1. Introduction

White leg shrimp (

Litopenaeus vannamei) is being cultured in Vietnam with an annual production of 1.12 million tons in 2023 [

1]. Since the development of intensive and super-intensive farming systems, Vietnamese shrimp sector is facing issues such as disease outbreaks and increase of chemical use related to the increase in stocking density [

2]. Shrimp diseases are mainly due to pathogens such as viruses and bacteria, causing, e.g., acute hepatopancreatic necrosis disease (AHPND), white feces disease and white spot syndrome [

3,

4,

5]. In particular, diseases caused by

Vibrio spp. result in serious economic losses [

6,

7]. Several authors [

8,

9,

10] reported that shrimp farmers normally use antibiotics to manage shrimp health as well as prevent and treat bacterial infections.

Florfenicol (FF) is one of the antibiotics commonly used for the treatment of bacterial diseases in white leg shrimp and other aquaculture species [

9,

11,

12,

13]. FF is a broad-spectrum synthetic bacteriostatic antibiotic belonging to the phenicol group. The mode of action of FF is similar to that of chloramphenicol, acting through the inhibition of protein synthesis via binding to the S50 ribosomal subunit of the target microorganism, resulting in the prevention of protein chain elongation in bacterial cells, and the inhibition of bacterial growth [

14,

15,

16]. Since chloramphenicol is prohibited for use in aquaculture, FF is used as an alternative because FF does not have the potential side effects of chloramphenicol [

17]. FF is one of the antibiotics approved by the US Food and Drug Administration for aquaculture that has been shown to be effective in treating diseases caused by Gram-positive and Gram-negative bacteria in aquaculture and livestock [

18,

19,

20].

In aquaculture, FF pharmacokinetics (PK) were studied mostly in fish e.g. catfish [

21,

22,

23,

24], Atlantic salmon [

25,

26], lumpfish [

27], orange-spotted grouper [

28], cod [

29], crucian car [

30], olive flounder [

31], rainbow trout [

32,

33], Asian tilapia [

34] and seabass [

35]. The values of C

max (µg/mL) and T

max (h) in plasma of those fish species treated with a dose of 10 mg FF/kg bw by oral administration were as follows, catfish 0.34 and 3.7, Atlantic salmon 4.0 and 10.3, lumpfish 3.55 and 21.2, cod 10.8 and 7.0, rainbow trout 6.1 and 9.0, tilapia 4.46 and 12.0, respectively [

24,

25,

27,

29,

32,

34]. In contrast, PK studies of FF in shrimp are limited, e.g. FF PK was studied by Fang et al. [

36] and Ren et al. [

11] in white leg shrimp in China, and by Tipmongkolsilp et al. [

37] in black tiger shrimp in Thailand. However, PK parameters vary among shrimp species living in different locations or environments [

11,

36], for instance, after oral administration at the dose of 30 mg/kg bw, T

max value of FF in plasma of shrimp (

Exopalaemon carinicauda) at 28 °C (T

max of 0.5 h) was faster than that at 22 °C (T

max of 1 h), the corresponding values for shrimp hepatopancreas were 1 h and 2 h, respectively [

38]. In addition, PK parameters within a single fish species may differ due to factors like geographic origin and genetic variation caused by selective breeding and artificial selection [

39]. To figure out an effective therapeutic dose as well as interval time when using FF in shrimp aquaculture to be effective in treating bacterial infections, PK parameters are essential to establish and to compare with a pharmacodynamic (PD) parameter, namely the minimum inhibitory concentration (MIC) against the bacteria causing the disease, which called Pharmacokinetics/Pharmacodynamics (PK/PD) index. That may help to reduce antibiotic resistance of pathogens in shrimp farming. Hepatopancreas health (also called midgut gland) is one of the indicators which may be used to predict the health status of shrimp [

40]. Hepatopancreas of shrimp and other crustaceans is the most sensitive organ to drug and chemical exposure, several studies revealed that the improper use of antibiotics or chemicals has caused serious adverse effects on shrimp health, especially on sensitive organs like hepatopancreas. The higher the dose of antibiotics used, the more severe was the negative impact on shrimp hepatopancreas [

41,

42,

43,

44]. This evidence of negative effects on the hepatopancreas after excessive duration of treatments with certainly excessive doses should be a strong caution to shrimp farmers who have overused antibiotics or chemicals in shrimp aquaculture. Although FF is commonly used in shrimp culture, there has been no study on the side effects of FF on white leg shrimp hepatopancreas.

Based on the above evidence, research on PK, PD and withdrawal time of FF in shrimp should be conducted to figure out the influence of shrimp on FF, as well as to study the impact of using FF medicated feed on shrimp hepatopancreas to monitor the shrimp health and to ensure the safety of shrimp food products.

2. Materials and Methods

2.1. Chemicals and Equipment

High purity chemicals (> 98%) including FF standard and internal standard (penicillin V) were provided by Dr. Ehrenstorfer® (Augsburg, Germany). The instrument used for FF quantification was a Waters ACQUITY Ultra-High-Performance Liquid Chromatograph (UHPLC) (Waters, Milford, MA, USA) with an Acquity UPLC CSH C18 column, 2.1 mm × 50 mm, 1.7 μm (Waters, Milford, MA, USA). C18 Bondesil powder with a particle size of 40 μm was obtained from Agilent (Santa Clara, CA, USA). Other chemicals like acetonitrile, methanol and distilled water were purchased from Merck (Darmstadt, Germany).

2.2. Bacterial Strains

A total of 42 bacterial strains were used for antimicrobial tests. These strains were isolated from AHPND shrimps which were collected from shrimp farms located in 7 provinces of Mekong Delta including Ca Mau, Kien Giang, Soc Trang, Can Tho, Dong Thap, Tra Vinh and Tien Giang from 2022 and 2024. Strains were identified as Vibrio parahaemolyticus (V. parahaemolyticus) and stored at −80 °C in tryptone soy broth (TSB, Merck) containing 25% glycerol and supplemented with 1.5% (w/v) sodium chloride.

2.2.1. Antibiotic Susceptibility Testing

V. parahaemolyticus strains from glycerol stock were recovered by inoculating into tryptic soy agar supplemented with 1.5% NaCl (TSA+) and incubated at 28 °C for 18 h. Color and shape of colonies were recorded, Gram stain was applied to check the purity of bacteria. Pure bacterial colonies were cultured to increase the biomass in nutrient broth at 28 °C for 24 h and the concentration of bacteria was adjusted to an approximate density of 106 CFU/mL by using McFarland´s 0.5 Barium Sulfate Standard Solution (Sotomayor et al., 2019).

The resistance of

V. parahaemolyticus to FF was determined by an agar disk diffusion method as described by Balouiri et al. [

45] and Jiang et al. [

46], with some modifications. Disks containing 30 micrograms of FF were used. One hundred microliters of bacterial suspension were evenly spread over the surface of the TSA

+ plate. After 15 min, an FF disk was gently fixed into agar surface using a sterile fine-pointed forceps to ensure complete contact and the plate was incubated at 28 °C for 24 h. The diameters of the inhibition zones (as judged by the unaided eye), including the diameter of the disk was measured and the size of the clear zone of inhibition was used to classify isolates as susceptible, intermediate, or resistant according to guideline of Clinical and Laboratory Standards Institute (CLSI) [

47].

2.2.2. Determination of the Minimum Inhibitory Concentration (MIC) of FF

The bacteria were activated as described above. The MIC of FF was determined for each

V. parahaemolyticus strain using the broth macro dilution method with some modifications [

48]. An FF standard solution with a final concentration of 1280 μg/100 μL was prepared using sterile distilled water. Serial dilutions were then prepared to obtain 12 decreasing concentrations. The bacterial suspension (1 mL) was 200-fold diluted with TSB

+ medium. Fourteen sterilized screwed capped test tubes were prepared and labelled, which were then loaded with 4.9 mL of diluted bacterial suspension. After that, 100 µL prepared FF standard solutions was added to achieve a final concentration of 256, 128, 64, 32, 16, 8, 4, 2, 1, 0.5, 0.25, and 0.125 μg/mL. Simultaneously, one positive control tube (TSB

+ solution with bacterial) and one negative control tube (TSB

+ solution without bacterial) were also prepared. All these test tubes were incubated for 24 h at 28 °C. MIC was defined as the lowest concentration of FF that shows no visible bacterial growth.

2.3. Shrimp

Healthy white leg shrimps (10-15 g/shrimp) were provided by the Faculty of Marine Science and Technology, College of Aquaculture and Fisheries, Can Tho University. Shrimp were reared from post-larval stage, with no antibiotic use before starting the experiment. Shrimp were stocked and acclimated in 2 m3 tanks at a stocking density of 100 shrimps/m3 for one week prior the start of the experiment. During acclimation, shrimps were fed commercial pellet feed (40% crude protein, Proconco, Vietnam) four times daily (6:00, 10:00, 14:00, and 18:00 h) with an amount accounting for 3% of shrimps’ body weight. After 30 min of feeding, the remaining feed (less than 5% of the total feed amount) was removed from tanks by siphoning at each feeding time. In addition, experimental tanks were equipped with recirculation and aeration to maintain an oxygen level above 5 mg/L. Water quality parameters were measured and controlled to ensure the shrimps health, e.g. water salinity (adjusted at 10‰), alkalinity (adjusted at 140-160 mg HCO3-/L), and other parameters like water temperature, pH, nitrite were also monitored and maintaining in the optimal range of shrimp culture.

Vime-fenfish 2000 (containing 20% FF) was purchased from Vemedim company, Can Tho city, Vietnam. Before the experiment, the absence of FF residues in shrimps and the actual concentration of FF in the chemical product were confirmed by liquid chromatography coupled with tandem mass spectrometry analysis (LC–MS/MS).

2.4. Pharmacokinetics Experiment

The experiment was performed as described in Huynh et al. [

49]. White leg shrimp were stocked and acclimated in 6 tanks (corresponding to 6 replicates). Shrimp were fed a single dose of 10 mg FF/kg bw. The applied dose was selected based on the usual therapeutic dose recommended by the manufacturers of commercial products. Also, in a survey on antibiotic use in shrimp farming in Vietnam, farmers reported using FF at 10 mg/kg bw [

12]. Besides, this dose was used in previous studies to control susceptible bacterial infections in aquatic animals [

24,

36]. The concentration of FF in feed was calculated based on the amount of feed fed to 1 kg of shrimp biomass. Before every medication, FF medicated pellet feed was prepared manually by mixing FF 20% into the feed to obtain the dose of 1333 mg FF/kg feed (mixing by shaking well antibiotic and feed in a cylinder box for 5 min). The medicated feed was then coated with 2% fish oil and allowed to dry for 15 min before shrimp feeding at 6:00 h. At the other feeding times (10:00, 14:00 and 18:00 h), shrimp were fed feed without FF. After administration, plasma, muscle and hepatopancreas of shrimp were sampled at 0.5, 1, 2, 4, 8, 12 and 24 hours. Three shrimps were collected from one tank at each sampling time. The blood samples (about 0.5 mL/shrimp) were collected from the pericardial cavity of shrimps using a 1 mL syringe soaked with anti-coagulation solution (EDTA 0.01 M, NaCl 0.338 M, glucose 0.115 M, trisodium citrate dihydrate 0.03 M). Blood samples from 3 shrimps in one tank were pooled, placed into 1.5 mL centrifuge tubes, thereafter the plasma was collected by centrifugation at 9500 g for five min. Meanwhile, hepatopancreas and muscle of three shrimps were collected and pooled into marked plastic bags to make one replicate. All samples of plasma, muscle and hepatopancreas were frozen and stored at −80 °C until further analysis.

2.5. Depletion of Florfenicol in Muscle Tissue and Hepatopancreas Histological Observation

Depletion of FF in white leg shrimp was performed following oral administration. The experiment was conducted in 2 groups (three tanks per group, corresponding to triplicate). Shrimp were fed medicated pellet feed (prepared as described above) at the dose of 10 mg FF/kg bw once a day, at 6:00 h (group 1) and twice a day at 6:00 and 18:00 h (group 2) for three consecutive days. After these 3 days, feed without FF was provided for 21 days, four times daily, at 6:00, 10:00, 14:00, and 18:00 h. Shrimp were sampled at day 1 and day 3, one hour after feeding medicated feed. Sampling was continued after the last administration on days 1, 3, 7, 14 and 21. At each sampling time, 10 shrimps form each tank were randomly collected and shrimp muscles were minced, pooled, and preserved in a −80 °C freezer prior to extraction.

In addition, shrimp hepatopancreas was also checked through histology analysis to evaluate the impact of FF. Shrimp (3 individuals per tank) were collected one day before medication, one hour after the last dose of medication and 7 days after stopping medication. Shrimp hepatopancreas were preserved and processed in histological sections as described in Huynh et al. [

49]. A microscope (Novex, Arnhem, the Netherlands) was used to examine hepatopancreas histological sections. The B and F cell counts were determined as described by Nima et al. [

50] with some modifications, the number of these two cells were counted under the same microscopic field and different microscopic fields were randomly selected with 40 tubules for each shrimp. The difference between treatments and/or sampling times were assessed using one-way and two-way ANOVA with SPSS 20.0 software.

2.6. Florfenicol and Florfenicol Amine Quantification

FF and florfenicol amine (FFA) in shrimp plasma were extracted and analyzed using a modified version of the procedure described by Pham et al. [

24]. In brief, 0.5 mL of plasma was spiked with penicillin V solution as an internal standard (IS) and mixed with 3 mL of acetonitrile. The mixture was then centrifuged at 9503 g for 10 min, the supernatant was collected, dried under nitrogen, and the dry residue was dissolved in the mobile phase. Before LC–MS/MS injection, the extract was filtered through a 0.22 μm nylon membrane filter (Advantec MFS, CA, USA).

Hepatopancreas and muscle samples were separately homogenized using an Ultra Turrax homogenizer (T-25, IKA, China). The extraction method was adapted from the United States Department of Agriculture (USDA) [

51] with some modifications. Briefly, 3.00 ± 0.1 g of homogenized sample was transferred into a 50 mL tube, spiked with 60 μL of 1 μg/mL IS, vortexed, and incubated at room temperature for 15 min. After incubation, 1 mL of 0.1 M phosphate buffer (pH 8.0) was added to the tube, which was vortexed for 1 min, followed by the addition of 20 mL of acetonitrile. The mixture was vortexed for 30 sec and sonicated for 15 min in an Elma Ultrasonic bath (Elma Hans Schmidbauer, Singen, Germany). Samples were then centrifuged (22R, Andreas Hettich, Tuttlinggen, Germany) at 3501 g for 5 min to collect supernatant. Acetonitrile was added to adjust the final volume to 24 mL, then 8 mL was transferred to a 15 mL glass test tube containing 40 mg Bondesil C18 and vortexed for 20 min. After centrifugation at 3501 g for 4 min, the supernatant was collected into a 10 mL glass test tube and then evaporated at 40 ± 1 °C in a water bath under nitrogen flow. The dried residues were reconstituted in 1 mL of mobile phase [acetonitrile and methanol (1:1) with 0.1% formic acid in water], filtered through a 0.22 μm nylon membrane filter (Advantec MFS, CA, USA) and injected into the LC–MS/MS system.

Detection and quantification of FFA and FF were performed using a Xevo TQ-S triple quadrupole mass spectrometer (Waters) equipped with an electrospray ionization (ESI) probe. The ESI probe operated in positive ion mode for FFA detection and in negative ion mode for FF. Optimizing mass spectrometry parameters including capillary voltage, ion source temperature, cone gas flow, desolvation gas flow, and desolvation temperature. Argon was used as the collision gas, and the collision cell pressure was 4 × 10-3 mBar. For quantitation (shown in bold) and confirmation, the following two specific fragmentation transitions (precursor > product ion, m/z) were used, with collision energy shown in brackets: FF 355.97 > 184.94 (24 eV) and 355.97 > 335.99 (14 eV); FFA 248.07 > 130.21 (24 eV) and 248.07> 91.07 (44 eV); penicillin V (IS) 351.04 > 229.09 (18 eV) and 351.04.1 > 257.04 (14 eV).

The limits of detection (LOD) were 2.5 μg/kg for FF and 5 μg/kg for FFA in all matrices, while the limits of quantification (LOQ) were 5 and 10 μg/kg, respectively. The working ranges of standard calibration curve, prepared using blank samples, exhibited a linear range of 5–80 μg/kg for FF and 10–80 μg/kg for FFA. Extraction recovery ranged from 92% to 99%. Linearity, specificity, precision (repeatability and within-laboratory reproducibility), apparent recovery, decision limit (CC

α) and detection capability (CC

β) were evaluated and validated according to Commission Decision 2002/657/EC [

52]. All parameters fell within the acceptance criteria.

2.7. Pharmacokinetics Data Analysis

FF concentrations in plasma, hepatopancreas and muscle tissue were modelled using a naïve pooled population approach based on a one-compartmental model with first order absorption and elimination. The following PK parameters were calculated for plasma: absorption rate constant (ka), absorption half-life (T1/2abs), maximal plasma concentration (Cmax), time to maximal plasma concentration (Tmax), area under the plasma concentration−time curve from time 0 to infinity (AUC0−inf), elimination rate constant (kel), elimination half-life (T1/2el), apparent total body clearance after oral administration (Cl) and apparent volume of distribution after oral administration (Vd).

Regarding hepatopancreas and muscle tissues, the following PK parameters were calculated: maximal tissue concentration (Cmax), time to maximal tissue concentration (Tmax), area under the tissue concentration–time curve from time 0 to infinity (AUC0–inf), which was computed using the linear-up log-down trapezoidal method. All data were processed using Phoenix 8 (Certara, Princeton, NJ, USA).

2.8. Withdrawal Times Calculation

The withdrawal time (WT) of FF was estimated according to European Medicine Agency guidelines (EMA) [

53], using the statistical software WT 1.4, developed by Hekman [

54]. The concentration of FF in muscle tissue was measured at various time points post-treatment and analyzed using linear regression against time (degree-days). Degree-days were calculated by multiplying the average daily water temperature (°C) by the total number of days the temperature was measured. The withdrawal period was determined at the time when the upper one-sided 95% tolerance limit for the FF residue concentration fell below the MRL (100 µg/kg set by EU and Korea) with 95% confidence.

3. Results

3.1. Antimicrobial Activity

Disk diffusion tests. The antimicrobial activity of FF towards 42

V. parahaemolyticus strains, evaluated by the disk diffusion method (30 µg FF disk), expressed as inhibition zone diameters, were 6 to 36 mm for strains collected in Ca Mau, 22 to 26 mm for strains coming from Kien Giang, 18-36 mm (Soc Trang), 24-25 mm (Can Tho), 30 mm (Dong Thap), 25-28 mm (Tra Vinh), 25-28 mm (Tien Giang) (

Table 1).

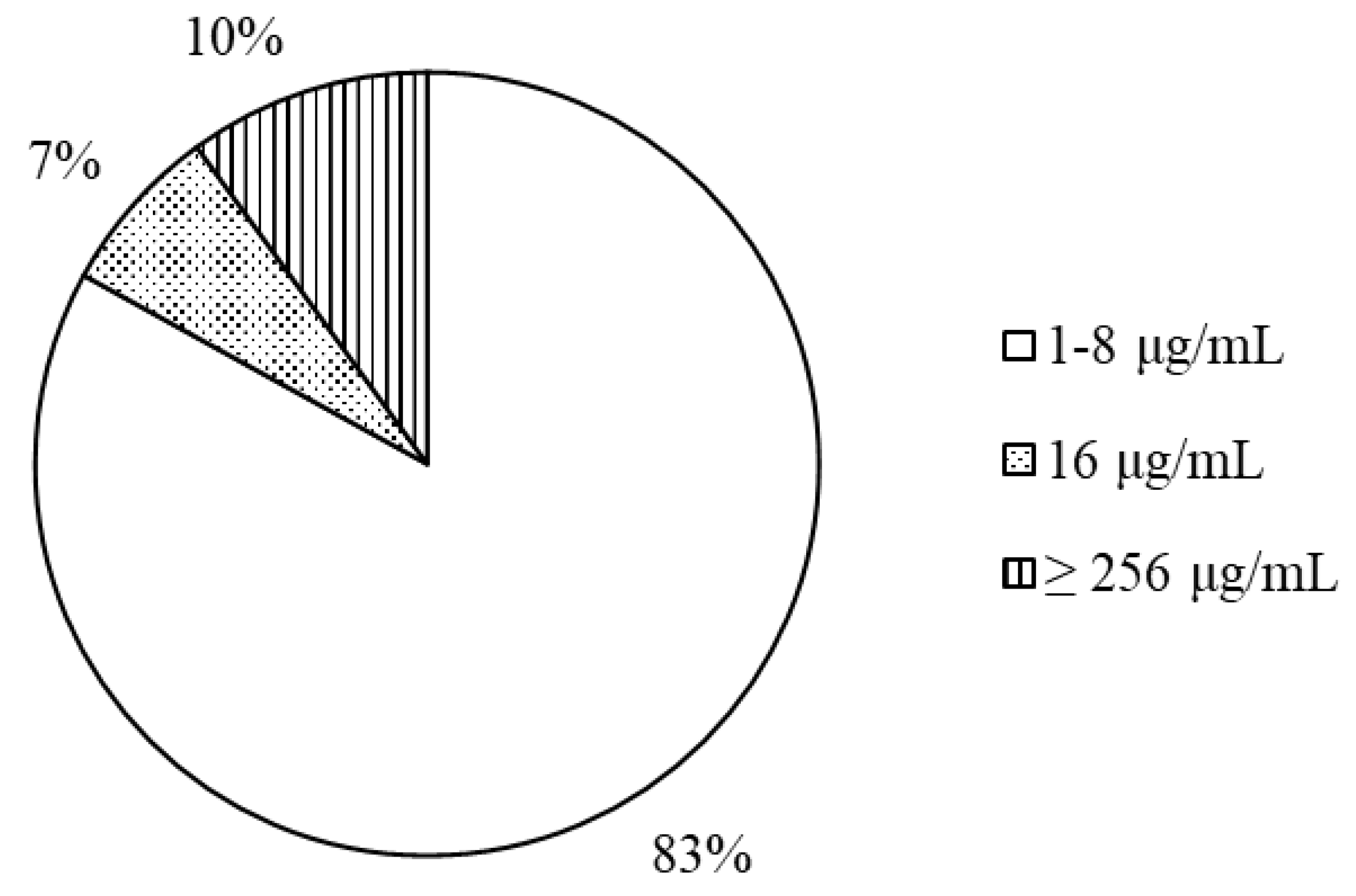

Minimum inhibitory concentration. Figure 1 shows the repartition of MIC values of FF for 42

V. parahaemolyticus strains isolated from 7 provinces of the Mekong Delta, Vietnam. For thirty-five strains of

V. parahaemolyticus (83.3%), the FF MIC was ranging between 1 to 8 µg/mL. For approximately 7% (3/42 strains) of

V. parahaemolyticus tested strains, the FF MIC was 16 µg/mL and for four strains (about 10%), FF MIC was above 256 µg/mL (

Figure 1). In Ca Mau province (isolates 1–17), 5/18 isolates had MIC values ranging above 8 µg/mL while 2/10 isolates from Soc Trang province (

Table 1).

3.2. Pharmacokinetics of Florfenicol in Plasma, Hepatopancreas and Muscle of White Leg Shrimp

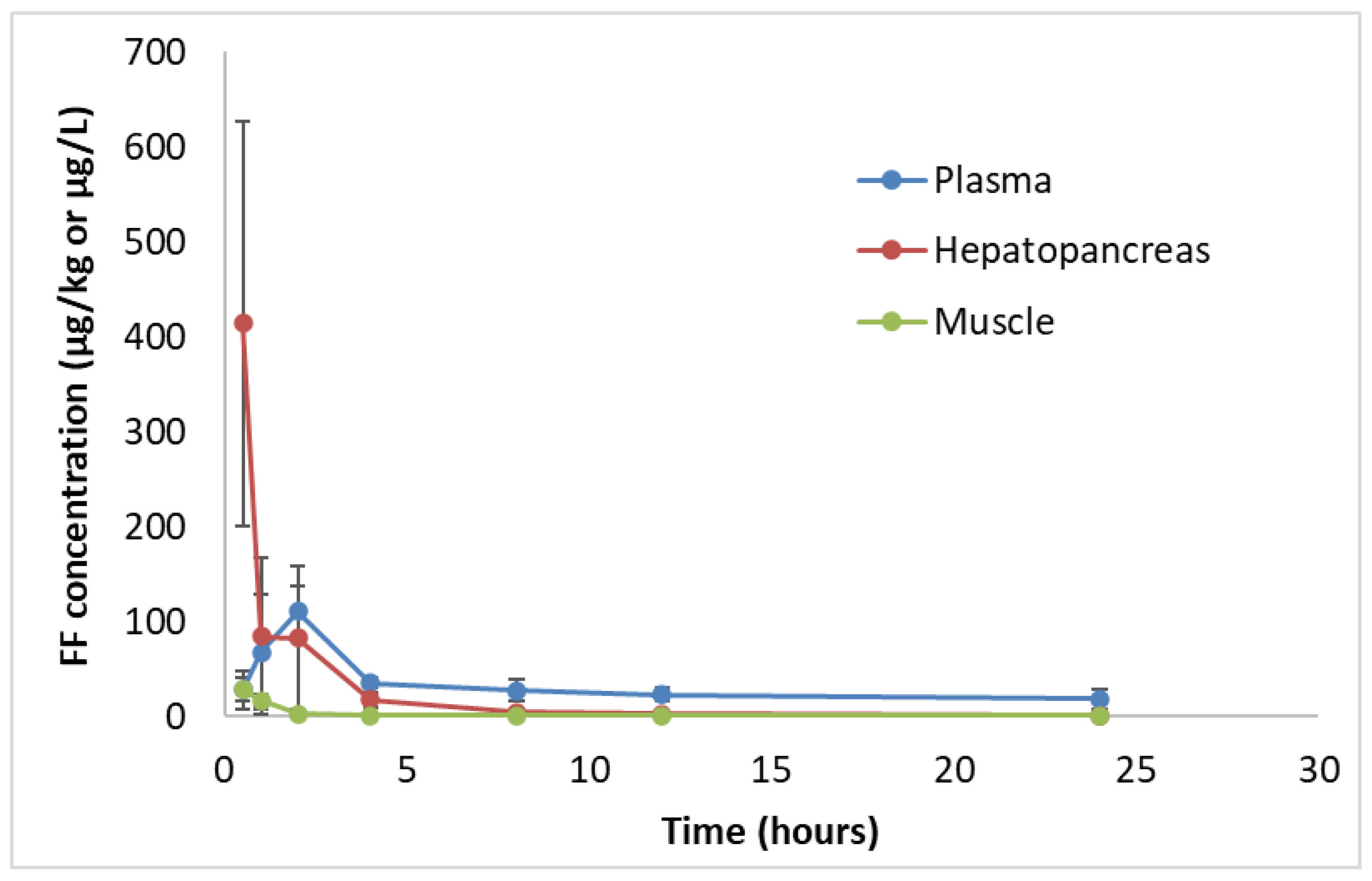

The concentration-time curves of FF in white leg shrimp plasma, hepatopancreas and muscle after oral administration of a single dose of 10 mg FF/kg bw showed that the FF levels in shrimp hepatopancreas were much higher than in plasma and in muscle at 30 min after FF ingestion (

Figure 2).

The estimated PK parameters of FF in white leg shrimp plasma were determined by a one-compartment model. The results are shown in

Table 2. The absorption rate constant (k

a) is 0.066 h

-1, the absorption half-life (T

1/2abs) is 10.44 h, the maximal plasma concentration (C

max) is 60.56 µg/L, the time to reach the maximal plasma concentration (T

max) is 1.77 h, the total body clearance uncorrected for oral bioavailability (Cl) is 9.75 L/kg/h, the volume of distribution uncorrected for oral bioavailability (V

d) is 4.93 L/kg, the area under the plasma concentration–time curve from time 0 to infinity (AUC

0–inf) is 1026.07 µg.h/L, the elimination rate constant (k

el) is 1.97 h

-1 and the elimination half-life (T

1/2el) is 0.35 h.

Regarding the estimated PK parameters of FF in white leg shrimp tissues, results showed that the concentration of FF in shrimp hepatopancreas was much higher than in muscle (

Table 3). The maximum hepatopancreas concentration (C

max) of FF was 386.92 µg/kg, while C

max in shrimp muscle was only 11.76 µg/kg. Based on AUC

0–inf values, the distribution of FF in shrimp hepatopancreas was much higher than that in shrimp muscle, 1660 and 88.0 µg.h/kg, respectively. In addition, T

max values for these two organs were similar, approximately 0.2 h. However, T

max value of hepatopancreas could not be accurately estimated because of the high standard deviation of FF concentrations in this organ (

Figure 2).

Florfenicol amine, a metabolite of FF, was not detected in plasma, muscle or hepatopancreas of shrimp.

3.3. Depletion and Withdrawal Time of Florfenicol in White Leg Shrimp Muscle

The residual levels of FF in white leg shrimp muscle of both once a day and twice a day treatments were very low. The mean FF concentrations in shrimp muscle were 3.65 µg/kg for once-a-day treatment and 20.53 µg/kg for twice-a-day treatment on the first day of medication. After that, FF levels of shrimp muscle increased and reached the highest mean concentration on day 3 of medication, 9.35 and 49.29 µg/kg in once-a-day and twice-a-day treatment, respectively. FF concentrations in shrimp muscle were eliminated very quickly, the FF residual level got below LOQ (5 µg/kg) at 24 h post-medication and lower than LOD (2.5 µg/kg) from day 3 after stopping medication in both treatments of feeding shrimp with medicated feed once a day and twice a day (

Table 4). Florfenicol amine was not detected in all samples.

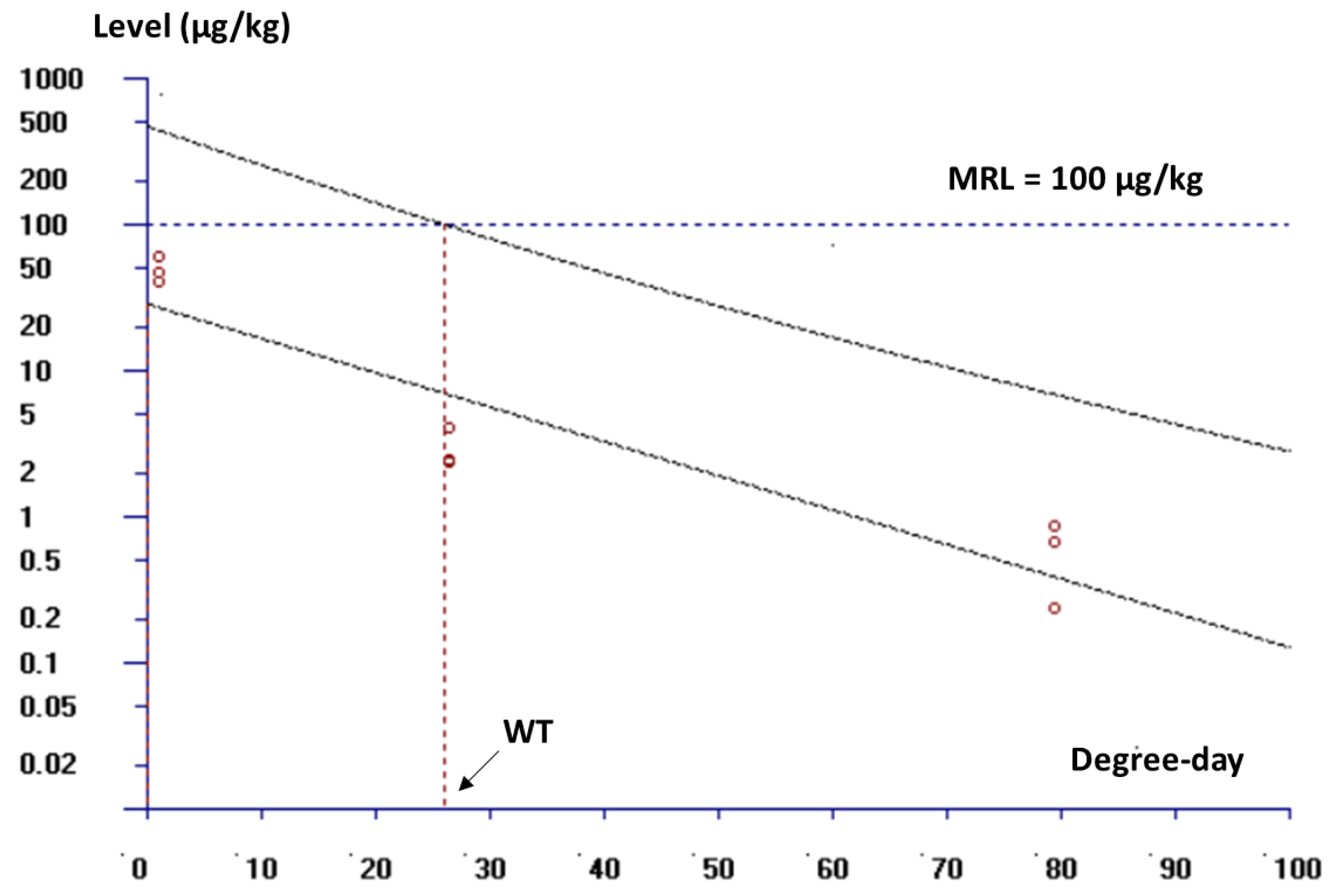

After three consecutive days of medications at the dose of 10 mg FF/kg bw once a day, and an ambient temperature of 26.5 °C, the FF residues in shrimp muscle were lower than the MRL of 100 µg/kg set by EU and Korea. The WT estimated only for FF administered twice a day, was 27.9 degree-days (less than 2 days at 26.5 °C) (

Figure 3).

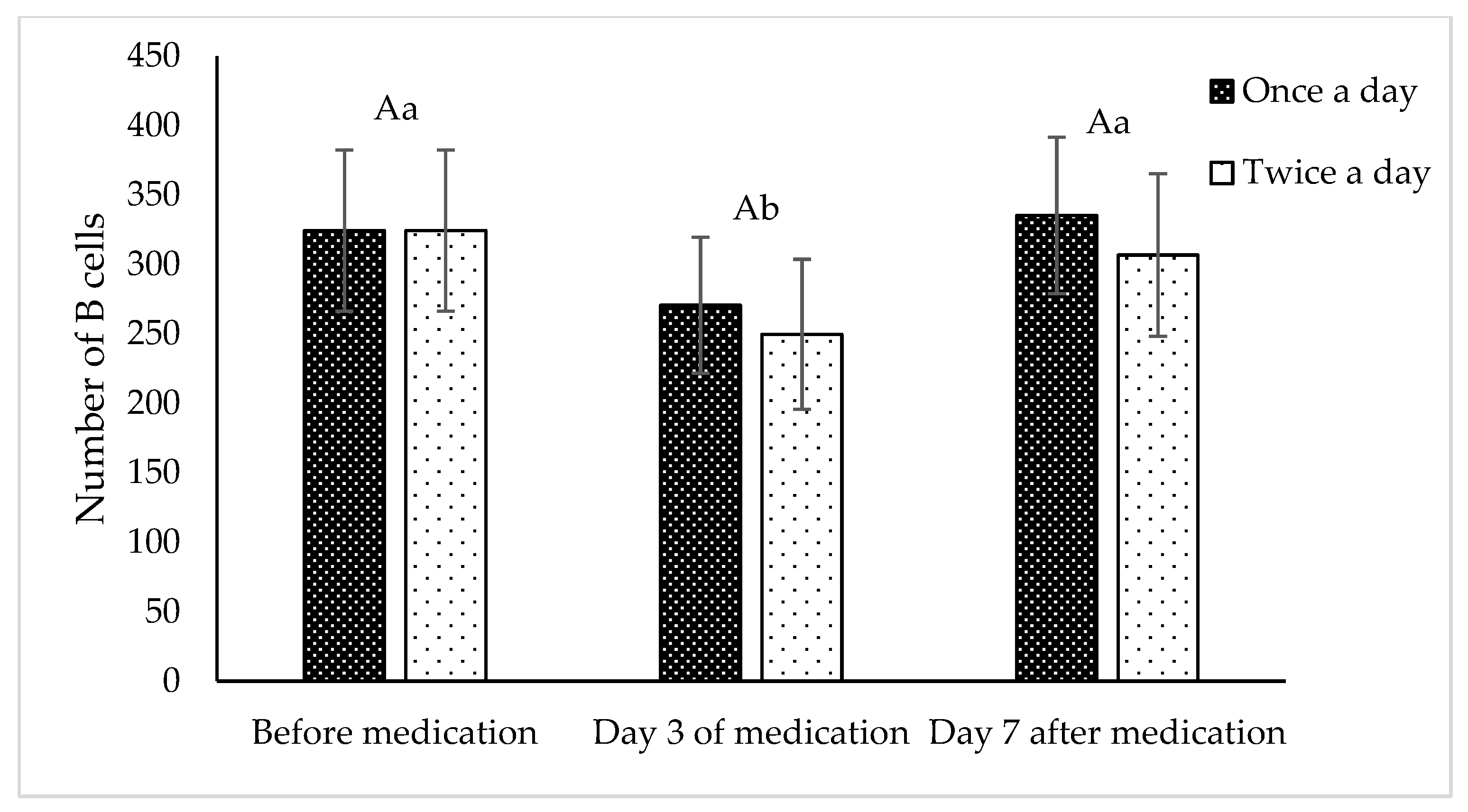

3.4. Hepatopancreas Histology of White Leg Shrimp

The hepatopancreas histology before medication was normal with a tissue structure displaying the full presence of B and F cells (

Figure 4A). After shrimp were fed with medicated feed twice a day for three consecutive days, the number of B cells decreased on day 3 of medication (

Figure 4B). In the

Figure 4C, the numbers of B cells in shrimp hepatopancreas were recovered on seven days after stopping medication (see also

Figure 5).

Results of the number hepatopancreas B cells after feeding shrimps with FF medicated feed once a day or twice a day for 3 consecutive days at the dose of 10 mg FF/kg bw are shown in

Figure 5. The statistical analysis showed no significant difference in the B cell counts between shrimps having received FF once a day or twice a day (p > 0.05). When considering the sampling time, it appeared that the hepatopancreas B cells were significantly lower in samples collected on the third-day of the medication than in those collected on day 7 after stopping medication or before medication (p < 0.05). Additionally, no interaction effect was observed between the doses applied and the sampling times on the numbers of B cells (p > 0.05).

There was no significant difference in the number of F cells between the applied doses (

Table 5), i.e. feeding shrimp with FF medicated feed once a day and twice a day (p > 0.05). Similarly, no significant different effect (p > 0.05) was found in F cell counts of shrimp across the different sampling times, i.e. there was no significant difference on day 3 of medication compared to before medication, and the similar trend was observed when comparing F cell numbers of shrimp before medication and on day 7 after medication was stopped (

Table 5). Similar to B cells, there was no interaction between the applied doses and the sampling times in the numbers of F cells (p > 0.05).

4. Discussion

4.1. Antimicrobial Activity of FF on Various V. parahaemolyticus Strains

When using an agar disk diffusion method, the susceptibility of a bacterial strain to an antibiotic can be classified as “susceptible”, “intermediate” and “resistant” according to the observed inhibition zone diameter, i.e., ≥ 18 mm, 13 – 17 mm and ≤ 12 mm, respectively [

46,

47]. In this study, all tested

V. parahaemolyticus strains were susceptible (≥ 18 mm) to FF, except for 1 strain with an inhibition zone diameter of 6 mm. Regarding the MIC test, the results were also varied among strains. These results illustrated that the strains of

V. parahaemolyticus collected from different locations possess different levels of antibiotic susceptibility.

The low FF MIC values in this study were in accordance with FF MIC values against

Vibrio spp. isolated from shrimp diseases in other studies. For example, FF MIC values were reported between 0.5 and 4 µg/mL in Ecuador, USA, Japan and Thailand [

37,

55], from 0.25 to 8 μg/mL in Mexico [

56], and 8 µg/mL in Ecuador by other authors [

57]. In addition, the MIC values of FF in this study were low when compared to other antibiotics MIC values towards

V. parahaemolyticus strains isolated from shrimp, with MICs for oxytetracycline, chloramphenicol, ampicillin and kanamycin of 54.5 to 88.6 µg/mL, 29.8 to 43.4 µg/mL, 89.5 to 126.6 µg/mL and 21.5 to 28.9 µg/mL, respectively [

58]. Rebouças et al. [

59] reported a MIC value of 400 µg/mL for oxytetracycline against

Vibrio spp. strains. FF seems to be more effective than other antibiotics with similar bioavailability. Indeed, Rebouças et al. [

59] showed using a disk diffusion method, that 31 strains of

Vibrio spp. isolated from shrimp hepatopancreas and hatchery water exhibited intermediate resistance to ampicillin, aztreonam, gentamicin, imipenem, oxytetracycline and cefoxitin, whereas FF was effective against all

Vibrio isolates

Previous studies revealed that most strains of

V. parahaemolyticus isolated from samples and environment are usually resistant to many antibiotics such as amoxicillin, ampicillin, carbenicillin, colistin, gentamicin and tobramycin, as well as cefazolin, ceftazidime, cephalothin belonging to the cephalosporin group [

60,

61,

62,

63]. In the study of Tran et al. [

64] pathogenic

V. parahaemolyticus strains isolated from seafood and water samples showed high resistance to streptomycin 10 µg (84.6%), ampicillin 10 µg (57.7%) and sulfisoxazole 250 µg (57.7%). In the study of Rocha et al. [

65] on shrimp farming in Northeastern Brazil, antibiotic sensitivity test on 70 strains of

Vibrio isolated from water and sediment exhibited intermediate resistance to ampicillin, aztreonam, cephalothin, ceftriaxone and cefotaxime. In another study on the resistance of

V. parahaemolyticus isolated from shrimp samples in Malaysia,

V. parahaemolyticus isolates were resistant to some antibiotics, i.e., amikacin (26.7%), tetracycline (36.6%), ceftazidime (46.7%), cefepime (50%), cefotaxime (60%), amoxicillin-clavulanic acid (63.3%), ampicillin (90%) [

66].

Generally, the results of this study showed that

V. parahaemolyticus strains were susceptible towards FF. That explains that this antibiotic is widely used in shrimp aquaculture to treat bacterial diseases, like necrotizing hepatopancreatitis [

67]. However, antimicrobial activity of FF should be evaluated regularly since this antibiotic is applied widely for shrimp disease treatment.

4.2. Pharmacokinetics of FF in Shrimp

The concentration of FF in the hepatopancreas was much higher than that in plasma and muscle, and the order was hepatopancreas > plasma > muscle. This is similar to what was shown in the study of Fang et al. [

36], Ren et al. [

11] and Feng et al. [

38], who showed shrimp hepatopancreas had the highest FF concentration. The antibiotics were absorbed directly from the shrimp stomach to the hepatopancreas after oral administration [

11,

68]. According to Verri et al. [

69] and Faroongsarng et al. [

70], the hepatopancreas plays a role in metabolism and excretion of antibiotics in crustaceans. T

max values of shrimp organs in the current study were shorter than those in the study of Fang et al. [

36] following a single dose of 10 mg FF/kg bw in white leg shrimp by gavage feeding. The same authors reported C

max values in hepatopancreas, plasma and muscle of 164.22 μg/g, 5.53 μg/mL and 1.91 μg/g, respectively, and AUC

0-inf values for corresponding organs of 871.73 mg.h/kg, 41.27 mg.h/L and 15.97 mg.h/kg, respectively. These C

max and AUC

0-inf values were much higher than those in the present study. Feng et al. [

38] compared shrimp FF treatment by intramuscular injection and oral routes, and showed that FF concentrations in plasma and tissues after oral administration were several times lower compared to those observed after FF intramuscular injection. However, the method of using antibiotics through feed (oral administration) is a commonly applied method in aquaculture in Vietnam.

After absorption and distribution, it will undergo elimination from the shrimp body. FF levels were rapidly eliminated in white leg shrimp plasma with a T

1/2el value of 0.35 h and an apparent total body clearance of 9.75 L/kg/h. The absorption rate of antibiotics depends heavily on water temperature, the higher the water temperature, the more rapid T

max is reached [

30,

38]. For instance, in the current study, T

max value (1.77 h) in shrimp plasma at 26.5 °C was longer than that at 28 °C (0.5 h) [

38]. There was evidence that drug absorption also depends on physiological differences between species, specifically the structure of the intestine and the species-specific response to environmental factors [

27]. For example, at the same applied dose (10 mg FF/kg bw), T

max value in plasma of striped catfish was 3.70 h [

24], while in the present study, T

max value in shrimp plasma was 1.77 h. In addition, the PK parameters vary between different antibiotics, and according to mode of drug administration, organ measurement as well as used dosage (

Table 6).

FF is classified into the group of time-dependent antibiotic [

76], which follow the time-dependent killing pattern and according to Reed [

77], these antibiotics effectiveness is dependent on the duration of pathogen exposure to an antibiotic). The time during which the tissue concentration exceeds the MIC (T > MIC) against a bacteria should be considered as a predictor of efficacy against the corresponding target bacteria. The therapeutic dose should be calculated to maintain the concentrations higher than the MIC towards the targeted bacterial strain. According to AliAbadi and Lees [

78], for time-dependent antimicrobials, the T > MIC criteria should be used and the value must be in the range of 40% to 50% of dosing interval to get the efficiency of a treatment. In this study, C

max value in shrimp plasma was 60.56 µg/L (

Table 2) and much lower than MIC values of FF towards

V. parahaemolyticus (

Table 1). In theory, this means that AHPND caused by

V. parahaemolyticus in white leg shrimp may not be treatable with a single dose of 10 mg FF/kg bw. Therefore, it is necessary to test higher doses of FF to achieve the desired FF concentration in plasma or hepatopancreas.

4.3. Depletion of Florfenicol in White Leg Shrimp Muscle

Florfenicol residues were rapidly eliminated in shrimp muscle and became undetectable within 24 h after stopping medication, in both treatment frequencies (once a day and twice a day). The withdrawal time, which is defined as the time required to eliminate drug residues from edible tissue to a safe level for human consumption [

44] was determined considering a maximum residue limit which is 100 µg/kg for the sum of FF and FFA established by the European Commission [

79] and Korean Ministry of Food and Drug Safety [

80]. In this study, WT was estimated only for the twice a day treatment, and was 27.9 degree-days (less than 2 days at 26.5 °C). Although research on FF depletion has been performed in many fish species, those studies are limited for crustacean. When comparing with fish, quick depletion of FF in shrimp muscle seen in this study is similar to the observations in the study of Pham et al. [

24] performed on stripped catfish with the same dosage. It is not the same for Asian seabass, as FF residual level and WT of shrimp muscle was much lower than those reported by Rairat et al. [

81] on Asian seabass, where muscle FF concentration was 0.28 μg/g on day 4 and 0.15 μg/g on day 10 after the last FF oral dose, and the WT was estimated up to 8 days at 25 °C (approximately 204 degree-day). Besides the species, the difference may be due to the administration dose and the temperature, 10 mg/kg and 26.5 °C (in this study) compared with 15 mg/kg and 25 °C, in the study of Rairat et al. [

81]. The effect of temperature on depletion was also found in a study performed on tilapia, where the WT of FF at 22 °C was longer than that at 28 °C [

82].

The depletion and WT of antibiotics from shrimp muscles depends on the type and the dose of the applied antibiotic. FF depletion and WT in this study (administered at the dose of 1.3 g/kg feed for 3 consecutive days) were lower than those of other antibiotics in white leg shrimp, e.g. oxytetracycline (administered at the dose of 4.5 g/kg feed for 14 consecutive days, the WT was 96 h at 29 °C) [

44], chloramphenicol, sulfamethoxazole (administered at the dose of 2 g/kg feed for 3 consecutive days, the WT at 24 °C were 139.7 h and 30.6 h, respectively) [

83]. Rapid depletion of FF is consistent with the results of Huynh et al. [

49] on cefotaxime administered to shrimp at 25 mg/kg bw for 3 consecutive days, the cefotaxime concentration in white leg shrimp muscle was below LOD after stopping medication for 24 h.

Generally, quick depletion of FF in shrimp muscle resulted in a short withdrawal time, suggesting that the health risk for humans consuming white leg shrimp treated with 10 mg FF/kg bw can be considered as negligible.

4.4. Impact on Shrimp Hepatopancreas Histology

Hepatopancreas has been investigated by histologists and biologists for more than one century [

84]. Hepatopancreas of shrimp is constituted of many tubules, the tubule walls are composed of simple epithelium, containing four main types of cells namely E cells (embryonalzellen), F cells (fibrillenzellen), R cells (restzellen) and B cells (blasenzellen) [

85]. In this investigation, histology of the hepatopancreas was observed however, only B and F cells were subjected to cell number counting, because the growth rate of shrimp is decreased during antibiotic application (stated by shrimp famers), and growth rate is related to digestive function in shrimp hepatopancreas. Hu and Leung [

86] found that B and F cells have digestive functions in shrimp, i.e. F-cells synthesize digestive enzymes, stored in a single large vacuole and become B-cells; after that, the digestive enzymes are then released into the hepatopancreatic lumen through the holocrine secretion process from B-cells [

87]. Another reason is that the proportion of R cells in hepatopancreas of white leg shrimp was similar in both normal and growth-retarded shrimp, while the number of B cells was lower in growth-retarded shrimp [

50]. Under microscope, F-cells are very large with a cytoplasm noticeably metachromatic; B-cells are very prominent under light microscope with one or two very large vacuoles which are filled with a flocculent material and are usually so large that the nucleus is located to the periphery of the cell [

84,

87].

In the current study, there were no abnormalities signs in shrimp hepatopancreas histology during medication, and the cells of shrimp hepatopancreases had no negative impacts when using FF medicated feed at the dose of 10 mg FF/kg bw in both once a day and twice a day treatments. These results are similar to the one obtained in a previous study on white leg shrimp treated with cefotaxime of at 25 mg/kg bw, showing no negative impacts on shrimp hepatopancreas cells during medication [

49]. Regarding other antibiotics, several studies found negative effects on shrimp hepatopancreas histology, e.g. enrofloxacin [

43] or oxytetracycline [

41,

44], which were shown that the higher the dose of antibiotics used, the more serious the impact on hepatopancreas of shrimp.

5. Conclusions

This study showed a quick absorption and elimination of FF in plasma, hepatopancreas and muscle of white leg shrimp after FF once oral administration. The FF withdrawal time in shrimp muscle was 27.9 degree-days (2 days) for a MRL of 100 μg/kg, which will ensure the safety of shrimp products for consumers. Oral therapeutic of FF in shrimp slightly affects the histology of shrimp hepatopancreas during medication, but the organ structure recovered after 7 days of stopping medication. A study on dose increasing however should be considered to ensure the control of V. parahaemolyticus infection during shrimp culture.

Author Contributions

Conceptualization, T.K.D.H., Q.T.N., M.-L.S., M.D., S.C., C.D., T.H.O.D., Q.V.L. and M.P.T.; data curation, T.K.D.H., Q.T.N., M.-L.S., M.D., T.H.O.D. and M.P.T.; formal analysis, T.K.D.H., Q.T.N. and M.P.T.; investigation, T.K.D.H., Q.T.N., M.-L.S., C.D. and M.P.T.; methodology, T.K.D.H., Q.T.N., M.-L.S., M.D., S.C., C.D., T.H.O.D., Q.V.L. and M.P.T.; validation, T.K.D.H., Q.T.N., M.-L.S., M.D., S.C. and M.P.T.; visualization, T.K.D.H., Q.T.N., M.-L.S., M.D., S.C., C.D., T.H.O.D. and M.P.T.; supervision, M.-L.S., Q.T.N., C.D., T.H.O.D. and M.P.T.; writing—original draft, T.K.D.H., Q.T.N. and M.P.T.; writing—review and editing, T.K.D.H., Q.T.N., M.-L.S., T.H.O.D., S.C., M.D., C.D., Q.V.L. and M.P.T.; project administration and funding acquisition, M.-L.S. and M.P.T. All authors have read and agreed to the published version of the manuscript.

Funding

This research was funded by Wallonie-Bruxelles International (WBI), Project 6.1 “Reducing the antibiotic use in white leg shrimp aquaculture in the Mekong Delta, Vietnam”.

Institutional Review Board Statement

The animals used in this work were treated according to Decision No. 3965/QD-DHCT Date October 15 2021 “Can Tho University Regulation on Ethics in animal experimentation” URL:

https://dra.ctu.edu.vn/images/upload/news/246.pdf (accessed on 15 April 2025).

Informed Consent Statement

Not applicable.

Data Availability Statement

The data presented in this study are available from the first author.

Acknowledgments

We would like to thank the College of Aquaculture and Fisheries for facility support.

Conflicts of Interest

The authors all declare that they have no conflicts of interest.

Abbreviations

| AHPND |

Acute hepatopancreatic necrosis disease |

| AUC0−inf

|

Area under the plasma concentration−time curve from time 0 to infinity |

| Cl |

Total body clearance |

| Cmax

|

Maximum concentration |

| EMA |

European Medicine Agency guidelines |

| FF |

Florfenicol |

| IS |

Internal standard |

| kel

|

Elimination rate constant |

| MIC |

Minimum inhibitory concentration |

| MRL |

Maximum residue limit |

| PD |

Pharmacodynamics |

| PK |

Pharmacokinetic |

| PK/PD |

Pharmacokinetics/Pharmacodynamics |

| T1/2el

|

Elimination half-life |

| Tmax

|

Time to maximal plasma concentration |

| Vd

|

Volume of distribution |

| WT |

Withdrawal time |

References

- Vietnam Association of Seafood Exporters and Producers (VASEP). Vietnam Aquaculture and Fisheries Overview. 2024. Available online: https://vasep.com.vn/san-pham-xuat-khau/tom/tong-quan-nganh-tom (accessed on 20 Nov 2024).

- Nguyen, K.A.T.; Nguyen, T.A.T.; Jolly, C.; Nguelifack, B.M. Economic efficiency of extensive and intensive shrimp production under conditions of disease and natural disaster risks in Khánh Hòa and Trà Vinh Provinces, Vietnam. Sustainability 2020, 12(5), 2140. [CrossRef]

- Tran, L.; Nunan, L.; Redman, R.M.; Mohney, L.L.; Pantoja, C.R.; Fitzsimmons, K.; Lightner, D.V. Determination of the infectious nature of the agent of acute hepatopancreatic necrosis syndrome affecting penaeid shrimp. Dis. Aquat. Org. 2013, 105(1), 45-55. [CrossRef]

- Flegel, T.W.; Sritunyaluucksana, K. Recent research on acute hepatopancreatic necrosis disease (AHPND) and Enterocytozoon hepatopenaei in Thailand. A. F. S. 2018, 31, 257-269.

- Thinh, N.Q.; Maita, M.; Phu, T.M. Chemical use in intensive white-leg shrimp aquaculture in Tra Vinh province, Vietnam. Can Tho University J. Science 2020, 56, 70-77.

- Chanratchakool, P.; Phillips, M.J. Social and economic impacts and management of shrimp disease among small-scale farmers in Thailand and Viet Nam. FAO. Fish. Tech. Pap. 2002, 177-189.

- Zhou, J.; Fang, W.; Yang, X.; Zhou, S.; Hu, L.; Li, X.; Qi, X.; Su, H.; Xie, L.A nonluminescent and highly virulent Vibrio harveyi strain is associated with “bacterial white tail disease” of Litopenaeus vannamei shrimp. PloS one 2012, 7(2), e29961. [CrossRef]

- Rico, A.; Oliveira, R.; McDonough, S.; Matser, A.; Khatikarn, J.; Satapornvanit, K.; Nogueira, A.J.A.; Soares, A.M.V.M.; Domingues, I.; Van den Brink, P.J. Use, fate and ecological risks of antibiotics applied in tilapia cage farming in Thailand. Environ. Pollut. 2014, 191, 8–16. [CrossRef]

- Phu, T.M.; Phuong, N.T.; Dung, T.T.; Hai, D.M.; Son, V.N.; Rico, A.; Clausen, J.H.; Madsen, H.; Murray, F.; Dalsgaard, A. An evaluation of fish health-management practices and occupational health hazards associated with P angasius catfish (P angasianodon hypophthalmus) aquaculture in the M ekong D elta, V ietnam. Aquaculture Res. 2016, 47(9), 2778-2794. [CrossRef]

- Chi, T.T.K.; Clausen, J.H.; Van, P.T.; Tersbøl, B.; Dalsgaard, A. Use practices of antimicrobials and other compounds by shrimp and fish farmers in Northern Vietnam. Aquac. Rep. 2017, 7, 40–47. [CrossRef]

- Ren, X.; Pan, L.; Wang, L. Tissue distribution, elimination of florfenicol and its effect on metabolic enzymes and related genes expression in the white shrimp Litopenaeus vannamei following oral administration. Aquaculture Res. 2016, 47(5), 1584-1595. [CrossRef]

- Phu, T.M.; Vinh, P.Q.; Dao, N.L.A.; Viet, L.Q.; Thinh, N.Q. Chemical use in intensive white-leg shrimp aquaculture in Ben Tre province, Vietnam. Training 2019, 73, 46-7. [CrossRef]

- Lillehaug, A.; Børnes, C.; Grave, K. A pharmaco-epidemiological study of antibacterial treatments and bacterial diseases in Norwegian aquaculture from 2011 to 2016. Dis. Aquat. Org. 2018, 128(2), 117-125. [CrossRef]

- Wang, W.; Dai, X.; Li, Z.; Meng, Q. Tissue distribution and elimination of florfenicol in topmouth culter (Culter alburnus) after oral administration. Czech J. Food Sci. 2009, 27(3), 214-221.

- Lambert, T. Antibiotics that affect the ribosome. Rev. sci. tech. (International Office of Epizootics) 2012, 31(1), 57-64. [CrossRef]

- Nejad, A.J.; Peyghan, R.; Varzi, H.N.; Shahriyari, A. Florfenicol pharmacokinetics following intravenous and oral administrations and its elimination after oral and bath administrations in common carp (Cyprinus carpio). Vet. Res. Forum 2017, 8(4), 327-331.

- Dowling, P.M. Chloramphenicol, thiamphenicol and florfenicol. In S. Gigu`ere, J. F. Prescott, J. D. Baggot, R. D. Walker, and P. M. Dowling, editors. Antimicrobial therapy in veterinary medicine, 4th edition. Blackwell Scientific Publications, Ames, Iowa, 2006; pp. 241–248.

- Samuelsen, O.B.; Bergh, Ø. Efficacy of orally administered florfenicol and oxolinic acid for the treatment of vibriosis in cod (Gadus morhua). Aquaculture 2004, 235(1-4), 27-35. [CrossRef]

- Caipang, C.M.A.; Lazado, C.C.; Brinchmann, M.F.; Berg, I.; Kiron, V. In vivo modulation of immune response and antioxidant defense in Atlantic cod, Gadus morhua following oral administration of oxolinic acid and florfenicol. Comp. Biochem. Physiol. C: Toxicol. Pharmacol. 2009, 150(4), 459-464. [CrossRef]

- Huang, K.; Chen, S.J.; Huang, J.; Yang, L.; Ju, Y.; Zhu, X.R.; Peng, D.X. Analysis of antibiotic resistance of Salmonella isolated from animals and identification of its florfenicol resistant gene. China Animal Husbandry & Veterinary Medicine 2015, 42(2), 459-466.

- Park, B.K.; Lim, J.H.; Kim, M.S.; Yun, H.I. Pharmacokinetics of florfenicol and its metabolite, florfenicol amine, in the Korean catfish (Silurus asotus). J. Vet. Pharmacol. Ther. 2006, 29(1), 37-40. [CrossRef]

- Gaunt, P.S.; Langston, C.; Wrzesinski, C.; Gao, D.; Adams, P.; Crouch, L.; Sweeney, D.; Endris, R. Single intravenous and oral dose pharmacokinetics of florfenicol in the channel catfish (Ictalurus punctatus). J. Vet. Pharmacol. Ther. 2012, 35(5), 503-507. [CrossRef]

- Yang, Q.; Xie, L.; Wu, Z.; Chen, X.; Yang, Y.; Liu, J.; Zhang, Q. Pharmacokinetics of florfenicol after oral administration in yellow catfish, Pelteobagrus fulvidraco. J. World Aquac. Soc. 2013, 44(4), 586-592. [CrossRef]

- Pham, Q.V.; Nguyen, Q.T.; Devreese, M.; Croubels, S.; Dang, T.H.O.; Dalsgaard, A.; Maita, M.; Tran, M.P. Pharmacokinetics and depletion of florfenicol in striped catfish Pangasianodon hypophthalmus after oral administration. Fish. Sci. 2023, 89(3), 357-365. [CrossRef]

- Martinsen, B.; Horsberg, T.E.; Varma, K.J.; Sams, R. Single dose pharmacokinetic study of florfenicol in Atlantic salmon (Salmo salar) in seawater at 11 C. Aquaculture 1993, 112(1), 1-11. [CrossRef]

- Horsberg, T.E.; Hoff, K.A.; Nordmo, R. Pharmacokinetics of florfenicol and its metabolite florfenicol amine in Atlantic salmon. J. Aquat. Anim. Health 1996, 8(4), 292-301. [CrossRef]

- Kverme, K.O.; Haugland, G.T.; Hannisdal, R.; Kallekleiv, M.; Colquhoun, D.J.; Lunestad, B.T.; Wergeland, H.I.; Samuelsen, O.B. Pharmacokinetics of florfenicol in lumpfish (Cyclopterus lumpus L.) after a single oral administration. Aquaculture 2019, 512, 734279. [CrossRef]

- Feng, J.B.; Huang, D.R.; Zhong, M.; Liu, P.; Dong, J.D. Pharmacokinetics of florfenicol and behaviour of its metabolite florfenicol amine in orange-spotted grouper (Epinephelus coioides) after oral administration. J. Fish Dis. 2016, 39(7), 833-843. [CrossRef]

- Samuelsen, O.B.; Bergh, Ø.; Ervik, A. Pharmacokinetics of florfenicol in cod Gadus morhua and in vitro antibacterial activity against Vibrio anguillarum. Dis. Aquat. Org. 2003, 56(2), 127-133.

- Yang, F.; Yang, F.; Wang, G.; Kong, T.; Liu, B. Pharmacokinetics of florfenicol and its metabolite florfenicol amine in crucian carp (Carassius auratus) at three temperatures after single oral administration. Aquaculture 2019, 503, 446-451. [CrossRef]

- Lim, J.H.; Kim, M.S.; Hwang, Y.H.; Song, I.B.; Park, B.K.; Yun, H.I. Pharmacokinetics of florfenicol following intramuscular and intravenous administration in olive flounder (Paralichthys olivaceus). J. Vet. Pharmacol. Ther. 2011, 34(2), 206-208. [CrossRef]

- Pourmolaie, B.; Eshraghi, H.R.; Haghighi, M.; Mortazavi, S.A.; Rohani, M.S. Pharmacokinetics of florfenicol administrated to rainbow trout (Oncorhynchus mykiss) by oral gavages and medicated feed routes. Bull. Env. Pharmacol. Life Sci. 2015, 4(4), 14-17.

- Mallik, S.K.; Shahi, N.; Pathak, R.; Kala, K.; Patil, P.K.; Singh, B.; Ravindran, R.; Krishna, N.; Pandey, P.K. Pharmacokinetics and biosafety evaluation of a veterinary drug florfenicol in rainbow trout, Oncorhynchus mykiss (Walbaum 1792) as a model cultivable fish species in temperate water. Front. Pharmacol. 2023, 14, 1033170. [CrossRef]

- Feng, J.B.; Jia, X.P. Single dose pharmacokinetic study of flofenicol in tilapia (Oreochromis niloticus× O. aureus) held in freshwater at 22 C. Aquaculture 2009, 289(1-2), 129-133. [CrossRef]

- Rairat, T.; Hsieh, C.Y.; Thongpiam, W.; Sung, C.H.; Chou, C.C. Temperature-dependent pharmacokinetics of florfenicol in Nile tilapia (Oreochromis niloticus) following single oral and intravenous administration. Aquaculture 2019, 503, 483-488. [CrossRef]

- Fang, W.; Li, G.; Zhou, S.; Li, X.; Hu, L.; Zhou, J. Pharmacokinetics and tissue distribution of thiamphenicol and florfenicol in Pacific white shrimp Litopenaeus vannamei in freshwater following oral administration. J. Aquat. Anim. Health 2013, 25(2), 83-89. [CrossRef]

- Tipmongkolsilp, N.; Limpanon, Y.; Patamalai, B.; Lusanandana, P.; Wongtavatchai, J. Oral medication with florfenicol for black tiger shrimps Penaeus monodon. Thai J. Vet. Med. 2006, 36(2), 39-47. [CrossRef]

- Feng, Y.; Zhai, Q.; Wang, J.; Li, J.; Li, J. Comparison of florfenicol pharmacokinetics in Exopalaemon carinicauda at different temperatures and administration routes. J. Vet. Pharmacol. Ther. 2019, 42(2), 230-238. [CrossRef]

- Toutain, P.L.; Ferran, A.; Bousquet-Mélou, A. Species differences in pharmacokinetics and pharmacodynamics. Comparative and veterinary pharmacology 2010, 19-48. [CrossRef]

- Manan, H.; Zhong, J.M.H.; Othman, F.; Ikhwanuddin, M.H.D. Histopathology of the hepatopancreas of pacific white shrimp, Penaeus vannamei from none early mortality syndrome (EMS) shrimp ponds. J. Fish. Aquat. Sci. 2015, 10(6), 562-568. [CrossRef]

- Bray, W. A.; Williams, R. R.; Lightner, D. V.; Lawrence, A. L. Growth, survival and histological responses of the marine shrimp, Litopenaeus vannamei, to three dosage levels of oxytetracycline. Aquaculture 2006, 258(1-4), 97-108. [CrossRef]

- Romano, N.; Koh, C.B.; Ng, W.K. Dietary microencapsulated organic acids blend enhances growth, phosphorus utilization, immune response, hepatopancreatic integrity and resistance against Vibrio harveyi in white shrimp, Litopenaeus vannamei. Aquaculture 2015, 435, 228-236. [CrossRef]

- Maftuch, K.A.; Eslfitri, D.; Sanoesi, E.; Prihanto, A.A. Enrofloxacin stimulates cell death in several tissues of vannamei shrimp (Litopenaeus vannamei). Comp. Clin. Path. 2017, 26, 249-254. [CrossRef]

- Avunje, S.; Patil, P.K.; Ezaz, W.; Praveena, E.; Ray, A.; Viswanathan, B.; Alavandi, S.V.; Puthiyedathu, S.K.; Vijayan, K.K. Effect of oxytetracycline on the biosafety, gut microbial diversity, immune gene expression and withdrawal period in Pacific whiteleg shrimp, Penaeus vannamei. Aquaculture 2021, 543, 736957. [CrossRef]

- Balouiri, M.; Sadiki, M.; Ibnsouda, S. K. Methods for in vitro evaluating antimicrobial activity: A review. J. Pharm. Anal. 2016, 6(2), 71-79. [CrossRef]

- Jiang, H.; Yu, T.; Yang, Y.; Yu, S.; Wu, J.; Lin, R.; Li, Y.; Fang, J.; Zhu, C. Co-occurrence of antibiotic and heavy metal resistance and sequence type diversity of Vibrio parahaemolyticus isolated from Penaeus vannamei at freshwater farms, seawater farms, and markets in Zhejiang province, China. Front. Microbiol. 2020, 11, 1294. [CrossRef]

- Clinical and Laboratory Standards Institute (CLSI). Performance Standards for Antimicrobial Susceptibility Testing, 27th Edn. Wayne, PA: Clinical and Laboratory Standards Institute. 2017, P36.

- Ali, N.G.; Aboyadak, I.M.; El-Sayed, H.S. Chemotherapeutic control of Gram-positive infection in white sea bream (Diplodus sargus, Linnaeus 1758) broodstock. Vet. World. 2019, 12(2), 316. https://10.14202/vetworld.2019.316-324.

- Huynh, T.K.D.; Scippo, M.L.; Devreese, M.; Croubels, S.; Nguyen, Q.T.; Douny, C.; Dang, T.H.O.; Le, Q.V.; Tran, M.P. Pharmacokinetics and Withdrawal Times of Cefotaxime in White Leg Shrimp (Litopenaeus vannamei) after Oral Administration. Fishes 2024, 9(6), 232. [CrossRef]

- Nima, N.; Duangsuwan, P.; Pongtippatee, P.; Kanjanasopa, D.; Withyachumnarnkul, B. Types of cells in the hepatopancreas of the Pacific whiteleg shrimp Litopenaeus vannamei being infected by Enterocytozoon hepatopenaei. Songklanakarin J. Sci. Technol. 2022, 44(1), 97-102.

- United States Department of Agriculture Food Safety and Inspection Service (USDA), Office of Public Health Science Determination and Confirmation of Florfenicol, 2010. CLG-FLOR1.04, pp. 1–27.

- European Commission (EC). Commission Decision 2002/657/EC of 12 August 2002 implementing Council Directive 96/23/EC concerning the performance of analytical methods and the interpretation of results. O. J. E. C., 2002; 221, pp. 8–36.

- European Medicine Agency (EMA). Guideline on determination of withdrawal periods for edible tissues. 2022. Available online: https://www.ema.europa.eu/en/documents/scientific-guideline/adopted-guideline-determination-withdrawal-periods-edible-tissues-revision-2_en.pdf (accessed on 10 June 2024).

- Hekman, P. Withdrawal-Time Calculation Program WT1. 4; BRD Agency for the Registration of Veterinary Medicinal Products: Wageningen, The Netherlands, 2004; pp. 1–8.

- Mohney, L.L.; Bell, T.A.; Lightner, D.V. Shrimp Antimicrobial Testing. I. In Vitro Susceptibility of Thirteen Gram-Negative Bacteria to Twelve Antimicrobials. J. Aquat. Anim. Health 1992, 4(4), 257-261. [CrossRef]

- Roque, A.; Molina-Aja, A.; Bolán-Mejıa, C.; Gomez-Gil, B. In vitro susceptibility to 15 antibiotics of vibrios isolated from penaeid shrimps in Northwestern Mexico. Int. J. Antimicrob. Agents 2001, 17(5), 383-387. [CrossRef]

- Sotomayor, M.A.; Reyes, J.K.; Restrepo, L.; Domínguez-Borbor, C.; Maldonado, M.; Bayot, B. Efficacy assessment of commercially available natural products and antibiotics, commonly used for mitigation of pathogenic Vibrio outbreaks in Ecuadorian Penaeus (Litopenaeus) vannamei hatcheries. PloS one 2019, 14(1), e0210478. [CrossRef]

- Vaseeharan, B.; Ramasamy, P.; Murugan, T.; Chen, J.C. In vitro susceptibility of antibiotics against Vibrio spp. and Aeromonas spp. isolated from Penaeus monodon hatcheries and ponds. Int. J. Antimicrob. Agents 2005, 26(4), 285-291. [CrossRef]

- Rebouças, R.H.; de Sousa, O.V.; Lima, A.S.; Vasconcelos, F.R.; de Carvalho, P.B.; dos Fernandes Vieira, R.H.S. Antimicrobial resistance profile of Vibrio species isolated from marine shrimp farming environments (Litopenaeus vannamei) at Ceará, Brazil. Environ. Res. 2011, 111(1), 21-24. [CrossRef]

- Al-Othrubi, S.M.Y.; Kqueen, C.Y.; Mirhosseini, H.; Hadi, Y.A.; Radu, S. Antibiotic resistance of Vibrio parahaemolyticus isolated from cockles and shrimp sea food marketed in Selangor, Malaysia. Clin. Microbiol. 2014, 3(3), 148. [CrossRef]

- Melo, L.M.R.D.; Almeida, D.; Hofer, E.; Reis, C.M.F.D.; Theophilo, G.N.D.; Santos, A.F.D.M.; Vieira, R.H.S.D.F. Antibiotic resistance of Vibrio parahaemolyticus isolated from pond-reared Litopenaeus vannamei marketed in Natal, Brazil. Braz. J. Microbiol. 2011, 42, 1463-1469. [CrossRef]

- Yano, Y.; Hamano, K.; Satomi, M.; Tsutsui, I.; Aue-umneoy, D. Diversity and characterization of oxytetracycline-resistant bacteria associated with non-native species, white-leg shrimp (Litopenaeus vannamei), and native species, black tiger shrimp (Penaeus monodon), intensively cultured in Thailand. J. Appl. Microbiol. 2011, 110(3), 713-722. [CrossRef]

- Zanetti, S.; Spanu, T.; Deriu, A.; Romano, L.; Sechi, L.A.; Fadda, G. In vitro susceptibility of Vibrio spp. isolated from the environment. Int. J. Antimicrob. Agents 2001, 17(5), 407-409. [CrossRef]

- Tran, T.H.T.; Yanagawa, H.; Nguyen, K.T.; Hara-Kudo, Y.; Taniguchi, T.; Hayashidani, H. Prevalence of Vibrio parahaemolyticus in seafood and water environment in the Mekong Delta, Vietnam. J. Vet. Med. Sci. 2018, 80(11), 1737-1742. [CrossRef]

- Rocha, R.d.S.; de Sousa, O.V.; dos Fernandes Vieira, R.H.S. Multidrug-resistant Vibrio associated with an estuary affected by shrimp farming in Northeastern Brazil. Mar. Pollut. Bull. 2016, 105(1), 337-340. [CrossRef]

- Saifedden, G.; Farinazleen, G.; Nor-Khaizura, A.; Kayali, A.Y.; Nakaguchi, Y.; Nishibuchi, M.; Son, R. Antibiotic Susceptibility profile of Vibrio parahaemolyticus isolated from shrimp in Selangor, Malaysia. Int. Food Res. J. 2016, 23(6), 2732-2736.

- Morales-Covarrubias, M.S.; Tlahuel-Vargas, L.; Martínez-Rodríguez, I.E.; Lozano-Olvera, R.; Palacios-Arriaga, J.M. Necrotising hepatobacterium (NHPB) infection in Penaeus vannamei with florfenicol and oxytetracycline: a comparative experimental study. Rev. Cient. 2012, 22(1), 72-80.

- Tu, H.T.; Silvestre, F.; Phuong, N.T.; Kestemont, P. Effects of pesticides and antibiotics on penaeid shrimp with special emphases on behavioral and biomarker responses. Environ. Toxicol. Chem. 2010, 29(4), 929-938. [CrossRef]

- Verri, T.; Mandal, A.; Zilli, L.; Bossa, D.; Mandal, P.K.; Ingrosso, L.; Zonno, V.; Vilella, S.; Ahearn, G.A.; Storelli, C. D-glucose transport in decapod crustacean hepatopancreas. Comp. Biochem. Physiol. A: Mol. Integr. Physiol. 2001, 130(3), 585-606. [CrossRef]

- Faroongsarng, D.; Chandumpai, A.; Chiayvareesajja, S.; Theapparat, Y. Bioavailability and absorption analysis of oxytetracycline orally administered to the standardized moulting farmed Pacific white shrimps (Penaeus vannamei). Aquaculture 2007, 269(1-4), 89-97. [CrossRef]

- Ma, R.; Wang, Y.; Zou, X.; Fu, G.; Li, C.; Fan, P.; Fang, W. Pharmacokinetics of oxytetracycline in Pacific white shrimp, Penaeus vannamei, after oral administration of a single-dose and multiple-doses. Aquaculture 2019, 512, 734348. [CrossRef]

- Chiayvareesajja, S.; Chandumpai, A.; Theapparat, Y.; Faroongsarng, D. The complete analysis of oxytetracycline pharmacokinetics in farmed Pacific white shrimp (Litopenaeus vannamei). J. Vet. Pharmacol. Ther. 2006, 29(5), 409-414. [CrossRef]

- Ma, R.; Wang, Y.; Zou, X.; Hu, K.; Sun, B.; Fang, W.; Fu, G.; Yang, X. Pharmacokinetics of sulfamethoxazole and trimethoprim in Pacific white shrimp, Litopenaeus vannamei, after oral administration of single-dose and multiple-dose. Environ. Toxicol. Pharmacol. 2017, 52, 90-98. [CrossRef]

- Fang, X.; Zhou, J.; Liu, X. Pharmacokinetics and tissue distribution of enrofloxacin after single intramuscular injection in Pacific white shrimp. J. Vet. Pharmacol. Ther. 2018, 41(1), 148-154. [CrossRef]

- Ma, R.; Huang, L.; Wei, W.; Wang, Y.; Zou, X.; Zhou, J.; Li, X.; Fang, W. Pharmacokinetics of enrofloxacin and its metabolite ciprofloxacin in Pacific white shrimp Litopenaeus vannamei after multiple-dose oral administration. Fish. Sci. 2018, 84, 869-876. [CrossRef]

- Dowling, P.M. Chloramphenicol, thiamphenicol, and florfenicol. Antimicrobial therapy in veterinary medicine, 2013; pp. 269-277.

- Reed, M.D. Optimal antibiotic dosing. The pharmacokinetic-pharmacodynamic interface. Postgrad. Med. 2000, 108(7), 17-24. [CrossRef]

- AliAbadi, F.S.; Lees, P. Antibiotic treatment for animals: effect on bacterial population and dosage regimen optimisation. Int. J. Antimicrob. Agents. 2000, 14(4), 307-313. [CrossRef]

- European Commission (EC). Commission Regulation (EU) No 37/2010 of 22 December 2009 on pharmacologically active substances and their classification regarding maximum residue limits in foodstuffs of animal origin.. O. J. E. C. L15, 2010, pp. 1–72. Available online: https://eur-lex.europa.eu/legal-content/EN/TXT/PDF/?uri=CELEX:32010R0037&qid=1744640112365 (accessed on 20 May 2024).

- Korean Ministry of Food and Drug Safety, MRLs Vet. Drugs, Repub. Korea. 2019. Available online at: https://apps.fas.usda.gov/newgainapi/api/Report/DownloadReportByFileName?fileName=Korea%27s+Veterinary+Drug+MRL+Situation_Seoul_Korea+-+Republic+of_11-16-2011.pdf (accessed on 20 May 2024).

- Rairat, T.; Hsieh, M.K.; Ho, W.C.; Lu, Y.P.; Fu, Z.Y.; Chuchird, N.; Chou, C.C. Effects of temperature on the pharmacokinetics, optimal dosage, tissue residue, and withdrawal time of florfenicol in asian seabass (Lates calcarifer). Food Addit. Contam.: Part A 2023, 40(2), 235-246. [CrossRef]

- Lin, H.C.; Chen, W.Y. Bayesian population physiologically-based pharmacokinetic model for robustness evaluation of withdrawal time in tilapia aquaculture administrated to florfenicol. Ecotoxicol. Environ. Saf. 2021, 210, 111867. [CrossRef]

- Wang, W.; Lin, H.; Xue, C.; Khalid, J. Elimination of chloramphenicol, sulphamethoxazole and oxytetracycline in shrimp, Penaeus chinensis following medicated-feed treatment. Environ. Int. 2004, 30(3), 367-373. [CrossRef]

- Caceci, T.; Neck, K.F.; Lewis, D.D.H.; Sis, R. F. Ultrastructure of the hepatopancreas of the pacific white shrimp, Penaeus vannamei (Crustacea: Decapoda). J. Mar. Biol. Ass. U. K. 1988, 68(2), 323-337. [CrossRef]

- Pathak, M.S.; Reddy, A.K.; Kulkarni, M.V.; Harikrishna, V.; Srivastava, P.P.; Chadha, N.K.; Lakra, W.S. Histological alterations in the hepatopancreas and growth performance of Pacific white shrimp (Litopenaeus vannamei, Boone 1931) reared in potassium fortified inland saline ground water. Int. J. Curr. Microbiol. Appl. Sci. 2018, 7(4), 3531-3542. [CrossRef]

- Hu, K.J.; Leung, P.C. Food digestion by cathepsin L and digestion-related rapid cell differentiation in shrimp hepatopancreas. Comp. Biochem. Physiol. B: Biochem. Mol. Biol. 2007, 146(1), 69-80. [CrossRef]

- Nunes, E.T.; Braga, A.A.; Camargo-Mathias, M.I. Histochemical study of the hepatopancreas in adult females of the pink-shrimp Farfantepenaeus brasiliensis Latreille, 1817. Acta histochem. 2014, 116(1), 243-251. [CrossRef]

Figure 1.

The repartition (%) of FF MIC (µg/mL) for 42 strains of V. parahaemolyticus collected in 7 provinces of the Mekong Delta, Vietnam.

Figure 1.

The repartition (%) of FF MIC (µg/mL) for 42 strains of V. parahaemolyticus collected in 7 provinces of the Mekong Delta, Vietnam.

Figure 2.

FF concentrations (mean ± SD, n = 6) in plasma, hepatopancreas and muscle of white leg shrimp after a single oral administration of 10 mg/kg bw.

Figure 2.

FF concentrations (mean ± SD, n = 6) in plasma, hepatopancreas and muscle of white leg shrimp after a single oral administration of 10 mg/kg bw.

Figure 3.

Plot of florfenicol residual levels in white leg shrimp muscle recorded at 1h, 24h and 72h (corresponding to 1.1, 26.5 and 79.5 degree-days) after stopping medication as a function of degree-days. The withdrawal time was calculated as the time when the upper limit of the one-sided 95% confidence interval was below the MRL (100 µg/kg) when shrimp were fed with FF twice a day for 3 consecutive days at a dose of 10 mg FF/kg bw, at ambient temperature 26.5 °C.

Figure 3.

Plot of florfenicol residual levels in white leg shrimp muscle recorded at 1h, 24h and 72h (corresponding to 1.1, 26.5 and 79.5 degree-days) after stopping medication as a function of degree-days. The withdrawal time was calculated as the time when the upper limit of the one-sided 95% confidence interval was below the MRL (100 µg/kg) when shrimp were fed with FF twice a day for 3 consecutive days at a dose of 10 mg FF/kg bw, at ambient temperature 26.5 °C.

Figure 4.

Representative histological section of shrimp hepatopancreas before (A) and after feeding with FF-medicated feed twice-a-day treatment on day 3 of medication (B) and 7 days after stopping medication (C) (100×). B—blasenzellen cells, F—fibrillenzellen cells.

Figure 4.

Representative histological section of shrimp hepatopancreas before (A) and after feeding with FF-medicated feed twice-a-day treatment on day 3 of medication (B) and 7 days after stopping medication (C) (100×). B—blasenzellen cells, F—fibrillenzellen cells.

Figure 5.

Number of B cells of shrimp hepatopancreas before FF medication, on day 3 of medication and on day 7 after stopping medication in once a day (dark column) and twice a day (light column) treatments with 10 mg FF/kg bw. Value with similar capitalized letter showed no significant different between doses (p > 0.05). Value with similar small letter showed no significant different between sampling time (p > 0.05).

Figure 5.

Number of B cells of shrimp hepatopancreas before FF medication, on day 3 of medication and on day 7 after stopping medication in once a day (dark column) and twice a day (light column) treatments with 10 mg FF/kg bw. Value with similar capitalized letter showed no significant different between doses (p > 0.05). Value with similar small letter showed no significant different between sampling time (p > 0.05).

Table 1.

The MIC (μg/mL) and inhibition zone diameters (mm) of FF for V. parahaemolyticus strains.

Table 1.

The MIC (μg/mL) and inhibition zone diameters (mm) of FF for V. parahaemolyticus strains.

| Isolate number |

Inhibition zone diameter |

MIC |

Isolate number |

Inhibition zone diameter |

MIC |

| 1 |

36 |

8 |

22 |

34 |

8 |

| 2 |

22 |

1 |

23 |

24 |

4 |

| 3 |

21 |

1 |

24 |

26 |

4 |

| 4 |

24 |

1 |

25 |

22 |

1 |

| 5 |

28 |

2 |

26 |

21 |

8 |

| 6 |

30 |

2 |

27 |

18 |

256 |

| 7 |

31 |

8 |

28 |

24 |

8 |

| 8 |

6 |

>256 |

29 |

23 |

16 |

| 9 |

22 |

4 |

30 |

22 |

4 |

| 10 |

24 |

2 |

31 |

25 |

8 |

| 11 |

20 |

4 |

32 |

25 |

4 |

| 12 |

30 |

4 |

33 |

24 |

4 |

| 13 |

18 |

256 |

34 |

30 |

4 |

| 14 |

24 |

8 |

35 |

25 |

4 |

| 15 |

31 |

16 |

36 |

25 |

4 |

| 16 |

18 |

256 |

37 |

26 |

4 |

| 17 |

25 |

16 |

38 |

28 |

2 |

| 18 |

26 |

4 |

39 |

27 |

8 |

| 19 |

22 |

2 |

40 |

27 |

8 |

| 20 |

36 |

4 |

41 |

25 |

8 |

| 21 |

31 |

8 |

42 |

28 |

8 |

Table 2.

Values for the main PK parameters of FF in white leg shrimp plasma after oral administration of a single dose of 10 mg FF/kg bw.

Table 2.

Values for the main PK parameters of FF in white leg shrimp plasma after oral administration of a single dose of 10 mg FF/kg bw.

| PK parameter |

Unit |

Plasma estimate |

CV% |

| ka

|

h-1

|

0.066 |

13.88 |

| T1/2abs

|

h |

10.44 |

13.88 |

| Cmax

|

µg/L |

60.56 |

7.45 |

| Tmax

|

h |

1.77 |

10.41 |

| Cl |

L/kg/h |

9.75 |

13.85 |

| Vd

|

L/kg |

4.93 |

30.51 |

| AUC0−inf

|

µg.h/L |

1026.07 |

13.85 |

| kel

|

h-1

|

1.97 |

17.96 |

| T1/2el

|

h |

0.35 |

17.96 |

Table 3.

Values for the main PK parameters of FF in white leg shrimp hepatopancreas and muscle tissues after oral administration at a single dose of 10 mg FF/kg bw.

Table 3.

Values for the main PK parameters of FF in white leg shrimp hepatopancreas and muscle tissues after oral administration at a single dose of 10 mg FF/kg bw.

| PK parameter |

Unit |

Hepatopancreas estimate |

Muscle estimate |

| Cmax

|

µg/kg |

386.92 |

11.76 |

| Tmax

|

h |

0.19 |

0.20 |

| AUC0−inf

|

µg.h/kg |

1660 |

88.0 |

Table 4.

Residual levels of FF in white leg shrimp muscle during and after medication at a dose of 10 mg FF/kg bw fed once a day and twice a day during 3 consecutive days. Values are presented as mean ± SD, n = 3.

Table 4.

Residual levels of FF in white leg shrimp muscle during and after medication at a dose of 10 mg FF/kg bw fed once a day and twice a day during 3 consecutive days. Values are presented as mean ± SD, n = 3.

| Period |

Sampling time (days) |

FF level (once a day treatment)

(µg/kg) |

FF level (twice a day treatment) (µg/kg) |

Medication

|

1 |

3.65 ± 0.16 |

20.53 ± 4.52 |

| 3 |

9.35 ± 3.10 |

49.29 ± 10.1 |

| After stopping medication |

1 |

3.03 ± 1.61 |

2.95 ± 0.95 |

| 3 |

<LOD |

<LOD |

| 7 |

<LOD |

<LOD |

| 14 |

<LOD |

<LOD |

| 21 |

<LOD |

<LOD |

Table 5.

The number of F cells of shrimp hepatopancreas before medication, on day 3 of medication and on day 7 after stopping medication in once a day and twice a day treatments with 10 mg FF/kg bw.

Table 5.

The number of F cells of shrimp hepatopancreas before medication, on day 3 of medication and on day 7 after stopping medication in once a day and twice a day treatments with 10 mg FF/kg bw.

| |

Number of F cells |

p value |

| |

Before medication |

Day 3 of medication |

Day 7 after medication |

| Once a day |

164±7 |

150±20 |

160±27 |

0.439 |

| Twice a day |

164±7 |

153±17 |

169±21 |

| p value |

0.056 |

|

Table 6.

PK parameters in white leg shrimp on other antibiotics according to different routes of administration.

Table 6.

PK parameters in white leg shrimp on other antibiotics according to different routes of administration.

| Antibiotic |

Muscle |

Hepatopancreas |

Plasma |

References |

| |

Tmax

(h) |

Cmax

(mg/kg) |

AUC0-∞

(mg h/kg) |

T1/2el

(h) |

Tmax

(h)

|

Cmax

(mg/kg) |

AUC0-∞

(mg h/kg) |

T1/2el

(h) |

Tmax

(h)

|

Cmax

(mg/L) |

AUC0-∞

(mg.h/L) |

T1/2el

(h) |

|

| Single dose |

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

Oxytetracyline*

100 mg/kg |

6 |

0.73 |

32.63 |

23.53 |

1 |

149.5 |

1015 |

14.89 |

6 |

27.77 |

691.3 |

11.01 |

[71] |

Oxytetracyline**

10 mg/kg |

6 |

7.94 |

166.5 |

20.90 |

- |

- |

- |

- |

0 |

32.22 |

266.1 |

20.74 |

[72] |

Thiamphenicol*

10 mg/kg |

2 |

2.98 |

29.33 |

6.84 |

1 |

204.2 |

1381 |

31.29 |

2 |

7.96 |

43.96 |

10.66 |

[36] |

Sulfamethoxazole*

83.3 mg/kg |

1 |

21.5 |

203.9 |

6.53 |

0.5 |

89.54 |

381.1 |

8.22 |

1 |

36.52 |

395.3 |

13.76 |

[73] |

Trimethoprim*

16.7 mg/kg |

1 |

0.78 |

1.90 |

2.12 |

0.5 |

73.17 |

321.3 |

4.53 |

1 |

0.89 |

4.82 |

7.38 |

[73] |

Enrofloxacin ***

10 mg/kg |

0.25 |

5.81 |

90.1 |

52.3 |

0.5 |

11.23 |

274.2 |

75.8 |

0.083 |

4.87 |

75.8 |

19.8 |

[74] |

| Multiple dose |

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

Enrofloxacin*

30 mg/kg |

1 |

1.96 |

34.75 |

10.92 |

3 |

16.29 |

314.9 |

15.86 |

1 |

19.64 |

299.6 |

16.07 |

[75] |

Oxytetracyline*

100 mg/kg |

6 |

1.67 |

66.05 |

35.39 |

6 |

124.3 |

1858 |

18.89 |

6 |

68.03 |

2049 |

20.52 |

[71] |

Sulfamethoxazole*

83.3 mg/kg |

1 |

47.8 |

403.5 |

10.92 |

1 |

73.73 |

756.5 |

11.33 |

1 |

85.89 |

1493 |

11.03 |

[73] |

Trimethoprim*

16.7 mg/kg |

1 |

0.80 |

3.03 |

2.71 |

1 |

46.50 |

190.2 |

9.65 |

1 |

1.14 |

4.84 |

5.25 |

[73] |

|

Disclaimer/Publisher’s Note: The statements, opinions and data contained in all publications are solely those of the individual author(s) and contributor(s) and not of MDPI and/or the editor(s). MDPI and/or the editor(s) disclaim responsibility for any injury to people or property resulting from any ideas, methods, instructions or products referred to in the content. |

© 2025 by the authors. Licensee MDPI, Basel, Switzerland. This article is an open access article distributed under the terms and conditions of the Creative Commons Attribution (CC BY) license (http://creativecommons.org/licenses/by/4.0/).