1. Introduction

Imidacloprid is the first-generation neonicotinoid insecticide developed by Bayer Crop Science, Germany [

1]. It is mainly used for the control of aphids, leaf hoppers, thrips and other stinging mouthparts pests. The mechanism of its insecticidal action is to act on the nicotinic acetylcholine receptors in the postsynaptic membrane of the insect nervous system and its surrounding nerves, so that the insects can maintain continuous excitement, paralysis and then die [

2,

3]. The effect of imidacloprid is relatively fast, and it will have a strong control effect on pests 1 day after the drug. Compared with traditional pesticides, imidacloprid has the advantages of high efficiency, high selectivity and lasting effect on target pests, and it has been widely used all over the world soon after its launch.

However, in the application process of imidacloprid, only a small amount of the effective components is absorbed by crops (about 5%), most of which will enter the soil and eventually enter the water environment with infiltration, runoff and other methods [

4]. Due to the water solubility, stability, and persistence of imidacloprid, their residues have been detected in water bodies worldwide [

5]. Struger et al. conducted three consecutive years of sampling and detection in the surrounding surface waters of 15 agricultural active areas in southwestern Ontario, Canada, from 2012 to 2014, and the results showed that the detection rate of imidacloprid exceeded 90% in more than half of the areas. In 75% of samples collected in two regions, the concentration of imidacloprid exceeded the local legal limit level (230ng/l) [

6]. In California, Starner Keith et al. collected and tested 75 surface water samples from rivers, creeks and drains around farmland, and the results showed that imidacloprid was detected in 67 samples, with the maximum residue of 3.29μg/l and the average concentration of 0.77μg/l [

7]. Similarly, imidacloprid residues have been detected in water bodies of various basins in China, such as the Yangtze River and the Yellow River, with detection concentrations ranging between 2.08 ng/l and 121.71 ng/l and an average detection concentration of 41.89 ng/l [

8]. In conclusion, imidacloprid has been detected in lakes, rivers, groundwater and other water bodies at home and abroad to varying degrees, and some areas even exceed the standard seriously. The contamination of imidacloprid in aquatic environment may cause potential health hazards to aquatic organisms. Fish are an important part of aquatic life, so it is necessary to assess the potential harm of imidacloprid to fish.

Researchers previously believed that imidacloprid had low toxicity to nontarget organisms and lacked teratogenic, carcinogenic and mutagenic effects [

9]. Until Whitehorn et al. discovered that the use of imidacloprid could significantly inhibit the reproductive ability of bumblebee populations, bringing attention to the safety of imidacloprid on nontarget organisms [

10]. Subsequently, more and more studies have shown that imidacloprid has certain effects on non-target organisms. For example, low concentration of imidacloprid can induce intestinal histological damage and intestinal oxidative stress in zebrafish, significantly increase the levels of superoxide dismutase (SOD) and catalase (CAT), and slightly induce intestinal flora imbalance and specific bacterial changes [

11]. Topal et al. studied the neurotoxicity of imidacloprid on the brain tissue of rainbow trout. The results showed that under the treatment of 10mg/l and 20mg/l imidacloprid, the activity of acetylcholinesterase (AChE) decreased and the activity of 8-hydroxy-2-deoxyguanosine (8-OHdG)(a marker related to cellular oxidative stress) increased in the brain tissue of rainbow trout. Moreover, oxidative stress parameters of rainbow trout were changed, thus showing neurotoxicity to rainbow trout [

12]. Lonare et al. found that imidacloprid was hepatotoxic to rats and could also cause damage to the reproductive system of male rats. In addition, studies have shown that imidacloprid can also slow down the growth rate [

13], reduce activity [

14], damage DNA [

15] and other effects on non-target organisms.

Goldfish (

Carassius auratus Linnaeus), a Chinese species of Cyprinidae, was selected for this study to better reflect the impact of imidacloprid on environmental organisms. Previous research has identified the metabolites of imidacloprid in goldfish, including imidacloprid-urea, imidacloprid-olefin, 5-hydroxyimidacloprid, and 6-chloronicotinic acid [

16]. This study aims to investigate the tissue distribution of imidacloprid and its metabolites in goldfish after exposure, providing new data support for the toxicity study of imidacloprid and a better understanding of its metabolic behavior in organisms.

2. Materials and Methods

2.1. Chemicals, instruments and animals

Reagents used in the experiment included imidacloprid (purity 95.00%) from Shanghai Yuanye Biotechnology Co., Ltd, imidacloprid standard (purity 98.00%) from Shanghai Anpu Experimental Technology Co., Ltd, and imidacloprid-urea methanol standard solution (100.00 mg/l), imidacloprid-olefin methanol standard solution (100.00 mg/l), 5-hydroxyimidacloprid methanol standard solution (100.00 mg/l), and 6-chloronicotinic acid methanol standard solution (100.00 mg/l) from Tianjin Alta Technology Co., Ltd. Chromatographic grade methanol and ethyl acetate were obtained from Millipore, and purified water was provided by Watson Co., Ltd. Anhydrous magnesium sulfate (analytical grade) was sourced from China Pharmaceutical Group Co., Ltd, and diatomite was from Shanghai McLean Biochemical Technology Co., Ltd.

The instruments utilized in the experiment included an Albrecht sciex5500+ high-performance liquid phase triple quadrupole tandem mass spectrometer, a Sartorius BSA124S one ten-thousandth scale from Sedolis, Germany, and an LC-DCY-12SF water bath nitrogen blowing instrument from Shanghai Lichen Instrument Technology Co., Ltd.

The test organism for the experiment was 3-month-old goldfish purchased from Hangzhou Fengqi Flower and Bird Market. The goldfish were domesticated in the laboratory for over a week prior to the formal experiment, with tap water treated by aeration dechlorination and meeting the provisions of the fishery water quality standard (GB11607-1989) used as the test water [

17]. The goldfish were examined for the absence of imidacloprid and its metabolites in their bodies before exposure. The domestication conditions were maintained at a pH of 7.0-8.5, temperature of 20.9 ± 0.4°C, and dissolved oxygen of 6.9 ± 0.2 mg/l.

2.2. Exposure experiment

For the short-term exposure test, 60 domesticated goldfish were placed into a 20 L culture barrel with 15 L of test water containing 40 mg/l imidacloprid. After one day of exposure, the goldfish were transferred to clean water for purification, with breeding density maintained at 4 tails/L and test water renewed daily. Uneaten food and feces were removed from the tank shortly after feeding to prevent food absorption and adsorption. Five goldfish were randomly selected from the experimental group at 0 h, 0.5 d, 1 d, 1.5 d, and 3 d after transfer for dissection, with each fish as an independent sample. The goldfish were anesthetized on ice, and the liver, intestine, muscle, gill tissue, brain tissue, and gonad were dissected and stored at -80°C until analysis.

In the continuous exposure experiment, domesticated goldfish were randomly divided into a control group and two treatment groups with imidacloprid concentrations of 20 mg/l and 40 mg/l. The treatment concentrations were determined based on the LC50 value of imidacloprid on goldfish obtained in an earlier stage. The feeding conditions were consistent with the short-term exposure test. Goldfish were sampled and dissected before the start of the experiment and at 2 h, 6 h, 1 d, 3 d, 5 d, 7 d, 14 d, and 28 d of exposure, with the sampling process being identical to that of the exposure test.

2.3. Sample pretreatment

Goldfish tissue samples were placed into a 20 ml centrifuge tube and mixed with 12 ml ethyl acetate aqueous solution (v/v=2/1). The mixture was vortexed for 1 minute, and then 1 g anhydrous MgSO4 and 0.5 g diatomite were added, followed by another vortex and mixing for 1 minute. The sample was sonicated at room temperature for 10 minutes and then centrifuged at 4000 r/min at 4°C for 10 minutes. The upper layer supernatant was collected, dried using nitrogen gas, reconstituted with 1 ml of methanol, and subjected to membrane analysis.

2.4. Instrument Conditions

The HPLC column used was an Eclipse C

18 column (1.8 μm, 3.0 × 100 mm, Agilent, USA) with a column temperature of 40°C, injection volume of 2 µL, and flow rate of 5 μL/s. The mobile phase consisted of 0.1% formic acid water (aqueous phase) and methanol (organic phase) using gradient elution. The elution procedure was as follows (

Table 1).

Mass spectrometry was performed using an electrospray ion source (ESI) in positive ion mode, and select ion reaction monitoring mode (SRM) was used for scanning. The spray voltage was set at 4000 V, and the temperature was maintained at 200℃. High-purity nitrogen was used as both the sheath gas and auxiliary gas at a pressure of 60 psi, while the ion transport capillary temperature was set at 450℃. The collected fragments are summarized below(

Table 2).

2.5. Detection limit, precision and recovery

The method used in this study was evaluated for its detection limit, limit of quantification, precision, and recovery, and the results showed that it met the detection requirements with good reproducibility and high precision (

Table 3).

2.6. Data analysis

Data analysis was performed using Microsoft Excel 2019 software, and the mean value and standard deviation were calculated and analyzed by T-test.

4. Discussion

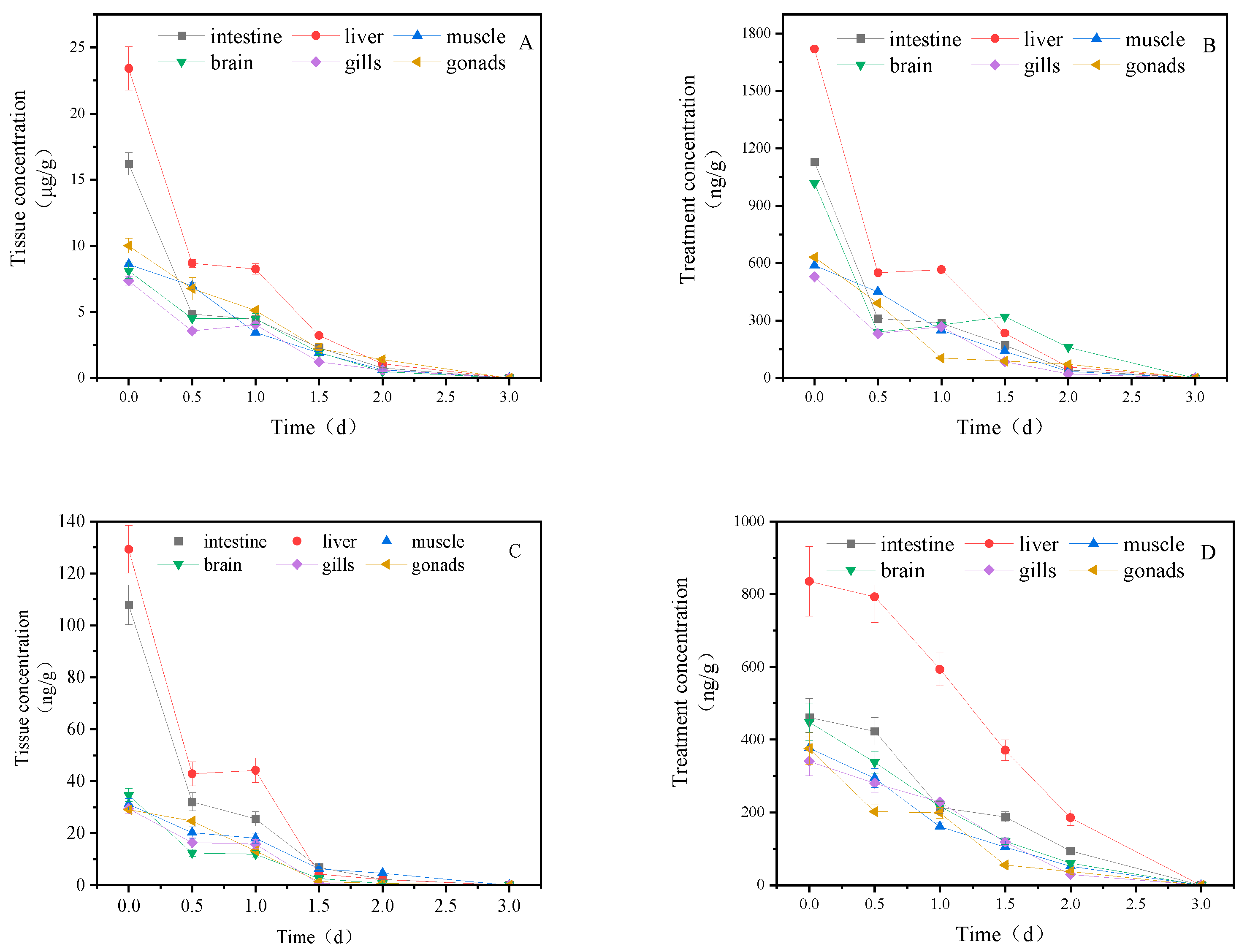

In the short-term exposure experiment, it was observed that the content of imidacloprid and its metabolites in all tissues was below the detection limit three days after transfer, which is consistent with the degradation rate of imidacloprid in rats. After oral administration of imidacloprid to rats, it was found that the initial half-life of imidacloprid was approximately 3 hours, while the final half-life ranged from 26 to 118 hours, and the residual amount of imidacloprid in tissues was less than 1% after 48 hours. Similarly, Poliserpi et al. reported that the concentration of imidacloprid in the tissues of Agelaioides badius was below the detection limit after 48 hours of oral administration of imidacloprid in the United States [

18]. These findings suggest that imidacloprid undergoes rapid degradation in organisms. The accumulation of chemicals in organisms is often dependent on their solubility, where better water solubility leads to poorer accumulation ability [

19]. Due to its better water solubility, imidacloprid and its metabolites have a faster degradation rate in goldfish. In contrast, the concentration of imidacloprid in gills increased at 1-1.5 days. The gill is the primary sensing organ of fish for pollutants in water, and due to the lack of metabolic enzymes around it, the concentration of imidacloprid in gill tissue should increase with increasing exposure time [

20]. Subsequently, water samples were collected at 1-1.5 days, and a certain amount of imidacloprid was detected in the water samples at 1.5 days (unpublished data). This could be due to imidacloprid absorbed by goldfish being excreted through the intestine and then reabsorbed by the gills, resulting in a transient rise in the concentration of imidacloprid in the gills.

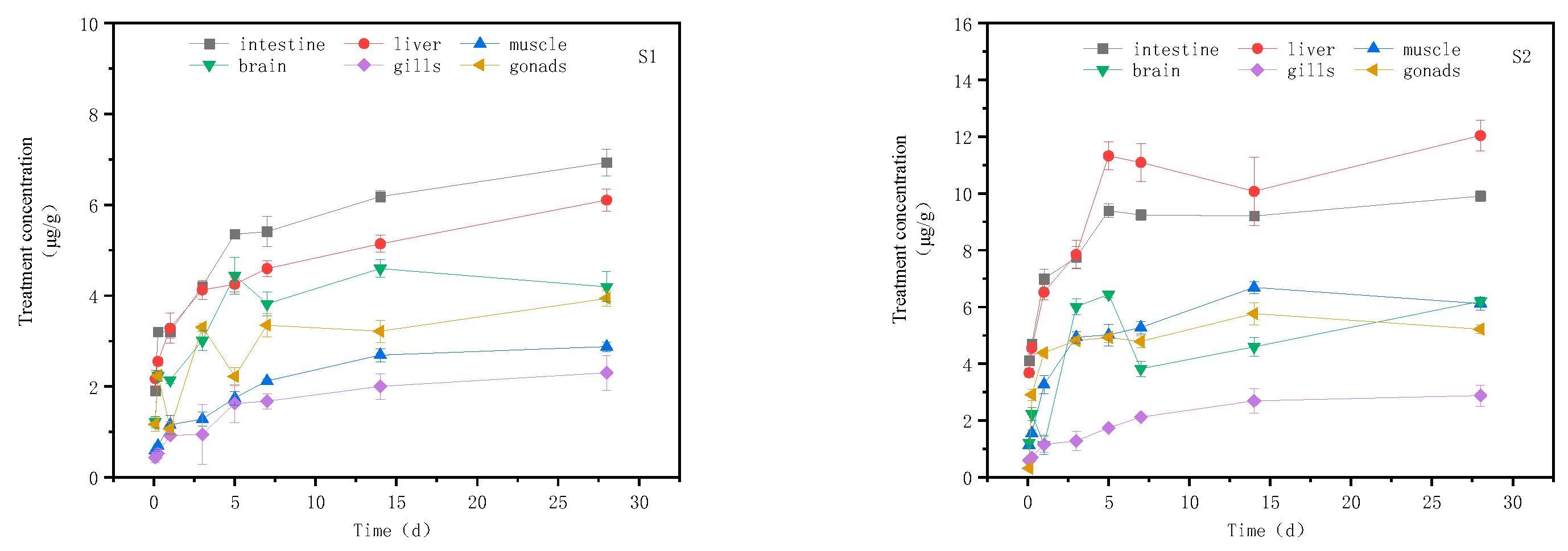

The continuous exposure test revealed that goldfish accumulated the highest concentration of imidacloprid in their intestine and liver. This result is consistent with previous studies, such as Yi Yang et al.'s research, which found that after thiamethoxam exposure, zebrafish had the highest concentration of thiamethoxam in their liver and intestine, suggesting that the hepatointestinal system is a primary site of accumulation for exogenous drugs [

21]. Similarly, Yang Bin IHM's study reported that the highest accumulation of imidacloprid in crucian carp was found in the liver [

22]. Therefore, it can be inferred that the accumulation pathway through hepatointestinal recycling may play an important role in imidacloprid absorption in fish. Furthermore, the accumulation dynamics of imidacloprid in the intestine, liver, gill tissue, and brain tissue were relatively straightforward, with their content increasing with the duration of exposure. In contrast, the accumulation in muscle and gonad was more complex. Previous research has indicated that imidacloprid accumulates in the muscle tissue of Procambarus clarkii, likely due to the high lipid content of the muscle composition and imidacloprid's lipophilicity. The presence of metabolic enzymes in muscle tissue leads to the degradation of imidacloprid into low-toxicity metabolites, which enter the bloodstream and are excreted from the body [

20]. The gonad is located on the dorsal wall of the body cavity of goldfish, near the end of the intestine. The accumulation of imidacloprid in the gonad may be affected by multiple factors, including the intestine and blood, resulting in complex accumulation dynamics.

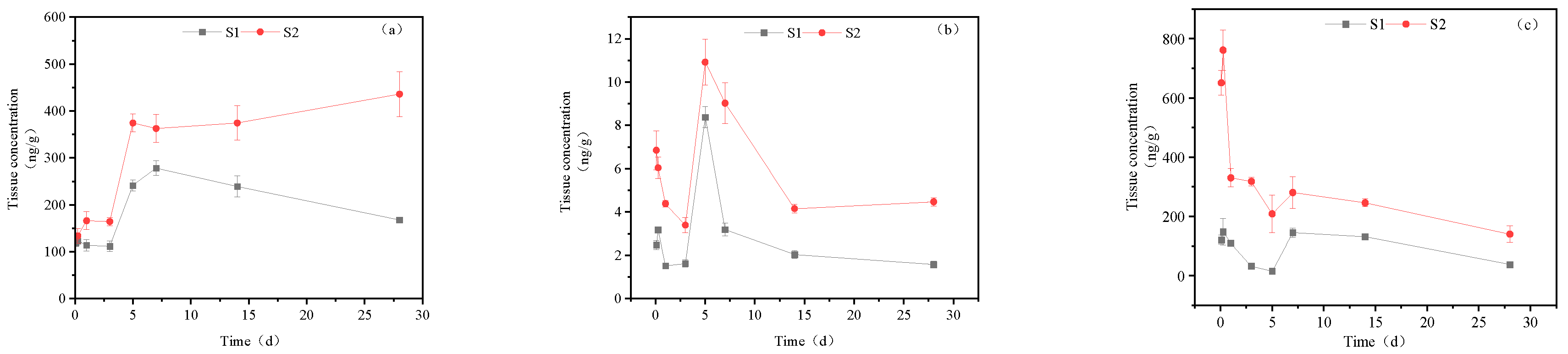

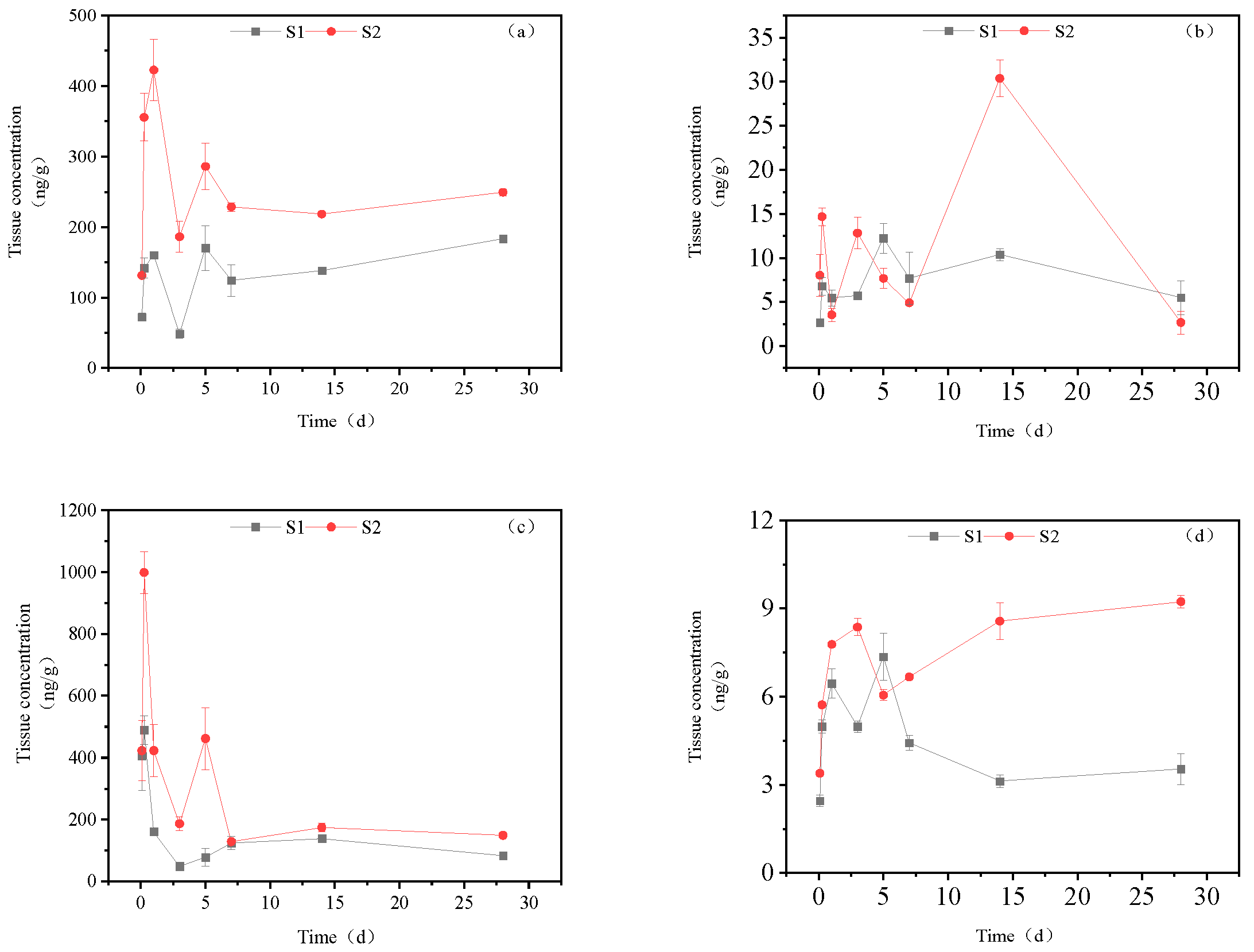

Subsequently, we analyzed the timing of the maximum accumulation of imidacloprid metabolites in each tissue and the ratio between the maximum accumulation and absorbed imidacloprid. The results are presented in

Table 4. It is evident that 5-hydroxyimidacloprid had the highest concentration in all tissues, followed by imidacloprid urea. Only a small amount of imidacloprid was detected as 6-chloronicotinic acid and imidacloprid-olefin, with the latter only present in the liver and intestine. This distribution indicated that imidacloprid urea and 5-hydroxyimidacloprid were the primary metabolites of imidacloprid in goldfish, while 6-chloronicotinic acid and imidacloprid were secondary metabolites. This differs from Suchail et al.'s research on the distribution and metabolism of imidacloprid in bees, where imidacloprid-urea and 6-chloronicotinic acid were the main metabolites, especially in the midgut and rectum. imidacloprid-olefin and 4,5-dihydroxyimidacloprid were preferentially produced in the head, chest, and abdomen, which are rich in acetylcholine receptors [

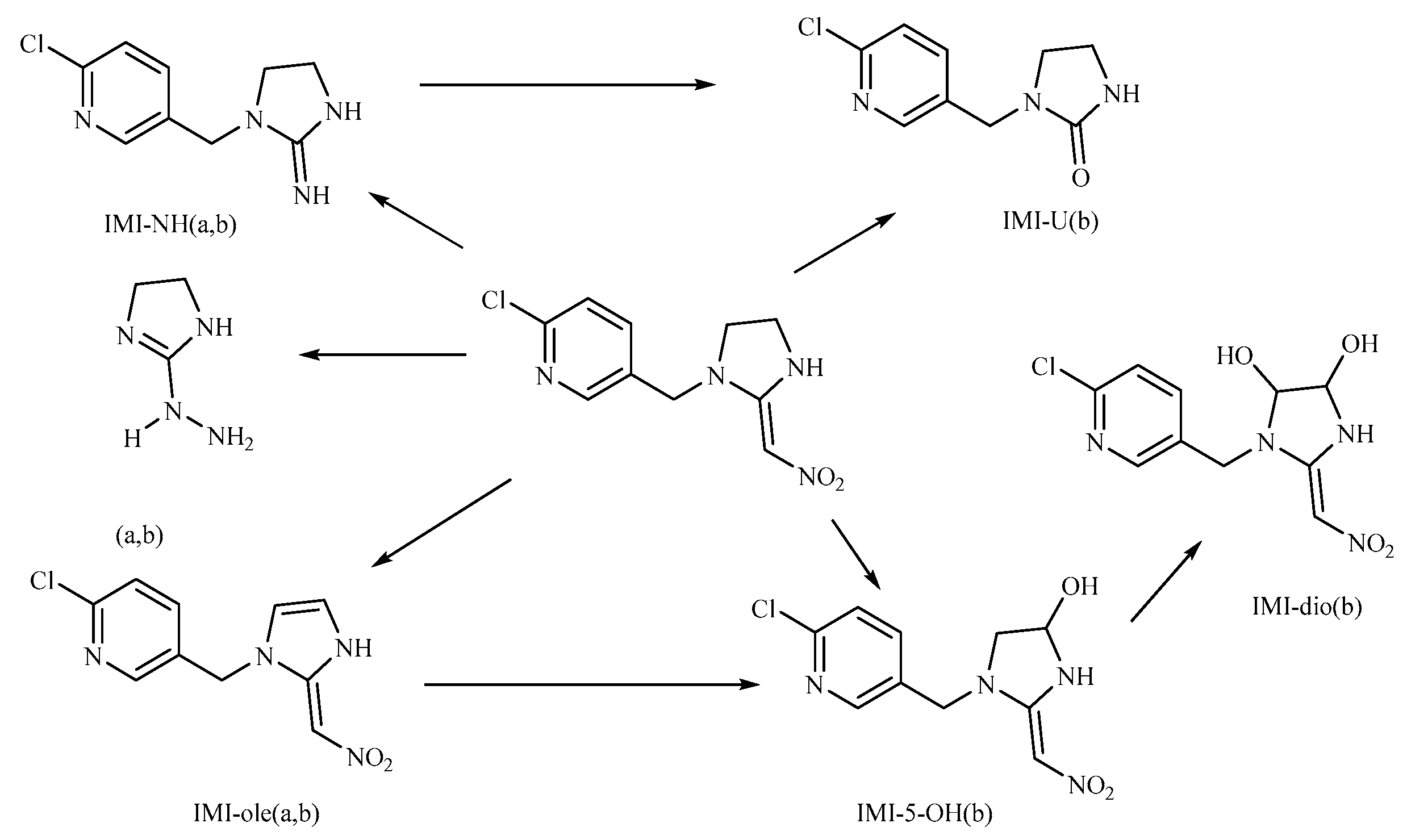

23]. The differences in this experiment's distribution may be attributed to the concentration of imidacloprid used in the treatment and the differences in metabolic pathways between vertebrates and nonvertebrates. Byren and Nishiwaki's research showed that the primary metabolites of imidacloprid after metabolism in houseflies and bees were 5-hydroxyimidacloprid, 4,5-dihydroxyimidacloprid, 6-chloronicotinic acid, imidacloprid-olefin, and imidacloprid urea. See

Figure 9 for the metabolic pathways [

24,

25].

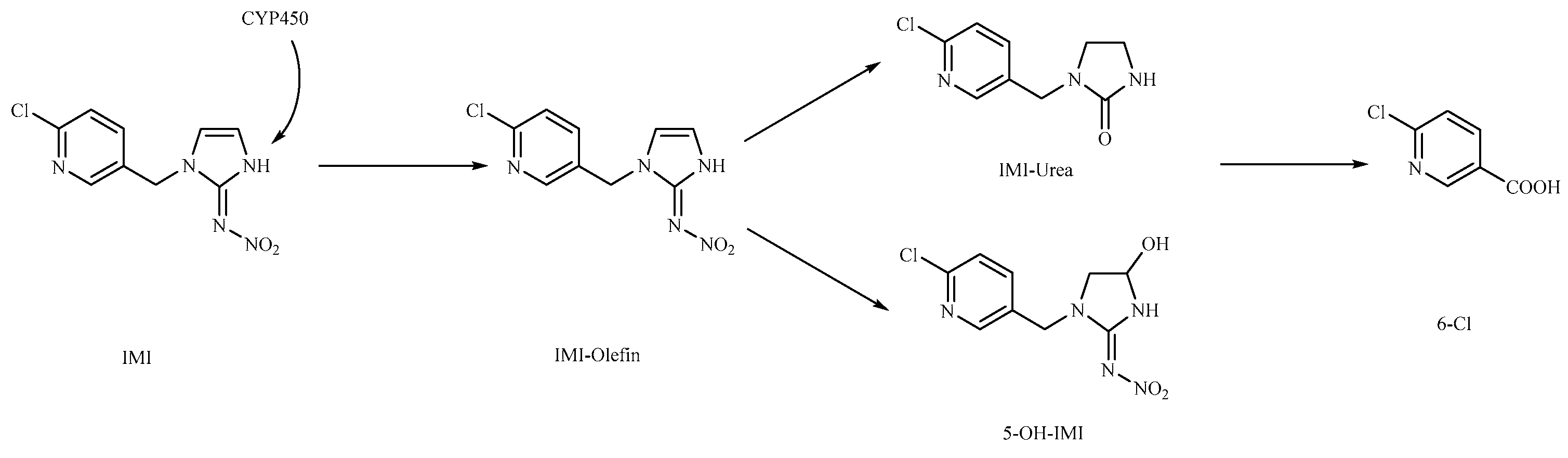

In this study, the highest ratio of the total content of metabolites detected in the liver to imidacloprid was observed at 6 h after exposure, indicating that the liver is likely the earliest metabolic site for imidacloprid in goldfish. The intestine was also found to be an important site for imidacloprid metabolism. These findings are consistent with a previous study by Yang et al., which showed that the metabolism of thiamethoxam in zebrafish occurred in both the liver and intestine and that its metabolic pathway involved N-demethylation and nitro reduction [

26]. After exogenous drugs enter the organism, phase I and phase II metabolism occur under the action of catalytic enzymes in the body. Phase I metabolism mainly involves hydroxylation, desaturation, dealkylation, and nitro reduction, among other reactions. The cytochrome CYP450 enzyme, which exists in the liver, is an important oxidative metabolic enzyme that catalyzes these reactions [

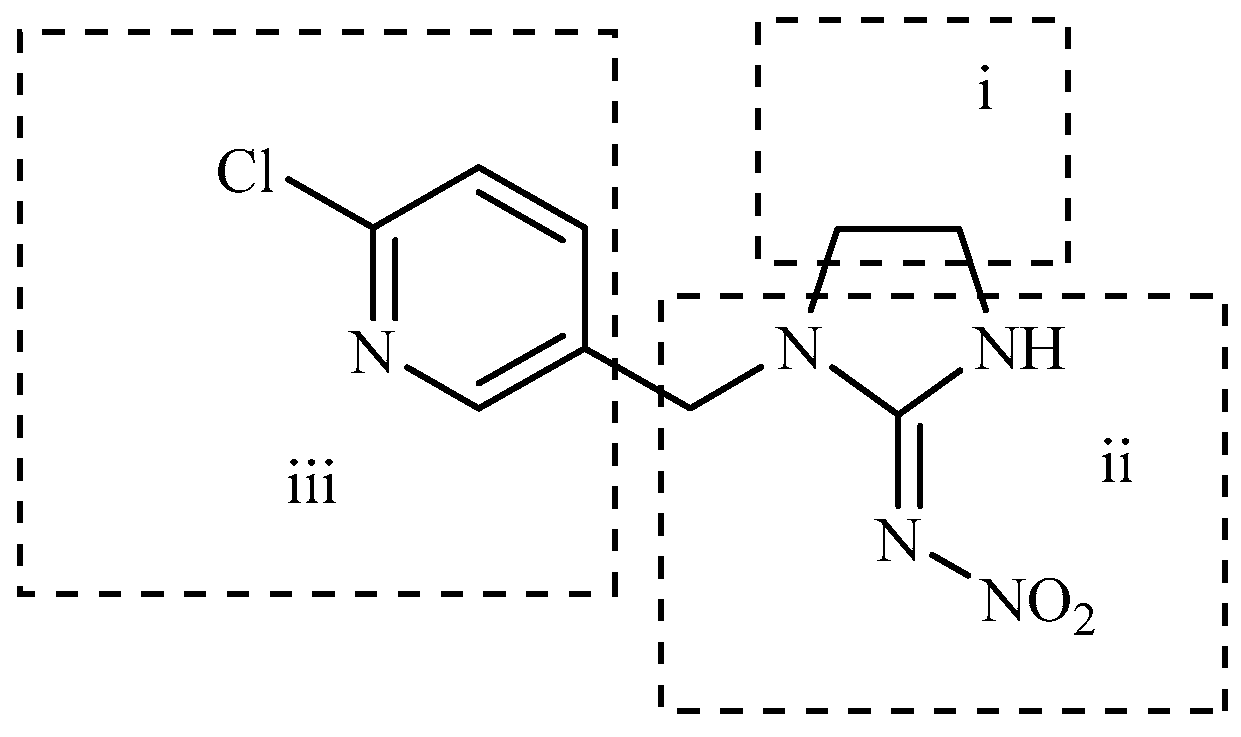

27]. The structure of imidacloprid, shown in

Figure 10, contains chemical reaction sites located on the methylene bridge chain (I structure), the pharmacophore nitroimine (II structure), and the six-membered ring (III structure), which can undergo a series of metabolic reactions under the action of catalytic enzymes in vivo. Based on these observations, we hypothesize that the possible metabolic pathway of imidacloprid in goldfish involves a dehydrogenation reaction in the I structure to generate imidacloprid-olefin, followed by hydroxylation and nitro reduction reactions to generate 5-hydroxyimidacloprid, imidacloprid urea, and 6-chloronicotinic acid, as shown in

Figure 11. These metabolites enter tissues through the circulatory system for enrichment or exclusion.

Upon detoxification and metabolism, the biological activity of imidacloprid metabolites will decrease, but in some cases, imidacloprid may produce more active metabolites. For instance, Suchail's study revealed that the two secondary metabolites of imidacloprid in bees, imidacloprid alkenyl and 5-hydroxyimidacloprid, may have a greater relationship with the toxicity of imidacloprid. The toxicity of imidacloprid alkenyl is twice that of imidacloprid and 10 times that of 5-hydroxyimidacloprid [

28]. Additionally, studies have reported that the toxicity of imidacloprid-olefin to Bemisia tabaci and Myzus persicae is approximately 10 times and 16 times higher than that of imidacloprid, respectively, indicating that imidacloprid alkenyl has higher toxicity than the parent compound [

29]. In this study, a small amount of imidacloprid-olefin was detected in the intestine and liver of goldfish, and further exploration of its subsequent effects on the intestine and liver can help clarify the toxicity mechanism of imidacloprid-olefin. Moreover, metabolites with nitroimine pharmacophores, such as hydroxylated imidacloprid and alkenylimidacloprid, are toxic to bees, while imidacloprid urea and 6-chloronicotinic acid, which are metabolites without pharmacodynamic groups, are nontoxic to bees [

30]. The biological activities of imidacloprid and its metabolites, from high to low, are olefinic imidacloprid, imidacloprid, 4-hydroxyimidacloprid, 5-hydroxyimidacloprid, and 4,5-dihydroxyimidacloprid. Thus, the biological activity of imidacloprid is produced by the interaction of parent and metabolites. In-depth studies on the differences in the metabolic pathways of imidacloprid in target and nontarget organisms, as well as its metabolic differences in different parts of the same organism, can provide a better understanding of its toxic mechanism and provide ideas and references for the standardized use of imidacloprid.

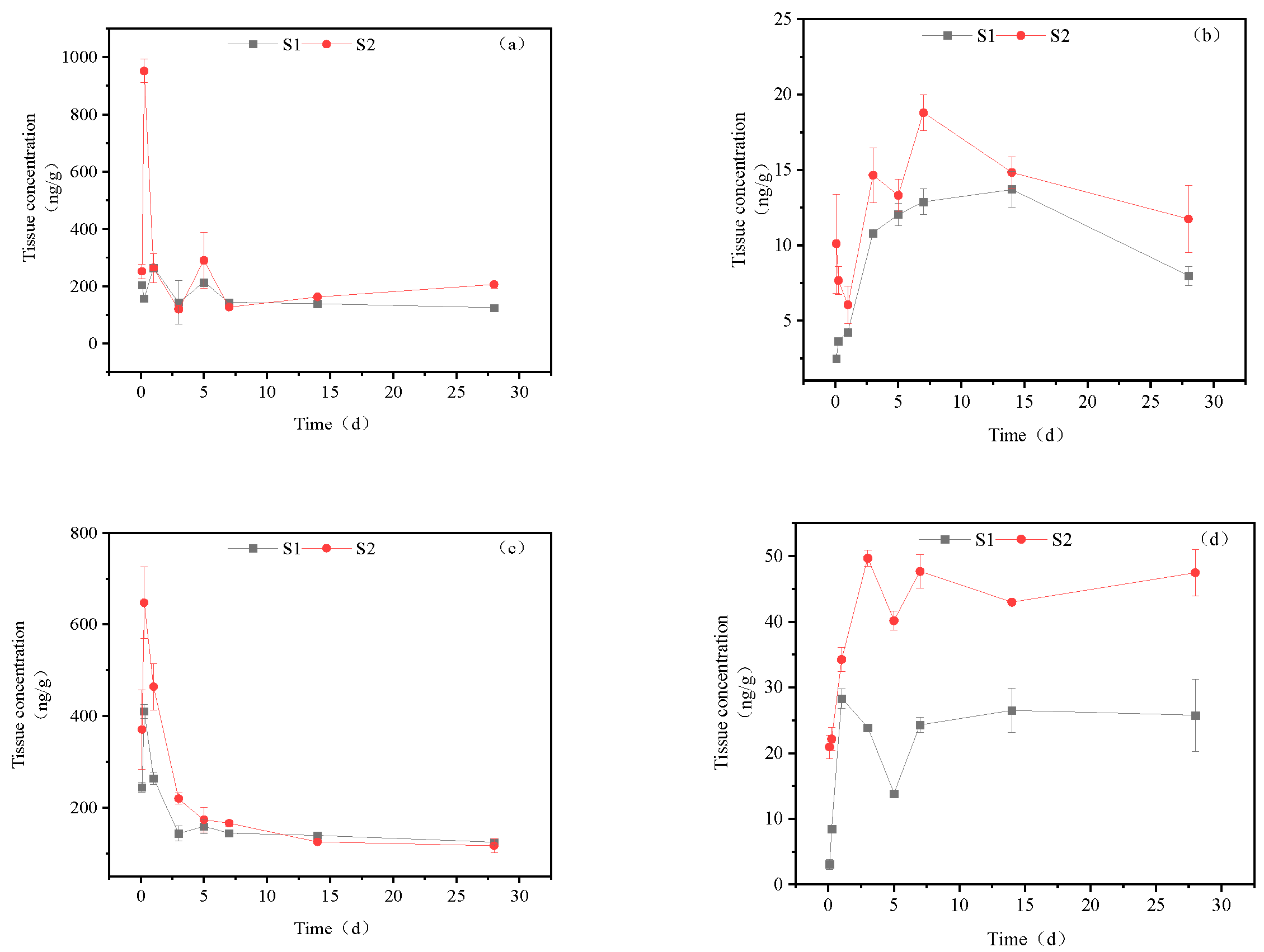

Figure 1.

Concentration changes of imidacloprid and its metabolites in goldfish under short-term exposure(treatment concentration: 40mg/l), a: imidacloprid, b: imidacloprid-urea, c: 6-chloronicotinic acid, d: 5-hydroxyimidacloprid.

Figure 1.

Concentration changes of imidacloprid and its metabolites in goldfish under short-term exposure(treatment concentration: 40mg/l), a: imidacloprid, b: imidacloprid-urea, c: 6-chloronicotinic acid, d: 5-hydroxyimidacloprid.

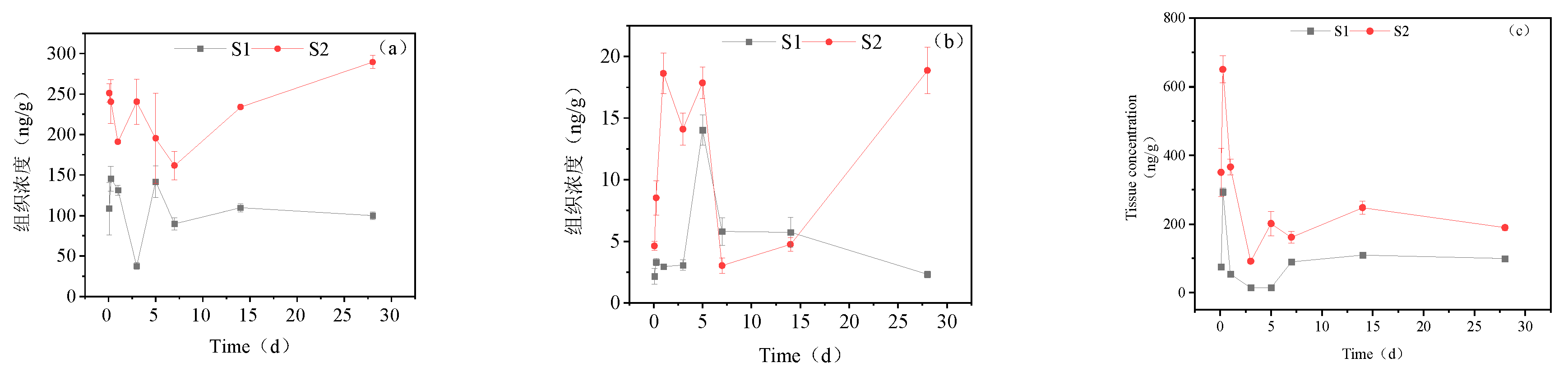

Figure 2.

Concentration changes imidacloprid in goldfish under continuous exposure(Treatment concentration: S1:20mg/l; S2:40mg/l).

Figure 2.

Concentration changes imidacloprid in goldfish under continuous exposure(Treatment concentration: S1:20mg/l; S2:40mg/l).

Figure 3.

Concentration changes in imidacloprid metabolites in gill tissues(Treatment concentration: S1:20mg/l; S2:40mg/l), a: imidacloprid urea, b: 6-chloronicotinic acid, c: 5-hydroxyimidacloprid.

Figure 3.

Concentration changes in imidacloprid metabolites in gill tissues(Treatment concentration: S1:20mg/l; S2:40mg/l), a: imidacloprid urea, b: 6-chloronicotinic acid, c: 5-hydroxyimidacloprid.

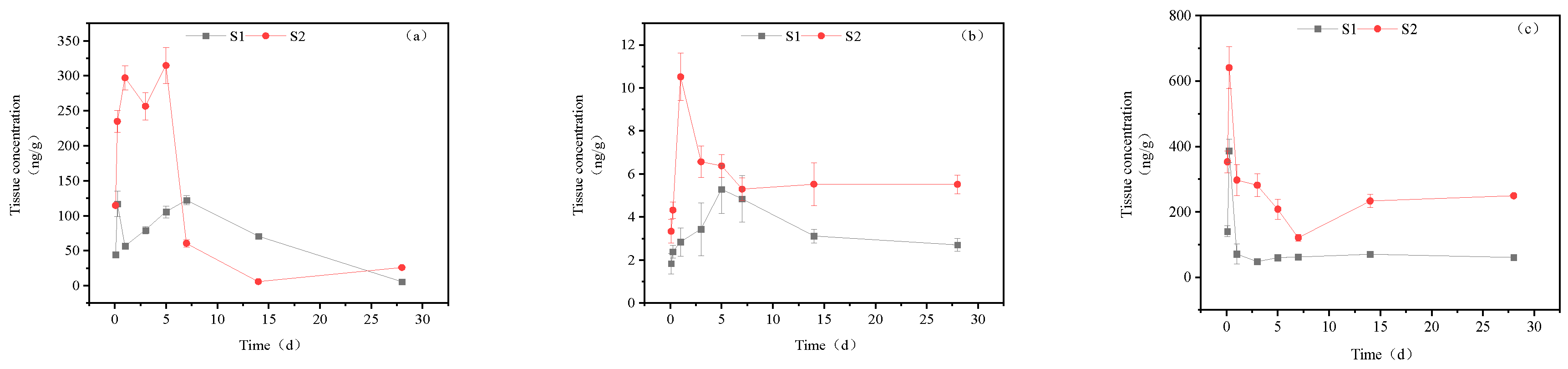

Figure 4.

Concentration changes in imidacloprid metabolites in intestine (Treatment concentration: S1:20mg/l; S2:40mg/l), a: imidacloprid urea, b: 6-chloronicotinic acid, c: 5-hydroxyimidacloprid, d: imidacloprid-olefin.

Figure 4.

Concentration changes in imidacloprid metabolites in intestine (Treatment concentration: S1:20mg/l; S2:40mg/l), a: imidacloprid urea, b: 6-chloronicotinic acid, c: 5-hydroxyimidacloprid, d: imidacloprid-olefin.

Figure 5.

Concentration changes in imidacloprid metabolites in intestine (Treatment concentration: S1:20mg/l; S2:40mg/l), a: imidacloprid urea, b: 6-chloronicotinic acid, c: 5-hydroxyimidacloprid, d: imidacloprid-olefin.

Figure 5.

Concentration changes in imidacloprid metabolites in intestine (Treatment concentration: S1:20mg/l; S2:40mg/l), a: imidacloprid urea, b: 6-chloronicotinic acid, c: 5-hydroxyimidacloprid, d: imidacloprid-olefin.

Figure 6.

Concentration changes in imidacloprid metabolites in muscle (Treatment concentration: S1:20mg/l; S2:40mg/l), a: imidacloprid urea, b: 6-chloronicotinic acid, c: 5-hydroxyimidacloprid.

Figure 6.

Concentration changes in imidacloprid metabolites in muscle (Treatment concentration: S1:20mg/l; S2:40mg/l), a: imidacloprid urea, b: 6-chloronicotinic acid, c: 5-hydroxyimidacloprid.

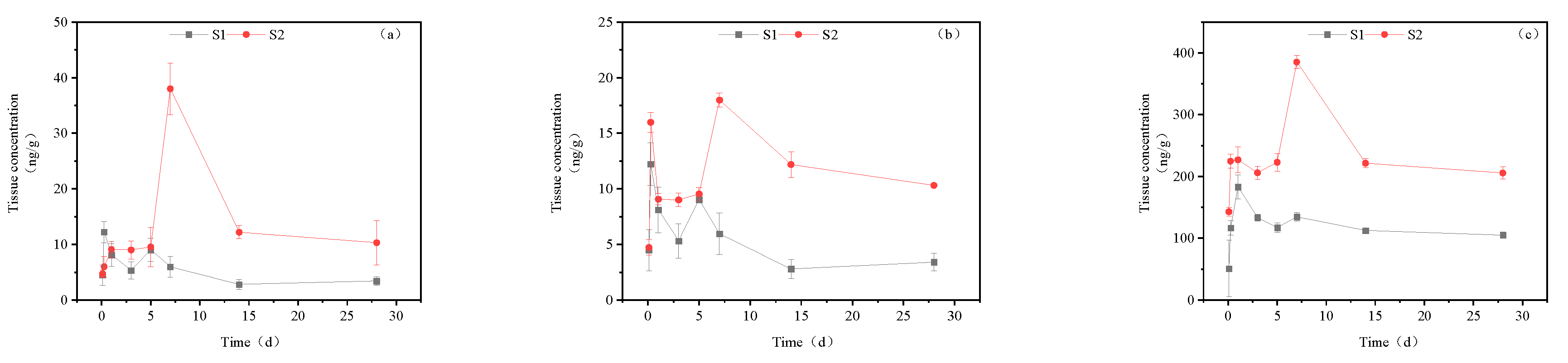

Figure 7.

Concentration changes in imidacloprid metabolites in brain tissue (Treatment concentration: S1:20mg/l; S2:40mg/l), a: imidacloprid urea, b: 6-chloronicotinic acid, c: 5-hydroxyimidacloprid.

Figure 7.

Concentration changes in imidacloprid metabolites in brain tissue (Treatment concentration: S1:20mg/l; S2:40mg/l), a: imidacloprid urea, b: 6-chloronicotinic acid, c: 5-hydroxyimidacloprid.

Figure 8.

Concentration changes in imidacloprid metabolites in gonads (Treatment concentration: S1:20mg/l; S2:40mg/l), a: imidacloprid urea, b: 6-chloronicotinic acid, c: 5-hydroxyimidacloprid.

Figure 8.

Concentration changes in imidacloprid metabolites in gonads (Treatment concentration: S1:20mg/l; S2:40mg/l), a: imidacloprid urea, b: 6-chloronicotinic acid, c: 5-hydroxyimidacloprid.

Figure 9.

Metabolic pathways of imidacloprid in housefly (a) and honeybee (b).

Figure 9.

Metabolic pathways of imidacloprid in housefly (a) and honeybee (b).

Figure 10.

Structure of imidacloprid.

Figure 10.

Structure of imidacloprid.

Figure 11.

Possible metabolic pathways of imidacloprid in goldfish.

Figure 11.

Possible metabolic pathways of imidacloprid in goldfish.

Table 1.

Gradient elution procedure.

Table 1.

Gradient elution procedure.

| Time/min |

aqueous phase % |

organic phase /% |

| 0-5 |

80 |

20 |

| 5 |

60 |

40 |

| 6 |

40 |

60 |

| 7 |

80 |

20 |

| 8 |

80 |

20 |

Table 2.

Fragment parameters were collected by mass spectrometry.

Table 2.

Fragment parameters were collected by mass spectrometry.

| Detection object |

Parent ion |

Daughter ion |

| Imidacloprid |

256.2 |

175.3 |

| Imidacloprid- urea |

212.2 |

128.1 |

| Imidacloprid- olefin |

254.2 |

171.0 |

| 5-hydroxyimidacloprid |

272.2 |

225.3 |

| 6-chloronicotinic acid |

155.9 |

112.1 |

Table 3.

Detection limit, precision and recovery of imidacloprid and its metabolites.

Table 3.

Detection limit, precision and recovery of imidacloprid and its metabolites.

| object |

LOD(limit of detection) (μg/l) |

LOQ(limit of quantitation) (μg/l) |

precision/% |

recovery/% |

RSD/% |

| Imidacloprid |

0.001 |

0.00334 |

3.41 |

96.08 |

6.523 |

| Imidacloprid- urea |

0.0099 |

0.032907 |

1.98 |

99.77 |

4.172 |

| Imidacloprid- olefin |

0.0011 |

0.003519 |

3.79 |

85.25 |

7.355 |

| 5-hydroxyimidacloprid |

0.0068 |

0.022718 |

2.84 |

87.24 |

8.825 |

| 6-chloronicotinic acid |

0.0056 |

0.018682 |

2.64 |

100.23 |

2.805 |

Table 4.

The metabolites of imidacloprid.

Table 4.

The metabolites of imidacloprid.

| |

Metabolite |

Maximum accumulation |

Time |

Ratio |

| Intestine |

Imidacloprid- urea |

432.34 |

24h |

7.47% |

| Imidacloprid- olefin |

9.37 |

28d |

0.10% |

| 6-chloronicotinic acid |

31.27 |

14d |

0.32% |

| 5-hydroxyimidacloprid |

1021.25 |

6h |

35.64% |

| liver |

Imidacloprid- urea |

952.38 |

6h |

25.81% |

| Imidacloprid- olefin |

38.28 |

28d |

0.32% |

| 6-chloronicotinic acid |

18.79 |

14d |

0.18% |

| 5-hydroxyimidacloprid |

653.13 |

6h |

23.60% |

| gill |

Imidacloprid- urea |

430.67 |

28d |

9.72% |

| 6-chloronicotinic acid |

10.97 |

5d |

0.23% |

| 5-hydroxyimidacloprid |

784.34 |

6h |

42.68% |

| Muscle |

Imidacloprid- urea |

298.39 |

28d |

3.99% |

| 6-chloronicotinic acid |

18.85 |

1d |

0.16% |

| 5-hydroxyimidacloprid |

758.45 |

6h |

19.34% |

| Brain |

Imidacloprid- urea |

319.24 |

5d |

7.30% |

| 6-chloronicotinic acid |

10.74 |

1d |

0.06% |

| 5-hydroxyimidacloprid |

654 |

6h |

21.80% |

| gonad |

Imidacloprid- urea |

38.92 |

7d |

0.41% |

| 6-chloronicotinic acid |

18.34 |

6h |

0.59% |

| 5-hydroxyimidacloprid |

389.56 |

7d |

5.58% |