Submitted:

12 April 2024

Posted:

12 April 2024

You are already at the latest version

Abstract

Keywords:

1. Introduction

2. Materials and Methods

2.1. Materials

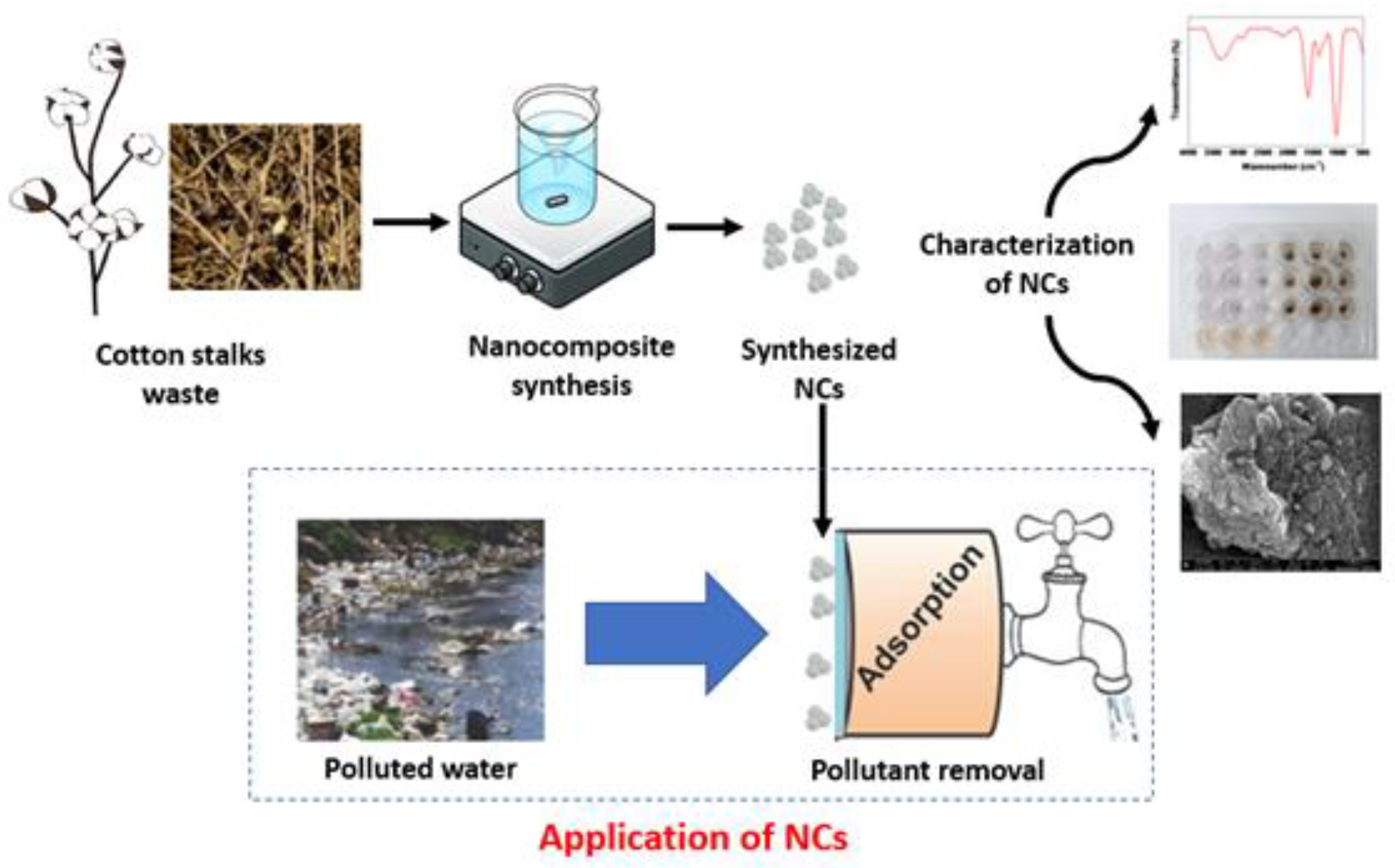

2.2. Synthesis of Cobalt-Doped Cerium Iron Oxide Nanocomposites (CCIO NCs)

2.3. Characterization of Synthesized CCIO NCs

2.4. Preparation of Cationic Dyes

2.5. Preparation of Hexavalent Chromium Solution

2.6. Adsorption Analysis

2.7. Antioxidant Activity

2.8. Antimicrobial Activity

2.9. Recycling and Reuse of Used CCIO NCs.

3. Results and Discussion

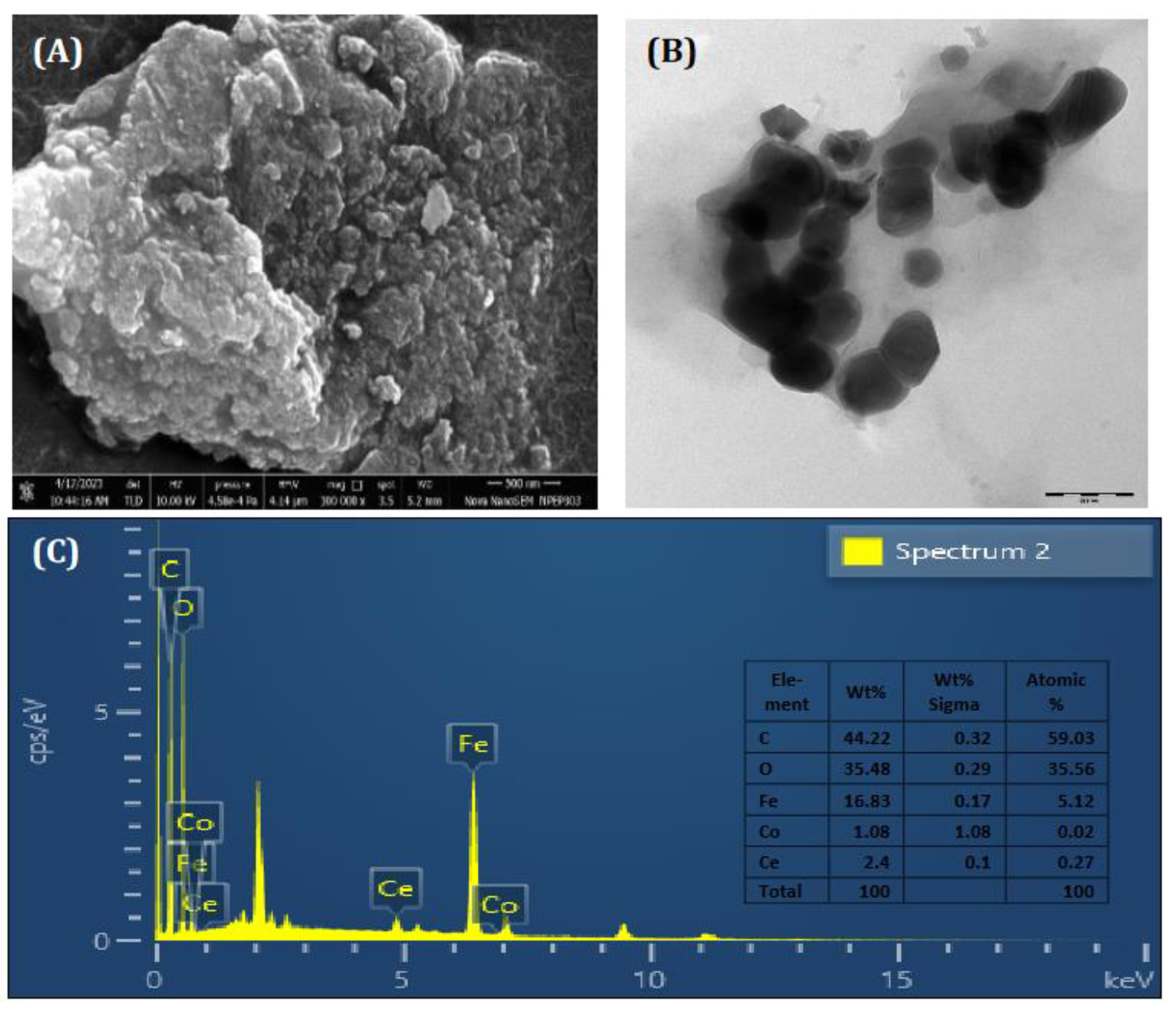

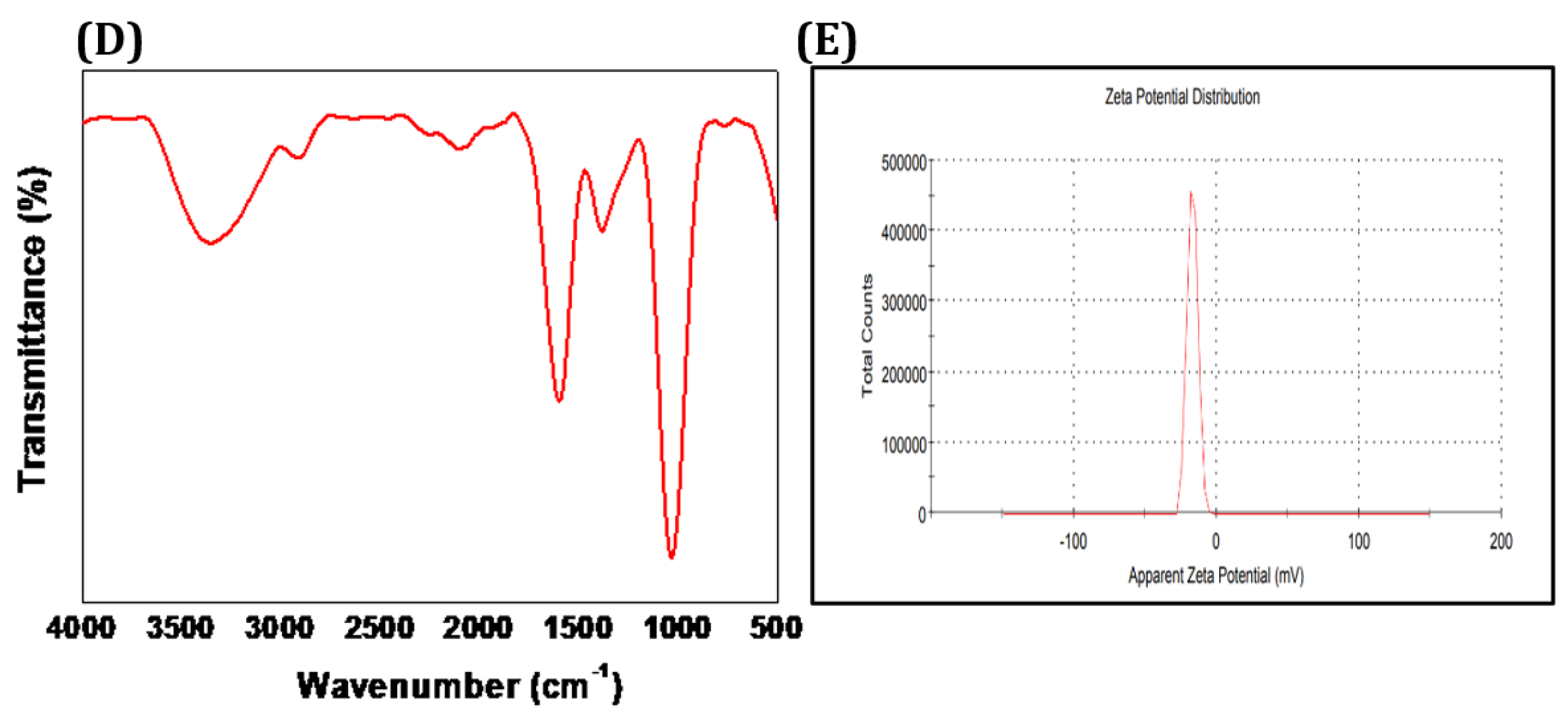

3.1. Characterization of the Synthesized CCIO NCs.

3.2. Adsorption Studies

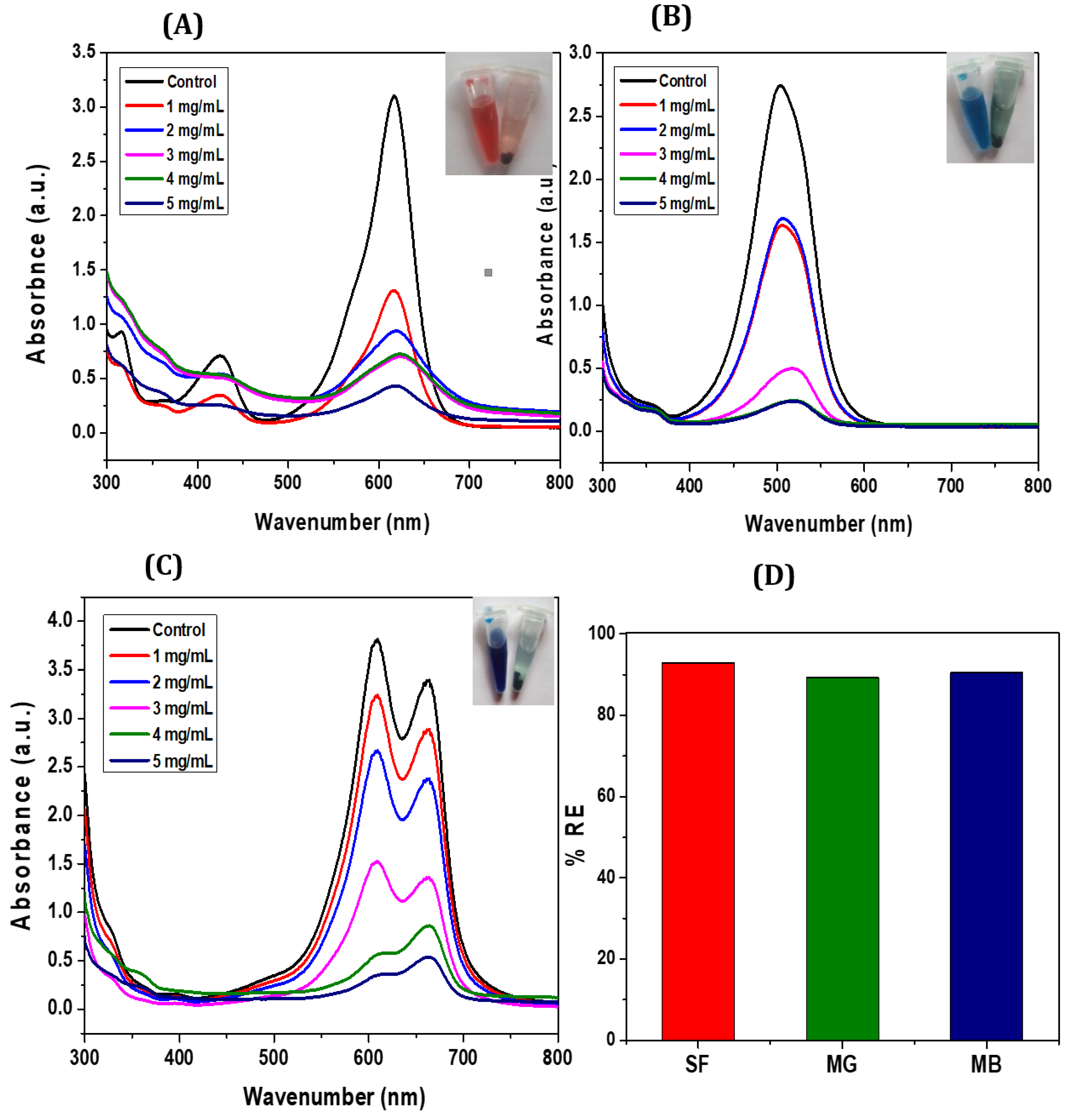

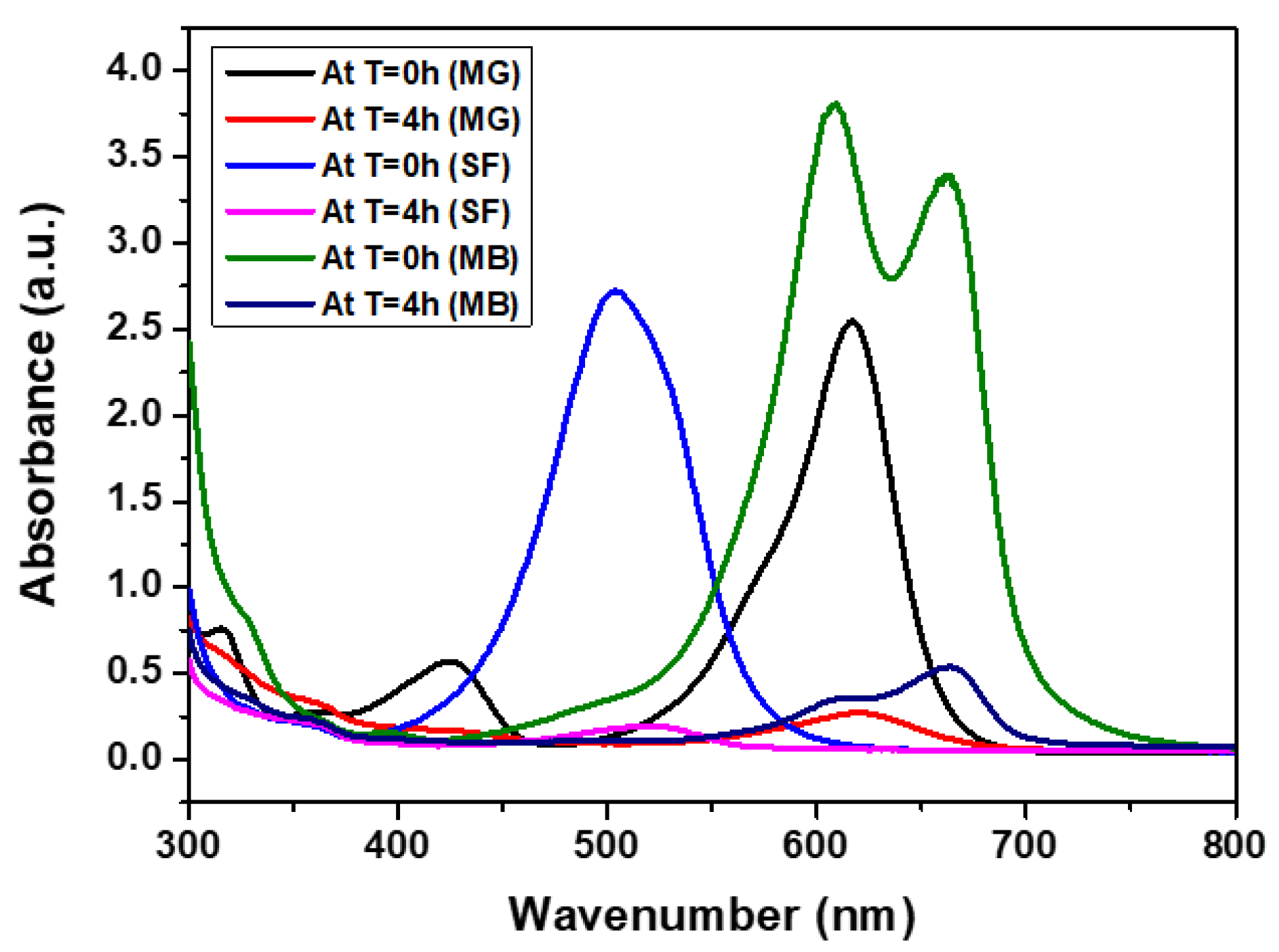

3.2.1. Adsorption Performance of CCIO NCs for Cationic Dyes

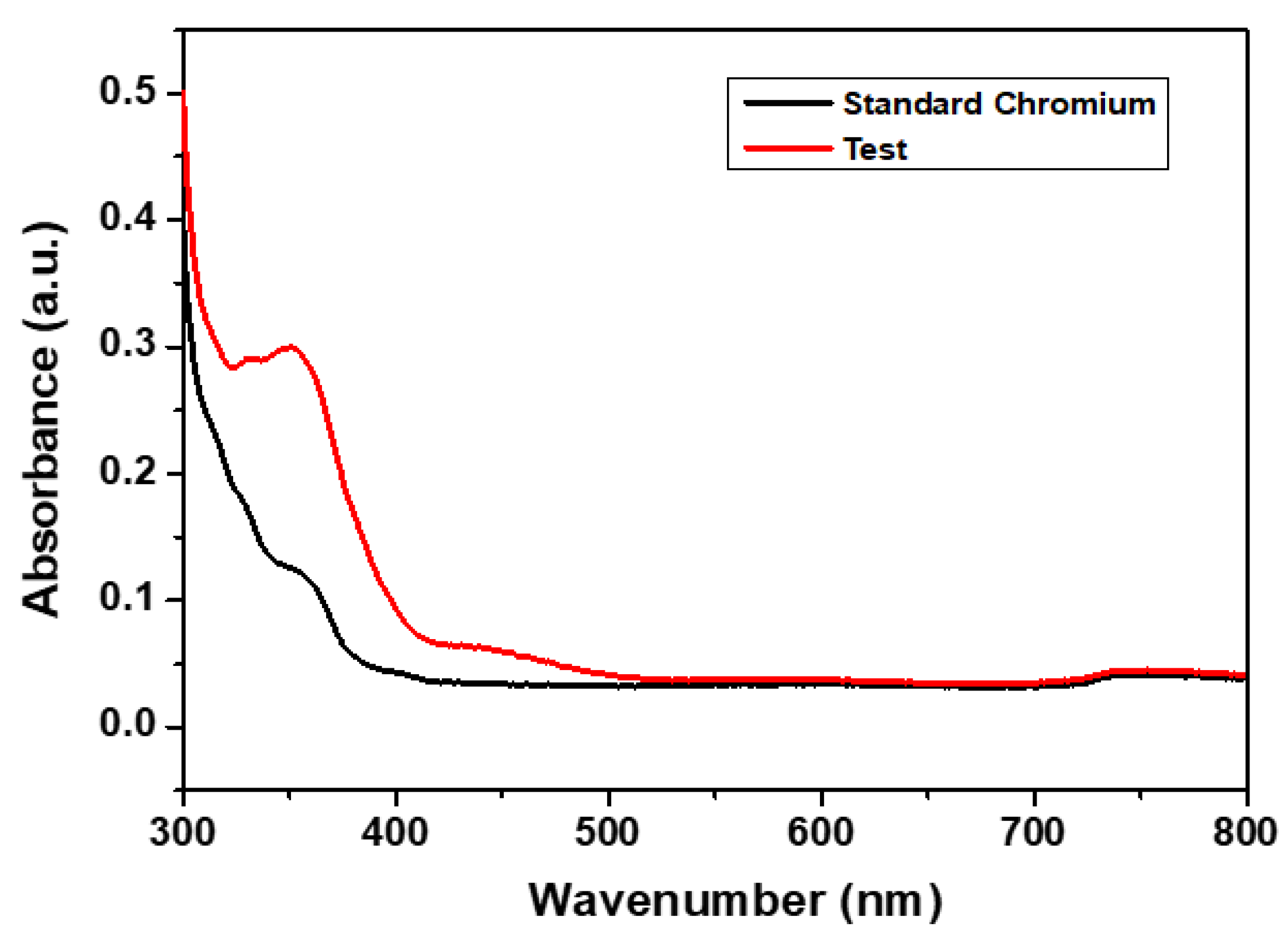

3.2.2. Adsorption Performance of CCIO NCs for Chromium

3.2.3. Comparative Analysis

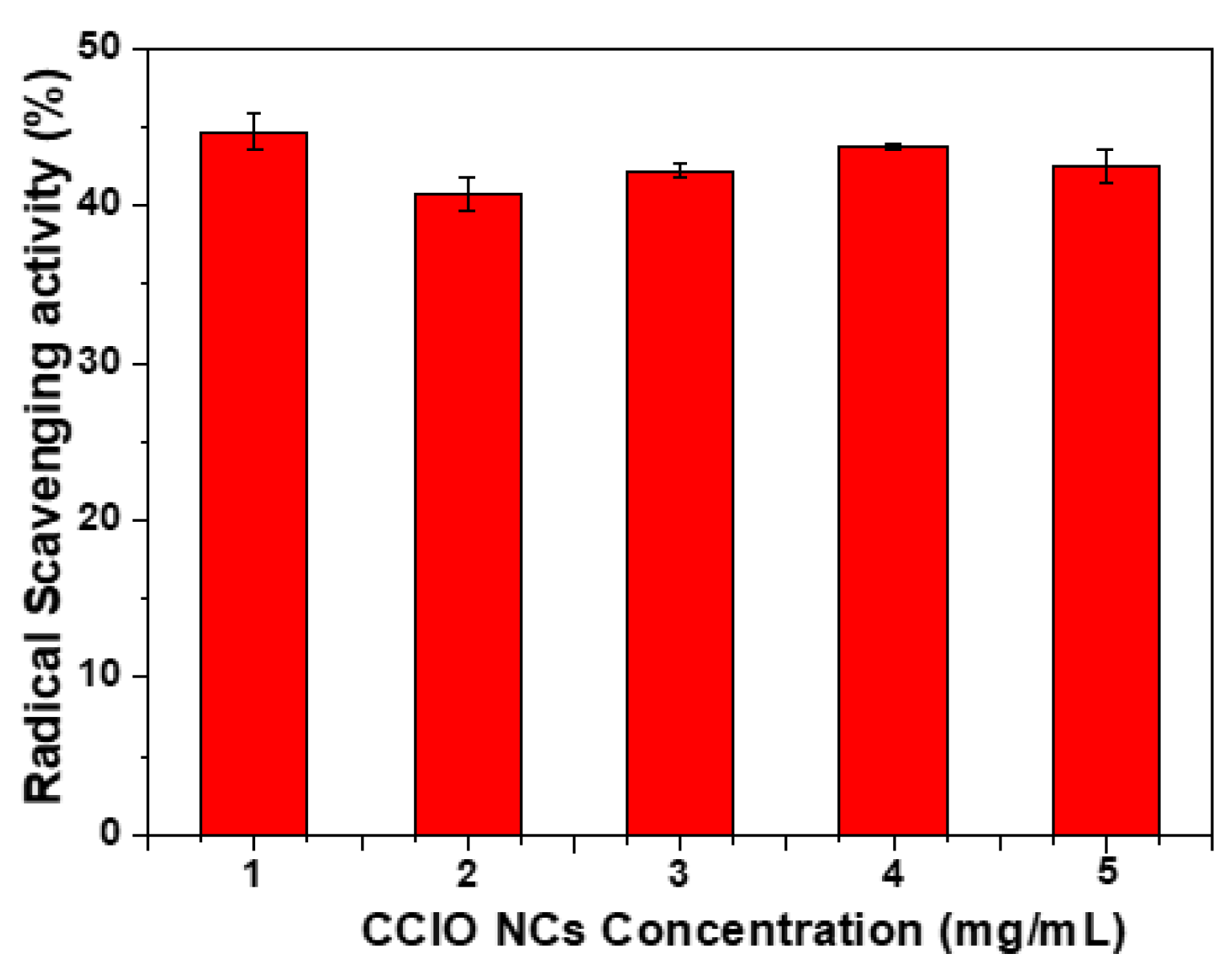

3.3. Radical Scavenging Activity

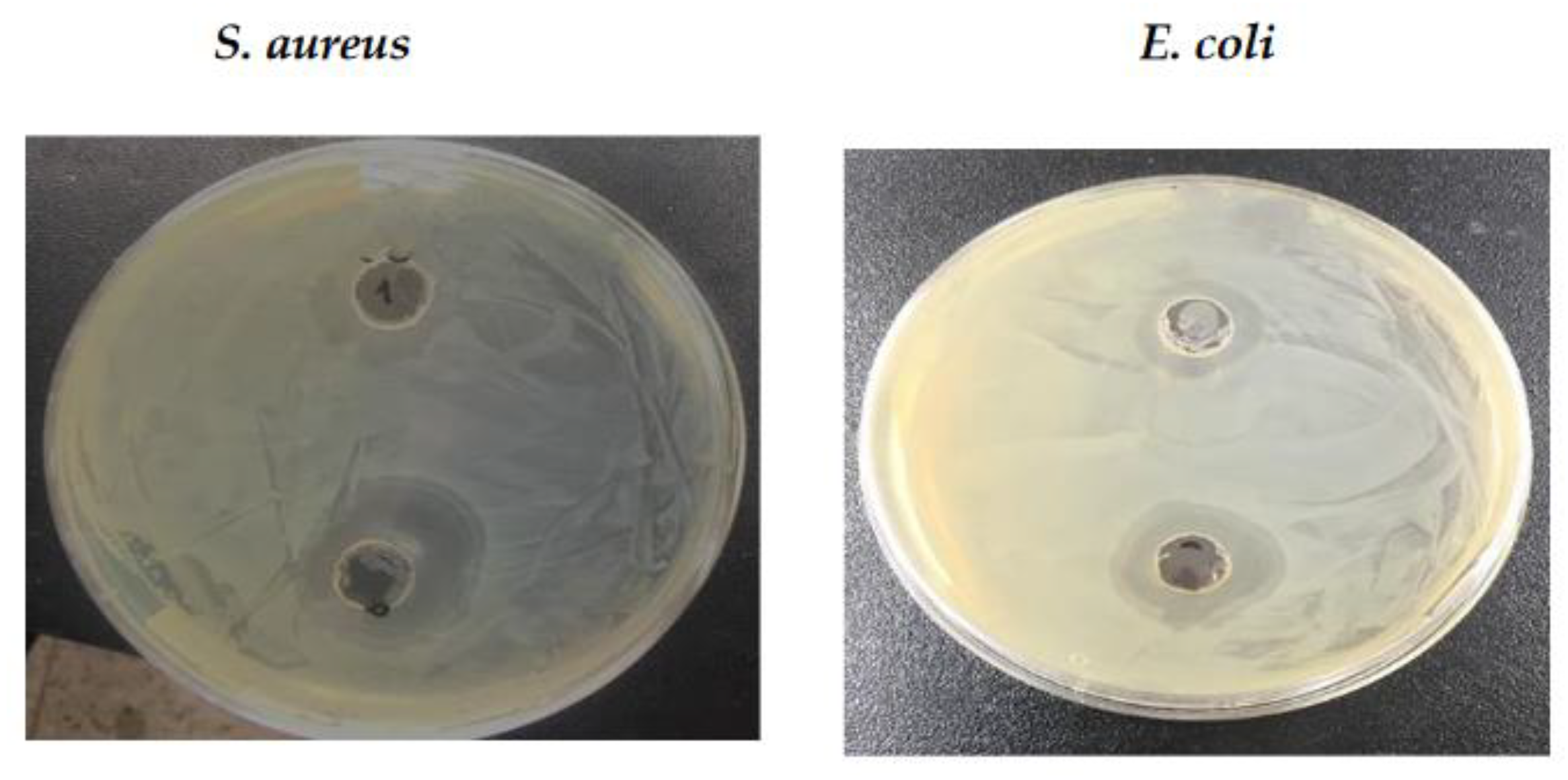

3.4. Antimicrobial Activity

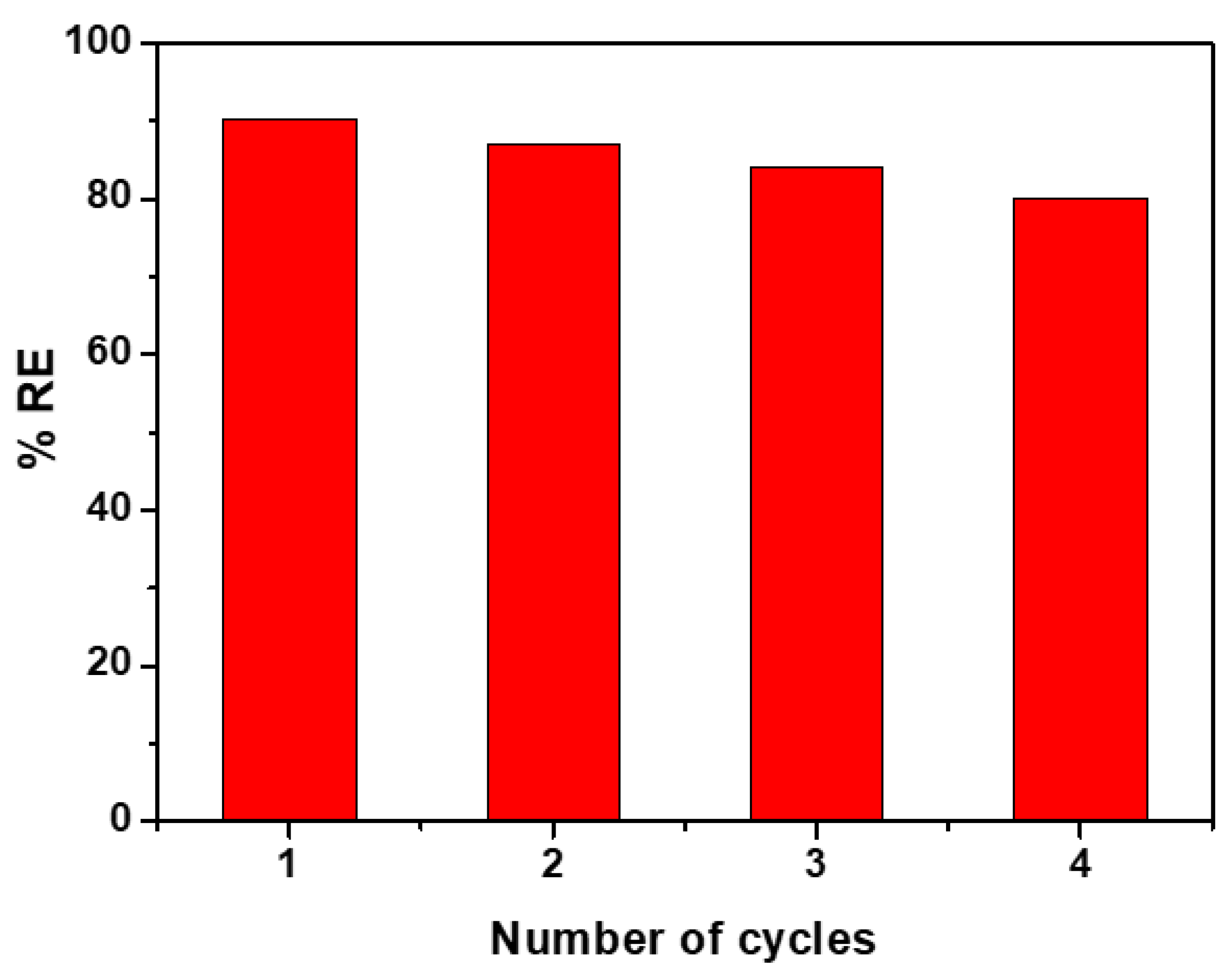

3.5. Reusability of CCIO NCs

4. Conclusions

Supplementary Materials

Author Contributions

Funding

Institutional Review Board Statement

Data Availability Statement

Acknowledgments

Conflicts of Interest

References

- Loux, N.T.; Su, Y.S.; Hassan, S.M. Issues in Assessing Environmental Exposures to Manufactured Nanomaterials. International Journal of Environmental Research and Public Health 2011, 8, 3562–3578. [CrossRef]

- Balali-Mood, M.; Naseri, K.; Tahergorabi, Z.; Khazdair, M.R.; Sadeghi, M. Toxic Mechanisms of Five Heavy Metals: Mercury, Lead, Chromium, Cadmium, and Arsenic. Frontiers in Pharmacology 2021, 12.

- Ahmad, W., Khursheed; Kumari, J., Nirmala; Rashid, B., Ajmal Impact of Textile Dyes on Public Health and the Environment; IGI Global, 2019; ISBN 978-1-79980-313-3.

- Mudgal, V.; Madaan, N.; Mudgal, A.; Singh, R.B.; Mishra, S. Effect of Toxic Metals on Human Health. The Open Nutraceuticals Journal 2010, 3.

- Anastopoulos, I.; Hosseini-Bandegharaei, A.; Fu, J.; Mitropoulos, A.C.; Kyzas, G.Z. Use of Nanoparticles for Dye Adsorption: Review. Journal of Dispersion Science and Technology 2018, 39, 836–847. [CrossRef]

- Baig, N.; Kammakakam, I.; Falath, W. Nanomaterials: A Review of Synthesis Methods, Properties, Recent Progress, and Challenges. Materials Advances 2021, 2, 1821–1871. [CrossRef]

- Hlongwane, G.N.; Sekoai, P.T.; Meyyappan, M.; Moothi, K. Simultaneous Removal of Pollutants from Water Using Nanoparticles: A Shift from Single Pollutant Control to Multiple Pollutant Control. Science of The Total Environment 2019, 656, 808–833. [CrossRef]

- Hussain, I. Green Synthesis of Nanoparticles and Its Potential Application.

- Savage, N.; Diallo, M.S. Nanomaterials and Water Purification: Opportunities and Challenges. J Nanopart Res 2005, 7, 331–342. [CrossRef]

- Lee, C.S.; Robinson, J.; Chong, M.F. A Review on Application of Flocculants in Wastewater Treatment. Process Safety and Environmental Protection 2014, 92, 489–508. [CrossRef]

- Leiknes, T. The Effect of Coupling Coagulation and Flocculation with Membrane Filtration in Water Treatment: A Review. Journal of Environmental Sciences 2009, 21, 8–12. [CrossRef]

- Wang, J.; Chen, H. Catalytic Ozonation for Water and Wastewater Treatment: Recent Advances and Perspective. Science of The Total Environment 2020, 704, 135249. [CrossRef]

- Hube, S.; Eskafi, M.; Hrafnkelsdóttir, K.F.; Bjarnadóttir, B.; Bjarnadóttir, M.Á.; Axelsdóttir, S.; Wu, B. Direct Membrane Filtration for Wastewater Treatment and Resource Recovery: A Review. Science of The Total Environment 2020, 710, 136375. [CrossRef]

- Perrich, J.R. Activated Carbon Adsorption For Wastewater Treatment; CRC Press, 2018; ISBN 978-1-351-07791-0.

- Shahedi, A.; Darban, A.K.; Taghipour, F.; Jamshidi-Zanjani, A. A Review on Industrial Wastewater Treatment via Electrocoagulation Processes. Current Opinion in Electrochemistry 2020, 22, 154–169. [CrossRef]

- Butler, E.; Hung, Y.-T.; Yeh, R.Y.-L.; Suleiman Al Ahmad, M. Electrocoagulation in Wastewater Treatment. Water 2011, 3, 495–525. [CrossRef]

- Rashid, R.; Shafiq, I.; Akhter, P.; Iqbal, M.J.; Hussain, M. A State-of-the-Art Review on Wastewater Treatment Techniques: The Effectiveness of Adsorption Method. Environ Sci Pollut Res 2021, 28, 9050–9066. [CrossRef]

- Rajendran, S.; Priya, A.K.; Senthil Kumar, P.; Hoang, T.K.A.; Sekar, K.; Chong, K.Y.; Khoo, K.S.; Ng, H.S.; Show, P.L. A Critical and Recent Developments on Adsorption Technique for Removal of Heavy Metals from Wastewater-A Review. Chemosphere 2022, 303, 135146. [CrossRef]

- Brahmi, M.; Hassen, A. Ultraviolet Radiation for Microorganism Inactivation in Wastewater. Journal of Environmental Protection 2012, 2012. [CrossRef]

- Oller, I.; Malato, S.; Sánchez-Pérez, J.A. Combination of Advanced Oxidation Processes and Biological Treatments for Wastewater Decontamination—A Review. Science of The Total Environment 2011, 409, 4141–4166. [CrossRef]

- Prasse, C.; Ternes, T. Removal of Organic and Inorganic Pollutants and Pathogens from Wastewater and Drinking Water Using Nanoparticles – A Review. In Nanoparticles in the Water Cycle: Properties, Analysis and Environmental Relevance; Frimmel, F.H., Niessner, R., Eds.; Springer: Berlin, Heidelberg, 2010; pp. 55–79 ISBN 978-3-642-10318-6.

- Aragaw, T.A.; Bogale, F.M.; Aragaw, B.A. Iron-Based Nanoparticles in Wastewater Treatment: A Review on Synthesis Methods, Applications, and Removal Mechanisms. Journal of Saudi Chemical Society 2021, 25, 101280. [CrossRef]

- Mondal, P.; Nandan, A.; Ajithkumar, S.; Siddiqui, N.A.; Raja, S.; Kola, A.K.; Balakrishnan, D. Sustainable Application of Nanoparticles in Wastewater Treatment: Fate, Current Trend & Paradigm Shift. Environmental Research 2023, 232, 116071. [CrossRef]

- Theerthagiri, J.; Lee, S.J.; Karuppasamy, K.; Park, J.; Yu, Y.; Kumari, M.L.A.; Chandrasekaran, S.; Kim, H.-S.; Choi, M.Y. Fabrication Strategies and Surface Tuning of Hierarchical Gold Nanostructures for Electrochemical Detection and Removal of Toxic Pollutants. Journal of Hazardous Materials 2021, 420, 126648. [CrossRef]

- Singh, J.; Kumar, V.; Singh Jolly, S.; Kim, K.-H.; Rawat, M.; Kukkar, D.; Tsang, Y.F. Biogenic Synthesis of Silver Nanoparticles and Its Photocatalytic Applications for Removal of Organic Pollutants in Water. Journal of Industrial and Engineering Chemistry 2019, 80, 247–257. [CrossRef]

- Melkamu, W.W.; Bitew, L.T. Green Synthesis of Silver Nanoparticles Using Hagenia Abyssinica (Bruce) J.F. Gmel Plant Leaf Extract and Their Antibacterial and Anti-Oxidant Activities. Heliyon 2021, 7, e08459. [CrossRef]

- Gopinath, K.P.; Madhav, N.V.; Krishnan, A.; Malolan, R.; Rangarajan, G. Present Applications of Titanium Dioxide for the Photocatalytic Removal of Pollutants from Water: A Review. Journal of Environmental Management 2020, 270, 110906. [CrossRef]

- A Novel and Facile Green Synthesis of SiO2 Nanoparticles for Removal of Toxic Water Pollutants | Applied Nanoscience Available online: https://link.springer.com/article/10.1007/s13204-021-01898-1 (accessed on 29 December 2023).

- Jadhav, S.A.; Garud, H.B.; Patil, A.H.; Patil, G.D.; Patil, C.R.; Dongale, T.D.; Patil, P.S. Recent Advancements in Silica Nanoparticles Based Technologies for Removal of Dyes from Water. Colloid and Interface Science Communications 2019, 30, 100181. [CrossRef]

- Bhateria, R.; Singh, R. A Review on Nanotechnological Application of Magnetic Iron Oxides for Heavy Metal Removal. Journal of Water Process Engineering 2019, 31, 100845. [CrossRef]

- Wang, J.; Zhang, J.; Han, L.; Wang, J.; Zhu, L.; Zeng, H. Graphene-Based Materials for Adsorptive Removal of Pollutants from Water and Underlying Interaction Mechanism. Advances in Colloid and Interface Science 2021, 289, 102360. [CrossRef]

- Yap, P.L.; Nine, M.J.; Hassan, K.; Tung, T.T.; Tran, D.N.H.; Losic, D. Graphene-Based Sorbents for Multipollutants Removal in Water: A Review of Recent Progress. Advanced Functional Materials 2021, 31, 2007356. [CrossRef]

- Sanjeev, N.O.; Valsan, A.E.; Zachariah, S.; Vasu, S.T. Synthesis of Zinc Oxide Nanoparticles from Azadirachta Indica Extract: A Sustainable and Cost-Effective Material for Wastewater Treatment. Journal of Hazardous, Toxic, and Radioactive Waste 2023, 27, 04023027. [CrossRef]

- Shabani, N.; Javadi, A.; Jafarizadeh-Malmiri, H.; Mirzaie, H.; Sadeghi, J. Potential Application of Iron Oxide Nanoparticles Synthesized by Co-Precipitation Technology as a Coagulant for Water Treatment in Settling Tanks. Mining, Metallurgy & Exploration 2021, 38, 269–276. [CrossRef]

- Bashir, A.; Malik, L.A.; Ahad, S.; Manzoor, T.; Bhat, M.A.; Dar, G.N.; Pandith, A.H. Removal of Heavy Metal Ions from Aqueous System by Ion-Exchange and Biosorption Methods. Environ Chem Lett 2019, 17, 729–754. [CrossRef]

- Ebrahimi, M.; Van der Bruggen, B.; Hosseini, S.M.; Askari, M.; Nemati, M. Improving Electrochemical Properties of Cation Exchange Membranes by Using Activated Carbon-Co-Chitosan Composite Nanoparticles in Water Deionization. Ionics 2019, 25, 1199–1214. [CrossRef]

- Hosseini, S.M.; Sohrabnejad, S.; Nabiyouni, G.; Jashni, E.; Van der Bruggen, B.; Ahmadi, A. Magnetic Cation Exchange Membrane Incorporated with Cobalt Ferrite Nanoparticles for Chromium Ions Removal via Electrodialysis. Journal of Membrane Science 2019, 583, 292–300. [CrossRef]

- Farahbakhsh, J.; Vatanpour, V.; Ganjali, M.R.; Saeb, M.R. 21 - Magnetic Nanoparticles in Wastewater Treatment. In Magnetic Nanoparticle-Based Hybrid Materials; Ehrmann, A., Nguyen, T.A., Ahmadi, M., Farmani, A., Nguyen-Tri, P., Eds.; Woodhead Publishing Series in Electronic and Optical Materials; Woodhead Publishing, 2021; pp. 547–589 ISBN 978-0-12-823688-8.

- Naseem, T.; Durrani, T. The Role of Some Important Metal Oxide Nanoparticles for Wastewater and Antibacterial Applications: A Review. Environmental Chemistry and Ecotoxicology 2021, 3, 59–75. [CrossRef]

- Jamzad, M. Green Synthesis of Iron Oxide Nanoparticles by the Aqueous Extract of Laurus Nobilis L. Leaves and Evaluation of the Antimicrobial Activity | SpringerLink Available online: https://link.springer.com/article/10.1007/s40097-020-00341-1 (accessed on 20 May 2023).

- Ying, S.; Guan, Z.; Ofoegbu, P.C.; Clubb, P.; Rico, C.; He, F.; Hong, J. Green Synthesis of Nanoparticles: Current Developments and Limitations. Environmental Technology & Innovation 2022, 26, 102336. [CrossRef]

- Mittal, A.K.; Chisti, Y.; Banerjee, U.C. Synthesis of Metallic Nanoparticles Using Plant Extracts. Biotechnology Advances 2013, 31, 346–356. [CrossRef]

- Manogar, P.; Esther Morvinyabesh, J.; Ramesh, P.; Dayana Jeyaleela, G.; Amalan, V.; Ajarem, J.S.; Allam, A.A.; Seong Khim, J.; Vijayakumar, N. Biosynthesis and Antimicrobial Activity of Aluminium Oxide Nanoparticles Using Lyngbya Majuscula Extract. Materials Letters 2022, 311, 131569. [CrossRef]

- Joudeh, N.; Linke, D. Nanoparticle Classification, Physicochemical Properties, Characterization, and Applications: A Comprehensive Review for Biologists. Journal of Nanobiotechnology 2022, 20, 262. [CrossRef]

- Das, P.; Das, M.K. Chapter 4 - Production and Physicochemical Characterization of Nanocosmeceuticals. In Nanocosmeceuticals; Das, M.K., Ed.; Academic Press, 2022; pp. 95–138 ISBN 978-0-323-91077-4.

- Petcharoen, K.; Sirivat, A. Synthesis and Characterization of Magnetite Nanoparticles via the Chemical Co-Precipitation Method. Materials Science and Engineering: B 2012, 177, 421–427. [CrossRef]

- Ali, M. Qualitative Analyses of Thin Film-Based Materials Validating New Structures of Atoms; 2023.

- Kim, M.; Singhvi, M.S.; Kim, B.S. Eco-Friendly and Rapid One-Step Fermentable Sugar Production from Raw Lignocellulosic Biomass Using Enzyme Mimicking Nanomaterials: A Novel Cost-Effective Approach to Biofuel Production. Chemical Engineering Journal 2023, 465, 142879. [CrossRef]

- Ghanbary, F.; Jafarnejad, E. Removal of Malachite Green from the Aqueous Solutions Using Polyimide Nanocomposite Containing Cerium Oxide as Adsorbent. Inorganic and Nano-Metal Chemistry 2017, 47. [CrossRef]

- Tkaczyk, A.; Mitrowska, K.; Posyniak, A. Synthetic Organic Dyes as Contaminants of the Aquatic Environment and Their Implications for Ecosystems: A Review. Science of The Total Environment 2020, 717, 137222. [CrossRef]

- Hammad, E.N.; Salem, S.S.; Mohamed, A.A.; El-Dougdoug, W. Environmental Impacts of Ecofriendly Iron Oxide Nanoparticles on Dyes Removal and Antibacterial Activity. Appl Biochem Biotechnol 2022, 194, 6053–6067. [CrossRef]

- Behera, S.K.; Sahni, S.; Tiwari, G.; Rai, A.; Mahanty, B.; Vinati, A.; Rene, E.R.; Pugazhendhi, A. Removal of Chromium from Synthetic Wastewater Using Modified Maghemite Nanoparticles. Applied Sciences 2020, 10, 3181. [CrossRef]

- Singh, N.; Riyajuddin, S.; Ghosh, K.; Mehta, S.K.; Dan, A. Chitosan-Graphene Oxide Hydrogels with Embedded Magnetic Iron Oxide Nanoparticles for Dye Removal. ACS Appl. Nano Mater. 2019, 2, 7379–7392. [CrossRef]

- Kedare, S.B.; Singh, R.P. Genesis and Development of DPPH Method of Antioxidant Assay. J Food Sci Technol 2011, 48, 412–422. [CrossRef]

- Singhvi, M.S.; Deshmukh, A.R.; Kim, B.S. Cellulase Mimicking Nanomaterial-Assisted Cellulose Hydrolysis for Enhanced Bioethanol Fermentation: An Emerging Sustainable Approach. Green Chem. 2021, 23, 5064–5081. [CrossRef]

- IR Spectrum Table Available online: https://www.sigmaaldrich.com/IN/en/technical-documents/technical-article/analytical-chemistry/photometry-and-reflectometry/ir-spectrum-table (accessed on 3 June 2023).

- Mourdikoudis, S.; M. Pallares, R.; K. Thanh, N.T. Characterization Techniques for Nanoparticles: Comparison and Complementarity upon Studying Nanoparticle Properties. Nanoscale 2018, 10, 12871–12934. [CrossRef]

- N. Thorat, M.; G. Dastager, S. High Yield Production of Cellulose by a Komagataeibacter Rhaeticus PG2 Strain Isolated from Pomegranate as a New Host. RSC Advances 2018, 8, 29797–29805. [CrossRef]

- Experimental Design, Modeling and Mechanism of Cationic Dyes Biosorption on to Magnetic Chitosan-Lutaraldehyde Composite - ScienceDirect Available online: https://www.sciencedirect.com/science/article/pii/S0141813019303010 (accessed on 28 March 2024).

- Rahmi; Ishmaturrahmi; Mustafa, I. Methylene Blue Removal from Water Using H2SO4 Crosslinked Magnetic Chitosan Nanocomposite Beads. Microchemical Journal 2019, 144, 397–402. [CrossRef]

- Azari, A.; Noorisepehr, M.; Dehghanifard, E.; Karimyan, K.; Hashemi, S.Y.; Kalhori, E.M.; Norouzi, R.; Agarwal, S.; Gupta, V.K. Experimental Design, Modeling and Mechanism of Cationic Dyes Biosorption on to Magnetic Chitosan-Lutaraldehyde Composite. International Journal of Biological Macromolecules 2019, 131, 633–645. [CrossRef]

- Burakov, A.E.; Galunin, E.V.; Burakova, I.V.; Kucherova, A.E.; Agarwal, S.; Tkachev, A.G.; Gupta, V.K. Adsorption of Heavy Metals on Conventional and Nanostructured Materials for Wastewater Treatment Purposes: A Review. Ecotoxicology and Environmental Safety 2018, 148, 702–712. [CrossRef]

- Naik, C.C.; Gaonkar, S.K.; Furtado, I.; Salker, A.V. Effect of Cu2+ Substitution on Structural, Magnetic and Dielectric Properties of Cobalt Ferrite with Its Enhanced Antimicrobial Property. J Mater Sci: Mater Electron 2018, 29, 14746–14761. [CrossRef]

- Abou Hammad, A.B.; Abd El-Aziz, M.E.; Hasanin, M.S.; Kamel, S. A Novel Electromagnetic Biodegradable Nanocomposite Based on Cellulose, Polyaniline, and Cobalt Ferrite Nanoparticles. Carbohydrate Polymers 2019, 216, 54–62. [CrossRef]

- Vitta, Y.; Figueroa, M.; Calderon, M.; Ciangherotti, C. Synthesis of Iron Nanoparticles from Aqueous Extract of Eucalyptus Robusta Sm and Evaluation of Antioxidant and Antimicrobial Activity. Materials Science for Energy Technologies 2020, 3, 97–103. [CrossRef]

- Ramanavičius, S.; Žalnėravičius, R.; Niaura, G.; Drabavičius, A.; Jagminas, A. Shell-Dependent Antimicrobial Efficiency of Cobalt Ferrite Nanoparticles. Nano-Structures & Nano-Objects 2018, 15, 40–47. [CrossRef]

| Microorganisms/ sample |

Antimicrobial activity [zone of inhibition (dia. in mm)] |

|

| 50 µL | 100 µL | |

| E. coli | 11 | 16.5 |

| S. aureus | 13.5 | 19 |

Disclaimer/Publisher’s Note: The statements, opinions and data contained in all publications are solely those of the individual author(s) and contributor(s) and not of MDPI and/or the editor(s). MDPI and/or the editor(s) disclaim responsibility for any injury to people or property resulting from any ideas, methods, instructions or products referred to in the content. |

© 2024 by the authors. Licensee MDPI, Basel, Switzerland. This article is an open access article distributed under the terms and conditions of the Creative Commons Attribution (CC BY) license (http://creativecommons.org/licenses/by/4.0/).