Submitted:

29 August 2025

Posted:

01 September 2025

You are already at the latest version

Abstract

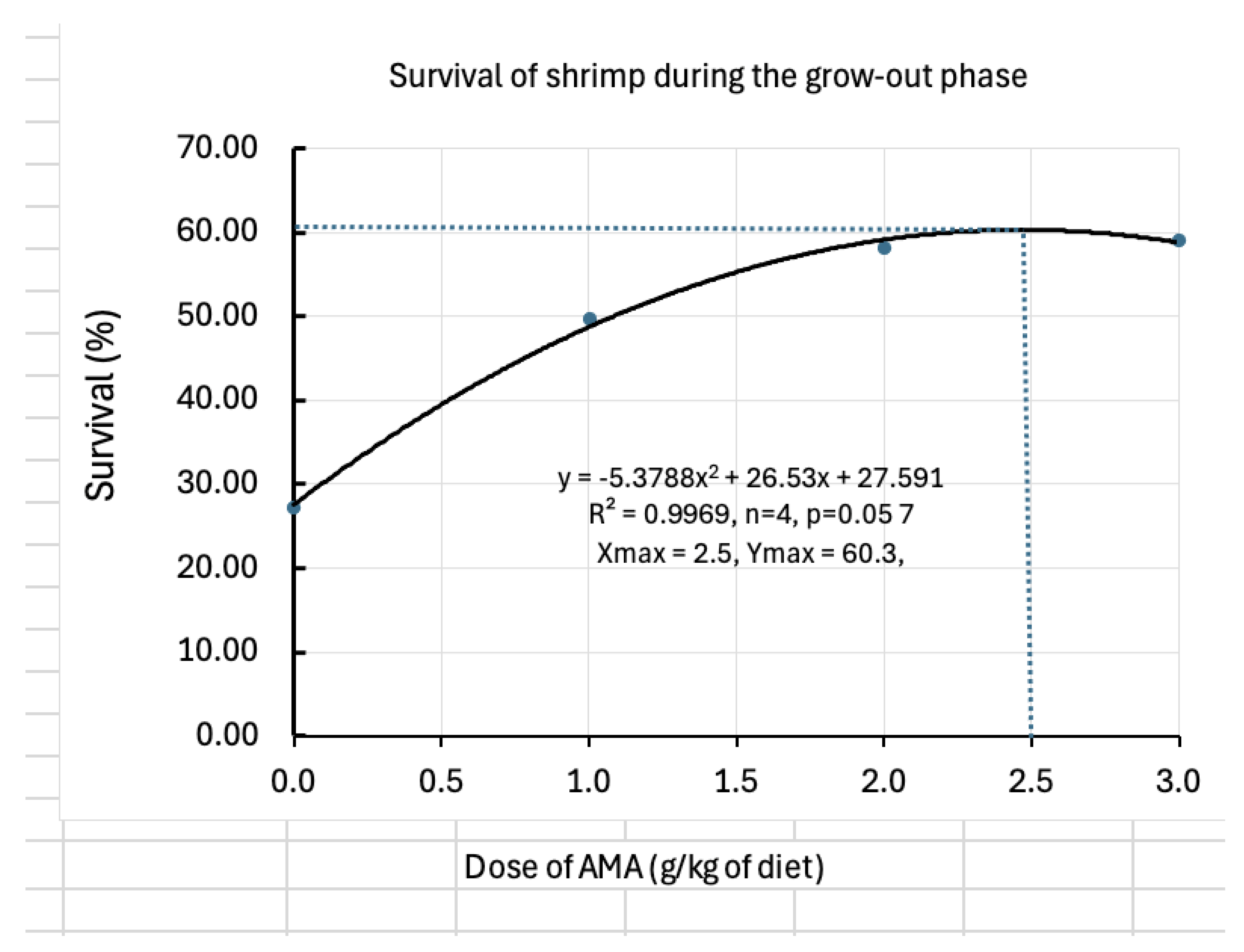

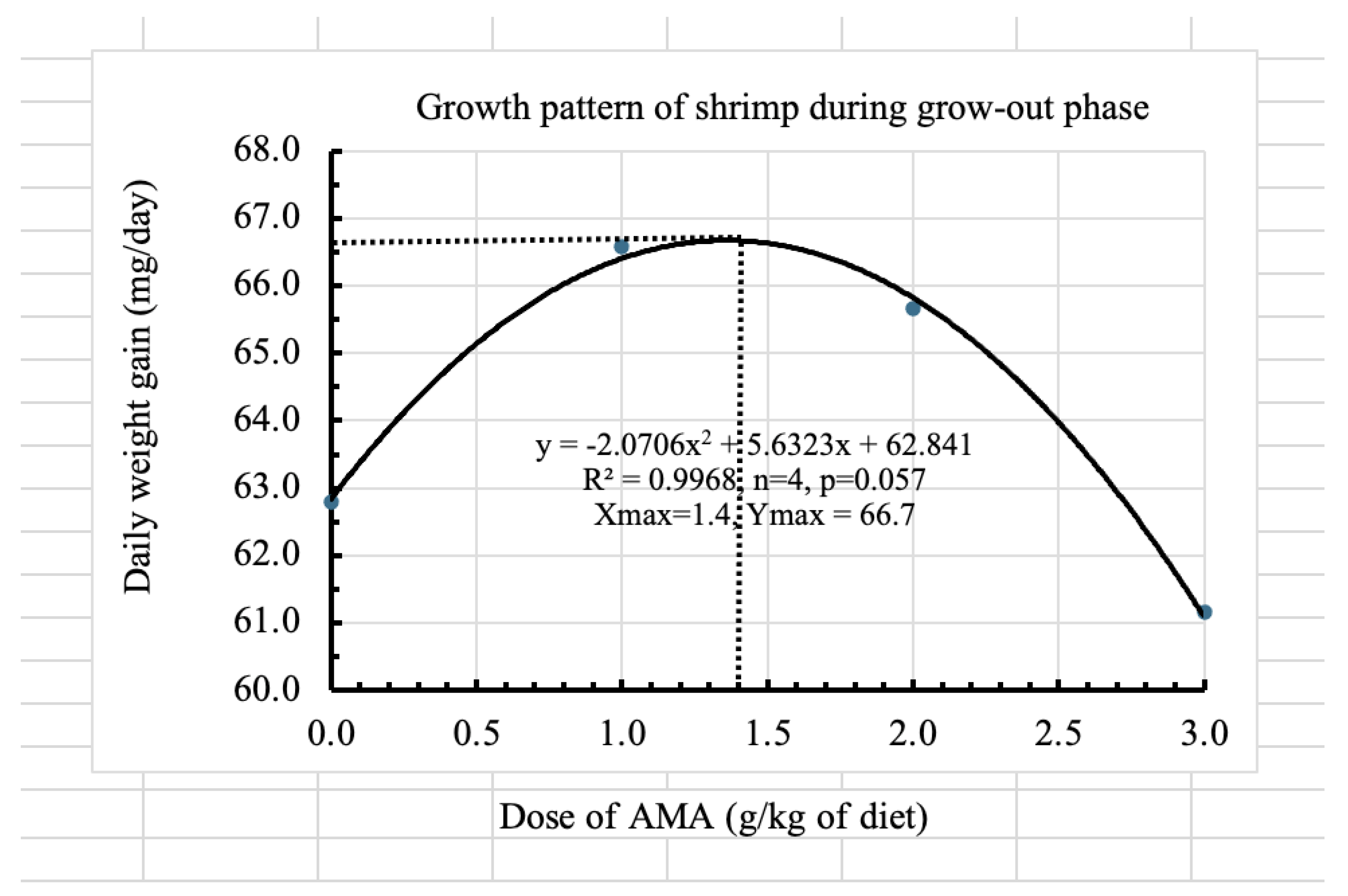

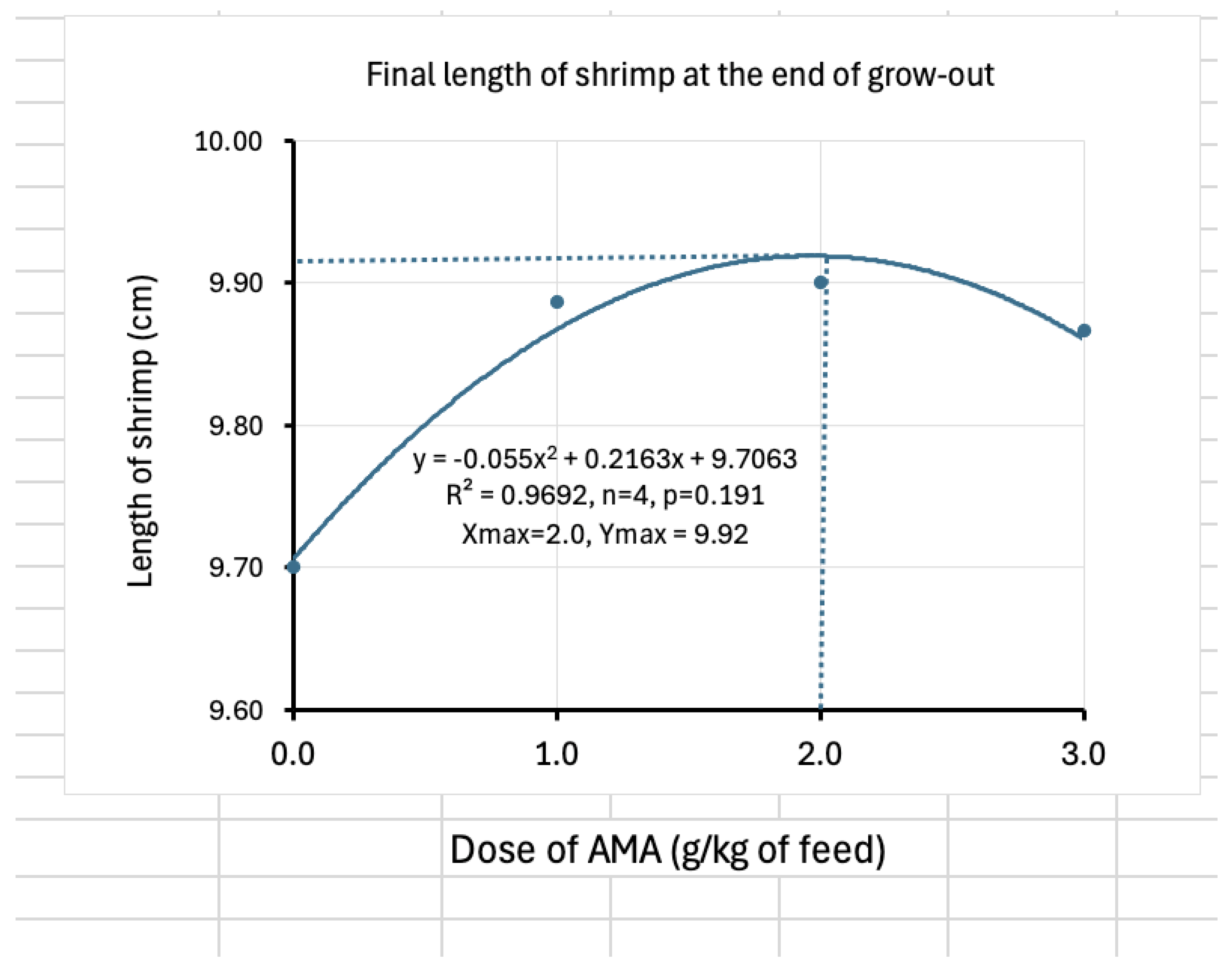

Shrimp farming often suffers due to high mortalities and poor growth. Mycotoxins can be one of the causes but often underestimated. An anti-mycotoxin additive (AMA) was tested designing an experiment to assess its efficacy and determine the best dose for pacific white shrimp (Litopenaeus vannamei). Four treatments (0, 1, 2 and 3 g/kg of diet) were randomly allocated in 12 aquaria during larval rearing (20 days) and 12 tanks fibreglass tanks during subsequent grow-out (90 days). Results showed positive impacts on feed conversion, protein efficiency, survival and growth. Higher the dose better is the immunity as indicated by the survival of shrimp against bacterial challenge. However, the quadratic models indicated that the dose of 1.4 g/kg had the highest daily weight gain of shrimp (66.7 mg) and the dose of 2.5 g/kg of diet resulted in the highest survival (60.3%). Therefore, the doses between 1.4 and 2.5 g/kg of feed are recommended for the grow-out phase of shrimp. However, further studies should be done in outdoor pond conditions for varying feeding regimes, varying contamination levels and stocking densities.

Keywords:

1. Introduction

2. Materials and Methods

2.1. Experimental System and Animal

2.2. Test Diets and Mycotoxins

2.3. Feed Supplement and Treatments

2.4. Water Quality Management

2.5. Sampling of Feed

2.6. Sampling of Shrimp

2.7. Data Records

2.8. Bacterial Challenge Trial

2.9. Data Analysis

3. Results

3.1. Post-Larvae Stage

3.2. Grow-Out Phase

3.3. Bacterial Challenge Phase

3.4. Morphometry Analysis

4. Discussion

5. Conclusions

Funding

Data Availability Statement

Acknowledgments

Conflicts of Interest

Abbreviations

| AIT AMA ANOVA CP CRD |

Asian Institute of Technology Anti-mycotoxin agent Analysis of variance Crude protein Complete randomized design |

| DO DWG FCR HPLC HSI LD50 Ln mL PER PL |

Dissolved oxygen Daily weight gain Feed conversion ratio High pressure liquid chromatography Hepato-somatic index Lethal dose at which 50% animal die Natural log Mili-litre Protein efficiency ratio Post-larvae |

| pH RAS SGR |

Potential of hydrogen ion concentration Recirculatory aquaculture system Specific growth rate |

References

- Bhujel, R.C. Global Aquatic Food Production. P. 99-126. In Aquatic Food Security. Crumlish, M. & Norman, R. (Eds). 5M-Books.2024. https://5mbooks.com/product/aquatic-food-security.

- FAO. The State of World Fisheries and Aquaculture. Blue Transformation in Action. Rome, Italy, 2022,. [CrossRef]

- SKYQUEST. Available online: https://www.skyquestt.com/report/shrimp-market/market-size (accessed on day month year).

- FAO Globefish. Quarterly Shrimp analysis - February 2025. Available online: https://openknowledge.fao.org/ (accessed on 31 May 2025).

- Rairat, T. , Kitsanayanyong, L., Keetanon, A., Phansawat, P., Wimanhaemin, P., Natnicha, C., Suanploy, W., Chow, P.Y.E. & Chuchird, N). Effects of monoglycerides of short and medium chain fatty acids and cinnamaldehyde blend on the growth, survival, immune responses, and tolerance to hypoxic stress of Pacific white shrimp (Litopenaeus vannamei). PLOS ONE 2024, 19, 0308559. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Eskola, M. , Kos, G., Elliott, C.T., Sultan Mayar, J.H., Krska, R.) Worldwide contamination of food-crops with mycotoxins: Validity of the widely cited ‘FAO estimate’ of 25%. Critical Reviews in Food Science and Nutrition 2020, 60, 2773–2789. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Alshannaq, A. , & Yu, J. H. (2017). Occurrence, toxicity, and analysis of major mycotoxins in food. International journal of environmental research and public health 2017, 14, 632. [Google Scholar]

- Bhujel, R. C. Mycotoxins in feed – an underestimated challenge for the aquafeed industry. Mycotoxinsite.com. 2021. https://mycotoxinsite.com/mycotoxins-feed-underestimated-challenge-aquafeed-industry/?lang=en&fbclid=IwAR1LawrpbuSoMu8eFRYgTeer-gOWTx9WTLJgTlZXkeZV7HrnqFF9k7jeIos.

- El-Sayed, R.A. , Jebur A.B., Kang, W. El-Demerdash, F.M. An overview on the major mycotoxins in food products: characteristics, toxicity, and analysis. Journal of Future Foods 2022, 2, 91–102. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Khan, R. , Anwar, F., Farinazleen Mohamad Ghazali, F. A comprehensive review of mycotoxins: Toxicology, detection, and effective mitigation approaches. Heliyon 2024, 10, e28361. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Anater, A. , Manyes, L., Meca, G., Ferrer, E., Luciano, F.B., Pimpão, C.T., Font, G. Mycotoxins and their consequences in aquaculture: A review. Aquaculture 2016, 451, 1–10. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Oliveira and Vasconcelos. .. Occurrence of mycotoxins in fish feed and its effects: A review. Toxins 2020, 12, 160. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Gonçalves, R.A. , Schatzmayr, D., Hofstetter, U., Santos, G.A. Occurrence of mycotoxins in aquaculture: Preliminary overview of Asian and European plant ingredients and finished feeds. World Mycotoxin Journal 2017, 10, 183–194. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Gonçalves, R.A. , Naehrer, K., Santos, G.A. Occurrence of mycotoxins in commercial aquafeeds in Asia and Europe: a real risk to aquaculture? Reviews in Aquaculture 2018, 10, 263–280. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Rokvic, N. , Aksentijevic, K., Kureljuic, J., Vasiljevic, M., Todorovic, N., Zdravkovic, N., Stojanac, N. (2020). Occurrence and transfer of mycotoxins from ingredients to fish feed and fish meat of common carp (Cyprinus carpio) in Serbia. World Mycotoxin Journal 2020, 13, 545–552. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- European Food Safety Authority (EFSA), (2010). Statement on the establishment of guidelines for the assessment of additives from the functional group ‘substances for reduction of the contamination of feed by mycotoxins. EFSA Journal 2010, 8, 1–8. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- European Food Safety Authority (EFSA).Guidance on the assessment of the efficacy of feed additives. EFSA Journal 2018, 16, 52–74. [CrossRef]

- Bintvihok, A. , Ponpornpisit, A., Tangtrongpiros, J., Panichkriangkrai, W., Rattanapanee, R., Doi, K.. Aflatoxin contamination in shrimp feed and effects of aflatoxin addition to feed on shrimp production. Journal Food Protein 2003, 66, 882–885. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Kracizy, R. O, Brazao, C.C., Viott, A.D.M., Ribeiro, K., Koppenol, A., dos Santos, A.M.V., Ballester, E.L.C.M. Evaluation of aflatoxin and fumonisin in the diet of Pacific White Shrimp (Litopenaeus vannamei) on their performance and health. Aquaculture 2021, 544, 737051. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Bhujel, R.C. , Perera, A.D., Todorović, N., Raj, J., Gonçalves, R.A. and Vasiljević, M. Evaluation of an Organically Modified Clinoptilolite (OMC) and a Multi-Component Mycotoxin Detoxifying Agent (MMDA) on Survival, Growth, Feed Utilization and Disease Resistance of Nile Tilapia (Oreochromis niloticus) Fingerlings Fed with Low Aflatoxin. Aquac. J. 2023, 3, 56–69. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Imani, A. , Salimi Bani, M., Noori, F., Farzaneh, M., Moghanlou, K.S. The effect of bentonite and yeast cell wall along with cinnamon oil on aflatoxicosis in rainbow trout (Oncorhynchus mykiss): Digestive enzymes, growth indices, nutritional performance and proximate body composition. Aquaculture 2017, 476, 160–167. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Hussain, D. Effect of aflatoxins in aquaculture: Use of bentonite clays as promising remedy. Turkish Journal of Fisheries and Aquatic Sciences 2018, 18, 1009–1016. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Neeratanaphan, L. , and Tengjaroenkul, B., Potential of Thai bentonite to ameliorate aflatoxin B1 contaminated in the diet of the Pacific white shrimp (Litopenaeus vannamei). Livestock Research for Rural Development 2018, 30.

- Philips, T.D. , Wang, M., Elmore, S.E., Hearon, S., Wang, J.-S. NovaSil Clay for the Protection of Humans and Animals from Aflatoxins and Other Contaminants. Clays and Clay Minerals 2019, 67, 99–110. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Yu, Y.-Y.; Niu, J.; Yin, P.; Mei, X.-T.; Liu, Y.-J.; Tian, L.-X.; Xu, D.-H. Detoxification and Immuno-protection of Zn (II)- Curcumin in Juvenile Pacific White Shrimp (Litopenaeus vannamei) Feed with Aflatoxin B1. Fish Shellfish. Immunol 2018, 80, 480–486. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- García-Pérez, O.D. , Tapia-Salazar, M., Nieto-López, M.G., Cruz-Valdez, J.C., Maribel Maldonado-Muñiz, M., Guerrero-Guerrero, L.M., Marroquín-Cardona, A.G.. Effects of conjugated linoleic acid and curcumin on growth performance and oxidative stress enzymes in juvenile Pacific white shrimp (Litopenaeus vannamei) feed with aflatoxins. Aquaculture Research 2020, 51, 1051–1060. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Bhoopathy, S. , Inbakandan, D (Inba), Rajendran, T., Chandrasekaran, K., Kasilingam, R., Gopal, D. Curcumin loaded chitosan nanoparticles fortify shrimp feed pellets with enhanced antioxidant activity. Materials Science & Engineering C 2021, 120, 111737. [Google Scholar]

- Moghadam, H. , Sourinejad, I., and Johari, S.A.Growth performance, haemato-immunological responses and antioxidant status of Pacific white shrimp Penaeus vannamei fed with turmeric powder, curcumin and curcumin nanomicelles. Aquaculture Nutrition 2021, 27, 2294–2306. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Quesada-Vázquez, S.; Codina Moreno, R.; Della Badia, A.; Castro, O.; Riahi, I. Promising Phytogenic Feed Additives Used as Anti-Mycotoxin Solutions in Animal Nutrition. Toxins 2024, 16, 434. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Neto, H.S. and Nunes, A.J.P.. Performance and immunological resistance of Litopenaeus vannamei fed a β-1,3/1,6-glucan-supplemented diet after per os challenge with the Infectious myonecrosis virus (IMNV). R. Bras. Zootec 2015, 44, 165–173. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Jin, M. , Xiong, J., Qi-Cun, Z, Yuan Y., Xue-Xi, W., Sun, P. (2018). Dietary yeast hydrolysate and brewer's yeast supplementation could T enhance growth performance, innate immunity capacity and ammonia nitrogen stress resistance ability of Pacific white shrimp (Litopenaeus vannamei). Fish and Shellfish Immunology 2018, 82, 121–129. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- AOAC. Official Methods of Analysis of Association of Official Analytical Chemists, 15th Edition, AOAC, Arlington, VA, 1298. (1990).

- Hung, L.T. and Quy, O.M. On farm feeding and feed management in White leg shrimp (Litopenaeus vannamei) farming in Viet Nam. In M.R. Hasan and M.B. New, eds. On-farm feeding and feed management in aquaculture. FAO Fisheries and Aquaculture Technical Paper No. 583. Rome, FAO. pp. 337–357. (2013).

- Antunes, C.R.N. , da Silva Ledo, C.A., Pereira, C.M, Dos Santos, J. (2018). Evaluation of feeding rates in the production of Litopenaeus vannamei shrimp using artificial substrates. Ciência Animal Brasileira 2018, 19. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Effendi, H. , Kawaroe, M., Lestari, D. F., Mursalin, & Permadi, T. Distribution of Phytoplankton Diversity and Abundance in Mahakam Delta, East Kalimantan. Procedia Environmental Sciences 2016, 33, 496–504. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Boyd, C.E., and Tucker, C.S. Water Quality and Pond Soil Analysis for Aquaculture. Alabama Agricultural Experiment Station, Auburn University publishers, USA. 1992. ISBN: 9780817307219.

- Maciel, C.R. , New M. & Valenti W.C. The Predation of Artemia nauplii by the larvae of the Amazon River prawn Macrobrachium amazonicum (Heller, 1862) is affected by prey density, time of day, and ontogenetic development. Journal of the World Aquaculture Society 2012, 43, 659–669. [Google Scholar]

- Hasanthi, M. , Jo, S., Han-se K., Kwan-Sik, Y., Lee, Y., Lee, K-J. Dietary supplementation of micelle silymarin enhances the antioxidant status, innate immunity, growth performance, resistance against Vibrio parahaemolyticus infection, and gut morphology in Pacific white shrimp (Litopenaeus vannamei). Animal Feed Science and Technology 2024, 311, 115953. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Song, Z. , Liu, H., Liu, Y., Ye, Z., Ma, Q., Wei, Y., Xiao, L., Liang, M., and Xu, H. Effects of the Supplementation of Lysophospholipid in Low-Lipid Diets on Juvenile Pacific White Shrimp. Aquaculture Research 2024, 11. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Limwachirakhom, R. , Triwutanon S., Zhang Y., and Jintasataporn O. Effects of dietary lysophospholipids on the performance of Pacific white shrimp (Litopenaeus vannamei) fed fish oil- and energy-reduced diets. Front. Mar. Sci 2025, 12. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Yang, X. , Chi, S., Tan, B., Nie, Q., Dong, X., Yang, Q., Liu, H. and Zhang, S. Yeast hydrolysate helping the complex plant proteins to improve the growth performance and feed utilization of Litopenaeus vannamei. Aquaculture Reports 2020, 17, 100375. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Yiannikouris, A. , Andre, G., Poughon, L., François, J., Dussap, C.G., Jeminet, G., Bertin, G., and Jouany, J.P. Chemical and Conformational Study of the Interactions Involved in Mycotoxin Complexation with β-D-Glucans. Biomacromolecules 2006, 7, 1147–1155. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Xu, R. , Yiannikouris, A., Shandilya, U.K., and Karrow, N.A. Comparative Assessment of Different Yeast Cell Wall-Based Mycotoxin Adsorbents Using a Model- and Bioassay-Based In Vitro Approach. Toxins 2023, 15, 104. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Sharma, N. Exploring the potential of mannan oligosaccharides in enhancing animal growth, immunity, and overall health: A review. Carbohydrate Polymer Technologies and Applications 2025, 9, 100603. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Jach, M.E. , Serefko, A., Ziaja, M., and Kieliszek, M. Yeast Protein as an Easily Accessible Food Source. Metabolites 2022, 12, 63. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Rahimnejad, S. , Leclercq, E., Malinovskyi, O., Penka, A., Kolárová, J., and Policar, A. (2023). Effects of yeast hydrolysate supplementation in low-fish meal diets for pikeperch. Animal The international journal of animal biosciences 2023, 17, 100870. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Huifeng, L. , Erchao, L., Chang, X., Li, Z. and Liqiao, C. Effects of silymarin on growth, activities of immune-related enzymes, hepatopancreas histology and intestinal microbiota of the Pacific white shrimp (Litopenaeus vannamei) at low salinity. Journal of Fisheries of China 2021, 45, 98–114. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Wang, J. , Peng, H., Jin, M., Li, M., He, Y., Li, S., Zhu, T., Zhang, Y., Tang, F., and Zhou, Q. Dietary lysophospholipids supplementation promotes growth performance, enhanced antioxidant capacity, and improved lipid metabolism of Litopenaeus vannamei. Aquaculture Reports 2024, 39, 102476. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Khan, H. I. , Madhubabu, E. P., Jannathulla, R., and Ambasankar, K. Effect of partial replacement of marine protein and oil sources in presence of lyso-lecithin in the diet of tiger shrimp Penaeus monodon Fabricius, 1978. Indian Journal of Fisheries 2018, 65, 100–107. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Chyng-Hwa, L. , Vu-An, T., Zhong-Fu, Z., Yu-Hung L. The effect of dietary lecithin and lipid levels on the growth performance, body composition, hemolymph parameters, immune responses, body texture, and gene expression of juvenile white shrimp (Litopenaeus vannamei). Aquaculture 2023, 567, 739260. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Santacroce, M. P. , Conversano, M. C., Casalino, E., Lai, O., Zizzadoro, C., Centoducati, G., and Crescenzo, G. Aflatoxins in aquatic species: metabolism, toxicity and perspectives. Reviews in Fish Biology and Fisheries 2007, 17, 107–120. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Mexía-Salazar, A. L. , Hernández-López, J., Burgos-Hernández, A., Cortez-Rocha, M. O., Castro-Longoria, R., and Ezquerra-Brauer, J. M. Role of fumonisin B1 on the immune system, histopathology, and muscle proteins of white shrimp (Litopenaeus vannamei). Food Chemistry 2008, 110, 471–479. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Sun, Y.; Song, Y.; Long, M.; and Yang, S. Immunotoxicity of Three Environmental Mycotoxins and Their Risks of Increasing Pathogen Infections. Toxins 2023, 15, 187. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Ng, W.-K. , Mong, M.-L., and Abdul-Hamid, A.-A.. Dietary montmorillonite clay improved Penaeus vannamei survival from acute hepatopancreatic necrosis disease and modulated stomach microbiota. Animal Feed Science and Technology 2023, 297, 115581. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Pourjam, F. , Sotoudeh, E., Bagheri, D., Ghasemi, A., and Esmaeili, N.Dietary montmorillonite improves growth, chemical composition, antioxidant system and immune-related genes of whiteleg shrimp (Litopenaeus vannamei). Aquaculture International 2024, 32, 5699–5717. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

| Treatment no. | Treatments | Dose of AMA (g/kg feed) |

|---|---|---|

| T1 | Control (no AMA) | 0.0 |

| T2 | Level 1 (low) | 1.0 |

| T3 | Level 2 (medium) | 2.0 |

| T4 | Level 3 (high) | 3.0 |

| Parameters | Treatments (g/kg diet) | |||

| 0.0 | 1.0 | 2.0 | 3.0 | |

| Initial number | 300±0 | 300±0 | 300±0 | 300±0 |

| Final number | 159±21 | 188±15 | 139±41 | 192±12 |

| Survival (%) | 52.9±7.0 | 62.6±4.9 | 46.4±13.7 | 64.0±3.8 |

| Initial length (cm) | 1.1±0.02 | 1.1±0.02 | 1.1±0.02 | 1.1±0.02 |

| Initial weight (mg) | 9.2±0.0 | 9.2±0.03 | 9.2±0.03 | 9.2±0.0 |

| Final length (cm) | 2.5±0.1b | 2.8±0.0a | 2.8±0.1a | 2.9±0.0a |

| Final weight (mg) | 140±10 | 126±6 | 151±26 | 126±2 |

| Daily weight gain (g) | 6.5±0.5 | 5.9±0.3 | 7.1±1.3 | 5.8±0.1 |

| Length gain (cm/day) | 0.07±0.0b | 0.09±0.0a | 0.08±0.01a | 0.09±0.0a |

| Specific growth rate (%) | 13.6±0.4 | 13.1±0.2 | 14.0±0.9 | 13.1±0.1 |

| Parameters | Treatments (g/kg diet) | ||||

| 0.0 | 1.0 | 2.0 | 3.0 | ||

| Whole body | Moisture (%) | 88.93±0.34a | 88.14±0.17ab | 87.86±0.66b | 87.92±0.22ab |

| Ash (%) | 23.51±0.15a | 17.09±0.97b | 17.42±1.56b | 17.61±3.07b | |

| Lipid (%) | 14.25±1.06c | 17.26±1.11b | 22.22±0.19a | 13.22±0.37c | |

| Protein (%) | 35.75±4.32a | 56.99±3.80b | 35.15±1.73a | 37.88±0.56a | |

| Treatment with AMA |

Water Quality | ||||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| DO (mg/L) | pH | Temp (°C) | NO2- N (mg/L) | NH3-N(mg/L) | |

| Control (0.0 g/kg) | |||||

| Average | 6.85±0.17 | 8.24±0.09 | 27.92±0.38 | 3.27±1.04 | 0.81±0.45 |

| Min-Max | 6.44-7.01 | 8.02-8.32 | 27.1-28.3 | 1.76-4.84 | 0.07-1.51 |

| Low (1.0 g/kg) | |||||

| Average | 7.02±0.11 | 8.21±0.07 | 27.98±0.26 | 2.63±1.51 | 0.72±0.27 |

| Min-Max | 6.9-7.17 | 8.11-8.3 | 27.7-28.3 | 1.01-5.89 | 0.34-1.12 |

| Medium (2.0 g/kg) | |||||

| Average | 6.91±0.07 | 8.22±0.05 | 28.08±0.26 | 3.15±1.29 | 0.6±0.33 |

| Min-Max | 6.83-7.05 | 8.11-8.28 | 27.7-28.4 | 1.98-5.74 | 0.3-1.37 |

| High (3.0 g/kg) | |||||

| Average | 6.98±0.09 | 8.26±0.07 | 27.97±0.29 | 2.23±0.56 | 0.58±0.29 |

| Min-Max | 6.83-7.16 | 8.13-8.34 | 27.5-28.3 | 1.38-3.19 | 0.17-1.09 |

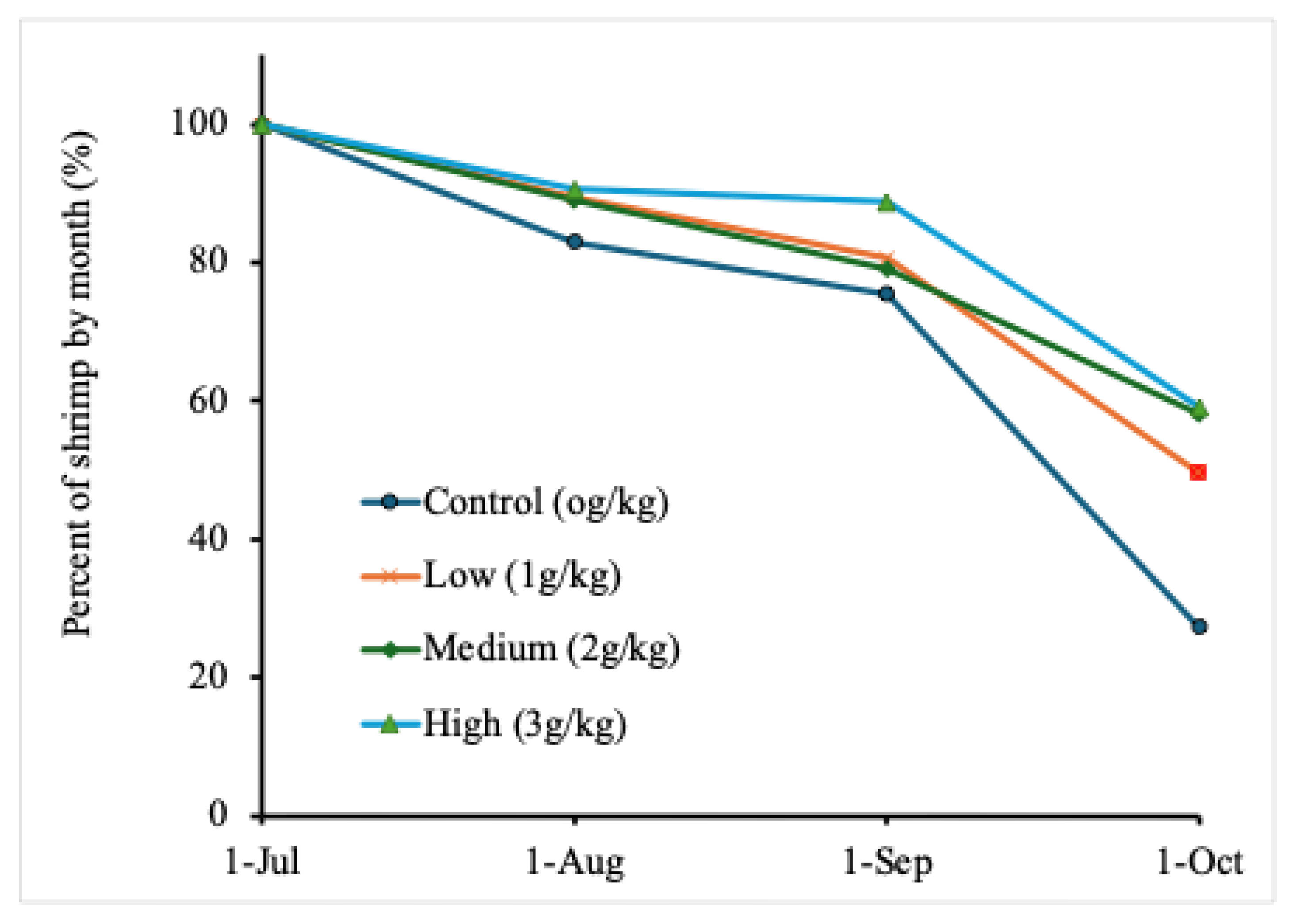

| Treatment dose | 1-July | 1-Aug | 1-Sep | 1-Oct |

|---|---|---|---|---|

| Control (0.0 g/kg) | 110±0 | 91±11 (83%) | 83±4 (75%) | 30±10 (27%)b |

| Low (1.0 g/kg) | 110±0 | 98±8 (89%) | 89±15 (81%) | 55±15 (50%)ab |

| Medium (2.0 g/kg) | 110±0 | 98±1 (89%) | 87±10 (79%) | 64±4 (58%)ab |

| High (3.0 g/kg) | 110±0 | 100±6 (91%) | 99±2(89%) | 65±9 (59%)a |

| Parameters | Treatments (g/kg diet) | |||

| 0.0 | 1.0 | 2.0 | 3.0 | |

| Initial length (cm) | 3.57±0.02 | 3.57±0.1 | 3.41±0.11 | 3.54±0.17 |

| Initial weight (g) | 0.28±0.0 | 0.27±0.0 | 0.28±0.0 | 0.27±0.0 |

| Final length (cm) | 9.70±0.33 | 9.89±0.74 | 9.90±0.94 | 9.87±0.55 |

| Final weight (g) | 6.1±1.3 | 6.4±1.3 | 6.3±1.1 | 5.9±0.6 |

| Length gain (cm) | 6.13±0.34a | 6.31±0.72a | 6.49±0.83a | 6.33±0.67a |

| Weight gain (mg/day) | 62.8±13.9 | 66.6±14.5 | 65.7±11.4 | 61.2±6.6 |

| Length gain (mm/day) | 66.6±3.7 | 68.6±7.9 | 70.5±0.01 | 68.8±7.3 |

| Initial number | 110±0.0 | 110±0.0 | 110±0.0 | 110±0.0 |

| Final number | 30±9.90b | 54.67±15.04a | 64±4.24a | 65±8.54a |

| Survival (%) | 27.3±9.0c | 49.7±13.68ab | 58.3±3.86ab | 59.1±7.8a |

| Specific growth rate (%) | 3.3±0.2 | 3.4±0.3 | 3.4±0.2 | 3.4±0.2 |

| Feed conversion ratio (FCR) | 2.3±0.8 | 1.3±0.1 | 1.5±0.3 | 1.2±0.1 |

| Protein efficiency ratio (PER) | 92±36 | 153±10 | 135±33 | 168±8 |

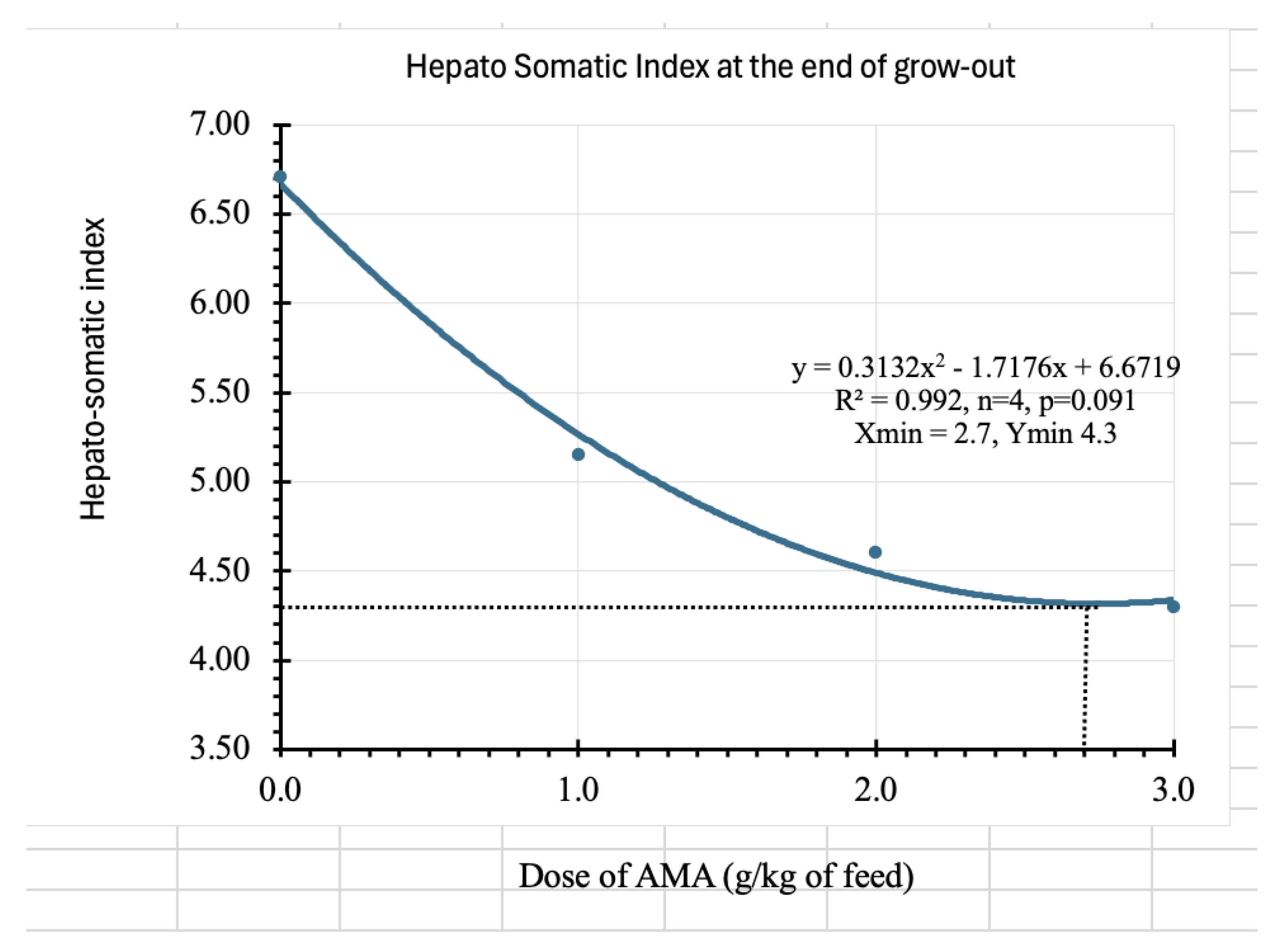

| HSI (%) | 6.71±0.87 a | 5.15±0.64 b | 4.60±0.70 b | 4.30±1.07 b |

| Factors | Treatments (g/kg diet) | ||||

| 0.0 | 1.0 | 2.0 | 3.0 | ||

| Feed | Moisture | 13.68±0.93 | 14.77±0.09 | 14.33±0.48 | 14.62±0.12 |

| Ash | 14.41±0.09 b | 14.50±0.09 b | 14.44±0.07 b | 14.76±0.00 a | |

| Lipid | 4.68±0.76 | 5.24±1.49 | 4.99±0.43 | 5.48±0.41 | |

| Protein | 38.44±0.47 | 38.77±0.16 | 38.75±0.41 | 38.51±0.44 | |

| Whole body | Moisture | 75.41±1.43a | 65.21±1.91b | 72.14±0.19a | 75.57±1.45a |

| Ash | 11.69±0.59 | 9.94±1.42 | 10.55b±1.48 | 13.19±2.08 | |

| Lipid | 5.15±0.61a | 3.32±0.11b | 3.45±0.26b | 3.26±0.1b | |

| Protein | 80.66±0.24b | 77.72±1.36c | 80.73±0.68b | 82.97±0.59a | |

| Faeces | Moisture | 89.30±2.34 | 89.10±2.38 | 88.95±2.68 | 88.13±2.54 |

| Ash | 41.36±3.18b | 47.15±3.96ab | 50.56±2.46a | 51.85±3.16aa | |

| Lipid | 0.85±0.15a | 0.38±0.09b | 0.63±0.11ab | 0.37±0.05b | |

| Protein | 11.82±2.45a | 5.79±1.49b | 13.24±0.18a | 12.80±1.51a | |

| Treatment with AMA |

Water Quality | ||||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| DO | pH | Temp | NO2-N | NH3-N | |

| Control (0.0 g/kg) | |||||

| Average | 6.87±0.14 | 8.08±0.14 | 27.90±0.62 | 2.97±1.08 | 1.11±0.68 |

| Min-Max | 6.59-7.14 | 7.88-8.37 | 27.00-29.00 | 1.08-5.14 | 0.39-2.47 |

| Low (1.0 g/kg) | |||||

| Average | 6.93±0.18 | 8.03±0.13 | 27.98±0.63 | 2.75±1.10 | 1.23±0.65 |

| Min-Max | 6.39-7.15 | 7.80-8.26 | 27.10-29.20 | 1.01-5.22 | 0.57-2.89 |

| Medium (2.0 g/kg) | |||||

| Average | 6.91±0.09 | 8.01±0.16 | 26.57±6.02 | 3.57±1.41 | 1.13±0.45 |

| Min-Max | 6.74-7.03 | 7.65-8.21 | 27.00-29.00 | 1.23-5.44 | 0.51-2.34 |

| High (3.0 g/kg) | |||||

| Average | 6.87±0.13 | 8.00±0.24 | 28.04±0.64 | 2.99±1.32 | 1.10±0.69 |

| Min-Max | 6.39-7.15 | 7.80-8.26 | 27.01-29.20 | 1.01-5.22 | 0.57-2.89 |

| Treatment (g/kg diet) |

Infected group (average days) | |

|---|---|---|

| Mortality starting day | Final survival days | |

| Control (0.0) | 3.00±0.0a | 8.67±1.53a |

| Low (1.0) | 7.33±0.58b | 12.00±2.00b |

| Medium (2.0) | 7.67±1.53b | 11.67±0.58b |

| High (3.0) | 8.33±0.58b | 12.00±0.00b |

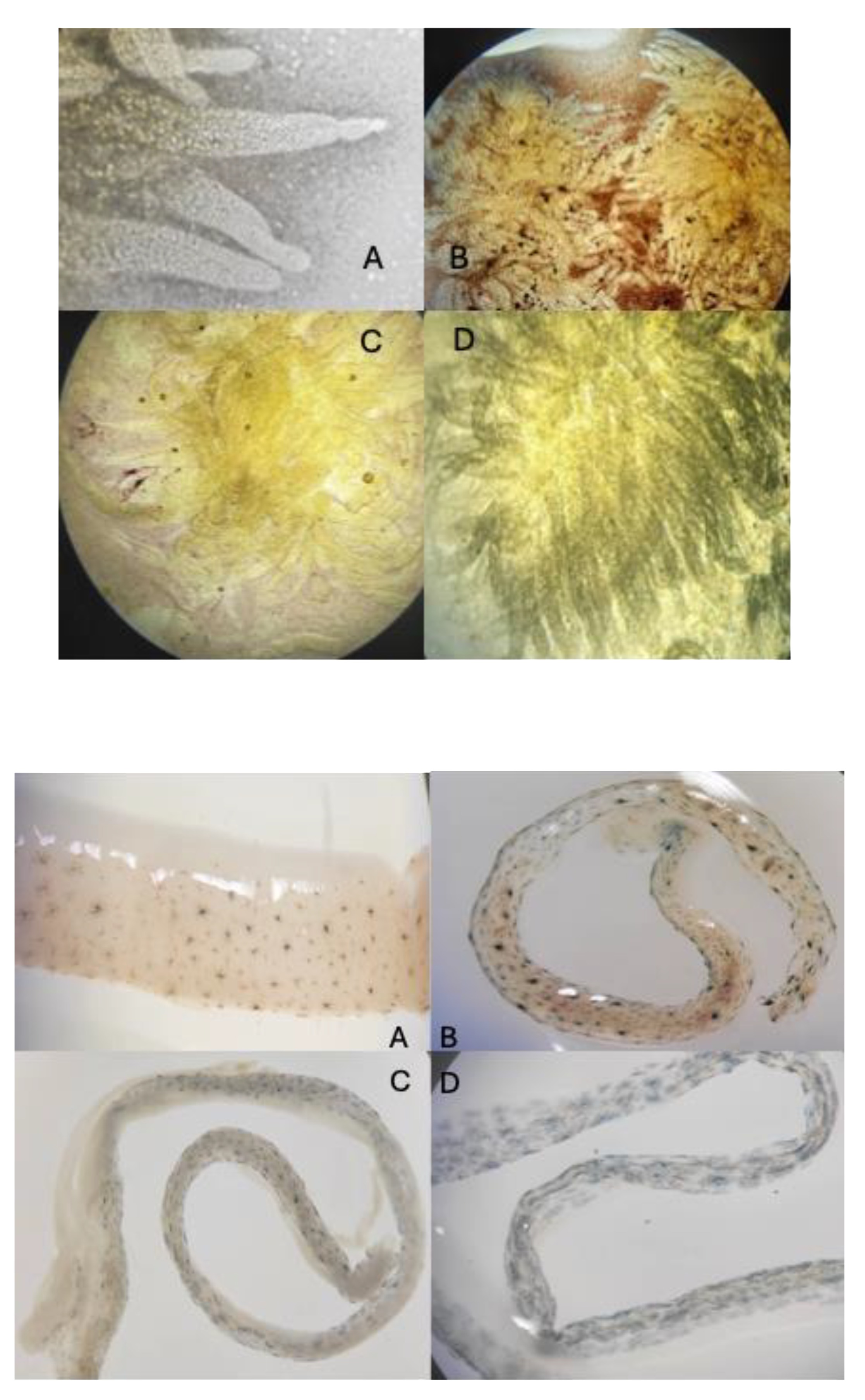

| Treatments (g AMA/kg diet) | ||||

|---|---|---|---|---|

| Organs | 0.0 | 1.0 | 2.0 | 3.0 |

|

Pale, soft shell | Normal, hard shell | Normal, hard shell | Normal, hard shell |

|

Empty | Half full | Half full | Empty |

|

Red & inflammation | Red & inflammation | Blue & normal | Blue & normal |

|

Dark brown | Brown | Brown | Dark brown |

| Less lipid | Less lipid | Less lipid | Less lipid | |

| Thin cell wall | Thin cell wall | Thin cell wall | Thin cell wall | |

| Not normal | Not normal | Smooth/normal | Smooth/normal | |

Disclaimer/Publisher’s Note: The statements, opinions and data contained in all publications are solely those of the individual author(s) and contributor(s) and not of MDPI and/or the editor(s). MDPI and/or the editor(s) disclaim responsibility for any injury to people or property resulting from any ideas, methods, instructions or products referred to in the content. |

© 2025 by the authors. Licensee MDPI, Basel, Switzerland. This article is an open access article distributed under the terms and conditions of the Creative Commons Attribution (CC BY) license (http://creativecommons.org/licenses/by/4.0/).