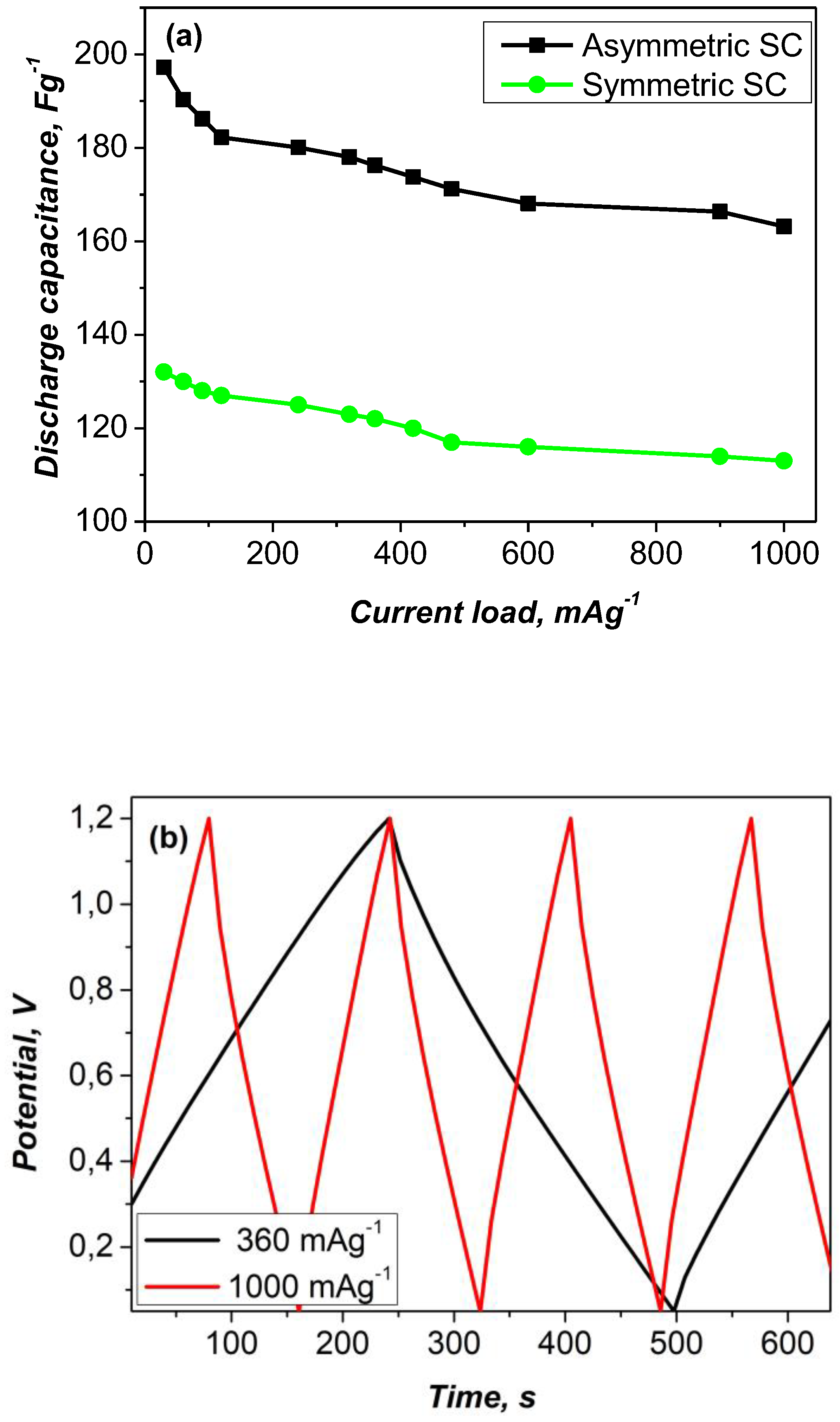

The results of the GCD measurements are shown in

Figure 5a, illustrating the specific discharge capacitance as a function of current load in the range of 60 to 1000 mA g⁻¹. Among the configurations tested, the asymmetric YP-50F/PANI-metal xanthate cell showed higher performance. In this configuration, the polyaniline-metal xanthate composite enhances the pseudo-capacitance via synergistic Faraday redox reactions, while the activated carbon electrode contributes to the electrical double-layer capacitance due to its large surface area. This combination results in significantly improved electrochemical behavior. Furthermore, the presence of multiple metal cations in the wastewater likely facilitates the formation of a variety of metal-xanthate complexes, which further improve redox kinetics, electrical conductivity and overall capacitance. The coexistence of Faraday and non-Faraday processes in the asymmetric configuration contributes to the observed synergistic enhancement of charge storage efficiency.

The voltage profile of the asymmetric device (

Figure 5b) displays characteristic features of a hybrid system and confirms the presence of low internal resistance (iR

360= 0.102V and iR

1000=0.253V). This can be attributed to the homogeneous composition of the electrode and the fast surface redox kinetics at the negative electrode.

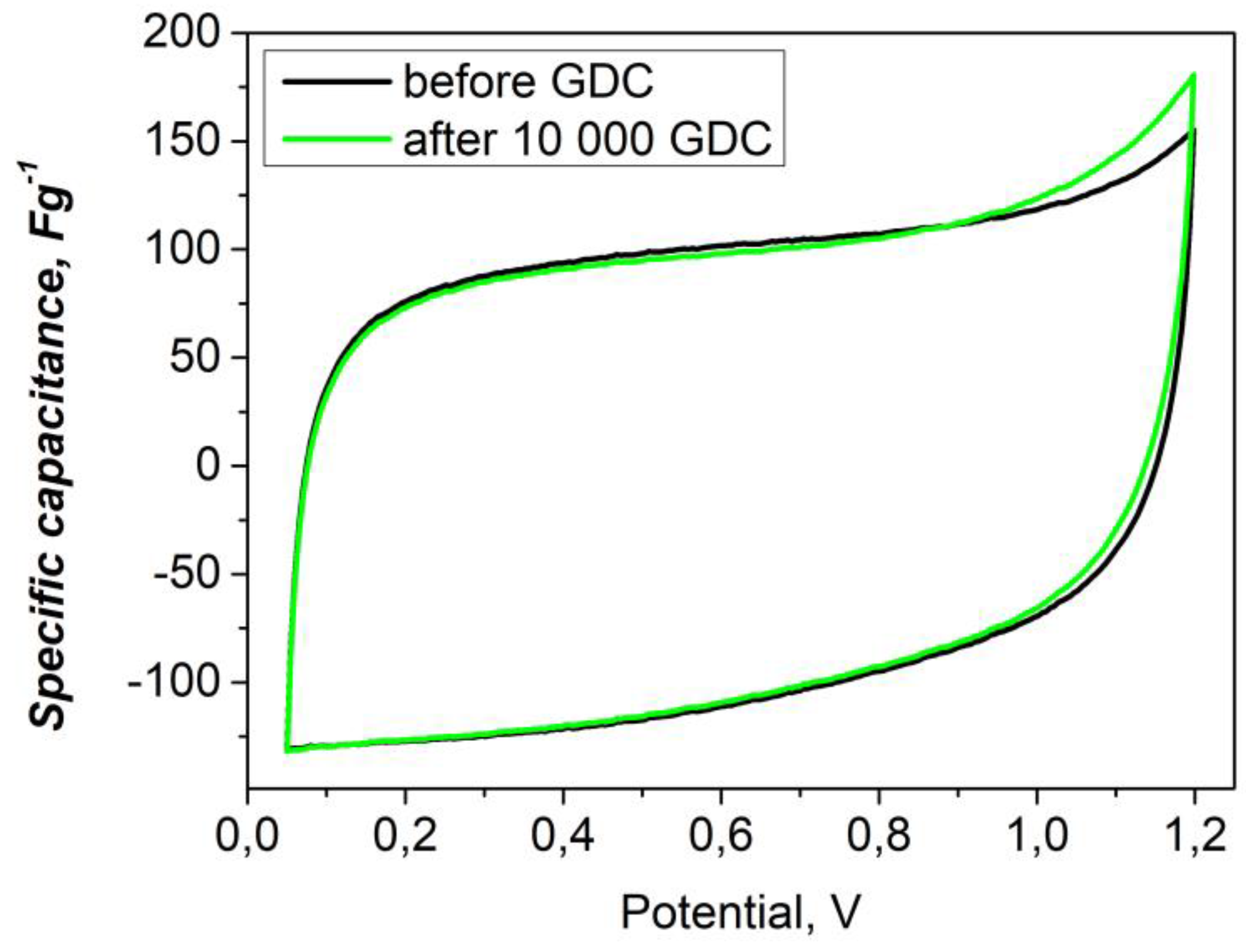

The cyclic voltammetry (CV) profiles of the asymmetric YP-50F // PANI-MX cell remain nearly rectangular even at scan rates as low as 10 mVs-¹ (

Figure 6), indicating excellent capacitive behavior and efficient charge storage kinetics [

53]. In contrast, symmetric supercapacitor cells, although demonstrating good reproducibility of discharge capacitance values, exhibit limited overall charge storage capacitance, likely due to limited ionic diffusion and the lack of additional faradaic processes [

54].

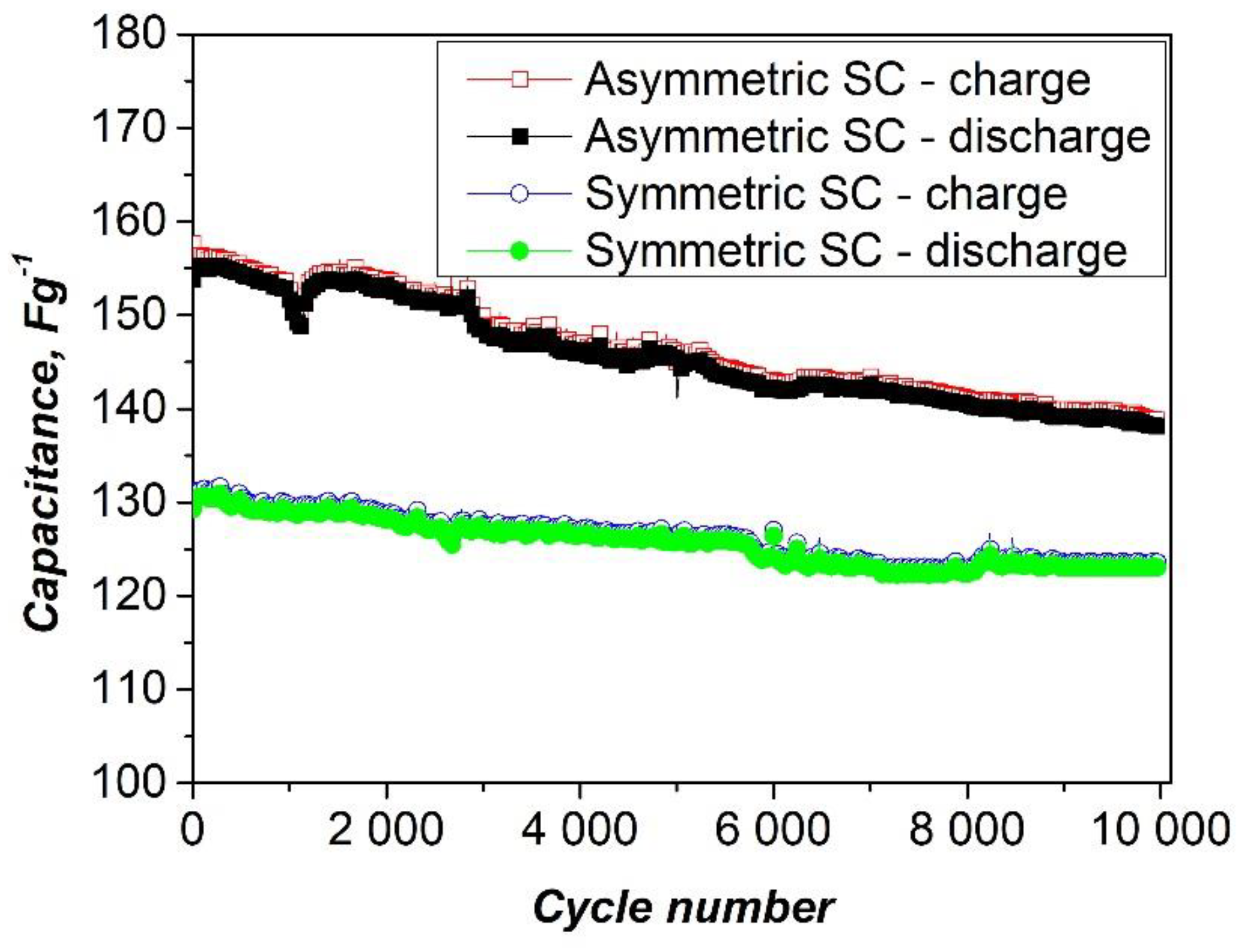

Figure 7 shows the capacitance retention of the asymmetric supercapacitor assembled with a composite of polyaniline and nickel xanthate as the negative electrode and activated carbon as the positive electrode. The long-term cycle stability was evaluated at a high current load of 1000 mAg-¹. As shown, the device exhibits excellent durability, retaining 90.1% of its original capacity after 10,000 charge and discharge cycles, along with a high Coulombic efficiency of 98%. This indicates that the PANI-metal xanthate composite retains its structural integrity and stable interfacial contact with the activated carbon electrode during continuous operation [

55]. The stable cyclability is also confirmed by the CV curves (

Figure 6), which show minimal changes after 10,000 cycles, confirming the stable electrochemical activity and efficient charge storage behavior.

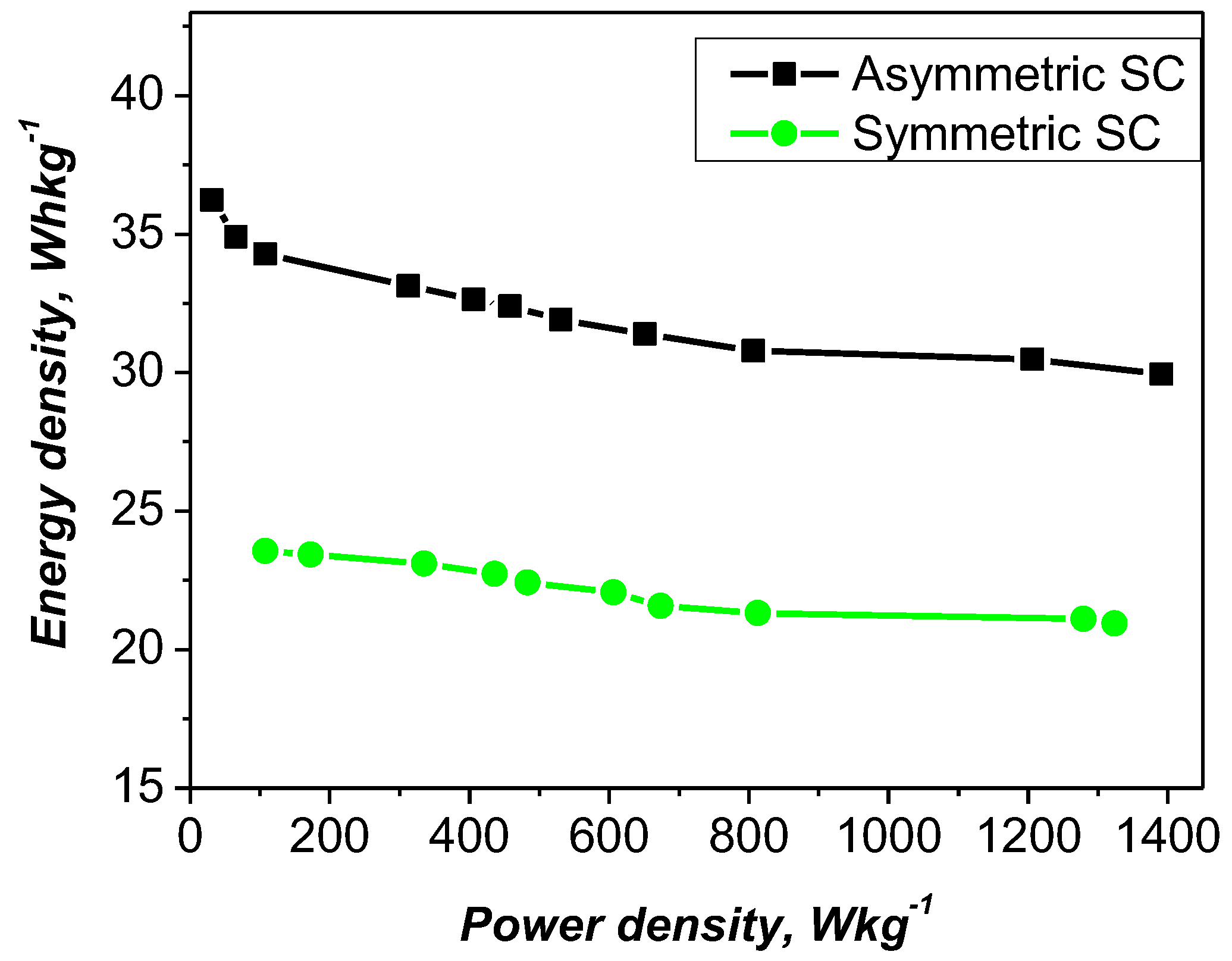

The electrochemical performance of the studied materials was further evaluated using Ragone plots, with a comparison to the symmetric cell shown in

Figure 8. The data indicate that the asymmetric configuration achieves a specific energy density of 35 Wh kg⁻¹ at a power density of 100 W kg⁻¹ and maintains a relatively high value of 32 Wh kg⁻¹ even at 1200 W kg⁻¹. In contrast, the YP-50F/YP-50F symmetric supercapacitor exhibits a lower energy density under the same conditions.

Asymmetric and symmetric cells were evaluated in the same voltage range, which provided a direct and reliable comparison of their electrochemical characteristics. The improved energy and power performance of the asymmetric configuration was attributed to the synergistic interaction between the PANI-metal xanthate (PANI-MX) electrode, synthesized from flotation by-products, and the YP-50F activated carbon electrode. In this configuration, the PANI-MX electrode undergoes Faraday redox reactions, contributing significant pseudocapacitance beyond the electrical double layer mechanism that dominates in symmetric cells. It is important to note here that the presence of multiple metal cations in the effluent allows the formation of diverse metal-xanthate complexes that enhance redox kinetics, conductivity, and overall capacitance. This compositional diversity offers a high degree of adaptability, improving the flexibility and overall efficiency of the asymmetric supercapacitor.

3. Conclusions

This study demonstrates a sustainable and efficient approach for the using of flotation wastewater through the synthesis of a functional metal-xanthate gel, which serves as a key component in high-performance polymer nanocomposite electrodes for supercapacitor applications. The gel, formed via the interaction of nickel powder with metal- and reagent-rich flotation effluents, incorporates nickel hydroxides, xanthate-metal complexes, and silicate residues into a structurally and chemically diverse matrix. Upon integration into a polyaniline network via oxidative polymerization, the resulting nanocomposite exhibited a porous morphology, enhanced conductivity, and a stable crystalline-amorphous phase structure. Structural characterization by SEM, EDS, and XRD confirmed the presence of electrochemically active phases such as Ni(OH)₂/NiOOH and supporting components including KAlCl₄ and SiO₂, all retained after polymerization. Electrochemical evaluation revealed superior performance of the asymmetric supercapacitor configuration, where the PANI-metal xanthate composite electrode delivered high specific capacitance, excellent cycling stability, and significantly improved energy and power densities compared to symmetric counterparts. These enhancements were attributed to the pseudocapacitive redox activity of the gel-derived components and their synergistic interaction with activated carbon.

The potential of flotation waste-derived gels as effective reduction-active precursors for energy materials, contributing to both environmental remediation and enhanced electrochemical functionality, has been successfully demonstrated. This work highlights a practical path towards circular economy strategies in materials science, where industrial by-products are transformed into valuable resources for next-generation energy technologies.

4. Materials and Methods

4.1. Materials and Reagents

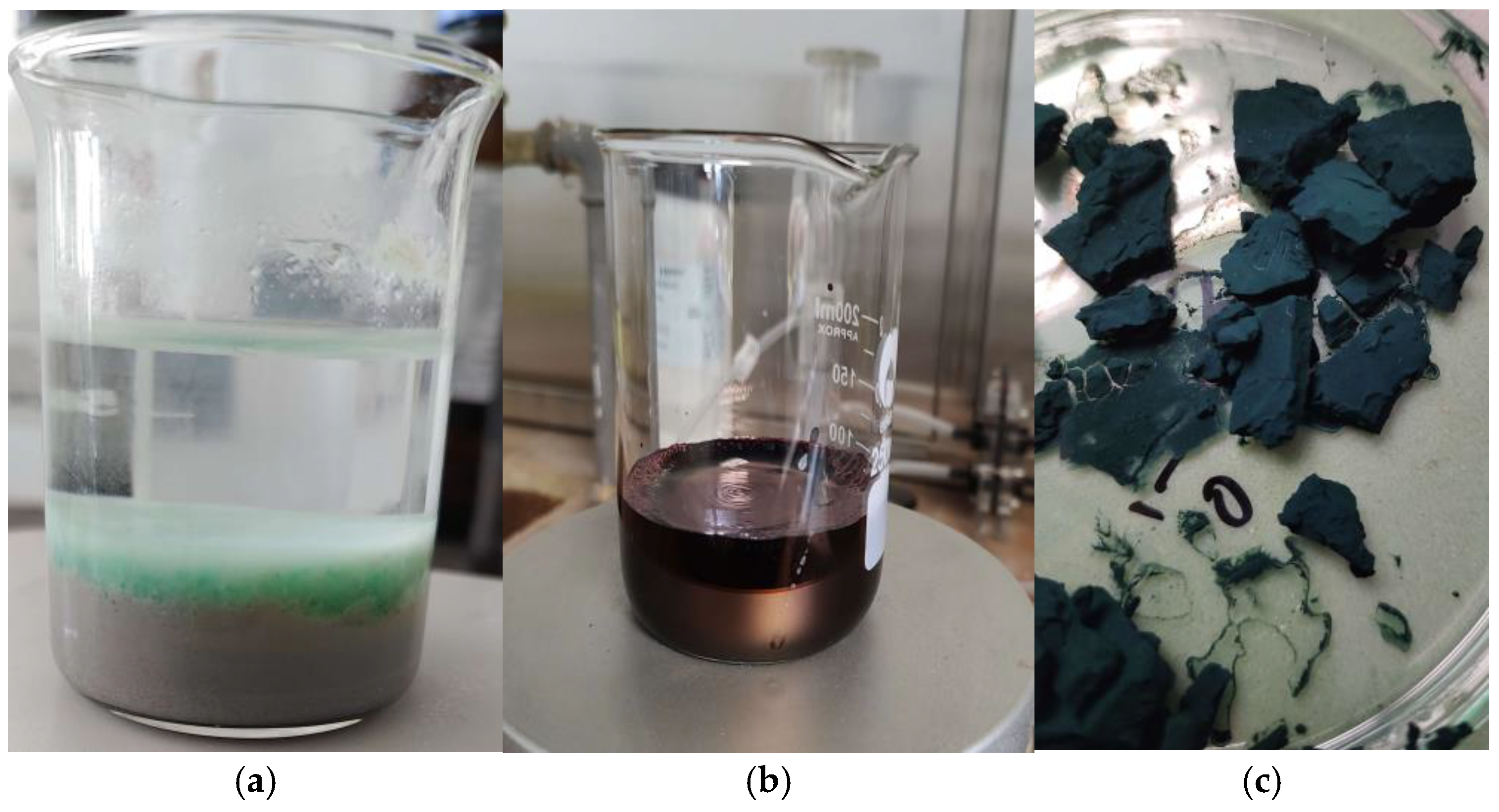

The gel was synthesized by dispersing 0.07 g Nickel, powder, Sigma-Aldrich® (M-Clarity™ quality level = MQ200) into the 70 ml flotation wastewater under continuous stirring at room temperature for 48 hours. Following this process, the intermediate gel-like phase was allowed to settle and was then separated. The resulting gel 16 ml. contained nickel hydroxides, xanthate complexes, and embedded metal ions originating from wastewater. The mechanism of gel formation is shown in

Figure 9.

The obtained gel was integrated into a polyaniline matrix via oxidative polymerization of aniline (0.2 M) using ammonium persulfate (0.25 M) as the oxidizing agent in 1 M hydrochloric acid (HCl), at ambient conditions

Figure 10.

The resulting nanocomposite exhibited a compact, porous morphology and favorable adhesion characteristics (

Figure 11)

4.2. Gel and Nanocomposite Synthesis

The structural properties of the synthesized material were analyzed using X-ray diffraction (XRD) with a Philips ADP15 diffractometer, operating with Cu-Kα radiation (λ = 1.54178 Å). Scans were performed at a steady rate of 0.02° per second, covering a 2θ range from 4° to 80°. The results were interpreted using the PDF 2—2022 database from the International Centre for Diffraction Data (ICDD).

To further examine the morphology, structure, and elemental composition of the synthesized material, scanning electron microscopy (SEM) coupled with Energy Dispersive Spectroscopy (EDS) was employed. These analyses were carried out using a JEOL JSM 6390 microscope (JEOL, Tokyo, Japan), fitted with an INCA Oxford EDS detector (Oxford Instruments, London, UK).

4.3. Electrode Preparation, Cell Assembly, and Electrochemical Characterization

The negative electrode was fabricated using the polyaniline electrode containing the synthesized gel from wastewater. The positive electrode consisted of a composite made from YP-50F activated carbon (Kuraray GmbH), acetylene black, and polytetrafluoroethylene (PTFE) binder. The mixture was uniformly coated onto a nickel foam substrate with an active surface area of 0.64 cm². The electrodes were dried under vacuum at 120 °C and then pressed at 2 MPa to ensure mechanical stability.

The electrodes were assembled into a Swagelok-type two-electrode coin cell in an asymmetric configuration, using Viledon® membrane as the separator and 6 M KOH as the electrolyte. For comparison purposes, symmetric cells consisting of two identical YP-50F-based electrodes were also prepared and evaluated under identical conditions. Electrochemical measurements of the supercapacitors were conducted using cyclic voltammetry (CV) at a scan rate of 10 mV·s⁻¹ in the voltage range of 0.05–1.2 V, both before and after long-term cycling. A Multi PalmSens system (Model 4, The Netherlands) was employed for the CV measurements. Galvanostatic charge-discharge (GCD) tests were performed using an Arbin Instrument System BT-2000 within the same voltage range (0.05–1.2 V). The GCD protocol included sequential current loads ranging from 60 to 1000 mA·g⁻¹, with 30 cycles per step. For long-term cycling, the cells were subjected to 10,000 charge-discharge cycles at a constant current of 1000 mA·g⁻¹.

The specific capacitance (Cs), derived from the cyclic voltammetry data, was calculated using the following equation:

where I is the current, dV/dt is the voltage scan rate, and m is the mass of the active carbon material.

The following equation was used to calculate the specific capacitance from the charge/discharge curves:

where I (A), Δt (s), m (g) and ΔV (V) indicate discharge current, discharge time, mass of active material, and voltage window respectively.

On the basis of the specific discharge capacitance, the energy density (E) and power density (P) is calculated using Equations (3) and (4):

Author Contributions

Writing—original draft preparation, A.G.; conceptualization, A.G.; methodology, A.G., A.S. and G.I.; formal analysis, A.G., A.S. and G.I.; investigation, A.G.; writing—E.P. and A.G.; visualization, E.P., A.G. and A.S.; resources, A.G.; writing—review and editing, E.S. and A.S.; funding acquisition, E.S. All authors have read and agreed to the published version of the manuscript.

Funding

Project No. BG16RFPR002-1.014-0009 “Development and Sustainability of the Center of competence HITMOBIL’’—Technologies and systems for generation, storage and consumption of clean energy”, funded by the Operational Program “Science and Education for Smart Growth” 2014–2020 and co-funded by the EU from the European Regional Development Fund.

Institutional Review Board Statement

Not applicable.

Informed Consent Statement

Not applicable.

Data Availability Statement

This article presents the original findings of the current study. The corresponding author can provide the data discussed in this publication upon request, as it is part of an ongoing investigation.

Acknowledgments

Some of the equipment used at the research are provided by the National Roadmap for Research Infrastructure 2020 -2027 “Energy storage and hydrogen energetics (ESHER)” under grant agreement No. DO1-349/13.12.2023.

Conflicts of Interest

The authors declare no conflicts of interest.

Abbreviations

The following abbreviations are used in this manuscript:

| PANI |

Polyanyline |

| PANI-MX |

PANI-metal xanthate composite |

References

- Simon, P.; Gogotsi, Y. Materials for electrochemical capacitors. Nat. Mater. 2008, 7, 845–854. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Conway, B. E. Electrochemical Supercapacitors: Scientific Fundamentals and Technological Applications. Springer, Boston, MA 1999.

- Wang, G.; Zhang, L.; Zhang, J. A review of electrode materials for electrochemical supercapacitors. Chem. Soc. Rev., 2012, 41, 797–828. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Huang, C.; Zhang, J.; Young, N. P.; Young, N.P.; Snaith, H.N.; Grant, P.S. Solid-State Supercapacitors with Rationally Designed Heterogeneous Electrodes Fabricated by Large Area Spray Processing for Wearable Energy Storage Applications. Sci. Rep., 2016, 6, 25684. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Boeva, Zh. A.; Sergeyev, V. G. Polyaniline: Synthesis, Properties, and Application. Polym. Sci. Ser. C, 2014, 56, 144–153. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Banerjee, J.; Dutta, K.; Kader, M.A.; Nayak, S.K. An overview on the recent developments in polyaniline-based supercapacitors. Polym. Adv. Technol 2025, 36, 1902–1921. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Deshmukh, P. R.; Patil, S. V.; Bulakhe, R. N.; Sartale, S. D.; Lokhande, C. D. Inexpensive synthesis route of porous polyaniline–ruthenium oxide composite for supercapacitor application. J. Chem. Eng., 2014, 257, 82–89. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Wang, J.; Yang, Y.; Huang, Z.H.; Kang, F. Interfacial synthesis of mesoporous MnO2/polyaniline hollow spheres and their application in electrochemical capacitors. ]. J. Power Sources, 2012, 204, 236–243. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Sun, B.; He, Leng, X.; Jiang, Y.; Zhao, Y.; Suo, H.; Zhaoet Ch. Flower-like polyaniline–NiO structures: a high specific capacity supercapacitor electrode material with remarkable cycling stability. RSC Adv., 2016, 6, 43959–43963. [CrossRef]

- Radhakrishnan, S.; Rao, Chepuri R. K.; Vijayan, M. Performance of conducting polyaniline-DBSA and polyaniline-DBSA/Fe3O4 composites as electrode materials for aqueous redox supercapacitors. J. Appl. Polym. Sci., 2011, 122, 1510–1518. [CrossRef]

- Zhu, S.; Zhu, Sh.; Wu, M.; Ge, M.H.; Zhang, H.; Li, S.K.; Li, S.K. Interfacial synthesis of mesoporous MnO2/polyaniline hollow spheres and their application in electrochemical capacitors. J. Power Sources, 2016, 306, 593–601. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Pandiselvi, K.; Thambidurai, S. Chitosan-ZnO/polyaniline ternary nanocomposite for high-performance supercapacitor. Ionics, 2013, 20, 551–561. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Liu, T.; Shao, G.; Ji, M.; Wang, G. Polyaniline/MnO₂ composite with high performance as supercapacitor electrode via pulse electrodeposition. Polym. Compos. 2015, 36, 113–120. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Adnan, S.; Zaidi, S.; Inamuddin, I. High Energy Density Polyaniline/Exfoliated Graphite Based Supercapacitor with Improved Stability in Wide Voltage Window. Orient. J. Chem. 2021, 37, 450–458. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Peng, H.; Ma, G.; Mu, J.; Sunb, K.; Lei, Z. High Energy Density Polyaniline/Exfoliated Graphite Based Supercapacitor with Improved Stability in Wide Voltage Window. J. Mater. Chem., 2014, 2, 10384–10388. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Atta, N. F.; Galal, A.; El-Ads, E. H. Polyaniline nanofibers composite for high performance supercapacitor. Int. J. Electrochem. Sci., 2015, 10, 4000–4018. [Google Scholar]

- Zhang, H.; Bidini, H.; Campanari, S.; Discepoli, G.; Spinelli, M. High performance asymmetric supercapacitors based on polyaniline/reduced graphene oxide composite and activated carbon electrodes. J. Power Sources, 2016, 320, 202–210. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Shin-Liang & Wu, Nae-Lih. Investigation of Pseudocapacitive Charge-Storage Reaction of MnO2 ∙ nH2O Supercapacitors in Aqueous Electrolytes. Journal of The Electrochemical Society 2006, 153, 1317–1324.

- Sharma, K.; Dutta, V.; Sharma, S.; Raizada, P.; Hosseini-Bandegharaei, A. Recent advances in asymmetric supercapacitors: an overview. J. Mater. Sci.: Mater. Electron. 2019, 30, 16503–16531. [Google Scholar]

- Tang, H.; Tang, S.; Zhu, J.; Vongehra, S.; Meng, X. High energy density asymmetric supercapacitors with nickel hydroxide–graphene and activated carbon electrodes. J. Power Sources, 2015, 269, 914–922. [Google Scholar]

- Zhang, L. L.; Zhao, X. Carbon-based materials as supercapacitor electrodes. Chem. Soc. Rev. 2009, 38, 2520–2531. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- El-Kady, M. F.; Strong, V.; Dubin, S.; Kaner R. B. Laser scribing of high-performance and flexible graphene-based electrochemical capacitors. Science 2012, 335, 1326–1330. [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Wu, Z. S.; Zhou, S.; Yin, L. C.; Ren, W.; Li, F.; Cheng, H. M. Graphene/metal oxide composite electrode materials for energy storage. Nano Energy 2010, 1, 107–131.

- Zhang, J.; Mendhe, A.; Rakhade, H.; Barse, N.; et al. Flexible and high energy density supercapacitor based on polyaniline/graphene hybrid electrodes. Carbon 2014, 77, 190–199. [Google Scholar]

- Ma, Jun & Tang, Shaochun & Ali, Syed & Su, Dongyun & Meng, Xiangkang. High-performance asymmetric supercapacitors based on reduced graphene oxide/polyaniline composite electrodes with sandwich-like structure. Journal of Materials Science & Technology 2017, 34.

- Simon, P.; Gogotsi, Y. Perspectives for electrochemical capacitors and related devices. Nat. Mat. 2020, 19, 1151–1163. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Zheng, J. P.; Cygan, P. J.; Jow, T. R. Hydrous ruthenium oxide as an electrode material for electrochemical capacitors. J. Electrochem. Soc. 1995, 142, 2699–2703. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Brousse, T.; Bélanger, D.; Long, J. W. To be or not to be pseudocapacitive? J. Electrochem. Soc. 2015, 162, A5185–A5189. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- González, A.; Goikolea, E.; Barrena J., A.; Mysyk, R. Review on supercapacitors: technologies and materials. Renew. Sust. Energ 2016, 58, 1189–1206. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Jost, K.; Perez, K.; McDonoug, J.; Presser, V.; Heon, M.; Diona, G.; Gogotsi, Y. Carbon coated textiles for flexible supercapacitors. Energy Environ. Sci. 2011, 4, 5060–5067. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Zhang, J.; Zhao, X.; Zhao, Y. A comparative study of various nanostructured carbon materials in flexible supercapacitors. Nanoscale 2013, 5, 3624–3629. [Google Scholar]

- Miller, J. R.; Simon, P. Materials science: Electrochemical capacitors for energy management. Science 2008, 321, 651–652. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Frackowiak, E.; Béguin, F. Carbon materials for the electrochemical storage of energy in capacitors. Carbon 2001, 39, 937–950. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Liu, C.; Yu, Z.; Neff, D.; Zhamu, A.; Jang, B. Z. Graphene-based supercapacitor with an ultrahigh energy density. Nano Lett. 2010, 10, 4863–4868. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Xu, Y.; Lin, Z.; Huang, X.; Liu, Y.; Huang, Y.; Duan, X. Flexible solid-state supercapacitors based on three-dimensional graphene hydrogel films. ACS Nano 2013, 7, 4042–4049. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Wang, K.; Li, H.; Song, J.; Wang, L. Flexible solid-state supercapacitor based on polyaniline/MnO₂ nanowire array hybrid structure. Nano Energy, 2012, 1, 107–131. [Google Scholar]

- Yoo, J. J.; Balakrishnan, K.; Huang, J.; Meunier, V.; et al. Ultrathin planar graphene supercapacitors. Nano Lett. 2011, 11, 1423–1427. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Zhou, G.; Wang, D.; Li, F.; Zhang, L. Graphene-wrapped Fe₃O₄ anode material with improved reversible capacity and cyclic stability for lithium ion batteries. Chem. Mat., 2010, 22, 5306–5313. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Chen, W.; Zhang, C.; Liu, Z.; Wang, L.; Han, P.; et al. Nitrogen-doped graphene nanosheets with excellent lithium storage properties. J. Mater. Chem 2011, 21, 17303–17306. [Google Scholar]

- Wei, W.; Cui, X.; Chen, W.; Ivey, D. G. Manganese oxide-based materials as electrochemical supercapacitor electrodes. Chem. Soc. Rev. 2011, 40, 1697–1721. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Zhai, Y.; Dou, Y.; Zhao, D.; Fulvio, P.; Mayes, R.; Dai, S. Carbon materials for chemical capacitive energy storage. Adv. Mat. 2011, 23, 4828–4850. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Yu, G.; Zhang, T.; Yang, X.; Zhang, L.; Leng, K.; Huanga, Y.; Chen, Y. A light-weight hybrid supercapacitor with energy density comparable to Li-ion batteries. ACS Nano 2013, 7, 4033–4041. [Google Scholar]

- Wang, Q.; Yan, J.; Fan, Z. Carbon materials for high volumetric performance supercapacitors: Design, progress, challenges and opportunities. Energy Environ. Sci. 2016, 9, 729–762. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Yang, Z.; Ren J.; Zhang Z.; Chen X.; Guan G.; Qiu L.; Zhang Y, Peng. Recent advancement of nanostructured carbon for energy applications. Chem. Rev. 2013, 113, 8261–8323.

- Shao, Y.; El-Kady, M. F.; Wang, L. J.; Zhang, Q.; Li, Y.; Wang, H.; Kaner, R. B. Graphene-based materials for flexible supercapacitors. Chemical Society Reviews 2015, 44, 3639–3665. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Stoller, M. D.; Ruoff, R. S. Best practice methods for determining an electrode material's performance for ultracapacitors. Energy Environ. Sci. 2010, 3, 1294–1301. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- El-Kady, M. F.; Strong, V.; Dubin, S.; Kaner, R. B. Laser scribing of high-performance and flexible graphene-based electrochemical capacitors. Science, 2012, 335, 1326–1330. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Zhu, Y.; Murali, S.; Stoller, M. D.; Ganesh, K. J.; Cai, W.; Ferreira, P. J.; Ruoff, R. S. Carbon-based supercapacitors produced by activation of graphene. Science 2011, 332, 1537–1541. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Zhu, S.; Wu, M.; Ge M., H.; Zhang, H.; Li, S.K.; Li, S.H. Design and construction of three-dimensional CuO/polyaniline/rGO ternary hierarchical architectures for high performance supercapacitors. J. Power Sources, 2016, 306, 593–601. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Wang, D. W.; Li, F.; Zhao, J.; Ren, W.; Chen Z., G.; Tan, J.; Wu Z., S.; Gentle, I.; Lu G., Q.; Cheng H., M. Fabrication of graphene/polyaniline composite paper via in situ anodic electropolymerization for high-performance flexible electrode. ACS Nano 2009, 3, 1745–1752. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Shen, Jiali, Chongyang Yang, Xingwei Li and Gengchao Wang. “High-performance asymmetric supercapacitor based on nanoarchitectured polyaniline/graphene/carbon nanotube and activated graphene electrodes. ACS applied materials & interfaces 2013, 17, 8467–8476.

- Yang, Y. ; Xi, Y.; Li, J. Flexible Supercapacitors Based on Polyaniline Arrays Coated Graphene Aerogel Electrodes. Nanoscale Res Lett. 2017, 12, 394. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Rey-Raap, N.; Angel Menéndez, J.; Arenillas, A. RF xerogels with tailored porosity over the entire nanoscale. Microporous Mesoporous Mat. 2014, 195, 266–275. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Huang, C.; Zhang, J.; Young, N.P.; Snaith, H.J.; Grant, P.S. Solid-State Supercapacitors with Rationally Designed Heterogeneous Electrodes Fabricated by Large Area Spray Processing for Wearable Energy Storage Applications. Sci Rep 2016, 6, 25684. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Wang, J.; Yu, X.; Wang, C.; Xiang, K.; Deng, M.; Yin, H. PAMPS/MMT composite hydrogel electrolyte for solid-state supercapacitors. J. Alloys Compd. 2017, 709, 596–601. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

|

Disclaimer/Publisher’s Note: The statements, opinions and data contained in all publications are solely those of the individual author(s) and contributor(s) and not of MDPI and/or the editor(s). MDPI and/or the editor(s) disclaim responsibility for any injury to people or property resulting from any ideas, methods, instructions or products referred to in the content. |

© 2025 by the authors. Licensee MDPI, Basel, Switzerland. This article is an open access article distributed under the terms and conditions of the Creative Commons Attribution (CC BY) license (http://creativecommons.org/licenses/by/4.0/).